Archive for the 'Film technique: Performance' Category

Picturing performance: THEATRE TO CINEMA comes to the Net

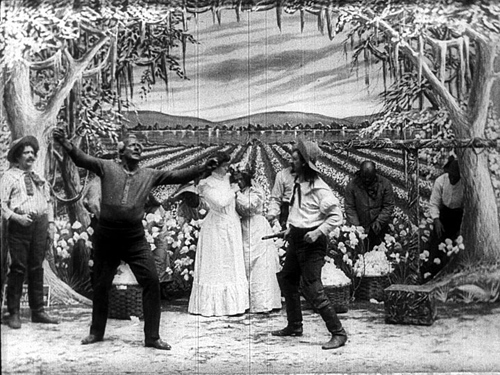

Ma l’amor mio non muore! (aka Love Everlasting, 1913). Lyda Borelli.

DB here:

The core of cinematic expression is editing. Since the 1920s, that view has been part of the lore of film aesthetics. Editing, people said, is what distinguishes film from other media. After all, the single shot is both a picture (like a painting) and a dramatization (like a scene in a stage play). But put one shot with another and you’ve got a technique impossible to parallel in other media.

But if we look closely, we find that the film image is as “uniquely cinematic” as editing. After all, a film is an image, but it’s a moving image, which is sharply different from a painting. And although a shot is a dramatization, it’s two-dimensional (unlike a stage scene) and the space it captures is quite different from that of the theatre. Anyhow, maybe editing isn’t uniquely cinematic. Comic strips juxtapose discrete images, and some forms of theatre (such as pageants, or turntable stages) can shift rapidly between scenes. Once we start to compare adjacent media, we find many overlaps in their expressive resources.

Why did early film theorists make editing so important? They were often defending the view that film was a new art, in the teeth of opponents who claimed that it was simply photographed theatre. Accordingly, film’s defenders looked for features of films that seemed to have no counterpart in theatre, such as the close-up and, more pervasively, editing.

Since then, we’ve come a long way in our understanding of film’s artistic capabilities. Filmmakers, particularly those in the early sound era (Renoir, Ophuls, Dreyer, Mizoguchi), showed the expressive power of the single shot. This tendency was amplified in the 1950s and 1960s with Antonioni, Jancso, Andy Warhol, and many other directors. Now nobody blinks if a filmmaker like Hou or Yang presents a lengthy, unedited sequence.

Informed by what’s possible in the single shot, we ought to find the earliest filmmakers using the resources of staging, composition, and performance in felicitous ways. So we do. Once we foreswear the cult of the cut, we can see that early cinema made extensive use of cinematography and mise-en-scene for powerful artistic effects. And conceding that, we suddenly find ourselves back in the lap of the other arts–painting and theatre.

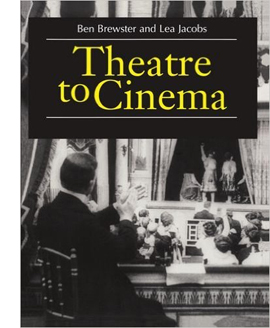

Living pictures

No one has done more to clarify the debt of early cinema to theatre than our colleagues Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs. In the spirit of Wisconsin Revisionism, they have embraced early film’s stagy side. They’ve taught us to appreciate the ways in which dramaturgy and performance of 1910s cinema derive, in unexpected ways, from the theatre. Their trailblazing book Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film (Oxford, 1997) showed how to appreciate early films in a whole new way: by seeing them as borrowing and modifying conventions of the stage. What may look artificial or backward to us were actually tools of subtle, supple expression.

No one has done more to clarify the debt of early cinema to theatre than our colleagues Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs. In the spirit of Wisconsin Revisionism, they have embraced early film’s stagy side. They’ve taught us to appreciate the ways in which dramaturgy and performance of 1910s cinema derive, in unexpected ways, from the theatre. Their trailblazing book Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film (Oxford, 1997) showed how to appreciate early films in a whole new way: by seeing them as borrowing and modifying conventions of the stage. What may look artificial or backward to us were actually tools of subtle, supple expression.

Here’s the authors’ statement of the book’s argument:

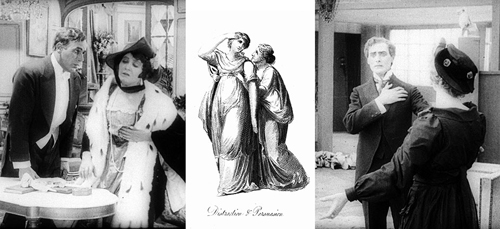

While previous accounts of the relationship between cinema and theatre have tended to assume that early filmmakers had to break away from the stage in order to establish a specific aesthetic for the new medium, Theatre to Cinema argues that the cinema turned to the pictorial, spectacular tradition of the theatre in the 1910s to establish a model for feature filmmaking. The book traces this influence in the adaptation and transformation of the theatrical tableau, acting styles, and staging techniques, examining such films as Caserini’s Ma ľamor mio non muore!, Tourneur’s Alias Jimmy Valentine and The Whip, Sjöström’s Ingmarssönerna, and various adaptations of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

The twist here is that turn-of-the-century artistic culture had already blurred the boundaries between theatre and painting. Painters drew upon the stock gestures and poses of the stage, while plays presented vivid visual effects that were indebted to painting. The term “tableau,” referring at once to a picture and a poised stage image, captures this convergence between the media. That’s why Ben and Lea refer to “stage pictorialism” as the nexus of their inquiry.

Thanks to their research, we can see the unbroken long- or medium-shot of early features as permitting a complex choreography of facial expressions and bodily attitudes, which were in turn indebted to both pictorial and dramatic traditions. Standard gestures were summoned up and reworked to suit dramatic situations–as, for example, clutching.

When we do find editing or camera movements in these films, they’re often at the service of the performance style. Ben and Lea powerfully make the case that the expressive human body was at the center of storytelling in the first years of silent cinema. (If nothing else, the book is an in-depth analysis of diva acting from the likes of Lyda Borelli and Asta Nielsen.) By studying the history of theatre, we can learn to appreciate aspects of acting that might otherwise escape our notice.

Theatre to cinema to pixels

Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Slavery Days (Edison, 1903).

How, you’re asking, can you gain access to the ideas and information and images in this fine book? It’s now criminally easy.

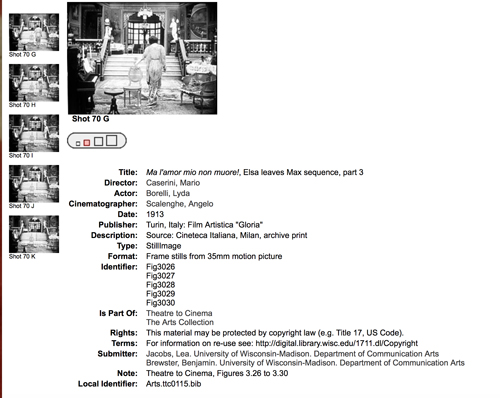

When Theatre to Cinema was published, all the illustrations came from 35mm film prints. Those originals were gorgeous. But in some printings of the book the stills came out badly, and when the book moved to print-on-demand status, the images suffered even more. A couple years ago, Ben and Lea rescued their book and took the opportunity to make a digital version. It’s unrevised, largely because updating a twenty-year-old volume would be a major overhaul, but errors have been corrected and–very important–the stills have been much improved.

Start here, with the introduction to the project. You can download the new edition of the whole book, section by section, here.

Naturally, Kristin and I are sympathetic to this effort. Since we started our website back in 2000, we have explored ways to amplify and extend our ideas by means of the web. In the beginning, and inspired by Philip Steadman’s Net-based supplements to his excellent Vermeer’s Camera, I added material that would enhance arguments I made in Figures Traced in Light. Then we set up our blog, now in its tenth year. Over the same period, we posted web essays, as you can see in serried ranks page left. We also used the site to preserve older material, such as film analyses dropped from editions of Film Art: An Introduction and even entire books, as in Kristin’s 1985 monograph Exporting Entertainment. We’ve mounted video lectures. And we’ve produced a new edition of an older book, Planet Hong Kong 2.0, and original e-books such as Pandora’s Digital Box and Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages.

Ben and Lea have found another way to expand a book’s Web life. They have put Theatre to Cinema at the heart of a digital collection sponsored by the University of Wisconsin–Madison Libraries. Here’s what they offer:

In this collection, we try to supplement the description and illustration that accompanied the book in a way that makes it easier for readers to appropriate our work—both to understand it, and to make use of it in research and teaching. What were illustrations in the pages of the book are also presented here as better-quality downloadable images.

For example, you can pick a still, find its mates in a single display, and blow it up for scrutiny. If you want import it into your own files, you may choose among four different file sizes.

The provenance of each still is provided, so scholars can compare prints from different sources. In addition, there’s a master index of the visual documentation, in sequential groupings across the book.

Finally, Ben and Lea plan to add video extracts from some of the films they discuss. When those go up, we’ll announce it here.

Every admirer of silent film, and everyone who studies the interrelationship of the arts, should read this book. Hard copies are still being sold online, but they’re apt to be versions with weakly reproduced stills. Get one if you want, because a book is a good object to have in hand. In addition, for free, you can own a beautiful, searchable edition with superb stills. I think you need both.

The digital collections set up by UW Libraries are breathtaking. Check them out here.

Some entries on our site intersect with Ben and Lea’s research. See the category Tableau staging.

Weisse Rosen (White Roses, 1915). Asta Nielsen.

Off-center 2: This one in the corner pocket

DB here, again:

We got a keen response to my entry on widescreen composition in Mad Max: Fury Road. Thanks! So it seemed worthwhile to look at composition in the older format of 4:3, good old 1.33:1–or rather, in sound cinema, 1.37: 1.

The problem for filmmakers in CinemaScope and other very wide processes is handling human bodies in conversations and other encounters (such as stomping somebody’s butt in an an action scene). You can more or less center the figures, and have all that extra space wasted. Or you can find ways to spread them out across the frame, which can lead to problems of guiding the viewer’s eye to the main points. If humans were lizards or Chevy Impalas, our bodies would fit the frame nicely, but as mostly vertical creatures, we aren’t well suited for the wide format. I suppose that’s why a lot of painted and photographed portraits are vertical.

By contrast, the squarer 4:3 frame is pretty well-suited to the human body. Since feet and legs aren’t usually as expressive as the upper part of the body, you can exclude the lower reaches and fit the rest of the torso snugly into the rectangle. That way you can get a lot of mileage out of faces, hands and arms. The classic filmmakers, I think, found ingenious ways to quietly and gracefully fill the frame while letting the actors act with body parts.

Since I’m watching (and rewatching) a fair number of Forties films these days, I’ll draw most of my examples from them. after a brief glance backward. I hope to suggest some creative choices that filmmakers might consider today, even though nearly everybody works in ratios wider than 4:3. I’ll also remind us that although the central area of the frame remains crucial, shifts away from it and back to it can yield a powerful pictorial dynamism.

Movies on the margins

Early years of silent cinema often featured bright, edge-to-edge imagery, and occasionally filmmakers put important story elements on the sides or in the corners. Louis Feuillade wasn’t hesitant about yanking our attention to an upper corner when a bell summons Moche in Fantômas (1913). A famous scene in Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912) shows Griffith trying something trickier. He divides our attention by having the Snapper Kid’s puff of cigarette smoke burst into the frame just as the rival gangster is doping the Little Lady’s drink. She doesn’t notice either event, as she’s distracted by the picture the thug has shown her, but there’s a chance we miss the doping because of the abrupt entry of the smoke.

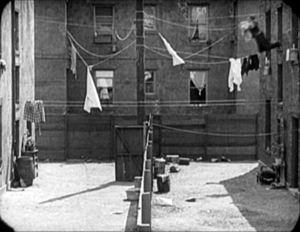

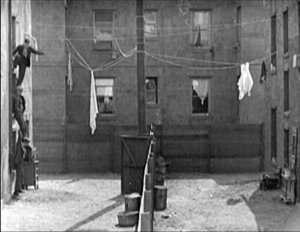

In Keaton’s maniacally geometrical Neighbors (1920), the backyard scenes make bold (and hilarious) use of the upper zones. Buster and the woman he loves try to communicate three floors up. Early on we see him leaning on the fence pining for her, while she stands on the balcony in the upper right. Later, he’ll escape from her house on a clothesline stretched across the yard. At the climax, he stacks up two friends to carry him up to her window.

Thankfully, the Keaton set from Masters of Cinema preserves some of the full original frames, complete with the curved corners seen up top. It’s also important to appreciate that in those days there was no reflex viewing, and so the DP couldn’t see exactly what the lens was getting. Framing these complex compositions required delicate judgment and plenty of experience.

Later filmmakers mostly stayed away from corners and edges. You couldn’t be sure that things put there would register on different image platforms. When films were destined chiefly for theatres, you couldn’t be absolutely sure that local screens would be masked correctly. Many projectors had a hot spot as well, rendering off-center items less bright. And any film transferred to 16mm (a strong market from the 1920s on) might be cropped somewhat. Accordingly, one trend in 1920s and 1930s cinematography was to darken the sides and edges a bit, acknowledging that the brighter central zone was more worth concentrating on.

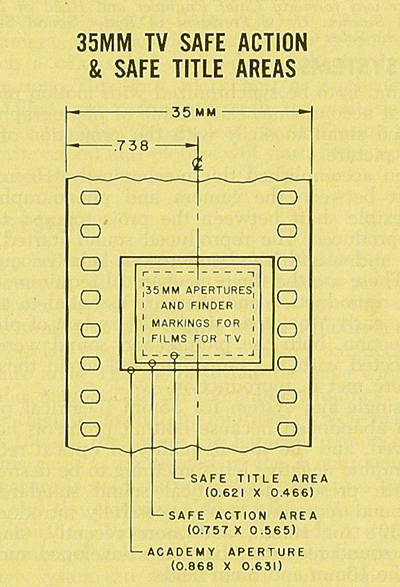

That tactic came in handy with the emergence of television, which established a “safe area” within the film frame for video transmission. TV cropped films quite considerably; cinematographers were advised in 1950 that

All main action should be held within about two-thirds of the picture. This prevents cut-off and tube edge distortion in television home receivers.

Older readers will remember how small and bulging those early CRT screens were.

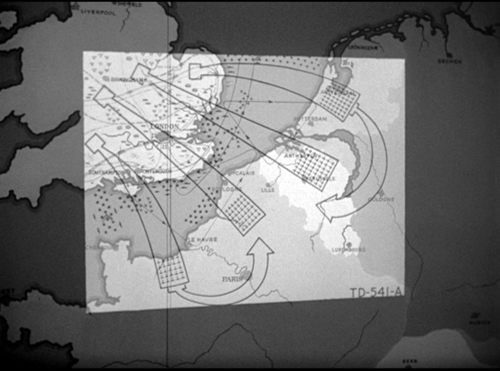

By 1960, when it was evident that most films would eventually appear on TV, DP’s and engineers established the “safe areas” for both titles and story action. (See diagram surmounting this section.) Within the camera’s aperture area, which wouldn’t be fully shown on screen, the safe action area determined what would be seen in 35mm projection. “All significant action should take place within this portion of the frame,” says the American Cinematographer Manual.

Studio contracts required that TV screenings had to retain all credit titles, without chopping off anything. This is why credit sequences of widescreen films appear in widescreen even in cropped prints. So the safe title area was marked as what would be seen on a standard home TV monitor. If you do the math, the safe title area is indeed 67.7 % of the safe action area.

These framing constraints, etched on camera viewfinders, would certainly inhibit filmmakers from framing on the edges or the corners of the film shot. And when we see video versions of films from the 1.37 era (and frames like mine coming up) we have to recall that there was a bit more all around the edges than we have now.

All-over framing, and acting

Yet before TV, filmmakers in the 40s did exploit off-center zones in various ways. Often the tactic involved actors’ hands–crucial performance tools that become compositional factors. In His Girl Friday (1940), Walter Burns commands his frame centrally, yet when he makes his imperious gesture (“Get out!”) Hawks and DP Joseph Walker (genius) have left just enough room for the left arm to strike a new diagonal.

The framing of a long take in The Walls of Jericho (1948) lets Kirk Douglas steal a scene from Linda Darnell. As she pumps him for information, his hand sneaks out of frame to snatch bits of food from the buffet.

As the camera backs up, John Stahl and Arthur Miller (another genius) give us a chance to watch Kirk’s fingers hovering over the buffet. When Linda stops him with a frown, he shrugs, so to speak, with his hands. (A nice little piece of hand jive.)

The urge to work off-center is still more evident in films that exploit vigorous depth staging and deep-focus cinematography. Dynamic depth was a hallmark of 1940s American studio cinematography. If you’re going to have a strong foreground, you will probably put that element off to one side and balance it with something further back. This tendency is likely to empty out the geometrical center of the shot, especially if only two characters are involved. In addition, 1940s depth techniques often relied on high or low angles, and these framings are likely to make corner areas more significant. Here are examples from My Foolish Heart (1950): a big-head foreground typical of the period, and a slightly high angle that yields a diagonal composition.

Things can get pretty baroque. For Another Part of the Forest (1948), a prequel to The Little Foxes (1941), Michael Gordon carried Wyler’s depth style somewhat further. The Hubbard mansion has a huge terrace and a big parlor. Using the very top and very bottom of the frame, a sort of Advent-calendar framing allows Gordon to chart Ben’s hostile takeover of the household, replacing the patriarch Marcus at the climax. The fearsome Regina appears in the upper right window of the first frame, the lower doorway of the second.

In group scenes, several Forties directors like to crowd in faces, arms, and hands, all spread out in depth. I’ve analyzed this tendency in Panic in the Streets (1950), but we see it in Another Part of the Forest too. Again, character movement can reveal peripheral elements of the drama.

At the dinner, Birdie innocently thanks Ben for trying to help her family with their money problems and bolts from the room, going out behind Ben’s back. The reframing brings in at the left margin a minor character, a musician hired to entertain for the evening. But in a later phase of the scene he will–still in the distance–protest Marcus’s cruelty, so this shot primes him for his future role.

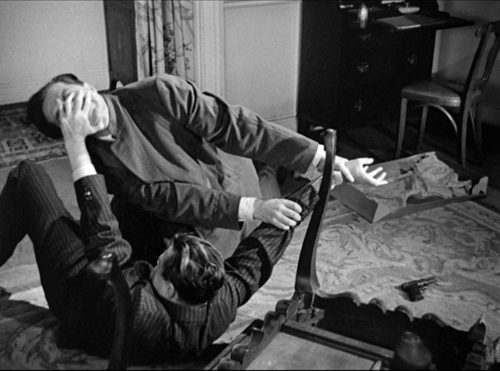

At one high point, the center area is emptied out boldly and the corners get a real workout. On the staircase, the callow son Oscar begs Marcus for money to enable him to run off with his girlfriend. (As in Little Foxes, the family staircase is very important–as it is in Lillian Hellman’s original plays.) Ben watches warily from the bottom frame edge. Nobody occupies the geomentrical center.

Later, on the same staircase, Ben steps up to confront his father while Regina approaches. It’s an odd confrontation, though, because Ben is perched in the left corner, mostly turned from us and handily edge-lit. Marcus turns, jammed into the upper right. Goaded by Ben’s taunts, he slaps Ben hard. Here’s the brief extract.

The key action takes place on the fringes of the frame, while the lower center is saved for Regina’s reaction–for once, a more or less normal human one. Even allowing for the cropping induced by the video safe-title area, this is pretty intense staging.

The corners can be activated in less flagrant ways. Take this scene from My Foolish Heart. Eloise has learned that her lover has been killed in air maneuvers. Pregnant but unmarried, she goes to a dance, where an old flame, Lew asks her to go on a drive. They park by the ocean, and she succumbs to him. Here’s the sequence as directed by Mark Robson and shot by Lee Garmes (another genius).

In the fairly conventional shot/ reverse-shot, the lower left corner is primed by Eloise’s looking down at the water and Lew’s hand stealing around her.

Later, when Lew pulls her close, (a) we can’t see her; (b) his expression doesn’t change and is only partly visible; so that (c) his emotion is registered by the passionate twist of his grip on her shoulder. Lew’s hand comes out from the corner pocket.

Perhaps Eloise is recalling another piece of hand jive, this time from her lost love.

For many directors, then, every zone of the screen could be used, thanks to the good old 4:3 ratio. It’s body-friendly, human-sized, and can be packed with action, big or small.

Mabuse directs

In other entries (here and here) I’ve mentioned one of the supreme masters of off-center framing, Fritz Lang. Superimpose these two frames and watch Kriemhilde point to the atomic apple in Cloak and Dagger (1946).

From the very start of Ministry of Fear (1944), the visual field comes alive with pouches, crannies, and bolt-holes. The first image of the film is a clock, but when the credits end the camera pulls back and tucks it into the corner as the asylum superintendant enters. (The shot is at the end of today’s entry.) Here and elsewhere, Lang uses slight high angles to create diagonals and corner-based compositions.

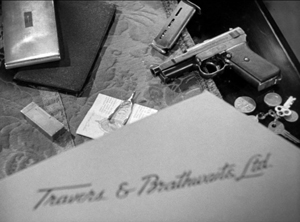

In the course of the film, pistols circulate. Neale lifts one from Mrs. Bellane (strongly primed, upper left), keeps her from appropriating it (lower center), and secures it nuzzling his left knee (lower right).

Later, Neale’s POV primes the placement of a pistol on the desktop (naturally, off-center), so that we’re trained to spot it in a more distant shot, perilously close to the hand of the treacherous Willi.

Amid so many through-composed frames, an abrupt reframing calls us to attention. Unlike Hawks and Walker’s handling of Walter in His Girl Friday, Lang and his DP Henry Sharp (great name for a DP, like Theodore Sparkuhl and Frank Planer) gives things a sharp snap when Willi raises his hand.

Lang drew all his images in advance himself, not trusting the task to a storyboarder. Avoiding the flashy deep-focus of Wyler and company, he created a sober pictorial flow that can calmly swirl information into any area of the frame. It’s hard not to see the stolen attack maps, surmounting today’s entry, as laying bare Lang’s centripetal vectors of movement. No wonder in the second frame up top, as Willi and Neale struggle in a wrenching diagonal mimicking the map’s arrows, that damn pistol strays off on its own.

Sometimes film technology improves over time. For instance, digital cinema today is better in many respects than it was in 1999. But not all changes are for the better. The arrival of widescreen cinema was also a loss. Changing the proportions of the frame blocked some of the creative options that had been explored in the 4:3 format. Occasionally, those options could be modified for CinemaScope and other wide-image formats; I trace some examples in this video lecture. But the open-sided framings in most widescreen films today suggest that most filmmakers haven’t explored the wide format to the degree that classical directors did with the squarish one.

More generally, it’s worth remembering that the film frame is a basic tool, creating not only a window on a three-dimensional scene but also a two-dimensional surface that requires composition–either standardized or more novel. Instead of being a dead-on target, the center can be an axis around which pictorial forces push and pull, drift away and bounce around. After all, we’re talking about moving pictures.

Thanks to Paul Rayton, movie tech guru, for information on 16mm cropping.

My image of the safe areas and the second quotation about them is taken from American Cinematographer Manual 1st ed., ed. Joseph C. Mascelli (Hollywood: ASC, 1960), 329-331. The older quotation about cropping for television comes from American Cinematographer Handbook and Reference Guide 7th ed., ed. Jackson J. Rose (Hollywood: ASC, 1950), 210.

I hope you noticed that I admirably refrained from quoting Lang, who famously said that CinemaScope was good only for…well, you can finish it. Of course he says it in Godard’s Contempt (1963), but he told Peter Bogdanovich that he agreed.

[In ‘Scope] it was very hard to show somebody standing at a table, because either you couldn’t show the table or the person had to be back too far. And you had empty spaces on both sides which you had to fill with something. When you have two people you can fill it up with walking around, taking something someplace, so on. But when you have only one person, there’s a big head and right and left you have nothing (Who the Devil Made It (Knopf, 1997), 224).

For more on the stylistics and technology of depth in 1940s American film, see The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (Columbia University Press, 1985), which Kristin and I wrote with Janet Staiger, Chapter 27, and my On the History of Film Style (Harvard University Press, 1997), Chapter 6. Many blog entries on this site are relevant to today’s post; search “deep-focus cinematography” and “depth staging.” If you want just one for a quick summary, try “Problems, problems: Wyler’s workarounds.” Some of the issues discussed here, about densely packing the frame, are considered more generally in “You are my density,” which includes an analysis of a scene in Lang’s Hangmen Also Die (1943).

Ministry of Fear (1944).

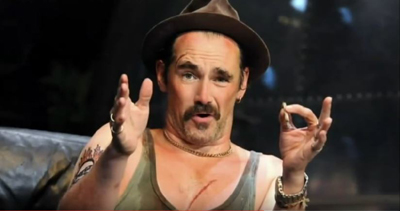

Mark Rylance, man of mystery

Kristin here:

I asked Rylance, a most certain Best Supporting Actor nominee, if success would spoil him now. He had a good retort: “I thought I was successful already!” Indeed, he sure is. But Hollywood will embrace him.

Will it? Well, it can try. It should try.

SPOILERS for Bridge of Spies ahead.

Another great veteran actor who came out of “nowhere”

Upon reading the reviews of Steven Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies published over the past few weeks, many American moviegoers may have been puzzled by the fact that one of the most highly praised elements of the film was the supporting performance of Mark Rylance. Indeed, the praise was often unusually enthusiastic, with Rylance already considered a favorite for a supporting actor Oscar nomination or even win. I suspect that the vast majority of Americans have never heard of Mark Rylance, three-time Tony winner, two-time Olivier-award winner, Emmy nominee, etc. He fits the cliché of the “overnight success” who has been around for a long time and was, as he says, “successful already.”

In Bridge of Spies, Tom Hanks plays the lead, real-life lawyer James Donovan. In the late 1950s, Donovan accepted the unpopular job of defending a Russian spy, Rudolph Abel (played by Rylance), when he came to trial. Later he agreed to negotiate with the Soviet government to swap Abel for downed American pilot and spy Francis Gary Powers. Bridge of Spies is not one of Spielberg’s most exciting or endearing films, but it’s very well made and as classical in its traits as a film can be. It sits nicely beside his other historical dramas, Lincoln and the excellent Munich. On the whole the film has been well-reviewed, with a 92% favorable rating from all critics on Rotten Tomatoes, increasing to 98% among top critics. Rylance is clearly a major reason for the excitement.

It’s Rylance who keeps Bridge of Spies standing. He gives a teeny, witty, fabulously non-emotive performance, every line musical and slightly ironic — the irony being his forthright refusal to deceive in a world founded on lies. (David Edelstein)

Because this is Hanks we’re dealing with, audiences know what to expect, though the revelation here is Rylance (an actor Spielberg also cast as his forthcoming BFG), who appears utterly transformed — to the few who recognize his typically charismatic screen presence — into a balding, Eeyore-like gray moth of a man. (Peter Debruge; the reference is to Spielberg’s The BFG, with Rylance in the lead as the Big Friendly Giant, based on the Roald Dahl children’s novel and now in post-production)

Rylance, one of the greatest of contemporary stage actors, has to date had only an intermittent screen career, but Bridge of Spies suggests that could be about to change. He brings fascination and very, very subtle comic touches to a man who has made every effort to appear as bland, even invisible, as possible. (Todd McCarthy)

Brilliantly played by British theater legend Mark Rylance — who nearly steals the show. (Lou Lumenick)

Meanwhile, Rylance, who’s still probably best known for his brilliant work on stage, is the film’s real breakout discovery. With his musical Northern English accent and bemused, ironic demeanor, he turns a story that could feel as musty as a yellowed stack of old newspapers snap to exuberant life. (Chris Nashawaty)

Mark Rylance, the great English actor, director, and playwright who for a decade was the artistic director of Shakespeare’s Globe theater, performs some mysterious act of alchemy in his role as the ineffable and unflappable Soviet spy. Almost without speaking a word, he communicates this character’s rich inner life, in which a near-Buddhist resignation to the whims of fate alternates with a feisty instinct for self-preservation. (Dana Stevens)

Part of the reason why the Germany sequences sag is that they don’t feature Abel, who is played by British actor Mark Rylance in what, with luck, will be a career-making performance. Many viewers may not have heard of Rylance, who recently played Thomas Cromwell in “Wolf Hall” on PBS. But his work in “Bridge of Spies” deserves to be widely recognized as an example of screen acting at its most subtle, poignant and exquisitely calibrated. (Ann Hornaday, who, like Friedman, does not acknowledge that Rylance already had made quite a career for himself)

I could go on, but for more see the reviews by Manohla Dargis, Richard Roeper, Kenneth Turan, and Michael Phillips.

I don’t, in fact, think that the German sequences sag. Basically the first half of the film covers the trial and sentencing of Abel, with brief scenes of Powers’ training for his spying missions flying over Soviet territory. Once Powers is shot down, Donovan goes to East Berlin for the negotiations, leaving Abel behind in prison.

The German sequences involve a marvelously authentic post-war East Berlin, designed by Adam Stockhausen, who won an Oscar for the production design of The Grand Budapest Hotel. (I wasn’t there in the early 1960s, of course, but I did visit East Berlin in 1992, when part of the wall was still up and the place had a very Soviet look, complete with giant busts of Marx and Engels.)

No, these scenes don’t sag, but there is definitely a niggling question in the back of one’s mind: When are we going to see Abel again? Rylance somehow makes this very ordinary-looking, quiet man the heart of some of the film’s best scenes.

Treading the boards

As Rylance pointed out in the quotation at the top of this entry, he already had an illustrious career going long before Wolf Hall and Bridge of Spies hit American screens. (The Wikipedia entry on Rylance  gives helpful biographical information as well as separate lists of his stage, film, and television performances and the nominations and awards resulting from each.) From 1995 to 2005, he was the first Artistic Director of the Globe Theatre, the replica of the original Elizabethan-period theatre in which many of Shakespeare’s plays premiered. He starred in a number of its Shakespeare productions, including some with authentic all-male casts and period costumes and staging.

gives helpful biographical information as well as separate lists of his stage, film, and television performances and the nominations and awards resulting from each.) From 1995 to 2005, he was the first Artistic Director of the Globe Theatre, the replica of the original Elizabethan-period theatre in which many of Shakespeare’s plays premiered. He starred in a number of its Shakespeare productions, including some with authentic all-male casts and period costumes and staging.

Rylance also won awards playing a variety of very different characters. In 1993 he won his first Olivier award (the top British acting honor) for playing Benedick in Much Ado about Nothing, and followed that up with a British Academy Television award for the TV film The Government Inspector (directed by Peter Kominsky, who later directed him in Wolf Hall, for which he was nominated for an Emmy). He did a comic star turn in a 2007 staging of Boeing-Boeing and was nominated for another Olivier; he won his first Tony when the production moved to Broadway. His second Olivier and second Tony came for his performance as Johnny Byron in Jerusalem, first in London and then on Broadway.

Perhaps Rylance’s greatest success, however, came with a pair of Shakespeare plays done in repertory, Twelfth Night, in which he played Olivia, and Richard III, with him in the title role. Rylance had played Olivia at the Globe in 2002, but from November, 2012 to February, 2013, both plays ran in alternation in the West End. Later they transferred to Broadway, where Rylance was nominated for a Tony as best actor as Richard III and won for best featured actor as Olivia. The plays were done as authentically as possible, with men playing all the roles and wearing costumes true to Shakespeare’s era.

Ben Brantley conveys some of the excitement of these productions and Rylance’s performances in his New York Times review:

In this imported production from Shakespeare’s Globe of London, deception is a source of radiant illumination for the audience, while the bewilderment of the characters onstage floods us with pure, tickling joy. I can’t remember being so ridiculously happy for the entirety of a Shakespeare performance since — let me think — August 2002.

That was the last time I saw the Globe’s “Twelfth Night” (in London), directed by Tim Carroll and starring the astonishing Mark Rylance, in a bar-raising performance as the Countess Olivia. And how thrilled I am that our wandering paths have crossed once more, rather like those of the separated twins at the play’s center.

This “Twelfth Night” — which opened on Sunday in repertory with a vibrant and shivery “Richard III” that allows Mr. Rylance to show he’s as brilliant in trousers as he is in a dress — makes you think, “This is how Shakespeare was meant to be done.”

Walter Kaiser makes similar remarks in The New York Review of Books (available to subscribers only; in print in the February 6, 2014 issue):

The production of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night by the English theatrical company Shakespeare’s Globe, currently at the Belasco Theatre, brings this play to life in a way I have only very rarely seen equaled in a Shakespearean production. The performances are so uniformly skillful, the interpretation of the play so intelligent and imaginative, and the costumes and stage set so accurate and evocative that the entire experience is exhilarating. Audiences at the performances I’ve attended have been overcome with delight, clearly somewhat surprised by the affecting immediacy of the theatrical experience they have undergone, unaccustomed to a Shakespeare so readily comprehensible and so vividly alive. You may, if you’re lucky, see another Shakespearean production that’s as good as this one, but it’s unlikely you will ever see one that’s better. […]

Mark Rylance, who over the past decade or so has made the part his own, is undoubtedly one of the greatest Olivias of all time. Frequently, this part is played with a grave, graceful maturity that tends to mask, or at least minimize, the intensity of the emotional quandary Olivia finds herself in when, not wishing to receive any further expressions of love from Orsino, she discovers that she has fallen in love with the messenger who delivers them. Rylance, instead, beautifully exposes her perfervid confusion: overcome with emotion, he stammers (in confirmation of Viola’s observation that “she did speak in starts”), acts with impetuosity, and manifests, at times, an engaging exasperation with his inability to control his passion. His hands alone, in the informative subtlety of their gestures, betray the emotions Olivia wishes to conceal.

I was lucky enough to encounter this Twelfth Night, as well as Richard III, in late 2012 when I was in London for a few days. I’m partial to authentic performance styles in theatre and music, so the chance to see two Shakespeare productions with all-male casts was appealing. Little did I realize that I would be seeing two brilliant turns by an actor I had never seen before–or so I thought. In fact, he plays Ferdinand in Prospero’s Books, but nobody, especially in such a small, bland role, can get much attention when playing alongside John Gielgud as Prospero.

Spielberg discovered Rylance in the same way that I did. In a very informative article based on interviews with Rylance and Spielberg, Jack Cole reveals:

Spielberg was urged to see Rylance in “Twelfth Night” by Daniel Day-Lewis. He calls him “a shape-shifter, a man of a thousand faces and voices who can play any part.”

“Seldom has an actor been around for so many distinguished years on the stage and yet had not been fully discovered for the screen,” said Spielberg by email. “Mark understands that the camera records stillness better than in any other media. His transition from the stage to ‘Bridge of Spies’ was graceful and invisible.”

Cromwell and Abel and beyond

Those members of the American public who did know Rylance before Bridge of Spies had probably encountered him as Thomas Cromwell in the BBC series Wolf Hall, a Tudor-era costume drama which aired in six parts on PBS starting April 6, 2015. (David and I streamed it more recently, mainly to see Rylance.) It seems unfortunate that the two breakout roles that have brought the actor to such prominence this year both involve notably restrained performances.

Anthony Lane compared these performances in his New Yorker review of Bridge of Spies:

So what’s it all about? It’s not about the U-2 missions, and certainly not about Powers, who comes across as a lunk. Nor, despite the set pieces in court, is it about the majesty of the law. No, the core of this movie is a standoff every bit as keyed up, and as gripping, as anything on the muffled streets of Berlin. What we thrill to is Rylance versus Hanks: the British actor, lauded for his stage appearances, but barely known to cinema audiences, up against the consummate Hollywood pro. You can see them prowling, probing, and wondering what the next move will be—or, in Hanks’s case, wondering whether Rylance will move at all. Admirers of “Wolf Hall,” on PBS, will have noted him as Thomas Cromwell, standing like a statue in the shadows, and realized, to their discomfort, that they could not look away. He does the same thing here, as Abel; we watch him watching everybody else, as if life were an infinity of spies. “You don’t seem alarmed,” Donovan says when they first meet, and Abel replies with a gentle question: “Would it help?” The Coens turn that into a refrain that beats through the movie, growing wryer and funnier each time—right up to the fidgety finale, where Abel is the calmest man in sight.

Of course, Cromwell does move in Wolf Hall. He moves a lot. Few television series can have shown their protagonists walking from place to place so often and at such length. Rylance modeled his gait on that of a Hollywood star, according to the Cole piece cited above: “He’s explaining how Mitchum, whom he adores, inspired his steady, rigid gait in the international hit series ‘Wolf Hall.'”

More Rylance on Mitchum, from another interview:

I’ve watched lots of films preparing for this, and I was particularly struck by one of my favourite actors, Robert Mitchum, how his performances haven’t dated in the way that even perhaps more versatile actors, Brando and Dean and people of that era, have. I noticed how well he listens, how still he is, how present he seems. You’re drawn towards the screen – wondering what’s he thinking, what’s he going to do next. That’s always the best way to tell a story.

Kominsky describes adjusting his filming style for Wolf Hall to catch Rylance’s subtleties:

The one thing you might not be expecting is that he’s the most minute of film performers. Nothing is overblown. Nothing is writ too large. It’s very, very simple, very understated, his performance, and then you look into his eyes, and it’s all happening. Everything is going on in there, and of course, you’re drawn into closer and closer shots, just to try and capture the emotion that’s going on very slight below the surface, and that’s what I loved to film. (From George Pollen documentary, Sky’s Arts program, 19:00-19:47)

As David has pointed out, however, the eyes as such are not always particularly expressive. It’s the area of the face that contains the eyes that does the job. The eyebrows and forehead usually give the context that tells us what the eyes are expressing.

If we concentrate on the upper half of Rylance’s face, the considerable differences between his Cromwell and his Abel become apparent.

As Abel, he consistently does something rather remarkable: he raises his eyebrows, creating furrows in his forehead, without widening his eyes. That’s not an easy thing to do. The result is a perpetually curious or surprised expression, a sort of mask that Abel wears to suggest that he is naive, innocent, a little slow. In fact, as we discover whenever he speaks with Donovan, he’s well aware of everything going on around him and has considerable insight into it. But it’s the naivete that allows him to dupe the agents who search his hotel room into letting him clean the paint off his palette, thus allowing him to conceal a key bit of evidence.

The key moment during which Rylance drops this tactic happens during his “standing man” anecdote, about a man he knew who survived a severe beating by Soviet agents by simply getting up again each time he was struck to the ground; Donovan reminds him of that man, he says.

As Cromwell, Rylance’s main tactic using his face is to glance away at nothing in the course of a scene where he is conversing with someone or observing interactions among other characters. So much classical editing depends on our understanding of whom or what a character is looking at, but not here. In one scene, Ann Boleyn shows him a drawing she has found hidden in her bed, depicting her decapitated. She asks him to find out who put it there.

Apart from his eyes, Rylance remains uttlerly motionless through the shot in which she holds the drawing out to him. Initially he is looking at her face (that’s the side of her head out of focus in the foreground) and then glances down at the drawing as she holds it up from below the frame.

He then glances down briefly to a point just outside frame right–clearly not at Boleyn’s face or anything else relevant to the action.

He looks at her face again and finally at the drawing.

Nothing here betrays Cromwell’s emotions, since he is a man who has to keep his thoughts hidden from most of the people at court. But that extra shifting of the eyes momentarily to an inconsequential space shows us that he’s thinking. Maybe he has an idea as to who would have left the letter. Maybe he’s thinking of Ann’s sister’s warning to him in an earlier scene, telling him not to help Ann. We don’t know here, as we don’t in many other scenes where Rylance uses this same sort of eye movement.

Both Abel and Cromwell need to conceal their thoughts, but Abel does so through deception and Cromwell through concealment, both conveyed by subtle acting.

In the Pollen documentary, Rylance describes how he avoids putting too much into a performance (in this case referring to lecturing on stage acting to students):

If I was only allowed three words, I could distill all my complicated notes, and you can see how wordy I get if I get talking, to three words, which would be “You are enough.” What’s happening to you is you don’t feel you’re enough, and you’re putting more effort into it than you should. You’ll be in the center of yourself, your voice will be centered, your movements will be centered, and the audience will also believe you more, because they’ll also believe that you’re enough. (8:35-9:08)

In Bridge of Spies, the little gestures and bits of business that Rylance uses to draw our attention to Abel are minimal. He wipes his nose occasionally, apparently the victim of a persistent cold or allergy.

As Michael Phillips points out in his review, this cold creates a parallel to Donovan, who has his overcoat stolen in East Berlin and soon develops a cold of his own:

It’s brilliant, really. What’s the quickest way to establish the humanity of two leading characters in a Cold War drama? Give them both the sniffles. […]

Because he’s relatively new to multiplex audiences, Mark Rylance will likely walk off with the acting honors for “Bridge of Spies.” He looks nothing like the real Abel, but in a largely nonverbal, supremely poker-faced performance — even his stuffy nose is subtle — Rylance suggests a forlorn practitioner of deception who recognizes a lucky break when he sees it.

(Agent Hoffman has also caught a cold by the epilogue; an occupational hazard, apparently, and a subtle comic motif.)

There are other gestures: lengthy tapping of a cigarette on an ashtray and little sucking movements of the lips, suggesting ill-fitting dentures. (A bit more subtle scene-stealing than that practiced by Steve McQueen in The Magnificent Seven, as described by David.)

Yet Rylance is perfectly capable of comic, broad performances as well. His Olivier-and-Tony-winning turn in Jerusalem was as a raucous, drunken rascal.

He made Richard III a grotesquely deceitful clown.

His Olivia, though more restrained, can do a broad comic take, as when she first notices Malvolio sporting the detested cross-gartered yellow stockings (see bottom).

We can assume that his acting as the BFG will be miles away from his performance in Bridge of Spies.

Will Hollywood be able to embrace him?

Roger Friedman claims that Hollywood wants Rylance. Possibly, but Rylance is ambivalent about filmmaking and generally prefers the stage. Indeed, I wish I had a reason to be in London right now, since he is back in the theater, receiving more rave reviews as the depressed King Philippe in a limited run of Farinelli and the King, the much-praised first play by Rylance’s wife, Claire van Kampen.

The Cole piece sums up Rylance’s on-and-off relationship to film acting, which involves Rylance being willing to embrace it rather than it embracing him:

For Rylance, embracing movie acting has been a circuitous journey. As a young actor, he watched as his theater contemporaries — Daniel Day-Lewis, Gary Oldman, Kenneth Branagh — became famous on the big screen. Agents urged Rylance into TV and film so that he would be “a complete actor.”

“I just, time and again, was attracted by the theater where I was offered better opportunities,” says Rylance. “I auditioned for films and didn’t get them. I think I had some stuff to learn about film acting. I don’t think I was personally really ready for it. But I did come to resent it. I did eventually think: Why, why? You wouldn’t tell the great Tamasaburo or Ganjiro-san it’s not enough to be a Kabuki actor, you need to be a film actor.”

He rattles off some film experiences he’s enjoyed: the Quay brothers’ “Institute Benjamenta,” a A.S. Bryatt adaptation “Angels and Insects” and a handful of British TV films, like “The Government Inspector.”

“But I’ve made some bad films, too, that have not been enjoyable,” Rylance said on a recent New York afternoon on a day off from starring in van Kampen’s “Farinelli and the King” in London. “At a certain point after one of them I did a few years back, I said, ‘That’s it. I’m not interested in this anymore.’

“I thought: I need to be happy with who I am, where I am. That can be the kind of miners’ dust of being an actor,” he says. “For an actor, being dissatisfied with who you are can be the reason for becoming an actor, but it can become an illness.”

But once Rylance let go of being a movie star, film directors started calling.

“As I did that, wonderful film things started being offered to me,” he says. “Maybe that was partly the problem — that I was giving it too much forced value. Because I grew up in America, so I grew up with some theater. But mostly I saw three films a weekend in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.”

Yes, Rylance was a Wisconsin boy, in a sense. He was born in Kent in 1960, and his parents, both English teachers, moved to Connecticut in 1962 and then to Milwaukee in 1969. There his father taught at the University School of Milwaukee, where Rylance first studied acting. “He starred in most of the school’s plays,” as the Wikipedia entry cited above puts it. Returning to England, he studied at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts from 1978 to 1980. His time in the States suggests why his accent is not quite the normal English one that we expect from the great British actors. It is nice to think that Rylance was avidly attending films in Milwaukee during the same period when David and I were doing the same here in Madison.

Clips of some of Rylance’s stage roles are included in the George Pollen documentary linked above; others can be found by searching on YouTube. Fortunately the wondrous Twelfth Night was recorded and is available on DVD (here in the US and here in the UK). The rest of the cast is excellent, particularly Steven Fry as Malvolio and Paul Chahidi as Maria. The many cameras used in the filming capture the most salient action at every point and alternate details and long shots to give a sense of where the action is occurring. As the image below shows, it was filmed in the Globe, with the audience right up against the stage and quite obvious (in a good way) in many of the camera setups. In the scene below, a spectator gives a wolf-whistle as Malvolio struts about his his yellow stockings, which strikes me as a very groundling sort of thing to do. Having seen the performance from the front-row center of the balcony, I am glad to have a closer perspective.

[December 2: Rylance has won the New York Film Critics Circle award for Best Supporting Actor.]

[January 3, 2016: Rylance has won the National Society of Film Critics award for Best Supporting Actor.]

[February 15, 2016: Rylance has won the British Academy Film Award for Best Supporting Actor.]

[February 28, 2016: Rylance has won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor. The story linked to here considered this an upset, as Sylvester Stallone had been widely predicted to win. But as I’ve shown here, a lot of us back in October knew better.]

[February 29, 2016: Rylance has been nominated for an Olivier Award for Farinelli and the King.]

[March 6, 2016: Pete Hammond of Deadline Hollywood has pointed out that Rylance won his Oscar without ever having participated in a single campaign event in the awards season. (He was given a day off from his current stage show in Brooklyn, Nice Fish, to go to Los Angeles to attend the Oscars ceremony.)]

[December 31, 2016: The Queen’s New Year’s Honours for 2017 include a knighthood for Rylance.]

Watch those hands; or, Burt, Jean-Luc, and Bill come to Cinephile Summer Camp

Nouvelle Vague (1990).

DB here:

At this year’s Summer Film College in Antwerp, Peter Bosma pointed out that the event seems to be a unique mixture.

Films are screened from morn to midnight: this time, 38 films across 6 days and two half-days. But it’s not exactly a film festival, as there are no new releases.

So is it like Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato? Not exactly. While the shows included some restored titles (notably the Belgian Cinematek’s pretty makeover of Pollyanna, 1920), the films were mostly original prints with an occasional DCP.

So is it like Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato? Not exactly. While the shows included some restored titles (notably the Belgian Cinematek’s pretty makeover of Pollyanna, 1920), the films were mostly original prints with an occasional DCP.

Moreover, the films cluster around two or three major themes. This year we had Late Godard (fourteen titles, counting episodes of Histoire(s) du cinema) and the career of Burt Lancaster (eleven). In addition, there were nightly showcases called “Masterworks in Context,” which included one surprise film, title undisclosed. But unike most movie marathons, the Summer Film College introduces screenings with lectures and discussions. This year there were fourteen sessions, each running about ninety minutes. These are serious, intensely informative talks—very far from the usual brief introductions one gets at festivals or in art house warm-ups.

So is it an educational enterprise? Definitely, but without assignments, tests, or grades. It’s designed to serve Flemish-speaking professors and students, but also civilians who are just interested in a weeklong package of film and film talk. The event helps forge a community of film appreciation.

Finally, there’s often a guest filmmaker on hand, usually related to the main threads. This time it was Bill Forsyth, who directed Burt in Local Hero. That film was screened, along with Bill’s wonderful Housekeeping.

So what would you call the College? I once called it Cinephile Summer Camp, and that still seems accurate in evoking the sense of fun and camaraderie that pervade the place. We don’t all get mosquito bites, but after a week you come to enjoy seeing familiar faces and talking with them about what they’re seeing. Just as when you go to summer camp, you get to stay up late. But at no summer camp I ever attended did we drink so much beer.

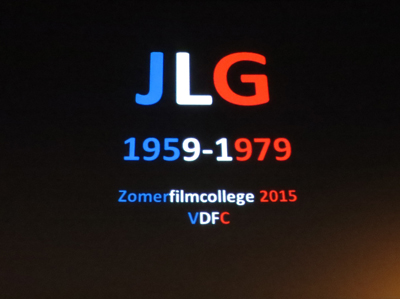

JLG/SJ/DB

The principal speakers were Tom Paulus and Anke Brouwers, who covered Burt, and Steven Jacobs on Late Godard. The Masterworks in Context shows were introduced by several guest speakers, including Lisa Colpaert (excellent on I Walked with a Zombie) and Vito Adriaensens (covering both Murder! and Vampyr). For Pollyanna, Bruno Mestdagh of the Cinematek staff explained the process of restoration. I played utility infielder, offering one talk on Burt and three on JLG.

How often do you get to see 35mm prints of Une femme mariée, Passion, Je vous salue Marie, Détective, JLG/JLG, Eloge de l’amour, and Nouvelle Vague? The Godard series, which ended with a 3D show of Adieu au langage, was a high point of my summer viewing. Back home I had prepared by rewatching all Godard’s features from Sauve qui peut (la vie) onward, but my video homework didn’t prepare me for the way the big screen amps up their prickly, seductive power.

I don’t speak or read Dutch, so I missed many subtleties in Steven Jacobs’ talks, but thanks to Power Point I could figure out the main points. Few lecturers can pack so much information and ideas into ninety minutes.

We had no way of knowing how familiar the audience was with Godard, early or middle or late, so Steven started with an orienting talk on JLG’s pre-1980 work (above). He swiftly reviewed key aspects of Godard’s New Wave period, traced his shift toward “a critical cinema” between 1967-1969, and explored the move into his Marxist phase. Along the way, he stressed the way cultural developments like auteur theory, Pop Art, Maoism, Brechtian theatre, and semiotics shaped Godard’s films. Particularly acute was his discussion of the “one image after another” sequence in Ici et ailleurs (1975). In all, the talk was an ideal prelude to Une femme mariée, which pointed up so many motifs of the later work: the focus on the couple, the emphasis on media-based images, and the persisting shadow of the Holocaust.

Steven is an art historian at University of Ghent; he earlier appeared on this blog as co-author of the imaginative book The Dark Galleries. After tracing Godard’s return to mainstream cinema and his move to Rolle, Switzerland, Steven focused on that splendid example of JLG the painter, Passion. Steven has written eloquently on the film in his Framing Pictures, and here he widened his focus to discuss its relation to other films centered on the tableau vivant, like Pasolini’s La Ricotta and Ruiz’s Hypothesis of the Stolen Painting.

You’d expect that Steven would have a field day with Histoire(s) du cinema, and he did. Unlike most Godardophiles, I’m not wild about this series of video essays. I can’t take them as serious studies in film history, and too often I sense he’s just playing around. (Enough with the stroboscopic flashes, okay?) But Steven obliged me to rethink them by showing how they fit into the Postmodern art scene, especially the video art movement after the 1970s. He pointed out the central importance of the Hitchcock episode and the series’ constant concern with the Holocaust, often in dialogue with Shoah. Citing Godard’s claim that video taught him to see cinema in a new way, Steven suggests that the format also created a tenor of paradoxical melancholy. It’s as if JLG’s experiments with this new technology drove him to celebrate the death of the cinema he knew.

My three talks on Late Godard tried to ask something that I didn’t find many traces of in the literature. What are these films doing with (or against) narrative? I think that the focus on JLG as “film essayist” has sometimes obscured the fact that he has long insisted that he needs stories. Yet he seems to have no interest in the craft of storytelling as we understand it. He avoids dense exposition, careful foreshadowing, well-timed revelations, and cumulative climaxes. He tends to spoil the narrative expectations he sets up.

As a result, his plots—for his films have them—are distressingly opaque. Exactly what happens in a Late JLG film is often difficult to determine. I’m always surprised when discussions of these late films provide capsule plot summaries, for the very difficulty of arriving at these should claim our attention. As just one instance, many critics seeing Adieu au langage for the first time thought the film centered on one couple. It centers on two. But the fact of that mistake ought to interest us enormously: What in the film’s presentation made it difficult to follow the basic situation? Are there strategies Godard follows in creating his apparently willful obscurity?

Godard’s unique strategies of storytelling are carried down into felicities of visual and verbal style. Again, I think that critics haven’t sufficiently acknowledged just how strange and opaque the surfaces of these movies are. For one thing, characters are unidentifiable from scene to scene, thanks to camera setups that cut off their faces, wrap them in shadow, or leave them offscreen altogether.

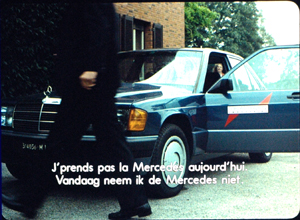

I’ve touched on these matters earlier (here and here), but just as a quick example, consider this shot from the opening of Nouvelle Vague. It has to be one of the most oblique introductions to a protagonist we can find in cinema.

Corporate owner Elena Torlato Favrini strides out of her mansion past her chauffeur while taking a transatlantic call. Any other director would favor us with a close view of her, perhaps tracking as she cuts a swath through her entourage. Instead we get a shot framing her chauffeur climbing out of their Mercedes.

As he crosses in front of the car, we hear her on her cellphone. She can be glimpsed fleetingly in the background, through the car window.

She approaches us, becoming briefly visible as she passes the car, but when she stops, she’s decapitated. We don’t get anything like a good look at her, and the locked-down camera refuses to reframe her. Instead, the framing emphasizes her slipping on her gloves.

The gesture ties into other imagery in the film. A little before this shot, there’s an isolated shot that establishes hands as a major motif in the film. But we should also notice that this fairly abstract shot also presents the gesture of Elena slipping on a glove. Or rather, it almost presents it, as the shot is abruptly chopped off just as the gesture begins.

So slipping on the glove, started in an earlier shot, is finished at the Mercedes. But just as important, the visual idea of a hand gesture broken by a cut resurfaces at the climax. When Richard Lennox helps Elena out of the water, the action is also incomplete. Only five frames show him grabbing her arm before a cut interrupts the action.

Another filmmaker would have held the image on that triumphant grip, but Godard denies us this little burst of satisfaction. Of the five frames in this bit of the shot, there is just one frame showing Richard’s hand seizing her. Godard again spoils a solid narrative effect. But he does narrative in his own way, with the broken-off gestures counterpointed by the hands that do meet at other points in the film.

Every scene in Nouvelle Vague, and most scenes in Late JLG, seem to me to be built on one or more fine-grained pictorial and auditory ideas like these. Those ideas can seem perverse, as in the chauffeur scene: why let us see his face but play down Elena’s? He’s not a major character; we don’t even learn his name until the film’s final moments. Unhappily, this peculiar instant of comparison is lessened in the 1.66 version of the film available on DVD. That image suppresses the driver’s face no less than Elena’s, losing Godard’s peculiar version of “gradation of emphasis.”

All the more reason to try to see these films in their full-frame glory, as I’ve argued before.

BL (Beautiful Loser)/AB/TP

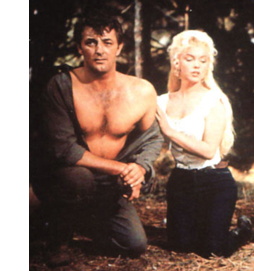

Criss Cross (1949).

With big tousled hair, unadulterated sinew, and teeth gleaming like a Pontiac grille, Burt Lancaster came to fame in the late 1940s. He belonged to a new cohort of actors quite different from the 1930s Debonairs (William Powell, Melvyn Douglas, Cary Grant) and the Bashful Boys (Cooper, Fonda, Stewart). Yet the new lads were also at variance with the rugged Ordinary Joes (Cagney, Bogart, Tracy, Gable).

For one thing, Lancaster, Victor Mature, Robert Ryan, Robert Mitchum, Kirk Douglas, and Charlton Heston were brawny—monsters, in a way. They often took off their shirts. One publicity still for River of No Return shows Mitchum more unclothed than Monroe. Three of them played prizefighters, and Mitchum, himself a boxer, had the broken nose of a brawler.

For one thing, Lancaster, Victor Mature, Robert Ryan, Robert Mitchum, Kirk Douglas, and Charlton Heston were brawny—monsters, in a way. They often took off their shirts. One publicity still for River of No Return shows Mitchum more unclothed than Monroe. Three of them played prizefighters, and Mitchum, himself a boxer, had the broken nose of a brawler.

Of the group, Burt had probably the strongest A-list career overall. He fostered a great variety of projects. Who else of his generation appeared in films by Visconti and Malle? What other unflinching liberal was prepared to play a US general bent on a coup (Seven Days in May) or a conspirator behind the Kennedy assassination (Executive Action) or an obstinate officer fighting in Vietnam (Go Tell the Spartans)? He portrayed a renegade officer demanding the revelation of the brutal policy behind the Vietnam War (Twilight’s Last Gleaming). His closest rival and frequent costar Kirk Douglas didn’t enjoy such a vigorous and prestigious twilight. Only Brando kept beating him to the prize: Burt wanted to play the lead in Streetcar Named Desire and The Godfather. Unpredictably, he wanted as well to play the gay prisoner in Kiss of the Spider Woman.

I had had only slight interest in Burt as a star before this edition of the Summer School. But listening to the talks, seeing the films, and preparing my contribution made me realize how extraordinary an actor he was, and how important in Hollywood postwar history. Burt was well-served by the fine lectures offered by Tom Paulus and Anke Brouwers.

Anke provided an in-depth survey of how Burt and the Brawny Gang brought to a new level the culture of male athleticism—on display in Fairbanks and Valentino, developed further in the body-building craze of the 1930s, and culminating in what one 1954 magazine article called Hollywood’s “Age of the Chest.” She brought in forgotten pin-up boys like Guy Madison and pointed out how Burt and his peers paved the way for Rock Hudson and Tony Curtis. Anke went on to specify Burt’s beefcake persona, established in The Flame and the Arrow (1950) and locked into place in The Crimson Pirate (1952), which we saw. In her followup talk next day, she surveyed Burt’s place in the industry. He was one of the few stars to supervise a successful independent production company, Hecht Hill Lancaster (earlier, Norma Productions and Hecht Lancaster).

Tom moved on to consider Burt’s star charisma. He traced how Burt adjusted his authoritative image to different roles—the con man, the confident leader, the embittered idealist. Tom was especially good at analyzing Burt’s acting technique, tying it to particular trends in theatre and film of the time and pointing up the physicality of his performance of specific, precise tasks. Given the standard situation of rigging a bomb, he contrasted Burt’s meticulous finger work in The Train (1964) with that of Kirk going through the motions in The Heroes of Telemark. Tom even spared some time for Burt’s diction—a quality that really popped out when we watched Elmer Gantry (1960).

In a later lecture, Tom surveyed “Late Burt,” and his relation to political cinema of the 1960s and 1970s. He followed that with a revealing account of Burt’s relation to the trend of “Mexican Westerns” launched in the 1950s. Another arc in Burt’s career: from Vera Cruz (1954) to Ulzana’s Raid (1972), with The Professionals (1966) in between. That we saw in another gorgeous print.

I could go on a lot more about Tom and Anke’s lectures, but I don’t want to give away too much. The talks contained so much original research and discerning analysis of both the films and trends within film history that I’m hoping Tom and Anke will lay these ideas out at book length. Part “star study,” part film criticism, part industry history, their lectures were exhilarating.

My own contribution was minimal, a talk on First-Phase Burt. The Brawny guys were well-suited to the trend toward hard-boiled movies, those crime pictures we later decided to call “noirs.” Those weren’t usually suitable for older players (though there were some makeovers, such as Dick Powell and Fred MacMurray). To fill these roles came Alan Ladd, Glenn Ford, Dana Andrews, and Richard Widmark, along with the beefcakes. At the same time, “independent” producers within the studios began contracting their own new talent and loaning it out. Burt was signed by Hal Wallis at Paramount, who also had Kirk Douglas, Wendell Corey, and Lizabeth Scott in his stable. Films like Desert Fury (1947) and Sorry, Wrong Number (1948) were Wallis package projects.

Hired straight from the stage with no film experience, Burt debuted as the Swede in The Killers (1946), on loanout to Mark Hellinger at Universal International. Burt benefited from a galvanizing entrance. Lying on a bed in the dark, refusing to flee the hitmen on his trail, Burt is a shadowed, curiously languid torso in a tight undershirt.

Only after a beat do we see something else: massive hands rubbing a weary head. Soon that head is revealed.

As the killers burst in, the whole image comes together.

Has a Hollywood beginner ever been given such a gift as this opening?

With this onscreen wattage, it’s all the more striking that this young discovery is curiously absent from his early films. He’s onscreen for only a third of The Killers’ running time, and not even half of Brute Force (1947) and Sorry, Wrong Number. The film Wallis wanted to be his debut, Desert Fury (1947), gives him only twenty-three minutes out of ninety, and in the second male lead at that. All My Sons (1948) puts him in an ensemble drama. I Walk Alone (1948), the Norma production Kiss the Blood Off My Hands (1948), and another Universal project, Criss Cross (1949) start to make him a proper, central protagonist. By then, he is ready to become the star attraction of the swashbuckling films.

Moreover, in his early phase, he mostly plays losers. Not the brightest guy in the room, he’s easily suckered by a femme fatale in The Killers and Criss Cross. He makes amateurish mistakes at crime (Sorry, Wrong Number) and, coming out of prison, he is the last to realize the rackets have gone corporate (I Walk Alone). At the start of Kiss the Blood he punches a man too hard and kills him. He’s caught and whipped and imprisoned, and when he comes out he stumbles back into crime again. He’s shrewd enough to set up a prison break in Brute Force, but so doggedly determined is he to reunite with his girl on the outside that he launches a suicidal bloodbath.

When he finally catches on to his fate, we get expressions ranging from stupefaction to anguish (The Killers, Criss Cross).

He even cries (All My Sons, Kiss the Blood).

Loser or winner, when he is onscreen, he has the outlandish physical presence of the born star. Most obvious is a physique (Kiss the Blood, Brute Force).

Even his back, featured with a prominence we get with few other actors, is straining against a drenched prison uniform (Brute Force) or a tailored suit (Criss Cross).

The face was a cameraman’s dream; it could be craggy or somber, thoughtful or tormented (The Killers, Brute Force x2, Criss Cross).

He can be stiff-armed and zombielike coming out of prison in Kiss the Blood, but he can also gamely cock his elbows, ready to spring, like Cagney and Cary Grant (I Walk Alone).

The enormous hands, which look likely to crush a skull (Criss Cross) or rip apart a phone cord (Sorry, Wrong Number), could be surprisingly delicate, tentatively touching his girlfriend’s wheelchair or laying down plans like playing cards (Brute Force).

In The Killers he makes skillful use of those hands, pocketing his busted one or spreading out the scarf given him by the treacherous Kitty.

Easily taken in by Kitty’s plan, he seems to have a qualm when his gripping embrace relaxes and the fingers splay in hesitation.

This sort of handwork would become crucial, as Tom pointed out, to Burt’s performance style, particularly in The Birdman of Alcatraz.

“I’d never looked in eyes as chilling as Lancaster’s,” Norman Mailer once said. You can see what he meant.

Again, though, the actor is in control. Some years back I wrote that eyes by themselves aren’t very expressive: the eyelids, eyebrows, and mouth tell us more. I still think that’s right, but Burt manages to convey the sense of the beast at bay with remarkable control of just the eyeballs. He seems to be looking for an escape hatch without moving his head an inch.

While Burt was playing losers, his counterpart Kirk Douglas was often playing heels—cynical manipulators who stomp on everybody else, as in I Walk Alone. Sometimes Kirk learns his errors (Young Man with a Horn, 1950) but several roles of the period, in Out of the Past, Champion, and Ace in the Hole, make him a glib villain or tawdry antihero. Somewhat later Burt explored this characterization too, notably in Vera Cruz, Elmer Gantry, and The Rainmaker (1956). How did he shift from the beautiful loser to the fast-talking con artist?

I think there are hints from the start. In The Killers, after he’s washed up as a fighter, the Swede goes in for street crime. When he confronts his old friend the cop, Lancaster brings those arms and hands into play. In his enormous unstructured topcoat, he lifts his fists up to his waist. It’s both the businessman’s getting-down-to-brass-tacks sweep, but also a kind of puffing up, exposing that massive frontal expanse. Little Sam Levene can grasp his lapels, but he doesn’t stand a chance against this.

Burt uses the same imperious gesture when, in Sorry, Wrong Number, he’s trying to bully a company employee into joining a crooked deal.

In these noir movies, his intimidation of others won’t put him ahead of the game. But perhaps these arm movements begin to sketch a more flamboyant loser like Gantry. By striking what actors used to call an “attitude,” Burt could start to build an entire character: a hell-for-leather charlatan.

Seeing the films, listening to Tom and Anke, and studying Lancaster’s work on my own brought home to me again the importance of the details of performance and the presence of a star. These movies would be utterly different if Mitchum or William Holden played the Burt parts. Our actors don’t wear masks or Hazmat suits. We’re powerfully affected by what they bring to the character in voice, body, face, and gesture—the expressive dimensions of cinematic presence.

BL/JLG/BF

College coordinators Lisa Colpaert and Bart Versteirt, flanking Bill Forsyth.

What do Burt and JLG have in common? For one thing, some images from Criss Cross in Histoire(s) du cinema 1a (see above). For another, Bill Forsyth.

With the success of Gregory’s Girl (1981), Bill was invited by David Puttnam, then at Columbia, to make a Scottish movie with a couple of American actors. The result, Bill says, now looks to be a “soft-core environmental movie.” Local Hero (1983) remains much loved, and for good reason. It makes nearly all of today’s multiplex raunch look adolescent. It has a tone of civility, an embrace of eccentricity, and a genuine interest in people reminiscent of Ealing comedies. For me it’s a masterpiece of sweet, light-hearted art.

Local Hero feels loose and leisurely, but it’s actually a very economical movie. The first few minutes should be studied by screenwriters interested in tight exposition and fast attachment to a protagonist. It’s peppered with sidelights on its central drama, such as the Russian’s song about how “even the Lone Star State gets lonesome.” That neatly sums up the situation of the yuppie sad sack MacIntyre (“I’m more of a Telex man”) learning about village life. As usual, I was moved by Mark Knopfler’s plangent score, the electronic overtones meshing with the pulsations of the Northern Lights.

Burt’s role is that of CEO deus ex machina. Having assigned Mac to buy a Scottish seacoast town for an oil refinery, Mr. Happer eventually descends in his chopper and decides to establish a laboratory there instead. Burt’s crisp delivery and tight fingerwork are still on display at age seventy. The other actors don’t use their hands as much as he does–partly so they’re not distracting us from him, I suspect, but also because newer-style Hollywood acting doesn’t encourage it. In any case, as usual Burt uses his acrobat’s sense of physicality to intensify his performance. Even clasping his hands behind his back tells about the character’s authoritative dignity.

Bill learned that Burt regretted not doing more comedy, so he wrote the mogul’s part with him in mind. Burt signed on eagerly. He showed up on the set with a full beard, hoping Bill would let him keep it; they compromised on a mustache.

Bill had worked mainly with teenage actors on That Sinking Feeling (1979) and Gregory’s Girl, so Burt was really the first adult performer he ever directed. Across their three weeks together, Burt demanded nothing, except that he wanted to loop his dialogue. Bill preferred not to loop, and as it turned out only one scene needed to be rerecorded.

Burt and Bill skipped lunch in order to prepare the next scene, becoming “lunch bums.” Bill remembers Burt hanging out with the other actors and chatting with extras. He freely made fun of Bill’s accent: “”He speaks no known language.” He told Bill: “I don’t know what you’re saying, but I know what you mean.”

Bill talked as well about his own career. Starting out in the days before home video, he learned dialogue and pacing by audio taping classic films. (Sounds like a good idea to me.) He became a performer’s director. “The only thing I’ve ever said to a cameraman is: ‘Accommodate the actors.” He quoted Burt approvingly: “The space in front of the camera is the actor’s space.”

What’s the connection to JLG? It turns out that Godard was the director Bill most admired in his salad days. During the 60s he sated himself on art cinema, especially New Wave imports. When he saw Pierrot le fou, he left the theatre stunned. Godard became “the master. He still is, for me.”

Accordingly, Bill’s earliest cinema efforts were in an avant-garde vein. One piece, puckishly called Film Language, started with ten minutes of black leader while a text by Beckett was read out. Another, Waterloo, included a vast ten-minute shot in which the camera left one household, climbed into a car, rode a great distance, and ended up in another home. The film played at the Edinburgh film festival to an audience of 200. By the end three viewers were left. “I’d moved my first audience.”

Bill remarked that he sometimes regrets not sticking with experimental media. Today, he says, he might be a video-installation artist. A teasing idea. But we should be grateful that we got his features. I don’t know if Jean-Luc would agree, but I bet Burt would.

Thanks to Bart Versteirt, Lisa Colpaert, and their colleagues for a great week. Thanks as well to the participants, whose willingness to take on anything we threw at them was very encouraging. And a farewell to two friends who have projected films at every Summer Film College I’ve attended over the last sixteen years: Esther Dijkstra and Joost De Keijser. They have helped make the event the splendid enterprise it is.

Peter Bosma’s informative book Film Programming: Curating for Cinemas, Festivals, Archives is available here.

A detailed “index of references” for Histoire(s) du cinema is provided by Céline Scemama.

Our first encounter with Bill Forsyth was at Ebertfest. For more on actors’ handiwork, try this entry.

An eager crowd of campers awaits Adieu au langage.