Archive for the 'Film technique: Sound' Category

A glimpse into the Pixar kitchen

DB here:

On some of Bill Kinder‘s business cards, the I in PIXAR is represented by Buzz Lightyear, the blustery, not-too-swift astronaut of Toy Story. It’s a typical gesture of self-deprecation from the studio that showed that computer animation didn’t have to be just plastic surfaces and mechanical expressions. Pixar is cool, geeky, and warm all at the same time. Its films are both smart and soulful, made by movie fans for movie fans, and for everybody else. Like the best of the Hollywood tradition, Pixar movies have the common touch and still offer the most refined pleasures.

Kristin and I have already written admiringly about Pixar on this site (here, here, and here). It’s quite likely that this studio is making the most consistently excellent films in America today. So we were delighted when our colleague Lea Jacobs arranged for Bill to come to the University of Wisconsin—Madison last fall. He toured our new Hamel 3-D media facility, met with faculty and students, and gave a talk, “Editing Digital Pictures.” Bill is Director of Editorial and Post-Production, a position that gives him an encompassing view of the Pixar process as he champions the efforts of the editors and their teams as key creative contributors.

Kristin and I have already written admiringly about Pixar on this site (here, here, and here). It’s quite likely that this studio is making the most consistently excellent films in America today. So we were delighted when our colleague Lea Jacobs arranged for Bill to come to the University of Wisconsin—Madison last fall. He toured our new Hamel 3-D media facility, met with faculty and students, and gave a talk, “Editing Digital Pictures.” Bill is Director of Editorial and Post-Production, a position that gives him an encompassing view of the Pixar process as he champions the efforts of the editors and their teams as key creative contributors.

A graduate of Brown, where he studied with our old friend Mary Ann Doane, Bill is like Pixar movies—intellectual, good-natured, energized, and adept at connecting with people. He started his career in news-gathering and TV editing before moving to work at Francis Ford Coppola’s American Zoetrope, in the days of Jack (1996) and the uncompleted Pinocchio project. He joined Pixar in 1996, while they were finishing Toy Story. When the success of A Bug’s Life enabled Pixar to move to a purpose-built facility in Emeryville, Bill went along.

Whittling vs. building

I’ve always been uncertain about what an editor does in the animation process. Since every shot is planned and executed in detail, what can be left for an editor to do? Bill started from that question. No, editing digital animation isn’t just a matter of cutting off the slates and splicing perfectly finished shots together.

As in live-action filming, the animation editor is working with dozens of alternate versions of every shot. The reason is that at Pixar, there are roughly five phases of production: storyboarding, layout, animation, lighting, and effects/ rendering. Each one generates footage that has to be cut together.

The static storyboards, for instance, present poses, expressions, and movements against a blank background. They are assembled in digital files that can be played back as if they were a movie. In order to plan the next phase, the resulting “footage” has to be edited, and choices are made at every cut. And each scene is storyboarded at least five different ways, with many variations of action and timing. A single film uses up to 80,000 boards!

At the next phase, layout, the scene’s overall action is planned. Layout artists develop the staging of each shot, testing different backgrounds and camera angles with the editors. Again, the alternatives have to be assembled and cut in various combinations.

Whittling versus building, Bill called it. The live-action editor gets a mass of footage that has to be triaged, but the animation editor is building and tuning the film from the start. Editing operates at each phase, from storyboarding to final rendering. This “almost overwhelming iteration,” as Bill called it, demands that the editorial department hold all the alternatives in its collective mind at once. Add to this the fact that Pixar can take up to five years to produce a film, maintaining several editorial teams to cover projects at different degrees of completion. When you realize that all this brainpower and bookkeeping are necessary for even the simplest shot, you appreciate the felicities of the finished product even more. These people make it all look easy.

Continuity and the viewer’s eye

Bill explained that digital animation occasionally requires something like live-action coverage. (1) Action sequences with fast cutting need to be spatially clear, and “chase scenes can be hard to board.” So sometimes the layout artists create master shots and closer shots from different angles that the editor will pick out and assemble, live-action fashion.

Like live-action editors, Pixar editors have to keep an eye on continuity of the objects in the frame. Because each shot is reworked across many phases, items of the set, lighting, color, atmosphere, effects and rendering have to be maintained, on many layers or levels of the program. (I gather it’s like the layers in PhotoShop.) Sometimes a layer, whether a prop, character, or set element, fails to “turn on” and so a discontinuity can crop up. A finished Pixar film typically has 1500 shots or more, so there’s a lot to keep track of.

In another carryover from live-action features, Pixar plots are conceived and executed in three discrete acts. It’s not only a storytelling strategy but a convenience in production. Rather than waiting until the entire film is done to examine the results of the different phases, the filmmakers can finish one act ahead of the others in order to troubleshoot the rest.

I’ve studied how filmmakers compose the image in order to shift our attention (2), so I was happy to hear that this process is of concern to the Pixar team. “Guiding the viewer’s eye,” Bill called it. He explained that in looking at storyboards and animated sequences, his colleagues sometimes use laser pointers to track the main areas of interest within shots and across cuts, especially when characters’ eyelines are involved. Nice to see that sometimes academic analysis mirrors the practical decisions of filmmakers.

The auteurs of Pixar

What makes Pixar films so fine? Bill supplied one answer: It’s a director-driven studio. As opposed to filmmaking-by-committee, with producers hiring a director to turn a property into a picture, the strategy is to let a director generate an original story and carry it through to fruition (aided by all-around geniuses like the late Joe Ranft). Within the Pixar look, John Lasseter’s Toy Story 2 and Cars are subtly different from Brad Bird’s The Incredibles and Ratatouille or Andrew Stanton’s Finding Nemo and upcoming Wall.E.

Bill covered many other fascinating topics, including the importance of sound (“the animated film’s nervous system”). But I’ll end with some pull-quotes from Bill’s talk.

*Francis Ford Coppola: “No film is ever as good as its dailies or as bad as its first assembly.”

*Gary Rydstrom: “Film sound is the side door to people’s brains.”

*Bill himself: “Editing is just writing, but using different tools.”

We’re grateful to Bill for his visit and look forward to seeing him again. Goes to prove what we’ve said before: Popular American filmmaking harbors many of the most intelligent, sensitive, and generous people you’ll ever find.

(1) In live-action production, coverage involves shooting a master shot of a scene that shows the entire action. Then parts of the action are repeated and filmed in closer views. This allows the editor several options for cutting the scene together.

(2) I talk about this in Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style and throughout Figures Traced in Light. See also Film Art, pp. 140-153, and this blog here and here.

PS: Another glimpse into the kitchen: Bill Desowitz reports on Wall*E at Animation World. Now Pixar is trying to emulate the look of 70mm. And there’s footage from Hello, Dolly! in there? All the signs point to another nutty, dazzling achievement.

All singing! All dancing! All teaching!

Kristin here—

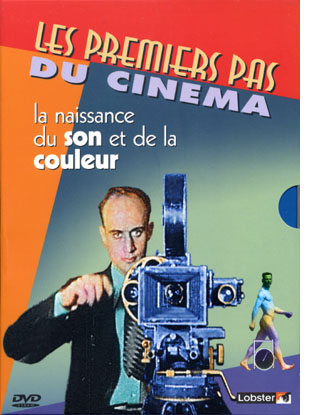

David and I are currently revising our second textbook, Film History: An Introduction, for a third edition due out next year. As part of the research, I’ve been watching two recent DVDs on the early history of sound and color. Both offer valuable resources for those teaching introductory film-history classes, as well as more specialized ones.

Twenty-five years ago, when I last taught a survey history class, the resources for teaching about the innovation of sound were discouragingly limited. The early Vitaphone shorts were as yet unrestored, with most of their accompanying discs damaged or lost. The most famous early sound films were mainly available in mediocre 16mm prints. Showing an “early” sound film often meant a René Clair classic from the early 1930s—a time when the transition to sound was well along, if not over. Le Million or Á nous la liberté demonstrated the artistry that an imaginative director could bring to the early sound cinema, but it wouldn’t give much idea of the struggle inventors and filmmakers went through to create the complex technology.

The same was true for pre-1935 color. There was no way to adequately survey the range of processes and experiments, from early hand painting and stenciling to two-strip Technicolor. The poor 16mm prints of early films often gave no real indication of what they had looked and sounded like when they were made.

Since then archivists have been intensively discovering and preserving films, and in some cases these have been released on DVD. Often these discs are simply collections of films, but documentaries incorporating short films and clips are becoming more common, especially since they make attractive television programs.

Discovering Cinema (Flicker Alley)/Les Premiere pas du cinéma (Lobster & histoire)

A two-DVD survey from the very active Lobster archive in Paris devotes a disc each to sound (2003) and color (2004). Lobster is a private archive started in 1985 by two film enthusiasts, Serge Bromberg and Eric Lange. (The website offers a choice of French or English text.) It began as an effort to discover lost films. Building on its success, Lobster has grown into a major resources for restoring films—both their own discoveries and commissions from other archives and from film companies.

David and I bought this set when it came out. The French boxed set offers a choice of French- or English-language versions. (It’s not region-coded, but it is PAL, which means it won’t play on NTSC players, the standard in the U.S. and some other countries.) The French version isn’t on the Amazon.fr site, but fnac is offering it.

In September, 2007, the American version was released by Flicker Alley. This is another private archive, founded in 2002, also by an enthusiast, Jeffery Masino. The company hasn’t put out many titles yet, but the DVDs available so far are impressive. Flicker Alley collaborates with Turner on restorations, and presumably its catalogue will grow.

Each Lobster documentary is about 52 minutes long, and the supplements include a number of complete films.

The disc devoted to color is subtitled “Un rêve en couleur” and in English the slightly more poetic “Movies Dream in Color.” It’s organized by the three types of cinematic color: Colors and Tints (that is, black and white film painted or dyed), Additive Synthesis (using filters on the projector lens to add color to black-white film), and Subtractive Synthesis (recording separate colors on separate strips of film and combining them in printing).

The disc devoted to color is subtitled “Un rêve en couleur” and in English the slightly more poetic “Movies Dream in Color.” It’s organized by the three types of cinematic color: Colors and Tints (that is, black and white film painted or dyed), Additive Synthesis (using filters on the projector lens to add color to black-white film), and Subtractive Synthesis (recording separate colors on separate strips of film and combining them in printing).

There’s a quick run-through on color in pre-cinema devices: slides, peep shows, and topical toys. The next section gives a splendid demonstration of how stencils were used to hand-color films (such as the unidentified example above), as well as some briefer coverage of tinting and toning.

Moving to additive color systems, the film deals with Friese-Green’s early experiments, Charles Urban’s Kinemacolor, with its brief commercial success, Gaumont’s technically sophisticated Chronochrome, and various lenticular systems. Given that these attempts require special projection, the recreated examples given here are one of the few ways that we can see such films today. All of them proved dead ends, however, so they are of more interest for their technical ingenuity than for their ultimate impact.

The final part of the film turns to Technicolor, founded in 1915. The firm quickly turned away from its early additive experiments and settled on a subtractive system using two strips of film and later, in the 1930s, three strips—resulting in the vibrant hues that many people still think of as the acme of filmic color. “Movies Dream in Color” gives a brief but useful run-down of Technicolor’s progress, through its early two-strip successes like The Black Pirate through the exclusive contract with Disney in the 1932-36 period, and its triumph thereafter as the main color system of Hollywood. There is also some coverage of the two brands that combined all colors on a single negative, Kodachrome and Agfacolor, but the coverage essentially ends in 1939, before either had become widespread.

Incidentally, an in-depth study of Technicolor has recently been published: Scott Higgins’ Harnessing the Rainbow: Color Design in the 1930s.

The filmmakers weave together interviews with a number of prominent archivists, including Paolo Cherchi Usai (co-founder of “Le Giornate del Cinema Muto” festival and now director of Australia’s national archive) and Gian Luca Farinelli (director of the Cineteca di Bologna).

“Learning to Talk” (in the French set “Á la recherche du son”) uses the same group of experts and a somewhat similar three-part organization: “artistic sound” (that is, live sound during the projection of silent films), sound on disc, and sound on film.

The segment on live sound is excellent. It again starts with pre-cinema music and effects for magic-lantern shows and progresses to Reynaud’s hand-drawn Pantomimes lumineuses, with their specially written music. One highlight is documentary footage of a man demonstrating the use of an elaborate sound-effects box, with its brushes, cans of pebbles, and other crank-operated devices that simulated such actions as trains moving and crockery being smashed.

The sections devoted to sound-on-disc and sound-on-film are less well set forth, since the filmmakers try to cover many pioneers in France, the U.S., Germany, and Denmark. Again, several of the devices covered were novelties that led nowhere or that failed for lack of amplification, the use of non-standard film widths, and other reasons.

Once the story reaches the lengthy invention process of the two main American systems, Warner Bros.’ Vitaphone (using discs) and Fox’s Movietone (sound-on-film), it proceeds more clearly. “Learning to Talk” includes some of the Case and Sponable demo films, a Movietone News interview with Mussolini, and a clip from Don Juan. Presumably because of rights problems, no footage from The Jazz Singer is shown.

The bottom line is that the color disc strikes me as the more useful for teachers. The sound one gives good coverage, but again many of the systems discussed are not historically significant to anyone but specialists. For a history of that deals largely with the American innovation of sound, one can now turn to a superb recent DVD.

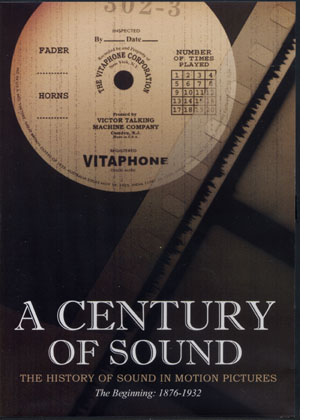

A Century of Sound: The History of Sound in Motion Pictures: The Beginning: 1876-1932 (UCLA Film & Television Archive and the Rick Chace Foundation).

This disc originated in a lecture on early sound by Robert Gitt, who has long been the preservation officer for UCLA’s film archive. Gitt has supervised on the restoration of many important films. In 1991 his team launched the Vitaphone Project. Vitaphone, Warner Bros.’s commercially successful sound system of the 1926-31 period, used phonograph records rather than optical tracks on the film strip. Over the decades many of those discs were damaged or separated from the original reels, and the Vitaphone shorts sat in their cans, reduced to silence.

Gitt and company set about finding as many discs for the surviving Vitaphone films as they could. Over the years they were amazingly successful in tracking them down and rejoining sound and image in a sound-on-film format that can be shown on modern projectors. You can trace the progress of the project since its beginning through its online newsletter, which currently runs from fall, 1991 to winter, 2007/08.

Colleagues urged Gitt to turn his lecture on sound, copiously illustrated with clips, into a DVD. He took the opportunity to expand the talk and to incorporate more and lengthier clips. Most documentaries on film history include only brief clips from any scene. Gitt has wisely opted to include whole scenes, and he has had access to high-quality archival prints of the key early sound films. He also offers early tests made by the companies responsible for innovating sound, as well as documentary shorts they used in selling their processes to industry executives. Rather than writing a script for someone else to read, Gitt appears as presenter and narrator. He humorously admits to the dullness of some of the technical shorts and acknowledges the occasionally silly or racist content of some of the films. At the same time, though, he makes clear what is significant about the examples he presents, and they all become more intriguing than they would if seen individually, out of context.

Colleagues urged Gitt to turn his lecture on sound, copiously illustrated with clips, into a DVD. He took the opportunity to expand the talk and to incorporate more and lengthier clips. Most documentaries on film history include only brief clips from any scene. Gitt has wisely opted to include whole scenes, and he has had access to high-quality archival prints of the key early sound films. He also offers early tests made by the companies responsible for innovating sound, as well as documentary shorts they used in selling their processes to industry executives. Rather than writing a script for someone else to read, Gitt appears as presenter and narrator. He humorously admits to the dullness of some of the technical shorts and acknowledges the occasionally silly or racist content of some of the films. At the same time, though, he makes clear what is significant about the examples he presents, and they all become more intriguing than they would if seen individually, out of context.

The result offers an extraordinary array of clips that teachers could draw upon even if they don’t have time to show the entire lengthy documentary. For Vitaphone there are some of the early shorts, the entire duel scene from Don Juan, extended excerpts from The Better ‘Ole, Old San Francisco, Lights of New York, and others. For Fox Movietone there are scenes from 7th Heaven and Sunrise, as well as George Bernard Shaw’s charming appearance in an issue of Movietone News.

Despite some lively moments, many of the early sound films are slow and clunky, due to the limitations of the available equipment. Gitt balances them by ending with some familiar examples of the imaginative early use of the new technique: the “Paris, Please Stay the Same” number from Lubitsch’s The Love Parade, a generous excerpt from Mamoulian’s Applause, and a portion of I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (which, be warned, gives away the ending). Teachers whose schedules don’t permit them to devote precious screening time to an early sound feature can give their students a reasonably good sense of the transitional period with such clips.

We’ve all heard the stories about how certain actors’ careers were destroyed by sound, but for the teacher there’s again the problem of how to demonstrate this to classes. Gitt has filled this need as well. Among the bonuses (which are few because so much is included in the film), there is one on the fates of actors. For each Gitt supplies both a clip of the actor in a silent film and in a sound one. The actors whose careers took a nose dive in sound films are represented by Rod La Roque, Norma Talmadge, John Gilbert, and Charles Farrell. Those who successfully made the transition are Ronald Colman, Joan Crawford, William Powell, and Laurel and Hardy. Gitt makes plausible cases why the public responded to each actor as it did.

As the disc’s title implies, it is intended to be part of a series of three documentaries that will cover the entire century. If Gitt continues to get access to the sort of material he presents here, the result should be an impressive overview of the subject and a boon to educators. If in the 1970s and 1980s we had dreamt up our ideal documentary subject for teaching early sound, it would have looked a lot like A Century of Sound—except we couldn’t have imagined all the material that existed in the vaults, waiting to be found and restored.

A Century of Sound is not available commercially. Educators and researchers can request a free copy (with a $10 shipping charge) by downloading a pdf form here.

The Jazz Singer (Warner Bros.)

Released this past October, this three-disc deluxe set marks the first time that The Jazz Singer has been on DVD. (Legally, that is; there was apparently a Chinese bootleg.) It also includes numerous supplements, some of which might be useful for teaching the introduction of sound.

The first disc contains the restored print of The Jazz Singer, a complete version of Al Jolson’s Vitaphone short, A Plantation Act, and some other shorts. One of these is the classic Tex Avery cartoon, I Love to Singa, inspired by The Jazz Singer and starring “Owl Jolson.”

An 85-minute documentary, The Dawn of Sound: How Movies Learned to Talk is the main item on the second disc. It was made by Turner Entertainment and bears a copyright date of 2007. Like so many TV shows, it doesn’t trust enough in the inherent interest of its topic. Rather than explaining the sound systems clearly by type, the writers have opted to try and stress the four Warner brothers as interesting personalities (not very successfully) and the intense competition among the sound systems in the late 1920s. The opening third cuts together too many brief, unidentified film clips and talking-heads comments, which doesn’t make for a coherent introduction to the topic. The production of the Vitaphone shorts is not well explained, though the film does point out that the shorts were more influential than Don Juan in making the new process appeal to audiences. There are excerpts from the main early Warners sound films, as well as a section on actors who succeeded or failed in talkies.

Another item on this second disc is the entire surviving footage—two scenes—from Gold Diggers of Broadway, a two-strip Technicolor musical from 1929. It’s rather an arbitrary inclusion, but as it’s not likely to come out on DVD in any other context, we should be grateful to have it. The scenes are pretty dreadful, apart from the spectacularly cubistic melange of Parisian landmarks in the set.

Another item on this second disc is the entire surviving footage—two scenes—from Gold Diggers of Broadway, a two-strip Technicolor musical from 1929. It’s rather an arbitrary inclusion, but as it’s not likely to come out on DVD in any other context, we should be grateful to have it. The scenes are pretty dreadful, apart from the spectacularly cubistic melange of Parisian landmarks in the set.

The rest of the disc consists mainly of some older documentaries on early sound made by Warner Bros. One, The Voice from the Screen (1926) was intended as a demonstration of Vitaphone for technicians. The presenter is not, to say the least, charismatic, and it’s obvious why Discovering Cinema and A Century of Sound use only excerpts. Nice to have it complete, but students wouldn’t sit still for the whole thing. The Voice that Thrilled the World was directed by Jean Negulescu in 1943, on the occasion of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences adding a best-sound Oscar—the first of which happened to go to Warners’ Yankee Doodle Dandy. This short seems to be the source for the staged footage of early sound breakthroughs that show up, unidentified, in The Dawn of Sound and the other documentaries. Not surprisingly, The Voice that Thrilled the World primarily hypes the Vitaphone process.

“Okay for Sound” (1946) celebrated the twentieth anniversary of Don Juan’s premiere, and it recycles a lot of material from the 1943 short. Like The Voice that Thrilled the World, it was a theatrical short, intended as much to promote current Warners’ films as to celebrate the studio’s past triumphs. The film handily includes an extended clip of Jolson singing the saccharine “Sonny Boy” number in The Singing Fool (1928).

(A companion book with a slightly different title, “Okay for Sound!” was published in 1946. It’s a picture history of sound. The photos are not well produced, and many are just publicity stills from films. It does contain quite a few photos of sound equipment. It turns up with surprising frequency in used-book stores. The phrase, by the way, is what recordists would call out to indicate to directors when the sound was operating and the action could start–their equivalent of the camera operators’ “Speed!”)

When the Talkies Were Young (1955) is an odd, low-budget documentary that consists of fairly extended clips from some early Warners’ talkies: Sinners’ Holiday (1930), 20,000 Years in Sing Sing (1932), Night Nurse (1931), Five Star Final (1931), and Svengali (1931). These aren’t bad, though unfortunately the narrator occasionally interjects comments during the action.

The third disc contains over three and a half hours of restored Vitaphone shorts, a treasure trove for teachers who want to show some examples of these. The first one, Behind the Lines (1926), is the example we use in our box on “Early Sound Technology and the Classical Style” in Chapter 9 of Film History: An Introduction (see Figures 9.4 and 9.5, p. 197 in the second edition).

If I had to make a choice of just one of these three DVD releases in looking for clips for a unit on early sound, I would favor A Century of Sound as having the best organized presentation and the most useful set of excerpts. The “Learning to Talk” disc could be useful as a briefer, self-contained teaching tool. The Jazz Singer package is a bit of a hodgepodge, but educators who want to deal with early sound in depth could pluck out some very useful additional material from it.

A May 12, 1925 Case test with Gus Visser and his duck singing a duet of “Ma, He’s Making Eyes at Me.” (Added to the National Film Registry in 2002 and included in both Learning to Talk and A Century of Sound.)

What does a Water Horse sound like?

Kristin here—

Sentimental Journey

Regular readers of this blog will recall that David and I spent this past May in New Zealand, as Hood Fellows at the University of Auckland.

I did not have much of an excuse to go back to Wellington during our sojourn, but I decided to go for a few days anyway. It’s my favorite city in New Zealand, partly because I have so many memories of exciting events there and partly because it’s an attractive place in itself. Once my lecturing duties in Auckland were done, I took a train, the Overlander, that runs much of the length of the North Island. It’s a 12-hour ride through some very spectacular scenery (including Mount Doom, aka Mount Ngaurhoe; check it out on Google Earth at 39˚ 9’ 25.58” S 175˚ 37’ 57.89” E) and dizzying viaducts over deep gorges.

I was in Wellington for three days, staying where I had stayed on my previous three visits—the Victoria Court Motor Lodge. I originally chose it on the recommendation of Melissa Booth, a publicist on The Lord of the Rings, who had kindly acted as my point person for the first trip. During this year’s stay I had meals with a couple of people I had interviewed who also became friends. Judy Alley was the merchandising coordinator for Rings and King Kong and now works in publicity at Weta Digital. Given my interest in the franchise aspects of Rings, interviews with Judy had explained a lot about the nuts and bolts of coordinating with licensees. Erica Challis, co-founder of TheOneRing.net, had moved to Wellington since I interviewed her in Auckland. We snatched a quick dinner before she went to play French horn in a rehearsal for Swan Lake.

I also finally got to visit Te Papa, the national museum. It’s one of the main destinations for visitors, yet I had never gone through it. I felt it was rude to do that with my cell phone turned on. Sort of like keeping it on in a movie theater. But when I was trying to juggle appointments to interview people, I didn’t dare turn it off. It was worth missing some tourist opportunities, though, since every now and then that phone did ring, sometimes with good news.

For instance, on my first visit in 2003, a week after I had requested permission to watch Peter Jackson supervising the sound mixing on The Return of the King, I got a call at 7:45 pm on a Friday night telling me I could do so the next day. (If you hope to be a director’s or producer’s assistant, be prepared for long hours.) When I showed up, it turned out he and the sound editors were working on the Shelob sequence. Sometimes it pays to sit by the phone.

Park Road Post

During my Wellington visit, I learned from Barrie Osborne that coincidentally a film he is producing was in the sound-mixing phase, and I was invited to come and sit in for a day. Barrie is an American, but he produced The Matrix in Sydney and spent a long time in New Zealand producing all three parts of Rings. Like so many people who came from abroad to work on the trilogy, Barrie fell in love with the place. Now he lives there part-time and works on a range of Australasian projects, including executive producing The World’s Fastest Indian, a Kiwi film, and Little Fish, an Australian drama. (I saw these back-to-back at the American Film Market in 2005, going from the upbeat crowd-pleaser Indian to Fish, a drama about heroin addicts with great performances from Cate Blanchett and Hugo Weaving—both worth a look if you missed them on their brief American releases.) He also championed The Frodo Franchise from the start, and the book probably wouldn’t exist now without his help.

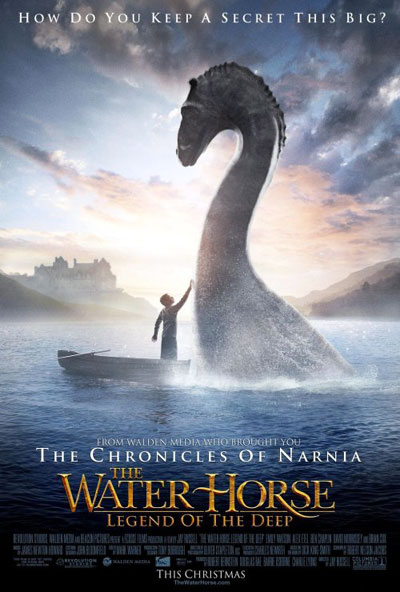

The film he was finishing up was The Water Horse: Legend of the Deep, an adaptation of a popular children’s fantasy novel by Dick King-Smith. It will be released on Christmas Day and has a PG rating.

The mixing was taking place in Studio 2 of Park Road Post, the same place where I had watched Peter supervising the Shelob scene.

Park Road Post (formerly The Film Unit) is a state-of-the-art post-production facility that started moving into its new building gradually, starting in the summer of 2003. At that point only the sound studios and the offices along the corridor outside them were finished. A segment about 19 minutes into the “Soundscapes of Middle-earth” supplement on the extended-version DVD of Return shows the facility as it was then.

My first interview with Barrie was in one of those offices, with considerable construction noise right outside the window. Fortunately my microphone was directional enough that it didn’t overwhelm our conversation. (That office is seen in the “End of All Things” supplement on the same disk.)

By my third visit to Park Road Post, in late 2004, the editing rooms and the huge, beautiful front lobby had been finished, the garden in the center courtyard was being installed, and the processing laboratories were being built. Now the whole thing is finished, with a strange juxtaposition of beautiful modern design in the front and big windowless concrete buildings at the rear.

Park Road itself is a street in the Wellington suburb of Miramar, lined in one section by small houses and then by rows of undistinguished warehouses and small industrial buildings. Next door is the large California Garden Centre, a round, orange building. Gazebos and garden swings are displayed right up against the walls of the sound studios.

Walking from this mundane environment into Park Road Post is a disorienting experience. Suddenly one is in a modern building with a design heavily influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright. Natural wood, fireplaces, stained glass windows, cushy leather sofas. It’s a building that one doesn’t want to leave. It has almost an other-worldly quality, which is perhaps not surprising given that it was designed by Dan Hennah, the art director of Rings and Kong.

Making the place as attractive as possible was part of the brief that Peter and partner Fran Walsh handed Dan. As he told me, “It was partly about getting it technically correct and partly about creating an environment that, while being technically correct, was still human and homely and all those things—the comfort zone. So that you actually felt like getting up and going in there in the morning—rather than thinking, ‘Oh, God, I’ve got to go into that bloody hole again!’”

By now the ironic story has become famous. A 17-year-old Peter Jackson, aspiring to be a filmmaker, left school and applied for a job at the Film Unit back in the late 1980s. He was turned down, so he worked as a photo-engraver at a newspaper instead. Eventually he got enough backing to quit and finish Bad Taste (1987), his long-gestating first feature. A little over ten years later he bought the Film Unit, then housed in what he described to me as “a sort of ‘Soviet bloc’ feeling place.” During my first visit in 2003, the editing and lab facilities were still there, in a dreary-looking industrial complex out in the distant suburb of Lower Hutt.

Tracking The Water Horse

At the Water Horse sound mixing director Jay Russell was present, though he slipped out at intervals for meetings. As I was about to leave, he remarked that watching sound mixing is like watching paint dry. That’s what everyone says about mixing, but I find it fascinating.

Back in the late 1970s when David and I had the opportunity to spend about half an hour watching the great Walter Murch working on a scene for Apocalypse Now, it was a slow process. Mixing was done on film, so every repetition involved a pause for rewinding, threading the projector, and so on. Now, with high quality digital images being projected on the studio screen, mixers can almost instantly go back to the beginning of a segment by sliding a control handle or move to a different scene by typing in a file number. As a result, there may be many repetitions of the same series of shots, but there’s not that much down time.

The repetition isn’t boring, either, since you can listen for the tiny changes that the mixers make between projections of the scene. (See David’s account of his experiences watching James Mangold’s team mixing sound for 3:10 to Yuma.) There may also be pauses, but usually they’re for discussions among the sound team members. Some of this was just too technical for me to grasp, but what I could follow was fascinating.

That particular day came fairly late in the overall process. Jay was there because the work on the sound was close to finished. The team was concentrating on the final mix of reel 1. It was quite a contrast to the footage I had seen being mixed for Return. In that case a lot of unrendered effects shots were still in the edit, and many scenes hadn’t been locked down yet. Shots of Gollum often just showed him as a figure made up of silvery bands against a black background, and in some cases there was only a title describing the nature of the scene—a close-up of Treebeard looking left, for example. (Again, the DVD bonus chapter “The Soundscapes of Middle-earth” shows some vivid examples of the process.) In the case of The Water Horse, all the footage was finished, and the editing had been completed.

A lot of what goes on at this late stage is tweaking individual tracks. Even though there’s a full mix by this point, the team frequently take out all the tracks except one, so that a bustling city street scene may have densely layered traffic sounds and a musical track during one run-through and only a couple of characters’ footsteps in the next.

As with many films, some musical instruments were on separate tracks. Jay could ask for a drum beat to be turned up to provide a more distinct rhythm to a scene or for certain instruments to be favored so as to enhance the atmosphere of the Scottish setting.

Some of the people present had worked on Rings as well, so I knew a few of them already. It was great to see Rose Dority, post-production supervisor, again. Since my book isn’t really a making-of study, I hadn’t interviewed her, but she had been very hospitable. I also recognized Dave Whitehead, the supervising sound editor, who seems to have worked on half the films made in New Zealand over the past 13 years.

At lunch I got talking with Dave, and he told an anecdote about how some of the war chants of the Easterling attackers during the Battle of the Pelennor in The Return of the King were done. The sound department couldn’t use English, of course, and no texts had been provided. One tactic the recorders and mixers resorted to was spelling the names of their children, friends, and colleagues backwards. In fact I had been present the day those chants were being synchronized and remembered vividly how at the time Dave had explained that “Revilo!”—which sounded very aggressive when shouted in unison by male voices—was based on his son’s name, Oliver. Rose got into the mix as well, as “Ésor!” In the final mix, those chants are not really distinguishable as individual words, being parts of a dense mix of battlefield noises. Still, it was fun knowing that they were there.

The Water Horse mixing went on until mid-afternoon, when a group of people came into the studio for a run-through of the first reel. By that point I was pretty familiar with all the footage and could concentrate on the soundtrack rather than figuring out the plot from the scenes shown out of order up to that point.

Once the screening ended, Barrie asked various people if they had noticed anything that might need changing. Rather to my surprise he included me. Fortunately, rather than sitting there saying, “Ummmm … no,” I did have a suggestion about one sound that was slightly too loud and distracting during a suspenseful moment. That got duly noted down with the other comments and fixed during the final changes. That was an unexpected treat!

The Water Horse is a story of a Scottish boy who finds a strange egg that hatches into a little creature that will grow into the Loch Ness Monster. In the reel I saw, the landscapes were beautiful, a smooth mixture of footage shot in Scotland and in New Zealand. With both Weta Workshop and Weta Digital providing special effects, it naturally has high production values–including a carefully mixed soundtrack. It’s a children’s film, but from what I saw of it, parents will enjoy it as well. (The favorable Variety review is here.)

It’s a production by Walden, which specializes in family-friendly projects. The company seems to like New Zealand, given that much of the first Chronicles of Narnia film and part of the second were shot there.

Cronenberg’s violent reversals

Eastern Promises

Kristin here–

A Pair of Films

I haven’t read nearly all the review of Eastern Promises, of course. Sampling eight or so, I have noticed that quite a few critics briefly note a similarity between David Cronenberg’s new film and his previous one, A History of Violence. There are the obvious links. Viggo Mortensen plays the lead in both, a man with a secret—or a bunch of them. Both involve crime syndicates run by families. Both contain scenes of graphic, brutal violence.

Reviewer John Beifuss calls Eastern Promises “A sort of companion piece to Cronenberg’s previous feature, ‘A History of Violence’ (2005), adding that, “‘Eastern Promises’ opens in a modest barber shop that recalls the small-town diner that was the site of unexpected brutality in ‘Violence.’” Beth Accomando comments, “In some ways, Nikolai has much in common with Mortensen’s character in A History of Violence, who hides one persona beneath another.”

J. Hoberman goes a little further in defining the parallels. “Eastern Promises is very much a companion to A History of Violence. Both are crime thrillers that allow Viggo Mortensen to play a morally ambiguous and severely divided, if not schizoid, action-hero savior; both are commissioned works that permit hired-gun Cronenberg to make a genre film that is actually something else.” (For more reviews, see Rotten Tomatoes’ page on the film.)

It would be hard to discuss the similarities between the films without giving away too much of the plot, and clearly that’s why reviewers have said so little on the subject. So I should make it very clear that I’m writing a brief analysis here, not a review. There will be major spoilers for both films. I don’t always mind spoilers for films I’m going to see, but A History of Violence and especially Eastern Promises really depend on the withholding of information. I’d urge you to see both films before reading the rest of this entry.

What I’m primarily interested in here is the extent to which the second film manages to be a mirror-image reversal of the first. It’s a remarkable formal accomplishment, I think, to have a director make two consecutive films with different plots, characters, settings, and narrational strategies that are such exact reversals of each other. Eastern Promises isn’t a sequel, yet it forms a pair with A History of Violence. It’s like those trilogies that are united by theme rather than by being parts of the same story (e.g., Ingmar Bergman’s Through a Glass Darkly, Winter Light, and The Silence, or Phillip Glass’s three biographical operas, Einstein on the Beach, Satyagraha, and Akhnaton). Whether or not this pairing was intended by Cronenberg, one could easily imagine him working again in the same vein.

Basically you’ve got a central character with two sides to him, the criminal and the good. In A History of Violence, the protagonist is leading an ordinary domestic life that is threatened by a revelation of his criminal past. He barely manages to suppress the threat to his family that results when his former associates re-establish contact with him, and he can suppress it only by using more violence and revealing to his family what he had been

In Eastern Promises, the hero does the opposite. He is voluntarily leading a criminal life undercover in order to fight the Russian mafia gang he works for. By meeting and falling in love with Anna, he is given a chance to lead a normal life with her but manages to suppress his longing for that in order to continue his struggle. (Even his boss in whatever crime-fighting organization he secretly works for offers him an out, saying that the Russian embassy has requested he be taken off the case. Nikolai insists on continuing his activities, since he now has had a promotion that will allow him to penetrate to the very heart of the criminal gang he has been fighting.)

There are contrasts and parallels that encourage a comparison of the two films. The modest diner that Tom Stall runs in A History of Violence could not be more unlike the  sumptuous Russian restaurant that is the front for Semyon’s vory v zakone activities. The much-lauded fight scene in the public baths in Eastern Promises is a more visceral version of a battle late in A History of Violence when Tom, about to be killed at his brother’s order, manages to kill all five of the men holding him captive. (At left, four down, one to go.)

sumptuous Russian restaurant that is the front for Semyon’s vory v zakone activities. The much-lauded fight scene in the public baths in Eastern Promises is a more visceral version of a battle late in A History of Violence when Tom, about to be killed at his brother’s order, manages to kill all five of the men holding him captive. (At left, four down, one to go.)

The black, forbidding car that Nikolai drives echoes that of the vengeful thug Fogarty in A History of Violence; both glide to ominous stops on the street outside the dwelling of their presumed victims. Each of the films ends on a close view of the protagonist seated at a table: Tom fearfully yet hopefully searching the faces of his family for signs of acceptance and Nikolai sitting in the Russian restaurant he now runs, thinking in sorrow of Tatiana and presumably of his missed life with Anna. Even the meal that Tom returns home to and the one Anna’s family are having at the end are similar: roast beef and vegetables.

Ultimately the contrasts in the two films are what makes the ending of Eastern Promises even more affecting than that of A History of Violence. Tom Stall has used deceit to walk away from his violent life and make a new and normal one. By the end the revelation of the deceit has damaged that normal life considerably, but there are indications that the damage will gradually, though not wholly, fade through re-established love and trust. Nikolai, on the other hand, has gone down the far more difficult road: walking away from a potentially normal life to continue to use deceit and violence to fight the vicious organization that preys upon normal people. (When Anna’s mother warns her away from her contact with the criminals, saying “This isn’t our world. We are ordinary people,” Stepan responds that Tatiana was an ordinary person, too.)

One thing that distinguishes the films is that we never learn whether Nikolai was already a real criminal earlier in his life, one whom the British authorities successfully recruited to help them run an underground operation against the vory v zakone in London. Were his tattoos really given him in Russian prisons, or are they an elaborate disguise created in England? We don’t know if Nikolai had a normal life before and gave it up to play out this ruse or if this undercover job is his redemption for past evils.

Tatiana’s Voice

One specific device intrigued me the first time I saw the film: the voice of Tatiana, the girl who dies early in the film giving birth. That voice is heard over at intervals, speaking passages from the diary that Anna finds in her purse and tries to get translated. What is the “source” of this voice? Against seeming logic, the voiceover becomes associated with people reading or translating the diary only fairly late in the film. The early instances occur over scenes where no one present could know the contents of the diary.

On my second viewing of the film, I took notes on the contexts in which the voice is heard, and I think this is a complete list:

First, as Anna initially opens the diary and finds the card for the restaurant; cut to her on bike heading for the restaurant.

Second, early the next evening as Anna rides her bike to the restaurant; the voice bridges the cut to Semyon drinking alone inside restaurant.

Third, during the scene of Nikolai having sex with the blonde prostitute.

Fourth, over Anna at hospital with baby Christina. Semyon comes in and says he has translated the diary—but doesn’t give the translation to her.

Fifth, shortly thereafter, Semyon leaves, and the voice resumes over a shot of Anna, upset by his implied threats. It bridges the cut to the dining room where the mother and Stepan are translating the diary. The voice of Tatiana dissolves into that of Stepan. This signals the point at which the family members finally become aware of the specific contents of the diary: that Semyon is the one who raped Tatiana and left her pregnant with Christina.

Sixth, a scene beginning with Nikolai in the restaurant alone, reading the diary. (Anna had given Nikolai the diary at the end of the previous scene, telling him to read it.) Semyon enters, gets the diary from him, and burns it.

Seventh, over a brief scene of Anna at home reading the translation of the diary. (This is immediately followed by a scene of Nikolai in his car watching Stepan go into a block of flats.) The implication is subtle, but in the most recent conversation between her and Nikolai, he has told her that she should raise Christina herself. Now perhaps she is searching the diary for evidence to justify such a decision.

Eighth, the final voiceover passage begins as Anna sits with Christina, whom she has adopted, in the garden; the voice bridges to the restaurant with Nikolai sitting alone, a bottle of vodka at his elbow. This is, I believe, the only repeated passage, being the same part as we hear in the first instance of voiceover. The passage ends, “That is why I left. To find a better life.”

This is two-edged. On the one hand, Nikolai does not have the option of leaving and finding the better life that he wishes he could have with Anna—the one we’ve just seen her leading with her family. On the other, he has the chance to save others from the fate that Tatiana suffered.

Only after the scene in which we see Nikolai reading the diary (the sixth occurrence of Tatiana’s voiceover) do we find out that he has been working against the gang—arranging for the blonde prostitute to be rescued by the police, spiriting Stepan away into hiding rather than murdering him. Yet it is not the diary’s contents that affects him and causes him to do such things. Reading the diary provides a plot point, giving him the vital clue that Semyon is Christina’s father, allowing him to tell the police how to test for DNA and convict Semyon of statutory rape.

The first four instances of the voiceover are not associated with anyone reading the diary. The last four are: Stepan translating it, Anna reading it, Nikolai reading it, and finally Nikolai apparently remembering it as he sits in place of Semyon in the restaurant. Seeing the film the first time, at the end I wondered if perhaps Tatiana’s voice becomes retrospectively linked to Nikolai, who sacrifices his own chance to happiness to continue battling the system of human trafficking that had victimized her.

Watching Eastern Promises again, I realized that the device is not that straightforward. Yet just as learning late in the film about Nikolai’s long undercover work against the vory v zakone shifts the implications of almost everything we have seen, so the resonance of the voiceover passages changes upon re-viewing. All the occurrences of it seem to lead up to the epilogue and to link our privileged access to Tatiana’s writings to our special knowledge of Nikolai’s role in so much of what has happened.

The voiceover motif has other functions. It keeps reminding us of the diary, which is crucial to the plot in several ways. It provides exposition about Tatiana’s life and about the methods used by the Russian mafia to lure girls and women into leaving their homes. Indeed, the device is typical of the narration, which remains quite objective and informative on the whole, moving between the two central characters in an even-handed fashion and even showing the other major characters when those two are not present. The voiceover becomes another means that the narration uses to inform us about the one character who disappears from the scene almost immediately.

Only at the end does the narration settle with one of the characters. We have seen Anna, finally happy in motherhood after having suffered a miscarriage shortly before the action of the plot began. The film ends with Nikolai, briefly lingering over his grim situation and allowing us to picture what his life will be like. That moment, I think, was where I came to associate Tatiana’s voiceover primarily with him.

Figuring backward

Some reviewers have compared Eastern Promises with A History of Violence primarily in qualitative terms. Is the second film inferior to the first? As good? Better?

They’re both very good. If more films these days were as good as either, we’d complain a lot less. Still, upon viewing each a second time in preparing to write this entry, I became convinced that Eastern Promises is even better than its predecessor. A History of Violence is a relatively simple film, and it remained much as I had remembered it. Revisiting Eastern Promises only a week after my first viewing, I saw far more in it.

The character of Kirill, Semyon’s son and apparent heir, is more complex. More importantly, Nikolai’s involvement in the affairs of the family’s gang activities is hinted to be far more direct than his modest standing as a “driver” would indicate. Indeed, there is a strong suggestion dropped that Nikolai caused the murder of Soyka (the shocking throat-slitting in the barber shop that opens the film). In the scene after Kirill gives Nikolai a truckload of champagne, Nikolai talks with Semyon and explains that the murder had been committed because Soyka was “talking about” Kirill. It’s evident that Nikolai himself could have been the source of any such notions about Soyka. There are other moments when we are led to contemplate the dense weave of possible causes and effects underlying the narrative.

It’s a rich film indeed. At the beginning I cautioned that you should see it before reading this entry. If you’ve done that, now I suggest seeing it again.

[Added October 18: I’m grateful to Eric Dienstfrey, who has responded to this entry with an intriguing suggestion about the “reversal” trait I noticed in these two films: “I think complementary films exist through most of Cronenberg’s career. Dead Ringers and M. Butterfly are two that come to mind, both films being about Jeremy Irons — to reference the old Woody Allen joke — at two with himself, either as twins, or internally as both a gay and straight individual. I also like the complement between Videodrome and The Dead Zone. In Videodrome, Woods loses control as he becomes more and more sadistic, whereas in The Dead Zone, Walken loses control as he becomes more and more heroic.”]