Archive for the 'Film technique: Performance' Category

THE LIGHTHOUSE: A period film with period style

Kristin here:

David and I first saw Robert Eggers’ The Lighthouse at the Vancouver International Film Festival, and he wrote briefly about it at the time. About halfway through the screening or less, I realized that what I was watching was a modern combination of two important historical trends of 1920s German cinema: Expressionism and the Kammerspiel.

I am partial to German silent cinema, particularly Expressionist films, for their daring stylization. The movement gave rise to some great films by two masters, F. W. Murnau and Fritz Lang. I’m even fond of the leisurely pacing that characterizes so many Expressionist and Kammerspiel films. At times some scenes resemble the slow cinema of recent decades.

Kammerspiel was a larger trend in the theater of the day, and it has its equivalent in English and American drama, the chamber play. Most of the Kammerspiel films in Germany were written by the great scenarist Carl Mayer, also responsible for many of the Expressionist classics from Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari on. Kammerspiel films include most notably Hintertreppe (Backstairs, Leopold Jessner, 1921), Sylvester (1923) and Scherben (1923). Some would consider Murnau’s The Last Laugh (1924) to be a Kammerspiel. Carl Dreyer also made one in Germany, Michael (1924, with a scenario by Thea von Harbou) and one in Denmark, The Master of the House (1925). Such films typically involve a small cast of characters who come into conflict in various ways, invariably ending badly, typically with death, suicide, murder, and/or imprisonment. The Lighthouse clearly qualifies.

The Lighthouse is also a horror film, or at least a lot of critics think so. Thus it fits cozily into the Expressionist movement, of which several Expressionist films are now considered early classics of the horror genre: Caligari, Nosferatu, Der Golem, Warning Shadows, Die müde Tod and other less well-known films.

Critics did not fail to notice The Lighthouse‘s links to silent cinema, and in particular Expressionism. Richard Newby’s review in The Hollywood Reporter remarks on: “The filmmaker’s decision to shoot the film in black-and-white and in the aspect ratio of 1.19:1, giving The Lighthouse the appearance of a silent film born of German Expressionism.” He also calls it, “Equal parts Lovecraftian horror story and existential chamber piece in the vein of Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit.”

Screen Daily reviewer Lee Marshall caught both the Expressionist and Kammerspiel aspects:

Shot in an expressionist black and white that harks back to cinema’s earliest years, The Lighthouse provides a marvellous chamber-drama platform for two actors, Robert Pattinson and Willem Dafoe, who seize the opportunity with gusto.

[…]

Referencing everything from German expressionist cinema of the 1920s to US silent comedy, the photography of Edward Weston and the from-the-ground-up perspective in the paintings of Andrew Wyeth, Jarin Blaschke’s photography is starkly compelling.

Manohla Dargis’ review in The New York Times explicitly notes German Expressionist cinema:

With control and precision, expressionist lighting and an old-fashioned square film frame that adds to the claustrophobia, Eggers seamlessly blurs the lines between physical space and head space.

The film’s more sustained pleasures, though, are its form and style, its presumptive influences (von Stroheim’s “Greed,” German Expressionism), the frowning curve of Winslow’s mustache, the whites of eyes rolled back in terror.

One might add that the dreams and hallucinations, shown from Winslow’s viewpoint, reflect the innovations of French Impressionist cinema of the 1920s. This sort of stylistic subjectivity, however, was highly influential and has been widely used ever since. It was quickly picked up in German cinema of the 1920s, and some of the classics of the day, especially The Last Laugh (1924) and Variety (1925), are more noted for their subjective camerawork than are the earlier French films that originated the practice. Overall, The Lighthouse has the flavor of a German film from the 1920s.

Lots of filmmakers have attempted to imitate silent cinema, and often they succeed to a degree. They shoot in black-and-white (but don’t add tinting and toning), put just music and maybe some sound effects on the track, and have some exaggerated acting. Perhaps they set the story in the past, as Michel Hazanavicius does with The Artist (2011). A more careful attempt is Blancanieves (2013).

No matter how careful the combination of such elements is, the result usually doesn’t really look like an old film. The Lighthouse really does look like a silent film, in the sense that it looks as if it were shot using the film stock available in that era. It does not, however, pretend to be a silent film, as The Artist does. The Lighthouse doesn’t eliminate the dialogue. Its narrative and tone bear distinct resemblances to those of German and French films of the 1920s, but its story is presented with more overt sexual content and extreme violence than mainstream silent movies would have included.

It helps that Eggers is clearly a cinephile and has watched a wide variety of films from many periods. Cinematographer Jarin Blaschke has also worked as a still photographer and also knows a great deal about older film stocks and lenses. They both knew a lot about films of all periods.

When asked in an interview for American Cinematographer what were the team’s “references” (films shown to crew members as models), Blaschke responded:

A bit of Béla Tarr for tonal dreariness and patient use of camera. Bergman’s camera language, as always. [Eggers’ liked the strong night lighting of In Cold Blood. There were some nautical silent films, including Flaherty’s Man of Aran, [which was shot] on orthochromatic stock with strong, direct close-ups. [The influence of] Eisenstein was there for montage, and bold, hard cuts. Optically, the films we watched from the ‘20s and ‘30s were very appealing in their subtle fringe distortions and the way highlights would shimmer. [p. 63]

In the end, the most influential references were M—an inspirational and modern film in terms of visual language—and Bresson’s Pickpocket, which influenced [our] use of close-ups, especially actions with hands. These helped steer The Lighthouse away from the purist confines of the turn of the century, and more toward early modernism.” [pp. 63-64]

M seems rather an odd choice, but Blaschke describes its inspiration in an interview for Kodak:

Watching that, I found a very modern film with surprising camera movement but more importantly: a modern, creative mastery in how visual information was withheld from the audience, how information was rewarded, and when,” says Blaschke. “With this new inspiration, I felt there was a highly-effective framework for me to express myself visually. Stepping away from a mere 19th-century emulation, we were on to something more surprising and layered.

In a DGA podcast interview, Eggers discusses the nearly-square aspect ratio:

And then, the boxy aspect ratio, we were shooting in 1:19.1, early-sound aspect ratio. There’s a Pabst film, Kamaradschaft, that takes place in a mine, which is probably the only other film that makes sense to use this aspect ratio, because Pabst is shooting vertical objects, like the smokestacks, and we have our lighthouse tower, and then the cramped mineshafts, and then the cramped interiors of this thing. Because we’re using spherical lenses, it’s actually taller, so it’s a great aspect ratio for these close-ups. You don’t need flab on the side. You just have Robert Pattison’s cheekbones, Willem Dafoe’s cheekbones in all their glory on these old lenses.

Who knows what other films are these two are familiar with? But one can assume that they watched some of the classic German films of the 1920s, both Expressionist and Kammerspiel.

The Lighthouse and German Silents

Early German Expressionist films often used jagged, abstract sets, more like paintings than like actual buildings or landscapes. Caligari is the most familiar instance, but here are a couple of examples from Von Morgens bis Mitternachts (1921, Karlheinz Martin).

The second image demonstrates particularly well how light was often represented by streaks of paint. The overhead hanging lamp at the upper left is a fringe of spikes, and the flames on the huge candlestick at the left are five wisps of paint. Highlights from these “lights” are painted on the desk and chair at the lower left.

Hollywood films have seldom used distorted sets of this kind. They appear occasionally, as in Son of Frankenstein (1939, Rowland V. Lee) and Beetlejuice (1988, Tim Burton). Most of the time, though, when people speak of expressionist style in films noir or horror films, they’re talking about graphic effects created by lighting. That lighting is not created by streaks of paint but by fancy lighting effects. That’s mostly the case in The Lighthouse. The lighthouse tower and the service buildings around it were designed to be authentic copies of features in real historical lighthouses. The distorted stylization comes from lighting effects, from simple underlighting to patterns created by patterned holes in the lighthouse interior.

The same is true of acting. In German Expressionist films, actors’ faces were often painted, especially with dark patches around the eyes and pasty white skin. Compare this close-up of Ernst Deutsch’s face, as the Cashier in Von Morgens bis Mitternachts, with that of Robert Pattinson, where the distortions are created by light and shadow.

Most of the classic German Expressionist and Kammerspiel films were studio-created. Sets were built either in studios or on extensive backlots. In contrast, Eggers wanted to use an authentic lighthouse. Scouting failed to turn up one with adequate access roads, so the lighthouse and service buildings were built, with faithful adherence to period locales, near the tip of the Cape Forchu Lighthouse peninsula (down the road from a modern lighthouse).

This location is far from from isolated, but the film manages to create a sense of loneliness and dread nonetheless. The huge crashing waves and storms were not generated digitally but were practical effects. According to the Kodak story, “Most of the water work was shot in a large, emergency-responder’s training pool, capable of generating waves in varying sizes and patterns, located near Halifax.” The film contains a few digital effects, mainly to turn the peninsula into an island.

Eggers seems to share the sensibility of the German silent directors: “In a perfect world, I would have liked to have built every single building, for control, control, control, control, control.” (From the DGA interview)

As to Kammerspiel films, The Lighthouse reminds me most of Scherben, which deals with a man who works as a linesman for a railroad. He, his wife, and their daughter live in isolation in some woods and live a stultifyingly dull existence. The intrusion of a railroad inspector who seduces the daughter leads to drama as the linesman gradually becomes enraged and kills him. The style of the film is quite different from that of The Lighthouse, but the dynamics of conflict and gradual deterioration of the central character are somewhat similar–if more restrained in his slow burn and stolid demeanor.

Scherben only became generally available earlier this year, when I wrote about its Filmmuseum Edition DVD release. I have no idea whether Eggers ever saw it at an archive screening or in somewhere else. He more likely saw Hintertreppe, which has long been the only one of the classic Kammerspiele commonly accessible.

Bringing back orthochromatic, sort of

In the DGA interview, Eggers discusses the choice of film stocks:

We thought orthochromatic film stock would really be the way to go, which, among other things, the main thing about orthochromatic film stock is that it’s not sensitive to red, so red is rendered black. So the rosy skin tones on a Caucasian renders darker. So Eisenstein, that’s why all those Russian faces look so tan, and in Hollywood they’re wearing white pancake makeup to compensate for the orthochromatic stock [….] So we liked Double-X negative. The blacks bottom out suddenly in a way that’s very satisfying, as we remember it from watching old movies.

Apparently Eggers and Blaschke investigated having orthochromatic 35mm stock custom-manufactured for them, but the expense was too great. A cheaper way had to be found.

In the American Cinematographer interview, Blaschke describes testing Kodak’s Double-X 5222 35mm film, color 35mm negative film, and digital capture with an Arri Alexa: “In addition to much larger grain, the Double-X has more ‘tooth.’ Even if you match the overall contrast in the DI [digital intermediate], the Double-X had more ‘local’ or ‘micro’ contrast, which emphasizes texture and better differentiates similar tones” [p. 61]. (Double-X 5222 was introduced in 1959 and has been used on such films as Raging Bull [1980] and Schindler’s List [1993].)

Despite these advantages, however, Double-X is a panchromatic stock, with sensitivity to the entire visible spectrum. To solve this “problem,” Blaschke ordered a custom-made filter that would eliminate the red-to-mid-yellow end of the spectrum, thus simulating orthochromatic film effectively [AC, pp. 66-7].

The choice of lenses was also done with an eye to maintaining the artificial orthochromatic look. Blaschke tested many vintage lenses and settled on Baltars, designed in 1930s. The two used in the film were made in 1941 and 1944. In the Kodak interview, he says, “The vintage Baltars were the most shimmery of the bunch I tested, and really were the most stunning portrait lenses I have ever seen,” he says. “The highlights really glowed, but stopped just short of heavy-handedness. Optics like these could add a layer of complexity on top of our hard, orthochromatic look to pull people into the world of the film.” A rehoused 1905 50mm lens was used for some flashback images, and some replicas of 1840 Petzval lens designs were used in flashbacks and “heightened moments”[AC, p. 64]. Blaschke describes the effect in an interview on the Motion Picture Association website: “Blaschke says that for those more “out there sequences,” he had a special lens designed—called a petzval—that contains a lot of aberrations. “It creates a very squirrely look. The background almost falls out of focus, like a globe, and you get this very swirly effect.”

Lighting The Lighthouse

Those swirling light patterns you see on Pattinson’s face in the movie are a real phenomenon—we found ourselves just wanting to gaze into the Fresnel lens. We could have stayed all night staring into the light.

Robert Eggers, Cannes Press Release

Apparently the decision to set the film in the 1890s arose during the search for the ideal lighthouse. In an interview with Eggers in Architectural Digest, he remarks, “‘I wanted there to be a mystery in the light. Inside the beacon. So we knew we needed to set it in a period where we would have a Fresnel lens,’ he explains. Not many lighthouses still have functional ones today. ‘They look like Art Deco spaceships, and they are very magical and jewel-like. So we knew that was going to place us in the second half of the 19th century.'” (See the bottom for an image of the film’s custom-made Fresnel lens mesmerizing Winslow in the climactic scene.)

The decision to imitate orthochromatic film had a considerable impact on the lighting used. Ironically, it meant that a great deal of light from modern lamps, had to be used. Eggers admits as much in the DGA interview.

Obviously we weren’t lighting it like an old movie. We were lighting it using our practical fixtures, but of course, if this were an old movie, you would see the flame of the kerosene lamp and there would be a movie light lighting the scene. But what we did was we had a 600W halogen bulb on a flicker dimmer in all those scenes. And it was really, coming from Alexa and fast film stock, it was so bright. People were wearing sunglasses when we were doing night interiors.

Double-X is slow, even slower than color negative stocks. Modern digital cameras can typically shoot with less light than shooting on film requires. Putting together slow film stock, a filter (albeit one that cut down the light availability by less than one stop), and older, slower lenses meant that the cinematography crew had to use huge amounts of light, as a Variety interview with Blaschke explains:

Blaschke says he prefers to model his lighting in a real-life way, which was tricky on “The Lighthouse.” He and gaffer Ken Leblanc worked with Kodak Double-X stock — Blaschke calls it the only practical black-and-white film left after Plus-X was discontinued in 2011 — which is much less sensitive to light than even color film stock. Between the optics, the film stock and the filtration, Blaschke and Leblanc had to use about 15 to 20 times more light on set to get the look they wanted than on “The Witch,” which was shot on an Alexa.

“Even though it’s a very dark movie, the sets were actually blindingly bright,” says Blaschke. “We’d put 500- to 800-watt halogen bulbs in the lanterns that would flicker and were only a few feet from an actor’s face. The way we make movies now, people have gotten used to a very low light level; it’s trendy to shoot wide open, digitally at 800 or even 2,000 ASA. Our actors talked about how they couldn’t see each other sometimes, which I felt bad about.”

This halogen light is used in the night interiors, such as the scene of the drunken dance, below, and the later scene of the pair drinking in their shared bedroom, at the top of this section and the entry.

This combination of a very bright lamp with slow film and a filter cutting down part of the spectrum of light entering the lens meant that the light fell off very quickly away from the lantern. That effect is also very evident in these scenes. Backgrounds are dimly visible, and the actors often become silhouettes.

The result is a heightened sense of the two main characters being trapped together in small islands of light surrounded by blackness. We have no sense of how many lanterns the house contains, but we never see more than one at a time. At one point Winslow is seen in bed with a book, and the dim light from the window above him makes it hard to believe that he can see well enough to read. Even the daytime scenes are gloomy and gray. A low angle with the blank, light sky as rendered by the “orthochromatic” film makes Winslow and the dark rocks around him look nearly black.

Few silent films shot on orthochromatic film look this consistently dark, and it’s clear that the filmmakers were not simply trying to replicate the look of an old film. Blaschke admits as much in yet another of the many interviews on the film’s techniques: “It wasn’t about trying to make it look like older films but rather choosing a frame that lends itself to the tall and narrow sets and helps you visually withhold information from the audience. It also had a secondary effect of evoking compositions of 20th century modernist photography,”

In the DGA interview, after describing the various technical details of design, setting, and cinematography, Eggers explains:

This is fussy and it’s nerdy and it’s fun to talk about in this forum, but why do this? One, it says the movie’s old; it takes place in a time when black-and-white photography existed. But two, this is a bleak, austere story, and I feel like black-and-white is the best way to tell this story, and color is only going to mar things. Again, with this orthochromatic filter, it knocks our blue skies, which if we have them—which we really did—into something white and bleak and stark and harsh.

To get really nerdy about it, panchromatic film stock had largely replaced orthochromatic by the late 1920s and early 1930s, the only period in which a nearly square aspect ratio was standardly used. Moreover, the Baltar lenses were invented in the 1930s. Halogen lamps are a comparatively recent innovation in film lighting. So the combination of the ortho and the boxy look and the rest of it aren’t “authentic” in any strict sense. The filmmakers were not using lighting equipment of the 1920s or any modern equivalent. In short, they weren’t trying to replicate the look of any one specific type of old film. As a way of creating the illusion of an old film, as well as an appropriately grim tone, it works better than anything else I’ve seen.

A few final notes

First, I have seen The Lighthouse’s budget given as $4 million. That’s in the film’s Wikipedia entry, which cites an AP release from May 2019 that says only that the film’s budget was larger than that of The Witch but still modest. The New York Times ran a story about the film’s trailer in July, noting that the budget for The Witch had been $4 million, which Box Office Mojo also gives as the cost of the earlier film.

I have not been able to find a reliable figure for The Lighthouse’s budget, but clearly it was distinctly more than $4 million.

Second, according to Eggers in the DGA interview linked above, that’s real dirt (sifted to rid it of the odd pebble) that Winslow shovels down onto Wake in the climactic scene–not some namby-pamby ground chocolate. Not to mention that the puddle he’s lying in was frigid. Even the Expressionist actors didn’t go so far. The Academy should give Dafoe his Oscar already.

Third, watching The Lighthouse with a sell-out crowd in the biggest venue at the Vancouver International Film Festival, The Centre for the Performing Arts, was one thing. There people were eager to see this film, which had premiered in the Directors’ Fortnight thread at Cannes in May. It won the International Federation of Film Critics (FIPRESCI)’s prize for best film. It was quite another thing to watch it by myself during its run at a local multiplex.

The Lighthouse played at three multiplexes in Madison, with full-day schedules at each. It’s still playing at one of them, twice a day. I was alone when I saw it a few days ago at a 10:25 am screening. After being in a crowded festival audience, the second experience made me wonder how in the world such a challenging film made it into such wide release and how a more mainstream audience would react to it. (It maxed out at 958 theaters November 1-6 and has been falling since. Its gross through November 10 is $8,915,216 domestically; Box Office Mojo so far has no figures for foreign markets.)

The frames from The Lighthouse have mostly been taken from trailers. I have not cropped the frames reproduced above to their 1.19:1 format, since on theatrical screens, the audience sees the image as window-boxed, with black stretches on either side. (The exception is the bottom image, a press image released by distributor A24; it is either a frame with the black sides cropped or possibly a production still.) Perhaps Eggers and Blaschke’s idea would have been for theaters to move the screen’s masking to the edges of their images. Given the realities of modern exhibition, however, such versatility is not part of the screening technology. I found that the window-boxing on the big screen was a constant, subtle way to call attention to the unusual compositional results. What The Lighthouse will look like on various formats for streaming is hard to imagine.

Speaking of the aspect ratio, a number of critics have called 1.19:1 a silent-film format. In fact it was only used in the early sound era, when room had to be made on the filmstrip for the optical soundtrack; later the image was shrunk slightly into the classic Academy ratio of roughly 4:3. During the silent period there was no absolute standard ratio, though the image was in usually not far from the Academy ratio.

The American Cinematographer article cited is Patricia Thomson, “Stormy Isle,” AC (Nov 2019): 60-67.

In one of the quotations above, Blaschke says that Man of Aran (1934) was shot on orthochromatic film. This seems unlikely, given that Flaherty had made one of the first American features to use the new panchromatic film stock, Moana (1926). Kodak stopped making ortho in 1930. Possibly Flaherty, who started work on the film in 1931, did revert to ortho for it, but it seems unlikely.

Ernst Deutsch, who plays the Cashier in Von Morgens bis Mitternachts, was one of the great Expressionist actors of stage and screen. I have mentioned him before, for his role in Der Golem; when Von Morgens bis Mitternachts was released on DVD; and for his role in the non-Expressionist Das alte Gesetz, released on Blu-ray by Flicker Alley last year.

On horror and fantasy in German silent films, see my “Im Angang war …: Some Links between German Fantasy Films of the Teens and the Twenties,” in Paolo Cherchi Usai and Lorenzo Codelli, eds., Before Caligari: German Cinema, 1895-1920 (Pordenone: Edizioni Biblioteca dell-Immagine, 1990), pp. 138-161.

Baschke mentions Eisenstein as an influence in the editing, but presumably neither he nor Eggers had read Eisenstein’s essay arguing in favor of a square aspect ratio. His belief was that such a frame would give equal compositional weight to the horizontal and vertical dimensions of the screen. (“The Dynamic Square,” Jay Leyda, ed., Film Essays and a Lecture [New York: Praeger, 1970], pp. 48-65.

The photograph of the lighthouse set on Cape Forchu is by Dan Robichaud and appears in Carla Allen’s story on the filming in the local Digby Courier. A search for “Cape Forchu Lighthouse” on Google Maps yields many photos of the area and reveals the very rocky terrain over which Winslow pushed his wheelbarrow. The modern lighthouse is a popular tourist attraction, in case you ever visit Yarmouth in Nova Scotia. There is even a restaurant inside it. (Appropriately enough, “The grilled lobster and cheese sandwich was amazing,” according to one visitor.)

[January 13, 2020. Blaschke has been nominated for an Oscar in the Best Cinematography category. Unfortunately the film was not nominated in any other category, as it deserved to be.

February 8, 2020. Blaschke has won a number of awards for the film, most notably the American Society of Cinematographers Spotlight Award, and, just today, the Film Independent Spirit Award for best cinematography.]

Accident forgiveness: J.J. Murphy’s REWRITING INDIE CINEMA

Maidstone (1970).

DB here:

Did you ever want to beat up Norman Mailer? The impulse must have flitted through the minds of many who paged through his work, saw him on TV, or encountered him swaying pugnaciously at a party. Rip Torn took the opportunity. One day in 1968, he whacked Mailer with a hammer and started to strangle him. As the distinguished author tried to bite off Torn’s ear, Mailer’s wife leaped into the fray and his children shrieked with fear.

This scene, totally unscripted, appears in Mailer’s film Maidstone (1970) and opens J. J. Murphy’s new book Rewriting Indie Cinema: Improvisation, Psychodrama, and the Screenplay. Nothing could better prepare us for his exploration of the traditions–and sometimes jarring consequences–of spontaneous performance in modern American movies.

I couldn’t have predicted that J. J., who was in grad school with Kristin and me, would turn to research. He began as part of the Structural Film movement, achieving wide renown with Print Generation (1974) and (my personal favorite) Sky Blue Water Light Sign (1972). After he was hired here at Wisconsin, he rejuvenated our production program and went on to make independent features: The Night Belongs to the Police (1982), Terminal Disorder (1983), Frame of Mind (1985), and Horicon (1994).

I couldn’t have predicted that J. J., who was in grad school with Kristin and me, would turn to research. He began as part of the Structural Film movement, achieving wide renown with Print Generation (1974) and (my personal favorite) Sky Blue Water Light Sign (1972). After he was hired here at Wisconsin, he rejuvenated our production program and went on to make independent features: The Night Belongs to the Police (1982), Terminal Disorder (1983), Frame of Mind (1985), and Horicon (1994).

At the same time, he was teaching both production and screenwriting. His books reflect his deepening interest in the creative process of making a film outside the Hollywood system. His initial study, Me and You and Memento and Fargo: How Independent Screenplays Work (2007), focused on the principles of screenplay construction that emerged with US indie cinema. Then, in The Black Hole of the Camera: The Films of Andy Warhol (2012), J. J. offered the most complete analysis of this superb body of work. In the process, he opened up a new vein of exploration. The idea of psychodrama proved an exciting way of explaining the fascinating, awkward performances in films like Kitchen (1965), Vinyl (1965), and Bike Boy (1967).

Now the concept of psychodrama gets full play in an ambitious account of the changing role of improvisation in off-Hollywood cinema. What happens, J, J. asks, when filmmakers give up the screenplay? How do they construct a story, define characters, build performances? Rewriting Indie Cinema sweeps from the 1950s to recent films like The Rider and The Florida Project. By looking for alternatives to the fully prepared screenplay, it posits a fresh way of thinking about American film artistry.

Human life isn’t necessarily well-written

Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1968).

To start off, J. J. proposes that we think of improvisation in a systematic way. Of course, the concept can be treated broadly. Even Hitchcock, we learn from Bill Krohn, improvised on the set much more than he claimed. But J. J. suggests that improvisation can be considered as a basic creative concept, a founding choice for art-making.

In the 1950s, many American artists began to embrace chance, accident, and personal expression. Abstract Expressionism, bebop, the Judson Dance Theater, Robert Frank’s snapshot aesthetic, and other tendencies valued spontaneity as both authentic self-expression and a challenge to conformist culture. The idea of spontaneity was carried into cinema by Jonas Mekas and fueled what became the New American Cinema of John Cassavetes, Shirley Clarke, and other filmmakers.

But the idea had deeper sources in another trend that J. J. painstakingly brings to light. The Austrian theater director Jacob L. Moreno developed in the 1920s what he called the Theatre of Spontaneity (Das Stegreiftheater). Performances consisted of purely improvised dialogue. When Moreno emigrated to America, he founded “Impromptu Theatre” in the same vein. His 1931 performance at Carnegie Hall was greeted by the New York Times with some disdain:

The first play, like the ones that followed, turned out to be a dab of dialogue uneasily rendered by its hapless players. . . . It became more and more evident that heavy boredom, rather than “forms, moods and visions,” were [sic] the product of the actors. Demanding wit above all else, the Moreno players lacked that essential as fully as the premeditation upon which they frown so heartily. The legitimate theatre, it can be reported this morning, is just about where it was.

Of course improvisation had already proven its worth in vaudeville and in jazz and other musical idioms. Today versions of Moreno’s “spontaneous theatre” flourish in comedy clubs.

Before coming to America, Moreno had discovered that improvisation had therapeautic functions as well. When a couple enacted the frustrations of their marriage, the audience was moved and Moreno was convinced that this “psychodrama” harbored artistic possibilities. Moreno’s wife Zerka called psychodrama “a form of improvisational theatre of your own life.”

J. J. shows Moreno’s pervasive influence on the postwar American scene. Psychodrama became one trend in social psychology, used to help prisoners, narcotics addicts, and even business executives. Woody Allen, Arthur Miller, and other artists were aware of Moreno’s work as well.

Drawing on Moreno but recasting him for film-related purposes, J. J. proposes a spectrum of improvisational options. There’s the completely improvised, ad-lib option, seen in Maidstone and much of Warhol’s work. Here the performers just make it up as they go, though with minimal framing of a situation. Then there’s the possibility of “planned” improvisation, in which there’s a story outline and more or less pre-set scenes. Sean Baker’s Tangerine (2015), for example, was made from a seven-page treatment that included only a couple of lines of dialogue. Then there’s the “rehearsed” option, in which the players collaborate to prepare the scenes and develop the characters, workshop fashion. In production the performers mostly stick to the “script” they’ve created. J. J. points to the films of Cassavetes as a clear case.

Any given film can mix these options, so that some scenes are planned roughly while others are purely ad-lib. And a filmmaker can explore the spectrum across several films, as Joe Swanberg has done.

Where does psychodrama come in? J. J. shows that any of the three points on the improvisation spectrum–pure, planned, and rehearsed–can yield performances that are based in the actual mental states and personal histories of the players. In our Cinematheque screening devoted to his book, Abel Ferrara’s Dangerous Game (1993) served as an example. Harvey Keitel invested his character, an intransigent film director, with the still simmering emotions he felt after his breakup with Lorraine Bracco. Meanwhile Ferrara set up scenes that would provoke Madonna, playing Keitel’s actress, to break character and reveal her immediate responses.

Ferrara wanted to attack Madonna’s celebrity image, and J. J. reads the aftermath to a rape scene in the film being made as projecting the star’s own stammering outrage at having been exploited.

Throughout the book, when improvisation becomes psychodrama, fiction moves closer to documentary. The last chapter examines how certain films considered documentaries, like Robert Greene’s Actress (2014) and James Solomon’s The Witness (2015), cross over into psychodrama from the other side, so to speak.

A detailed study of William Greaves’ Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1968) shows how Greaves used psychodramatic techniques to create an even more complicated film-within-a-film than Dangerous Game. Two characters, Freddie and Alice, are played by five different pairs of actors, with all their scenes recorded by a bevy of camera and sound staff.

Greaves also incorporates self-criticism. When crew members object to the script, another participant remarks: “Human life isn’t necessarily well-written, you know.”

Given these conceptual tools, J. J. goes on to trace the production methods employed by a wide range of filmmakers, from Morris Engel in The Little Fugitive (1953) and Cassavetes in Shadows (1959) to Mumblecore and after. Through a mixture of film analysis and background research, he brings to light a vast variety of creative options that can bypass fully-scripted cinema.

Rewriting the unwritten

Paranoid Park (2007).

J. J.’s survey of production methods is embedded in a new historical argument about the shape of off-Hollywood filmmaking. The New American Cinema of the 1950s, which Mekas called “plotless cinema,” was wedded to a sense of realism. But it operated within limits. Cassavetes serves as a benchmark: “I believe in improvising on the basis of the written work and not on undisciplined creativity.” By balancing the planned with the impromptu, his films allowed for the actors to surprise one another. At the same time, Shirley Clarke’s Portrait of Jason (1967) showed how psychodrama could pass easily into documentary, exemplifying Erving Goffman’s theory that everyone is playing theatrical roles in everyday life.

This open approach to screenwriting and screen acting was explored by many filmmakers in the 1960s and a little after: not only the well-known Warhol and Mailer but also Kent Mackenzie, Barbara Loden, William Greaves, and Charles Burnett. J. J. examines all this work in admirable detail. I was especially happy to see that he includes Jonas Mekas’ The Brig (1964), the harrowing film that showed me, in my undergrad days, what the New American Cinema could do in filming a play.

By the time Ferrara made Dangerous Game, most independent filmmaking had moved away from improvisation toward more tightly scripted expression. J.J. traces the institutional pressures operating here. The Sundance Film Festival and PBS’s American Playhouse favored fully-planned projects compatible with the Hollywood standard. The Sundance Institute, launched in 1981, explicitly aimed to correct what was considered the two faults of independent production: screenplays and performances.

The success of polished work like sex, lies, and videotape (1989) and Pulp Fiction (1994) created new norms for American indie cinema. Director-screenwriters like Soderbergh, Tarantino, David Lynch, Hal Hartley, Todd Haynes, the Coens, and Todd Solondz were models for younger filmmakers. As J. J. points out, their screenplays were often published as part of the marketing of the films. Framing the new trend as dominated by the screenplay helped me understand why Bryan Singer, Doug Liman, Karyn Kusama, and other indie filmmakers who came up in the wake of this generation moved so easily to mainstream genres and big-budget projects.

But history plays strange tricks. In the 2000s, filmmakers who felt constrained by the demands of tight scripting began to try something else. J. J. pays special attention to Gus Van Sant, who after proving his commercial craft, made some films with varying degrees of improvisation: Gerry (2002), Elephant (2003), Last Days (2005), and Paranoid Park (2007). Some of the Mumblecore directors relied on screenplays, but the prolific Joe Swanberg adopted a free-form approach, to which J. J. devotes a chapter.

J. J. goes on to survey the work of Sean Baker, the Safdie brothers, Ronald Bronstein, and other directors who have revived the New American Cinema’s impulses in the digital age. He concludes:

Digital technology in effect, democratized the medium, allowing young filmmakers to revive cinematic realism precisely at a time when indie cinema was at risk of losing its identity. In the new century, the use of improvisation and psychodrama provided a sense of continuity with indie cinema’s roots.

J. J. retired from UW–Madison at the end of 2018, and last Saturday night he was honored at our annual screening of student projects. He has been a constant force for good in our department, and we owe him more than we can say. Among those debts is this outstanding contribution to US film studies.

The book’s title carries a double meaning. American independent cinema has been, at crucial periods, “rewritten” by filmmakers who relied on spontaneity rather than a cast-iron screenplay. At the same time, J. J.’s panoramic research in effect rewrites that history. I’m sure that other researchers will build on his wide-ranging arguments, which put the creativity of artists–filmmakers, performers–at the center of our concerns.

J. J.’s books join a cascade of recent work by other colleagues here at Wisconsin. This blog has highlighted Jeff Smith’s Film Criticism, the Cold War and the Blacklist (2014), Kelley Conway’s Agnès Varda (2015), Lea Jacobs’ Film Rhythm after Sound (2015), Lea’s and Ben Brewster’s enhanced e-book of Theatre to Cinema (2016), and Maria Belodubrovskya’s Not According to Plan: Filmmaking under Stalin (2018).

P.S. 9 May 2018: Thanks to Adrian Martin for correction of a misspelled name!

Kelley Conway awards J. J. Murphy a gilded Badger at the Communication Arts Showcase, 4 May 2019.

From transistors to transmedia: Talking Heads tell TRUE STORIES

True Stories.

Jeff Smith is no stranger to this blogsite. He has written several entries, some based upon his Criterion Collection commentaries for FilmStruck, others on topics related to film sound and scoring. Here he brings his massive expertise to bear on the music of True Stories, newly available in a 4K transfer from Criterion.–DB

Jeff here:

As promised, this is a follow-up blog to David’s discussion of True Stories and its collage of tabloid culture, kitsch, Performance Art, Robert Wilson, Andy Warhol, Jeff Koons, and Our Town. At least some of these connections also characterize the New York music scene in the 1970s from which Talking Heads emerged. Buoyed by the energy of punk and New Wave, Byrne had long straddled the boundaries between mass culture and the avant garde.

As before, Andy Warhol serves as something of a role model. Besides designing album covers for mainstream pop performers, such as the Rolling Stones, Billy Squier, and Diana Ross, Warhol also served as the nominal producer of The Velvet Underground & Nico. The artist himself is also the subject of David Bowie’s “Andy Warhol” from Hunky Dory and Lou Reed’s “Andy’s Chest,” an outtake that eventually surfaced on VU, the 1985 compilation of Velvet Underground miscellany.

Working in the opposite direction, Byrne and company’s connections to the Manhattan cultural scene gave their work a kind of artistic credibility. Yet their avant garde impulses were always counterbalanced by a veneration of the soul, funk, and blues music that shaped rock and roll’s art and history. In what follows, I trace the long and winding road Talking Heads took in their journey to True Stories, both as film and as album.

Making the scene

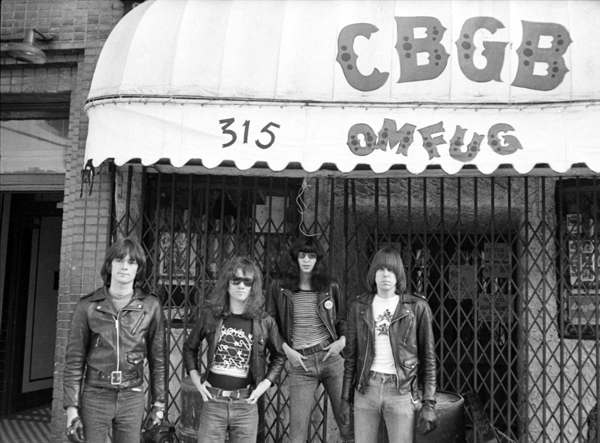

The Ramones at CBGB in the 1970s.

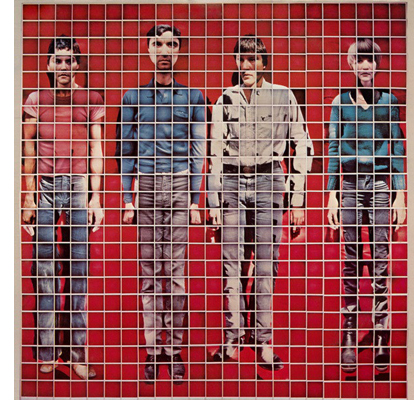

David Byrne’s band, Talking Heads, is almost certainly the most successful group to emerge from the downtown New York music scene of the late 1970s. Of the eight albums the band released between 1977 and 1988, seven of them were certified either gold or platinum. Little Creatures, the album released just before True Stories, went double platinum, selling more than two million units. So did Stop Making Sense, the soundtrack to their concert film directed by Jonathan Demme.

At the start of their recording career, much of the energy surrounding the New York music scene centered on the venerable East Village club, CBGB. Its name was short for “Country, Bluegrass, and Blues.” Yet the bands who came to be identified with the venue were about as far away from roots music as you could get. Initially, CBGB was associated with the emerging American punk rock scene. The Ramones were frequent performers as were the Plasmatics, Richard Hell and Voidoids, and Johnny Thunders’ band, the Heartbreakers.

Yet the range of musical styles represented at CBGB ventured quite far afield from the sped-up, chainsaw guitar sounds of punk. Patti Smith channeled her inner Rimbaud over Lenny Kaye’s Nuggets-inspired guitar lines. Television featured the evocative string-bending of Tom Verlaine. who stretched out in long solos using modal scales that fused Ravi Shankar with John Coltrane. James Chance and the Contortions showcased the wild saxophone playing of their frontman, specializing in a peculiar form of avant-funk jazz. Blondie began by refashioning sixties garage rock into their own brand of punk. But their style became more eclectic, branching out to include disco, calypso, and rap. They attained a huge crossover success in the process, thanks to lead singer Debbie Harry’s sex appeal and sultry alto.

Talking Heads sounded like none of these. “New Feeling,” the second track on their debut album, established the template for the band’s music: skittering guitar lines, tightly wound rhythms, and David Byrne’s strangled yelp. Its spare, spiky pop sound featured the rhythmic interplay of Byrne’s and Jerry Harrison’s guitar lines and the precise sixteenth note fills of drummer Chris Frantz.

Talking Heads 77 occasionally added elements that slightly broadened their musical palette. Think of the steel drum sounds that color “Uh-Oh, Love Comes to Town” or the loping electric piano chords of “Don’t Worry About the Government.” Indeed, the latter wouldn’t sound out of place in a Sesame Street bumper.

Yet, the album’s flagship single was “Psycho Killer” for a reason. Its nervy energy epitomized the group’s sound in its early days at CBGB. This was rock and roll to be sure. But it seemed like the kind of thing the subject of Edward Munch’s The Scream would dance to if he ever got off that bridge.

Talking Heads’ follow-up, More Songs About Buildings and Food, initiated a period of fruitful collaboration with producer Brian Eno. Using synthesizers and other keyboard instruments to flesh out the band’s sound, Eno nudged the Heads toward more danceable tunes. Built on Tina Weymouth’s pliant, bouncy bass lines, songs like “Found a Job” and “Stay Hungry” saw the band incorporating elements of seventies funk, soul, and disco. The band’s cover of Al Green’s “Take Me to the River” also gave the group their first chart hit.

That single’s slow climb peaked the same week of Talking Heads’ television debut on Saturday Night Live. For many viewers, this was their first encounter with Byrne’s “Norman Bates meets Pete Townshend” persona. And, even though Byrne’s hipster nerd desperation seemed the absolute antithesis of Green’s “lover man” come-on, his apparent interest in exploring black musical idioms felt almost painfully sincere.

Bringing Noho to the bush of ghosts

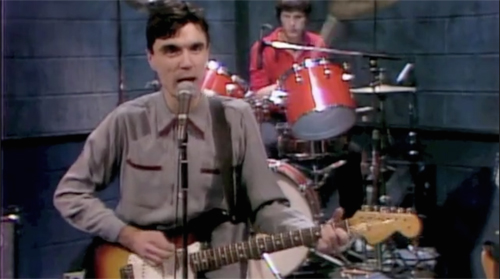

Music video for Once in a Lifetime.

Over the next three albums, the Heads’ collaboration with Brian Eno pushed them even deeper into world musical cultures. The band simplified their song structures, but increased the complexity of their arrangements and instrumentation. “I Zimbra” added Cuban, Brazilian, and African percussion along with the signature stylings of Robert Fripp’s guitar work. Remain in Light‘s densely layered synthesizers, various types of drums, and percussion atop the guitars, bass, and trap set that had been the core of the group’s sound since their first album. Created through countless overdubs that enabled each band member to play percussion alongside their normal instruments, the album featured extended Afrofunk and worldbeat grooves that interwove “call and response” vocal lines with intricate polyrhythms.

To recreate this sound on stage, the band recruited several players from other groups. On tour Talking Heads became a sort of New Wave supergroup with King Crimson’s Adrian Belew on guitar, Ashford and Simpson’s Steve Scales on percussion, and Funkadelic’s Bernie Worrell on keyboards. The expansion of Byrne’s musical vision was nothing short of stunning. Using improvised jams and communal music-making as a point of departure, Remain in Light went well beyond the faux gospel and art school irony of “Take Me to the River.” By mixing preachers’ rants with the wordplay of Bronx rappers, Byrne discovered his inner Fela Kuti.

Talking Heads start making cents (on sync licenses)

1983 would prove to be a watershed year for Talking Heads. The band released Speaking in Tongues, which spawned their first top ten hit, “Burning Down the House.” The record also represented a kind of apotheosis. It was less musically adventurous than Remain in Light. But it seamlessly blended the band’s early New Wave sound with its later Afrofunk influences. Instead of grooving on one chord, most songs on Speaking in Tongues contained more conventional harmonic changes. And instead of building songs out of shorter “loops,” the new record featured much more traditional song structures with clear demarcations of verses, choruses, and bridges.

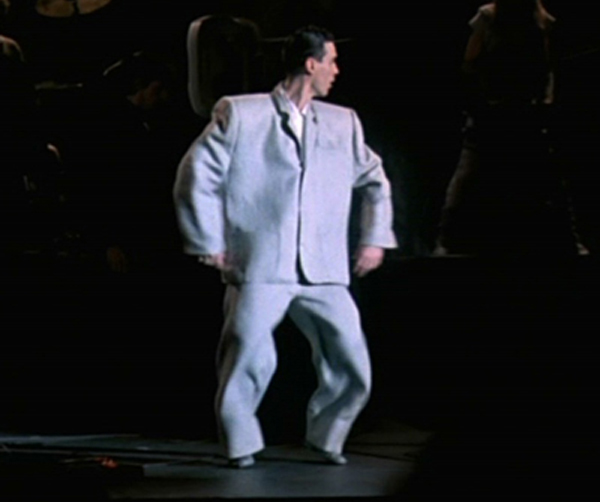

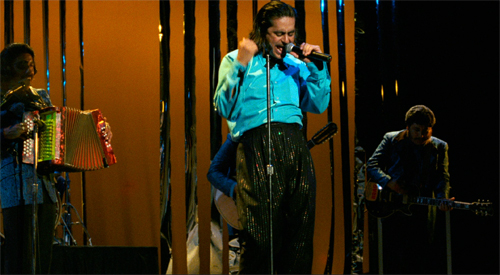

The album also served as the centerpiece of Jonathan Demme’s concert film, Stop Making Sense, which was filmed over four separate dates in December of 1983 at the Pantages Theater in Los Angeles. The set list more or less traced the history of Talking Heads, beginning with David Byrne performing “Psycho Killer” on an acoustic guitar accompanied by a rhythm track played back by a boombox. It closed with a performance of “Crosseyed and Painless” that featured the full tour ensemble, including Scales, Worrell, guitarist Alex Weir, and two female backup singers. In between, Byrne bounced around the stage in his big white suit, turning the concert stage into a space for performance art. As before, Byrne seemed to self-consciously reject the usual rock star poses. Instead, he shook, squirmed, and jerked like a giant white Gumby on a hot tin roof. Stop Making Sense went on to become a modest commercial success and won the National Society Film Critics award for Best Documentary of 1984.

Between 1983 and 1986, Talking Heads also saw their profile raised by the use of songs in other popular films. The group had already been featured in a motley group of titles prior to Speaking in Tongues. “Life During Wartime” was included in Alan Moyle’s Times Square (1980), a teen comedy about two aspiring punk singers in New York. But so was almost every other hot artist of the moment, such as Joe Jackson, Gary Numan, the Cars, the Cure, and the Pretenders. The Heads had also performed “Psycho Killer” in Bette Gordon’s short film, Empty Suitcases.

The industry surge in soundtrack sales in the early to mid-eighties, though, gave Talking Heads access to more high-profile studio projects. “Burning Down the House” made an appearance in the rowdy fratboy comedy, Revenge of the Nerds. And the use of “Once in a Lifetime” over the opening credits of Paul Mazursky’s Down and Out in Beverly Hills (1986) fueled the song’s return to Billboard’s Hot 100 more than five years after it was released.

A much more interesting case of music licensing occurred with the push given to “Swamp,” the opening track on side two of Speaking in Tongues. Robbie Robertson of The Band selected the song for inclusion on the soundtrack of King of Comedy (1982) well before the album was released. It then appeared again just months later in the Tom Cruise teen comedy, Risky Business. The reuse of “Swamp” so soon after Scorsese’s film might well be a case of serendipity. Paul Brickman, Risky Business’ screenwriter and director, likely glommed onto it when he heard David Byrne intone the phrase “risky business” in the song’s last verse.

“Swamp,” though, anticipated yet another change of direction in the band’s music. Unlike the worldbeat influences that were still evident in the rest of Speaking in Tongues, the track returned Talking Heads to American terra firma, more specifically the musical idioms of the Mississippi delta. A slow, blues shuffle tune with strong triplet rhythms, “Swamp” was truly unlike anything else the group had done before. Floating on Bernie Worrell’s funky synth textures, it sounded like a Parliament cover of an old Muddy Waters song. The fact that Byrne’s vocals deliberately mimicked John Lee Hooker just added to its overall strangeness.

But just as “I Zimbra” presaged Talking Heads’ foray into Afrofunk, “Swamp” foreshadowed the band’s turn toward American roots music. Their follow-up album, Little Creatures, showed the band branching out even further with the rollicking zydeco of “Road to Nowhere” and the soporific country weeper, “Creatures of Love.” All of this would eventually lead Byrne and co. to True Stories and to a state with a musical canvas almost as large as its geography: Texas.

More songs about voodoo and dreams

In the special features on Criterion’s excellent edition of True Stories, David Byrne acknowledges that his conception of the film was partly inspired by his admiration for Robert Altman’s Nashville. The resemblances between the two films aren’t hard to discern. Both films feature multiple protagonists and use setting to unify the film’s different plotlines. Both films include the perspectives of one or more outsiders — The Narrator in True Stories, Opal and John Triplette in Nashville — who serve as the viewer’s guide to the community each explores. Both films also involve preparations for a local celebration – the talent show, the political rally – to motivate musical numbers by a variety of performers, much in the manner of a revue or jukebox musical.

Texas is home to a distinctive mix of different kinds of “roots” music. Byrne was keen to capture that breadth. In an essay on the music written for True Stories, Byrne says, “I realized there was a lot to represent – rock, country, Tex-Mex, polkas, Latin, lounge jazz, disco, and some made-up genres, like an accordion marching band.” Trips to scout locations for the film brought Byrne into contact with a number of clubs and musicians. He then offered some local musicians an opportunity to contribute to the score. None of the groups represented is particularly well known outside of True Stories. Indeed, neither the Panhandle Mystery Band nor Brave Combo achieved even the modest fame accorded to Texas singers like Delbert McClinton or Freddy Fender. Still these local musicians definitely added to the “specialness” that Virgil represents.

In his collaborations with local musicians and the songs written for various actors to sing in True Stories, Byrne found himself serving two masters. On the one hand, Byrne wanted to pursue his vision for the film and to write songs that express the feelings and perspectives of various characters. On the other hand, though, Byrne also had to make sure these numbers still worked as Talking Heads tracks. It seems likely that Warner’s willingness to support the film depended upon the ancillary revenues they hoped to earn from the soundtrack. The Heads had been signed by Sire Records, a subsidiary of Warner Music. Given the band’s previous sales, a new Talking Heads album served as a hedge against the film’s disappointing box office.

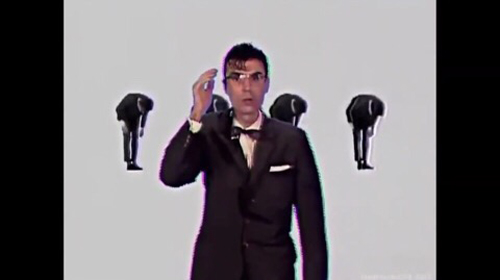

Virgil wants its MTV

The three songs Talking Heads recorded specifically for the film – “Wild, Wild Life,” “Love for Sale,” and “City of Dreams” — are perhaps the best illustration of Byrne’s need to create corporate “synergy” in the relationship between True Stories and its music ancillaries. All of them are foursquare rock and roll songs. No doubt they reassured Warner Bros. that they had commercially marketable singles that could generate radio airplay and hopefully drive traffic to movie theaters. “Wild, Wild Life” would become the second biggest hit in the band’s history, peaking at #25 and spending about five months on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart.

Notably, though, Byrne insisted these weren’t genuine Talking Heads records. Instead, they represented the band’s attempts to sound like other popular artists. Byrne described the role models for these tracks:

The closing song, “City of Dreams,” is my version of a Neil Young anthem. Its lyrics echo the history lesson at the beginning of the film. “Love for Sale” was our version of a Stooges song, and “Wild, Wild Life” was my attempt at writing a song like something one might hear on MTV at the time.

Byrne doesn’t give us a lot to go on here, but we can discern at least some similarities between the songs and the artists he cites. On “City of Dreams,” Byrne’s voice doesn’t have the fragility that Young’s “high lonesome” tenor conveys. But the lyrics evoke the kind of imagery found in some of Young’s most famous songs, especially those that relate the experience of Native Americans. Indeed, Byrne’s verse about the Spanish search for gold wouldn’t seem out of place in “Cortez the Killer,” the standout track on Young’s 1975 album Zuma.

With its crunchy guitar riff and drum break, “Love for Sale” at least nominally sounds like it could be a track from the Stooges’ Fun House. It certainly channels some of the proto-punk energy that made the Stooges, especially lead singer Iggy Pop, a revered cult band in the early seventies. Yet Talking Heads’ performance shows their customary clockwork precision, and the record generally lacks the kind of wild abandon that one associates with the Stooges’ best tracks. Eric Thorngren’s audio engineering of “Love for Sale” also adds a layer of studio polish that an album like Raw Power most pointedly refuses. In an odd way, the recording gives us some insight into how the Heads might have sounded had they been a punk band in their CBGB days.

Perhaps the bigger irony here is that the song functions as an interpolated music video watched by the Lazy Woman during a bout of channel surfing. It shows Byrne’s usual eye for inventiveness within the form: silhouettes, primary colors, and a surrealist arc in which each band member is molded into a chocolate figurine wrapped in foil. Yet here is where the similarity between the Heads and Stooges ends. Iggy Pop may have been known for pouring oil or honey on his body during Stooges concerts. But in 1986, the Stooges were about the last band one would expect to see on MTV.

“Wild, Wild Life” is motivated in a similar way. Heard in a Virgil dance club, much of the film’s cast lip syncs to it against a bank of video monitors. Like “Love for Sale,” this footage became the basis of a very successful music video promoting the film. In a bit of an in-joke, guitarist Jerry Harrison twice appears onscreen dressed as an iconic rival artist: first as Billy Idol, then as Prince. (Note that Tina Weymouth also appears with Harrison as a fetching Apollonia.) Still, the lack of specificity in Byrne’s description suggests that it was Talking Heads’ attempt to make a rather generic pop record. In contrast to the film’s celebration of “specialness,” Byrne’s explanation of the song’s purpose functions as a backhanded critique of MTV’s role as tastemaker. In trying to sound like everyone, “Wild, Wild Life” fit quite snugly into the music network’s video rotation.

The sage in bloom is like perfume

The film’s remaining songs are performed by characters. They illustrate Byrne’s desire to capture the breadth of Texas’ musical culture in a variety of idioms. Other bits of music are also interspersed between these numbers. There are snatches of nondiegetic score based on Byrne’s two “dream” songs (“City of Dreams” and “Dream Operator”). Meredith Monk contributed a brief minimalist theme that is featured in the film’s opening and closing scenes. It is perhaps the clearest reminder of Byrne’s outsider status, enveloping the film within the sounds of the downtown Manhattan arts scene. It also includes Carl Finch’s “Buster’s Theme” as music played during True Stories’ infamous accordion parade.

At least two songs evoke the swamp pop of Eastern Texas, which shares much of its sound with the music of New Orleans. “Hey Now” features the simple tonic/dominant changes and “call and response” strophic patterns heard in second line parades during Mardi Gras. Sung by children, it sounds like a modernized version of the Dixie Cups classic, “Iko Iko.”

“Papa Legba,” on the other hand, carries a more pronounced “island vibe,” conjuring the Cuban and Jamaican styles that were such an important influence on Dave Bartholomew, Fats Domino, and Lloyd Price. Performed by the great Pops Staples, the style is apt since the song is ostensibly an appeal to a central figure in Haitian folklore. (Legba is a demigod in voodoo culture who facilitates communication between living beings and the souls of the dead.) Staples expressed concern about this scene. The actions of his character, Mr. Tucker, ran squarely against the actor’s Christian faith. Yet, despite Staples’ literal embodiment of the “magic negro” trope, Tucker’s actions here come across as rather benign. He acts on Louis’ behalf, and both characters seem so decent and honest that their resort to sorcery seems quite harmless.

In other films and television shows, such as Crossroads or American Horror Story, Legba is often trotted out as a stand-in for Satan himself. In True Stories, though, Tucker’s Legba number is a slightly less hokey version of Leiber and Stoller’s “Love Potion # 9.”

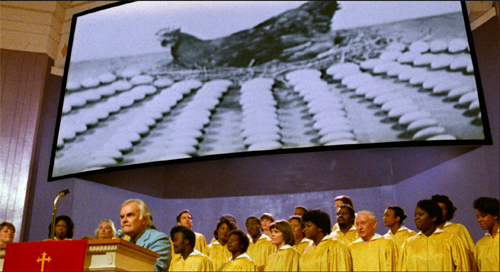

“Puzzling Evidence” is a straightforward gospel number, delivered from the pulpit by John Ingle as The Preacher. As an enumeration of possible conspiracies, the scene might seem today as QAnon avant la lettre. But sober reflection suggests the song is further evidence that Richard Hofstadter’s “paranoid style” of American politics has a long and rich history.

“Radio Head” represents the rich tradition of Hispanic styles in Texas musical culture: Tejano, conjunto, orquesta, mariachi, corrido. As performed by Tito Larriva, the tune borrows heavily from conjunto, which originated in the 1870s and fuses Spanish and Mexican vocal styles with the polkas, waltzes, and Mazurkas played by German and Czech immigrants. A central element of conjunto is the combination of 12-string guitars with button accordions. The latter has a distinctive reedy, yet sweet timbre contrasting that of the piano accordion.

“Dream Operator” and “People Like Us” round out Byrne’s portfolio by borrowing different from different strands of country music. The former is a shimmering waltz reminiscent of the Texas Troubador, Ernest Tubb, and the Western swing style of Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys. “People Like Us,” which is performed by Louis at the talent show, is an up-tempo slice of neo-honky tonk that features the requisite fiddle and steel guitars. The lyrics also voice the kinds of populist sentiment that became di rigeur in the genre by the 1980s.

At its best, in the music of Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard, George Jones, and Loretta Lynn, country music spoke eloquently of the simple pleasures of nature and family. It also explored the problems of ordinary folks, such as infidelity, divorce, and alcohol abuse. At its worst, though, such populism lapses into knee-jerk jingoism.

Byrne’s lyrics gesture toward the former of these two strains. It attests to certain Texas values: stubborn pride, an independent streak, and a resilience in hard times. Louis’ seeming humility and sincerity proves to be catnip for the Lazy Woman. She proffers the marriage proposal that Louis has sought throughout the film. In providing the resolution to the central plotline, “People Like Us” brings the narrative and Byrne’s musical journey through Texas to a fitting conclusion.

Changes in latitude, changes in attitude

For me, perhaps the most striking thing about “People Like Us” is its distance from Talking Heads’ early work. Compare it, for example, with “The Big Country,” the closing track on More Songs About Buildings and Food (below). Here Byrne’s narrator assumes a God-like view of the U.S. and its “people down there.” Imagined from maps and viewed from airplanes, the lyrics survey a cornucopia of Americana in the references to ball diamonds, whitecaps, farmlands, highways, and buildings. Yet, each chorus undercuts this encomium to the “big country” by concluding “I couldn’t live there if you paid me.”

In conversation David (Bordwell rather than Byrne) often praises “the spontaneous genius of the American people.” Is Byrne doing the same in True Stories with its portrait of small-town life as a mixture of performance art and irresistible kitsch? Or does he still occupy the previous Godlike position described in Louis’ song, laughing disdainfully at “people like us?”

At the end of the day, I think it is impossible to truly know. If we take Byrne at his word that his songs for True Stories aren’t Talking Heads songs, then there really isn’t a contradiction. He set out to write songs in the voices of his characters and in the style of musicians quite distinct from Talking Heads. Louis is not Byrne, and therefore “The Big Country” stands on its own as a wonderful, if contemptuous take on American life.

At the end of the day, I think it is impossible to truly know. If we take Byrne at his word that his songs for True Stories aren’t Talking Heads songs, then there really isn’t a contradiction. He set out to write songs in the voices of his characters and in the style of musicians quite distinct from Talking Heads. Louis is not Byrne, and therefore “The Big Country” stands on its own as a wonderful, if contemptuous take on American life.

Yet somehow invoking the old distinction between “author” and “narrator” obscures something important about the way True Stories fits into Talking Heads’ history as a band. The songs Byrne wrote for the film seem like a culmination of the group’s turn toward American roots music in the mid-1980s. Moreover, as Byrne has shown as an impresario for his own Luaka Bop label, he has genuine admiration for an enormous variety of vernacular pop idioms. In its own way, Talking Heads’ absorption of regional American musics on Little Creatures and True Stories might be viewed as signs of artistic growth rather than the stylistic poaching of smartasses from Manhattan.

Still there is a third possibility. As my colleague Jonah Horwitz pointed out to David and me, True Stories also seems to bear a strong relation to the Lovely Music movement epitomized by Robert Ashley, “Blue” Gene Tyranny, and Peter Gordon. In Jonah’s words, this axis of modern composition is “characterized by a suspension of judgement, gaping appreciatively at the banality/beauty of America and Americans, bridging the gap between structural/minimalist ‘new music’ and popular forms like rock and country music and soap opera.”

But is this appreciative gaping is really just postmodernist snark? Adrian Martin suggests as much in his original review of the film. And faux sincerity, in and of itself, might be viewed as the deepest, most pernicious form of cynicism. Taking particular issue with the chorus of “People Like Us,” Martin writes, “According to this reading, which the film abundantly invites, its viewpoint is immaculately distant and sneering.” Citing its “patronizing, condescending tone,” Martin ultimately bemoans the fact that True Stories draws attention away from more “authentically funky little American films” that won’t get seen.

Is this ultimately where Byrne lands? Perhaps. The lyrics certainly can be viewed as a faux naif expression of Redneck stupidity.

We don’t want freedom

We don’t want justice

We just want someone to love

But if we dismiss “People Like Us” as evidence of authorial condescension, one misses the key insight that the song has to offer. Much hedonics research suggests that there is a more complex way of understanding such sentiment.

Freedom and justice may be necessary conditions of human happiness, but they are hardly sufficient. Abstract ideals ultimately don’t mean much absent the human connections that define our workaday world. Such craving for social interaction and a feeling of belonging is one reason why respondents in hedonics studies claim they would forgo a $10,000 raise for the opportunity to become a member of a small, but active club. Moreover, neuroscience also shows that romantic love produces a sense of electrochemical wonder within the brain. Not all of these changes are positive ones, but the flood of dopamine that accompanies sexual attraction helps explain why love can be both pleasurable and addictive.

Viewed from this perspective, Louis’ sentiments in “People Like Us” are far from guileless. By emphasizing toughness and resilience, the song asserts that homeostasis is possible even in the most hardscrabble life. And life is made rewarding and meaningful by the social bonds that unite us in a common humanity. Perhaps folks out there will see me espousing a version of the feigned sincerity for which True Stories is equally guilty. But given the way Byrne’s film judders my own pleasure center…. Well, let’s just say I’ll proudly wear my heart on my sleeve.

Thanks to David Byrne, Ed Lachman, Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Lee Kline, Ryan Hullings, and the rest of the Criterion team for this edition. The quotation from David Byrne comes from the booklet accompanying the disc.

Thanks also to Jonah Horwitz for helpful comments on the music, and Adrian Martin for signaling his critique of True Stories.

Other work by Jeff relevant to this analysis includes The Sounds of Commerce: Marketing Popular Film Music (Columbia University Press, 1998) and his survey of the field ”The Tunes They are a-Changing’: Moments of Historical Rupture and Reconfiguration in the Production and Commerce of Music in Film,” in The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies, ed. David Neumeyer (Oxford University Press, 2013).

True Stories.

Is there a blog in this class? 2018

24 Frames (2017)

Kristin here:

David and I started this blog way back in 2006 largely as a way to offer teachers who use Film Art: An Introduction supplementary material that might tie in with the book. It immediately became something more informal, as we wrote about topics that interested us and events in our lives, like campus visits by filmmakers and festivals we attended. Few of the entries actually relate explicitly to the content of Film Art, and yet many of them might be relevant.

Every year shortly before the autumn semester begins, we offer this list of suggestions of posts that might be useful in classes, either as assignments or recommendations. Those who aren’t teaching or being taught might find the following round-up a handy way of catching up with entries they might have missed. After all, we are pushing 900 posts, and despite our excellent search engine and many categories of tags, a little guidance through this flood of texts and images might be useful to some.

This list starts after last August’s post. For past lists, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017.

This year for the first time I’ll be including the video pieces that our collaborator Jeff Smith and we have since November, 2016, been posting monthly on the Criterion Channel of the streaming service FilmStruck. In them we briefly discuss (most run around 10 to 14 minutes) topics relating to movies streaming on FilmStruck. For teachers whose school subscribes to FilmStruck there is the possibility of showing them in classes. The series of videos is also called “Observations on Film Art,” because it was in a way conceived as an extension of this blog, though it’s more closely keyed to topics discussed in Film Art. As of now there are 21 videos available, with more in the can. I won’t put in a link for each individual entry, but you can find a complete index of our videos here. Since I didn’t include our early entries in my 2017 round-up, I’ll do so here.

As always, I’ll go chapter by chapter, with a few items at the end that don’t fit in but might be useful.

[July 21, 2019: In late November, 2018, the Filmstruck streaming service ceased operation. On April 8, 2019, it was replaced by The Criterion Channel, the streaming service of The Criterion Collection. All the Filmstruck videos listed below appear, with the same titles and numbers, in the “Observations on Film Art” series on the new service. Teachers are welcome to stream these for their classes with a subscription.]

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

David writes on the persistence of classical Hollywood storytelling in contemporary films: “Everything new is old again: Stories from 2017.”

In FilmStruck #5, I look at the effects of using a child as one of the main point-of-view figures in Victor Erice’s masterpiece: “The Spirit of the Beehive–A Child’s Point of View”

In FilmStruck #13, I deal with “Flashbacks in The Phantom Carriage.”

FilmStruck #14 features David discussing classical narrative structure in “Girl Shy—Harold Lloyd Meets Classical Hollywood.” His blog entry, “The Boy’s life: Harold Lloyd’s GIRL SHY on the Criterion Channel” elaborates on Lloyd’s move from simple slapstick into classical filmmaking in his early features. (It could also be used in relation to acting in Chapter 4.)

In FilmStruck #17, David examines “Narrative Symmetry in Chungking Express.”

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-Scene

In choosing films for our FilmStruck videos, we try occasionally to highlight little-known titles that deserve a lot more attention. In FilmStruck #16 I looks at the unusual lighting in Raymond Bernard’s early 1930s classic: “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses.”

FilmStruck #3: Abbas Kiarostami is noted for his expressive use of landscapes. I examine that aspect of his style in Where Is My Friend’s Home? and The Taste of Cherry: “Abbas Kiarostami–The Character of Landscape, the Landscape of Character.”

Teachers often request more on acting. Performances are difficult to analyze, but being able to use multiple clips helps lot. David has taken advantage of that three times so far.

In FilmStruck #4, “The Restrain of L’avventura,” he looks at how staging helps create the enigmatic quality of Antonionni’s narrative.

In FilmStruck #7, I deal with Renoir’s complex orchestration of action in depth: “Staging in The Rules of the Game.”

FilmStruck #10, features David on details of acting: “Performance in Brute Force.”

In Filmstruck #18, David analyses performance style: “Staging and Performance in Ivan the Terrible Part II.” He expands on it in “Eisenstein makes a scene: IVAN THE TERRIBLE Part 2 on the Criterion Channel.”

FilmStruck #19, by me, examines the narrative functions of “Color Motifs in Black Narcissus.”

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

A basic function of cinematography is framing–choosing a camera setup, deciding what to include or exclude from the shot. David discusses Lubitsch’s cunning play with framing in Rosita and Lady Windermere’s Fan in “Lubitsch redoes Lubitsch.”

In FilmStruck #6, Jeff shows how cinematography creates parallelism: “Camera Movement in Three Colors: Red.”

In FilmStruck 21 Jeff looks at a very different use of the camera: “The Restless Cinematography of Breaking the Waves.”

Chapter 6 The Relation of Shot to Shot: Editing

David on multiple-camera shooting and its effects on editing in an early Frank Capra sound film: “The quietest talkie: THE DONOVAN AFFAIR (1929).”

In Filmstruck #2, David discusses Kurosawa’s fast cutting in “Quicker Than the Eye—Editing in Sanjuro Sugata.”

In FilmStruck #20 Jeff lays out “Continuity Editing in The Devil and Daniel Webster.” He follows up on it with a blog entry: “FilmStruck goes to THE DEVIL”,

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

In 2017, we were lucky enough to see the premiere of the restored print of Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) at the Venice International Film Festival in 2017. My entry “Lubitsch and Pickford, finally together again,” gives some sense of the complexities of reconstructing the original musical score for the film.

In FilmStruck #1, Jeff Smith discusses “Musical Motifs in Foreign Correspondent.”

Filmstruck #8 features Jeff explaining Chabrol’s use of “Offscreen Sound in La cérémonie.”

In FilmStruck #11, I discuss Fritz Lang’s extraordinary facility with the new sound technology in his first talkie: “Mastering a New Medium—Sound in M.”

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

David analyzes narrative patterning and lighting Casablanca in “You must remember this, even though I sort of didn’t.”

In FilmStruck #10, Jeff examines how Fassbender’s style helps accentuate social divisions: “The Stripped-Down Style of Ali Fear Eats the Soul.”

Chapter 9 Film Genres

David tackles a subset of the crime genre in “One last big job: How heist movies tell their stories.”

He also discusses a subset of the thriller genre in “The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt.”

FilmStruck #9 has David exploring Chaplin’s departures from the conventions of his familiar comedies of the past to get serious in Monsieur Verdoux: “Chaplin’s Comedy of Murders.” He followed up with a blog entry, “MONSIEUR VERDOUX: Lethal Lothario.”

In Filmstruck entry #15, “Genre Play in The Player,” Jeff discusses the conventions of two genres, the crime thriller and movies about Hollywood filmmaking, in Robert Altman’s film. He elaborates on his analysis in his blog entry, “Who got played?”

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

I analyse Bill Morrison’s documentary on the history of Dawson City, where a cache of lost silent films was discovered, in “Bill Morrison’s lyrical tale of loss, destruction and (sometimes) recovery.”

David takes a close look at Abbas Kiarostami’s experimental final film in “Barely moving pictures: Kiarostami’s 24 FRAMES.”

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

We blogged from the Venice International Film Festival last year, offering analyses of some of the films we saw. These are much shorter than the ones in Chapter 11, but they show how even a brief report (of the type students might be assigned to write) can go beyond description and quick evaluation.

The first entry deals with the world premieres of The Shape of Water and Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri and is based on single viewings. The second was based on two viewings of Argentine director Lucretia Martel’s marvelous and complex Zama. The third covers films by three major Asian directors: Kore-eda Hirokazu, John Woo, and Takeshi Kitano.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

My usual list of the ten best films of 90 years ago deals with great classics from 1927, some famous, some not so much so.

David discusses stylistic conventions and inventions in some rare 1910s American films in “Something familiar, something peculiar, something for everyone: The 1910s tonight.”

I give a rundown on the restoration of a silent Hollywood classic long available only in a truncated version: The Lost World (1925).

In teaching modern Hollywood and especially superhero blockbusters like Thor Ragnarok, my “Taika Waititi: The very model of a modern movie-maker” might prove useful.

Etc.

If you’re planning to show a film by Damien Chazelle in your class, for whatever chapter, David provides a run-down of his career and comments on his feature films in “New colors to sing: Damien Chazelle on films and filmmaking.” This complements entries from last year on La La Land: “How LA LA LAND is made” and “Singin’ in the sun,” a guest post featuring discussion by Kelley Conway, Eric Dienstfrey, and Amanda McQueen.

Our blog is not just of use for Film Art, of course. It contains a lot about film history that could be useful in teaching with our other textbook. In particular, this past year saw the publication of David’s Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Hollywood Storytelling. His entry “REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD: Out of the past” discusses how it was written, and several entries, recent and older, bear on the book’s arguments. See the category “1940s Hollywood.”