Archive for the 'Film technique: Sound' Category

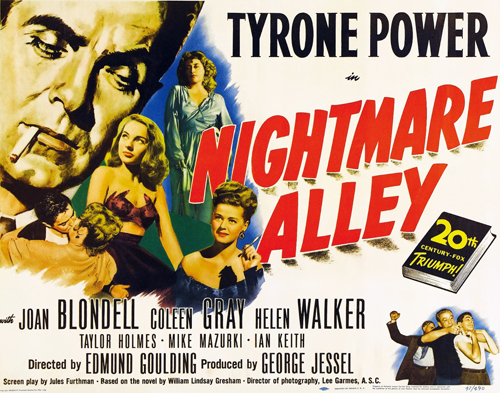

NIGHTMARE ALLEY: Do we hear what he hears?

DB here:

In the 1940s, American cinema turned wildly subjective. Visions, daydreams, nightmares, optical and auditory POV, inner monologues, flashbacks, and stream-of-consciousness montages were popping up everywhere. Sometimes these techniques rendered what it felt like to be the character at that moment. At other times, they were occasions for gags, or padding, or spikes of emotion, or flamboyant spectacle.

Sometimes they were just weird.

Siren song

One of the most intriguing passages in Forties films comes at a climactic moment in Nightmare Alley (1947, the year I was born). Spoilers ahead.

Stan Carlisle has been involved in a complicated swindle with the help of psychologist Lilith Ritter. He has entrusted her with $150,000 in cash extracted from their mark. When the plan goes wrong, he reclaims the money and heads for the railroad station to meet his girlfriend Molly.

In the cab en route to the station, Stan discovers that the wad of cash Lilith has given him consists of 150 singles. He returns to her apartment to confront her. There Lilith suddenly goes coldly clinical, declaring that Stan is deluded. Just as he thinks he killed a man in Texas, and he has imagined that she’s involved in his swindle. She denies any collusion with him, but does hint that she could get him indicted for the killing.

Since he has been growing more anxious, her calm stream of lies unnerves him. And since she records all her sessions with her patients, she has his first visit as a confession to the Texas killing. She has been careful to never record their swindle plot.

As Stan gets more panicky, we hear a police siren. He reacts, but Lilith does not. She claims not to hear it; she says he’s just imagining it, like everything else. When she offers to take him to a hospital, he pulls away and flees, without his money.

Here’s the scene.

Is the siren objectively in the scene, or is it in Stan’s head?

Lilith says she doesn’t hear the siren, so it might be subjective, manifesting Stan’s guilty conscience. And all the psychologist’s talk about hallucinations may have induced one in him. But the siren isn’t distorted in the way most auditory imaginings are; it seems plausibly part of the story world. And many viewers (including me, on my first viewing) assume that Lilith or her servant Jane has called the police, and the cops are now arriving. Lilith could be pretending not to hear the siren in order to convince Stan he’s loco. She does tell him to stay for a sedative.

There are several oddities here besides the siren. For one thing, Jane has made her entrance keeping Stan covered with her pistol. When Stan and Jane leave the bedroom, we see Jane hovering in the background.

As Lilith comes out she cocks her head screen left, signaling to Jane, and swivels the pistol firmly toward Stan.

Once Stan and Lilith get into their argument, though, Jane is no longer seen or heard. She’s last glimpsed as a sleeve on its way offscreen.

We never see Jane definitely exit the room. Is she there or not? Did Lilith’s head gesture mean “Stand over there to keep him covered” or “Go off and call the police”? The film’s continuity script (typically a transcript of the editor’s version with dialogue and effects but without music) says only “Jane crosses and exits scene.” That could mean she leaves the room or merely leaves the frame.

Moreover, we learn from cinematographer Lee Garmes, who shot Nightmare Alley, that Goulding preferred clearly signaled entrances and exits.

He had no idea of camera; he concentrated on the actors. He had the camera follow the action all the time. He was the only director I’ve known whose actors never came in and out of the sideline of a frame. They either came in a door or down a flight of stairs or from behind a piece of furniture. He liked their entrances and exits to be photographed. I like that; they didn’t just disappear somewhere out of the frame-line as they so often do.

“Disappear somewhere out of the frame-line” is just what Jane does.

Jane’s presence or absence matters because of the quarrel that ensues. When Lilith announces her betrayal of Sam, we might expect the muscular Stan to attack her, slapping her around like the good noir sucker he is. But he meekly takes her assault. True, he’s coming apart, but maybe he’s holding back partly because Jane still has him covered from offscreen. That assumption seems validated at one point, when Stan’s nervous glance sharply off right suggests that she’s still there with her pistol. It’s after that glance that he warns Lilith not to call the cops.

Of course he could be imagining Jane in another room calling the police. On the other hand, if we assume that Jane remains offscreen, Lilith’s cool story about Stan’s breakdown becomes motivated as a performance in front of a witness who can back her up.

Maybe the handling of Jane is just clumsy direction on Goulding’s part? Or just conciseness? Still, there’s that siren. If Jane is in the room all the while, and we don’t hear her telephone the cops offscreen, the siren can’t be the result of a call for help. And it’s not clear that Lilith had the time to phone the police after Stan left the bedroom.

So maybe the siren is indeed in Stan’s head. Or if it’s objectively in the story world, then maybe it’s just a coincidence. (Chicago has plenty of sirens.) In this case, Lilith takes advantage of the siren to weaken Stan’s grip even more. A further complication: The siren cuts off as Stan flees, but there’s no indication that the cops have arrived outside. And in another oddity, we see Lilith turn slightly toward the camera when she denies hearing the sound. Is this a mark of evasion, like blinking?

In sum: The siren is either subjective or it’s objective. If it’s subjective, it’s at variance with most subjective sound of the period in not being signaled clearly as such. If it’s objective, it’s either the result of somebody calling the cops from offscreen, or it’s just coincidental.

Which is it? Usually a Forties film is pretty explicit when we’re in a character’s head, if only in retrospect (e.g., the staircase “death” in Possessed, 1947). Nightmare Alley seems to fudge things here.

When being a geek isn’t chic

Am I over-thinking this? The commentators on the Eureka! DVD, noir experts Alain Silver and James Ursini, puzzle over the siren too. I think that when Lilith denies hearing it, most viewers feel a bump: after all, we hear it too. But soon, I think, most of us take it as a real siren and assume that Lilith seizes on it as another way to convince Stan he’s breaking down. As for Jane, we just forget about her.

Look at the overall film, though, and the subjectivity possibility gains a curious strength. The siren can be taken as part of a peculiar pattern running through the film. To show you what I mean, I need to rehash a fairly complicated plot. Bear with me.

Stan Carlisle, an ambitious carnival worker, is conducting an affair with Zeena, the fortune-teller, while her partner Pete sinks into alcoholism. Stan accidentally kills Pete by giving him a bottle of wood alcohol instead of moonshine. Partnering with Zeena, Stan masters a code system for a mind-reading act. Soon he has left Zeena behind and married the carnival entertainer Molly, who becomes his confederate in a ritzier nightclub mentalist act. But Stan is plagued by memories of Pete’s death. He visits a psychologist, Lilith, to whom he tells his guilt feelings.

Stan conceives a grand scheme to turn faith healer, using his skills at illusion and fake spiritualism. (“The spook racket: I was made for it.”) He manages to deceive the rich Ezra Grindle, who asks to see his deceased lover. The scheme, in which Molly impersonates a spirit, fails and Stan has to flee, hoping to take with him the money he’s already wormed out of Grindle. Lilith blocks that in the scene I’ve excerpted.

Stan leaves Molly and begins to spiral downward into drunkenness. By the film’s end he’s ready to take on the job of the geek, the subhuman carnival freak who bites heads off chickens. Originally Stan had despised the geek, but now, in order to be guaranteed a bottle a day, he declares: “I was made for it.” Only Molly’s tender concern holds out hope Stan might claw his way back.

I said the plot was complicated, but it rests on a set of fairly simple substitutions. The opening situation gives us two couples, Zeena and Pete, Molly and the strong man Bruno. Initially Stan was odd man out, paralleled by the geek (also on the fringes of the action). Stan replaces Pete as first Zeena’s lover and then her stage partner. But once Stan knows the mentalist codes, he can replace Zeena with Molly, whom Bruno surrenders. Later Zeena and Bruno will form a couple. In Stan’s rise, Molly gets replaced by Lilith, his partner in crime, if not in romance. When Stan’s swindle fails, he goes on the run, alone again. Pete was established as one step up from geekdom; without Molly, he said, he’d be a geek. Now Stan becomes the new Pete. Drinking around a campfire with bums, he even repeats Pete’s cold-reading spiel word for word and gesture for gesture, with a bottle of booze as the crystal ball.

Stan finally sinks to the bottom, willing to serve as a carnival geek for the standard bottle a day. Molly now plays Zeena to the new Pete.

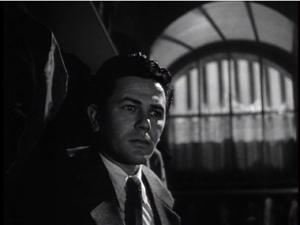

The pattern of sound leading up to the siren scene centers on the geek. In the crucial scene in which Stan gives Pete the rubbing alcohol, the geek’s cries punctuate the action as he dashes around in the distance; like Pete, he needs his daily bottle. But we hear those cries three more times later, when the action has left the carnival. The cries are displaced from their original source, and more insistent on each appearance.

The first time, they’re very faint. Zeena and Bruno have called on Stan and Molly in their nightclub dressing room. Zeena has brought out her Tarot deck and seeing Stan’s future she warns him not to try the big thing he’s contemplating. (It’s the fleecing of the grieving Grindle.) Worse, her cards bring up the Hanged Man, the same card that Zeena turned up for Pete. Once the association with Pete has returned, it’s hard to exorcise.

Angry, Stan forces Zeena and Bruno out, and as he stands at the door, with the music rising, we can hear the distant cries of the geek. In the next scene, the association with Pete is strengthened. Stan is getting a massage and the smell of the rubbing alcohol reminds him of the night of Pete’s death. Now, more strongly, we hear the geek.

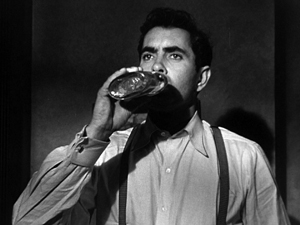

The motif-cluster is Pete’s death/Hanged Man/rubbing alcohol/the geek. This is brought back again, most obviously, when on his downward path Stan is holed up in a hotel room and instead of eating starts to guzzle a bottle of gin.

The compulsive drinking, along with Stan’s disheveled life, marks another stage in his conversion into Pete, and the geek’s cries are heard most plaintively now.

So what do we make of the geek’s cries in these scenes? If we take them as subjective, as Stan’s auditory flashbacks or imaginings, then the siren moment gathers a new force. If we’ve had access to Stan’s mental soundscape earlier, maybe we have it again when he “hears” the police coming. After several instances of subjective sound, we’re more prepared to take the siren as subjective too—and to wonder a bit about it even after we’ve concluded that it’s probably objectively in the scene.

That feint would be an interesting storytelling maneuver in itself. Yet other factors complicate things.

The geek goes Greek

In 1940s movies, there’s plenty of subjective sound. Often we understand that a sound is subjective by virtue of its acoustic quality; it may be given extra reverb or distorted in other ways. We also take it as subjective because the sound clearly isn’t coming from the scene. We often remember it from prior scenes and so treat it as an auditory flashback. But there are visual cues for subjective sound too. The two primary ones are a close view of the character whose mind we’re in, and an expression on the character’s face that indicates some intense feeling.

In The Fallen Sparrow (1943), Kit recalls his months in a Spanish prison chiefly through the scraping limp of one of his captors passing in the hall. When we’re given access to that acoustic memory, we get fairly close shots of Kit’s agitation.

In an interesting parallel to Nightmare Alley, when Kit is with Whitney, he thinks he hears the scraping footbeat again.

It might be a genuine offscreen sound, since we have reason to believe that his torturer has followed him to New York. (In the climax, the sound will be actual, not imaginary.) But at this point Whitney says she doesn’t hear the noise, and neither do we. This indicates that Kit is imagining it. The filmmakers faced a problem comparable to that in the Nightmare Alley scene. If the sound had played for us as well as for Kit, and Whitney said she didn’t hear it, the options are three: we’re in Kit’s head, though she isn’t; it’s real and she truly didn’t hear it; or it’s real and she’s lying (as Lilith may be). We couldn’t be absolutely sure we were in Kit’s head if the sound had been included, but when it’s not on the track, we know he’s hallucinating.

There are several norms to consider here. First, typically the close shot is timed to coincide with the subjective sound, indicating that the character registers the sound when we do. That happens in The Fallen Sparrow, but not in Nightmare Alley. We notice the siren before Stan does, which suggests that it’s objective.

Second, the shot isolating the character favors our taking a sound as subjective. But when another character is in the shot, it’s harder to construe as subjective. Accordingly, in The Fallen Sparrow, the shot that includes both Kit and Whitney inclines the filmmakers to treat the shot as objective and the sound as purely private, as inaudible to us as it is to her. In Nightmare Alley, the siren does indeed start over a close-up of Stan, but it continues over a reverse-shot of Lilith and soon enough, over a shot of the two of them.

Finally, our sense of subjectivity depends partly on the intrinsic norm each movie sets up. In The Fallen Sparrow the scraping footstep takes its place in long stretches of inner monologue which vocalize Kit’s thoughts. Because we’ve had intimate access to his mind, we’re likely to accept the footstep we hear as subjective as well. But Nightmare Alley doesn’t include inner monologues. We never access Stan’s stream of thought, so the geek cries are the only moments we might be plunging into his mind–at least, until (perhaps) the siren scene.

The siren scene hangs uncertainly between subjectivity and objectivity, tilting toward objectivity but also casting some doubts on it. What about the geek sounds? They’re even more complicated. They seem to hang between subjectivity and–well, something else.

Take the first instance. Stan is at the doorway and the camera tracks in to him as the musical score emerges. The geek noises slip in, and Stan pauses, as if reflecting.

That seems like a fairly standard cue for subjectivity: Stan has associated the Tarot cards and Pete’s death with the geek’s cries. Because of the faintness of the noise (some people seem not to notice it, as if the score nearly drowns it out), the narration might even be hinting that Stan’s memory of the night of Pete’s death is barely conscious.

In the light of the later occurrences, I’d propose another possibility. Given that we’ve never been in Stan’s head before, the sound might be more addressed to us than to him, reminding us of an association he doesn’t sense at all. This moment might almost be the film’s way of taking us aside and flagging a motif that will develop later–and in ambiguous ways.

In the rubdown scene, we see Stan, anxiously reacting to the smell of alcohol, in a fairly close view as the geek’s cries are heard.

In great anxiety, he leaps off the rubbing table. But perhaps he’s reacting just to the smell of alcohol, not to his memory of the geek. Again, the geek sounds are smoothly merged with a burst in the musical score.

Most characters who hear imaginary sounds report them to the people around them. But Stan hasn’t said anything, as far as we know, to Molly about twice hearing the geek. When Stan tells Lilith of the two earlier scenes during his therapy session, he mentions only being disturbed by Zeena and the cards, and the way the alcohol reminded him of Pete.

He doesn’t mention hearing the geek’s cries. So again we might ask if these cries aren’t subjective but rather something like a nondiegetic score–the soundtrack reminding us of something Stan isn’t remembering.

The last recall of the geek’s cries is presented while Stan is gulping gin. The noise starts in a medium shot before the camera retreats to a distant view.

If the cries make him feel tormented, he doesn’t give much sign of it. And if we were supposed to penetrate his mind, where the geek noises might reside, the camera would typically track in more tightly (as it does in The Fallen Sparrow). Instead, it withdraws, again raising the possibility that the geek’s shrieks are a commentary, not a recollection. Perhaps the cries are more like the Greek chorus warning us of an outcome to which the protagonist is oblivious.

What are we left with? Mixed signals, I think. The geek’s cries and the police siren hover in a space that many films worked within but seldom treated so freely. The cries can be taken as subjective, but they lack robust cues for that function. In other respects, they suggest expressive commentary. As the alcohol reminds Stan of Pete’s death, the cries do the same for us, while prophesying Stan’s fate. And the siren, while probably objective, makes us hesitate partly because we’re not sure the police have been called and partly because we’ve had ambivalent sound cues earlier. For a moment it might seem to be, as Lilith says, Stan’s first full-blown hallucination.

The continuity script for Nightmare Alley duly notes the siren’s sound, and the geek’s cries are noted in the scene of Pete’s death. But there’s no mention of geek cries in any of the three scenes I’ve considered. Perhaps director Edmund Goulding shot the film without planning to include the geek sounds at all. Perhaps they were added in postproduction. Someone late in the production process may have decided to anticipate Stan’s final degradation through ever more vivid echoes of the poisoning scene. Nightmare Alley would become an example of innovation by last-minute intervention.

Usually a 1940s film respects the distinctions, the either/or options, that are offered by the era’s stylistic menu. Accordingly, a sound is clearly objective or clearly subjective. But sometimes a film oscillates between the choices, or blurs the distinctions among them. We’re most familiar with this slipperiness when music shifts between being diegetic (sourced in the story space) and being nondiegetic (added to the story world “from outside”). This sort of looseness can be found elsewhere in 1940s storytelling. A film may start with one narrator and end with another, or none, or an uncertainly identified one. A flashback may never close, or loop back to its beginning without returning to the frame story. The outliers coax us to study how the ordinary cases work and note how much we take their conventions for granted.

We can learn as much about storytelling strategies from the ambivalent films as from the trim and polished ones. And in a movie called Nightmare Alley, we can’t regret that the haunting wail of the geek wafts through it as both a reminder of death and an anticipation of destiny. Its shape-shifting sound fits a movie that wants to unsettle us.

Fussbudget film analysis: I was made for it.

The continuity script for Nightmare Alley is available as a pdf file on the Eureka! DVD of the film.

Lee Garmes’ remark about explicit entrances and exits is quoted in Charles Higham, Hollywood Cameramen (Thames & Hudson, 70), 49-50. For background on the making of the film see Matthew Kennedy, Edmund Goulding’s Dark Victory: Hollywood’s Genius Bad Boy (University of Wisconsin Press, 2004), 241-252. There’s a detailed and intriguing psychoanalytic interpretation of the film at Randomaniac.

Actually, the scene in The Fallen Sparrow is a little more complicated than I indicate here, but I didn’t want to get into the weeds. The essential point holds, though: when one character thinks that a sound is veridical, and another character is present but doesn’t hear it, the filmic narration can confirm or disconfirm or ambiguate the source of the sound.

Thanks to conversations with Kristin, Jeff Smith, and Jim Healy about the film. Woody Haut’s lengthy discussion of the film for the Eureka! disc is reprinted on his website.

I discuss extrinsic and intrinsic norms of narration in Chapters 4 and 8 of Narration in the Fiction Film.

For other example of fruitful anomalies in the period, see “Innovation by accident,” “Twice-Told Tales: Mildred Pierce,” and the Laura discussion in “Dead Man Talking.”

1932: MGM invents the future (Part 1)

DB here:

Seldom can we point to a moment when a movie convention is born. When, exactly, did crosscutting for suspense start? (Not, apparently, with Griffith.) What was the dissolve first used to convey the passage of time? What film first updated us on story developments by whipping newspaper headlines up to the camera?

We’re rightly discouraged from asking such questions. For one thing, we probably can’t answer them; too many films are lost. And what may matter is not the first time a technique is used but the process by which it becomes normalized and widespread. That’s when it achieves significance in the history of film forms.

Still, occasionally we might be able to pinpoint a crystallizing moment, when the convention assumes a distinct identity. The problem then becomes tracing the uptake, the process that makes the convention standardized enough to be understood by audiences.

In working on Hollywood narrative conventions of the 1940s, I’m drawn to moments in earlier decades when certain storytelling devices seem to emerge, although maybe only in partial or bastardized or confused forms. Here’s an example.

We don’t usually look to the MGM of this period as a hotbed of innovation. We think of it as the star-glutted studio that under Irving Thalberg turned out plump, well-upholstered productions of classics like David Copperfield (1935) and Romeo and Juliet (1937). Yet the search for prestigious productions led two releases of 1932 to become benchmarks of cinematic storytelling. Those two films launched conventions that are still with us.

The one I’ll consider today involves voice-over sound. I’ll examine a second one in a later entry.

The voice within

The Fallen Sparrow (1943).

Like most terms of craft, voice-over has several meanings.

In one usage, voice-over is what we hear when a narrator recounts information during a flow of images. An external, voice-of-God commentary like that opening The Roaring Twenties (1939) is one example.

Or a character in the story may be recounting what happened in the past. As we see a flashback, we hear the voice of the character in the present. Perhaps the character is talking with another character, or writing a letter or diary entry.

In each of these conventions, the voice-over sound isn’t coming from the action onscreen. We don’t see a source in the scene, and typically we don’t see the external narrator speaking, or the character who is hosting the flashback. Moreover, the sound has a different timbre; it’s miked more closely and without ambient effects. Another cue that the voice is “over” rather than “in” the images is the choice of verb tense. In a flashback, a character narrator will use the past tense to describe the action we’re seeing, and usually an impersonal narrator will as well.

There’s another type of voice-over, though. Here the voice is not sensed as “over” the action but “in” it. The voice is representing a character’s thoughts at the moment. The cues for this are likewise pretty clear and redundant. Again the voice is closely miked. It accompanies a medium or close shot of a character, and the words are spoken by the character’s own voice. But the character’s lips aren’t moving.

We understand that the sound represents the thoughts in the character’s mind. Using the literary term, we can call this convention interior monologue. Unlike voice-over commentary, the interior monologue is marked by the present tense. The character will refer to himself or herself with the pronouns “I” or “you.” In the sense I mean, the character isn’t a narrator; the character’s thoughts are what is narrated, by the convention I’ve picked out.

Both conventions of voice-over are strongly associated with Hollywood cinema of the 1940s. Call Northside 777 (1948) opens with the external narration of a detached, documentary-style voice.

In the year 1871, the Great Fire nearly destroyed Chicago. But out of the ashes of that catastrophe rose a new Chicago. A city of brick and brawn, concrete and guts, with a short history of violence beating in its pulse.

The narrator goes on to describe a crime that took place in 1932.

The Fallen Sparrow (1943), by contrast, starts in a train compartment, with Kit McKitrick opening his suitcase, taking out his gun, and looking out the window. As the train goes into a tunnel, the windowpane becomes a mirror, as above.

Over this image we hear Kit’s inner monologue.

All right. Go on. Let’s have it. Can you go through with it? Have you got the guts for it? Or did they knock it out of you? Made you yellow?

The screenplay’s indications are as follows: “Kit stares at the reflection of his own eyes. Softly, barely audible over this, though Kit’s lips do not move:…” There follows a slightly longer version of the voice-over text.

The inner monologue is a venerable literary technique, used in novels for decades, and plays for centuries as the soliloquy and the aside. So you’d think that early American sound filmmakers would have adapted it quickly and without fuss. Actually, they don’t seem to have done so.

You can find auditory flashbacks (another device some would call voice-over). In City Streets (1931) while Nan stands by the bars of her cell we hear a fragment of an earlier conversation. To venture outside Hollywood, there’s the famous example from Hitchcock’s Blackmail (1929) in which the heroine seems to hear “Knife!” emerge from casual breakfast talk with increasing volume. Here, I’d suggest, we’re getting an impressionistic filtering and exaggeration of a word that’s repeated in the action of the scene. Both passages are subjective, but neither is an interior monologue. And both are rare examples in early sound cinema.

Hence the interest of Strange Interlude, which MGM made in the spring of 1932.

Thinking out loud (very)

It’s based on a 1928 play that won Eugene O’Neill his third Pulitzer Prize. Like many of O’Neill’s projects, the drama was massive and experimental. It consists of nine acts lasting five hours, with a dinner break after the fifth act. The production was surprisingly successful, running over a year on Broadway and touring to packed houses around the US.

The action seems fairly skimpy for such a long play. At the start, Nina Leeds is grieving over the wartime death of her beloved Gordon. An older friend of the family, Charles Marsden, is secretly in love with her. Nina plunges into nursing work at a veterans’ hospital, and a doctor there, Ned Darrell, is concerned about her careless promiscuity. Darrell himself is attracted to Nina but resists falling in love with her. Instead he suggests that she consider marrying Sam Evans, a bright but good-hearted college boy she’s seeing.

She does, but she learns from Sam’s mother that there is a strain of madness in the family, and if they have a child, the lunacy is likely to be passed along. The mother brazenly suggests that Nina find a new partner and pretend the love child is Sam’s. The target father becomes Dr. Ned, and of course he and Nina fall in love.

The sexy situation surely drew notice; there were censorship rows in some cities. In addition, the play’s undertones attracted an audience who was starting to hear about Freudian theory. The men are all displacements and substitutes for Gordon; Nina even names her son for her dead sweetheart. At the end, when Nina relaxes in Charlie’s arms, she confusedly calls him “Father,” which is all an up-to-date 1920s intellectual needed to hear.

The formal innovations of Strange Interlude stem from what some critics considered O’Neill’s urge to create a “novelistic” drama. This explains not only the play’s extreme length, but its span of over two decades. Years pass between acts. O’Neill sought, he claimed at the time, to trace the complete history of a woman’s life, in a way that would show facets of the “Eternal Woman”: innocence, passionate youth, early marriage, infidelity, motherhood, and eventual acceptance of old age.

Another facet of O’Neill’s “novelistic” ambitions was the expansion of the old-fashioned theatrical aside into a string of inner monologues. A character speaks his or her thoughts aloud, and while the other characters can’t hear them, we can. All the major characters are given at least one passage of inner monologue. A great many of these run very long, over a page in the play script, and they were largely responsible for the vast length of the show.

Like a novel, the play gives us omniscience, gaining access to several characters’ minds. The thematic thrust of the device was that we often think things that are the opposite of what we say. We wear “verbal masks.” The inner monologues tell us about the characters’ real thoughts, and these tumble together in contradictions and associations. Here’s a short example from the first scene, when Nina’s father complains to Charlie that Nina has become a brittle young thing.

PROFESSOR LEEDS (absent-mindedly). Yes.

(Arguing with himself.) Shall I tell him? …no…it might sound silly…but it’s terrible to be so alone in this…if Nina’s mother had lived…my wife…dead!…and for a time I actually felt released!…wife!…helpmate…now I need help!…no use!…she’s gone!…

This passage is tame compared to the fleeting feelings and contradictory attitudes that scamper through Nina’s monologues. The effect is to suggest characters whose surface politeness conceals both shameful secrets and volcanic feelings.

As you’d imagine, there were problem making these interludes work onstage. The solution hit upon was to have the silent characters freeze in place while the “thinking” character delivered the monologue and moved freely around the set. The difficulties were compounded when O’Neill packed a series of monologues close together; at some moments, characters’ monologues seem to reply to each other. The choreography of the first productions must have been something quite dazzling and may account for the play’s success with audiences.

On the track of monologue

Strange Interlude was one of several Broadway properties bought by Irving Thalberg and his story editor Samuel Marx. There were censorship constraints, so that Nina is no longer promiscuous and doesn’t abort her and Sam’s child. Still, in the film she does bear Ned’s child, and they mislead Sam into believing he’s the father. The plot is propelled by the lovers’ reunions at long intervals and their hesitation about revealing their secret to Sam, to Charlie, and to the grown-up Gordon. They rekindle their passion but decide not to run off or tell Sam the truth. If Nina is punished at the end, it’s because she’s never able to join Ned as his life partner.

Strange Interlude was one of several Broadway properties bought by Irving Thalberg and his story editor Samuel Marx. There were censorship constraints, so that Nina is no longer promiscuous and doesn’t abort her and Sam’s child. Still, in the film she does bear Ned’s child, and they mislead Sam into believing he’s the father. The plot is propelled by the lovers’ reunions at long intervals and their hesitation about revealing their secret to Sam, to Charlie, and to the grown-up Gordon. They rekindle their passion but decide not to run off or tell Sam the truth. If Nina is punished at the end, it’s because she’s never able to join Ned as his life partner.

The script cuts the action down to fit a 112-minute running time, largely by dropping or condensing monologues. Very long speeches in the play become two or three lines in the film. There remained the question of how to present the monologues on film. In the early talkie days, people weren’t certain what to do.

MGM publicized the menu of options being considered. Director Robert Z. Leonard largely rejected the play’s tactic, that of having the thinking character turn slightly to the audience and speak in a different tone of voice. For a time, the production team thought of using superimpositions. A ghostly double of one character would appear at the proper moment and utter the thoughts while the tangible character stayed silent. Alternatively, Leonard considered having the ghostly doubles entirely replace the actors during the monologues. Given the pace at which the monologues bounce around the scene, the superimpositions would have been throbbing in and out pretty often.

The solution was the one that’s obvious to us. We simply see the thinking character and hear his or her thoughts, more closely miked, while the actor’s lips don’t move. Why did Leonard and his colleagues even consider other options? Partly because rerecording was not yet established as reliable enough to allow inserting lines, some mere interjections, into the flow of the recorded dialogue.

In production, the problem was solved in a mind-boggling way. The film was shot twice. The first go-round recorded the entire text, dialogue and monologue, for each scene. The dialogue was timed to fractions of a second. Then the monologue portions were transferred to phonograph discs. Then the film was rehearsed and re-shot, with the discs used as playback guides for the actors’ pauses. And the playback was recorded on the set, with the dialogue.

When the film was finally cut, the cleanly recorded monologues from the first go-round were cut into the shots of the actors thinking. They were amplified and, I think, spruced up a little in mixing to yield a more intimate sound field. Often they’re whispered, or at least delivered in a subdued tone.

Today the technique looks fairly conventional, at least at any given moment. At the time it seems to have struck observers as a novelty. “It is a technique admirably suited to the audible screen,” remarked the New York Times critic, musing, “I wonder whether these spoken private thoughts will inspire another picture with them?” Variety mocked Strange Interlude as a critic’s picture, a natural for “discourses on academic analyses of the contemporary ‘art of the cinema.’”

Both opinions strike most of us as deeply wrong. Today Strange Interlude looks a misbegotten monster, opposed to nearly everything we would celebrate about Hollywood sound cinema. Just when films were starting to pick up the pace, this movie goes lugubrious. Perhaps in the theatre O’Neill’s monologues wrap the action in a rhetorical micro-dramas, but in the film they expose the plot as a relentless tango of bourgeois self-absorption. The monologues drain the film of curiosity, suspense, surprise, and affect. There is no mystery in it. Everything is said, every question answered in advance. It must be one of the most absolutely explicit films ever made.

Yet if we argue that poor works of art can have worthy historical influence, I’d submit Strange Interlude as Exhibit A. Its purpose was misguided, and it bungled achieving even that, but it threw up an important convention that would eventually enhance cinematic storytelling.

Keep it to yourself, and to us

As a novelty, the filmic inner monologue ran risks. The Los Angeles Times critic worried that the movie version could confuse people who hadn’t seen the play. The ballyhoo for the release talked it up as “the first to pioneer in a new field of the talkie; namely, the presentation on the screen of hidden thoughts as well as the regular spoken dialogue.”

To assist viewers with the convention, the film has a foreword implying that we won’t see lip movements.

In order for us fully to understand his characters, Eugene O’Neill allows them to express their thoughts aloud. As in life, these thoughts are quite different from the words that pass their lips.

The opening scene immediately reinforces the point. Charlie walks down the street, greeting a one-legged soldier. This reassures us by displaying normal dialogue.

Charlie comes to the camera and pauses at the gate, musing aloud, “This pleasant old town, dozing. What memories it brings back.”

Then we get the film’s first inner monologue. His voice clear, his mouth closed, Charlie eyeballs the camera in a confiding way no one else will in the film. “Queer things, thoughts. Our true selves! Spoken words are just a mask to disguise them.”

The device is bared. It has been sharply contrasted with external dialogue and spoken monologue, and the theme of hidden thoughts is blatantly announced. Soon enough, after embracing Nina, Charlie’s voice-over reminds us: “How she’d laugh if she could only read my thoughts.” In the film’s first moments, its unusual sound device is flagged with Hollywood’s customary redundancy.

Throughout the film, Charlie is the only character who will occasionally play to the camera, in an echo of the stage production. The gesture reflects his role as an ineffectual observer of the Nina-Sam-Darrell triangle. In the film’s first sequence, which corresponds to the play’s first act, Charlie is also a crucial force for exposition, getting the lion’s share of inner speeches. In earlier plans for the play, he was intended as a chorus or stage manager.

So the film introduces its narrational device very explicitly. But as a film it offers a chance to coordinate the dialogues more tightly than was possible on the stage. With one character speaking while the others freeze, there was an inevitable slackening of pace. The movie camera, however, can isolate the thinking character. We can’t see what the offscreen characters are doing, so often they more or less cease to exist during the monologues. Concentrating on one character, we forget the others.

Probably O’Neill intended the fragmentary quality of some of the monologues as an equivalent of the stream-of-consciousness technique that Joyce had brought to literature with Ulysses in 1922. But by linking voices in a fairly linear way, Strange Interlude achieves the effect of an older novel in the Balzac-Dickens-Tolstoy line. In these works the omniscient literary narration shifts among characters within a scene. The film firms up this sense of gliding from mind to mind by isolating characters in singles, cueing us to expect a monologue at any moment. Sometimes, however, the film dares to interweave its dialogues and monologues within a sustained shot. At one point an aside from Nina in a two-shot is echoed by one from Charlie; she passes the ball by lowering her eyes, while he lifts his head.

The interpolations become quite fast and precise, as you can see from this extract.

It seems to me that film uses the technique more judiciously than the play does. After Charlie’s ruminations have provided exposition, Nina and Ned, the furtive lovers, get most of the monologues. Occasionally the drama adds new characters, such as Sam’s mother and the little boy Gordon, who seems to intuit Nina’s guilty thoughts. The film stages some climaxes as a ping-pong game of monologues, often without the cushioning of dialogue bits.

Here the characters seem to be conducting telepathic conversations.

But enough about me

Today the inner-monologue technique in Strange Interlude seems at once familiar and peculiar. I think that’s because the convention, in both fiction and film, didn’t develop along the choral lines the play and film laid down.

Today novelists are advised to stick to only one point-of-view character per scene. A current manual warns: “If you simply jump from head to head as the mood strikes you, the voice becomes a fractured mess.” Manuals of O’Neill’s time gave the same advice. Critic Clayton Hamilton admitted that a viewpoint could shift from scene to scene or chapter to chapter (the so-called “limited omniscience” technique) but he stressed that within a scene, the author should stick to rendering only one character’s viewpoint.

This is what we have come to expect in mainstream cinema. Not only inner monologues but all channels of subjectively tinted information are usually slanted toward one character per scene. So a film might have several point-of-view characters in its overall running time (e.g., Psycho), but any given scene is likely to be anchored around one.

When inner monologue doesn’t do this, comedy can result. Cuddling on a sofa in Me and My Gal (1932), Danny and Helen discuss a picture he remembers as “Strange Innertube.”

Ten years later, in A Yank on the Burma Road, the same gimmick was yielding flat-footed comedy.

Perhaps because it seemed a bit silly, very few 1930s filmmakers seem to have picked up the inner monologue device for serious drama. When they did, the multi-voiced version seems more common. In The Life of Vergie Winters (1933), the main characters attend a political rally, and each one gets a bit of interiority.

Thornton Wilder’s play Our Town (1938) not only presented a commenting narrator in the form of a stage manager, but included a scene of a wedding ceremony that assembled thoughts issuing from the minister (played by the Stage Manager) and the bride’s mother. For the 1940 film version, other characters’ inner monologues were added.

Both Vergie Winters and the Our Town film also include moments focused on a single character’s inner monologue. Still, it’s remarkable how few films of the 1930s pick up on device at all. I speculate that storytellers became more comfortable with it as it became more common on radio late in the decade. The strategy was emphasized by Orson Welles and especially Arch Oboler. By 1939 Oboler was building entire plays out of what he called “stream of consciousness” technique. Soon the inner monologue as we know it started to be heard in talk-filled films like Angels over Broadway (1940) and noirish tales like The Stranger on the Third Floor (1940).

Perhaps it took radio to teach filmmakers the dramatic power of the inner monologue. It was certainly suited to many genres, from crime and suspense stories to melodrama and even comedies. Since it crystallized in the 1940s, the technique, while rare, has never really gone away. Ingenious filmmakers, from Resnais to Wong Kar-wai, have revived and revised it.

More generally, I suspect we should thank radio and the stage, including plays as ungainly as Strange Interlude, for urging filmmakers to try for more. These models pushed narration beyond the momentary shove and tug of character-in-a-situation and overlaid a speaking voice that undertook the task of remembrance, commentary, and confession. Novelistic cinema, of a certain kind, was launched.

A later entry will consider another convention launched by an MGM movie in 1932. But you have probably figured out what that is.

A big thank-you to Michele Hilmes and Shawn Vancour for helpful guidance in the literature of radio. I’ve also learned from Neil Verma’s Theatre of the Mind: Imagination, Aesthetics, and American Radio Drama (University of Chicago Press, 2012). Thanks as well to Kat Spring and Luke Holmaas for suggestions on 1930s sound.

On the staging of the play, see Philip Moeller, “Drama Makes Regular Stops,” Los Angeles Times (17 March 1929), C14. O’Neill’s novelistic intentions are discussed in “Origin of Drama Traced,” Los Angeles Times (3 March 1929), C16-C17.

I mention Ulysses as an influence, but surely O’Neill read Virginia Woolf, Ford Madox Ford, and other modernists too. The idea of a split-vocalizing character was explored in earlier avant-garde drama. One precedent which O’Neill might have known is the “monodrama” of Nikolay Evreinov. Eisenstein points out the parallel in his memoirs (Beyond the Stars, BFI/ Seagull, 1995), 521. (Thanks to Yuri Tsivian for the lead.) Joseph Wood Krutch defends the play’s novelistic introspection in The Nation (15 February 1928), 192. In all, Strange Interlude strikes me as an amalgam of the older novelistic tradition with the emerging stream-of-consciousness technique. Some, probably including me, would call the play a piece of middlebrow modernism.

On the making of the film, see “Filming ‘Interlude,’” New York Times (13 March 1932), X6 and Edwin Schallert, “Mute Stars to Speak Words,” Los Angeles Times (9 March 1932), 7. Lea Jacobs points out that re-recording practice in Hollywood faced problems of exact timing. Not until 1935, with the advent of “push-pull” tracks and click sheets, could filmmakers control in postproduction the tight interweaving of sources that Strange Interlude created through playback in production. See her Film Rhythm after Sound: Technology, Music, and Performance, discussed in an earlier entry. On Thalberg’s strategy of buying Broadway hits, see Mark A. Vieira’s Irving Thalberg: Boy Wonder to Producer Prince (University of California Press, 2010), 161-198.

The New York Times critic Mordaunt Hall reflected on the inner-monologue technique in “At the First Night of a Worthy Film” (11 September 1932), X3 and “The Screen: Eugene O’Neill’s ‘Strange Interlude’ Is Engrossing and Compact in Film Form” (1 September 1932), 24. The ballyhoo mentioned comes from Sid Grauman, who claimed he was going to embed a print of the movie into a wall niche of his theatre as a permanent memorial. See “‘Interlude’ Print to Be Sealed in Theater,” Los Angeles Times (23 July 1932), A7. The Variety review comes from 6 September 1932, 15.

The inner monologue is one type of what we call in Film Art “internal diegetic sound.”

Loyal Marxians will recall Groucho’s address to the audience in Animal Crackers (1930): “Pardon me while I have a strange interlude.”

Arch Oboler employs “stream-of-consciousness” in some of his 14 Radio Plays (Random House, 1940); his glossary explains the device as “Thoughts in the mind of character; method of delivery should be quiet, semi-monotone, with far less coloring than ‘conscious’ speeches” (257). The definition would cover flashbacks, but clearly some of Oboler’s 1939 plays such as Baby and The Ugliest Man in the World use the inner monologue. The former is printed in 14 Radio Plays, and the script of latter is available here. Go here to listen to both.

It seems clear that critics’ demand that viewpoint be restricted for an individual scene, however much it may shift between scenes, stems from the influence of Henry James. James argued for the unity and power of a limited point of view, often conceived as “seeing” the action from a certain character’s “vantage point.” “There is no economy of treatment without an adopted, a related point of view,” he writes in the preface to The Wings of the Dove. “I understand no breaking up of the register, no sacrifice of the recording consistency, that doesn’t rather scatter and weaken.”

What Joseph Warren Beach called “the well-made novel” trend that followed James placed great emphasis on this economy. See Beach’s neglected but astute The Twentieth Century Novel: Studies in Technique (Appleton Century Crofts, 1932). My paraphrase of Clayton Hamilton comes from Materials and Methods of Fiction (Doubleday Page, 1917), 1228-129. The contemporary advice I quote is in Sandra Newman and Howard Mittelmark, How Not to Write a Novel (Penguin, 2008), 164.

A bold use of O’Neill’s abruptly spliced monologues comes from a different author named James. In one scene of her detective novel Cover Her Face, the late P. D. James gathers several suspects waiting to be questioned. “All of them sat in essential isolation and thought their own thoughts.” James’ third-person narration is omniscient with a vengeance, leaping from mind to mind, quoting the thoughts in parallel blocks. The force of the scene comes not only from the jumps in viewpoint but also from the way they violate a cardinal convention of detective stories. The culprit, we have been told, “must not be anyone whose thoughts the reader has been permitted to follow.” Do James’ plunges into interiority clear these people of suspicion? The formulation comes from Ronald A. Knox, “A Detective Story Decalogue,” in Howard Haycraft, ed., The Art of the Mystery Story (Grosset and Dunlap, 1947), 194. Of course this rule applies to the puzzle-oriented story in the Sherlock Holmes tradition, not the thriller or suspense tale. For more on the difference see my web essay “Murder Culture.”

P.S. 22 March 2015: You never stop learning. I just discovered that George Meredith’s novel Rhoda Fleming (1888) contains a passage that prefigures, in all its awkwardness, the device of Strange Interlude, both play and movie. Rhoda and Robert are talking, and Meredith’s omniscient commentary shadows their lines with parenthetical indications of their thoughts. These mental interjections often contradict their spoken words.

“I’ve always thought that you were born to be a lady.” (You had that ambition, young madam.)

“That’s what I don’t understand.” (Your saying it, O my friend.)

“You will soon take to your new duties.” (You have small objection to them even now.)

“Yes, or my life won’t be worth much.” (Know, that you are driving me to it.)

“And I wish you happiness, Rhoda.” (You are madly imperilling the prospect thereof.)

And so on. This to-and-fro passage occurs in Chapter XLIII. And yes, the book isn’t called Rhonda Fleming, more’s the pity.

Strange Interlude.

Little things mean a lot: Micro-stylistics

DB here:

In The Sound of Fury (aka Try and Get Me!, 1951), Howard Tyler has drifted into crime under the guidance of a breezy sociopath. They commit a string of holdups, culminating in a kidnapping. Howard’s partner bashes in the skull of their young captive. Wandering drunk and despairing, Howard ends up in the apartment of Hazel, a lonely manicurist. As Howard lolls on the sofa, she turns away to switch off the radio.

The next move is up to us.

If we’re alert, we can spot, on the end table in the corner of the frame, a newspaper with a headline that may be announcing the police investigation.

At first Hazel takes no notice. Will she? She does. She lifts the paper and is appalled.

Hazel turns toward Howard. Now we can see the entire headline as she reads aloud: Police are intensifying the search. She hasn’t made the connection between her guest and the boy’s disappearance.

Panicked, Howard lunges at her and crumples the newspaper.

Will this display of shattered nerves tip Hazel off?

As in the bomb-under-the-table model of suspense, at the start we know more than both characters know. She’s unaware of the kidnapping, and he’s unaware that the cops have found the victim’s car. In addition, the arc of suspense around the headline is quite small, though it leads on to something larger: Will Howard give himself away to the unsuspecting Hazel?

I’m impressed by the economy of presentation. Hitchcock might well have treated this moment in point-of-view shots, and a fairly protracted series of them. Or imagine how several filmmakers today would have handled this scene. There’d be a slow a track-in to the headline, then a circling camera movement that first concentrates on the woman picking up the paper, then racks focus to Howard on the sofa in the background.

Instead, director Cy Endfield makes very small changes of framing and staging matter a lot. The camera simply swivels, the actress simply comes to the foreground and pivots. The entire action, crucial as it will prove in what follows, consumes only twenty-five seconds.

Some stretches of a movie tend to be simply, barely functional: connective tissue or filler. Shots show cars driving up to places where the real action will take place, or characters striding down a corridor before going into a doorway. Other images want to engage us more deeply, but they do it through immensity. They try to awe us with majestic swoops over the sea or into the sky. (Recent example: Interstellar.) But other films engage us through detailing. They train us to notice niceties.

The Sound of Fury moment creates its detailing through visual space. What about time? And what about auditory factors? Our old friend, the telephone call, can furnish some examples.

Number, please

Clay Pigeon (1949).

Filmmakers must always decide how much of any action to show. Sometimes that allows the director, the cinematographer, and the editor to create fine-grained delays. These might not build up a lot of suspense but they can make us uneasy, and prepare us for a surprise later down the line.

As we mention in Film Art, and discuss in a related blog entry, a telephone scene forces the filmmakers to choose among clear-cut alternatives. Do we see both parties? Do we see only one and simply hear the other? (And is the voice of the one we don’t see futzed?) Do we see one and not hear the other at all? Most films don’t ask more than simple functionality, but even a B man-on-the-run feature like The Clay Pigeon (1949) shows what can be done with details of timing in setting up a phone call.

Jim Fletcher has war-related amnesia. He doesn’t know why he’s about to be court-martialed for treason. After escaping from the hospital, he learns that he is accused of betraying his best friend during their time in a Japanese POW camp. After convincing Martha Gregory, the friend’s widow, that he’s innocent, he searches for proof. The Clay Pigeon sticks mostly with Jim, but like most suspense films it slips in bits of unrestricted narration as well. Jim’s quest is tracked by mysterious men, and brief scenes give us glimpses of the forces pursuing him: agents of Naval Intelligence, and a gang of counterfeiters protecting the Japanese soldier who tortured Jim in the Philippines.

It’s the familiar structure of the double chase, dosed with minor mysteries. For example, when Jim gets a lead from a management firm, he leaves the office but the narration stays with the secretary who notifies her boss that Jim has been asking questions.

Cut to the executive’s office, where the camera reveals many stacks of wrapped bills on his meeting-room table. Something sinister is going on here, but what?

The decision to insert information addressed to us alone has more subtle consequences in two telephone scenes. Jim calls Ted Niles, another veteran of the POW camp. During these scenes, the filmmakers had the option of showing only Jim and never revealing Ted at the other end of the line. That tactic would have enhanced mystery, but it would have thrown suspicion on Ted. If he’s Jim’s friend and ally, why not show him?

So the filmmakers show Ted replying in his apartment. But later it will be revealed that Ted is working with the gang. The task is to introduce this important character in a way leaving open the possibility of his treachery. The solution the filmmakers hit upon is to show Ted just before he picks up the line. Here is the first instance, when Jim cold-calls him.

The camera shows Ted innocuously answering the phone and learning, to his surprise, that Jim has tracked him down.

At first Ted seems annoyed, but then he smiles and agrees to help.

The scene ends on Jim hanging up. If we wanted to plant more suspicion of Ted, we’d show him hanging up too and reacting to the call.

A later scene starts much the same way, with Ted coming in to answer a ringing phone and getting a message from Jim.

Both scenes show Ted answering the phone in a completely innocuous way. Yet the very fact of dwelling on his action of coming to the phone can be seen as planting uncertainty. In the second scene, for instance, where is he coming from? And in both scenes, Ted frowns at certain points. Perhaps he is pondering ways of helping Jim, but the expressions leave open the possibility that he is plotting against him. Ted’s duplicity is fully revealed only at the climax. (See image surmounting this section.)

In a mystery situation, a few seconds showing Ted alone gain a force they wouldn’t have in another genre. Some viewers will be surprised, some will say they knew it all along, but either way the detailing of a moment here and there has opened the possibility.

Party line

The Clay Pigeon telephone scenes show the speakers in alternation. The give-and-take of the conversation is presented by cutting back and forth. Another option is simply to show one speaker and let us hear the other without seeing him or her. As we’ve noticed, though, that would tend to make Ted a more mysterious figure.

Yet another possibility is the silent treatment: One speaker is shown talking, and we don’t hear the other at all. This option forces our attention wholly onto the reaction of the person we do see, and keeps us in the dark about the words and tone of voice of the person at the other end of the line. If the Clay Pigeon telephone calls presented Ted this way, that would be another tipoff.

Still, suppressing one half of the conversation can pay dividends when we already know the characters. At the climax of Humoresque (1947), detailing involves not a prop or a passing moment. Instead, a simple cut accentuates the shift from one sound space, that of violinist Paul Boray’s dressing room, to another, the luxurious living room of his lover Helen Wright. When he gets her call, he can’t understand why Helen isn’t at his big concert. But she is distraught because her own worries about keeping Paul’s love have been reinforced by Paul’s mother, who insists that she’s no good for him. And Helen is drinking again.

The scene’s tension is ratcheted up by first presenting only Paul’s angry questioning. We don’t hear Helen’s replies. When the dramatic momentum shifts to Helen’s desperate excuses for missing the concert, we concentrate on her meltdown more intently because now we don’t hear Paul’s replies. Her emotional response is magnified by the yearning climax of Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet Overture on the radio broadcast–another reason to suppress Paul’s voice.

The scene has been split between Paul’s end and Helen’s. By not seeing Helen’s reaction to his urgent questions, we wonder what is keeping her away. Like Paul, we’re unaware of her torment. But then we see and hear her, and our inability to know what he’s saying makes his pleas seem ineffectual. Whatever he’s saying doesn’t seem to matter. A simple speaker/listener cut raises the scene to a new pitch, which will build still further when we follow Helen out onto the terrace. One more detail, brutal: We don’t hear Paul’s voice, but we do hear the click when he hangs up.

One thing that links all these Little Things: What the filmmakers did not do. Cy Endfield did not indulge in camera arabesques or POV cutting. Richard Fleischer and his colleagues did not suggest Ted’s duplicity with music or a noirish shadow. Jean Negulesco and company didn’t yield to the temptation to crosscut furiously between a panicked Paul and an anguished Helen. These directors did something rare today. They presented the situation with stylistic simplicity. That way the big moments–the revelation of Ted’s treachery in the train, the frenzied mob in The Sound of Fury, the all-enveloping climax of Helen on the beach–become more vivid. Big things need little things to seem bigger.

Thanks to Jim Healy, who introduced me to The Sound of Fury and The Clay Pigeon.

For more on the bomb under the table, see the followup entry here.

Lest someone think I’m dumping on Nolan, let’s just note that he can, when he wants, summon up niceties. (By the way, thanks to readers for hustling to our Nolan vs. Nolan entry, but they should read the one on The Prestige and our Inception series here and here to get a fuller sense of our estimation of him. All of these are put into reader-friendly order in an insanely inexpensive ebook…..)

Several other blog entries consider detailing in performance: Henry Fonda’s hands, Bette Davis’s eyelids, and the facial expressions in The Social Network. I’m still mulling an entry on eyebrows, which are terribly underrated. For another Joan Crawford tour de force, there’s this.

Humoresque (1947).

Picking up the pieces; or, a Blog about previous blogs

A not-so-intimate bedroom scene from Cinerama Holiday (1955).

DB here:

Many of our blog entries are written in response to current events–a new movie, a film festival in progress, a development in film culture. Later we sometimes add a postscript (as here) bringing an entry up to date. Today, though, enough has happened in a lot of areas to push me to post the updates in a single stretch. It’s a sort of aggregate of chatty tailpieces to certain entries over the last year or so. Should the impulse seize you, you can return to an original entry, and there are other peekaboo links to keep you busy.

Out and about

Drug War.

Kristin wrote in praise of Neighbouring Sounds when she saw it at the Vancouver International Film Festival in 2012. Roger Ebert gave it a five-star rating, and A. O. Scott placed it on his annual Ten Best list. This network narrative is Brazil’s official entry for the Academy Awards. Sample Neighbouring Sounds here; the DVD is coming in May.

The annual Golden Horse Awards at Taipei have finished, and the Best Picture winner was the Singaporean Ilo Ilo, which neither Kristin nor I have seen. It would have to be exceptionally good to match the other films nominated, all of which we’ve discussed: Tsai Ming-liang’s Stray Dogs, Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster, Jia Zhang-ke’s A Touch of Sin, and (probably my favorite film of the year so far) Drug War, by Johnnie To Kei-fung. Stray Dogs did bring Tsai the Best Director award and his actor Lee Kang-sheng a trophy for best lead. Wong’s Grandmaster picked up six trophies, including top female lead and Best Cinematography. Jackie Chan won an award for Best Action Choreography. Although his CZ12 struck me as pretty dismal as a whole, its closing montage of Jackie stunts from across his career was more enjoyable than most feature-length films. In all, this has been a splendid year for Chinese-language cinema.

Back in the fall of 2012, I celebrated Flicker Alley‘s admirable release of This Is Cinerama, a very important film for those of us studying the history of film technology. Now Jeff Masino and his colleagues have taken the next step by releasing combo DVD-Blu-ray sets of two more big pictures, Cinerama Holiday (1955), the sequel to the first release, and South Seas Adventure (1958), the fifth and last of the cycle. Both are in the Smilebox format, which compensates for the distortions that appear when the curved Cinerama image is projected as a rectangle. Fortunately, Smilebox retains the outlandish optics to a great extent. The image surmounting today’s entry would give Expressionist set designers a run for their money, and it recalls the Ames Room Experiments. Cinerama wrinkles the world in fabulous ways.

Filled out with facsimiles of the original souvenir books and supplemented with a host of extras putting the films in historical context, these discs are fine contributions to our understanding of widescreen cinema. Because film archives don’t have the facilities to screen Cinerama titles (if they even hold copies), we have never been able to study, or even see, films that now look gloriously peculiar. Dare we hope that, from The Alley or others, we’ll get The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962), a strange, clunky, likeable movie?

Bookish sorts

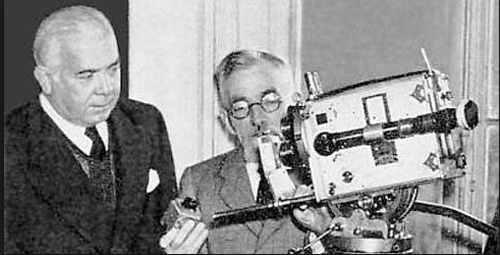

Spyros Skouras and Henri Chrétien.

2013 saw the first of our online video lectures, one on early film history and the other on CinemaScope. The response to them has been encouraging, but as usual nothing stands still. If I were preparing the ‘Scope one now, I would draw from the newly published CinemaScope: Selected Documents from the Spyros P. Skouras Archive. Skouras was President of 20th Century-Fox, and he kept close tabs on the hardware he acquired from Chrétien in 1953. This collection of documents, edited by Ilias Chrissochoidis, shows that Skouras saw ‘Scope as a way to follow Cinerama’s path and boost the studio’s profits. “I would hate to think what would have happened to us if we had not created CINEMASCOPE. . . . Certainly we could not have continued much longer with the terrific losses we have taken on so many of our pictures.” ‘

Scope didn’t rescue the industry, or even Fox, from the postwar doldrums, but some of the behind-the-scenes tactics of the format’s first years are revealed here. For example, Skouras hoped that filmmakers would put important information on the surround channels deployed by the format, in the hope that theatre owners would make more use of them. “Such scenes would have to be unusual ones, but even with my limited imagination I can visualize many scenes in which dialogue would be heard from only the rear or the sides of the theatre.” This seems fairly extreme even today.

Jeff Smith is a swell colleague here at UW–Madison. (He and I are teaching a seminar that’s just winding down. More about that, I hope, in a later entry.) In his May guest entry for us, Jeff wrote about the new immersive sound system Atmos. But he’s been busy filling hard covers too. Research articles by him have appeared in three new books on film sound.

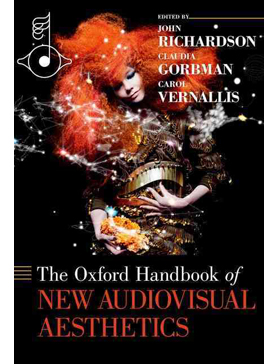

To Arved Ashby’s Popular Music and the New Auteur: Visionary Filmmakers after MTV Jeff contributed “O Brother, Where Chart Thou?: Pop Music and the Coen Brothers”–surely required reading in the light of Inside Llewyn Davis. He’s also a contributor to two monumental volumes that will set the course of future sound research. David Neumeyer has in The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies gathered a remarkable group of foundational chapters reviewing the state of the art. Jeff’s piece charts the changing relations between the film industry and the music industry, from The Jazz Singer to Napster and file-sharing. For another doorstop volume, The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, edited by John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis (three more top experts), includes a powerful essay in which Jeff shows how techniques of intensified continuity editing have their counterparts in scoring, recording, and sound mixing. Not to mention his forthcoming book on an altogether different subject, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. All in all, a busy man–the kind we like.

To Arved Ashby’s Popular Music and the New Auteur: Visionary Filmmakers after MTV Jeff contributed “O Brother, Where Chart Thou?: Pop Music and the Coen Brothers”–surely required reading in the light of Inside Llewyn Davis. He’s also a contributor to two monumental volumes that will set the course of future sound research. David Neumeyer has in The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies gathered a remarkable group of foundational chapters reviewing the state of the art. Jeff’s piece charts the changing relations between the film industry and the music industry, from The Jazz Singer to Napster and file-sharing. For another doorstop volume, The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, edited by John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis (three more top experts), includes a powerful essay in which Jeff shows how techniques of intensified continuity editing have their counterparts in scoring, recording, and sound mixing. Not to mention his forthcoming book on an altogether different subject, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. All in all, a busy man–the kind we like.

My March essay, “Murder Culture,” devoted some time to the women writers of the 1930s and 1940s who created the domestic suspense thriller–a genre I believe has been slighted in orthodox histories of crime and mystery fiction. The piece brought friendly correspondence from Sarah Weinman, editor of a new anthology from Penguin: Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives. She has assembled a fine collection, boasting pieces by Vera Caspary, Dorothy B. Hughes, Charlotte Armstrong, Dorothy Salisbury Davis, Margaret Millar, Patricia Highsmith, and Elisabeth Sanxay Holding (whom Raymond Chandler considered the best suspense writer in the business). These stories will whet your appetite for the excellent novels written by these still under-appreciated authors. Sarah’s wide-ranging introduction to the volume and her headnotes for each story will guide you all the way.

Finally, not quite a book but worth one: “The Watergate Theory of Screenwriting” by Larry Gross has been published in Filmmaker for Fall 2013. (It’s available online here to subscribers.) The essay is based on the keynote talk that Larry gave at the Screenwriting Research Network conference here in Madison.

Digital is so pushy

From Doddle.

Back in May, I provided an update on the progress of the digital conversion of motion-picture exhibition. Today, 90% of US and Canadian screens are digital, and over 80% worldwide are. (Thanks to David Hancock of IHS for these data.) I wish I could say the Great Big Digital Conversion was at last over and done with, but we know that we live in an age of ephemera, in which every technology is transitional. As I was finishing Pandora’s Digital Box in 2012, the chatter hovered around two costly tweaks.

The first involved higher frame rates. One rationale for going beyond the standard 24 fps was the prospect of greater brightness to compensate for the dimming resulting from 3D. Peter Jackson presented the first installment of his Hobbit film in 48 fps in some venues, and James Cameron claimed that Avatar 2 and its successor would utilize either 48 fps or 60 fps. And in January of this year some studio executives predicted that 48 fps would become standard.

Not soon, though. The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug will play in 48 fps on fewer than a thousand screens. Bryan Singer, who praised the process, has pulled back from handling the next X-Men movie at that frame rate. The problem is partly cost, with 48fps demanding more rendering and vast amounts of data storage. As far as I can tell, no one but Jackson and Cameron are planning big releases in the format.

The other innovation I mentioned in Pandora was laser projection. It too will brighten the screen, and according to its proponents it will also lower costs. Manufacturers are racing to build the machines. Christie has presented GI Joe: Retaliation in laser projection at AMC Theatres’ Burbank complex, and the firm expects to start installing the machines in early 2014. Seattle’s Cinerama Theatre is scheduled to be the first. NEC, the Japanese company, premiered its laser system at CineEurope in May. A basic NEC model designed for small screens (right) will cost about $38,000—an attractive price compared to the Xenon-lamp-driven digital projectors currently available. But the high-end NEC runs $170,000!

How to justify the costs? One Christie exec suggests branding: “Laser is a cool term that audiences immediately identify with.”

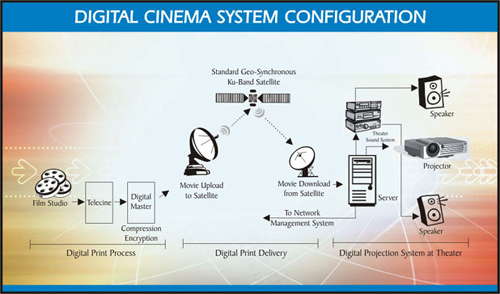

Perhaps the most important innovation since last spring’s entry involves an electronic delivery system. In October, the Digital Cinema Distribution Coalition, a consortium of the top three theatre chains along with Warners and Universal, launched a satellite and terrestrial network for delivering movie files to theatres. Theatres are equipped with satellite dishes, fiberoptic cable, and other hardware. The new practice will render the current system of shipping out hard drives obsolete, although the drives will probably continue for a time as backups. The DCDC has scheduled over thirty films to be sent out this way by the end of the year, and 17,000 screens in the Big Three’s chains are said to be hooked up. For more information, see David Hancock‘s IHS Analyst Commentary.

In the 1990s, satellite transmission was touted as the best way to send out digital films, and it was tried with Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones in 2001. Sometimes things move in spirals, not straight lines.

Speaking of the Conversion, an earlier entry pointed out the creative strategy used by the Lyric Theatre in Faulkton, South Dakota to finance its digital changeover. A gun raffle was announced on the Lyric’s Facebook page. Top prize was planned to be a set of three weapons: an AR-15 rifle, a shotgun, and a 1911 pistol.

The theatre’s screening season concluded, but the raffle is going forward, on New Year’s Eve, no less.

Television in public, movies in private

Dr. Who: Day of the Doctor (2013).

I can’t stand all this digital stuff. This is not what I signed up for. Even the fact that digital presentation is the way it is right now–I mean, it’s television in public, it’s just television in public. That’s how I feel about it. I came into this for film. —Quentin Tarantino

Spirals again. When attendance began to slump after 1947, Hollywood tried a lot of strategies–color, widescreen processes like Cinerama and ‘Scope, stereo sound, and not least “theatre television.” Prizefights, wrestling matches, and even operas were transmitted closed-circuit. Now theatre television is back, made possible by The Great Big Digital Convergence.

Godfrey Cheshire predicted some fourteen years ago that as theatres became “TV outside the home,” what we now call “alternative content” would become more common.

Pondering digital’s effects, most people base their expectations on the outgoing technology. They have a hard time grasping that, after film, the “moviegoing” experience will be completely reshaped by–and in the image of–television. To illustrate why, ponder this: if you were the executive in charge of exploiting Seinfeld’s last episode and you had the chance to beam it into thousands of theaters and charge, say, 25 dollars a seat, why in the hell would you not do that? Prior to digital theaters, you wouldn’t do it because the technology wouldn’t permit it. After digital, such transpositions will be inevitable because they’ll be enormously lucrative.

Godfrey’s prophecy has been fulfilled by all the plays, operas, and other attractions that run in multiplexes during the midweek or Sunday afternoon doldrums. His Seinfeld analogy was reactivated by last month’s screenings of Dr. Who: The Day of the Doctor in 3D. It was shown on 800 screens in seventy-five countries, from Angola to Zimbabwe, while also being broadcast on BBC TV (both flat and stereoscopic). The Beeb boasted that the per-screen average for the 23 November show beat that of The Hunger Games: Catching Fire. Globally, it took in $10 million, despite being available for free on TV and the Net. In the US, the event was coordinated by Fathom, a branch of National Cinemedia, a joint venture of the Big Three chains.

While some complained about dodgy 3D in the show, a surprisingly fannish piece in The Economist declared that “this landmark episode was buoyed up with fun, silliness, and hope.” The larger prospect is that other TV shows will take the hint and host season premieres or end-of-season cliffhangers in theatres. Many art house programmers would kill to show episodes of Game of Thrones or Mad Men, or even marathon runs of House of Cards. If it happens at all, I’d bet on Fathom getting there first.

I’ve had little to say, in this arena or in Pandora, about streaming and VOD, but these are becoming important corollaries of the Great Big Digital Convergence. Netflix in particular is expanding its reach, growing its subscriber base, creating original series, and enhancing its stock value, despite some ups and downs. At the same time, it’s pressing studios and exhibitors for the reduction in “windows,” the periods in which films are available on different platforms.

The theatrical window was traditionally the first, followed by second-run theatrical, airline and hotel viewings, pay cable, and so on down the line. Now that households have fast web connections, streaming disrupts that tidy business model. In October Ted Sarandos, Chief Content Officer for Netflix (right, with Ricky Gervais), suggested that even big pictures should go day-and-date on Netflix.

The theatrical window was traditionally the first, followed by second-run theatrical, airline and hotel viewings, pay cable, and so on down the line. Now that households have fast web connections, streaming disrupts that tidy business model. In October Ted Sarandos, Chief Content Officer for Netflix (right, with Ricky Gervais), suggested that even big pictures should go day-and-date on Netflix.

“Why not follow with the consumer’s desire to watch things when they want, instead of spending tens of millions of dollars to advertise to people who may not live near a theater, and then make them wait for four or five months before they can even see it?” he added. “They’re probably going to forget.”

Exhibitors howled. Sarandos quickly recanted, saying only that he wanted people to rethink the current intervals between theatrical and ancillary release.

Some observers speculated that his October remarks were staking out an extreme position he intended to moderate in negotiations down the line–possibly to suggest that mid-budgeted pictures would be good ones to experiment with on day-and-date. Perhaps too Netflix was emboldened by the much-publicized remarks of Spielberg and Lucas in a panel last June, when they indicated that the future for most movies was VOD, with multiplexes furnishing more costly entertainments for the few. (In the same session, Lucas predicted that brain implants would allow people to enjoy private movies, like dreams.)

In any event, windows are already shrinking. In 2000, the average theatrical run was 170 days; now it’s about 120 days. With about 40,000 screens in the US, films play off faster than ever before. Video piracy, which makes new pictures available well before legal DVD and VOD release, puts pressure on studios to shorten windows. It seems likely that the windows and the intervals between them will shrink, perhaps allowing films to go to all video formats as quickly as 30-45 days after the theatrical release ends.