Archive for the 'Film technique: Sound' Category

Atmos, all around: A guest post by Jeff Smith

Today we have a guest entry by our friend and colleague Jeff Smith. Jeff teaches here at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the Film Studies area. He’s an expert on cinema sound, particularly music. His book The Sounds of Commerce: Marketing Popular Film Music is a trailblazing explanation of the ties between 1960s Hollywood and the music industry. It combines analysis of scoring with discussions of business decisions that shaped audience’s response to movie soundtracks. His forthcoming book is on how critics have understood the impact of the HUAC hearings and the Hollywood Blacklist, with emphasis on films that seem to comment on Cold War politics.

Jeff has written extensively on sound practices in contemporary American cinema. What better person to explain and analyze the newest sound technology in Hollywood movies?

Director Peter Jackson calls it “the completely immersive sound experience that filmmakers like myself have long dreamed about.” Mark Andrews, who made his feature film directorial debut with Pixar’s Brave, says, “It’s more 3D than 3D images.” “It” is Dolby Atmos, a new cinema sound system that promises to change the way you see and hear movies. Does it?

The buzz

Dolby Atmos made its debut with Brave at last year’s Los Angeles Film Festival. A handful of scenes from earlier films, including Rise of the Planet of the Apes and The Incredibles had been test-mixed in the new Atmos system for demonstration purposes. But Brave is the first film to use the new platform from start to finish.

If you haven’t heard of Dolby Atmos, you’re not alone. When Brave opened, there were only fourteen theatres in the country that were capable of showing the film in Atmos. These tended to be high-end movie theatres, such as AMC’s six Enhanced Theatre Experience venues, which typically charge a premium ticket price.

The list of theatres wired for Atmos has grown since then, but the number remains quite small. At this point, there are 37 theatres in the U.S. that feature Dolby Atmos, a tiny fraction of the country’s nearly 40,000 screens. A little more than a third of these theatres are located in California. Approximately another third are clustered in just five states: Florida, Illinois, New York, Texas, and Washington. Most of these theatres are in the suburbs of major metropolitan areas. True, the recently opened Palms Theatre in Muscatine, Iowa (population 22,886) incorporated an Atmos system in its XL Digital Auditorium, but presumably it was part of its building plan. For existing theatres, an upgrade carries a hefty price tag of between $30,000 and $100,000. So Dolby Atmos may not be coming soon to a theatre near you.

Yet more and more films are being mixed for Atmos. Dolby has announced that more than twenty films will feature the new platform in 2013, a significant increase over the twelve films distributed with this format in 2012. The roster includes three of the most eagerly anticipated studio tentpoles of the summer season: Paramount’s Star Trek Into Darkness, Pixar’s Monsters University, and Warner Bros. Superman reboot, Man of Steel. Still, does the new system justify the expensive theatre conversions and the higher ticket prices that will follow?

Two channels. Then five + one. Now, how about sixty?

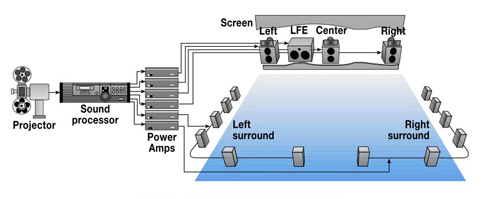

Dolby Digital Surround 5.1.

According to the Dolby website, Atmos grew out of the company’s efforts to introduce Dolby 7.1. For years, the flagship for Dolby’s digital surround sound technology was their 5.1 system. The digit 5 referred to the number of channels that could be used by sound mixers: three channels for speakers behind the screen (left, center, and right) and two channels for all the surround speakers that line the side and back walls of the auditorium (left surround and right surround). The .1 in 5.1 refers to the Low Frequency Effects channel (LFE) that sent sounds between 3 to 120 Hz to a subwoofer located behind the screen in the front of the auditorium. These low-frequency sounds trigger acoustic vibrations that add a kinesthetic kick to onscreen explosions and car crashes.

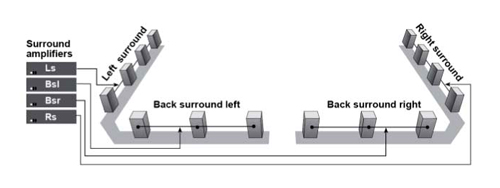

With Toy Story 3 in 2010, Dolby introduced two additional channels to their 5.1 platform. The 7.1 system subdivides the surround speakers. Instead of two channels for the surrounds (left surround and right surround), Dolby 7.1 offers sound mixers four channels (left side surround, left rear surround, right side surround, and right rear surround).

Dolby 7.1 came fairly late to the game, however. Sony already had introduced its own 7.1 system in 1993 with the premiere of John McTiernan’s Last Action Hero. Yet despite the eight-channel capability of Sony Dynamic Digital Sound, (SDDS), it never really caught on, largely because of the added expense of executing a 7.1 sound mix in addition to the standard 5.1 one. To date, more than 1400 films were mixed for the six-channel version of SDDS. Only 97 films received an eight-channel mix.

In the 2000s, Sony gradually began to phase out its 7.1 system. Filmmakers stopped building eight-channel mixes in SDDS in 2007. Moreover, about ten years after introducing SDDS, Sony stopped manufacturing decoders for SDDS content, citing decreased demand. SDDS had always lagged behind its competitors in the battle for screens, so Sony’s decision was not terribly surprising. Although new films continue to be mixed in SDDS to meet the needs of exhibitors that continue to use the system. Most theatre owners have replaced SDDS with one of Dolby’s systems. Sony promised exhibitors it would continue to make parts and service for current SDDS products available until 2014. But the electronics giant acknowledged that it was shifting its attention to digital cinema technologies that were already in development.

Considering Sony’s history and exhibitors’ reluctance to upgrade to an eight-channel system, it’s surprising that in 2010, Dolby would launch its own 7.1 counterpart. But maybe not so surprising, because Dolby’s new channels were differently placed. Sony’s 7.1 system had added channels to the speakers behind the screen. Instead of three front channels (left, center, and right), SDDS had five (left, left center, center, right center, and right). These extra sound sources probably made little difference to most moviegoers. Adding channels behind the screen made for smoother panning of sounds that seem to move across the space depicted in a shot, but it did nothing to increase the sense of spatial immersion.

In contrast, Dolby added its two extra channels to the surround areas. Its 7.1 platform treats the interior of the theatre as seven spatially distinct zones. The additional channels in the surround array enables mixers to position sound elements more precisely. This “zoning” of the surrounds offers mixers a wider variety of options for the placement of sounds, and it more closely approximates the way that sounds in real life come at us from several different directions.

Now Dolby Atmos pushes the premises of this aspect of Dolby 7.1 to the nth degree. While Dolby 7.1 makes a leap from six channels to eight channels, Dolby Atmos makes a leap from eight channels to sixty-four channels, a gigantic change from all of Atmos’ predecessors. Using the old nomenclature that described the sound platform as a ratio of speaker channels to LFE channels, we might call Dolby Atmos a 62.2 system! It offers more than sixty separate and distinct speaker channels as well as an optional channel for additional subwoofers located in the back corners of the auditorium. More importantly, with the vastly expanded number of speaker channels, Atmos enables mixers to position a single sound element in the theatre with unprecedented clarity and precision.

Say you have a screen door banging in the wind. In Dolby 5.1, if a mixer wanted to send that banging noise to the right surrounds, it went to every speaker in the array. In effect, it wouldn’t sound like a single door, but rather several doors banging in unison. In Atmos, however, if a mixer wants to position that banging sound in a particular part of the auditorium, he can treat it in a manner analogous to the way it would be heard in the real world. The sound is emitted from a single point of origin and is heard as a punctual effect rather than as aural ambience emanating from a broader area of the theatre.

All about the panning

Beyond its multiplication of channels, Dolby Atmos addresses certain limitations in earlier platforms. Simplifying a bit, we can say that for content providers Atmos is “all about the panning.” Atmos adds a couple of speakers on each side that are placed close to the screen to facilitate smoother pans for sounds that move from onscreen to offscreen.

The surround speakers in Atmos have a frequency range that closely matches that of the speakers behind the screen. This aspect of Atmos addresses a common complaint about more traditional digital surround systems. In those, the surround speakers have a narrower frequency range than the front ones. As a result, when sounds were panned from onscreen to offscreen, the audience could hear changes in timbre and fidelity. The extra subwoofers in Atmos ameliorate this problem since they help to “bass manage” the surrounds, thereby allowing sounds in them to have a much “fatter” low end.

Besides adding subwoofers to increase the number of LFE channels, theatre owners have the option of adding left center and right center channels to the speakers behind the screen. This allows for smoother pans of sounds made by characters or objects that move across the screen. In this respect, Atmos combines the best features of Dolby 7.1 and Sony’s eight-channel system.

Up in the air

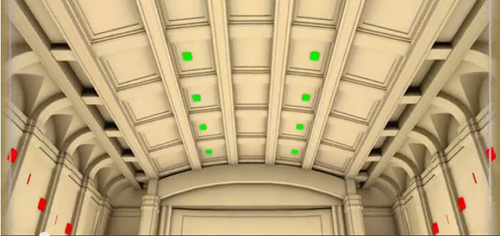

In platforms like Dolby 5.1, sound is situated almost entirely on one plane. The speakers behind the screen are at roughly the same height as are the surround speakers that line the sides and back wall of the auditorium. Dolby Atmos expands the auditory field by adding speakers to the theatre’s ceiling.

These additional speakers create an overhead sound plane, which enhances the sound mixer’s ability to localize sounds in the auditorium. In real life, of course, we hear all kinds of things overhead–bird calls, airplanes, building construction. Although mixers can use these ceiling speakers for sounds that are important in the story that unfolds onscreen, Dolby’s literature usefully reminds us that overhead ambient sound can enrich a film’s setting. A chirping cricket placed in one of the overhead speakers can convey the feeling of sitting at night beneath a forest canopy.

Admittedly, this new feature of Atmos technology merely represents a refinement of something filmmakers could do before. But previous sound technologies suggested an overhead sound plane through a psychological illusion. When the characters in Das Boot, for example, hear the pinging sounds of a British destroyer’s sonar system above their submarine, we might hear that sound originating above our heads. Yet its point of origin is no different from any other sounds that we hear in Das Boot.

Characters’ upturned gazes bias our response as we watch them anxiously awaiting the detonations of the depth charges released by the destroyer.

The extra surround channels and the overhead sources all create a more enveloping ambience and more punctual sound events—ultimately, a more realistic aural environment. Dolby’s innovations should be especially appealing for films projected in 3-D. Atmos, as its proponents note, offers a 3-D sound to match 3-D picture.

Is the recent popularity of 3-D cinema, though, the only factor in Dolby’s push to get more exhibitors on board with Atmos? Curiously, it comes right on the heels of Dolby’s introduction of its 7.1 system. Over the years, Dolby has continually pressed its R & D division to develop new sound technologies. But, in bringing both Dolby 7.1 and Atmos to the marketplace in about a two-year time span, I still have to wonder, “Why now?”

Backward compatibility

Fans of Atmos argue that it represents nothing less than a paradigm shift for cinema sound technology. That may prove to be true if more exhibitors decide to invest in it. But if we are witnessing a paradigm shift, it is one made possible by another paradigm shift, one of even greater historical import. I’m thinking here of the sweeping change that took place as theatres changed to digital projection.

David has written extensively on this topic, and you can find his account of this change in his e-book, Pandora’s Digital Box, a recasting of several blog entries under that name. Actually, the shift to digital projection didn’t demand Atmos. But it certainly made it possible.

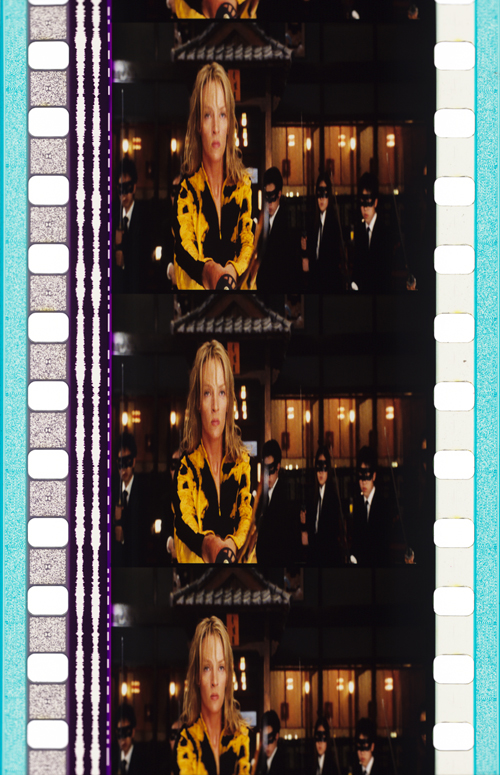

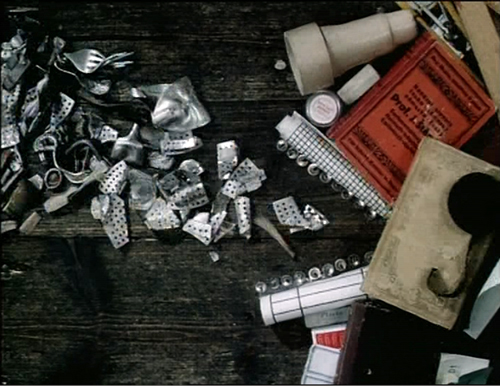

Look closely at a single frame of 35mm film. Like an archeological record, it preserves thirty-plus years of cinema sound innovation. Left of the picture area, you can see the twin optical sound stripes, encoded as wavy lines, that are used for older Dolby Stereo systems. Dolby continually refined its initial four-channel stereo system, ultimately introducing Dolby SR in 1986 as the last generation of its signature noise-reduction technology. (The SR stands for Spectral Recording.) These optical stripes on a 35mm print are still necessary for any theatre still using analog sound.

Just to the right of these optical stripes you can see dashed white lines used for DTS time code. DTS is a digital surround sound technology that uses compact discs to store and play back the film’s audio. The white lines maintain sync between picture and sound.

On the extreme left and right edges of the film strip, outside the perforations, is a speckled light blue stripe. That encodes the audio data for SDDS playback. The information in the two stripes is redundant, but that’s necessary because SDDS is decoded by a sound reader that mounts on the top of a 35mm projector. By putting the information on both sides of the frame, Sony’s design avoids any potential problems in threading the SDDS decoder.

Lastly, in between the sprocket holes on the left side, you can see the audio information for Dolby Digital. Like the SDDS stripes, these gray patches of Dolby Digital audio are encoded as data blocks that are read by a digital sound head. They send the information to a Dolby Cinema Sound Processor.

In our 35mm strip, a huge amount of audio information, along with the film image itself, is jammed into a space that’s less than an inch and a half wide. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, this “quad track” – that is, one analog system and three digital formats – proved to be very versatile. The audio could be played back in any theatre, regardless of the particular type of sound system that is used. The quad track allowed studios to avoid the distribution nightmare of having to match prints to screens using different audio systems. The one-size-fits-all approach also enabled multiplex exhibitors to move a print from one screen to another without worrying about compatibility.

But suppose we had to add another type of audio data to 35mm film, one that is capable of supporting more than sixty different audio channels. There just isn’t enough empty space on a 35mm print to make such an innovation possible. So even if Dolby’s engineers envisioned the potentiality of an overhead sound plane and of a cinema sound processor capable of supporting 64 different outputs, there was no practical way to add the audio information needed for Dolby Atmos and retain the compatibility offered by the quad-track 35mm.

Enter the Digital Cinema Package. With the large-scale conversion to digital projection, the prospect of innovating a system like Dolby Atmos suddenly took on new life. The audio files for Dolby Atmos are embedded in the DCP alongside the files for 5.1 and 7.1. Like the audio in 35mm film, the DCP is designed for maximum compatibility. The Dolby Atmos files are ingested into the theatre’s server along with all of the other audio and picture files found in a DCP. But for any theatre that is not wired for Atmos, the server simply ignores the Atmos files and uses the main audio track file for standard playback. More importantly, if there is any communication problem between the server and the Atmos sound processor, the system simply reverts to a Dolby Surround 7.1 or 5.1 mix, ensuring that a show can continue without delay. Even more impressively, the Atmos system even detects a damaged speaker or amplifier. Its flexible rendering system automatically works around the faulty component, sending the necessary audio data to other parts of the replay chain. So a show will continue despite a technical problem, and a narratively important sound effect or line of dialogue will not be lost due to a damaged speaker or amplifier.

The backward compatibility found in the Atmos system has long been an aspect of Dolby’s business strategy. When Dolby introduced its four-channel Stereo technology in 1975, it did so in a way that accommodated the needs of theatre owners who wanted to retain their existing sound systems. Dolby Stereo used a matrix system that mixed four channels of audio information down to the binaural optical stripes found on a standard 35mm print. After the projector’s sound head read these optical soundtracks, the information contained in them was then sent to a sound processor that “unpacked” the binaural stereo and sent the signals to the appropriate speakers in the auditorium. Dolby’s matrixing system, though, was prone to certain amount of cross-talk between the screen channels, and it occasionally caused a sound to be sent to the wrong output in the four-channel mix.

As a company concerned about backward compatibility, Dolby was willing to live with trade-offs. On one hand, the Dolby matrixing system avoided the kinds of format complications found in multi-channel systems that used magnetic striping. On the other hand, because of the potential for bleed between channels, some sound editors were reluctant to experiment with directional sounds in Dolby Stereo mixes. In practice, the surround channel in Dolby Stereo was reserved mostly for ambient noise, things that added texture to a film’s aural environment but that did not flaunt the precise directionality made possible by multi-channel playback.

Sound historians Jay Beck and Mark Kerins point out that such timidity has also characterized a good deal of sound work in the Digital Surround era. Contemporary sound designers strive to create immersive audio environments for films, but they also opt not to localize specific sounds that would draw our eyes away from the screen. In particular, designers shy away from assigning sudden loud sounds to the rear surround channels. Because the sound originates behind the audience, viewers are likely to be startled, which can be inappropriate to the mood of the story. Worse, the audience may turn to see what caused the unexpected noise. This is called the “exit-door” effect, because it pulls the viewer out of the story as if somebody had slammed the emergency exit.

Sound editors are much bolder about localizing individuated or punctual sounds in an Atmos mix. With 64 different channels to play with, Atmos offers myriad possibilities for audio experimentation. For content-providers, Atmos presents a “brave new world” for cinema sound. But this leads to a larger question: What is it like to see a film in Atmos?

Multi-channel sound with a Scottish lilt

While I was in Los Angeles last August doing research, I decided to spend a sunny Sunday morning at the movies. The City of Angels has a bevy of terrific movie theatres showing Hollywood’s latest, but the choice was easy. I headed to see Pixar’s Brave at Hollywood’s El Capitan Theatre, then one of only ten theatres in the country wired for Dolby Atmos.

El Capitan opened in 1926 as one of three theatres run by legendary showman Sid Grauman. Unlike Grauman’s nearby Egyptian and the famous Chinese Theatre, El Capitan was a venue for live performances. After a decline in attendance in the late 1930s, El Capitan was refurbished and reopened as the Hollywood Paramount Theatre. For several years, it remained a flagship for Paramount Pictures until the late 1940s, when the U.S. Supreme Court and the Justice Department forced all of the studios to divest their exhibition holdings. Until 1991, El Capitan was owned and managed by a series of different companies, including the Pacific Theatres Circuit.

That all changed in the late eighties when Disney offered to lease El Capitan from Pacific Theatres with an eye toward using it as a venue for premiering new films. Disney spent millions restoring the theatre’s original décor, although it seems to have been “imagineered” into a faux 1920s picture palace, complete with a Mighty Wurlitzer organ. Disney also restored El Capitan’s original name perhaps in an effort to sever the theatre from its earlier associations with Paramount. El Capitan is now Disney’s own flagship theatre in Hollywood and is fully integrated with their other businesses. Indeed, the Sunday morning that I attended Brave I was surrounded by families visiting it as one of the stops in Disney tour packages.

As a premium venue, El Capitan offers much more than your usual movie experience. As I walked in to find a seat, a talented organist played a medley of songs from classic Disney films, like Pinocchio’s “When You Wish Upon a Star,” and from more recent titles, such as Toy Story’s “You’ve Got a Friend in Me” and The Lion King’s “Circle of Life.”

There was plenty of other pre-show entertainment.: a couple of trailers, a brief light show, and song and dance numbers featuring costumed Disney characters. Unlike the organ medley, though, these live performances did not use music from Disney films, but instead drew from the Great American songbook. Mickey and Minnie danced to Astaire-Rogers tunes, followed by patriotic songs, including George M. Cohan’s “You’re a Grand Old Flag” and “The Yankee Doodle Boy.” The program culminated with a short medley of Scottish songs that introduced Disney’s newest princess, Merida.

This final number provided a more or less seamless segue into the start of Brave.

I didn’t know quite what to expect from the film, which has hailed as a change of pace for Pixar, a company that had developed a reputation for targeting a “family film” demographic centered on pre-teen boys. Despite the fact that Pixar had broken new ground with the film’s red-haired, tartan-clad heroine, Brave received middling reviews. By August, it was perceived as a bit of an underperformer, having earned “only” half a billion dollars worldwide. (Such is the high bar set by Pixar titles.)

I quite enjoyed Brave, not least because it was in Atmos. For the most part, Atmos lived up to the hype, offering a sonic experience that was unlike anything I’d heard in theatres before. In a way, Atmos simply refines things that could be accomplished in Dolby 5.1 or 7.1. Yet certain moments of Brave lived up to the promise of a fully three-dimensional sound that matches a film’s 3-D images. I’m not an audio engineer or sound technician. I’m really just a guy who likes going to the movies, albeit one who is a tad more attuned to the vagaries of digital surround sound mixes. So I’m offering some “in the moment” impressions of the Atmos system. If I’ve made any grievous errors in description, chalk it up to either faulty memory or the power of cognitive illusion.

I first became aware of Atmos as something different early on during a rather ordinary scene in which Merida receives “princess training” from her mother. As Merida recites a poem, the Queen, standing above her, instructs her to project her voice saying, “Enunciate! You must be understood from anywhere in the room or it’s all for naught.”

Cut to Merida. When she replies under her breath, “This is all for naught,” the Queen shoots back “I heard that!”

During this brief shot that holds on Merida, Emma Thompson’s mellifluous response as the Queen issues from one of the left rear surround speakers.

The localization of the Queen’s voice creates a brief “point of audition effect” as it realistically places us in the middle of the diagonal space that separates Merida from her mother. The moment also playfully demonstrates the Queen’s instruction to Merida to be heard from “anywhere in the room.”

Another example of Atmos’ innovative use of offscreen sound occurs during the family dinner scene in which Fergus is retelling the story of his confrontation with Mordu. After Merida sits down at the table, Fergus is about to take a bite from a leg of poultry. At this moment, we hear the sound of barking dogs swiftly panned through the right side surround speakers in the auditorium.

The dogs then burst into the frame from off right.

The use of spot sound effects in the surround speakers is quite conventional, but the panned barking had a smoothness and swiftness that I had not heard before.

This moment is interesting for another reason. Although this is admittedly a bit speculative, I believe it showcases Atmos’ ability to exploit a kind of aural correlate of the Phi Phenomenon. The Phi Phenomenon refers to an optical illusion involving the movement of light. Gestalt psychologist Max Wertheimer noticed in experiments conducted in the early 1910s that when two lights were flashed on and off rapidly enough, subjects saw them not as two flashing lights, but rather as a single light that appeared to move back and forth. Many neon signs exploit this perceptual illusion.

The same is true of this rapidly panned sound in Dolby’s Atmos, which is made possible by the system’s “pan-through array.” Because the sound editor can use positional metadata to send the sound of the bark to each of the right side surround speakers for just a couple milliseconds of time, our mind does not hear it as a group of fragmented sounds, but instead hears it as a single sound that zips through the space of the auditorium.

Later, while galloping in the woods, Merida finds herself thrown into the middle of a Stonehenge-like circle. As Merida gets her bearings, we hear a breathy, echoey, high-pitched sound coming from one of the right surround speakers. Cueing us by Merida’s glance into the space off right, director Mark Andrews cuts to a shot over Merida’s shoulder that shows a blue wisp off in the distance.

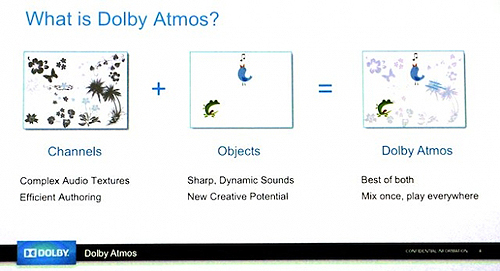

The use of a sound effect in the surround channels to steer our attention to offscreen space may be one of the most conventional aspects of digital sound aesthetics. Yet this moment is a bit unusual. It positions one localized sound effect against a bed of ambient sounds that are sent to all of the speakers in a geographical zone. In fact, this is an aspect of Atmos that Dolby showcases to content-providers. Unlike systems that are wholly channel-based, Atmos allows sound editors to locate a single sound effect in an individual speaker at the same time that other groups of sounds are fed to the system as a channel-based submix. The combination of “beds” and aural objects is captured in a visual diagram provided by Dolby.

The graphic of the bed shows a variety of gray-colored flora and fauna. The aural objects are represented as a green frog and a blue songbird. When the two images are combined, the green frog and blue bird stand out as individually colored objects set off against the bed of gray background elements. Background and foreground effects can all be developed individually and then blended at a later stage of postproduction. Atmos refines the creative possibilities found in other digital surround sound systems in a way that preserves current workflows.

Up until now, I have not said much about Atmos’ ability to exploit an overhead plane of sound. This may strike you as a bit curious since the legendary sound designer, Gary Rydstrom, discussed this aspect of Atmos in the Hollywood Reporter as one of the technology’s most appealing features. Describing a scene where Merida goes to retrieve an arrow that she has launched, Rydstrom says:

You hear the arrow ‘swish’ go through the theatre and land way back behind the audience. Then she goes into the forest. I love putting sound in the ceiling, things like scary forest birds. For a little girl, the forest feels even taller and more imposing if you can have weird sounds way up high.

Rydstrom’s description beautifully captures the way this moment from Brave works onscreen. Yet because I had read his comments before seeing the film, it was a little less powerful than some other events on the overhead sound plane. A moment I found more striking comes when the queen realizes that a magic spell has turned her into a bear. The bear flails about the room, ultimately falling backward onto her four-poster bed.

After falling through the bottom of the bed, the bear then bolts upright to smash through the canopy. Aurally, this moment is rendered as a loud crash located in the speakers suspended from the ceiling. The placement of the sound beautifully punctuates the bear’s sudden upward thrust, adding a sonic punch to the sight gag.

Probably the most vivid demonstration of Atmos’ capability comes in a scene in which Merida is caught in a thunderstorm. Sitting in the balcony of El Capitan, I felt pulled into the thick of events unfolding onscreen. If you shut your eyes, you could almost feel the patter of raindrops, the whoosh of the wind, and the violent clamor of thunderclaps.

Admittedly, such scenes can seem pretty powerful in a theatre using a more conventional digital surround system. A Dolby 5.1 or 7.1 mix can create comparable aural immersion by simply sending submixes of the storm’s sounds to different zones within the theatre. I suspect that the impact of the Atmos mix came less from its ability to isolate particular sound effects than it did from the additional subwoofers placed in the back corners of the theatre. With three subwoofers, loud sounds seem flung at you from all directions. Thanks to the additional LFE channel, the sound waves from those thunderclaps triggered even stronger shakes and rumbles. (The extra subwoofers also enhanced Mordu’s ferocious roars during the epic confrontation, shown up top, that resolves Brave’s plot.) The overhead speakers also played a subtle role in creating the feeling of being caught in a storm. The sense of a three-dimensional environment is undoubtedly heightened by the sound of rain droplets falling and spattering above one’s head.

Is Dolby Atmos the great leap forward for cinema audio that its proponents claim? The answer depends upon the weight you place on potentiality vs. established practice. Atmos definitely creates opportunities for precise placement of sounds in the auditorium. That in turn offers new prospects for audio/visual coherence. As Dolby puts it in the white paper: “If a character on the screen looks inside the room toward a sound source, the mixer has the ability to precisely position the sound so that it matches the character’s line of sight, and the effect will be consistent throughout the audience.”

Yet the specific purposes to which Atmos was put in Brave – the use of spot sounds to activate offscreen space; the use of surround speakers for panned or moving sounds; the creation of a immersive, 3D aural environment; the use of loud noises to viscerally impact the audience – are all things that its predecessors accomplished, going all the way back to Dolby’s pioneering four-channel system. Atmos does these things either a little better or a lot better, depending upon the specific system you’re comparing it with.

Perhaps my description of Brave suggests that the advantages of Atmos are more subtle than spectacular. Perhaps you feel that contemporary movies are sound-polished enough already. If so, Atmos probably won’t hold much appeal for you as a moviegoer.

The bigger question for me is whether it will be widely adopted by theatre owners. A key aspect of Dolby’s sales pitch for Atmos is that it is scalable to almost any size of theatre. If your theatre is too small for a 62.2 configuration, you can reduce the speaker array and get some of the benefits of Atmos’ improved surround definition and overhead sound plane. Dolby says its minimum configuration for Atmos is 9.1. But if the best that you can do for your theatre is 9.1, then perhaps Dolby’s 7.1 system is a more sensible option.

The exhibitor’s ability to mix and match components in Atmos was something I experienced firsthand during a recent visit to the ShowPlace ICON in Chicago. The ICON has two screens wired for Atmos, but those auditoriums weren’t equipped with the optional subwoofers that were in the system at El Capitan. Why? With two additional subwoofers, there is increased risk of sound bleeding over to the neighboring auditoriums of a multiplex. This wasn’t a problem for El Capitan, a huge, standalone theatre.

In any case, the costs to upgrade all the screens in a multiplex would be prohibitive, particularly at a time when many theatre owners are still smarting from expenditures of converting to digital projection. For that reason, Atmos may be introduced as 3D was, with one or two screens per venue at first. The decision to do an Atmos upgrade may devolve upon the question of what particular sound system is good enough to meet the needs of both theatre owners and patrons.

Yet the threshold for “good enough” is not static, and theatre owners may find themselves under increasing pressure as home theatre technologies become ever more sophisticated. If Quentin Tarantino is right that watching digital projection in a movie theatre is like watching a giant television screen in someone’s living room, then Atmos really offers exhibitors something to differentiate the multiplex from the home theatre. With 4K televisions already showing up at big-box retailers, cinema audio may provide exhibitors with the best means of luring movie fans out of their living rooms. After all, are you really ready to deploy a couple of dozen speakers around your walls and from your ceiling?

At several points in this post, I cited information made available in a white paper prepared by Dolby that explains the key features of Atmos to content providers and exhibitors. Additionally, Dolby’s website offers lots of other information about their Atmos system: a list of theaters wired for Atmos, a roster of films mixed in the process, and a short video explaining some of the differences between Atmos and other systems.

Information about Brave in Atmos can be found in two articles published by The Hollywood Reporter that are available here and here. There’s also a video interview with Brave’s sound design team. A brief history of the El Capitan can be found on the theatre’s website.

Film scholars Jay Beck and Mark Kerins both have written excellent histories of Dolby’s Atmos’ predecessors. Beck’s 2003 Ph.D. dissertation, “A Quiet Revolution: Changes in American Film Sound Practices, 1967-1979,” offers a terrific account of Dolby’s innovation of its pioneering four-channel stereo system. For a sampling of Beck’s analysis of Dolby Stereo aesthetics, see his essay, “The Sounds of ‘Silence’: Dolby Stereo, Sound Design, and Silence of the Lambs” in Lowering the Boom: Critical Studies in Film Sound, coedited by Beck and Tony Grajeda. Kerins’ work, on the other hand, focuses more squarely on Dolby 5.1 and what he calls a “digital surround sound style.” See Kerins’ Beyond Dolby (Stereo): Cinema in the Digital Sound Age.

For more on Atmos, see Eric Dienstfrey’s excellent explanation on our UW media blog, Antenna.

Wanda, the biggest cinema chain in China and purchaser of the AMC chain in the US, recently announced a major commitment to Atmos in its Mainland cinemas.

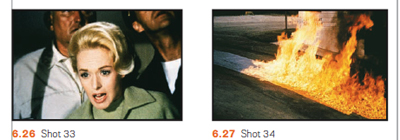

Sir Alfred simply must have his set pieces: THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO MUCH (1934)

The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934).

DB here:

Hitchcock made six remarkable thrillers from 1934 through 1938, and I have long believed that the first one was the best. I think very well of Sabotage, and both The Lady Vanishes and The 39 Steps are strong contenders. But for me, The Man Who Knew Too Much has got damn near everything going for it.

I came to it a little late. It wasn’t the first Hitchcock I wrote about; that was Notorious, in a 1969 piece that nakedly reveals the limitations of a college senior’s knowledge. Nor was it the first Hitchcock I saw; that was Vertigo, when I was about ten. Inauspiciously for me, when Vertigo was revived for national television broadcast in 1972, I was flying to a job interview in Madison, Wisconsin.

I got that job, though, and soon The Man Who Knew Too Much became very important for me. Seeing it at a film society screening, I was bowled over. Then I discovered that it was available for purchase in a cheap 16mm print. I bought a print and began teaching the film as a model of narrative construction. It worked its way into the first edition of Film Art, in 1979 and hung around there for several editions.

That sample analysis has been available as a pdf on our site, but check it out at the Criterion site, where it’s enhanced with nice frame enlargements and a major extract. The essay makes my case for the movie as an extremely well-constructed piece in the classical storytelling tradition.

So I was the ideal consumer for a spruced-up DVD/ Blu-ray release, and as usual Criterion doesn’t disappoint. It’s a handsome version, with some fine supplements. We get two rare interviews with Sir Alfred from CBS’s arts program Camera Three (featuring Pia Lindstrom and William K. Everson) and a perceptive discussion with Guillermo del Toro, who makes a vigorous case for the film. So does Philip Kemp in his commentary, which is strong on production background. Kemp offers valuable information on script versions and on Hitchcock’s niche in the English industry. The accompanying booklet includes a lively appreciation by The Self-Styled Siren, aka Farran Smith Nehme.

So I was the ideal consumer for a spruced-up DVD/ Blu-ray release, and as usual Criterion doesn’t disappoint. It’s a handsome version, with some fine supplements. We get two rare interviews with Sir Alfred from CBS’s arts program Camera Three (featuring Pia Lindstrom and William K. Everson) and a perceptive discussion with Guillermo del Toro, who makes a vigorous case for the film. So does Philip Kemp in his commentary, which is strong on production background. Kemp offers valuable information on script versions and on Hitchcock’s niche in the English industry. The accompanying booklet includes a lively appreciation by The Self-Styled Siren, aka Farran Smith Nehme.

Interest in Hitchcock seems to be the one constant in the whirligig of tastes in film culture. He is a mainstay of home video and cable television; apparently the films can be re-released in perpetuity. Professors love to teach his films. The techniques are obvious and vivid, and the films offer a manageable complexity that encourages interpretation. Class, gender, power, the law—whatever your favorite themes, they’re all on the surface, yet enticingly ambivalent. Not to mention how much fun these movies are to watch. I’ve always enjoyed introducing “lesser Hitchcock” like Stage Fright and Dial M for Murder and then watching the audience fall under their spell.

Critics navigate by Hitchcock as a fixed pole star. Reviewers compare every new thriller to the classics of The Master of Suspense. Just look at what people write about Soderbergh’s Side Effects. And for those who promoted the auteur approach to Hollywood cinema, Hitchcock was a beachhead. Who could doubt that this man turned out personal projects within the impersonal machine known as Hollywood? And if he could do it, why not Ford, Hawks, Sternberg, Ray, and all the rest? Hitchcock nudged skeptics down the slippery slope toward auteurism.

Even if Hitchcock isn’t to your taste, you can’t avoid his influence. That became obvious around the 1970s, when directors began borrowing from him more or less overtly: Spielberg’s Vertigo track-and-zoom in Jaws (now itself a convention), De Palma’s homages/pastiches, Polanski’s use of point-of-view in Repulsion and Rosemary’s Baby, the endless Psycho sequels and the van Sant remake, and the rest. But Hitch was no less influential in his own day; I’d argue that filmmakers of the 1940s had to raise their game if they wanted to meet the challenge of Rebecca, Foreign Correspondent, Suspicion, Shadow of a Doubt, Spellbound, and Notorious. Billy Wilder told a reporter that Double Indemnity was his effort to “out-Hitch Hitch.”

What was so special? Obviously, the throwaway humor—sometimes airy, sometimes slapstick, sometimes sardonic. And obviously a gift for switching situations around, playing them against cliché, setting us up for a jolt. But I think there’s something else afoot. Part of the Master’s repute rests on virtuosity of film technique. Hitchcock makes movie movies, even when, like Rope or Dial M, they seem “theatrical.” And this movieness is best seen, I think, by considering a term that always comes up with Lord Alfred: the set piece.

Maintaining a tradition

Hitchcock held onto the flamboyant expressive devices of silent and early sound cinema far longer than any other director. For decades he kept alive techniques that many directors thought were old hat: abrupt cuts to details of gestures and objects; blurry point-of-view images to suggest distraught or befuddled states of mind (as above); very brief insert shots to accentuate violence. Compare Battleship Potemkin with Foreign Correspondent’s assassination scene.

Hitchcock built entire films around classic silent techniques. The Kuleshov effect governs Rear Window; the German “entfesselte” or “unchained” camera dominates Rope and Under Capricorn. Rope and Dial M revive the aesthetics of the German kammerspielfilm, or “chamber play.” The Germanic look was alive and well in the spiderweb shadow-work of Suspicion, while both French Impressionism and German Expressionism inform the dream sequences of Spellbound and Vertigo. He also preserved the “creative use of sound” that was the hallmark of directors like Clair and Milestone. While others had pretty much given up the expressionistic use of music and effects, Hitchcock was always ready to draw on them. The hallucinatory Merry Widow Waltz haunts Shadow of a Doubt, while Hitchcock’s penchant for giving us two pieces of information simultaneously, one in the image and another on the soundtrack, let him design scenes visually and push a lot of dialogue offscreen.

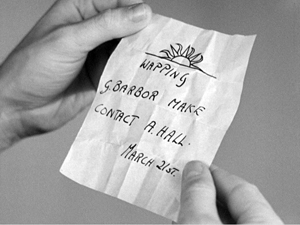

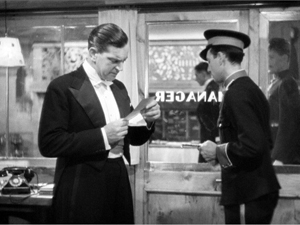

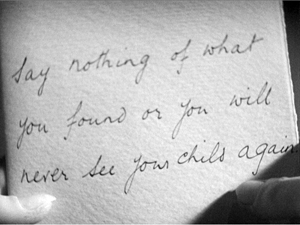

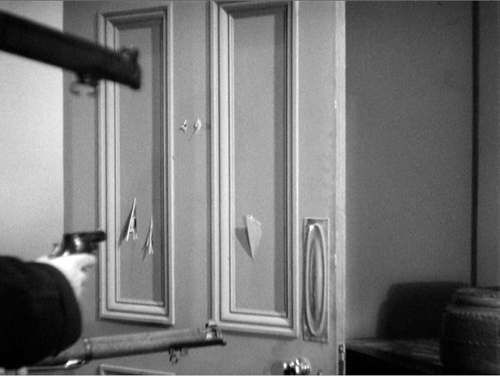

This flexibility of technique modulates from scene to scene. In The Man Who Knew Too Much, note-reading is presented in three ways, in rapid succession. First, Bob finds Louis’ note in the hairbrush.

Soon Bob gets a message from the front desk. What does it say? Hitchcock hides that by, for once, not supplying subjective point of view.

Only when the note is passed to Jill do we get to see it, but with a twist. Nobody but Hitchcock would add an extra shot that cuts to the note in her hand without revealing what it says.

That extra shot is what Eisenstein called a primer; as with dynamite, you need a little charge to trigger the blast.

We often forget that classic silent directors used their pictorial techniques for suspense. Lang’s Mabuse films and Spione furnish plenty of instances, but so do the Soviet montage films. The scene in which the police wait for the worker to return to his wife in The End of St. Petersburg now looks like pure Hitchcock, and of course the Odessa Steps sequence was the Psycho shower of its day. So it isn’t surprising that Hitchcock would turn his silent-film virtuosity toward creating scenes of high tension and threatened violence. Nor is it surprising that his skills would crystallize in “set pieces.”

Everybody talks about Hitchcock’s fondness for set pieces. It’s part of his brand. We have the Statue of Liberty climax in Saboteur, the milk carried up the staircase in Suspicion, the milk-and-razor scene and the final suicide in Spellbound, the spectacular rescue of Alicia at the end of Notorious, and the efforts of Bruno to retrieve the lighter in Strangers on a Train.

But, come to think of it, what makes something a set piece?

Game, set piece, match

Foreign Correspondent (1940).

As commonly understood in the arts, a set piece is a fairly self-contained portion of a larger work. It has a distinct beginning and end, and it’s understandable and impressive if extracted from its original. It’s designed to be a bravura display of concentrated virtuosity. In music, an example would be an operatic aria like the Queen of the Night’s in The Magic Flute: it is so flashy and complete in itself that it can enjoyed on its own, in a concert setting.

Two early uses of the term shed light on its implications. In stage parlance, a “set piece” is an item of the set that can stand alone, like a gate or fake tree. In pyrotechnics, a “set piece” is a carefully patterned arrangement of fireworks; here again, it implies a display that dazzles the audience.

In the silent era, I’d suggest, the clearest exponent of set pieces is Eisenstein, who became known as “the master of the episode.” Many of his big scenes, like the Odessa Steps massacre, are developed at such length that they function as mini-films. But you can consider passages in Chaplin and Keaton as set pieces—the dance of the breadrolls in The Gold Rush perhaps, or the windstorm in Steambout Bill, Jr. The musical would seem to be a natural home of the set piece, with numbers standing out against more mundane scenes. In modern cinema, again under the aegis of Hitchcock: De Palma offers plenty, and perhaps the prize fights in Raging Bull constitute a string of them. Today the home of the set piece is the action picture; the chases and fights are the main attraction, and the genre challenges directors and crew to find new ways to intoxicate us.

The aesthetic of the set piece implies that some scenes function as filler while others get the whipped-up treatment. If that’s right, many great directors don’t favor mounting set pieces. Ozu, Mizoguchi, Dreyer, Hawks, and others present what we might call “through-composed” films. Just as Wagnerian opera and its successors minimized set pieces, these filmmakers create a surface texture that doesn’t create self-contained high points. (I grant you that the immolation of Herlofs Marthe in Dreyer’s Day of Wrath might count.)

Given the detachable quality of set pieces, it’s true that some of Hitchcock’s can seem implausible or gratuitous. How essential is Guy’s lighter to any plausible scheme of Bruno’s? If you want to kill Roger Thornhill, why send him to a crossroads in Midwest corn country? (A knife in the back on the Greyhound is more reliable.) It was this tendency to sacrifice story logic for stunning anthology bits that Raymond Chandler deplored:

The thing that amuses me about Hitchcock is the way he directs a film in his head before he knows what the story is. You find yourself trying to rationalize the shots he wants to make rather than the story. Every time you get set he jabs you off balance by wanting to do a love scene on top of the Jefferson Memorial or something like that.

Chandler has a point. How do you integrate a set piece into a whole movie? (I’ll make some suggestions shortly.) But first, give Hitch his due. For him, I think a set piece was a compact repository of inherently cinematic ideas carried to a limit within a sequence. A set piece is a challenge: How much can you squeeze out of a situation?

Go back to Foreign Correspondent. Setting an assassination in Amsterdam allowed Hitchcock to integrate the idea of a clue based on a waywardly turning windmill. So far, Chandler’s objection seems tenable: The windmill is just a gimmick. But once Hitchcock sets his hero exploring the lair, he can create a set piece that answers a question that no one ever thought to ask before: How do you eavesdrop in a windmill?

Johnny Jones has to evade the killers by crawling up alongside the giant gears, then down, then up again. At each step he barely escapes being spotted. When he seems safe, his topcoat gets snagged in the grinding gears, so he has to slip his arm out of it—just in time to avoid being crushed.

Yet once Jones is freed from the coat, it’s carried around the gearwork and might be spotted by the gang. And the old diplomat upstairs, mind hazed by drugs, is likely to reveal Jones’ presence. Hitchcock squeezes seven minutes of suspense out of all this, with a casual air that suggests: Of course, dear chap, any director worth his salary can see that a windmill harbors all kinds of excruciating menace. All in a day’s work, you know.

A whispered terror on the breeze

If anything is a set piece, the Albert Hall sequence in The Man Who Knew Too Much is. Philip Kemp’s commentary for the Criterion DVD considers it Hitch’s first, although aficionados would probably consider the “knife” sound montage of Blackmail at the very least a rough sketch for what would come. Lucky you: The entire Albert Hall sequence is excerpted on the Criterion site.

A set piece benefits from a simple premise. Here, Jill’s child is being held hostage, which keeps her from informing the police of what little she knows about the plot. We know that during the concert an assassin will try to shoot a diplomat.

You can imagine Chandler asking: Why plug Ropa during a concert, with all those witnesses? Why not when the target is on the sidewalk, shot from a rooftop for easy escape? You can hear that bland replying murmur: Raaaymond, it’s only a moovie…

So we have some conditions for a set piece: a compact piece of action limited in time and space. But there’s also a strong time marker. Ramon the assassin is to wait for a dramatic pause in the score; it’s followed by a shattering choral outburst that will muffle the pistol shot. We’ve been given a rehearsal of the passage in a gramophone record, but since we don’t hear the whole piece then, we can’t predict exactly when the chorus will hit its peak.

Hitchcock magnifies this uncertainty by letting the piece, Arthur Benjamin’s Storm Clouds Cantata, play out in its entirety. Its combination of lyrical and dramatic passages blend into a stream of music that coincides with the emotional action onscreen. I suspect that the piece, composed specifically for the film, glances at the most celebrated new choral piece of the era, William Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast (1931). It too has a charged dramatic pause followed by a tremendous choral blast: “Slain!” You can listen to it here, and you can hear some of the musical affinities at 27:11 and after.

So the self-contained quality of the sequence is enhanced by the unfolding soundtrack, as well as its “bookend” structure: Jill arrives at the Albert Hall/ Jill leaves. (Hitchcock was very fond of this coming-and-going bracketing; many scenes of The Birds are built out of this.) But to be a set piece we need virtuosity too, right?

As our Film Art essay indicates, Hitchcock structures the scene using nearly every technique in the silent-cinema playbook. We get dynamically accentuated compositions, crisp point-of-view editing, subjective vision (even blurring as Jill drifts into a panicky reverie), and suspenseful crosscutting back to the gang holding Bob and Betty prisoner. The techniques build to their own crescendo, with more and shorter shots of Jill, the orchestra players, and the curtain concealing Ramon. As the climax approaches, details of the players’ performance pass in a flash. As another layer, though, all these visual techniques are synchronized with the musical structure of the piece. Most obvious is the slow tracking shot back from Jill as the female soloist launches in:

There came a whispered terror on the breeze./ And the dark forest shook.

The text has always teased me, because in my early years of studying the film I couldn’t hear everything there. Now that the Storm Clouds Cantata has become a minor concert piece, we have a full version of the text. It’s the description of an especially ominous storm, one that drives birds away and makes trees tremble in fear. The only creature left, vulnerable to the gale, is a child:

Around whose head screaming/ The night-birds wheeled and shot away.

The orchestral and choral forces mount on the line that has always come through the sound mix:

All save the child—all save the child.

The line is ambiguous. Its literal sense is that all the creatures have fled the oncoming storm except the child (“all save the child”). But Hitchcock’s cutting and the film’s overall context leave it as an imperative: the child must be rescued. Thus the musical dynamics and the text stress, for us and presumably for Jill, that Betty’s safety depends on what she does.

Soon the cantata’s text finds another analog in the concert hall. The choir sings of the storm clouds finally breaking and “finding release.” That phrase, repeated with rising intensity, yields the dramatic pause and then the final outburst that is to cover Ramon’s pistol shot. But now we have to see this phrase as prophecy and comment: Jill’s scream during the pause is the release of her tightened anxiety. And of course the line slyly signals the release of the suspense built up through the whole sequence.

With Hitchcock, you always get more.

In all, the sequence becomes exactly what a set piece ought to be: compact, with sharp boundaries and a strongly profiled arc of interest, elaborated with a great variety of technical resources and a thrusting emotional impact. But is it too much of an independent sequence? One can imagine Chandler worrying that Hitch doesn’t care much about how to hook it up with everything else. Let’s see.

This scepter’d isle

There’s no doubt that a plot driven by set pieces can seem episodic, just a matter of pretty clothes clipped to a slender line. In action movies it’s a classic problem, which, say, Speed doesn’t fully solve but Die Hard does.

You can mask an episodic plot, though, through some stratagems. First, make your filler material charming. The Man Who Knew Too Much gives us comedy in the dentist office and in the Tabernacle, with Bob and Clive mumbling messages through hymnody. You can also whisk the audience from scene to scene so quickly that the viewer has to concentrate on local connections. This is one purpose of what I’ve called the hook, the transition that smoothly links the end of one scene with the beginning of the next. If you’ve got some plot holes, strengthen your hooks–especially those that hide your gaps.

The Man Who Knew Too Much has some nifty hooks. I especially like the way the fingers pointing to the bullet hole are followed by a shot of Ramon’s head: effect and cause neatly given by a straight cut. Then there’s the contrast of the fire in the fireplace dissolving to the skier pin, a sort of thermal hook. But probably the most memorable one is Betty’s line about Ramon’s brilliantined hair.

This hook is a motif as well, and recurring images or sounds like this can help knit together your movie. In Foreign Correspondent, we get hats and birds in various scenes. Here, as our Film Art essay indicates, teeth, the skier pin, sharpshooting, the cantata’s main theme, and other motifs weave through the overall structure of the film.

You can as well knit your big scenes together through certain narrative patterns, such as a trip or a search, both strategies that Hitchcock employs in many movies. In The Man Who Knew Too Much, Bob’s investigation of the gang follows the menu set out in Louis’ note: the sun emblem, Wapping, G. Barbour, and A. Hall. This serves as a sort of map for the middle act of the film. Once Bob has cracked the message, though, the film shifts into a new register. Jill, who has been waiting passively at home, takes over the role of protagonist. And her actions will fulfill another motif: that of interruption and distraction.

The film begins with Betty’s dog disrupting Louis’ ski jump. That’s an innocent accident, as is the moment when Jill nearly spoils Roman’s skeet shooting. But soon afterward Abbott’s chiming watch deliberately breaks Jill’s concentration, making her lose the shooting match. In effect the Albert Hall sequence offers payback: With her scream Jill not only disrupts the performance but spoils Ramon’s aim as Abbott had spoiled hers.

The Albert Hall sequence fits into the film in a less obvious way, one that plays along the thematic dualities that marble the movie. Throughout the film contrasts “Englishness” with “foreignness,” the latter split between allies (Louis, Ropa) and enemies. The Storm Cloud Cantata and what follows represent a sort of triumph of England over her adversaries.

At the St. Moritz resort, the Lawrence family is set off from Louis, their French friend, and two men: Abbott the German and Ramon the Latin. (He’s handily fudged; he has a Spanish name but calls the English “extraordinaire.” And his hair is greasy.) “Sworn enemies, eh?” Jill says half-humorously to Ramon before losing the skeet shoot. After Louis’ death Bob is at a loss in the hotel, unable to speak German or Italian, and distracted while Betty is kidnapped. The English aren’t at home in this world.

Once Bob and Jill have returned to London, they join the family friend Clive, a Wodehousian upper-class twit but gifted with loyalty and tenacity. Bob and Clive have learned from Gibson of the Foreign Office that the gang intends to assassinate the diplomat Ropa. They must tell what they know; the killing could prove as catastrophic as the assassination that triggered the war of 1914-1918. Yet Bob keeps mum. He might be enacting E. M. Forster’s dictum: “If I had to choose between betraying my friend and betraying my country, I hope I would have the guts to betray my country.”

The conflict between family love and civic duty is played out in the rest of the second act, when the men’s investigation takes them to a working-class neighborhood of Wapping. There, we learn that behind respectable English institutions—a dentist, eccentric religion—foreign elements lurk. Bob has solved Louis’ riddle, but at the cost of becoming another hostage. Bob and Betty re-meet, in a characteristically subdued stiff-upper-lip encounter that denies Abbott the tearful scene he expected. The dignity with which Bob conducts himself, asking about Betty’s dressing gown and her school grades while staring defiantly at the gang, leaves the others abashed.

Clive has escaped, though, and has managed to send Jill to the Albert Hall. That musical set piece initiates the film’s climax dramatically but also thematically. For one thing, Benjamin’s cantata reaffirms another bit of Englishness. A national choral tradition runs back to Purcell and Handel, was sharpened in Mendelssohn’s Elijah, and was revived in the early twentieth century by Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius and Vaughan Williams’ Sea Symphony. Hitchcock and screenwriter Charles Bennett could have used Bach or Beethoven, but the choice of this brooding, mildly modernistic piece reminiscent of Walton is a nice bit of propaganda for British musical culture of the interwar years.

More importantly, the concert sequence solves the film’s ideological problem: How to save the world without destroying your family? Jill’s impulsive scream doesn’t divulge what she and Bob know about the gang, but it does serve to derail the gang’s plan and save Ropa. And by leading the police to follow Ramon to the hideout, she in effect chooses to risk Betty and Bob for the capture of the gang. Here, perhaps, the sheer drive of the action muffles the significance of her choice; Chandler complains that Hitchcock tended to take refuge from plot problems in “wild chases.”

What follows, in the middle of some violence that remains shocking today, is a vigorous reassertion of Englishness. The vignettes during the siege display stalwart national virtues. A postman insists on making his rounds during the gunplay. An inspector swipes sweets and pauses for a cup of tea. The police reluctantly take up arms, only after several of their unarmed number are mowed down. Slipping into adjacent buildings, snipers move a piano while its fussy owner rescues his potted plant. And a cop who was slated to go off duty finds a warm mattress to die on. This unassuming valor, so different from Ramon’s petulant swagger and Abbott’s self-congratulatory sadism, will win out. The victory is announced by the pent-up crowd rushing jubilantly forward as the siege ends.

In any other movie the mother would have been huddling with the child and the man would grab a rifle to pick off his enemy on the roof. But making Jill the crack shot reasserts another quintessentially English image: the hunting, shooting, riding mistress of the estate. She gets her second chance to fire, bringing down Ramon when even the police sniper hesitates. It’s also a bit of guilty revenge for the death of Louis, whom Jill danced into the line of fire. Hitchcock, as usual, renders it elliptically: we see Jill grab the gun but not fire it. As she and Bob and Betty are reunited, the movie that began with the line, “Are you all right, sir?” ends with a mother reassuring her weeping daughter, “It’s all right.”

This, we might say, is how you integrate set pieces into your movie—narratively, stylistically, and thematically. Others would disagree with me, but nearly forty years of living with this film hasn’t made me change my mind. The Man Who Knew Too Much is Hitchcock’s first thoroughgoing masterpiece.

Thanks to Abbey Lustgarten, UW-Madison alum, for her excellent production job on the Criterion disc. Thanks also to Peter Becker and Casey Moore for coordinating the posting of our Film Art piece with this blog entry.

For more on Chandler and Hitchcock, see William Luhr, Raymond Chandler and Film (New York: Unger, 1982), 81-93. My quotation comes from Raymond Chandler Speaking, ed. by Dorothy Gardiner and Kathrine Sorley Walker (Books for Libraries Press, 1971), 132.

Hitchcock probably doesn’t deserve 100% of the credit for the Foreign Correspondent windmill scene; it was designed by the great William Cameron Menzies.

When I wrote the Film Art analysis back in the 1970s, Kristin hadn’t elaborated her ideas about how large-scale parts, or acts, can shape a film. Yet I think that the three parts that the analysis mentions constitute pretty well-articulated acts. The first part has as its turning point Bob’s realization that when Gibson traces Betty’s call, police will converge on Wapping and endanger her. So Bob and Clive set out to save her. That decision comes about twenty-six minutes into the movie. I’d mark the end of the second act with Abbott’s sending Ramon on his mission after playing the cantata recording; that comes at about fifty-three minutes into the film. At this point we know everything we need to know, so the premises can play out. The last act is shorter, as climaxes tend to be. The Albert Hall sequence and the final shootout and rescue take up the final twenty-three minutes, capped by a very brief epilogue of the reunited family. For more on act structure, see Kristin’s entry here, mine here, and my essay on action movies, as well as Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood and my The Way Hollywood Tells It.

A final note: Frank Vosper, who plays Ramon, was a well-known stage actor and playwright. His most famous play is Love from a Stranger (1936); the film version was released in 1937. Another successful Vosper play was the fantasy comedy Murder on the Second Floor (1929), in which a writer devises a play consisting of all the clichés of sensational mystery fiction. But the Vosper play that piques my curiosity most is his 1927 drama called—I’m not kidding—Spellbound.

See? With Hitchcock you always get more.

The Man Who Knew Too Much.

News! A video essay on constructive editing

DB here:

In connection with our textbook, Film Art: An Introduction, we’ve created several videos examining film techniques. Thanks to Peter Becker and Kim Hendricksen of Criterion Classics and Janus Films, we’ve been able to include clips from film classics, from Ashes and Diamonds to Ugetsu Monogatari. Because our publisher McGraw-Hill sponsored the production of these pieces, most of them are on a dedicated website called Connect, accessible only to students and teachers using the book in courses. We’ve made one video freely available on Criterion’s own site, where Kristin discusses some editing techniques in Agnès Varda’s Vagabond.

But not everybody who reads Film Art is in a course using the online supplements. And some people who aren’t reading Film Art might still enjoy learning more about the topics we cover. Moreover, we’ve had such good response to the Connnect clips that we decided to create a longer, more wide-ranging piece, also suitable for classrooms. So we prepared another video and today are making it available to anyone.

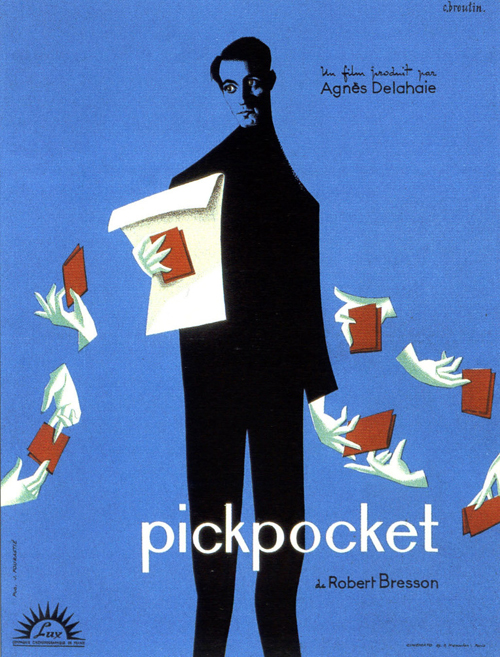

The Connect pieces mostly concentrate on single scenes, whereas this one roams across several films before focusing on a single example. Specifically, we look at the technique of constructive editing, which we discuss in Chapter 6 of FA. The video draws examples from silent films including Harold Lloyd’s Number, Please? (1920) and Lev Kuleshov‘s Engineer Prite’s Project (1918), while our more recent examples include The Social Network and The Ghost Writer. Thanks again to Criterion, the extract we focus on comes from Bresson’s brilliant Pickpocket (1959).

This piece is produced by Erik Gunneson, a local filmmaker who did an excellent job on the Connect materials. I wrote the script and narrated. (A cold I couldn’t shake off betrays itself in my voice.) We did the work in our production facility here at the University of Wisconsin–Madison Department of Communication Arts.

The links flagged above indicate blogs that are related to this new video. Some others are “What happens between shots happens between your ears” and “The Movie looks back at us” and “They’re looking for us.” There’s also “Three nights of a dreamer,” discussing a passage in In the City of Sylvia that may be a slantwise homage to Bresson’s editing technique.

Just to be clear: The twelve-minute video is available to anyone who’s interested. You can watch it below or on Vimeo. Erik, Kristin, and I hope you enjoy it.

PS 4 November 2012: Our discussion of the Kuleshov effect has led some to ask us whether the several videos on YouTube are authentic footage of Kuleshov’s experiments. Alas, they are not, but Kristin and I don’t know their provenance. However, in Oksana Bulgakowa’s documentary on the Kuleshov effect, available on YouTube, there are some fragments of the surviving footage, starting at 4:28. Oksana has also helped complete the experiment by inserting a substitute for a missing shot. In addition, I’m reminded by Joe McBride and Katharine Spring of Hitchcock’s famous explanation of the Kuleshov effect, available on the DVD, A Talk with Hitchcock. An excerpt from that is posted on YouTube, probably illegally.

You the filmmaker: Control, choice, and constraint

DB here:

The tenth edition of our textbook, Film Art: An Introduction will be available in early July. It has so many new features that it’s our most extensive revision in at least a decade.

Kristin has already written about one of our major additions: supplemental film extracts from the Criterion Collection, with voice-over commentary and other sorts of analysis. (Go here for a sample.) These will be accessible to professors for incorporation into their syllabi. More of them may also become generally available on the Criterion website.

The text has been extensively rewritten, aiming at maximal clarity and freshness. There are many local changes too, with updated examples from a variety of films both old and new. Regular readers will notice that we have made two replacements: Koyaanisqatsi is now our example of associational form, and Švankmajer’s Dimensions of Dialogue is our example of experimental animation. Regretfully, we had to drop our earlier examples, Bruce Conner’s A Movie and Robert Breer’s Fuji, because they are available only in 16mm, and most teachers and readers don’t have access to them. On the other hand, we enjoyed analyzing the new items and think that they serve their purpose very well.

Today I’m going to point out some of the broader changes, while also considering the book’s overall approach.

Parts and wholes

When Film Art appeared in 1979, it was the first textbook in English written by people who had received Ph.D.s in film studies. Specifically, FA emerged from my teaching a lecture-and-discussion course called “Introduction to Film” to several hundred students each semester for many years.

In the mid-seventies, there were almost no film studies textbooks, and none of them seemed to us to reflect the directions of current research. As a result, the first edition of FA included topics that were emerging in the field, such as narrative theory and conceptions of ideology. It also suggested a coherent, comprehensive view of cinematic art, from avant-garde and documentary cinema to mainstream film and “art cinema.”

The book has changed since then, but its approach has remained consistent in two primary respects. For one thing, it tries to survey the basic techniques of the medium in a systematic fashion. Here the key word is “systematic.” It seemed to us that we might go beyond simple mentioning this or that technique—editing, or acting, or sound—and instead treat each technique in a more logical and thorough way. But film aesthetics wasn’t yet conceived in this way, so to a considerable extent the textbook had to offer some original ideas.

For example, most people thought of editing primarily as a means of advancing the film’s story. That’s certainly accurate up to a point, but we tried to go up a level of abstraction. We suggested that the change from shot to shot had implications for what was represented (the space shown in the shots, the time of the action presented), as well as for the sheer graphic and rhythmic qualities onscreen, independent of what was shown. That created four dimensions that the filmmaker could control, and we illustrated how Hitchcock shaped all of them in a sequence from The Birds.

Nobody before had surveyed editing’s possibilities in this multidimensional way. The result was that we were able to trace out several expressive options. We analyzed the 180-degree system for presenting story space, and Film Art became the first film appreciation textbook to explain this. We also laid out ways in which shots could manipulate the order, duration, and frequency of story action. We also considered sheerly graphic and rhythmic possibilities of editing, not all of which are tied to narrative purposes. Similarly, we tried to show that sound, another familiar technique, could be understood as a bundle of systematic options relating to sound quality, locations in space, relation to time, and other factors.

In sum, very often the array technical options had an inner logic. This urge to cover all bases helped us notice options that usually escaped critics. So by concentrating on the graphic dimension of editing, we noticed that some filmmakers tried to create pictorial carryovers from shot to shot, a device we called the “graphic match.”

A second core principle of the book was the idea that we ought to think about films as wholes. There’s a strong tendency in film criticism, in both print and the net, to fasten on memorable single sequences for study. There’s nothing wrong with this, of course, but we think it needs to be balanced by considering how all the sequences in a film fit together. That led us to consider various types of large-scale form, both narrative and non-narrative.

Again, this was new to the field. We showed students how to divide films into parts and then trace patterns of progression and coherence across them. This is a valuable skill for both intelligent viewers and people who might want to work in filmmaking. We showed how the distinction between story and plot could help explain large-scale narrative construction. We suggested that issues of point-of-view and range of character knowledge exemplified broader principles of narration, the ways films pass information along on a moment-by-moment basis. And although most film courses show narrative films (mine did too), we wanted students to think about other large-scale organizational principles too, such as rhetorical argument and associational form. Again, thinking about these more general possibilities led us to consider creative options that hadn’t been the province of introductory texts, such as rhetorical documentary and poetic experimental cinema.

These two efforts—comprehensive study of techniques and a holistic emphasis on total form—weren’t FA’s only salient points. We tried to incorporate more familiar elements from genre studies and historical research. But they did set the book apart, and do still. I believe that we made contributions to our understanding of film aesthetics. One measure of these contributions is the extent to which FA has been regarded as not only a textbook but an original contribution to film aesthetics. Another sign is the fact that other textbooks have relied, sometimes to a startling degree, upon FA for concepts, organization, and examples.

Categories, categories

Associational form: Koyaanisqatsi.

Still, we did encounter objections.

Some readers worried that FA’s layout of logical categories took away some of the magic and mystery: Art dies under dissection. Some also protested that filmmakers didn’t use the categories and terms we invoked. These concerns have, I think, waned a bit over the years, but I’ll address them anyhow.

First, as to the need for categories. As a genre, the textbook in art theory has a very old ancestry. Aristotle’s Poetics, a survey of what we’d now call literary art, bristles with categories—drama vs. epic, comedy vs. tragedy, types of plots, etc. In the visual and musical arts, from the Middle Ages into the Renaissance, writers tried to systematically understand the principles of artists’ practice. Leon Battista Alberti’s treatise on painting tried to show that as an activity, painting had many “parts,” such as drawing, color, and light.

This classificatory urge continued through the centuries, and it continues today. Pick up a book on the visual arts today and you’ll see chapters on composition, color, texture, and the like. The same goes for music; an introductory book will survey rhythm, harmony, melody, musical forms, and so on. There’s no escaping some sort of categorizing if we want to understand any subject, and this goes as well for art traditions.

The categories governing centuries-old arts are largely taken for granted. But film is a newish medium, and film studies a still-young academic discipline, so there remains a lot of exploratory thinking to be done. In the late 1970s, Film Art undertook some of that exploration.

A lot of thinking about film employs categories that are very abstract and general (say, “realism” versus “non-realism”). Our frame of reference tries to be more concrete, more fitted to the particularity of what films actually look and sound like. Whenever we could, we incorporated filmmakers’ explicit concepts into our analyses. FA, for instance, was the first appreciation textbook to introduce the principles of continuity editing that were craft routines among directors and cinematographers.

At other times, we tried to synthesize ideas that were circulating in the filmmaking community. For example, for several decades filmmakers and critics have been saying that editing is getting faster, close-ups are getting more prominent, and camera movements are becoming more salient, even aggressive. From studying hundreds of films, we came to the conclusion that these trends are part of a new approach to film style, and we dubbed that “intensified continuity.” That term aims to capture the idea that for the most part these techniques are in accord with traditional continuity editing, but they sharpen and heighten its effect.

Occasionally we tried to clarify concepts. Most notoriously, we borrowed from French film theory the distinction between “diegetic” and “nondiegetic” sound because all the other terms (“source music,” “narrative music,” etc.) seemed to us ambiguous or inexact. As with most categories, individual films can play with or override this distinction, but it’s a plausible point of departure because traditionally the distinction is respected.

Contrary to some objections, then, we often worked with ideas used by practicing filmmakers. Where traditional terminology seemed inadequate to those ideas, we created our own. And some effects we may notice in movies may have no currently accepted names. In some cases, as in the graphic match, the phenomenon may not even have been identified. We haven’t tried to conjure up fancy labels; we’ve just tried to point to the ways some films work. Anyhow, the term doesn’t matter much, but the concept does.

So one way to think about the categories of form and style in FA is to see them as bringing out principles underlying filmmakers’ practical decisions. A director may choose to do something on the basis of intuition, but we can backtrack and reconstruct the choice situation she faced. If we want to survey the possibilities of the medium, one way to do it is to build categories that show the expressive options available, even if filmmakers don’t sit down and brood on each one.

Thinking like a filmmaker

Walt Disney’s Taxi Driver (Bryan Boyce).

Categories are inevitable, and they allow us to consider creative choices systematically. Making this second point explicit is the most important overall revision in the new version of Film Art.

Previous editions took the perspective of the film viewer. This is reasonable: Teachers want to enhance their students’ skills in noticing and appreciating things in the movies. But from the start FA also indicated that the things we discussed also mattered to filmmakers. As the years went by, we incorporated more comments and ideas from screenwriters, cinematographers, sound designers, directors, and other artisans—often as marginal quotes that, we hoped, would reinforce or counter something in the main text.

Now, though, we’ve shifted the perspective more strongly toward the filmmaker—or rather, toward getting the viewer to think like a filmmaker.