Archive for the 'Film technique: Widescreen' Category

Bond vs. Chan: Jackie shows how it’s done

DB here:

During the 1990s several critics began to notice that filmmakers were doing something odd with action scenes.

Directors were consciously, even joyously, sacrificing clarity. When two characters were punching it out, the framing didn’t make it easy to know who was hitting whom, and how. Changes in angle and shot scale were sometimes so abrupt that you had little time to adjust. The cutting pace was so quick that you couldn’t entirely register the movement in shot A before shot B replaced it. Sometimes the spatial layout of the fight was confusing as well: too many close views, too few master shots. Later, the return of handheld shooting made many action scenes even more illegible, blurring and smearing them to the point that sound (as in the Bourne films) had to specify that a body has hit a window or a hand has busted a bottle. Now we have Sylvester Stallone’s The Expendables, which might be a new summit in overbusy, incoherent, inconsequential action.

I wrote about this trend back in the 1990s, and I’ve returned to it on occasion since. Other writers, notably Todd McCarthy of Variety, noticed it too. He referred to the full-throttle editing and “frequently incoherent staging” on display in Armageddon (1998): “Bay’s visual presentation is so frantic and chaotic that one often can’t tell which ship or characters are being shown, or where things are in relation to one another.”

A decade later comes Peter DeBruge’s review of the “muddled execution” of The Expendables: Staging simultaneous fights “might’ve worked had the editors assembled all that footage in such a way that we could tell where characters are in relation to one another or what’s going on.”

The Michael Bay approach has become the principal way in which action scenes are shot. It isn’t absence of craft that leads to these aimless bouts. The filmmakers actively want the action to be hard, even impossible, to follow. Sometimes I think that this blurred bustle is there to secure a PG-13 rating; if you could really see the mayhem, we might be moving toward an R. But filmmakers don’t say that they’re self-censoring. They seem to think that making the action illegible is creative because it promotes realism.

Stallone explains why he scrambled up the fight scenes in The Expendables.

I don’t think many action scenes are shown from the character’s point of view. They are more from the director’s point of view. On Rambo, I thought the most economical and original way to shoot [the action] would be through Rambo’s eyes—if he were directing, what would his style be? But The Expendables is an ensemble picture, so it’s somewhat of a blend. I thought, ‘This is not supposed to hang in the Louvre.’ I wanted it to be disjointed and rough, not choreographed. If you really were filming a big battle with five cameras, [their footage] would not all flow together, so we set up the [cameras] to film the action we’d scripted and told the operators they were on their own. We said, ‘Do the best you can, and we’ll use the interesting shots from the characters’ perspectives.’”

Camera operator Vern Nobles describes shooting the action as “multi-camera craziness.”

You might point out that if somebody were really filming a big fight with five cameras, at least a couple of camera operators would be shot or punched silly. And presumably a few times we’d actually see other cameras.

Realism, as usual, is simply a fig leaf for doing what you want. Virtually any technique can be justified as realistic according to some conception of what’s important in the scene. If you shoot the action cogently, with all the moves evident, that’s realistic because it shows you what’s “really” happening. If you shoot it awkwardly, that presentation is “realistically” reflecting what a participant perceives or feels. If you shoot it as “chaos” (another description that Nobles applies to the Expendables action scenes)—well, action feels chaotic when you’re in it, right?

Forget the realist alibi. What do you want your sequence to do to the viewer? Do you want it to pass along an impression of bustle and flurry? Or do you want to make the viewer wince, recoil, even mildly reenact the movements of the players? Then follow the Hong Kong tradition. Yuen Woo-ping once told me that his goal was to make the viewer “feel the blow.” To convey the effort and strain, the impact and pain: that’s something worth doing.

It’s something that the blur-o-vision tussles lack, but even fights that are more carefully filmed are strangely unmoving. In Tomorrow Never Dies (1997), there’s a fistfight on a catwalk above a rotary press line. The presentation is more or less spatially unified, but it lacks drive because of certain creative choices. For instance, when Bond punches a security guard, the man simply drops out of the frame.

Where does he go? He doesn’t fall off the catwalk but seems to grab the railing, so maybe he’ll return for another go-round. But he doesn’t. As Bond falls back, another guard sneaks up on him. The framing and screen direction suggest that he’s approaching Bond from the front.

Actually, he’s sneaking up from the rear.

When Bond turns, we don’t see his punch.

In fact, we don’t see much of anything. Although the attacker is erect in one shot, he seems to be kneeling in the next, when Bond kicks him, somewhere below the frameline.

The attacker is standing again in the next shot, and he’s flung backward by the force of Bond’s unseen kick.

When the man returns, he tries to tackle Bond. At least, I think he does. The maneuver takes place, again, underneath the frameline.

At last we get a wider shot, but this serves mainly to align the fight with the conveyor belt below the men; guess who will fall?

More fighting, with punches and grappling blocked by the men’s bodies, culminates in Bond’s adversary falling into the print run.

Even here, however, we don’t really see what happens to the victim. He plunges through the river of newsprint and the machine starts belching.

Overall, we get a mild impression of what happened in the fight, but the action unfolds vaguely and is hardly stirring. Is this how you earn a PG-13?

The Hong Kong way

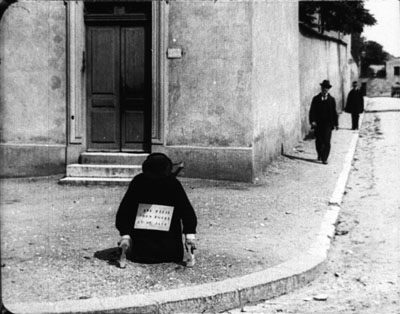

Righting Wrongs (1986).

While revising Planet Hong Kong for its web edition, I’ve been revisiting classic Hong Kong action scenes. In 1997-98, when the book was written, I had to rely on laserdiscs, but since then I’ve been able to look at more 35mm prints. (DVDs usually don’t help answer the sort of questions I’m asking, for reasons reviewed here.) Now I have a chance to put some thoughts about these movies online, in this blog and in the upcoming digital update of the book. As a start, here’s a recipe drawn from the best of Hong Kong fury.

First, go for clarity in every way. Not murky earth-toned sets but brightly colored and sharply lit ones; even an alley can dazzle. Put the camera on a tripod; pan if you must, but save your dolly moves for simple emphasis. No handheld.

Second, aim for precision. Stallone’s comments imply that a cameraman captures a preexisting fight, snatching an “interesting” shot here or there. But that’s not the case. Movie action is choreographed and the framing is calibrated to that. The gestures should be legible, favoring crisp and staccato movement, while the image’s composition aims to convey the action cleanly. It’s a pity that the haphazard framing of Stallone and his cameramen have ruined the choreography of Cory Yuen Kwai, Jet Li’s action designer (and a fine director in his own right).

Third, establish a rhythm. This involves not only building the fight. It also involves synchronizing the pace of characters’ movements with that of the cutting. On the whole, the old rule applies: More distant shots should be held longer than closer ones. This doesn’t mean you can’t use fast cutting, only that your fast cutting can be more finely judged when you take shot scale, composition, and speed of movement into account.

Rhythm means sensing a pulse, and for that you need slight pauses. So don’t cut away to something else before a punch or kick is completed. Let the arc of movement, itself perhaps stretched over several shots, come to a point of rest, if only for a couple of frames.

Fourth—and here is where realism is most explicitly abandoned—amplify the expressive qualities of the action. If movement is zigzag or springy or oscillating, stress that. Give emotional qualities not only to facial expressions but also to postures and combat moves. American heroes just grimace while their bodies remain inexpressive, lumpish. The hard guys in The Expendables might as well be made of granite. But in contrast your fighters needn’t wave their arms wildly. Just concentrate energy and emotion in the action. If the hero attacks, let him become as focused as a javelin. If your heroine falls, don’t let her just drop out of frame: Let her land with a thwack, preferably on the spine or neck, and let her body’s recoil send a spasm through the spectator too.

Hong Kong cinema supports Sergei Eisenstein’s belief that expressive human action is “infectious.” He thought that if physical action onscreen is imbued with vivid force it can arouse sympathetic echoes in the spectator’s own body. After a great action scene, such as in many Chang Cheh and Lau Kar-leung films of the 1970s, or in Yuen Kwai’s Righting Wrongs, when a tough guy gets a spittoon in the face, the viewer feels trembling and tired, but in a good way.

Glass story

Jackie Chan has become such a beaming, easygoing star that we forget that he was an excellent director of brutal fight scenes. He proved adept at filling anamorphic compositions with dynamic movement, as well as plucking out items of a set and sweeping them into the action. (See the parlor fight in Young Master, 1980, or the shenanigans in the rope factory in Miracles/ Mr. Canton and Lady Rose, 1989). In Police Story (1985), Jackie is trying to rescue Salina and save all the computer records in her briefcase. Koo’s gang is determined to stop him. The fight moves through different areas of a shopping mall.

In each of these locales, Jackie plays a suite of variations on what you can do with escalators, staircases, and, most memorably, glass. I can’t do justice to all the skirmishes, but consider some instances of how he stages and cuts the action for an impact that American movies seldom achieve.

The variations get steadily more elaborate. Early in the sequence, Jackie flings one thug, achingly, across the bottom handrails of an escalator.

The shot could hardly be more legible. You see everything. Next, Jackie is grabbed from the rear.

Naturally he has to flip his attacker down to the floor below, rendered in two dynamic shots from directly below and above.

Interestingly, the shots are so clearly composed (even with the fancy mirror effect in the second) that they can be very brief: 26 frames and 16 frames. Down at the bottom, the unfortunate fellow smashes through a display and lands straight on his spine. Unlike the security guards in Tomorrow Never Dies, this thug gets a little commiseration as he rolls over groaning. As in any fight sequences, disposable thugs may come back into action, but at least we’ll clearly see the fates of those who are put permanently out of commission.

After this burst of action Jackie provides a pause as he abruptly looks up in search of Salina.

What else can you do with escalators? How about tossing the next thug down the slim gap between two of them?

In a nice touch, we hear a long squeak as he slides down the trough.

Tomorrow Never Dies sets up its conveyor-belt climax straightforwardly, but Jackie’s choreography is more surprising. Audacious and imaginative as the stunts are, however, they are framed and cut in a way that makes the action clear and precise. Through cinematic choices Chan builds up an infectious arousal. This stuff hurts.

After a set-to in a hallway, Jackie pursues the gang into an area filled with display cases. He takes on the men ferociously, and sets them smashing through the vitrines in another string of variations. Jackie slams down a mirror on one thug, swings another into a display, and sends one spinning through a window. Each shot, of course, is of diagrammatic simplicity, all the better to amplify the expressive dimension and key up the viewer. You can’t watch shots of men hurled into layers of glass without feeling a few palpitations.

Nearly every shot is bound tightly to the next. What will occupy shot B is launched on the fringes of shot A, sometimes for only a few frames. The string of matches on action creates a fluid continuity quite different from the choppiness we often find in American sequences.

A good instance occurs after Jackie has been pinned under a toppled shelf. In a medium close-up, the gang leader orders his thug into action; behind him the plaid-coated thug moves left.

In long shot, with Jackie at a disadvantage, the thug continues his movement in the background as he grabs a heavy statuette.

In a medium-shot, Mr. Plaid Jacket lifts the statue, but as he moves aside he reveals Salina rushing toward him in the background. Look quick: She appears in the fifteenth frame, and is gone within another fifteen.

We can only glimpse Salina passing behind the thug, but the next shot shows her clearly: running, baseball bat in hand, toward him. The trajectory could not be clearer, and she swings the bat directly through the vitrine.

The force of the action is multiplied by the simplest cut possible: an axial enlargement, with the action slightly repeated and slowed. The first shot of Salina’s swing lasts seventeen frames, the second exactly twice as long. The arithmetic of the cutting extends the action’s beat.

Bursts of glass form the dominant, painful motif of this part of the sequence. (Jackie’s crew suggested he call the film Glass Story.) The shifting dynamic of the fight is rendered through close encounters of the splintery kind. But these are differentiated. Long shots portray the torments of the gang, but Jackie’s first encounter with glass is treated in one simple close shot, just a second long, that usually makes audiences flinch.

Jackie is attacked by the gang leader and he shoves Salina out of the way.

The leader springs forward to whack Jackie with the briefcase.

Cut to the opposite angle, a tight shot of Jackie.

The briefcase continues to be swung, and Jackie’s head smashes the windowpane.

Jackie bounces off the glass and grimaces in agony.

The proximity of the glass shards to his eyes probably triggers some primal revulsion in us, but this is only part of the image’s force. The whole shot lasts only 28 frames. I think that part of its percussive impact comes from the fact that at the start we don’t have time to register that the pane is there. (There are only seven frames before Jackie hits.) When the glass bursts, it’s as startling as if the screen surface has cracked as well, and this amplifies the painful impact of the blow.

For a time Jackie is at the gang’s mercy. But he makes a comeback, and eventually in a kind of summary of his other maneuvers he will bash the leader, body and head, through two glass cases. This phase of the scene concludes with Jackie running Mr. Plaid through a series of cases at the point of a motorcycle. Both crescendos are filmed in clear, smoothly-cut shots—and long shots at that.

We may wince for the fate of these gangsters, but we shuddered when we saw Jackie’s face knocked through a window. Soon Jackie will be flipping the leader down an escalator, a sort of envoi to the scene’s first phase, and he will be sliding down a three-story light pole to catch up with boss Koo himself.

To use Stallone’s comparison, I’d happily hang this splendid sequence in the Louvre.

But what sort of MPAA rating would it receive today? The painful physicality on display is given a staccato force through the framing and cutting. And don’t call it cartoonish. It’s Bond who’s cartoonish, with his unflappable ease and perfectly functioning gadgets and defiance of the laws of gravity and those fights he wins without suffering a scratch. Jackie shows us the sweat. He and his victims fall with painful awkwardness, he gets gashed and bruised, and he’s all too vulnerable to physics (or at least Hong Kong physics). Bond wins through debonair resourcefulness and a lot of luck. Jackie wins by refusing to lose.

He refuses to lose the audience too. In Police Story Jackie’s manic urge to make the scene maximally gripping is itself a little scary. Nonetheless, when a director isn’t afraid of tapping the real power of movies, a fight scene can give us an adrenalin transfusion. Who needs 3-D? Maybe only weak directors.

For other discussions of Hong Kong action scenes, see my “Aesthetics in Action: Kung-Fu, Gunplay, and Cinematic Expression” and “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse” in Poetics of Cinema. There are some other examples in my online essay on Shaw Brothers. My most ambitious efforts in this direction are in Planet Hong Kong, where I take up the issue of rhythm in more detail than I can here. Alas, many contemporary Hong Kong action scenes have learned bad habits from Hollywood. I’ll talk about the decline of crisp fight staging in the new edition of PHK, due online in early December.

Todd McCarthy’s 1998 review of Armageddon is here. Peter DeBruge’s review of The Expendables is here. Both may lurk behind a paywall. The coverage of The Expendables I mention is Michael Goldman, “War Horses,” American Cinematographer 91, 9 (November 2010), 52-56. The pilot online issue is here.

The Dragon Dynasty version of Police Story includes Bey Logan’s conversation with Brett Ratner. During the commentary, Ratner notes that Jackie holds his shots longer than would an American director, who would be likely to cut on every punch. Incidentally, I’ve found many DD releases of Hong Kong films to be superior in quality to other DVD versions, and Logan’s commentaries are information-packed. His book Hong Kong Action Cinema remains a fine piece of work.

The images from Tomorrow Never Dies are taken from DVD, with all the drawbacks of that format for close analysis. But I don’t think my conclusions would vary if I worked from 35mm. The Police Story frames are analog frame enlargements from a 35mm print and allow accurate frame-by-frame analysis. Even then, Jackie’s pacing is so fast that blurring is inevitable. Thanks to Heather Heckman for her assistance in turning my slides into digital files.

PS 17 September 2010: I forgot to mention that Matt Zoller Seitz has provided two of the most discerning (and hilarious) critiques of the Michael Bay High Rococo Action Style, here and here.

Young Master.

The Cross

The Puffy Chair (2005).

Mark: [The actors] need to improvise. They need to find the moments, and we don’t let them lean on the script too much. We want them to try to reinvent some of the dialogue and make it fresh.

Jay: We don’t do any blocking. Our whole goal is just to set up a room and basically foster an interaction that we feel is interesting and real.

Mark: And spontaneous.

Jay: And spontaneous.

Jay and Mark Duplass, talking of their new film Cyrus.

DB here:

We don’t do any blocking. Dude, we noticed. In The Puffy Chair, the Duplass brothers typically settle the actors into one spot and pan or cut between them.

Seldom do the characters move around the setting. When they do, it’s usually by means of a walk-and-talk traveling shot that transitions to the next static layout of actors.

We are talking about filmmakers who refuse the challenge of staging.

At the other extreme of budget and commercial clout, consider another film by two brothers. In The Matrix Reloaded, Neo meets the Oracle in the virtual courtyard and sits on a bench with her.

The whole scene, which runs nearly seven minutes, contains 94 remarkably static shots. After Neo settles on the bench beside her, we get simple reverse shots—lots of them, mostly one per line of dialogue. The setups are maniacally repeated. There are thirty-one iterations of the first framing below and eighteen of the second.

The only variation is a slightly tighter framing on each character, creating another brace of single setups during Neo’s acknowledgement of his dream of Trinity’s death. Each of these gets nine iterations.

Sustained two-shots would have let the actors do more with their upper bodies, but in this string of singles, faces and dialogue have to present Neo’s reactions to his new mission to save Zion. Granted, there are seven shots showing both Neo and the Oracle in the same frame, but these are very brief and seem to be there simply to provide beats and add some variety to the load of exposition the scene must carry.

Breaking the scene up so much has interesting rhythmic implications. Paradoxically, our movies are cut very fast but they feel rather slow (and run very long). When we need a cut to see a character’s reaction, a scene plays out more slowly than if the characters were held in the same frame for a significant period. Then we might see Neo’s reactions while the Oracle is speaking, rather than having to wait for them afterward.

But my main point is that the actors are planted in one spot. Like the Duplasses, the Wachowski brothers have felt no need to imagine the characters’ interaction through blocking. Indeed, when shooting a conversation, most of today’s filmmakers seem happiest if the actors stay riveted in place—standing, seated, riding in a car, typing at a computer terminal. Improvised cinema or storyboard cinema: Both camps are refusing the challenge of staging.

In some books and some web entries (most recently, here and here and here and here), I’ve tried to trace the rich tradition of ensemble staging. From almost the start of cinema, filmmakers have explored creative ways of moving actors around the set, aiming at both engaging storytelling and pictorial impact. Since the 1960s, on the whole, this tradition has been waning. Now, I fear, it has nearly disappeared.

I’m not going to reiterate those earlier arguments. Instead I want to talk about one simple staging tactic that directors almost never employ today. I offer it at no cost to young directors. Try it! You might get a taste for a range of cinematic expression that is nowadays neglected.

Cross and double cross

Assume you have two characters in a set. At a crucial moment, you invent some business that lets them exchange places, so that the one on the left winds up on the right, and vice-versa. At a minimum, this gives you visual variety; it keeps the viewer’s attention engaged by refreshing the composition. It can of course also heighten dramatic impact.

Naturally, we expect to find the Cross in the first golden age of cinematic staging, the 1910s. Here’s a case that combines the cross with depth staging, from the Doug Fairbanks picture The Matrimaniac (1916).

Marna and the Court officer have switched places in the frame. Note especially that her movement to the right, clearing our view of the officer at the door, is motivated by her hesitation at following him. Actually such moments probably don’t need much motivation; the flow of the action is so quick that no viewer will ask why she moved to the right, since our attention is on what her action reveals.

One way to motivate the Cross is to have A turn sharply away from B but keep talking. This is a bit of actor’s business that seems far more common in the classical era of moviemaking. Here is an excerpt from a single-shot scene in Budd Boetticher’s The Tall T (1957). Brennan tries to console Mrs. Mrs. Mims, who has realized that her husband betrayed her. He enters the shack and then walks past her, as if considering exactly how to calm her.

This has been the prelude to a more intense confrontation. She comes closer to the camera, and Brennan joins her, forcing her to look at him as he says they must concentrate on staying alive.

In Demy’s Lola (1961) the Cross is motivated by the urge to offer another emphatic view of the protagonist. Roland has been talking to the two mother-figures who run the café he frequents. He’s dragging himself off to work as Jeanne fetches her radio from the bar and goes into the back room. We get two Crosses.

The shot’s climax comes when Roland pauses in the foreground and says: “One day I’ll go away too.” Again, a key character is turned from the other but continues to speak.

No need to cut in to a close-up because Roland’s face is perfectly visible. Just as important, while his face shows a certain reverie, his nervousness is conveyed by the way he waggles the novel in his hand. The actor is given a chance to act, not just with line reading and facial expression but with his slumped posture and his arms—one casual, the other in anxious motion. Taken together, the body and the face present Roland’s confusion.

Crossfire

Don Siegel’s The Big Steal (1949) yields many offhand instances of the Cross, indicating how taken for granted the technique was in studio films. When the slippery Fiske invites Joan in, she comes to the left foreground and he moves to the right side of the frame to shut the door.

Approaching her by stepping into medium shot, he tries to warm her up, but she slaps him. Cut in to underscore her reaction. “What did you expect—kisses?”

In a return to the earlier setup, she turns away and executes another Cross, settling on the sofa.

Simple and concise; some would say banal. But compared to The Puffy Chair and The Matrix Reloaded, it looks brisk. The characters move easily through the frame without camera arabesques, and the medium shot is saved for the slap. The single of Joan adds another spike to the drama. Close-ups no longer rule but are used for momentary emphasis.

So the Cross can be sustained by cutting and camera movement. In The Lady Is Willing, Liza has found a baby and called a pediatrician. Director Mitchell Leisen gives us an over-the-shoulder shot of her and at the close of it she walks around Dr. McBain’s arm, with her feathery hat brushing his face.

If the shot were sustained with a pan, we’d have a Cross, but instead there’s a cut to Liza continuing the movement. McBain turns to watch her.

He starts to follow her diagonally. When she pauses to face him, the Cross is completed.

They leave the room. After a cutaway shot showing Liza’s secretary, the camera pans to follow McBain into depth washing his hands. When he comes through the door past Liza, we get another Cross.

With positions switched, the camera travels with her as she catches up with him in a medium shot. He is opening his medical bag.

This pause enables Leisen to underscore a key line of dialogue. “I detest children of all ages. I detest infants particularly.”

One more Cross and the shot is done. The camera pans again to follow McBain bending over the child, and Liza slips into the shot behind him, remonstrating with him. “A man who dislikes children simply can’t be a baby specialist.”

As so often, the Cross is used to present one character turning from another, or one trying to catch up with another who for dramatic reasons plows ahead. And the Cross favors a moderate depth, not the eye-smiting foregrounds of Welles but something less aggressive. In these ways, the simple device can participate in a broader pattern of fluid craftsmanship. The action can unfold in a clean rhythm, consistent with what Charles Barr calls “gradation of emphasis.” Story points arise smoothly out of the flow of behavior. Actors get a chance to use their whole bodies, to create character through posture or stance, or even the angle of the elbows. Imagine if Dietrich, in the left shot just above, had sauntered to McBain with her hand on her hip as she does in so many other movies; the scene would take on a different tint.

When thinking about staging, we usually invoke Renoir or Ophuls or Jancsó, directors who integrate complex choreography with complicated tracking shots. (They also use the Cross a lot.) My examples try to show that even simple camerawork can enhance the performers’ grace. Nor do they have to execute the calisthenics on display in the office scenes of His Girl Friday. The modest moves we see in The Big Steal and The Lady Is Willing are within the grasp of eager filmmakers and game actors.

Cross purposes

I don’t have a good explanation for why such simple staging tactics have gone out of fashion. It’s too easy to cite laziness or lack of imagination, though they may play a role. I wonder as well if complicated staging is much taught in film schools. More specifically, improvisational methods may actually inhibit creative blocking. An actor who’s winging it may be reluctant to shift around the set, for fear that this creates new problems for framing or lighting or the other performances. Better, the actor may think, to concentrate on line readings, expressions, and other things that she can control while staying rooted to the spot. And maybe our directors don’t want to work their actors too hard, especially when the actors are beginners or nonprofessionals, as we find in indie filmmaking. Yet some masters of supple, intricate staging, such as Hou Hsiao-hsien, employ untrained performers.

Contemporary directors may have a more principled objection to the older staging style: It’s too artificial. In real life, people mostly chat with each other when they’re sitting down, or walking, or riding in a car. Static staging, some might say, captures the passive nature of everyday interactions.

But dramatic narrative typically doesn’t consist of ordinary life. A film offers heightened, focused, pointed encounters, shot through with meaning and feeling. The actors and the filmmaker have a chance to sharpen the viewer’s perception of the situation and pass along the moment-by-moment play of thought, emotion, and action. There are both loud and quiet ways of doing this. Antonioni’s famously “dedramatized” scenes are staged as dynamically as the more florid moments of Visconti or Fellini. Emotionally subdued action can be shaped just as precisely as passionate outbursts, and it can carry its own impact.

I should make it clear that I’m not asking anybody to embrace a single style. Sometimes stand-and-deliver and intensified continuity editing work very well. Directors will always seek specific solutions to the problems of a scene. But I don’t see much variety in the solutions many people now pursue. I don’t see evidence that most young filmmakers around the world are aware that traditions furnish lots of alternatives.

In earlier periods, some directors were as editing-oriented as today’s mainstream ones, while other directors adopted more staging-driven approaches. But either sort had a broader palette than what we see today. Any accomplished director could stage a conversation in a variety of ways. Just to take Demy, some scenes in Lola are handled in full shots like the one highlighting Roland in the café. Other scenes are broken up into tight singles, and still others are treated in two-shots.

All the classical films I’ve mentioned are pluralistic in their technical choices. Today, though, we see more uniformity, or rather conformity.

Cinephile conversation on the internet is currently rippling around a controversy about “slow cinema.” Whatever that rough category covers, it surely includes those festival films that put the camera in one spot per scene and simply observe. I’d argue that many of these minimalist movies are also AWOL when it comes to staging. After watching a long-take, flatly shot film with me, a Hong Kong filmmaker friend remarked, “This sort of thing is just too easy.” One difference between a solid “slow film” and an empty one, I suspect, lies in the extent to which the filmmakers explore the resources of staging. How do we know? We have to analyze the films. (More on this matter here.) Absent that analysis, critics’ appeals to realism or meditative restfulness or “time flowing through the shot” risk becoming alibis for inert moviemaking.

Many young directors want to be innovative. They want to shake things up. This is a good impulse. The way things are going, the ambitious way forward is obvious: Go backward. Avoid stand-and-deliver. Avoid walk-and-talk. Get your actors on their feet and move them around the setting. Invent bits of business that let them crisscross the frame, laterally and in depth. Dynamize all areas of the shot. In the process you may discover new dimensions of creativity.

The Cross is only one tactic, but I think it’s useful as a way to sensitize ourselves to staging. The best way to understand staging is to watch, really watch, a lot of classic cinema from Hollywood and elsewhere. When you’re ready for the hard stuff, Mizoguchi is waiting.

I expect disagreements with my criticisms of contemporary film technique, so I hope skeptics will consider my more extensive arguments in On the History of Film Style, Figures Traced in Light, and The Way Hollywood Tells It.

I haven’t found references to what I call the Cross in manuals of direction. The closest technique, and the one that called my attention to the possibilities of the technique, is what Mike Crisp in his valuable book The Practical Director (first ed., 1993) calls the “rise and cross.” This refers to actors getting up from sit-down conversations in one spot and moving to another sit-down area, while switching position in the frame. I’ve expanded the idea to cover a broader variety of situations.

As far as I can tell, my term doesn’t have much in common with the stage direction “Cross,” which you’ll find in play scripts. Janie Jones provides definitions here. While staging in film is in many respects different from that in theatre, I think that moviemakers can find intriguing practical ideas in Terry John Converse, Directing for the Stage.

Alicia Van Couvering’s interview with the Duplass brothers, “Don’t you want me?”, is published in Filmmaker 18, 3 (Spring 2010; not yet available online); my quotation is from p. 43. In his essay Slow Cinema Backlash, Vadim Rizov argues that lesser attempts at “slow cinema” have led to a somewhat predictable style.

Raining in the Mountain (King Hu, 1979).

Sitting under a palm tree made of film

Jerusalema.

Kristin here–

The Palm Springs International Film Festival has a logo calculated to appeal to those of us who travel from snowy northern climes to attend: a palm tree composed of strips of film. As each film began and a short prologue listed the sponsors, I studied that logo and felt grateful that I was missing the frigid weather that descended upon Madison during our absence. It’s a clever design, also managing to suggest movies springing forth in abundance, which was certainly true of the festival’s offerings.

The Palm Springs International Film Festival has a logo calculated to appeal to those of us who travel from snowy northern climes to attend: a palm tree composed of strips of film. As each film began and a short prologue listed the sponsors, I studied that logo and felt grateful that I was missing the frigid weather that descended upon Madison during our absence. It’s a clever design, also managing to suggest movies springing forth in abundance, which was certainly true of the festival’s offerings.

Two from the Antipodes

Most New Zealand films are set in their home country, taking advantage of its magnificent landscapes and local culture. Dean Spanley (Toa Fraser) strikes me as quite different. Based on a Lord Dunsany fantasy novella, My Talks with Dean Spanley (1936), it was mostly filmed in England and is a costume piece set in the Edwardian era. Five years ago co-productions were rare things in New Zealand, but this is a Kiwi-U.K. film with an impressive international cast. There are Englishman Jeremy Northam as the narrator and protagonist, New Zealander Sam Neill in the title role, Australian Bryan Brown (perhaps most widely known as Breaker Morant) in a supporting part, and Peter O’Toole. The latter is spoken of as a possible best supporting actor Oscar nominee, though I fear that the film is too low profile for that.

[Correction, January 26. Bryan Brown appears in Breaker Morant as Lt. Peter Handcock, not in the title role.]

Dean Spanley is a feather-light but well-told tale of Fisk, a middle-aged man who pays a tense visit to his  curmudgeon of a father (played by O’Toole) once a week. For something to do, Fisk takes the old man to a lecture on reincarnation, also attended incongruously by the local preacher, Dean Spanley. A friendship develops between Fisk and Spanley as it gradually comes out that Spanley seems to be the reincarnation of the father’s beloved childhood dog. The premise is made plausible by a gradual revelation of the premise, by Neill’s performance, and by some lyrical flashbacks. The whole thing is a surprising film to have come from Fraser, whose first feature, No. 2, was set in Auckland and concerned a family of Fijian descent. Yet it seems a sign of the New Zealand cinema’s health that he could take such an unexpected turn and tackle an English literary adaptation.

curmudgeon of a father (played by O’Toole) once a week. For something to do, Fisk takes the old man to a lecture on reincarnation, also attended incongruously by the local preacher, Dean Spanley. A friendship develops between Fisk and Spanley as it gradually comes out that Spanley seems to be the reincarnation of the father’s beloved childhood dog. The premise is made plausible by a gradual revelation of the premise, by Neill’s performance, and by some lyrical flashbacks. The whole thing is a surprising film to have come from Fraser, whose first feature, No. 2, was set in Auckland and concerned a family of Fijian descent. Yet it seems a sign of the New Zealand cinema’s health that he could take such an unexpected turn and tackle an English literary adaptation.

Australian movieThe Black Balloon (Elissa Down) is a contemporary story set in a Sydney suburb. It’s a social-problem film, dealing with a teenage boy, Thomas, torn between his love for his severely autistic brother (a truly remarkable performance by Luke Ford) and his frustration at the effect the brother’s antics have on his own ability to fit in at his new school. The film is apparently aimed primarily at a teen audience (it won the Crystal Bear for “Generation 14plus – Best Feature Film” at the Berlin Film Festival), but the almost exclusively adult audience at Palm Springs seemed entertained and touched by it. Australian stars who have made careers abroad often return to support their native industry by acting in local films, and Toni Collette is impressive as the mother. I found it a bit of a stretch that the one sympathetic, understanding fellow student Thomas finds happens to be a gorgeous girl who also seems to have no friends among their classmates. Apart from that, it’s an entertaining and informative film.

It does have one intriguing device in the pre-credits and credits scenes: several objects in each shot contain superimposed words identifying a number of the objects visible. The idea presumably is to suggest the fact that autistic people have excellent object recognition but difficulty understanding others’ emotions. I would have liked for the labeling to continue through the film, but I suspect most other viewers wouldn’t. Admittedly that would have distracted viewers from the narrative–unless we soon got used to it, which I suspect would have happened. At any rate, it’s a catchy way to introduce the story.

Another Exodus

Watching the Moroccan film Goodbye Mothers (Mohamed Ismail) was a disconcerting experience. At first it struck me as simply old-fashioned filmmaking, with multiple plotlines concerning three Jewish families living in Morocco at a time of increasing racial tensions. The stories are the stuff of melodrama, with a beautiful Jewish girl in love with a Moroccan man, a man debating whether to abandon his long-time friend and business partner to move his family to Israel, and the partner’s childless wife, who would be devastated by the departure of the family’s children, to whom she has been a second mother. In this age of short scenes, the film bases its action largely on extended shot/reverse-shot conversations, without much moving camera or many tight close-ups.

Eventually I realized that the film looks very much as if it had been made around 1960, which is the period of the story’s action.

The similarity can’t be coincidental. As with other Moroccan films I have seen, there is considerable emphasis on the music track, and here two or three scenes use the sweeping theme from Preminger’s Exodus. Indeed, the style is occasionally reminiscent of Preminger’s work of that era, as in shots that position characters precisely across the wide screen.

There’s also the sort of depth composition with a head prominent in the foreground that one associates with widescreen 1960s films by Nicholas Ray:

There’s more cutting than Preminger would typically use, but it’s an interesting pastiche that lends some subtle overtones to the film’s action. Despite a wide range of performance styles and a somewhat schematic set of plotlines, the film is an intriguing attempt to use a throwback style to convey the period when the peaceful co-existence of Jews and Muslims in Morocco was breaking down.

The quest film grows up

A few films do not necessarily a pattern make, but I’ve been struck by some echoes among the Middle Eastern films I’ve seen at this and other festivals. When the New Iranian Cinema came to international notice in the 1980s and 1990s, one narrative premise that several films shared led them to be labeled “child quest” movies. These tended to be simple searches or journeys: a boy trying to return his friend’s school notebook (Kiarostami’s Where Is My Friend’s Home?, 1987) or a girl trying to make her way through traffic to get home after school (Panahi’s The Mirror, 1997).

Gradually disasters, natural and manmade, caused the quests to become more serious. They often still involved children, but the just as often the seekers have been adults. Kiarostami’s And Life Goes On (1991) dealt with a film director’s journey into an earthquake-devastated area to find the child actor of Where Is My Friend’s Home?, who happened to live in the worst-hit area.

More recently, though, the disasters that create quests are wars in the region. My Marlon and Brando, the first feature of Turkish director Huseyin Karabey, deals with a actress in Istanbul. She has fallen in love  with an Iraqi Kurd, and when the U.S. launches its invasion of Iraq, the two are cut off from each other. Increasingly frustrated and desperate, the heroine sets out to join her lover in his home in northern Iraq, even though the convoluted set of border closings forces her to go by bus via Iran.

with an Iraqi Kurd, and when the U.S. launches its invasion of Iraq, the two are cut off from each other. Increasingly frustrated and desperate, the heroine sets out to join her lover in his home in northern Iraq, even though the convoluted set of border closings forces her to go by bus via Iran.

As she meets obstacle after obstacle and finds herself isolated in small villages where she cannot speak the local language, the film risks becoming monotonous. But audience attention is carried in part by a remarkable performance by Ayca Damgaci, who must carry every scene. At intervals we see videotaped messages sent to her by her lover. His effusive professions of love are juxtaposed with clips from the film where they had acted together, and these messages lead one to wonder just how sincere he is. Might he be leading her on through her grueling trek just to find disappointment?

My Marlon and Brando reminded me of Under the Bombs, which I wrote about from the Vancouver Film Festival. (It was also shown at Palm Springs.) There a distraught Lebanese woman travels by cab into the southern area bombed by Israel in 2006, seeking her son. Both films stress the difficulties of ordinary people’s making their way through combat areas or having to detour around them.

Another variant comes in Ramchandi Pakistani (2008), made by Mehreen Jabbar, one of several female  directors who have emerged in the Middle East. The mischievous Pakistani child Ramchandi wanders away from his village in Pakistan. He accidentally crosses the border into India—a border marks only by rows of painted white stones, giving the child no indication of the danger he faces. His father follows in an attempt to find him, and both are thrown into an Indian prison for years, their unregistered status making release highly unlikely. The film then alternates between the plight of the pair and their fellow prisoners and the frantic efforts of Ramchandi’s mother to find out what has happened to them and to eke out a living while hoping for their return.

directors who have emerged in the Middle East. The mischievous Pakistani child Ramchandi wanders away from his village in Pakistan. He accidentally crosses the border into India—a border marks only by rows of painted white stones, giving the child no indication of the danger he faces. His father follows in an attempt to find him, and both are thrown into an Indian prison for years, their unregistered status making release highly unlikely. The film then alternates between the plight of the pair and their fellow prisoners and the frantic efforts of Ramchandi’s mother to find out what has happened to them and to eke out a living while hoping for their return.

The three films deal with different conflicts: U.S.-Iraqi, Israeli-Lebanese, and Indian-Pakistani. All three stress the separations of families and lovers by hostilities and the barriers they arbitrarily create for ordinary people.

A small drama far away

In contrast, the Kazak film Tulpan (Sergei Dvortsevoy) presents flat, limitless, arid plains of southern Kazakstan, where borders and conflicts seem so far away as to be irrelevant. Asa, a veteran of the Russian navy, does not go on a quest but has a pair of local goals. He seeks to marry the elusive Tulpan and to establish his own flock of sheep. As he struggles to achieve  these goals, Asa remains an assistant to his brother-in-law Ondas, a tough, seasoned herdsman who keeps finding his ewes’ newborn lambs mysteriously dead.

these goals, Asa remains an assistant to his brother-in-law Ondas, a tough, seasoned herdsman who keeps finding his ewes’ newborn lambs mysteriously dead.

The film is director Dvortsevoy’s first fiction feature after a career as a documentarist, and he skillfully details the lives of Ondas and his family. There are two remarkable, squirm-inducing scenes of the births of lambs, handled in long takes that seem to make trickery impossible. Despite the hardships and disappointments, there are touches of humor, as when the local vet stops by to investigate the dead-lamb problem, accompanied by a bandaged baby camel in the side-car of his motorcycle and followed by its persistent, annoyed mother. A charming film and a crowd-pleaser.

See the film, avoid the city

During the Q&A after the screening of Jerusalema that I attended, queries from the audience tended to center around how accurate its depictions of rampant crime and violence are. Director Ralph Ziman assured us that they are quite accurate, and indeed the film is loosely based on a combination of true cases. Johannesburg, he claimed, is the world’s most violent city. Whether that’s strictly true, I don’t know, but Ziman’s film is a polished, gripping depiction of one brilliant young student’s rise and fall (and rise?) as a criminal. The script, with its complex flashback structure, is tight and fast-paced. The cinematography is consistently imaginative and beautiful. (See images at top and bottom.) I can best describe it as Michael Mann shooting a gritty Hong Kong action film, but setting it among Johannesburg gangs. The Mann influence is palpable. At one point the characters watch a scene from Heat to learn how to ambush an armored car, and Mann is among those thanked in the credits.

Jerusalema was South Africa’s submission for a nomination as the Best Foreign Film for the Oscars. Not surprisingly, it didn’t make the shortlist, being an action pic rather than the art-house fare that the Academy members favor. Its language is also a disconcerting melange of the tongues and dialects spoken in South Africa, including English. At times characters switch among languages in mid-sentence. According to Ziman, the script was written in English, and then the cast helped work out how their individual characters would speak the lines.

The basic story is familiar, with a teenager, Lucky, from Soweto accepted into a university but unable to pay his fees and intending to turn to crime temporarily to raise the requisite money. Naturally he tries to quit, only to be lured back. But Lucky uses his intelligence to work out a novel way to twist the law to his advantage, commandeering crime-ridden apartment blocks that have been allowed to slip below legal standards and buying them at bargain prices. It’s the dynamic style, though, that makes this so entertaining. It was one of my favorite films of the festival. Ziman announced that it had recently been sold for American distribution, but he would not reveal the name of the company before an official announcement. I’m not sure whether it would fit better into multiplexes or art theaters. Like so many recent films it seems to fall in between. (The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Slumdog Millionaire are only the most recent examples that come to mind.) Its subtitles make it unlikely to find a really wide audience, but its violence might be off-putting to the art-house crowd. Wherever it ends up, it’s worth looking out for.

A final thought

During the festival, I was struck a number of times by how well-made films were that came from countries where production has previously been minimal. From South Africa, Kazakstan, Morocco, and Pakistan we see films that give the impression of having been made within a well-established industry. They adeptly use conventions familiar from festival-aimed art films or from classical Hollywood-style cinema. Clearly filmmakers in such countries have been seeing a lot of movies, even if they haven’t been making very many yet. The cliché about the cinema as an international language, almost as old as the medium itself, apparently remains as true as ever.

Note: Variety‘s wrap-up of the Palm Springs International Film Festival, including the prizes awarded, can be found here.

Gradation of emphasis, starring Glenn Ford

DB here:

Charles Barr’s 1963 essay “CinemaScope: Before and After” has become a classic of English-language film criticism. (1) It proffers a lot of intriguing ideas about widescreen film, but one idea that Barr floated has more general relevance. I’ve found it a useful critical tool, and maybe you will too.

Grading on a curve

Barr called the idea gradation of emphasis. Here’s what he says:

The advantage of Scope [the 2.35:1 ratio] over even the wide screen of Hatari! [shot in 1.85:1] is that it enables complex scenes to be covered even more naturally: detail can be integrated, and therefore perceived, in a still more realistic way. If I had to sum up its implications I would say that it gives a greater range for gradation of emphasis. . . The 1:1.33 screen is too much of an abstraction, compared with the way we normally see things, to admit easily the detail which can only be really effective if it is perceived qua casual detail.

The locus classicus exemplifying this idea comes in River of No Return (1954). When Kay is lifted off the raft, she loses her grip on her wickerwork bag and it’s carried off by the current. (See the frame surmounting this entry.) Kay and her boyfriend Harry are rescued by the farmer Matt. As all three talk in the foreground, the camera catches the bundle drifting off to the right.

Even when the men turn to walk to the cabin, Preminger gives us a chance to see the bundle still drifting downstream, centered in the frame.

The point of this shot, Barr and V. F. Perkins argued, is thematic. As Kay moves from the mining camp to the wilderness, she will lose more and more of her dance-hall trappings and be ready to accept a new life with Matt and Mark. The last shot of the film shows her final traces of her old life cast away.

Cutting in to Kay’s floating bag would have been heavy-handed; if you stress a secondary element too much, it becomes primary. Barr reminds us that any film shot can include the most important information, as well as information of lesser significance. A film can achieve subtle effects by incorporating details in ways that make them subordinate as details and yet noticeable to the viewer. Or at least the alert viewer.

In Poetics of Cinema, I wrote an essay on staging options in early CinemaScope, and Barr’s idea helped me illuminate some of the strategies I discuss. (For earlier comments on Barr on Scope and River of No Return, see my article elsewhere on this site.) Today I want to consider how the notion of gradation of emphasis has a more general usefulness.

Barr contrasts the open, fluid possibilities of CinemaScope with two other stylistic approaches, both found in the squarer 1.33 format. The first approach is the editing-driven one he finds in silent film. This tends to make each shot into a single “word,” and meaning arises only when shots are assembled. Barr associates this approach with Griffith and Eisenstein. The second approach, only alluded to, is that of depth staging and deep-focus shooting, typically associated with sound cinema of the late 1930s and into the 1950s.

Both of these approaches, montage and single-take depth, lack the subtle simplicity of Scope’s gradation of emphasis.

There are innumerable applications of this [technique] (the whole question of significant imagery is affected by it): one quite common one is the scene where two people talk, and a third watches, or just appears in the background unobtrusively—he might be a person who is relevant to the others in some way, or who is affected by what they say, and it is useful for us to be “reminded” of his presence. The simple cutaway shot coarsens the effect by being too obvious a directorial aside (Look who’s watching) and on the smaller [1.33] screen it’s difficult to play off foreground and background within the frame: the detail tends to look too obviously planted. The frame is so closed-in that any detail which is placed there must be deliberate—at some level we both feel this and know it intellectually.

To see Barr’s point, consider a shot like this one from Framed (1947).

The shot, rather typical of 1940s depth staging, displays an almost fussy precision about fitting foreground and background together. That bartender, for instance, stands squeezed into just the right spot. (2) Barr claims that we sense a certain contrivance when primary and secondary centers of interest are jammed into the 1.33 frame like this.

We don’t sense the same contrivance in the widescreen format, he suggests. Barr assumes, I think, that the sheer breadth of any Scope frame will include areas of little consequence, whereas that’s comparatively rare in a 1.33 composition. This is an intriguing hunch, but uninformative patches of the frame may not be intrinsic to the Scope technology. Perhaps the fairly neutral and inexpressive uses of Scope that dominate the early 1950s, the sense of empty and insignificant acreage stretching out on all sides, make us expect that little of importance will be found there. Accordingly, directors can create a sense of discovery when we spot a significant detail in this stretch of real estate.

Anyhow, Barr indicates that if static deep-space staging made the frame too constrained, 1930s and 1940s directors who combined depth with camera movement created more spacious and fluid framings. He suggests that Mizoguchi, Renoir, and others anticipated the possibilities of Scope.

Greater flexibility was achieved long before Scope by certain directors using depth of focus and the moving camera (one of whose main advantages, as Dai Vaughan pointed out in Definition 1, is that it allows points to be made literally “in passing”). Scope as always does not create a new method, it encourages, and refines, an old one (pp. 18-19).

Barr believes that Scope positively encouraged gradation of emphasis, and that widescreen directors of the 1950s and 1960s have made the most fruitful use of the strategy. But he allows directors of all periods utilized gradation of emphasis, even in the standard 1.33 format. This is, I believe, a powerful idea.

Before Scope: Making the grade

Barr’s discussion of silent cinema, relying on notions of editing associated with Griffith and Soviet directors like Eisenstein, is done with a broad brush, but it’s typical of the period in which he was writing. We didn’t know much about silent filmmaking until archivists started to exhume important work in the 1970s. It’s no exaggeration to say that we haven’t really begun to understand the first twenty-five years of cinema until fairly recently.

In a way, the staging-driven tradition of the 1910s, which I’ve often mentioned on this site (here and here and here), exemplifies some things that Barr would approve of. Directors of that period made extraordinary use of the frame and compositional patterning. They staged action laterally, in depth, or both. They let shots ripen slowly or burst with new information. This approach to using the full frame (with only occasionally cut-in elements) has come to be called the tableau style, emphasizing its similarity to composition of a painting—although we shouldn’t forget that these films are moving paintings, and the compositions are constantly changing. The result is that emphasis tends to be modulated and distributed among several points of interest.

Central to this strategy, I think, was camera distance. American directors tended to set the camera moderately close, cutting figures off at the knees or hips, and by taking up more frame space, the foreground actors tended to limit the area available for depth arrangement or for significant detail.

This shot from Thanhouser’s The Cry of the Children (1912) is a rough 1910s equivalent of the crammed shot from Framed above. (See also the tightly composed shots from DeMille’s Kindling (1915) here.)

The European directors, by contrast, tended to let the scene play out in more distant shots, creating spacious framings of a sort that would be reinstituted in early CinemaScope. Consider this shot from Holger-Madsen’s Towards the Light (Mod Lyset, 1919) and another from Island in the Sun (1957).

Both, it seems to me, have the type of open composition and the foreground/ background interplay that Barr praises in his article.

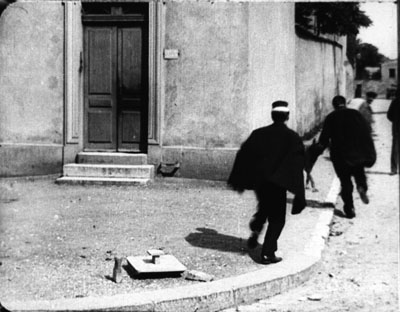

We can go back further. The Lumière brothers’ cameramen made fiction films as well as documentaries, and we occasionally find moments that suggest early efforts at gradation of emphasis. In Le Faux cul-de-jatte (1897), an apparent amputee is begging in the foreground while in the distance a man is walking down the street.

A cop crosses the street from off right and follows the pedestrian.

As the foreground fills up, the man we’ve seen in the distance gives the beggar some money.

As he goes out left, the cop is still approaching, and a vagrant dog appears.

The cop comes to the beggar, partially blocking the dog, who takes care of other business. (Not everything in this movie is staged.)

The cop checks the beggar’s papers and finds them to be suspect. The fake amputee jumps up and races off in the distance, with the cop pursuing.

As with many staged Lumière shorts, several figures converge in the foreground in order to create a culminating piece of action. Here the distant man and the cop, both secondary centers of interest, serve as a kind of timer, assuring us that something will happen when they meet at the beggar.

These are just some quick examples. We should continue to study the ways in which, with minimal use of editing, early filmmakers found ingenious ways to create gradation of emphasis. (2)

Some uses of grading

Barr, like most critics writing for the British journal Movie, was sensitive to the ways in which technique has implications for character psychology and broader thematic meanings. Kay’s bundle is one point along a series of changes in her character and her situation. But gradation of emphasis can serve more straightforward narrative purposes as well.

Consider our old friends, surprise and suspense. In the original 3:10 to Yuma (1957) Dan Evans is confronting the ruthless outlaw Ben Wade.

We get a string of reverse shots.

Then in one shot of Wade, without warning, a shadowy figure emerges out of focus in the left background.

Now we realize that Evans has been diverting Wade from the fact that the sheriff’s posse is surrounding him. Now we wait for Wade to discover it; how will he react?

While we’re on Glenn Ford, another nice example occurs in Framed. Mike Lambert has been romancing a woman named Paula, but we know that she and her lover Steve are plotting to fake Steve’s death and substitute Mike’s body.

She brings Mike to Steve’s elegant country house, having presented Steve as someone she knows only slightly. When Mike goes into the bathroom to wash up, we notice something important behind him.

With Mike at the sink, we have plenty of time to recognize Paula’s robe. Director Richard Wallace prolongs the suspense by giving us a new shot of Mike in the mirror, with the robe no longer visible.

But when Mike turns to leave, a pan following him brings him face to face with what we saw, accentuated by a track forward.

We get Mike’s reaction shot, followed by a cut to Steve and Paula downstairs, suspecting nothing. “So far, so good,” says Steve, looking upward at the bathroom.

The rest of the scene will play out with Mike aware that they’re deceiving him. As often happens with suspense, we know more than any one character: We know the couple’s scheme and Mike doesn’t, but they don’t (yet) know that Mike is now on his guard.

This isn’t as subtle a case as River of No Return, but I suspect that it’s more typical of the way Hollywood filmmakers use gradation of emphasis. Paula’s bathrobe is a good example of what I called in The Classical Hollywood Cinema the strategy of priming: planting a subsidiary element in the frame that will take on a major role, even if initially its presence isn’t registered strongly. My example in CHC was a coat rack in the Dean Martin/ Jerry Lewis comedy The Caddy (1953). In effect, the distant pedestrian in the Lumière film is an early example of priming.

Howard Hawks adopts the Lumière technique in order to sustain a flow of dialogue in Twentieth Century (1934). Here the foreground conversation is accompanied by a procession of people emerging in the distance and stepping up to take part.

The shot concludes, as does the shot of Faux cul-de-jattes, with a retreat from the camera.

The priming of secondary elements here, the summoning of the train attendant and the conductor, obeys Alexander Mackendrick’s dictum that the director ought to construct each shot so as to prepare for what will come next.

As Barr indicates, the idea of gradation shades insensibly off into general matters of cinematic expression. In The Devil Thumbs a Ride (1947), the bank robber has hitched a ride with an unassuming civilian, and they stop for gas. When the attendant shows a picture of his little girl, the robber gratuitously insults her. (“With those ears she’ll probably fly before she can walk.”)

Later, the station attendant hears a radio broadcast describing the fugitive. First he has his head cocked as he listens attentively, but then his gaze drifts to the picture of his little girl.

The attendant is the center of dramatic interest, but when he looks at the picture, so do we (primed by the view of it earlier). Instantly we understand that the attendant’s resolve to call the police springs partly from an urge to get even with the man who insulted his daughter. A minor instance, surely, but it illustrates Barr’s point that the notion of gradation of emphasis leads us to consider “the whole question of significant imagery.”

The more the merrier

Barr seems to favor a plain style; he prefers Preminger’s quiet framings to the rococo imagery of Aldrich’s Vera Cruz (1954). Presumably the famous shot above from Wyler’s Best Years of Our Lives (1946) would be too obviously composed for Barr’s taste.

But there is merit in considering how a secondary center of interest can vie for supremacy. André Bazin declared Wyler’s shot a bold stroke exactly because its self-conscious precision created a tension between what was primary and what was subordinate. (3) The action in the foreground is of dramatic interest because Homer has learned to play the piano, and this represents a phase of his coming to terms with his wartime disability. Yet the most consequential action is taking place in the distant phone booth, where Fred breaks up with Al’s daughter Peggy. The gradation of emphasis is inverted, and we wait in suspense to find out what happens. Bazin taught us to recognize that what appears to be primary may actually be creatively distracting us from the scene’s principal action. (4)

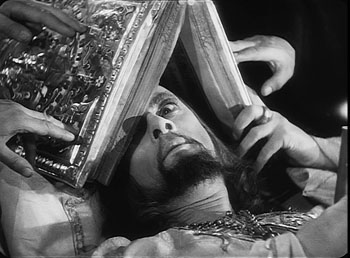

A director can also turn a primary center of interest into something secondary, but powerful. In one sequence of Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible I (1944), the apparently dying tsar is being prayed over by churchmen. Ever suspicious, he peers out from under the book, using only one eye.

As the scene develops, Prince Kurbsky meets Ivan’s wife and tries to seduce her. In the background an icon’s eye glares out, as if Ivan is watching them.

The single eye, which is a motif we find in other Eisenstein films, becomes a significant one throughout both parts of Ivan. More generally, this device manifests Eisenstein’s conception of polyphonic montage, which explored how the filmmaker can control all the various aspects of his images and make them weave throughout the film—promoting one at one moment, demoting it at another. (5)

Barr’s essay assumes that Eisenstein’s montage stripped each image down to a single meaning. In fact, though, Eisenstein wanted to multiply the sensuous and intellectual implications of each shot by weaving objects, gestures, body parts, musical motifs, and the like into an ongoing stylistic fabric. Each shot’s gradation of emphasis can suggest thematic parallels, deepen the drama, or heighten emotional expression, just as a complex score enhances an operatic scene.

Tati as well likes to create an interplay between primary and subsidiary centers of interest. Or rather, he sometimes abolishes our sense of what is primary and what isn’t. The crowded compositions of Play Time (1967) often bury their gags in a welter of inessential details. During the lengthy scene in the Royal Garden restaurant, a minor running gag involves the dyspeptic manager. He has just mixed some headache medicine with mineral water, but the action is easily lost within the tumultuous image. Even the soundtrack cues us only slightly, with a bit of fizz among the music and crowd noise.

As the manager lowers the glass, Hulot thinks it’s pink champagne being offered to him.

Rolling the stuff in his mouth, Hulot realizes his mistake as he earns a stare from the manager.

There is so much competing sound and activity in the shot that some viewers simply don’t notice this bit at all. In Play Time, gradation of emphasis is often flattened out, leaving us to rummage around the composition for the gag.

Some final notes

Barr was not particularly interested in the mechanics of how we come to notice something in the shot, be it primary or secondary in value. In On the History of Film Style, I suggested that many aspects of technique work to call attention to any element in the field. The filmmaker can put a something in motion, turn it to face us, light it more brightly, make it a vivid color, center it in the frame, have it advance to the foreground, have other characters look at it, and so on. These tactics can work together in a complex choreography. In Figures Traced in Light, I argued that they depend on the fact that we scan the frame actively; the techniques guide our visual exploration. (6)

You can see this guidance at work in most of the examples I’ve mentioned. In River of No Return, we are coaxed into noticing Kay’s bundle because we’re cued by movement (the bundle falls and drifts off), performance (she shouts, “My Things!” and stretches out her arm), music (we hear a chord as the bundle splashes), and framing (Preminger’s camera pans slightly as the trunk drifts away). The critic can refine our sense of the effects that a film arouses, but it’s one task of a poetics of cinema, as I conceive it, to examine the principles and processes that filmmakers activate in achieving those effects.

Finally, we might ask: To what extent do we find gradation of emphasis in current filmmaking? Today’s American cinema relies heavily on editing, using a style I’ve called intensified continuity. Each shot tends to mean just one thing, and once we get it we’re rushed on to the next. The unforced openness of the wide frame that Barr celebrated has been largely banned, in favor of tight singles—even in the 2.40 anamorphic format. It seems that most filmmakers are no longer concerned with gradation of emphasis within their shots.

To find this strategy surviving at its richest, I think we have to look overseas. If you want names: Angelopoulos, Tarr, Kore-eda, Jia, Hou. (7)

(1) It was published in Film Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 4 (Summer, 1963), 4-24. Unfortunately, it’s not available free online, nor is a complete version available in anthologies, so far as I know. If you have access to online journal databases, you can find it. Otherwise, off to the library w’ye!

(2) In the Poetics of Cinema piece (pp. 303-307), I argue that some early uses of Scope tried to approximate such tightly organized composition, despite technological barriers to focusing several planes of action.

(3) See André Bazin, “William Wyler, or the Jansenist of Directing,” in Bazin at Work: Major Essays and Reviews from the Forties and Fifties, ed. Bert Cardullo, trans. Cardullo and Alain Piette (New York: Routledge, 1997), 14-16.

(4) Actually the phone booth is primed for our notice by earlier shots in Butch’s tavern. See On the History of Film Style, 225-228.

(5) For more on Eisenstein’s idea of polyphonic montage, see my Cinema of Eisenstein (New York: Routledge, 2005) and Kristin’s Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible: A Neoformalist Analysis (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981).

(6) For some empirical evidence of this guided scanning, see the work of Tim Smith at his website and in this entry on this site.

(7) I discuss some of these alternatives in On the History of Film Style and the last chapter of Figures Traced in Light.

Eternity and a Day.

PS 15 Nov. Two more items. First, if the ideas floated here intrigue you, you might want to take a look at an earlier entry on this site, called “Sleeves.”

Second, I had planned to include one more example, but forgot it. In Lumet’s Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, Andy Hanson’s life is unraveling. We follow him back to his apartment, and as he enters on the extreme left, his wife Gina is visible sitting on the extreme right, her back to us.

Gina forms a secondary center of attention, but the key to the upcoming action is revealed in a third point of interest: the black suitcase pressed against the right frame edge. The shot tells us, more obliquely than one showing her leaving the bedroom with the case, that she is planning to leave him. Lumet’s image, reminiscent of the framing of the trunk in River of No Return, shows that gradation of emphasis isn’t completely dead in American cinema. The orange scrap of yarn, knotted to the handle for baggage identification, is a nice touch of realism as well as a welcome color accent that further draws the suitcase to our notice.