Archive for the 'Film technique: Screenwriting' Category

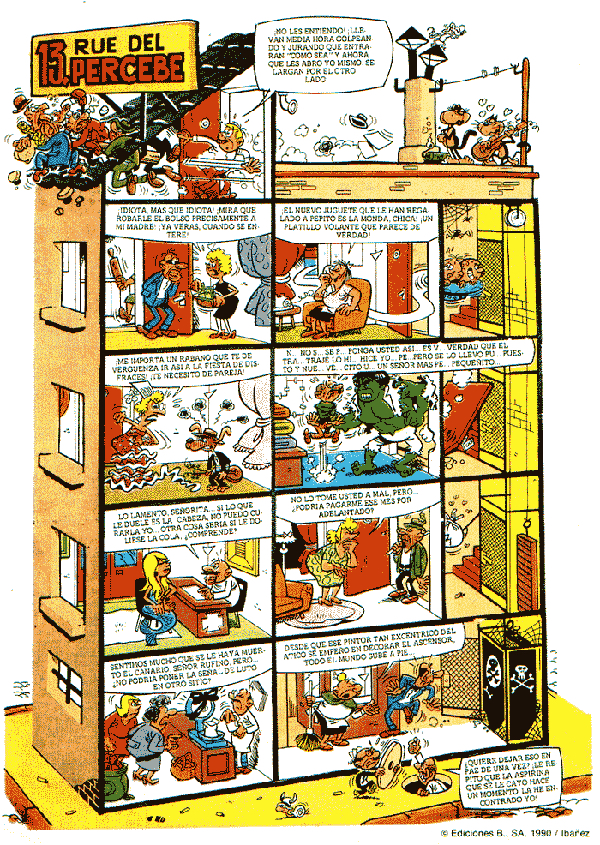

THE TRIAL OF THE CHICAGO 7: Aaron Sorkin samples the menu

The Trial of the Chicago 7 (2020).

DB here:

Love him or hate him, you have to admit that Aaron Sorkin has carved out a unique position in contemporary Hollywood. If we want to understand craft practice from the position of media poetics—that is, the principles governing form, style, and theme in particular historical circumstances—we can usefully look at him as a powerful example.

He’s more than merely typical, of course. In an era when the f-word exchanges of Palm Springs pass muster as comic dialogue, it’s refreshing to watch a movie where smart characters, sparring for high stakes, make a retort that’s more stinging than a slap in the face. These movies are written through and through, and in distinctive ways.

More broadly, Sorkin’s distinctive career invites us to consider the nature of innovation and originality in the popular arts. Because of “progressive” accounts of art history, we’re inclined to emphasize the shock of the (utterly) new as the mainspring of change and the central source of quality. The history of modern painting is written as a series of breakthroughs after Post-Impressionism, from Cézanne through Picasso and Mondrian and so on—the leap to abandon the past, the “next logical step” in an advance toward…what? Abstract Expressionism? Then what? Similarly, from Wagner to Strauss to Schoebberg to Berg to Webern and then…? Boulez? And…?

If the history of an art is a surging procession of avant-gardes, what then do we do with the artists who don’t fit? There are eccentrics, such as Balthus or Satie, who turn out to “point forward” at angles and detours that the linear-progress story doesn’t allow. What about those artists who refine or revise tradition in fresh ways? Where do we put Deineka, recently noticed as no mere Socialist Realist hack, or Shostakovich and Sibelius? Or, in the orthodox history of the detective story (whodunits surpassed by hardboiled), Rex Stout?

In the popular arts particularly, we should expect to find historical patterns less like the Breakthrough Canon, a high-altitude survey of outsize rock formations, than something closer to the ground. Studying mass entertainments like film and popular fiction, we’re likely to find valleys revealing unexpected views of familiar landscapes. There are daisies in the crevices.

In contrast to the Breakthrough account, non-western art traditions valorize accumulation of options and preservation of precedent. An artist earns acclaim for finding fresh ways to realize long-standing craft principles. The Japanese renga poet, the Chinese painter or calligrapher, and the Ottoman carpet weaver revise inherited techniques to reveal new expressive possibilities. Actually, in the West we have the same situation. Come down from the bird’s-eye view, and we’ll see the same fine-grain fluctuations. E. H. Gombrich pointed out how painters, the masters and the minor players, develop their pictures on the basis of inherited patterns—schemas that they have learned and that provide a point of departure for original treatment.

In several places I’ve proposed that filmmakers work with schemas too—pictorial ones, but also narrative ones. The shot/reverse shot technique is a schema, but so is the framed flashback, the four-part plot, and the strategy of beginning your action at a point of crisis.

You see where I’m going with this. Sorkin is worth studying, I think, as a very skilled craftsman. Surveying just a few of his films showed me that he finds ingenious and sometimes powerful ways to rework the schemas from the tradition of American filmmaking—and, of course, from the theatre.

Ventilating the play

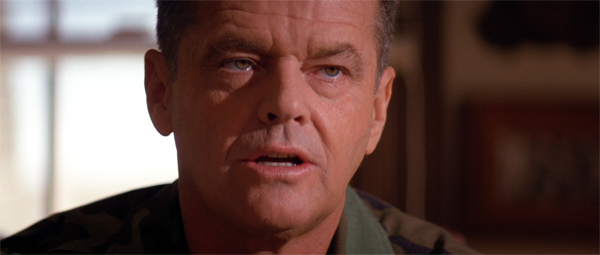

A Few Good Men (1992).

If you want to reach a broad audience in today’s American cinema, you need to either make films with large doses of physical action (as crossover indie directors have found) or to find a signature identity that cultivates a following. In Sorkin’s case, he has dared to rely on plot, dialogue, and a distinct worldview that he has managed to make entertaining. Sorkin’s first plays, followed by the huge stage success of A Few Good Men (1989), typed him as a “theatrical” talent. But over thirty years his film projects sought to “cinematize” what’s usually considered stage technique.

The obvious example is his reliance on “walk and talk,” the long backward tracking shot covering characters striding toward us and spitting out dialogue rapidly. This develops the verbal drama while also yielding some attention-grabbing visuals. But there are less apparent ways Sorkin has blended theatrical technique and cinematic narration.

Early twentieth-century playwrights tended to put the “point of attack”–the moment in the story when you start the play’s plot–fairly close to the climax. Associated with Ibsen and other pioneers of “new theatre,” the late point of attack was a solid convention by the 1910s. As in A Doll’s House and Ghosts, the action starts at a point of crisis, and offstage events leading up to it get revealed through dialogue, sometimes called “continuous exposition.”

The trial schema is a good example of the crisis structure. Typically a trial starts after a lot of stuff has already happened, so the continuous exposition is supplied through testimony and speeches by the defense and prosecution. By 1915, Elmer Rice’s play On Trial was inserting flashbacks that reenacted trial testimony, but some plays stick only to what happens in the courtroom. The Off-Broadway production of A Few Good Men used that linear, present-tense premise, in the vein of earlier plays like The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial (1954) and Inherit the Wind (1955). The investigation of the death of a young Marine is pursued by a prosecution team running up against the military code and a couple of hard-headed officers.

But in preparing the film version, Sorkin adapted to the menu of storytelling options on offer in 1990s moviemaking. For instance, the opening scene could be a grabber, a strong moment that aroused curiosity or suspense. (This might have been a reaction to the need to grab the viewer who’d later see the movie on cable or video.) So instead of letting everything be recounted in the trial, Sorkin’s screenplay for A Few Good Men chose an earlier moment in the story action–a literal “point of attack” showing Dawson and Downey assaulting Santiago.

Later, Sorkin ventilates the play in a traditional manner, supplying scenes that present the prosecutors taking the case and investigating the circumstances. The courtroom scenes don’t begin until about an hour into the film, and they alternate with strategy sessions among the legal team and the defendants. The result is a “moving spotlight” narration, mostly attached to Kaffee the lead prosecutor and Lieutenant Commander Joanne Galloway, but ready to shift to other characters.

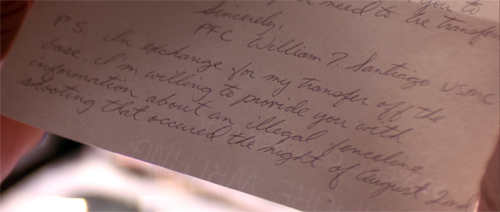

The timeline is chronological, except for a brief flashback dramatizing a letter initially voiced by Santiago. He appeals to Colonel Jessep to transfer him out of the unit for medical reasons. In exchange he offers to give information about an illicit fence-line shooting.

The flashback modulates to Jessep reading the letter aloud (an audio hook) and considering how to handle the situation.

This narration, shifting us from one group of characters to another, gives us a glimpse of the hidden story that the prosecutors need to uncover. The question will become not whether the officers overstepped their authority, but how they will be caught.

After A Few Good Men, we can see Sorkin’s cinematic career as exploring the creative space opened up in the 1990s, a space I’ve tried to map in The Way Hollywood Tells It and several blog entries. For one thing, there’s the matter of how to pick a protagonist.

It seems to me that the film version of A Few Good Men makes Kaffee the protagonist, with Joanne and Sam Weinberg as helpers–just as Jessep is the ultimate antagonist, with Kendrick as his helper. Centering on Kaffee and making him a gifted but glib and cocky young lawyer fits Cruise’s emerging star persona (Top Gun and The Color of Money of 1986, Cocktail of 1988). Sorkin has given us other single-protagonist plots, such as Charlie Wilson’s War (2007), Moneyball (2011), and Steve Jobs (2015).

We may identify Sorkin more with ensemble, or multiple-protagonist, plots because of the fame of his TV shows Sports Night (1998-2000), The West Wing (1999–2006), Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip (2006–2007), and Newsroom (2014-1016). A long-form series permits constant shifting of the protagonist role across a season. But in feature films, I think, a genuine equality among several protagonists is more common in “network narratives” than in crowded films like The Women (1939) and Ocean’s 11 (2001). In the latter, there tends to be a “first among equals”: one or two main characters whose fates are most important, even if subplots centering on others are woven in. Such is the case, I’ll argue, with The Trial of the Chicago 7.

Scanning the menu

Molly’s Game (2017).

Sorkin’s preferred artistic strategies emerge even more clearly, I think, in his handling of narrative structure. He has more or less systematically surveyed a range of storytelling possibilities.

Politically liberal but narratively conservative, The American President (1995) presents an utterly linear plot. As in other romantic comedies, the central couple shares the protagonist role. Their relationships change as they make decisions and respond to external forces. The film plays out the familiar Hollywood double plotline of love versus work: political pragmatism threatens the President’s affair with a lobbyist for environmental reform. There are no flashbacks or fancy time-juggling, and the dialogue is classic flirtation, wisecrack, and one-upsmanship. The one “Fuck you!” becomes a shocking turning point, a test of friendship.

The crisis structure in The American President is presented as a race against time to line up support for two White House bills. Moneyball (2011) creates a comparable pressure on its protagonist. After his baseball team’s loss and the departure of his top players, Billy Beane faces the need to rebuild his roster for the new season. In a classic problem/solution plot layout, he finds a helper in statistician Peter Brand. Again, the plot is mostly linear, though interspersed with summary montages of sports coverage and brief flashbacks to Billy’s own failed ballplaying career.

The fragmentary flashback that carries its own mystery was a common technique of 1990s cinema (e.g., The Fugitive) and remains a standard tool of filmic storytelling. Sorkin’s films use it often, usually to gradually reveals what’s driving the protagonist’s struggle. A version of “continuous exposition,” the flashback allows deeper character revelation; it can liven up the more static sections of the film; and it can provide its own little mystery revelation. In the Moneyball flashbacks we see Billy recruited, decide to give up a college career, and then face failure. This shows how he could have empathy for the second-tier players who are cast aside–and whom Brand’s moneyball algorithms give a second chance.

The time structure is a little more complicated in Charlie Wilson’s War. Here Sorkin samples another option in the schema menu. The story’s crisis is over; the plot starts at the epilogue. After a credits-sequence montage, we’re taken to a CIA awards ceremony, at which Charlie Wilson is honored for working strenuously against the USSR for thirteen years. This scene turns out to be a frame around an extensive flashback.

What follows deflates this high-flown tribute, as we go back to 1980 and see the reprobate congressman pressured into helping the Afghan people by finagling clandestine US investment in fighting the occupying Soviet troops. Other subplots, including an investigation of Charlie’s partying ways, are interwoven. The long flashback concludes and the film’s final sequence returns to the ceremony, with a replay of a grinning Charlie getting his award. The ABA structure makes the whole public event a charade, underscored by a final title: “And then we fucked up the endgame.”

By contrast, Molly’s Game is more fragmentary. We start with a teenage Molly Bloom in a skiing competition qualifying for the Olympics, but an accident knocks her out of the running. This early passage is in turn interrupted by brief flashbacks to earlier in her childhood, of other competitions and accidents and recoveries, overseen by her demanding father. Her first-person voice-over fills in the background, echoing the fact that the story is drawn from the book she’s written (both in real life and in the film).

“None of this has anything to do with poker,” a title ironically informs us, but it’s a tease. This prologue, mixing scenes from phases of Molly’s girlhood, characterizes her as having tenacity, determination, and not a little rage at her dad. Then the present-day action starts, as usual at a crisis. Molly is wakened from sleep by the FBI arresting her for illegal gambling. What has happened in the meantime? Even after the scene of her arrest, the film’s narration wedges in a VHS interview with young Molly in which she’s asked about her goals.

The revelation of the formative years, saved for late in Moneyball, is put up front in Molly’s Game. But now there’s a mystery: How does a promising athlete become a gambling queen?

The question is answered through another series of time shifts, and these occupy the bulk of the film. After Molly’s arrest, the narration fills in her arrival in Los Angeles and her job working for a sleazy entrepreneur who arranges poker games for rich men. Her rise in the world of underground gambling is intercut with present-time scenes of her consulting an attorney to take her case–a risky proposition, since her customers include Russian mafia. And the alternation of her legal problems and her gambling career continue to be interrupted by flashbacks to her as a little girl, as a teenager, and as witness to her father’s infidelities.

Sorkin has layered his plot within several time zones: present, immediate past, and distant past, with the earliest one including scenes scrambled out of chronological order. Again, the purpose is to reveal character motivation. The flashbacks suggest sources of Molly’s decision to triumph over weak men–perhaps, it’s suggested, as revenge for her father’s mistreatment of her and her mother. The time jumps also reveal her as a fierce competitor unwilling to give in. Athletics, it turns out, has a lot to do with poker.

The network as character prism

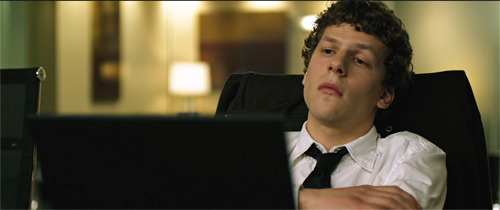

The Social Network (2010).

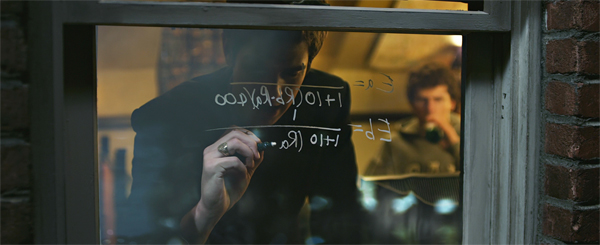

If there were a simple progress in Sorkin’s exploration of the menu of options, you’d expect that The Social Network would come later than it does. Yet before Molly’s Game yielded three principal time layers (the legal case, the career rise, the girlhood), Sorkin’s screenplay tracing the rise of Facebook had already fielded something more complicated than that.

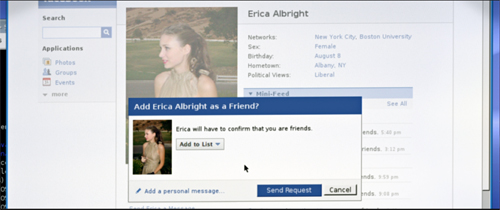

Still trying variants, Sorkin this time puts the motivating moment, the incident that drives the character, at the front of the film. In 2003, Mark Zuckerberg is on a date with Erica Albright. His arrogance provokes her to break up with him. In a burst of pique, he turns a blog into a page that denounces her and asks readers to rate local women. With the reluctant help of his friend Eduardo Savarin, the site crashes the Harvard server and Mark faces disciplinary action.

At this point the film splits into more time-tracks, again transmitted through legal proceedings. The Harvard disciplinary hearing is filtered through a deposition responding to Eduardo’s lawsuit against Mark, long after their partnership has collapsed. Sorkin could have picked this testimony as his point of attack for opening the film, then flashed back to the origins of the suit. Instead, like Molly’s Game, The Social Network starts its plot in the past, skips ahead to the future, and then fills in more of the past.

A second lawsuit is in progress, this time from the Winklevoss twins, and a second string of deposition scenes. Apparently more or less simultaneous with the Eduardo sessions, these also anchor us in an approximate present and cue up incidents in the past. For instance, in a past scene, after an ally of the twins tells of Mark’s successful webpage, the narration cuts to the opening of the Winklevoss case’s depositions, and then back to the brothers recruiting Mark to work on their project.

The dual-track depositions in the present allow Sorkin not only to segue into illustrative scenes in the past, but also to set up crosstalk between the two lawsuits. Immediately after Mark dodges questions from the Winklevii, we see him dodge questions in Eduardo’s session.

By the 2000s, audiences trained in the time-shifting of the 1990s could follow these quick alternations. It’s also up to the director to keep us oriented through differences in costume, angle, lighting, color design, and other elements.

If you take the opening portion as what sets the narrative Now, you could call the deposition scenes flashforwards. Alternatively, you might consider those scenes as Now, although the opening orientation to them has been deleted. Either way, Sorkin has provided a flexible, dynamic structure that allows us to study Mark’s behavior and others’ responses to it.

One of the dreams of storytellers who embraced multiple-viewpoint plots was the idea of letting us see different, even contradictory facets of a character. The prospect was broached by Henry James (in his novel The Awkward Age) and Joseph Conrad (in Lord Jim, Chance, and other books). On the stage, Sophie Treadwell had experimented with it in The Eye of the Beholder (1919). Herman Mankiewicz and Orson Welles played with the possibility of such a “prismatic” narration in Citizen Kane, perhaps as a result of Mankiewicz’s unproduced play about John Dillinger.

By using the trial schema a storyteller can present a character’s public self-presentation, the impression management that tries to win adherence. But the fact that different people testify about a situation also offers prismatic possibilities. Here, the chief contrast is between Mark’s snotty recalcitrance at the counsel table and his swagger in the past.

During the film’s opening, when Mark confides in Erica and Eduardo, we’re about as close to penetrating his mind as we’ll get in the film. Later the film’s narration offers less a study in how his mind works than a portrait of how he handles people–his social survival strategies. The range runs from sheer bluster, as when he tries to overwhelm Erica, through awkward acceptance of class ambition when he meets the Winkleviii, to evasion, threats, and bumbling efforts at friendship. At the end, he goes flat and legalistic, telling Eduardo: “You signed the papers.” The film’s denouement arrives when Eduardo’s lawsuit is launched. “Lawyer up, asshole.”

The opening sections began in the past, but the ending leaves us hanging in the present. At a pause in Eduardo’s suit, the film concludes on the image of blank-faced Mark staring at his monitor. Isolated by his betrayal of the one person close enough to have been a friend, he’s checking Erica’s Facebook page.

This conclusion lets us imagine that sexual and romantic frustration, exposed in the opening, have reinforced Mark’s low-affect aggressiveness. It’s also a suggestion that his slightly vampirish predation suits him for the age of the social network. But we’ll never be sure, because his disdainful indifference is his armor against everyone he encounters.

As with Molly’s Game, this cluster of parallel timelines is intelligible and forceful as a revision of a schema (present/ past/ present) that we know well. And careful cutting, sound work, and performance have kept us on track throughout.

End to end control

Steve Jobs (2015).

In films that don’t rely on chases, fights, explosions, time travel, fantasy, or extraterrestrials, what can hold your interest? For one thing, snappy talk. The old theatre adage claims that dialogue needs to do one of three things: advance the action, delineate the characters, or add humor. Sorkin’s dialogue does all of them at once.

Steve Jobs is braced by his assistant Joanna while he frets over a press story.

“’The only thing Apple’s providing now is leadership in colors.’”

“Don’t worry about it.”

“What does Bill Gates have against me?”

“I don’t know, you’re both out of your minds. Listen to me–”

“He dropped out of a better school than I dropped out of . . . but he is a tool bag and I’ll tell you why.”

“Make everything all right with Lisa.”

“You know–Joanna–boundaries.”

“You’ve come to my apartment at 1 AM and cleaned it, so tell me where the boundary is.”

“There, let’s say it’s there.”

“If I give you some real projections, will you promise not to repeat them from the stage?”

“What do you mean real projections? What have you been giving me?”

“Conservative projections.”

“Marketing’s been lying to me?”

“We’ve been managing expectations so that you don’t not.”

“What are the real projections?”

“We’re going to sell a million units in the first ninety days. Twenty thousand a month after that.”

Each reply shows that a strong line is like an arrow–feathered at the top, barbed at the tip. If your conflict is psychological, then the last part of the line should land with a punch. “We’ve been managing expectations so you don’t not.”

But the lines don’t exist in isolation. Every stretch of the film is a vivid lesson in whipping together bits of earlier conflicts, jumping from one to another as Jobs parries and ducks and changes the subject, all the while tension rises. One issue is picked up (Steve’s reaction to press coverage), interrupted by others (his rivalry with Gates, his friction with his daughter), followed up by a long-running relation with Joanna (“boundaries”), then a big piece of information: one goal, a sales target set in the first segment, has been achieved. But the others are left dangling, to be revisited, and we are looking forward to that.

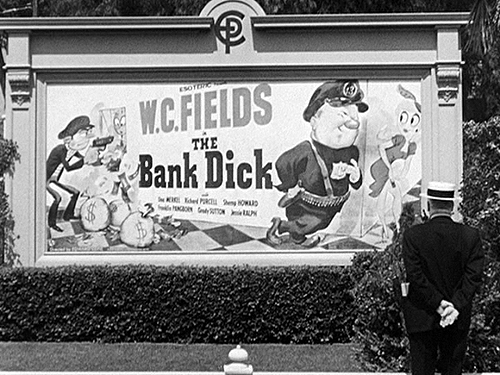

This sort of repartee brings back the era of snappy chatter. The exchanges recall the films set in rehearsal halls (Footlight Parade), news offices (His Girl Friday), movie studios (Boy Meets Girl), gangster cafes (All Through the Night), and even a research institute (Ball of Fire). A few films of recent years, such as The Paper, successfully recapture the exhilaration of such fast, pungent dialogue. Sorkin delivers it consistently.

Steve Jobs is one of Sorkin’s most structurally ambitious projects. Here he tries out another menu item, that of block construction. In this layout, we get two or more marked-off chunks or chapters, sometimes without the same characters. Block construction came into fashion with Mystery Train (1989), Slacker (1990), and other indie works, and it remains a basic resource for Tarantino and Wes Anderson.

As ever, Sorkin rewrites the block premise as a drama convention, the division into spatially and temporally confined acts. The plot of Steve Jobs is organized around three public product launches: in 1984 (the Macintosh), 1988 (the NeXT Black Cube), and 1998 (the iMac). Each event teems with crises large and small, public and private. They’re all parallel, in that we see the few minutes of preparation leading up to the curtain-raising. Like a party or restaurant scene in a play, a product launch offers a confined space in which characters and story lines can mingle. The pressure of a product demo allows Sorkin to create deadlines and motivate many walk-and-talk passages through backstage corridors.

Just as theatrical is the flow of people into and out of Steve’s presence. From act to act the same associates are ushered into Steve’s presence: his former romantic partner Chrisann, his business partner Steve Wozniak, John Sculley, engineer Andy Hertzfeld, a journalist, and Lisa, the daughter that Steve is reluctant to acknowledge. The French phrase liaison des scènes, “scene linkage,” captures the way that within a single setting characters’ entrances and exits break the act into distinct pieces.

In addition, Sorkin doesn’t confine his time frame to the duration of the demos. As in other films, flashbacks interrupt the present. The 1984 segment uses only one flashback, a visit to garage-hacking days that sets up the dispute about open and close architecture. The flashbacks thicken in the second segment, which reveals the conflict that led Steve to break off with Sculley. That quarrel in the past is tightly crosscut with their confrontation in the present, and as the tension builds one man in the present is replying to an objection in the past. This rapid pacing is one way a “theatrical” premise can hold an audience accustomed to action movies.

Like Fincher’s intercut depositions in The Social Network, Danny Boyle’s handling keeps us oriented through staging, costume, color, lighting, and shot/ reverse shot eyelines.

The block most saturated with flashbacks is the third, the one launching the computer that brought Apple to marketplace triumph. This chapter incorporates glimpses of scenes shown in the first two segments, along with revelations of Steve’s first approach to Sculley. This last recollection is prompted by his admission that he long ago found the biological father who gave him up for adoption. (Many of Sorkin’s protagonists have Daddy Issues.) Again, a big revelation about character motivation is saved for a flashback late in the film.

In addition, other crises come to a head. Steve appears to break definitively with Wozniak, and he reconciles with Lisa, whom he hasn’t, after all these years, fully taken into his life. As he achieves his goals–a successful computer at last, a settling with Wozniak and Andy, and a tentative accceptance of Lisa–he displays more chastened and cautious behavior. He has admitted his fallibility (he was wrong about the Time cover), he has realized what he lost in challenging and trashing Sculley, and he’s ready to move to the next challenge (“music in your pocket”). True, he treats Woz brutally, but Woz gets the final word: “It’s not binary. You can be gifted and decent at the same time.” Steve doesn’t change completely; he just gets a bit more human.

Interestingly, these cadences fit the four-part structure that Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood has revealed governing many classical plots: Setup, Complicating Action, Development, and Climax, followed by an epilogue or tag. Sorkin has “cinematized” his three “acts” by letting the final one harbor Development, Climax, and an epilogue.

Kristin also points out that classical film story telling relies on motifs that weave their way through the film. Not only music but lines of dialogue and images recur to point up repeated actions, indicate changes in character, or add humor. (A running gag is a comic motif.) Yet movies didn’t invent this tactic. Novels, poems, and plays rely on recurring motifs. Macbeth circulates imagery of blood and ill-fitting garments, while The Importance of Being Earnest wrings a lot out of the mysterious word “Bunbury.”

Steve Jobs is packed with motifs, far more than most movies I can think of. Some bounce around one segment and into another, and several come back at intervals in all three. All the characters relitigate old complaints, and Steve masterfully deflects a conversation by returning to remarks he’s made before. Here’s a partial list of items that are recycled again and again.

Starting exactly on time, the controversial SuperBowl ad, the need to turn off the Exit signs, a bottle of ’55 Margot, the Time cover, the purported treachery of Dan Kottke, “a million in the first 90 days,” “I don’t have a daughter,” 28%, Woz’s request to acknowledge the Apple II, “playing the orchestra,” closed versus open systems, the name Lisa, “end to end control,” 2001, “a dent in the universe,” slots, Pepsi, the psychology of adopted kids, “You get a pass,” the threat of a press release, and “which Andy?”

For Sorkin, even “Fuck you” becomes a motif rather than a space-filler.

A significant cluster involves the arts, particularly music and painting. In their quarrel the two Steves compare themselves to the Beatles, and Bob Dylan’s image and songs float through the movie. This association with the arts helps offset the unpleasant side of Jobs’ temperament, his crisp, frosty bullying of others and his relentless imposition of his “reality distortion field.”

Another motif softens him a bit: his desire to bring computing to kids. The prologue, in which Arthur C. Clarke is interviewed about the future of computing, sets up several motifs–the idea of separating oneself from others (Steve in a nutshell), the importance of home (associated with Chrisann’s demands), and particularly childhood. The reporter interviewing Clarke has brought his boy along, and they discuss how a new generation will quickly grasp the power of personal computing.

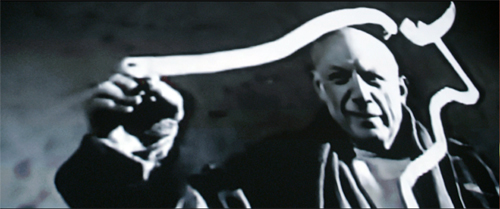

That motif is dramatized when, at first indifferent to five-year-old Lisa, Steve uses her as a demo to show Chrisann what the Mac can do. But his interest rises when Lisa intuitively understands that she can draw with it. “Lisa made a painting on the Mac,” he says thoughtfully. He seems to realize that she could be his brainy daughter, and he resolves to put her in a good school. Her drawing looks forward to Picasso’s swooping dab at a bull in the climactic montage of the 1998 launch.

The ping-ponging motifs are mostly in the dialogue, though. They push the action forward, recall earlier moments, and characterize the combatants while also yielding some laughs. Above all, the motifs chart Jobs’ character arc. We know that he’s more committed to Lisa at the end when he breaks his routine and says he’s willing to start the performance late. Soon he will reveal that he has saved her painting to give to her.

In The Way Hollywood Tells It I call Jerry Maguire a “hyperclassical” movie–more classical than it needs to be, flaunting a virtuosity of construction and motivic echo. I vote for Steve Jobs as another instance. Sorkin has used cinema to multiply motifs to a higher power.

Exporting ideas across state lines

The Trial of the Chicago 7.

One innovation of turn-the-century-theatre was the so-called “drama of ideas” or “problem play.” Ibsen, John Galsworthy, and Bernard Shaw sought to break away from standard intrigues of mystery and romance in order to dramatize women’s rights, labor struggles, and other social issues. Sorkin, with his liberal political bent, has brought that legacy to his film work. The subjects and themes he tackles have become as distinctive a marker of his work as any strategies of form and style.To be more precise, his formal and stylistic strategies work upon the ideas he wants to put forth.

How much private life is a US President entitled to? What is the duty of a politician who wants to enact social change? For a tech entrepreneur, where does idealism end and domination begin? Why should a woman not be able to compete on equal terms with men? Does social change come best through reform (reason, the ballot box) or revolution (change of consciousness)? Something like this last occupies him in The Trial of the Chicago 7.

The problem at the center of the film is: How to protest, and eventually stop, US involvement in the Vietnam war? The film’s prologue and epilogue announce the sweep of the issue. It begins with President Johnson ramping up troop commitments and establishing the draft lottery, all during a wave of assassinations. The film ends with Tom Hayden reading out the names of troops who have died while the trial was dragging on. Early on, Rennie Davis establishes the list because it’s “who this is about.”

The defendants in the trial are only loosely associated. Bobby Seale doesn’t know the others and was in Chicago just four hours; he’s also denied counsel. Sorkin carves out two major factions. Tom Hayden and Rennie Davis, as student activists out of SDS, are presented as preppy intellectuals, committed to antiwar action within the frame of protest and legal debate. Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, associated with the Yippies, are countercultural provocateurs. They anticipate a spectacle of innocence attacked by those in power. They will show the Chicago Democratic convention to be staged, as Walter Cronkite says at the end of the opening montage, in “a police state.”

Although Tom’s and Abbie’s factions communicate a little before the events, it’s the pressure of circumstances in Grant Park that pushes them into dispute. Alongside them Sorkin develops subplots that suggest other political alignments. David Dellenger’s commitment to nonviolence is tested by the flagrant repression of Bobby Seale. Richard Schultz goes along with orders to prosecute, knowing that the case is trumped up. Jerry Rubin falls briefly in love with an undercover policewoman. Fred Hampton tries to help Seale, only to be killed. Attorney William Kunstler discovers that he has a surprise witness to call. Editor Richard Baumgarten notes that in cutting all these lines of action together: “I feel like one of the great successes of how this film unfolds is that each of the characters does have a moment, or multiple moments.”

Tom and Abbie emerge as the “first among equals” because they most sharply articulate alternative accounts of what they’re facing. They aren’t dual protagonists, like a romantic couple tackling common problems. They’re at odds throughout. On the first day when Tom tries to get agreement on goals, Abbie challenges him.

Early court scenes show Tom annoyed by Abbie’s antics, but neither is really an antagonist for the other. Tom can half-humorously admit that he got a haircut to impress the judge, and clearly Abbie admires Tom. The antagonists are the government prosecutors and Judge Hoffman. Tom and Abbie function as what Kristin calls parallel protagonists. Like Mozart and Salieri in Amadeus, or Captain Ramius and Jack Ryan in The Hunt for Red October, they are at once opposed to one another and fascinated by each other. They both compete and cooperate.

What does each one want? This will become part of the drama’s problem, because the two men will be charged with coming to Chicago to stir up violence. Sorkin shrewdly postpones the question in the opening montage that brings some main players together through crosscutting. Incomplete dialogue hooks make their goals somewhat mysterious.

Tom: Young people will go to Chicago to show our solidarity, to show our disgust, but most importantly–

Abbie: –to get laid by someone you just met. . . .We’re going peacefully, but if we’re met there with violence, you better believe we’re gonna meet that violence with–

Dellenger: –non-violence. Always non-violence and that’s without exception. . . . (asking his son what to do in the face of police:)

Dellenger’s son: Very calmly and very politely–

Bobby Seale: –Fuck the motherfuckers up!

Seale’s capper would seem to negate the nonviolence of Dellenger’s position, but at the end of the montage Bobby refuses the pistol his colleague Sandra offers him. “If I knew how to use that, I wouldn’t need to make speeches.”

Unlike Dellenger, he’ll hit back if attacked first. So now only the positions of Tom and Abbie remain undefined.

Eventually, Tom exposes his rationale. If they can prove they were peaceful demonstrators within their rights, it will help “to end the war and not fuck around.” That demands treating the trial seriously. “We as a generation are serious people.” And he doesn’t want to raise police culpability. “We’re protesting the war, not the cops.”

From the start Abbie insists that the trial isn’t a matter of law but of contingency. “This is a political trial.” They were chosen to be examples, and the two lesser defendants are “give-backs,” people the jury can let off with a clear conscience. Abbie and Jerry came to Chicago knowing that police violence was very likely. (Cronkite said so too.) The best way to prove state oppression is to lay it bare, preferably with gonzo humor. After all, the whole world is watching.

The film’s structure supports Abbie’s analysis. Sorkin’s narration, using a moving-spotlight approach, has from the start tipped us that Attorney General John Mitchell has ordered Schultz to prosecute the 7 on flimsy grounds. Mitchell, a spiteful conservative, wants to crush antiwar protest, but he’s also petty. He’s miffed that Johnson’s AG Ramsey Clark insulted him on the way out of office. Mitchell has assembled a mixed bag of antiwar activists to charge with conspiracy. (In an ironic twist, they conspire most successfully after they have been thrown together for trial.)

So the problem play becomes a progress toward understanding political power. Tom Hayden (and to a lesser degree Kunstler) come to grasp the reality of an engineered police provocation and a show trial. Abbie’s privileged insight is further stressed by the fact that he’s the only character given a narrator role. Sorkin interrupts the trial with shots of Abbie at a mike in a club, telling the story of the fights during the riots, correcting the false testimony of the cops. In stage tradition, Abbie is the raisonneur, the explainer.

The conflict between Tom and Abbie gets specified gradually, sharpened in strategy sessions where Tom berates the Yippie contingent for clowning. If progressive politics is branded as childishness, “We’ll lose elections.” Abbie calmly replies that “We’re going to jail for who we are.” The debates are about tactics as well. Tom wants the demonstration to keep away from the convention hall, while Abbie insists that they go downtown. As it turns out, the police squeeze them out of the park and force them into a trap that yields the spectacle that Abbie and Jerry anticipated.

Through crosscutting Sorkin again creates several layers of time: the runup to the convention, the protests themselves, the trial, and a more unspecified moment when Abbie is at the microphone narrating. More linear than the time mosaics of Molly’s Game and Steve Jobs, the Chicago 7 array might seem a step back toward the classic trial schema. Basically, the court proceedings frame the flashbacks to the purported crimes.

The relative linearity is needed, however, to allow us to chart the progress of the parallel protagonists. In a neat balancing act, Sorkin dramatizes character change with Tom Hayden and character revelation with Abbie Hoffman.

Hayden’s character arc traces his realization that the trial is rigged. He has brought table manners to a revolution. He presents a wholesome appearance, and when pressed by Bobby he half-admits he’s rebelling against his upbringing. (Daddy Issues again.) Even his “reflex” action of rising when His Honor enters, violating the pact among the 7, shows that the impulse to behave well is struggling against his sincere urge to end the war through citizen action.

Yet Tom has an outlaw side as well. He releases the air from the tire of a cop car to allow Rennie to escape surveillance. At the climax, seeing Rennie beaten, he calls for blood to flow through the city–not, he tries to explain, the blood of others, but the blood freely given by the protesters. Still, he joins forces with Abbie, Jerry, and Dellenger as they are lured onto the footbridge and into the cops’ trap. The cops, having choreographed the street assembly, push them through the tavern window.

Tom, our main viewpoint vessel in the film, also visits Ramsey Clark with his attorneys. It’s then that he realizes the trial is Mitchell’s political charade aiming to override Clark’s decision not to prosecute the demonstrators. So, after Clark has testified (and sees his testimony suppressed by Judge Hoffman), Tom can redeem himself.

Judge Hoffman has offered Tom clemency before he makes his final statement. The good boy who had asked, “Why antagonize the judge?” rises in polite defiance to read the names of the dead. He will take the same punishment meted out to the others. He now understands revolution as spectacle.

So there’s a little of Abbie in Tom. In the same final stretches of the film, we learn that there’s a little of Tom in Abbie. Tom had planned to testify, but he can’t justify what he said on tape. So Abbie takes the stand. His slapstick persona drops. Behind the Jewish Afro and the wisecracks is revealed an intellectual who can quote the New Testament and gently praise Tom as a patriot. Schultz questions him: Was he hoping for a confrontation with the police? “I’ve never been on trial for my thoughts before.”

As in the opening montage, Sorkin cuts away before Abbie answers, and his pause and grave demeanor let us consider that for all his bravado, he has regrets about the crisis he saw coming.

Like any problem play, The Trial of the Chicago 7 can be criticized for stacking the deck, or oversimplifying, or recasting the problem in ways that favor certain interests (e.g., white college-educated men). But that critique is the risk artists run all the time, even in the most anodyne “nonpolitical” work. If critics study how films achieve their effects, viewers can be more aware of how the schemas we know are shaped by the movies we see and get a clearer sense of means and ends, purposes and fulfillment.

At the same time, artisanal skill in a robust tradition is intrinsically worth analysis. That analysis can reveal new possibilities in what cinema can do. In The Trial of the Chicago 7 Sorkin creates a dramaturgy that embodies ideas in characters’ conflicts, changes, and hidden facets. Once more a theatrical premise has been turned into classically constructed cinema. Sorkin’s work offers one way that this tradition can stay fresh–not through shocking breakthroughs but by highly skilled reworking of schemas accessible to a broad audience. You know, the way theatre used to be.

Thanks to conversations with Kristin and Jeff Smith, who helped me clarify my ideas.

For more background on this sort of narrative analysis, there’s a synoptic blog entry here. This earlier one might also be of use. Rory Kelly offers some nuanced analysis of the Hollywood character arc.

Cinema’s debts to theatre are considered in this entry, and some others in the category Film and other media. On the power of artisanal care, there’s this on Buster Scruggs.

Another entry discusses how actors use their faces in The Social Network.

P. S. 5 March 2021: I’ve just found some interesting remarks from Sorkin about what he calls “the puppy crate”–the need to focus a drama in a confined time and space. The Trial of the Chicago 7 is an obvious example, but so too is Steve Jobs. “I need four walls really badly.”

The Trial of the Chicago 7 (2020).

Balancing three protagonists in THE FAVOURITE

Kristin here:

Given the current year-round feverish speculation about the Oscars, it was perhaps inevitable that the campaign for performer-awards nominees for the three leading ladies of The Favourite was what drew attention to their relative prominence in the film. As Gold Derby (the website subtitled “Predict Hollywood Races”) said during the lead-up to the announcement of the nominees, “The film inspired a lot of debate in the early days of the Oscar derby as to what categories the film would campaign its three actresses [for].” Ultimately it was decided to place Olivia Colman in Best Actress and Emma Stone and Rachel Weisz in Best Supporting Actress. (For those who are interested, this story gives a detailed run-down of those occasions on which two or even three performers from the same film were nominated opposite each other in the same category.)

Esquire was one among many media outlets stating the same opinion: “Yes, Emma Stone and Rachel Weisz are both leading players in The Favourite, and yes, it’s probably category fraud that they were submitted in the supporting category to bolster Olivia Colman’s chances to win Best Actress. It is what is, and we must live with the fact that these two will get the nomination.” Indeed, that was what happened.

Stone and Weisz showed good grace in reacting to the studio’s decision–wise even without the benefit of hindsight–to campaign for Colman as the sole best-actress nominee. They did not, however, suggest that she was the sole protagonist of the film. In an interview with The Hollywood Reporter, Weisz remarked, “I think Fox Searchlight was quite brave to make a film with three really complicated female protagonists. It’s doesn’t happen every day, sadly.” Every year The Hollywood Reporter interviews prominent but anonymous Academy members about their opinions and preferences in the main categories. This year an unknown director complained of the best-actress race, “I don’t understand what [Olivia Colman’s] doing in this category, or what the other two [Emma Stone and Rachel Weisz] are doing in supporting–all three should be the same.” The notion that the three roles were roughly equal in importance was expressed widely during awards season. Google “The Favourite” and “three protagonists,” and many hits will show up in the trade and popular-press coverage.

This notion of three protagonists intrigued me. I believe that the structures of many classical narrative films depend to a considerable extent on how many protagonists they have, what those protagonists’ goals are, and what sorts of obstacles they encounter along the way–often obstacles that lead or force them to change their goals. I based my book, Storytelling in the New Hollywood (1999), partly on that idea. For close analysis I chose four exemplary films with single protagonists (Tootsie, Back to the Future,, The Silence of the Lambs, and Groundhog Day), three with parallel protagonists (Desperately Seeking Susan, Amadeus, and The Hunt for Red October), and three with multiple protagonists (Parenthood, Alien, and Hannah and Her Sisters).

Single protagonists are the commonest, and their obstacles are typically generated by single antagonists. Multiple protagonists are somewhat less so. They tend to break into at least two types. There are shooting-gallery plots like Alien, in which the protagonist is the one who, predictably or not, survives the gradual killing-off of the other main characters. Then there’s the network-of-relations plot, like Parenthood and Hannah, in which separate plotlines are acted out, with the protagonist of each related by blood or friendship to the protagonists of the others. More difficult to pull off is the multiple-protagonist plot where the characters are linked by an abstract idea and have minimal or tenuous relationships to each other–Love Actually being a masterfully woven example. (Would that it had existed when I wrote my book!)

The parallel-protagonist plot is relatively rare. I’m not talking about a film with two main characters who are closely linked and sharing the same goal. The buddy-film, most obviously two partner cops as in the Lethal Weapon films, is a common embodiment of this goal, as is the romance where the couple are in love from early on but face obstacles posed by others, as in You Only Live Once.

Parallel protagonists are not initially linked but pursue separate goals that usually bring them together. This might involve a romance conducted from afar, as in Sleepless in Seattle. One character may know the other and seek to be more like him or her, as in Desperately Seeking Susan and The Hunt for Red October. In those two cases, the main characters end by succeeding as they come together and become friends. (Hair would be another example I could have used.) In Amadeus, on the other hand, Salieri fails in his desperate attempt to replace Mozart in public favor and to essentially become him by stealing his Requiem and passing it off as his own.

The triple-protagonist plot

I never considered the category of triple protagonists, simply assuming they would belong within the multiple-protagonist films. Perhaps they do, but The Favourite raises the possibility that such films have a distinctive dynamic, somewhat akin to the parallel-protagonist plot but more complex, or at least more complicated.

Balancing two protagonists who have more-or-less equal stature in the plot is probably not much more difficult than the other types of classical plots. I think that’s largely because these two main characters can come together by the end and become the romantic couple or the buddies who could easily have been the main figures in a dual-protagonist film. Three protagonists, however, are very difficult to balance without one or two of them becoming mere supporting players by the end.

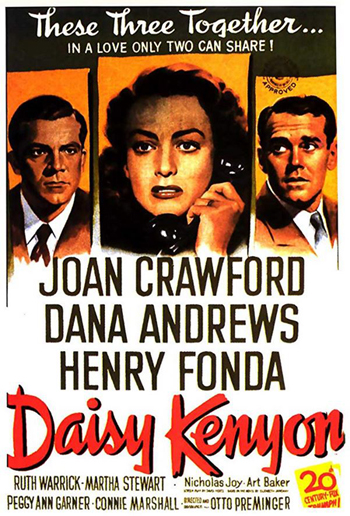

Across the history of classical filmmaking, there are probably a fair number of examples of such a balance being achieved. It’s not easy to think of more than a few, though. The first one that came to my mind is Otto Preminger’s underappreciated Daisy Kenyon (1947). In it Daisy is the mistress of a prosperous married lawyer, Dan, who refuses to divorce his wife and marry her. She meets a genial but traumatized war veteran, Peter, and marries him, but when her initial lover finally files for divorce, she is torn between the two. More about Daisy Kenyon later, the point here being that a triple-protagonist plot is not out-of-bounds for Hollywood and that two people struggling to win a third’s favors is an obvious situation to use in such a film.

The first half of The Favourite displays the long-established relationships between Queen Anne and Sarah. Sarah is stern and commanding with Anne, even cruel at times, and she runs political affairs in the Queen’s place. It is also clear, however, that the two love each other and that Anne, with her various physical and mental frailties, heavily depends on her friend. This half also traces the rise of unfairly impoverished Abigail, Sarah’s cousin. She ingratiates herself with Anne by helping nurse her gout and providing sympathy and deference; she even induces the semi-invalid Anne to dance.

Up to this point we are cued to sympathize with Abigail. She has been the innocent victim of misfortune and is treated cruelly once she arrives at court and Sarah hires her as a scullery maid. The midway turning point, as I take it, happens in the scene where Abigail shoots a pigeon and the blood spurts onto Sarah’s face. Immediately after this a servant arrives to say that the Queen is calling for Abigail rather than Sarah. Abigail is implied to have tipped the balance toward her being accepted as Anne’s favorite.

After this point, we suddenly start to see Abigail’s conniving side, and the pendulum swings as we grasp that Sarah has been displaced in the Queen’s affections through Abigail’s lies about her. In this second half, we are led to recall that Sarah, dominating though she is with Anne, truly loves her and is far more qualified to help run the state than frivolous Abigail is. By the end, all three have managed to make each other and themselves miserable, though Sarah still has her husband and manages to take exile abroad in her stride. None of them emerges as the most important character.

One might argue that Abigail functions as a conventional antagonist. After all, she drugs Sarah’s tea, nearly causing her death–and showing no compunction about it. Yet she, too, is pitiable. Her father gambled her away into marriage with a stranger, and early in the film she is bullied by the other servants. Sarah has her unlikable side and at one point attempts to blackmail Anne by threatening to make public the Queen’s love letters to her–an act that finally drives Anne to reject her. Before that rejection, however, Sarah burn the letters instead, confirming her inability to betray queen and country.

In a review on tello Films Karen Frost writes,“While Stone may receive a modicum more screen time than the other two, this movie really has three protagonists, all of whom are compelling in their own way.” I suspect a lot of spectators, including me, share this impression that Abigail is onscreen or heard from offscreen marginally more than Anne or Sarah. That said, it’s very difficult to measure the presence of each character, given how short the scenes are and how often the women come and go from the rooms where the main action is occurring. And does a scene like the one at the top of this section, where Anne and Sarah converse while Abigail stands mutely in the distance, give equal weight to all three? Perhaps, in that we are here conscious of the latter’s simmering resentment.

In a comparable scene, Abigail is pushing the Queen in a wheelchair. Anne becomes upset and tries to stagger back to her room. We follow her and concentrate on her struggle and emotions for some time before Abigail appears again with the chair. Should we consider this one scene between the two, or actually three scenes, with the two together, then Anne alone, and then the two together again? Even within scenes where two or three of the women are present, weighing their relative prominence in the scene presents difficulties.

The casting is crucial in such a film, since the relative prominence of the actors tends to affect our judgment of their characters’ importance. Rachel Weisz and Emma Stone were both Oscar-winning stars before The Favourite‘s release. Olivia Colman was not well-known in the US, but she had had a long and prominent career on television and occasional films in the UK, The Favourite‘s country of origin. Certainly as Anne she gains the audience’s sympathy early on and becomes plausible as a protagonist alongside the other two.

Scenes and twists

I decided that rather than attempt to clock screen time, I would count how many scenes each character had alone, how many involved two of them, and how many showed all three together. When I say “alone,” I mean only one of the three women is present, though often she is interacting with the main male characters, Lord Treasurer James Godolphin, Leader of the Opposition Robert Harley, and Baron Masham. Given the many very short scenes, the intercutting, the presence of the characters in the backgrounds when the others are emphasized, and the brief intrusion of a character into a scene that overall emphasizes one or two of the other women, my breakdown into segments can’t be precise.

I’ve compared the numbers of scenes devoted to the various combinations of characters in the first and second halves of the film, given the reversed situations of Sarah and Abigail in those large-scale sections.

First, the characters alone:

Anne has only 1 solo scene in the first half/3 in the second. (Total 4)

Sarah is alone 2 times in the first half/8 in the second. (Total 10)

Abigail is alone 7 times in the first half/9 in the second (Total 16)

Abigail’s larger number of scenes apart from the other two women occur largely because she is duplicitous and her situation changes drastically. Anne and Sarah behave straightforwardly, the former because she is too addled to be capable of deception and the latter because she is fundamentally honest, if sometimes brutally so.

Abigail’s duplicity must be revealed gradually. This is done to a considerable extent through two important relationships that help reveal that she is not the sweet young thing that we may have initially taken her to be. In the first half, Harley tries to bully her into acting as a spy in Anne’s bedchamber, passing on to him the political tactics and decisions of the Queen and Sarah. At first it is not clear that Abigail will comply. She also has aggressively flirtatious scenes with Masham. Initially she seems to be Harley’s victim and genuinely attracted to Masham, if in a rather eccentric fashion. Almost immediately after the midway turning point, however, Abigail passes secret information to Harley for the first time. Later, after Anne permits her to marry Masham, it is revealed that Abigail’s primary motive was to restore her lost social standing.

Scenes with Queen Anne with one or the other or both other women:

Anne with Sarah: 6 times in the first half/7 in the second (Total 13)

Anne with Abigail: 3 times in the first half/10 in the second (Total 13)

Anne with both: 6 times in the first half/5 in the second (Total 11)

Here the balance among the three protagonists becomes apparent. Whether intentionally or not, the scriptwriters gave Sarah and Abigail the same number of scenes alone with the queen. Abigail’s access to the Queen is naturally considerably greater in the second half of the film, as she gains her status as the favorite. Surprisingly, though, Sarah’s scenes with Anne are balanced between the two halves. I take this to reflect the Sarah’s determination not to be defeated and also the lingering friendship and genuine love that the two have shared since childhood. If we are to realize by the end that Anne has made a dreadful mistake by rejecting Sarah and sending her into exile, we must be reminded at intervals of how vital Sarah had been in helping Anne run the affairs of state.

The fact that Anne’s scenes with both other women are balanced between the two halves functions to allow us to continue comparing the behavior of both women toward the Queen. We slowly grasp Abigail’s perfidy and Sarah’s prickly steadfastness. The latter is made particularly poignant in Anne’s and Sarah’s final conversation, which takes place through the closed doorway of Anne’s room and ends with Anne rejecting her old friend, despite apologies and pleading.

Queen Anne is in a total of 41 scenes, Sarah in 44, and Abigail in 50, which does suggest that the latter has more screen time overall. The reason for this is probably not that she is more important, but that Sarah and Anne have an established, loving relationship at the beginning, which is easy to set up. Abigail must claw her way up from the scullery to the Queen’s bedroom, which takes more time to accomplish.

The screen time, however, is not the key factor. The film’s impact on the spectator depends to a considerable degree on our struggle to figure out which, if any, if these characters we might identify or sympathize with. There are such frequent shifts of tone and of what we know about each of them that our expectations are systematically undermined in the course of the plot.

In an interview on Deadline Hollywood, Tony McNamara, one of the scriptwriters, describes the effects of having three protagonists:

I thought it would be hard, but it was actually kind of liberating to have three, because it just gave you more options and places to go. Often, an action in a script has a reaction, but just one antagonist and protagonist. But because it’s three protagonists, there was always this cascading effect, and there were more twists. It was fun to have options, [though] there was work to do, making sure that the three were in balance, throughout.

Twists the film has in abundance. Our attitudes toward the characters change time and again. The scene in which Sarah starts letter after letter to Anne, trying to regain her favor, encapsulates all three women’s mercurial behavior. Her openings range from violent resentment (“I dreamt I stabbed you in the eye”) to fondness (“My dearest Mrs Morley”–her pet name for the Queen). The latter is the one she sends, but Abigail consigns it to the fire, finally making any reconciliation between her rival and the Queen impossible.

The ending, with its superimpositions of Anne’s rabbits over the faces of her and Abigail has been criticized as a failure to provide a satisfactory conclusion to the tale of the three protagonists. I’m not sure it is a failure of invention. Abigail’s insinuation of herself into the Queen’s favor began when she noticed the rabbits in the royal bedroom and elicited Anne’s tale of the loss of all seventeen babies she had had, with the rabbits acting as substitutes for them. Abigail had expressed an apparently deep sympathy, but in the final scene Anne sees Abigail capriciously and cruelly press her foot down on one of the rabbits. All illusions that her new favorite has loved her better than Sarah had vanish at this point, if they had not already. The two are portrayed as trapped in a relationship based on grief over unthinkable loss on the part of one and hypocritical manipulation by the other.

Preminger’s balancing act

Daisy Kenyon differs vastly from The Favourite, to be sure. Still, it’s a romantic triangle situation, and the woman who must decide between her two suitors is indecisive up until just before the ending. Dan and Peter are equally plausible as a final choice. Both have faults. Dan is content to carry on his adulterous affair with Daisy indefinitely, and Peter spies rather creepily on her after meeting her, secretly following her to a movie theater so that he can “accidentally” meet her when she comes out. Both clearly are in love with her.

Preminger also managed to cast three stars of more-or-less equal stature. Andrews had gone from supporting roles to the lead in Laura (1944) and was just coming off the success of The Best Years of Our Lives (1946). Fonda had had both leading and supporting roles since the mid-1930s and starred in such films as Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), The Lady Eve (1941), and My Darling Clementine (1946). There is no Ralph Bellamy, the obvious Other Man, here.

There’s another resemblance to The Favourite, in that the man Daisy ultimately chooses then says something that creates a final twist–indeed, it’s the last line of the film. He reveals that not all is as we assumed, and we may be left wondering if, like Queen Anne, Daisy may regret her choice.

Another obvious triple-protagonist film is Ernst Lubitsch’s Design for Living (1933), which once again presents a romantic triangle centering on a heroine who is understandably indecisive in choosing between Gary Cooper (George) and Fredric March (Tom). She moves in with both with an agreement that they will avoid sex. She succumbs to George’s charms when Tom is away and to Tom’s when George is away, and when jealousy between the two men breaks out, marries her rich but boring boss (Edward Everett Horton). The pre-Code ending sees Gilda back with Tom and George in an arrangement that seems no more likely to remain sexless than the first one had.

Again the casting makes the two male protagonists seem equal. March and Cooper were both rising stars at the time, with March fresh off an Oscar win for Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1932). Cooper had achieved prominence with The Virginian (1929) and followed up with Morocco (1930) and A Farewell to Arms (1932).

This is not to say that all three-protagonist films have this triangle plot with an indecisive woman as the pivot. No doubt there are all sorts of other ways to balance three lead roles. Nor is it to say that three-protagonist films are so common and distinctive as to make me go back and revise Storytelling in the New Hollywood. Still, it’s interesting to see this kind of variant played on more familiar plot structures and to study how filmmakers can go about maintaining the necessary delicate balance.

David has an analysis of Daisy Kenyon‘s narrative maneuvers in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling.

Daisy Kenyon (1947).

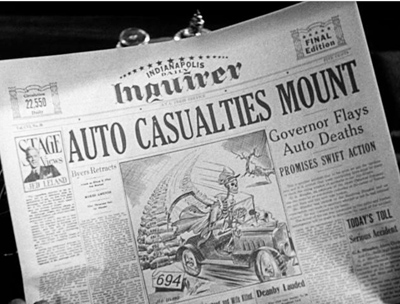

1932: MGM invents the future (Part 2)

Courtesy John McElwee and his gorgeous, informative site Greenbriar Picture Shows.

DB here:

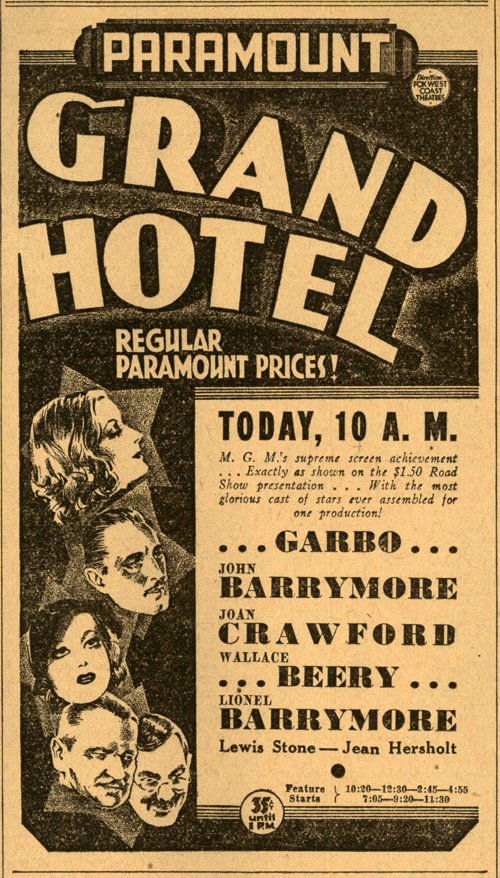

The inner monologue, as a report of a character’s immediate thoughts, seems to have been rare in 1930s films; it became more prominent in the 1940s. But the second big MGM narrative innovation of 1932 was almost instantly influential, redone and nearly done to death in the decades that followed. Even before the film was released, the idea of a “Grand Hotel plot” had gripped both the public and professional storytellers. And it never went away.

In the Strange Interlude entry, I mentioned that what’s usually of interest to us when we try to track the history of film forms is not the first time something is done but the moment when it becomes recognized as an active option. It stands forth as a strategy that can be copied, standardized, and revised. The Grand Hotel idea itself wasn’t utterly new, but the novel, play, and film of that title crystallized it as a distinct choice on the filmmaking menu.

The book: Only approximations

Vicki Baum, an emerging German novelist, launched Grand Hotel as a magazine serial. It was published in book form in 1929 as Menschen im Hotel and became a huge seller. The following year saw Baum’s international breakthrough. In January a stage version opened in Berlin. It migrated to Broadway in November and enjoyed huge success. Meanwhile, a British publisher brought out an English translation. In February of 1931, Doubleday published an American edition. That month Baum arrived in Hollywood to work on the screenplay for what she called her “star-studded wedding cake.”

The central story remains constant in all the media versions. Three men converge in Berlin’s Grand Hotel, each with his own aims. Baron von Gaigern is a penniless aristocrat who has taken to theft. The provincial bookeeper Kringelein has been diagnosed with a fatal disease, so he has vowed to enjoy the good life before he dies. He demands a costly room and plans to wine, dine, and gamble his savings away. The business mogul Preysing is there to meet with potential partners in a big business deal. Preysing, it turns out, is the owner of the company employing Kringelein.

The men’s plans pull two women into their orbit. There is the glamorous but fading dancer Grusinskaya. She meets the Baron when he slips into her room to steal her pearls; during that night of sexytime they fall in love. Then there is the stenographer Flaemmchen, who takes a liking to the Baron but who is dominated by Preysing. He has hired her to record his deal-making, and he soon invites her to be his mistress. Add in secondary characters like the porter Senf, who at the start is waiting for news of his wife’s delivery of their baby, and Dr. Otternschlag, a disfigured war veteran who drifts around the lobby mournfully observing life.

The men’s plans pull two women into their orbit. There is the glamorous but fading dancer Grusinskaya. She meets the Baron when he slips into her room to steal her pearls; during that night of sexytime they fall in love. Then there is the stenographer Flaemmchen, who takes a liking to the Baron but who is dominated by Preysing. He has hired her to record his deal-making, and he soon invites her to be his mistress. Add in secondary characters like the porter Senf, who at the start is waiting for news of his wife’s delivery of their baby, and Dr. Otternschlag, a disfigured war veteran who drifts around the lobby mournfully observing life.

The novel’s action consumes three days and nights, with an epilogue on the morning of the fourth day. Each major character undergoes a crisis triggered by meeting others in the hotel. Preysing catches the Baron in his apartment, bent on robbery. In beating the Baron to death, Preysing ruins his life; he is arrested and his family leaves him. Flaemmchen, about to go off with Preysing, attaches herself to Kringelein and vows to help him recover his health. Grusinskaya, who has left Berlin for her tour date in Prague, calls the Baron’s room in vain, unaware that she will never see him again.

The book offers several attitudes toward the interwoven destinies. There is that of the grim Dr. Otternschlag, who sees in the lobby’s revolving door a ceaseless cycle of mundane suffering. “Always the same. Nothing happens. . . . And so it goes on. In—out, in—out.”

The bellboy looks at the same door and sees endless variety: “Marvelous the life you see in a big hotel like this. . . . Always something going on. One man goes to prison, another gets killed. . . .Such is Life!”

The omniscient narration provides another attitude, seeing in the door an image of life’s ephemeral, fragmentary quality.

The revolving door twirls around and what passes between arrival and departure is nothing complete in itself. Perhaps there is no such thing as a completed destiny in the world, but only approximations, beginnings that come to no conclusion or conclusions that have no beginnings.

All three musings represent, we might say, alternative ways of reading the novel: as an eternal return, a varied pageant of human drama, or scattered glimpses of incomplete lives.

Play and film: Call waiting

National Theatre production, New York 1930.

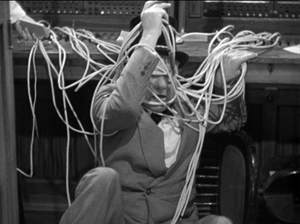

The novel spreads the action to the theatre, a casino, and an airplane flight, but the stage version confines itself wholly to the hotel. The play begins with a coup de théâtre for which Baum claimed the credit. Preysing, Kringelein, the Baron, Flaemmchen, and Grusinskaya’s maid Suzanne are introduced in a line of telephone booths, each making a quick phone call. The light in each booth flashes on and off as each one speaks. The pace builds until each speaker is “intercut” rapidly with another. Baum claimed that this pulsating sequence drove the opening-night audience to a frenzy of applause. Snazzy as it is, the prologue serves as crisp exposition, literally spotlighting nearly every major character, with Suzanne acting as a proxy for the dancer Grusinskaya. Then the revolving stage whisks us to a broad view of the lobby teeming with guests and staff.

The novel can proceed in a fragmentary way, shifting from one character to another, but the play contrives a more fluid rhythm of encounters. At the start, several characters assemble at the front desk, and after a “cutaway” to Grusinskaya’s room, we’re back in the lobby with Flaemmchen, the Baron, and Kringelein chatting while Preysing and his colleagues head off to their conference. Later all the major characters except Grusinskaya, who’s often marked as separate from the others, meet in the hotel bar and grill. At the conclusion, as characters depart, overlapping encounters carry Flaemmchen out the door with Kringelein, and Grusinskaya leaves for Prague wondering why the Baron has failed to meet her. The spatial concentration of the play squeezes the characters’ trajectories together more tightly than the novel does.

The film does much the same thing. When head of production Irving Thalberg bought the rights to Baum’s novel, he had to buy the stage rights as well, and so MGM funded the Broadway production. It garnered over a million dollars in its first year.

Claus Tieber points out that having seen the play, Thalberg insisted that the bits that pleased the Broadway audience had to stay in the film. No wonder that the film sticks close to the stage version. Although sequences are added, they seem in the spirit of the play’s swift pace. An American critic had described the book’s rapid changes of scene as like a film: “interlocking adventures, a little too easily linked perhaps, flit from screen to screen [shot to shot?].” Baum agreed:

I realized what had made my Grand Hotel, the novel and the play, a world success: it was probably the first of its kind to be written in a sort of moving picture technique. By now [1964] that’s the oldest of old hats, but in those days the kaleidoscopic effects, brief ever-changing scenes, flashes, staccato dialogue, were new, surprising, and exciting…on the stage. On the screen, I felt, this technique was the usual old stale shopworn thing.

In a crucial expansion of both book and stage show, the film emphasizes the telephone switchboard, marking the hotel as the crossing point of many destinies. After Preysing has beaten the Baron to death with a phone receiver, the switchboard is ominously stilled at the climax.

The prologue shows other protagonists making calls, but Grusinskaya, because of her isolation from the others, works the phone in the bulk of the film. Her final call for the Baron goes unanswered, heard only by his dog.

The play had enhanced the women’s roles, and the film goes farther by casting two top stars, Greta Garbo as Grusinskaya and Joan Crawford as Flaemmchen. With three strong male leads—Wallace Beery as Preysing, Lionel Barrymore as Kringelein, and John Barrymore as the Baron—the film became an ensemble drama that gave more or less equal weight to five characters. Accordingly it became known as the first “all-star picture.” On its tenth anniversary Variety proclaimed that it “disproved the contention that no picture could support a huge all-star cast.”

Even putting the cast aside, Grand Hotel crystallized a narrative option that had been emerging, more or less explicitly in the years before.

Networks and cross-sections

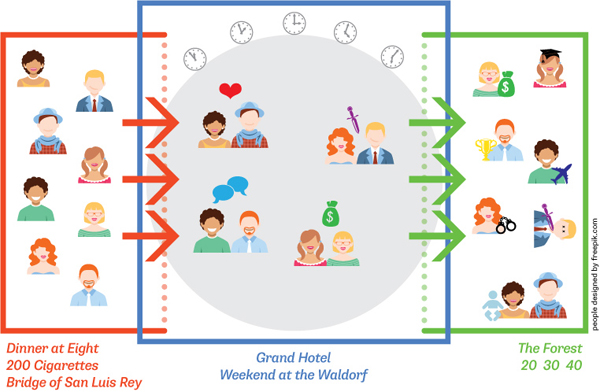

We can think of the Grand Hotel format as one variant of what I’ve called network narratives. Putting it generally, these are films that shift our attention across several somewhat linked characters and their projects.

Most films we encounter have a single protagonist, accompanied by helpers and facing some number of antagonists. Other plots have dual protagonists, perhaps cops who are buddies, or a man and a woman in a romantic relationship. A few films may have three protagonists, like Letter to Three Wives.

Another variation is the film with several protagonists, each given roughly equal weight. Usually the multiple protagonists share a goal, as in combat films, where they are united in a common mission. But when we have multiple protagonists pursuing different, largely unrelated goals, we have what I’m calling a network narrative.

What makes all these characters part of the same network? Any social relation. They might be relatives, friends, co-workers, classmates, neighbors, ex-lovers, or whatever. Also, mere proximity can connect characters; maybe they’re in the same hospital room or conference meeting or just in the same town.

As the film unfolds, we come to understand the array of characters and their connections. We follow one, then another, and we watch new relationships form. Sometimes hidden relationships are revealed to create a surprise. Some connections are distant, of the n-degrees-of-separation variety. The characters’ various purposes may run parallel, or they may intersect and clash—all more or less accidentally. Most plots of any sort are connected by causality, but network narratives are once tight (because of the pressure of the characters’ goals) and loose (because social ties can flow in many directions).

The advantage of the network approach is to yield a cross-section of life denied to more traditional linear narrative. Such plots can present, as Joseph Warren Beach puts it, a “comprehensiveness of view” that becomes “a composite picture of many distinct lives.” But the strategy raises problems too. The idea of a network narrative invites a dizzying expansion. X meets Y, who’s married to Z, the friend of A, who works with B, and pretty soon your story world is growing out of control. You need to constrain it somehow.

One way, as in Slacker, is just to sample one string of the network, moving from node to node. This generates a sort of “slice of life” plot, in the manner of Naturalist theatre. That snatches a few episodes from central characters’ lives without the customary setups and resolution. Bernard Shaw noted that “The moment the dramatist gives up accidents and catastrophes, and takes ‘slices of life’ as his material, he finds himself committed to plays that have no endings.” In film, we might think of one prototype of Neorealist cinema, The Bicycle Thieves. Baum’s framing narration of Grand Hotel, with its musing on stories without clear-cut beginnings or resolutions, tries for the same sense of what Zola called “a fragment of existence.”

Some of the literary models, such as The Lower Depths, accept a slice-of-life approach, without traditional climaxes and resolutions. Modernist writers pushed this possibility further, very open-textured networks. Dos Passos’ USA trilogy (1930-1936) is one example. Evelyn Scott’s The Wave (1929) presents seventy episodes from the Civil War, each concentrating on a different individual, although some characters reappear in sections devoted to others. A comparable strategy rules William March’s Company K (1933), with its 131 vignettes of World War I, with each soldier’s scene narrated in first person. Again, some characters reappear, but the network is largely a dispersed one.

Novels with well-defined protagonists occasionally strayed into a more lateral, open-textured approach. One example is the Wandering Rocks section of Ulysses, which fleetingly probes the minds and actions of about a hundred Dubliners moving through mid-afternoon. In Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway (1925), a sudden noise from a car stuck in traffic, followed by an airplane swooping above, causes various members of a crowd to think stray thoughts. Like Joyce, Woolf momentarily broadens the frame to register the reactions of characters unconnected with the protagonists, except by being present outside Buckingham Palace at the same moment. Only space and time create this network, and it’s ephemeral.

Bring us together

Given our appetite for linear narrative, some storytellers are bound to seek ways to tighten things up. Can we graft normal plot development—goals, conflicts, rising tension, climaxes, and resolutions—onto the network idea?

Yes. One way is to create the network through a circulating object, as in Tales of Manhattan, Au hasard Balthasar, American Gun, Twenty Bucks, or The Earrings of Madam de…. Sometimes the result will be episodic, but other times there will be a rising tension and a conclusion to at least some lines of action.

The most common way to constrain the network is to multiply the connections within the group. That is, don’t make the network loosely woven. So X meets Y, who’s married to Z, the friend of A; but A works with X, who is the cousin of B, who has been having an affair with Y, and so on. In other words, you create a “small world” defined by several connections among all the participants.

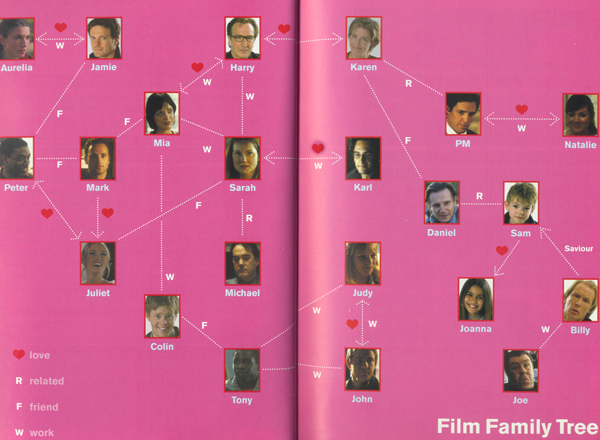

This small-word model is common in novels that create network narratives. Dickens, Balzac, and other writers have created complex degrees-of-separation plots. It’s likewise the pattern for most network narratives on film: several connections link many of the nodes. Here’s a diagram for Love Actually.

This chart is oversimplified because it doesn’t account for other relationships. Colin, for example, as the sandwich delivery boy, interacts with several of Harry’s employees. Still, at a glance you can see a fairly tight network.