Archive for the 'Film technique: Screenwriting' Category

Somewhere it’s always GROUNDHOG DAY

Phil earns his groundhog halo.

Kristin here–

Back in 1999, my book Storytelling in the New Hollywood (Harvard University Press) was about to be published. It was an attempt to suggest that, contrary to the talk of “post-classical” or “post-Hollywood” norms having taken over American filmmaking, the most important classical principles that had been at work since the 1910s were still going strong.

I outlined those principles in the opening chapter, discussing character goals, deadlines, dialogue hooks, unity, and the like. I also argued that, based on my analysis of many films from the 1910s to the 1990s, the vast majority of features followed a structure involving four large-scale parts, or acts–not three, as the popular Syd Field model would have it.

To do that, I analyzed the techniques of ten films usually considered to be models of unified, sophisticated narrative structure: Tootsie, Back to the Future, The Silence of the Lambs, Groundhog Day, Desperately Seeking Susan, Amadeus, The Hunt for Red October, Parenthood, Alien, and Hannah and Her Sisters.

The book was not intended to be a screenplay manual as such, though I know it has been used in some classes and by some aspiring screenwriters.

Ordinarily the press would have asked me to name some prominent film scholars who could be asked to write blurbs for the cover. It occurred to me, though, that it might be better in this case to take each chapter and send it to its director and to its main screenwriter and ask them for blurbs instead.

That turned out to work pretty well. Several didn’t answer, and other answered too late to be included. I ended up with three blurbs of which I am very proud, from Ted Tally for The Silence of the Lambs, Susan Seidelman for Desperately Seeking Susan, and from Harold Ramis for Groundhog Day.

Ramis’ recent death prompted me to dig out that old file. He had written back to my editor not with a sentence or two to use as a blurb, but with a page-and-a-half letter on the subject; it included a blurb down toward the bottom. It’s a letter that reflects how kind and smart Ramis was, and how much he had thought about writing and narrative–even though the process of writing screenplays was probably largely an intuitive one. It shows that he knew something about academic film studies, even if he had some “quibbles” with them. I certainly never meant to suggest that everything I pointed out in the films I analyzed was intended by the director and/or screenwriter. I would say that everything I pointed out was a result of their skill and experience. Even when something happens by accident during filming, someone has to decide whether or not to keep it in.

Rather than just sticking the letter back in the file, I thought I would share it with you. Having a little more of Ramis available can’t be a bad thing.

Dear Lindsay,

Thanks for sending the chapters of Kristin Thompson’s book Storytelling in the New Hollywood and please convey my thanks to Ms. Thompson for including Groundhog Day among the “modern classics.” My only quibble with scholarly film analysis is the occasional tendency to read more significance into certain details than was actually intended, or to think that certain accidents of production, on-set discoveries, or improvisational dialogues were planned and scripted. I realize, from a Deconstructionist point of view, it hardly matters what I think anyway, so let me set aside my minor quibbles and congratulate Ms. Thompson on her new book. If you would, please pass this letter along to her.

I am not a student of screenwriting so I’m afraid I can’t comment intelligently on Ms. Thompson’s theoretical model. Certainly, the fact that most movies are about two hours long will determine to a large extent the length of the set-up, the placement of the crisis, the climax, and the denouement, but rather than look at films in terms of “acts,” I prefer to think in terms of “actions,” as if the narrative line were a string of pearls, dramatically linked, each taking the audience forward to the next point. If any particular action doesn’t advance the plot or contain some new information, it doesn’t belong in the narrative. As a writer I generally proceed more intuitively than structurally. As Ms. Thompson suggests, I suspect that most of us have simply absorbed the classical film structure during our formative years as members of the audience.

When I was hired to write my first Hollywood screenplay, Animal House, the producer handed my collaborators and I paperback copies of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and said, “This is what a good screenplay looks like. Just do that.” More than twenty years later, my only useful conclusion about structure is that nothing will work if you don’t have interesting characters and a good story to tell. One can argue for or against the three-action structure, but, whether or not there are consistent rules about the :well-made” screenplay, it’s already true that there are more well-constructed, formulaic screenplays than there are good ones. Also, one must always keep in mind that Hollywood films are almost invariably rewritten by additional (though not always credits) writers. One writer may be thought of as strong on structure, good for a solid first draft, another may be known for his dialogue, others for punching up action or comedy. Also , the Hollywood writer is always responding to script notes from studio executives, story departments, his producers, the director, and from his principal actors. In this convoluted and often tortured process, it’s sometimes impossible to attribute the final screenplay to the calculated intentions of one writer or team, and it’s often left up to a panel of Writers Guild arbiters to determine screen credit.

I didn’t intend to write such an inflated letter but there’s a lot to say on the subject and I have a considerable amount of experience.

If it’s useful to you, you may quote me as saying that Ms. Thompson’s insightful analysis of Groundhog Day and of the screenwriting process in general should be fascinating to both writers and audience alike. More thoughtful writing and more discerning audiences can’t help but lead to better movies, and this informative and provocative book is a step in that direction.

Best of luck on the publication of Storytelling in the New Hollywood and please feel free to contact me if you need any further comments.

Sincerely,

Harold Ramis

Harold Ramis as Allan “Crazy Legs” Hirschman (SCTV, “Indecent Exposure,” 1982).

Film-industry pros share secrets in Vancouver

Kristin here:

Even while tempting us with many, many films, the Vancouver International Film Festival runs an event that could all too easily lure us away from viewing and into the world of film-industry gurus: the Film and Television Forum. Its website describes it as “four days of professional development for senior and emerging professionals, from financing to production, to marketing and distribution, to storytelling and engagement.”

In an ideal world, we would attend all of the sessions, but they run concurrently with as many as eight films showing elsewhere. Two talks were particularly appealing, though, given our interest in the  practice of making films within the mainstream American industry. I slipped away to hear master-classes by Terry Rossio (screenwriter for all of the Pirates of the Caribbean films) and Walter Murch (editor of Particle Fever, shown at the festival, and sound designer on many films, including Apocalypse Now).

practice of making films within the mainstream American industry. I slipped away to hear master-classes by Terry Rossio (screenwriter for all of the Pirates of the Caribbean films) and Walter Murch (editor of Particle Fever, shown at the festival, and sound designer on many films, including Apocalypse Now).

Terry Rossio

Rossio’s modest title was “Revisions,” though his discussion ranged far beyond advice on how to rewrite a script. He immediately won over the audience, clearly many of them professional or aspiring screenwriters, by passing around a flash-drive and inviting anyone with a script-in-progress on their laptop to put some pages on it. He would end the session by making some impromptu revisions of those pages.

I’m not secretly working on a screenplay or even aspiring to write one, but if I were, I think I would have gleaned some valuable tips from Rossio’s talk.

Most panels and seminars tend to be too general, he said. They “focus on the business side, tell personal anecdotes,” and so on. He feels that it is probably impossible to teach screenwriting: “No, the better question is, can writing be learned?” Yes, but people must teach themselves.

Writing and revising

To Rossio, one crucial thing to learn is that finishing a story is not the end. One should have both doubt and faith: doubt that a story or scene is good enough, and faith that it can be better.

Revision, according to Rossi, is “talent reapplied.” One may have a limited amount of talent for writing, but it can be stretched by reapplying it over and over during the revision process.

Rossio is a big advocate of succinctly creating a strong visual sense in each scene. Even on Rossio’s desktop he comes up with a distinctive icon for each folder (see top): a Rubik’s cube for “Screenwriting,” a little gramophone for “Music,” and so on.

For Rossio, each scene should consist of:

- Opening image

- Key moment (character revelations, reversals, etc.)

- Throw (i.e., the setup for the next scene)

Apart from visual imagery, writing should be situation-based: “Every scene you write must be an obvious situation.” A screenplay is a string of situations, which creates a compelling interest in the scene. His example was two people discussing an important deal in a car on the way to a meeting. The dialogue might become boring because of the static setting, but the writer could make them experience car trouble and have their discussion outside the car while worrying whether they will make it to the meeting: “The easiest way to create interest is through some sort of dilemma.”

One important technique of revision is what Rossio calls “performance dialogue.” Writers tend to compose speeches in full, grammatical sentences, but that doesn’t sound natural in spoken dialogue. Rossio takes these complete sentences and starts to eliminate words: “Less words allows for performance the actor will be performing in between the syllables.” He adds, “If you give an actor a very long line, they can’t manipulate that into an emotion. But a shorter line allows them to express the subtext or nuance of what’s going on.”

This advice led to a question from the audience about how a writer can convey to the director and actors what he or she intended the nuances of a scene to be. Rossio suggested three possibilities:

- Become a director. The director is the one who puts things on the screen. The writer makes suggestions about what to put on the screen.

- Negotiate having the power to be on set during shooting.

- Annotate the screenplay.

The third point caused quite a bit of interest and is an unusual approach that Rossio himself has recently adopted. He writes a normal script, fairly compact and easy to read. But he includes endnote numbers that refer to a separate document, a list of annotations. These might be something like an indication that a certain moment in the film is a reference to the opening of Raiders of the Lost Ark or suggestions about special camera angles. Rossio has not used this tactic often enough to gauge whether directors in general would appreciate it, but he did have a good response to the first annotated script he provided.

Rossio dislikes all the screenwriting software on the market, but he showed off a system that he devised himself. The screen below shows the list of scenes for his current project, Masters of the Universe. Each scene is identified by a single word, such as “Vengeance” or “Snake.” The ones that are finished are highlighted in color. (I don’t believe Rossio mentioned the difference between the purple and the yellow highlighting.) The scenes can be switched in order with their labels automatically re-numbered.

One advantage of this system is that the author opens only one scene rather than the whole script. Dealing with something that may be about four pages long is less overwhelming. Rossio also finds that his system facilitates sharing drafts of scenes with a collaborator.

Tips for pitching

In keeping with his emphasis on the visual aspects of a screenplay, Rossio recommends that writers make up a brief pre-viz that captures the essence of the script’s premise. Increasingly, software is becoming available that would allow technically adept writers to create demo clips on their own. For writers unable to do this, Rossio suggests that in a highly competitive market, they should get an effects house to do the job for them. These days even some directors are using this approach in trying to get a job.

Rossio was asked a question about pitching to get a job revising an existing script. He had four suggestions.

First, read the script that is to be revised. Surprisingly, not all writers do that. If it’s based on a literary property, read that, too. A lot of writers just wing such pitch meetings.

Second, take along a presentation board. It can be used for breaking down the script or drawing images.

Third, write a recap of the script as it exists and be ready to discuss specific possible changes.

Fourth, go to the trouble of having two or three specific images ready to show. If the VIPs like the images, they can get access to them only by hiring the writer.

I think if I were a scriptwriter, aspiring or otherwise, I would consider that Rossio packed a lot of useful information into his 75-minute presentation. He also chose two of the script excerpts submitted by audience members and gave their authors some quick and helpful suggestions for revisions.

Walter Murch

As far as I could tell, Murch’s talk had no title, but the concept he threw out early on was “fungibility,” one meaning of which is being capable of changing easily. The example he gave was a caterpillar changing into a butterfly. Murch was referring to the digital revolution in film editing. This was not so much a how-to talk as an attempt to demonstrate the dramatic changes that have come about as a result of rapidly changing technologies.

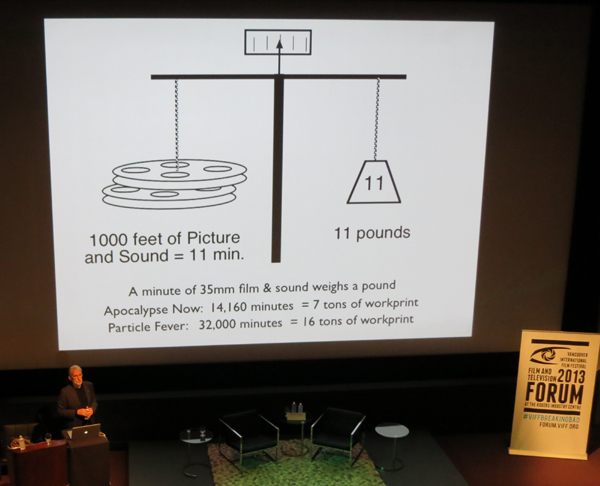

Murch showed a photo of himself struggling with 35mm film strips in editing Apocalypse Now in the 1970s (above). Now, of course, there would be no such physical sorting and splicing. He then pointed out the sheer weight of film, which has been entirely eliminated:

As the graphic shows, a single 1000-foot reel of 35mm film weighs 11 pounds. The strips of Apocalypse Now in the photo above were part of workprint material totaling 7 tons. If Murch’s latest film, Particle Fever, had been edited on 35mm, he would have had to deal with far more, 16 tons of film. It simply would have been impossible to edit such a quantity of footage. (Would a hard-drive with a complete feature film on it weight measurably more than a blank one? he wondered.)

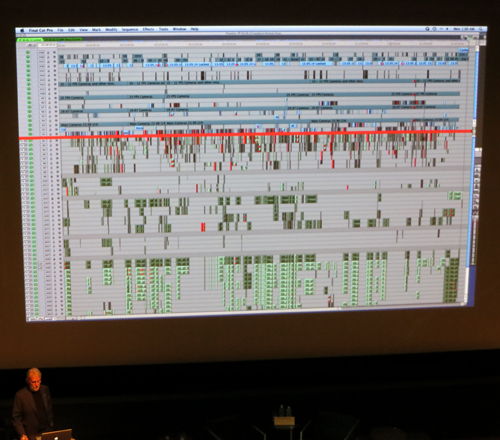

For Particle Fever, Murch used Final Cut Pro 7–an announcement that led to scattered applause from the audience. Like Murch, users of that program are loyal to it, but as he pointed out, a 32-bit program simply can’t keep up with modern demands for memory. While editing, he kept running into situations where there was no memory left, and he had to use elaborate and time-consuming methods to free up storage space. (The film ended up with 18 terabytes of material stored.) On his current project, Tomorrowland, he is using a 64-bit Avid program and has had no problem running out of memory.

(Tomorrowland is being made here in Vancouver, which is presumably why we had the privilege of Murch’s participation in the forum.)

Murch showed a timeline graphic for Particle Fever, with multiple image track, dialogue tracks, effects tracks, musical tracks, and so on. Each small horizontal line represents a separate track:

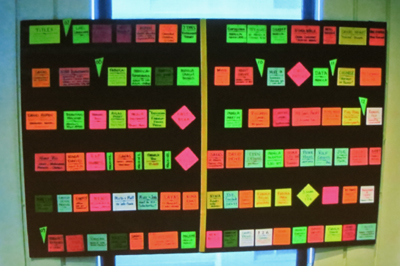

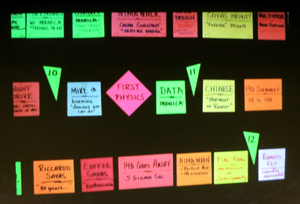

Even while working on this level of complex technology, however, Murch sticks to simple methods for some of his planning. He creates a “scene board” using cards coded with colors, sizes, and shapes . The little green triangles create a chronology, giving the years covered by each set of scenes:

As with Rossio’s system of storing his scenes in a way that allows him to change their order, Murch can move the cards around if the structure of the film changes. Murch put it this way: “I would suggest reversion to kindergarten.”

He also showed some photos of his workspaces for various projects. One was intriguing for indicating how important perspective is for editing. One workroom contained a 50-inch monitor for playing back scenes as he edits them. (See bottom.) Note the little white figures of a man and a woman at the bottom corners of the screen. Murch wanted to keep scale in mind, and the figures represent normal-sized people at the proportionate size they would appear if the monitor were a forty-foot theatrical screen.

This photo inspired someone during the question session to ask whether the increasing tendency for people to watch movies on very small digital screens has influenced Murch’s editing decisions. He replied that it has to some extent, though from the beginning of his career at the end of the 1960s he has had to keep the smaller television screen in mind. Yet he does not edit primarily for the tiny images on mobile devices: “If you cut for the big screen, it will work for the small screen. If you cut for the small screen, it won’t work as well for the big screen.” The Master speaks. So far, the theatrical experience remains the basis for moviemaking.

The Guardian has a video interview with Walter Murch discussing Particle Fever.

A monitor in Walter Murch’s workspace, with two white human figures at the lower corners to indicate scale.