Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

Forking tracks: SOURCE CODE

Source Code.

DB here:

Who cares if the Source Code software is junk science? The muzzy premise forms the basis of an agreeable little thriller from the tail end of this year’s Dead Zone. Even if you don’t share my admiration for this movie, maybe I can persuade you that it points up an intriguing wrinkle in the recent history of American studio storytelling.

I surveyed this history in some books, but Source Code provides a nice occasion to update my argument. My main point remains: More than we often admit, today’s trends rely on yesterday’s traditions. Quite stable strategies of plotting, visual narration, and the like are still in play in our movies. When a movie does innovate in its storytelling, it needs to do so craftily. The more daring your narrative strategies, the more carefully, even redundantly, you need to map them out. The game demands clarity through varied repetition.

More generally, there’s a value in thinking of movies as combinations and transformations of inherited conventions. We’re used to considering conventions as matters of theme and genre, but I’m equally interested in conventions of technique and of narrative form. These are areas we’re still only starting to understand, although many entries on our site try to make progress in understanding changing norms of style and storytelling. (Check our Narrative Strategies category for further leads.)

If you haven’t seen Source Code, you shouldn’t read on. I reveal damn near everything.

He couldn’t come home

Colter Stevens awakes on a Chicago commuter train in the body of another man, Sean Ventress, who’s accompanying the attractive Christina Warren. Very soon the train explodes, and Colter reawakens in a pod in a military facility. He learns that after being shot down in Afghanistan he has been at the Nellis facility for two months, awaiting an experiment in “time realignment.”

Because a person’s brain activity does not cease immediately at death, memory modules can be accessed across an eight-minute period before full shutdown. Colter’s brain anatomy happens to be attuned to that of Ventress, so the experimenters can in effect insert his mind into Ventress’s body in the few minutes before the train explosion. The investigators know that the bomber is planning to set off a much bigger explosion in downtown Chicago, and Colter-as-Ventress could gather enough information to prevent it.

Under the tutelage of officer Goodwin and her superior, chief researcher Rutledge, Colter will be sent back in to the train, neurally speaking, to try to identify the bomber for them. He cannot prevent the train blowup, Rutledge insists. He can only hope to identify the bomber before the dirty bomb goes off downtown. But Colter can, in the shrinking time remaining, be sent back again and again, though it’s physically and emotionally punishing for him.

As a result, the film alternates between two zones of action. At the Nellis facility, time moves forward as Colter gradually comes to understand his circumstances and his mission. This action is under the pressure of a deadline: find the culprit before the dirty bomb is triggered. The other zone of action is the train, where the deadline is tighter (eight minutes before Ventress’s death) and the action is replayed as Colter tries different tactics to fulfill his charge.

Many incidents fill out this dynamic. In the pod, the early scenes are dominated by Colter’s efforts to understand the experiment he’s involved in and to grasp what has happened to him since his chopper crash. He is being kept alive artificially so that his brain activity can sync with Ventress’s. Eventually he breaks through Goodwin’s façade of coldness, converting her to sympathy for his plight. When she finally stares compassionately down at his broken body in its glowing casket, she resembles a mother or nurse looking down at a baby. On the train, the early scenes throw up some decoy suspects, most prominently an agitated man of vaguely Middle Eastern appearance. He is proven not to be the bomber, who’s eventually revealed as a dough-faced nerd. (Between the stereotyped Islamic terrorist and the stereotype domestic one, the plot opts for the latter.)

Colter not only blocks the Chicago bombing; with Goodwin’s help he is sent back one last time to stop the train bombing as well. In the course of that effort, he manages to reset the past, creating a parallel world in which the briefcase bomb never ignited and the bomber was captured before he left the train. Colter, dead at the Nellis facility, becomes Ventress wholly, able to spend a day with Christina and to send a text message to Goodwin promising that the Source Code has even bigger possibilities than Rutledge imagines. It can change the course of events. And she can reassure Colter’s original self, when he finally is sent on a mission: “Everything’s gonna be okay.”

It’s the new me

This plot is articulated in quite traditional ways. At less than 90 minutes, the film yields three large-scale parts or “acts.” The Setup introduces us to the premises, establishing the train bombing and the Nellis facility supervision; I’d argue that this ends at about 28 minutes. At this point Colter, has to rule out his chief suspect, the commuting businessman with motion sickness, when the train explosion takes place. The second stretch of the plot consists of more failed efforts, but culminates at about 56 minutes, when Colter correctly identifies the bomber, Derek Frost. Again, he can’t forestall the train bombing, but returning to his capsule he passes the key information to his masters, and they can arrest Derek before the dirty bomb hits Chicago. At this point his official mission is over. But the movie isn’t. Colter persuades Goodwin to let him go back one more time to stop the train bomb and save the passengers—effectively countermanding Rutledge’s injunction that the past can’t be altered. A three-minute epilogue starting around 82:00 wraps things up.

Filling out this structure is the characteristic double plot of classical Hollywood: heterosexual romance plus another, usually connected, line of action. The suspense plotline is organized as a series of goals, initially articulated by Goodwin. She tells Colter to find the bomb, which he does in the first replay. But as he can’t prevent the explosion, he needs to know more about who’s behind it. His next passes proceed in steps. He has to identify the guilty passenger; then he must try to steal the conductor’s pistol; then he searches for bomb-related paraphernalia.

About halfway through the film, however, Colter conceives purposes of his own. Inside the capsule, he probes Goodwin about what has happened to him. On the train, he starts to investigate the insignia of the agency controlling him, to trace his own fate in Afghanistan, to try to contact his father, and to phone the Nellis facility. He’ll eventually succeed in all these attempts, balancing the failures of the first chunk of the plot. Ultimately he’ll decide to try to save the train. Crucially, this last goal is formulated after he believes that having been more or less killed in Afghanistan, he is about to be terminated by the Source Code project. So he can now operate in a mode of pure self-sacrifice. As often happens in a classical film, a character finds the resources to throw off others’ demands and make decisions on his own.

In the romance plotline, by assuming the identity of Sean Fentress, Colter becomes attached to Christina. Now saving the train takes on a more personal weight; he will be saving her. The emotional dimension here is deepened by Colter’s backstory, his unresolved relation to his father. Eventually he is able to get closure by posing as Fentress and phoning tell the grieving old man that Colter indeed loved him. In screenwriters’ parlance, Colter is “exorcising his demons.”

Colter’s growing confidence in dealing with his past and the bomb threat changes his behavior toward Christina. No longer the skittish neurotic of his early incarnations, he becomes brisk and confident. Eventually he can relax, paying the standup comic across the aisle to entertain the other passengers. As often happens, character change is measured by a repetition. The first time Colter says, “It’s the new me,” he refers ironically to his discovery that he’s in another man’s body. But now, as the comic launches into his shtick, Christina points out that her companion has changed. He answers by saying, “It’s the new me,” which signals a deeper acceptance of his sacrificial role. He doesn’t expect to survive after he returns to the capsule, but he has saved the people on the train and he can for a moment celebrate a final moment of vitality.

This is not a simulation

These cascading goals and character arcs emerge gradually, thanks to cunning narration. At first we’re restricted largely to what Colter knows, but gradually our awareness widens. We come to learn about Goodwin’s role in the Source Code project and about Rutledge’s ruthless efforts to use Colter as a test case. By the climax, the film cuts freely between the two arenas, the train and the Nellis compound, creating classical suspense as Goodwin postpones erasing Colter’s memory while he races to prevent the train blowup. This is the Griffith heritage of the last-minute rescue.

For the viewer, the film starts with mystery—Colter is on the train and he doesn’t know who he is—and moves toward a mixture of curiosity about his past and suspense about how he will solve his problem. By the start of the climax, we have understood all the forces converging on Colter’s last mission, and sheer suspense takes over. There is, though, one final surprise, which seems to have worried other critics more than it does me. More on this shortly.

Even before the explicit widening of narrational knowledge, we’ve been given a dose of something enigmatic. The shifts from the train explosion to the Nellis pod are provided with whooshing transitions of blurred and fragmentary imagery that, as the film goes on, clarify a bit. At the film’s center, these images will be replaced by distorted flashbacks to his helicopter crash in Afghanistan, a passage that leads him to ask Goodwin: “Am I dead?”

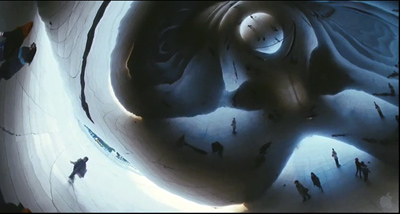

One of the images glimpsed in the vortex montages is that of Anish Kapoor’s Cloud Gate sculpture, which Christina and Colter-as-Sean will visit in the epilogue.

Thematically, the image can be taken as an emblem of the lives Colter has saved, with a hazy overlay that reminds us of his floating consciousness for most of the movie. But the more basic question is about the status of these blurry visions. Are they Colter’s premonitions of a future to come? That assumption seems confirmed at the end when Colter, staring at the sculpture, asks Christina if she believes in Fate. At the same time, the images can be treated as coming from outside his ken, as if the film were providing teasing hints about how the action will resolve.

In these montages we see an interplay between destiny and chance common in Hollywood storytelling. (Christina answers Colter’s question by saying she’s “more of a dumb luck kind of girl.”) Very often, even if chance seems to govern the plot, a film’s overarching narration seems to “know” how things will turn out. Thus the film can have it both ways, acknowledging that life sometimes depends on chance but also recognizing that satisfying stories feel inevitable.

As usual, you will have eight minutes

Since the early 1990s, many films have resorted to what we might call“multiple-draft” plotting, the replaying of key scenes with important variations. Groundhog Day (1993) is our prototype, and it influenced Source Code screenwriter Ben Ripley. An earlier instance is the alternative futures revisited by Marty McFly in Back to the Future II (1989). Yet these films revived an older, although minor, trend going back quite far in Hollywood. The device was sometimes used to present alternative futures, as in The Love of Sunya (1927), but more commonly it presented different characters’ versions of what happened in the past. We find it in the courtroom drama Thru Different Eyes (1929), which dramatizes conflicting trial testimony, and in Crossfire (1947), which somewhat anticipates Rashomon‘s use of the strategy. Contradictory replays are used for more comic effect in The I Don’t Care Girl (1953) and Les Girls (1955).

What led to the resurgence of multiple-draft storytelling in our day? Partly, I think, the changing genre ecology of Hollywood. During the 1970s and 1980s, certain genres like the musical and the Western faded out, and horror and science-fiction/ technofantasy became more important. These genres, still going strong today, encourage playing around with subjective states (dreams, hallucinations), devising misleading narration, and creating branching and looping timelines (through time-travel, telepathy, multiverses, and the like). The filmic experiments probably owe something as well to the rise of popular writers in the vein of Stephen King and Michael Crichton, along with the revival of the work of Philip K. Dick.

Pop science also furnished new narrative possibilities. Researchers discovered the Butterfly Effect: change one little condition at the start of a process, and you get a different result. There was the Forking-Path, or Choose Your Own Adventure, option, whereby you can imagine taking a different path in your life. And there was the Multiple-Universe Hypothesis, whereby we can hop from one parallel world to another.

Even without the pseudoscientific justification, the reset-replay option showed up in films that were influenced by earlier storytelling. Film noir sometimes resorted to replaying scenes in ways that filled in information missing on the first pass (e.g., Mildred Pierce, 1945). Tarantino made no bones about being influenced by the overlapping flashbacks in The Killing (1955), themselves derived from Lionel White’s original novel Clean Break. So in the wake of Reservoir Dogs (1992) and Jackie Brown (1997), we got many thrillers and crime films that retold the same events from different characters’ viewpoints (Out of Sight, 1998), right up to an almost endless series of replays (Vantage Point, 2008).

All of these multiple-draft tactics made their way into global cinema too; Run Lola Run (1998) is a prominent example, but so too is the dazzling anime The Girl Who Leaped through Time (2006). In America, the market’s constant demand for something novel (but not too novel) pushed filmmakers toward all the variants we see in films as different as Thirteen Conversations about One Thing (2001) and Confidence (2003).

For mainstream filmmakers the key is redundancy. The reset-replay device has to be explained through dialogue, diagrams, intertitles, and sheer repetition so that we understand it going forward. (Contrast, say, Primer, which left most viewers behind.) Once we’ve grasped the similarities in the core situation, we can measure the differences in each iteration.

Source Code director Duncan Jones had already shown an interest in replays in Moon (2009), with its Möbius-band treatment of the crashed lunar vehicle, followed by Sam’s awakening in the infirmary. The mystery of the first encounter, in which Sam seems to find another version of himself in the vehicle, gets slowly cleared up through dialogue, the discovery of a secret repository, and not least important, a bandaged hand wound that allows us to keep the two Sams more or less distinct. Similarly, in Source Code, the returns to the train can be more elliptical as we master the situation: the introductory shots (duck pond, Colter waking up) can be skipped or compressed. Our training is guided by Colter’s, as he starts to predict the trivial incidents (coffee spill, cellphone call from Christina’s ex) and handle them matter-of-factly. These repetitions anchor us and allow us to register the different actions he undertakes in each module.

Those modules are ruled by another convention, what screenwriting manuals call the ticking clock. Usually reserved for the climax of films in all genres, even romantic comedies, the ticking clock plays a bigger role in Source Code. It governs both the macro-level (the deadline to stop the dirty bomb) and every return to the train. Strikingly, those replays are very strictly contained. Colter is assigned eight minutes for each mission, and by my count each of the developed train episodes before the climax consumes anywhere between four and eight minutes of screen duration, never more. His recurring deadline becomes a structural cell of the movie.

We have a chance to start over in the rubble

Déjà vu.

Multiple-draft storytelling promises to abandon the classic “linearity” of Hollywood storytelling, but the promise is largely a tease. The convention gestures toward unruly complication, but it tends to reinstall linearity, sorting everything out and making the final stretch of the film seem a logical consequence of what went before. Despite all the cycles and skip-backs of Groundhog Day, Phil changes incrementally into a kinder person and gets the woman he has come to deserve. In the money-drop sequence of Jackie Brown, the minute variations of point-of-view mesh into a single comprehensive account of how the scam went down. Part of the fascination of the technique for us may be similar to what a child feels after spinning around and stopping: the dizziness is fun, but so too is the bumpy readjustment to a stable world.

Source Code wants a happy ending. Does it prepare us sufficiently? We have the vortex transitions that look forward to the Cloud Gate epilogue, but are these enough? Don’t we need something at the level of plot action?

In his last visit to the train, Colter manages to disarm the briefcase bomb and capture Derek Frost. So now the train didn’t explode; the Nellis facility was never put on alert to forestall the dirty bomb; Rutledge and Goodwin never tried using Colter as their Source Code guinea pig. Rutledge earlier denied that this revision of the past would be possible, but the plot nonetheless moves us into a parallel world characteristic of forking-path plots like Run Lola Run and The Butterfly Effect (2004). And this reality has become sovereign, since Colter can now successfully send Goodwin a text message advising her about the unexpected success of the Source Code stratagem. This also means that as more or less a brain in a vat, the wounded Colter survives to serve in other missions.

Given the right sort of motivation, then, the forking-path option can be activated as a resolution device for multiple-draft plots. The film’s makers invoke a multiverse explanation explicitly in one piece of publicity for the film (trailer 2 here). More important, we’re prepared to accept such a switch on pretty slender evidence. Counterfactual thinking in terms of forking paths is a part of our folk psychology. If only we’d left the parking lot ten minutes earlier, we wouldn’t have hit this traffic. If I hadn’t taken this job, I wouldn’t have met my husband….and so on. Despite what experts like Rutledge say, when we see Colter disarm the lethal briefcase, we’re prepared to buy the possibility that everything afterward has changed.

Still, we need some elements in the movie itself to justify the jump. During his final questioning of Goodwin, Colter asks if she could imagine a world in which she didn’t get divorced, being “a woman who took a different fork in the road.” Colter insists that the course of events is changeable: Christina “doesn’t have to be dead.” At various points he says he thinks he can save the train, but like Rutledge, Goodwin reasserts that there’s only one reality, and its events have already happened.

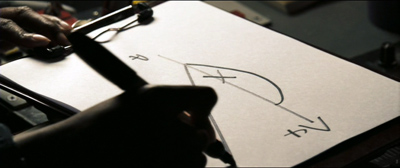

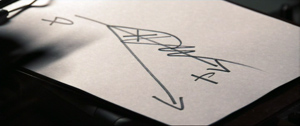

Interestingly, the debate itself might be a minor convention of the multiple-draft plot. In Tony Scott’s Déjà vu, (2006) a close analogue to Source Code, two scientists disagree about whether the past is malleable. Professor Denny says that you cannot change what’s already happened. “God’s mind is made up about this.” But his colleague Shanti adheres to the “branching universe theory,” which she helpfully draws on paper for our benefit (echoing Doc’s famous diagram in Back to the Future II). A significant event, Shanti maintains, can shift the course of events and create a new path. It can even, she claims, wipe out the branch that was initially taken as baseline reality.

Images of linearity deflected, of hiccups and branches off a main line, show up in Source Code too. The train bomb is fired off just as another train passes on a parallel track. But in the final replay, after Colter has set things right and paid the comedian to do his turn, we see “all this life”—the passengers frozen in amusement. The shot is a kind of marker that, as Shanti puts it, something big has changed. Abruptly we get a shot we haven’t seen before: a high angle of our train switching to another track. Then we cut back to Colter and Christina about to kiss, as the rival train passes safely. Our train’s new trajectory confirms that an alternate reality has been put in place. It also echoes an earlier line, when Christina, talking about her plans for the future, asks Colter: “Am I on the right track?”

This will end

Source Code appropriates the forking-path option in order to arrive at a final draft of Colter’s fate. This stratagem reflects a common tendency in the history of narrative forms. Over the years, as readers become more skilled in picking up conventions, authors can be more elliptical and oblique. Descriptions can be more bare-bones, and authorial commentary can be given in a phrase rather than a paragraph. (Elmore Leonard: “I leave out the parts that readers skip.”) Films that once needed to motivate alternative futures through dreams or fortune-telling now do so through scientific gadgetry, or just by referencing similar movies.

We surely lose something in a trend toward such laconic storytelling, but there are gains in speed and impact. What Déjà vu debates for minutes can be abbreviated in Source Code because audiences have caught on: a few cues suffice to let us figure out how this sort of story goes. For me, the very premise of the replay device, plus Colter’s raising the issue of forking paths with Goodwin, plus our commonsense psychology, plus the swooshes, plus the convention of the happy wrapup, not to mention the overall urge to reward our our hero for all his sacrifice—all this is enough to push the ending over the finish line.

More generally, you can invoke Steven Johnson’s argument that we’re getting smarter about picking up quickly-emerging conventions. Popular culture, he claims, is more intellectually demanding than it used to be; examples would be The Wire and Lost. I’m not wholly convinced, since Our Mutual Friend and other items consumed by generations past can be pretty complex, and twentieth-century middlebrow artists like Thornton Wilder, J. B. Priestley, and Alan Ayckbourn have flirted with formal experiment. I’d relate the intricacy of some popular narratives partly to the proliferation of more niche genres and specialized publics, along with the growth of pop connoisseurship. Aging hipsters and cool college-educated youngsters, fortified with high disposable incomes, now flaunt a nerdy side and enjoy avant-gardish innovations.

For whatever reasons, in a lot of mass storytelling, form is the new content. But that newness depends considerably on recasting long-standing traditions. Nothing comes from nothing. And it can be fun to trace the fluctuating dynamic of novelty and familiarity as it emerges in the movies that we see right now.

At Electric Sheep Duncan Jones elaborates on the forking-path dimension of his film.

This entry builds on work I’ve done elsewhere. For more on classical conventions of plotting and narration, see The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960, part one, and Narration in the Fiction Film, Chapter 9. On recent narrative innovations and their relation to classical premises, see The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies, 51-103. On forking-path plots and their relation to folk psychology, see the essay “Film Futures” in Poetics of Cinema. One essay in that volume discusses Mildred Pierce‘s tricky replay of the opening murder, while another surveys another contemporary trend, the network narrative.

On dividing a film’s plot into parts, see Kristin’s earlier entry and my essay on Mission: Impossible III. Go here to see what happens when Archie Andrews takes a forking path.

Yes, there’s something similar to be done with The Adjustment Bureau. But I leave that to others.

Source Code.

The eye’s mind

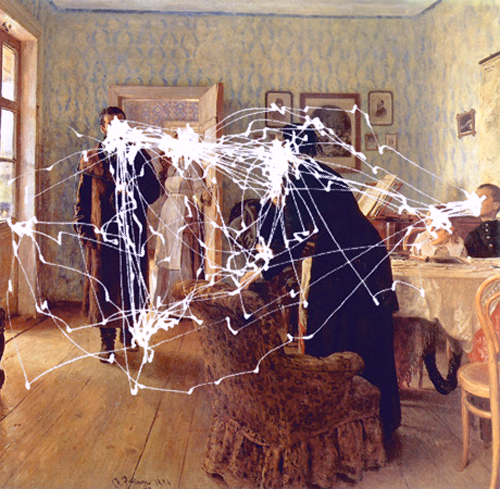

Sasha Archibald, after Alfred Yarbus, after Ilya Repin, They Did Not Expect Him (aka An Unexpected Visitor, 1884).

DB here again:

One blog about eyes deserves another–actually a couple more. These entries, however, won’t be about actors’ or characters’ eyes. They’re about yours and mine.

We use them when we watch movies, but there’s been surprisingly little talk about how we do it. Even film theorists who talk about the Gaze or Visual Culture have not devoted much time to studying how we actually see movies. The whole business is pretty complicated, I grant. But if you’re willing to start by thinking about how we use our eyes in getting through the world, and then move to thinking about how we look at pictures, we can pretty quickly gain some understanding about how we watch films. That’s the business of this entry and the next one.

Bottom-up or top-down?

Unless you’re reading this in a cyclotron or on a roller coaster (always a possibility in these days of mobile media), your surroundings seem pretty stable, no? Look up from your screen and you’ll register the continuous space of a room, or a city vista, or a landscape. What’s remarkable is that this sense of a visual environment that’s all of a piece is composed of thousands of probes. Our eyes sample our surroundings, and the pieces that we snatch somehow melt into a solid, coherent world.

Surprisingly, our eyes have a very limited ability to focus precisely. The fovea, that compact scoop of cells that registers fine detail, is very tiny (about a millimenter in diameter) and has an angular coverage of less than two degrees. Yet it’s a key conduit of information. About 50% of visual nerve fibers are dedicated to the fovea, and acuity falls off very fast beyond it. Other areas of the eye can detect grosser changes in the environment, but in order to see anything clearly, we must constantly shift our eyes to bring the fovea to bear on it. When we follow a moving object, our eyes execute what are called smooth pursuit movements. In viewing a more or less static visual array, we execute saccades, very fast jumps from one fixation to another. Vision is a matter of saccades and fixations, scanning and sampling. A striking fact about saccades is that from one fixation to the next we are mostly blind to what’s happening in the visual field.

But what guides that scanning and sampling? We usually think it’s a matter of attention, and that’s probably not far off. It’s hard to pay visual attention to something that isn’t the target of foveal fixation. When we examine something in detail, we’re clearly devoting mental resources to it, whether it’s a streaky tulip or a misplaced comma. But what triggers our attention, and thus our foveal activity, in the first place?

Commonly we say that something catches our eye, cries out to be noticed, grabs our attention. That is, something out there becomes salient, so we send a saccade to it and fixate on it to get information. This is what psychologists call a bottom-up account. A stimulus triggers our visual system, which in turn recruits our mind to make sense of what has popped out.

An example: Looking straight ahead, you’re starting to cross a street. Something registered on the periphery of your vision seems to be suddenly bearing down on you. You turn your head and look: a car isn’t slowing down for the stoplight and you involuntarily jerk yourself back out of harm’s way. The errant car was salient, your visual system kicked in, and your body obeyed—all in a flash. You might not even be able to identify the car or driver as it runs the light, and you might say: “I didn’t even have time to think about it.” This is bottom-up, stimulus-driven seeing and acting.

Contrast another way to use your eyes. You’ve parked your car outside the Mall of America. Hours later you come out, a little uncertain about where the car is. Once you get to the general vicinity you recall, you use your knowledge of the vehicle to search it out. Let’s see, silvery Toyota sedan. Hell, too many Toyata sedans, all silvery. Wait, mine has a faded Obama-Biden sticker on the bumper and a rabbit with glowing eyes in the back window. Aha, there it is. This is a mode of looking guided by ideas and prior knowledge. Here perception is top-down, idea-driven; vision is informed by what you expect, recall, or believe about the world.

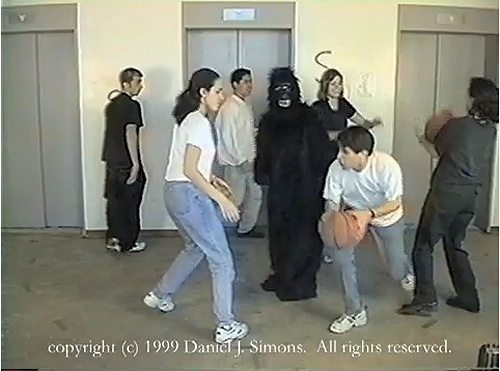

Top-down perception can focus our attention so drastically that we miss some glaringly obvious things. Consider Dan Simons and Chris Chabris’s famous basketball video experiment. If you’re not aware of this demonstration, proceed immediately to this page and take the test yourself.

Using a video of several players passing basketballs to one another, Simons and Chabris asked volunteers to silently count the passes made by players in white. But what Simons and Chabris were really testing was the extent to which people display “inattentional blindness.” About half the viewers were so preoccupied with the task assigned that they missed a rather salient item in the display: a gorilla that walks onto the court, thumps its chest, and walks off.

Simons and Chabris weren’t concerned with tracking eye movements (though later researchers have tried with the video; see the end of this piece). What the gorilla experiment indicates, however, is that top-down control has the drawback of narrowing our attentive focus so drastically that we miss the obvious. The curious phenomenon of inattentional blindness has become a robust area of research in cognitive psychology.

They did not expect…what?

We might think that visual search like the one demanded by the gorilla experiment is a special case. Isn’t most looking, including those saccades we execute all the time, bottom-up? After all, we are fairly passive, and we must take what we’re given by the world around us. Our attention is drawn to what pops out. There are a lot of features of the world that seem salient—bright colors, movement, strong contrasts, things coming toward us, and so on.

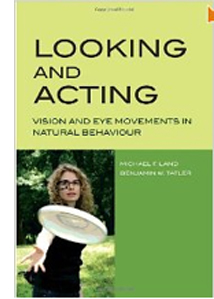

There’s another school of thought, though, and it’s articulated carefully in Michael F. Land and Benjamin W. Tatler’s Looking and Acting: Vision and Eye Movements in Natural Behavior (Oxford University Press, 2009). In ordinary life, they argue, we don’t just float though the world. We’re taken up with tasks. We walk, read, and make sandwiches. The tasks we undertake tacitly shape how and where we look and what we see. Land and Tatler want us to remember the top-down guidance of vision—the mind in the eye, so to speak.

There’s another school of thought, though, and it’s articulated carefully in Michael F. Land and Benjamin W. Tatler’s Looking and Acting: Vision and Eye Movements in Natural Behavior (Oxford University Press, 2009). In ordinary life, they argue, we don’t just float though the world. We’re taken up with tasks. We walk, read, and make sandwiches. The tasks we undertake tacitly shape how and where we look and what we see. Land and Tatler want us to remember the top-down guidance of vision—the mind in the eye, so to speak.

Their central chapters trace how our acts of looking serve two basic functions: “finding and identifying the objects needed for the various tasks and guiding the actions that make use of these objects” (p. 59). In reading and drawing, or even walking or hitting a ball, the authors show, our eyes serve our brain’s sense of what must be done moment by moment. Wearing a nifty lightweight eyepiece or pair of spectacles, the experimental subject can act quite naturally and allow her point of gaze to be tracked and recorded to video. The results show that the tasks we launch, from crossing a street to reading a piece of music, create a series of phases that our eyes recognize and help us through, all without much conscious effort.

What about pictures? We aren’t interacting with them in the way we interact with teacups and steering wheels; we can’t affect their unfolding. Do our eyes behave as they do in our ordinary activities? In 1965 the Russian psychologist Alfred Yarbus reported the results of experiments that tracked eye movements. In some of them, he used Ilya Repin’s classic painting They Did Not Expect Him (aka An Unexpected Visitor, 1884). The dramatic image depicts a hollow-eyed man, gaunt and wrapped in a patchy coat, striding into a comfortable middle-class parlor.

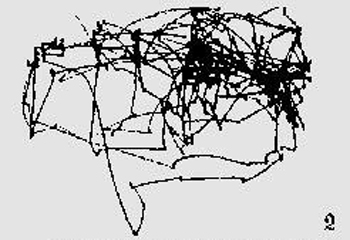

First Yarbus simply let his subjects view the picture without any instructions from him. Their saccadic patterns were typified by this subject’s result.

Each line represents the fast movement of the eyes from one location to another (saccades) and clusters of lines are the traces of fixations. The denser the lines, the longer and more often a point was fixated. Sasha Archibald’s reconstruction at the top of this entry superimposes this pattern on the original picture.

Then Yarbus tried asking his subjects questions about the image. Here is the result of his asking one subject to estimate the material circumstances of the family.

A very different trajectory of attention emerges. Now the scanning was more purposeful, and it focused on the areas most likely to fulfill the task of identifying the family’s social class–clothes, the piano, the children, and other items. Moreover, when given more time to examine the picture, subjects did not roam around every cranny of the frame but returned constantly to the areas they had already examined, the ones that were most relevant to the task. Hence the blotchy areas, which are nodes where the eyes fixated very often.

Artists often claim that color, composition, and other features attract a viewer’s attention. But Yarbus concluded that while some sorts of visual material, chiefly faces and bodies, were targeted during the undirected scanning, many other features, such as color, edges, light or dark regions, and so on were not. “The character of the eye movements is either completely independent of or only very slightly dependent on the material of the picture and how it was made. . . . Depending on the task in which a person is engaged, i.e., depending on the character of the information which he must obtain, the distribution of the points of fixation on an object will vary correspondingly” (pp. 190, 192).

Your mission in watching a movie

Generally speaking, in blocking and framing a shot, the most important thing is to make sure the audience is looking where you want them to look.

Robert Zemeckis

Like painters, film directors talk of guiding our attention, isolating this actor, throwing one plane out of focus in order to emphasize another one. And we commonly say that the movie is designed to grab our eyes and guide them through each shot. As Zemeckis’ remark suggests, directors direct actors but they also direct us; they direct our attention, and they do it by making certain things salient in each shot.

Or so we think. If Yarbus and Land and Tatler are right, are we deeply wrong about how movies work? I don’t think so, but convincing you requires that I unpack some assumptions.

First, the world doesn’t come to us in a frame. A film shot, like a still photo or a painting, is bounded by edges, and as Rudolf Arnheim and Jean Mitry have pointed out, the very existence of the frame inevitably organizes what is put inside it. It makes little sense to say that something is in the center of your visual environment—that depends on where you’re looking—but everyone will agree what is in the center of a picture. And we are very likely to look at that central area of a frame or screen; Land and Tatler call it a “bias” (p. 39).

Repin took advantage of this bias by composing the primary action around a central region. It’s not the geometrical center of the image, which falls on a fairly innocuous patch of gray near the elbow of the woman seated at the piano. But there is a cluster of heads and shoulders just above that center. Fans of the “rule of thirds” will point out the glances of the man, the women in the background, the woman at the piano, and the rising woman lie along a line marking off the top third of the picture. The frame, by being a certain shape, creates lines of force within the image, and these can attract our scrutiny.

Second, human faces are a special case. We are sublimely sensitive to them. Faces are recognized even in low-resolution images, they are detected faster than other configurations, and we readily project them into ambiguous patterns. Hence we see the Man in the Moon and the Savior on a Cheeto. Naturally, artists realize the power of faces and gestures to attract our attention. Repin’s compositional design facilitates our pickup of the human drama he presents.

Filmmakers follow suit. Knowing that faces and movements are zones of high information, directors light, frame, compose, and edit their shots so that these zones get highlighted. Indeed, we might say that today’s “intensified continuity” style of filmmaking, emphasizing singles and facial close-ups, goes with the flow, giving us a full dose of what we’d look for anyway.

Yarbus stresses the all-over quality of undirected vision, at least when compared with more specific tasks. But I’d say that the scanpaths we find in his free version line up pretty well with Repin’s compositional pattern and the pictorial roles he gave to faces, bodies, and gestures. True, there is a lot of visual search in unrewarding areas. Nonetheless, that high, slightly sloping area above the geometrical center attracts heavy traffic, as does the daringly edge-centered children on the far right. It is simply the line of least resistance, at least when all other considerations are equal.

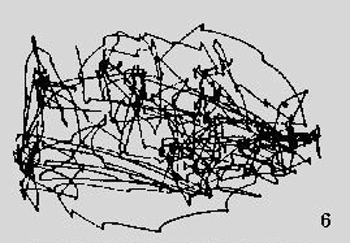

Yarbus made other things unequal. He asked questions, which created more guided paths. Still, regardless of what task they were assigned, Yarbus’ informants seem largely to have followed the compositional path Repin laid down. Asked to estimate the ages of the people in the picture, viewers gave a tighter, simplified version of the default, undirected path. To determine ages, face and height matter; the left window and furniture didn’t have to be explored much. Here is one subject’s pattern of scanning for signs of age.

Asked to memorize the costumes, the subjects also stuck to the program, with more searching of the body areas. Here is one example.

And asked to estimate how long the visitor had been away from the family, another viewer’s gaze traces a comparably tight slope, dwelling especially on the children at the far right.

In short, Yarbus’s questions about age, clothing, and years of separation were best answered by the faces and bodies on display–exactly the areas highlighted by Repin’s composition, color, and ensemble staging. Unsurprisingly, however, if your task is to estimate the family’s wealth, you’ll probably roam to the periphery of the action, as one subject did.

And if you’re told to memorize the spatial layout–a very unusual task that you’d seldom impose on yourself–you will spread your net quite widely, as one viewer did.

Yarbus’ results suggest to me that representational pictures elicit a set of default strategies: Start from the approximate center of the format. Watch for faces and gestures and an exchange of looks. Then launch further exploration of the picture space, anchoring that to the main compositional vectors and human signals. And of course take the title into account. The “they” of They Did Not Expect Him (virtually a literal translation of the original Russian title) prompts us to look for the reactions of onlookers.

With film, of course, we have additional pointers: sound, especially dialogue; camera movement, which is constantly redirecting our attention; and figure movement, which is a powerful eye-catcher. All things being equal, these channels of information will usually work in tandem with composition and the human signal patterns at work in a scene. Most films can be thought of as massively redundant systems for drawing our visual attention to certain items in the frame, second by second.

Story as task

One more point. Most of the factors I’ve mentioned involve bottom-up cueing. If in ordinary life our saccadic probes are governed by top-down task assignment, what about still images or moving pictures? Are there no task dictates at work? I think there are.

Recall most of the questions that Yarbus asked his viewers: the figures’ ages and clothing, their activities before the man entered, the family’s material circumstances. These are relevant to the tale the painting tells. It’s what we call a narrative painting, and most of Yarbus’ pointers are addressed to filling out the story.

The story may not be obvious to us today, but most commentators seem to agree that image represents a political exile returning from a labor camp to his family. The woman rising in the foreground is his mother, while his wife can be seen stirring from her place at the piano. His children are on the right, and many commentators interpret the somewhat fearful or puzzled expression on the little girl to indicate that she is too young to remember him. The image developed out of Repin’s sympathy for Russian radical movements of the time, and it was widely circulated by the later Bolshevik regime. Very likely Yarbus’s subjects would have seen the picture before and known the story behind it.

The point I want to make is that we do take on tasks when we watch a film image. Perhaps the most basic one is maintaining our interest, seeking out something that will keep our attention engaged at a basic level. But one major way to achieve interest is to make an effort to grasp how what’s happening onscreen develops the story.

Once the movie has started, we know who the main characters are and thus whom to watch most closely in ensuing scenes. We know something of their minds and motives, and we are sensitive to anything that impinges on those matters. So our top-down hypotheses about what’s going on and what will happen next shape what we look at and when we look at it.

Since story comprehension is one of our primary tasks in watching a mainstream movie, we will tend to ignore other things. We will miss changes in objects’ position across cuts (“cheats”) and disparities of lighting from shot to shot (e.g., the opening office scenes of The Godfather). These would seem to provide equivalents for the invisible-gorilla effect, although bottom-up factors are at play in such cases as well. Alternatively, when we don’t have any narrative expectations, as when we’re confronted with a lyrical avant-garde film by Stan Brakhage or Nathaniel Dorsky, perhaps we will let our eyes roam around the images more freely. Confronted by a film that denies us a narrative, we attend to composition, color, and other qualities that we may not notice in most storytelling cinema.

I’m convinced that research into vision is important to understanding film, but I’m a duffer at this. Next time, we hear from Tim Smith, a sort of modern-day Yarbus who monitors how we watch movies. An early example of his work is here, but next time we’ll catch up with his recent efforts.

Yarbus’s book is Eye Movements and Vision (New York: Plenum, 1967). It is rare and expensive, but a pdf is available online here. Google “Yarbus” and “Repin” together and you will find a great many research articles on eye movements and imagery. I’m grateful to amonseuldesir’s sitefor providing sharper diagrams of Yarbus’ result than I could squeeze out of my copy of his book.

Sasha Archibald has made a valiant effort to map Yarbus’ reported results onto the painting, as indicated in the image at the top of this entry. I thank Cabinet magazine for permission to reprint her schema. Thanks as well to Maria Belodubrovskaya for confirming the correct translation of the painting’s title. She recalls that in school she and other children were asked to discuss the reactions of the family portrayed in the painting.

For more on Dan Simons and Chris Chabris’ work, see The Invisible Gorilla and Other Ways Our Intuitions Deceive Us. Daniel Memmert has performed eye-tracking experiments with children watching the gorilla video. (See “The Effects of Eye Movements, Age, and Expertise on Inattentional Blindness,” Consciousness and Cognition 15 [2006], pp. 620-627.) Surprisingly, Memmert found that many subjects who fixated on the gorilla during the video still didn’t claim to notice it! Simons and Chabris use this finding to suggest that even fixations don’t guarantee awareness. It seems that fixation is a necessary but not sufficient condition for noticing something; once more, the task at hand can block out even things that we can see clearly.

Related to inattentional blindness is “change blindness.” As I mentioned in an earlier blog, Dan Levin, who worked with Simons, has explored how our inability to detect changes in images or in the real world can affect our understanding of edited scenes in films. Tim Smith has further studied “edit-blindness” as a cinematic parallel to change blindness.

Robert Zemeckis’ remark about guiding the viewer’s eye is quoted in Jay Holben, “Sole Survivor,” American Cinematographer 82, 1 (January 2001), p. 40. For more on that idea, see the opening chapter of my Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. More broadly, I discuss cinematic experience, and especially story comprehension, as an interaction of top-down and bottom-up factors in Narration in the Fiction Film and the first chapter of Poetics of Cinema.

THE SOCIAL NETWORK: Faces behind Facebook

DB here:

What do John Ford, Andy Warhol, and David Fincher have in common? Eyeball these remarks.

Ford, asked what the audience should watch for in a movie: “Look at the eyes.”

Warhol: “The great stars are the ones who are doing something you can watch every second, even if it’s just a movement inside their eye.”

Fincher, on the big club scene in The Social Network: “What’s cinematic are the performances . . . . What their eyes are doing as they’re trying to grasp what the other person is telling them.”

It isn’t just cinema that makes eyes important. Eyes are felt to be significant in literature, from the highest to the lowest. In just a couple of pages of a pulp adventure story you can read these sentences:

“Then it certainly does look very mysterious,” he said, but his blue eyes were quiet and searching.

Chief Inspector Teal suddenly opened his baby-blue eyes and they were not bored or comatose or stupid, but unexpectedly clear and penetrating.

What do quiet eyes look like, actually? Or searching ones: perhaps they’re moving a bit? Bored or comatose eyes might be droopy, so let’s count the eyelids as part of the eye. But what could make eyes, by themselves, penetrating? Nonetheless, we think we understand what such sentences mean.

Watching eyes is tremendously important in our social lives. We need to monitor other people’s glances to see if they are looking at us. We need to track what else they might be looking at. We need to watch for signals sent by the eyes, particularly attitudes toward the situation we’re in. For example, we seldom look directly into each others’ eyes, as characters in movies do constantly; in real life, “mutual gaze” is intermittent and brief. But if two people stare intently at each other, we’re likely to assume keen attraction or rising aggression.

In an essay from Poetics of Cinema available on this site, I talk about mutual gaze in cinema and how it can be exploited for dramatic purposes. The same essay takes up the issue of blinking; we blink frequently, but film characters seldom do, and the actors usually make the blinks emotionally expressive (of fear, uncertainty, weakness, etc.).

The problem is that eyes, by themselves, tell us very little about what the person behind them is thinking or feeling. We can show this with a little experiment.

Do the eyes have it?

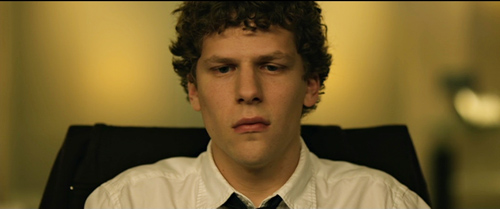

What do these eyes tell us?

Certainly they give us information–about the direction the person is looking, about a certain state of alertness. The lids aren’t lifted to suggest surprise or fear, but I think you’d agree that no specific emotion seems to emerge from the eyes alone.

So what happens if we add eyebrows? (I’ve tipped the one above to conceal the brows; now you get to see the face’s proper angle.)

Now there’s a degree of surprise. The brows are lifted somewhat. But still the emotion seems fairly unspecific: not particularly sad or angry or distressed; probably not joyous either. Then what?

I’d call this dazed, slightly perplexed surprise. The sloping brows suggest the man is trying to figure out what’s happened; but the mouth is a slight gape. You can almost imagine the lips murmuring: “Ohhh,” or “Wow,” and not in appreciation or pleasure. If you wanted to show someone being blindsided, this is a pretty precise way to do it.

Of course context helps us a lot. Eduardo Savarin has just been gulled by his partner Mark Zuckerberg and by the interloper Sean Parker. His stock in the company that he co-founded is now worthless. So the situation informs our reading of Eduardo’s expression, and this permits the actor to underplay. Actor Andrew Garfield doesn’t give us bug-eyed surprise or frowning bafflement; he relies on our understanding of what he must be feeling (what we would feel) in order to refine and nuance his expression. When an actor underacts, we’re often expected to fill in the emotions we could plausibly imagine him to be feeling, on the basis of the story at this point. In isolation, the expression might be vague or ambiguous; the narrative situation helps sharpen it.

Back to the main question: How informative are the eyes alone? Try this one.

Again, I’ve tipped the shot a little to conceal the brows. Not much evident from the bare eyes, is there? Again, a certain focus and interest, but that’s about it. No marked surprise or fear or sadness.

Something has been added. The brows aren’t lifted in surprise or fear or sadness or distress; they seem to be relaxed. The angle of the look suggests concentration, but we’re not getting as much information as we got from Eduardo’s brows. We need a mouth.

The impression of concentration is greater, and I think we’d agree that this small smile of satisfaction gives us some insight into what the character is feeling. Again, the eyes tell only part of the story.

And again context matters. Mark Zuckerberg has just figured out that he can enhance The Facebook by adding users’ information about their romantic relationships. The tight, sidelong smile confirms not only his genius but also his view that college is partly about getting laid.

Less with the eyebrows

At this point you might be getting impatient with me. Isn’t this all obvious? Of course the actors use their faces–they’re paid to do that. But sometimes going obvious can get us to notice things.

For one thing, the eyes in themselves aren’t that emotionally informative. Pupil dilation can convey physical arousal, but that’s another story for another time. More commonly, the eyes give us the all-important information about what the person is looking at. The lids convey alertness, or drowsiness, or if they’re pinched a bit, concentration or anger.

Sometimes the eyes give us all the information we get. Here is Mark just before he agrees to take the job coding for the Winklevoss brothers’ project, The Harvard Connection. He moves from alertness to calculation by narrowing his eyes. As the phrase goes, you can hear the wheels turning.

Crucial to this moment is that nothing but Mark’s eyes and lids move; he doesn’t even turn his head. At the film’s climax, he will open up a little bit, and the eyelids play a central part. Getting the news that the Facebook party has been busted, Mark starts to breathe more laboriously, then wobbles his head slightly and closes his eyes. For once his concentration is broken.

It’s about as close as Mark comes to a canonical expression of sadness.

Obvious as it seems, by isolating the eyes we can notice the division of labor among eyes, eyelids, brows, and mouth: Each component supplies a bit of information. We’re remarkably skillful in integrating all these cues. What researchers into face perception call the informational triangle–the two eye regions tapering down to the mouth–creates a package of social and psychological signals. It’s this whole ensemble, the most informative parts of the face working together, that guides us in making sense of other people, or of film acting.

I’ve come to especially appreciate eyebrows. Daniel McNeill, in The Face: A Natural History, writes:

The eyebrow is the great supporting player of the face, and its work generally escapes notice. It helps signal anger, surprise, amusement, fear, helplessness, attention, and many other messages we grasp almost at once. Indeed, without eyebrows the surprise expression almost disappears. The eyebrows are such active little flagmen of mind-state it’s amazing anyone can wonder about their purpose. We use them incessantly (p. 199).

Since eyebrows are so important, actors must control them carefully. In the film’s first scene, Erica Albright moves her eyebrows vivaciously (and widens her eyelids too), but Mark’s brows are rigid and knit together.

This scene introduces us to Mark’s facial behavior. He will glance to the side when he’s pressed, but he’ll focus sharply on the other person when he’s trying to dominate the conversation. His mouth seems to be ruled by the triangularis and mentalis muscles, creating the inverted smile sometimes called the “facial shrug,” even when the lips are relaxed. Erica smiles a lot, something that usually triggers a responding smile. But not from this guy, though a smirk will occasionally flit over his mouth when he says something insulting. The closest we get to a true smile, I think, is at the blowout conclusion of the contest for internships, and that’s seen in the fairly distant long shot at the top of this section.

Above those eyes and that mouth sit those hooded brows, almost never lifting or lowering. Which is to say that Mark seldom shows surprise, and his anger will usually be visible in the set of his mouth (and in his words.) His flatlined brows sometimes suggest keen concentration, sometimes aloofness when he tilts his head back, or more pervasively the sense that everything in the vicinity is irritating. He seems to be permanently scowling, an effect that Fincher and DP Jeff Cronenweth accentuate by lighting that draws his brows closer together and hollows out the eye sockets.

How different this performance is from the actor Jesse Eisenberg’s everyday facial configuration (or at least the one he employs to send us other signals) can be seen in the making-of documentary accompanying The Social Network on DVD. One example surmounts this entry and shows a much different set of expressive cues–raised eyebrows, wider eyes, more cheerful mouth. The actor’s face is very mobile; he can even turn in the inner corners of his brows, which is hard to do voluntarily.

In one section of the making-of, Jesse reports that Fincher was often telling him, “Less with the eyebrows,” and onscreen Eisenberg delivered. By the end, for the last shots of Mark alone, Fincher asked for what’s become famous as the Queen Christina effect–an expression that could be read in many ways. “I want everybody to put anything on it.”

The result is a portrait of Generation Whatever, or an image of stoic loneliness, or of bemused curiosity about an old girlfriend, or. . . .

One more consequence of my noting the obvious: The centrality of faces to modern movies. Today’s films use close-ups very heavily, probably more than at any other point in film history. (The Way Hollywood Tells It explores some reasons why.) What I’ve called the “intensified continuity” style of modern cinema relies on tight single shots of individual players.

So modern players must be maestros of their facial muscles and eye movements. In other styles of filmmaking, currently and historically, the actor’s performance is projected onto more body parts through gestures, stance, gait, and the like. Recall Cary Grant, who performed with his whole body. Of course he wasn’t bad in close-ups either.

Faces aren’t everything in movies like The Social Network. Most characters use their arms and hands freely–probably the Winklevi the most. Mark is straightjacketed, but even he will gesture sometimes, as when a drooping Twizzler becomes his hand prop. He usually prefers a shrug, though it’s executed without the eyebrow lift most people add. Postures and personal walking styles play key roles in the film as well.

Still, as in most movies today, here eyes and brows and mouths are the main channels of emotional information. Fincher again: “It was really a movie about kids’ faces.” And even films from the 1910s, made before directors used a lot of cutting, often used long-shot staging to direct attention to the body’s most informative zones. A 1913 book on film acting noted, “Facial expression is perhaps the most important part of photoplaying. . . . After all is said and done the eyes are really the focus of one’s personality in photoplaying.”

Facebook facework

I can’t offer a complete account of nonverbal behavior in The Social Network here, but I want to end with a hypothesis that would be worth more detailed inquiry. The film’s central relationship is that between über-nerd Mark and Econ-major Eduardo, the coder and the aspiring tycoon (although he also supplies Mark with a crucial algorithm). Through facework, Fincher and his actors delineate the contrasting personalities and trace their shifting dynamic.

From the start, we get Mark’s stare of frowning concentration, drawing on the muscle called the corrugator, Darwin’s “muscle of difficulty.” By contrast, Andrew Garfield’s performance is marked by a look of worry and abashment. He’s often kinking his eyebrows, furrowing his brow, and ducking his head. Fincher motivates this behavior by having him often stoop over Mark’s workstation, tilt his head downward, and lift his eyes from underneath his brow.

In this shot/ reverse-shot passage, Mark’s mask never slips but Eduardo, wrinkling his brow and tipping his chin down a bit, looks apologetic.

Even when Eduardo has every right to berate Mark, he looks like he’s the one in the wrong. Instead of displaying the jammed-down, pinched-together brows of an angry man, he won’t lose his patient, slightly anxious look.

See the last image on this entry for a moment when Eduardo seems on the verge of tears–and this is after he’s gotten an invitation to join two alluring women.

You can argue that the blindsided expression we dissected earlier is one culmination of the facial cues that Andrew Garfield has been blending in the course of the film. But things are more complicated. The plot gives us two forward-moving timelines, one in the past tracing the rise of Facebook, the other in the present, during which Mark is deposed in two lawsuits. At an early deposition, Mark’s implacable stare works to make Eduardo revert to his old obeisance.

But in a climactic face-off, we come to see a different Eduardo.

Eduardo’s quiet testimony about whether anyone’s share but his was diluted (“It wasn’t”) affects Mark more deeply than the bluster of the Winklevoss brothers. The words are delivered without the usual sidelong glance, kinked eyebrows, or head ducking that has defined Eduardo earlier. His brow is smooth, his brows level. This is man to man, and it’s Mark who breaks off eye contact.

You could nuance this transformation by tracing it scene by scene, and contrasting it with the body language displayed by other characters. For today I simply wanted to sketch the broad development that I think is at work in this core relationship. The drama of domination and betrayal is played out in eyes, eyebrows, mouths, mutual gazes, and the like as much as it is in the dialogue and incidents.

There is no art, Shakespeare’s Duncan says, to read the mind’s construction in the face. He’s right about the reading part; we grasp expressions fast, intuitively, and often reliably. But there is art in the performer’s construction of the face, and of the director’s cinematic shaping of it.

John Ford’s remark about looking at the eyes is quoted in Joseph McBride’s Searching for John Ford (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010), p.2; the Warhol quotation comes from Andy Warhol and Pat Hackett, POPism: The Warhol ’60s (New York: Harper and Row, 1980), p. 109; quotations from David Fincher come from the bonus features on the collector’s edition DVD of The Social Network. My quotations about eyes in fiction are drawn from Leslie Charteris, Prelude for War (New York: Doubleday, Doran, 1938), pp. 171, 173. The 1913 quotation about eyes comes from Francis Agnew’s Motion Picture Acting (Syracuse: Reliance Newspaper Syndicate), p. 40; I learned of it from Janet Staiger’s article, “‘The Eyes Are Really the Focus’: Photoplay Acting and Film Form and Style,” Wide Angle 6, 4 (1985), pp. 14-23.

Ed Tan offers a very good analysis of the issues I mention here in his article “Three Views of Facial Expression and Its Understanding in the Cinema,” in Moving Image Theory: Ecological Considerations, ed. Joseph D. Anderson and Barbara Fisher Anderson (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005), pp. 107-127. I find Vicki Bruce and Andy Young’s In the Eye of the Beholder: The Science of Face Perception (Oxford University Press, 1998) a very helpful guide to ideas in this research area. The “facial shrug” is described in Gary Faigin’s excellent The Artist’s Complete Guide to Facial Expression (New York: Watson-Guptill, 1990), pp. 104-105.

There’s a fascinating debate in the human sciences about whether particular aspects of nonverbal communication are constant across cultures. Gestures vary considerably, but are facial expressions universal to some degree? Or do they differ from culture to culture? Are they primarily expressions of the person’s emotion, or are they signals which have developed, through evolution or cultural convention, to influence others? You can read more about these and other issues in Paul Ekman and Wallace V. Friesen, Unmasking the Face (Cambridge, MA: Maor Books, 2003) and Alan J. Fridlund, Human Facial Expression: An Evolutionary View (San Diego: Academic Press, 1994). The classic account is by Darwin, whose 1872 book Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals is available in an edition in which Ekman includes an afterword explaining the development of this research tradition.

Up to the minute, more or less: Contemporary research on smiling and eye contact.

PS 2 February: Thanks to William Flesch for correcting my Shakespeare citation: I originally attributed it to Hamlet.