Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

FILM ART: AN INTRODUCTION reaches a milestone, with help from the Criterion Collection

[UPDATE, March 8, 2016: Film Art has now appeared in its eleventh edition, which, among other things, includes additional online Connect Film examples based on the partnership with the Criterion Collection mentioned below. For more information, see here.]

Somehow round numbers seem significant. This summer, Film Art: An Introduction is due to be published in its tenth edition.

We first set out to write the book in 1977, and it appeared in 1979. We’ve been gratified that it has retained an audience of teachers, students, and general readers over the ensuing decades. During that period, we’ve revised it to keep up with changes in filmmaking, in film studies, and in our own sense of what makes cinema a distinct artistic medium. At the outset we wanted to represent many eras of film history, a wide range of international films, and such important categories as documentary, experimental, and animated films. Our revisions over the years have tried to keep these goals in mind. At the same time, we realize that one way to engage students with ideas about film is to pay some attention to films they know, to enable them to look and listen to familiar movies in new ways.

We think we’ve stayed loyal to these purposes across nine editions. But with the fateful number ten we think we’ve stepped up to a new level. We’ve made many changes to the book that we find exciting; more about these below. The most dramatic development, however, comes through our new online partnership with The Criterion Collection.

Most teachers are familiar with Criterion and its high-end series of DVD and Blu-ray releases of classic and important contemporary films. In 1984, Criterion pioneered the genre of supplements, working at the time with laserdiscs. The team are 100% cinephiles, and they continue to set the standard for a rich array of bonus materials, all the making-of films, interviews, and documents that are of such interest to fans, scholars, students, and aspiring filmmakers. Now, with Criterion’s kind cooperation, we have produced a series of online examples tied to Film Art that will use scenes from several of their classics.

Film Art was the first introductory film textbook to use frame enlargements rather than publicity photographs as illustrations. Other textbooks have since imitated this approach, since it’s a vital tool when teaching students to analyze films. Nevertheless, even whole pages full of frames can’t fully convey the effects of techniques such as camera movement, graphic matches, staging in depth, and sound. The next logical step would be to use examples with scenes from movies, adding graphics and voiceover commentaries to clarify the points being made.

Problems of clearing rights and questions concerning the limits of fair use have made it difficult for textbook authors to supply adequate, high-quality moving-image examples on DVDs or online. The Criterion Collection has allowed us to make this big next step. We’re extremely proud of this new partnership, and we’re grateful to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrikson, Tyson Kubota, Giles Sherwood, and the rest of the Criterion Collection team for their generosity and help. Peter has written a blog about the new arrangement.

Online examples using clips from Criterion Collection films

The result is an hour-long set of twenty examples called Connect Film. Seventeen of these center around excerpts from film classics from the 1930s to the 1980s. David and I wrote the scripts and recorded the commentary tracks. The production, direction, editing, and special graphics were done professionally by Erik Gunneson, a filmmaker and Faculty Associate here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.The Criterion scenes are presented as moving images rather than still frames; it’s as if the sort of examples we use in Film Art have sprung to life. Erik has also produced three original demonstration videos laying out basics of lighting, camera lens length and movement, and continuity editing.

So why not check out one of our examples? Criterion has posted “”Elliptical Editing in Vagabond (1985),” in its entirety, on its YouTube page. Go here or watch it at the bottom of this post.

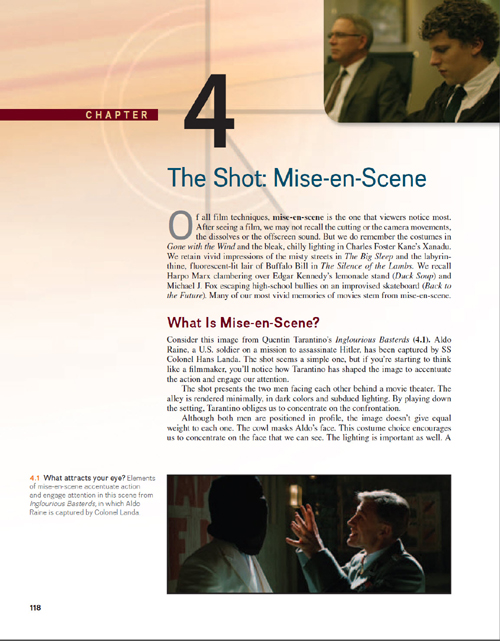

Chapter 4 Mise-en-scene

Film Lighting Demonstration This video clearly contrasts the results of side-, back-, and other types of light, as well as the principles of the three-point lighting system.

Light sources in Ashes and Diamonds (1958) The three sources of the light in the opening of the famous church scene are described and also indicated by colored arrows.

Available Lighting in Breathless (1960) This example starts with an extract from an interview with cinematographer Raoul Coutard, produced by the Criterion Collection. Coutard describes shooting without supplemental light in the lengthy bedroom scene, followed by an illustrative clip.

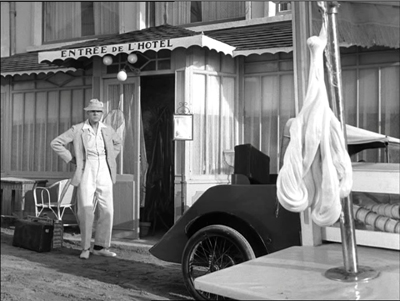

Staging in Depth in M. Hulot’s Holiday (1953; above) A scene of M. Hulot nervously watching a descending lump of saltwater taffy. The clip is run, then repeated with commentary discussing the comic possibilities of deep-space staging.

Color Motifs in The Spirit of the Beehive (1973) Yellow is associated with the bees in this film, but also with the malaise of Spain in the wake of its Civil War. The scene in which the color comes to be associated with the bees is shown, with still frames and commentary discussing other shots where yellow is prominent.

Chapter 5 Cinematography

Lens Length and Camera Movement Demonstration video contrasting the effects of long, medium, and short lenses. Erik also illustrates different types of camera movement.

Tracking Shots Structure a Scene in Ugetsu (1953; above) A wife and son bid farewell to a departing boat. Using a split-screen technique, we lay out the shots and show how camera movements are used to add to the ominous, poignant effect of the scene.

Tracking Shot to Reveal in The 400 Blows (1959) While the tracking shots in the Ugetsu example follow the characters’ movements, a scene from The 400 Blows shows how the camera can create other effects by moving on its own.

Style Creates Parallelism in Day of Wrath (1943) Similar camera movements prompt us to compare two scenes.

Staging and Camera Movement in a Long Take from The Rules of the Game (1939) In a scene that is rarely examined in this much-analyzed film, we trace out how a busy scene in a hallway, as guests head for their bedrooms, lays out the setting and highlights minor characters.

Chapter 6 Editing

Editing with Graphic Matches in Seven Samurai (1954) We use this example in discussing graphic matches in Film Art, but it’s hard to get a sense of the patterning from stills, So this clip shows the scene in its context and then replays the series of matches, freezing and laying them out across the screen.

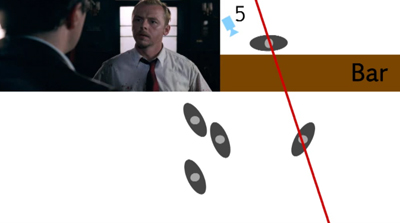

Shifting the Axis of Action in Shaun of the Dead (2004; above) Erik uses stills and overhead diagrams to show how the axis of action can be shifted when characters turn their heads and when new characters join the conversation.

Crossing the Axis of Action in Early Summer (1951) A friendly argument between Noriko and two of her friends employs cuts that consistently move back and forth across the axis of action. An overhead diagram marks the camera positions shot by shot.

Crosscutting in M (1930) Through a first run-through and then a replay with freeze-frames, we study how editing compares gangsters meeting and police meeting.

Elliptical Editing in Vagabond (1985) The enigmatic heroine lives her nomadic life, moving from place to place and meeting a variety of people, rich and poor. In a scene depicting her hitchhiking from near a convent to arrive in a barn, we show how the editing propels our interest but leaves out items of narrative information that increases the mystery of her character.

Jump Cuts in Breathless (1960) Some of the most familiar jump cuts from Breathless are illustrated in Film Art. This example uses a later scene in a cab which uses an unusually large number of such cuts. How many? Let’s count and see.

Chapter 7 Sound

Sound Mixing in Seven Samurai (1954) Our text describes the rich sound mix of the final battle of Seven Samurai, with rain, horses’ hoof-beats, men’s shouts, and other sound effects–all without music. Description, though, goes only so far. Now we can let readers listen for themselves.

Contrasting Rhythms of Sound and Image in M. Hulot’s Holiday (1953) Jacques Tati manages to create a double joke when musical tempo clashes with figure movement.

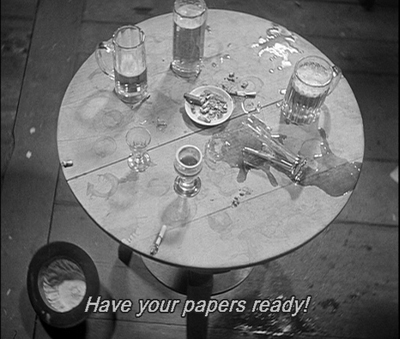

Offscreen Sound in M (1931; above) Even at the dawn of sound, Fritz Lang found inventive ways to avoid static dialogue scenes. Police raid a basement tavern, and even when there’s little movement onscreen we hear bustling activity outside the frame. Some shots, like this one, recall camera angles from earlier scenes.

Chapter 10 Animation

What Comes Out Must Go in: 2D Computer Animation Most of us are curious about computer animation, not least because it offers tools that amateurs and would-be filmmakers can learn to use. We show how independent filmmakers can get high-quality results in My Dog Tulip (Paul and Sandra Fierlinger, 2010) and Sita Sings the Blues (Nina Paley, 2008; above).

Instructors can stream any of these items in their classes, or students can watch them on their own.

Decisions, decisions

Chungking Express: To hear the voice on the line, or not?

Central as the Criterion extracts are, we’ve made other changes. We’ve done a top-to-bottom rewrite of the text, trying to make it more conversational, more like our blogging. We’ve updated our account of digital filmmaking and we’ve incorporated new information on digital distribution and exhibition–the sort of matters you can find in more detail in David’s Pandora series (which started here).

We’ve tried to make film art tangible for students by asking them to imagine alternative approaches to storytelling and technique. In keeping with this angle of approach, we’ve highlighted decision-making processes: the concrete choices faced by directors, cinematographers, editors, and other creative workers. One of the salient features of Film Art since the beginning has been its effort to blend the point of view of the critic or analyst with the point of view of the filmmaker. Here’s a passage from the first chapter.

Films are designed to create experiences for viewers. To gain an understanding of film as an art, we should ask why a film is designed the way it is. When a scene frightens or excites us, when an ending makes us laugh or cry, we can ask how the filmmakers have achieved those effects.

It helps to imagine that we’re filmmakers too. Throughout this book, we’ll be asking you to put yourself in the filmmaker’s shoes. This shouldn’t be a great stretch. You’ve taken still photos with a camera or a mobile phone. Very likely you’ve made some videos, perhaps just to record a moment in your life—a party, a wedding, your cat creeping into a paper bag. And central to filmmaking is the act of choice. You may not have realized it at the moment, but every time you framed a shot, shifted your position, told people not to blink, or tried to keep up with a dog chasing a Frisbee, you were making choices.

If you take the next step and make a more ambitious, more controlled film, you’re doing the same thing. You might compile clips into a YouTube video, or document your friend’s musical performance. Again, at every stage you make design decisions, based on how you think this image or that sound will affect your viewers’ experience. What if you start your music video with a black screen that gradually brightens as the music fades in? That will have a different effect than starting it with a sudden cut to a bright screen and a blast of music.

At each instant, the filmmaker can’t avoid making creative decisions about how viewers will respond. Every moviemaker is also a movie viewer, and the choices are considered from the standpoint of the end user. Filmmakers constantly ask themselves: If I do this, as opposed to that, how will viewers react?

Even if the reader never makes a movie, we think that getting comfortable with this framework can sensitize us to the power of cinema as an art form.

Of course, we also want to understand the finished film. We need to look at how the choices coalesce into patterns of meaning and effect. This is the holistic bent that the book has always had: we try to understand the choices in the context of the whole film and its purposes. To a large extent film form and film style are the terms we as analysts apply to the patterns of choices that shape our experience.

That emphasis on pattern is something that carries through all of our Film Art editions. It’s valuable to notice techniques or story twists in isolation, but we gain as well from seeing them as parts of larger patterns of organization. Such patterns and processes are highlighted in the case-study analyses in each chapter, as well as in the collection of analyses in Chapter 11. Likewise, Chapter 12 tries to trace some major strategies of form and style across history. The variety of films we consider allows us to spotlight some traditions that are less widely known than the Hollywood one–from France, Italy, Germany, Japan, Hong Kong, and other territories. Cinema is a global art, and we try to recognize that.

Over forty years we’ve learned a great deal about cinema from films and the people who make them. For this reason it’s been stirring to meet many filmmakers from North America, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East who tell us that they have learned something from Film Art. We offer the new edition in that spirit of common learning: to better understand a medium that we all love.

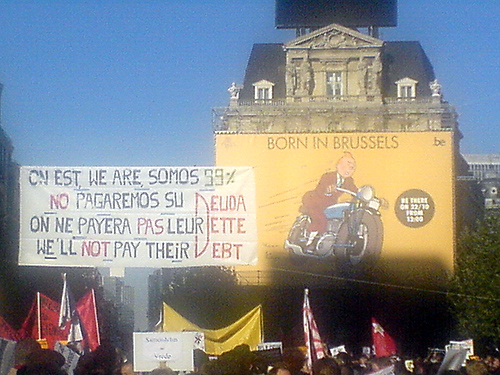

Catching up 99%

Clash by Night.

DB here:

Amplifications, corrections, and updates have been piling up over the last couple of months, and we began to realize that simply appending postscripts to older entries probably didn’t register with many readers. Judging by our stats, revisiting older entries isn’t a priority for most of the souls whom fate throws our way. So here’s some new information about older posts.

*I wrote about Jafar Panahi‘s This Is Not a Film at the Vancouver International Film Festival. Today Variety reported that an appeals court has upheld Panahi’s sentence of six years in prison and a twenty-year ban on travel and filmmaking. His colleague Mohammad Rasoulof’s jail sentence was reduced to a year. Panahi’s attorney says that she will appeal the decision to Iran’s Supreme Court. Be sure to read the Variety story for some background on the despicable treatment of other filmmakers, notably a performer who, merely for acting in a movie, was sentenced to a year in jail and ninety lashes.

*My trip to the Hong Kong festival last spring was to have included a visit to Japan. But the earthquake and the tsunami decided otherwise. Here are two remarkable items about the country’s catastrophe and the people’s resilience. First, a camera captures what it’s like to be in a car that’s swept away. Then we have photographs of the remarkable recovery that some areas have made–a real tribute to Japanese resilience. (For the links, thanks to Darlene Bordwell and Shu Kei.)

*My trip to the Hong Kong festival last spring was to have included a visit to Japan. But the earthquake and the tsunami decided otherwise. Here are two remarkable items about the country’s catastrophe and the people’s resilience. First, a camera captures what it’s like to be in a car that’s swept away. Then we have photographs of the remarkable recovery that some areas have made–a real tribute to Japanese resilience. (For the links, thanks to Darlene Bordwell and Shu Kei.)

*At Fandor, in response to Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, Ali Arikan wrote a penetrating and personal essay that I wish I’d had available when I wrote my review at VIFF.

*Tim Smith‘s guest entry for us, “Watching you watch THERE WILL BE BLOOD,” was a huge hit and went madly viral. At his site, Continuity Boy, he has posted a new, no less stimulating entry on eye-scanning. It shows that we can track motion even when the moving object isn’t visible!

*During my trip to Brussels in early September for the conference of the Screenplay Research Network, I stole time to visit the superb Galerie Champaka for the opening of its show dedicated to Joost Swarte (above). Longtime readers of this blog know our admiration for this brilliant artist, so you won’t be surprised to learn that I had to get his autograph. The show, consisting of work both old and new, was also quite fine; it’s worth your time to explore the pictures, such as the one revealing how Disney was inspired to create Mickey (above). Thanks to Kelley Conway for taking the shot, and to Yves for taking this one. And special thanks to Nick Nguyen (co-translator of two fine books, here and here) for alerting me to the show.

*An update for all researchers: Now that we have online versions of the Variety Archives and the Box Office Vault, we’re happy as clams. (But what makes clams happy? They don’t show it in their expressions, and their destiny shouldn’t make them smile.) Anyway, to add to our leering delight, we now have the splendidly altruistic Media History Digital Library, which makes a host of American journals, magazines, yearbooks, and other sources available in page-by-page format, ads and all. You’ll find International Photographer (too often overshadowed by American Cinematographer), The Film Daily, Photoplay, and many more. Get going on that project!

*This just in, for silent-cinema mavens: The Davide Turconi Project is now online, thanks to a decade of work by the Cineteca di Friuli. Turconi was a much-loved Italian film historian who, among other accomplishments, collected clips of frames from little-known or lost films. The archive of 23,491 clips, usually consisting of two frames, is free and searchable. On the left we see a snip from Louis Feuillade’s Pâques florentines (Gaumont, 1910). Paolo Cherchi Usai and Joshua Yumibe coordinated this project, with support from Pordenone’s Giornate del cinema muto, George Eastman House, and the Selznick School of Film Preservation. (Thanks to Lea Jacobs for supplying the link.) For more on Josh’s research, see our entry here.

*This just in, for silent-cinema mavens: The Davide Turconi Project is now online, thanks to a decade of work by the Cineteca di Friuli. Turconi was a much-loved Italian film historian who, among other accomplishments, collected clips of frames from little-known or lost films. The archive of 23,491 clips, usually consisting of two frames, is free and searchable. On the left we see a snip from Louis Feuillade’s Pâques florentines (Gaumont, 1910). Paolo Cherchi Usai and Joshua Yumibe coordinated this project, with support from Pordenone’s Giornate del cinema muto, George Eastman House, and the Selznick School of Film Preservation. (Thanks to Lea Jacobs for supplying the link.) For more on Josh’s research, see our entry here.

And while we’re on silent cinema, Albert Capellani is in the news again. Kristin wrote about this newly discovered early master after Il Cinema Ritrovato in July. A recent Variety story discusses some recent restorations and gives credit to the Cineteca di Bologna and Mariann Lewinsky.

*My entry on continuous showings in the 1930s and 1940s attracted an email from Andrea Comiskey, who points out that when Barbara Stanwyck and Paul Douglas go to the movies in Clash by Night (above), she prods him to leave by pointing out, “This is where we came in.” Thanks to Andrea for this, since it counterbalances my example from Daisy Kenyon, which shows Daisy about to call the theatre for showtimes. And since posting that entry, I rewatched Manhandled (1949). There insurance investigator Sterling Hayden hurries Dorothy Lamour through their meal so that they’ll catch the show. He apparently knows when the movie starts. So again we have evidence that people could have seen a film straight through if they wanted to. It’s just that many, like channel-surfers today, didn’t care.

*Finally, way back in July, expressing my usual skepticism about Zeitgeist explanations, I wrote:

I’m still working on the talks [for the Summer Movie College], but what’s emerging is one unorthodox premise. As an experiment in counterfactual history, let’s pretend that World War II hadn’t happened. Would the storytelling choices (as opposed to the subjects, themes, and iconography) be that much different? In other words, if Pearl Harbor hadn’t been attacked, would we not have Double Indemnity (1944) or The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry (1945)? Only after playing with this outrageous possibility do I find that, as often happens, Sarris got there first: “The most interesting films of the forties were completely unrelated to the War and the Peace that followed.” Sheer overstatement, but back-pedal a little, and I think you find something intriguing.

David Cairns, whose excellent and gorgeously designed Shadowplay site is currently rehabbing Fred Zinnemann, responded by email:

Firstly, I find the start of WWII being equated with Pearl Harbor a little American-centric. Much of the world was already at war when that happened. Secondly, it could certainly be suggested that the two films you cite WOULD have been different without a world war. Billy Wilder and Robert Siodmak were comfortably making films in France before Hitler’s invasion drove them to a new adopted homeland. Those movies might well have happened without WWII, but they would probably have had different directors.

Thanks for this. Your points are well-taken. Not only was I America-centric, but I neglected to point out that before Pearl Harbor America was more or less directly involved in the war. Even though America wasn’t yet in the war in late 1941, a lot of the economy was on a war footing and the industry was already benefiting from the rise in affluence among audiences.

Your point about the particular directors is reasonable too. I think I chose bad examples. All I wanted to indicate was that the Hollywood system continued to function as usual, particularly with respect to narrative strategies. For instance, Chandler wrote the screenplay for DOUBLE INDEMNITY (and apparently was responsible for the flashback construction), and as you say, had another director handled it, at the level of narration it might well have been the same. UNCLE HARRY is a harder case for me, I admit! Maybe I should have chosen THE BIG SLEEP and MURDER, MY SWEET!

David replied with his usual generosity:

That’s OK! BIG SLEEP and MURDER MY SWEET definitely work! Plus any number of non-flag-waving musicals, westerns, swashbucklers (though there’s a little propaganda message in THE SEA WOLF at the end) and certainly comedies and horror. . . .

And then there’s KANE and AMBERSONS.

Better late than never–something you can say about all these updates.

Reasons for cinephile optimism

Hollywood may have largely let us down this year, but after the first few days at the Vancouver International Film Festival, we’ve seen several excellent films and a lot of originality. Here are two of the highlights so far.

Kristin here:

Every year, when festival posts its list of films, I look through it for titles I’d heard about from other festivals or seen enthusiastically reviewed or had recommended to me. One title I was delighted to see on this year’s program was Lech Majewski’s The Mill & the Cross. It’s not nearly as famous as some of the other films showing here, like The Skin I Live In or Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, but I keenly anticipated seeing it.

I learned about The Mill & the Cross through an article in American Cinematographer (posted on the film’s rich website). Majewski collaborated with art historian Michael Francis Gibson to explore Pieter Bruegel’s 1564 masterpiece, “The Way to Calvary.” In the painting, the figure of Christ carrying his cross to calvary is set in the midst of a vast landscape full of fields, cliffs, a distant town, trees, and hundreds of people, all surmounted by a windmill atop one of the rocky formations and silhouetted against a windy, cloudy sky. Majewski sought, as he said, “to enter Bruegel’s world”—to enter into the painting itself and bring it to life.

His goal reminded me of Godard’s 1982 film, Passion, where one of the main characters films actors in a studio. He appears to be trying to replicate classic paintings, with models posed in costumes and miniatures representing a cityscape. I’ve never been able to picture what the result might have looked like. I’m not sure I would have enjoyed watching it, which may be part of Godard’s point. But Majewski had the tremendous advantage of modern computer technology to create an almost seamless blend between digital elements derived from the original painting and those derived from live-action filmmaking on location and in front of blue screens. For those who complain about “effects-heavy” blockbusters, The Mill & and Cross is a powerful counter-example, a film utterly dependent on CGI yet meditative and even profound. It certainly succeeds in Majewski’s goal, creating an uncanny sense of being inside the painting (see above.)

For the film seeks to explore the qualities that Bruegel himself did, to push the crucifixion to a minor place in the composition of the whole and to explore the sacred in the everyday. The film’s story is dense. On one level, we watch Bruegel sketching his models as he explains the concept of the painting to his patron. But we also see him departing home in the morning, and we follow the everyday doings of his family. We see several other minor characters who will figure in the painting waking up and beginning to work, including the miller in his mill atop the cliff. The filmmaking team found a surviving mill of the period, and for an astonishing scene early on, the ancient works in the vast interior were set in motion for the first time in centuries.

We see details of the characters’ lives, such as a man hitching up a horse to a wagon, an innocent-appearing detail until we realize much later in the film that this cart will deliver the wood for making the crosses and will carry the two thieves condemned to die alongside Jesus to Golgotha. Finally, we are invited to contemplate the contradiction, so familiar from thousands of paintings, that an event from antiquity is seen taking place in a contemporary landscape. The result is a comment on the Spanish occupation of Flanders as well as on the Biblical story.

In an all-too-brief scene, Bruegel explains the composition of the painting to his patron, showing how the small group around Jesus forms the center, with the lines between the other main elements around the periphery intersect with it. The implicit comparison is to a charming moment in the film when the painter admires an intricate spiderweb. Apart from all the thematic material, we do learn something about Bruegel’s painting–a point that is emphasized at the end of the film, which tracks back from the actual painting in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, as if inviting us to go and contemplate it in the light of what we have just seen.

Part of what makes The Mill & the Cross so exciting is that it achieves that rarest of things, making us feel that we are seeing something very worthwhile that has never been done before.

The film has a very limited release in the U.S. Anyone who has a chance to see it on the big screen should snatch it. The images, shot on the Red One camera and projected (here, at least) on 35mm, are spectacular.

Once upon a time, and time again

DB here:

Cesare Zavattini, central screenwriter of Italian Neorealism, liked to tell this story. A Hollywood producer once told him:

“This is how we would imagine a scene with an aeroplane. The plane passes by. . . a machine gun fires . . . the plane crashes. And this is how you would imagine it. The plane passes by. . . The plane passes by again… The plane passes by once more…”

He was right. But we have still not gone far enough. It is not enough to make the aeroplane pass by three times; we must make it pass by twenty times.

And, Zavattini seems to suggest, the machine gun should never fire.

Neorealism was one of the most important influences on what we’ve come to call the postwar European “art cinema,” and particularly on filmmakers’ treatment of time. I thought of the Zavattini passage while watching the opening scenes of Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, a film which proves that you can always ring fresh changes on a well-established tradition.

Actually, “opening scenes” isn’t quite right. The very first thing we see, a sort of prologue, presents in two shots the lead-up to a crime. Then come a couple of minutes of credits. Then we get nearly fifty minutes of nighttime shots of police cars driving through the countryside, headlights appearing tiny in the landscape. Again and again the cars halt as the police ask their murder suspect if this is the place where he and his brother buried the body of the man they killed. The suspect says he was drunk and can’t remember exactly. The investigators pick over the area looking for clues before driving on.

But the sequences aren’t quite as spare as I’ve indicated. Scenes inside the car and poking around the areas that might harbor the body pick out two main characters: a brooding doctor and a careful prosecutor overseeing the operation. The secondary cops and assistants are sketched in too. So we have a sort of balancing act between daringly distant “empty” shots and more standard expository scenes. The conversations in the car and in the landscape balance moments that dwell on atmospheric detail. So the relaxed pacing spares time for what will surely be one of the film’s most famous shots, a view of an apple shaken from a tree and bouncing downhill into a stream, where it continues to roll and bob in the dark. It presages the importance of melons, and in the final shots, a yellow soccer ball.

We frequently find that an art film flaunts some arresting narrational devices at the start before taming it as things move along. (Think of 8 ½’s bold opening, initiating us into Guido’s fantasy world, in effect teaching us how to watch the film.) Similarly, Once Upon a Time in Anatolia gets more linear and psychological as it goes along. It shifts from the more unfamiliar uncertainties of the futile stops and explorations to the better-defined questions we expect in a mystery. Is the suspect really guilty, or did his brother commit the murder? What triggered the killing? What effect has the crime had on the dead man’s wife and son?

The gradual shift seems to me to match a certain rigor in Ceylan’s stylistic handling. (Warning: Stylistic spoilers ahead.) In the nighttime search, long shots and extreme long shots dominate—if not by their number, at least by their prominence and vividness.

But having given us plenty of lengthy establishing shots in the first long section, Ceylan denies them in the next two portions.Later in the evening, the search party takes refuge in the house of a village leader and shares a meal with him. Here the action is broken up into close shots, with no long shots (I think) establishing where the characters are sitting. Everything, including the arrival of their host’s beautiful daughter, is given in tight shots of each character.

When the searchers return to town the next morning, they’re greeted by an angry mob. Again, the action isn’t shown fully. Now very long telephoto shots let us glimpse the police and the wife and son of the murdered man, with the crowd visible only as surging, out-of-focus heads and shoulders blocking the foreground.

The last forty minutes or so are centered on the doctor. Attached to him, we watch some interactions that trace out his responses to what he’s witnessed. These are handled in a traditional way, with shot/ reverse-shots, some of them head-on optical point of view, and lingering shots of the doctor brooding.

To the end, Ceylan doesn’t become completely predictable. There’s a nifty bit of elliptical editing during a conversation with the prosecutor. The offscreen sounds of an autopsy, layered by the sound of children’s play, recall passages of shrewdly timed offscreen dialogue that we heard during the long night’s search. And the final few shots play with optical point-of-view in a misleading fashion that has become something of a tradition in the art cinema.

So if the plotting gradually settles down into something less disconcerting, so does the visual style. But that shouldn’t take away from the delicacy and deliberation of a film that gains real gravity through hints and elisions. Above all, certain faces, particularly the despairing one of the prisoner who has a painful secret (surmounting this section), exercise a powerful hold on us. The conclusion of Once Upon a Time in Anatolia pulses with genuine emotion, coolly contained in a mode of cinematic expression that after sixty years or so continues to harbor great power.

The Zavattini passage on flying planes is available here.

PS 9 October: Thanks to Miklós Kiss for correcting an embarrassing spelling error.

Once Upon a Time in Anatolia.

PS October 8: Jim Emerson has also written on The Mill & the Cross, linking to an interview with Majewski on BOMblog.

Alignment, allegiance, and murder

House by the River (1950).

DB here:

“Point of view” is one of those terms that we can’t seem to do without, but it’s rather vague. The clearest application of the term would be to shots that conform more or less to what a character sees, presenting what we might call optical point of view.

But sometimes we’re given access to what a character sees, hears, and knows less narrowly. Without any optical pov shots, we might still be restricted to a character’s range of knowledge. This happens in detective films like The Big Sleep, which confines us almost completely to what Philip Marlowe knows. We follow him into scenes, stay with him as the action plays out, and then leave the scene when he does. We’re “with” him, but not via optical point of view.

In his book Engaging Characters, Murray Smith calls this sort of restriction to character knowledge alignment. He points out that it has both objective and subjective sides. Objectively, we’re spatially attached to a character in the course of a scene or several scenes. Subjectively, we may get access to the character’s thoughts, memories, dreams, or immediate perceptions (as with a POV shot). Spatial attachment refers to the limited range of our knowledge; subjective access refers to the depth of knowledge about the character’s inner experience.

But what about our emotional engagement with the characters? We usually call this “identification,” but Smith shows that this is a misleading way to think about what happens. Identification seems to imply taking on another’s state of being, but we don’t necessarily mimic a character’s emotions. We might pity a grieving widow, but she isn’t feeling pity, she’s feeling grief. Smith talks instead of allegiance, the extending of our sympathy and other emotions to characters on the basis of their emotional states. Allegiance, Smith maintains, depends partly on the moral evaluations we make about the character’s actions and personality.

Alignment and allegiance don’t necessarily involve us with only one character in the course of a film. Cases like The Big Sleep, which put us “with” Marlowe all the way through, are rare. Often a filmmaker shifts our alignment and allegiance away from one character to another, perhaps in the course of a single scene. That may involve some careful choices about staging, framing, sound, and cutting.

I offer you an example from Fritz Lang’s marvelously perverse House by the River. I’m afraid I can’t avoid spoilers, but at least I don’t give away the ending.

At the point of a nail file

Stephen Byrne, a struggling but well-to-do writer is married to the lovely Marjorie. But this doesn’t stop him from trying to seduce their maid Emily. While struggling with Emily, Stephen strangles her. With the help of his brother John, he stuffs Emily’s body into a large sack and deposits it in the river. Stephen’s crime has stirred something in him, and he begins writing a new book, Death on the River, with its plot based on what he has done. Meanwhile, an inquest into Emily’s disappearance casts suspicion on John as her killer.

The very end of the inquest scene has shown the prosecutor and chief inspector confronting Stephen, who says he won’t do anything to incriminate his brother. Since neither John nor Marjorie knows of this conversation, we’re aligned with Stephen. He now has precious information: the police are likely to be watching his brother, not him.

Our alignment with Stephen continues at the start of the next scene, which shows him at work on his manuscript. Marjorie comes in and asks to talk with him about Inspector Sarten.

After a pause to consider, Stephen reluctantly follows her into her bedroom. Lang’s camera, angled along the corridor, puts us strongly with him.

As Stephen enters the bedroom, Lang continues to favor him. Stephen comes into a knees-up shot facing front, but the answering shot of Marjorie weeping at the window is more distant, approximating his optical point of view.

Often filmmakers give us slightly stronger alignment with one character than another by framing one more closely than another. That happens here, I think, for Lang repeats these camera setups several times as Stephen apologies for being snappish and asks Marjorie what she wants to tell him. We know he’s being pleasant only because he wants information.

She comes forward and sits, reporting that she has seen the detective following her. Now we can see her expression more clearly and she is less remote from our concerns.

Again the setups repeat for a bit, with the framings still making Stephen more salient. Aligned with him, and to some extent allied as well, we are able to share his sense that danger is approaching. Stephen comes forward and steps into a more neutral and balanced framing. I’d argue that our sense of being “with” him now begins to taper off.

Marjorie points to the window (in one of Lang’s compositionally accented gestures) and suggests that an officer may be watching the house. Stephen goes to look out.

Stephen suggests that the police should be targeting John, since he’s acted suspiciously after the inquest. As Stepehn talks, he saunters to the dressing table and uses the file there to smooth his nails. He suggests that John may very well have had an affair with Emily. Although the framing is in long shot, we can see Stephen’s expression clearly, and it’s duplicated in the mirror. By contrast, when Marjorie rises indignantly and upbraids him, her back is mostly to us.

Stephen sits, remarking, “There’s a limit to this business of being brothers, Marjorie.” She turns slightly, saying, “Stephen, you’re insane.” This line prompts a cut to Stephen, still smoothing his nails but turned from us.

His face turned away and no longer visible in the mirror, Stephen says casually, “You’re very fond of him, aren’t you?” Now we’re more aligned with Marjorie, seeing more or less what she could see. Lang could have staged this phase of the scene to give us more information about Stephen’s expression (say a low-angle depth shot with his face in the foreground), but the opaque shot we get is balanced by a close, clear view of Marjorie for the first time in the scene–another step toward alignment and allegiance with her. The turned-away shot of Stephen also highlights his gesture of filing his nails, important in what will come next.

Cut to a medium shot of Marjorie’s reaction. “You know that.” Back to Stephen: “Are you in love with him?”

Stephen doesn’t see her reaction, which confirms his guess about her feelings for John, but we do. More important, our allegiance shifts toward her too. We know that Stephen is lustful (he’s seeing women in town every night), but Marjorie is suppressing her fondness for John for the sake of her marriage vows. She has the moral edge.

He questions her further, finally turning to her and grinning: “Don’t think I haven’t been aware of it.” Cut back to her: “You have a filthy mind”—something we know to be true. Her moral scheme fits ours, and sympathy for her builds.

This riposte wipes the smile from his face and he walks slowly toward her, the nail file extended like a knife, but also waggling jauntily in his hand. He recovers his flippancy and assures her he doesn’t feel any jealousy toward John because he no longer finds Marjorie attractive.

After he says he finds cheap perfume exciting, she calls him a swine. He resumes filing his nails. Stephen leaves the shot but, crucially, Lang’s camera dwells on Marjorie, glaring after him.

The scene’s final shot shows Stephen strolling down the corridor, and it ends with him smiling and slamming his door. It is a kind of symmetrical reply to the early shot of him going to her room.

This point-of-view shot anchors us with Marjorie, both perceptually and morally. She now realizes that she is the only ally John has.

Marjorie doesn’t know that Stephen is the killer and that John helped him dispose of the body. As often happens in films, we know more than any one character. As a result, we can register suspense when Stephen approaches with the nail file (we know he’s capable of stabbing her), but she evidently doesn’t feel herself in danger. To put it more generally, a string of scenes which restricts us to one character after another gives us a moderately unrestricted knowledge of the overall narrative.

Still, moment by moment, the director can use film technique to weight one character’s reaction more than another’s. We can balance those short-term reactions against our wider compass of knowledge. Our sympathies can shift as we register characters’ changing awareness of their situation, however partial their awareness may be.

Interestingly, the end of this scene, emphasizing Marjorie’s new understanding of Stephen’s turpitude, links to the next scene rather neatly. We see John at home, drinking with grim determination, but when he answers the door he finds Marjorie there.

The segue to Marjorie as a center of consciousness in the bedroom scene prepares for her going to comfort John.

More broadly, the shift initiates a new phase of the film in which Stephen must further cover up his crime. For nearly all of the film’s first half-hour, we’re restricted to Stephen’s ken, when he commits and covers up his crime. After that, the film’s narration alternates between scenes organized around Stephen and ones organized around John, with two brief ones centering on Marjorie. The inquest, at twelve minutes the longest sequence in the film, gathers together all the characters and functions as something of a neutral and objective reset.

That scene is followed by the one I’ve examined, in which we return to Stephen writing a manuscript, as we saw him at the start of the film. The new scene’s narrational weight briefly shifts, as we’ve just seen, from him to Marjorie. After she leaves John’s house, however, the film will build suspense by attaching itself almost wholly to Stephen as he plots to kill both his brother and his wife.

Smith points out throughout his book that alignment and allegiance are complicated matters. It sometimes happens that we have sympathy for the devil–someone who’s acted immorally but whom we might root for to some degree. Bruno in Strangers on a Train is a classic example. And we can think of instances of villains who engender some sympathy because they have some admirable features or because they are treated unfairly.

So I don’t want to leave you with the impression that Lang hasn’t toyed with our allegiances more severely in other stretches of House by the River. At the start, Stephen is at best a bounder, but who doesn’t want him to succeed initially in hiding his crime? (For one thing, if he didn’t try, the story would be over too soon.) And there may be something admirable in his cleverness and bravado as he tries to palm the guilt off on John. My discussion of this scene simply wants to show that the fluctuations of alignment and allegiance can be quite small-scale, and they often depend on niceties of directorial technique.

Craftiness

Artistry depends on craft, and craft is something both cinephile critics and academics have neglected.

Coming across that sentence in a recent essay in Film Comment, you might have a question. What is craft, and how is it different from artistry?

Some thinkers, most famously R. G. Collingwood, saw a sharp line dividing the two. I’m more inclined to see them on a continuum, at least in certain art traditions. In film, I’d suggest that craft consists in fulfilling the task at hand with skill and efficiency.

Craft implies a set of norms, a default or standard that any competent artisan should be able to fulfill. Artistry then, we might say, becomes a plus. It goes beyond the task’s narrow purpose. Ozu’s establishing shots, for example, do more than establish the locale of the upcoming scene. They create intricate plays with compositional motifs that recur through the entire film. Artistry may not necessarily add complexity, though; it can also compress and concentrate. Bresson eliminates establishing shots and providing environmental information through glimpses of background or information on the soundtrack.

Sometimes artistry adds a psychological complexity not apparent in the bare-bones task. This might be given through performance and/or the way the scene is shot. This is what I think happens in the House by the River scene. It’s not a flamboyant job of direction. We need to take a little effort to see how Lang has set up the master shot to allow Stephen to go to the window, then to the dressing-table; and to see how Lang has reserved the closer shots of the couple for a new level of conflict.

But so much might have been done by any solid artisan. And you could imagine other ways to shoot the scene. Someone like Preminger might have presented the entire encounter in a few balanced two-shots. Lang’s extras—the discreet use of optical point of view, the analogous corridor shots, and the subtle variation in shot scale between Stephen and Marjorie, not to mention Stephen’s playful waggling of the nail file—build subtle attitudes toward the characters.

Call it artistry, or cunning craft. Either way, it shows how directors can shape our experience by adjusting the range and depth of our knowledge, sometimes in small but powerful ways.

The distinction between range and depth of information in cinematic narration is presented in Film Art: An Introduction, Chapter 3 and in my Narration in the Fiction Film. For more on these concepts, see Meir Sternberg’s Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction. Murray Smith’s Engaging Characters refines these and other distinctions in order to understand how we grasp character in film.

Tom Gunning’s The Films of Fritz Lang offers a detailed, fascinating commentary on House by the River, concentrating especially on motifs of writing, mirroring, and filth.

For other entries on the craft of staging dialogue scenes, go here and here and here and here elsewhere on this site. For more on niceties of direction, from a director seldom credited with such, try here.

House by the River (1950).