Archive for the 'Film scholarship' Category

Sweet 16

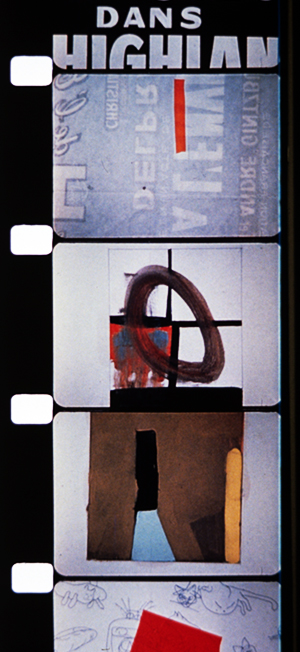

REcreation (Robert Breer, 1956); T.O.U.C.H.I.N.G (Paul Sharits, 1969).

DB here:

Snows and thaws and refreezing, amplified by a torrential rain, gave water a new path into our basement. We’ve spent about two weeks emptying bookshelves, drying them out, and shifting books to other places. No volumes were damaged, but we had to make space in the dry areas for the migrant titles.

That meant facing up to the problem of 16mm.

The solution was drastic.

Narrow-gauge movies

My film collecting started with 8mm. Not super-8; that was invented later. (Imagine how old I am.) I made my own movies in 8, but I also bought, from the venerable Blackhawk Films of Davenport, Iowa, copies of films in that format. Most memorable was the Odessa Steps reel from Battleship Potemkin, which I projected often on my bedroom wall.

Not until I went to college and joined a film club did I lay my hands on 16mm. I suppose if you start out handling 35mm, 16 looks skinny and 8 looks like a toy. But moving from 8 to 16, I could see only improvement. You could, with the sharp eyes of the teenage geek, actually see the image on the strip. I projected many films on our JAN surplus projectors, and one weekend I hauled a print of Citizen Kane to my apartment to watch several times. Do I need to add that all this was in the 1960s, long before films became available on videotape?

Arriving in Madison in 1973, Kristin and I bought a Kodak Pageant, the 16mm workhorse. Not as good as a Bell & Howell, most aficionados would tell you, but fairly cheap and easy to handle. When we moved from apartment to apartment, the Pageant went with us.

In 1977 we bought a house, and I set up a jerry-rigged projection room in the unfinished basement. In our second house, where we still live, I was able to set up something more permanent. Now there were two projectors encased in a booth and mounted on a platform.

We spent many hours watching movies in that currently soggy basement, with its burgundy carpet and dark wood paneling. Although the room lacked the comforts of what we think of as a home theatre, we sometimes screened things for big groups, either a party or once in a while students in a seminar.

In both venues, we previewed movies we were showing in courses and revisited some of our growing collection: The Shop Around the Corner, High and Low, True Stories (must blog about that some time), You Only Live Once, and so on. I’ve already expounded on the key role of His Girl Friday in our mini-cinémathèque.

By then Kristin and I had also started working with 35mm prints in archives and with 35mm trailers we scavenged to make slides for lectures. For a brief while we even had 35mm in our screening space, but with only one projector, shows stretched too long. Although home video had taken off, Betavision, VHS, and even laserdiscs couldn’t compare to a good 16 copy. We continued to collect and show on film, as did our department.

In the last decade, improvements in digital projection, along with the arrival of Blu-ray, led to the decline of 16 in our local media ecosystem. Our department still shows a lot of 35, but 16 seems mostly the province of our experimental and documentary courses. As for us, we hadn’t screened 16 at home for some years. Then came the February leak, and we had to face the problem.

We’d already given many of our 16mm titles to the department, keeping our most fond treasures at home, thinking we’d watch them some day. Now we needed the space that those cans and cases occupied. Anyhow, it was probably time to let go. So we decided to surrender the features, the shorts, the cartoons, the splicers and the rewinds and the six Pageants—everything.

Our house is a museum of defunct technology. Just recently I surrendered my lovely Teac reel-to-reel tape recorder. Packed away are hundreds of Beta and VHS tapes. On groaning shelves sit hundreds of laserdiscs, mostly Asian. Yet under a roof that houses no fewer than six laserdisc players, there is no trace of the predominant nontheatrical film format of the twentieth century.

FOOFs

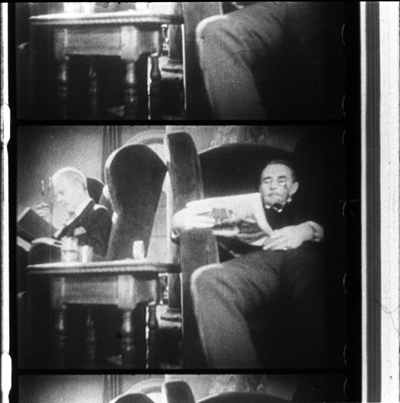

Captain Celluloid vs. the Film Pirates (1966).

Nowadays it’s easy to own a “film”—or rather a disc or file or stream of pixels fed to your display. (Though I wonder what it means to “own” something sitting on the Cloud in your virtual locker.) Back in the day, joining the ranks of 16mm collectors meant a real commitment. You needed to buy gear, you needed to clean and inspect the films, and you needed to learn a little projector maintenance. You probably subscribed to The Big Reel and Classic Film Collector, tabloids that ran ads selling or swapping prints and equipment. And you usually went to film collectors’ conventions, jamborees of selling, trading, and movie watching. The three biggest events, Cinecon (Los Angeles), Cinefest (Syracuse), and Cinevent (Columbus, Ohio), brought together the overwhelmingly male tribe of FOOFs: Fans of Old Films.

FOOF collectors had good hunting in those days. There were plenty of 16mm prints floating around, but quality varied. The best were those cast off from legit distributors. Made from internegatives drawn from 35mm positives, they usually had good tonal values. At the other end of the scale were the dupes, copies pulled from 16mm distribution prints. These ranged from acceptable to awful; but if you wanted a rarity, you might have to spring for a dupe.

In the middle zone were TV prints, probably the majority of copies in circulation. When studios licensed their pre-1948 libraries to television, go-between companies like C & C put together packages of prints to be sold to local stations around America. Small stations in the hinterlands harbored scores of 16mm copies, to be trimmed, filled out with commercials, and broadcast outside prime time, and sometimes within it as “Million Dollar Movie” or whatever. It’s still not fully appreciated, I think, how many baby-boomer auteurists around the country caught classics in the pre-dawn hours on local television.

But as network and syndicated programming expanded, there was less room for old movies. Why run a 1936 Paramount picture when you could show color re-runs of Bewitched or The Six Million Dollar Man? The stations’ 16mm prints were headed for landfill when enterprising collectors and entrepreneurs salvaged them. You could tell when you got a TV print. It might carry a packager’s logo; it would have low contrast; and splices between scenes would signal where the commercials had been jammed in.

FOOFs had their demons and demigods. Principal among the demons was one colorful character, who had the habit of bothering collectors circulating versions of old classics to which he claimed current rights. In The Sneeze, FOOFs made fun of the man who, releasing recovered prints of Birth of a Nation and Keaton films, made sure his own name featured prominently in the credits.

Among the demigods were Kevin Brownlow, he who had rescued Napoleon, and David Shepard, who started out at Blackhawk and eventually founded Film Preservation Associates. Most legendary of collectors was William K. Everson, who died in 1996. Thousands of prints were squeezed into his two Manhattan apartments and spilled over into the storage areas of NYU’s film department. He acquired many of his films in exchange for services he rendered to Hollywood studios. His gems were screened in his courses, in sessions of the Theodore Huff Memorial Film Society, and in lectures he presented around the world. I remember his excellent presentation on Joseph H. Lewis at Chicago’s Art Institute Film Center, where he showed clips from Lewis’ Poverty Row productions and even some credit sequences Lewis had crafted.

Bill brought a magnificent selection of titles to Madison in the early 80s, and many of them, such as Bulldog Drummond (1929) and Justin de Marseille (1935), remain rarities. Generous beyond measure, he also let NYU faculty and students borrow his movies. When Annette Michelson needed to see East of Borneo (1931) for her essay on Joseph Cornell’s Rose Hobart (1936), she turned to Bill. All of this largesse was made possible by the portable, user-friendly format of 16mm.

Freezing the frame

Teachers, filmmakers, and collectors had a special relation to 16mm. In addition, as researchers, we developed an unusually intimate rapport with the format. When I started teaching, I felt the need to illustrate my lectures with images from the films. My first efforts involved setting up a 35mm still camera on a tripod and photographing from the screen. If the projector could stop on a frame, so much the better; but even if not, you might snag an acceptable shot. The projected image would be surrounded by darkness. Today I wince at the results, as with this shot from Crime of M. Lange, one of the few old slides we haven’t cast out.

You could get sharper slides with a gadget called a Duplicon, but it cropped the 4 x 3 image to something like 3 x 2.

When Kristin and I decided to write Film Art: An Introduction, the few introductory textbooks relied almost entirely on production stills, those images shot on the set and circulated to promote the film. The Museum of Modern Art had an archive of production stills, and then as now, publishers turned to such collections for illustrations. As part of the first generation of university-trained film researchers, we doggedly insisted that all our examples would be actual film frames.

Today, digital video has made grabbing frames easy. But before the late 1990s, it was hard. Videotape frames looked terrible, as some books from the 1980s attest. To get decent quality, you needed access to prints. You needed a way to put a reel onto rewinds or, ideally, a flatbed editor like a Steenbeck. And you needed a camera with an enlarging attachment. When you’d copied your frames, you took the exposed film to a lab, where you hoped for a passable result. Black-and-white shots were easier than color, which required blinding lamps of a color temperature matched to Ektachrome or Fujichrome or Agfachrome.

When we could get access to 35mm prints, they were our prime sources for stills. I went to Copenhagen to copy frames from Dreyer films for my first book, and for her dissertation and first book Kristin made frames from 35mm copies of Ivan the Terrible loaned her by Janus Films. Before that, for the first edition of Film Art (1979), we took our color shots from 35mm prints, most of them in the New Yorker Films library. Dan Talbot and José Lopez kindly granted us permission to go to Bonded Storage in Fort Lee. There in the tall aisles of shipping cases we set up a rewind and patiently hunted for the frames we needed.

When we could get access to 35mm prints, they were our prime sources for stills. I went to Copenhagen to copy frames from Dreyer films for my first book, and for her dissertation and first book Kristin made frames from 35mm copies of Ivan the Terrible loaned her by Janus Films. Before that, for the first edition of Film Art (1979), we took our color shots from 35mm prints, most of them in the New Yorker Films library. Dan Talbot and José Lopez kindly granted us permission to go to Bonded Storage in Fort Lee. There in the tall aisles of shipping cases we set up a rewind and patiently hunted for the frames we needed.

But most of the films we wanted to illustrate we could find only on 16. We rented prints and then took stills on a rickety gadget built for us by our friend David Allen. David bolted a pair of rewinds to a plank of plywood. That plank rested on a little table. Into the plank was cut a square slot for an upright light box. The box contained a bulb and was surmounted by a square of translucent plexiglass. The bulb could be put at the bottom of the box, for a photoflood lamp, or near the top with a cooler and dimmer appliance bulb for black-and-white. You positioned the film on the plexiglass and aimed the camera down at the film. A crude zoom lens allowed us to photograph a couple of frames of 16mm and one of 35.

We took the light box on our travels. Archivists certainly looked at us oddly when we brought the thing in, but they usually gave us permission to use it. We’d watch the film on a flatbed and bring the light box over alongside it. Laying the film gently on the surface, we’d poise the camera above it.

Here’s an example of what we got with our plywood setup, from Bill Everson’s print of Bulldog Drummond.

Over the years we improved our system. We bought better cameras, with sharper lenses. We found purpose-built attachments that hold the film strip firmly in place. (Alas, Canon and Nikon seem to have discontinued these rigs.) We used smaller lighting units rather than our curious box. For the last few decades we’ve shot horizontally rather than vertically.

Even in this age of video grabs, we make many frame enlargements on analog stock with 35mm cameras. Even if a film is available on DVD, some of the things we study aren’t preserved in that format. Of course many films aren’t available on video at all, and a great many of those were made to be seen on 16mm.

Format churn catches up with us

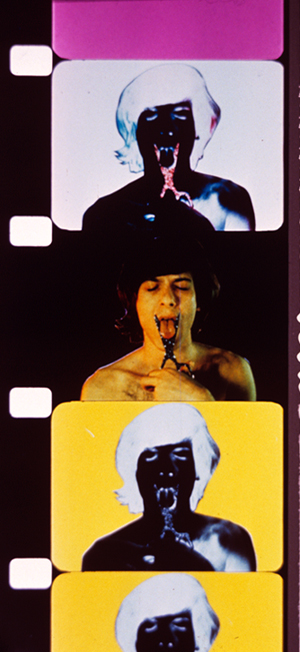

Notebook (Marie Menken, 1962).

Super-16 lives as a production format, but its older brother is nearly dead. True, a few die-hards like Ben Rivers continue to shoot on 16mm, but its future is mostly all used up. James Benning could make 16mm look like 35; when I asked him how he did it, he answered: “I use a light meter.” But even Jim has switched to digital. As for projection, many colleges and art centers have pitched out their 16 equipment.

Since our earliest editions, Film Art included discussions of two remarkable films: Bruce Conner’s A Movie (1958) and Robert Breer’s Fuji (1974). These have not been, and might never be, released on digital disc. Yet by the end of the 2000s, we found that virtually none of the users of our book screened these films for their classes, and curious readers without access to 16mm projection couldn’t easily see them. Reluctantly we cut them from the tenth edition of last year. We replaced A Movie with Koyanisqaatsi to illustrate associational form, and Fuji was replaced by Švankmajer’s Dimensions of Dialogue as an instance of experimental animation. Both titles are available on DVD.

Thanks to the Internet we’ve been able to revive our original discussions of the Conner and Breer films on our site here. We hope that will help the few loyal chevaliers who told me that they did indeed use the films in their courses. But our choice points up a larger problem.

So many documentary and avant-garde films were made and circulated on 16mm that we are at risk of losing a very large slice of film history. We’re lucky to have some Stan Brakhage and Hollis Frampton films on DVD, but what about all the other titles that were distributed by Canyon Cinema, the Film-Makers’ Coop, and other groups? We can get DVDs of Frederick Wiseman documentaries, and some classic ones have been made available on archival collections; but there are many more that depended on 16mm platforms. Even bigger is the set of everyday 16mm movies: amateur films, home movies, and hundreds of miles of newsfilm, from both big TV networks and local affiliates. A great many of the “orphan films” championed by Dan Streible and his colleagues are in this narrow-gauge format.

Recall too that the films of those animators and experimentalists who work frame by frame, such as Breer and Paul Sharits and Paolo Gioli, cannot be studied closely on DVD. How could DVD reveal to us the nifty paintwork of Marie Menken’s Notebook? For that you need a light table, or someone able to photograph it and show you.

Archives will retain 16mm projectors and viewing tables as long as they can. They will preserve prints, perhaps migrating the most sought-after ones to digital formats. Passionate collectors like Tim Romano, who zealously pursues lost films and then donates them to the AFI, will find a way to use our cast-off gear. Our Film Studies department will hang onto the format until the last aperture plate cracks.

16mm was so much a part of our work, our play, our education—in short, our lives—that the separation was inevitably poignant. Pinned to the bulletin board in my basement booth was Ellen Levy’s poem, “Rec Room.” It is, I think, about the fragility and faultiness of the 16mm image, as made palpable in home screenings, and about how that fragility nonetheless carries a pulse of vitality. It begins:

The film assumes the texture of its screen

on the first projection. Audrey Hepburn’s face

creases where the rec room paneling once

took exception to it for the sake of

rephrasing it slightly—a lesson

these late viewings have brought home. Home

screen or revival house . . . .

Thanks to Erik Gunneson and Tim Romano for helping us recycle our 16mm stuff.

Media historian Eric Hoyt, in our Communication Arts Department, studies among other things how the American studios disposed of their film libraries. He talks about his research and his book project, Hollywood Vault, here.

The FOOF contingent was unequivocally a force for good. To sample some of its wonkish hijinks, watch Captain Celluloid vs. the Film Pirates.

New York University’s Cinema Studies Department has created an extensive online collection of William K. Everson materials. For more on Bulldog Drummond, see this entry and this essay on the great William Cameron Menzies. Annette Michelson’s essay on Joseph Cornell, “Rose Hobart and Monsier Phot: Early Films from Utopia Parkway,” was published in Artforum 11 (June 1973), 47-57.

Bonded Storage in Fort Lee is part of the history of American cinema, as this article shows.

Paradoxically, you can study films frame by original frame on some laserdiscs, and on VHS tapes too if you are aware of the 3:2 pulldown. See my entry here. As so often happens, progress along one dimension means regression on another. So I cling to my rotting laserdiscs and demagnetizing old tapes.

James Benning discusses how digital cinema changed his artistic practice at Bombsite. An earlier entry of ours showcases the efforts of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to preserve experimental cinema.

Ellen Levy’s fine “Rec Room” is available in its entirety in The New York Review of Books (9 October 1986).

To watch a video about our Film Studies program, go here.

Germany in autumn, in style

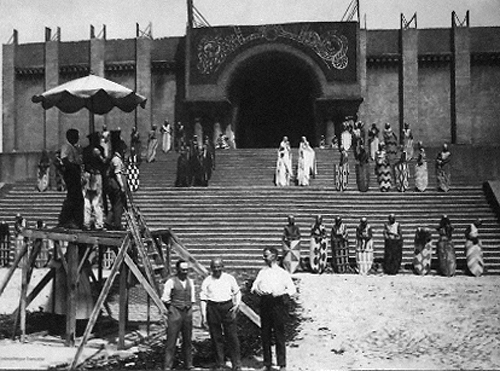

Shooting Frau im Mond (1929) at Neubabelsberg studio, Potsdam.

DB here:

Friends say that Berlin is now the most exciting city in Europe–a little too exciting, others say. I can’t prove either claim, but I can declare that I had a fine time last month during my second visit to Germany this year. Part of the fun was, as usual on many of our trips, finding tangible traces of film history.

Stylin’

Lobby space, Konrad Wolf Film School.

With Michael Wedel, I re-saw Hong Sang-soo film’s Turning Gate in the wonderful Arsenal theatre, part of the Deutsche Kinemathek. The Arsenal is run by Milena Gregor, another old friend (who happens to be Michael’s wife). On another night I also had a delicious dinner with filmmaker Christine Noll Brinckman and other friends. Then there was a pleasant lunch with another filmmaker, Carlos Bustamante (below), in his picturesque neighborhood.

But Berlin literally wasn’t the half of it. I visited Philipps Universität in Marburg, a charming university town. Part of the campus fronts onto the Lahn River, and it makes a charming place to relax.

After my lecture on 1940s Hollywood, my hosts Malte Hagener and Dietmar Kammerer took me out to dinner with their lively colleagues.

Most of my visit was spent in Potsdam, where I’d been invited by the Netzwerk Filmstil. This is a research team composed of several young professors teaching in German-language universities around Europe. Their focus is the exploration of style in audiovisual media–centrally film, but not ignoring television, video games, Internet pieces, and even surveillance and security videos. The two and a half days of the seminar were very stimulating. Michael Wedel, Chris Wahl, Malte, Dietmar, and Kristina Kohler gave illuminating papers on (respectively) digital sound, superimpositions, split screen, freeze-frames, and dance in silent film. The participants offered me good criticisms of my presentation, which explored how E. H. Gombrich’s explanations for stylistic change in visual art might apply (or not) to cinema.

Our seminar sessions were held in the remarkable Konrad Wolf Film School, a towering building crisscrossed by staircases and walkways. I visited it once before some years ago, and once more I admired its airy yet rectilinear architecture.

The stripped-metal look is offset by lots of glass–the light pours in from all directions–and a corner with plenty of plant life. As in our house back home, winged silhouettes on the windows keep bird-brains from flying into the glass.

I also gave a talk on film style during the 1910s at the monumental Filmmuseum Potsdam.

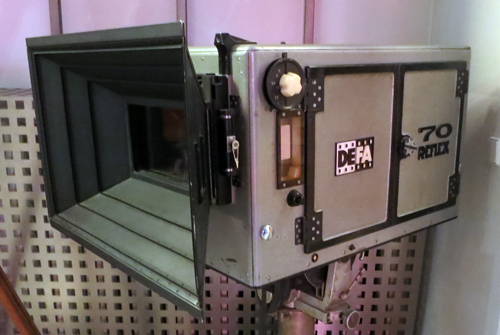

The museum holds a fine screening space and a fascinating collection of historic materials, including a Soviet-era 70mm camera.

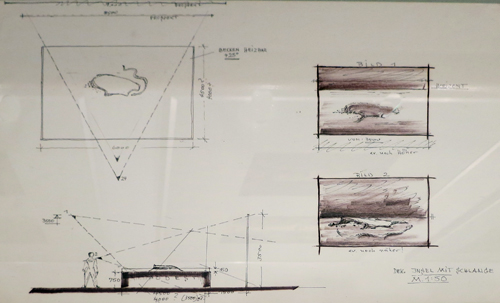

The current exhibition was devoted to the rise of the film studio Babelsberg, not far away. The displays included scripts, set photos, production sketches, photos, and maquettes.

Have you seen this still of the great Cathedral set from the Nibelungen?

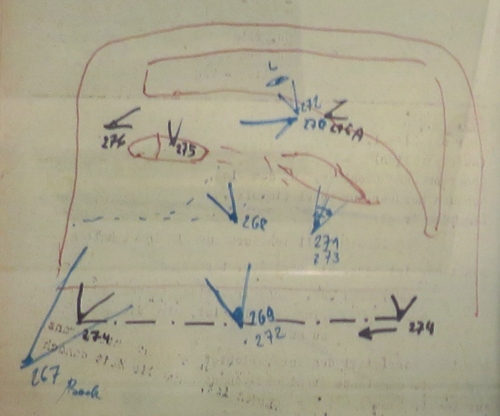

The tradition of fastidious planning created during the silent era persisted into the period of the German Democratic Republic. Each set design was marked up to show camera positions (numbered), lens lengths, and special-effects elements.

The Filmmuseum’s collection was only one reminder of the towering importance of Babelsberg, now celebrating its hundredth anniversary year. Luckily the studio was an easy walk from the Konrad Wolf school. One sunny day our host Michael Wedel took the Style Network on an insider’s tour.

Babelsberg’s birthday

The 1910s and 1920s saw many production facilities spring up in Germany. Films were made in Munich, Frankfurt, and other major cities, and the area around Berlin boasted a number of studios. But the Potsdam facility, initially called Neubabelsberg, became the most well-known, something like Europe’s answer to Hollywood.

Founded by the Deutsche Bioscop company, the studio began production in 1911 and released its first film, Totentanz (The Dance to Death), in 1912. That starred Asta Nielsen, whose popularity had already enriched Bioscop. In this story she’s attracted to a rather louche composer, as we see below. (Yes, that mass of black is mostly her hat.) Later, she slices the guitar strings in a fit of passion and glares out defiantly at us. As if our attention might wander.

Neubabelsberg was home to such classics as The Student of Prague (1913), the Homunculus series (1916-1917), Madame Dubarry (1919), The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), The Golem (1920), and Genuine (1920). Fairly soon Bioscop merged with Erich Pommer’s Decla, and in 1921 the big company Ufa took over the facility and the resident firms. Ufa also had a studio in Tempelhof, a Berlin suburb, but the attention-grabber was Neubabelsberg, which became a sprawling complex of 350,000 square meters–the biggest studio in Europe.

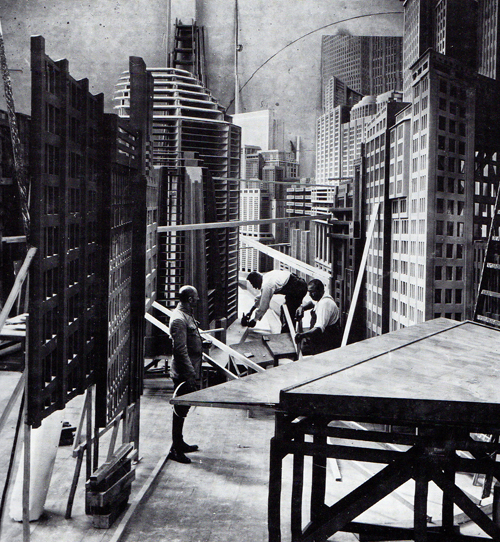

Here Murnau shot Phantom (1922), as well as portions of The Last Laugh (1924). E. A. Dupont filmed some of Variety (1925) here, and Pabst shot all of The Loves of Jeanne Ney (1927) on its stages. Above all, Neubabelsberg helped sustain one of cinema’s great hot hands, the string of films Fritz Lang made in the 1920s: Destiny (1921), the Mabuse duo (19221-22), the Nibelungen saga (1924), Metropolis (1927), Spies (1928), and Woman in the Moon (1929).

The studio remained a powerful force across the next two decades, from The Blue Angel (1930) to the epic color production The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1943).

The partitioning of Germany after World War II put it the studio the eastern sector, and the new state-sponsored film company, DEFA (Deutsche-Film-A. G.), took over the facility in 1953. That made it what Ralf Schenk calls “the exlusive site of feature cinema production in the GDR until 1990.”

After the Wall came down, the Babelsberg studio revived itself as a facility for international productions. It has hosted films by Polanski (The Pianist, The Ghost Writer) and Tarantino (Inglourious Basterds; below, a set on the Babelsberg backlot). The Wachowskis have been loyal supporters, with Speed Racer, V for Vendetta, and most recently Cloud Atlas using the facility.

You can get a sense of the studio today by visiting the website, which presents it as a modern resource for world filmmaking. But its early years matter more to me. To walk these quiet pavements and to imagine following in the steps of Lang, Jannings, Dietrich, and other legends ought to thrill any cinephile. Seeing some streets named for the greats, Tarantino requested a street in his name. It’s apparently a dead end.

A new Babylon

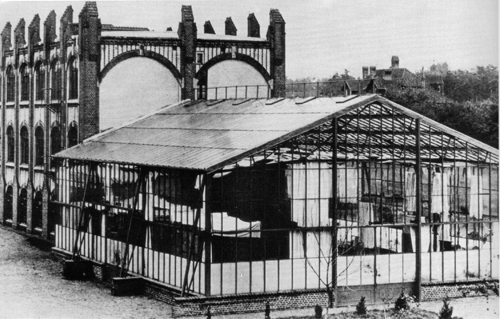

In the cold winter of 1911-1912, Deutsche Bioscop built its first studio, a 45 x 60 foot “glass house”at Babelsberg.

Michael Wedel explains:

Not only was a special cement-less glazing developed for the glass, but even the supporting beams of the infrastructure had to be installed outside of the studio, so as not to spoil the sunlight. . . . In contrast to already existing glasshouse studios that had been “set up” in Berlin and Munich in multi-level apartment blocks and office buildings, the ground-level location of the new Bioscop building at Babelsberg had the advantage of trucks with props and sets being able to be driven through a sliding door directly into the glass studio. . . .

Michael again:

The ground floor of the immediately adjacent factory building accommodated wardrobe and prop rooms, a woodshop, art studio, and a canteen. On the first floor, the production company’s office, as well as the laboratory for developing negatives and positives, were set up. On the floor above was where one found the dry drums for developed film material, the room in which the films were edited, and the rooms where intertitles were prepared. Except for the costume department, which would be built systematically a few years later, Bioscop oversaw a completely integrated film studio, which made it possible to perform most stages of film production on-site.

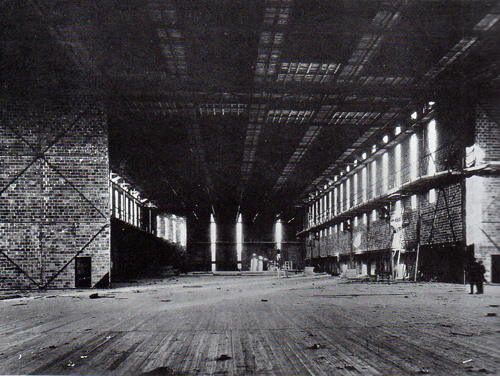

Later in the 1910s Guido Seeber, the cinematographer and all-around creative genius who had planned the Babelsberg plant, began to use supplemental artificial light. But this glass house and its bigger brother, built later, were relied upon throughout the silent era. A closed unit lit entirely by artificial light wasn’t built until 1926. Appropriately huge, it was called the Great Hall and eventually renamed the Marlene Dietrich Stage.

The Frau im Mond production shot atop today’s entry was taken in the Great Hall. Here’s another picture of the interior in the late 1920s. In both shots, those little figures on the far right are men.

On our stroll we caught glimpses of some filming taking place in a parking lot.

Not quite as glamorous as the behind-the-scenes action on–oh, let’s say Metropolis.

We ended our unofficial tour with a quick look at the backlot, which can be redressed to be almost any European city you like.

Movie magic, the Dream Factory: the rationalist side of me rejects these catchphrases as mere mystification. Filmmaking is hard thinking and hard work. But it’s tough to be purely rationalist when you’re facing an illusion machine that has thrilled audiences worldwide for a hundred years. If you see Hansel & Gretel: Witch Hunters, spare a thought for the tradition of Germanic lore that made it possible–and the hard work of the thousands of men and women who built a cinematic metropolis here.

Thanks to all my hosts and colleagues for making my trip to Germany, however short, intense and enjoyable.

Noll Brinckmann’s films and writings are available, at least in part, in this edition. A sample of Carlos Bustamante’s recent work is available online here.

For a fairly detailed timeline of Babelsberg’s history, see this page of the Filmmuseum site. When spring comes, you can take a studio tour (German language only) or visit the nearby theme park.

My quotations come from Michael Wedel, ChrisWahl, and Ralf Schenk, 100 Years Studio Babelsberg: The Art of Filmmaking (teNeues, 2012). This is that rare coffee-table book whose historical texts (footnotes included) are as valuable as the luxurious photos. The book, in an English/German edition, is available from the Filmmuseum and from Amazon.de.

This post gathers information from Hans-Michael Bock and Michael Töteberg’s encyclopedic Das Ufa-Buch (Zweitausendeins, 1992). Also helpful was Klaus Kreimeier’s The Ufa Story: A History of Germany’s Greatest Film Company, 1918-1945 (Hill and Wang, 1996).

We hadn’t planned it this way, but Kristin’s previous entry discusses several recent DVD releases of German classics. I wrote a little bit about Totentanz (1912) here.

My lecture at Potsdam, “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies,” was a new version of a talk I’ve been giving for the last couple years to whatever audiences of innocents that fate has flung my way. Alert filmmaker Erik Gunneson, who prepared our video essay on constructive editing, is currently turning this talk into a video lecture. We hope to put it up on this site early in 2013.

The stylish Film Style Mafia, Neubabelsberg, November 2012.

10 Dec 2012: Thanks to Antti Alanen for two spelling corrections!

Digital projection, there and here

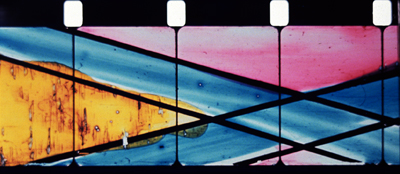

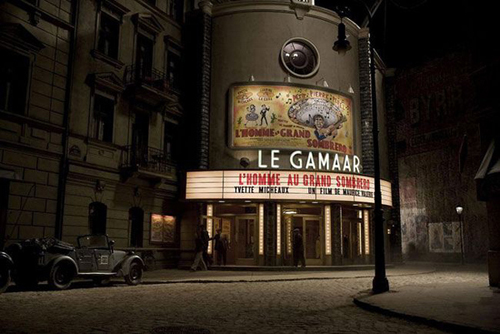

Galeries Cinéma banner, Brussels, 2012.

DB here:

The Cinéma Arenberg, in the splendid Galerie de la Reine, has long been a mainstay of Brussels film culture. Since 1939, the lovely Art Deco theatre was what we Americans call an art-house. Over the years Kristin and I visited the city, the Arenberg’s autumn and spring schedules featured recent releases, but every summer the programmers plunged into plucky repertory programs. While the multiplexes ran Hollywood blockbusters, the Arenberg provided 90 or so classics and little-known releases under the rubric of Écran Total. It was here, for example, that I saw von Trier’s The Kingdom and resaw Vanishing Point. Four years ago I left a little note about the three titles I watched during my last day in town: India Song, Serpico, and Darjeeling Limited. That trio gives you a sense of how varied and interesting the programming was.

The Arenberg closed down at the end of 2011, but the cinema has reopened under new management as Galeries Cinéma. It didn’t sponsor an Écran Total season this year. Instead it offered brand-new releases on its three screens, along with some children’s programs.

Most notable for me this time was Leos Carax’s Holy Motors. Whatever you’ve heard about this film is probably accurate. I found it an exhilarating, frustrating, and continuously provocative descent into Surrealist role-playing. It’s a tour of cinema genres and an anthology of bits of other movies, from Marey to Franju, and not forgetting Carax’s own. Especially evocative were the poetic fusions, such as the way that the body stocking Oscar dons for digital motion-capture evokes both ninja outfits and the leotards of Feuillade’s Vampires. Carax films Oscar’s SPFX exercise in a way that connects Muybridge to video games and recalls the exuberantly spasmodic scene in Mauvais Sang in which Denis Lavant races madly down the street to the accompaniment of David Bowie’s “Modern Love.”

Whether you find Holy Motors infuriating or beguiling, you won’t forget it.

Exquisitely shot on digital capture, Carax’s film was given crisp, bright digital projection at the Galeries. And speaking of digital projection. . . .

The new issue of Film History, devoted to digital technology’s impact on filmmaking and film culture, includes Lisa Dombrowski’s article “Not If, But When and How: Digital Comes to the American Art House.” It’s a very fine survey of all the issues facing the art-film community at this moment. Lisa reviews the major technological and financing conditions before going into depth on a case study of three art theatres in Miami. The author of a very good book on Samuel Fuller, Lisa knows how to tie together industrial and aesthetic issues skilfully.

Another young scholar, this one at the Free University of Brussels, has concentrated on the digital transition in Europe. Since 2005 Sophie De Vinck has been studying how the conversion of theatres fits into European film policy. The result was her 2011 thesis, “Revolutionary Road? Looking back at the position of the European film sector and the results of European-level film support in view of their digital future.” The thesis, running to a whopping 769 pages, is an immense resource, and not just for people interested in digital cinema. Sophie surveys the history of national and international support of the Western European film industry, from production through exhibition, and she provides both a broad context and very specific analysis.

Part of her argument is that the “diversity” aimed at by subsidized filmmaking hasn’t been matched by diversity in audiences. But digitization offers a new chance to show films outside the dominant forms of commercial cinema and perhaps attracted new sectors of the public. “Every innovation usually brings with it possibilities for new or smaller sector players to strengthen their competitive position.” Her examination of how digital conversion affects small and art-house venues provides a complement to Lisa’s research.

I wish I’d known about Sophie’s thesis when I was writing the blogs that became Pandora’s Digital Box, but at least I can signal her work now. Best news of all: Sophie has generously made “Revolutionary Road?” available under a Creative Commons license here as a pdf. Full of valuable statistics and well-honed observations, her work helps us understand how the contemporary European film industry has survived and sometimes flourished over the last fifty years.

Cinema Arenberg, Brussels, 2008. The original design of the curved doorway and neon sign was restored in 2005-2006.

The indispensable site Cinema Treasures has a brief entry on the history of the Cinéma Arenberg/ Galeries. More extensive information can be found in Isabel Biver’s luxurious survey, Cinémas de Bruxelles: Portraits et destins, which I wrote about in an earlier entry.

P.S. 1 August 2012: I just learned from Gabrielle Claes that Giovanna Fossati’s book on digital restoration in film archives, From Grain to Pixel, is now available for free in pdf form here. It’s well worth reading.

German detour

DB here:

A bad back kept me from Cinema Ritrovato, as Kristin explained in her Bologna blog entry. So I spent that week at home fiddling with the Film Art entry, and starting another one that I posted most recently, on the swirl of controversy around the Orpheum Theatre here in Madison.

Thanks to some exercise, chiropractic, and a nice dose of painkilling medication, I was able to embark on the second phase of the trip: My annual visit to Brussels for its Cinédecouvertes festival and for some research in the Royal Film Archive. But this visit was different from earlier ones because I took time off to visit colleagues in Germany.

My first stop was Mainz, a lovely cathedral town that’s also the capital of its state. My hosts were Andreas Rauscher and Oksana Bulgakowa of the University’s Department of Film, Media, and Empirical Cultural Studies.

Andreas has with two colleagues written a book on The Simpsons (Subversion in Prime Time). Once very controversial (because of its many pictures from the series), it’s now headed into its third edition. Andreas also works extensively on narrative theory in film and media. Oksana, Chair of the Department, is an old friend of ours who has done a great deal of work in classic Soviet cinema. She has written a comprehensive biography of Eisenstein and has launched an ambitious program studying gesture in cinema and culture. It was a pleasure as well to re-meet Norbert Grob, a key player in a recent collection devoted to “minimal cinema” (you know I like the cover), and to meet Armin Jäger, who has written us with corrections and suggestions for Film History: An Introduction.

My talk was the last in a series on the future of film studies. I usually hesitate to participate in exercises like these, which tend toward the gaseous. But when Andreas assured me he wanted me to discuss how modern digital culture, particularly the Web, affected my research, I felt more able to say something. So I did, drawing together what I’ve learned through and about the online world. The results were recorded on video and will be posted online.

Before the talk I enjoyed ambling around Mainz with Andreas and his colleagues Bernd Zywietz (left, above) and Renate Kochenrath. Renate made me feel old: She had attended my 2003 lecture at the University as an undergraduate. But she compensated by (a) giving me a spare umbrella; and (b) showing me the devil’s dung in a corner of the beautiful cathedral.

I even got to meet a fan, Alexander Gajic, who had reviewed my Pandora e-book. Like me, he stalks autographs, but how do you autograph an e-book? He found a digital-to-analog solution.

The night before, I had walked a bit around town with Andreas, Oksana, and Dietmar Hochmuth. I had the sense of being in a Murnau film: winding streets overseen by magnificent towers half-medieval and vaguely futuristic.

After my 1 ½ days in Mainz, I had only a day in Frankfurt. My host was Vinzenz Hediger, who explores the intersection of film history and media history. (He knows, in particular, a lot about the history of the Hollywood industry.) Here he is with two sterling Steenbecks his department retains.

The film department at Goethe University is housed in a stunning complex, now known as Poelzig-Bau or the IG Farben Hochhaus.

It has quite a history. The great architect and set designer Hans Poelzig (the Grosses Schauspielhaus in Berlin, sets for The Golem) created it for the IG Farben chemical trust at the end of the 1920s. The largest office building in Europe, it became a center of Nazi technology, including the development of the Zyklon-B gas used in concentration camps. The complex housed the US armed forces HQ from 1945 to 1995. According to Colin Powell’s autobiography, he first met Dick Cheney in these halls.

At Frankfurt, I gave two talks. The first was a variant of a party piece I’ve worked up, on narrative innovation in Hollywood during the 1940s. I was happy to see so many students turn up on a very pleasant day. I was also happy to see that Heide Schlüpmann, now retired, had arranged for a display of film, actual film, to be a permanent part of the lecture room.

My other Frankfurt talk was at the Deutsches Filminstitut Filmmuseum, recently redone as a dazzling modern facility. Walk in, and you’re in a dark box, in which the displays glow enticingly, like pods in a space station.

The first floor is devoted to pre-cinema, with many hands-on toys and gadgets. It culminates in a Lumiere display. The second floor roams across film history, with an emphasis on storytelling. Eras mingle: Next to a velvet dress from Visconti’s Leopard you might see a Giger Alien design. And it’s big.

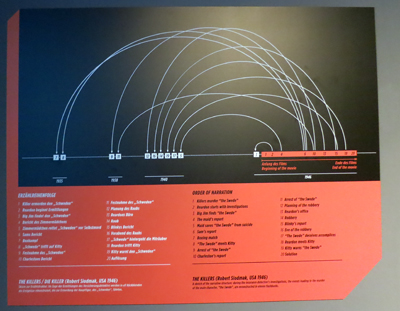

There are many interactive displays, letting you recut a sequence or remix a soundtrack. The third floor is for touring exhibitions, this time one devoted to Film Noir. Close to my heart was a diagram of the time shifts in the plot of The Killers.

Like New York’s Museum of the Moving Image (which we visited here), the Frankfurt museum has acknowledged the need to educate a new generation of movie lovers. What once were temples drawing aging cinephiles to worship are now filmic Exploratoriums, invitations to play with the curious thing we call movies.

More on Germany–well, the obscure German silent movies I’ve been watching in Brussels–in an upcoming post. For now, back to work in Belgium. And to the tasty snack treats portrayed below, although in somewhat smaller portions.

Thanks to Andreas Rauscher, Vinzenz Hediger, and Michael Kinzer for background information on their institutions.

Kristin has just published her own account of our experiences going digital, here.

Summer art displays in Parc de Bruxelles/ Warandepark, Brussels.

P.S. 22 July: Renate Kochenrath and her colleagues have created a striking site documenting art cinemas in the Rhineland-Palatinate region. The photos are quite beautiful.