Archive for the 'Film technique: Sound' Category

The poet of dynamic immobility: Ennio Morricone: A guest post by Jeff Smith

Ennio Morricone holding his principal instrument, the trumpet, in a picture taken in the 1970s. Photo by Roberto Masotti.

DB here: For our blog entry #1001, who better to memorialize Morricone than our stalwart collaborator Jeff Smith? He has provided many music-sensitive analyses of films both recent and classic. Our most popular entries from last year were his two looks (here and here) at the music and musical culture behind Once Upon a Time. . . . in Hollywood. Herewith his warm appreciation of a maestro.

Jeff here:

On July 6, 2020, the legendary composer Ennio Morricone passed away in Rome at the age of 91. As expected, several encomia were published reflecting upon Morricone’s musical genius. Of particular note were reflections by two writers for Variety, film critic Owen Gleiberman and film music historian Jon Burlingame.

The tributes highlighted many notable features of Morricone’s film work: his gift for melody, his sense of humor, his eclecticism, and his amazing productivity. Having written more than 500 film and television scores, Morricone’s compositional output was jaw-dropping. After all, even Josef Haydn wrote only 106 symphonies.

Throughout my own career as a film scholar, I frequently engaged with Morricone’s music. In preparation for the writing of my dissertation, I did an independent study with David on Hollywood film music. My final project? A detailed analysis of the score for Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, complete with handwritten transcriptions of every musical theme and motif I could identify.

I vividly remember the satisfaction I felt in being able to play the main title from start to finish on the piano. It is one thing to read music and play it. It is another to take what you hear and try to put it in some reproducible form on paper. Playing back Morricone’s famous theme, I felt I’d gained insight into the mind of the great composer. That work eventually became the basis for chapter six in my first book, The Sounds of Commerce.

My fascination with Morricone’s work has continued to the present day. Last summer, I wrote a review of Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words, a book of interviews conducted by Alessandro De Rosa. This past April the Criterion Channel posted my most recent “Observations on Film Art,” which examines musical motifs in Morricone’s score for The Battle of Algiers.

That’s close to thirty years of near-obsessive fascination with Morricone’s music and his compositional style. In what follows, I share some additional thoughts on the Maestro’s legacy, offering some insight on the reasons for his seemingly inexhaustible creativity.

The Sicilian defense

The first section of Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words is all about the maestro’s love of chess. Although the composer would describe himself as a hobbyist, his chess skills surpassed those of most amateurs. Morricone played against Boris Spassky, Garry Kasparov, and other Grand Masters. When asked about his passion for the game, Morricone explains that he sees important parallels between music composition and chess. Both activities involve mathematical relations. These relations are further expressed in axes of verticality, horizontality, and graphics.

This initial discussion of chess struck me as a key to understanding Morricone’s creative process. The game of chess is often analogized as a battle where stratagems and tactics are deployed in an effort to outmaneuver – and thus, defeat – one’s opponent. That comparison undoubtedly rings true. Yet when one looks at the board before the game starts, it also represents something simpler: a field of open possibilities. Not every move is permissible, of course. But when you consider possible combinations of moves, the permutations can number in the millions. And even though the rules of chess constrain the patterns of moves that can be made, all of these possibilities are generated by the dispositions of up to 32 pieces on a field of 64 squares.

Morricone seems to approach the blank space of staff paper as though it were a chessboard at the start of the game. A chess player works with sixteen pieces that can be used in various combinations. A composer works with the twelve tones of the chromatic scale to create intervals and chords. As with the chessboard, there are millions of different permutations in the way these twelve tones can be arranged. More importantly, since each note in the scale can be varied by pitch class, duration, articulation, dynamics, and instrumental color, the options seem endless.

Yet while the “terror of the white page” can be an obstacle to the creative process, that has never appeared to be the case with Morricone. Why? I think it is because the composer found a method of composition that reduced the apparently infinite possibilities to the level of the merely multitudinous.

In Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words, the composer characterized himself as a student of the Second School of Vienna. Unlike Arnold Schoenberg and Anton Webern, who were part of the first Viennese School, Morricone tried to transpose the former’s twelve-tone technique into a seven-tone system while retaining the latter’s commitment to the rules of serialism that ordered all other musical parameters. For Morricone, this system had the advantage of enabling him to write tonal music without having to slavishly adhere to its characteristic tensions and resolutions. By adopting Webern’s principles of serialism, the notes, according to Morricone, “are freed from their reciprocal constraints.”

Over time, Morricone learned how to adapt this simplified version of twelve-tone serialism to the needs of each film score he wrote. In some cases, he would work within a pentatonic system. In others, he might base his compositions on a row of six or eight tones. In still others, he might jettison the system altogether.

This simplified serial technique provided Morricone with a compositional framework that was extraordinarily generative. Once the composer has determined the tone row and the ordering of other musical parameters, he simply spins off hundreds of variations that are then fitted to the film’s dramatic situations. The smaller tone row still acts as a guarantor of harmonic unity. Morricone describes it as the music’s DNA, something like an identifying marker in every musical “cell.” Specific changes in rhythm, tempo, orchestration, volume, and tessitura all provide means of refreshing the basic musical schema.

Indeed, Morricone’s compositional system proved so procreant that he sometimes wrote three or four versions of a score’s theme in order to give the director some options to choose from. In Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words, he offers an example with the police triumph theme in The Untouchables. The theme was the last one written for the score, and Morricone prepared three pieces that were recorded with two pianists. He then sent them off for director Brian De Palma’s consideration. De Palma didn’t like any of them. Back to the drawing board,

Morricone wrote three more pieces and shared them with De Palma. In a phone call, the director told Morricone that he still wasn’t convinced. Morricone completed three additional pieces and sent them. This time, though, he included a brief that summarized the strengths and weaknesses of all nine proposals. Morricone himself recommended against variant number six, claiming it was most triumphant and therefore the least convincing. Concluding his story, Morricone asks, “Guess which one he chose?”

After I sniggered at the composer’s dig at De Palma’s musical sensibilities, the larger implications of Morricone’s anecdote began to sink in. My mind was well and truly blown. If Morricone had written eight other themes in lieu of the one that was ultimately chosen, how much music had he actually written for The Untouchables? And if this, as Morricone indicates, was not an isolated case, how many unused cues are likely sitting in boxes somewhere in Rome simply waiting to be discovered? As noted earlier, Morricone had written music for more than five hundred films and television shows. Were the aggregated number of unused cues and alternate versions of themes the equivalent of another one or two hundred scores? And if we trust Morricone’s judgment, some of these versions are actually better than the ones we already know.

All of this is a reminder that Morricone’s output is astonishing. This is evident both in terms of the size of his corpus and the sustained quality of his work over a period of almost sixty years.

Much of that productivity, I think, was fueled by Morricone’s transposition of serialist concepts to the film score. Like the rules of chess, which prohibit certain moves, Morricone’s use of simplified tone rows gave him a set of “rules” that fruitfully limited certain options in terms of melody and harmony, but still preserved the usual range of choices for other musical parameters. It also shaped our sense of Morricone’s style by favoring certain compositional devices over others. Pedal points and ostinati are completely permissible in Morricone’s system. But a rapid chromatic run of the type used in classical Hollywood “hurries” would be out of bounds.

Such a rapid chromatic run is also ill-suited to Morricone’s aesthetic for another reason; it is a musical gesture that implies directional movement. Instead Morricone strives to produce a sensation of “dynamic immobility” in his work, the musical equivalent of the swirls, eddies, and ripples we associate with lake water. The sense of immobility derives from Morricone’s interest in writing tonal music outside of the strict rules governing the Western tonal system. One hears chord changes. But you couldn’t describe any particular change as a modulation insofar as there is no definite key to ground these harmonic relations. Consequently, you discern harmonic change, but without the sense of teleological movement toward a cadence as a definite endpoint.

If Morricone’s approach to harmony strives for a feeling of moving stasis, what then accounts for the music’s dynamism? For Morricone, it is the constant change evident in the other musical parameters: texture, pitch, dynamics, and timbre.

Listen again to the cue from The Untouchables. Do you notice the sorts of surges and swells produced by its chord changes? Does it sound like it moves to a definite endpoint? Or does one instead get the feeling of an endlessly deferred resolution? If those surges and swells produce the latter, that’s Morricone’s “dynamic immobility” in situ.

Morricone’s creative spark seems all the more remarkable when one considers that he worked in a production environment guided by the notion that “I don’t need it good; I need it Tuesday.” That Morricone flourished within this milieu for more than five decades eventually made him “untouchable.”

Roll over Beethoven and tell Tchaikovsky the news

A Fistful of Dollars (1964).

In The Sounds of Commerce, I argued that the 1960s proved to be an important period in the history of the Hollywood film score as the dominance of its neoromantic style began to wane. Driven partly by the popularity of theme songs and soundtrack albums, composers infused the classical Hollywood score with elements of both jazz and pop music. To be sure, those styles all had their place in Hollywood films. Characters performed Tin Pan Alley songs in musicals. Dance bands played jazz as part of the nightlife featured in gangster films and films noirs. And one even heard the occasional bit of Gershwin-style orchestral jazz pop up in a score. The changes I discerned in sixties film scores were more a matter of degree than of kind.

What prompted the change? Besides the emergence of new ancillary markets for film music, Hollywood also saw a generational shift take place throughout the industry, including film composers. Sadly, some of the greatest proponents of the classical Hollywood style, such as Herbert Stothart, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, and Victor Young, were dead before 1960. Others, like Roy Webb, Max Steiner, and Miklós Rózsa, remained active, but they saw fewer assignments come their way.

Taking their place was a new breed more attuned to changes in the jazz and pop idioms. Instead of aping Gershwin, these new composers were more likely to draw upon swing music or West Coast jazz. Similarly, several film composers also began to incorporate elements of pop music’s newest sensation: rock and roll. In an interview I did with Henry Mancini, he described his famous “Peter Gunn” theme as a rock tune due to its “straight eight” rhythms and its twangy guitar line. Not coincidentally, John Barry’s arrangement of the James Bond theme foregrounded Vic Flick’s guitar in a similar way. The middle section of the tune features a swinging, Dizzy Gillespie-ish break. But that guitar sound stood out, much closer to Carl Perkins than to Wes Montgomery.

During the 1960s, no film composer was as thoroughly steeped in the rock idiom as Ennio Morricone. Yet, unlike Mancini and Barry, who were drawn toward rockabilly in their use of electric guitar, Morricone cribbed from the slightly more modern sounds of early sixties surf-rock. Morricone tells Alessandro De Rosa that he used the electric guitar long before he wrote the scores of his spaghetti Westerns, albeit not as a solo instrument. Yet he opted to feature the electric guitar in the main theme of A Fistful of Dollars because he liked “its tough and sharp timbre,” which he felt was perfect for the atmosphere of the film.

De Rosa also notes that the Shadows’ surf music was extremely popular on Italian record charts in the early sixties, especially their Western-themed classic “Apache.” The distinctive twang of Hank Marvin’s Fender Stratocaster was widely imitated by Italian beat bands. By the time A Fistful of Dollars was in production, the Shadows’ influence had seeped into Italian popular music culture. When they topped the Italian charts in 1963 with “Geronimo,” another paean to the American west, it probably seemed quite natural to make the Stratocaster’s sound the centerpiece of Leone’s groundbreaking film.

Morricone made the electric guitar the star of many more spaghetti Western scores. But none so prominently as the “Man With the Harmonica” theme of Once Upon a Time in the West. Famously, the film features no main title in the opening credits, “scoring” the scene instead with the sounds of the wind, a creaking mill, the clanging of a metal gate, and an especially persistent horsefly (among other things). Morricone’s score doesn’t come into Leone’s film until about the twenty-minute mark. But when it does it makes quite an entrance.

Frank and his gang have just slaughtered the McBain family. The only survivor is a red-headed boy who comes running out of the house after hearing gunshots. As he comes into a close-up, Bruno Battisti D’Amario’s guitar starts blasting through the theater speakers. The sound is loud and distorted, cutting through the silence like an axe through a chicken’s neck.

In his instructions to D’Amario, Morricone insisted that the theme was meant to “wound the audience’s ears like a blade” the first time we hear it. As a coup de théâtre, it is brutally effective. I’ve seen it more than twenty times, and the moment never fails to give me chills. Here we see Morricone experimenting with the timbre of the guitar by heightening the effects of high volume and high voltage to overdrive the power valves of the amplifier. The effect was such that some critics even described Morricone’s score for Once Upon a Time in the West as a sort of “post-Hendrix” rock. The comparison was undoubtedly flattering. No musician had done more to explore the timbral possibilities of the electric guitar than Jimi Hendrix.

Morricone experimented in other ways that seemed to merge elements of avant-garde classical music with more vernacular forms. Consider his “Harmonica” motif in Once Upon a Time in the West alongside Henry Mancini’s main title for Wait Until Dark, which was released about a year before Leone’s epic. Both film scores explore microtonal effects, albeit in quite different ways.

In Mancini’s case, he asked the studio to give him two pianos that were tuned a quarter tone apart. He then asked his two performers to play the chords of an accompaniment figure in rapid succession.

The dissonance produced through this effect is unlike any produced in atonal writing. There the composer deliberately emphasizes intervals that create a sense of disharmony, such as minor seconds, major sevenths, and tritones. Yet Mancini’s microtonal experiment does something else entirely. Our ears tell us we should be hearing the same chord, but the repetition on the detuned pianos sounds a bit off. Mancini’s score evokes a kind of dislocation well suited to Wait Until Dark’s generic trappings as a psychological thriller. The effects, though, were even more pronounced for the two pianists who played on the main title. Pearl Kaufman and Jimmy Rowles both reported having to take frequent breaks during the recording sessions. The sort of “swimming” effect produced by the detuned pianos gave them a feeling of vertigo and nausea commonly found in motion sickness.

Morricone’s approach to microtonal harmonies proves to be much more elemental: the wavering sounds of two notes played on the harmonica, ostensibly a half step apart. Anyone who has played a harmonica knows it requires great breath control. Inhale and you make one pitch. Exhale and you make another. Beyond that, skilled performers can also bend pitch on a harmonica by changing their embouchure. Harmonica players can also use their hands as dampers, altering the sound in much the same way a wah-wah mute alters the tone of a trumpet.

All of these techniques give the harmonica player a number of means to bend pitch. Morricone takes full advantage of them with the “Harmonica” motif in Once Upon a Time in the West.

Listening to this passage, one can hear how Franco De Gemini’s mouth harp straddles the fence between sounding bluesy and sounding strident. Morricone viewed the half-step relation in the motif as a key element in building musical tension since it is heard in the flashback that explains Harmonica’s life-long quest for revenge. Yet De Gemini’s subtly wavering pitch seems to capture the full range of microinterval variants that fall between the D# and E that comprise the last two notes of the motif.

Both composers’ explorations of microtonal effects prove effective. But the precision of the quarter tone difference in Mancini’s detuned pianos gives the music a mechanistic quality that seems cold and brittle. By contrast, the harmonica’s fluid pitch-bending in Once Upon a Time in the West is looser, freer, more improvisatory – all of which fits the types of vernacular music played on harmonica.

This effect was enhanced by Morricone’s recording techniques. He first recorded the orchestra and then recorded De Gemini’s harmonic track individually. Although the latter recording was less precise, Morricone said that “the tension generated by the performance made his harmonica float over the orchestra. Now on the beat, then behind it, this time ahead….in short, it was almost as though it was fluctuating.”

Morricone’s compositional and recording techniques in Once Upon a Time in the West might seem less daring than Mancini’s more avant-garde experiment in Wait Until Dark. Yet Morricone’s music gains something in its more organic placement within Leone’s film. The harmonica’s wavering pitch is akin to the sorts of portamenti and string-bending frequently heard from saxophones, guitars, and basses in a multitude of rock and roll songs produced throughout the idiom’s history. And the harmonica as an object has long been a common feature of the Western’s iconography. In this way, Morricone’s experimentation is grounded in the dramatic, stylistic, and symbolic structures of Leone’s epic.

A horse of a different tone color

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966).

Unquestionably, Morricone’s most audible innovations came through his approach to orchestration. As nearly every obituary noted, his unusual combinations of instruments became a hallmark of the Morricone sound. In a summary of the signature elements found in the score for The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, The Economist declared:

And then there is the freewheeling range of sounds with which he chose to make that music: the whistling, the yodeling, the gunfire and the squeaky ocarina, an ancient Italian wind instrument that looks like a sweet potato and is better known to a younger generation as the soundtrack of a Nintendo video game.

As I suggested above, Morricone was part of a cohort that moved outside the neo-Romantic style of film composition associated with the studio era. Unconventional orchestrations were an important part of that push.

Several factors provided impetus for this change. One was the embrace of jazz and pop styles. Incorporating those elements often meant writing for the instruments typically associated with those idioms. Mancini, John Barry, Frank De Vol, and Nelson Riddle all were prominent exponents of this approach during the 1960s. Indeed, many of Mancini’s orchestrations simply add strings to the usual forces of a jazz big band.

A second factor was the breakdown of the studio system in the 1950s. The majors’ retrenchment saw them making fewer films and reducing their overhead costs. They sold off parts of their backlots and leased their soundstages to independent producers or television crews. They also tried to shed labor costs, including those associated with maintaining an in-house orchestra.

This was bad news for musicians, who suddenly found themselves working in a gig economy as independent contractors. But it was good news for composers who now could write music for something other than a standard chamber orchestra. (During the Golden Age, studio bosses would sometimes chafe at the notion of hiring extra musicians, since they were already keeping as many as fifty regularly on call.)

With more flexible options when it came to musical labor, composers began to experiment with more unusual combinations. Whereas the typical studio orchestra employed one or two keyboardists, Bernard Herrmann arranged one cue in Journey to the Center of the Earth for nine organs. Three organists played electronic organs and one played a cathedral organ.

In many ways, Herrmann’s experiments with orchestration provide an interesting foil for Morricone’s own flights of fancy. For two of the scores Herrmann wrote for Alfred Hitchcock, he self-consciously limited his palette to the sounds of a single section of the orchestra. On Psycho, Herrmann wrote only for strings, claiming that the more monochrome sound was fitting for a black and white film. Yet, within that uniformity, Herrmann wrought an extraordinary range of subtle differences in timbre through the use of pizzicato, mutes, and unusual bowing techniques. The famous bird shrieks produced by the violins during the shower murder recall the avant-primitivism of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. But Herrmann achieved this effect only with strings rather than a full orchestra.

Herrmann did something similar in his unused score for Torn Curtain, which was written for sixteen French horns, nine trombones, two tubas, twelve flutes, two sets of timpani, eight cellos, and eight basses. For Torn Curtain, Herrmann’s restriction of his palette was inspired by the setting rather than the cinematography. By emphasizing the low brass and lower-pitched strings, the composer sought to find a sonic equivalent to the drab cheerlessness of life behind the Iron Curtain. Alas, Hitchcock rejected the score under pressure from Universal to produce a saleable music tie-in. The studio wanted something like the Beatles. What they got from Herrmann was more like John Philip Sousa on an acid trip.

If Herrmann’s orchestrations were the musical equivalent of a Mark Rothko painting, exploring a range of subtle shadings within a single color, Morricone’s were closer to the collage principles of Robert Rauschenberg. Just as Rauschenberg’s work juxtaposed unconventional materials and objects within a single canvas, Morricone enjoyed the wild, discordant collisions that could come by combining oddball instruments with one another. The composer is often described as a postmodernist because of his “everything but the kitchen sink” approach to orchestration. No doubt this is one of the reasons his work was so appealing to “downtown” musical avant-gardists like John Zorn.

Consider, for example, the way Morricone uses vocal textures throughout his score for The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. It features Edda Dell’Orso’s gorgeous soprano, natch. But it also features a variety of other vocal sounds, some of which border on the “unmusical.” These include the famous “coyote incipit” that has become something of a meme for the spaghetti Western more generally.

There are also plenty of other chants, grunts, and yelps that add their flavors to the musical stew. Morricone even had his singers vocalize through various trumpet mutes to produce the “wah-wah-wah” that is a motivic counterpart to the coyote incipit.

Morricone also made marvelous use of library effects to incorporate the sonic iconography of the Western into his score. We hear gunfire, whipcracks, and ricocheting bullets as elements of rhythmic punctuation throughout the music of The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. (Since cowboy yells and whipcracks both appear in the opening theme of Rawhide, perhaps both of these tactics are a sly reference to star Clint Eastwood’s television career.) Even these audacious touches are supplemented by simple, but effective solutions to musical problems. In need of a rhythmic pulse underneath the melody, Morricone coaxed Bruno D’Amario to tap the pickup on his electric guitar.

All of this suggests something very Cagean in Morricone’s approach to orchestration. It is though he took the idea of Cage’s “prepared piano” in which different objects could be laid on the strings of piano’s soundboard, and applied it to the full orchestra.

What is the sound of one wing flapping?

The Mission (1986).

Although Morricone’s spaghetti Western scores displayed his boldest experiments in orchestration, his interest in unusual sonorities continued throughout his career. Some choices are a bit more conventional than others. But they always strike me as inherently right. The oboe seems like a fairly idiosyncratic instrument for an 18th-century Jesuit missionary. Surprisingly, though, its melancholic yet dulcet melismas are a perfect complement to the big sound of The Mission’s double chorus, the latter itself inspired by the luminous sacred music of Palestrina.

Or think of Morricone’s use of the panpipe. He seems attracted to its airy timbre, using it in several scores throughout his career. Yet, comparing its appearance in both Once Upon a Time in America and Casualties of War shows that the panpipe’s sound resists any easy associations. In Leone’s gangster epic, the panpipe is introduced in “Cockeye’s Theme” in a scene where Noodles buys a one-way ticket to Buffalo. After completing his purchase, his attention is drawn to a large poster encouraging tourists to visit Coney Island. The music suggests Noodles’ memories of childhood and his grief after hearing the news that his three childhood friends all died in a battle with federal agents.

It comes back, though, at the moment when Dominic is killed by Bugsy, a rival gang member. As Morricone noted, Leone identified this scene “as a definite point of no return in the story, the watershed marking the end of youth.”

In contrast, for De Palma’s combat film, Morricone used two panpipes in the theme he wrote for the young Vietnamese woman who is abducted, raped, and killed by US soldiers. Here the motivation was something that struck Morricone in the staging of her death.

She buckles her legs like a dying bird, before tumbling down from the high ground. I imagined a theme based on just a few notes for two panpipes, which by ping-ponging their sound, evoke the slowing fluttering of a bird’s wings shortly before death.

At first blush, Morricone’s description of the scene sounds like “Mickey-Mousing” where the music accents a character’s actions, movements, or gestures. But what Morricone actually gives us turns out to be much more sophisticated. A classical Hollywood composer like Max Steiner might have caught the girl’s collapse through a downward glissando or a rapid, descending scale run. Instead Morricone gives us a different musical gesture – the alternation of two notes on the panpipe – to suggest an action not visible onscreen: a dying bird’s fluttering wings.

As is evident in the clip, we hear the two panpipes play over the image of the young woman’s broken body. Yet Morricone associatively links it to the birdlike movement seen about a minute earlier: the buckling of her knees as she falls.

A moment such as this one nicely captures Morricone’s gift for storytelling. Many of Morricone’s fans treat his scores as absolute music, often listening to them repeatedly without ever watching the films they accompany. But Morricone also had a gift for translating a film’s larger themes and meanings into musical forms.

Morricone achieved fame for his beautiful melodies, rich harmonies, and surprising orchestrations. None of that would be very meaningful, though, if these elements weren’t firmly rooted in the composer’s extraordinary dramatic sense.

The greatest?

The Hateful Eight (2015).

At the end of Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words, Alessandro De Rosa asks the composer if there was a specific moment when he realized he’d become one of the greatest, most influential composers of the century. Morricone gets flustered by the question, claiming such judgments are premature. In music, it takes hundreds of years to determine whether one’s work endures. He then adds a polite, but banal conclusion, saying it is wonderful to be appreciated and even better to have one’s music reach so many people.

Still disarmed by the question, Morricone continues hesitatingly:

The greatest of the century? It is difficult to reply….Oh dear…. where did you hear this?

De Rosa responds, “It was just to provoke your vanity…” Acknowledging the trap set before him, Morricone smiles and replies, “You don’t say….I figured!”

Morricone’s humility might be a tacit recognition that he’s had the great fortune to write music for the movies–one of the greatest engines for pleasure that the world has ever seen. A great film surely benefits from a great score. Yet it can seem that the composer is just along for the ride.

Still, Morricone understood that his music was often better than the films it accompanied. As he well knew, fortune gives with one hand and takes with the other. Morricone wrote music for masterpieces like Days of Heaven. He also worked on schlockfests like The Exorcist II: The Heretic.

Perhaps more than other craft positions, the lot of a film composer can seem unique. Music exists as its own formal system. But film scores are always written in the service of something else and judged accordingly. Directors often hope in vain that a composer can salvage a bad scene. Yet composers themselves will say they’re not miracle workers. And even when the score can stand on its own, some pugnacious critic will ask, “Should it?”

When I was doing the initial research for my dissertation during the early nineties, I recall some film music critics dividing the field into craft workers and stylists. The paradigm case for the former was a composer like Jerry Goldsmith, who subordinated his personality to the dramatic requirements of the work. Goldsmith could write a bittersweet jazz melody for Chinatown, a stirring horn call for the war epic Patton, cartoonish “Mickey-mousing” for the comic fantasy Gremlins, and outré dodecaphonic themes for sci-fi adventures like Planet of the Apes and Alien. Binge-watch all five films and it would seem hard to believe the music was all the work of a single person.

Stylists, on the other hand, were composers who had created such a distinctive sound that their music could not be mistaken for that of another. All three of the composers featured in my book seemed to fit that rubric – Henry Mancini, John Barry, and Ennio Morricone – a factor that likely contributed to the popularity of their scores in ancillary markets.

Looking back almost thirty years later, the label of stylist fits the work of Mancini and Barry quite well. In fact, I have anecdotal proof of the latter in my first viewing of Michael Apted’s espionage thriller Enigma. Halfway through film, I wondered to myself who had written the score since it sounded a lot like John Barry. Checking the poster afterward, my hunch was confirmed; it was John Barry!

For Morricone, though, the “stylist” label seems misapplied. At the time, this was due to the fact that he was so strongly associated with the spaghetti Western. He had written music for more than thirty films in the cycle and had come to define it in the public imagination. It is telling that the scores written for other spaghetti Westerns by Luis Bacalov or Riz Ortolani sound like Morricone facsimiles.

Identifying Morricone so closely with the spaghetti Western, though, ignores the inspired music he wrote for so many other genres: horror films, gangster films, thrillers, historical epics, political satires, and even the occasional romantic drama.

Take five Morricone classics not so randomly selected: Teorema, Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion, Cinema Paradiso, Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, and The Hateful Eight. Could any other composer have written the notes that we hear? Probably not. They all seem to bear the distinctive Morricone signature. Yet they are also so unlike one another that it seems unfair to suggest that he didn’t mold his sound to the specific needs of each film. For Morricone, we have to throw out the “either/or” implied by the rubric. He’s both a craft worker and a stylist.

If that seems like a copout on my part, it’s one I will happily embrace. For me, like many others evaluating Morricone’s legacy after his death, his music is both cerebral and visceral. It warms the heart and tickles the brain, sometimes simultaneously. And that seems rare for much 20th-century concert music, which even at its best, can feel quite cold and analytical.

Thirty years later, Morricone’s music still enthralls me in a way that’s unlike that of any other film composer, especially when the score is heard coming from the big screen. I’ve had the great pleasure of screening a 35mm print of The Untouchables the past two years. Hearing Morricone’s main title played back in Dolby Stereo with a proper subwoofer, I still get goosebumps. I even anticipate the massive bass drum hit that punctuates the rhythms played by brushes on the snare. If the stinging guitar chord that introduces Frank was intended to sound like a stab, that bass drum sound is the musical equivalent of a gut-punch.

Ciao, Maestro! You will be missed. Yet your music will live on, perhaps even for centuries. For my part, you’ve given me hundreds of joyful moments at the cinema and a lifetime of wonderful memories.

Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words can be found here. If you want to learn more about his music, this is a great place to start. It includes reproductions of Morricone’s handwritten musical notation. It also includes a thorough survey of both Morricone’s film scores and his concert works.

My review of Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words is here. A brief discussion of Morricone’s score for The Hateful Eight can be found in my 2016 Oscar preview. Incidentally, Tarantino used Bernard Herrmann’s rejected score for Torn Curtain for the excerpt from Rick Dalton’s action film The 14 Fists of McCluskey in Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood. The cue can be found here and the scene from Tarantino’s film is here.

My chapter on Morricone’s spaghetti Western scores can be found in The Sounds of Commerce.

Henry Mancini discusses his score for Wait Until Dark in his autobiography, Did They Mention the Music? Bernard Herrmann’s score for Psycho has been analyzed by several film music scholars. Among the best is Fred Steiner’s “Bernard Herrmann’s ‘Black-and-White’ Music for Hitchcock’s Psycho,” anthologized in Elmer Bernstein’s Film Music Notebook: A Complete Collection of the Quarterly Journal, 1974-1978. Details of Herrmann’s orchestrations for his rejected score for Torn Curtain can be found in the liner notes of conductor Joel McNeely’s recording. They’ve been posted here.

The chess portrait above is by Riccardo Musacchio.

Morricone waits backstage at a 2010 concert of his work at the Royal Albert Hall in London. Photo by Roberto Musacchio.

When worlds collide: Mixing the show-biz tale with true crime in ONCE UPON A TIME . . . IN HOLLYWOOD

Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood.

Jeff Smith here:

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood might turn out to be the buzziest film of 2019. Some of this water-cooler talk is due to its unusual status within an ever-enlarging field of true crime stories. (Call it a “not quite true” crime story.) Indeed, the genre is hotter than ever thanks to a bevy of new podcasts, telefilms, and miniseries.

Industry analysts, though, are also keen to interpret Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s box office fortunes. As that rare big summer release that is neither a sequel nor a franchise title, it can be seen as a test of whether original content can survive amidst heavily marketed, presold tentpoles.

The lesson so far? To quote William Goldman, “Nobody knows anything.” In The Washington Post, one unnamed studio executive warned, “I don’t see any blue-sky meaning here.” The executive added, “This movie has assets that almost no other film has. That’s what drove it.” At least one of those assets is Tarantino himself, who is a brand, if not a franchise. Fans know what to expect in a Tarantino film, which is why the film is sui generis when it comes to this summer’s slate. Due to its unique IP, it can’t really be compared with films like Men in Black International or Spider-man: Far from Home. Yet thanks to Tarantino’s larger than life presence, it also isn’t Long Shot or Booksmart or Stuber.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is catnip to Tarantino nerds like me. It has the usual surfeit of references to obscure films and television shows. Some of these are deftly interwoven into the story itself. It boasts a carefully curated soundtrack that unearths “some-hits” wonders. It also contains scenes depicting nasty yet comical violence, a hallmark of Tarantino’s work ever since Reservoir Dogs.

At first blush, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood would seem to be Tarantino’s most linear film. Yet it still displays certain continuities with his oeuvre in terms of story structure and technique. Although the film eschews the chapters and title cards found in Pulp Fiction and Kill Bill, it still contains elements of what David calls “block construction.” In the case of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, it is all about threes. The plot is structured around three days in the winter and summer of 1969: February 8th, February 9th, and August 9th. Each “chapter” is introduced showing the date via superimposed text. And all three chunks of narrative crosscut among the activities of three actors – Sharon Tate, Rick Dalton, and Cliff Booth – as they try to adapt to changes in the film and television industries.

If all of this assures that you’d never mistake Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood as the work of another director, other elements show Tarantino striking out in new directions. Chief among these is his mash-up of two normally distinct story types: the show-biz tale and the true crime yarn. Think of it as Singin’ in the Rain meets In Cold Blood. In what follows I outline some of the ways that Tarantino adapts his signature style to two well-established storytelling options: the multiple draft narrative and the network narrative. I also consider the effects Tarantino’s counterfactual history has on the conventions of the show-biz tale and the celebrity biopic.

My analysis contains major spoilers. If you haven’t seen Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, stop reading now!

My world and welcome to it

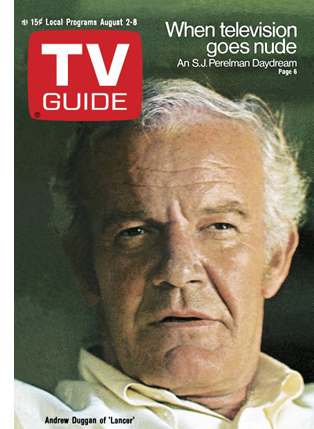

Quick trivia question: what actor was on the cover of TV Guide during the week that Sharon Tate was murdered by the Manson family? Sharp viewers of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood should know the answer. We see Tate’s housemate, Woychiech Frykowski, reading that issue of the magazine as he watches Teenage Monster on late night television.

Give up? It was character actor Andrew Duggan, who played the cattle baron Murdoch Lancer on the TV show of the same name. Yes, that Lancer! The same one that featured Rick in a guest spot some six months earlier.

Give up? It was character actor Andrew Duggan, who played the cattle baron Murdoch Lancer on the TV show of the same name. Yes, that Lancer! The same one that featured Rick in a guest spot some six months earlier.

Tarantino’s film treats this little bit of pop culture ephemera as an uncanny coincidence. It simply becomes yet another way that he can intertwine the destinies of his three protagonists. But that brief shot got me thinking: did Tarantino start with the idea that he’d recreate whatever series was featured on TV Guide the week Tate was killed?

If so, Rick might have appeared just as easily as an aspiring cartoonist next to William Windom on the NBC sitcom, My World and Welcome to It. The show debuted just six weeks after Tate’s death. It is not unthinkable that NBC would have pushed for a cover on TV Guide in an effort to promote the premiere. Yet Tarantino’s counterfactual history in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood would have been vastly different if that had been the case.

Did Tarantino really base his screenplay on this conceit? I doubt it. Lancer fits so snugly into the world that the director captures onscreen that it is not be so easily replaced. Tarantino seems to have a nostalgic fondness for the show, much as I did in my wasted youth. (I recall having a Lancer lunchbox at age six.) Production designer Barbara Ling describes the steps she took to recreate Lancer’s mix of Spanish/Western design. This involved adding adobe storefronts to the wooden ones, and substituting iron coils for wooden pegs on the saloon’s staircase. Ling added, “This was a [rich] cattle town and the buildings are two and three stories. It’s not Deadwood.”

Many critics have characterized Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood as another hangout movie. This is Tarantino’s designation for a film that is leisurely paced, fairly light on plot, and mostly gives the audience a chance to spend time with the characters. Indeed, because of these qualities, reviewers often compare Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood to Jackie Brown, a film that Tarantino himself compared to Rio Bravo, which was Howard Hawks’ hangout movie.

The resemblances don’t stop there. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s three-headed protagonist bears certain similarities to Jackie Brown’s Jackie, Ordell, and Max.

Yet while watching Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, I felt this film, more than any of Tarantino’s others, was an exercise in world-building. Normally we associate that term with sci-fi, fantasy, and comic book movies. It is especially important for transmedia properties where the fictional universe depicted exceeds the bounds of any individual film, television series, book, or video game.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is also an alternate history, a type of speculative fiction also common in sci-fi and comic book stories. The Avengers: End Game and Spider-man: Into the Spiderverse are both relatively recent examples. This suggests a loose affiliation between Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood and other blockbusters even as Tarantino tweaks that formula by situating his speculative fiction within the generic framework of true crime.

Tarantino largely avoids the industrial motivations behind these two narrative techniques commonly seen in tentpoles. Instead, he simply recreates the pop culture world of his youth. In doing so, the director’s real world, his “realer than real” universe, and his “movie movie” universe all collide.

Keepin’ it real (and realer)

As Tarantino has explained in interviews, the “realer than real” universe is an alternate reality close to our own where his fictional characters can intermingle with real people. The “movie movie” universe, on the other hand, is a more overtly fantastic world closer in spirit to comic books or exploitation films. The characters have unusual abilities or even supernatural powers. The “movie movie” thus downplays the realistic motivations usually found in the “realer than real.” In Tarantino’s oeuvre, Reservoir Dogs and True Romance exemplify the “realer than real.” Kill Bill and From Dusk to Dawn are instances of the “movie movie.”

Each universe features a web of connections that can link particular tales together. For example, Kill Bill’s Sheriff Earl McGraw and his son Edgar pop up in Death Proof. Similarly, Lee Donowitz, the cocaine-sniffing movie producer in True Romance, is purportedly the son of Sgt. Donny Donowitz, the “bear Jew” in Inglourious Basterds.

In Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, the most obvious references to these two Tarantino universes are the fictional brands he has created. During the end credits, we see Rick in a TV ad for Red Apple cigarettes. According to a Tarantino wiki, “ads or packs of these flavorful smokes” can be seen in The Hateful Eight, Inglourious Basterds, Planet Terror, Kill Bill, Pulp Fiction, From Dusk till Dawn, Four Rooms and Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion. (The latter is an obvious outlier. Yet the Red Apple nod was likely an in-joke related to Tarantino’s offscreen romance with Mira Sorvino, who played Romy.)

Similarly, Tarantino’s fictional fast food chain, Big Kahuna Burger, appears on a bus billboard in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood. It previously was featured in a memorable scene in Pulp Fiction. (“That’s a tasty burger!”) But it had already debuted as a delicious snack devoured by Mr. Blonde in Reservoir Dogs. Big Kahuna later comes back in two other Tarantino films, From Dusk Till Dawn and Four Rooms, as well as Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion.

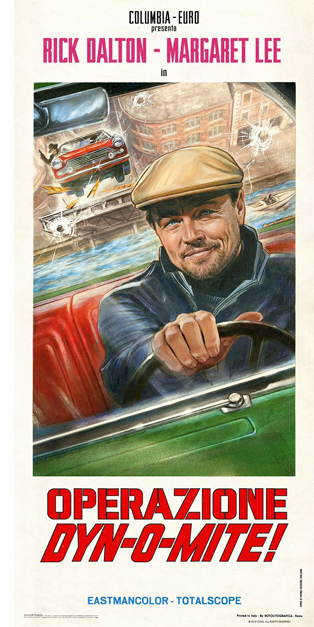

Other references to the “realer than real” are more arcane. In a montage sequence where Randy the Stuntman summarizes Rick’s experience starring in Italian films, we see a poster for Operazione Dy-no-mite, a James Bond knockoff directed by Antonio Margheriti. Fans of Inglourious Basterds will recognize “Antonio Margheriti” as the alias Donny Donowitz uses for the premiere of Nation’s Pride.

Other references to the “realer than real” are more arcane. In a montage sequence where Randy the Stuntman summarizes Rick’s experience starring in Italian films, we see a poster for Operazione Dy-no-mite, a James Bond knockoff directed by Antonio Margheriti. Fans of Inglourious Basterds will recognize “Antonio Margheriti” as the alias Donny Donowitz uses for the premiere of Nation’s Pride.

Much of the fun of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood comes from the way Tarantino overlays these three universes to create a singular fictional world. For example, at one point we learn that Rick was considered for the role of Captain Virgil Hilts, the part played by Steve McQueen in John Sturges’ The Great Escape. Tarantino even inserts digitally altered footage of The Great Escape to show us a scene of Rick as Hilts. Since Rick claims he never met Sturges, this moment appears to represent an imagined version of the film that could exist in some type of alternate history. It invites us to consider how different Rick’s career might have been had fortune smiled upon him instead of McQueen.

To disentangle this knot, one must surmise that The Great Escape and Steve McQueen belong to both the real world and the “realer than real” world. Yet the scene of McQueen at the Playboy mansion and Rick describing his missed opportunity can only belong to the “realer than real.” And the character of Hilts himself exists only in the “movie movie” world. Hilts shares this status along with other characters Rick plays onscreen, such as Bounty Law’s Jake Cahill and The FBI’s Michael Murtaugh. After all, movie magic enables Cliff Booth to stand-in for Rick for scenes involving physical action. That two actors can play the same character within the same scene suggests that fictional personae in cinema have a unique ontological status quite different from the real world.

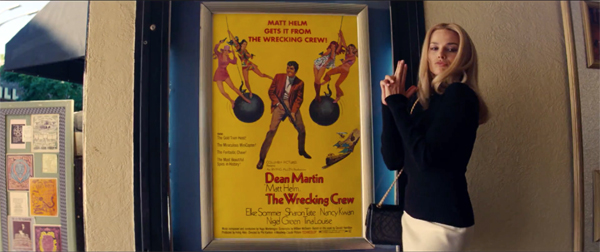

Arguably, the scene where Sharon Tate watches herself in The Wrecking Crew raises even more vexing issues about what is real and what is fictional. Unlike the clip from The Great Escape, the theatre screening shows the real Sharon Tate playing the character Freya in The Wrecking Crew. The fictional Sharon Tate watches the real Sharon Tate, along with the rest of the Bruin Theater’s audience. Yet, because Margot Robbie only pretends to be Sharon Tate for Tarantino’s camera, she doesn’t really watch herself playing the role. Obviously, Robbie belongs only to the real world. Yet Sharon Tate, as both an actual person and a fictional character, inhabits both the real world and the “realer than real world.”

Here the film indulges the Bazinian conceit that cinema has indexical properties. While making The Wrecking Crew, the film camera captured an imprint of the real Sharon Tate that preserved her being beyond the reaches of time and even death. In Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, this moment is both joyful and sad. The viewer imagines the thrill that Tate feels in watching herself on the big screen, basking in the glow of incipient stardom. Yet the delight we experience is colored by our knowledge of what happened to the Sharon Tate seen falling on Dean Martin’s camera case. Unlike Robbie’s character, that Tate is doomed to a grisly death at the hands of psychopaths.

By film’s end, however, we are forced to reevaluate where Sharon Tate fits into Tarantino’s universe. When Cliff and Rick thwart the attack of Tex Watson, Susan “Sadie” Atkins, and Patricia “Katie” Krenwinkel, both Sharon Tates appear to move solely to the realm of the “realer than real.” Like the fictional Sharon Tate played by Robbie, the actress who appeared in The Wrecking Crew also lives on in a parallel universe created by the forking of time. And the fate of that character remains completely undetermined. Now fully a part of the “realer than real,” Tarantino’s Sharon Tate might eventually snort cocaine with movie producer Lee Donowitz or bum a Red Apple cigarette from Pulp Fiction’s Mia Wallace.

Once she joins the “realer than real,” almost any fate you could imagine for Sharon Tate seems possible. And it is that sense of the actress’ unlimited horizons that gives the ending of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood its resonance. Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time films always situated viewers in the realm of myth. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, on the other hand, evokes the fairy tale.

Tarantino is known for his experimentation with narrative, and the simplicity of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s “what-if” scenario could seem like a retreat from the formal play seen in his earlier films. Yet I’d argue that Tarantino’s merging of fact and fiction is even more audacious in certain respects. It strikes me as an unconventional example of what David calls “multiple draft narratives,” like Krzystof Kieslowski’s Blind Chance or Peter Howitt’s Sliding Doors. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood gives us a second draft of history, albeit one where the key decision point is saved almost until the end of the film. And unlike Blind Chance or Sliding Doors, Tarantino doesn’t need to tell us what the different outcomes are for each of these tales. The first draft of history is one we already know.

In fact, the notion of multiple drafts offers a useful lens for all three films in Tarantino’s “counterfactual” trilogy. (The other two are Inglourious Basterds and Django Unchained.) In Groundhog Day, Source Code, and Edge of Tomorrow, each iteration of the basic situation shows the protagonist inching toward his goals. They gradually progress to the point where they are able to alter destiny, either theirs or the world’s or both.

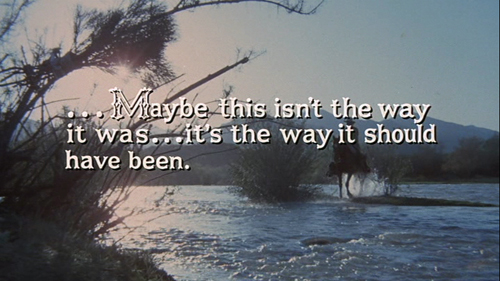

Inglourious Basterds, Django Unchained, and Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood all present images of history not as it was, but as it should have been. Such counterfactual histories run counter to the norms of speculative fictions that often present us with dystopian worlds we were lucky to avoid. (Think Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, Robert Harris’ Fatherland, or Kevin Willmott’s “mockumentary” C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America.) All of these stories depend upon our knowledge of the first draft of history. Yet Tarantino gives us second drafts that right particular historical wrongs in either small or large measure. In doing so, Tarantino gives us versions of history that are closer in spirit to his favorite movies. All three films in the “counterfactual” trilogy feature tidy resolutions. Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, however, is even more self-conscious about the way Tarantino’s second draft of history takes the form of a “movie movie” climax. The realer-than-real version is the one we ought to prefer.

Paging Mr. Melcher, Mr. Terry Melcher…

If Tarantino’s conflation of fact and fiction evokes certain traits of the multiple-draft narrative, his vivid recreation of Hollywood circa 1969 illustrates another type of story popularized in American independent films and various art cinemas: the network narrative.

Tarantino has broached this form before in Inglourious Basterds. There he moves back and forth between three mostly independent storylines: 1) the Basterds’ guerrilla campaign against German soldiers, 2) Archie Hicox and Bridget von Hammersmarck’s initiation of Operation Kino, and 3) Shosanna’s plan to avenge her family’s deaths during the premiere of Nation’s Pride. SS officer Colonel Hans Landa threads through all three storylines. He orders the killing of Shosanna’s family in the opening scene. Later he shares apple streudel with Shosanna in a Paris café. Landa also investigates the scene where Hicox has been killed. In the climax, he interrogates Bridget in a scene that contains a grim allusion to Cinderella’s lost slipper.

Finally, Landa negotiates a deal with Aldo Raine’s superiors that guarantees his immunity from prosecution for war crimes.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is obviously much less plot-driven than Inglourious Basterds. Yet, as noted above, it shares a similarity in the way it interweaves the stories of three characters: Rick, Cliff, and Sharon.

It’s frequently said that Hollywood is a company town. By situating all three characters within the film and television industries, Tarantino tacitly stays faithful to that truism. The protagonists’ shared profession also facilitates the kinds of attenuated links between stories commonly found in network narratives.

Part of the fun of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood comes in recognizing the “six degrees of separation” that join all of these people, both real and fictional, in the same entertainment ecosphere. Take, for instance, one decidedly minor character: actress and singer Connie Stevens, played by Dreama Walker. At the Playboy Mansion party, Stevens listens to Steve McQueen explain the romantic triangle that has Sharon living with her current husband, Roman Polanski, and her ex-boyfriend, Jay Sebring. Stevens, though, is the ex-wife of actor James Stacy, who played Johnny Madrid in Lancer. Stacy (played in our film by Timothy Olyphant) is Rick Dalton’s scene partner for the episode of Lancer that Dalton hopes can spur his comeback. Dalton is Sharon Tate’s neighbor on Cielo Drive, the same house that Charles Manson targets as the site of the “family’s” first murder. This circuit even loops back on itself. When Stacy and Dalton first meet on set, Stacy asks Rick whether it was true that he almost got a part in The Great Escape, the same part played by McQueen.

Two characters in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood serve as nodes that connect all three storylines together. The first is Cliff, Rick’s stunt man and gofer. Although not a resident at Cielo Drive, he spends a lot of time in Rick’s home and thus is privy to what happens in Sharon’s abode. This is especially evident when Cliff repairs Rick’s fallen TV antenna. The camera is aligned with him as he overhears Sharon playing a Paul Revere and the Raiders album. He also notices Charles Manson approaching the Polanski residence. Tarantino’s casting of Damon Herriman as Manson is likely an allusion to the television show, Justified. Herriman played Dewey Crowe alongside Olyphant.

Justified was also an adaptation of Elmore Leonard’s “Raylan Givens” books. Tarantino has long admired Leonard’s work as a writer of both westerns and crime novels.

Employing a redundancy that befits Hollywood storytelling, Cliff gets linked to Sharon’s storyline in other ways. While working as Rick’s stunt man for an episode of The Green Hornet, he gets involved in a dust-up with Bruce Lee. Lee gave Sharon Tate some pointers on fighting as she prepared for her role in The Wrecking Crew. And in real life, the martial arts legend was recommended for the role of Kato on television’s The Green Hornet by Sebring, Tate’s former boyfriend.

Perhaps Cliff’s most important role in the film’s network involves his dalliance with Pussycat, one of the many young women who viewed Manson as a kind of guru. Cliff picks up Pussycat as a hitchhiker and gives her a ride back to the Spahn ranch. Having worked on the ranch back when it was an active production site, Cliff grows concerned for the safety of its owner, George Spahn. Cliff notices how the Manson clan has taken over and is troubled by its weird vibe. Determined to see George for himself, Cliff forces his way into George’s house over the objections of the Manson girls, especially Squeaky. George seems careworn, but Cliff finds that there is little he can do for him.

When Cliff sees a pocketknife sticking out of his front tire, he confronts Clem, one of Manson’s followers. The conflict becomes physical. Cliff breaks Clem’s nose with one punch and then proceeds to beat him to a bloody pulp.

This proves to be a dangling cause that gets resolved in the film’s climax when Cliff recognizes Tex, Sadie, and Katie as people he met at the Spahn ranch.

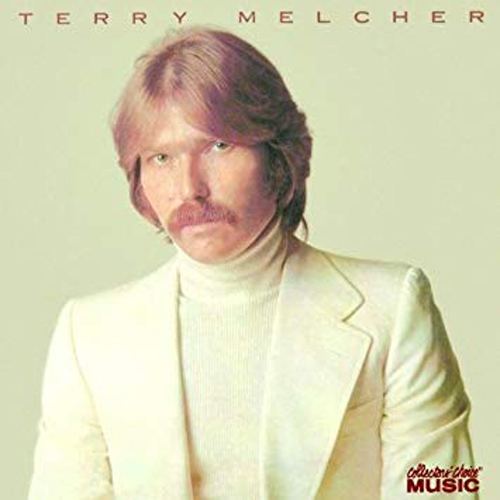

The other character who links the storylines together is one we never see: record producer Terry Melcher. Melcher is the “Terry” that Manson mentions when he visits Cielo Drive in the scene described above. Later, Tex reminds Sadie, Katie, and Linda that Charlie directed them to go to the place where Terry Melcher lived and kill everyone inside.

Although these are the only explicit references to Melcher, he is indirectly represented in several other aspects of the film. Here it helps to know a little about Melcher’s career and Manson lore. Even if Melcher’s name draws a blank, you likely know many of the bands he worked with: the Byrds, the Mamas and the Papas, and Paul Revere and the Raiders.

All these musicians crop up in one way or another in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood. Melcher’s last major credit of the 1960s was as producer of the Byrds’ Ballad of Easy Rider. When Rick berates Tex for parking his car on Cielo Drive, he yells, “Hey, Dennis Hopper! Move this fucking piece of shit!” Rick’s insult fits with his general disdain for hippies. But it also alludes to Easy Rider by comparing Tex’s look to that of Hopper’s character, Billy.

Two of the Mamas and the Papas – Michelle Phillips and Cass Elliot – both appear in the party scene at the Playboy mansion.

We also hear the Mama and the Papas’ big hit, “California Dreaming” in a cover version by Puerto Rican singer José Feliciano. And when the car driven by Tex crawls up Cielo Drive, the music issuing from the Polanski residence is the Mamas and the Papas’ “12:30: Young Girls are Coming to the Canyon.” Even before Tex’s directive to the Manson girls, Tarantino has given us a subtle reminder that Melcher was Charlie’s intended, if indirect, target.

Finally, Sharon plays Paul Revere and the Raiders’ “Good Thing” and “Hungry” on a hi-fi in her bedroom.

The choice of music is especially fitting since the band’s lead singer, Mark Lindsay, lived in the same house on Cielo Drive with Melcher and his then girlfriend, Candice Bergen.

Beyond these musical references, Melcher’s history with Manson informs Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood in another way. Melcher recorded some demos of Manson’s songs, and even discussed making a documentary about Manson’s commune at the Spahn Ranch. In testimony at trial, Melcher said that any possibility of a record contract with Manson was sundered when Charlie asserted that he’d never join a musicians’ union. Manson’s staunch refusal was rooted in his desire to avoid entanglements with the establishment. Yet union membership was a condition for any contract with Melcher’s label, Columbia records. Another factor in Melcher’s decision was his assessment of Manson’s talent. Charlie couldn’t sing.

Although Melcher publicly stated that he only considered Manson’s musicianship, he privately expressed concerns about Charlie’s mental stability. These were heightened when he visited the Spahn Ranch and witnessed Manson in a physical altercation with a drunken stunt man. Tarantino more or less recreates this episode in his film, substituting Cliff for the unnamed stunt man and the hapless Clem for Charles Manson.

More importantly, Melcher is the son of screen legend Doris Day and stepson of agent/manager/producer Martin Melcher. In Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, he becomes the ideal, if absent, symbol of the combined worlds of music, television, and film that Tarantino so lovingly details.

How the West was lost

Los Angeles circa 1969 is presented as the epicenter of the American entertainment industries. It’s a place where a hairdresser like Jay Sebring rubs shoulders with action stars, TV cowboys, ingénues, film directors, and pop stars –and make $1000 a day to boot! The constant stream of hits from KHJ radio is as ubiquitous as the many movie posters, billboards, and theater marquees that feature Hollywood’s latest and greatest.

Tarantino’s press kit for Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood makes reference to Joan Didion’s famous observation in “The White Album” that “the Sixties ended abruptly on August 9, 1969, at the exact moment when word of the murders on Cielo Drive traveled like brushfire through the community.” Most critics take Didion’s reference to the Sixties as shorthand for the end of the “peace and love generation.” Yet Tarantino’s slightly revisionist take suggests it’s not only the youthquake that died, but also a certain strain of Hollywood filmmaking that passed with it.

Although I don’t doubt their historical accuracy, the litany of titles that appear throughout Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood feels as curated as any of Tarantino’s music soundtracks. Some, like 2001: A Space Odyssey, are films that entered the canon of great sixties cinema. Others, like The Night They Raided Minsky’s, are early films by directors who’d later achieve greatness. (In this case, William Friedkin, who won an Oscar in 1972 for The French Connection.)

But many, like Lady in Cement, Tora, Tora, Tora!, Krakatoa: East of Java, Mackenna’s Gold, C.C.& Company, and even The Wrecking Crew, are largely forgettable movies.

Tarantino clearly has affection for all of the drive-in theaters and Hollywood picture palaces where these titles played. But the titles themselves are evidence of the industry’s struggle to adapt to new tastes and a rapidly changing media landscape. Old-school show biz types, like Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra, continued their success as singers and television personalities. But their careers as actors had functionally ended by 1969. And the efforts to keep them relevant often seemed either strikingly anachronistic or just plain weird.

In the opening scene of Lady in Cement, Frank Sinatra fights off a small school of sharks while he is examining the body of a nude woman who, like Luca Brazzi, sleeps with the fishes. And yes, the scene is as ludicrous as it sounds. If this is what became of Hollywood’s once great tradition, it is hard not to think we should just let it pass.

Yet, the fear of obsolescence also explains the oversize role that Tarantino gives to the Western as part of this changing landscape. True Grit and The Wild Bunch were among the summer of 1969’s biggest hits. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid would eventually become the year’s top-grossing film. All three Westerns feature cowboy heroes that are either aging, outmoded, or both. They reminded contemporary viewers that horse riders would soon yield to horseless carriages, the lone bounty hunter would soon be supplanted by paramilitary detective agencies, and the humble six-shooter can’t match the lethal power of a Mexican army machine gun.

In retrospect, though, the popularity of the Western in 1969 represents the genre’s last gasp. Studios continued to make Westerns during the 1970s, but only three – Jeremiah Johnson, The Outlaw Josey Wales, and The Electric Horseman – would surpass $10 million in rentals in the entire decade.

On television, such long-running series as Gunsmoke, Bonanza, and The Virginian had their last round-ups. The networks tried their hands at new Westerns, like Alias Smith and Jones (below), Hec Ramsey, Dirty Sally, and Lancer, but they were all short-lived. At the start of the 1980s, the genre was completely moribund. Subsequent efforts to recapture the Western’s former glory were mostly the equivalent of flogging a dead pony.

As a total cinephile, Tarantino is entirely aware of this aspect of the genre’s history. This is signaled quite explicitly in the decrepit condition of the Spahn Movie Ranch. Yet Tarantino also uses Rick’s career arc to signify its downward trajectory.

No character in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood is as strongly associated with the Western as Rick. His home is filled with collectibles like his Hopalong Cassidy coffee mugs. His walls are decorated with posters for The Golden Stallion and A Time for Killing. On set, he reads pulp oaters like Ride a Wild Bronc to relax between takes.

By using Rick to dramatize the twin declines of both Old Hollywood and its “bread and butter” genre, the narrative arc of Tarantino’s drugstore cowboy is one suffused with nostalgic melancholy. The key moment in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood occurs when Rick breaks down telling the story of Easy Breezy to Trudi Fraser, his Lancer co-star. He describes Easy “coming to terms with what it’s like to feel slightly more useless each day.”

The various threads of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s network finally knot together in the Manson family’s attack on Cielo Drive. At the moment of truth, it is telling that Rick reaches not for a firearm, but for the prop flamethrower he wielded in The 14 Fists of McCluskey. By recalling the moment when Rick shouts, “Anyone here order fried sauerkraut?”, Tarantino reminds us that violent spectacle and snappy quips will eventually replace the Western’s ritualistic showdowns.

Still, it is a musical allusion to the Western that gives Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood its final grace note. Cliff and Rick have thwarted the Manson family’s attack. The ambulance takes Cliff to the hospital. Rick offers an explanation of what just happened to his neighbors. Jay recognizes Rick as television’s Jake Cahill. Via the intercom, Sharon invites him to come up for a drink. As Rick walks to the house, we hear the start of Maurice Jarre’s “Lily Langtry” [sic] from his score for The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean.

John Huston’s film begins with an expository title shown below that highlights the western’s tendency toward self-mythology. It is especially apt for Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s counterfactual history.

Jarre’s cue, though, appears in a scene where the renowned actress Lillie Langtry finally visits Judge Bean’s Texas town. Langtry is given a tour of the Bean’s house, now converted into a museum that also acts as a shrine to her. Bean worshipped Langtry, but tragically dies before he gets to meet her. Tarantino inverts both Huston’s sad ending and its dramatization of missed opportunity. By altering the course of history, the cowboy in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood gets to be the real-life hero rather than the TV heavy. Rick also gets to meet the actress he’s admired from afar. Rick and Sharon are still both married to other people. But their chance meeting in the film’s epilogue feels more than anything like a dream fulfilled.

A star is unborn

In the previous section, I dwelt on the role of the Western in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood because of its symbolic significance in capturing a particular historical moment. But Tarantino borrows quite freely from another narrative prototype: the show-biz tale. In fact, while walking out of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, I wondered aloud if it was Tarantino’s twisted take on A Star is Born.

Like A Star is Born, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood centers on a male performer whose career has started to decline and a female newcomer whose star is on the rise. Moreover, Rick’s drinking problems create an obstacle to his comeback in much the same way that alcohol contributes to the downfall of the male protagonists in all four versions of A Star is Born.

Tarantino, though, subtly alters this template in two ways. First, he depicts his two stars as neighbors rather than as a romantic couple. Secondly, he cleverly depicts Rick’s career arc as an inverse mirror of Sharon’s.

Tate was an Army brat who grew up in Europe. Her earliest work was as an extra in Italian films. She moved to Hollywood in 1962 and got her break playing Jethro Bodine’s girlfriend on The Beverly Hillbillies. In the mid-sixties, Tate made the move to films, appearing in Eye of the Devil and The Fearless Vampire Killers.

It was during production of the latter that Tate met her future husband, Roman Polanski. Tate’s role in Valley of the Dolls further enhanced her status as an “up and comer.” In 1968, Tate earned a Golden Globe nomination in the category of “Most Promising Newcomer — Female.”

In direct contrast, Rick’s career begins in Hollywood and ends in Italy. Rick enjoys early success with Bounty Law and The 14 Fists of McCluskey. But soon finds himself reduced to guest star roles on television. Against his better judgment, Rick agrees to star in four Italian quickies. Two of these are spaghetti westerns directed by Sergio Corbucci, a Tarantino fave who created the popular “Django” character. Rick returns to Hollywood but his future is uncertain. He could be the next Clint Eastwood, star of A Fistful of Dollars and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Or he could be the next Richard Harrison, star of $100,000 Dollars for Ringo and Secret Agent Fireball.

If this were all there was to the comparison, it would hardly be worth mentioning. But Tarantino hints at other parallels through a much more obscure and convoluted cinematic reference. An auteur as shrewd as Tarantino would undoubtedly remember that the Rolling Stones’ “Out of Time” –used in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood under shots of Rick’s return from Rome – was previously featured in the opening sequence of Hal Ashby’s Coming Home.

The connection to Ashby’s film is strengthened by the casting of Bruce Dern as George Spahn, a role originally intended for Burt Reynolds. Early in his career Dern played Jane Fonda’s uptight, martinet husband in Coming Home. More importantly, during Coming Home’s climax, Dern’s character commits suicide by wading into the ocean to drown himself, just as James Mason does at the conclusion of George Cukor’s version of A Star is Born.

Which brings us back to Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s controversial ending. Earlier I discussed the resemblance between its counterfactual history and multiple draft narratives. Here I want to discuss it as an illustration of the caprice of fame.

Much more than the endings of Inglourious Basterds and Django Unchained, the climax of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood feels both resolved and unresolved. Hitler’s violent death in Inglourious Basterds surprised audiences who first saw it in theaters. Yet the historical record indicates that the Basterds simply saved Hitler the trouble of later killing himself and his wife, Eva Braun. At the conclusion of Django Unchained, the protagonist’s revolt clearly hasn’t ended slavery as a “peculiar institution.” But its story of personal revenge remains deeply satisfying.

The ending of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood left me with more questions than answers. I get it. Sharon Tate lives instead dying at the hands of the Manson family. Tarantino gives us the Hollywood happy ending that this story lacked in reality. But what’s next?

Do the deaths of Tex, Sadie, and Katie mean that Leno and Rosemary LaBianca also survive? Maybe. Perhaps the loss of three members of the cult might cause the others to reevaluate their loyalty to Manson. Perhaps Manson himself would reevaluate his plan to trigger a race war.

But maybe not. If Manson were the hero of Tarantino’s grindhouse climax rather than its villain, one could easily imagine the film running another twenty minutes with Manson vowing to get even. You might imagine it as something like the surprising “second climax” of Django Unchained. After mourning the loss of his compatriots, Charlie would proclaim. “The fires of Hell will descend upon the Hollywood hills. This time it’s personal.”

Perhaps the bigger question is whether Sharon continues to be the “It” girl during the next phase of her career. The allusions to A Star is Born suggest a steady upward trajectory. But the reality is that success depends upon a certain amount of luck. It is never assured. A few box office bombs and Sharon Tate might be reduced to the same sort of TV guest spots that Rick is doing.

In this way, the ending of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood asks us to consider a potential paradox. Did Sharon Tate become more famous in death than she ever would have been in life?

The theme of talent tragically cut down in the prime of life is a hoary cliché of the celebrity biopic. Tarantino is smart to steer clear of it. Yet whenever we watch a film like Prefontaine, Beyond the Sea, or Lenny, one starts to wonder, “Would anyone bother to make this film if its subject had lived?”

To be sure, the totality of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood shuns any pat answer. Cass Elliot of the Mamas and the Papas died at age 32. Initial reports said she choked on a ham sandwich in the midst of having a heart attack. I remember the media reports when Mama Cass passed in 1974. But does anyone who didn’t live through that moment?

James Stacy, star of Lancer, nearly died in a deadly motorcycle accident. (Tarantino hints at this fate by showing Stacy, sans helmet, riding his steel horse away from his trailer.) Stacy survived, but lost an arm and a leg as a result of his near fatal injuries. He eventually made a comeback in 1977 and even earned an Emmy nomination for his work on Cagney and Lacey.

Yet, if you mention James Stacy during dinner conversation tonight, I suspect your companion will ask, “Who?”

And then there is the scene where Pussycat and the other Manson girls walk past a large mural of James Dean in his iconic pose from Giant. Dean was certainly famous during his lifetime. But he became a legend at age 24 after his Porsche Spyder collided with another car, snapping his neck.

Would Sharon Tate have achieved stardom had she lived? God only knows. I certainly don’t. I do know one thing, though. Being a victim of the “crime of the century” preserved Tate’s image in popular memory with a vividness that very few human beings on this earth ever achieve.

Margot Robbie’s performance as Tate is extraordinary. She reminds modern viewers of the verve, spirit, and sensuality that Sharon brought to the screen. Yet it is the image of Tate as a tragically murdered heroine that Tarantino, like Mark Macpherson in Laura, appears to have fallen in love with. And it is this image that continues to haunt me some fifty years after Tate’s death.

Thank you to David and Kristin for their comments onf an earlier draft of this post. Thanks also to JJ Bersch and Maureen Rogers for letting me bounce some of ideas off them.

Vincent Bugliosi’s Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders remains the most comprehensive account of the Tate-LaBianca murders. Tom O’Neill, though, has spent the last 20 years investigating Manson’s crimes. His new book, Chaos: Charles Manson, the C.I.A., and the Secret History of the Sixties, claims that Bugliosi’s investigation was deeply flawed. Instead, his research suggests that Manson was a drug trafficker and C.I.A. operative. For O’Neill, the notion that Bugiliosi saved Los Angeles from a hippie death cult is wrong. The motive for the crimes was both simpler and more quotidian. All of Manson’s murders were the result of drug deals gone wrong. An interview with O’Neill can be found here.

The story that Terry Melcher witnessed a fight at the Span Movie Ranch between Charles Manson and a drunken stunt man sounds apocryphal. Yet it appeared in The Telegraph’s obituary for Melcher, which was first published in 2004. I haven’t been able to independently corroborate that story with another source. However, even if it isn’t true, it is part of Manson lore. I saw the same story repeated on at least three other websites. Doris Day’s death in May spawned the publication of a handful of articles about her relationship with Terry. They can be found here, here, and here. An brief overview of Melcher’s career as a record producer can be found in Rolling Stone’s obituary.

For those interested in learning more about Sharon Tate’s life, I recommend Sharon Tate: Recollection. It was written by Tate’s mother Debra. It also features a foreword by her husband, Roman Polanski.

Mark Harris’s Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood and Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls survey the momentous changes taking place in the film industry during the late 1960s.

Bruce Fretts provides a fairly thorough overview of Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood’s voluminous pop culture references.