Archive for the 'Film scholarship' Category

Cognitive scientists 1, screenplay gurus 0

Kristin here:

The annual meeting of the Society for the Cognitive Study of the Moving Image is currently taking place at Elte University in Budapest. It runs from June 8 to 11. It must have started off very well. Barbara Flueckiger posted this comment on the opening keynote address on Facebook: “Just attended an absolutely fascinating and inspiring talk by Talma Hendler, a professor of psychiatry and neuroscience: ‘Brain Shows Where the Drama Is. A Call for an Empirical Neurocinematic Agenda.'”

Last week David posted a new web essay on “common-sense film theory” as a way of participating from afar in the work going on in Budapest. Now it’s my turn to post a SCSMI-related item.

The mirage of the second-act desert

Twelve years ago I published Storytelling in the New Hollywood (Harvard University Press). It included a claim that most classical Hollywood feature films have four acts, lasting roughly 25-30 minutes each, adding up to a film of from 100 minutes to two hours. This claim ran counter to the old notion, popularized by Syd (Screenplay) Field, that Hollywood movies (and, according to Field, all feature narrative films) have three acts of 30, 60, and 30 minutes respectively.

My book analyses ten films in detail, dividing them into their four parts: Setup, Complicating Action, Development, and Climax (usually including an epilogue). I also have an appendix listing ninety additional films that I timed by large-scale part, ten for each decade from the 1910s to the 1990s. My conclusion was that most of these films stuck to the four-part structure with each part within five minutes either way of lasting a half-hour. Some of the exceptions were actual three-act films (e.g., Adam’s Rib) and others were longer films. Amadeus, one of my ten main examples, is 160 minutes long and has five large-scale parts. (“Large-scale part” was the rather cumbersome term I employed in the book, trying to avoid the misleading word “act.” I have to admit though, that there’s little chance of people discontinuing “act” and switching to “large-scale part.”)

I also defined the “turning point” that Field says divides acts more concretely than he does, specifying that it usually results from moments when the main characters formulate or modify the goals that drive the narrative forward. (I expand upon the relationship of goal shifts and turning points in a previous entry.)

Unlike Field and other screenwriting “gurus,” I allow for exceptions to my four-part schema. The Pink Panther doesn’t have a turning point until over 52 minutes in; the lengthy early part of the film consists of a bedroom-farce situation of male sexual frustration that makes absolutely no progress toward the putative subject of the film, the theft of a valuable jewel. As far as I can tell, It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World has no turning points at all. I remember thinking it was quite funny when I saw it as a child.

Some screenwriters have read the book, and some who teach screenwriting courses assign it as a textbook. At least it’s still in print, which is something to be grateful for at my age.

Since the book was published, it certainly hasn’t knocked out the conventional view that films have three acts. Not infrequently I read a review in Variety or another specialist journal that refers to the last quarter of the film as the “third act.” The idea that films fall into chunks lasting 30 minutes, 60 minutes, and 30 minutes, no matter how counterintuitive or inaccurate, is too entrenched to be dislodged, apparently.

Still, I have the consolation that I’m apparently right. Other people have tried out my claim and found it to work. Creative Screenwriting gave a very kind review to my book (in its March/April 2002 edition, not online). D. K. Holm, the reviewer, was inspired to test out my system on the next three films he saw in theaters. He declared that it worked as predicted for The Shipping News, In the Bedroom, and even Ali, a five-act film. (My claim is that longer films don’t stretch their four acts. They add more, roughly 30 minutes long, for every half hour beyond the standard two-hour feature. Roughly half an hour apparently seems to create a pleasing balance as far as Hollywood practitioners are concerned—whether they’re aware of it or not.)

Real scientists at work

Now James E. Cutting, whom we enjoyed meeting and talking with at last year’s SCSMI conference (David devoted part of his report on the conference to James’s work), has collaborated with two of his graduate students, Kaitlin L. Brunick and Jordan E. DeLong, on a quantitative study related to Storytelling. They set out to test the whether the four large-scale parts of a classical film are reflected on the stylistic level. Specifically, do shot lengths and the use of non-cut shot transitions (fades, dissolves, and the like) vary in a patterned way across or among the parts?

It’s exciting to see cognitive scientists study claims that I’ve made on the basis of close film analysis. David has had his claims about staging and attention in There Will Be Blood confirmed by Tim Smith’s eye-tracking research on the same sequence. Now the results of Cutting, Brunick, and DeLong’s work relating to the four-part structure have been published in Projections (Vol. 5, issue 1, Summer 2011), subscriptions of which are included in SCSMI membership. Luckily I didn’t know this article was on the way, or I might have been in some suspense to find out whether my model worked. (This and other articles on film are also available online, linked from this page that lists the work on film published by James and his colleagues.)

As the authors’ starting point, they accepted my four-part structure. Or as they put it:

We find Thompson’s argument persuasive and her data remarkably clean. Nonetheless, the division into acts is built on a detailed analysis of the narrative, and we work from the physical properties of film. Many observers might agree on act divisions, but these divisions would not necessarily be reflected in any physical measure of a film’s shots and transitions. Thus, without prejudice as to what we might find, we sought data in shot lengths and in shot transitions that might corroborate Thompson’s analysis. (p. 4)

The team used 150 films they had previously studied in their work on editing patterns and their possible correlations to human attention. Of these, some were eliminated because they were too long, so that the statistical work could concentrate on films with four parts. I cannot claim to be able to follow all the statistical manipulations the data from these films were put through—though I can tell from the information in the footnotes that the degree of probability for some of their results indicated an amazingly small chance of error.

The figure at the top is a “scatter plot” of shot lengths for 143 Hollywood films from the period 1935 to 2005. These figures have been statistically adjusted in ways that allow the films to be compared despite their differing lengths. (I have no idea how this sort of thing is done. You’ll have to see the explanation in the article.)

One striking revelation of this chart is that the lengthiest shots in the films occur at the beginning, end, and at the one-quarter, two-quarter, and three-quarter points. Moreover, the “scallop” pattern of rising and falling average shot lengths shows a “tendency toward intensification of films near the middles of acts, where shot lengths become slightly shorter.” The ASLs were found to be as much as 1.1 seconds shorter than in the early and later portions of the acts.

Luckily I was right about the four parts. But beyond that the authors came up with results supporting my claims about the functions of the plot’s third part, the Development. Here’s how.

As part of the study, the authors tackled the question of where non-cut shot changes fall in relation to the quarters of films. Non-cut changes are fades, dissolves, and the like. It turns out, not surprisingly, that quite a few of them come early on, since the exposition may move among time and places setting up the basic premises of the narrative. But the rest tend to come in the third quarter, the Development. That makes sense to me. By my definition, the Development is essentially the stretch of action where most of the major premises, goals, and obstacles have been established. Before the climax can begin, the protagonist usually struggles against obstacles, usually provided by the antagonist. Often relatively little happens in the Development to forward the action, at least in comparison with the other three parts. At the Development’s end, some vital last premise is introduced that allows the action to move into the climax portion, where the plot moves forward relatively quickly and no more major premises are introduced.

The Development might contain extra fades and dissolves for two reasons. First, a surprising number of films have a montage sequence shortly after the middle turning point. The one depicting Michael Dorsey’s rise to fame as Dorothy Michaels in Tootsie is one such. Second, since the Development often is the section where time passes until the point where the climax can begin, one would expect fades or dissolves to cover temporal gaps. I’d have to go back and watch a bunch of films to confirm those hunches, but they seem logical.

My main purpose in writing Storytelling in the New Hollywood was to show that the principles of classical narrative construction formulated in the 1910s and used throughout the studio era are still operative today. Despite film reviewers’ complaints that action and special effects have come to substitute for story appeal in modern mainstream films, the kinds of films they find so shapeless do usually stick to the same four-part structure, contain goals and conflict and the rest of the principles that have been in effect for decades. Cutting, Brunick, and DeLong’s work bolsters this claim about classical narrative’s stability over time. They find that “there are no obvious differences in these patterns for films of different eras.” (p. 8.)

This issue of Projections has other articles applying a cognitive-science approach, and with luck future issues may contain some of the papers we have been unable to attend at this year’s conference.

James, Kaitlin, and Bradford have set up an online overview of their research in progress, “Shot Structure and Visual Activity: The Evolution of Hollywood Film.” The graphics and type are quite small, but right-click on the page and click “Marquee Zoom,” which brings up the little magnifying glass that allows you to enlarge it multiple times.

For online applications of the idea of four-part structure, see David’s essay on Mission: Impossible III and his blog entry on Source Code.

Jordan DeLong, Kaitlin Brunick, and James Cutting at annual convention of SCSMI, Roanoke 2011.

Another quick one

Goodbye South, Goodbye: Kao confronts Flathead while the women tune out.

DB here:

The newest issue of Film Comment includes an essay I wrote on the relations between academic film studies and cinephile criticism. It’s online at the Film Comment site.

Two things: The header (“Never the twain shall meet”) risks misleading you. The essay argues that the twain can and should meet. Secondly, the essay refers to stages of a long take in Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Goodbye South, Goodbye, but neither the Web version nor the print version uses the images I suggested as illustrations. So here, in frames from a 35mm print, I present two phases of this gloriously dense scene. I discuss Hou’s staging principles in Chapter 5 of Figures Traced in Light, with comments on this passage on pp. 234-236.

As a followup, and weirder: The Way Hollywood Tells It is now available as an audio book. How it handles the pictures I don’t know. But you can listen to a sample here.

If the scene has a climax, this is probably it. As the punching bag swings, Flathead wriggles out the window.

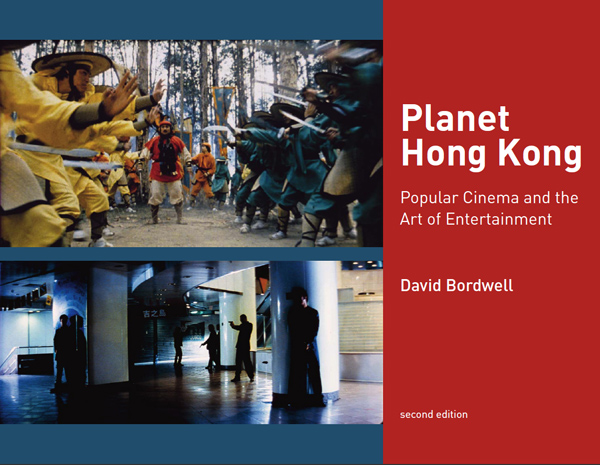

PLANET HONG KONG: One more visit

Hong Kong, Central, April 2008.

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run daily entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have time or inclination to raise in the text. The first one, listing around 25 HK classics, is here. The second, a quick overview of the decline of the industry, is here. The third discusses principles of HK action cinema here. A fourth, a portfolio of photos of Hong Kong stars, is here. That was followed by a tribute to western Hong Kong fans and then by a photo gallery of directors. Today’s installment is the last. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D, which will appear later this week.

Since the 1980s, the film festival circuit has become the only distribution system to rival Hollywood’s global reach. A big-name festival publicizes a film, some high-end critics at the festival write reviews, then once the film opens in a region or country, critics at large review it. As smaller festivals pick up films from the bigger ones, until eventually films make their way to small cities around the world. This process is parallel to the one that the studios orchestrate, though they have more centralized control. Video distribution, the circulation of DVD screeners, and Internet reviewing complicate this picture, but I don’t think they change the essential role of the festival network.

Just as film scholars have started to pay attention to fandom (see this post), they’ve started to ask research questions about festivals. As very few films from overseas find their way to U. S. screens, scholars keen on current cinema have realized that they need to visit festivals. It’s like scholars of painting traveling to exhibitions and gallery shows, or opera aficionados attending premieres at Bayreuth and La Scala. And film scholars of certain genres or periods have realized that they can do on-the-fly research by visiting historically oriented festivals like Pordenone and Bologna.

These days I see more of my colleagues at various festivals. In particular there’s the peripatetic Bérénice Reynaud, an early example of the multitasker (critic, programmer, professor, fan). On the same circuit I meet Virginia Wright Wexman, Peter Rist, Mike Walsh, Jim Udden, Gary Bettinson, and many other profs. So I’m starting to think that festivals are giving academic film studies a fresh charge of energy. Reciprocally, the events at Pordenone and Bologna, which began as cinephile events, have invited academic researchers to help program them and write for their publications. In sum, festivals are now a vigorous workspace for not just screenings and critical write-ups but discussions about ideas that would normally haunt the groves (or is it grooves?) of academe.

Saturation booking

Athena Tsui and Li Cheuk-to. Hong Kong, 2000.

I had dropped in at screenings at the New York and London film festivals in the 1970s and 1980s, and I had steadily attended the summer Cinédécouvertes series in Brussels. But I had never “done” a festival intensively until I went to Hong Kong in the spring of 1995. There I saw films that still stay with me: Through the Olive Trees, Postman, In the Heat of the Sun, A Borrowed Life, Smoking/ No Smoking, Quiet Days of the Firemen, Taebek Mountains, 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance, Whispering Pages, and Clean, Shaven. (My one big miss was Sátántangó; I had to wait years to catch up with that.) Who says the 1990s were a meager decade? Can any festival today come up with a menu like this?

I had gone, as I explain in the Preface to Planet Hong Kong, mainly to check on local cinema. The “Hong Kong Panorama” surveying 1994 releases yielded a bumper crop, including some titles I’d seen only on laserdisc (Chungking Express, Ashes of Time) and others that were revelations. Above all, there was a retrospective—an entire festival in itself, really—dedicated to early Chinese and Hong Kong cinema. They swept over me in a heaving wave: Love and Duty (1932), The Eight Hundred Heroes (1938), Boundless Future (1941), and many others, along with postwar Hong Kong classics like Where Is My Darling? (1947), Song of a Songstress (1948), The Kid (1950), with Bruce Lee, and on and on. The series was capped by stunning restored Technicolor prints of The Orphan (1960), also with Bruce, and General Kwan Seduced by Due Sim under Moonlight (1956). Some of these had circulated on poor VHS copies, but most were, and still are, unknown in the West.

I had picked the perfect year to come to the festival. Looking back at the notes I scribbled in the dark, I realize that over three weeks I got a crash course in Chinese film history. In any given day I was given more to think about, and certainly more to feel about, than I got from almost any academic conference.

For those of us interested in non-Hollywood cinema, festival programmers and critics are central gatekeepers. They scout the ridge and scan the horizon, and around the campfire they teach us film lore. They’ve built up fingertip knowledge about movies, moviemakers, distribution patterns, sales agents, theatre circuits—in sum, the workings of world film culture. The best of these gatekeepers are intellectuals, ready to search out something stimulating in even the most marginal film. They have honed their senses to detect qualities that could provoke an audience or yield a lively Q & A or a piquant catalogue entry or a solid review. Out of pure selfishness, I wish I could download the neural storage files of Alissa Simon, Richard Peña, Tony Rayns, Cameron Bailey, and their peers. Alas, there is no app for that.

In Hong Kong I met Li Cheuk-to, Jacob Wong, Freddie Wong, and many other programmers, along with Athena Tsui and Shu Kei. What made my experience that spring of 1995 so thrilling were their months of patient planning and sleepless nights behind the scenes—finding the prints, arranging for them, writing catalogue copy and, not least, assembling a massive reference work like Early Images of Hong Kong & China, one of the precious books the festival managed to turn out every year to document the local cinema.

Many programmers are also critics, and such was the case in Hong Kong. When I arrived, Cheuk-to and his colleagues had just formed the Hong Kong Film Critics Society, and I was invited to their first awards ceremony. They were mostly young, and after the awards were handed out I was invited out to dinner with several of them. It was then I realized that here was a local film culture in which criticism mattered. Hong Kong was small enough for critics to band together to debate their cinema. Soon another critics’ group was founded, and the debates spread. I started to understand that if one were to study a film culture, one would have to grasp the dynamics of taste among schools of critics and between critics and their audiences. I made an effort to describe this dynamic in the second chapter of Planet Hong Kong.

It’s not just that that book had its origins in that first visit. And it’s not just that the newest edition is the result of my attending the festival for the last fifteen years. More important, my ideas about film and about the world changed when I met critics, programmers, and other academics in Hong Kong. Immersion in one of the world’s most fascinating cities had something to do with it too.

Favorites, for now

As Tears Go By (1988).

In my first entry in this hurriedly posted series, I listed around 25 Hong Kong films that most aficionados consider of major importance—historical, artistic, cultural, or all three. In the days since, I’ve mentioned several other films that you can check into. Here, as an envoi to this yakathon, are a few more movies that I’ve repeatedly enjoyed, and that I’ve sometimes talked about in PHK 2. They’re grouped in very loose categories.

Lesser-known items from major directors. Once a Thief is a good example. Sandwiched between Woo’s official classics is this good-natured, somewhat silly action comedy about art thieves, romance, and parenthood. Lifeline is one of my favorite Johnnie To Kei-fung films—not as formally audacious as his later masterpieces, but containing one of cinema’s great action sequences involving a fire that seems as unstoppable as a waterfall, with the bonus of a throat-catching epilogue. Ann Hui On-wah’s Summer Snow, about a busy career woman who must treat her Alzheimer’s-affected father, glows with the intimate realism and understated sentiment that inform her more recent The Way We Are.

Everybody knows some works by Wong Kar-wai, but I think his later accomplishments have overshadowed his debut, As Tears Go By, a prototype of the arty gangster movie. Drenched in romanticism, it has one of the great music montages in Hong Kong film and a finale that you feel lifting from genre formula to pictorial poetry. With Johnnie To as well, even offbeat items like Throw Down are getting well-known, but I’d like to make a pitch for the New Year’s mahjong comedy Fat Choi Spirit. It has some of the 1980s nuttiness; the laughs start at the DVD menu.

Tsui Hark has produced so many films that have been fan favorites–Peking Opera Blues, Once Upon a Time in China, and Swordsman III: The East Is Red–that you can’t expect anything worthy to be overlooked. And yet not enough people have seen the bouncy Shanghai Blues, with moments of musical rapture, and The Chinese Feast, with all his faults and virtues bundled into a celebration of cooking and eating. There’s also The Blade, a convulsive revenge saga that seems to me one of the best movies made anywhere in the 1990s. After it’s over, you’re not sure what hit you.

Drama, comedy, dramedy. Any reader of PHK knows my fondness for the gender-bending romance Peter Chan Ho-sun’s He’s a Woman, She’s a Man, a lovely integration of musical, coming-of-age story, and satire of sex roles. But my favorite Michael Hui film, Chicken and Duck Talk didn’t feature in the first edition because I couldn’t get my hands on a print to illustrate it. Tracing the rivalry between a scruffy duck restaurant and a Japanese knockoff of Colonel Sanders, it yields many hilarious sequences, perhaps most notably Hui’s efforts to conceal a plague of rats from health inspectors.

Chow Yun-fat made his western reputation in crime movies, but his local fans also love his comedies and dramas. Try the screwball Diary of a Big Man (right) in which Chow juggles two wives and enacts a music video; the wistful romantic drama An Autumn Tale; and of course the male melodrama All About Ah Long. Churning out six to nine movies a year, the man was a real movie star. In April 1995, I was waiting in line to see Peace Hotel and felt the crowd’s nervous anticipation. Three whole months had passed since they’d seen their friend in a new movie.

Chow Yun-fat made his western reputation in crime movies, but his local fans also love his comedies and dramas. Try the screwball Diary of a Big Man (right) in which Chow juggles two wives and enacts a music video; the wistful romantic drama An Autumn Tale; and of course the male melodrama All About Ah Long. Churning out six to nine movies a year, the man was a real movie star. In April 1995, I was waiting in line to see Peace Hotel and felt the crowd’s nervous anticipation. Three whole months had passed since they’d seen their friend in a new movie.

My associates sigh when I mention Wong Jing. What can I say? I find some of his films funny. Try Boys Are Easy, Tricky Master, and, probably my favorite, Whatever You Want. If you don’t like them, write my suggestion off as David in his Dotage. Speaking of silliness, I’m not over-fond of Stephen Chow, but All for the Winner, Flirting Scholar, From Beijing with Love, and A Chinese Odyssey are ingratiating enough. Square that I am, I like Shaolin Soccer too.

I’d add the medical melodrama C’est la Vie, Mon Cherie, the unpredictable cop stakeout movie Bullets over Summer, and the poignant Juliet in Love, about a triad’s attraction to a woman recovering from a mastectomy. Sylvia Chang Ai-chia’s quiet romantic dramas Tempting Heart and 20 30 40 are also rewarding. Patrick Tam Kar-ming’s films are still unjustly neglected, so anything might be considered obscure, but I was delighted when a passable DVD of My Heart Is that Eternal Rose was released. Here Tam lyricized the gangster movie; Wong Kar-wai took the next step.

For grotesque comedy, try You Shoot I Shoot, about a contract killer who adds value by having an aspiring director film the hits (complete with slo-mo) for the delectation of the client. Unclassifiable is The Inspector Wears Skirts II, a cop-training story that pits women recruits against dimwitted men. It includes a dance sequence displaying minimal skill and maximal cheerfulness.

Fight club: Of Chang Cheh’s vast output of martial-arts movies, I have a special affection for New One-Armed Swordsman, a spectacularly mounted action picture, and Crippled Avengers, in which “disabled” really does mean “differently abled.” For Lau Kar-leung, I especially admire Legendary Weapons of China, one of the strangest of his forays into the arcana of martial arts lore and Chinese history; Shaolin Challenges Ninja (aka Heroes of the East), a sort of Taming of the Shrew, but with throwing stars; and the harrowing Eight-Diagram Pole Fighter, something of a valedictory for the Shaolin tradition at Shaw Brothers. Both these directors made so many worthwhile films that you can spend a lot of agreeable time exploring their output.

Though not everyone agrees, I think that Corey Yuen Kwai is a fine director of action pictures, from the tonally discordant Ninja in the Dragon’s Den through the warrior-women saga Yes, Madam!, the vigilante-justice Righting Wrongs (incredible, literally, final airborne sequence), and Saviour of the Soul, a futuristic fantasy with one shot looking forward to Chungking Express (right). Yuen’s Fong Sai-yuk films and Bodyguard from Beijing contain classic sequences—fighting on the heads of a crowd, on top of a precarious pile of furniture, in a hypermodern kitchen. Co-signing the first Transporter film, he turned in something resembling the classic Hong Kong style.

Though not everyone agrees, I think that Corey Yuen Kwai is a fine director of action pictures, from the tonally discordant Ninja in the Dragon’s Den through the warrior-women saga Yes, Madam!, the vigilante-justice Righting Wrongs (incredible, literally, final airborne sequence), and Saviour of the Soul, a futuristic fantasy with one shot looking forward to Chungking Express (right). Yuen’s Fong Sai-yuk films and Bodyguard from Beijing contain classic sequences—fighting on the heads of a crowd, on top of a precarious pile of furniture, in a hypermodern kitchen. Co-signing the first Transporter film, he turned in something resembling the classic Hong Kong style.

In the crime vein consider Kirk Wong’s hard-driving and pitiless Rock ‘n’ Roll Cop and Danny Lee’s Law with Two Phases (not a typo). Ringo Lam’s films are notably tougher and more tactile than those of his contemporaries; see his deromanticized classic City on Fire, the effort to out-Woo Woo that is Full Contact, and the lesser-known Full Alert. Eddie Fong Ling-Ching isn’t known for policiers, but Private Eye Blues was one of the films I enjoyed in the 1995 Panorama. His historical drama Kawashima Yoshiko is even more remarkable.

Connoisseurs know The Outlaw Brothers; one glimpse of the climax, in which a gunfight is interrupted by a hailstorm of poultry, usually convinces any viewer to take a closer look. I must add the below-the-radar ensembler Task Force, by John Woo protégé Patrick Leung Pak-kin. Gratifyingly untidy in skipping among the personal lives of a cop squad, it eventually focuses on the need to settle conflicts without violence—after, of course, supplying some snappy fight scenes of its own.

Post-handover take-outs. Most of the films I’ve mentioned are from the 1970s through the 1990s. But many worthy films have emerged in the 2000s. If they don’t always carry the effervescence of the earlier ones, many are solidly crafted. Some are discussed in Planet Hong Kong 2.0 and many more have received commentary on other websites (e.g., LoveHKFilm), so I’ll just mention a few that seem to me of more than transitory appeal.

Patrick Tam’s After This Our Exile is an unsentimental look at how an aggressive, heedless father must come to terms with his little boy. Needing You is a better-than-average office comedy, while Hooked on You is poignant in the gruff Hong Kong way, with a touching finale about the changes since 1997. Benny Chan Muk-sing’s action pictures usually deliver sturdy value in the old style. Try Connected, a remake of Cellular; New Police Story, with Jackie Chan as a cop coming to terms with age and failure in the face of nihilistic youth; and Invisible Target, which boasts an old-fashioned Hard Boiled demolition derby, with a police station ground zero this time. Horror fans already know how uneven HK films in that genre can be, but surely Fruit Chan Goh’s Dumplings is an admirably creepy achievement, and Soi Cheang Pou-soi did good work in the genre as well (Diamond Hill, Horror Hotline) before moving to the suspenseful Love Battlefield and the harsh action picture Dog Bite Dog.

Whew! After seven sword-like days, I’m running out of time, and I haven’t achieved a final victory. Want more dangerous encounters? Go to PHK or the Hong Kong Critics Society Award winnerss and start looking for your better tomorrow.

Sorry, I couldn’t resist.

Kristin and I discuss film festivals as an aspect of global film culture in Chapter 29 of Film History: An Introduction. For detailed research into the festival scene, see Richard Porton, ed., Dekalog 3: On Film Festivals and several publications from St. Andrews University. The most recent volume, edited by Dina Iordanova and Ruby Cheung, focuses on East Asian events.

P.S. Thanks to Yvonne Teh for a title correction, and Tim Youngs for a geographical one!

Photo: Joanna C. Lee, courtesy Ken Smith.

PLANET HONG KONG now in cyberspace

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run a daily string of entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have a chance to raise in the text. This is the first one. The second, a quick overview of the decline of the industry, is here. The third, on principles of HK action cinema, is here. The fourth, a photo portfolio of HK stars, is here. The following ones deal with western fandom, some Hong Kong directors, and final reflections on film festivals and a list of other intriguing movies. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D.

± 25 classics: A cheat sheet

Rouge (1988).

I have an aversion to list-making (some day I’ll explain), but I’m often asked to recommend Hong Kong movies to people wanting a quick start. So I’m launching this suite of daily entries around Planet Hong Kong by charting some widely recognized high points in this effervescent cinema.

Some items are important for their historical influence, some for their intrinsic quality, some for both. I’m restricting myself to the years after 1960, although there are several influential and powerful films before that (e.g., In the Face of Demolition, 1953). Still, if you want a fair sample of this cinema’s output you must sample these more or less official classics. If the bug bites, you can supplement them with other items that I’ll mention in passing here and in the days to come. Several of these films are discussed in more detail in the book, and most are available on DVD.

The Wild, Wild Rose (1960): Cathay (to use its shortest name) was one of the two major companies of the 1960s and in this brassy show-business drama Grace Chang (Ge Lan) had her defining role as the Carmen of the nightclub scene. Another Grace Chang classic is Mambo Girl (1957), and you can get a sense of the gorgeous star culture of Cathay by seeing her and other top actresses in Sun, Moon, and Star (1961), sort of a Hong Kong Gone with the Wind.

The Love Eterne (1963, above): This adaptation of the “plum-blossom” opera was given lavish treatment by the Shaw Brothers studio, the major studio of the period. Li Han-hsiang’s spectacle of colorful costumes, big studio sets, and gender masquerade won several awards and helped establish Hong Kong films across Asian markets. Li went on to make many other sumptuous costume pictures, as I discuss briefly here and in subsequent entries. This web essay focuses on Shaws’ anamorphic output.

Come Drink with Me (1966): The first Shaw entry in its new martial arts cycle, pioneered by King Hu. In an inn various characters in disguise meet and bluff one another; eventually the woman warrior Golden Swallow takes on all comers. Strictly speaking, King Hu’s other films belong to Taiwanese cinema, but he is one of the greatest of all Chinese directors, so you will naturally want to see Dragon Gate Inn (1967), The Fate of Lee Khan (1973), The Valiant Ones (1975), and his official masterpiece, A Touch of Zen (1971). I give him a fair amount of space in Planet Hong Kong because of his historical importance and his innovations in the aesthetics of action. I talk a little about those innovations here.

Golden Swallow (1968): Shaws’ dominant director from the late 1960s onward, Chang Cheh specialized in films of “staunch masculinity,” martial arts pictures that replaced the female-centered romances and opera films. Golden Swallow shows the woman warrior, the nominal protagonist, muscled aside by a typical brooding Chang hero—Jimmy Wang Yu, acting as if he still nursed a grudge from being The One-Armed Swordsman (1967). Later Chang developed the masculine pairing of Ti Lung and David Chiang Da-wei (Blood Brothers, 1973) and the brawny teamwork of what came to be known in the West as the Five Venoms (as in Invincible Shaolin, 1978).

Fist of Fury (1972): Child star Bruce Lee came home from Hollywood, and his first kung-fu film, The Big Boss (1971), was a sensation. The most influential star in all Hong Kong cinema, Lee stands at the center of his classics; the plots, staging, and shooting simply set off his glowering charisma. Fist of Fury provides a string of archetypal scenes: he wipes the floor of a dojo with its students and master, he kicks to splinters a sign barring Chinese from a park, and he ends his life by hurling himself, shouting, into a hail of bullets. Remade as the no less enjoyable Fist of Legend (1994) with Jet Li.

The House of 72 Tenants (1973): The success of Shaw Brothers’ export-driven Mandarin-language product led to a decline in films made in Cantonese, the local language. (Hong Kong audiences heard Bruce Lee dubbed into Mandarin.) 72 Tenants, based on a popular play, brought back Cantonese cinema in a crowd-pleasing guise. Under the direction of veteran Chor Yuen, the crisscrossed stories of neighbors became an enduring reference point for local cinema—cited again last Lunar New Year in 72 Tenants of Prosperity.

The Private Eyes (1976): Another victory for Cantonese vernacular cinema. The Hui brothers, popular from television, brought their episodic sight-gag comedy to the big screen and were among the biggest stars of the 1970s. There are many classic scenes, including Michael and Sam’s sleight of hand with candies, a shark attack in a kitchen, and a bout of chicken aerobics—plus a weird contagion of neck braces. See also Security Unlimited (1981) and, for fairly daring mockery of Beijing, The Front Page (1990).

The 36th Chamber of Shaolin (1978). As his employer Shaw Studios was fading from the scene, Lau Kar-leung (aka Liu Chia-liang) created in nearly twenty films a virtual encyclopedia of the kung-fu tradition. Any choice among the films is arbitrary (I’ll mention more in a future entry), but let this exuberant display of color, movement, and emotion stand as an outstanding accomplishment. A young man burning with rebellion enters the Shaolin monastery. Through persistence and discipline he achieves the highest distinction and returns to his home town to fight the Manchu oppressors. Featuring the director’s brother Gordon Lau Kar-fai and Lo Lieh, both martial-arts icons.

Young Master (1980): Jackie Chan’s comic kung-fu caught fire in Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow (1978) and Drunken Master (1978). Young Master is a prime instance of his rubbery energy and bottomless masochism. It benefits from extended byplay with Yuen Biao, splendid jumper, and Shek Kin, patriarch of the Hong Kong martial arts movie. Soon Jackie would show both ambition and directorial prowess in Project A (1983), his leap into big budgets and pan-Asian superstardom.

Aces Go Places (1982): The most successful franchise in Hong Kong history was launched by this jaunty action comedy, stuffed with pratfalls and high-tech chases. The buffoonery was carried off by an unruffled Sam Hui Koon-kit and a sprightly Sylvia Chang Ai-chia, not to mention the robots. Any film is improved by robots.

Boat People (1982): Ann Hui On-wah, a practitioner of serious drama for over thirty years, established her reputation in world cinema with this poignant story about a photographer’s discovery of children cast out by war. Her earlier film about Vietnamese refugees, Story of Woo Viet (1981), gave TV actor Chow Yun-fat his first major film role. Another characteristic Hui work is Song of the Exile (1990).

Zu: Warriors of the Magic Mountain (1983) Which early film by Tsui Hark to choose? The Butterfly Murders (1979) looks forward to his recent Detective Dee; the hectic We’re Going to Eat You (1980) suggests Romero turned loose in China; many critics pick Dangerous Encounter—First Kind (1980), a rough-edged Buñuelian indictment of class differences. With Zu, however, Tsui showed his resolve to update classic genres, in this case the Cantonese swordplay fantasy, using modern technique and special effects—a trend that has continued right up to the recent Storm Warriors (2010). Go here for more thoughts on Tsui.

Police Story (1985): Possibly Jackie Chan’s directorial masterpiece. A rip-roaring auto chase through a hillside shantytown, capped by a runaway bus, would be the climax of any other movie, but here it’s just for openers. The film ends with a fight in a shopping mall that, for precision and visceral impact, deserves to be ranked with the great sequences in film history. More on this scene here.

Peking Opera Blues (1986): The woman warrior’s shining hour, complete with the obligatory cross-dressing. Tsui Hark moves toward historical action/ adventure in a breathless movie that showcases three great beauties: Brigitte Lin Ching-hsia, Sally Yeh, and Cherie Chung Cho-hung.

A Better Tomorrow (1986): The film that defined a generation and cemented Chow Yun-fat’s star stature. John Woo came out of Taiwanese exile to make a film that revived the Chang Cheh spirit of brotherhood, made even more romantically doomed by the idea that Hong Kong was living on borrowed time.

Rouge (1988): A courtesan’s ghost revisits contemporary Hong Kong and finds that no one else is willing to die for love—not even the man who pledged to join her in death. Stanley Kwan Kam-pang’s delicate yet straightforward handling of the plot, refusing all special effects, gives an extra poignancy. Others would suggest Kwan’s Centre Stage (aka Actress, 1992), a biographical study of the great film star Ruan Lingyu.

The Killer (1989): The Chow/ Woo collaboration that brought them to the attention of the West. Often imitated, at home and abroad, the original retains its bold lyricism and outlandish emotion: crime and punishment as (mostly male) melodrama, accompanied by cadenzas of annihilation. To be supplemented by A Better Tomorrow II (1987), Bullet in the Head (1990), and Hard Boiled (1992), all of which brought awed fanboys to their knees.

God of Gamblers (1989): A financial triumph for bad-boy producer/director Wong Jing and the definitive gaming movie for a town that loves a bet. Shamelessly cheesy in its plot mechanisms, surprisingly elegant in its direction, the movie yanks us from laughter to pathos. Plus Chow Yun-fat in a tuxedo. To be seen alongside Stephen Chow Sing-chi’s parody All for the Winner (1990).

Days of Being Wild (1990). Wong Kar-wai’s breakthrough film about young people adrift in the early 1960s. A dazzling array of stars (Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing, Maggie Cheung Man-yuk, Andy Lau Tak-wah, et al.) creates a languid movie about the magnetic pull of selfish passion. For many local critics, the most important film of the last thirty years. I discuss a rare alternate version of the film here.

Once Upon a Time in China (1991): Tsui Hark doing Movie Brat revisionism again, this time with the Southern Chinese folk hero Wong Fei-hong. This flamboyant exercise in fervent nationalism ushered Mainland wushu champion Jet Li onto the world stage. If Bruce Lee radiated a cocky sexual energy, this film helped establish Li’s star image as a shy and chaste warrior.

Chungking Express (1994)/ Ashes of Time (1994): A coin-flip. The first showed that Wong Kar-wai could make a movie fast, cheap, and charming. The second showed that a swordplay film could be drenched in romantic longing. Both bristled with audacious storytelling tactics. Chungking spliced two stories together (prefigured in the way characters bump into each other), while Ashes zigzagged and spiraled in time, refusing plot certainties but offering a hypnotic reverie instead. Western critics and fans, notably one Q. Tarantino, sat up and noticed. PHK devotes an entire section to Chungking; go here for more on Ashes of Time.

The Mission (1999): Johnnie To Kei-fung’s stealth classic. Made on a shoestring, shot in less than three weeks (without a developed script), filled with great character actors, this ascetic polar has some of the subtlest plot twists in Hong Kong film. If Kitano Takeshi in his prime had made a Hong Kong film, it might look like this. Of course the mall shootout has become a classic.

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000): This US-Hong Kong-Taiwan project showed that the world was ready for the wuxia pian, or film of heroic chivalry. CTHD became the top-grossing foreign-language film in U. S. history. The versatile Ang Lee centered the drama on two couples, one young and one older, and their life in the jianghu–that virtual, larger-than-life world of forests and rivers that tests warriors’ righteousness. Lee’s film prodded Zhang Yimou to make the artier Hero (2003), first in a procession of historical dramas that helped revive the Mainland film industry.

In the Mood for Love (2000): Julia Roberts’ favorite movie, I’m told. Revisiting the period and perhaps some of the characters of Days of Being Wild, Wong Kar-wai evokes muffled yearning through averted glances, hidden faces, radiant costumes, and a typically spine-tingling soundtrack. This Cannes prizewinner was given a sequel, 2046 (2004), that is harsher but no less romantic in its commitment to cherishing the past.

Infernal Affairs trilogy (2002-2003): A deliberate effort to break away from the hell-for-leather action film, the IA trio showed that Hong Kong filmmakers could construct a taut, restrained crime plot. The first installment is a compact, efficient suspense exercise, the second a wide-ranging exploration of betrayal, and the third a fairly daring experiment in time-shifting and subjectivity. Many recent crime films have taken their cues from the trilogy’s huge box-office success. Portions were remade as The Departed, and for once it was the Hollywood movie that was overblown (not least the contribution of Mr. Nicholson). I set down some thoughts on the two versions here and here.

Kung Fu Hustle (2004): Stephen Chow purists may consider it a case of comedic elephantiasis, but this big-budget extravaganza is historically significant for winning worldwide distribution and big box-office. Kung Fu Hustle is also packed with engaging CGI-enhanced gags, on every scale from tenement demolition to cobra-smooching. One of the funniest scenes will encourage you not to use the phrase “hair on fire.” The even more inventive Shaolin Soccer (2001) was Chow’s previous step toward making movies at once China-friendly and globally marketable; not for nothing is his company called The Star Overseas.

Later this week I’ll offer a list of other Hong Kong films that I think are worth attention. (So wait until you’ve seen all my picks before writing me to point out titles I’ve omitted here!) And somewhere I’ll try to wedge in some outstanding sequences. This is nothing if not a cinema of rousing set-pieces.

Nearly all the films I mention are available on DVD, with European and American editions usually being of superior quality to Hong Kong editions. Many of the filmmakers mentioned are discussed in other entries on our site; check the Directors category on the right.

In 2005, Chinese critics assembled a list of the 103 best films from the PRC, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. That list can be found here.

PS 3 Feb: Another list of top Chinese films, tilted somewhat toward Taiwan, is here.

A Better Tomorrow (1986).