Archive for the 'Film technique: Performance' Category

Creating a classic, with a little help from your pirate friends

DB here:

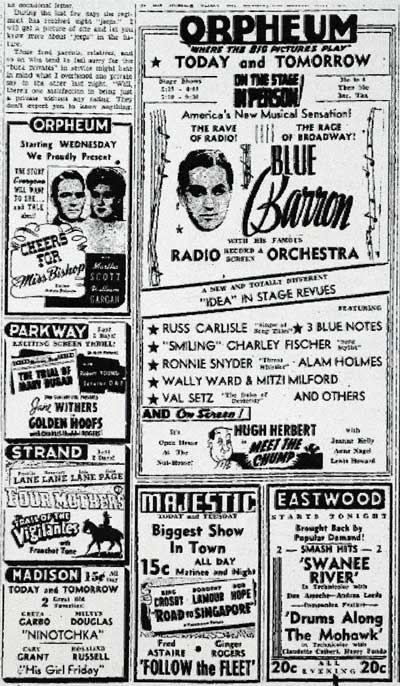

In early April of 1940, His Girl Friday came to Madison, Wisconsin. It ran opposite Juarez, The Light that Failed, Of Mice and Men, and a re-release of Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Pinocchio was about to open. Most screenings cost fifteen cents, or $2.21 in today’s currency.

Before television and home video, film was a disposable art. Except in big cities, a movie typically played a town for a few days. Programs changed two or three times a week, and double bills assured the public a spate of movies—nearly 700 in 1940 alone. People responded, going to the theatres on average 32 times per year. Given the competition, it’s no surprise that His Girl Friday didn’t stand out in the field; it was nominated for no Academy Awards and honored by no prizes. On just a single day in Madison, the cast of His Girl Friday was up against icons like Muni, Colman, March, and Bette Davis.

Nowadays, of course, nearly everyone regards HGF as one of the great accomplishments of the studio system. Most would consider it a better movie than any of the others it played opposite in my home town. A typical example of critical exuberance is Jim Emerson’s comment here. Or read James Harvey’s 1987 encomium:

It would be hard to overstate, I think, the boldness and brilliance of what Hawks has done here: not only an astonishingly funny comedy, but a fulfillment of a whole tradition of comedy—the ur-text of the tough comedy appropriated fully and seamlessly to the spirit and style of screwball romance. His Girl Friday is not only a triumph, but a revelation.

Oddly, this extraordinary film lay largely unnoticed for three decades. How did it become a classic? The answer has partly to do with the rising status of Howard Hawks, the director, among critics. It also owes something to changes in how academics thought about film history. And a little movie piracy didn’t hurt.

An unseen power watches over the Morning Post

Hawks the Artist is a creation of the 1960s. Before that, American film historians almost completely ignored him. Andrew Sarris often reminds us that he’s absent from Lewis Jacobs’ Rise of the American Film (1939), but he’s also missing from Arthur Knight’s The Liveliest Art (1957), the most popular survey history of its day. Apart from press releases and reviews of individual films, there were few discussions of Hawks in American newspapers and magazines. The most famous piece is probably Manny Farber’s “Underground Movies” of 1957, which treats Hawks along with other hard-boiled directors like Wellman and Mann.

From the start, Hawks was more appreciated in France. There film historians acknowledged A Girl in Every Port (1928), in part because of the presence of Louise Brooks, and they usually flagged Scarface (1932) as well, which they could see and Americans couldn’t. (Howard Hughes kept it out of circulation for decades.) But Hawks is barely mentioned in Georges Sadoul’s one-volume Histoire du cinéma mondiale (orig. 1949) and he’s ignored in the 1939-1945 volume of René Jeanne and Charles Ford’s monumentally monotonous Histoire encyclopédique du cinéma (1958).

The essay that marked the first phase of reevaulation was evidently Jacques Rivette’s “The Genius of Howard Hawks” in Cahiers du cinéma in 1953. Inspired by Monkey Business, Rivette’s philosophical flights and you-see-it-or-you-don’t tone helped define the auteur tactics identified with Cahiers’s young Turks. Rivette and his colleagues became known as “Hitchcocko-Hawksians.” The essay, however, doesn’t seem to have been immediately influential. Antoine de Baecque claims that within Cahiers, an admiration for Hawks was controversial in a way that liking Hitchcock was not. (1) It took some years for Hawks to ascend to the Pantheon.

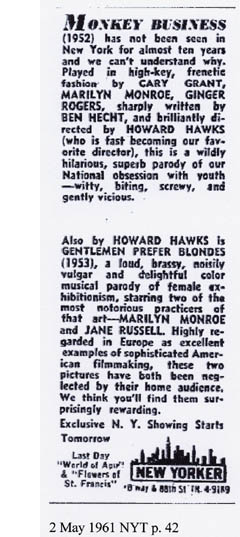

The story of that ascent has been well-told by Peter Wollen in his essay, “Who the Hell Is Howard Hawks?” In France, the Young Turks’ tastes had been nurtured by Henri Langlois, who showed many Hawks films at the Cinémathèque Française. In New York, Andrew Sarris and Eugene Archer had become intrigued by Cahiers but were ashamed that as Americans they didn’t know Hawks’ work. They persuaded Daniel Talbot to show a dozen Hawks films at his New Yorker Theatre during the first eight months of 1961. The screenings’ success allowed Peter Bogdanovich to convince people at the Museum of Modern Art to arrange a 27-film retrospective for the spring of 1962. The package went on to London and Paris, sowing publications in its wake.

The story of that ascent has been well-told by Peter Wollen in his essay, “Who the Hell Is Howard Hawks?” In France, the Young Turks’ tastes had been nurtured by Henri Langlois, who showed many Hawks films at the Cinémathèque Française. In New York, Andrew Sarris and Eugene Archer had become intrigued by Cahiers but were ashamed that as Americans they didn’t know Hawks’ work. They persuaded Daniel Talbot to show a dozen Hawks films at his New Yorker Theatre during the first eight months of 1961. The screenings’ success allowed Peter Bogdanovich to convince people at the Museum of Modern Art to arrange a 27-film retrospective for the spring of 1962. The package went on to London and Paris, sowing publications in its wake.

For the MoMA retrospective, Hawks granted Bogdanovich a monograph-length interview, which was to be endlessly reprinted and quoted in the years to come. (2) Sarris, now knowing who the hell Hawks was, wrote a career overview for the little magazine, The New York Film Bulletin, and this piece became a two-part essay in the British journal Films and Filming. Both Bogdanovich and Sarris made brief reference to His Girl Friday, as did Peter John Dyer in another 1962 essay, this one for Sight and Sound. At the end of 1962, another British magazine, Movie, published an issue on Hawks. At the start of 1963, Cahiers devoted an issue to him, including an homage by Langlois himself. Thanks to the work of Archer, Bogdanovich, Sarris, and MoMA, Hawks was rediscovered.

Sarris provided a condensed case for Hawks in his far-reaching catalogue of American directors, published as an entire issue of Film Culture in spring of 1963. There followed an interview with Hawks’s female performers in the California journal Cinema (late 1963), an appreciation by Lee Russell (aka Peter Wollen) in New Left Review (1964), another Cahiers issue (November 1964), J. C. Missiaen’s slim French volume Howard Hawks (1966), Robin Wood’s Howard Hawks (1968), and Manny Farber’s Artforum essay (1969). There were doubtless other publications and events that I never learned about or have forgotten. In any case, by the time I started grad school in 1970, if you were a film lover, you were clued in to Hawks, and you argued with the benighted souls who preferred Huston. . . even if you hadn’t seen His Girl Friday.

Light up with Hildy Johnson

One of my obsessions in graduate school was the close analysis of films. But I was also interested in whether one could build generalizations out of those analyses. My initial thinking ran along art-historical lines. My Ph. D. thesis on French Impressionist cinema sought to put the idea of a cinematic group style on a firmer footing, through close description and the tagging of characteristic techniques. But that approach came to seem superficial. I wasn’t satisfied with my dissertation; although it probably captured the filmmakers’ shared conceptions and stylistic choices, I couldn’t offer a very dynamic or principled account of formal continuity or change.

Watch a bunch of movies. Can you disengage not only recurring themes and techniques, but principles of construction that filmmakers seem to be following, if only by intuition? As I was finishing my dissertation, reading Russian Formalist literary theory pushed me toward the idea that artists accept, revise, or reject traditional systems of expression. These become tacit norms for what works on audiences. My reading of E. H. Gombrich pushed me further along this path. We should, I thought, be able to make explicit some of those norms. Eventually I would call this perspective a poetics of cinema.

I was assembling my own version of some ideas that were circulating at the time. In the early 1970s, several theorists floated the idea that different traditions fostered different approaches to filmic storytelling. People were seeing more experimental and “underground” work, as well as films from Asia and what was then called the Third World. Being exposed to such alternative traditions helped wake us up to the norms we took for granted. The mainstream movie, typified by what Godard called “Hollywood-Mosfilm,” seemed more and more an arbitrary construction.

People began examining films not as masterworks or as expressions of an auteur, but as instances of a representational regime. Films became “tutor-texts,” specimens of formal strategies that were at play across genres, studios, periods, and directors. Again, the French pointed the way, particularly Raymond Bellour, Thierry Kuntzel, and Marie-Claire Ropars. At the same moment, Barthes’ S/z was published in English, and it seemed to provide a model for how one might unpick the various strands of a text, either literary or cinematic. Screen magazine was a conduit for many of these ideas in the English-speaking world.

Some of my contemporaries disdained the mainstream cinema and moved toward experimental or engaged cinema. Others read the dominant cinema symptomatically, for the ways it revealed the contradictions of ideology. I learned from both approaches, but I believed that the current analysis of how Hollywood worked, even considered as a malevolent machine, was incomplete. Could we come up with a more comprehensive and nuanced account of the mainstream movie? This line of thinking was already apparent in non-evaluative studies of form and style, such as essays by Thomas Elsaesser, Marshall Deutelbaum, and Alan Williams. (3)

At some point in graduate school at the University of Iowa, between fall 1970 and spring 1973, I saw a screening of His Girl Friday. I fell in love with its heedless energy. It seemed to me a perfect example of what Hollywood could do.

In my admiration I was channeling the cultists. Rivette, in a review of Land of the Pharoahs: “Hawks incarnates the classical American cinema.” (4) Bogdanovich: He is “probably the most typical American director of all.” Richard Griffith, then film curator of MoMA, had slighted Hawks in his addendum to Paul Rotha’s The Film Till Now, but in his foreword to the Bogdanovich interview he caved to the younger generation: “Hawks works cleanly and simply in the classical American cinematic tradition, without appliquéd aesthetic curlicues.” As for HGF, in the 1963 Cahiers tribute Louis Marcorelles called it “the American film par excellence.”

Praising Hawks, and HGF specifically, was part of a larger Cahiers strategy to validate the sound cinema as fulfilling the mission of film as an art. What traditional critics would have considered theatrical and uncinematic in HGF—confinement to a few rooms, constant talk, an unassertive camera style—exactly fit the style that Bazin and his younger colleagues championed. (For more on that argument, see Chapter 3 of my On the History of Film Style.)

These niceties didn’t inform my reaction at the time. I was already primed to like Hawks, though, having caught what films I could after reading Wood et al. (During my initial summer in Iowa City, I went to a kiddie matinee of El Dorado and got Nehi Orange spilled down my neck.) On my first viewing His Girl Friday delighted me with the sheer gusto of the pace and playing. Clearly the cast was having fun. A press release sent out before the film claimed that during one scene, with Cary Grant dictating frantically to Rosalind Russell, she cracked him up by handing over what she had typed.

Cary Grant is a ham. Cary Grant is a ham. Now is the time for all good men to quit mugging. You don’t think you can steal this scene, do you—you overgrown Mickey Rooney? The quick brown fox jumps over the studio. Cary Grant is a ham.

Even discounting this tale as PR flackery, we know from Todd McCarthy’s excellent biography that Hawks encouraged competitive scene stealing and wily improvisation. Russell hired an advertising copywriter to compose quips she could “spontaneously” conjure up in her duels with Grant.

If there was a “classical Hollywood cinema”—a phrase that was in the early ’70s coming into circulation via Screen—the buoyant forcefulness of His Girl Friday embodied it. Here was a film pleasure-machine that hummed with almost frightening precision. What else do you expect from a director who studied engineering and whose middle name is Winchester?

Production for use

When I saw His Girl Friday, little had been written about it. Despite Langlois’ screenings, before the 1962 touring program, the Cahiers critics seemed to have had limited access to Hawks’ prewar work. His Girl Friday wasn’t released theatrically in France until January of 1945 (not perhaps the most propitious moment), and it apparently made no long-lasting impression on the intelligentsia. I can’t find any critical commentary on it in French writing before the 1963 issue of Cahiers.

In the United States, HGF earned Hawks a courteous write-up in the New York Times by, of all people, Bosley Crowther, (5) but it wasn’t acknowledged as an instant classic like Mr. Smith Goes to Washington or The Philadelphia Story. After the initial flurry of mostly favorable reviews, the movie seems to have been forgotten until Manny Farber’s 1957 essay, and even there it’s only mentioned in a list. Interestingly, it wasn’t screened during the 1961 New Yorker series. Robin Wood’s sympathetic but not uncritical discussion in his Hawks book of 1968 seems to have been the most comprehensive account available since the movie’s release.

At about the time Wood’s book was published, something big happened. Columbia Pictures failed to renew its copyright, and His Girl Friday fell into the public domain.

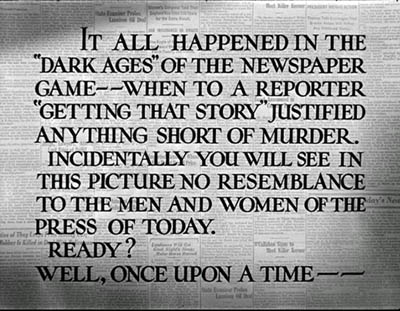

Entrepreneurs made dupe copies, in quality ranging from okay to terrible. You could rent one for peanuts and buy one for only a little more. Some of these bleary prints have been telecined and turned into the DVD versions of the film that fill bargain bins today. After I got to the University of Wisconsin, where Hawks films stoked the two dozen campus film societies, I bought a public domain print. The copy was better than average, although it lacked the fairy-tale warning title at the start. From 1974 on, I showed the poor thing constantly.

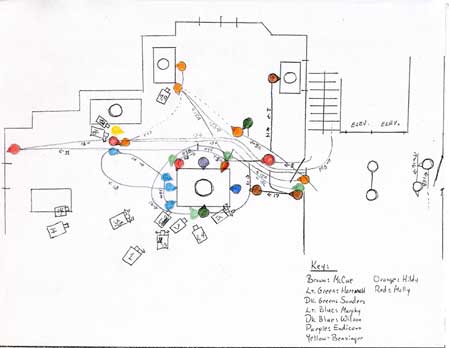

In Introduction to Film, taught to hundreds of students each semester, HGF illustrated some basic principles of classical studio construction. It had the characteristic double plotline (work/ romance), a careful layout of space, an alternation of long takes and quick cutting, manipulation of point-of-view, judicious depth framing (see frame below), and cascading deadlines. In Critical Film Analysis, I asked students to map out scenes shot by shot (see diagram above) and to show how different approaches (genre-based, feminist, Marxist) would interpret the film. In a seminar on “the classical film and modernist alternatives” HGF grounded comparisons with Bresson, Dreyer, Ozu, Godard, and Straub/Huillet. By steeping ourselves in such alternative traditions, could we resist the naturalness of Hollywood artifice?

The movie became a UW staple. It went into the first edition of Film Art (1979) as an instance of classical construction; even the telephones were scrutinized. Marilyn Campbell’s paper from our seminar was published in 1976. (6) Over the years, many of our grad students, exposed to the film in our courses, have gone on to use it in their teaching.

Doesn’t have to rhyme

I can’t let HGF go. I still use moments to illustrate points in my writing and lectures. Madison colleagues and I swap banter from it; Kristin and I talk in Hawks-code, as she explains here. I’ve been told that grad students in another PhD program compared our program to the Morning Post pressroom (favorably or not, I don’t know). Thanks to Lea Jacobs, the invitation to my retirement party was surmounted by a picture of Walter Burns whinnying into his phone.

But seriously, His Girl Friday, isn’t a bad guide to a lot of social life. You can learn a lot from its Jonsonian glee in selfishness and petty incompetence, as well as its sense that virtue resides with the person who has the fastest comeback. Think as well how often you can use this line in a university setting:

If he wasn’t crazy before, he would be after ten of those babies got through psychoanalyzing him.

I’m not claiming special credit for the HGF revival, of course. Plenty of other baby-boomer film professors were teaching it. It became a reference point for feminist film criticism, particularly Molly Haskell’s From Reverence to Rape (1974), and it has never lost its auteurist cachet. Richard Corliss’s 1973 book on American screenwriters flatly declared that “His Girl Friday is Hawks’s best comedy, and quite possibly his best film.”

Most important of all, TV stations were screening their bootleg prints. HGF didn’t become a perennial like that other public domain classic It’s a Wonderful Life, but its reputation rose. Its availability pushed the official Cahiers/ Movie masterpieces Monkey Business and Man’s Favorite Sport? into a lower rank, where in my view they belong.

Once HGF became famous, the proliferation of shoddy prints became an embarrassment. In 1993 it was inducted into the National Film Registry, which gave it priority for Library of Congress preservation. Columbia managed to copyright a new version of the film. A handsomely restored version was released on DVD, and a few years back I saw a 35mm copy whose sparkling beauty takes your breath away.

The lesson that sticks with me is this. If Columbia had renewed its copyright on schedule, would this film be so widely admired today? Scholars and the public discovered a masterpiece because they had virtually untrammeled access to it, and perhaps its gray-market status supplied an extra thrill. Thanks mainly to piracy, His Girl Friday was propelled into the canon.

Epilogue

In May of 1940, His Girl Friday hung around Madison, shifting from its first venue, the Strand downtown, to an east side screen, the Madison. The film came back in late September to yet a third screen, the Eastwood (now a music venue).

HGF was revived in March of 1941, as the second half of a double bill at the Madison (bottom left below). Check out the competition: some killer re-releases from Ford, Lubitsch, Astaire-Rogers, and Hope-Crosby. A Midwestern city of 60,000 could become its own cinémathèque without knowing it.

(1) Antoine de Baecque, Cahiers du cinéma: Histoire d’une revue, vol. 1: À l’assaut du cinéma, 1951-1959 (Paris: Cahiers du cinéma, 1991), 202-204.

(2) Bogdanovich has published a much fuller version in Who the Devil Made It? (New York: Knopf, 1997) , 244-378.

(3) Thomas Elsaesser, “Why Hollywood?” Monogram no. 1 (April 1971), 2-10; “Tales of Sound and Fury,” Monogram no. 4 (1972), 2-15; Marshall Deutelbaum, “The Structure of the Studio Picture,” Monogram no. 4 (1972), 33-37; Alan Williams, “Narrative Patterns in Only Angels Have Wings,” Quarterly Review of Film Studies 1, 4 (November 1976), 357-372.

(4) Jacques Rivette, “Après Agesilas,” Cahiers du cinéma no. 53 (December 1955), 41.

(5) Bosley Crowther, “Treatise on Hawks,” New York Times (17 December 1939), 126. “He brings to his work as a director the ingenious and calculating brain of a mechanical expert. . . . He pitches into the job just as though he were building a racing airplane.”

(6) Marilyn Campbell, “His Girl Friday: Production for Use,” Wide Angle 1, 2 (Summer 1976), 22-27.

For a helpful collection of conversations with the master, see Howard Hawks Interviews, ed. Scott Breivold (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2006). Go here for a 1970s piece by James Monaco on then-current controversies.

PS 24 Feb: Jason Mittell responds to my post with some nice nuancing and draws out the implication for copyright issues: contrary to current media policy, the wider availability of a work can actually enhance its value.

Coming attraction: Kristin is preparing a blog entry commenting on fair use in the digital age.

Hands (and faces) across the table

DB here:

In books and blogs, I’ve expressed the wish that today’s American filmmakers would widen their range of creative choices. From the 1910s to the 1960s (and sometimes beyond), US filmmakers cultivated a range of expressive options—not only cutting and camera movement but other possibilities too. Studio directors were particularly adept at ensemble staging, shifting the actors around the set as the scene develops.

You can still find this technique in movies from Europe and Asia, as I try to show in Figures Traced in Light and elsewhere on this site. But it’s rare to find an American ready to keep the camera still and steady and to let the actors sculpt the action in continuous time, saving the cuts to underscore a pivot or heightening of the drama. Now nearly every American filmmaker is inclined to frame close, cut fast, and track that camera endlessly. I’ve called this stylistic paradigm intensified continuity.

As Los Angeles agent and former editor Larry Mirisch once put it in conversation with me: “They used to move their actors; now they move the camera.” Most of today’s prominent directors prefer kinetic camerawork and machine-gun cutting. This tends to make their staging rather simple and static: we get stand-and-deliver or walk-and-talk (subject of a blog entry here).

The result is a split in contemporary American style. Action scenes are often gracefully and forcefully choreographed (though sometimes the editing fuzzes up character position and overall geography). By contrast, conversation scenes, which could be choreographed as well, are handled either as a Steadicam walk-and-talk or simply as seated actors talking to one another, with cuts breaking up the lines and the camera on the prowl. (I discuss some examples in The Way Hollywood Tells It, pp. 128-173.) (1) You sometimes suspect that today’s directors are most at home shooting lots of people hunched over workstations, making the principal form of suspense a LOADING command.

Don’t get me wrong. Like all styles, intensified continuity isn’t a bankrupt option; many fine directors, from the Coens to Michael Mann, have worked vigorous variants on it. What I’m arguing for is more plurality, more tones in the director’s palette. I’ve revived these cranky ideas in discussing a single shot, this time in Variety. Today’s blog entry expands on that brief piece, so you may want to hop over to it here before reading what follows.

Directing us

One task facing any director is to direct—not only actors but us. The filmmaker must direct our attention to what’s important for responding to the drama at any moment. Since the late 1910s, we’ve known that close-ups and frequent cutting do just that. Tight framings and rapid cuts can steer the audience’s attention through a scene. So the question becomes: How can you direct attention without using close views and fast cutting?

Well, for one thing you can place the main action in the center of the picture format. If there are several points of interest in the shot, which is usually the case, you can arrange them symmetrically around the central zone of the shot—in film, usually an zone just above the geometrical center of the picture format. You can also position your main players so that the most important ones are closer and/or facing toward the camera. By turning a character away from the camera, you can drive the audience’s eye to someone else. There are other pictorial cues worth mentioning (lighting, color combinations, patterns in the set design), but these will hold us for now. Add in movement—characters shifting their position, especially coming closer to the camera—and you have a suite of cues that a film shot can provide.

Apart from these purely compositional factors, you the director can exploit some cues that are part of our social proclivities. When we watch other people, we’re attracted to areas of high information—which, for creatures like us, are faces and hands. Faces send signals about what people are thinking and feeling, with the areas around the eyes and mouth telling us most. Hands are the source of gestures, as well as potential threats. And of course if someone is speaking and others are listening, we are likely, all other things being equal, to look at the speaker.

The crucial fact is that in ensemble staging all these cues, and more, are at work at the same time. The director’s skill is orchestrating them so that they support one another, guiding us to see this or that. (On rare occasions, the director will use them to misguide us, but let’s stick with the default for the moment.) For a long time, filmmakers knew intuitively how to coordinate these cues to create rich and intricate shots; I fear that they no longer know how. (2)

That’s what makes one passage in Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood of interest to me. The scene presents Paul Sunday explaining to Daniel Plainview that there’s oil on his family’s property. Daniel and Paul are bent over a map on a tabletop, with Daniel’s assistant Fletcher Hamilton and Daniel’s son HW watching. The scene is presented in a single shot, with a slight camera movement forward at the start.

The composition could hardly be simpler: four people lined up, three at the edge of the table. The heads cluster around the center of the format, with HW lower and off-center; no surprise that he’s the least important character in the scene (though his question to Paul foreshadows action in the film to come). Paul is explaining where the oil is, and the two men’s faces and hands command our attention as they speak.

Many directors would have cut in to a close-up of the map, showing us the details of the layout, but that isn’t important for what Anderson is interested in. The actual geography of Plainview’s territorial imperative isn’t explored much in the movie, which is more centrally about physical effort and commercial stratagems.

Questioning Paul about his family, Daniel turns slightly away. This clears a moment for HW to ask about the girls in Paul’s family, and for a moment our attention is steered to the right, to pick up their interchange.

Then Fletcher asks about the farm, and as Paul and Daniel tilt their faces to him, he earns his place in the center of the frame. Before, when we could see the faces of the two men closest to the camera, he was subsidiary, but now he becomes salient. On the left, Daniel shifts away uneasily, turning almost completely away from the camera. In answering Fletcher, Paul turns away in the opposite direction, as if shy or guilty; his awkward gesture of stroking his hat seems to confirm Daniel’s doubts about him.

During a pause, Paul turns back to stare directly at Daniel, saying quietly, “The oil is there.” At the same time, Daniel, still turned away, is exchanging a glance with Fletcher. At this point, Anderson’s training of us pays off: we’re ready to detect the slight shift in Fletcher’s eyes, which confirms that Daniel’s looking at him. “Watch their eyes,” as John Ford liked to say.

Paul sets out to leave, and he refuses the invitation to stay the night. At this point comes the scene’s biggest gesture. Daniel raises his hand, in the dead center of the frame.

Spreading his long, thin fingers, Daniel commands our attention. He seems at once to be halting the young man and threatening him. But the gesture becomes the prelude to a handshake. Daniel’s characteristic blend of bluff assurance, friendliness, and aggressiveness are packed into this single gesture. (At the climax, other gestures will recall this one.)

Daniel steps closer to Paul, blocking out Fletcher, to make his threat: If he travels so far and doesn’t find oil, he’ll find Paul and “take more than my money back.” Paul agrees and moves away. “Nice luck to you, and God bless.”

The men watch Paul leave the building. End of scene.

Without any close-ups or cutting, Anderson has skillfully steered us to the main points of the scene, which are carried by the performers. The drama builds through small changes of position, shifts of weight, and facial expressions that accompany the dialogue. (The somber, plaintive music adds an uneasy edge.) Daniel seems more threatening when we don’t see his reaction, and Anderson’s camera forces us to scrutinize Paul’s expressions and body language for signs that this is a scam. It takes confidence to make a raised hand the climax of a scene, but the gesture gains its force by being the most aggressive moment in an arc of quietly accumulating tension.

All the principles involved here—frontality, spacing of figures, slight shifts of compositional focus, actors’ body language—are simple in themselves, but they gain a strong impact by cooperating with one another. The scene’s quiet obliqueness is characteristic of the film, which, at least until the last few minutes, carries us along with hints about where the action might go and what drives its characters.

Yet simplicity shouldn’t imply simplification. Anderson’s willingness to give the shot several points of interest, some more stressed than others, creates an understated tension. The shot’s gravity stems from its conciseness, a quality that Anderson admires in 1940s studio films like The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.

Two more tabletops

The staging strategies Anderson uses aren’t new, as I’ve suggested. They’re part of the history of film as an art form, and many directors have continually relied on them. I don’t think that this is always a matter of influence, although surely filmmakers learned from watching earlier films. Often, directors working within similar constraints intuitively rediscover what other directors have already done.

Consider this scene from Kurosawa Akira’s The Most Beautiful (1944). The setting is a plant where Japanese workers, mostly girls and women, are manufacturing bombsights. The workers have vowed to increase production for the war effort, and they are working to the point of exhaustion. The plant supervisors are worried that the pace will take its toll on the girls.

The scene starts with the eldest supervisor studying the output chart, lying on a table below the frame edge. His colleagues are turned away, at the window. He is the one who must decide how to keep the girls healthy and the output steady. The table and the window will be the two poles of the action, and the actors will oscillate between them. The process starts when the eldest retreats to the window, and one comes forward to study the report.

He’s followed by his opposite number, and they echo one other in rubbing their necks. They’re as tired as the assembly-line girls. Their superior turns and says that there’s no point in lowering the quota because the girls are so devoted that they’d push harder anyway.

The men have turned to listen to him, driving our attention to his centered, frontal figure. After the elder has turned away again, the man on the right says that this might be the critical juncture. Remarkably, all three men remain turned from us, creating a slight pictorial tension.

This tension is extended when the supervisor on the left states his confidence in the children, their team leader, and their teacher. This makes the eldest turn around.

The speaker walks to the window, arguing that the girls will succeed, but the leader turns away again dubiously. He doesn’t offer a decision because an offscreen voice announces that a teacher has come to see them, and they all turn to look.

The factory’s problem isn’t solved; the seesawing of the staging has presented that irresolution dynamically. In a single shot, the difficulty of the administrative decision has been expressed in counterweighted movements in and out, by the figures’ frontality and dorsality. Again, it can seem simple, but where a contemporary American director would have given us a prolonged passage of stand and deliver, with intercut close-ups, Kurosawa has created a little ballet out of the men’s uncertainties. Like Daniel’s raised hand, but with even less emphasis, the assistant’s plea on behalf of the girls’ commitment has gained a subtle prominence. Yet all he has done is walk to the window.

I’m not saying, of course, that Anderson took the idea from Kurosawa. Given the initial choice to stage the scene behind a table, and the inclination to present the action in one shot, both directors spontaneously drew on basic staging principles. This is what film directors have always done. So as a finisher, here’s one last tabletop interlude from Cecil B. DeMille’s Kindling (1915). The entire scene is a dense and intricate affair, but let’s pick just one moment. Maggie has become a servant to a rich woman, Mrs. Burke-Smith, and she’s about to be arrested for theft. Detective Rafferty is ready to handcuff her, but Mrs. Burke-Smith changes her mind.

DeMille arranges his actors so that we can’t miss the rich woman’s moment of decision. She is in the foreground, and her face is in the upper center of the frame. The other actors are blocked, so that her expression is the only one we can see clearly at the crucial moment. Her hand gesture, stretching across the central axis of the frame, confirms that she won’t charge Maggie. (For a similar use of “blossoming” actors’ movements in 1910s cinema, go here and look at Figs. 2A10-2A11.) What DeMille knew, Kurosawa discovered afresh, and Anderson hit upon it again.

Strategies of staging, like other principles shaping how films tell stories, lie behind each concrete creative decision the film artist makes. They run as undercurrents through film history, almost never discussed by critics. They form a body of tacit knowledge, flowing across our usual distinctions of period, genre, director, national cinema. We can trace continuities and changes, examining how the strategies are revived, revised, or rejected. They can provide us with subtle but powerful experiences. They constitute a skill set that is available to filmmakers today. . . if any will, like Anderson, seize the chance.

(1) True, Wes Anderson keeps the camera still, but in his frontal, family-portrait framings the cutting and line readings do all the work; dynamic staging isn’t on his menu.

(2) I survey the development of these and other tactics in Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style. On this site, for one example go here and scroll down to the Bauer material.

Sleeves

DB here:

Earlier this month, when I was giving a lecture on Mizoguchi Kenji at our university museum, I showed two images from A Woman of Rumor (Uwasa no onna, 1954). It’s a little-known film of his, and it’s probably not up to his finest, but seeing the stills again on the big screen made me want to write about one scene. That scene displays aspects of Mizoguchi’s artistry that I touch on in one chapter of Figures Traced in Light and in the website supplement here.

This blog entry constitutes, I suppose, another supplement. After all, I couldn’t include in the book all the moments in Mizoguchi’s work that I find fascinating. But since comparison is a good way to get under a movie’s skin, my examination of a parallel scene from another movie may have more general interest. Even though Woman of Rumor doesn’t seem to be available on video, maybe looking at this pair of examples would inspire some readers to take an interest in one of the two or three greatest filmmakers who ever lived.

In the court of Regina

William Wyler and John Barrymore.

What a year 1941 was in the American cinema! We remember it for Citizen Kane but it also brought us How Green Was My Valley (a better film than Kane, I think), and items like Sergeant York (the biggest box-office hit), Dumbo, The Philadelphia Story, Suspicion, Ball of Fire, High Sierra, The Lady Eve, Meet John Doe, The Maltese Falcon, They Died with Their Boots On, and one of the most daring movies ever made in America, The Little Foxes.

An adaptation of Lillian Hellman’s play, The Little Foxes offers a study in unbridled capitalism. It shows how economic interests pit the South against the North and white against black. Psychologically, it analyzes a household gripped by the ruthless domination of the matriarch Regina (Bette Davis), the wiliest member of a family of grasping entrepreneurs. Regina has all but flattened her husband and is trying to make her daughter Alexandra oblivious to the family’s corruption.

The Little Foxes was also bold in its style—in its own way, as venturesome as Citizen Kane. It hasn’t been fully appreciated because Wyler is still thought of as a rather middlebrow talent, an overcautious director who toned down the flamboyance of Gregg Toland’s deep-space and deep-focus compositions.

Some day I hope to blog in defense of Wyler, middlebrow movies, and Midcult art in general. That would involve a detailed analysis of Little Foxes. (1) For now let’s just say that Wyler’s direction of the film won the admiration of no less than André Bazin. Bazin taught us to appreciate Wyler’s work, though with some prompting from Wyler and Toland (as I suggest here). Wyler was also appreciated by Mizoguchi, who, apparently grudgingly, told his screenwriter Yoda that he admired Wyler’s use of the “vertical frame.” (2) Later I’ll suggest one way of understanding that phrase. Mizoguchi met Wyler at the 1953 Venice Film Festival, when Ugetsu Monogatari was up against Wyler’s Roman Holiday for the Silver Lion.

One scene not discussed by Bazin or Mizoguchi, as far as I’m aware, has always gripped me. Regina’s brother Oscar has a wife, Birdie, who has turned into a passive alcoholic. Birdie has learned of plans to marry Xan off to Leo, her shallow son. Her will has been broken by Regina and Oscar, but she summons up the courage to blurt out to Xan that she mustn’t marry Leo, no matter how strongly the family insists. Xan, who has no inkling of how her family twists people to suit their ends, protests that no such thing could happen. But Oscar overhears Birdie warning Xan off.

Birdie and Oscar are about to leave at the end of the evening. Wyler begins with a standard two-shot, very slightly off-center. But as Birdie frantically warns Xan, Oscar’s sleeve and pant leg appear in the lower left of the frame, with the swagged curtain at the doorway hiding his face.

For us, this creates suspense. Only after Birdie has babbled out her warning do the two women notice he’s there. Xan, not knowing how Oscar abuses Birdie, heads off to bed.

As she climbs the staircase (very important in the film and the original play, this staircase) and heads off to her bedroom, Wyler’s camera arcs to reveal Oscar. Wyler now cuts to show, more or less from Birdie’s point of view, Xan going into her room.

Birdie watches anxiously, then turns to face Oscar, with a look of resigned apprehension.

Again suspense: Oscar won’t punish Birdie with Xan watching, but the girl’s departure puts Birdie in jeopardy. In addition, Wyler’s shot of her reaction anticipates the wrath she’ll face. (Patricia Collinge’s fluent performance is equal to the dynamics of Wyler’s visuals.) These cuts anchor our empathy; Wyler has been saving the close-up of Birdie for this moment.

We return to the master framing as Birdie heads toward Oscar, passing into a patch of shadow. As she does so, he raises his hand abruptly.

Wyler cuts to a two-shot. Oscar slaps Birdie so hard she seems to bounce against the left frame edge. She cries out and then tries to stifle her voice—a psychologically apt gesture for this woman who muffles her sorrows throughout the film.

Again, Wyler daringly sets a key action off-center. The brutal discontinuity of the cut, which crosses the axis of action and sharply changes shot scale, accentuates Oscar’s violence. It’s also rather elliptical; run the cut slowly, and you never see his hand strike her.

Xan hurries out of her room and comes to the banister, her face on the upper right balancing the placement of Birdie’s in the prior shot. In the next shot, we see, over her shoulder, Oscar stride out. Birdie follows meekly, assuring Xan that nothing’s wrong. The coda of the scene will emphasize Xan’s puzzled anxiety, a phase in her process of coming to understand the domineering fury that rules her family.

Low- and high-angle shots like this last pair recur throughout The Little Foxes, and I suspect that these are the sorts of thing Mizoguchi was invoking in mentioning Wyler’s “vertical” space. Wyler’s steep angles activate upper areas of the frame that many American directors hadn’t explored.

The act of overhearing a revealing conversation is a standard dramatic convention, but Wyler has refreshed and nuanced it. We know how it would be normally handled. We’d see either a shot showing Oscar stepping fully into the background, or a series of cuts showing first Birdie and Xan and then Oscar listening and watching. Wyler revises the standard schema, taking it for granted that we can pick up on a subtler cue than usual: just a bit of Oscar’s body intrudes.

As a result we have to be more alert. The information isn’t centered, but rather tucked into the lower left. And this option conceals Oscar’s face. Not that we’re doubting he’s angry, but delaying showing his anger builds up greater tension. Wyler, unlike today’s directors, knows when to build up to revealing things that we anticipate, making the final outburst more forceful when it comes. Further, the rest of the scene continues to deny us a clear view of Oscar’s anger, all of which gets squeezed into his gesture of slapping Birdie. It’s Birdie’s reaction that Wyler stresses, and Oscar’s contempt for her is conveyed simply by his bearing, his gesture, and his manner of stalking out of the foyer.

It’s not too much to talk about rigor here. The schemas dominating today’s filmmaking, the stylistic paradigm I call intensified continuity, would demand tight close-ups of everybody from the start. But providing them would make it harder for Wyler to raise the emotion when the startling slap comes. Maybe a contemporary director would render this spike in slo-mo, or with a wobbly handheld camera, but that tends to seem overbearing and pumped-up—as a lot of current stylistic pyrotechnics do. In any case, I’m betting that no American director today would use Oscar’s sleeve in the quietly ominous way Wyler does.

Mizoguchi’s game of vision

Mizoguchi Kenji, in glasses, during the making of Ugetsu.

Mizoguchi is renowned for his long takes, which are often sustained in distant views featuring considerable camera movement. In the Mizo chapter in Figures Traced in Light, I suggest that these stylistic choices spring from his effort to engage the viewer mesmerically—as he put it, “to work the viewer’s perceptual capacities to the utmost.” He asks us to downshift our attention to the finest details of the action, which he then modulates for expressive effect. I draw examples from various films across his career to show how he creates drama out of remarkably slight differences in character position, lighting, and other factors.

But what happens when he foreswears virtuoso camera movements and single-take scenes and breaks the drama up into several shots? Today, many ambitious directors seem to take pride in stretching out their takes, so cinephiles are sometimes inclined to see a cut as a loss of nerve and a concession to the audience. But I try to show in Figures that Mizoguchi sustains his concern for nuance when he creates an edited sequence. The modulation of fleeting details is to be found in his closer shots too.

In A Woman of Rumor, Hatsuko runs a teahouse that funnels customers to the geisha establishment behind it. She has tried to protect her daughter Yukiko from the shame of her profession. Hatsuko has also been cultivating a young doctor she hopes to marry, giving him money to set up a clinic. Now the doctor, Matoba, has become attracted to Yukiko. The scene I’m examining takes place during the performance of a noh drama. Hatsuko leaves the auditorium and finds Yukiko talking with Dr. Matoba.

As she passes around a screen, she hears Yukiko saying she wants to learn piano in Tokyo. Hatsuko looks left, and Mizoguchi cuts to an approximation of her optical point of view on the couple in the lounge.

So far, so conventional. Mizoguchi seems to follow the intercutting option for treating a scene of overheard conversation. But he goes further. Having laid out the action, Mizoguchi starts the lesson in just-noticeable-details . . . with a sleeve. He cuts to a reverse shot putting Matoba and Yukiko in the foreground. Hatsuko is still back there, though. We can see her kimono sleeve on the left, poking out from behind the screen.

A sharp-eyed viewer might also spot Hatsuko’s shadow on a wall, in the center of the shot, over Matoba’s shoulder. This blow-up shows both the sleeve and her silhouette.

Here, friends, is one reason we want to watch films in 35mm, and projected really big.

It’s now that Yukiko says that she may leave her mother, and Matoba replies, “Maybe I’ll go too.” This is devastating to Hatsuko. The two people whom she loves most seem to care nothing for her. Her shocked reaction is given in a medium-shot showing her shifting out from behind the screen, her face partially hidden.

Mizoguchi has picked one variant of the overheard-conversation schema: shot of speakers/ reaction shot of eavesdropper. But he’s done so in his own way, using the barely discernible kimono sleeve to signal Hatsuko’s presence in the full shot of the couple. Likewise, the shot of Hatsuko listening is far from the usual close-up. Like other Japanese directors, Mizoguchi was fond of this arresting single-eye image. He used it earlier in his career, as shown in the first frame at the top of this entry, from Hometown (Furusato, 1930). The second frame is the last shot of his last film, Street of Shame (Akasen chitai, 1956). Quite a shot to end your career on, I’d say.

Most Japanese directors use this single-eye framing as a one-off flourish, but not Mizoguchi. The device epitomizes his demand that we concentrate on a detail. Isolating half a face gives impact to the slightest shift in the eye and eyebrow. Moreover, the split face reappears as a pictorial motif later in the scene.

As Matoba says he’ll go back to Tokyo for his doctorate, Mizoguchi cuts back to the setup for the second shot. Hatsuko moves left to sit on a chair around the corner from the sofa. This prepares for another, more prolonged game of visibility.

Now we get a thirty-second take of the couple on the sofa. As the scene develops, it becomes evident that Matoba is seducing Yukiko. Hatsuko slips in and out of visibility, her actions responding to and even echoing Matoba’s pressure on the girl. First, as he talks with Yukiko, we see Hatsuko’s sleeve and shoulder, between the vase and his shoulder. But as he slips his arm around Yukiko, her elbow moves aside, in an echo of his gesture.

Then, when Matoba presses his attention (“We’ll help each other . . . Depend on me”), Hatsuko’s face pops into view as her fingers emerge to grip the edge of her chair. Mizoguchi then lets her face subside, again slicing it in half.

In effect, this shot replays and expands upon the tactic governing the earlier two shots. Again we get the just-noticeable presence of the sleeve, but now rhyming with the action in the foreground. And again we get the facial reaction, impeded by a vertical cutoff, but this time in the distant shot rather than in a closer view. It turns out that those first four shots were training us for this more intricate game of vision.

At the moment Hatsuko’s face is sliced in half, Mizoguchi cuts. Now he prolongs the close view as he had extended the full shot of the couple. In this thirty-second shot, we watch her reaction, played out in slight modulations—changes in her facial expression, changes in the aspect of her face that we see, and changing relations to the curling palm plant in the vase before her.

We get a new angle on Hatsuko, slightly high, as Matoba says, “I’ll tell her.” Hatsuko stands up abruptly and the camera tilts to follow her.

With the simple action of her rising up, Mizoguchi changes his composition sharply. Hatsuko’s position in the frame changes only a little bit, but the massive vase on the left gives way to the curling stalks on the right. Radically refreshing a shot through minimal means is one felicity of Mizoguchi’s art.

Then, as if the full import of Matoba’s betrayal dawns on her, Hatsuko lowers her head sadly. Again her eyes are split up, this time thanks to the twisting stalk. In a characteristic Mizoguchi gesture, she turns from the camera, as if ashamed to face us, but also summoning up reserves for the next emotional shift.

When she turns back, her face burns.

I take this to be the scene’s emotional climax. Mizoguchi could have given it to us much sooner, by having Hatsuko turn angry as she peeped out from behind the screen. Instead, his game of vision allowed him to build patiently toward this unimpeded shot of her reaction. It prepares us for the next stages of the drama, later scenes in which she will confront her patron and launch jealous accusations at Yukiko.

Now we hear the performance ending, and Hatsuko lifts her head. This phase of the scene ends when Mizoguchi cuts to audience members coming into the lounge and greeting her.

By 1954 Mizoguchi had surely seen The Little Foxes. Had he decided to redo Wyler’s virtuoso staging in his own manner?

Both directors work with similar ingredients: overheard conversation, depth shots, judicious close-ups, and partial views. But the narrational weightings differ. Wyler’s film aligns and allies us with the people talking, whereas A Woman of Rumor ties us to the listener. (3) Wyler’s eight shots take eighty-one seconds; Mizoguchi’s eight shots take about two minutes.

Wyler’s handling is brisk, tense, and remarkably nuanced within the Hollywood tradition. Mizoguchi gives us his scene more sedately, wringing just-noticeable differences out of unassertive performances and simple elements of setting. No slap here, just a drama of wounded pride, lost love, and jealousy played out in the face, back, and sleeve of Tanaka Kinuyo, shifting behind a floral arrangement. What Wyler gives us as one sharp effect, Mizoguchi turns into a delicate, prolonged game of vision.

Am I fussing over minutiae? No; Wyler and Mizoguchi did. We just have to follow where they lead. As I try to show in my essay on blinking in cinema (4), directors attend closely to things that might seem trivial. Our analysis needs to be as fine-grained as their craft and artistry.

Oh, yes: at Venice Ugetsu won the Silver Lion. Wyler had to be content with Roman Holiday’s three Academy Awards.

(1) I sketch some of the possibilities in On the History of Film Style (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), 225-227.

(2) For more on Mizoguchi’s competition with Wyler, see Figures Traced in Light (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 134.

(3) I’m referring to Murray Smith’s deft analysis of what he calls alignment and allegiance in our relation to film characters. See Engaging Characters: Fiction, Emotion, and the Cinema (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), Chapters 5 and 6.

(4) “Who Blinked First?” in Poetics of Cinema (New York: Routledge, 2007), 327-335.

PS 3 December: Thanks to Michael Kerpan for a name correction, and for the information that Woman of Rumor was once available on a French DVD.

PPS 27 February 2008: Good news. Now Woman of Rumor is available on the wonderful Eureka! Masters of Cinema series, along with the superb Chikamatsu Monogatari. The discs come with voice-over commentary by Tony Rayns and essays by Keiko McDonald and Mark LeFanu.

Charlie, meet Kentaro

DB here:

Echoing an earlier virtual roundtable on this blog, I want to write about my two favorite B film series, now available in handsome DVD boxed sets. Both series were mounted at 20th Century-Fox, both were adapted from genre fiction, and both seem very much of their time: lots of exotic Orientalia, and probably too many middle-aged men in tiny mustaches and broad fedoras. But to my mind these films offer brisk, unpretentious entertainment, solidly crafted and surprisingly subtle. They also allow us to trace some changes in the ways movies were made across the 1930s.

There’s another reason for this blog. Tim Onosko, a friend of Kristin’s and mine, recently died after a battle with pancreatic cancer. Tim was an extraordinary figure, as you can find here. He was central to Madison film culture for forty years, and in his various creative activities, he shaped everything from The Velvet Light Trap to Tokyo Disneyland. He and his wife Beth also made a documentary, Lost Vegas: The Lounge Era. Tim and I enjoyed talking about the two series I’ll be mentioning. He loved these films, as he loved all films and popular culture generally, with a sharp-eyed dedication. So this is a small effort at an homage to Tim.

The Hawaiian and the Japanese

Charlie Chan, a Hawaiian police inspector of Chinese ancestry, became famous in a series of six novels by Earl Derr Biggers, from The House without a Key (1925) to The Keeper of the Keys (1932). Chan novels were brought to the screen at the end of the 1920s by Pathé and Universal, but for Behind That Curtain (1929) Fox took over the franchise. Warner Oland, a Swedish-born actor who had often played Asians, settled into the lead role in Charlie Chan Carries On (1931). He played Chan up through Charlie Chan at Monte Carlo (1937), then fled Hollywood under peculiar circumstances and went to Sweden, where he died soon afterward.

The Mr. Moto films overlapped with the Oland cycle. John P. Marquand introduced Moto in the novel No Hero (1935) and made him more central to four novels that followed. Again, Fox bought the rights and launched the film series with Thank You, Mr. Moto (1937). It starred Peter Lorre as the mysterious Japanese, and I think it’s fair to say that the role made him a Hollywood star. The series ran for eight installments, ending in 1939 with Mr. Moto Takes a Vacation.

The Mr. Moto films overlapped with the Oland cycle. John P. Marquand introduced Moto in the novel No Hero (1935) and made him more central to four novels that followed. Again, Fox bought the rights and launched the film series with Thank You, Mr. Moto (1937). It starred Peter Lorre as the mysterious Japanese, and I think it’s fair to say that the role made him a Hollywood star. The series ran for eight installments, ending in 1939 with Mr. Moto Takes a Vacation.

Each series echoed its mate. Tim claimed that in an early Chan, a character is reading a Moto story in the Saturday Evening Post, though I’ve never found that scene. When Charlie’s Number One Son turns up to help Moto in Mr. Moto’s Gamble (1938) it’s revealed that Charlie and Moto are old friends. There’s a more elegiac moment in Mr. Moto’s Last Warning (1939) when a theatre displays a poster for the Chan series—perhaps as well serving as an homage to the recently deceased Warner Oland. Despite Oland’s death, the Chan series continued until 1949, with Sidney Toler in the role, but with Lorre’s departure the Moto films ceased.

Having a Caucasian actor play an Asian protagonist was common at the time. Today, it seems condescending or worse, but we should recognize that the films featured Asian actors as well, often in significant roles. The most visible example is Keye Luke as Charlie’s highly Americanized son. Forever blurting out “Gosh, Pop!” Luke is a lively and likable presence.

Just as important, the portrayal of the detectives is remarkably free of racism. Charlie and Moto are clearly the quickest-witted characters, and both prove resourceful in all kinds of ways. Moto’s judo subdues thugs twice his size, and Charlie is up-to-date in the new technologies of detection.

The scripts go out of their way to show both men skilfully handling the prejudice they encounter. In Charlie Chan at the Opera (1936), a blatantly racist cop (William Demarest) who calls Charlie “Chop Suey” is mocked incessantly by everyone, most gently by Charlie. Moto excels at pretending to be the stereotypical Asian (“Ah, so!” “Suiting you?”). And both our protagonists are sympathetic to others who are in minorities. Charlie is notably unwilling to participate in guying black servants as the whites do, and Charlie Chan at the Circus (1936) shows his keen sympathy with the “freaks,” treating them with quiet courtesy. The Moto series presents a Japanese who doesn’t seem to share his country’s goal of ruling Asia. In Thank You, Mr. Moto, he enjoys a respectful friendship with a Chinese family of declining fortunes.

The Chan series features straightforward detection. A murder is committed, and either Charlie is in the vicinity or the police ask for his help. A young and innocent couple is involved, adding pressure for Charlie to solve the case. Another murder is likely to take place, and a few attempts are made on Charlie’s life before he comes to the solution. In traditional fashion he tends to assemble all the suspects at the climax before exposing the guilty party.

The Chan series features straightforward detection. A murder is committed, and either Charlie is in the vicinity or the police ask for his help. A young and innocent couple is involved, adding pressure for Charlie to solve the case. Another murder is likely to take place, and a few attempts are made on Charlie’s life before he comes to the solution. In traditional fashion he tends to assemble all the suspects at the climax before exposing the guilty party.

The Moto films aren’t as concerned with puzzles. Like the novels, they’re tales of international intrigue, involving smuggling, theft of archaeological treasures, and the like. There’s more violence and physical action, with shootouts and last-minute rescues. Moto Kentaro (his given name is visible only on his identity card) is a more shadowy presence than Charlie, often working under vague auspices. He’s either an agent of Interpol, a functionary of the Japanese government, or an exporter who takes up intrigue as a hobby. (1) In Mr. Moto’s Gamble, arguably the best of the series, he engages in old-fashioned detection involving murder during a boxing match. Unsurprisingly, the film was originally planned as a Chan vehicle, and it even includes Number One Son as Moto’s sidekick.

The Moto films aren’t as concerned with puzzles. Like the novels, they’re tales of international intrigue, involving smuggling, theft of archaeological treasures, and the like. There’s more violence and physical action, with shootouts and last-minute rescues. Moto Kentaro (his given name is visible only on his identity card) is a more shadowy presence than Charlie, often working under vague auspices. He’s either an agent of Interpol, a functionary of the Japanese government, or an exporter who takes up intrigue as a hobby. (1) In Mr. Moto’s Gamble, arguably the best of the series, he engages in old-fashioned detection involving murder during a boxing match. Unsurprisingly, the film was originally planned as a Chan vehicle, and it even includes Number One Son as Moto’s sidekick.

Looks and looking

We can learn a lot by studying the two main actors’ performance styles. The plump Oland plays Chan as stolid but not ponderous. He floats across a room and gravely circulates among suspects, giving the films their deliberate pacing. Oland’s drawn-out delivery and pauses were due, people say, to his acute alcoholism, but he never seems to be struggling to find his lines. Charlie is at pains to be unobtrusive, modest, and tactful; his characteristic gesture is a simple one, letting the fingertips of one hand grasp one finger of the other.

He is a loving father, doting on his many children (all in tow in Charlie Chan at the Circus). Although Number One Son may exasperate him, you would go far in films to find as warm a portrayal of a father’s affectionate efforts to curb an impulsive boy. See Charlie Chan at the Olympics (1937) for the casual byplay between Charlie and Lee, now an art major and a member of the swimming team. Lee’s bubbling energy gives Charlie’s imperturbability even greater gravitas.

The short and slim Lorre plays Moto as a suave man-about-Asia, hand thrust casually into his trouser pocket. Moto is an art connoisseur, a graduate of Stanford (class of ‘21), and a master of many languages. Lorre, so easily caricatured at the time and now, hit on a brilliant idea: He didn’t give Moto stereotyped tricks of pronunciation. Unlike Oland, he didn’t usually drop articles or compress syntax.(2) Lorre just played the part in his lightly accented English, as he would in The Maltese Falcon and Casablanca. He added a soft-spoken delivery, a modest smile, and a trick he may have picked up from Marlene Dietrich–ending his sentences with a slight upward inflection, turning every statement into a polite question.

Reaction shots of suspects are a convention of these movies, but after several cuts show us everybody looking shifty, the reverse shots of our heroes show us that they miss none of this byplay. (3) Charlie is alert, but he hides his penetrating view behind a bland courtesy. As Moto, Lorre presents a more aggressive intelligence. Peering through round spectacles, those bug eyes, panic-stricken in M, can now become pensive or bore into a suspect. Charlie needs the force of law, but Moto, who usually acts alone, is dangerous by himself, and Lorre’s horror-show pedigree serves him well in giving his hero’s stare a sinister edge.

Listening and looking

You can argue that Oland and Lorre, coming to their parts only a few years after sound had arrived, helped Hollywood develop a wider array of acting styles. We historians of Hollywood have rightly praised gabby comedies like Twentieth Century (1934) and It Happened One Night (1934) for finding a performance technique suited to sound films, particularly in the wake of technical improvements in acoustic recording. If movies had to talk, we think, they should really talk, fast and hard and heedlessly. In this church our Book of Revelations is His Girl Friday (1940).

Lorre and Oland, like Karloff and Lugosi, remind us of the virtues of being gentle, spacious, and deliberate. This isn’t a reversion to those hesitant, strangled mumblings of the earliest talkies. Rather, the movies’ plots surround our Asians with rapid-fire duels of cops and reporters, snapping out “Say!” and “Hiya, sister!” and “Watch it, wise guy!” and “Don’t be a sap!” Against clattering percussion Moto and Charlie deliver a melodic purr.

Some people still believe that in Citizen Kane Welles and Gregg Toland introduced American film to steep low angles, tight depth compositions, and noirish lighting. In The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I’ve argued that the Gothic, somewhat cartoonish look of Kane synthesized and amplified trends that were emerging during the 1930s. The Chan and Moto films are wonderful places to study these visual schemas.

E

E

In Charlie Chan in Egypt (1935, above), cinematographer Charles G. Clarke (whom Kristin and I interviewed for the Hollywood book) offers flashy depth and silhouette effects, and nearly all the Chan films have moments of clever staging. Charlie Chan at the Opera, above, is particularly engrossing, with its huge set (recycled from the A-picture Café Metropole, 1937). The same film, incidentally, contains scenes of a fictitious opera, Carnival, composed by Oscar Levant. This was an ambitious gesture for a B film and looks forward to Bernard Herrman’s Salammbo sequences of Kane.

The Motos are even more remarkable. You want wild angles? Venetian-blind shadows? Telltale reflections in eyeglasses? Swishing bead curtains? Twisted expressionist décor? You’ve come to the right place.

Some late thirties Fox sets seem to have been stored in Caligari’s Cabinet. Watching these films, it becomes clear that Kane applied the moody technique of crime and horror films to ambitious drama. One bold setup in Mr. Moto’s Gamble looks like a dry run for a Toland big-foreground composition (done here, as often in Kane, through special-effects). I like this shot so much I used it in Figures Traced in Light.

Yet all this creativity took place within severe constaints. These were B pictures, running under seventy minutes and shot in a month or so. Three or four would be released each year. They shamelessly used stock footage, leftover sets, and the same players in different roles from film to film. (Watch for Ray Milland, Ward Bond, and others on the way up.) The boys in the Fox cutting room seem to have enforced a remarkable uniformity: most of the Chans in these DVD sets, regardless of director, contain between 600 and 660 shots, while the faster-paced Motos average between four and six seconds per shot. The actors created hurdles too. Oland sank even further into drinking while the high-strung Lorre was addicted to morphine and periodically retired to sanitariums to recover. Those were the days; rehab wasn’t yet a matter for infotainment.

The Fox DVD boxes are model releases. The prints are well-restored (better on the second sets than the first) and filled with astute, informative supplements. We get a lot of detail about production matters, including why Oland left Hollywood. There is welcome biographical background on master minds like Sol Wurtzel and Norman Foster. I still want to know more about James Tinling, though; his direction of Mr. Moto’s Gamble and Charlie Chan in Shanghai (1935) belies his reputation as a hack.

“The cinema is not dangerous,” Moto reassures the Siamese tribesmen about to be filmed in Mr. Moto Takes a Chance (1938). Immediately, the woman who’s being filmed dies. The adventure begins. Who can resist movies like these? They have kept me happy since my childhood, when I watched them on Sunday afternoon TV. They can keep your children, and you, happy too.

For some good reading, see John Tuska, The Detective in Hollywood (Doubleday, 1978); Charles Mitchell, A Guide to Charlie Chan Films (Greenwood, 1999); Howard M. Berlin, The Complete Mr. Moto Film Phile: A Casebook (Wildside, 2005); and Stephen Youngkin, The Lost One: A Life of Peter Lorre (University Press of Kentucky, 2005).

For more on Charlie, click here. Charles Mitchell has a nice wrapup on Kentaro here.

(1) The involvement of an innocent romantic couple was a convention of slick-magazine fiction of the day (both the Chan and Moto novels were serialized in the Saturday Evening Post), and it recurs throughout mainstream detective fiction of the 1930s. Most writers of the period wrestled with the problem of how to make the couple interesting. See Carter Dickson/ John Dickson Carr’s short story, “The House in Goblin Wood,” for a brilliant handling of the device.

(2) As many commentators have noted, Charlie doesn’t speak pidgin English; he seems to be mentally translating. Interestingly, the generation gap is apparent here too, since Number One Son speaks peppy and perfect American slang.

(3) One hyperclever moment in Mr. Moto’s Gamble gives us the usual rapid-fire array of single shots of discomfited suspects but neglects to show us the real culprit.