Archive for the 'Film technique: Music' Category

Oscar’s siren song: The return: A guest post by Jeff Smith

A Star Is Born.

As you probably know, Jeff Smith has been our collaborator on Film Art: An Introduction and our Criterion Channel series “Observations on Film Art.” For the last few years (here and here and here), Jeff has offered his thoughts on the Academy’s music nominees. This time around, he concentrates on the songs.

Here’s a brief preview of the Best Original Song category in this year’s Academy Awards. I also include a prediction for this year’s winner. Of course, I’d be the first to admit I don’t even win my own Oscar pool. So you’ll want to take that into account before making any wagers.

A good old-fashioned tune

Mary Poppins.

The Academy has a long history of nominating songs from live action and animated musicals. This year is no exception.

“The Place Where Lost Things Go” from Mary Poppins Returns fits that bill, giving Disney a third straight nomination in this category. (“Remember Me” from Coco and “How Far You’ll Go” from Moana are the others.) Like the Sherman Brothers, who wrote songs for the original Mary Poppins, Marc Shaiman and Scott Wittman derived inspiration from British Music Hall.

In fact, although actor Lin-Manuel Miranda insisted that he didn’t want his character to sound like Hamilton, Shaiman and Wittman wrote a patter section of “A Cover is Not a Book” for him, enabling Miranda to show off his unique skill set. With its tricky wordplay and fast pace, the classic patter song is a forerunner of the rhymes spat by rap and hip-hop artists. As Shaiman noted, “So we got very lucky there because we didn’t want to feel like we were pandering to the audience, to supply Lin with rap that would seem anachronistic.”

“The Place Where Lost Things Go” sits on the opposite side of the musical spectrum as a soft, mid-tempo ballad scored for strings and winds. Fans of the original Mary Poppins will note that it bears more than a faint resemblance to “Stay Awake.” Both songs are sung to the Banks children at bedtime in an effort to inveigle them to sleep. Whereas “Stay Awake” shows the über-Nanny using reverse psychology, “The Place Where the Lost Things Go” is a paean to memory, loss, and grief. The children’s mother has recently died and they further risk losing their beloved house. Mary Poppins reassures the children that they will be reunited one day with all their loved ones and that, in the meantime, their mother will forever have a place in their hearts.

The number is beautifully sung by Emily Blunt and it captures the sense of melancholy that gives Mary Poppins Returns its emotional heft. Still, it seems like a long-shot to take home the award. I admire Marc Shaiman’s work. He has written some absolutely iconic scores in the past, like The American President. And I’d love to see him recognized this Sunday, even if it is just for his phenomenal work on South Park: Bigger, Longer, and Uncut. But I fear that an Oscar statuette with his name engraved upon it is also in the place where the lost things go.

When corn meets pone

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs.

The second nominee is David Rawlings and Gillian Welch’s “When a Cowboy Trades His Spurs for Wings.” It appears in the comically violent opening story of the Coen Brothers’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. It is sung as a duet by the titular character and the Kid, a mysterious gunslinger dressed in black. Buster has just been shot dead in a duel. In the song, the Kid imparts some lessons learned from his short, rugged life as a cowboy with Buster chiming in to provide harmony. Kid’s grimly acknowledges that he will suffer the same fate as Buster. It is just a matter of time.

Rawlings and Welch are long-time collaborators, having worked together on the former’s debut album. Rawlings has also produced albums by Welch and by Willie Watson, who plays the Kid. Adding to the sense of family reunion is the fact that Welch provided the voice of one of the Sirens in O Brother Where Art Thou? Among those enchanted by the Sirens? You guessed it – Tim Blake Nelson, who plays Buster.

In an interview in Variety, Welch describes the absurdity of the original pitch the Coens made to her and Rawlings:

It was a pretty straightforward thing: “Well, we need a song for when two singing cowboys gun it out, and then they have to do a duet with one of ‘em dead. You think you can do that?” “Yeah, I think we can do that,” she laughs.

In crafting the song, Rawlings and Welch pull off a rather neat trick. They’ve created something evocative of the “singing cowboy” films that inspired the first segment of The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. Yet is also connects with a larger tradition of mournful ballads that are part of folk and country music history. A lilting Texas waltz, the number is sparsely orchestrated, relying largely on guitar, harmonica, and vocals. The lyrics also make reference to a “bindling sheet.” As Welch noted, the word “bindling” was something she and Rawlings made up as a gesture toward the Coens’ fondness for anachronistic language. Yet it also works as a clever allusion to the “white linen” that is wrapped around a dying cowboy’s body in “Streets of Laredo.”

As was the case with Mary Poppins Returns, this song perfectly blends music and narrative, beautifully capturing the darkly humorous sensibility characterizing the Coens’ career. The lyrics are solemn, but Tim Blake Nelson’s yodeling lightens the tone to keep it from seeming maudlin. If I had a vote to cast, this is where I’d put it. Yet my gut tells me that the Academy’s beacon will shine on one of the other nominees.

A song for one of the Supremes

Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

The third nominee, “I’ll Fight,” was written by Diane Warren, a longtime Academy favorite. The song represents Warren’s tenth nomination, but she has never taken home top honors. This year, in an ironic twist, she may lose out to former co-writer Lady Gaga. (The two were nominated for “Til It Happens to You” in The Hunting Ground.) Warren admits that “I’ll Fight” is another of her “call to arms” songs as she has turned more of her energies toward films that support social causes.

One can easily make a solid prima facie case for “I’ll Fight” as the song to beat. It features a strong, soaring vocal performance by Jennifer Hudson, a previous Oscar winner for Dreamgirls.

Warren’s melody and lyric capture the inspirational vibe that is found in several previous winners, most recently “Glory” from Selma. And, of course, Warren herself seems long overdue.

Even so, “I’ll Fight” has a number of things working against it. It is featured in a documentary, and documentaries usually don’t get the exposure of more mainstream releases. It appears over The RBG’s closing credits, which mostly restricts the song to a summative function. And, unlike “All the Stars” and “Shallow,” the song failed to chart, an indication that it didn’t get much exposure in the music marketplace. I feel confident that Warren’s opportunity to make an acceptance speech will come someday. But on Oscar night, she’ll once again be the “bridesmaid” rather than the “bride.”

The battle of the titans

Black Panther.

For me, the race comes down to the remaining two nominees: “All the Stars” from Black Panther and “Shallow” from A Star is Born. Both tracks have gotten extraordinary exposure outside the films in which they appeared. The former was a chart hit in 25 countries, garnering steady radio airplay and thousands of streams and downloads in the process. The latter arguably did even better, charting in 40 countries, selling nearly 600,000 downloads and accruing almost 150 million streams. Both songs are fueled by star power: hip-hop sensation Kendrick Lamar for “All the Stars” and pop diva Lady Gaga for “Shallow.”

Lamar has just the right profile to woo Academy voters, even those in the music branch for whom “big beatz” and “flow” seem like foreign concepts. He has won thirteen Grammy Awards as well as the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for Music, becoming the first artist to do so from outside the domains of classical and jazz music. Billboard even compared Lamar to Shakespeare.

Although some music critics argue that “All the Stars” is not entirely typical of Lamar’s and SZA’s respective styles, it does fit beautifully with the overall vibe of Ryan Coogler’s pathbreaking film. The song begins with loping rhythms, electronic textures, and auto-tuned vocals. When Lamar drops the beat in the chorus, “All the Stars” gains intensity thanks to the layering of additional synthesizers and SZA’s melismatic topline.

The overall effect is one that neatly draws together Black Panther’s principal settings, being equal parts Wakanda and Oakland. The tension in the lyrics between the sung choruses and Lamar’s linguistic turns also restages the film’s central conflict: Prince T’Challah’s policy of peaceful co-existence vs. Killmonger’s thirst for violent world revolution. Appearing over the end credits, the number also works brilliantly with the shifting lines, shapes, and textures of the sequence’s graceful animation.

Lady Gaga, of course, supplies “Shallow” with its vocal fireworks. But she shares her nomination with three other collaborators, all of whom cut pretty large figures in the world of popular music.

Chief among them is superproducer Mark Ronson, who twirled the knobs on Gaga’s fifth album, Joanne in 2016. Ronson is perhaps best known for his smash hit, “Uptown Funk.” Yet, Ronson had already won three Grammy’s for his production of Amy Winehouse’s Back to Black long before he gave us his Bruno Mars earworm. Besides his production work for Gaga, Winehouse, and Mars, Ronson has collaborated with a “who’s who” of current stars and pop music legends: Adele, Lily Allen, Miley Cyrus, Kaiser Chiefs, Chance the Rapper, Janelle Monae, Duran Duran, Nile Rodgers, and Paul McCartney.

One of Ronson’s other songwriting partners, Anthony Rossomondo, shares the nomination for “Shallow.” Rossomondo is a guitarist and trumpet player who was a founding member of Dirty Pretty Things and toured with the Libertines as Pete Doherty’s replacement. Fans of British television might also remember Rossomondo as Pete Neon in The Mighty Boosh, the surrealist comedy series about a pair of failed musicians working in an alien shaman’s magic shop.

Rounding out the quartet of songwriters is Andrew Wyatt, still another songwriting partner of both Ronson and Gaga, who also penned tunes for Mars, Lil’ Wayne, Beck, Florence + the Machine, and former Oasis bad boy, Liam Gallagher. Wyatt also has previous experience writing for film. He composed four songs for the Hugh Grant/Drew Barrymore romantic comedy, Music and Lyrics, including the wonderful pastiche of eighties New Wave, “PoP! Goes My Heart.”

With so much musical talent on board, it is hard to see how “Shallow” could miss. Yet the song’s many virtues are enhanced by its perfect placement in the story. It was a lot to expect that one song could deliver something that a) pays off the romantic sparks of Ally and Jackson’s initial flirtation; b) signifies Ally’s leap of faith as she returns to the stage to complete Jackson’s arrangement of her song; and c) convince the audience that Ally could legitimately be the proverbial overnight sensation of the film’s title. “Shallow” delivers on all that and more.

The song begins with Jackson singing, “Tell me something, girl.” The first verse is sparely arranged for just voice and acoustic guitar. Jackson essentially baits Ally into claiming a spotlight he believes is rightfully hers. When Ally comes on stage, she begins the second verse in the lower part of her vocal register, adding a husky sensuality that captures the slow-burn of the couple’s simmering passions. Piano, violin, and pedal steel guitar slightly thicken the arrangement while maintaining the relatively soft dynamic level. An octave leap leads into the chorus, which Ally belts out with newfound confidence.

The lyrics serve as a metaphor for the character’s personal journey, her willingness to take the emotional and professional risks that Jackson had encouraged. This is Ally’s moment of self-realization. Yet it also foreshadows the relationship’s failure by previewing a future in which her stardom will overtake his.

This is followed by Jackson and Ally finally harmonizing together on the phrase, “In the shallow, the sha-ha-low.” Their voices blend, suggesting the consummation of their romantic connection onstage, if not yet in bed. Ally follows with a kind of vocal cadenza. No longer bound by lyrics, she sets free the “yargh” in her voice that rock critic Greil Marcus famously ascribed to Van Morrison’s Irish soul.

The addition of drums and bass enhance the big crescendo that leads into the final chorus. Jackson joins Ally at her microphone and the two finish the song with a final duet. The song is in G major, but ends on an E minor chord, another subtle hint of the sadness that ultimately consumes couple’s relationship.

As an Oscar nominee, “Shallow” has a lot to offer. It is a duet between a major movie star and a major star of the recording industry. It not only pays off a previous dangling cause, but also foreshadows later plot developments. Best of all, it takes the audience on an emotional journey that symbolizes the characters’ story arcs in microcosm. If the snatch of “Shallow” heard in the A Star is Born trailer proved surprisingly meme-worthy, the full performance of it in the film was indelible. Moreover, in a cheeky bit of self-mythologization, it invites viewers to consider “Joanne,” the flesh-and-blood being that sits just behind the Gaga mask.

Prediction: “Shallow”

I likely tipped my hand earlier, but I fully expect Lady Gaga and company to add Oscar to the Grammy and Golden Globe they’ve already won. If that happens, I’ll be content with the result, even if the memory of Tim Blake Nelson and Willie Watson’s duet tickles me every time I think of it. I’ve enjoyed Mark Ronson and Lady Gaga’s music for more than a decade. And if nothing else, an Oscar for Andrew Wyatt will balance the scales of justice. Back in 2008, I felt Wyatt was robbed when he failed to secure a nomination for a song Billboard called “the greatest fake 80s song of all time.” Well, if I see Wyatt clutching an Oscar come Sunday, you’ll hear a little PoP! go in my heart.

For an alternate take on this year’s music nominees, a real pop star from the eighties, Thomas Dolby, offers his perspective here. A report on a panel discussion at the Los Angeles Film School featuring several of the nominees can be found here.

Marc Shaiman and Scott Wittman talk about their work on Mary Poppins Returns here and here.

Gillian Welch discusses working with the Coen Brothers on The Ballad of Buster Scruggs here and here.

Diane Warren offers her perspective on writing “empowerment anthems” here and here. A deep dive into Warren’s career can be found on a Hollywood Reporter podcast featuring the 10-time Oscar nominee.

Finally, much ink has been spilled about the process of writing “Shallow” for A Star is Born. You can read more here and here and here and here.

Jeff Smith has provided us many guest blogs related to film music, most recently his discussion of the score for True Stories.

Music and Lyrics (2007).

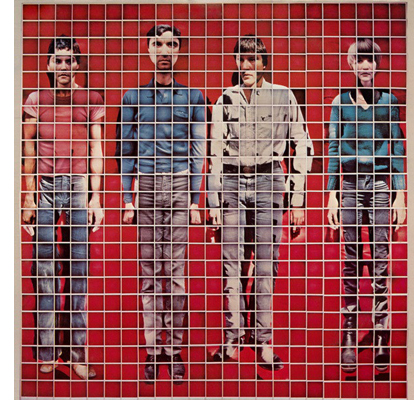

From transistors to transmedia: Talking Heads tell TRUE STORIES

True Stories.

Jeff Smith is no stranger to this blogsite. He has written several entries, some based upon his Criterion Collection commentaries for FilmStruck, others on topics related to film sound and scoring. Here he brings his massive expertise to bear on the music of True Stories, newly available in a 4K transfer from Criterion.–DB

Jeff here:

As promised, this is a follow-up blog to David’s discussion of True Stories and its collage of tabloid culture, kitsch, Performance Art, Robert Wilson, Andy Warhol, Jeff Koons, and Our Town. At least some of these connections also characterize the New York music scene in the 1970s from which Talking Heads emerged. Buoyed by the energy of punk and New Wave, Byrne had long straddled the boundaries between mass culture and the avant garde.

As before, Andy Warhol serves as something of a role model. Besides designing album covers for mainstream pop performers, such as the Rolling Stones, Billy Squier, and Diana Ross, Warhol also served as the nominal producer of The Velvet Underground & Nico. The artist himself is also the subject of David Bowie’s “Andy Warhol” from Hunky Dory and Lou Reed’s “Andy’s Chest,” an outtake that eventually surfaced on VU, the 1985 compilation of Velvet Underground miscellany.

Working in the opposite direction, Byrne and company’s connections to the Manhattan cultural scene gave their work a kind of artistic credibility. Yet their avant garde impulses were always counterbalanced by a veneration of the soul, funk, and blues music that shaped rock and roll’s art and history. In what follows, I trace the long and winding road Talking Heads took in their journey to True Stories, both as film and as album.

Making the scene

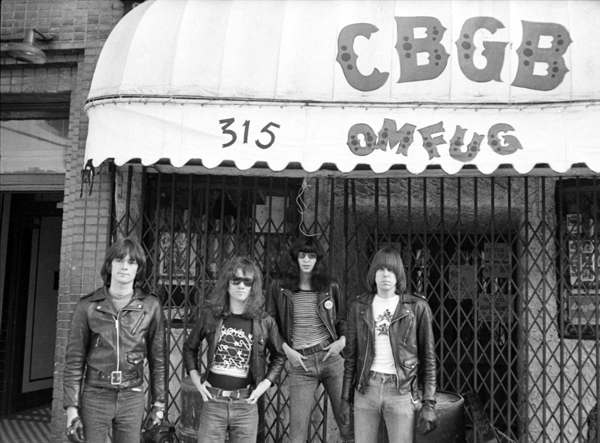

The Ramones at CBGB in the 1970s.

David Byrne’s band, Talking Heads, is almost certainly the most successful group to emerge from the downtown New York music scene of the late 1970s. Of the eight albums the band released between 1977 and 1988, seven of them were certified either gold or platinum. Little Creatures, the album released just before True Stories, went double platinum, selling more than two million units. So did Stop Making Sense, the soundtrack to their concert film directed by Jonathan Demme.

At the start of their recording career, much of the energy surrounding the New York music scene centered on the venerable East Village club, CBGB. Its name was short for “Country, Bluegrass, and Blues.” Yet the bands who came to be identified with the venue were about as far away from roots music as you could get. Initially, CBGB was associated with the emerging American punk rock scene. The Ramones were frequent performers as were the Plasmatics, Richard Hell and Voidoids, and Johnny Thunders’ band, the Heartbreakers.

Yet the range of musical styles represented at CBGB ventured quite far afield from the sped-up, chainsaw guitar sounds of punk. Patti Smith channeled her inner Rimbaud over Lenny Kaye’s Nuggets-inspired guitar lines. Television featured the evocative string-bending of Tom Verlaine. who stretched out in long solos using modal scales that fused Ravi Shankar with John Coltrane. James Chance and the Contortions showcased the wild saxophone playing of their frontman, specializing in a peculiar form of avant-funk jazz. Blondie began by refashioning sixties garage rock into their own brand of punk. But their style became more eclectic, branching out to include disco, calypso, and rap. They attained a huge crossover success in the process, thanks to lead singer Debbie Harry’s sex appeal and sultry alto.

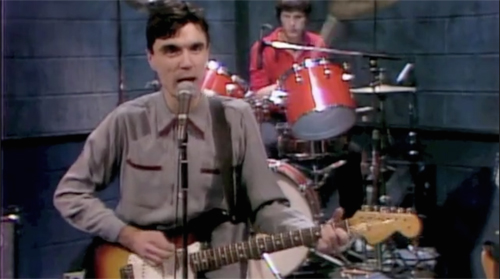

Talking Heads sounded like none of these. “New Feeling,” the second track on their debut album, established the template for the band’s music: skittering guitar lines, tightly wound rhythms, and David Byrne’s strangled yelp. Its spare, spiky pop sound featured the rhythmic interplay of Byrne’s and Jerry Harrison’s guitar lines and the precise sixteenth note fills of drummer Chris Frantz.

Talking Heads 77 occasionally added elements that slightly broadened their musical palette. Think of the steel drum sounds that color “Uh-Oh, Love Comes to Town” or the loping electric piano chords of “Don’t Worry About the Government.” Indeed, the latter wouldn’t sound out of place in a Sesame Street bumper.

Yet, the album’s flagship single was “Psycho Killer” for a reason. Its nervy energy epitomized the group’s sound in its early days at CBGB. This was rock and roll to be sure. But it seemed like the kind of thing the subject of Edward Munch’s The Scream would dance to if he ever got off that bridge.

Talking Heads’ follow-up, More Songs About Buildings and Food, initiated a period of fruitful collaboration with producer Brian Eno. Using synthesizers and other keyboard instruments to flesh out the band’s sound, Eno nudged the Heads toward more danceable tunes. Built on Tina Weymouth’s pliant, bouncy bass lines, songs like “Found a Job” and “Stay Hungry” saw the band incorporating elements of seventies funk, soul, and disco. The band’s cover of Al Green’s “Take Me to the River” also gave the group their first chart hit.

That single’s slow climb peaked the same week of Talking Heads’ television debut on Saturday Night Live. For many viewers, this was their first encounter with Byrne’s “Norman Bates meets Pete Townshend” persona. And, even though Byrne’s hipster nerd desperation seemed the absolute antithesis of Green’s “lover man” come-on, his apparent interest in exploring black musical idioms felt almost painfully sincere.

Bringing Noho to the bush of ghosts

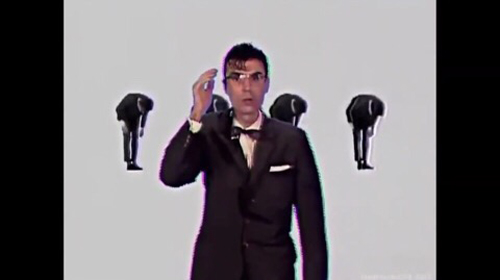

Music video for Once in a Lifetime.

Over the next three albums, the Heads’ collaboration with Brian Eno pushed them even deeper into world musical cultures. The band simplified their song structures, but increased the complexity of their arrangements and instrumentation. “I Zimbra” added Cuban, Brazilian, and African percussion along with the signature stylings of Robert Fripp’s guitar work. Remain in Light‘s densely layered synthesizers, various types of drums, and percussion atop the guitars, bass, and trap set that had been the core of the group’s sound since their first album. Created through countless overdubs that enabled each band member to play percussion alongside their normal instruments, the album featured extended Afrofunk and worldbeat grooves that interwove “call and response” vocal lines with intricate polyrhythms.

To recreate this sound on stage, the band recruited several players from other groups. On tour Talking Heads became a sort of New Wave supergroup with King Crimson’s Adrian Belew on guitar, Ashford and Simpson’s Steve Scales on percussion, and Funkadelic’s Bernie Worrell on keyboards. The expansion of Byrne’s musical vision was nothing short of stunning. Using improvised jams and communal music-making as a point of departure, Remain in Light went well beyond the faux gospel and art school irony of “Take Me to the River.” By mixing preachers’ rants with the wordplay of Bronx rappers, Byrne discovered his inner Fela Kuti.

Talking Heads start making cents (on sync licenses)

1983 would prove to be a watershed year for Talking Heads. The band released Speaking in Tongues, which spawned their first top ten hit, “Burning Down the House.” The record also represented a kind of apotheosis. It was less musically adventurous than Remain in Light. But it seamlessly blended the band’s early New Wave sound with its later Afrofunk influences. Instead of grooving on one chord, most songs on Speaking in Tongues contained more conventional harmonic changes. And instead of building songs out of shorter “loops,” the new record featured much more traditional song structures with clear demarcations of verses, choruses, and bridges.

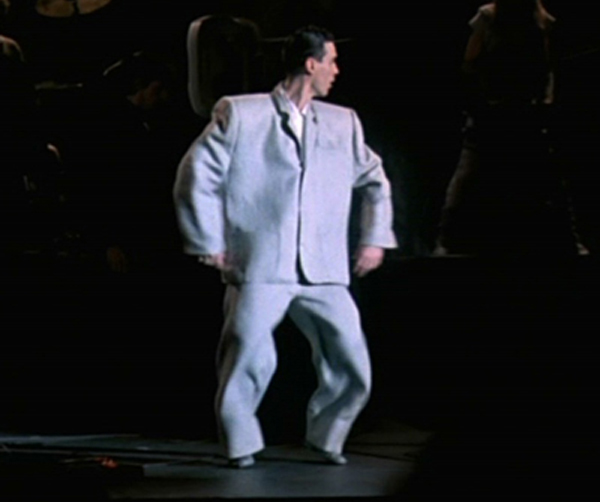

The album also served as the centerpiece of Jonathan Demme’s concert film, Stop Making Sense, which was filmed over four separate dates in December of 1983 at the Pantages Theater in Los Angeles. The set list more or less traced the history of Talking Heads, beginning with David Byrne performing “Psycho Killer” on an acoustic guitar accompanied by a rhythm track played back by a boombox. It closed with a performance of “Crosseyed and Painless” that featured the full tour ensemble, including Scales, Worrell, guitarist Alex Weir, and two female backup singers. In between, Byrne bounced around the stage in his big white suit, turning the concert stage into a space for performance art. As before, Byrne seemed to self-consciously reject the usual rock star poses. Instead, he shook, squirmed, and jerked like a giant white Gumby on a hot tin roof. Stop Making Sense went on to become a modest commercial success and won the National Society Film Critics award for Best Documentary of 1984.

Between 1983 and 1986, Talking Heads also saw their profile raised by the use of songs in other popular films. The group had already been featured in a motley group of titles prior to Speaking in Tongues. “Life During Wartime” was included in Alan Moyle’s Times Square (1980), a teen comedy about two aspiring punk singers in New York. But so was almost every other hot artist of the moment, such as Joe Jackson, Gary Numan, the Cars, the Cure, and the Pretenders. The Heads had also performed “Psycho Killer” in Bette Gordon’s short film, Empty Suitcases.

The industry surge in soundtrack sales in the early to mid-eighties, though, gave Talking Heads access to more high-profile studio projects. “Burning Down the House” made an appearance in the rowdy fratboy comedy, Revenge of the Nerds. And the use of “Once in a Lifetime” over the opening credits of Paul Mazursky’s Down and Out in Beverly Hills (1986) fueled the song’s return to Billboard’s Hot 100 more than five years after it was released.

A much more interesting case of music licensing occurred with the push given to “Swamp,” the opening track on side two of Speaking in Tongues. Robbie Robertson of The Band selected the song for inclusion on the soundtrack of King of Comedy (1982) well before the album was released. It then appeared again just months later in the Tom Cruise teen comedy, Risky Business. The reuse of “Swamp” so soon after Scorsese’s film might well be a case of serendipity. Paul Brickman, Risky Business’ screenwriter and director, likely glommed onto it when he heard David Byrne intone the phrase “risky business” in the song’s last verse.

“Swamp,” though, anticipated yet another change of direction in the band’s music. Unlike the worldbeat influences that were still evident in the rest of Speaking in Tongues, the track returned Talking Heads to American terra firma, more specifically the musical idioms of the Mississippi delta. A slow, blues shuffle tune with strong triplet rhythms, “Swamp” was truly unlike anything else the group had done before. Floating on Bernie Worrell’s funky synth textures, it sounded like a Parliament cover of an old Muddy Waters song. The fact that Byrne’s vocals deliberately mimicked John Lee Hooker just added to its overall strangeness.

But just as “I Zimbra” presaged Talking Heads’ foray into Afrofunk, “Swamp” foreshadowed the band’s turn toward American roots music. Their follow-up album, Little Creatures, showed the band branching out even further with the rollicking zydeco of “Road to Nowhere” and the soporific country weeper, “Creatures of Love.” All of this would eventually lead Byrne and co. to True Stories and to a state with a musical canvas almost as large as its geography: Texas.

More songs about voodoo and dreams

In the special features on Criterion’s excellent edition of True Stories, David Byrne acknowledges that his conception of the film was partly inspired by his admiration for Robert Altman’s Nashville. The resemblances between the two films aren’t hard to discern. Both films feature multiple protagonists and use setting to unify the film’s different plotlines. Both films include the perspectives of one or more outsiders — The Narrator in True Stories, Opal and John Triplette in Nashville — who serve as the viewer’s guide to the community each explores. Both films also involve preparations for a local celebration – the talent show, the political rally – to motivate musical numbers by a variety of performers, much in the manner of a revue or jukebox musical.

Texas is home to a distinctive mix of different kinds of “roots” music. Byrne was keen to capture that breadth. In an essay on the music written for True Stories, Byrne says, “I realized there was a lot to represent – rock, country, Tex-Mex, polkas, Latin, lounge jazz, disco, and some made-up genres, like an accordion marching band.” Trips to scout locations for the film brought Byrne into contact with a number of clubs and musicians. He then offered some local musicians an opportunity to contribute to the score. None of the groups represented is particularly well known outside of True Stories. Indeed, neither the Panhandle Mystery Band nor Brave Combo achieved even the modest fame accorded to Texas singers like Delbert McClinton or Freddy Fender. Still these local musicians definitely added to the “specialness” that Virgil represents.

In his collaborations with local musicians and the songs written for various actors to sing in True Stories, Byrne found himself serving two masters. On the one hand, Byrne wanted to pursue his vision for the film and to write songs that express the feelings and perspectives of various characters. On the other hand, though, Byrne also had to make sure these numbers still worked as Talking Heads tracks. It seems likely that Warner’s willingness to support the film depended upon the ancillary revenues they hoped to earn from the soundtrack. The Heads had been signed by Sire Records, a subsidiary of Warner Music. Given the band’s previous sales, a new Talking Heads album served as a hedge against the film’s disappointing box office.

Virgil wants its MTV

The three songs Talking Heads recorded specifically for the film – “Wild, Wild Life,” “Love for Sale,” and “City of Dreams” — are perhaps the best illustration of Byrne’s need to create corporate “synergy” in the relationship between True Stories and its music ancillaries. All of them are foursquare rock and roll songs. No doubt they reassured Warner Bros. that they had commercially marketable singles that could generate radio airplay and hopefully drive traffic to movie theaters. “Wild, Wild Life” would become the second biggest hit in the band’s history, peaking at #25 and spending about five months on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart.

Notably, though, Byrne insisted these weren’t genuine Talking Heads records. Instead, they represented the band’s attempts to sound like other popular artists. Byrne described the role models for these tracks:

The closing song, “City of Dreams,” is my version of a Neil Young anthem. Its lyrics echo the history lesson at the beginning of the film. “Love for Sale” was our version of a Stooges song, and “Wild, Wild Life” was my attempt at writing a song like something one might hear on MTV at the time.

Byrne doesn’t give us a lot to go on here, but we can discern at least some similarities between the songs and the artists he cites. On “City of Dreams,” Byrne’s voice doesn’t have the fragility that Young’s “high lonesome” tenor conveys. But the lyrics evoke the kind of imagery found in some of Young’s most famous songs, especially those that relate the experience of Native Americans. Indeed, Byrne’s verse about the Spanish search for gold wouldn’t seem out of place in “Cortez the Killer,” the standout track on Young’s 1975 album Zuma.

With its crunchy guitar riff and drum break, “Love for Sale” at least nominally sounds like it could be a track from the Stooges’ Fun House. It certainly channels some of the proto-punk energy that made the Stooges, especially lead singer Iggy Pop, a revered cult band in the early seventies. Yet Talking Heads’ performance shows their customary clockwork precision, and the record generally lacks the kind of wild abandon that one associates with the Stooges’ best tracks. Eric Thorngren’s audio engineering of “Love for Sale” also adds a layer of studio polish that an album like Raw Power most pointedly refuses. In an odd way, the recording gives us some insight into how the Heads might have sounded had they been a punk band in their CBGB days.

Perhaps the bigger irony here is that the song functions as an interpolated music video watched by the Lazy Woman during a bout of channel surfing. It shows Byrne’s usual eye for inventiveness within the form: silhouettes, primary colors, and a surrealist arc in which each band member is molded into a chocolate figurine wrapped in foil. Yet here is where the similarity between the Heads and Stooges ends. Iggy Pop may have been known for pouring oil or honey on his body during Stooges concerts. But in 1986, the Stooges were about the last band one would expect to see on MTV.

“Wild, Wild Life” is motivated in a similar way. Heard in a Virgil dance club, much of the film’s cast lip syncs to it against a bank of video monitors. Like “Love for Sale,” this footage became the basis of a very successful music video promoting the film. In a bit of an in-joke, guitarist Jerry Harrison twice appears onscreen dressed as an iconic rival artist: first as Billy Idol, then as Prince. (Note that Tina Weymouth also appears with Harrison as a fetching Apollonia.) Still, the lack of specificity in Byrne’s description suggests that it was Talking Heads’ attempt to make a rather generic pop record. In contrast to the film’s celebration of “specialness,” Byrne’s explanation of the song’s purpose functions as a backhanded critique of MTV’s role as tastemaker. In trying to sound like everyone, “Wild, Wild Life” fit quite snugly into the music network’s video rotation.

The sage in bloom is like perfume

The film’s remaining songs are performed by characters. They illustrate Byrne’s desire to capture the breadth of Texas’ musical culture in a variety of idioms. Other bits of music are also interspersed between these numbers. There are snatches of nondiegetic score based on Byrne’s two “dream” songs (“City of Dreams” and “Dream Operator”). Meredith Monk contributed a brief minimalist theme that is featured in the film’s opening and closing scenes. It is perhaps the clearest reminder of Byrne’s outsider status, enveloping the film within the sounds of the downtown Manhattan arts scene. It also includes Carl Finch’s “Buster’s Theme” as music played during True Stories’ infamous accordion parade.

At least two songs evoke the swamp pop of Eastern Texas, which shares much of its sound with the music of New Orleans. “Hey Now” features the simple tonic/dominant changes and “call and response” strophic patterns heard in second line parades during Mardi Gras. Sung by children, it sounds like a modernized version of the Dixie Cups classic, “Iko Iko.”

“Papa Legba,” on the other hand, carries a more pronounced “island vibe,” conjuring the Cuban and Jamaican styles that were such an important influence on Dave Bartholomew, Fats Domino, and Lloyd Price. Performed by the great Pops Staples, the style is apt since the song is ostensibly an appeal to a central figure in Haitian folklore. (Legba is a demigod in voodoo culture who facilitates communication between living beings and the souls of the dead.) Staples expressed concern about this scene. The actions of his character, Mr. Tucker, ran squarely against the actor’s Christian faith. Yet, despite Staples’ literal embodiment of the “magic negro” trope, Tucker’s actions here come across as rather benign. He acts on Louis’ behalf, and both characters seem so decent and honest that their resort to sorcery seems quite harmless.

In other films and television shows, such as Crossroads or American Horror Story, Legba is often trotted out as a stand-in for Satan himself. In True Stories, though, Tucker’s Legba number is a slightly less hokey version of Leiber and Stoller’s “Love Potion # 9.”

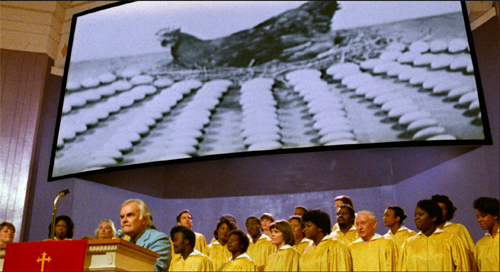

“Puzzling Evidence” is a straightforward gospel number, delivered from the pulpit by John Ingle as The Preacher. As an enumeration of possible conspiracies, the scene might seem today as QAnon avant la lettre. But sober reflection suggests the song is further evidence that Richard Hofstadter’s “paranoid style” of American politics has a long and rich history.

“Radio Head” represents the rich tradition of Hispanic styles in Texas musical culture: Tejano, conjunto, orquesta, mariachi, corrido. As performed by Tito Larriva, the tune borrows heavily from conjunto, which originated in the 1870s and fuses Spanish and Mexican vocal styles with the polkas, waltzes, and Mazurkas played by German and Czech immigrants. A central element of conjunto is the combination of 12-string guitars with button accordions. The latter has a distinctive reedy, yet sweet timbre contrasting that of the piano accordion.

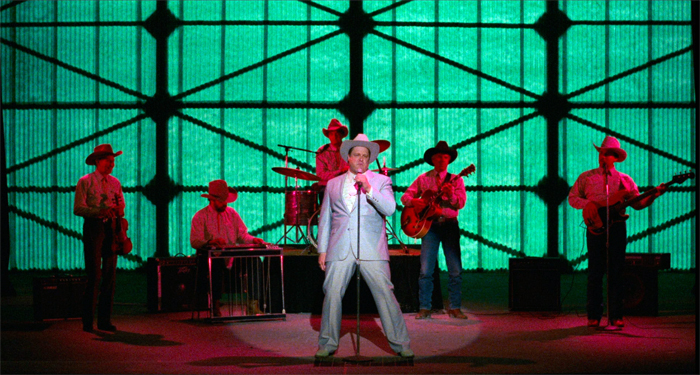

“Dream Operator” and “People Like Us” round out Byrne’s portfolio by borrowing different from different strands of country music. The former is a shimmering waltz reminiscent of the Texas Troubador, Ernest Tubb, and the Western swing style of Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys. “People Like Us,” which is performed by Louis at the talent show, is an up-tempo slice of neo-honky tonk that features the requisite fiddle and steel guitars. The lyrics also voice the kinds of populist sentiment that became di rigeur in the genre by the 1980s.

At its best, in the music of Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard, George Jones, and Loretta Lynn, country music spoke eloquently of the simple pleasures of nature and family. It also explored the problems of ordinary folks, such as infidelity, divorce, and alcohol abuse. At its worst, though, such populism lapses into knee-jerk jingoism.

Byrne’s lyrics gesture toward the former of these two strains. It attests to certain Texas values: stubborn pride, an independent streak, and a resilience in hard times. Louis’ seeming humility and sincerity proves to be catnip for the Lazy Woman. She proffers the marriage proposal that Louis has sought throughout the film. In providing the resolution to the central plotline, “People Like Us” brings the narrative and Byrne’s musical journey through Texas to a fitting conclusion.

Changes in latitude, changes in attitude

For me, perhaps the most striking thing about “People Like Us” is its distance from Talking Heads’ early work. Compare it, for example, with “The Big Country,” the closing track on More Songs About Buildings and Food (below). Here Byrne’s narrator assumes a God-like view of the U.S. and its “people down there.” Imagined from maps and viewed from airplanes, the lyrics survey a cornucopia of Americana in the references to ball diamonds, whitecaps, farmlands, highways, and buildings. Yet, each chorus undercuts this encomium to the “big country” by concluding “I couldn’t live there if you paid me.”

In conversation David (Bordwell rather than Byrne) often praises “the spontaneous genius of the American people.” Is Byrne doing the same in True Stories with its portrait of small-town life as a mixture of performance art and irresistible kitsch? Or does he still occupy the previous Godlike position described in Louis’ song, laughing disdainfully at “people like us?”

At the end of the day, I think it is impossible to truly know. If we take Byrne at his word that his songs for True Stories aren’t Talking Heads songs, then there really isn’t a contradiction. He set out to write songs in the voices of his characters and in the style of musicians quite distinct from Talking Heads. Louis is not Byrne, and therefore “The Big Country” stands on its own as a wonderful, if contemptuous take on American life.

At the end of the day, I think it is impossible to truly know. If we take Byrne at his word that his songs for True Stories aren’t Talking Heads songs, then there really isn’t a contradiction. He set out to write songs in the voices of his characters and in the style of musicians quite distinct from Talking Heads. Louis is not Byrne, and therefore “The Big Country” stands on its own as a wonderful, if contemptuous take on American life.

Yet somehow invoking the old distinction between “author” and “narrator” obscures something important about the way True Stories fits into Talking Heads’ history as a band. The songs Byrne wrote for the film seem like a culmination of the group’s turn toward American roots music in the mid-1980s. Moreover, as Byrne has shown as an impresario for his own Luaka Bop label, he has genuine admiration for an enormous variety of vernacular pop idioms. In its own way, Talking Heads’ absorption of regional American musics on Little Creatures and True Stories might be viewed as signs of artistic growth rather than the stylistic poaching of smartasses from Manhattan.

Still there is a third possibility. As my colleague Jonah Horwitz pointed out to David and me, True Stories also seems to bear a strong relation to the Lovely Music movement epitomized by Robert Ashley, “Blue” Gene Tyranny, and Peter Gordon. In Jonah’s words, this axis of modern composition is “characterized by a suspension of judgement, gaping appreciatively at the banality/beauty of America and Americans, bridging the gap between structural/minimalist ‘new music’ and popular forms like rock and country music and soap opera.”

But is this appreciative gaping is really just postmodernist snark? Adrian Martin suggests as much in his original review of the film. And faux sincerity, in and of itself, might be viewed as the deepest, most pernicious form of cynicism. Taking particular issue with the chorus of “People Like Us,” Martin writes, “According to this reading, which the film abundantly invites, its viewpoint is immaculately distant and sneering.” Citing its “patronizing, condescending tone,” Martin ultimately bemoans the fact that True Stories draws attention away from more “authentically funky little American films” that won’t get seen.

Is this ultimately where Byrne lands? Perhaps. The lyrics certainly can be viewed as a faux naif expression of Redneck stupidity.

We don’t want freedom

We don’t want justice

We just want someone to love

But if we dismiss “People Like Us” as evidence of authorial condescension, one misses the key insight that the song has to offer. Much hedonics research suggests that there is a more complex way of understanding such sentiment.

Freedom and justice may be necessary conditions of human happiness, but they are hardly sufficient. Abstract ideals ultimately don’t mean much absent the human connections that define our workaday world. Such craving for social interaction and a feeling of belonging is one reason why respondents in hedonics studies claim they would forgo a $10,000 raise for the opportunity to become a member of a small, but active club. Moreover, neuroscience also shows that romantic love produces a sense of electrochemical wonder within the brain. Not all of these changes are positive ones, but the flood of dopamine that accompanies sexual attraction helps explain why love can be both pleasurable and addictive.

Viewed from this perspective, Louis’ sentiments in “People Like Us” are far from guileless. By emphasizing toughness and resilience, the song asserts that homeostasis is possible even in the most hardscrabble life. And life is made rewarding and meaningful by the social bonds that unite us in a common humanity. Perhaps folks out there will see me espousing a version of the feigned sincerity for which True Stories is equally guilty. But given the way Byrne’s film judders my own pleasure center…. Well, let’s just say I’ll proudly wear my heart on my sleeve.

Thanks to David Byrne, Ed Lachman, Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Lee Kline, Ryan Hullings, and the rest of the Criterion team for this edition. The quotation from David Byrne comes from the booklet accompanying the disc.

Thanks also to Jonah Horwitz for helpful comments on the music, and Adrian Martin for signaling his critique of True Stories.

Other work by Jeff relevant to this analysis includes The Sounds of Commerce: Marketing Popular Film Music (Columbia University Press, 1998) and his survey of the field ”The Tunes They are a-Changing’: Moments of Historical Rupture and Reconfiguration in the Production and Commerce of Music in Film,” in The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies, ed. David Neumeyer (Oxford University Press, 2013).

True Stories.

Everything new is old again: Stories from 2017

Silence.

DB here:

This is a sequel to an entry posted a year ago. Like many sequels, it replays the ending of the original.

I don’t want to leave the impression that as I’m watching new release a little homunculus historian in my skull is busily plotting schema and revision, norm and variation. I get as soaked up in a movie as anybody, I think. But at moments during the screening, I do try to notice the film’s narrative strategies. Later, when I’m thinking about the movie and going over my notes (yes, I take notes), affinities strike me. By studying film history, most recently Hollywood in the 40s, I try to see continuities and changes in storytelling strategies. These make me appreciate how our filmmakers creatively rework conventions that have rich, surprising histories.

Parts of those histories are traced in the book that came out in the fall, Reinventing Hollywood. Some of my blog entries have already served to back up one point I tried to make there: that contemporary filmmakers are still relying on the storytelling techniques that crystallized in American studio films of the 1940s.

Relying on here means not only utilizing but also, sometimes, recasting. In keeping with earlier entries (including one from the year before last), I want to explore some films from 2017. These show that the process of schema and revision creates a tradition. Hollywood is constantly recycling, and sometimes revitalizing, Hollywood.

Of course here be spoilers.

Back to basics

The Big Sick.

The US films I’ll be considering all adhere to canons of classical Hollywood construction. Some of these are laid out in the third chapter of Reinventing.

Classically constructed films have goal-oriented protagonists who encounter obstacles, usually in the form of other characters. The goals are often double, involving both romantic fulfillment and achievement in some other sphere. (Somewhere Godard says that love and work are the only things that matter. Hollywood often thinks so too.) Alternatively, the goal might be prodding someone else to action (Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri). Often there’s a clash between the goals, as when work tugs the protagonist away from love (La La Land).

The plot is typically laid out in large-scale parts. A setup is followed by a complicating action that redefines character goals. In Downsizing, once Paul has gotten small, he has to reconceive his goals in the face of his wife’s last-minute defection from their plan. There follows a development section that delays goal achievement through characterization episodes, backstory, subplots, parallels, setbacks, digressions, twists, and new obstacles. That marvelous slab of show-biz schmaltz, The Greatest Showman, relies for its development on a potential love triangle and a secondary couple’s romantic intrigue.

There follows a deadline-driven climax that resolves the action and an epilogue (sometimes called the tag) that celebrates the stable state achieved and perhaps wraps up a motif or two. The Greatest Showman presents Barnum’s success in creating a genuine circus and reconciling with his family. The tag shows a big production number, with the subplot resolved (Carlyle embracing Anne) and the motif of swirling points of light—initiated in Barnum’s spinning Dreams gadget—washing over the final spectacle and his daughter’s ballet performance.

Classical narration—what’s usually called point of view—typically attaches us to the main characters. But not absolutely: we’re usually given access to things they don’t know, mostly for the sake of arousing curiosity and suspense. And throughout, the film is bound together through recurring motifs that reveal character (and character change) or significant plot information. Think of the roles Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 assigns to “Brandy, You’re a Fine Girl,” Pac-Man, David Hasselhoff, and that “unspoken thing.”

Or take The Big Sick, a semi-serious romantic comedy. Kumail’s initial goal is success in standup comedy, but he also falls in love with Emily. His Pakistani-American family constitutes the main antagonist, as his mother and father want him to go to law school and submit to an arranged marriage. He hasn’t told his family about Emily, which precipitates the couple’s big quarrel: “I can’t lose my family.” Kumail’s goal shifts when Emily is stricken by a mysterious disease. In the development section , as she lies in a coma, he gets to know her parents, and a tense sympathy develops between them. The crisis comes when Kumail confesses his true goals to his parents, they disown him, and Emily’s disease hits a life-threatening phase.

In the climax portion, Emily revives and breaks off with him, his parents grudgingly accept his move to New York, and he mounts a somewhat successful one-man show there. The film is tightly tied to Kumail’s range of knowledge, so we’re surprised when he is—as when Emily’s parents decide to move her to another hospital, and when Emily pops up in his New York audience, ready to reconcile with him.

The Big Sick exploits many comic motifs: the parade of would-be fiancées Kumail’s mother invites to dinner, the photos he keeps of them (which ignite Emily’s jealousy), the repeated sit-downs he has with his family, the dumb catchphrases deployed by other comics, and especially Emily’s “Woo-hoo!” heckling, which eventually attests to the rekindling of their love.

The power of classical plotting is shown in its ability to spotlight a Pakistani-American protagonist, an Islamic family demanding that a son adhere to tradition, and the pathos of parents facing the death of a daughter. But that ability to flexibly absorb new subjects and themes and emotional registers has kept the classical template going for about a century.

Time travel

Wonder Woman.

One of the hallmarks of Forties cinema, I argue in Reinventing’s second chapter, is a eagerness to explore what flashbacks can do. Flashbacks were already well-established, but a more pervasive acceptance of nonlinear storytelling, so familiar to us now, became firmly part of Hollywood sound cinema in this period.

One-off flashbacks are so common now we don’t particularly notice them. In The Big Sick, when Kumail visits Emily’s apartment with her parents, he peeks into her closet, and we get glimpses of her wearing the outfits earlier in the film. In this case, flashbacks function as memories. At the climax of Guardians 2, Quill flashes back to moments of listening to music with his mother. Similarly, in Get Out, Chris recalls his childhood TV viewing and, at the climax, he remembers earlier moments at the Armitage garden party when he asks, “Why black people?”

Flashbacks usually aren’t pure representations of memory, though. They often include information that the character doesn’t or couldn’t know. In fact many flashbacks are addressed simply to us, coming “from the film” rather than from a character’s mind. These may remind us of things already seen, or fill in gaps, or plant hints about things that will develop.

So, for instance, in Logan Lucky, when Logan says, “I know how to move the money,” we get a flashback to him studying the pneumatic pipes that feature in the heist plan.

He’s not necessarily recalling the moment; the filmic narration seems merely to be tipping us the wink. At the climax, other “external” flashbacks plug gaps we didn’t notice earlier. These reveal some aspects of the heist we weren’t aware of, such as the extra bags of money carried off.

1940s filmmakers also explored how flashbacks could be “architectonic,” how they could inform the overall shape of the movie. Here the flashback rearranges story order to build up curiosity and suspense, and it may come from purely from the narration or be motivated as character memory.

One large-scale pattern is the extensive embedded flashback, as in How Green Was My Valley, I Remember Mama, and innumerable biopics. Wonder Woman gives us a framed inset of this sort, when a modern-day Diana opens the chest harboring the World War I photo. That scene segues to the past. The origin story and war episodes are ultimately closed off by a return to the present, and a reminder of a motif—Steve’s watch (which, in one of the film’s jokes, stands in for something more private). The purpose of this is to provide what I call in the book “hindsight bias.” While building curiosity about the past, the opening primes us to expect certain things to have been inevitable (such as chance meetings).

Another common framing strategy begins at the climax and then a long flashback lays out the conditions that led up to it. A reliable source tells me that Pitch Perfect 3 does this, starting with an explosion followed by a title announcing that the action began three weeks earlier. In films like this, there may be no closing frame; the internal action of the flashback catches up, perhaps via a replay, with what we saw at the outset, and the film proceeds to the resolution and epilogue. The somewhat phantasmic opening number of The Greatest Showman comes to fruition during the finale.

To and fro

Loving Vincent.

Sustained blocks like this are fairly rare nowadays, I think. More common, as in the Forties, is an alternation of past and present. The main examples in Reinventing Hollywood include Passage to Marseille, The Locket, Lydia, Kitty Foyle, and Sorry, Wrong Number. Again, though, these are motivated as memories, while current examples tend to be more “objective.”

A simple instance is Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool. Here clusters of events in 1981 alternate with incidents in 1979: Gloria Grahame returns to her young lover, and we flash back to their earlier affair. Neither protagonist is firmly established as recalling the 1919 events. Another feature of 1940s flashbacks, the replay from different viewpoints, comes in here as well. The couple’s crucial quarrel in New York is shown first from Peter’s perspective, and later from Gloria’s. He suspects her of infidelity, but we learn that her secret involves her cancer. As often happens, our restriction to the protagonist is modified by knowledge he doesn’t gain at the moment.

The alternation of past and present is given a more geometrical neatness in Wonderstruck. In maniacally precise parallels, Rose in 1927 runs away to Manhattan to find her mother, while in 1977 Ben runs there to find his father.

The parallels are reinforced by a host of motifs: wolves, movie references, the asteroid in the Museum of Natural History, a bookmark, and so on. The linear chronology gets straightened out, and the gaps filled, by an integrative flashback played out among miniatures and cutouts adapted to the scale model of Manhattan. The dovetailing flashbacks create a sense of cosmic design; in many films, convergences like these can suggest destiny.

For modern audiences, Citizen Kane is the prototypical flashback film of the 1940s, and its investigation structure, while not completely original, was hugely influential. I was surprised to see Kane’s schema revived this year in Loving Vincent. Once the postman has given Armand his mission, to take Vincent’s last letter to brother Theo, we embark on an inquiry into Vincent’s life and death. It’s refracted through the testimony of many who knew him during his sojourn in Arles. Armand’s goal gets recast when he learns of Theo’s death, but in the course of his travels he comes to understand how Vincent’s kindness and art touched many lives.

As in several Forties films, Loving Vincent’s past scenes jumbled out of chronological order, so we must piece together the story Armand gradually discloses. And there’s the driving force of mystery, a distinctive thrust in many Forties genres, for reasons I talk about in one chapter of Reinventing. Very modern, and not so much like the 1940s, is the brief, fragmentary quality of the flashbacks; I counted thirty-six of them.

The boldest experiment in nonlinear time I saw this year was Dunkirk. The film juxtaposes timelines consuming a week or so, a day, and an hour, and then aligns them in unexpected ways. In this staggered array, the distinction between flashbacks and flashforwards loses its force. Any cut may constitute a jump ahead of the moment just shown, or a jump back to an earlier incident. Christopher Nolan has acknowledged the influence of 1940s cinema on his thinking about time schemes, and here he explores yet again how crosscutting different lines of action can stretch or condense story duration.

Their eyes and ears

Get Out.

Like flashbacks, subjectively tinted storytelling has a long cinematic lineage. Silent films displayed dreams, visions, anticipations, and deformations of mind and eye. Those devices mostly dropped out of 1930s American cinema, which was to some extent more “objective” and “theatrical” in its mode of presentation. Subjectivity came roaring back in the Forties, which is why Reinventing Hollywood devotes two chapters and several other passages to various techniques that go beneath the surface.

Memory-based flashbacks are common options today, but the inward plunge can take other forms. For most of its length, Get Out restricts us to Chris’s range of knowledge, and it relies on optical POV in many stretches. Through his eyes we see Mrs. Armitage staring at him while stirring the tea.

More complex is his view of Georgina at the upper window. That’s followed by a shot going beyond his range of knowledge: she’s looking not at him but herself.

We take a deeper dive into Chris’s mind under hypnosis. The boy Chris sinks into a stellar cavity and becomes Chris staring at Mrs. Armitage as if she were appearing on the TV screen. The shift dramatizes his guilt at his mother’s death and his susceptibility to this Bad Mom figure.

Once Chris becomes a prisoner, the narrational range widens again to show Rod’s efforts to rescue him, along with the family’s plans for him. But the film tightly realigns us with Chris at the climax, so that the attacks from Rose, Jeremy, and others come as surprises.

Chris, a photographer, channels his experience through vision, though the hypnotism scene blends sounds from the present with the rain drizzling in the past. Subjectivity goes more fully sonic in Baby Driver, about a whey-faced lad who lives in the auditory ether.

Edgar Wright, now exercising straight the percussive dashboard details he parodied in Hot Fuzz, punches up the visual exhilaration of Baby’s rubber-shredding takeoffs and getaway 180s. He locks us into Baby’s auditory world as well. We’re almost completely attached to Baby, learning what he learns when he learns it. Notably, the robberies are rendered from his perspective, including optical POV shots as he waits in the getaway car.

Again, fragmentary flashbacks replay his mother’s death and the childhood damage to his hearing. We even get a fantasy, with Baby imagining his escape with Debora in black and white.

What’s just as subjective, though, is the music Baby incessantly cues up on his iPod. Blocking out the shriek of his tinnitus, it provides a soundtrack to his life—danceable tunes as he bops down the street, ballads when he flirts and falls in love with Debora, and pulsing rock during robberies (what the psycho Bats calls, “a score for a score”). Through volume and texture, Wright suggests that we hear the music as Baby does; only the loudest environmental sounds poke through. Sometimes, when he pulls out one earbud, the volume drops. His growing attachment to Debora is signaled by his dialing up a song using her name and sharing his precious buds.

Some scenes are handled objectively, as we witness the gang’s conversations in front of Baby. He can read lips, though, and he can keep the iPod cranked up. So a little bit of Baby’s custom soundtrack leaks in for us underneath others’ dialogue. At other times, the score takes over to become nondiegetic accompaniment, as when gunshots in a firefight land on the off-beats of “Tequila.”

As you’d expect, the music comments on the action throughout (“Never ever gonna give you up” when Baby defends Debora from Buddy) and supplies motifs. Queen’s “Brighton Rock,” Baby’s favorite heist accompaniment, briefly enables him to bond with Buddy.

A song about a couple’s devotion reminds us that both thieves are loyal to their women.

Momentary sound changes are rendered through our protagonist’s viewpoint. Wright lets us hear the whine of Baby’s tinnitus as Bats taps his ear. When Buddy blasts his pistols alongside Baby’s head, we suffer his hearing loss and the distorted voices that wobble through it.

Such streams of auditory perception occasionally emerged in early talkies (e.g., Gance’s Beethoven). Those experiments got normalized in 1940s manipulations of sound perspective in different environments. More fancily, in A Double Life (1947), party chatter subsides when the hero covers his ears, and in Pickup (1951), the gradually deafening protagonist hears high-pitched noises. Wright extends these one-off devices to the texture of an entire film.

Confidants

The Keys of the Kingdom (1945).

Large-scale and small-scale, the heritage of the 1940s seems to be everywhere. Many of the flashbacks and fantasies I mentioned already are primed by a track-in to a character’s face, just as in classic studio pictures. There’s also block construction, either unsignaled as in the Wonder Woman and Greatest Showman cases, or signaled, as in the date-stamping in the early alternations of Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool. We also get explicit chaptering, as in The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected) and Norman: The Moderate Rise and Tragic Fall of a New York Fixer.

Voice-overs come along with flashbacks, as a way of guiding the audience to understand the time shifts. In the Forties, as I discuss in the book’s sixth chapter, voice-overs became more flexible and fluid. Sometimes they were external, issued from an all-knowing commentator (Naked City and other police procedurals). Sometimes they were sonic equivalents for letters and diaries, letting us in on what characters were writing. Deeper intimacy could come from voice-overs serving as inner monologues, the voice of a character’s mind. These, like flashbacks, are associated with film noir, but also like flashbacks they actually emerge in many genres–as they do today.

The voice-over can be perfunctory, as in All the Money in the World. Young Paul Getty, kidnapped in the opening reel, has a couple passages confiding in us, but he’s not heard from again. Moreover, his explanation of his grandfather’s rise to power (during the inevitable flashbacks) could have been supplied in other ways. Paul baldly tells us that we need to know all this to understand what follows (who’s he talking to?). He admits that he’s an expository shortcut. This is why voice-over is sometimes considered lazy storytelling.

It doesn’t have to be. Take Martin Scorsese’s Silence. In subject and strategy it reminded me of The Keys of the Kingdom (1945), which dramatizes the diary of a young missionary to China. Via this novelistic device, we get flashbacks to his youth and his years of service. We get as well the reaction of the skeptical priest whose voice reads the journal. This fairly straightforward schema is in effect revised by Scorsese and co-screenwriter Jay Cocks, who create a floating dialogue among voice-overs.

After initial exposition via an old letter from Father Ferreira, which is recited in his voice, two young priests set out for Japan. They hope to maintain the clandestine Christian community there, and they want as well to discover if Ferreira has truly renounced his faith . The bulk of their grim adventures is commented on through the voice-over of one of them, Father Sebastião Rodrigues. At first he’s vocalizing a letter, which he calls a report, summing up the struggles of the Jesuit mission and their encounters with Christian villagers. In the course of his report, we also get an embedded flashback narrated by Kichijiro, their guide and a sporadically lapsed believer himself.

But at a crucial moment, Father Sebastião’s report ceases to be such and turns into an inner monologue. Seeing a Christian village devastated by the shogun’s forces, he asks, “What have I done for Christ?”

Soon his voice presents a kind of stream of consciousness–praying for the villagers as they walk off in captivity, thanking God when he has a vision of Jesus on his prison wall. His inner voice urges his colleague Father Garupe, severely tortured, to apostatize.

In last stretch of the film, new voices are heard. There’s Jesus, perhaps filtered through Sebastião’s mind (subjectivity again), and then, more objectively, there’s an account from the Dutch trader Albrecht. He drily reports that Sebastião apostatized and followed Ferreira in leading a Japanese life. Albrecht’s narration is interrupted by a dialogue between Sebastião and Jesus, capped by the priest’s blurting out: “It was in the silence that I heard your voice.” Albrecht’s voice-over concludes the film, with his final claim that the priest was “lost to God” belied by the closing image.

From the 1940s onward, voice-over has been a rich resource–describing settings and external behavior, judging other characters’ motives, giving us access to the deepest thoughts of the speaker. I try to show these capacities at work in a fairly ordinary film, The Miniver Story, but for our time, the soundtrack of Silence is another vivid demo. In the juxtaposition of different voices, it achieves some of the density of a novel, and by the end we better understand the initial words and emotions of Father Ferreira, the priest whose apostasy launches the plot.

Passed-along voice-over gets a bigger workout in Dee Rees’s Mudbound. The original novel is somewhat like As I Lay Dying; its sections set various characters’ voices side by side, shifting viewpoint as each takes up a portion of the tale. Constant commentary and perfect alignment with a character’s range of knowledge are hard to sustain in cinema, so what we have onscreen are objectively presented scenes accompanied by an occasional voice-over. Still, it’s a rare option. If Silence gradually opens its voice-over horizons near the film’s end, Mudbound introduces polyphony from the start. Six characters share their thoughts and feelings in alternation, providing backstory and deepening our access to their reactions.

As in Silence, there’s a pattern to the voice-overs. The bulk of the film is an embedded flashback, triggered by the McAllen brothers setting out to bury their father and encountering the Jackson family riding by.

The intersection of two families sets up not only the flashback episodes but the floating voice-overs. As the visuals anchor us initially to the white family, the first voice-overs issue from Laura, the wife of Henry McAllen, and from Henry’s brother Jamie. In the flashback stretch, as America enters World War II, the voice-overs shift to the Jacksons, the father Hap and the mother Florence. The plot proceeds to add the voices of Henry and the Jacksons’ oldest son Ronsel. All the characters narrate the action in the past tense, as if recalling it from a distance in time, but no listener is ever specified–a common feature of voice-overs in the 1940s and afterward.

During the film’s second half, the development and climax sections, the voice-overs nearly vanish. For over an hour, we hear only Laura and Florence, and only once apiece. Jamie and Ronsel, both disaffected returning vets, don’t confide in us during their growing friendship or during the persecution of Ronsel by the local white men. The women are left to provide a sporadic chorus.

At the end, however, a spurt of brief commentaries give the men their inner voices back. We return to the present and see Hap Jackson help the McAllen men bury their father (the inciter of KKK violence against Ronsel). The epilogue features brief comments from Ronsel, Jamie, and Hap, and not the women. Ronsel gets the last word. Ironically, because of the KKK savagery, this narrator has become mute.

Again, I felt a current film’s kinship to those I studied for the book. Mudbound traces the rural home front, the military experiences of a white man and a black one, and the veterans’ problems of adjustment upon returning home. These elements hark back to some of the powerful films of the 1940s, including Home of the Brave and The Best Years of Our Lives. The sympathetic portrait of African-American families isn’t unprecedented either, as seen in Intruder in the Dust and Lost Boundaries. Mudbound‘s passed-along narration, like the ones we find in other modern films, constitute contemporary revisions of the shifting voice-overs we get in Citizen Kane and All About Eve.

Career women careening

Molly’s Game.

Molly’s Game and I, Tonya offer good wrapup examples of many of these strategies, with some unreliability thrown in.

As you’d expect in a film by Aaron Sorkin, the flashback organization of Molly’s Game is fairly complicated. Just as The Social Network intercut two arrays of flashbacks triggered by two legal inquiries, the new film scrambles together crucial moments in Molly’s childhood , scenes of her current legal troubles, and sequences showing her rise to become the Poker Princess, the arranger of high-stakes games. The film gains a bit of the structural symmetry of Wonder Woman by beginning and ending with a childhood defeat that Molly rises above.

The flashbacks are stitched together by Molly’s voice-over. A filmmaker who recruits a narrating voice has to choose. Do you show the narrating situation? Or do you leave it unspecified? In this last instance, the narration might be wholly internal, a mental summing up of events, or it might feel like a confidence shared with an intimate, even though we’re shown no listeners. In Molly’s Game, her bare-it-all confession might seem to be simply her unspoken thoughts, but at one point it’s suggested that what we’re getting is her book’s version of her life.

Molly’s attorney Charlie is reading her memoir while he researches her case, and he asks her about a passage we saw in a flashback: her boss chews her out for bringing him “poor people’s bagels.” The attorney suggests that nobody uses that phrase, and that probably the boss used a racial slur that she suppressed in the book. This throws a little bit into question the reliability of Molly’s flashback, while also hinting at something we learn later: she sanitized the book to spare the reputations of the high rollers she serviced.

I, Tonya takes another option. Again there are disordered flashbacks and bursts of subjectivity tied together by the voice track. Whereas Molly is the sole speaker in her film, though, Tonya shares the soundtrack with other characters, in the manner of Mudbound. But these commentaries aren’t private musings. They’re the self-justifying testimony of people talking to a documentary camera. (Even though these sequences are said to be occurring forty years after the earliest events, the format is an anachronistic 4:3–presumably to help us keep the time frames distinct.

Once you get characters in conflict recounting past events, you have the possibility of disparate stories. Forties filmmakers exploited this in Thru Different Eyes and a certain Hitchcock film too famous to mention. Tonya says explicitly that there are different versions of the truth. A brief scene shows her battering Nancy Kerrigan, and a more complicated one occurs in a tale recounted by her husband Jeff. She fires a shotgun at him and turns to the camera saying, “I never did this”–before briskly ejecting a shell.

The comic possibilities of to-camera address on display here were exploited in My Life with Caroline, Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House, and other 1940s films. Then the momentary breaking of the fourth wall was reserved for the frame story and kept separate from the embedded flashbacks. But I, Tonya‘s revision is easy to understand as a zany equivalent for her verbalized denial. Given the defiant way she brandishes the gun, we’re permitted to doubt her denial–which means that the film is refusing to settle the matter. The possibility that the overall filmic narration could be unreliable was rehearsed occasionally in the Forties, perhaps most vividly in Mildred Pierce (analyzed here, sampled here).

Other paths

Foxtrot.

The 1940s were important for other national cinemas too. The book’s last chapter suggests that filmmakers in Britain, France, Mexico, and other countries engaged in similar narrative explorations–sometimes in imitation of America, sometimes on their own. I go on to suggest that eventually non-Hollywood narrative models came to international attention, and still later those affected American cinema.

Italian Neorealism was a prime source of alternatives. A good example of its long-term impact, I think, is The Florida Project, which embraces a slice-of-life pattern. Once you’re committed to episodic plotting, you need to organize the incidents coherently. Sean Baker follows European and US indie precedent in tracing a rhythm of daily routines that change in sync with the characters’ relationships. So Halley’s quarrel with her friend Ashley means that Moonee can no longer claim leftover food from the diner, which helps push Halley toward prostitution, which leads to the intervention of child welfare authorities.

The drama arises less from crisply defined goals than from circumstances that alter life routines. In addition, like many Neorealist films and others in this vein afterward, the poignancy gets sharpened by the presence of children caught up in adults’ bad choices.

The Florida Project presents many actions elliptically, leaving us to infer what has happened offscreen. (I think, for instance, that it’s motel manager Bobby Hicks who contacts the authorities, but I don’t think it’s made explicit.) Moving to films made outside the US, Michael Haneke’s Happy End takes ellipsis even further.

Haneke uses the strategy of delayed and distributed exposition. He presents some apparently casual events at the outset, then gradually reveals what’s actually going on, all the while tracing out ultimate consequences. Instead of presenting a clear-cut chain of causes and effects, he asks us to fill in unspoken plans, offscreen actions, and hidden motives. Haneke has specialized in suggesting how vague forces can disturb rich, smug families and their shady schemes. His mystery-driven narrational tactics suit Happy End as well as Code inconnu and Caché.

I speculate in Reinventing Hollywood that the European art cinema’s story-based mysteries and narrational uncertainties owe something to 1940s American films. So too perhaps does the use of block construction, which emerged in overseas portmanteau films of the postwar era (e.g., Dead of Night, Le Plaisir, The Gold of Naples). Samuel Maoz’s Foxtrot is a striking example of block construction.

His Lebanon (2009) took POV restriction to a limit by confining its action to a military tank in the heat of battle. (This tactic has Forties precedents as well, as Lifeboat and Rope remind us.) Foxtrot operates differently. Broken into three parts, it looks at a single situation–a young soldier’s duties at a checkpoint–through shifts in time and viewpoint. The opening shot, at first enigmatic, gets specified in an epilogue that recasts all that went before. Maoz also incorporates monotonous routines into his plot, the better to throw a single shocking incident into relief.

So classical construction isn’t the only option available. But other choices have histories as well. As viewers we learn these alternative stoytelling traditions, and we use that knowledge to make sense of new examples. No less than the Hollywood model, these other formal strategies engage us through familiar pattern and unexpected novelty, schema and revision.

I don’t mean to obsess over this 1940s thing. Our current films owe debts to silent cinema and to other eras too. It’s just that I continue to be fascinated by finding repetitions and variants of storytelling strategies that got consolidated in the period I was studying. Denounce them as formulaic if you want, but I prefer to think that these and other recent films illustrate, in fine grain, the continuity and sometimes the vitality of a major cinematic tradition.

Maybe this is my hook to an entry for the start of 2019?

Many thanks to Michael Barker of Sony Pictures Classics for help on this entry.

On the four-part structure of classical films see Kristin’s 2008 entry and my essay “Anatomy of the Action Picture.” Today’s entry deploys the analytical categories trotted out at length in this essay and more briefly in this discussion of The Wolf of Wall Street.

Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2.

Oscar’s Siren song 3: A guest post by Jeff Smith

Moana (2016).

DB here:

Our colleague and Film Art collaborator Jeff Smith is an expert on film sound, particularly music. He’s contributed several items to our site over the years (for example, here and here and here). Today he’s back with his annual survey of Oscar’s musical categories. He offers in-depth analysis of how the films’ scores and songs enhance the movies’ impact.

As I’ve done in the last two years, I’m offering another preview of this year’s nominees in Oscar’s two music categories: Best Original Song and Best Original Score.

This year, La La Land’s Justin Hurwitz is nominated in both categories. He is poised to join a small group of composers who won awards in each. Leigh Harline and Ned Washington first accomplished the feat in 1941 for Pinocchio. A.R. Rahman was the most recent. He won Best Original Score for Slumdog Millionaire and Best Original Song for its Bollywood inspired closer, “Jai Ho.” Remarkably, Alan Menken was a two-fister four separate times. His eight Oscar wins came from four of Disney’s animated musicals: The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), and Pocahontas (1995). (And I’ll bet you’re humming “Under the Sea” or “A Whole New World” to yourself just now.)

Will Hurwitz join this august group of composers? Hard to say, but I suspect he will since I am picking against him in one of these two categories.