Archive for the 'Film scholarship' Category

Coming attractions, plus a retrospect

Invasion of the Brainiacs

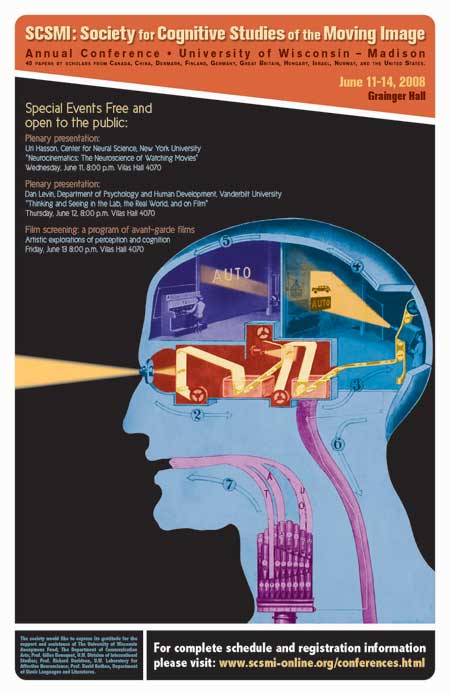

First, the event that will occupy us through next week: the annual conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image, a group founded in 1997. This year’s gathering brings researchers from Britain, Germany, Hungary, Israel, Turkey, Canada, China, and the Nordic countries, as well as many from the U. S. The meeting is here in Madison, from 11 to 14 June.

In over forty sessions, researchers will be talking about how we respond to movies, TV shows, and videogames. How has digital imagery changed our experience of cinema? How does film music enhance our emotional response to the story? How do films guide our visual attention to one part of the screen, and how much do viewers differ in this? How do we respond when movie characters behave inconsistently?

I’ve already blogged and bragged about our event here, but now I want to highlight four attractions. If you’re in or near Madison, you might want to stop by; and in any case, you might want to check the links mentioned below.

For some years Professor Uri Hasson of New York University’s Center for Neural Science has studied how the human brain responds during film viewing. Using fMRI techniques, he has discovered that Hollywood films, such as those by Hitchcock, have created remarkably similar responses across a variety of viewers. Art films, he says, may require just as much concentration, but they will elicit less convergent reactions. He’ll present the fruits of his research on June 11. You can learn more about Uri’s research here.

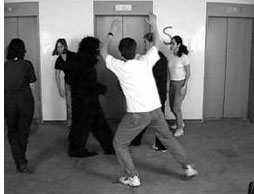

On June 12, Professor Dan Levin will lecture on “Thinking and Seeing in the Lab, the Real World, and on Film.” Levin has been actively studying how viewers’ concentration, watching a film or in real life, encourages them to overlook actions or changes taking place in front of them. He showed the power of “inattentional blindness” in his famous “gorilla-suit” experiments. Filmmaker Errol Morris recently interviewed Levin for The New York Times about continuity errors in films. You can read more of Dan’s fairly mind-bending work here.

On June 12, Professor Dan Levin will lecture on “Thinking and Seeing in the Lab, the Real World, and on Film.” Levin has been actively studying how viewers’ concentration, watching a film or in real life, encourages them to overlook actions or changes taking place in front of them. He showed the power of “inattentional blindness” in his famous “gorilla-suit” experiments. Filmmaker Errol Morris recently interviewed Levin for The New York Times about continuity errors in films. You can read more of Dan’s fairly mind-bending work here.

NB: 12 June 2008: In fact, the gorilla-suit experiment was conducted by Dan Simons, not Dan Levin. The last link takes you to Simons’ article. Both Dans work in the area of attention and “change blindness,” and they have collaborated on several projects. I apologize for the error.

There is a registration fee for the conference’s day events, but these evening lectures are free and open to the public. Each begins at 8:00 PM and will be held in 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Avenue.

The final night of the conference is devoted to a screening of experimental and avant-garde films that provoke questions about how we respond to cinema. There will be a discussion of them afterward, which will include two of the filmmakers, Joseph Anderson and J. J. Murphy. This screening, open to the public, starts at 8:00 PM in 4070 Vilas.

During the conference, one event is devoted to a discussion of Noël Carroll’s The Philosophy of Motion Pictures. This book is a remarkable effort to mount a systematic philosophy of film, TV, and related media. It’s full of provocative claims (e.g., that cinematic movement isn’t an illusion) and nifty examples. Noël is a polymath, with two Ph. D.s and more books and articles than anybody, including he, can count. Four other scholars will criticize some aspect of the book’s arguments, and Noël will respond. (One of those critics, Lester Hunt, is a philosophy prof here who maintains a wide-ranging website and a blog that often touches on film.) There should be some fireworks.

There are other brainiacs coming, many of them pioneers in this area: Joe and Barb Anderson, Murray Smith, Torben Grodal, Patrick Colm Hogan, Carl Plantinga, Paisley Livingston, Sheena Rogers, Dan Barratt, and Tim Smith (aka Continuity Boy), and too many others to include here. In all, I’m proud of what our local team, with the energetic Jeff Smith as point man, has accomplished in setting up this jamboree.

As regular readers know, I think that cognitive research into cinema holds great promise. It brings together a group of scholars from different disciplines who want to understand, in an empirical way, how movies work. The field is very young, and it’s not the only way to go; but it has a lot to contribute to our understanding of media, and maybe our understanding of the mind too.

Up to now SCSMI has been quite an informal group, but now we have a more systematic organization. We have officers, bylaws, and a sense that our research is coalescing around key ideas, about which there is lively and congenial disagreement. And, because there are more people who want to get involved, we’ll start meeting every year. The 2009 gathering is slated for Copenhagen.

I hope to dash off a blog entry in medias res. We’ll also do our best to introduce our colleagues from overseas and from the Coasts to the glories of brats, cheese, beer, and of course The House on the Rock.

By the way, you might want to check on this cognitive scientist, who claims that every one of us can see into the future (but only a little bit).

Kristin and the Comic-Book Guys (100,000 or so)

Speaking of gatherings of like-minded individuals, TheOneRing.net people have invited Kristin to take part in their panel on the upcoming Hobbit project at Comic-Con in San Diego, on Friday, July 25 at 10 am. She hopes to blog from among the multitudes.

A new website and a nervous DVD

There’s a new and attractive website up and running. Sponsored by the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, NYC, Moving Image Source is a vast project packed with links, research data, and essays about films both classic and contemporary. The first posse of writers includes Michael Atkinson, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Ed Sikov, Melissa Anderson, and other luminaries. The topics range from Andy Warhol and Howard Hawks to Werner Herzog (an interview). Steered by Dennis Lim, this is bound to be an essential watering hole for everybody interested in film history and criticism.

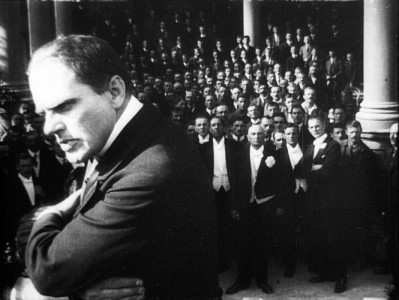

Speaking of film history, an important film is coming to DVD. Robert Reinert’s 1919 Nerven, which I wrote about in Poetics of Cinema, has been restored by Stefan Drössler and his crew at the Munich Filmmuseum. This is one of the strangest movies of the silent era. The plot, as Chris Horak points out in his accompanying essay, is steeped in Spenglerian melancholy, reminding us that Expressionism could be politically conservative as well as revolutionary. The visuals are at once monumental and unstable, like boulders teetering over a precipice. I try to analyze them in another contribution to the DVD booklet. Drössler has contributed an essay on the process of restoration.

Nerven was a box-office fiasco and never achieved the fame of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. In a way, it is more disturbing than that official classic because Reinert’s alternation of frenzy and somnambulism takes place in a more or less solid world, like ours. Frantic scenes of street fighting mix with brooding images of a bourgeoisie sliding into religious possession or straight-up lunacy. It is not every day that you see a movie that begins with a man throttling his wife and then lovingly refilling their parakeet’s water cup. If you’re a fan of wild deep-space imagery way before Citizen Kane (as above), this one’s for you. And yes, it will have English subtitles.

Nerven will be available later this summer from the Filmmuseum’s shop. It joins an abundance of other fine DVD titles, such as Borzage’s The River and a collection of Walter Ruttmann’s works.

Retrospect: In Europe they do things differently?

Because we see a very thin slice of foreign-language cinema, audiences underestimate the extent to which European films often imitate Hollywood. Surely the cultures of the great continent would never stoop to the crassness of our movies? A trip to any multiplex in Paris or Berlin would probably disabuse people of this notion. The current instance is the reigning French hit Bienvenue chez les ch’tis (Welcome to the Sticks), apparently a fish-out-of-water tale that would induce groans from our intelligentsia.

Kristin has already written about this phenomenon here. I found some supporting evidence last week while scrabbling through an old folder for our Film History revision. It was a 2002 pamphlet from the Filmboard of Berlin Brandenburgh GmbH, a publicly limited company coordinating German state funding. The text laid out a set of guidelines, in English, for productions that the Filmboard would support. After explaining that the judges must consider financial return as well as cultural factors, the guidelines insist that the quality of the screenplay is of paramount importance. What makes a good screenplay?

The success of a film decisively depends upon whether the audience can engage enthusiastically with the actors on the screen. An audience looks for strong central characters whose fates it can identify with. The hero or heroine should have goals and needs and should have an emotional effect on an audience. Further dramaturgical criteria:

There must be a concrete goal, which at the end of the story is either reached—or not.

There should be a risk involved for the central character in not reaching his/her goal.

The goal is perhaps difficult to reach, and the struggle to do so should bring the central character into conflict. The audience sympathizes with the story when, for example, the hero or heroine follows the wrong goal, makes mistakes, or experiences a crisis.

This sounds easy to understand. But writing screenplays is more complex.

*The central character should have subconscious needs. He/ she should lack an important human quality and only gradually experience this for him/herself.

*At the end of the story the central character should come to know his/her unconscious needs and gain a satisfactory recognition about him/herself and life in general, which can be formulated in the emotional subject matter of the film.

*The central character should undergo a process of development, as characters that do not develop are boring. Moments of decision in stories are the key for good character development.

The passage lays out a lot of what U. S. screenplay manuals have been asserting for decades (notions that Kristin and I have analyzed in various books). This is still more evidence that the Hollywood model, with its goal-oriented chain of causes and effects and its protagonist who improves through a “character arc,” holds sway far beyond our own shores. Whether it should be so widespread is another question, but for Kristin and me, this template or formula is a bit like the sonnet or the well-made play: a form that can yield results good, bad, and indifferent. The point is to take the form seriously enough to understand what makes it work.

From Comic Book Guy’s Book of Pop Culture (New York: HarperCollins, 2005), n.p.

Fair is still fair, and more so

Film Art: frames from Election illustrating the concept of motifs

Kristin here—

Back in 1977, when David and I began writing Film Art: An Introduction, we knew from the start that we would use frame enlargements as illustrations. At the time, that wasn’t common practice for film books, even textbooks. One reason was that it was difficult to obtain such images, but perhaps even more daunting was the notion that using frame enlargements would violate copyright. But Film Art came out of classes we had been teaching, and there we used slides of frames and 16mm clips during lectures to illustrate cinema techniques, style, and form. We didn’t see any way we could write it without photographing and reproducing actual frames.

From the start, we assumed that using frames in an educational context would be fair use. A few frames from a film would be comparable to a few words from a poem or a novel, we figured. We didn’t request permission to reproduce most of the frames printed in the book. The exceptions were films by experimental filmmakers, whom we asked more out of courtesy than because we figured we legally needed to.

One pleasant incidental result of such requests was that we now have autographs from Norman McLaren, Michael Snow, Ernie Gehr, and Bruce Connor. These unfortunately are on dull request forms. Connor livened his up a bit by adding, “I own the splices on my films. The images from individual frames are not copyrighted by myself.” He also enclosed the accompanying card as a little surrealist gesture.

One pleasant incidental result of such requests was that we now have autographs from Norman McLaren, Michael Snow, Ernie Gehr, and Bruce Connor. These unfortunately are on dull request forms. Connor livened his up a bit by adding, “I own the splices on my films. The images from individual frames are not copyrighted by myself.” He also enclosed the accompanying card as a little surrealist gesture.

We never got in trouble with the copyright holders for reproducing the hundreds of frames in Film Art. Most of our other books have also involved frames, from Méliès shorts to The Lord of the Rings.

The 1993 Report on Fair Use and Film Stills

Initially some of our editors were a bit reluctant to include those frames unless we obtained permissions from the copyright holders, but we managed to talk them into it. Then, in the early 1990s, I was asked to chair a special committee of the Society for Cinema Studies (now the Society for Cinema and Media Studies) to investigate the question of fair use of film frames and photographs. The result was the “Report of the Ad Hoc Committee of the Society for Cinema Studies, ‘Fair Usage Publication of Film Stills,’” written by me with help from my colleagues John Belton, Dana Polan, and Bruce F. Kawin. Experts, including the Register of Copyrights, Ralph Oman, and Prof. Peter Jaszi, an expert on copyright law, contributed their thoughts on the matter. The report first appeared in the Winter 1993 issue of Cinema Journal and is available online.

The fair-use law itself is simple. Here are the factors to be considered in determining whether the reproduction of a work violates its copyright:

1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

That last one seems to me particularly important for scholars, since it would be very difficult, if not impossible to prove that anything we publish diminishes the market value of the original. Quite the contrary, we help in our own small way to publicize that original.

I argued in the report that fair use did apply to film frames used in an educational context. The case for reproducing publicity and other behind-the-scenes photographs was considerably less clear, since unlike film frames, photographs can be individually copyrighted.

The report has had salubrious effects on film publications. Slowly more journal and academic-press editors accepted the idea that fair use does mean that authors don’t need to seek permissions. Given that most big studios either ignore such requests or demand hundreds or even thousands of dollars for their consent, the new policies of many journals and presses was a great boon to cinema studies. Gradually more and more scholarly and educational publications used frames instead of publicity stills, which made their descriptions and analysis much more effective. By now the use of film frames has become common practice.

Some encouraging cases

Occasionally, however, someone who is nervous about using frames writes to me to ask if anything has happened since 1993 that would change the situation. Has anyone been sued by a film studio for using film frames? Has a precedent been set?

In the report, I predicted that no studio would ever sue over the academic use of film frames. That was partly because the studios have bigger fish to fry, particularly the huge question of how to prevent film piracy. In contrast to bootleg DVDs selling for a couple of dollars in the streets of Shanghai or Moscow, we film scholars do not figure in the consciousness of the studio legal departments.

There have been some events that I think make it worth revisiting the issue of fair use in a more informal way here.

First, the very fact that the use of frame enlargements has become so common and that fewer academics seek permissions from copyright holders itself sets a precedent. As I said, it’s common practice now. I assume there probably are still editors who would rather be safe than sorry and demand that the author obtain permissions for illustrations. I assume there are probably some authors who abide by that decision or who are themselves worried about copyright and so do seek and even pay for unnecessary permissions. As always in discussing this issue, I urge editors and authors not to seek permissions, since it sets a different and dangerous precedent, implying that fair use might not apply in such publications.

Second, there have been some interesting court cases which don’t involve film frames but which do suggest that fair use applies to the sorts of images that film scholars might wish to employ.

In August of 2006, a decision came down in the case “Christopher R. Harris v. San Jose Mercury News.” (See here for an article on the case from Communications Lawyer.) Like many other newspapers, the Mercury News had used a photograph from a book in a review of that book. The newspaper cropped the photo, including eliminating the copyright notice. Harris, the photographer, sued for infringement.

The closing argument was presented by Gary Bostwick, of the major law firm Sheppard Mullin Richter & Hampton, which works in, among other areas, entertainment law and intellectual property rights law. An abridgement of Bostwick’s argument for the reproduction of the photo as fair use is included in the article linked above. The article concludes: “The jury deliberated for only thirty-seven minutes before concluding that copying photographs from books for use in reviews was fair use.”

If a newspaper review can reproduce photographs, surely a scholarly book could claim an even greater right to do so.

Recently I sat down with my friend and colleague, James Peterson, of Godfrey & Kahn, S.C., who practices intellectual property rights law here in Madison. James got his Ph.D. in film studies at the University of Wisconsin. His dissertation (the committee for which David co-chaired along with J. J. Murphy) was subsequently published as Dreams of Chaos, Visions of Order: Understanding the American Avant-Garde Cinema (Wayne State University Press, 1994). The book contains frame enlargements, obviously vital in any attempt to analyze experimental films. James’s expertise in film studies and his subsequent law degree make him particularly attuned to the needs of scholars in the field and the rights involved in using images in academic publications.

During our conversation, I mentioned that many books using frame enlargements had been published since the SCS report was published. James responded:

On the frame enlargements issue, to me, really, although there’s no case law verifying the old SCS analysis from twenty years ago, I think it’s right. I don’t have any reason to doubt it. Now, I have a personal commitment to it myself, because I relied on it when I did my book. Nothing in my experience as a lawyer has led me to think otherwise … I think the position on frame enlargements is much more secure than on production stills. Marginally more at least.

I mentioned that David and I had also used production stills in our books without seeking permission. James responded:

I would think that those are fair, too. To me the biggest case is the Bill Graham Archives case (the district court case in the letter) and that was affirmed right down the line by the second circuit court of appeals. So to me that’s a huge fair-use case for scholars.

The case James refers to is one he cited to me in a letter summing up his opinions on the fair-use status of various kinds of illustrations that I wanted to use in The Frodo Franchise. The second circuit court of appeals he refers to is in New York, and it often handles major cases involving copyright law.

The case in question was “Bill Graham Archives v. Dorling Kindersley Limited, Dorling Kindersley Publishing, and RR Donnelley & Sons Company.” At issue were some illustrations in a book, Grateful Dead: The Illustrated Trip. This was a coffee-table cultural history of the band, done with the members’ cooperation. The book reproduced without obtaining permission seven images on which the Bill Graham Archives claimed copyright. There had in fact been some negotiations between the publishers and the archive, but as a fee could not be agreed on, the illustrations were reproduced without permission. The copyrighted images had been “originally depicted on Grateful Dead event posters and tickets.”

The court decided in favor of the publishers, declaring the reproduction of the seven images constituted fair use and thus upholding the lower court’s decision. In summing up, the court declared (using the four factors determining fair use listed above):

On balance, we conclude, as the district court did, that the fair use factors weigh in favor of DK’s use. For the first factor, we conclude that DK’s use of concert posters and tickets as historical artifacts of Grateful Dead performances is transformatively different from the original expressive purpose of BGA’s copyrighted images. While the second factor favors BGA because of the creative nature of the images, its weight is limited because DK did not exploit the expressive value of the images. Although BGA’s images are copied in their entirety, the third factor does not weigh against fair use because the reduced size of the images is consistent with the author’s transformative purpose. Finally, we conclude that DK’s use does not harm the market for BGA’s sale of its copyrighted artwork, and we do not find market harm based on BGA’s hypothetical loss of license revenue from DK’s transformative market.

James expressed his opinion about the decision: “At least on the use of illustrative material, I think that case is very powerful.”

Powerful indeed, because it suggests that film scholars would be justified under fair use even if they reproduced whole production photos, posters, and other visual material directly related to the discussion in the text of their book or article, all without seeking permission.

I mentioned the widespread use of frame enlargements and photographs on the internet, particularly on fan websites. James gave his opinion on the use of photos on websites and then on our blog particularly:

The stock-photo houses are best positioned to complain about that activity, because they’re in the business of selling into that market. So if you want to illustrate something on your website, you shouldn’t just snatch it and stick it on the website.

You guys are, to my way of thinking–what you are doing is almost infringement-proof, because you’re unimpeachably scholarly and you’re writing about the things that you’re copying. It would be different if you were just using it to illustrate your website. I think a lot of the fan sites might fall into that category. They’re not connecting scholarship about the thing. They’re using the things they’re copying to attract attention to their own work. That, I think, is a different enterprise.

All of this is good news for cinema studies. So yes, things have happened since 1993 that would change the situation for film scholars, and it’s all for the better. Fair use is obviously alive and well, and those of us who need to reproduce the images we discuss can do so. Let’s all go analyze a film!

Note: Important policy statements on fair use in related areas have been released in the past few years. For the use of copyrighted material in documentary films, see the Center for Social Media’s “Documentary Filmmakers’ Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use” (2005) and its follow-up on the statement’s impact.

In 2007, the Society for Cinema and Media Studies released a statement targeted at classroom teaching: “The Society for Cinema and Media Studies’ Statement of Best Practices for Fair Use in Teaching for Film and Media Educators,” in Cinema Journal Volume 47, no. 2 (2008) or online.

Happy birthday, classical cinema!, or The ten best films of … 1917

Wild and Woolly (1917).

KT:

Periodization is a tricky task for historians, and there are a lot of disputes about how to divide up the 110-plus years of the cinema’s existence. We all have to deal with it, though, if we want to organize our studies of the past into meaningful units. How to do that?

Do we divide the periods of film history according to major historical events? World War I had a huge impact on the film industry, to be sure, and we might say that one significant period for cinema is 1914-1918. Yet 1919 didn’t mark the start of a new period. The major European post-war film movements didn’t start then. French Impressionism arguably began in 1918, German Expressionism in 1920, and Soviet Montage in 1924 or 1925.

Carving up film history partly depends on what questions the historian is asking. If you’re studying wartime propaganda, 1914 and 1918 would provide significant beginning and end points. If you want to trace the development of significant film styles, it doesn’t seem very useful.

While historians have difficulties agreeing on periodization, just about everyone concurs that there were two amazing years during the 1910s when filmmaking practice somehow coalesced and produced a burst of creativity: 1913 and 1917.

One can point to stylistically significant films made before 1913. Somehow, though, that year seemed to be when filmmakers in several countries simultaneously seized upon what they had already learned of technique and pushed their knowledge to higher levels of expressivity. “Le Gionate del Cinema Muto” (“The Days of Silent Cinema”), the major annual festival, devoted its 1993 event to “The Year 1913.” The program included The Student of Prague (Stellan Rye), Suspense (Phillips Smalley and Lois Weber), Atlantis (August Blom), Raja Harischandra (D. G. Phalke), Juve contre Fantomas (Louis Feuillade), Quo Vadis? (Enrico Guazzoni), Ingeborg Holm (Victor Sjöström), The Mothering Heart (D. W. Griffith), Ma l’amor mio non muore! (Mario Caserini), L’enfant de Paris (Léonce Perret), and Twilight of a Woman’s Soul (Yevgenii Bauer). .

1917, by contrast, was primarily an American landmark. As 2007 closes, we thought it appropriate to wish happy birthday to the most powerful and pervasive approach to filmic storytelling the world has yet seen. That would be classical continuity cinema, synthesized in what was coming to be known as Hollywood.

DB:

In The Classical Hollywood Cinema and work we’ve done since, we’ve maintained that 1917 is the year in which we can see the consolidation of Hollywood’s characteristic approach to visual storytelling. This idea was first floated by Barry Salt, and our research confirms his claim. Over the ninety years since 1917 the style has changed, but its basic premises have remained in force.

Before classical continuity emerged, the dominant approach to shooting a scene might be called the tableau technique. Action was played out in a full shot, using staging to vary the composition and express dramatic relationships. Elsewhere on this site I’ve mentioned two major exponents of this approach, Feuillade and Bauer.

When there was cutting within the tableau setup, it usually consisted of inserted close-ups of important details, especially printed matter, like a letter or telegram. Occasionally the close-up of an actor could be inserted, usually filmed from the same angle as the master shot. The tableau approach was more prominent in scenes taking place in interiors; filmmakers were freer about cutting action occurring outdoors.

We shouldn’t think of the tableau as purely “theatrical.” For one thing, the master shot was typically closer and more tightly organized than a scene on the stage would be. Moreover, for reasons I discuss in Figures Traced in Light, the playing space of the cinematic frame is quite different from the playing area of the proscenium theatre. The filmmaker can manipulate composition, depth, and blocking in ways not available on the stage.

The tableau approach was the default premise of US filmmaking through the early 1910s. You can see it at work, for example, in this shot from At the Eleventh Hour (W. V. Ranous, 1912). Mr. and Mrs. Richards are in the study of Mr. Daley. After Richards has refused to sell his railroad bonds, Daley’s wife shows off her diamond necklace to the visitors.

At first the two couples are separated in depth, the men in the foreground and the women further back. In the first frame below, a new necklace has just been delivered, and a servant gives it to Mrs. Daley. Only the servant’s hand is visible, as she is blocked by Richards in the foreground. In the second frame, the two women come forward. Mrs. Daley holds the necklace up and Mrs. Richards oohs and ahhs over it, while her husband glances at Daley as if to wonder how he could afford it.

Instead of breaking the scene into closer views, spreading the characters’ reactions across separate shots, Ranous squeezes all of their actions and expressions into a tight space across the center of the shot. Nor does he provide a close-up of the necklace, which will be important in the plot. (1) We might be inclined to say that this is a “theatrical” shot, but on a stage the actions in depth (the women chatting, the servant handing over the parcel) wouldn’t be visible to everyone in the auditorium. Likewise, on a stage the packed faces in the later phase of the scene wouldn’t be visible to people sitting on the sides.

As films became longer, American filmmakers were starting to organize their plots around characters with firm goals. Conflicting goals would set the characters in opposition to one another, and at a climax, usually under the pressure of a deadline, the protagonist achieves or fails to achieve the goals. The plot also tends to build up two lines of action, at least one involving romance.

There’s no reason this conception of narrative could not have been applied to the tableau style; in many cases it was. But hand in hand with the rise of goal-driven plotting came a new approach to filming. Sporadically before 1917, filmmakers in many countries were exploring ways to build scene out of many shots. (If you want to know the process in the US in more detail, check out Early American Cinema in Transition by Charlie Keil.) By 1917, American filmmakers had synthesized these tactics into an overall strategy, a system for staging, shooting, and cutting dramatic action.

We know the result as the 180-degree system. This encourages the filmmaker to break a scene into several shots, taken from different distances and angles, all from one side of an imaginary line slicing through the space. Around 1917, this stylistic approach comes to dominate US feature films, in the sense that every film made will tend to display all the devices at least once. The system remains in place to this day, and it came to form the basis of popular cinemas across the world. (2)

Once you break a scene into several shots, some characters won’t be onscreen all the time. So you need to be clear about where offscreen characters are; you need to supply cues that allow the audience to infer their positions. So 1910s filmmakers developed various ways of “matching” shots.

Shots can be connected by character looks, thanks to the eyeline match. Here’s an instance from Victor Schertzinger’s The Clodhopper (1917). First there is a master shot of the mother and son in their farm kitchen.

This is followed by a separate shot of each one. Their bodily positions and eyelines remind us that the other is just out of frame.

Although over-the-shoulder shooting hadn’t yet been developed, a conception of the reverse angle is at work here too. Schertzinger’s camera doesn’t shoot the actors perpendicularly, but takes up an angle on one that becomes an echo of that filming the other. Here’s another example of reverse angles from The Devil’s Bait (1917, director Harry Harvey).

The camera doesn’t just enlarge a portion of the space, as in the inserted shot in a tableau scene. The angle of view has changed significantly.

Changes of angle within the scene have become fairly complex by 1917. This strategy is apparent when the action takes place in a theatre, a courtroom, a church, or some other large-scale gathering point. The camera position changes often in this scene from The Girl without a Soul (director John Collins).

The concept of matching extends to physical movement too, through the match on action. This device allows the director to highlight a new bit of space while preserving the continuity of time. In Roscoe Arbuckle’s The Butcher Boy, the cut-in to Fatty (with a change of angle) also matches his gesture of putting his hands on his hips.

Interestingly, even this early, directors have learned to leave a little bit of overlapping action across the cut. If you move frame by frame, you’ll see that Fatty’s gesture is repeated a bit at the start of the second shot.

When a character leaves one frame, he or she can come into another space, from the side of the frame consistent with the 180-degree premise. This is matching screen direction. A cut of this sort lets us know that the next portion of the locale that we see is more or less adjacent to the previous one. In Field of Honor (director Allen Holuban), Wade crosses to Laura, who’s waiting in a carriage. A few years earlier, the director might have presented his greeting in a single deep-space long shot. Instead, Wade exits one shot and enters the next.

Again, the reverse-angle principle governs the camera setups. Wade moves along a diagonal toward the camera and away from it.

More generally, Field of Honor exhibits a polished handling of the new style: lots of reverse shots and eyeline matches, fades that bracket flashbacks, binocular points of view, rack-focus shots, and rapid cutting (there’s even a ten-frame shot). The point is not to claim Field of Honor as an undiscovered masterpiece but rather to indicate that by 1917 a director could handle all the devices with assurance.

Match-cutting devices had been used occasionally before 1917, but by that year filmmmakers melded them into a consistent and somewhat redundant method of guiding the audience through each scene.

The continuity system not only creates a basic clarity about characters’ positions. It can as well generate a speed and accentuation not easily achieved within a single shot. For example, Wade’s frame exit and entrance above is cut so as to skip over moments that he consumes crossing the driveway. Continuity editing enhances the rapid pace of US films, a quality immediately noted by foreign observers in the 1910s and 1920s.

Two of the best films of 1917 exploit the dynamism of continuity cutting. The Doug Fairbanks comedy western, Wild and Woolly, seems designed to prove that American films could proceed at breakneck speed. In climactic scenes, we’re caught in a whirlwind of fast cutting, with the pace set by the hyperactive protagonist, a financier’s son who longs to prove himself as a cowboy.

John Ford’s Straight Shooting proceeds at a more measured pace, but in its final shootout we see a prototype of all the main-street gundowns that will define the Western. Ford provides alternating shots of the cowboys advancing toward each other, framing each man more tightly and concluding with suffocating close-ups of each man’s face, highlighting the eyes.

Sergio Leone, eat your heart out.

Propelled by goal-driven characters and a linear arc of action, films like Wild and Woolly and Straight Shooting are completely understandable and enjoyable today. (But when will we have them on DVD?) Their stories are engrossing and their performances are engaging, but just as important their storytelling technique has become second nature to us. The narrative strategies that coalesced in 1917 remain fundamental to mainstream cinema.(2)

The Mystery of the Belgian Print

KT:

For decades now we have been visiting Brussels and working at the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique/Koninklijk Belgisch Filmarchief. Sometimes I feel that we would know half as much about the cinema were it not for the unfailing hospitality we have been shown, initially by the great archivist Jacques Ledoux and now by his successor Gabrielle Claes. Our indebtedness to this institution and its staff are reflected in David’s named professorship; he is the Jacques Ledoux Professor of Film Studies. We dedicated our Film History: An Introduction, to Gabrielle.

We do whatever favors we can in return for such wonderful help. David lectures regularly at the biannual summer school run by the Flemish Service for Film Culture in partnership with the Royal Film Archive. (David wrote about the 2007 event in an earlier entry.) I try to identify silent films. I am not always successful, but I suppose over the years I have been able to put names to thirty-some mystery prints.

Silent films are more likely to be unidentified than sound ones because it was standard practice to splice in intertitles in the local language. Sometimes too the film’s title was changed. The film’s actors may be forgotten today, or the print may be incomplete, lacking the opening title and credits. Sometimes even the country of origin is unknown.

Back in the early 1990s I was asked to identify a five-reel nitrate print with the title Père et fils. It was an original distribution copy from the silent era. The information on the archival record card listed some possible identifications: Father and Son, a 1913 Vitagraph film or Father and Son, produced by Mica in 1915. It was tentatively thought to be American.

As I watched the film, it quickly became apparent that it was indeed American. It centered on the rivalry between a small dime store owned by the heroine’s father and a modern dime store being built in the same town. The hero is charged with the mission of driving the older store out of business.

So we had our typical goal-driven plot. The style was what David has described as typical of 1917, so that was my tentative dating. I felt almost certain that the reels I was watching were not from a 1913 or 1915 movie. The film was a fairly modest item, done on a relatively low budget and not starring any actors that would be familiar to most modern viewers. I had seen the actor playing the hero before, however, and I thought he might be Herbert Rawlinson. By the time I finished the film, those were my clues: a medium-budget American film of c. 1917 concerning dime stores and perhaps starring Rawlinson.

My task turned out to be fairly simple. A little research after we returned home confirmed the Rawlinson guess. In preparing the write The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I had seen him in The Coming of Columbus (a 1912 Selig film) and in Damon and Pythias (Universal, 1914).

My next step was to consult the monumental, indispensible reference book, The American Film Institute Catalog. This multi-volume set, many years in the making, was originally published as books. It is now online, but available only to AFI members or through libraries. The catalogues were published by decade—thus obviating the problem of periodization. Each decade gets two volumes, one of entries on all the films, listed in alphabetical order. Credits, production companies, release dates, plot synopses, and other information are included. A second volume indexes the films by chronology, personal names, corporate names, subject, genre, and geography (i.e., where the films were shot).

Until now I had found little use for the subject index, but now it came to my aid. I turned to the Ds to see if there was an entry for dime stores. The AFI indexers were thorough, and sure enough, there was one entry: Like Wildfire. A check of the personal names index under Rawlinson, Herbert revealed that he had acted in a film called Like Wildfire, made in 1917 by Universal. Once I had the title, I checked its catalog entry and found that its plot description matched the film I had seen. Case closed.

Admittedly, in this instance the date wasn’t a crucial clue. Still, determining a film’s year of release can narrow down the possibilities. Thanks as well to the development of classical cutting, a close view of an actor helps in identifying him.

The Best of 1917

DB:

This is the season when everybody makes a list of best pictures. We have stopped playing that game. For one thing, we haven’t seen all the films that deserve to be included. For another, the excellence of a film often dawns gradually, after you’ve had years to reflect on it. And critical tastes are as shifting as the sirocco. Never forget that in 1965 the Cannes palme d’or was won by The Knack . . . and How to Get It.

Still, enough time has elapsed to make us feel confident of this, our list of the best (surviving) films of 1917, both US and “foreign-language.” Titles are in alphabetical order.

The Clown (Denmark, A. W. Sandberg)

Easy Street (U.S., Charles Chaplin)

The Girl from Stormycroft (Sweden, Victor Sjöström)

The Immigrant (U.S., Charles Chaplin)

Judex (France, Louis Feuillade)

The Mysterious Night of the 25th (Sweden, Georg af Klercker)

The Narrow Trail (U.S., Lambert Hillyer)

The Revolutionary (Russia, Yevgenii Bauer)

Romance of the Redwoods (U.S., Cecil B. De Mille)

Terje Vigen (Sweden, Victor Sjöström)

Straight Shooting (US, John Ford)

Thomas Graal’s Best Film (Sweden, Mauritz Stiller)

Wild and Woolly (US, John Emerson)

Next year, maybe we’ll draw up our list for 1918.

(1) For more on this scene and the film as a whole, see Kristin Thompson, “Narration Early in the Transition to Classical Filmmaking: Three Vitagraph Shorts,” Film History 9, 4 (1997), 410-434.

(2) Beyond The Classical Hollywood Cinema, see Kristin’s Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood and Storytelling in the New Hollywood. I’ve talked about these issues in On the History of Film Style, Planet Hong Kong, Figures Traced in Light, The Way Hollywood Tells It, and essays included in Poetics of Cinema. The basics of classical continuity are presented in Chapter 6 of Film Art: An Introduction, and we trace some historical implications of it in Film History: An Introduction.

Scribble, scribble, scribble

Detective (Godard, 1985).

Another damned, thick, square book! Always scribble, scribble, scribble, eh, Mr. Gibbon?

William Henry, Duke of Gloucester, 1781.

David here:

Kristin kept the blogfires burning while I traveled last week and did UW duties this one. I had a great time at the University of Georgia in Athens (but didn’t see Stipe) and at Emory in Atlanta (but didn’t see Scarlett). At both places I met sharp, energetic students and faculty. I have a couple of blog entries backlogged for posting, but now recent items relating to publications get the pole position.

First, a Japanese translation of our Film Art: An Introduction has just appeared. It’s a very handsome version of the seventh edition, rendered by Fujiki Hideaki and Kitamura Hiroshi. We’re grateful to them and to Nagoya University Press for publishing it.

First, a Japanese translation of our Film Art: An Introduction has just appeared. It’s a very handsome version of the seventh edition, rendered by Fujiki Hideaki and Kitamura Hiroshi. We’re grateful to them and to Nagoya University Press for publishing it.

Second, the University of California Press is having a big sale on many outstanding media titles, from Richard Abel’s books on French silent cinema and André Bazin’s classics of film theory to Michele Hilmes’ study of NBC television and Mike Barrier’s new Disney biography, The Animated Man. To get the discount you must sign up for an e-newsletter, but it’s not intrusive.

Among the books of mine on sale, the biggest bargain is the hardcover edition of Figures Traced in Light (2005), originally priced at $65, now going for $7.95 plus postage. (No, apparently I don’t get the full-price royalties.) You can find this item here. There are also paperback copies of Figures (going for $12.95) and of The Way Hollywood Tells It ($15.95). If you’re inclined, hurry: the sale ends on 31 October.

The biggest news, though, is that I just got my author’s copies of Poetics of Cinema, published last week. For a while Amazon was telling some people who pre-ordered it that copies won’t be available until 27 December, but now, despite what it says here, the book seems ready to ship.

The biggest news, though, is that I just got my author’s copies of Poetics of Cinema, published last week. For a while Amazon was telling some people who pre-ordered it that copies won’t be available until 27 December, but now, despite what it says here, the book seems ready to ship.

Bad news first. Poetics of Cinema is priced at $45 in paperback, with no sellers I know offering it at discount. Go ahead, say it: Very expensive. If you haven’t published a book, you may not know that authors have no say in the pricing of their work. Publishers would never set a price or price ceiling in a contract, and calculations about pricing are based on many factors, including what comparable books sell for. A high cost isn’t my preference, of course; every writer wants to reach as many readers as possible. But unless you blog or self-publish your work, the publisher sets the price.

There are some good reasons for the cost. Running to 500 fairly dense pages and containing over 500 photographs, Poetics of Cinema was a complicated book to produce. I peddled it to other publishers, but they ruled it out as too whopping an investment for them. So Routledge has priced it along lines of comparable books, reckoning in the size of the likely audience (I hope, more than 118.3 readers). I have to thank Bill Germano, then Publishing Director at Routledge, for taking a chance on this project.

From age fifteen or so I’ve been a compulsive writer. Scribble, scribble, scribble. I’ve been at work on one book or another for over thirty years. I’ve got several projects in mind for my next effort, but I’ve held back committing. Is there any point in publishing more books, at least as books?

I mean this as a serious question. Would it have made any difference to me or my readers if Poetics of Cinema appeared as pdfs, available at a price considerably less than $45? Wouldn’t I find more readers? What about variable pricing? If Radiohead can do it, why can’t I? Somebody in film studies should try putting a digital book for sale online; maybe I will. But for a few years at least, this last baggy monster will be available only in dead-tree format.

Poetics: Some puzzles

Gentlemen Marry Brunettes (Richard Sale, 1955).

If you’ve read this far, you may be interested in what the book is about. Most basically, it’s predicated on the belief that we make progress in research by asking questions. Some questions are too deep to be answered—call them mysteries—but others can be answered with a fair degree of precision and reliability. We can turn mysteries into puzzles and puzzles into plausible answers.

Here’s a fairly common sort of composition in Hollywood cinema of the 1940s. This shot from The Killers (1946) displays the sort of steep depth I’ve talked about at various points on this blog and in my other books.

But now here’s an equally tense confrontation at a counter, from Bad Day at Black Rock (1955), made in early CinemaScope.

It doesn’t look much like the 1940s shot. The characters stand far from us, and the figure in the foreground doesn’t loom over the background. The shot is more open, the composition more porous. And unlike The Killers, Bad Day doesn’t contain close-ups of the actors in any scenes.

So questions come to mind. Did John Sturges have to stage the scene in Bad Day this way? Did other filmmakers resort to the same choice? What factors created pressures toward this more spacious format? Could more resourceful filmmakers have done something different? And given that such shots are rare today, what changes made it possible for filmmakers in later years to create the tight anamorphic widescreen close-ups we have now (as here in Cellular)?

Despite all that has been written about CinemaScope and other early widescreen processes, no one has explored, shot by shot, what staging options were used by filmmakers. A chapter in Poetics of Cinema called “CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See Without Glasses” tries to show how filmmakers used the new format to tell their stories. This led them, I propose, to experiment with some staging strategies that, surprisingly, had precedents as far back as the 1910s.

Take another instance. We’re all familiar with recent films that present alternative futures, like Run Lola Run. A story line runs along and then is interrupted, and we switch to the same characters living a different storyline in a parallel universe. The emergence of such “forking path” movies arouses my curiosity. How do they work? How do they make their alternative-reality stories intelligible to the audience? How is it that we’re able to understand them? (After all, the notion of an infinite number of alternative universes to ours is pretty hard to get your head around.) Are such stories a brand-new innovation, or do they have precedents? (Clue: Remember A Christmas Carol?) Why do we see a cluster of these emerging in recent filmmaking?

I tackle these questions in another essay, called “Film Futures.” There I look at several such movies and try to spell out the tacit rules that filmmakers follow and that audiences pick up on. While this story format probably doesn’t constitute a genre, it does obey certain conventions, and I try to chart those. Some films also make some clever innovations in the format, which I also try to trace. The essay as well suggests how the conventions are handled differently in mass-market films like Sliding Doors and in art films like Kieślowski’s Blind Chance.

These two essays, along with the others in the book, try to explain and illustrate an approach to film studies I call film poetics. At bottom, this is an effort to explain why films are designed the way they are: how filmmakers have made certain choices in order to shape our response to their films. How do movies work? How do movies work on us?

Poetics: The project

Vagabond (Varda, 1985).

As a kind of reverse engineering, film poetics looks at both structure and texture. I argue that we ought to study how films are constructed architecturally, as revealed for instance in plot structure or narration. Poetics also concentrates on stylistic patterning, the way filmmakers organize the techniques available to the medium. Poetics traditionally deals as well with thematics, the subjects and ideas that are mobilized by filmmakers and reworked by large-scale form and cinematic style.

Put it this way: I want to know how filmmakers have confronted problems set by others, or created problems for themselves to solve. I want to know how they draw on the past to borrow or modify or reject creative strategies. I want to know filmmakers’ secrets, including the ones they don’t know they know. And I want to know how all this creative activity is shaped to the uptake of spectators in different times and places.

Some of what I’ve written on this blog could illustrate how the poetics-driven perspective works in particular cases. The book offers more such instances, probed in more detail than is possible here. Using a comparative method, I also trace out some general principles of film form and style as they have developed over history.

The book consists of fifteen essays. Some have been published before; those have been revised for this collection. Other essays are newly written. After a somewhat polemical introduction, the first part concentrates on some theoretical problems. The anchoring essay offers a general introduction to the idea of a film poetics, with several examples. (An earlier version is on pdfs here.) In the same essay, I float a model of how film viewers respond to various aspects of films. I distinguish activities of perception, comprehension, and appropriation, and I suggest that a cognitive perspective sheds light on them.

Part I also contains an essay considering how cinematic conventions work. A poetics-based approach will spend a lot of time on norms, traditions, and received routines, for these are often the basis of filmmakers’ creative choices. This essay argues that some conventions are local and require a lot of cultural knowledge, while others are cross-cultural, compelling us to study why certain cinematic strategies seem to crop up across the world.

The second part of Poetics of Cinema considers narrative, one of the most common ways in which films are organized to affect viewers. I wrote a new essay to launch this section, a wide-ranging study called “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative.” The three dimensions I consider are narration, plot structure, and the narrative world. The essay considers how each of these shapes our understanding of a film’s story. This essay ends with a discussion called “Narrators, Implied Authors, and Other Superfluities.”

Some more tightly-focused pieces follow. One is devoted to forking-path plots. Another concentrates on an odd question: What role does forgetting play in our watching a film? Cognitive theory can offer some answers, and I take Mildred Pierce as an example. There’s an update of an essay that has been something of a golden oldie in film courses, “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice.” In a supplement to that piece I suggest some new avenues of inquiry and draw on more examples, notably Varda’s Vagabond (Sans toit ni loi).

The longest piece in Part II is devoted to what I call network narratives. Prototypes of this would be Grand Hotel, Short Cuts, Crash, and Babel. This essay tries to show how a poetics of cinema shed light on this format, currently a very popular one. When I started looking at these movies, I was surprised to discover how many filmmaking traditions work in this vein; I append a filmography with nearly 250 items, and today I could update it with several more. (1) I consider how this option has developed distinctive strategies of narration, plotting, and worldmaking. I also survey some common themes running across network tales, such as the role of chance and fate. The essay finishes with more in-depth analyses of four films: Altman’s Nashville, Iosseliani’s Favoris de la lune, Anderson’s Magnolia, and Jean-Claude Guiget’s Les Passagers.

Poetics: More problems

Bus Stop (Logan, 1955).

Part III moves from questions of narrative to questions of film style, no stranger to this blog. The opening essay is a tribute to Andrew Sarris that appraises his role in making readers of my generation style-conscious. It’s the most personal piece in the book. There follows a study of Robert Reinert, a director in the German silent cinema who might have become much better known if his quite demented Nerven and Opium had been as widely seen as Caligari. The essay “Who Blinked First?” considers how our reaction to films is affected by the ways in which actors use their eyes, including how and when they blink. Big deal, huh? Actually, yes.

The monster essay in this section is the CinemaScope piece, of which I’ve given versions in lecture form over the last couple of years. I argue that some directors responded to the new widescreen technology by adapting certain norms of staging and shooting to the new format, while other filmmakers moved in more adventurous directions. The piece uses the model of problem/solution as a way to understand stylistic continuity and change, a framework I’ve floated in On the History of Film Style as well.

The last four studies in Part III are devoted to style in Asian cinema. There are two essays on Japanese film of the 1920s and 1930s, both expanded somewhat from their original versions. There I argue that we can see Japanese directors as building upon, as well as adventurously departing from, stylistic norms shared by most filmmaking countries of the period. This brace of essays fills out some ideas that I fielded in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, and they should appeal to that growing body of viewers who have developed a passion for Naruse Mikio and Uchida Tomio. It’s gratifying that several of the films I discuss, which I had to study in archives, are now circulating in touring programs.

Poetics of Cinema concludes with two studies of Hong Kong film, one surveying the stylistic tactics by which that very lively tradition excites its audience, the other analyzing the unique innovations of King Hu. The articles are companion pieces to Planet Hong Kong.

Poetics: The mysteries

A Touch of Zen (King Hu, 1970).

As an approach to answering questions about cinema, poetics blends history, criticism, and theory. It requires that we do research into the artistic history of film, looking at styles, genres, narrative modes, and other traditions. It asks for close analysis and interpretation of films. At the same time, it asks broader questions about what principles govern narrative, stylistic patterning, and the like. I’d say it obliges a historian to concentrate on aesthetics; it makes criticism more historical and theoretical; it ties theory to concrete historical conditions and the fine-grain workings of individual films.

Kenneth Burke used to say that you could get a sense of a book by looking at its first and last sentences. My book’s first essay opens this way:

Sometimes our routines seem transparent, and we forget that they have a history.

I think that this captures my concern to look closely at familiar things in film and try to make their principles a little more evident. Yet in trying to make filmmakers’ choices explicit and tracing out the principles undergirding how we make sense of movies, I’m sometimes criticized for simply stating common sense. Poetics can look bland alongside the skywriting swoops of most academic film theory. But skywriting is blurry and dissolves while you look at it. By contrast, clearly setting out some basics of filmic construction and comprehension offers a firmer place to start answering questions about how movies work and work on us.

Poetics tries to produce concrete, approximately true claims about cinema. Most film theory operates as an application, borrowing big theories of culture, identity, nationhood, and the like and then mapping them onto films. The results are usually thin. It seems to me that most film theory today is not carefully thought through or persuasively argued. For examples, see my essay in Post-Theory, the last chapter of Figures, and my comments here and here on this site.

In trying to establish reliable knowledge about cinema, we won’t answer every question and we will make false steps, but we can make progress. Film poetics is one way we film enthusiasts can join that tradition of rational and empirical inquiry which remains our most dependable path to knowledge. My introduction, though peppered with some pokes at Big Theory, has the serious purpose of making a plea for film scholars to join that tradition.

The final line of the book concludes the essay on King Hu:

The mainstream [Hong Kong] style has given us many beautiful and stirring films, but Hu’s eccentric explorations evoke something that other directors’ works seldom arouse: a sense that extraordinary physical achievement, if caught through precisely adjusted imperfections, becomes marvelous.

To get the full point you need to read the essay, but what should come through here is my concern to highlight filmmakers’ originality when I find it, and to locate it by means of a comparative method. In addition, I hope that what comes through is an appreciation of the sheer exhilaration we feel when a filmmaker has made the right, bold choice. A poetics-based approach probably can’t fully explain this feeling—it may fall under the heading of mysteries rather than puzzles—but at least it can reveal how some forces contribute to it.

My summary, and the size of the book, may leave the impression that I think that I’ve answered these questions fully. Of course I don’t. I try only to make some progress, realizing that offering answers is also an invitation to disagree, to refine the questions and tackle new ones. Nor do I think that these are the only questions that matter. We’re just starting to understand how films work and work on us, and there are a great many areas we haven’t charted. (Performance, to take a big one.) We have to start somewhere, though. I’d hope that by posing some questions and proposing some answers, Poetics of Cinema offers fruitful points of departure.

(1) Some candidates are 25 Fireman Street (1973, Hungary, István Szabó), Feast of Love (2007, US, Robert Benton), Continental—A Film without Guns (2007, Canada/ Stephane Lafleur), The Edge of Heaven (2007, Germany/ Turkey, Fatih Akin), Unfinished Stories (2007, Iran, Pourya Azarbayjani), God Man Dog (2007, Taiwan, Singing Chen [Chen Hsin-hsuan]), A Century’s End (2000, Korea, Song Neung-han), and Why Did I Get Married? (2007, US Tyler Perry).

A Moment of Innocence (Mohsen Makhmalbaf, 1996).