Archive for the 'Film technique: Sound' Category

Play it again, Joan

“The happy heart loves the cliché.”

–Myra Hudson (Joan Crawford) in Sudden Fear.

Sometimes your audience gets what you’re saying faster than you do. Years ago, after I gave a lecture in a class at Columbia University, a grad student came up and said: “What you’re doing is looking for the conventional side of unconventional films and the unconventional side of conventional films.” I’d say it’s not all I try to do, but the student’s chiasmus does capture a lot of what interests me.

It’s especially on target for Hollywood cinema. I don’t understand criticisms of Hollywood for not being realistic. It’s a highly stylized, artificial cinema, only a few notches above ballet or commedia dell’arte. Some of our best critics, like Parker Tyler and Manny Farber and Geoffrey O’Brien, have understood this. All the artifice will demand plenty of conventions, yes, but there are always filmmakers ready to treat them in fresh ways. And the churn is swift. American studio cinema is constantly finding new variations on its traditional forms, formats, and formulas.

Do-overs are allowed

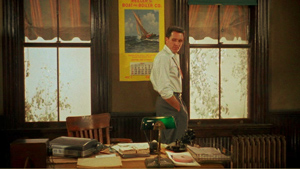

Sleep, My Love

Take replays. The repeated sequence has become so common in our movies that nobody much notices it any more. We’re quite used to seeing an earlier action revisited. Often the replay simply serves to remind you of what happened, as when clues to a mystery are given in fragmentary flashbacks. The replay may also aim to get you absorbed in a character’s mental life. John, the hitman in John Woo’s The Killer, is traumatized by the fact that he blinded an innocent woman during a contract hit, and the moment of her wounding haunts him.

Sometimes, however, we get multiple-draft replays, in which the second version significantly alters the first. A common gambit is to have the second version show more of what happened, as in the money drop in Jackie Brown. Other cases show contradictions, as when conflicting testimony is dramatized in flashbacks. The most recent version I’ve seen occurs in The Debt, when the central 1966 section of the film concludes by showing what really happened when Dr. Vogel slashed Rachel and fled. In such cases the replay becomes less a true repetition and more of a revision, a new version questioning or canceling what we’ve seen before.

The idea isn’t new. You can find the replay in various forms in trial films of the 1930s, as I’ve discussed here. But the replay really came into its own during the 1940s. Directors and screenwriters experimented with the device as part of a broader initiative, burrowing into new niches in the ecosystem of classical narrative.

In those films, it’s common for replayed scenes to show an incident haunting the protagonist, as when the tormented bride of The Locket is assailed by memories as she walks down the aisle. Sometimes a flashback fills in information that was cunningly omitted from the earlier version, as in Mildred Pierce. And we also have competing accounts of what happened, as variant replays furnish multiple drafts. The most famous example is probably Crossfire.

By 1950, Joseph Mankiewicz could dream up one of the most daring experiments of the period, one that anticipated the repeated scene in Persona. For All about Eve, Mankiewicz planned to present Eve’s memorable monologue about the power of theatre twice: first through the sympathetic eyes of Karen (Celeste Holm), then from the perspective of the bitter Margo Channing (Bette Davis). What would viewers and other filmmakers have made of it? But Fox studio head Darryl F. Zanuck ordered the replay dropped, for reasons I speculate about in this entry’s codicil.

Mankiewicz’s unseen experiment with Eve’s “Audience Aria” reminds us that replays affect the soundtrack too. The most common use of replays is probably auditory, that line of dialogue that flits through a character’s consciousness—an auditory flashback, in effect. “Who knows what you may do the next time?” asks the sinister voice of the psychiatrist as Alison (Claudette Colbert) totters up the stairs in Sleep, My Love (1949). Several snatches of dialogue can flow together to recall a host of earlier scenes. In The Hard Way (1943), on another staircase, Katie (Joan Leslie) becomes distraught as bits of dialogue spoken by several characters flash through her mind.

More unusual is the audio replay in Duvivier’s wonderfully stylized Lydia (1941). A flashback to a ball is introduced by Lydia’s voice-over, recalling the splendid ballroom with its mirrorlike floors and the “divine aggregation of musicians, hundred of them, I think.”

But then her old lover corrects her memory and we get a flashback showing a more modest ballroom with a small ensemble.

Over these later shots, however, we hear bits of Lydia’s earlier description of the big ballroom and troops of musicians, in contrast to what we see. The sound flashback functions as a wry narrational commentary on Lydia’s stubborn romanticism.

Purely auditory replays tend to be subjective, but could we have an objective one? And can it promote surprise and suspense? As we say in Wisconsin, you bet. (Not you betcha.)

The replay machine

A lighthearted instance appears in The Pajama Game (1957). Sid Sorokin (John Raitt) , the new superintendant at the Sleeptite Pajama Factory, is falling in love with Babe Williams (Doris Day), the no-nonsense head of the labor union’s Grievance Committee. He sings into his Dictaphone about her in the song, “Hey, There (You with the Stars in Your Eyes).”

At the end of the song’s first section, he plays it back and then comments sourly on the lines he’s just sung. By the end, he’s joining himself in a duet, harmonizing nicely.

This instant playback wasn’t a cinematic invention, though. The same number, including the Dictaphone gimmick, was employed in the original Broadway production.

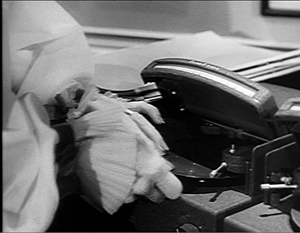

The Dictaphone, which used both wax cylinders and plastic belts for recording, was a popular device for businesses. Erle Stanley Gardner employed it for dictating many of his novels. A competitor to the Dictaphone was the SoundScriber, a late 1940s device using vinyl phonographic discs. The SoundScriber figures in a more sustained and suspenseful replay scene a few years before The Pajama Game.

In Sudden Fear (1952), Myra Hudson (Joan Crawford) is a prosperous playwright who has outfitted her office with a SoundScriber. She uses it for dictating plays and correspondence. One evening before a party, euphoric after her new marriage to the handsome actor Lester Blaine, she meets with her attorney to prepare a new will. He proffers a draft that assigns a modest sum to Lester, but she considers it insulting. She switches on the SoundScriber and dictates a new will, one leaving all her estate to Lester.

But we’ve had our suspicions about Lester, since he’s played by Jack Palance, an actor with more juts to his facial planes than a Giacometti bust. Our fears are confirmed after Lester hooks up with his old girlfriend Irene (Gloria Grahame). When they learn that Myra is making a new will, they believe she’s going to give the bulk of her estate to a foundation.

On the evening of the party, as she starts dictating her new will, the guests arrive and she descends to meet them. Irene and Lester slip away and meet in Myra’s study. Fade out on Lester closing the door.

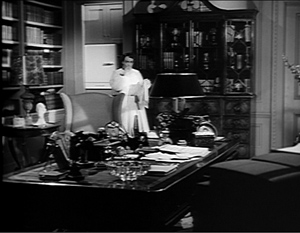

Next morning, Myra return to her study and discovers she left her SoundScriber on all night. She hits replay and listens to herself bequeathing all her money to Lester. This is the replay that launches the big action. As she’s about to switch off the machine, she hears the conversation starting between Lester and Irene. The microphone, left on accidentally, has picked up their plotting.

The couple is still under the false impression that the new will leaves Lester penniless. We hear him declare his contempt for Myra while caressing and embracing Irene. They start planning to kill her before she can sign the new will.

The SoundScriber scene gives us two plot developments, past and present, simultaneously. The recording fills in the gap left by the fade-out: Now we know what happened behind those closed doors. On the visual track, we can watch Myra’s developing anxiety about the couple’s murder plot but, more piercingly, we register her realization that Lester has never loved her.

Across seven minutes, Joan Crawford executes a carefully modulated solo performance, for the most part with no accompanying score. Meanwhile, Palance and Grahame get to act viva voce. And David Miller’s direction scales and times things nicely. I won’t try to analyze the very end of the scene, let alone its frenzied aftermath. I just want to trace the dynamics of the double-layered time scheme the replay machine gives us.

Joanie, more than shoulders

The recorded scene develops from the lovers’ frustration with keeping up a false front, then to their suspicion that Irene will cut Lester out of her will, then to the mistaken belief that she’s just done so, and finally to their decision to kill her. Myra’s playback scene proceeds, I think, in four stages as well. Myra starts out placid and almost giddy in her love for Lester. She’s abruptly shocked and disenchanted when she learns he doesn’t love her; her stomach churns. A third phase consists of her discovery that Lester and Irene intend to kill her, and she devolves into sheer panic. The last phase, of which I’ll show only a bit, initiates a search for a way to defend herself.

Myra comes in euphoric. As she replays her dictation of the night before, she strolls around her study, going far back to the distant refrigerator for a glass of milk and then coming forward. She seems to savor hearing again her own declaration of her devotion to Lester.

Myra’s circuit around her study isn’t just filler: it etablishes the rear area for use later. But now, as she’s about to turn off the recording, she hears Lester’s voice: “What’s up?” She backs up a little, bumping the desk as she realizes that there’s more on the disc. This recoil, as a performance decision, will get magnified in the course of the scene. Then Miller cuts to a reaction shot.

The first of several optical point-of-view shots gives us a close view of the twin SoundScriber units (good for product placement too). Myra has set the milk down on the console.

As we hear Lester venting his contempt for her, Myra’s eyes fill with tears. Worse, he adds that he’d like to tell her he never loved her for a moment. “I’d like to see her face.” He can’t, but we can; in the closest shot yet, she looks right at us. Hollywood can be brutal.

She turns away and, seen from a new angle by the desk, she advances toward us. On the track, Lester is pitching woo to Irene. Myra realizes that he lusts for this other woman. She sighs. Listen closely and you can hear her emit a soft whimper as well.

Another cut to the SoundScriber as Lester says he dreams of holding Irene: “I don’t know how I stand it, not being with you.” On these last few words, cut to Irene, turning away in shame.

She rushes back, having heard enough. A low angle shows her about to switch off the horrible recording when Irene is heard noticing the attorney’s draft of the will on the desk. “It’s the will!” Myra freezes, accentuating the line, and then starts to turn when Lester begins to read the draft.

Having hidden her face from us for a little while, Miller’s direction makes the next close view all the more powerful. (Note the eyebrow work.) Lester’s reaction to the will proves it’s been about the money all along. As he curses Myra, she doubles over grabbing her stomach. This, I take it, is the high point of the scene’s second phase–a sheerly physical reaction to Lester’s cynical betrayal of her love.

Phase three starts, I think, when Irene is heard purring, “Suppose she isn’t able to sign it on Monday.” The line is heard over a shot of the machine, and not a POV at that. The visual narration cunningly delays, by just a few seconds, Myra’s reaction to Irene’s hint. The cut shows her listening, stunned. Lester agrees with Irene. “I’d get it all! Why not?”

Myra turns, as if in disbelief, and a closer view of SoundScriber underscores Irene’s response: “Lester, I have a gun.”

This triggers the scene’s big movement: Myra’s retreat from the recording. Back to the extreme long shot, low angle, as she hurls herself toward the rear wall and sidles along toward the refrigerator, taking refuge behind the chair. The lovers discuss how to arrange an apparent accident, all the while kissing and declaring their love. Lester exclaims, “I’m crazy about you! I could break your bones!” as only Jack Palance could say it.

Again we get an optical POV shot, but now from Myra’s position across the room as Lester muses on “a nice little accident.” And in the cut back to Myra, we hear Irene say, “We’ll work something out. I know a way.” The recording needle is stuck in a groove, and we hear her say it again: “I know a way.” Music comes up for the first time, shifting the action to a new pitch.

I know a way. This mechanical glitch, I think, pushes fear into panic. The tightest close-up yet of the spinning disc is a sort of mental subjectivity: It’s not what Myra sees exactly, but an expression of her being riveted by insistent, maniacal repetition of Irene’s assurance: I know a way. Myra rushes out of the shot and hurls herself into the bathroom to vomit. All the while we hear, again and again: I know a way.

The couple’s plotting has driven Myra out of the room, as the music rises and nearly suppresses Irene’s “I know a way.” In a closer view of the bathroom, Myra staggers to the sink and splashes water on her face, while the record still spins and Irene’s voice taunts her.

But now we get the start of a new phase, with Myra trying to seize the initiative. In a burst of anger she rushes back to the machine, switches it off, and fumblingly takes out the disc. By the time she does so, we’ve heard Irene’s “I know a way” thirty-one times. Talk about hammering the audience.

Myra grips the disc, proof of the criminal conversation, and….

…But my analysis has gone on too long. It’s reasonable, although mean, to stop with the end of the replay. The rest of the sequence builds on what we’ve heard and seen, developing Myra’s efforts to defend herself.

I should note, though, that there follows a hallucinatory sequence in which we get not only perceptual subjectivity, like the POV shots, but also mental imagery and sounds as well. That sequence also includes auditory flashbacks of the usual sort, Myra’s anxious memories of things that Lester and Irene said on the SoundScriber recording. They’re replays of a replay, if you want to get fancy about it.

Conventioneering

In a way this scene is just a variant of a common storytelling convention: Someone accidentally overhears a key piece of information, in an adjacent room or over the phone. But the sequence shrewdly recasts this convention in ways that pay off on many dimensions. We get the suspense attached to the lovers’ mistaken belief that Myra will cut Lester out, and we get Myra’s reaction to it. That reaction is compounded of her sense of betrayal, her disillusion, and her realization that she’s in danger. Had she been eavesdropping on their conversation, she could have burst in on them and denounced their misreading of her will. As it is, she must helplessly listen to them unfold their plans.

After more than a decade of female Gothics–aka”woman in peril” movies, aka I-think-my-husband’s-trying-to-kill-me movies–from Suspicion and Gaslight to Woman in Hiding, Miller and his colleagues found a fresh way to put a lady in a cage. Schema and revision, a key process in the history of any art form, allows ingenious artists to remake what tradition hands them. Twenty years later, Francis Ford Coppola and Walter Murch would build an entire movie, The Conversation, around the audio replay and its possibilities for objectivity and subjectivity. Over and over, the unconventional burrows inside the conventional.

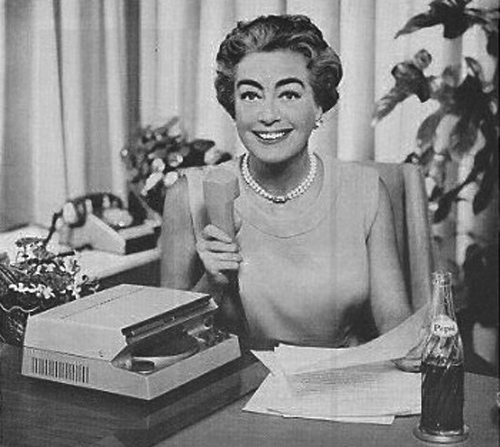

After this film, Joan Crawford became a spokesperson for SoundScriber. (See below.) Who would know better than she the advantages of the gadget? Perhaps Joan even had a stake in the firm. Such fruitful synergy wouldn’t be unknown in Hollywood. Jack Webb found the Teleprompter so useful in shooting Dragnet episodes that he invested in the company.

On All About Eve and Zanuck’s purging of the replay of Eve’s monologue: I suspect that it was a forced byproduct of another decision Zanuck had taken. The film consists largely of flashbacks, and Mankiewicz had intended to move through them by shifting from one character to another. At the awards dinner the flashbacks begin with Karen, and then another block of them, grounded in Margo’s memories, was to take up later episodes in Eve’s ascent to stardom.

But the film ran very long, so Zanuck cut the framing portion at the dinner that would have introduced Margo’s flashbacks. The result is that in Karen’s flashback, we occasionally hear Margo’s narration of certain episodes Karen didn’t witness. But once we’ve lost Margo’s narrating frame, then it becomes quite difficult to justify re-hearing Eve’s ruminations on theatre from anything approximating her point of view. I suspect that consistency of this sort played a role in Zanuck’s cutting Eve’s monologue. Plus it was a pretty daring move on Mankiewicz’s part. And the film is already pretty long. The fullest account of the changes, though still not as specific as I’d like, is in Sam Staggs’ All About All About Eve (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2001), 170-172. As Staggs points out, Mankiewicz did work differential-viewpoint flashbacks into The Barefoot Contessa (1954).

Sudden Fear is available on a so-so DVD transfer from Kino Lorber.

The interplay between film and fiction in the 1940s is fascinating, and we can sometimes find rough equivalents between techniques. Here is a stream of auditory flashbacks in Steve Fisher’s novel I Wake Up Screaming (1941), ending with the protagonist’s inner monologue.

I’d remember Lanny Craig saying: “They crucified me . . . it was because of Vicky Lynn!” And the night Robin Ray said: “She’d laugh, see, and it was like Guy Lombardo’s band playing.” And Hurd Evans: “I only get two hundred and fifty a week.” Tick-tock, the faceless clock on Sunset. “It’s possible to build a case out of nothing,” the assistant district attorney said. Where was Harry Williams? If he’d been murdered, where was his body?

By the end of the thirties, of course, such montages were already heard in radio programs as well.

Joan Crawford was also a spokeswoman for Pepsi-Cola, having married the man who became the company’s CEO. This image comes from a nifty survey of her endorsements available here.

Propinquities

Jinhee Choi, Centre Pompidou, January 2010.

Propinquity: Nearness, closeness, proximity: a. in space: Neighborhood 1460. b. in blood or relationship: Near or close kinship, late ME. c. in nature, belief, etc.: Similarity, affinity 1586. In time: Near approach, nearness 1646. —Oxford Universal Dictionary

DB here:

In any art, tools and tasks matter. From the first edition of Film Art (1979) to the present, our introduction to film aesthetics starts with an overview of film production. How is production organized within the commercial industry, or within a more artisanal mode? What freedom and constraints are afforded within the institutions of filmmaking? How does current technology support or limit what the filmmaker can do? And how do filmmakers explain what they’re doing—not just as personal proclivities but as rhetorical “framings” that lead us to think of their work in a particular way?

Some would call this approach “formalism,” but that label doesn’t capture it. Traditionally formalism refers to studying an artwork intrinsically, as a self-sufficient object. In this sense, our perspective is anti-formalist: We look outside the movie to the proximate conditions that shape its form, style, subjects, and themes.

More literary-minded film scholars have sometimes been impatient with this perspective. Yet in the history of painting and music, it has yielded real advances in our knowledge. It continues to do so in film studies too, as I learned when we came back from Yurrrp to find some books awaiting us. (Kristin has already remarked on the stacks of DVDs that had accumulated.) Among these were books that illustrate the continuing value of situating film artistry in its most immediate context: the creative circumstances, the norms and preferred practices operating within traditions, the rationales that artists offer for their choices. Even better, the books were written by friends, so we have both intellectual and personal propinquity. I have always wanted to use the word propinquity in a piece of writing.

Memories of Murder (Bong Joon-ho).

Jinhee Choi’s The South Korean Film Renaissance: Local Hitmakers, Gobal Provocateurs is a wide-ranging survey of what some have called the “next Hong Kong”–a popular cinema of brash impact and technical polish, on display in JSA, Beat, Dirty Carnival, My Sassy Girl, and the like. But unlike Hong Kong, South Korea has a strong arthouse presence too, typified by Hong Sang-soo’s exercises in parallel narratives and thirtysomething social awkwardness. Between these poles stands what local critics called the “well-made” commercial film, as exemplified by Bong Joon-ho’s Memories of Murder.

Choi, a professor at the University of Kent, mixes analysis of cultural and industrial trends with consideration of crucial genres (notably the “high school film”) and major auteurs. She is the first scholar I know to explain changes in the Korean film industry as emerging from a dynamic among critics, filmmakers, private funding, and government sponsorship. A must, I would say, for anyone interested in current Asian film.

T-Men (Anthony Mann, cinematographer John Alton).

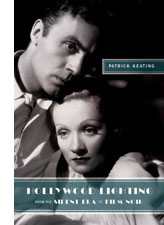

The South Korean Film Renaissance is matched by a work of equal subtlety, Patrick Keating’s Hollywood Lighting: From the Silent Era to Film Noir. Keating has an MFA in cinematography from USC, and his Ph. D. work concentrated on classical American cinema. His book captures the craft of the great studio cameramen, following not only what they said they were doing (in interviews and in the trade papers) but also what they actually did. He homes in on the contradictory demands facing artists who, they claimed over and over, had to serve the story. How do you claim artistry if your contribution is unnoticeable? This problem becomes acute with film noir, where the style is expected to come forward to a significant degree.

The South Korean Film Renaissance is matched by a work of equal subtlety, Patrick Keating’s Hollywood Lighting: From the Silent Era to Film Noir. Keating has an MFA in cinematography from USC, and his Ph. D. work concentrated on classical American cinema. His book captures the craft of the great studio cameramen, following not only what they said they were doing (in interviews and in the trade papers) but also what they actually did. He homes in on the contradictory demands facing artists who, they claimed over and over, had to serve the story. How do you claim artistry if your contribution is unnoticeable? This problem becomes acute with film noir, where the style is expected to come forward to a significant degree.

Keating scrutinizes the films with unprecedented care, tracing not only cameramen’s distinctive styles but showing that originality was always in tension with the conventional lighting demands of various genres and situtations. Many big names are here—John Seitz, Gregg Toland, John Alton—but the book also examines innovations coming from solid craftsmen like Arthur Lundin, who lit Girl Shy and other Harold Lloyd films. You won’t look at a studio movie the same way after you’ve digested Keating’s richly illustrated analyses.

Both Jinhee and Patrick were students here, and I directed the dissertations that eventually became these books. So of course I’m biased. But I think that any outside observer would agree that these monographs show the value of studying how film artistry and the film industry intertwine.

Blue (Krzysztof Kieslowski).

No less sensitive to the interplay of art and business is Patrick McGilligan’s Backstory 5: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1990s. The collection is as illuminating as earlier installments have been. How could it not be, with career ruminations from Nora Ephron, John Hughes, David Koepp, Barry Levinson, John Sayles, et al.?

I’ve long found Pat’s Backstory volumes a treasury of information about Hollywood’s craft practices. Every conversation yields ideas about structure, style, and working methods. In this volume, for instance, Richard Lagravanese points out that scenes have become very short; with slower pacing in the studio days, scenes had time to breathe. And after claiming over and over that cinematic narration comes down to patterning story information, I was happy to read Tom Stoppard:

The whole art of movies and in plays is in the control of the flow of information to the audience. . . . how much information, when, how fast it comes. Certain things maybe have to be there three times.

In the studio days this last condition was called the Rule of Three: Say it once for the smart people, once for the average people, and once more for Slow Joe in the Back Row. Some things don’t change.

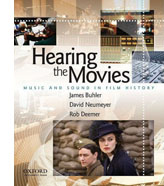

Pat McGilligan is also a Wisconsin alumnus, so to keep these notes from getting too incestuous, I’ll just mention that I know the distinguished musicologist David Neumeyer chiefly from his writing (though I have to confess I first met him when he visited . . . Madison). Along with coauthors James Buhler and Rob Deemer, David has published an excellent introduction to film sound. Hearing the Movies: Music and Sound in Film History is designed as a textbook, but it’s so well written that every movie lover would find it a pleasure to read.

Pat McGilligan is also a Wisconsin alumnus, so to keep these notes from getting too incestuous, I’ll just mention that I know the distinguished musicologist David Neumeyer chiefly from his writing (though I have to confess I first met him when he visited . . . Madison). Along with coauthors James Buhler and Rob Deemer, David has published an excellent introduction to film sound. Hearing the Movies: Music and Sound in Film History is designed as a textbook, but it’s so well written that every movie lover would find it a pleasure to read.

The examples run from the silent era (including Lady Windermere’s Fan, a favorite of this site) to Shadowlands, and while music is at the center of concern, speech and effects aren’t neglected. There’s a powerful analysis of the noises during one sequence of The Birds, and the authors pick a vivid example from Kieslowski’s Blue (above), in which Julie is shown listening to a man running through her apartment building; we never see the action that triggers her apprehension.

The authors provide a compact history of sound film technology, including many seldom-discussed topics. For instance, 1950s stereophonic film demanded bigger orchestras and more swelling scores, while separation among channels permitted scoring to be heavier, without muffling dialogue. Throughout, Neumayer and his coauthors balance concerns of form and style with business initiatives, such as the growth of the market for soundtrack albums and CDs (a topic first explored by another Wisconsite, Jeff Smith, in his dissertation book). Once more we can arrive at fine-grained explanations of why films look and sound as they do by examining the craft practices and industrial trends that bring movies into being.

Watching back episodes of the American version of The Office recently, I’ve been struck by the premise it takes over from the UK original. This comedy of humors in Cubicle World is supposedly recorded in its entirety by an unseen film crew. I enjoy the clever way in which the show bends documentary techniques to the benefit of traditional fictional storytelling. The slightly rough handheld framings suggest authenticity, and the to-camera interviews permit maximal exposition by giving backstory or developing character or filling in missing action. The premise that an A and a B camera are capturing the doings at the Dunder Mifflin paper company permits classic shot/ reverse-shot cutting and matches on action.

The camera is uncannily prescient, always catching every gag and reaction shot; even private moments, like employees having sex, are glimpsed by these agile filmmakers. Above all, the camera coverage is more comprehensive than we can usually find in fly-on-the-wall filming. For instance, Dwight is preparing Michael for childbirth by mimicking a pregnant woman and Andy, behind him, tries to compete. Here are four successive shots, each one pretty funny.

Somehow the cameramen manage to supply a smooth cut-in to Andy, and that’s followed by a reaction shot, from a fresh angle, showing Jim watching. The range of viewpoints, implausible in a real filming situations, is often smoothed over by sound that overlaps the cuts, as in both documentary and fictional moviemaking. (See our essay on High School here to see how a genuine documentary uses these techniques.)

Of course I’m not faulting the makers of The Office for not rigidly imitating documentary conditions. Any such blend of fictional and nonfictional techniques will involve judgments about how far to go, as I indicate in an earlier post on Cloverfield. It’s just to acknowledge that TV visuals have their own conventions, and these can be creatively shaped for particular effects. We ought to expect that those conventions would encourage close analysis as easily as film traditions do. Jeremy Butler’s new book Television Style offers the best case I know for the claim that there is a distinct, and valuable, aesthetic of television.

Following his own study Television: Critical Methods and Applications (third edition, 2007) and paying homage to John Caldwell’s pioneering Televisuality, Butler gets down to the details of how various TV genres use sound and image. Butler’s conception of genres is admirably broad, considering dramas, sitcoms, soap operas, and commercials, each with its own range of audiovisual conventions and production practices. His discussion of types of television lighting complements Keating’s analysis; put these together and you have some real advances in our understanding of key differences and overlaps between film and video.

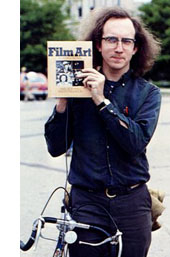

Kristin has met Jeremy, but I haven’t yet. In any case, Television Style shows that he’s a kindred spirit who’s made original contributions to this research tradition. Like Jinhee, Patrick, Pat, and David, he demonstrates that we can better grasp how media work if we study, patiently and in detail, the creative options open to film artists at specific points in history. He began thinking about these matters in 1979, as the photo attests.

Kristin has met Jeremy, but I haven’t yet. In any case, Television Style shows that he’s a kindred spirit who’s made original contributions to this research tradition. Like Jinhee, Patrick, Pat, and David, he demonstrates that we can better grasp how media work if we study, patiently and in detail, the creative options open to film artists at specific points in history. He began thinking about these matters in 1979, as the photo attests.

None of this is to say that artistic norms or industrial processes are cut off from the wider culture. Rather, as becomes very clear in all of these books, cultural developments are often filtered through just those norms and institutions.

For example, everybody knows that in classical studio cinema, women were usually lit differently from men. But Keating notices that often women’s lighting varies across a movie, depending on story situations. He goes on to make a subtler point: there was a greater range in lighting men’s faces. Men could be lit in more varied ways according to the changing mood of the action, while lighting on women was a compromise between two craft norms: let the lighting suit the story’s mood, and endow women with a glamorous look. The fluctuations in the imagery stem from adjusting cultural stereotypes to the demands of Hollywood’s stylistic conventions.

Careful studies like these, alert to fine-grained qualities in the films and the conditions that create them, can advance our understanding of how movies work. Pursuing these matters takes us beyond both the movie in isolation and generalizations about the broader culture; we’re led to examine the filmmaker’s tasks and tools.

Resurrection of the Little Match Girl (Jang Sun-woo, 2002).

The movie looks back at us

DB, still at the Hong Kong International Film Festival:

Abbas Kiarostami has the widest octave range of any filmmaker I know.

His humane dramas of Iranian life, from The Traveller to The Wind Will Carry Us, have justly won acclaim on the arthouse circuit. He has written scripts as well, some—like the under-seen The Journey (1994)—that are as compelling as a psychological thriller. He can conjure suspense out of the simplest acts, such as whether an adult will rip up a child’s copybook (Where Is the Friend’s Home?) or whether a four-year-old boy locked in with his baby brother can figure out how to turn off a stove (The Key). Indeed, I think that one of the great accomplishments of much modern Iranian cinema, with Kiarostomi in the vanguard, has been to reintroduce classic dramatic suspense into arthouse moviemaking.

But at times Kiarostami has moved to an opposite pole, that of extreme minimalism and “dedramatization.” The drift toward a hard-edged structure was there in Ten (2002), which gave us one of his drive-through dramas—people conversing in the front seat of a car—but in severe permutational form (different drivers, different passengers). Rigor was pushed to an extreme in Five Dedicated to Ozu (2003): Five lengthy shots of water landscapes, each many minutes long, taken at different times of day. The biggest dramatic action was the ducks walking through the frame. With Kiarostami, it seems, we cinephiles can have it all—Hitchcock and James Benning in the same filmmaker.

Now Shirin (aka My Sweet Shirin, 2008) marks another highly original exploration. I don’t expect to see a better film for quite some time.

After a credit sequence presenting the classic tale Khosrow and Shirin in a swift series of drawings, the film severs sound from image. What we hear over the next 85 minutes is an enactment of the tale, with actors, music, and effects. But we don’t see it at all. What we see are about 200 shots of female viewers, usually in single close-ups, with occasionally some men visible behind or on the screen edge. The women are looking more or less straight at the camera, and we infer that they’re reacting to the drama as we hear it.

That’s it. The closest analogy is probably to the celebrated sequence in Vivre sa vie, in which the prostitute played by Anna Karina weeps while watching La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc. Come to think of it, the really close analogy is Dreyer’s film itself, which almost never presents Jeanne and her judges in the same shot, locking her into a suffocating zone of her own.

Of course things aren’t as simple as I’ve suggested. For one thing, what is the nature of this spectacle? Is it a play? The thunderous sound effects, sweeping score, and close miking of the actors don’t suggest a theatrical production. So is it a film? True, some light spatters on the edge of the women’s chadors, as if from a projector behind them, but no light seems to be reflected from the screen. In any case, what’s the source of the occasional dripping water we hear from the right sound channel? The tale is derealized but it remains as vivid on the soundtrack as the faces are on the image track. What the women watch is, it seems, a composite, neither theatrical nor cinematic—a heightened idea of an audiovisual spectacle.

Moreover, there are the faces. We see some more than once, but new ones are introduced throughout. Spatially, they float pretty free; only occasionally do we get a sense of where the women are sitting in relation to one another. All are stunningly beautiful, whether young or old. We get an encyclopedia of expressions—neutral, alert, concentrated, bemused, amused, pained, anxious. During a battle scene, faces turn away, eyes lower, and hands shift nervously. The best person to review this movie is probably Paul Ekman, world expert on the nuances of facial signaling.

The weeping starts, by my count, about thirty-eight minutes in, during a rain scene uniting the two lovers Shirin and Khosrow. Thereafter, tears run down cheeks, along jaws and mouths, down necks and nostrils. The film is an almost absurdly pure experiment in facial empathy. It arouses us us by our sense of the story unfolding elsewhere, somewhere behind us, enhanced by lyrical vocalise and brusque sound effects, but above all by these eloquent expressions. It’s a feast for our mirror neurons. If you’re interested in reaction shots, you have to recall Dreyer remarking that “The human face is a landscape that you can never tire of exploring.”

I once asked Kiarostami how he got the remarkable performances in shot/ reverse-shot that we see in films like Through the Olive Trees and The Taste of Cherry. He said that he simply filmed one actor saying all his lines and giving all his reactions, then filmed the other. Often the two actors were never present at the same time, especially when he shot the car sequences. This montage-based approach, creating a synthetic space simply by cutting, has been taken to an extreme in Shirin, where the soundtrack supplies the reverse shot we never see. We’re told that Kiarostami filmed his female actors here reacting to dots on a board above the camera! Indeed, Kiarostami claims he decided on the Shirin story after filming the faces. Despite that, Shirin becomes one of the great ensemble pieces of screen acting, although the actors almost never share a real time and space. (Take that, green-screen wizards!) Like Godard, Kiarostami has been busy reinventing the Kuleshov effect (perhaps by way of Bresson).

This catalogue of female reactions to a tale of spiritual love reminds us that for all the centrality of men to his cinema, Kiarostami has also portrayed Iranian women as decisive, if sometimes mysterious, individuals. Women stubbornly go their own way in Through the Olive Trees and Ten. The premises of Shirin were sketched in his short, “Where Is My Romeo?” in Chacun son cinema (2007), in which women watch a screening of Romeo and Juliet. But the sentiments of that episode are given a dose of stringency here, particularly in one line Shirin utters: “Damn this man’s game that they call love!”

One last note: Kiarostami built movie production into the plot of Through the Olive Trees. Now he has given us the first fiction film I know about the reception of a movie, or at least a heightened idea of a movie. What we see, in all these concerned, fascinated faces and hands that flutter to the face, is what we spectators look like—from the point of view of a film.

For more on the production background, see the lengthy interview with Kiarostami here.

Showing what can’t be filmed

DB, again:

People tend to think that documentary films are typified by two conditions. First, the events we see are unstaged, or at least unstaged by the filmmaker. If you mount a parade, the way that Coppola staged the Corpus Christi procession in The Godfather Part II, then you aren’t making a documentary. But if you go to a town that is holding such a procession and shoot it, you are making a doc—even though the parade was organized to some extent by others. Fiction films stage their events for the camera, but documentaries, we tend to think, capture spontaneous happenings.

Secondly, in a documentary the camera is seizing those events photographically. The great film theorist André Bazin saw cinema’s defining characteristic as its capacity to record the actual unfolding of events with little human intervention. All the other arts rely on human creation at a basic level: the novelist selects words, the painter chooses colors. But the photographer or filmmaker employs a machine that impassively records what is happening in front of it. “All the arts are based on the presence of man,” Bazin writes; “only photography derives an advantage from his absence.” This isn’t to say that cinema can’t be artful, only that it offers a different sort of creativity than we find in the traditional arts. The filmmaker works not with pure imaginings but obstinate chunks of actual time and space.

Given these two intuitions, unstaged events and direct recording of them, it would seem impossible to consider an animated film as a documentary. Animated films consist of almost completely staged tableaus—drawings, miniatures, clay, even food or wood shavings (in the works of Jan Svankmajer). And animated movies offer no recording in Bazin’s sense of capturing the flow of real time and space. These films are made a frame at a time, and the movement we see onscreen doesn’t derive from movement that occurred in reality. And of course you can make an animated film without a camera, for instance by painting directly on film or assembling computer-generated imagery.

Recently, however, we’ve been faced with animated films that claim documentary validity. How is this possible? Maybe we need to rethink our assumptions about what documentary is.

In certain types of documentaries, especially those in the Direct Cinema or cinéma vérité traditions, the assumption that we’re seeing spontaneously occurring events holds good. But a documentary can consist wholly of staged footage. Think back to those grade-school educational shorts showing a tour of a nuclear power plant. Every awkward passage of dialogue recited by the hard-hatted, white-coated supervisor was scripted. The whole show was planned and rehearsed, but that doesn’t detract from the factual content of the film.

Go further. Recall those attack maps that are shown in war films, tracing the progress of an army through enemy terrain. Now imagine an entire film made of those animated maps. The maps might even be enhanced with a few cartoon images, as in the above shot from one of the Why We Fight films. The film would be entirely designed, presenting no spontaneous reality being captured by the camera. Yet it would plainly be a documentary, telling us that, say, the Germans marched into the Sudetenland in 1938 and proceeded on to Poland. So we don’t need photographic recording of actual events to count a film as a documentary either. Both the staging and the recording conditions don’t have to be present for a film to count as a documentary.

I’m not saying that the claims advanced in my nuclear-power film or my attack-map movie would necessarily be accurate. They might be erroneous or inconclusive or false. But that possibility looms for any documentary. The point is that the films, presented and labeled as documentaries, are thereby asserting that the claims and conclusions are true.

Film theorist Noël Carroll defines documentary as the film of “purported fact.” Carl Plantinga makes a similar point in saying that documentaries take “an assertive stance.” Both these writers argue that we take it for granted that a documentary is claiming something to be true about the world. The persons and actions are to be taken as representing states of affairs that exist, or once existed. This is not something that is presumed by The Gold Rush, Magnificent Obsession, or Speed Racer. These films come to us labeled as fictional, and they do not assert that their events and agents ever existed.

This isn’t just a case of a professor stating something obvious in a fancy way. Once we see documentary films as tacitly asserting a state of affairs to be factual, we can see that no particular sort of images guarantees a film to be a doc.

Take the remarkable documentaries made by Adam Curtis. These are in a way very old-fashioned. Blessed with a voice whose authoritative urgency makes you think that at last the veils are being ripped away, Curtis mounts detailed arguments framed as historical narratives. Freudian theory shaped the emergence of public relations, which was in turn exploited not just by business but by government (Century of the Self). Islamic fundamentalism grew up intertwined with US Neoconservatism, both being reactions to perceptions that the West was becoming heartlessly materialistic (The Power of Nightmares). Mathematical game theory came to form politicians’ dominant conception of human behavior and civic community (The Trap). The almost uninterrupted flow of Curtis’s voice-over commentary could be transcribed and published as a piece of nonfiction. True, there are some interpolated talking heads, but those experts’ statements could be printed as inset quotations.

What’s particularly interesting is that Curtis’ rapid-fire declamation accompanies images that often seem not to illustrate it, or at least not very firmly. Like the found footage in the preacher’s sermon “Puzzling Evidence” in True Stories, Curtis’ images are enigmatic, tangential, or metaphorical.

Here are a few seconds from the start of The Power of Nightmares. Eyes are staring upward, as if possessed.

We hear: [Our politicians] say that they will rescue us from dreadful . . .

The eyes are replaced by a shot of a man wearing a cowl, and as this image zooms back the commentary continues.

. . . dangers that we cannot see and do not . . .

Cut to a magician or mime demanding silence.

. . . understand.

Cut to rockets being fired.

And the greatest danger . . .

Cut to a procession of cars, seen from above, rounding a corner into a government compound at night.

. . . of all is international terrorism.

Cut to shot of security agent staring at us.

The ominous, not to say paranoid, tenor of the sequence is aided by the unexpected juxtapositions. For instance, you’d think that the shot of the iconic terrorist (anonymous, with automatic weapon) would be synchronized with the final line of the commentary, referring to “international terrorism.” Instead the commentary links the mention of terrorism to an image of government deliberation, and then to an image of surveillance (aimed at us, but also perhaps suggesting the previous high-angle shot was the spy’s POV). The wild-eyed close-up might belong to a terrorist, but is accompanied by claims about rescuing us from fearsome threats, so the eyes could also belong to someone panicked–especially since they contrast immediately with the sober eyes of the gunman in the cowl. Perhaps the first shot represents the fearful public ready to be led by the politicians playing on fear. And the insert shot of the mime becomes sinister but also comic, perhaps debunking the official position that our dangers are unseen and unknowable. In all, the sequence bubbles with associations that are less fixed and more ambiguous than we’re likely to find in a more orthodox documentary, like Jarecki’s Why We Fight.

My point isn’t to analyze the image/ sound relations in Curtis’s work, a task that probably demands a whole book. (This sequence takes a mere eleven seconds.) I simply want to propose that regardless of what pictures Curtis shows, his films are documentaries in virtue of a soundtrack constructed as a discursive argument that makes truth claims. The picture track often works on us less as supporting evidence than as a stream of associations, the way metaphors or analogies give thrust to a persuasive speech.

Just as we could have an account of Germany’s 1938 invasion of Czechoslovakia presented in cartoon form, we could imagine The Power of Nightmares illustrated with political cartoons. Once we’ve pried the image track loose from the assertions on the soundtrack, anything goes.

One example much on our minds now is Waltz with Bashir. Ari Folman interviews former Israeli soldiers. But instead of using film footage of their conversations and, say, still photos of the events in Lebanon they took part in, he provides (until the final sequence) drawings a bit in the Eurocomics mold of Tardi or Marc-Antoine Mathieu. The result takes the form of a memoir, admittedly. But in both literature and cinema, memoir is a nonfiction genre.

Another memoir supports the point. Marjane Satrapi’s autobiographical graphic novels, Persepolis and Persepolis 2, assert factual claims about her life. The claims are presented as drawings and texts rather than simply as texts, but that doesn’t change the fact that she presents agents and actions purported to have existed. True, on film the people whom she remembers are represented through voice actors speaking lines she wrote. But as with written memoirs (especially those that claim to remember conversations taking place fifty years ago), we can always be skeptical about whether the events presented actually took place.

Another memoir supports the point. Marjane Satrapi’s autobiographical graphic novels, Persepolis and Persepolis 2, assert factual claims about her life. The claims are presented as drawings and texts rather than simply as texts, but that doesn’t change the fact that she presents agents and actions purported to have existed. True, on film the people whom she remembers are represented through voice actors speaking lines she wrote. But as with written memoirs (especially those that claim to remember conversations taking place fifty years ago), we can always be skeptical about whether the events presented actually took place.

Turning Satrapi’s published memoir into an animated film did not change its status as a documentary. If we had contrary evidence, we could charge her with fibbing about her family life, her rebelliousness, or her life in Europe. But we’d be questioning the presumptive assertions the film makes, not the fact that it is drawn and dubbed rather than photographed from life.

We’re tempted to see the animation in these films as adding a level of distance from reality. We’re so used to fly-on-the-wall documentaries that we may be suspicious of the cobra-like caricatures of the female teachers in Persepolis or the hallucinatory dawn bombardment in Bashir. Yet animation can show things, like the Israeli veterans’ dreams, that lie outside the reach of photography. And the artificiality doesn’t dilute the claims about what the witnesses say happened any more than does purple prose in an autobiography. In fact, the stylization that animation bestows can intensify our perception of the events, as metaphors and vivid imagery in a written memoir do.

I realize I’m pointing toward a slippery slope here. Strip off the image track from Aardman‘s Creature Comforts and you have impromptu recordings of ordinary people talking about their lives. Those monologues could have been accompanied by documentary-style talking heads. Does that make Creature Comforts a documentary? I’d say not because the film doesn’t come to us labeled that way; it’s presented as comic animation using found soundtracks (like the movie based on the Lenny Bruce routine Thank You Mask Man). Then there are Bob Sabiston‘s rotoscoped films like Waking Life and The Even More Fun Trip, recently released on Wholphin no. 7. The latter (left) takes another documentary form, the home movie, as the basis for its animation. This seems to me an instance where the documentary category has the edge, but it’s a surely a borderline case.

I realize I’m pointing toward a slippery slope here. Strip off the image track from Aardman‘s Creature Comforts and you have impromptu recordings of ordinary people talking about their lives. Those monologues could have been accompanied by documentary-style talking heads. Does that make Creature Comforts a documentary? I’d say not because the film doesn’t come to us labeled that way; it’s presented as comic animation using found soundtracks (like the movie based on the Lenny Bruce routine Thank You Mask Man). Then there are Bob Sabiston‘s rotoscoped films like Waking Life and The Even More Fun Trip, recently released on Wholphin no. 7. The latter (left) takes another documentary form, the home movie, as the basis for its animation. This seems to me an instance where the documentary category has the edge, but it’s a surely a borderline case.

Animated documentaries are likely to remain pretty far from our prototype of the mode. Still, we should be grateful that even imagery that seems to be wholly fictional—animated creatures—can present things that really happen in our world. This mode of filmmaking can bear vibrant witness to things that cameras might not, or could not, or perhaps should not, record on the spot.

André Bazin’s arguments for the documentary basis of cinema are set out in “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” in What Is Cinema? ed. and trans. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), 9-16. Noël Carroll’s argument that documentaries are framed as presenting “purported fact” can be found in Theorizing the Moving Image (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 224-259. On the “assertive stance” of documentaries, see Carl Plantinga, Rhetoric and Representation in Nonfiction Film (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 15-25. Errol Morris interviews Adam Curtis here. Thanks to Mike King for pointing me toward The Even More Fun Trip.

PS 10 March: Harvey Deneroff writes:

Very much enjoyed your post on animated documentaries, a topic of some interest to and often discussed in the animation studies community. There was a panel on it during last year’s Society for Animation Studies conference and there will also be one at this year’s as well.

Two recent Oscar recipients for Best Animated Short Subject are also documentaries: Chris Landreth’s wonderful computer animated Ryan (produced by the NFB about animator Ryan Larkin, and features a lot of talking heads) and John Canemaker’s The Moon and the Son: An Imagined Conversation, which is about Canemaker’s father and mixes animation with home movies and photographs.

At least two winners in the Oscar Documentary Short Subject category were largely animated: Chuck Jones’ So Much for So Little (WB, 1949, which I believe was made for the US Public Health Service) and Norman McLaren’s Neighbours. The Story of Time, a 1951 British documentary which featured stop motion animation was nominated in the same category.

Also, the International Leipzig Festival for Documentary and Animated Film includes a section for animated documentary films.

Thanks to Harvey for this. I’m not sure I’d categorize Neighbours as a doc, but it’s a long time since I’ve seen it. On Harvey’s site he also has a note quoting Ari Folman on the difficulty of funding animated docs. And thanks to Ryan Kelly and Pete Porter for reminding me of Winsor McCay’s Sinking of the Lusitania from 1918.