Archive for the 'Film technique: Sound' Category

LA LA LAND: Singin’ in the sun

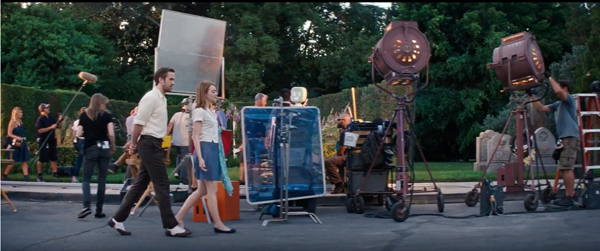

La La Land (2016).

DB here:

In our Film Studies program at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, one of our aims is to integrate critical analysis of movies with a study of film history. Sometimes that means researching how conditions in the film industry shape and are shaped by the creative choices made by filmmakers. We also study how filmmakers draw on artistic norms, old or recent, in making new films. This effort to put films into wider historical contexts is something that you don’t get in your usual movie review.

Take, yet again, La La Land. Awards and critical debates continue to swirl around the surprising success of this neo-musical. Two entries on this blog have already considered what the film owes to 1940s innovations in Hollywood storytelling (here) and to more basic norms of movie plot construction and the classic Broadway “song plot” (here). But there’s plenty more to say.

Enter three Madison researchers as guest bloggers. Kelley Conway is an authority on the French musical from the 1930s to the present and author of an excellent book on Agnès Varda (reviewed here). She also gave us an earlier entry on films at the Vancouver Film Festival. Today, in an oblique rebuttal to some complaints about the principals’ singing and dancing in La La Land, she situates Damien Chazelle’s film within a trend toward “unprofessional” musical performance.

Eric Dienstfrey studies developments in acoustic technology and how those have affected the way movies sound. In his contribution, he traces how film’s recording methods shape the auditory texture of the numbers, with special attention to the soft boundary between diegetic (story-world) sound and non-diegetic sound.

Amanda McQueen is a specialist in Hollywood and TV musicals of the last fifty years. Here she considers how La La Land is designed to overcome audiences’ current resistance to “integrated” musicals. She proposes that it offers one way to revive the genre for modern Hollywood.

These experts take the conversation in new directions I think you’ll enjoy. They remind us that a movie coming out today automatically becomes a part of history; it’s just that the history is sometimes hard to discern. Along the way they show the virtues of thinking beyond the talking points put out by the PR machine or circulating endlessly in reviews. In my view, good film criticism involves ideas and information as well as opinions, and all three are on vivid display here.

Amateurism as authenticity

Everyone Says I Love You (Woody Allen, 1998).

Kelley Conway: For me, La La Land‘s references to classical Hollywood musicals and to the films of Jacques Demy provide a major source of its pleasure. (Sara Preciado’s video essay demonstrates the film’s homages) The film’s nods to other traditions remind us of something about the relationship between Hollywood and other national cinemas: mutual influence is the norm.

Directors associated with the French New Wave absorbed and subverted Hollywood genres. Hollywood directors of the late 1960s and ‘70s, in turn, were inspired by the narrative ambiguity and stylistic playfulness of the New Wave. Sometimes, the influence travels full circle in quite a direct way. John Huston’s Asphalt Jungle (1950) directly influenced Jean-Pierre Melville in the making of Bob le flambeur (1956), while Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs references both Melville’s minimalist gangster films and Hollywood heist films.

La La Land demonstrates a similarly rich exchange between Hollywood and France. In 1967, Jacques Demy’s Demoiselles de Rochefort paid loving homage to Hollywood films such as Singin’ in the Rain, West Side Story, and Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Chazelle’s film returns the favor, adopting the dancing pedestrians and location shooting of Demoiselles and the saturated colors, recitative, and downbeat ending of Parapluies de Cherbourg. Chazelle is equally smitten with classical Hollywood; La La Land brims with references to the choreography, costumes, and set design of Shall We Dance (1937), Singin’ in the Rain (1952), The Band Wagon (1953), West Side Story (1961), and many others.

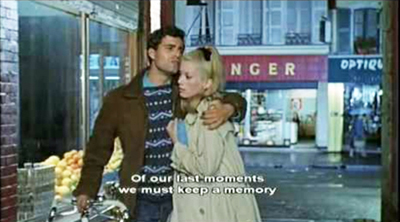

La La Land not only cites the style of other musicals, it also develops and tweaks narrative elements from older musicals in interesting ways. For example, Chazelle’s film, like Demy’s Parapluies de Cherbourg, thwarts the creation of the couple. In Parapluies, the Algerian war initially separates Guy (Nino Castelnuovo) and Geneviève (Catherine Deneuve).

Later, an unplanned pregnancy and her mother’s machinations push Geneviève to marry a wealthy jeweler. At the end of the film, when they run into one another at Guy’s gas station, they exchange only a few perfunctory words; Guy even declines Geneviève’s invitation to meet their daughter. There is neither anger nor the warmth of nostalgia in their exchange; just a delicately drawn emotional distance that leaves viewers feeling wistful.

In contrast, the relationship between Mia and Sebastian fails because they decide to put their romance on hold in order to pursue their dreams. “Where are we?” Mia asks Sebastian after her audition for the film role that will take her to Paris and launch her career. “We’ll just have to wait and see,” he replies. Five years later, he owns a jazz club and she has become an A-list actress, but she is married to someone else and has a child.

When they cross paths at his club, Chazelle supplements Demy’s delicate gas station meet-up with an exuberant fantasy montage, a kind of dream ballet often used in the classical Hollywood musical, in which the couple manages to stay together. The production number is full of invention and energy, combining animation, simulated home movie footage, a trumpet solo, and a tribute to the “Broadway Melody” number of Singin’ in the Rain. As Mia prepares to leave the club, she and Sebastian exchange tender glances and rueful smiles. She departs as he launches into his next song. The love is still there, the film suggests, but Sebastian and Mia chose art over love and they would probably make the same decision today. Different from Demy’s characters, Sebastian and Mia are not victims of implacable destiny, but committed artists. It’s an ending that feels fresh to me.

As Amanda McQueen reveals below, La La Land conforms to various trends in the 21st century musical. Consider just one element: song performance. Neither Ryan Gosling nor Emma Stone possesses a powerful, belt-it-out voice. Instead, much of the singing in La La Land is modest, thin, and breathy. Take, for example, the number “The Fools Who Dream,” a climactic moment in the film.

Asked by the casting director to tell a story, Mia begins a poignant monologue (“My aunt used to live in Paris…”) in a quiet speaking voice marked by a bit of vocal fry. She slowly moves into an a capella ballad and, after a few bars, is accompanied by piano. Eventually, the music swells, Mia goes big (“Here’s to the ones who dream…”), and then the song winds back down to the concluding notes, delivered a capella. The staging of the song – black background, circular camera movement, a big swell of emotion, a long take – is reminiscent of the splashy production number in Agnès Varda’s New Wave masterpiece Cléo de 5 à 7. But Stone’s voice reminds me of the wonderfully whispery, intimate singing voices of Birkin, Bardot, and Karina.

As Eric Dienstfrey points out below, the techniques used in the recording of the songs affect our impression of the story world and our sense of the film’s aesthetic achievement. In a Song Exploder podcast about the creation of this song, composer Justin Hurwitz emphasizes the difficulty of shooting this one-shot production number. He explains that Stone performed the song live on set, as opposed to lip-synching it. Hurwitz speaks of his struggle to keep up with Stone while accompanying her on set:

Because I was letting Emma lead the song, I was reacting to her. So a lot of times the piano is a little bit behind the vocal. It sounded like a recital or something where you know the singer is leading it and the piano is there to accompany. That’s what happens when two people make music together; things are not perfectly in sync. That’s why it feels musical and why it feels real and honest.

Directors of many recent film musicals similarly seek to create the impression of aural and emotional authenticity, either through non-professional singing or on-set recording. Woody Allen’s musical Everyone Says I Love You (1996) employs actors who are not professional singers, and Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge (2001) uses the relatively modest singing talent of Nicole Kidman and Ewan McGregor in a mixture of playback and live recording. Likewise, publicity for Les Misérables (2012) made much of the fact that Anne Hathaway, Hugh Jackman and Russell Crowe performed their songs on the set.

Christophe Honoré also tends to employ singing performances by non-singers. Here, in Dans Paris (2006), a couple breaks up over the phone while singing in a breathy, halting fashion.

For his musical Pas son genre (aka “Not My Type,” 2014), Belgian director Lucas Belvaux cast Emilie Dequenne (of Rosetta fame) as a karaoke-singing hairdresser who woos a philosophy professor. Belvaux insisted that Dequenne avoid taking lessons so as to preserve the imperfect quality of her singing voice. Here, Jennifer (Dequenne) and her pals rehearse the Supremes’ “You Can’t Hurry Love”:

There is, in fact, a broad spectrum of singings styles and capabilities used in contemporary film musicals. In La Captive (2000), Chantal Akerman employs an aria from Mozart’s Così fan tutte. Two women sing to one another flirtatiously from their windows across an apartment courtyard without accompaniment. One woman is a trained opera singer, while the other, the film’s elusive female protagonist (Sylvie Testud), is untutored. The contrast in the women’s voices provides an unexpected pleasure.

The use of the modest singing voice by Chazelle and others to convey emotion and authenticity is quite different, for example, from Alain Resnais’ use of song in On connaît la chanson (aka “Same Old Song,” 1997). Here, fragments of songs spanning the history of twentieth-century popular French chanson are lip-synched by actors. Like Dennis Potter, whose Singing Detective (1986) inspired On connaît la chanson, Resnais foregrounds the artificiality of dubbing. This creative choice works against the traditional commitment in film musicals (and in sound cinema more generally) to the impression of fidelity and authenticity. Here, Josephine Baker’s delicate singing voice is grafted onto the body of a Nazi commander. The humor in non-synchronization loops us right back to Singin’ in the Rain.

Directors of contemporary film musicals did not pioneer the use of the untrained singing voice. As Jeff Smith reminded me recently in an email, “There is a long tradition of celebrating the raw, unpolished singing styles of rock and rollers, dating back at least to the time of Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan and Roger Daltrey, and using those marks of authenticity as a means of distinguishing them from pop performers.” Unlike the musicians of rock and punk, though, Chazelle doesn’t seem particularly interested in denigrating pop music. He clearly loves John Legend’s musical performances in La La Land and those 1980s pop tunes he pretends to mock.

Many have criticized La La Land’s singing, but in fact, Chazelle is operating well within the tradition of employing imperfect vocalization to connote realism and to convey emotional power. The modest singing voices add another dimension to Chazelle’s participation in the ongoing conversation between Hollywood and French cinema.

La La canned vs. La La live

Eric Dienstfrey: I agree with Kelley’s observations about the remarkable number of cinematic references in La La Land. For example, the opening number, “Another Day of Sun,” embeds a host of influences within Chazelle’s mise-en-scène. For me, this exit-ramp romp immediately recalled the ferry ride in Jacques Demy’s Les Demoiselles de Rochefort and the traffic jam in Jean-Luc Godard’s Weekend. Amanda McQueen, below, notes how the scene reminded her of the films of Vincente Minnelli. And as Chazelle himself indicates, one might even see traces of Rouben Mamoulian’s Love Me Tonight and Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window.

Thanks to such references, we can consider the significance of La La Land’s numbers as extending well beyond Justin Hurwitz’s melodies and Benj Pasek’s and Justin Paul’s rhymes. The film’s allusion to Rear Window, for instance, may encourage audiences to compare the onscreen chemistry between Emma Stone and Ryan Gosling to that of Grace Kelly and James Stewart. To catch these subtle references, filmgoers need to pay close attention to the camerawork, the staging, the costumes, and even the choreography. Similarly, we can discover new layers of meaning by analyzing its songs and their sound designs.

How many ways are there for sound technicians to record and mix a musical number? Quite a few, it seems. One basic way is to record the vocal performances live on the set. During the earliest years of talking pictures, this technique often required the presence of an on-set orchestra to provide accompaniment from behind the camera. More recent strategies, however, merely ask singers to wear small earpieces that play pre-recorded accompaniment.

Another option is for technicians to record the vocal performances in an acoustically controlled studio and then mix these recordings into the final film. Sometimes technicians will record the studio performance before filming, and then require actors to lip-synch to playback on the set. Other times, technicians will ask the singers to perform the song live on the set, but then use a studio recording in the final mix due to unforeseen circumstances.

In some instances, the set might be too noisy to record a clean vocal performance, or the dance number might be so physically demanding that the actor can’t help but introduce heavy breathing and other vocalized efforts. A live recording may be ideal, but the studio recording is often the more practical solution.

The musical numbers in La La Land display both recording techniques. Some were recorded live—such as “Fools Who Dream,” which Kelley discusses above—and some were recorded in a separate studio—such as “Another Day of Sun.” Steven Morrow, the film’s sound mixer, suggests that each choice was informed by various practical concerns. The acoustics along the exit ramp, for instance, reportedly made it too difficult to record live singing.

Such concerns even led to strange incidents where a single song would contain a mixture of both live and studio recordings. Morrow notes how “Someone in a Crowd” relies upon Emma Stone’s live recordings, while studio recordings were used for the other actresses. This decision to blend together live and studio recordings can become a storytelling device—say, if the director wants to create a contrast between two or more characters—but for most songs, the choice to use either technique is generally determined by shooting conditions and budgetary considerations.

Still, can the acoustical differences between live and studio recordings function beyond practical filmmaking needs? It is worth noting that both techniques parallel another cinematic binary: diegetic sound and non-diegetic sound. Diegetic sound commonly refers to all the dialogue, effects, and music that emanate from sources within the film’s setting, such as radios and footsteps. Non-diegetic sounds are those added to the story world as a form of commentary, such as a moody orchestral score. As many film scholars rightfully argue (here and here), the diegetic/non-diegetic binary is not perfect, but for the vast majority of films the distinction remains a useful initial categorization for sound’s narrative functions.

Musicals are an exception. In his groundbreaking study of Hollywood musicals, theorist Rick Altman argues that the clean distinction between diegetic and non-diegetic sound breaks down during moments when characters burst into song. Specifically, the interaction between diegetic singing and non-diegetic musical accompaniment lifts characters out of the story world toward fantastic settings. Consider Elvis Presley’s performance of “I Can’t Help Falling in Love with You” from Blue Hawaii.

Presley begins the song while accompanied by a small on-screen music box. But during his performance something interesting happens: the sound of the music box fades into the background while the drums and guitars of a non-diegetic orchestra magically appear. For Altman, this audio substitution is critical to understanding how the musical genre operates:

We have slid away from a backyard barbecue in Hawaii to a realm beyond language, beyond space, beyond time. […] We have reached a ‘place’ of transcendence where time stands still, where contingent concerns are stripped away to reveal the essence of things.” (66)

In other words, this dissolve from the music box to the orchestra tells us that Elvis… well… has left the building. He has transcended the purely diegetic universe of the film’s story-world reality, and has temporarily entered a non-existent space that is supra-diegetic fantasy.

Altman’s observations apply to La La Land as much as they apply to Blue Hawaii. When Mia and Sebastian sing “A Lovely Night” while searching for their cars, the non-diegetic accompaniment fades in and the two characters interact with the music through song and dance. In turn, Mia and Sebastian transcend Los Angeles and enter a supra-diegetic universe. This diegetic boundary crossing is punctuated further by their stroll through Hollywood’s hills, a vantage point which allows Mia and Sebastian to literally look down upon the city as they chart this transcendence.

Yet La La Land is more than just a pastiche of earlier musical traditions. It also demonstrates how different recording techniques can be thematically integrated within the film’s narration. Here we might once again compare the playback of “Another Day of Sun” to the live recording of “Fools Who Dream.” Both numbers are similar in their reliance upon non-diegetic musical accompaniment, yet the production process creates contrasting narrative implications.

“Another Day of Sun” was recorded in a studio, and the acoustical details of this studio environment—namely frequency response, microphone placement, reverberation time, and overall cleanliness of the recording—are remarkably distinct from the those of an outdoor location. These subtle textural differences produce the sense that the performers’ voices have left the diegetic space of the freeway and traveled to an unseen studio for the song’s duration.

“Fools Who Dream” has the opposite effect. It was recorded live, and throughout the scene the acoustical details that shape Stone’s voice never really change. The sonic signature of the room remains audible in her vocals from the time she introduces herself to the casting directors, to the time she finishes singing. As a result, Mia does not transcend the story world; instead, the non-diegetic piano and orchestra seem to materialize inside the room.

These two examples demonstrate how alternative recording techniques offer filmmakers different ways for characters and accompaniment to interact. Studio recordings specifically lift the vocals up toward the space of the non-diegetic accompaniment, whereas live performances can pull traditional musical accompaniment down into the story world. Both techniques defy the norms of realism, yet their production differences render each vocal performance with unique narrative weight. And for La La Land—a musical about two artists who wish to become famous stars while simultaneously remaining pragmatic and down-to-earth—the ways Mia and Sebastian interact with musical accompaniment can reveal if and when the characters are grounded in reality or lost in fantasy.

As criticism surrounding contemporary musicals would suggest, Hollywood routinely favors live performances over other techniques. Live performances are not only valued for being more authentic, they are harder to record and, thus, a more prestigious cinematic accomplishment. This preference for live recordings, however, need not dictate how all musicals are made. A creative integration of both live and studio recordings can open up storytelling possibilities for the sound technicians and directors who wish to innovate within the musical genre.

Yes, I know: it seems unlikely that many filmmakers will play with these acoustical parameters in their movies. Nonetheless, La La Land’s sound design points to the possibility that at least a few musicals will create rewarding experiences not just for visually minded historians, but for audiophiles as well.

A musical without quotation marks

Amanda McQueen: Much of La La Land’s critical reception has focused on its relationship to film musicals of the past. As Kelley, Eric and David have all noted, much of the film’s meaning derives from its citation and revision of film and stage musical traditions. But what’s the status of La La Land as a musical in the 21st century? How does this shape the film’s approach to the genre’s conventions?

The early 2000s witnessed a minor revival of the Hollywood live-action musical, a genre that had been considered box office poison for several decades. But despite the renewed interest in musicals, producers worried that contemporary audiences no longer accepted one of its key conventions: the integrated number.

Integration commonly refers to those moments when characters spontaneously burst into song to express feelings or advance the plot, usually accompanied by sourceless music, as Eric points out above. Not all musicals have integrated numbers, but many critics and scholars assume that integrated musicals constitute the genre’s core. Audiences, however, were assumed to find this particular break with cinematic realism both antiquated and alienating. Moviegoers would suspend disbelief to accept lightsabers, superheroes, and wizards, but someone walking down the street and singing—no way!

Fear of the integrated number has caused many contemporary musical films and television shows to distance themselves from this convention. Some musicals ensure the song-and-dance numbers are otherwise motivated. In Chicago and Nine (2010), all the songs are figments of the characters’ imaginations, while Dreamgirls (2006) transformed the integrated numbers of the Broadway original into diegetic stage performances.

Other musicals, including Enchanted (2007), The Muppets (2011), Annie (2014), and Pitch Perfect 2 (2015) opt for comic reflexivity, using integrated numbers to comment on their very artifice. The campy medieval musical Galavant (ABC 2015-2016) is perhaps the epitome of this technique. The lyrics of the second season’s opening number, for instance, address the series’ unexpected renewal (“Give into the miracle that no one thought we’d get”); the excessive repetition of the theme song in the previous season (“It’s a new season so we won’t be reprising that tune”); and a perceived lack of motivation for musical performance (“There’s still no reason why we bust into song”). The four-minute ensemble song-and-dance concludes with Galavant (Joshua Sasse) commenting with satisfaction, “See, now that was a number!”

Over the years, concern over audience acceptance of the integrated musical seems to have abated, particularly for Broadway adaptations. But it hasn’t disappeared, as La La Land’s critical reception makes evident. Articles on the film have routinely stressed that musicals are “an extinct genre,” that “some moviegoers may, no doubt, feel a little tentative about the genre,” and that musicals are no guarantee at the box office. Manohla Dargis’ review in The New York Times, aptly titled “‘La La Land’ Makes Musicals Matter Again,” discusses this issue at some length. She explains how “For decades, the genre that helped Hollywood’s golden age glitter has sputtered,” reappearing only in Broadway adaptations or diluted (read, non-integrated) forms, and that as a result, “Musicals have been for kids, for knowing winks and nostalgia.”

What perhaps feels so novel about La La Land is its sincere approach to the “old fashioned” integrated musical form. As writer/director Damien Chazelle told Hollywood Reporter:

On the screen, there is this big gap right now that you have to cross to do a musical. At least an earnest musical, where you’re not immediately putting quotation marks on it.

With its opening number, “Another Day of Sun,” La La Land unabashedly announces that this is an integrated musical, and it never qualifies that position. There are no cheeky winks at the camera, no characters asking why they’re singing to each other, and most of the songs function as pure expressions of thoughts and feelings. Mia and Sebastian are real people in a modern city, who just happen to be singing and dancing and falling in love. For Chazelle, “Another Day of Sun” functions as “a warning sign to people in the audience. If people are not going to be comfortable with it, they’ll leave right away.” La La Land thus almost dares audiences to accept and celebrate this unrealistic cinematic convention, and for a 21st century musical, that’s a somewhat rare approach to take.

Yet La La Land has its own methods of rendering the integrated musical acceptable for contemporary audiences. First, there is its obvious nostalgia. La La Land’s visual style—35mm, CinemaScope, long takes and long-shots scaled to choreography—and its many allusions create a critical distance, an awareness that this type of cinema is a relic of another age. It’s not so much a throwback to studio-era musicals as it is a modern version of the auteurist musicals of 1970s New Hollywood (most of which were also resistant to the traditional integrated number). Indeed, La La Land has been compared to Martin Scorsese’s New York, New York (1977) or Francis Ford Coppola’s One From the Heart (1981).

I think it’s also akin to Ken Russell’s The Boy Friend (1971), which has a lighter tone and takes a similar approach to its citations. Russell updates Busby Berkeley’s kaleidoscopic stagings with color and widescreen, and Chazelle updates Vincente Minnelli’s sequence-shots with a Steadicam. Like The Artist (2011), which tutored modern viewers in the conventions of silent cinema, La La Land is an affectionate lesson in a mode of filmmaking that is not likely to return.

Then there’s the ending, in which Mia and Sebastian find success in their artistic pursuits, but only because they have parted romantically. As Kelley explains, La La Land owes its bittersweet ending to Jacques Demy’s Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). This gives the film a melancholy at odds with the studio era Hollywood musicals it so frequently references—films like An American in Paris (1951) and Singin’ in the Rain (1952), in which the couple lives happily ever after. By eschewing the union of its romantic couple, La La Land tempers the artifice of the integrated musical with a more realistic narrative, one that acknowledges that life does not always work out exactly the way we want. Such a conclusion is far more typical of American independent cinema than it is of the classical Hollywood musical.

Significantly, La La Land does give us a traditional happy ending, but through the device of the dream ballet. One of the most overtly stylized conventions of stage and screen musicals, dream ballets generally function to convey character subjectivity, and they allow for especially abstract mise-en-scène. La La Land tackles this generic trope with the same sincerity it displays in its handling of integrated numbers.

Set to a medley of the film’s musical themes, the sequence functions much like that in An American in Paris, arguably the most famous cinematic dream ballet. The sequence recaps the characters’ emotional journey and romantic relationship entirely through dance. Yet while the ballet in Paris shows a stylized version of what has actually occurred, La La Land’s presents an alternative reality where Sebastian and Mia stay together while also achieving their artistic goals. As Owen Gleiberman puts it in Variety, this “the very movie we would have been watching had ‘La La Land’ simply been the delectable old-fashioned musical we think, for an hour or so, it is.” In the end, though, the film affirms that Mia and Sebastian’s happily-ever-after is only a fantasy; when the dream ballet ends, the two part ways.

The first time I saw La La Land, I found myself daring Chazelle to subvert my expectations and use the dream ballet as a device to create a happy ending. Instead of concluding the fantasy sequence with a return to reality, I hoped the dream ballet would function to re-write the narrative. To my mind, turning the imagined world of the dream ballet into the characters’ actuality would have been an interesting twist on how this device usually functions. At the same time, it would have more radically embraced the integrated musical tropes the film otherwise celebrates.

Yet I suspect viewers would have found this ending contrived, and it would have been. La La Land’s critical and commercial success, I think, has depended on it keeping the model of the classical Hollywood integrated musical slightly at arm’s length. The film’s unique combination of nostalgia and realism is clearly resonating with modern audiences, but it’s also in keeping with the larger approach to the integrated musical in the contemporary moment. As long as film musicals are considered risky properties, certain forms of the genre will likely have to be relegated firmly to the past.

Kelley Conway is a Professor in our department and winner of a Distinguished Teaching Award. She has written Chanteuse in the City: The Realist Singer in 1930s French Film (University of California Press), Agnès Varda (University of Illinois Press), and essays on classical and contemporary French film. She is currently at work on a book about postwar French film culture.

Eric Dienstfrey is a doctoral candidate in our department. His dissertation traces how theories of acoustical fidelity shaped stereophonic technology from 1930 to 1959. Eric’s research interests include silent film musicians and the cultural history of dictaphones. He recently received the 2017 Katherine Singer Kovács Essay Award from the Society for Cinema and Media Studies.

Amanda McQueen, a Faculty Assistant in our department, finished her Ph.D. in 2016. Her dissertation is titled “After ‘The Golden Age’: An Industrial History of the Hollywood Musical, 1955-1975.” It examines how the breakup of the studio system helped create several musical cycles, each aimed at a niche audience, and each designed to prolong the genre’s viability in the new marketplace. Apart from studying musicals on stage, screen, and TV, Amanda’s interested in media industries, film technologies, and genre theory and history.

Thanks as well to Jeff Smith for his comments on these entries. Watch for his annual blog entry (first two, here and here) analyzing the Oscar-nominated songs and scores.

La La Land.

Is there a blog in this class? 2016

A Brighter Summer Day (Edward Yang, 1991).

KT here–

Another year has passed, and Observations on Film Art is approaching its tenth anniversary. The blog was never intended as a formal companion to our textbook Film Art: An Introduction. Basically we write about what interests us. Still, many of our entries use concepts from the book, and we hope that teachers and students might find them useful supplements to it.

As each summer approaches its end and teachers compose or revise their syllabi, we offer a rundown, chapter by chapter, of which posts from the past year might be relevant. (For previous entries, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015.) For readers new to the blog, these entries offer a way of navigating through the site.

Chapter 1 Film as Art: Creativity, Technology, and Business

Film projection made the national news in late 2015 when Quentin Tarantino released his new film, The Hateful Eight, on 70mm film. Only 100 theaters in the USA, most of them specially equipped with old, refurbished projectors, could show it that way. We went behind the scenes to see how the theaters coped in THE HATEFUL EIGHT: The boys behind the booth and THE HATEFUL EIGHT: A movie is a really big thing.

This year the studios took tentative steps toward instituting The Screening Room, a system of streaming brand-new theatrical films to people’s homes for $50. Whether or not this service succeeds, it represents one new distribution model that Hollywood is exploring to cope with the increasing delivery of movies via the internet. See Weaponized VOD, at $50 a pop.

Popular film franchises can go on generating new products and influencing other films for years. We examine the lingering impact of The Lord of the Rings thirteen years after the third part was released in Frodo lives! And so do his franchises.

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

In this chapter we put considerable stress on the concept of narration, the methods by which a film conveys story information to the viewer. There is no end to the ways in which narration can be structured. Often one of the characters in a film can to tell us what happened. . . even if that character is dead. This, as we show in Dead Men Talking, is not as rare as one might expect.

The Walk combines narrative and genre in an unusual way. The first part is a romantic comedy, the second a suspense film, and the third a lyrical piece. We suggest why in Talking THE WALK.

The way a film tells its story can vary considerably depending on whether it has a single protagonist, a dual protagonist, or a multiple protagonist (as in The Big Short, bottom). We examine some of the differences in Pick your protagonist(s).

Looking back over our blog as we passed 700 entries early this year, it occurred to us that several entries discussing principles of storytelling could be arranged to create a pretty good class in classical narrative strategy. We made up an imaginary syllabus in Open secrets of classical storytelling: Narrative analysis 101. No tuition charged.

With the very end of the Lord of the Rings/Hobbit franchise–the release of the extended DVD/Blu-ray version of the third Hobbit film–we discuss the strengths of the film and the plot gaps left unfilled in A Hobbit is chubby, but is he pleasingly plump?

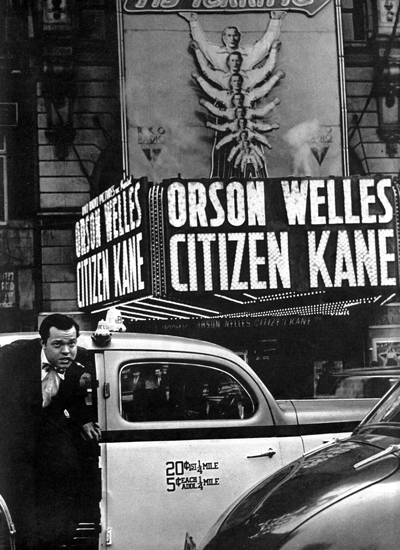

To celebrate Orson Welles’s 101st birthday, we examined some of the sources for some of the techniques used in Citizen Kane, a film we analyze in detail in Chapters 3 and 8. See Welles at 101, KANE at 75 or thereabouts.

In Hollywood it is a common assumption that the protagonist(s) of a film must have a “character arc.” Filmmaker Rory Kelly, who teaches in the Production/Directing Program at UCLA, wrote a guest entry for our site. Rory analyzes the character arc in The Apartment, with examples from Casablanca, Jaws, and About a Boy as supplements. See Rethinking the character arc: A guest post by Rory Kelly.

James Schamus’ Indignation, an adaptation of Philip Roth’s novel, draws on novelistic narrative devices not in the original. In INDIGNATION: Novel into film, novelistic film, we suggest that those devices first became standard in cinema during the 1940s.

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-Scene

Teachers and students always want to us add more about acting to our book. It’s a hard subject to pin down. We introduce the great stage actor Mark Rylance, who was largely unknown outside the United Kingdom before he won an Oscar for Steven Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies, and discuss how he achieves his expressively reserved performances in that film and the series Wolf Hall. See Mark Rylance, man of mystery. (Above at left, on set with Tom Hanks and Spielberg.)

In an era when most staging of actors in movies follows a few simple conventions, we examine the more imaginative ways of playing a scene on display in Elia Kazan’s Panic in the Streets (1950) in Modest virtuosity: A plea to filmmakers young and old.

Continuing with the theme of acting and staging, our friends and colleagues, Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs have put a revised version of their in-depth study of silent-cinema acting online for free. Learn about it and the enhancements that internet publishing has allowed in Picturing performance: THEATRE TO CINEMA comes to the Net.

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

We look at the visual style of Anthony Mann’s Side Street (1949) and show how a simple, seemingly minor technique like a reframing can create a strong reaction in the spectator. See Sometimes a reframing …

Framing a composition is one of the most basic aspects of cinematography. We discuss centered framing, decentered framing, balanced framing, framing in widescreen movies, and particularly framing in Mad Max: Fury Road (above) in Off-center: MAD MAX’s headroom.

In a follow-up entry, we discuss framing in the classic Academy ratio, 4:3, with emphasis on action at the edges of the frame: Off-center 2: This one in the corner pocket.

Chapter 7 Sound in Cinema

For the new edition of Film Art, we had to eliminate our main example of sound technique, Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige. But we put that section of the earlier editions online. THE PRESTIGE, one way or another takes you to it.

For those who have been looking for examples of internal diegetic sound, we take a close look (listen) at a sneaky one in Nightmare Alley: Do we hear what he hears?

The fact that the protagonist narrates The Walk in an impossible situation, standing on the torch of the Statue of Liberty and talking to the camera, bothered a lot of critics. We suggest some justifications for this decision in Talking THE WALK.

We offer brief analyses of the Oscar-nominated music from 2015 films in Oscar’s siren song 2: Jeff Smith on the music nominations.

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

Many different filmic techniques can serve similar functions. Filmmakers of the 1940s had a broad range to choose from when they portrayed dead people, or Afterlifers, on the screen. We look at how their choices affected the impact of the scenes (as in Curse of the Cat People, above) in They see dead people.

Style and form in three films of Terence Davies: Distant Voices, Still Lives; The Long Day Closes; and especially his most recent work, Sunset Song. See Terence Davies: Sunset Songs.

Style and form in Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day, on the occasion of its magnificent release by The Criterion Collection, in A BRIGHTER SUMMER DAY: Yang and his gangs.

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated

Leo Hurwitz’s little-known documentary, Strange Victory (1948) has recently come out on Milestone’s DVD/Blu-ray. Released shortly after the end of World War II, it suggests that the Nazi atrocities were only an extreme instance of the cruelty of racism. We discuss the film and its relevance to the current political situation in Our daily barbarisms: Leo Hurwitz’s STRANGE VICTORY (1948).

Experimental filmmaker Paolo Gioli makes films without cameras, or at least, he cobbles together pinhole cameras of his own from simple materials. The results are remarkable. We describe his work and link to a recent release of his work on DVD in Paolo Gioli, maximal minimalist.

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

The eleventh edition of Film Art contains a new sample analysis of Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom. We discuss some additional aspects of the film in Wesworld.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

At the end of each year we avoid doing a standard ten-best list by choosing the ten best films of ninety years ago. For 2015, we dealt with The ten best films of … 1925 (including Frank Borzage’s Lazybones, above). It was a very good year.

A rare French Impressionist film, Marcel L’Herbier’s L’inhumaine, has been released on DVD/Blu-ray by Flicker Alley. We discuss the film and its background in L’INHUMAINE: Modern art, modern cinema.

Film Adaptations

Our eleventh edition offers an optional chapter on film adaptations from a wide variety of art forms and even objects.

For thoughts on popular female novelists whose books were adapted into films during the 1940s and 1940s (and who sometimes became screenwriters), see Deadlier than the male (novelist).

Adaptations can be made from nonfiction as well fictional books. We look at how Dalton Trumbo’s life was made into a biopic in Living in the spotlight and the shadows: Jeff Smith on TRUMBO.

In a series of entries, we have commented on the adaptation of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit into a three-part film. For an analysis of the extended DVD/Blu-ray version of the third part, see A Hobbit is chubby, but is he pleasingly plump? (Links in that entry lead to earlier posts on this subject.)

As always, we have blogged about some recent books and DVDs/Blu-rays. See here (Vertov, sound technology, 3D), here, (Kelley Conway’s new book on Agnès Varda), here (experimental films, the first Sherlock Holmes, the Little Tramp), here (Tony Rayns on In the Mood for Love), and here (on some older foreign classics that have finally made it to home video in the USA, primarily those of Hou Hsioa-hsien). The publication of the eleventh edition of Film Art led us to look back on how it was written and some of the ideas that went into it. We took the occasion to introduce our new co-author, Jeff Smith. See FILM ART: The eleventh edition arrives!

We were also profiled in Madison’s local free paper, Isthmus, by Laura Jones, reporter and filmmaker. She read Film Art as a student.

The Big Short (2015).

Welles at 101, KANE at 75 or thereabouts

DB here:

Kristin and I are one-third through our New York stay, and blogging has suffered. There have been talks to give, old friends to visit, new friends to meet, and movies and exhibitions to see. And there’ll be more activities of these sorts to come. But I can’t let 6 May pass without some acknowledgment of Orson Welles.

That’s partly because I just finished a draft of the Welles section of my 40s Hollywood manuscript. (Yeah, that beast was another distraction from blogging. All 158,000 rough-hewn words of it are now dispatched to some unwary readers.) So Welles was on my mind already when the anniversary of the “official” Citizen Kane release came up on 1 May.

Actually, by the time Kane had that roadshow release, it had been widely seen by the Hollywood community. In the face of the Hearst press’s attacks, RKO head George Schaefer held invitational screenings in early 1941 to build up support for the film. Variety estimated that by late March 1,200 producers, directors, writers, actors, and agents had seen the picture. The number was so big that RKO dispensed with a splashy Hollywood opening. (The article title is pure Varietyese: “So Many Cuffo Gloms at ‘Kane’ It Kayoes Idea of a $5.50 Preem,” Variety, 2 April 1941, 2, 20.) As a result, I think, Kane‘s influence began to be registered some months before its New York premiere, as the look of The Maltese Falcon (shot June and July of 1941) might suggest.

What I offer today, on the Boy Wonder’s birthday, is a consideration of that movie from an unusual angle looking not just at its originality but also at its shrewd consolidation of a variety of techniques.

Wellesapoppin’

We’re so used to considering Kane powerfully original that it’s worth remembering that it synthesizes a lot of traditions. I’m not thinking of Pauline Kael’s claim that it’s a culmination of the 1930s newspaper genre; as so often, she fails to persuade me. I’m thinking instead of the look and sound of the movie, as well as its storytelling strategies.

Depth staging and deep-focus cinematography are two techniques not always kept distinct in critical discussion. 1930s Jean Renoir films have plenty of depth staging but usually not so much deep focus. Citizen Kane won attention partly because it has plenty of both, and in exaggerated form. The figures often stretch very far back, someone or something is often rather close to the camera, and often all of them are sharply focused.

Without taking anything away from the boldness of Welles and cinematographer Gregg Toland, we should recognize that they reworked visual patterns—what I’ll call schemas—that were already circulating in filmmaking. Framings with big foregrounds, distant planes, and low angles weren’t unknown in silent films (Opium, 1919; Greed, 1925; A Woman of Affairs, 1928) and some early talkies (No Other Woman, 1933).

There was a sort of fad for such deep staging, especially with wide-angle lenses, during the late 1930s, though all the planes weren’t usually kept in focus. Some directors, such as John Ford (here and here) and William Wyler, favored deep images, while art director William Cameron Menzies (see here and here) made them part of his artistic signature. Below: Ford’s Long Voyage Home (1940), shot by Toland, and Menzies’ Our Town (1940), directed by Sam Wood.

It’s now acknowledged that many of Kane’s deepest shots weren’t actually made in the camera, but by means of special effects, particularly matte shots. Interestingly, this too wasn’t utterly original; compare the composite shot from Kane with the one from Mr. Moto’s Gamble (1935), which has an even more aggressive foreground.

Welles and Toland called attention to these techniques by a radical gesture: many of these deep shots are long takes from a fixed camera position. Most filmmakers who used these depth schemas inserted them into passages of orthodox scene dissection. The depth shots might establish a locale, or they might be inserted into a series of analytical cuts, or they might be part of a shot/ reverse shot pattern. But in Kane you’re forced to notice the Baroque plunge of space because the lengthy take rubs your nose in the flashy composition.

It’s clear that Kane crystallized a certain look that was picked up by John Huston, Anthony Mann with or without his DP John Alton, and many other directors. The Welles/Toland version of depth consolidated a visual style that dominated American black-and-white filmmaking into the 1960s. Typically, though, filmmakers didn’t rely on the fixed long take as much as Welles did in Kane. Even Welles gave up that option in favor of dynamic editing of deep-focus shots, as in The Lady from Shanghai (1948) and Othello (1952/1955).

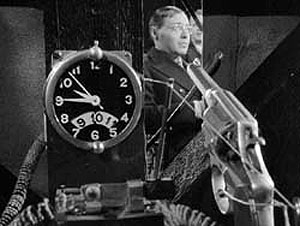

Not everything is long takes and depth. The pictorial variety of the film is, I think, unprecedented. The “News on the March” sequence becomes a virtuoso exercise in all the techniques that the rest of the film won’t be using. For perhaps the first time in history, Welles artificially distresses his staged scenes to make them match archival footage. He adds scratches and light flares.

This newsreel is so film-savvy that it can build in jump cuts and fast-motion as guarantors of fake authenticity. One passage mimics two-camera reportage, allowing us to imagine paparazzi crouched and perched at a fence to grab clandestine shots of an elderly Kane.

Here the schemas that are borrowed come from archival and documentary traditions, repurposed to add realism to this fictional biography. Welles, as we’ve seen in the Great Ambersons Poster Mystery (here and here and here), was a smart-alec cinephile: your disobedient servant.

What about sound? Back in 1994, Rick Altman wrote a pioneering article showing how Kane manipulates our sense of auditory space, and he connected that to Welles’ use of radio conventions. Contrary to what we might expect, Welles’s soundtrack doesn’t create much “deep-focus sound”; Altman shows that our impression of that is created chiefly by an overall reverberation rather than precise placement of sonic events. Altman also stresses Welles’ use of sudden, loud sound events to start or end a scene–another radio technique.

Today we’re lucky to have a great many of Welles’ radio programs available on the Web, and we can appreciate how his rich soundscapes mingle noises, dialogue, and voice-over narration. These shows remain very gripping. Listening to Kane in the same spirit, I’ve been impressed with how talky it is, how sounds crash in on you, and how even bursts of silence can be startling. Welles told one biographer that he aimed to create spiky transitions, both visual and sonic, because he thought most films of the period were dull.

He had already made his stage reputation on “shock effects,” those stunning high points in particular productions: the death of Macbeth in the Harlem production (1936), an actor’s headfirst tumble into the orchestra pit in Horse Eats Hat (1936), the mob’s murder of Cinna the Poet in Caesar (1937), the guillotine scenes in Danton’s Death (1938), and police agents firing from the audience in Native Son (1941). He became known as a director of thrilling moments, ever willing to sacrifice steady buildup to anything that would astonish. Forties theatre critics had a name for it: “Wellesapoppin’.” That quality dominates Kane’s images and sounds.

Remembering, recounting, replays

Otto Hullet, Barbara O’Neill, and Orson Welles in Sidney Kingsley’s Ten Million Ghosts (1936).

Just as Kane amplifies visual and auditory schemas already in circulation, the film does somewhat the same thing to narrative strategies. The key innovation here involves flashbacks and point of view.

Flashbacks were rare in the 1930s, but the early 1940s began a flashback craze that continued throughout the decade. Between August 1940 and December 1941, every top studio tried out flashbacks in a major release: The Great McGinty (Paramount), Kitty Foyle (RKO), I Wake Up Screaming (Fox), H. M. Pulham, Esq. (MGM), and Strawberry Blonde (Warners). A reviewer claimed that the “retrospective viewpoint” technique in A Woman’s Face, released the same month as Kane, “had of late become commonplace.” By September 1941 the Los Angeles Times critic considered the technique overused.

Even though the trend was already launched, Kane probably strengthened Hollywood’s inclination toward time-shifting. Again, it crystallizes in an influential way possibilities opened up in film, radio, theatre, and other media.

Kane’s central premise—a dead man recalled by one or more survivors—had been rehearsed in earlier films. The Power and the Glory (1933), scripted by Preston Sturges, was probably the most noted experiment in that vein. (For more, see this long-ago entry.) Another example was The Life of Vergie Winters (1934), which begins with a funeral procession and flashes back to the start of a backstreet love affair. (See this entry.) The Escape (1939) centers on a doctor who tells a crime reporter about a recently deceased neighborhood gangster, and flashbacks enact his tale.

These earlier examples stick to a single teller, while Kane offers reports on its dead man from five characters. Here again, however, there are precedents. In fiction and drama, trials have long served as motivation for flashbacks from multiple viewpoints. A major example, perhaps the first, is Robert Browning’s verse novel The Ring and the Book (1868-1869). Multiple tellers recounting events in flashback were staples of Hollywood courtroom dramas too. Beyond the trial-based format, Welles’ radio programs had welcomed multiple storytellers, sometimes embedding them within one another’s tales, sometimes letting them banter with each other.

Kane assembles views on a person rather than evidence of a crime, but even this is not completely unknown. Some playwrights had tried out what Kane screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz had called the “prismatic” approach to an absent central character. Sophie Treadwell’s play Eye of the Beholder (1919) portrays an offstage woman as seen through the eyes of her former husband, her lover, her lover’s mother, and her own mother. The play These Few Ashes (1928) presents the life of a (supposedly) dead roué through the recollections of three women, each of whom sees him quite differently.

Then there’s reporter Thompson’s investigation. The Power and the Glory’s exhumation of the tycoon’s past is presented simply as his old friend’s recounting; it’s not the investigation of a mystery. Kane innovated in the biographical film genre by creating curiosity based on the dying man’s last word, “Rosebud.” That device shifts us to the terrain of the detective story. The dying message had become a mystery-tale convention from Conan Doyle onward, and Welles and Mankiewicz shrewdly recruited it for their purposes (although it’s not clear exactly who hears Kane say the crucial word).

In blending conventions of several genres, Kane motivates the flashbacks on diverse grounds. The film’s detective-story side is anticipated by The Phantom of Crestwood and Affairs of a Gentleman (1934); in both, flashbacks represent the suspects’ answers under questioning. Like The Escape, Kane uses a reporter’s search for a story to justify its flashbacks, and the reporter isn’t the protagonist (as he’d be in a typical newsman movie). And being something of a biopic, Welles’s film can trace the rise of a great man from the vantage point of old age, as in Edison, the Man (1940). By the way, that’s another film of the era using a journalist’s questioning to launch flashbacks to a person’s life.

Another wrinkle: Kane’s flashback organization skips around in the past. Episodes of Kane’s life are not presented in 1-2-3 order. Plays set in courtrooms, such as Elmer Rice’s On Trial (1914), had rendered flashbacks out of sequential order, and so had radio dramas. Welles’ 1938 radio adaptation of Dracula shuffles episodes in the manner of the source novel. Non-chronological strings of flashbacks weren’t common in film, but The Trial of Vivienne Ware (1932) and The Power and the Glory used them significantly.

Even rarer is the replayed flashback, the scene from earlier in the film that is repeated, usually to reveal something we hadn’t caught on the first pass. Kane has occasion to present a brief replay from differing character viewpoints. Susan’s opera premiere is first treated curtly, as the object of the stagehands’ scorn. Later, in her flashback, the same scene registers the central characters’ reactions: a severe Kane, a bored Leland, the harried singing master, and above all the panicked Susan.

Replay flashbacks were rare in the 1930s, but The Witness Chair (1936) provides one example. After Kane, they would become more common, with Mildred Pierce (1945) offering one of the period’s most complex examples. (I discuss it here and here, with a video here.)

Even the coup de théâtre of following Kane’s death with a newsreel can be seen as revising a schema. “News on the March” isn’t exactly a flashback, but it provides exposition by shuttling among time periods in a manner characteristic of the film to come. Projected headlines and documentary footage, faked or actual, had found their way into 1930s theatre practice, notably in the WPA Living Newspaper productions. Many 1930s films opened with montage sequences using headlines, stock footage, and voice-overs like those in newsreels; The Roaring Twenties (1939) is a bold example. Gabriel over the White House (1933), with its mix of library footage and staged shots, anticipates Kane somewhat, as does Welles’ script for an uncompleted 1939 RKO project, The Smiler with a Knife, which includes a newsreel surveying the career of the fascist villain.

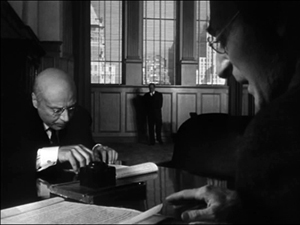

Another, less proximate source may be Sidney Kingsley’s 1936 Broadway play Ten Million Ghosts. This strident antiwar tract lasted only eleven performances and was never published; I took a look at a copy of the script last week. In the original production Welles played the naïve young poet André in love with the daughter of a munitions magnate during World War I.

Ten Million Ghosts includes a scene in which arms makers spend an evening watching a battlefront newsreel in their parlor. Kingsley’s purpose is to show the capitalists as utterly indifferent to the slaughter that the camera records.

They watch in silence for a while. Then there are technical comments on the explosives, shells, etc. as we see them hurl geysers of earth and men into the sky.

Was this embedded newsreel an early source for News on the March? Scholars have wondered. And there’s more.

As the film unwinds, André, who has learned that his family has been killed in the war, cries out in protest. Madeleine is torn between him and her father. To win her over her father angrily defends his double-dealing between both sides in the war. It’s all just business, he insists. Then we get this piece of action:

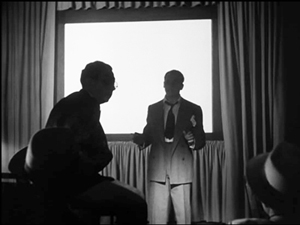

De Kruif rises, intercepting the beam of the projecting machine, his face highly lighted, his shadow, black and ominously magnified, thrown on the screen superimposed over the pictures of men writhing in bloody destruction.

Was De Kruif’s moment in the play a visual idea that inspired Kane’s projection-room scene? If so, Welles and Toland revised the premise of the play. Instead of the rather obvious looming shadow cast on the screen, the story editor is a silhouette against the blank white rectangle, and then, in a reversed setup, he becomes another silhouette, this time splitting the projector beam.

Welles told Peter Bogdanovich that he never saw the projection scene in Kingsley’s play because he was always back in his dressing room at that point. But as Pat McGilligan points out in his new biography Young Orson, Welles could hardly have been unaware of the film-within-the-play; many critics commented on it. More decisively, in the playscript, André is clearly onstage during the screening. He cries out against the carnage: “Look, look! Those are only pictures. . . Out there it’s real. . .” Peter Noble’s 1956 biography The Fabulous Orson Welles quotes Welles as declaring that this scene left a strong impression on him.

It’s not enough just to mention some sources. If you practice historically-slanted criticism, you need to ask not only “Where from?” but “What for?” In other words, you have to ask how elements that a filmmaker inherits get repurposed for the particular movie.

So, for instance, Kane’s depth-designed images held in long takes allow a more “theatrical” shift of attention within a visual field (driven largely by following who’s speaking). They also create contrasts of scale and visual weight. And each scene will have its specific demands that the depth technique fulfills. A depth shot can present cause and effect in the same frame, and it can build suspense by letting us await Kane’s interference in a foreground situation.

Similarly, Kane’s narrative strategies, synthesizing so many earlier efforts, blend to create a mystery that isn’t about whodunit but rather “why’d he do it?”

I’m not exactly saying that everything is a mashup. But that slogan does capture the fact that in art nothing comes from nothing. Kane blends several options that had been circulating in popular culture and high culture for some years. Like others before and since, Welles revised schemas tried out earlier; he combined some, exaggerated some, and infused many of them with new force. Because of his film’s prestige, he gave thrusting imagery, bold sonic manipulations, and complicated time shifts a new prominence in Hollywood filmmaking. The Forties had begun.

There are a several essential Welles sources. Apart from the many fine critical studies (see especially Jim Naremore’s Magic World of Orson Welles and Joe McBride’s What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?), the biographical surveys I habitually turn to are Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, This Is Orson Welles (Da Capo rev. ed., 1998), with a painstaking chronology by Jonathan Rosenbaum; the three-volume Simon Callow biography; Bret Wood’s Orson Welles: A Bio-Bibliography (Greenwood, 1990); Barbara Leaming’s Orson Welles: A Biography (Viking, 1985; my reference to shock effects is from p. 338); Frank Brady’s Citizen Welles (Scribners, 1990); and most recently Pat McGilligan, Young Orson: The Years of Luck and Genius on the Path to Citizen Kane (Harper, 2015). Pat’s discussion of Ten Million Ghosts is on pp. 366-367; Welles’ misremembering of the production is on p. 78 of This Is Orson Welles. A typescript of Kingsley’s play is held in the New York Public Library, at the Lincoln Center Library for the Performing Arts.

Rick Altman’s study is “Deep-Focus Sound: Citizen Kane and the Radio Aesthetic,” Quarterly Review of Film & Video 15, 3 (1994): 1-33. If it’s available without cost online, I haven’t found it. The programs “Dracula” (1938), “The Hurricane” (1939), and “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” (1940) provide vivid examples of multiple narrators and embedded flashbacks. For a comprehensive account of Welles’ radio work, see Paul Heyer, The Medium and the Magician: Orson Welles, the Radio Years 1935-1952 (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2005). As for prismatic flashbacks, in the mid-1930s, Mankiewicz had built the plot of an unfinished play around the memories of people who had known John Dillinger. See Richard Meryman, Mank: The Wit, World, and Life of Herman Mankiewicz (New York: Morrow, 1978), 247, 258.

On Kane‘s visual style and its place in film history, see my accounts in The Classical Hollywood Cinema (1985) and On the History of Film Style (1997), as well as on this site (here and here especially). A detailed analysis of Kane‘s narrative strategies is in Chapter Three of Film Art: An Introduction, 11 ed., (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2016). The distinction between depth staging and deep cinematography is explored in Chapters Four and Five.

THE PRESTIGE, one way or another

DB here:

Thanks to our web tsarina Meg Hamel we have now posted an analysis of sound in Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige on our site. It sits along with others under the rubric Books>Film Art. Or you can go directly to it.

It was originally included in the last couple of editions of Film Art: An Introduction. Why is it here now?

One of the most original aspects of Film Art from the beginning (1979) was our belief that for each technique we surveyed (cinematography, editing, etc.) we provide one example of how the technique functioned either in an entire sequence or across a whole film, or both. This, we thought, would get beyond one-off technique-spotting (“The low angle makes him look powerful”) that was common in other texts.

For several editions our sound chapter examined a sequence from Bresson’s A Man Escaped, while tracing how its use of sound fitted into the film as a whole. But we were told that the example was becoming problematic for teaching, because students had trouble concentrating on the sound while reading subtitles. So we put the Bresson analysis up on this site and I wrote something new on The Prestige (still my favorite Nolan film).

It turned out very lengthy and somewhat more intricate than our other analyses, partly because of the plot’s boxes-in-boxes structure. (One guy reads another guy’s journal, in which he’s reading the first guy’s journal….) So, because we had to keep within space limitations, we replaced the Prestige analysis with a briefer one of sound in The Conversation, co-written with Jeff Smith. That film, to be fair, is probably more frequently taught than the Nolan.

On the bright side, I’m happy that the Prestige analysis is likely to find new readers by being openly available on the Net. Had things gone differently, we’d probably have adapted it into a chapter of Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages. But then you’d have to pay to read it, and now you have it for free.

Our new edition, number 11, of Film Art will be appearing early in 2016. Kristin, Jeff, and I have added some new things to it and its online progeny. We’ll be previewing more of it in the weeks to come. In the meantime, let’s just say FA 11 includes a new analysis of another film. Look at the cover below and guess which one.

Apart from our Nolan book and the entries it’s based on, I study another aspect of The Prestige here.