Archive for the 'Film technique: Music' Category

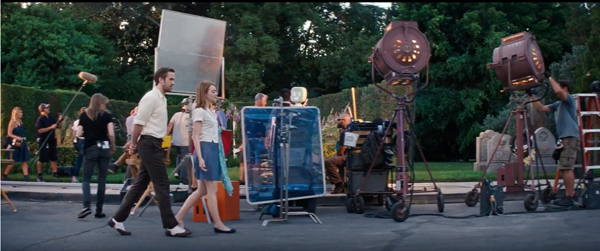

LA LA LAND: Singin’ in the sun

La La Land (2016).

DB here:

In our Film Studies program at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, one of our aims is to integrate critical analysis of movies with a study of film history. Sometimes that means researching how conditions in the film industry shape and are shaped by the creative choices made by filmmakers. We also study how filmmakers draw on artistic norms, old or recent, in making new films. This effort to put films into wider historical contexts is something that you don’t get in your usual movie review.

Take, yet again, La La Land. Awards and critical debates continue to swirl around the surprising success of this neo-musical. Two entries on this blog have already considered what the film owes to 1940s innovations in Hollywood storytelling (here) and to more basic norms of movie plot construction and the classic Broadway “song plot” (here). But there’s plenty more to say.

Enter three Madison researchers as guest bloggers. Kelley Conway is an authority on the French musical from the 1930s to the present and author of an excellent book on Agnès Varda (reviewed here). She also gave us an earlier entry on films at the Vancouver Film Festival. Today, in an oblique rebuttal to some complaints about the principals’ singing and dancing in La La Land, she situates Damien Chazelle’s film within a trend toward “unprofessional” musical performance.

Eric Dienstfrey studies developments in acoustic technology and how those have affected the way movies sound. In his contribution, he traces how film’s recording methods shape the auditory texture of the numbers, with special attention to the soft boundary between diegetic (story-world) sound and non-diegetic sound.

Amanda McQueen is a specialist in Hollywood and TV musicals of the last fifty years. Here she considers how La La Land is designed to overcome audiences’ current resistance to “integrated” musicals. She proposes that it offers one way to revive the genre for modern Hollywood.

These experts take the conversation in new directions I think you’ll enjoy. They remind us that a movie coming out today automatically becomes a part of history; it’s just that the history is sometimes hard to discern. Along the way they show the virtues of thinking beyond the talking points put out by the PR machine or circulating endlessly in reviews. In my view, good film criticism involves ideas and information as well as opinions, and all three are on vivid display here.

Amateurism as authenticity

Everyone Says I Love You (Woody Allen, 1998).

Kelley Conway: For me, La La Land‘s references to classical Hollywood musicals and to the films of Jacques Demy provide a major source of its pleasure. (Sara Preciado’s video essay demonstrates the film’s homages) The film’s nods to other traditions remind us of something about the relationship between Hollywood and other national cinemas: mutual influence is the norm.

Directors associated with the French New Wave absorbed and subverted Hollywood genres. Hollywood directors of the late 1960s and ‘70s, in turn, were inspired by the narrative ambiguity and stylistic playfulness of the New Wave. Sometimes, the influence travels full circle in quite a direct way. John Huston’s Asphalt Jungle (1950) directly influenced Jean-Pierre Melville in the making of Bob le flambeur (1956), while Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs references both Melville’s minimalist gangster films and Hollywood heist films.

La La Land demonstrates a similarly rich exchange between Hollywood and France. In 1967, Jacques Demy’s Demoiselles de Rochefort paid loving homage to Hollywood films such as Singin’ in the Rain, West Side Story, and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Chazelle’s film returns the favor, adopting the dancing pedestrians and location shooting of Demoiselles and the saturated colors, recitative, and downbeat ending of Parapluies de Cherbourg. Chazelle is equally smitten with classical Hollywood; La La Land brims with references to the choreography, costumes, and set design of Shall We Dance (1937), Singin’ in the Rain (1952), The Band Wagon (1953), West Side Story (1961), and many others.

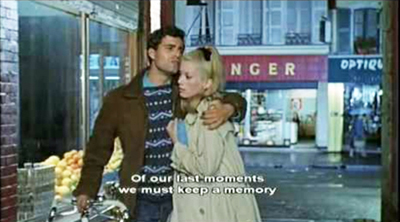

La La Land not only cites the style of other musicals, it also develops and tweaks narrative elements from older musicals in interesting ways. For example, Chazelle’s film, like Demy’s Parapluies de Cherbourg, thwarts the creation of the couple. In Parapluies, the Algerian war initially separates Guy (Nino Castelnuovo) and Geneviève (Catherine Deneuve).

Later, an unplanned pregnancy and her mother’s machinations push Geneviève to marry a wealthy jeweler. At the end of the film, when they run into one another at Guy’s gas station, they exchange only a few perfunctory words; Guy even declines Geneviève’s invitation to meet their daughter. There is neither anger nor the warmth of nostalgia in their exchange; just a delicately drawn emotional distance that leaves viewers feeling wistful.

In contrast, the relationship between Mia and Sebastian fails because they decide to put their romance on hold in order to pursue their dreams. “Where are we?” Mia asks Sebastian after her audition for the film role that will take her to Paris and launch her career. “We’ll just have to wait and see,” he replies. Five years later, he owns a jazz club and she has become an A-list actress, but she is married to someone else and has a child.

When they cross paths at his club, Chazelle supplements Demy’s delicate gas station meet-up with an exuberant fantasy montage, a kind of dream ballet often used in the classical Hollywood musical, in which the couple manages to stay together. The production number is full of invention and energy, combining animation, simulated home movie footage, a trumpet solo, and a tribute to the “Broadway Melody” number of Singin’ in the Rain. As Mia prepares to leave the club, she and Sebastian exchange tender glances and rueful smiles. She departs as he launches into his next song. The love is still there, the film suggests, but Sebastian and Mia chose art over love and they would probably make the same decision today. Different from Demy’s characters, Sebastian and Mia are not victims of implacable destiny, but committed artists. It’s an ending that feels fresh to me.

As Amanda McQueen reveals below, La La Land conforms to various trends in the 21st century musical. Consider just one element: song performance. Neither Ryan Gosling nor Emma Stone possesses a powerful, belt-it-out voice. Instead, much of the singing in La La Land is modest, thin, and breathy. Take, for example, the number “The Fools Who Dream,” a climactic moment in the film.

Asked by the casting director to tell a story, Mia begins a poignant monologue (“My aunt used to live in Paris…”) in a quiet speaking voice marked by a bit of vocal fry. She slowly moves into an a capella ballad and, after a few bars, is accompanied by piano. Eventually, the music swells, Mia goes big (“Here’s to the ones who dream…”), and then the song winds back down to the concluding notes, delivered a capella. The staging of the song – black background, circular camera movement, a big swell of emotion, a long take – is reminiscent of the splashy production number in Agnès Varda’s New Wave masterpiece Cléo de 5 à 7. But Stone’s voice reminds me of the wonderfully whispery, intimate singing voices of Birkin, Bardot, and Karina.

As Eric Dienstfrey points out below, the techniques used in the recording of the songs affect our impression of the story world and our sense of the film’s aesthetic achievement. In a Song Exploder podcast about the creation of this song, composer Justin Hurwitz emphasizes the difficulty of shooting this one-shot production number. He explains that Stone performed the song live on set, as opposed to lip-synching it. Hurwitz speaks of his struggle to keep up with Stone while accompanying her on set:

Because I was letting Emma lead the song, I was reacting to her. So a lot of times the piano is a little bit behind the vocal. It sounded like a recital or something where you know the singer is leading it and the piano is there to accompany. That’s what happens when two people make music together; things are not perfectly in sync. That’s why it feels musical and why it feels real and honest.

Directors of many recent film musicals similarly seek to create the impression of aural and emotional authenticity, either through non-professional singing or on-set recording. Woody Allen’s musical Everyone Says I Love You (1996) employs actors who are not professional singers, and Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge (2001) uses the relatively modest singing talent of Nicole Kidman and Ewan McGregor in a mixture of playback and live recording. Likewise, publicity for Les Misérables (2012) made much of the fact that Anne Hathaway, Hugh Jackman and Russell Crowe performed their songs on the set.

Christophe Honoré also tends to employ singing performances by non-singers. Here, in Dans Paris (2006), a couple breaks up over the phone while singing in a breathy, halting fashion.

For his musical Pas son genre (aka “Not My Type,” 2014), Belgian director Lucas Belvaux cast Emilie Dequenne (of Rosetta fame) as a karaoke-singing hairdresser who woos a philosophy professor. Belvaux insisted that Dequenne avoid taking lessons so as to preserve the imperfect quality of her singing voice. Here, Jennifer (Dequenne) and her pals rehearse the Supremes’ “You Can’t Hurry Love”:

There is, in fact, a broad spectrum of singings styles and capabilities used in contemporary film musicals. In La Captive (2000), Chantal Akerman employs an aria from Mozart’s Così fan tutte. Two women sing to one another flirtatiously from their windows across an apartment courtyard without accompaniment. One woman is a trained opera singer, while the other, the film’s elusive female protagonist (Sylvie Testud), is untutored. The contrast in the women’s voices provides an unexpected pleasure.

The use of the modest singing voice by Chazelle and others to convey emotion and authenticity is quite different, for example, from Alain Resnais’ use of song in On connaît la chanson (aka “Same Old Song,” 1997). Here, fragments of songs spanning the history of twentieth-century popular French chanson are lip-synched by actors. Like Dennis Potter, whose Singing Detective (1986) inspired On connaît la chanson, Resnais foregrounds the artificiality of dubbing. This creative choice works against the traditional commitment in film musicals (and in sound cinema more generally) to the impression of fidelity and authenticity. Here, Josephine Baker’s delicate singing voice is grafted onto the body of a Nazi commander. The humor in non-synchronization loops us right back to Singin’ in the Rain.

Directors of contemporary film musicals did not pioneer the use of the untrained singing voice. As Jeff Smith reminded me recently in an email, “There is a long tradition of celebrating the raw, unpolished singing styles of rock and rollers, dating back at least to the time of Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan and Roger Daltrey, and using those marks of authenticity as a means of distinguishing them from pop performers.” Unlike the musicians of rock and punk, though, Chazelle doesn’t seem particularly interested in denigrating pop music. He clearly loves John Legend’s musical performances in La La Land and those 1980s pop tunes he pretends to mock.

Many have criticized La La Land’s singing, but in fact, Chazelle is operating well within the tradition of employing imperfect vocalization to connote realism and to convey emotional power. The modest singing voices add another dimension to Chazelle’s participation in the ongoing conversation between Hollywood and French cinema.

La La canned vs. La La live

Eric Dienstfrey: I agree with Kelley’s observations about the remarkable number of cinematic references in La La Land. For example, the opening number, “Another Day of Sun,” embeds a host of influences within Chazelle’s mise-en-scène. For me, this exit-ramp romp immediately recalled the ferry ride in Jacques Demy’s Les Demoiselles de Rochefort and the traffic jam in Jean-Luc Godard’s Weekend. Amanda McQueen, below, notes how the scene reminded her of the films of Vincente Minnelli. And as Chazelle himself indicates, one might even see traces of Rouben Mamoulian’s Love Me Tonight and Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window.

Thanks to such references, we can consider the significance of La La Land’s numbers as extending well beyond Justin Hurwitz’s melodies and Benj Pasek’s and Justin Paul’s rhymes. The film’s allusion to Rear Window, for instance, may encourage audiences to compare the onscreen chemistry between Emma Stone and Ryan Gosling to that of Grace Kelly and James Stewart. To catch these subtle references, filmgoers need to pay close attention to the camerawork, the staging, the costumes, and even the choreography. Similarly, we can discover new layers of meaning by analyzing its songs and their sound designs.

How many ways are there for sound technicians to record and mix a musical number? Quite a few, it seems. One basic way is to record the vocal performances live on the set. During the earliest years of talking pictures, this technique often required the presence of an on-set orchestra to provide accompaniment from behind the camera. More recent strategies, however, merely ask singers to wear small earpieces that play pre-recorded accompaniment.

Another option is for technicians to record the vocal performances in an acoustically controlled studio and then mix these recordings into the final film. Sometimes technicians will record the studio performance before filming, and then require actors to lip-synch to playback on the set. Other times, technicians will ask the singers to perform the song live on the set, but then use a studio recording in the final mix due to unforeseen circumstances.

In some instances, the set might be too noisy to record a clean vocal performance, or the dance number might be so physically demanding that the actor can’t help but introduce heavy breathing and other vocalized efforts. A live recording may be ideal, but the studio recording is often the more practical solution.

The musical numbers in La La Land display both recording techniques. Some were recorded live—such as “Fools Who Dream,” which Kelley discusses above—and some were recorded in a separate studio—such as “Another Day of Sun.” Steven Morrow, the film’s sound mixer, suggests that each choice was informed by various practical concerns. The acoustics along the exit ramp, for instance, reportedly made it too difficult to record live singing.

Such concerns even led to strange incidents where a single song would contain a mixture of both live and studio recordings. Morrow notes how “Someone in a Crowd” relies upon Emma Stone’s live recordings, while studio recordings were used for the other actresses. This decision to blend together live and studio recordings can become a storytelling device—say, if the director wants to create a contrast between two or more characters—but for most songs, the choice to use either technique is generally determined by shooting conditions and budgetary considerations.

Still, can the acoustical differences between live and studio recordings function beyond practical filmmaking needs? It is worth noting that both techniques parallel another cinematic binary: diegetic sound and non-diegetic sound. Diegetic sound commonly refers to all the dialogue, effects, and music that emanate from sources within the film’s setting, such as radios and footsteps. Non-diegetic sounds are those added to the story world as a form of commentary, such as a moody orchestral score. As many film scholars rightfully argue (here and here), the diegetic/non-diegetic binary is not perfect, but for the vast majority of films the distinction remains a useful initial categorization for sound’s narrative functions.

Musicals are an exception. In his groundbreaking study of Hollywood musicals, theorist Rick Altman argues that the clean distinction between diegetic and non-diegetic sound breaks down during moments when characters burst into song. Specifically, the interaction between diegetic singing and non-diegetic musical accompaniment lifts characters out of the story world toward fantastic settings. Consider Elvis Presley’s performance of “I Can’t Help Falling in Love with You” from Blue Hawaii.

Presley begins the song while accompanied by a small on-screen music box. But during his performance something interesting happens: the sound of the music box fades into the background while the drums and guitars of a non-diegetic orchestra magically appear. For Altman, this audio substitution is critical to understanding how the musical genre operates:

We have slid away from a backyard barbecue in Hawaii to a realm beyond language, beyond space, beyond time. […] We have reached a ‘place’ of transcendence where time stands still, where contingent concerns are stripped away to reveal the essence of things.” (66)

In other words, this dissolve from the music box to the orchestra tells us that Elvis… well… has left the building. He has transcended the purely diegetic universe of the film’s story-world reality, and has temporarily entered a non-existent space that is supra-diegetic fantasy.

Altman’s observations apply to La La Land as much as they apply to Blue Hawaii. When Mia and Sebastian sing “A Lovely Night” while searching for their cars, the non-diegetic accompaniment fades in and the two characters interact with the music through song and dance. In turn, Mia and Sebastian transcend Los Angeles and enter a supra-diegetic universe. This diegetic boundary crossing is punctuated further by their stroll through Hollywood’s hills, a vantage point which allows Mia and Sebastian to literally look down upon the city as they chart this transcendence.

Yet La La Land is more than just a pastiche of earlier musical traditions. It also demonstrates how different recording techniques can be thematically integrated within the film’s narration. Here we might once again compare the playback of “Another Day of Sun” to the live recording of “Fools Who Dream.” Both numbers are similar in their reliance upon non-diegetic musical accompaniment, yet the production process creates contrasting narrative implications.

“Another Day of Sun” was recorded in a studio, and the acoustical details of this studio environment—namely frequency response, microphone placement, reverberation time, and overall cleanliness of the recording—are remarkably distinct from the those of an outdoor location. These subtle textural differences produce the sense that the performers’ voices have left the diegetic space of the freeway and traveled to an unseen studio for the song’s duration.

“Fools Who Dream” has the opposite effect. It was recorded live, and throughout the scene the acoustical details that shape Stone’s voice never really change. The sonic signature of the room remains audible in her vocals from the time she introduces herself to the casting directors, to the time she finishes singing. As a result, Mia does not transcend the story world; instead, the non-diegetic piano and orchestra seem to materialize inside the room.

These two examples demonstrate how alternative recording techniques offer filmmakers different ways for characters and accompaniment to interact. Studio recordings specifically lift the vocals up toward the space of the non-diegetic accompaniment, whereas live performances can pull traditional musical accompaniment down into the story world. Both techniques defy the norms of realism, yet their production differences render each vocal performance with unique narrative weight. And for La La Land—a musical about two artists who wish to become famous stars while simultaneously remaining pragmatic and down-to-earth—the ways Mia and Sebastian interact with musical accompaniment can reveal if and when the characters are grounded in reality or lost in fantasy.

As criticism surrounding contemporary musicals would suggest, Hollywood routinely favors live performances over other techniques. Live performances are not only valued for being more authentic, they are harder to record and, thus, a more prestigious cinematic accomplishment. This preference for live recordings, however, need not dictate how all musicals are made. A creative integration of both live and studio recordings can open up storytelling possibilities for the sound technicians and directors who wish to innovate within the musical genre.

Yes, I know: it seems unlikely that many filmmakers will play with these acoustical parameters in their movies. Nonetheless, La La Land’s sound design points to the possibility that at least a few musicals will create rewarding experiences not just for visually minded historians, but for audiophiles as well.

A musical without quotation marks

Amanda McQueen: Much of La La Land’s critical reception has focused on its relationship to film musicals of the past. As Kelley, Eric and David have all noted, much of the film’s meaning derives from its citation and revision of film and stage musical traditions. But what’s the status of La La Land as a musical in the 21st century? How does this shape the film’s approach to the genre’s conventions?

The early 2000s witnessed a minor revival of the Hollywood live-action musical, a genre that had been considered box office poison for several decades. But despite the renewed interest in musicals, producers worried that contemporary audiences no longer accepted one of its key conventions: the integrated number.

Integration commonly refers to those moments when characters spontaneously burst into song to express feelings or advance the plot, usually accompanied by sourceless music, as Eric points out above. Not all musicals have integrated numbers, but many critics and scholars assume that integrated musicals constitute the genre’s core. Audiences, however, were assumed to find this particular break with cinematic realism both antiquated and alienating. Moviegoers would suspend disbelief to accept lightsabers, superheroes, and wizards, but someone walking down the street and singing—no way!

Fear of the integrated number has caused many contemporary musical films and television shows to distance themselves from this convention. Some musicals ensure the song-and-dance numbers are otherwise motivated. In Chicago and Nine (2010), all the songs are figments of the characters’ imaginations, while Dreamgirls (2006) transformed the integrated numbers of the Broadway original into diegetic stage performances.

Other musicals, including Enchanted (2007), The Muppets (2011), Annie (2014), and Pitch Perfect 2 (2015) opt for comic reflexivity, using integrated numbers to comment on their very artifice. The campy medieval musical Galavant (ABC 2015-2016) is perhaps the epitome of this technique. The lyrics of the second season’s opening number, for instance, address the series’ unexpected renewal (“Give into the miracle that no one thought we’d get”); the excessive repetition of the theme song in the previous season (“It’s a new season so we won’t be reprising that tune”); and a perceived lack of motivation for musical performance (“There’s still no reason why we bust into song”). The four-minute ensemble song-and-dance concludes with Galavant (Joshua Sasse) commenting with satisfaction, “See, now that was a number!”

Over the years, concern over audience acceptance of the integrated musical seems to have abated, particularly for Broadway adaptations. But it hasn’t disappeared, as La La Land’s critical reception makes evident. Articles on the film have routinely stressed that musicals are “an extinct genre,” that “some moviegoers may, no doubt, feel a little tentative about the genre,” and that musicals are no guarantee at the box office. Manohla Dargis’ review in The New York Times, aptly titled “‘La La Land’ Makes Musicals Matter Again,” discusses this issue at some length. She explains how “For decades, the genre that helped Hollywood’s golden age glitter has sputtered,” reappearing only in Broadway adaptations or diluted (read, non-integrated) forms, and that as a result, “Musicals have been for kids, for knowing winks and nostalgia.”

What perhaps feels so novel about La La Land is its sincere approach to the “old fashioned” integrated musical form. As writer/director Damien Chazelle told Hollywood Reporter:

On the screen, there is this big gap right now that you have to cross to do a musical. At least an earnest musical, where you’re not immediately putting quotation marks on it.

With its opening number, “Another Day of Sun,” La La Land unabashedly announces that this is an integrated musical, and it never qualifies that position. There are no cheeky winks at the camera, no characters asking why they’re singing to each other, and most of the songs function as pure expressions of thoughts and feelings. Mia and Sebastian are real people in a modern city, who just happen to be singing and dancing and falling in love. For Chazelle, “Another Day of Sun” functions as “a warning sign to people in the audience. If people are not going to be comfortable with it, they’ll leave right away.” La La Land thus almost dares audiences to accept and celebrate this unrealistic cinematic convention, and for a 21st century musical, that’s a somewhat rare approach to take.

Yet La La Land has its own methods of rendering the integrated musical acceptable for contemporary audiences. First, there is its obvious nostalgia. La La Land’s visual style—35mm, CinemaScope, long takes and long-shots scaled to choreography—and its many allusions create a critical distance, an awareness that this type of cinema is a relic of another age. It’s not so much a throwback to studio-era musicals as it is a modern version of the auteurist musicals of 1970s New Hollywood (most of which were also resistant to the traditional integrated number). Indeed, La La Land has been compared to Martin Scorsese’s New York, New York (1977) or Francis Ford Coppola’s One From the Heart (1981).

I think it’s also akin to Ken Russell’s The Boy Friend (1971), which has a lighter tone and takes a similar approach to its citations. Russell updates Busby Berkeley’s kaleidoscopic stagings with color and widescreen, and Chazelle updates Vincente Minnelli’s sequence-shots with a Steadicam. Like The Artist (2011), which tutored modern viewers in the conventions of silent cinema, La La Land is an affectionate lesson in a mode of filmmaking that is not likely to return.

Then there’s the ending, in which Mia and Sebastian find success in their artistic pursuits, but only because they have parted romantically. As Kelley explains, La La Land owes its bittersweet ending to Jacques Demy’s Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). This gives the film a melancholy at odds with the studio era Hollywood musicals it so frequently references—films like An American in Paris (1951) and Singin’ in the Rain (1952), in which the couple lives happily ever after. By eschewing the union of its romantic couple, La La Land tempers the artifice of the integrated musical with a more realistic narrative, one that acknowledges that life does not always work out exactly the way we want. Such a conclusion is far more typical of American independent cinema than it is of the classical Hollywood musical.

Significantly, La La Land does give us a traditional happy ending, but through the device of the dream ballet. One of the most overtly stylized conventions of stage and screen musicals, dream ballets generally function to convey character subjectivity, and they allow for especially abstract mise-en-scène. La La Land tackles this generic trope with the same sincerity it displays in its handling of integrated numbers.

Set to a medley of the film’s musical themes, the sequence functions much like that in An American in Paris, arguably the most famous cinematic dream ballet. The sequence recaps the characters’ emotional journey and romantic relationship entirely through dance. Yet while the ballet in Paris shows a stylized version of what has actually occurred, La La Land’s presents an alternative reality where Sebastian and Mia stay together while also achieving their artistic goals. As Owen Gleiberman puts it in Variety, this “the very movie we would have been watching had ‘La La Land’ simply been the delectable old-fashioned musical we think, for an hour or so, it is.” In the end, though, the film affirms that Mia and Sebastian’s happily-ever-after is only a fantasy; when the dream ballet ends, the two part ways.

The first time I saw La La Land, I found myself daring Chazelle to subvert my expectations and use the dream ballet as a device to create a happy ending. Instead of concluding the fantasy sequence with a return to reality, I hoped the dream ballet would function to re-write the narrative. To my mind, turning the imagined world of the dream ballet into the characters’ actuality would have been an interesting twist on how this device usually functions. At the same time, it would have more radically embraced the integrated musical tropes the film otherwise celebrates.

Yet I suspect viewers would have found this ending contrived, and it would have been. La La Land’s critical and commercial success, I think, has depended on it keeping the model of the classical Hollywood integrated musical slightly at arm’s length. The film’s unique combination of nostalgia and realism is clearly resonating with modern audiences, but it’s also in keeping with the larger approach to the integrated musical in the contemporary moment. As long as film musicals are considered risky properties, certain forms of the genre will likely have to be relegated firmly to the past.

Kelley Conway is a Professor in our department and winner of a Distinguished Teaching Award. She has written Chanteuse in the City: The Realist Singer in 1930s French Film (University of California Press), Agnès Varda (University of Illinois Press), and essays on classical and contemporary French film. She is currently at work on a book about postwar French film culture.

Eric Dienstfrey is a doctoral candidate in our department. His dissertation traces how theories of acoustical fidelity shaped stereophonic technology from 1930 to 1959. Eric’s research interests include silent film musicians and the cultural history of dictaphones. He recently received the 2017 Katherine Singer Kovács Essay Award from the Society for Cinema and Media Studies.

Amanda McQueen, a Faculty Assistant in our department, finished her Ph.D. in 2016. Her dissertation is titled “After ‘The Golden Age’: An Industrial History of the Hollywood Musical, 1955-1975.” It examines how the breakup of the studio system helped create several musical cycles, each aimed at a niche audience, and each designed to prolong the genre’s viability in the new marketplace. Apart from studying musicals on stage, screen, and TV, Amanda’s interested in media industries, film technologies, and genre theory and history.

Thanks as well to Jeff Smith for his comments on these entries. Watch for his annual blog entry (first two, here and here) analyzing the Oscar-nominated songs and scores.

La La Land.

Friendly books, books by friends

Moses and Aaron (1974).

DB here:

When the stack of books by friends threatens to topple off my filing cabinet, I know it’s time to flag them for you. I can’t claim to have read every word in them, but (a) we know the authors are trustworthy and scintillating; (b) what I’ve read, I like; (c) the subjects hold immense interest. Then there’s (d): Many are suitable seasonal gifts for the cinephiles in your life (which can include you).

Happy birthday, SMPTE

Starting off in 1916 as the Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, this peerless record of American moving-image technology has gone through many changes of name and format. It’s now The SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. Its back issues have been a treasure house for scholars studying the history of movie technology, and it has outdone itself for its 100th Anniversary Issue, published in August.

Starting off in 1916 as the Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, this peerless record of American moving-image technology has gone through many changes of name and format. It’s now The SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. Its back issues have been a treasure house for scholars studying the history of movie technology, and it has outdone itself for its 100th Anniversary Issue, published in August.

It includes survey articles on the history of film formats, cameras and lenses, recording and storage, workflows, displays, archiving, multichannel sound, and television and video. There’s even an overview of closed-captioning. The issue costs $125 for non-SMPTE members, and it’s worth it. Many libraries subscribe to the journal as well.

A highlight is John Belton’s magisterial “The Last 100 Years of Motion Imaging,” which includes twenty-two pages of dense timelines of innovations in film, TV, and video. They stretch back beyond 1916, to 1904 and the transmission of images by telegraph. John’s article is provocative, suggesting that we might think of digital cinema as returning to film’s origins in handmade images for optical toys.

Lucas predicted that digital postproduction brought film closer to painting, and for more and more filmmakers that prediction is coming true. I was startled to learn that 80% of Gone Girl was digitally enhanced after shooting.

Yes, sir, that’s our BB

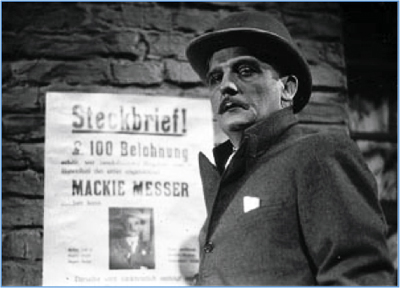

Die 3 Groschen-Oper (1931, G. W. Pabst).

During the 1970s, Bertolt Brecht’s name was everywhere in film studies. He epitomized what an alternative, oppositional, or subversive cinema ought to be. Cinema, even more powerfully than theatre, was a machine for producing illusions. So in his name critics objected to happy endings, plots that tidied up reality, characters with whom we ought to identify, messages that masked the real nature of bourgeois society. Films made all these things seem part of the natural order of things.

The Brechtian antidote was, as people used to say, to “remind people they were watching a film.” This was done by rejecting what he called the Aristotelian model and replacing it with the “alienation effect”: a panoply of distancing devices like intertitles, characters addressing the camera, actors confessing they were actors, and a display of the means of cinematic production (including shots of the camera shooting the scene).

The promise was that once viewers were banished from the imaginary world of the film they would exercise their intellects and coolly appraise not only the fiction machine but its ideological underpinnings. Godard was the chief cinematic surrogate for Brecht, and La Chinoise (1967) became the big prototype of Brechtian cinema—unless you preferred the more austere version incarnated in Straub/Huillet’s Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach (1967) and their adaptation of Othon (1969). The ideas spread fast, helped by the user-friendly Brechtianism of Tout va bien (1972).

The promise was that once viewers were banished from the imaginary world of the film they would exercise their intellects and coolly appraise not only the fiction machine but its ideological underpinnings. Godard was the chief cinematic surrogate for Brecht, and La Chinoise (1967) became the big prototype of Brechtian cinema—unless you preferred the more austere version incarnated in Straub/Huillet’s Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach (1967) and their adaptation of Othon (1969). The ideas spread fast, helped by the user-friendly Brechtianism of Tout va bien (1972).

Brecht became part of Theory. In French literary and theatrical culture of the 1950s, his ideas on staging and performance had claimed the attention of Roland Barthes and other Parisian intellectuals. Godard was alert to the trend early, it seems; he had fun in Contempt (Le mépris, 1963) citing the two BB’s (the other was Brigitte Bardot, bébé), and letting Lang quote a poem by his old collaborator and antagonist. By the time Anglo-American film theorists were ready for semiotics, Brecht was offering support. Didn’t his anti-illusionism chime well with the belief that all sign systems were arbitrary and culturally relative?

My summary is too simple, but then so were many borrowings. Soon enough any highly artificial cinematic presentation might be called “Brechtian,” though usually minus the politics. In the academic realm, Murray Smith’s book Engaging Characters (1995) pointed out crucial weaknesses in the anti-illusionist, anti-empathy account. By then, the certified techniques were becoming part of mainstream cinema. Thereafter, we had Tarantino’s section titles and plenty of movies breaking the fourth wall. Brecht might have enjoyed the irony of using the to-camera confessions of The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) bent to support cynical swindling. Isn’t The Big Short (2015) a sort of Hollywoodized lehrstück (“learning play”)?

Brecht’s writings should be read and studied by every humanist and certainly everybody interested in film. They’re clear, blunt, and often sarcastic.

This beloved “human interest” of theirs, this How (usually dignified by the word “eternal,” like some indelible dye) applied to the Othellos (my wife belongs to me!), the Hamlets (better sleep on it!), the Macbeths (I’m destined for higher things!), etc.

Now Marc Silberman, our colleague here at Madison, has completed a trio of books that make the master’s work available. Bertolt Brecht on Film and Radio includes essays, scripts, and the Threepenny Opera lawsuit brief. There’s also Brecht on Performance and a complete revision of that trusty black-and-yellow volume dear to many grad students: Brecht on Theatre. The latter two collections Marc worked on with collaborators. All are indispensible to a cinephile’s education. As Brecht imagined a bold political version of music he called misuc; can we imagine a cenima?

From BB to S/H

Speaking of Straub and Huillet, every decade or so somebody comes out with a book about them. This time we have to thank the admirable Ted Fendt, in the twenty-sixth volume in the series sponsored by the Austrian Film Museum (as well as the Goethe Institute and Synema). Like the Hou Hsiao-hsien volume (reviewed here), Jean-Marie Straub & Danièle Huillet is fat and full of ideas and information.

There are interviews, tributes from filmmakers (Gianvito, Farocki, Gorin), and Fendt’s account of distribution and reception of their films in the Anglophone world. This last includes charming facsimile correspondence, with one Huillet letter pockmarked by faulty typewritten o’s. As you’d expect, she is objecting to making a 16mm print of Moses and Aaron (1974) from the 35. (“No, definitively.”)

There are interviews, tributes from filmmakers (Gianvito, Farocki, Gorin), and Fendt’s account of distribution and reception of their films in the Anglophone world. This last includes charming facsimile correspondence, with one Huillet letter pockmarked by faulty typewritten o’s. As you’d expect, she is objecting to making a 16mm print of Moses and Aaron (1974) from the 35. (“No, definitively.”)

Starting things off is a lively and comprehensive survey of the duo’s careers by Claudia Pummer, with welcome emphasis on production circumstances and directorial strategies. The book wraps with a detailed thirty-page filmography and a substantial bibliography.

My thoughts about S/H are tied up with their earliest work, when I first learned of them. So I loved, and still love, Not Reconciled (1965) and The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach. I also have a fondness for Moses and Aaron, Class Relations (1983), From Today until Tomorrow (1996), and Sicilia! (1998). I find others out of my reach, and several others I haven’t yet seen. People I respect find all their work stimulating, so I suspect it’s really a matter of gaps in my taste.

Whether you like them or not, they’re of tremendous historical importance. Without them, Jim Jarmusch and Béla Tarr, and of course Pedro Costa and Lav Diaz, would not have accomplished what they have. And especially in December 2016, we ought to find their unyielding ferocity inspiring. Remember them on Dreyer: “Any society that would not let him make his Jesus film is not worth a frog’s fart.” Brecht would have approved.

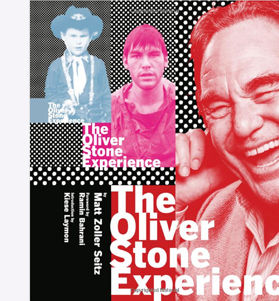

Stone’d

To the minimalism of Straub and Huillet we can counterpoint the maximalism of Oliver Stone, the most aggressive tabloid American director since Samuel Fuller (although Rococo-period Tony Scott gives him some competition). After two books on Wes Anderson, Matt Zoller Seitz has brought us a booklike slab as impossible as the man’s films. Can you pick it up? Just barely. Can you read it? Well, probably not on your lap; better have a table nearby. Does its design mirror the maniacal scattershot energy of films like JFK (1991), Natural Born Killers (1994), and U-Turn (1997)? Watch the title propel itself off the cover.

The Oliver Stone Experience is basically a long interview, sandwiched in among luxurious photos, script extracts, correspondence, and the sort of insider memorabilia that Matt has a genius for finding. We get not only pictures of Stone with family and friends, on the set, and relaxing; there are bubblegum cards from the 40s, collages of posters and filming notes, maps, footnotes, and shards of texts slicing in from every which way. Newspapers, ads, and production documents are scissored into the format, including a Bob Dole letter fundraising on the basis of the naughtiness of Natural Born Killers. Beautiful frame enlargements pay homage to the split-diopter framings of Born on the Fourth of July (1989) and the shadow of the 9/11 plane sliding up a facade in World Trade Center (2006). When Stone had second thoughts about things he’d said, Matt had the good idea of redacting the interview like a CIA file scoured with thick black lines.

The Oliver Stone Experience is basically a long interview, sandwiched in among luxurious photos, script extracts, correspondence, and the sort of insider memorabilia that Matt has a genius for finding. We get not only pictures of Stone with family and friends, on the set, and relaxing; there are bubblegum cards from the 40s, collages of posters and filming notes, maps, footnotes, and shards of texts slicing in from every which way. Newspapers, ads, and production documents are scissored into the format, including a Bob Dole letter fundraising on the basis of the naughtiness of Natural Born Killers. Beautiful frame enlargements pay homage to the split-diopter framings of Born on the Fourth of July (1989) and the shadow of the 9/11 plane sliding up a facade in World Trade Center (2006). When Stone had second thoughts about things he’d said, Matt had the good idea of redacting the interview like a CIA file scoured with thick black lines.

The whole thing comes at you in a headlong rush. Amid the pictorial churn and several essays by other deft hands, we plunge into and out of that stellar interview, mixing biography and filmmaking nuts-and-bolts. Matt gets deep into technical matters, such as Stone’s penchant for rough-hewn editing, as well as raising some big ideas about myth and autobiography. There are occasional quarrels between interviewer and interviewee. Out of the blue we get remarks like “Alexander was not only bisexual, he was trisexual,” which was not redacted.

The book’s very excess helps make the case for Stone’s idiosyncratic vision. Matt’s connecting essays, along with the vast visual archive he’s scavenged and mashed up, made me want to rethink my attitude toward this overweening, sometimes crass, sometimes inspired filmmaker. He now seems a quintessential 80s-90s figure, as much a part of the era as Reagan, Bush, and Clinton. Stone emerges as a resourceful defender of The Oliver Stone Experience, articulating a radical political critique with gonzo verve.

Rhapsody in white

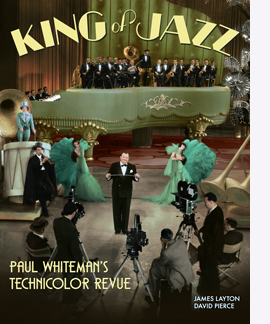

If lifting the Book of Stone doesn’t suffice for exercise, try another weighty and sumptuous item, King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman’s Technicolor Revue, by James Layton and David Pierce. Last spring the Museum of Modern Art premiered one of the most ravishing restorations I’ve ever seen, a digital version of King of Jazz (1930).

If lifting the Book of Stone doesn’t suffice for exercise, try another weighty and sumptuous item, King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman’s Technicolor Revue, by James Layton and David Pierce. Last spring the Museum of Modern Art premiered one of the most ravishing restorations I’ve ever seen, a digital version of King of Jazz (1930).

This period piece is in its own way as wild as an Oliver Stone movie. From its opening cartoon of Paul himself as a Great White Hunter bagging a lion, it’s a virtually self-parodying account of how a black musical tradition got netted, trussed up, and caged for the swaying delectation of white audiences. (No need to mention the irony of the name of our King.)

Along the way we have some straight-up songs (including some by Bing Crosby) spread among extravagant dance numbers. The Universal crane gets a workout as well. The music is infectious, the performers sweating to please, and the restoration–coming, I hope, to your screen soon–finally shows what two-color Technicolor could do. This is the definitive version of a film too often known in cut versions with shabby visuals and sound.

The book is an in-depth contextualization of the film, the studio, and the tradition of musical revues, both on stage and in film. It records the production and reception, with rich documentation throughout. The story of assembling the restoration is there too, and it’s a saga in itself. David is one of the moving spirits behind the online Media History Digital Library and its gateway Lantern. James is Manager of the Celeste Bartos Film Preservation Center at the Museum of Modern Art. Their collaboration has given us both a lush picture book and a serious, always enjoyable piece of scholarship. Their book proves the value of crowdsourcing: funded by online subscription, it was self-published. In this and much else, it can be a model for film historians pursuing questions that commercial and university presses might find too specialized. The result is a model of ambitious research, writing, and publishing.

Visiting Radio Ranch

Gene Autry in The Phantom Empire (1935).

For about thirty years I’ve been arguing that one fruitful research program in film studies involves what I call a poetics of cinema: the study of how, under particular historical conditions, films are made to achieve certain effects. This program coaxes the researcher to analyze form and style, study changing norms of production and reception, and consider how filmmakers work in their institutions and creative communities, with special focus on craft routines, work methods, and tacit theories about the ways to make a movie.

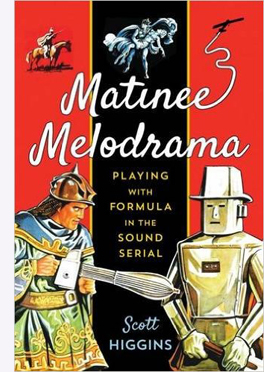

A sturdy example of this approach has appeared from Scott Higgins. His Matinee Melodrama fulfills the promise of its subtitle: Playing with Formula in the Sound Serial. Scott has closely examined this widely despised genre, plunging into the 200 “chapterplays” produced in America between 1930 and 1956. They offer bald and bold display of the rudiments of action-based storytelling: “If Hitchcock built cathedrals of suspense from fine brickwork of intersecting subjectivities and formal manipulations, sound serials used Tinkertoys.”

A sturdy example of this approach has appeared from Scott Higgins. His Matinee Melodrama fulfills the promise of its subtitle: Playing with Formula in the Sound Serial. Scott has closely examined this widely despised genre, plunging into the 200 “chapterplays” produced in America between 1930 and 1956. They offer bald and bold display of the rudiments of action-based storytelling: “If Hitchcock built cathedrals of suspense from fine brickwork of intersecting subjectivities and formal manipulations, sound serials used Tinkertoys.”

Scott traces production practices and conventions, focusing in particular on two dimensions. First, to a surprising degree, serials rely on the conventions of classic stage melodrama, such as coincidence and more or less gratuitous spectacle. Second, the serials are playful, even knowing. Like video games, they invite viewers to imagine preposterous narrative possibilities, not only in the imagination but also on the playground, where kids could mimic what they saw Flash Gordon or Gene Autry do.

Matinee Melodrama investigates the implications of these dimensions for narrative architecture, visual style, and the film and television of our day. Scott closes with analysis of the James Bond series, the self-conscious mimicking of serial conventions in the Indiana Jones blockbusters, and the Bourne saga, and he shows how they amp up the older conventions. “Like the contemporary action film generally, the Bourne movies participate in a cinematic practice vigorously constituted by studio-era serials. That is, they blend melodrama with forceful articulations of physical procedure in scenes of pursuit, entrapment and confrontation.”

Poetics, frank or stealthy

The Red Detachment of Women (1971).

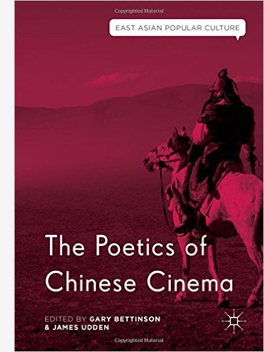

Scott’s book acknowledges the poetics research program, and so, even more explicitly, does a new collection edited by Gary Bettinson and James Udden. The Poetics of Chinese Cinema gathers several essays that usefully test and stretch that frame of reference.

One standard challenge to the poetics approach is: How do you handle social, cultural, and political factors that impinge on film? I think the best way to answer this is to treat these factors as causal influences on a film’s production and reception. More specifically, in the production process, what we now call memes function as materials—subjects, themes, stereotypes, and common ideas circulating in the culture or the filmmaking institution. In the reception process, they provide conceptual structures that viewers can use in making their own sense of the films that they’re given. And such materials will necessarily include other art forms; films are constantly adapting and borrowing from literature, drama, and other media.

Both of these possibilities are vigorously explored in several essays in The Poetics of Chinese Cinema. For instance, Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh traces how Taiwanese and Japanese cultural materials are reworked by Hou Hsiao-hsien in his Ozu homage Café Lumière (2003). Peter Rist, a long-time student of Chinese painting, shows how Chen Kaige deploys cinematic means to revise landscape traditions to create a “Contemplative Modernism.” Victor Fan shows how the Hong Kong classic In the Face of Demolition (1960) adapts and revises a mode of narration already established in Cantonese theatre. In a clever piece called “Can Poetics Break Bricks?” Song Hwee Lim considers how digital technology feeds into a poetics of spectacle, specifically around slow-motion techniques that were emerging in pre-digital filmmaking.

Both of these possibilities are vigorously explored in several essays in The Poetics of Chinese Cinema. For instance, Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh traces how Taiwanese and Japanese cultural materials are reworked by Hou Hsiao-hsien in his Ozu homage Café Lumière (2003). Peter Rist, a long-time student of Chinese painting, shows how Chen Kaige deploys cinematic means to revise landscape traditions to create a “Contemplative Modernism.” Victor Fan shows how the Hong Kong classic In the Face of Demolition (1960) adapts and revises a mode of narration already established in Cantonese theatre. In a clever piece called “Can Poetics Break Bricks?” Song Hwee Lim considers how digital technology feeds into a poetics of spectacle, specifically around slow-motion techniques that were emerging in pre-digital filmmaking.

Tradition is a key concept in poetics, and the editors explore important ones in their own contributions. Gary Bettinson studies the emergence of Hong Kong puzzle films in works like Mad Detective (2007) and Wu Xia (2011). Are they simple imitation of Hollywood, or are they doing something different? Gary shows them to have complicated ties to local traditions of storytelling. Jim Udden focuses more on stylistics in his account of Fei Mu’s 1948 classic Spring in a Small Town, remade by Tian Zhuangzhuang in 2002. By examining staging, cutting, and voice-over, Jim shows that the earlier film is in many ways more “modern” than it’s usually thought and is somewhat more experimental than the remake.

It might seem that the “model” operas and plays of the Cultural Revolution, epitomized in The Red Detachment of Women (1971) would resist an aesthetic analysis; they’re determined, top-down fashion, by strict canons of political messaging. But Chris Berry’s contribution shows that they’re amenable to close analysis too. Like Soviet Socialist Realism, they may be programmatic in meaning, but not in every choice about framing, performance, cutting, and music. Indeed, the fact that people both inside and outside China (me included) still find them pleasurable probably owes something to their “Red Poetics.” And in true Hong Kong fashion, many filmmakers in that territory plundered those soundtracks with shameless, drop-the-needle panache.

I should probably add that I have an essay in this collection too. It’s called “Five Lessons from Stealth Poetics,” and it surveys things I’ve learned from studying cinema of the “three Chinas”: Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the Mainland. What attracted me were the films themselves, but in exploring them I was obliged to nuance and stretch the poetics approach. Readers of this blog know the trick: in talking about particular movies, I also try to show the virtues of the approach I favor. In other words, stealth poetics.

This is a good moment to pay tribute to Alexander Horwath, moving into his final nine or so months of directing the Austrian Film Museum. He has been a major figure in European film culture, through his inspired programming and leadership in publishing the books and DVDs issued by the Museum. We’re very grateful for all he has done for us and for film historians around the world.

P.S. 11 December 2016: Thanks to Mike Grost for a title correction and John Belton for a name correction!

King of Jazz (1930).

Spies face the music: Jeff Smith on FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT

DB here: Here’s another guest contribution from colleague, Film Art collaborator, and pal Jeff Smith. He inaugurates a series of entries tied to our monthly Observations on Film Art videos on FilmStruck.

About a month ago, a new streaming service for film lovers debuted. Its name is FilmStruck and it’s a joint venture of Turner Classic Movies and the Criterion Collection.

As regular readers of the blog already know, David, Kristin, and I have launched a series for FilmStruck. Every month, we’ll be featured in short videos that offer appreciations of particular films and filmmakers. In baseball lingo, I got the leadoff spot. As the first up, I offered an overview of the principal musical motifs in Alfred Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent. Below is a supplement to the video that goes into a little more depth regarding the way Alfred Newman’s score for Foreign Correspondent fits into the film’s larger narrative strategies.

Fair warning: there are some spoilers in what follows. Some of you who are FilmStruck subscribers or owners of the Criterion disc may want to watch this Hitchcock classic before proceeding.

Founding a Hollywood dynasty

Alfred Newman.

If you were looking for someone whose work epitomized the qualities of the classical Hollywood score, Alfred Newman would be a pretty good candidate for the job.

Newman’s career in Hollywood began when Tin Pan Alley stalwart, Irving Berlin, recommended him for the 1930 musical, Reaching for the Moon. Having worked for years as a music director on Broadway, Newman planned to stay for only three months. But the lure of the Silver Screen was too strong. Newman spent the next forty years working in Hollywood.

In 1931, Newman became the musical director at United Artists, working mostly for producer Samuel Goldwyn. He also established himself as one of the industry’s leading composers, contributing to nearly ninety films over the course of the 1930s and earning nine Oscar nominations in the process. Newman’s most memorable early scores included such titles as The Prisoner of Zenda, The Hurricane, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and Wuthering Heights. Eventually, he would leave Goldwyn to take over the music department at 20th Century-Fox, a position he held for more than twenty years.

Alfred, however, would be just one of several Newmans who would make the name synonymous with the Hollywood sound. Alfred would establish a film composing dynasty that would come to include his brothers Lionel and Emil; his sons, Thomas and David; and his nephew, Randy.

Overture, hit the lights….

If you asked most film music aficionados for their favorite Alfred Newman scores, I suspect Foreign Correspondent would be pretty low on the list. Most fans of the composer’s work would likely opt for one of the later Fox classics he scored, such as How Green Was My Valley (1941), A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1945), The Captain from Castile (1947), or The Robe (1953). Yet, if you want to get a handle on the basic features of the classical paradigm, Foreign Correspondent’s typicality makes it more useful as an exemplar. Newman’s music neatly illustrates several of the traits commonly associated with the classical Hollywood score’s dramatic functions.

One of these characteristic traits is Newman’s use of leitmotif as an organizational principle. Foreign Correspondent’s score is organized around five in all. The first is a theme for the film’s protagonist, Johnny Jones. The second is a theme for Carol, Johnny’s love interest in the film. As is typical of studio-era scores, both themes are introduced in the film’s Main Title.

Like an overture, the Main Title previews the two most important musical themes in the film. The A theme is upbeat, sprightly, and lightly comic. It captures some of Johnny’s ebullience and masculine charm, and it helps establish the tone of the early scenes, which draw upon the conventions of the newspaper film. The B theme is slower and more lyrical. It features the kind of lush orchestrations for strings that became a hallmark of Newman’s style.

Each theme roughly correlates with the dual plot structure common to classical Hollywood narratives. The A theme previews the main plotline focused on Johnny’s efforts as an investigative reporter. The B theme previews the story’s secondary plotline: the budding romance between Johnny and Carol.

Both themes recur throughout the remainder of the movie. In fact, Johnny’s theme returns even before the opening credits have ended, appearing underneath a title card valorizing the power of the press. In contrast to the lively, spunky version heard earlier, Newman gives it a maestoso treatment, slowing the tempo and orchestrating it for brass. In this instance, Newman’s arrangement of Johnny’s theme is attuned less to the brashness of his character and more to the social role that newspaper reporters play as a source of information to the world.

Up until this point, the music simply primes us for what is to come. Johnny’s theme returns about two minutes later when he is first introduced.

The reprise of his theme makes explicit the Main Title’s tacit association between music and character. Here, though, it plays in a jazz arrangement as a slow foxtrot. Newman’s arrangement nicely captures the tone of these early scenes, which display the lightness and pacing of other newspaper comedies.

It returns 22 more times in the film. In all, Johnny’s theme accounts for more than a quarter of the film’s 94 music cues. Usually, the theme functions to underline Johnny’s heroism and resourcefulness as in the scene where he gives chase to Van Meer’s assassin. At one point, Johnny even whistles his theme. This occurs in the scene where he eludes a pair of suspicious men posing as police by pretending to draw a bath and crawling out the window.

In contrast, Carol’s theme is used less frequently, appearing in about thirteen cues in all. After its introduction in the main title, it returns when Johnny and Carol first meet at the luncheon sponsored by the Universal Peace Party. Johnny unknowingly insults Carol, first by mistaking her for a publicist, and then by expressing skepticism about the organization’s mission, griping about well-meaning amateurs interfering in international affairs. Newman’s theme hints at Carol’s attraction to Johnny despite his obvious boorishness. The music says what the characters can’t or won’t say. As Johnny and Carol trade insults, Carol’s theme captures the romantic spark that lurks beneath their badinage.

The theme’s other uses often work along similar lines, providing an emotional resonance to the couple’s expression of feelings for one another. A good example is found in the scene where Carol and Johnny huddle together on the deck of a steamship. Here, as a pair of refugees, each member of the couple declare their love for one another and their desire to marry.

Music for the hope of the world

In addition to these two principal themes, the score also utilizes three other themes and motifs to represent important secondary characters. A theme for Professor Van Meer is introduced when Johnny spots him getting into a taxicab.

It returns nine more times in the film in scenes that feature the character or make reference to him.

The theme itself is simple, slow, stately, and quite frankly, a little bit boring. Indeed, if it wasn’t for the multiple references to a “Van Meer Theme” on the cue sheet for Foreign Correspondent, the music would simply blend into the other material that surrounds it.

The orchestration of the theme for solo wind instruments, usually an oboe, gives it a kind of pastoral feeling. The image of peaceful shepherds is likely an appropriate one for Van Meer, who functions as a stand-in for a global desire to avoid armed conflict. Yet, both the character and Newman’s musical theme for him seem nondescript, making Van Meer seem like little more than the walking embodiment of an abstract ideal of world harmony.

Truth be told, Van Meer mostly operates in Foreign Correspondent as the classic Hitchcock MacGuffin–that is, the thing the characters all want, but with which the audience need not concern itself. When Van Meer appears to be assassinated, it sets in motion a chain of events that uncovers a conspiracy organized through Steven Fisher’s World Peace Party. Van Meer is the object that all the characters want to find, and the search for him drives the narrative forward. Yet the character himself has about as much personality as the microfilm in North by Northwest. Newman’s nondescript melody seems to fit the “blank slate” quality of Van Meer himself.

Like the classic MacGuffin, Van Meer’s function as something of an empty vessel allows his theme to be used several times late in the film in scenes where the character isn’t physically present. Although the norm is to use characters’ themes or leitmotifs when they are onscreen, Newman’s treatment of Van Meer shows they can evoke absent characters. This occurs, for example, in a scene where Scott ffolliot explains to Stephen Fisher that he’s arranged for the kidnapping of Carol. Fisher asks ffolliot why he would do such a thing, and ffolliot replies that he wants to know where Stephen has stashed Van Meer.

As we’ll see, Fisher has a theme of his own that itself appears several times in this same scene. But the use of Van Meer’s theme in this context becomes a way of signifying both the character and the peaceful values that he represents – that is, values that Fisher seeks to destroy.

And though Van Meer’s music is a bit dull, the theme proves a bit more interesting when one considers the way it works within Hitchcock’s larger strategies of narration. At a key point, Hitchcock and Newman use the Van Meer theme to mislead the audience about what has just transpired onscreen. I’m referring here to the moment when Van Meer appears on the steps just as the Peace conference in Amsterdam is about to commence.

The theme is cued by Johnny’s glance offscreen after briefly chatting with Fisher, his publicist, and a diplomat. Hitchcock cuts to a shot from Johnny’s optical POV that shows Van Meer climbing up the staircase. We return to Johnny, who smiles and walks out of the frame. Johnny and Van Meer meet in a two-shot where the former offers a warm greeting. A cut to Van Meer’s reaction, though, reveals a blank stare, even as Johnny tries to remind the elderly professor of their previous encounter in the taxi.

The moment is an important one, but before the viewer can even grasp its significance, the two men are interrupted by a request for a photograph. Hitchcock then tracks in on the newsman, who surreptitiously sneaks a gun next to the camera he is holding. He pulls the trigger, and Hitchcock cuts to a brief insert of Van Meer, who has been shot in the face.

As I noted earlier, the assassination we witness is a key turning point in the story, and Hitchcock handles the scene with considerable finesse. Almost unnoticed, though, is the fact that Hitchcock and Newman cleverly use Van Meer’s musical theme as a form of narrative deceit. At first blush, the musical theme helps to reinforce Van Meer’s identity, serving the kind of signposting function that some film music critics believed was a hackneyed device. As we later learn, though, the murder victim is not Van Meer, but rather a double killed in his place to foment international tensions. This information ultimately recasts the old man’s seeming failure to recognize Johnny. As Van Meer’s double, these two men have never actually met.

Has Hitchcock played fair in using Van Meer’s theme for a character that is not Van Meer but only looks like him? Perhaps, but the creation of this red herring is justified if one considers the fact that composers frequently write cues meant to reflect or convey a character’s point of view. Every composer must make a choice about whether to write a cue from the particular perspective of the character or the more global perspective of the film’s narration. Newman might have opted for conventional musical devices that connote suspense (ostinato figures, string tremolos, low sustained minor chords), and these would have signaled to the viewer that Van Meer is in peril, thereby creating a heightened anticipation of the violence that erupts in the scene. Instead, though, following the visual cues provided by Hitchcock’s cinematography and editing of the scene, Newman plays Johnny’s perspective and his recognition of Van Meer as he approaches the building’s entrance. By combining two common tactics–leitmotif and character perspective – Newman and Hitchcock briefly mislead the audience in order to create two surprises: the first when it appears that Van Meer is killed and the second when Van Meer is discovered inside the windmill and proves to be very much alive.

Menace (without the Dennis)

There is also a brief six-note motif used to signify the conspirators as a group. Labeled the “menace” motif, it is introduced just after Van Meer’s apparent assassination. In the chase that follows, Newman alternates between the “menace” motif and Johnny’s theme in order to sharpen the conflict and to capture the ebbs and flows of our hero’s dogged pursuit of the bad guys.

The motif returns, though, at just about any point where one of the group’s henchmen gets up to no good. In the scene inside the windmill, the menace motif appears several times to underscore the kidnappers’ nefarious scheme. Johnny sneaks inside the windmill, and after locating Van Meer, he tries to rescue him only to find out that the elderly professor has been drugged. As Johnny tries to figure out his next move, muted trumpets play the “menace” motif, signaling the kidnappers’ approach and thereby heightening the scene’s suspenseful tone.

Here again, Newman’s thematic organization reinforces a larger narrative tactic in Hitchcock’s film. Herbert Marshall serves as the typical suave villain commonly found in the Master’s oeuvre and Edmund Gwenn steals the show as Johnny’s would-be assassin, Rowley. But the rest of the conspirators are a largely undistinguished lot, and the use of a single motif for the group in toto reflects their relative impersonality. Unlike North by Northwest, where Martin Landau makes a vivid impression as Van Damm’s reptilian assistant Leonard, this spy ring seems to be filled out by thugs from Central Casting.

Father, leader, traitor, spy

Besides motifs for Johnny, Carol, Van Meer and the conspirators, there is also a short motif for Carol’s father, Stephen Fisher. It is harmonically and melodically ambiguous, structured around the rapid, downward movement of a chromatic figure.

In classical Hollywood practice, a leitmotif is usually introduced when the character first appears onscreen. But in an unusual gesture, Newman and Hitchcock resist this convention. The motif does not appear until more than eighty minutes into the film in the aforementioned scene just before ffolliot tries to blackmail Fisher into divulging Van Meer’s location.

By withholding Fisher’s motif, Hitchcock and Newman avoid tipping their hand too early. Since Fisher is later revealed to be the leader of the spy ring, the score circumspectly avoids comment on him in order to preserve the plot twist.

Several cues featuring Fisher’s motif return in the scene where Johnny, Carol, ffolliot, and the other survivors of the plane crash cling to wreckage waiting to be rescued. Carol spots the plane’s pilot stranded on its tail.

He swims over to the group and clambers about the wing. The pilot’s added weight threatens to upend the wing, thereby endangering everyone sitting atop it.

Recognizing this, the pilot asks the others to let him go so that he can simply “slip away.” Fisher overhears this exchange and decides to remove his life jacket and dive into the waters himself, leaving room on the plane’s wing for the rest of crash’s survivors.

The harmonic and melodic ambiguity of Fisher’s motif is most pronounced here, a moment where the character’s duality is also most clearly revealed. Is this a heroic act of self-sacrifice, an act of atonement for the damage Fisher has done to both his daughter’s reputation and his organization’s peaceful cause? Or has Fisher taken the coward’s way out, committing suicide in order to avoid facing the consequences of his actions?

Newman’s rather opaque musical motif doesn’t seem to take sides on this question, leaving Fisher’s motivation more or less uncertain. But this, too, is in keeping with the basic split between the character’s public and private personae. Introduced earlier as Carol’s father, Fisher appears to be cultured and debonair. Yet, when he seeks to extract information from a reluctant captive, Stephen resorts to the physical torments used by two-bit gangsters to make mugs talk. Like those gangsters in the 1930s, Fisher refuses to be taken alive and is swallowed up in briny sea. Still, his action does help to save other lives, and in this way, Fisher enables Carol to find a small measure of grace in the final memory she will have of him.

Putting earworms inside actual ears

As the principal composer of music for Foreign Correspondent, Newman had a major impact on the film’s ultimate success. Yet Newman was not responsible for the music that has engendered the most attention in critical work on the film. I’m referring here to two source cues written by Fox staff arranger, Gene Rose, that are featured in the scene where Van Meer is psychologically tortured. His captors use sleep deprivation techniques to elicit van Meer’s cooperation, including bright lights and the repeated playing of a jazz record. The two cues received rather cheeky descriptions on the cue sheet for Foreign Correspondent: “More Torture in C” and “Torture in A Flat.”

The use of jazz for these cues is likely a little bit of wicked humor on Hitchcock’s part. Despite its popularity as dance music in the 1930s, some listeners undoubtedly believed that jazz was little more than noise with a swinging rhythm. From a modern perspective, though, the scene eerily anticipates the “enhanced interrogation” techniques that would become notorious at Guantánamo and Abu Ghraib. As The Guardian reported in 2008, US military played Metallica’s “Enter Sandman” at ear-splitting volume for hours on end, both at Guantanamo and at a detention center located on the Iraqi-Syrian border. At the other end of the musical spectrum, one of the other pieces played repeatedly was “I Love You” sung by Barney the purple dinosaur. Presumably the first was selected because of its aggressiveness, the latter because of its insipidness. But the Barney song has the distinction of being characterized by military officials as “futility” music – that is, its use is designed to convince the prisoner of the futility of their resistance.

Although, in 1940, Hitchcock could not have envisioned the use of heavy metal and kidvid music as elements of enhanced interrogation, the scene from Foreign Correspondent is eerily prescient. Viewed today, the scene also carries with it a strong element of political critique insofar as it associates such psychological torture techniques with a bunch of “fifth columnists” who are willing to commit murder and even engineer a plane crash in order to achieve their political ends. Touches like these make Foreign Correspondent seem timely today, more than seventy-five years after its initial release.

Alfred Newman the Elder

After Foreign Correspondent, Alfred Newman would go on to score more than a hundred and thirty feature films, and earn several dozen more Academy Award nominations. His nine Oscar wins remain an achievement unmatched by any other film composer. Newman died in Hollywood in 1970 at the age of 69, just before the release of his last picture, the seminal disaster movie, Airport. His work on Airport received an Oscar nomination for Best Original Score, the 43rd such nomination of his long and distinguished career.

For some film music scholars, Newman’s death marked the end of an era, as his career was more or less contemporaneous with the history of recorded synchronized sound cinema in Hollywood. As fellow composer Fred Steiner wrote in his pioneering dissertation on the development of Newman’s style:

As things are, we can be grateful for the dozen or so acknowledged monuments of this twentieth-century form of musical art— absolute models of their kind— that Newman did bestow on the world of cinema. Fashions in movies and in movie music may come and go, but scores such as The Prisoner of Zenda, Wuthering Heights, The Song of Bernadette, Captain From Castile, and The Robe are musical treasures for all time, and as long as people continue to be drawn to the magic of the silver screen, Alfred Newman*s music will continue to move their emotions, just as he always wished.

Because of its typicality, Foreign Correspondent may well seem like a speed bump on Newman’s road to Hollywood immortality. Yet it remains a useful introduction to the composer himself, who along with Max Steiner and Erich Wolfgang Korngold, is part of a triumvirate that would come to define the sound of American film music.

For more on music in Alfred Hitchcock’s films, see Jack Sullivan’s encyclopedic Hitchcock’s Music. For more on the production of Foreign Correspondent, see Matthew Bernstein’s Walter Wanger: Hollywood Independent. Readers interested in learning about Alfred Newman’s career should consult Fred Steiner’s 1981 doctoral dissertation, “The Making of an American Film Composer: A Study of Alfred Newman’s Music in the First Decade of the Sound Era,” and Christopher Palmer’s The Composer in Hollywood.

Tony Thomas’s Film Score: The Art & Craft of Movie Music includes Newman’s own account of his work for the Broadway stage before coming to Hollywood. Readers interested in an overview of the classical Hollywood score’s development should consult James Wierzbicki’s excellent Film Music: A History.

Alfred Newman conducts his most famous film theme, Street Scene, in the prologue to How to Marry a Millionaire (1953).

Is there a blog in this class? 2016

A Brighter Summer Day (Edward Yang, 1991).

KT here–

Another year has passed, and Observations on Film Art is approaching its tenth anniversary. The blog was never intended as a formal companion to our textbook Film Art: An Introduction. Basically we write about what interests us. Still, many of our entries use concepts from the book, and we hope that teachers and students might find them useful supplements to it.

As each summer approaches its end and teachers compose or revise their syllabi, we offer a rundown, chapter by chapter, of which posts from the past year might be relevant. (For previous entries, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015.) For readers new to the blog, these entries offer a way of navigating through the site.

Chapter 1 Film as Art: Creativity, Technology, and Business

Film projection made the national news in late 2015 when Quentin Tarantino released his new film, The Hateful Eight, on 70mm film. Only 100 theaters in the USA, most of them specially equipped with old, refurbished projectors, could show it that way. We went behind the scenes to see how the theaters coped in THE HATEFUL EIGHT: The boys behind the booth and THE HATEFUL EIGHT: A movie is a really big thing.

This year the studios took tentative steps toward instituting The Screening Room, a system of streaming brand-new theatrical films to people’s homes for $50. Whether or not this service succeeds, it represents one new distribution model that Hollywood is exploring to cope with the increasing delivery of movies via the internet. See Weaponized VOD, at $50 a pop.

Popular film franchises can go on generating new products and influencing other films for years. We examine the lingering impact of The Lord of the Rings thirteen years after the third part was released in Frodo lives! And so do his franchises.

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

In this chapter we put considerable stress on the concept of narration, the methods by which a film conveys story information to the viewer. There is no end to the ways in which narration can be structured. Often one of the characters in a film can to tell us what happened. . . even if that character is dead. This, as we show in Dead Men Talking, is not as rare as one might expect.