Archive for the 'Film technique: Widescreen' Category

THE GRAND BUDAPEST HOTEL: Wes Anderson takes the 4:3 challenge

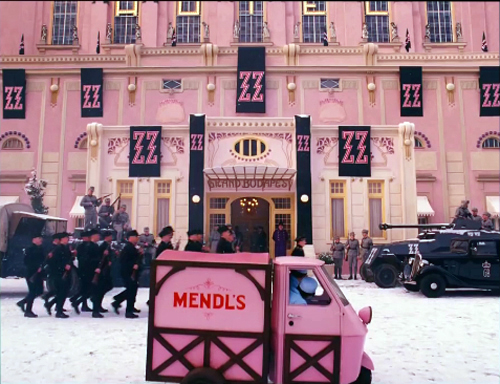

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014).

DB here:

Be shot-conscious! I urged in a blog entry some years ago. I illustrated the point with a tradition of staging and shooting that seemed simple and modest but was actually quite flashy, and even fashionable. Although many filmmakers resorted to it, either often or occasionally, critics hadn’t attended to it. Wes Anderson’s work yielded one of many examples of what I called (swiping from art historian Heinrich Wölfflin) a “planimetric” style.

Ideally, you should look at that entry before reading this one. (To encourage you, I link it again. Not for the last time.) Very briefly, this style involves a frontal presentation of the action. You frame people against a perpendicular background, as if they were in a police line-up. Usually you face them to camera, as in this shot from Godard’s Made in USA.

As we’ll see, sometimes you can frame the characters at right angles to the camera, or turned directly away from the camera. Here are examples from Napoleon Dynamite and from Angelopoulos’ The Traveling Players. (Is this the first time these two movies have been mentioned together?)

The key idea is that the people and the setting aren’t observed from an oblique angle; if the background is perpendicular, the people will stand or sit at 90 or 180 degrees to that.

You can arrange them in some depth too, but again, they are stacked in perpendicular fashion, making each area a pretty strict plane. Here’s an example from Pulp Fiction.

One point of my earlier entry is that this is a surprisingly old strategy; Keaton used it occasionally, and Godard was using it heavily fifty years ago. Here are two shots from Contempt (Le Mépris, 1963).

It has endured in some surprising places. It’s now a go-to option for one-off effects in mainstream cinema. Here are examples from Shutter Island and The Secret Life of Walter Mitty (2013 version).

A few filmmakers make it the basis of an entire film, as I indicate in this entry on Oliveira’s Gebo and the Shadow. And since I wrote the original entry, I’ve drawn on other examples from time to time, particularly from directors who are pastiching Ozu to some degree or another.

Still, Anderson is today the most widely visible example of the style, partly because while others use it sporadically, he is single-minded about it. He has made people shot-conscious (at least when they watch his movies). So after seeing his newest film, I thought it would be fun to think about what distinguishes his approach.

Playing with planes

With the release of The Grand Budapest Hotel, several bloggers have pointed to recurring compositional features, most obviously bilateral symmetry. I’d just add that such symmetry is often used by practitioners of the planimetric approach, with results that sometimes exceed Anderson’s. Here are two shots from Angelopoulos’ Weeping Meadow.

When you think about it, it takes a brave filmmaker (e.g., Godard) to use this approach and not deploy symmetry.

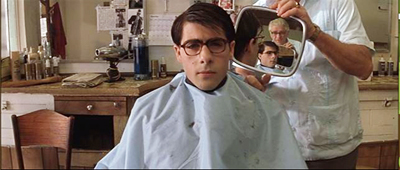

Anderson has used the planimetric approach more extensively in recent years, and he modifies it some distinctive ways. I think particularly of his habit of crowding people together in layers rather than stretching them along a single line. He makes some images look like group portraits or over-posed highschool yearbook shots (The Royal Tenenbaums; Fantastic Mr. Fox).

By employing the planimetric strategy, Anderson gains a somewhat awkward formality, a sense that we are looking from a distance into an enclosed world that sometimes looks back at us. There are as well the sort of comic possibilities that Keaton recognized in Neighbors and The General. A rigid perpendicular angle can endow action with an absurd geometry.

These apparently simple framings often evoke a world of childhood. Just as Kitano Takeshi shows us gangsters behaving like little boys, Anderson’s dollhouse-room frames make adults seem to be toy people arranged just so–like items laid out in a Joseph Cornell box. It’s a style suitable for magical-realist premises like The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, and in Moonrise Kingdom it finds its echo in children’s illustrated books.

All in all, then, I have to salute an American filmmaker who thinks about his images carefully and has incited sensitive viewers to notice them. I think we should go further, though. We can ask: How does Anderson, staying loyal to this tradition, vary the look of the shots? And how does he cut them together?

Cutting around

Consider the editing option first. Unless every scene is to consist of only one shot, the question comes up: How do you maintain the style while cutting? Either you make all your cuts axial, straight in or straight back.; or you create a sort of compass-point editing. This can involve cutting 180 degrees, to what’s “behind” the camera in the initial shot. So if characters are confronting one another, the camera is in effect sitting between them as each looks over or through the lens at the other (Ozu’s Late Autumn).

In effect, this option respects the classic 180-degree line, or axis of action, between the characters. It’s just that the camera sits right on that line. Parking the camera on the axis is a common tactic for subjective cutting, showing us first a person looking, more or less at the camera, then what she or he sees from their vantage point. Our example in Film Art: An Introduction comes from Rear Window.

Ozu used this 180-degree reversal often, but not absolutely; he had a more complicated way of conceiving space, and the 180-degree frontal cuts were only part of it. Kitano made a simpler variant central to his early films.

When I asked Kitano why he did it, he explained that it was exactly the way people saw each other in ordinary life. We face each other. He then added that he was such a naive director when he started that it was the only way he knew to set up scenes. We get kindred images in Terence Davies’ work; his frontality may owe something to the Hollywood musical.

Compass-point editing offers another possibility, that of cutting at 90-degree angles to the background plane or the figures’ position. Chantal Akerman does it throughout Jeanne Dielman 23 Quai du Commerce 1080 Bruxelles (1975).

Anderson exercises all these cutting options inThe Grand Budapest Hotel. Here a planimetric profile 2-shot yields two frontal shots; we shift 90 degrees and then 180 degrees.

Now here’s a 90-degree shift for the reverse shot.

In the passage below, the first cut rotates 90 degrees, and the second cuts in right on the lens axis. In this tradition, an axial cut respects the perpendicular layout of the space.

In such cutting patterns, the compositions keep the action in the same upper zone of the frame from shot to shot. As a result, our eye doesn’t wander much. In long shots, Anderson sometimes follows the classic Hollywood practice of allowing some decentering, as long as the cuts balance one off-center composition against another. Here the changing angles obey the compass-point principle across three shots, and they crisply shift the emphasis from the right side of the frame to the center to the left.

Someone who wanted to deflate Anderson’s visual ambitions could say that his shots are monotonous. Having imposed a big constraint on himself, he’s now obliged to show us that this approach can be varied–in obvious or subtle ways.

One way is through lens length. Most planimetric filmmakers use long lenses, which flatten the space even more. The figures can look like clothes hanging on a line. But Anderson favors quite wide-angle lenses (often 40mm). These make horizontal lines bulge, as in early CinemaScope films (Rushmore, The Life Aquatic).

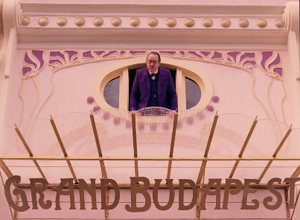

You can see similar distortions in the straight-on shots of the hotel desk in Grand Budapest, above.

Another way Anderson varies his images is by departing from straight-on angles. As long as the framing maintains a planimetric geometry, we can look down or up at the action. In this passage, again the camera makes 180-degree reverses. This contrasts with the more orthodox shot/reverse shot framings in a comparable scene in The Little Foxes.

In this spirit, Anderson can give us bird’s-eye views, as Matt Zoller Seitz points out in his sumptuous book-length interview with the director. It’s rare, but there are precedents, as in the work of the Coens. In one shot of The Hudsucker Proxy, a movie with an inordinate number of straight-down angles, the inflexible framing creates a joke.

Grand Budapest Hotel has room for some classically funny framings. If you want somebody to look lonely, common practice says, frame the figure off center in a long shot. Here Anderson seems to be having a joke on the convention. He presents it as a POV, although presumably if the Writer were looking at the mysterious man he would put the object of attention in the center of his field of vision.

I think that Anderson’s earliest films weren’t quite so strict in obeying the planimetric and compass-point strategies. Those options were often slipped in as alternatives to more orthodox framing and cutting. But as he’s become more rigorous about using them, he has found ways to put his stamp on some common techniques. Like Ozu incorporating devices of classical continuity into his unique stylistic system, Anderson can recruit certain conventions while staying faithful to his basic approach.

For instance, Anderson sneakily brings in the OTS–the over-the-shoulder framing standard in shot/ reverse-shot dialogue scenes. In one prison scene, Harvey Keitel’s Ludwig is granted an OTS that varies subtly from the more purely straight-on views.

Much the same thing happens with in the punching scene at the reading of the will, when frontal characters are assaulted by fists coming in as if in reverse angles.

Anderson has figured out another way to vary his compositions. I learned this before I saw the movie, thanks to some comments by the cinematographer Robert Yeoman (great name).

High or wide, and handsome

Rushmore (1998).

To get the criticky part of this entry out of the way: The Grand Budapest Hotel has all the charm, fussiness, and intricate whimsy typical of Anderson’s work. As often in his films, it cuts its preciosity with moments of offhand brutality (sliced-off fingers) and flashes of naughty sexuality (fellatio, the lesbian painting). With its ensemble cast, sometimes deployed in cameos, it suggests a PoMo remake of those sprawling, self-congratulatory spoofs of the 1960s like The Great Race, Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines, and It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. (The film’s title evokes those all-star films set in hotels, like Grand Hotel and Hotel Berlin.) It’s much better than those, partly because it engages in an oblique way with history, creating a comic-pathetic alternative account of Nazi imperialism. It imagines the collapse of Europe in operetta terms, filtered through Anderson’s pawky humor and distinctive style. I admired the film but don’t feel able to analyze it much after only one viewing. Fortunately for me if not you, its stylistic aspects fit today’s sermonette.

The Grand Budapest Hotel is set in several time periods, and they’re presented via The Blog’s old friend, the device of flashbacks within flashbacks. One character recalls the past or tells a story, and inside that line of action another character recalls or recounts a story, and so on. In Grand Budapest Hotel we move from the present, more or less, to events in the 1980s, then the 1960s, and eventually the 1930s, which constitute the central episodes.

Anderson has shot the frame stories in different aspect ratios. It’s 1.85 for the near present and the 1980s, when the Author recounts meeting the hotel owner. That meeting, set in the 1960s, is shown in 2.40, the anamorphic aspect ratio. The central story, taking place in the 1930s, is presented in classic 1.37, or 4:3 imagery. With typical Anderson butterfly-collector wit, each era gets a ratio that could have been used in a movie at the time. It’s remarkable that Anderson could persuade Fox Searchlight to let him do this.

Most commercial releases in the 1950s and afterward were filmed in some widescreen ratio. In the early days, a popular option was a sort of clothesline staging, centering a single character or balancing others around the central axis: two side by side, three across, four as a pair of pairs, and so on. These shots are from Demetrius and the Gladiators and How to Marry a Millionaire.

Thanks to the widening of the frame, there is less air above the characters and less ground below them. The empty spaces are typically on the sides, particularly in the anamorphic 2.40 ratio. The problem of filling that up was solved, at least for some directors, by moving the camera very close to the actors. Spielberg remarked that he began shooting more close-ups when he filmed in anamorphic.

If you’re inclined to the planimetric approach, it fits the wider format nicely. Anderson wasn’t worried by the extra acreage; he just used the set or empty areas to balance one side against the other. Shots of only one character could be centered, as if posed, and shots of groups could be arranged more or less symmetrically, as in this passage from Moonrise Kingdom. Central perspective helps drive your eye to the main items.

In Grand Budapest, Anderson’s signature framings fit snugly into the scenes shot in 1.85 and 2.40. (The latter has been his favored ratio over the years.) But what about the 1.37 scenes? This brings me to Mr. Yeoman’s remark.

Explaining why he and Anderson watched a lot of films from the 1930s, especially by Lubitsch, Yeoman notes:

We looked at those more to familiarize ourselves with the 1.37:1 aspect ratio, which Wes wanted to use for the 1930s sequences. This aspect ratio opens up some interesting compositional possibilities; we often gave people a lot more headroom than is customary. A two-shot tends to be a little wider than the same shot in anamorphic. It was a format I’d never used before on a movie, and it was a fun departure. You can get accustomed to 1.85 or 2.40 to the point that the shots become more predictable.

Put it another way: Anderson’s penchant for centering and symmetry inclines him toward widescreen compositions that could be simply cropped right and left to fit the 1.37 ratio. His single characters and huddled groups could remain much as before. But in more distant framings you might get a lot of extra space at top and bottom–areas that simply aren’t there in the wide ratios. In other words, Anderson’s multi-format strategy gave him a new problem in maintaining his signature style.

How did he solve it? Many Budapest Hotel shots do leave considerable headroom, as you see in most of the 1.37 examples above. But other shots show Anderson filling his 4:3 frame in varied and engaging ways.

As Ozu showed, for instance, the planimetric option can fill the frame’s upper area when the camera height is below eye level. During the conversation in the car, above, Anderson gets the head of M. Ivan (Bill Murray) in the top of the frame thanks to a low angle. Here are two more examples of filling the upper reaches of the format by use of a lowish camera position.

In the elevator shot, the headroom becomes comic, with M. Gustave and Madame D. seated on the right, the morose bellboy filling the vertical area on the left, and Zero in the middle. The empty space above the couple creates a lively imbalance emphasizing them in a way different from the very balanced framing that centers Henckel among his men.

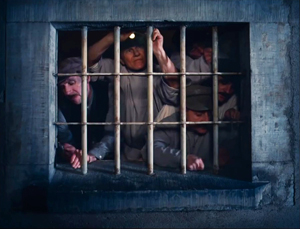

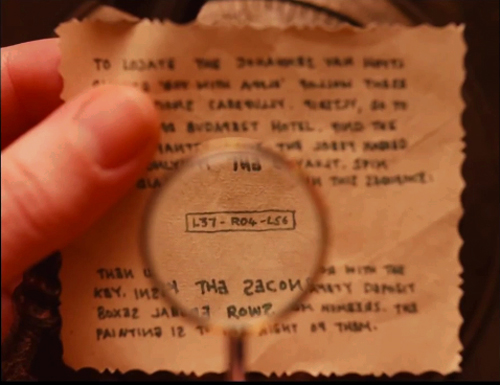

The set can cooperate. In the first shot below, Zero’s and Agatha’s centered embrace leaves lots of headroom, but the slightly disheveled stack of pastry boxes in the upper background contributes to the sense that they’re engulfed. In the second shot below, part of its humor comes from the rigid geometry of the grid and the way M. Gustave and his colleagues fill in the matrix with their intent faces and busy hands.

In all, Anderson seems to me to find intringuing ways to create visual interest in the 4:3 format. But as with any severe style, you wonder about what’s been lost.

Most obviously, Anderson loses some of the intimacy that comes with more angular and less strict approaches to the classic ratio. We like to see people from 3/4 views too. We also like depth shots that plunge us into a dynamic, diagonal playing space. Here’s a shot from John Huston’s In This Our Life, as precious in its own way as Anderson’s imagery.

As Hogarth pointed out, with the serpentine line in painting and drawing, such shots can lead our eye on “a wanton kind of chase.”

Because directors of the 1920s-1940s accepted a wider range of compositional options than Anderson embraces, headroom simply wasn’t an important problem, as in the Huston shot. Even in simpler shots, classical uses of the 4:3 ratio permitted a flexible organization of figures.

Centered symmetry against a flat ground is a fairly easy compositional strategy, after all. It wasn’t used much in the mainstream tradition because it looks artificial; perhaps only with the rise of art cinema was this sort of self-conscious composition welcomed. In any case, sticking with symmetry sacrifices the more delicate spotting of figures and faces around the frame.

A lot of visual art tries for more supple and subtle twists, torsions, and counterbalancing. Apart from organizing your space along the horizontal and vertical axes, you can try to set figures in delicate array along diagonals. This is why some old-time cinematographers argued that the 4:3 ratio was the best suited to the human body: it can flatter it from any angle.

To get a sense of these possibilities, I’ve compiled a little collection of images from a film that doesn’t boast any outrageously pretty shots: Otto Preminger’s Angel Face (1953). It’s typical of the unassertive approach we find in Preminger’s work of the 1940s and 1950s. He avoids the flashy depth of the post-Kane directors and offers something less aggressive but no less fascinating. Composition and staging integrate expressions, posture, glances, and gestures to create a smooth flow of action. My samples also indicate how rare straight-on views of faces and bodies are in American studio cinema. The 3/4 angle rules.

As with the American films of Lang, Preminger’s work displays a style that’s tough to analyze because the technique isn’t obvious. There’s a marvelous variety in the ways that the 4:3 ratio can render a single figure or two figures, or three, shifting them not around the perfect center of the picture format but around curves and diagonal axes–that yield interest in their own right.

This last comparison isn’t a slam on Anderson. I think well of many of his films, particularly the most recent ones, and I appreciate anyone who takes on a challenge of narrowing his range of creative choices. Once you narrow that range, it turns out there’s a host of new possibilities that pop out. Call it the Ozu strategy: refine your means and you discover nuances nobody else notices.

Still, in art as in life, every choice is a trade-off. It’s worth remembering what one loses by pursuing a particular path. By sticking to his signature look in working with 4:3, Anderson gave himself a problem that didn’t exist for directors of an earlier time, the problem of maintaining a frontal style in a squarish format. I’m glad he faced it and solved it. But I’m also glad that classical filmmakers, quite intuitively, showed how much you could do with an alternative option.

Without any conspiring between us, Matt Zoller Seitz, top expert on Wes Anderson, has just urged critics to write more about film form–to be, among other things, shot-conscious.

Iain Stasukevich’s American Cinematographer article on the making of The Grand Budapest Hotel is well worth your attention beyond the technical matter I latched onto.

The Huston image came to hand because of the previous entry. Go there for more instances of the sort of framing and staging that Anderson and his planimetric colleagues don’t aim at.

I survey the planimetric style in On the History of Film Style and in Figures Traced in Light. A search of this blog’s archive will bring other instances to light. I analyze Ozu’s style in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, available as a pdf here. For more on CinemaScope, you can visit my online lecture.

P.S. 27 March (Hong Kong time): Jonah Horwitz writes with a useful point:

One thing I would add to your summary is that as early as Rushmore, most notably in The Darjeeling Limited, Anderson purposely inserts into his limited stylistic palette selected, isolated “foreign” devices like loose framings, handheld camera, and relatively aimless zooms (as opposed to his more common precise shock-zooms). In some cases, as in the drama-club staging of “Serpico” in Rushmore, these devices serve as citations, in that case to “realist” New Hollywood cinematography. But they also feel very much like the exceptions that prove the rule: they stand out from his usual stylistic register so much that they effectively reinforce the latter. I’m looking forward to seeing Grand Budapest to see if this continues, or if he emphasizes instead a further refinement of his typical gestures.

I agree with Jonah that importing foreign devices often throws into relief a filmmaker’s signature style–a matter of a film’s intrinsic norm getting reinforced by some marked deviation from it. I think of Ozu’s pans or tracking shots, which occur in all his black and white films, and which often just remind us how narrow the style is in the rest of the movie. And sometimes, as in The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice, those camera movements are hybrids or compromises with with his static style. Thanks to Jonah for corresponding.

P.P.S. 27 March: This entry has been revised to eliminate an error. Originally I had said that the play with aspect ratios in the film wouldn’t have been possible before digital projection. Bryce Utting wrote to point out that it was indeed possible on film, since Peter Greenaway’s Pillow Book used both 1.85 and anamorphic widescreen. I had even seen the film and forgotten that! Thanks to Bryce for the correction.

P.P.P.S. 30 March (Hong Kong time): Jim Healy, impresario of our Wisconsin Cinematheque, writes to point out several other films that mix aspect ratios:

The first hour of Redford’s The Horse Whisperer, the urban-set part, is in 1.85. When the characters make it to the open horse country, the image widens to ‘scope. . . . The 2002 Disney animated feature Brother Bear (which isn’t so bad) is 1.85 for about the first 20 minutes and when the principal Inuit character (voiced by Joaquin Phoenix) is transformed into a bear, the picture goes to Scope.

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014).

Picking up the pieces; or, a Blog about previous blogs

A not-so-intimate bedroom scene from Cinerama Holiday (1955).

DB here:

Many of our blog entries are written in response to current events–a new movie, a film festival in progress, a development in film culture. Later we sometimes add a postscript (as here) bringing an entry up to date. Today, though, enough has happened in a lot of areas to push me to post the updates in a single stretch. It’s a sort of aggregate of chatty tailpieces to certain entries over the last year or so. Should the impulse seize you, you can return to an original entry, and there are other peekaboo links to keep you busy.

Out and about

Drug War.

Kristin wrote in praise of Neighbouring Sounds when she saw it at the Vancouver International Film Festival in 2012. Roger Ebert gave it a five-star rating, and A. O. Scott placed it on his annual Ten Best list. This network narrative is Brazil’s official entry for the Academy Awards. Sample Neighbouring Sounds here; the DVD is coming in May.

The annual Golden Horse Awards at Taipei have finished, and the Best Picture winner was the Singaporean Ilo Ilo, which neither Kristin nor I have seen. It would have to be exceptionally good to match the other films nominated, all of which we’ve discussed: Tsai Ming-liang’s Stray Dogs, Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster, Jia Zhang-ke’s A Touch of Sin, and (probably my favorite film of the year so far) Drug War, by Johnnie To Kei-fung. Stray Dogs did bring Tsai the Best Director award and his actor Lee Kang-sheng a trophy for best lead. Wong’s Grandmaster picked up six trophies, including top female lead and Best Cinematography. Jackie Chan won an award for Best Action Choreography. Although his CZ12 struck me as pretty dismal as a whole, its closing montage of Jackie stunts from across his career was more enjoyable than most feature-length films. In all, this has been a splendid year for Chinese-language cinema.

Back in the fall of 2012, I celebrated Flicker Alley‘s admirable release of This Is Cinerama, a very important film for those of us studying the history of film technology. Now Jeff Masino and his colleagues have taken the next step by releasing combo DVD-Blu-ray sets of two more big pictures, Cinerama Holiday (1955), the sequel to the first release, and South Seas Adventure (1958), the fifth and last of the cycle. Both are in the Smilebox format, which compensates for the distortions that appear when the curved Cinerama image is projected as a rectangle. Fortunately, Smilebox retains the outlandish optics to a great extent. The image surmounting today’s entry would give Expressionist set designers a run for their money, and it recalls the Ames Room Experiments. Cinerama wrinkles the world in fabulous ways.

Filled out with facsimiles of the original souvenir books and supplemented with a host of extras putting the films in historical context, these discs are fine contributions to our understanding of widescreen cinema. Because film archives don’t have the facilities to screen Cinerama titles (if they even hold copies), we have never been able to study, or even see, films that now look gloriously peculiar. Dare we hope that, from The Alley or others, we’ll get The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962), a strange, clunky, likeable movie?

Bookish sorts

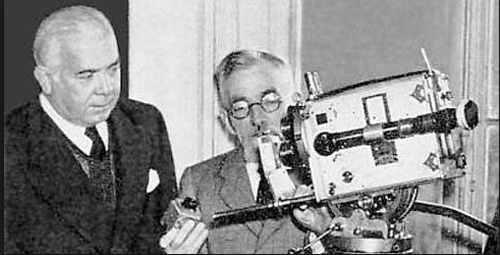

Spyros Skouras and Henri Chrétien.

2013 saw the first of our online video lectures, one on early film history and the other on CinemaScope. The response to them has been encouraging, but as usual nothing stands still. If I were preparing the ‘Scope one now, I would draw from the newly published CinemaScope: Selected Documents from the Spyros P. Skouras Archive. Skouras was President of 20th Century-Fox, and he kept close tabs on the hardware he acquired from Chrétien in 1953. This collection of documents, edited by Ilias Chrissochoidis, shows that Skouras saw ‘Scope as a way to follow Cinerama’s path and boost the studio’s profits. “I would hate to think what would have happened to us if we had not created CINEMASCOPE. . . . Certainly we could not have continued much longer with the terrific losses we have taken on so many of our pictures.” ‘

Scope didn’t rescue the industry, or even Fox, from the postwar doldrums, but some of the behind-the-scenes tactics of the format’s first years are revealed here. For example, Skouras hoped that filmmakers would put important information on the surround channels deployed by the format, in the hope that theatre owners would make more use of them. “Such scenes would have to be unusual ones, but even with my limited imagination I can visualize many scenes in which dialogue would be heard from only the rear or the sides of the theatre.” This seems fairly extreme even today.

Jeff Smith is a swell colleague here at UW–Madison. (He and I are teaching a seminar that’s just winding down. More about that, I hope, in a later entry.) In his May guest entry for us, Jeff wrote about the new immersive sound system Atmos. But he’s been busy filling hard covers too. Research articles by him have appeared in three new books on film sound.

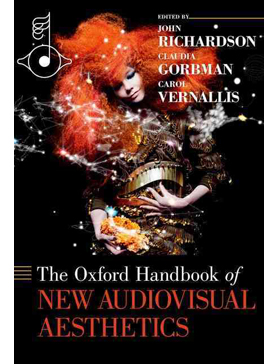

To Arved Ashby’s Popular Music and the New Auteur: Visionary Filmmakers after MTV Jeff contributed “O Brother, Where Chart Thou?: Pop Music and the Coen Brothers”–surely required reading in the light of Inside Llewyn Davis. He’s also a contributor to two monumental volumes that will set the course of future sound research. David Neumeyer has in The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies gathered a remarkable group of foundational chapters reviewing the state of the art. Jeff’s piece charts the changing relations between the film industry and the music industry, from The Jazz Singer to Napster and file-sharing. For another doorstop volume, The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, edited by John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis (three more top experts), includes a powerful essay in which Jeff shows how techniques of intensified continuity editing have their counterparts in scoring, recording, and sound mixing. Not to mention his forthcoming book on an altogether different subject, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. All in all, a busy man–the kind we like.

To Arved Ashby’s Popular Music and the New Auteur: Visionary Filmmakers after MTV Jeff contributed “O Brother, Where Chart Thou?: Pop Music and the Coen Brothers”–surely required reading in the light of Inside Llewyn Davis. He’s also a contributor to two monumental volumes that will set the course of future sound research. David Neumeyer has in The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies gathered a remarkable group of foundational chapters reviewing the state of the art. Jeff’s piece charts the changing relations between the film industry and the music industry, from The Jazz Singer to Napster and file-sharing. For another doorstop volume, The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, edited by John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis (three more top experts), includes a powerful essay in which Jeff shows how techniques of intensified continuity editing have their counterparts in scoring, recording, and sound mixing. Not to mention his forthcoming book on an altogether different subject, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. All in all, a busy man–the kind we like.

My March essay, “Murder Culture,” devoted some time to the women writers of the 1930s and 1940s who created the domestic suspense thriller–a genre I believe has been slighted in orthodox histories of crime and mystery fiction. The piece brought friendly correspondence from Sarah Weinman, editor of a new anthology from Penguin: Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives. She has assembled a fine collection, boasting pieces by Vera Caspary, Dorothy B. Hughes, Charlotte Armstrong, Dorothy Salisbury Davis, Margaret Millar, Patricia Highsmith, and Elisabeth Sanxay Holding (whom Raymond Chandler considered the best suspense writer in the business). These stories will whet your appetite for the excellent novels written by these still under-appreciated authors. Sarah’s wide-ranging introduction to the volume and her headnotes for each story will guide you all the way.

Finally, not quite a book but worth one: “The Watergate Theory of Screenwriting” by Larry Gross has been published in Filmmaker for Fall 2013. (It’s available online here to subscribers.) The essay is based on the keynote talk that Larry gave at the Screenwriting Research Network conference here in Madison.

Digital is so pushy

From Doddle.

Back in May, I provided an update on the progress of the digital conversion of motion-picture exhibition. Today, 90% of US and Canadian screens are digital, and over 80% worldwide are. (Thanks to David Hancock of IHS for these data.) I wish I could say the Great Big Digital Conversion was at last over and done with, but we know that we live in an age of ephemera, in which every technology is transitional. As I was finishing Pandora’s Digital Box in 2012, the chatter hovered around two costly tweaks.

The first involved higher frame rates. One rationale for going beyond the standard 24 fps was the prospect of greater brightness to compensate for the dimming resulting from 3D. Peter Jackson presented the first installment of his Hobbit film in 48 fps in some venues, and James Cameron claimed that Avatar 2 and its successor would utilize either 48 fps or 60 fps. And in January of this year some studio executives predicted that 48 fps would become standard.

Not soon, though. The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug will play in 48 fps on fewer than a thousand screens. Bryan Singer, who praised the process, has pulled back from handling the next X-Men movie at that frame rate. The problem is partly cost, with 48fps demanding more rendering and vast amounts of data storage. As far as I can tell, no one but Jackson and Cameron are planning big releases in the format.

The other innovation I mentioned in Pandora was laser projection. It too will brighten the screen, and according to its proponents it will also lower costs. Manufacturers are racing to build the machines. Christie has presented GI Joe: Retaliation in laser projection at AMC Theatres’ Burbank complex, and the firm expects to start installing the machines in early 2014. Seattle’s Cinerama Theatre is scheduled to be the first. NEC, the Japanese company, premiered its laser system at CineEurope in May. A basic NEC model designed for small screens (right) will cost about $38,000—an attractive price compared to the Xenon-lamp-driven digital projectors currently available. But the high-end NEC runs $170,000!

How to justify the costs? One Christie exec suggests branding: “Laser is a cool term that audiences immediately identify with.”

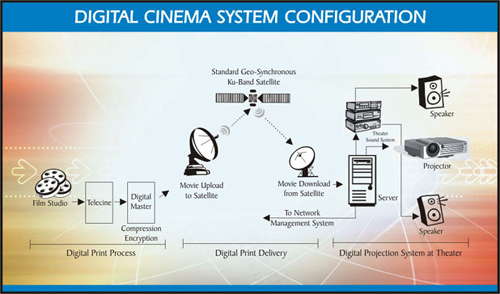

Perhaps the most important innovation since last spring’s entry involves an electronic delivery system. In October, the Digital Cinema Distribution Coalition, a consortium of the top three theatre chains along with Warners and Universal, launched a satellite and terrestrial network for delivering movie files to theatres. Theatres are equipped with satellite dishes, fiberoptic cable, and other hardware. The new practice will render the current system of shipping out hard drives obsolete, although the drives will probably continue for a time as backups. The DCDC has scheduled over thirty films to be sent out this way by the end of the year, and 17,000 screens in the Big Three’s chains are said to be hooked up. For more information, see David Hancock‘s IHS Analyst Commentary.

In the 1990s, satellite transmission was touted as the best way to send out digital films, and it was tried with Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones in 2001. Sometimes things move in spirals, not straight lines.

Speaking of the Conversion, an earlier entry pointed out the creative strategy used by the Lyric Theatre in Faulkton, South Dakota to finance its digital changeover. A gun raffle was announced on the Lyric’s Facebook page. Top prize was planned to be a set of three weapons: an AR-15 rifle, a shotgun, and a 1911 pistol.

The theatre’s screening season concluded, but the raffle is going forward, on New Year’s Eve, no less.

Television in public, movies in private

Dr. Who: Day of the Doctor (2013).

I can’t stand all this digital stuff. This is not what I signed up for. Even the fact that digital presentation is the way it is right now–I mean, it’s television in public, it’s just television in public. That’s how I feel about it. I came into this for film. —Quentin Tarantino

Spirals again. When attendance began to slump after 1947, Hollywood tried a lot of strategies–color, widescreen processes like Cinerama and ‘Scope, stereo sound, and not least “theatre television.” Prizefights, wrestling matches, and even operas were transmitted closed-circuit. Now theatre television is back, made possible by The Great Big Digital Convergence.

Godfrey Cheshire predicted some fourteen years ago that as theatres became “TV outside the home,” what we now call “alternative content” would become more common.

Pondering digital’s effects, most people base their expectations on the outgoing technology. They have a hard time grasping that, after film, the “moviegoing” experience will be completely reshaped by–and in the image of–television. To illustrate why, ponder this: if you were the executive in charge of exploiting Seinfeld’s last episode and you had the chance to beam it into thousands of theaters and charge, say, 25 dollars a seat, why in the hell would you not do that? Prior to digital theaters, you wouldn’t do it because the technology wouldn’t permit it. After digital, such transpositions will be inevitable because they’ll be enormously lucrative.

Godfrey’s prophecy has been fulfilled by all the plays, operas, and other attractions that run in multiplexes during the midweek or Sunday afternoon doldrums. His Seinfeld analogy was reactivated by last month’s screenings of Dr. Who: The Day of the Doctor in 3D. It was shown on 800 screens in seventy-five countries, from Angola to Zimbabwe, while also being broadcast on BBC TV (both flat and stereoscopic). The Beeb boasted that the per-screen average for the 23 November show beat that of The Hunger Games: Catching Fire. Globally, it took in $10 million, despite being available for free on TV and the Net. In the US, the event was coordinated by Fathom, a branch of National Cinemedia, a joint venture of the Big Three chains.

While some complained about dodgy 3D in the show, a surprisingly fannish piece in The Economist declared that “this landmark episode was buoyed up with fun, silliness, and hope.” The larger prospect is that other TV shows will take the hint and host season premieres or end-of-season cliffhangers in theatres. Many art house programmers would kill to show episodes of Game of Thrones or Mad Men, or even marathon runs of House of Cards. If it happens at all, I’d bet on Fathom getting there first.

I’ve had little to say, in this arena or in Pandora, about streaming and VOD, but these are becoming important corollaries of the Great Big Digital Convergence. Netflix in particular is expanding its reach, growing its subscriber base, creating original series, and enhancing its stock value, despite some ups and downs. At the same time, it’s pressing studios and exhibitors for the reduction in “windows,” the periods in which films are available on different platforms.

The theatrical window was traditionally the first, followed by second-run theatrical, airline and hotel viewings, pay cable, and so on down the line. Now that households have fast web connections, streaming disrupts that tidy business model. In October Ted Sarandos, Chief Content Officer for Netflix (right, with Ricky Gervais), suggested that even big pictures should go day-and-date on Netflix.

The theatrical window was traditionally the first, followed by second-run theatrical, airline and hotel viewings, pay cable, and so on down the line. Now that households have fast web connections, streaming disrupts that tidy business model. In October Ted Sarandos, Chief Content Officer for Netflix (right, with Ricky Gervais), suggested that even big pictures should go day-and-date on Netflix.

“Why not follow with the consumer’s desire to watch things when they want, instead of spending tens of millions of dollars to advertise to people who may not live near a theater, and then make them wait for four or five months before they can even see it?” he added. “They’re probably going to forget.”

Exhibitors howled. Sarandos quickly recanted, saying only that he wanted people to rethink the current intervals between theatrical and ancillary release.

Some observers speculated that his October remarks were staking out an extreme position he intended to moderate in negotiations down the line–possibly to suggest that mid-budgeted pictures would be good ones to experiment with on day-and-date. Perhaps too Netflix was emboldened by the much-publicized remarks of Spielberg and Lucas in a panel last June, when they indicated that the future for most movies was VOD, with multiplexes furnishing more costly entertainments for the few. (In the same session, Lucas predicted that brain implants would allow people to enjoy private movies, like dreams.)

In any event, windows are already shrinking. In 2000, the average theatrical run was 170 days; now it’s about 120 days. With about 40,000 screens in the US, films play off faster than ever before. Video piracy, which makes new pictures available well before legal DVD and VOD release, puts pressure on studios to shorten windows. It seems likely that the windows and the intervals between them will shrink, perhaps allowing films to go to all video formats as quickly as 30-45 days after the theatrical release ends.

Studios have incentives to shorten the windows, if only because a single promotional campaign can be kept going long enough for both theatrical and home release. In addition, buying or renting a movie with a couple of clicks encourages impulse purchasing, and the cost feels invisible until the credit-card bill comes. Nonetheless, commitment to day-and-date home delivery would be risky for the studios.

Hollywood is more than ever before playing to the global audience. Even with the VOD boom, digital purchase and rental constitute a small portion of the world’s movie transactions. According to IHS Media and Technology Digest, theatrical ticket sales, purchase and rental of physical media (DVD, Blu-ray) add up to nearly 12 billion transactions, while Pay Per View, streaming, and downloads come to only about a billion or so. (These categories omit subscription services like cable television and basic VOD on Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, and the like.) Moreover, customers in 2012 spent about 61 billion dollars buying tickets to movies, buying DVDs, and renting DVDs. Tania Loeffler of the IHS Digest writes of North America, the most developed market for digital sales and rental:

Movie purchases made online in North America increased year-on-year by 36.6 per cent to reach 29.2m transactions. The rental of movies online also increased, to 112m transactions, an increase of 57.3 per cent over 2011. Despite this strong growth, movies purchased or rented via over-the-top (OTT) online movie services still only accounted for a combined $836m, or 3.3 per cent of total consumer spending on movies in North America.

By contrast, worldwide consumer spending on theatrical movies actually grew in 2012, to a whopping $33.4 billion–over 50 % of all movie transactions. (Thank you, Russia and China.) And despite the decline of disc purchases and rentals, Loeffler estimates that physical media will still comprise about thirty per cent of worldwide movie transactions through to 2016.

Theatrical releases continue to offer studios the best deal. Because the prices of streaming and downloaded films are low, there is less to be gained from them. True, if windows shrink, the studios will demand that Netflix and its confrères price VOD at high levels, say $25-50 for an opening-weekend rental. But consumers used to cheap movies on demand could balk at premium pricing.

At present, digital delivery of movies to the home provides solid ancillary income to the distributors, even if it doesn’t yet offset the decline in physical media. Add in Imax and 3D upcharges, and things are proceeding well for the moment. Like the rest of us, moguls pay their mortgages in dollars, not percentages or transactions. As long as some hits keep coming, we should expect that studios will maintain an exclusive multiplex run for major releases, as the most currently reliable return on investment.

Orpheum metamorphosis

The New Orpheum Theatre, 216 State Street, 1927.

Another note on exhibition relates to the last commercial picture palace in downtown Madison, Wisconsin. My July 2012 entry related the conspiratorial tale of how the grand old Orpheum Theatre on State Street fell on hard times. In fall of 2012 the building seemed slated for foreclosure, but then maybe not. Last month Gus Paras, a hero of my initial post, stepped forward and bought the old place. According to Joe Tarr in our politics and culture weekly Isthmus, there’s a lot of work to do.

Plaster is crumbling off sections of the ceiling, the result of years of water damage from a leaky roof. The walls are littered with scratches and marks, in bad need of a paint job. A plastic garbage can sits in the theater, collecting water leaking from an upstairs urinal. Paras even found dried-up vomit in two spots on the carpet.

Making matters worse, Monona State Bank, which controlled the property while it was in foreclosure, filled in the “vaults” behind the theater, which means replacing the building’s frail boilers and air conditioning will be much more complicated and expensive.

“I don’t have any idea how I’ll get the boiler in and out,” Paras says. “The stairs are not strong enough.”

Envoi

Have any of you worked on a film, say, 10 years ago, and it comes out on Blu-ray and you look at it and think, “This isn’t the film I’ve shot”?

Bruno Delbonnel (DP, Inside Llewyn Davis): Always. Always.

Barry Ackroyd (DP, Captain Phillips): I’ll be watching and it’s in the wrong format.

So what is it like to devote your lives and careers to creating images that you know exist only momentarily in their absolute best state, that may never be seen by most people the way you would like them to be seen?

Sean Bobbitt (DP, Twelve Years a Slave): At least you get a chance to see it once. All you can do is hope that people will see an approximation of that. I’ve been to screenings where I’ve had to get up and walk out because I just couldn’t bear to watch the film in the state it was in. But at the end of the screening, people say, “That was fantastic. That was beautiful. Well done!” and you’re thinking, “If only they had seen the real thing.” We would drive ourselves mad if we worried too much about it.

On shrinking windows, see Andrew Wallenstein and Ramin Setoodeh, “Exhibitors Explode over Netflix Bomb,” Variety (5 November 2013), 16. The chart on this page doesn’t appear in Variety‘s online edition of the story. Tania Loeffer’s report, “Transactional Movies: The Big Picture,” appeared in IHS Screen Digest (now IHS Media and Technology Digest) for April 2013, 123-126. Douglas Gomery discusses the theatre television plans of the 1940s-early 1950s in his Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States, pp. 231-234. My envoi comes from a revealing conversation among cinematographers at The Hollywood Reporter.

A 2012 catchup blog chronicling earlier phases of these developments is here.

P.S. 23 December 2013: David Strohmaier, the creative force behind the Cinerama restorations, has put online the stirring original trailers for Search for Paradise (low resolution and high-definition) . David attended the U of Iowa when Kristin and I did, though alas we didn’t meet him. He deserves a big thank-you for all his work in making these extraordinary films available to us.

The Grandmaster.

Scoping things out: A new video lecture

A Star Is Born (1954).

DB here:

Cripes! It’s video-lecture fever!

Well, maybe that’s an exaggeration. Still, we do have something new for you.

A video analysis of constructive editing showed up last fall, and a rather long one called “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies” was posted earlier this year. Now comes one on the aesthetics of early CinemaScope in the US.

It’s a new version of a talk now retired from the lecture circuit and snugly cached on the web. I’m hoping both viewers and filmmakers will be interested in this, particularly in its analyses of staging and composition. The piece makes a more general argument about how new technologies offer both advantages and constraints.

“CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See without Glasses!” runs about fifty minutes. It’s our first one in HD, so it looks pretty nice on many displays. It could be shown in classes, and I’d be happy if teachers wanted to use it. As with our earlier entries, it’s also available on Vimeo here, where you can leave feedback if you want.

I’m also providing the chapter on Scope from Poetics of Cinema. Think of the lecture as the DVD and the chapter as the accompanying booklet. You can go to the essay if you want to dig deeper into the subject, see other examples of what I’m talking about, or learn the sources for my arguments.

By the way, if you’re interested in the art and craft of widescreen cinema, I’ve posted a web essay on Hong Kong anamorphic here.

As usual, I’m very grateful to my creative tech wranglers Erik Gunneson, who produced the video, and Peter Sengstock. Thanks as well to our web tsarina Meg Hamel.

I’ll have to suspend production of these video lectures for a while, but Kristin and I are hoping to float another novelty soon, perhaps in the next couple of months.

Thanks for everyone who has supported our work through Tweeting, Facebooking, linking, or just telling their friends.

Wild River (1960). From 35mm frame.

Tony and Theo

Man on Fire (Tony Scott, 2004); The Suspended Step of the Stork (Theo Angelopoulos, 1991).

DB here:

In January of 2012, while shooting The Other Sea, Theo Angelopoulos was struck by a motorcyclist and died soon afterward. In August, Tony Scott committed suicide by jumping off Los Angeles’ Vincent Thomas Bridge.

Both men mattered to cinema. But which cinema?

From 1970 onward, Angelopoulos produced solemn films about Greek history, world war, emigration, and the collapse of struggles for political change. His hallmark was the extended—some said excruciating—long take. He presented his work as that of a thoughtful and passionate intellectual, a witness to history (or as he sometimes said, History) who was telling us hard, melancholy truths. His work received little mainstream distribution outside Europe and Japan, and some of his best films weren’t circulated nontheatrically or on video. Severe and abrasive, he alienated powerful members of film culture and was reported to have responded sourly when he did not win Cannes’ top prize.

By contrast, after Top Gun (1986), Tony Scott came to be the prototype of the ADD Hollywood director, a master of the blockbuster action picture. He gleefully marshaled visceral technique to jolt the eye and hammer the ear. His movies were unabashed booty calls, spotlighting female pulchritude in a tone of laddish camaraderie in an all-male milieu (sports, the military, the workplace). Not lacking intelligence, he avoided the sweeping pronouncements that made Angelopoulos look pretentious, but his early partnering with Simpson and Bruckheimer stamped him as raucously vulgar. He even dated Brigitte Nielsen.

Extremes meet

Déja vu (2008); Eternity and a Day (1995).

The statuesque versus the kinetic, the monumental versus the ephemeral, ponderousness versus cheap flash: To all appearances, these men lived in different cinematic worlds. Their careers were oddly counterpointed too. Angelopoulos, a festival darling in the 1970s and 1980s, became more unfashionable. By the time of his last release, The Dust of Time (2009), some critics were openly scornful. Scott faced gibes from the start but won some critical respect in the 2000s. After his death, critics were calling him a master. To many, Angelopoulos’s stubborn allegiance to 1970s modernism looked old hat, while Scott’s bodaciousness and eye candy seemed to have finally seduced audiences and critics alike.

I confess that both give me qualms. When Angelopoulos strains for significance, as he does at many moments throughout his oeuvre and almost constantly in The Dust of Time, he arouses all my impatience with pretentious Eurocinema. When Scott builds a scene out of Fuck-you-motherfucker dialogue and lingering views of pole dancers he reminds me of just how low contemporary American cinema can sink. And the style of each one can become predictable–an angled shot down a street portends a pan in Angelopoulos, while once somebody sits down in a Scott movie the camera is likely to start to twirl.

Despite these misgivings, I find that I can admire and enjoy both men’s films quite a lot. Their most venturesome work offers us powerful experiences, and they can teach us things about cinema—not least, how creative filmmakers can rework the medium and its historical traditions.

And their worlds overlap at least a little. Both men treat cinema as an art of scale. To see Man on Fire (2004) or Alexander the Great (1981) on home video, no matter how big your monitor, is to shrink the films fatally. Correspondingly both men relied on spectacle, stuffing the screen with sweeping, startling effects. True, Scott’s spectacle is maximalist, while Angelopoulos’s is austere. Yet once you’ve calibrated your bandwidth, the train that rumbles through the migrant camp in The Weeping Meadow (2004) becomes no less rattling than the rogue locomotive in Unstoppable (2010). “Go big or go home” might be each man’s motto.

Both play games with narrative as well. As early as The Hunger (1983) Scott’s incessant crosscutting uses the soundtrack of one line of action to comment on another. The time looping of Domino (2005) and Déja Vu (2008) creates flashbacks, replays, revised outcomes, and jumping viewpoints. More sedately, Angelopoulos perfected the time-shifting long take. The camera movements of The Traveling Players (1975) glide among different eras. From scene to scene, Angelopoulos will provide few marks of tense. Scene B may follow A, or precede it by several years, and no Hollywoodish superimposed title will help us out. It may be several minutes before we realize that decades have passed.

Yet the time-scrambling both directors enjoy isn’t wholly at the service of drama. Storytelling takes on a curiously subsidiary role in their work. Neither filmmaker, it seems to me, is centrally interested in probing what many of us take to be the core of narrative—character psychology. This isn’t to say there aren’t poignant moments and glimpses of inner lives. But each director also leaps beyond them.

I think in fact that Tony and Theo explore what happens when narrative slips away, when cinematic textures and patterning are allowed to override drama—to inflate it, deflate it, thrust it to one side, take it as a pretext for something more tangibly enthralling. Both filmmakers seek to shape our perception and emotion, letting the fluctuations of images and sounds engender a kind of mesmeric attention in themselves.

They accomplish this within two different traditions, that of modern Hollywood and that of “art cinema.” Yet they share a commitment to going beyond the given: Each director pushes his tradition to a limit.

Pulp fictions

Déja vu (2008).

Scott’s tradition is, most broadly, Hollywood narrative cinema, and up to a point he plays along. The plots are propelled by goal-directed characters who clash with others, and the results are contests (Top Gun, Days of Thunder, 1990), investigations (Beverly Hills Cop II, 1987; Man on Fire, Deja Vu), pursuits and conspiracies (Revenge, 1990; The Last Boy Scout, 1991; True Romance, 1993; The Fan, 1996; Enemy of the State, 1998; Spy Game, 2001; Domino), and ticking-clock suspense situations (Crimson Tide, 1995; The Taking of Pelham 123, 2009; Unstoppable).

At the center there usually stands one man, or a duo, who must undergo a test of courage and resourcefulness. In The Fan, an example of what Kristin has called the parallel-protagonist movie, a normal guy finds himself pursued by an obsessed admirer. A woman might serve as a gutsy partner, as in True Romance, or the object of the quest (Revenge, Spy Game), or the reward for success (The Last Boy Scout, Unstoppable). Only Domino has a female protagonist who survives through being as abrasive, dirty-minded, and foul-mouthed as her male partners and adversaries. Yet by her own admission, she has daddy issues and a longing to return to cozy wealth.

At bottom, then, Scott worked with straightforward pulp stories, and for about a decade he played them in the proper spirit. But with Enemy of the State (1998) he began to use the slipperier narrational strategies spreading through Hollywood of his time. Like Tarantino, who supplied the script of True Romance, Scott became willing—inspired, he suggests, by rock’n’roll and the films of Nicholas Roeg—to go a little wild.

His scripts started playing with what we usually call point of view. Some films become markedly, not to say traumatically, subjective. Spy Game splits the protagonist figure into two and gives us each one’s standpoint on the action. The Fan, from Peter Abraham’s fine novel, tracks a man’s obsession as it turns deadly. Man on Fire plunges into John Creasy’s mental world as he distills pain, guilt, piety, and alcoholism into a merciless sadism.

By the time we get to Domino, story presentation is pitilessly disjunctive. The main action is bracketed by a conventional frame showing the heroine telling her story to a police officer. A good thing, too; we couldn’t follow the action without her commentary. The tale fractures into quickfire AV displays, with pauses, backing-and-filling, alternative outcomes, and even written titles, as if we were getting the most juice-jangled PowerPoint talk in history.

Another multiplication of perspective takes place via spy games. Most directors situate modern surveillance techniques within their story world; Paul Greengrass seems happiest shooting people bent over workstations. When your average director gives you a swooping helicopter shot, you don’t take it as the POV of a sinister government agency or a sensationalistic TV livecam. In Scott’s late films you’re likely to. He realized that all today’s security cameras, cellphones, and hostile eyes in the sky can do two useful things. They can chop story space and time into teasing fragments, and they can refresh the shot’s visual texture.

For quite some time Hollywood movies have used television for exposition. Characters tap into the flow of story events via TV broadcasts, and sometimes, as in The Siege (1998), the film simply cuts in news clips presented directly to us, without any mediating character. Passages like these, a contemporary equivalent of the newspaper headlines and radio broadcasts of classic studio cinema, usually smooth out the plot, linking things concisely.

But Scott takes pleasure in playing up the disparities among the footage, cutting from “direct” presentation of material to mediated images and sounds. In the conspiracy films, the video images seem to be coming from a vast image bank or database that the film is sampling on the fly. Moreover, the constant interruption of one shot by another, seen on computer or news broadcast or spycam, creates a nervous visual narration. In effect, Scott imports the mixed-format collages of Stone’s JFK (1991) into the action film (with more skill than Stone summoned up for Natural Born Killers of 1994 and U-Turn of 1997).

At the level of presentation, though, a narrower tradition shapes Scott’s style. In interviews and director commentaries he ceaselessly reminds us that he started out as a painter, and he has, I think, brought a fresh pictorial intelligence to the action film.

Too much is not enough

Days of Thunder (1990).

Like Michael Mann, Scott seems to have felt the need to give the action picture a dose of self-conscious artistry. The problem was the competition. The gold standard of the genre emerged in 1988 with the poised, tightly-woven classicism of John McTiernan’s Die Hard. How was an ambitious director to match that? Most directors were embracing variants of a style I’ve dubbed “intensified continuity”—fast cutting, simple staging, polar extremes of lens lengths, almost constant camera movement. The efficient but routine Richard Donner and Renny Harlin worked along these lines, while Michael Bay represented the style in almost pristine form. But what if a director who had trained as a painter at the Royal College of Art could take intensified continuity into new territory?

So yes, go along with the trend toward fast cutting; but make it even faster. In an era in the average shot in the average film runs between 3 and 5 seconds, why not make them 2 seconds? Or less? This was Scott’s choice from The Fan (1996) on. He seldom repeats a setup, largely because he has so many cameras stationed on the perimeter of the scene. Man on Fire contains at least 4100 shots, Domino over 5000, but perhaps we will never know just how many. Long passages are built out of multiple exposures, superimpositions, stop-and-go motion, and color shifts within a “shot.” The cut ceases to be a firm boundary as layers float up and slip away.

At times Scott, like Vertov in Man with a Movie Camera and Pat O’Neill in Power and Water, simply abandons the concept of a discrete shot, letting images seep through his frame.

And yes, move the camera; but move it in arabesques quite different from McTiernan’s unfussy following shots and tense track-ins. In particular, take the swirling camera as a given but then pivot your subject a bit as well. Cutting from one rotation to another can yield a little ballet of sculptural solidity, with barriers gliding by in the foreground and bursts of tonal values throughout. Here’s an example from Unstoppable.

In the 1980s and early 1990s films, Scott mixed haze and sharpness. Some scenes would be shot in metallic or earth tones and swathed in those smoky layers brother Ridley had popularized in Blade Runner. Other scenes would boast silhouettes, crisp edges, and blocks of bright color. Consider these images from Revenge, The Last Boy Scout (2 frames) and True Romance.

All framings–long-shot, medium-shot, close-up–tend to be covered by several cameras with very long lenses, which flatten and abstract the image. Later, having discovered the power of cross-processing reversal stock, Scott mostly gave up haze for what he called hyperrealism: high contrasts, along with Hockneyish color ripeness and thick but still transparent shadow regions.

Scott adds to the canons of intensified continuity the punch of the axial cut, that shot change that yanks figures toward or away from us (an effect that his last films mimicked by snap-zooms). Combined with long lenses set at various distances, this option creates a sense of constantly losing and refinding the point of the shot. As Connie swivels during a later stretch of the Unstoppable scene, the axial cut with different backgrounds pins her against varied blocks of color.

Critics complained that Scott’s style reminded them of MTV videos and commercials, a great number of which the Scott brothers produced. But there’s nothing inherently wrong with filmmakers drawing inspiration from advertising (as painters like Warhol and Stuart Davis did) or from video clips (as Wong Kar-wai seems to have done). What matters is what you do with your sources. It seems clear that Scott subjected these techniques to a new pressure, using them to thrust current norms to new extremes.

Intensified continuity, as I argued in The Way Hollywood Tells It, offers a mannerist version of classic continuity. If that’s accurate, then we might say that Scott provides a Rococo variant of intensified continuity itself. Michael Mann, another pictorialist, is more of a purist, seeking a sober gravity, while Scott doodles and scrawls across the surface of his scenes. Not only does he interpose reflections, rain, dust, and other particles between his subjects and us, but he reiterates lines of dialogue via supered titles.

Mann lets us soak up his images, but Scott tosses out one gorgeous composition after another in bewildering profusion. In the accelerated late films, they barely have time to register. The film seems to whisk away under our eyes. Shots lack an organic arc; they’re lopped off. Partial impressions pile up, defeating our urge to dwell on a composition. Sometimes you can’t trust your eyes. During the kidnap scene of Man on Fire, a thug prepares to shoot back at Creasy as a burst of flame is reflected in his car.

Problem is, nothing has caught fire in the scene; for once, no explosions. It’s purely a crazy jolt, literalizing the idea of a “firefight” without any realistic motivation.

These techniques are motivated to some degree by story demands: the need to suggest a mental state, to portray a heroic posture, or to amp up a fight or chase. But Scott’s visual and auditory handling exceeds the demands of clear storytelling. He wraps the most perfunctory dialogue scene in a dazzling embroidery that arrests attention in its own right. Mere decoration? I’d agree. Still, decorative art isn’t an unworthy calling, and decoration pursued with conviction and inventiveness demands our notice.

And this decoration isn’t dainty. Domino, Unstoppable, and the second half of Man on Fire have a grunge dimension, with shots that make our world look at once harsh and dazzling. Scott could be our Sam Fuller (complete with cigar), and Domino could be his Naked Kiss. Fuller might echo Scott’s gaffer, who said of Domino: It isn’t pretty, but it is beautiful.

Threnody

Ulysses’ Gaze (1995).

From The Birth of a Nation to Lincoln, American studio cinema tends to show grand historical events intertwining with the private dramas of great leaders or common folk. But there were other options. Eisenstein’s first three films—Strike, Battleship Potemkin, and October—floated the possibility of the “mass protagonist.” In these films, history is made by groups, and individuals are given largely symbolic roles. During the politicized 1960s, this model was taken up by filmmakers on the left.

The filmmaker who explored this option most fully was the Hungarian Miklós Jancsó. Although his films seem to be little-known today, he was a major force in reviving the idea of presenting history through group dynamics. Individuals play a role in The Round-Up (1965), Silence and Cry (1968), and The Confrontation (aka Bright Winds, 1969), but they are usually bereft of personal psychology. These figures are defined by their roles in a struggle—a civil war, a revolution, a clash with a domineering regime—and they are often pawns in a game of shifting power.

The Red and the White (1967), available on DVD, is a good example. This saga of the Russian Civil War that followed the 1917 revolution takes us through skirmishes between clashing armies, the tactics pursued by a squadron of Hungarian volunteers, and episodes in a Red Cross station. Individuals come to the fore briefly but are likely to vanish from later scenes, or simply die on the spot. One young Hungarian threads his way through the action, but he can hardly be said to be a point-of-view character, and we learn nothing of his background or motives. A great deal of the film is taken up with rituals of questioning prisoners, torturing and shooting captives, and ravaging innocents caught in the crossfire. At the climax, a tattered Red unit marches defiantly toward a superior White force, the entire confrontation played out in a stupendous landscape.

The Red and the White could defend itself from charges of formalism through its affinity with Soviet-style war dramas, but as Jancsó went on to examine episodes in Hungarian history, he soon gave up realism. He staged historical events in symbolic forms, on a bare plain or as obscure rituals in festivals rippling with music and dance. Examples are Agnus Dei (1972), and Red Psalm (1969; available on DVD). These films relied on endlessly tracking, craning, and zooming; the camera floats, and space stretches and squashes. The result was long-take extravaganzas. The Red and the White has fewer than two hundred shots; The Confrontation (1969) only thirty-five; Sirocco (1969) and Elektra, My Love (1974; on DVD) fewer than a dozen.

It seems to me that after Angelopoulos’s first film, he picked up and expanded Jancsó’s idea of investigating a nation’s history through mass dynamics and stripped-down spectacle. He proceeded more or less chronologically through modern Greek history. Days of ‘36 (1972) examines the dictatorial rule of General Metaxas (1937-1941) while The Traveling Players of 1975 covers the Nazi occupation and postwar civil strife. The Hunters (1977) revives the years from the civil war (1944-1949) to the mid-1960s through an arresting narrative device: present-day hunters find the corpse of a civil war partisan, as fresh as if killed yesterday. Alexander the Great (1980) doubles back to a period from the turn of the century until the 1930s, showing a bandit taking power over a remote village.

This tetralogy did pick out individuals, but it made them symbols of larger forces, often through names drawn from history or mythology. The travelling players are named Electra, Orestes, and the like; Alexander the bandit is a brutish version of his legendary namesake. Nevertheless, Angelopoulos’ presentation did little to acquaint us with them from the inside. He drew on none of Scott’s subjective tricks to convey instant impressions or fragments of memory; even his quasi-subjective flashbacks were likely to include the protagonist as he is today in the scene from the past.

Popular filmmaking depends on our accessing characters’ thoughts and feelings, but Angelopoulos largely gave that up. He made his plots depend on large-scale political forces. Sometimes, as in Days of ’36 and The Hunters, we are taken behind the scenes and shown the machinations of power, but usually history unfolds through impersonal forces—often outside the frame. When the apparatus of power is made visible, it’s through visions of police, soldiers, or other authorities. And those are often presented as rigid and impersonal.

Below, in Ulysses’ Gaze, a candlelight march is confronted by row upon row of police. The calm, mechanical way the officers fill up the middle ground makes the impending conflict quite suspenseful. When you think the composition, and the confrontation, have exhausted the shot’s duration and space, a crowd of citizens appears in the foreground to bear witness. All three groups are made into homogeneous blocks through the distant framing and the consistency of texture (flickering candles, uniforms, umbrellas).

The drama comes when our characters are forced to respond to the forces of oppression. They flee, they hide, or they’re captured and sent to prison or execution or exile. It’s an inglorious version of history, filtered through a Brechtian belief that distancing us from charged situations, presenting emotions dryly rather than melodramatically, can bring lucidity and a grasp of macro-dynamics. But Angelopoulos also traced his the origins of his oblique, sometimes opaque style to the pressures of censorship. Under the Greek junta, it was impossible to speak about history directly.

So I sought a secret language. Tacit understanding of the story. The temps morts in plotting a conspiracy. The unsaid. Elliptical discourse as an aesthetic principle. A film in which everything that is important takes place outside the frame.

Even after censorship ceased, Angelopoulos continued in this taciturn vein, making his films thoroughly decentered and dedramatized.

Yet in the 1980s, he tried to offer audiences more. He began to put distinct and individualized characters at the center of his films, and he achieved his survey of political change by sending them on modern Odysseys. In Voyage to Cythera (1983) a film director is conceiving a new project, and he visualizes the story of an elderly Communist let out of prison and returning to his village. In The Beekeeper (1985), a schoolteacher abandons his family and embarks on a trip across a bleak modern Greece. Landscape in the Mist (1988) follows two children convinced that their emigrant father is waiting for them just across the border. In The Suspended Step of the Stork (1991) a television journalist tracks down a prominent politician who seems to be hiding in a refugee village.

Two 1990s films plumb the characters’ pasts in more detail. Ulysses’ Gaze (1995) follows an archivist (called simply A) searching for a lost film and his own family history in the Balkans. In Eternity and a Day (1998), a poet in the last days of his life reflects on his life while accompanying a boy trying to return to Albania.

In the 2000s Angelopoulos began again thinking on an epic scale. Trilogy: The Weeping Meadow (2004) announced itself as the first installment in nothing less than a history of the twentieth century told through the experience of a single family. Concentrating on a refugee couple—one Russian, one Greek—it sets their fugitive romance against the events of World War I, the rise of Fascism, and the Greek Civil War, while also hinting at parallels to Attic tragedy. The second installment, The Dust of Time (2009) runs parallel to Voyage to Cythera and Ulysses’ Gaze in centering on a filmmaker, but he becomes less central to the plot than his father, his mother, and his mother’s lover–all victims of 1950s Soviet Communism who survive to see the fall of the Berlin wall.

Over these years, Angelopoulos collaborated with the Italian screenwriter Tonino Guerra (who died about two months after the director). Guerra, who worked with Antonioni, Fellini, the Tavianis, and many other directors, may have helped turn Angelopoulos toward less forbidding storytelling. The more vividly drawn protagonists of the late work were often played by well-established actors (Mastrioanni, Moreau, Ganz, Keitel, Dafoe, Piccoli), and two of the films center on children, one common way to kindle emotion. Eleni Karaindrou’s scores, full of threnodies rising up from massed strings, by also gave the films after Cythera a plangent warmth reminiscent of doleful musical pieces by Henryk Górecki and Arvo Pärt.

Still, these late films are only comparatively more accessible. Their stories come across as downbeat, episodic, relatively empty of conventional drama, full of “dead time” and unmarked time shifts, and deeply somber. Which is to say that they belong to the broader tradition of postwar European art cinema, its norms given fresh realization through echoes of Greek mythology and a signature style of exceptional rigor.

Stasis and sublimity

Alexander the Great (1981).

At the level of technique Angelopoulos again emerges as a synthesizer. An admirer of Mizoguchi and Antonioni, and again probably influenced by Jancsó, he became identified with the long take. From The Traveling Players on, scenes are presented in very few shots, often only a single one. Three films of the tetralogy contain between 125 and 150 shots, while The Hunters makes do with 49. And most of the films are very long (two nearly four hours), so the average shot length runs from 72 seconds (Days of ’36) to 206 seconds (The Hunters). As the later films became more accessible, the editing paced quickened only a little: no film has more than a hundred shots, and in all the average shot runs between fifty seconds and two minutes. Add together all the shots in Angelopoulos’ thirteen features and you have less than a third of the shots in, say, Scott’s Enemy of the State.

Most long-take filmmakers scale their framings to human activity; think of Ophuls and Renoir, capturing gestures and reactions as time flows through the image. But Angelopoulos combined the long take with the long shot, putting landscape at the center of his work. The stunning shot I’ve excerpted from The Red and the White above isn’t wholly typical of Jancsó’s films, which tend to have many close framings and to save vast views for climactic moments. By contrast, Angelopoulos makes very distant shots his default mode for exteriors, even for moments of high drama: a conversation in The Hunters, a death in Alexander the Great.

There are very few conventional close-ups in his films, and mid-shots are often forced on him by fully-built interiors, either locations or sets, as in the frame below from The Weeping Meadow. Even then, the camera often keeps its distance, subordinating characters to impersonal architecture and making their encounters seem fragile (The Suspended Step of the Stork).

Sometimes the tableau that results has considerable depth, as with groups gathered in interiors (The Hunters, below). More pointedly, a horrifying scene in Landscape in the Mist almost cruelly forces our eye back into the distance. In each shot, the most important action is furthest from the camera.

At other moments the long shot yields what I’ve called planimetric images. There’s still a fair amount of depth, but the shot is framed perpendicular to a back plane and figures are spread out in strips or layers. Some images earlier in today’s entry afford examples, particularly the developing street confrontation in Ulysses’ Gaze. The Weeping Meadow shows that this principle can be applied to a raft and rowboats too.

Like Scott, Angelopoulos relies on very long lenses, but he holds the shot so that the flattening effect of the lens creates a gradually changing pattern.

Both depth framings and planimetric ones were exploited by European filmmakers of the late 1960s and early 1970s, but Angelopoulos focused rigorously on them and joined them with consistently distant camera positions. As the dramaturgy downplays individual psychology, the shot scale makes individuals figures in a landscape. The result is often a rhythmic organization of the frame, a pattern of symmetries and abstract geometries (Traveling Players, The Dust of Time).

In the later films, moments of personal drama are played out in no less opaque distant shots. In Voyage to Cythera, the exile’s wife goes to their old cottage and coaxes him out. They must be exchanging a look of understanding, but only on the big screen is it visible.

Such fixed shots are riveting enough, but how can the filmmaker dynamize them and prepare for them? The answer for Angelopoulos was keeping the frame mobile. He refuses the giddy sweep and beguiling tempo of Jancsó. Angelopoulos is severe. Like Scott, he will use the zoom, but his enlargements or de-enlargements are stately, not staccato. (Again, that Red and the White shot may have been an early model for him.) In all, his mobile framings are as austere as the color palettes (earth and metal tones) and the lighting (subdued, often chiaroscuro, with usually a drab sky).