Archive for the 'Film technique: Sound' Category

Grandmaster flashback

DB here:

Elsewhere I’ve sung the glories of Turner Classic Movies. Would that the other basic-cable staple, the Fox Movie Channel, were as committed to classic cinema. It’s curious that a studio with a magnificent DVD publishing program (the Ford boxed set, the Murnau/ Borzage one) is so lackluster in its broadcast offerings. Fox was one of the greatest and most distinctive studios, and its vaults harbor many treasures, including glossy program pictures that would still be of interest to historians and fans. Where, for instance, is Caravan (1934), by the émigré director Erik Charell who made The Congress Dances (1931)? Caravan‘s elaborate long takes would be eye candy for Ophuls-besotted cinephiles.

Occasionally, though, the Fox schedulers bring out an unexpected treat, such as the sci-fi musical comedy Just Imagine (1930). Last month, the main attraction for me was The Power and the Glory (1933), directed by William K. Howard from a script by Preston Sturges.

This was an elusive rarity in my salad days. As a teenager I read that it prefigured Citizen Kane, presenting the life of a tycoon in a series of daring flashbacks. I think I first saw it in the late 1960s at a William K. Everson screening at the New School for Social Research. I caught up with it again in 1979, at the Thalia in New York City, on a double bill with The Great McGinty (1940). In my files, along with my scrawls on ring-binder paper, is James Harvey’s brisk program note, which includes lines like this: “One of Sturges’ achievements was to make movies about ordinary people that never ever make us think of the word ‘ordinary.’” I was finally able to look closely at The Power and the Glory while doing research for The Classical Hollywood Cinema (1985). The UCLA archive kindly let me see a 16mm print on a flatbed viewer.

So after a lapse of twenty-eight years I revisited P & G on the Fox channel last month. It does indeed prefigure Kane, but I now realize that for all its innovations it belongs to a rich tradition of flashback movies, and it can be correlated with a shorter-term cycle of them. Rewatching it also teased me to think about flashbacks in general, and to research them a little. You see, I am very fond of what contemporary practitioners like to call broken timelines.

A trick, an old story

On our subject for today, the indispensible book, which ought to be brought back into print or archived online, is Maureen Turim’s Flashbacks in Film: Memory and History (Routledge, 1989). We may think of the flashback as a modern technique, but Turim shows that flashbacks have been a mainstay of filmic storytelling since the 1910s.

On our subject for today, the indispensible book, which ought to be brought back into print or archived online, is Maureen Turim’s Flashbacks in Film: Memory and History (Routledge, 1989). We may think of the flashback as a modern technique, but Turim shows that flashbacks have been a mainstay of filmic storytelling since the 1910s.

Although the term flashback can be found as early as 1916, for some years it had multiple meanings. Some 1920s writers used it to refer to any interruption of one strand of action by another. At a horse race, after a shot of the horses, the film might “flash back” to the crowd watching. (See “Jargon of the Studio,” New York Times for 21 October 1923, X5.) In this sense, the term took on the same meaning as then-current terms like “cut-back” and “switch-back.” There was also the connotation of speed, as “flash” was commonly used to denote any short shot.

But around 1920 we also find the term being used in our modern sense. You can find it in popular fiction; one short story has its female protagonist remembering something “in a confused flashback.” F. Scott Fitzgerald writes in The Beautiful and Damned of 1922:

Anthony had a start of memory, so vivid that before his closed eyes there formed a picture, distinct as a flashback on a screen.

At about the same time writers on theatre start to adopt the term and credit it to film. A historian of drama writes in 1921 of a play that rearranges story order:

The movies had not yet invented the flashback, whereby a thing past may be repeated as a story or a dream in the present.

Within film circles, there were signs of an exasperation with the device. One 1921 writer calls the flashback a “murderous assault on the imagination.” Turim quotes a New York Times review of His Children’s Children (1923):

For once a flash-back, as it is made in this photoplay, is interesting. It was put on to show how the older Kayne came to say his prayers.

In the same year, a critic discusses Elmer Rice’s On Trial, an influential 1911 stage play. Rice employs

a dramatic technique which up to its time was probably unique, though since then the ever recurrent “flash back” of the movies has made the trick an old story.

During the 1930s, although some critics and filmmakers employed older terms like “switch back” and “retrospect,” flashback seems to have become the standard label. It denoted any shot or scene that breaks into present-time action to show us something that happened in the past. It probably speaks to the intuitive and informal nature of filmmaking that writers and directors didn’t feel a need to name a technique that they were using confidently for two decades.

The early flashback films pretty much set the pattern for what would come later. Turim shows that all the sorts we find today have their precedents in the 1910s and 1920s. Adapting her typology a little bit, we can distinguish between character-based flashbacks and “external” ones.

A character-based flashback may be presented as purely subjective, a person’s private memory, as in Letter to Three Wives or The Pawnbroker or Across the Universe. There’s also the flashback that represents one character’s recounting of past events to another character, a sort of visual illustration of what is told. This flashback is often based on testimony in a trial or investigation (Mortal Thoughts, The Usual Suspects), but it may simply involve a conversation, as in Leave Her to Heaven, Titanic, or Slumdog Millionaire. It can also be triggered by a letter or diary, as happens with the doubly-embedded journals in The Prestige.

An alternative is to break with character altogether and present a purely objective or “external” flashback. Here an impersonal narrating authority simply takes us back in time, without justifying the new scene as character memory or as illustration of dialogue. The external flashback is uncommon in classic studio cinema (although see A Man to Remember, 1938) but was common in the 1900s and 1910s and has returned in contemporary cinema. Typically the film begins at a point of crisis before a title appears signaling the shift to an earlier period. Recent examples are Michael Clayton (“Three days earlier”), Iron Man (“36 Hours Before”), and Vantage Point (“23 Minutes Earlier”).

In current movies, flashbacks can fall between these two possibilities. Are the flashbacks in The Good Shepherd the hero’s recollections (cued by him staring blankly into space) or more objective and external, simply juxtaposing his numb, colorless life with the past disintegration of his family? The point would be relevant if we are trying to assess how much self-knowledge he gains across the present-time action of the film.

Rationales for the flashback

What purposes does a flashback fulfill? Why would any storyteller want to arrange events out of chronological order? Structurally, the answers come down to our old friends causality and parallelism.

Most obviously, a flashback can explain why one character acts as she or he does. Classic instances would be Hitchcock’s trauma films like Spellbound and Marnie. A flashback can also provide information about events that were suppressed or obscured; this is the usual function of the climactic flashback in a detective story, filling in the gaps in our knowledge of a crime.

By juxtaposing two incidents or characters, flashbacks can enhance parallels as well. The flashbacks in The Godfather Part II are positioned to highlight the contrasts between Michael Corleone’s plotting and his father’s rise to power in the community. Citizen Kane’s flashbacks are famous for juxtaposing events in the hero’s life to bring out ironies or dramatic contrasts.

Of course, flashbacks need not explain or clarify things; they can make things more complicated too. We tend to think of the “lying flashback” as a modern invention (a certain Hitchcock film has become the prototype), but Turim shows that The Goose Woman (1925) and Footloose Widows (1926) did the same thing, although not with the same surprise effect. Kristin points out to me that an even earlier example is The Confession (1920), in which a witness at a trial supplies two different versions of a killing we have already (sort of) seen.

At the limit, flashbacks can block our ability to understand characters and plot actions. This is perhaps best illustrated by Last Year at Marienbad, but the dynamic is already there in Jean Epstein’s La Glace à trois faces (“The Three-Sided Mirror,” 1927).

I argue in Poetics of Cinema that, at bottom, flashbacks are tactics fulfilling a broader strategy: breaking up the story’s chronological order. You can begin the film at a climactic moment; once the viewers are hooked, they will wait for you to move back to set things up. You can create mystery about an event that the plot has skipped over, then answer the question through a flashback. You can establish parallels between past and present that might not emerge so clearly if the events were presented in 1-2-3 order. Consequently, you can justify the switch in time by setting up characters as recalling the past, or as recounting it to others.

Having a character remember or recount the past might seem to make the flashback more “realistic,” but flashbacks usually violate plausibility. Even “subjective” flashbacks usually present objective (and reliable) information. More oddly, both memory-flashbacks and telling-flashbacks usually show things that the character didn’t, and couldn’t, witness.

I don’t suggest that recollections and recountings are merely alibis for time-juggling. They bring other appeals into the storytelling mix, such as allegiance with characters, pretexts for point-of-view experimentation, and so on. Still, the basic purpose of nonchronological plotting, I think, is to pattern information across the film’s unfolding so as to shape our state of knowledge and our emotional response in particular ways. Scene by scene and moment by moment, flashbacks play a role in pricking our curiosity about what came before, promoting suspense about what will happen next, and enhancing surprise at any moment.

A trend becomes a tradition

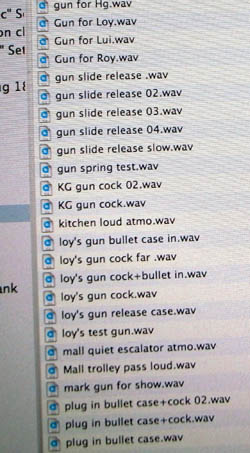

When The Power and the Glory was released in August 1933, it was part of a cycle of flashback films. The Trial of Mary Dugan (1929), The Trial of Vivienne Ware (1932), and other courtroom films rendered testimony in flashbacks. A film might also wedge a brief or extended flashback into an ongoing plot. The most influential instance was probably Smilin’ Through (1931), which is notable for using a crane shot through a garden to link present and past.

When The Power and the Glory was released in August 1933, it was part of a cycle of flashback films. The Trial of Mary Dugan (1929), The Trial of Vivienne Ware (1932), and other courtroom films rendered testimony in flashbacks. A film might also wedge a brief or extended flashback into an ongoing plot. The most influential instance was probably Smilin’ Through (1931), which is notable for using a crane shot through a garden to link present and past.

Also well-established was the extended insert model. Here we start with a critical situation that triggers a flashback (either subjective or external), and this occupies most of the movie. Digging around, I found these instances, but I haven’t seen all of them; some don’t apparently survive.

- Behind the Door (1919): An old sea salt recalls life in World War I and, back in the present, punishes the man responsible for his wife’s death. A ripoff of Victor Sjöström’s Terje Vigen (1917)?

- An Old Sweetheart of Mine (1923): A husband goes through a trunk in an attic and finds a memento that reminds him of childhood sweetheart. The pair grow up and marry, facing tribulations. At the end, back in the present, she comes to the attic with their kids.

- His Master’s Voice (1925): Rex the dog is welcomed home from the war. An extended flashback shows his heroic service for the cause, and back in the present he is rewarded with a parade.

- Silence (1926): A condemned man explains the events that led up to the crime. Back in the present, on his way to be executed, he is saved.

- Forever After (1926): On a World War I battlefield, a soldier recalls what brought him there.

- The Woman on Trial (1927): A defendant recalls her past.

- The Last Command (1928): One of the most famous flashback films of the period. An old movie extra recalls his life in service of the tsar.

- Mammy (1930): A bum reflects on the circumstances leading him to a life on the road.

- Such is Life (1931): A ghoulish item. A fiendish scientist confronts a young man with the corpse of the woman he loves. A flashback to their romance ensues.

- The Sin of Madelon Claudet (1931; often cablecast on TCM): A young wife bored with her husband is told the story of a neighbor woman who couldn’t settle down.

- Two Seconds (1932): A man about to be executed remembers, in the two seconds before death, what led him here. A more mainstream reworking of a premise of Paul Fejos’s experimental Last Moment (1928), which is evidently lost.

An interesting variant of this format is Beyond Victory, a 1931 RKO release. The plot presents four soldiers on the battlefield, each one recalling his courtship of the woman he loves back home. The principle of assembling flashbacks from several characters was at this point prised free of the courtroom setting, and multiple-viewpoint flashbacks became important for investigation plots like Affairs of a Gentleman (1934), Through Different Eyes (1942), The Grand Central Murder (1942), and of course Citizen Kane, itself a sort of mystery tale.

Why this burst of flashback movies? It’s a good question for research. One place to look would be literary culture. The technique of flashback goes back to Homer, and it recurs throughout the history of both oral and written narrative. Literary modernism, however, made writers highly conscious of the possibility of scrambling the order of events. From middlebrow items like The Bridge of San Luis Rey (1927) to high-cultural works by Dos Passos and Faulkner, elaborate flashbacks became organizing principles for entire novels. It’s likely that Sturges, a Manhattanite of wide literary culture, was keenly aware of this trend.

It’s just as likely that he noticed similar developments in another medium. By 1931, when Katharine Seymour and J. T. W. Martin published How to Write for Radio (New York: Longmans, Green), they could devote considerable discussion to frame stories and flashbacks in radio drama (pp. 115-137). Especially interesting for Sturges’ film, radio programs were letting the voice of the announcer or the storyteller drift in and out of the action that was taking place in the past.

For whatever reasons, the technique became more common. The year 1933 saw several flashback films besides The Power and the Glory. In the didactic exploitation item Suspicious Mothers, a woman recounts her wayward path to redemption. Mr. Broadway offers an extensive embedded story using footage from another film (a common practice in the earliest days). Terror Aboard begins with the discovery of corpses on a foundering yacht, followed by an extensive flashback tracing what led up the calamity. A borderline case is the what-if movie Turn Back the Clock (1933). Ever-annoying Lee Tracy plays a small businessman run down by a car. Under anesthesia, he reimagines his life as it might have been had he married the girl he once courted. Call it a rough draft for the “hypothetical flashbacks” that Resnais was to exploit in his great La Guerre est finie.

The point of this cascade of titles is that in writing The Power and the Glory, Sturges was working with a set of conventions already in wide circulation. His inventiveness stands out in two respects: the handling of voice-over and the ordering of the flashbacks.

Now I’m about to divulge details of The Power and the Glory.

Narratage, anyone?

The film begins with what became a commonplace opening gesture of film, fiction, and nonfiction biography: the death of the protagonist. We are at the funeral of Thomas Garner, railroad tycoon. His best friend and assistant Henry slips out of the service. After visiting the company office, Henry returns home. Sitting in the parlor with him, his wife castigates Garner as a wicked man. “It’s a good thing he killed himself.” So we have the classic setup of retrospective suspense: We know the outcome but become curious about what led up to it.

Henry’s defense of Garner launches a series of flashbacks. As a boyhood friend, Henry can take us to three stages of the great man’s life: adolescence, young manhood, and late middle age. Scenes from these time periods are linked by returns to the narrating situation, when Henry’s wife will break in with further criticisms of Garner.

Sturges boasted in a letter to his father: “I have invented an entirely new method of telling stories,” explaining that it combines silent film, sound film, and “the storytelling economy and the richness of characterization of a novel.” At the time, the Paramount publicists trumpeted that the film employed a new storytelling technique labeled narratage, a wedding of “narrating” and “montage.” One publicity item called it “the greatest advance in film entertainment since talking pictures were introduced.” Hyperbole aside, what did Sturges have in mind?

There is evidence that some screenwriters were rethinking their craft after the arrival of sound filming. Exhibit A is Tamar Lane’s book, The New Technique of Screen Writing (McGraw-Hill, 1936). Lane suggests that the talking picture’s promise will be fulfilled best by a “composite” construction blending various media. From the stage comes dialogue technique and sharp compression of action building to a strong climax. From the novel comes a sense of spaciousness, the proliferation of characters, a wider time frame, and multiple lines of action. Cinema contributes its own unique qualities as well, such as the control of tempo and a “pictorial charm” (p. 28) unattainable on the stage or page.

Vague as Lane’s proposal is, it suggests a way to think about the development of Hollywood screenwriting at the time. Many critics and theorists believed that the solution to the problem of talkies was to minimize speech; this is still a common conception of how creative directors dealt with sound. But Lane acknowledged that most films would probably rely on dialogue. The task was to find engaging ways to present it. Several films had already explored some possibilities, the most notorious probably being Strange Interlude (1932). In this MGM prestige product, the soliloquys spoken by characters in O’Neill’s play are rendered as subjective voice-over. The result, unfortunately, creates a broken tempo and overstressed acting. A conversation will halt, and through changes of facial expression the performer signals that what we’re now hearing is purely mental.

The Power and the Glory responds to the challenge of making talk interesting in a more innovative way. For one thing, there is the sheer pervasiveness of the voice-over narration. We’re so used to seeing films in which the voice-over commentary weaves in and out of a scene’s dialogue that we forget that this was once a rarity. Most flashback films in the early sound era had used the voice-over to lead into a past scene, but in The Power and the Glory, Henry describes what we see as we see it.

Most daringly, in one scene Henry’s voice-over substitutes for the dialogue entirely. Young Tom and Sally are striding up a mountainside, and he’s summoning up the nerve to propose marriage. What we hear, however, is Henry at once commenting on the action and speaking the lines spoken by the couple, whose voices are never heard.

This scene, often commented upon by critics then and now, seems have exemplified what Sturges late in life recalled “narratage” to be. Describing that technique in his autobiography, he wrote: “The narrator’s, or author’s, voice spoke the dialogue while the actors only moved their lips” (p. 272).

So one of Sturges’ innovations was to use the voice-over not only to link scenes but to comment on the action as it played out. In her pioneering book Invisible Storytellers: Voice-Over Narration in American Fiction Film (Univesity of California Press, 1988), Sarah Kozloff has argued that the pervasiveness of Henry’s narration has no real precedent in Hollywood, and few successors until 1939 (pp. 31-33). (There’s one successor in Sacha Guitry’s Roman d’un tricheur.) The novelty of the device may have led Sturges and Howard toward redundancies that we find a little labored today. The transitions into the past from the frame story are given rather emphatically, with Henry’s voice-over aided by camera movements that drift away from the couple. (Compare the crisp shifts in Midnight Mary, below.) Henry’s comments during the action are sometimes accentuated by diagonal veils that drift briefly over the shot, as if assuring us that this speech isn’t coming from the scene we see.

The “montage” bit of “narratage” also invokes the idea of a series of sequences guided by the voice-over narrator. The concept might also have encompassed the most famous innovation of The Power and the Glory: Sturges’ decision to make Henry’s flashbacks non-chronological.

Even today, most flashback films adhere to 1-2-3 order in presenting their embedded, past-tense action. But Sturges noticed that in real life people often recount events out of order, backing and filling or free-associating. So he organized The Power and the Glory as a series of blocks. Each block contains several scenes from either boyhood, youth, or middle age. Within each block, the scenes proceed chronologically, but the narration skips around among the blocks.

For example, a block of boyhood scenes gives way to a set showing Garner, now in middle age, ordering around his board of directors. The next cluster of flashbacks returns to Garner’s youth and his courtship of his first wife, Sally. Then we are carried back to his middle age, with scenes showing Garner alienated from Sally and his son Tommy but also attracted to the young woman Eve. And from there we return to Garner’s early married life with Eve.

To keep things straight, Sturges respects chronology along another dimension. Not only do the scenes within each block follow normal order, but the plotlines developing across the three phases of Garner’s life are given 1-2-3 treatment. In one block of flashbacks, we see Tom and Sally courting. When we return to that stage of their lives in another block, they are happily married. The next time we see Garner as a young man, he is improving himself by attending college. The later romance with Eve develops in a similar step-by-step fashion across the blocks devoted to middle age.

A major effect of the shuffling of periods is ironic contrast. Maureen Turim points out that seeing different phases of Garner’s life side by side points up changes and disparities. In his youth, Tom watches the birth of his son with awe; in the next scene, we are reminded what a wastrel young Tommy turned out to be.

The juxtaposition of time frames also nuances character development. As Sally ages, she turns into something of a nag, quarreling with her husband and pampering Tommy. But in the next sequence we see her young, ambitiously pushing Tom to succeed and willing to undergo sacrifice by taking up his job as a railroad track-walker. The next scenes show Tom in class and in a bar while Sally walks the desolate tracks in a blizzard. She has given up a lot for her husband. In the next scene, set in middle age, Garner confesses his love to Eve but says he could never leave Sally, and the juxtaposition with Sally’s solitary track-walking suggests that he recognizes her sacrifice. And in the following scene, when Sally comes to Garner’s office, she admits that she has become disagreeable and asks if they couldn’t take a trip to reignite their love. The juxtaposition of scenes has turned a caricatural shrew into a woman who is a more complex mixture of devotion, disenchantment, and self-awareness.

Other characters aren’t given this degree of shading—Tommy is pretty much a wastrel, Eve a vamp—but another married couple deepens the central parallel. Meek Henry is dominated by his wife, but by the end she is chastened by what she learns of Garner’s real motives. Critic Andy Horton, in his helpful introduction to Sturges’ published screenplay, indicates that this couple adds a note of contentment to what is otherwise a pretty sordid melodrama of adultery and quasi-incest.

The innovative flashbacks and voice-overs are an important part of the film’s appeal, but director William K. Howard supplied some craftsmanship of his own. Particularly striking are some silhouette effects, low angles, and deep-focus compositions that underscore the parallels between Sally’s suicide and Garner’s impending death.

The original screenplay suggests that Sturges intended to push his innovations further. About halfway through, he starts to break down the time-blocks. In the script, Sally visits Garner while he’s working on a bridge. The next scene shows their son Tommy already grown and spoiled, being taken back into his father’s good graces. Then the script returns to the bridge, where Sally tells Tom she’s pregnant. The interruption of the bridge scene reminds us of how badly their child turned out.

The script jumps back to the birth of the baby. In the film the birth scene plays out in its entirety, but in the screenplay Sturges cuts it off by the scene (retained in the film) showing Garner’s marriage to Eve. The final moments of the birth scene, when Garner prays (“Thou art the power and the glory”), become in the script the very end of the film. Coming after Tom’s death at the hand of his son, this epilogue is a bitter pill, rendered all the harder to take by providing no return to Henry and his wife.

The greater fragmentation of the second part of the script, along with Garner’s death as a sort of murder-suicide and the failure to return to the narrating frame, is striking. It’s as if Sturges felt he could take more chances, counting on his viewers’ familiarity with current flashback conventions and on his film’s firmly established time-shuttling method. But if, as sources report, Sturges’ script was initially filmed exactly as written, then it seems likely that the film’s June 1933 preview provoked the changes we find in the finished product. “The first half of the picture,” he remarked in a letter, “went magnificently, but the storytelling method was a little too wild for the average audience to grasp and the latter half of the picture went wrong in several spots. We have been busy correcting this and the arguments and conferences have been endless.”

Even the compromised film proved difficult for audiences. Tamar Lane, proponent of the “composite” form suitable for the sound cinema, felt that the “retrospects” in The Power and the Glory were too numerous and protracted. Nonetheless, he praised it for its “radical and original cinema handling” (p.34). That handling rested upon tradition—a tradition that in turn encouraged innovations. Once flashbacks had become solid conventions, Sturges could risk pushing them in fresh directions.

Mary remembers

Finally, two more flashy flashback movies from 1933. Some spoilers.

Midnight Mary (MGM, William Wellman) works a twist on the courtroom template. The defendant Mary Martin is introduced jauntily reading a magazine while the prosecutor demands that the jury find her guilty of murder. This also sets up a nice little motif of shots highlighting Loretta Young’s lustrous eyes. The motif pays off with a soft-focus shot of her in jail just before the climax.

As the opening scene ends, Mary is led to a clerk’s office to wait for the verdict. There’s an automatic dose of suspense (Will she be found guilty?) but there’s also considerable curiosity: Whom has she killed? How was she caught?

These questions won’t be answered for some time. Lounging in the clerk’s office, Mary runs her eye runs across the annual reports filling his shelves. The flashbacks, which comprise most of the film, are introduced as close-ups of the volumes’ spines—1919, 1923, 1926, 1927, and so on up to the present. They serve as neatly motivated equivalents of those clichéd calendar pages that ripple through montage sequences of the 1930s.

The flashbacks are motivated as subjective; Mary doesn’t recount her life to the clerk but simply reviews it in her mind. Unlike the flashbacks in The Power and the Glory, they are chronological and without gaps. Nothing is skipped over to be revealed later. As usual, though, once Mary’s recollections have triggered the rearrangement of story order, the flashbacks are filmed as any ordinary scenes would be, including bits of action that she isn’t present to witness. The film is a good example of using the extended-flashback convention chiefly to delay the resolution of the climactic action. Told in chronological order, Mary’s tale of woe would have had much less suspense.

Transitions between present and past are areas open to innovation, and early sound filmmakers took advantage of them. In Midnight Mary, the long flashback closes with gangsters pounding on the door of Mary’s boudoir; this sound continues across the dissolve to the present, with Mary roused from her reverie by a knock on the clerk’s office door. Earlier, one transition into the past begins with Mary blowing cigarette smoke toward the bound volumes on the shelf.

Dissolve to a close-up of one book as smoke wafts over it, and then to a shot of Mary’s gangster boyfriend blowing cigarette smoke out before he sets up a robbery..

At one point the narration supplies a surprise by abruptly shifting into the present. Once Mary has become a prostitute, she is slumped over a barroom table in sorrow, while her pal Bunny consoles her. In a tight shot, Bunny (Una Merkel, always welcome), leans over and says: “Oh, what’s the diff, Mary? A girl’s gotta live, ain’t she?”

Cut directly to the present, with Mary murmuring: “Not necessarily, Bunny. The jury’s still out on that.”

Mary’s reply casts Bunny’s question about needing to live in a new light, since Mary is facing execution, and the use of the stereotyped phrase, “The jury’s still out,” now with a double meaning, reminds us of the present-tense crisis. It is a more crisp and concise link than the transitions we get in The Power and the Glory. But then, Wellman has no need for continuous voice-over, which gives the Sturges/ Howard film its more measured pace.

Filmmakers were concerned with finding storytelling techniques appropriate to the sound film, and these unpredictable links between sequences became characteristic of the new medium. Similar links had appeared in silent films, but they gained smoothness and extra dimensions of meaning when the images were blended with dialogue or music. For more on transitional hooks, go here.

Nora and narratage

The hooks between scenes are perhaps the least outrageous stretches of The Sin of Nora Moran, a Majestic release that, thanks to a gorgeous restoration and a DVD release, has rightly earned a reputation as the nuttiest B-film of the 1930s.

It is a flashback frenzy, boxes within boxes. A District Attorney tells the governor’s wife to burn the apparently incriminating love letters she’s found. In explaining why, the D. A. introduces a flashback (or is it a cutaway?) to Nora in prison. We then move into Nora’s mind and see her hard life, the low point occurring when she’s raped by a lion tamer.

Now we start shuttling between the D. A. telling us about Nora and Nora remembering, or dreaming up, traumatic events. At some points, characters in her flashbacks tell her that what she’s experiencing is not real. In one hazy sequence, her circus pal Sadie materializes in her cell to remind Nora that she killed a man. (Actually, she didn’t.) At other moments Nora’s flashbacks include moments in which she says that if she does something differently, it will change—it being the outcome of the story. At this point another character will point out that they can’t change the outcome because it has already happened . . . of course, since this is a flashback.

By the end, after the governor has had his own flashback to the end of his affair with Nora and after she appears as a floating head, things have gotten out of hand. The rules, if there are any, keep changing. And the whole farrago is propelled by furious montage sequences built out of footage scavenged from other films.

Publicity and critical response around The Sin of Nora Moran implied that the movie followed the “narratage” method. There was surely some influence. Scenes contain fairly continuous voice-over commentary, and director Phil Goldstone occasionally drops in the diagonal veil used in The Power and the Glory. But on the whole this delirious Poverty Row item falls outside the strict contours of Sturges’ experiment. Nora Moran blurs the line separating flashbacks and fantasy scenes, and it illustrates how easily we can lose track of what time zone we’re in. Watching it, I had a flashback of my own—to Joseph Cornell’s Rose Hobart, another compilation revealing that Hollywood conventions are only a few steps from phantasmagorias.

Unwittingly, Nora Moran’s peculiarities point forward to the flashback’s golden age, the 1940s and early 1950s. Then we got contradictory flashbacks, flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks, flashbacks from the point of view of a corpse (Sunset Boulevard) or an Oscar statuette (Susan Slept Here). Filmmakers knew they had found a good thing, and they weren’t going to let it go.

The original screenplay of The Power and the Glory is included in Andrew Horton, ed., Three More Screenplays by Preston Sturges (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998). Sturges’ reflections from the late 1950s are to be found in Preston Sturges by Preston Sturges: His Life in His Words, ed. Sandy Sturges (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1990). The quotations from Sturges’ letters and from publicity about “narratage” can be found in Diane Jacobs, Christmas in July: The Life and Art of Preston Sturges (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 123-129 and James Curtis, Between Flops: A Biography of Preston Sturges (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982), 87.

My citatations of literary uses of the term come from Elliott Field, “A Philistine in Arcady,” The Black Cat 24, 10 (July 1919), 33; Fitzgerald’s The Beautiful and Damned (1922), available here, 433; Samuel A. Eliot, Jr., ed., Little Theater Classics vol. 3 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1921), 120; The Outlook (11 May 1921), 49, available here; review of His Children’s Children, quoted in Turim p. 29; commentary on On Trial, in The New York Times (25 March, 1923), X2.

For more on the history of flashback construction, apart from Maureen Turim’s Flashbacks in Film, see Barry Salt’s Film Style and Technology: History and Analysis, 2nd ed. (London: Starword, 1992), especially 101-102, 139-141. There are discussions of the technique throughout David Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), especially 42-44.

P.S. 15 November 2015: 1940s flashback technique is surveyed in my Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling.

Categorical coherence: A closer look at character subjectivity

Subjective

[NOTE: There are some spoilers here, though I’ve tried to avoid giving away the ends of the films I mention. Teachers who show clips in class would probably want to do the same. Some of the films mentioned here would be good choices to show in their entirety to classes when they study Chapter 3 of Film Art.]

Kristin here—

We have had occasion to mention the Filmies list-serve of the Department of Communication Arts’ Film Studies area here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Current and past students and faculty, sometimes known as the “Badger squad,” share news, links, and requests for information. Once in a while a topic is raised for discussion. These exchanges are usually fascinating, and when we have felt that they might be of interest to a general audience, we have used them as the basis for blog entries. (See here and here.)

Another occasion arose recently, one which relates to the teaching of Film Art: An Introduction. Matthew Bernstein, of Emory University, queried the group about suggestions for teaching a section of the third chapters, “Narrative as a Formal System.” He found that the section, “Depth of Story Information,” gives some students trouble. They can’t grasp the distinction we make between perceptual and mental subjectivity.

Our definitions of the terms go like this. Perceptual subjectivity is when we get “access to what characters see and hear.” Examples are point-of-view shots and soft noises suggesting that the source is distant from the character’s ear. In contrast, “We might hear an internal voice reporting the character’s thoughts, or we might see the character’s inner images, representing memory, fantasy, dreams, or hallucinations. This can be termed mental subjectivity.”

We then go on to give a few examples. The Big Sleep has little perceptual subjectivity, while The Birth of a Nation contains numerous POV shots. We see the heroine’s memories in Hiroshima mon amour and the hero’s fantasies in 8 ½. Filmmakers can use such devices in complex ways, as when in Sansho the Bailiff, the mother’s memory ends not by returning to her in the present, but to her son, apparently thinking of the same things at the same time.

Yeah, but what about …?

Filmmakers don’t always use these categories in straightforward ways. They may oscillate between perceptual and mental representations and events. Films may present narrative events that make the distinction between characters’ perceptions and their mental events ambiguous. That’s why in introducing the concepts, we stress that “Just as there is a spectrum between restricted and unrestricted narration, there is a continuum between objectivity and subjectivity.

Easy to say, but not necessarily so easy to grasp for a student who’s trying to understand these categories. They need to start with simple examples to familiarize themselves with the basic distinction before going on to what the likes of Resnais, Fellini, and Mizoguchi can throw at them. But some students immediately proffering exceptions. As Charlie Keil, of the University of Toronto, put it in his post on the subject, “I hardly need add that students, even the least analytically astute, border on the brilliant when it comes to suggesting examples that provide challenges to categorical coherence.”

Looking over the one and a half pages of the textbook that we devoted to depth of narration, you might find it fairly straightforward. Once you start looking for ways to teach the concepts without bogging down in too many nuances and subcategories, though, the passage does seem challenging. What follows is a suggestion about how someone might go about explaining and utilizing examples. It also points up some ways we might revise this passage of the book for its next edition.

What it’s not

One obstacle that Matthew has found is that students are used to thinking of “subjective” as meaning something like “biased,” as in “here’s my subjective opinion on that.” It might be useful to point out that this is only one meaning of the word. The dictionary definition that comes closest to the way we use it in Film Art is this: “relating to properties or specific conditions of the mind as distinguished from general or universal experience.” For film, we specify that “subjective” means either sharing the characters’ eyes and ears (properties) or getting right inside his or her mind (conditions).

Another misconception comes when students assume that the facial expressions, vocal tones, and gestures used by actors are subjective because they convey the characters’ feelings. Again, best to scotch that notion up front. Those techniques are projected outward from the character, and we observe them. Cinematic subjectivity goes inward.

One step at a time

Another distinction to stress early on is the basic one we make between film technique and function. There are a myriad of film techniques that could be used in either objective or subjective ways. To take a simple example, a low camera angle might indicate the POV of a character lying down and looking up at something; that’s perceptual subjectivity. A low angle of a skyscraper in an establishing shot might simply be the objective narration’s way of showing where a new scene will occur.

In contrast, indicating perceptual and mental subjectivity are two specific kinds of functions. Filmmakers can call upon whatever cinematic techniques they choose, and historically the more imaginative ones have shown immense creativity in trying to convey what characters see and think.

Some films depend heavily upon subjectivity, but objective narration is more common. There are many films that give us little access to characters’ perceptual and mental activities. Apart from The Big Sleep, there are films like Anatomy of a Murder, or virtually anything by Preminger. Most films use subjectivity sparingly. So let’s assume the students can tell that objective narration is the default.

With that out of the way, we can go back to basics. Both perceptual and mental subjectivity depend on being “with” the character in a strong way, as opposed to observing him or her as we would see another person in real life.

Perceptual subjectivity is fairly simple. The camera is in the character’s place, showing what he or she sees. The microphone acts as the character’s ears. Other characters present in the scene could step into the same vantage point and observe the same things.

So the test could run like this: As a viewer, when we see something in a film, is it really present within the scene? Could someone else in the same position see and hear the same things? Or is it a purely mental event, something no one else could see and hear, even if they stood beside the character or stepped into the place where that character had been standing?

If I were teaching the concept of narrational subjectivity as Film Art defines it, I would stress the notion of a continuum. After starting with very clear examples of both perceptual and mental subjectivity, I would progress to more ambiguous, mixed, or tricky instances.

Contributing to this discussion on the Filmies list, Chris Sieving, of the University of Georgia, says he shows a  clip from Lady in the Lake, the film noir where the camera always shows the POV of the detective protagonist. As Chris says, “It seems to effectively get across what perceptual subjectivity means (and how awkward it is in large doses), as well as what is meant by a (highly) restricted range of narration (as is the case with most whodunits).” As Chris also says, Lady in the Lake is a sort of limit case, a film that depends as much on perceptual subjectivity as it’s possible to do. (That’s “our” hand taking the paper in the shot at the right.) One could show several minutes from any section of the film and make the point thoroughly.

clip from Lady in the Lake, the film noir where the camera always shows the POV of the detective protagonist. As Chris says, “It seems to effectively get across what perceptual subjectivity means (and how awkward it is in large doses), as well as what is meant by a (highly) restricted range of narration (as is the case with most whodunits).” As Chris also says, Lady in the Lake is a sort of limit case, a film that depends as much on perceptual subjectivity as it’s possible to do. (That’s “our” hand taking the paper in the shot at the right.) One could show several minutes from any section of the film and make the point thoroughly.

There are other films that contain a lot of POV shots but intersperse them with objective ones. Rear Window is an obvious case. When Jefferies is alone, we see the courtyard events from his POV, a fact which is stressed by his use of binoculars and his long camera lenses to spy on his neighbors. This is clearly perceptual rather than mental. We never doubt that what we see through the hero’s eyes is real; we don’t believe that he’s making things up to entertain himself or because his mind is unbalanced. For one thing, there are two other characters who visit at intervals and see the same things that he does. We and they might question whether Jefferies’ interpretation of what he sees is correct, but we assume that the story’s real events have been conveyed to us through his eyes and ears. Only if we saw something like his fantasy of how he imagines his neighbor might have killed his wife would we move into the mental realm.

These two films foreground their use of POV. Usually, though POV shots are slipped into the flow of the action smoothly. Scenes of characters looking at small objects or reading letters often cut to a POV shot to help us get a look at an important plot element. At intervals during Back to the Future, Marty looks at a picture of himself and his siblings, gradually fading away to indicate that the three of them might never be born if he doesn’t succeed in bringing their parents together. It’s a simple way of reminding us what’s at stake and that Marty’s time to solve the problem is running out.

The Silence of the Lambs uses many POV shots and provides an excellent case of narration switching frequently and seamlessly between objective and subjective. Most of the POV views are seen through Clarice’s eyes, but sometimes through those of other characters. The first view of Lecter is a handheld tracking shot clearly established as what she sees as she walks along the corridor in front of the row of cells.

The scenes of Clarice conversing with Lecter develop from conventional over-the-shoulder shot/ reverse shot to POV shot/ reverse shot as both characters stare directly into the lens. (In Film Art, we use this device as an example of how style can shape the narrative progression of a scene [p. 307, 8th edition]). Other characters have POV shots as well, most noticeably, when Buffalo Bill twice dons night-vision goggles and we briefly see the world as he does.

Occasionally we see the POV of even minor characters, as when Lecter’s attack on his guard is rendered with a quick POV shot of Lecter lunging open-mouthed at the camera and then an objective shot of him grabbing the guard.

In their minds

Let’s jump to the other end of the continuum. Here we find a clear-cut use of mental subjectivity for fantasies, hallucinations, and the like. Obviously no one else present, unless he or she is posited as having special telepathic abilities, can see and hear what takes place only in a character’s mind.

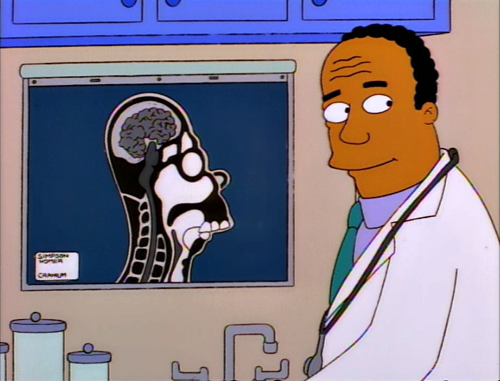

Such fantasies are a running gag on The Simpsons, where Homer’s misinterpretations, distractions, and visions of grandeur are shown either in a thought balloon or superimposed on his skull. In the example above, he abruptly starts “watching” a little cartoon after assuring Lisa that she has his complete attention. No one could mistakenly assume that these exist anywhere but in Homer’s imagination.

In Buster Keaton’s Our Hospitality, the hero receives a letter telling him he has inherited a Southern home. After an image of him thinking there is a dissolve to a view of a large, pillared house. Later, when he arrives at his small, ramshackle house, he stands staring in a similar situation, and here there is a fade-out to his dream house, which abruptly blows up. The humor in the second scene would be impossible to grasp if we didn’t easily understand that the shot of the house exists only in his mind.

Whole films can be built around fantasies. A large central section of Preston Sturges’ black comedy Unfaithfully Yours consists of a husband envisioning three different ways he might kill his supposedly cheating wife, all set to the musical pieces he is conducting at a concert. Fellini’s 8 ½ is only the most obvious example of how the art cinema often brings in fantasies. Other examples include Jaco van Dormael’s Toto le héros or Bergman’s Persona.

Once students have grasped the basic distinction between perceptual and mental subjectivity, it might be useful to emphasize the continuum by moving directly to its center, where the two types coexist.

The middle of the continuum: Ambiguity and simultaneity

Right in the middle of the continuum between the pure cases we find ambiguous cases. Filmmakers can create deliberate, complex, and important effects by keeping it unclear whether what we see is a character’s perception of reality or his/her imaginings.

1961 was a big year for ambiguous subjectivity, with two of the purest cases appearing. One was a genre picture, the other a controversial art film.

The first is the British horror film, The Innocents, directed by Jack Clayton and based on Henry James’s novella, The Turn of the Screw. In several scenes, a new governess at a country estate sees frightening figures whom she takes to be ghosts haunting the two children entrusted to her. We see these figures as she does, but we never see them except when she does. The children behave very oddly in ways that might be consistent with her belief, yet they deny seeing any ghosts. Finally the governess tries to force the little girl to admit that she also sees the silent female figure standing in the reeds across the water. Does the child’s horrified expression reflect her realization that the governess knows about her secret relationship with the ghosts? Or is she simply baffled and frightened by the governess’s increasingly frantic demands that she confess to seeing something that in fact she can’t see?

From the first appearance of the eery figures, the question arises as to whether the governess is imagining the ghosts or they are real, controlling the children, who try to keep them secret. There are apparent clues for either answer. By the end, we arguably are no closer to knowing whether the ghosts are real or figments of the heroine’s imagination.

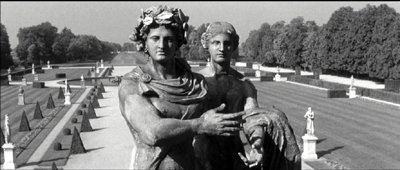

Since Last Year at Marienbad appeared, critics have spilled gallons of ink trying to fathom its symbolism and sort out the “real” story that it tells. Clearly there are contradictions in events, settings, and voiceover narration. The second of the three accompanying images depicts the heroine as the hero’s voiceover describes their first meeting. They talked about the statue that stands beside her, seen against the formal garden of walks lined with pyramid-shaped shrubs. Yet another version of the first meeting starts, this time with the characters and the same statue against a background of a large pool. Later scenes in these locales display the same inconsistencies.

Are such contradictions the result of one character’s fantasies or of the conflicting memories that two characters have of the same event? Or are the contradictions not the products of subjectivity at all but just the playfulness of an objective, impersonal narration, manipulating characters like game pieces to challenge the viewer? (Our analysis of Last Year at Marienbad is available here on David’s website. It and all the Sample Analyses that have been eliminated from Film Art to make room for new essays are available here as pdf’s; the index to them is here, about halfway down the page.)

It’s not a good example of subjectivity to show students, but just as an aside, the screwball comedy Harvey is an interesting case, a sort of reversal of the Innocents situation. The narration withholds a character’s perceptual and mental events. Elwood P. Dowd describes what he sees and hears: a six-foot talking rabbit invisible to us and to all the other characters. The story concerns whether Dowd’s relatives will institutionalize him for insanity, and we assume along with them Harvey is a mere delusion. Thus the narration seems to be objective—or, the ending asks, has it been very uncommunicative, withholding something that the hero really does see and hear? True, throughout the film the framing leaves room for Harvey, as if he were there. One could argue, though, that these framings simply emphasize that the giant rabbit isn’t visible to us or the other characters and hence isn’t likely to really exist.

A film can easily present both perceptual and mental subjectivity at the same time. A POV shot may be accompanied a character’s voice describing his or her thoughts and feelings. Matthew shows his class part of the opening section of The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, where a stroke victim’s extremely limited sight and hearing are rendered in juxtaposition with his voice telling of his reactions to his new situation. It is one of the most extensive and successful uses of such a combination in recent cinema, and it might be very effective in differentiating the two for introductory students.

A scene can also move rapidly back and forth between a character’s perceptions and his or her thoughts. Charlie writes that he shows his students the scenes of Marion Crane driving in Psycho. While the car is moving, almost every alternating shot is a POV framing of the rearview mirror or through the windshield. At that same time, we hear the voices of her lover, her boss, her fellow secretary, and the rich man whose money she has stolen while she imagines how they would react to her crime.

Showing scenes like these, where both types of subjectivity are used and clearly distinguishable might be more useful for students than showing several scenes that contain only one or the other.

Flashbacks, Voiceovers, and Altered States

In his original query to the Filmies, Matthew also said that students have problems with flashbacks: “Particularly, they resist the idea that a flashback is an example of subjective depth in general, even if the flashback unfolds objectively.” I can think of two ways to explain this.

First, classical films tend not to have flashbacks that just start on their own. To be sure, some do: a track-in to an important object and a dissolve can signal the start of a passage from the past, without a character being there. But more often a character is used to motivate the move into the past. A thoughtful look may do it, or a character may describe the past to someone else. In either case, the flashback is coming “from” the character and is assumed to show approximately what he or she is remembering. Occasionally the flashback may be a lie rather than objective truth, as we know from Hitchcock’s Stage Fright, The Usual Suspects, and a few other films.

In Poetics of Cinema’s third essay, David argues that most flashbacks in films are motivated as a character’s memory, but what is shown often strays from what he or she knew or could have known. He suggests that the prime purposes of most flashbacks is to rearrange the order of story events, and the character recalling or recounting simply provides an alibi for the time shift.

So we might think of character-motivated flashbacks as subjective frameworks that also contain objectively conveyed narrative information.

Second, the fact that flashbacks slip in objective information into characters’ memories is a convention. It’s a widely used method for presenting us with two things at once: first, a character’s memories and second, some story information that the viewer needs to have—even if the character couldn’t know about it. As we watch movies, we frequently accept conventions for the sake of being entertained. Beings that travel to Earth from distant galaxies speak English, high school kids can put together shows that wind up triumphing on Broadway, and people who drive up to buildings in crowded cities always find perfect parking spots. In a similar way, implausible mixtures of subjectivity and objectivity in flashbacks is just something we have to accept.

There are two other techniques that didn’t get mentioned during the discussion but that might confuse students.

What about shots showing the vision of a character who is drunk, dizzy, drugged, or otherwise unable to see straight? The most common convention is to include a POV shot that’s out of focus, perhaps accompanied by a bobbing handheld camera. Other characters in the scene, assuming they are not similarly impaired, would not see the surroundings in the same way.

Still, I think the same perceptual/mental distinction holds for such moments. The fuzziness and the lack of coordination are physical effects that are not being imagined by the character. They remain in the perceptual realm. Mental effects of impairment would be dreams or hallucinations. Some examples: the “Pink Elephants on Parade” sequence in Dumbo and the DTs vision of the protagonist of Wilder’s The Lost Weekend. As the title suggests, Altered States takes such mental activities as its subject matter and has many scenes that represent them.

A harder case is voiceover. Are all cases of voiceover subjective? Clearly not. If we have a situation where a character tells a story to a group and his or her voice continues over a flashback, the narration remains objective. We assume that the group can still hear the storyteller. Cases where the voice exists only in the mind, as when a character speaks to himself or herself, but not aloud, are mental subjectivity.

That said, there are many unclear cases. Just what is the status of the narration in Jerry Maguire? Jerry seems to speak directly to us, pointing out things that happen during the action, yet clearly there is no suggestion that he made the film we are watching. The problem is compounded in Sunset Boulevard, where the protagonist not only implicitly addresses us but is also dead. In many cases when a character’s voice is heard over a scene, it might occur to audience members to wonder where the character is or was when speaking these words. And does a character’s voice describing his or her feelings constitute objective or subjective narration? Probably we would want to say that only when the voice is posited as strictly an internal voice, audible only to the character, would we want to dub it subjective.

The problem with voiceovers arises, I think, because it’s such a slippery technique to begin with, and therefore often hard to categorize. Is a character speaking narration over events that happened in the past diegetic sound or nondiegetic? If there’s never an establishment of where and when that character does the narrating, he or she exists in a sort of limbo in between the two states: diegetic because he or she is a character, nondiegetic because he or she is in some ineffable way removed from the story world.

For voiceovers, then, I think it’s best simply to categorize the ones that obviously are straightforwardly objective or subjective. In tricky cases, we just have to admit that not all uses of film technique are easy to pin labels on. But the point of having categories like these isn’t to pin labels. In part knowing them allows us simply to notice things in films that might otherwise remain a part of an undifferentiated flow of images. They enable us to see underlying principles that make films into dynamic systems rather than collections of techniques. They give us ways to organize our thoughts about films and convey them to others. And, though students may doubt this, watching for such things becomes automatic and effortless once we have understood such categories and watched a lot of films. As a child, I don’t think I knew about the concept of editing or ever really noticed cuts. Now I’m aware of every cut in every film I see, and I notice continuity errors and graphic matches and other related techniques, all automatically, without that awareness impinging in the least on my following the story and being entertained. Learning the categories is only the beginning.

Playing with subjectivity

Once students have seen some clear cases of each type of cinematic subjectivity and understand the difference, the teacher could move on to emphasize that filmmakers can play with both in original ways. It’s not really possible in an introductory textbook to discuss all the possibilities—and probably not possible to come up with a typology that would cover every example of subjectivity that could exist across that continuum we mentioned. Imaginative filmmakers will always find new variants on how to use techniques for this purpose. But here are a few intriguing cases.

In his class, Chris shows the scene in Hannah and Her Sisters where the Woody Allen character, a hypochondriac, visits a doctor for some hearing tests. Initially the doctor comes into the room and gives a dire diagnosis of inoperable cancer. After Mickey has reacted to that, a cut takes us back to an identical shot of the doctor entering, but this time he gives Mickey a clean bill of health. The first part of the scene is retroactively revealed to have been a mental event, Mickey’s pessimistic fantasy.

The same sort of thing happens in a more extended way with the familiar “it was only a dream” revelations that make the audience realize that a major part of the plot has been subjective. In a more sophisticated way, as Chris points out, other sorts of mental subjectivity, usually lies or extended fantasies, can be revealed retrospectively, as in The Usual Suspects, Mulholland Drive, and Fight Club.

A flashback from one character’s viewpoint may reveal something new about an earlier scene. In Ford’s The Man who Shot Liberty Valance, the shootout is initially shown through objective narration. Only later in the plot does another character reveals that, unbeknownst to us or the other people present, he had also been present at the shootout. The flashback to his account reveals that the shootout happened very differently from the way we had assumed when first seeing it.

I’ll close with an example from The Silence of the Lambs. This shows how subtle and effective a play with perceptual and mental narration can be. In the scene at the funeral home where a recently discovered body of a murder victim is to be examined, Clarice is left waiting in the midst of a group of state troopers who stare at her. To get out of the situation, she turns and looks into the chapel, where a funeral is taking place. We see her face and then her POV as she surveys the room. A cut shows Clarice suddenly within the chapel, moving forward toward the camera and staring straight into the lens. We will only realize retrospectively that this image begins a fantasy that leads quickly into a memory. Clarice has not actually left her previous position just outside the door.

The next shot is a track forward through the center aisle toward the casket. Since Clarice had been walking in that direction before the cut, we recognize this as a POV and assume that Clarice is continuing to walk. Yet the man in the casket, as we soon will learn, is Clarice’s father. The shot represents a different funeral, one in the past which she has been triggered to remember by her glance into the chapel. The fantasy has become a flashback. A second, similar view of Clarice’s face returns us to her fantasizing adult self, the one remembering this scene but not the one still standing outside the door. A closer view of the father’s casket shows it from a lower vantage-point, as if that of a child.

The reason for the change becomes apparent from a radical change at the next cut, so that the camera is on the far side of the casket, filming from a low angle. The sudden shift moves us away from the adult Clarice in order to show her as a child approaching her father and leaning down to kiss him. A noise pulls Clarice out of her memory, and a cut back to the hallway shows her turning away from the chapel. (As often happens, sound, and particularly music, helps guide us through the scene, marking the beginning and ending of the fantasy/flashback.)

The most experienced film specialist could not track all the rapidly shifting levels of subjectivity in this scene on first viewing. Still, later analysis using some categories of subjective narration can help us appreciate how Demme has woven them into a scene that helps explain Clarice’s motives in becoming an FBI agent and her determination in pursuing her first case.

Categories matter

To some students, the categories I’ve just discussed may seem like trivial distinctions. They’re not. The use of subjective narration is one of the key ways the filmmaker has to engage our thoughts and emotions with the characters. In Psycho, we become involved in Marion Crane’s life in a remarkably short time, partly because of her situation but also partly because Hitchcock keeps us so close to her once she prepares to steal the money. The camera not only frames her closely, but to a considerable degree we see and imagine what she does: her fearful forebodings of how her rash act will turn out. Much the same thing happens with Clarice Starling in The Silence of the Lambs, though there our emotional involvement lasts throughout the film, and we are given glimpses of Clarice’s memories.

Perhaps choosing a scene or two from such films and going through them with the students, trying to imagine what it would be like without the POV shots and the imaginings and the memories, would convince them of the value of learning these categories. After all, the exceptions they find are only exceptional because they play in a zone defined by solid concepts.

[Note added October 24: I should have referred back as well to David’s entry “Three Nights of a Dreamer,” largely on POV.]

Objective

American (Movie) Madness

Grover Crisp and Lea Jacobs outside the University of Wisconsin–Madison Cinematheque.

DB here, again:

He holds sway over thousands of movies and the transfer of hundreds of DVDs. At home he has a high-definition set, but he gets local channels on a rabbit-ears antenna. If that isn’t a working definition of a Film Person, I don’t know what is.

Over the years our UW Film Studies area has hosted many visiting Film Persons, including archivists Chris Horak, Mike Pogorzelski, Joe Lindner, Schawn Belston, and Paolo Cherchi Usai. (1) Being a department centrally interested in film history, we’re eager to screen recent restorations and learn the ins and outs of film archivery.

This year our Cinematheque screened several Sony/ Columbia restorations, running the gamut from Anatomy of a Murder to The Burglar. We wound up our series, and our season, with a stunning print of Frank Capra’s American Madness (1932). To conclude things with a bang, Lea Jacobs, Karin Kolb, and Jeff Smith brought Grover Crisp, Sony’s Senior Vice President of Asset Management, Film Restoration, and Digital Mastering.

Kristin and I had met Grover at the Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna, and after hearing him introduce some restorations, we knew he had to come to Madison. It was a Bologna screening of American Madness that convinced me that we had to show this sparkling print on our campus. Fortunately for us, Grover squeezed a Madison visit into his schedule and suffered the caprices of American Airlines’ delays. We had about two days of his company.

It was a great learning experience. On Thursday 8 May he addressed our colloquium, where he showed two shorts: a 1933 Screen Snapshots installment explaining the process of motion picture production, from script to final product, and a trim 75-second short by his colleague Michael Friend tracing the evolution of filmmaking technology. On Friday Grover introduced American Madness and took questions.

Just a note about terminology: Archives engage in both film preservation and film restoration. Preservation means, as you’d think, saving films for the future. This involves maintaining the materials (prints, negatives, camera material, sound tracks) in surroundings that minimize harm and deterioration. Restoration demands more resources. It involves trying to create an authoritative version of the film as it existed in some earlier point in history. But that’s a complicated matter, as we’ll see.

Archives and assets

Grover brings a Film Person’s sensitivity to the mission of film preservation. What does that mean? For one thing, he takes the long perspective. Film archivists think about how to store and maintain films for decades, even hundreds of years. In an industry geared to short-term cycles, booms and busts and jagged demand curves, a commercial archivist like Grover, or Schawn of Fox, has to reconcile traditional museum standards with market demands, strategic release considerations, and current studio policies. In short, he has to think both about saving the film for a century and about hitting a DVD street date.

Grover explained his obligations at Sony Pictures Entertainment. He manages all film and television materials. That means preserving everything for any future use and restoring some items for video and theatrical screening. It also means that he keeps abreast of current TV and film productions. This gives him a chance to “embed archival needs” into production and postproduction processes. For example, from 1991 to the present, YCM separation masters are prepared for every film. (2) And today, when a film is finished and output digitally onto a negative for release prints, another negative is assembled from the camera negative, the most pristine source, and that goes into cold storage.

Grover supervises a staff of about twenty-five people, six of whom are overseeing film laboratory and audio work full-time. Unlike other studio archives, Sony does not hand off preservation tasks to outside companies. Being a Film Person, Grover asks that for films a new negative be created, and fresh screening prints be prepared.

What impelled a big company like Sony to invest so much in preservation and restoration? Grover explained that the rise of home video taught most studios that their libraries had some value. In particular, executives were impressed by Ted Turner’s 1986 purchase of MGM for its library, which he could recycle endlessly on TBS. They realized that the libraries were genuine assets. Old movies enhanced the firm’s value (if it were to be sold, as many were in those days) and could be exploited through new media platforms, like cable.

The arrival of DVD made all the studios return to their libraries to make high-quality versions of their top titles. Now the high-definition format of Blu-ray will re-start restoration because of the leap in quality it offers.

Sony moved early, partly because it understood new media. When Sony bought Columbia Pictures in 1989, the Japanese executives envisioned a synergy between Sony’s hardware and a movie studio’s software. “One of the first things they asked,” Grover recalls, “was, ‘What’s the condition of the library?’” Soon afterward, Sony set up the first systematic collaboration between studio archivists and museum-based archivists. The Sony Pictures Film Preservation Committee included archivists from Eastman House, the Library of Congress, UCLA, MoMA, the Academy, and other institutions. In addition, Grover modeled Sony’s restoration policies on the exemplary work of legendary UCLA archivist Bob Gitt (whose work on sound restoration we’ve already saluted in another entry).

Digital restoration has been part of the Sony program. The 1997 restoration of Capra’s Matinee Idol (1927), from a Cinémathèque Française print, was the first live-action high-definition restoration from any studio.

Sony holds between 3600 and 5000 titles. It’s impossible to be more precise at this point because in hundreds of cases the rights situation is uncertain. But of the core library, about half to two-thirds of the films are restored. Crisp’s team is at work on about 200 titles at any moment! Many more are restored than warrant DVD release, but they may be available On Demand and via TCM, which has recently acquired cablecast rights to several older Columbia titles.

Restore, yes! But what, and how?

We’re grateful for preservation, but for cinephiles, restoration holds a special thrill. A “restored” Intolerance or Napoleon or von Sternberg movie gets us salivating. This year Cannes ran nine restorations on its program.

But what is a restoration?

We expect that a restoration will provide a film with a better-quality image or soundtrack than we’ve had so far. We often expect as well that a restoration will provide a more complete version of the title. Yet there are problems with both expectations.

First, who’s to say what the quality of the original is? Grover encountered this difficulty in restoring Funny Girl. It was released in the classic Technicolor dye-transfer process, usually considered the gold standard for color cinematography. He assembled five original Technicolor prints and all of them looked different. It turns out that Technicolor prints varied quite a bit. (3) The kicker was that Grover couldn’t make the new dye-transfer 35mm print of Funny Girl match any of these reference prints. That didn’t stop it looking fabulous when it premiered in LA.

What about restoration that adds footage to an existing version of a movie? My previous blog entry mentioned an example, the wild and crazy Nerven (1919), to be issued on DVD by the Munich Film Museum. Stefan Drössler, Munich’s curator, has done a remarkable job of incorporating new footage into the longest version of Nerven to date. (The new material includes “living intertitles,” in which actors drape themselves around gigantic letters.) But Nerven remains incomplete, lacking about a third of its original material.

What about restoration that adds footage to an existing version of a movie? My previous blog entry mentioned an example, the wild and crazy Nerven (1919), to be issued on DVD by the Munich Film Museum. Stefan Drössler, Munich’s curator, has done a remarkable job of incorporating new footage into the longest version of Nerven to date. (The new material includes “living intertitles,” in which actors drape themselves around gigantic letters.) But Nerven remains incomplete, lacking about a third of its original material.

Moreover, it’s possible to “over-restore” a film. That is, by adding footage culled from many versions, the restorer may be creating an expanded version that nobody actually saw.

Original version? What does that mean? Paolo Cherchi Usai has reflected on this at length. (4) Is the original what the film was like on initial release? This is tricky nowadays for new titles, because as Grover pointed out, most films are “initially released” in several versions. Since Hollywood filmmaking began, different versions have been made for the domestic and the overseas markets, and often the overseas versions are longer. Sometimes a film opens locally or at a film festival and then is modified for release. Major films by Hou Hsiao-hsien and Wong Kar-wai have played Cannes in versions longer than circulated later.

Now suppose that the film was modified by producers or censors for its initial release somewhere. If you can determine the filmmaker’s wishes, should you restore the film to what she or he wanted it to be? That flouts the historical principle of getting back to what people actually saw. Consider the shape-shifting Blade Runner. Only now, twenty-five years after its release, has the U. S. theatrical version appeared on video.

Or what do we do when a filmmaker, after the release, decides that the film needs to be changed? Late in life, Henry James felt the urge to rewrite many of his novels, and the revised versions reflect his mature sense of what he wanted his oeuvre to be. Why can’t a filmmaker decide to recast an older film? Such was the case with Apocalypse Now Redux and Ashes of Time Redux. Since the later version represents the artist’s latest viewpoint, should that be the authoritative version?

Grover encountered a variant of this problem when he invited one cinematographer to help restore a film. The cinematographer’s own aesthetic and approach to his work had evolved over the years, so he started to tweak things in a way that was taking the look of the film to a level much different than the original achievement. Grover had to steer him back to respecting the film’s original look.

On the brighter side: Grover brought in master cinematographer Jack Cardiff to advise on the restoration of A Matter of Life and Death. Cardiff said that one scene needed a “more lemony” cast. Grover tried, but each time Cardiff said it wasn’t right. Finally, Grover confessed that he just couldn’t get that lemony look. Cardiff nodded. “Neither could I.”

Grover offers this nugget of wisdom: It is almost impossible to get an older film to look the way it does when it was originally released. The color will never look as it did, nor will sound sound the way it did. Film stocks have changed, printing processes have changed, technology in general has changed. Every version is an approximation, though some approximations may be better than others. Take consolation in the fact that even when the movie was in circulation, it may have already existed in multiple versions.

What do consumers want?

All archivists explain that compromises enter into the preservation process down the line. One of the revelations of Grover Crisp’s visit was the awareness of just how many of these compromises come into play, and how some of them are tied to what DVD buyers expect.