Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

Has 3D already failed? The sequel, part 2: RealDsgusted

Kristin here–

For part 1, see here.

Darn those quickie conversions!

In past years, 3D proselytizer Jeffrey Katzenberg, head of Dreamworks Animation, has complained about the slow progress of the conversation of theaters to digital and 3D projection. By September, 2010, faced with a growing backlash against the technology, he was more concerned about the conversion of films shot in 2D to 3D. The 3D Hollywood in Hi Def site reported:

Jeffrey Katzenberg opened the 3D Entertainment Summit with his usual provocative verbal flare [sic], defending 3D successes against the recent growing tide of critics claiming it is already dying — “It seems there are some in Hollywood who are determined to seize defeat from the jaws of victory. Six of the top 10 movies this year are 3D; I guess we have to have 10 of 10.” — and lambasting filmmakers and studios who convert movies to 3D after they are produced in 2D, calling them “downright ugly” and claiming they are endangering the technology that is single-handedly responsible for the industry’s growth in the past year.

On the whole the media were hardly sympathetic, perhaps because Katzenberg has been largely responsible for making 3D–including those 3D-ized films–so profitable. Patrick Goldstein of the Los Angeles Times called his speech a “desperation plea” and gleefully linked to several anti-3D articles, including some of the ones I’ve linked to in this and last week’s entries.

What Katzenberg didn’t point out was that some of the six films in the top ten were the same retrofitted ones that he was attacking: Clash of the Titans and The Last Airbender. Alice in Wonderland was shot in 2D, but planned with the knowledge that it would be converted to 3D. (Gulliver’s Travels had not yet demonstrated that retrofitted 3D doesn’t always make for big domestic BO.)

Yet about a month later, in an interview with the New York Times, the other most influential figure in the push toward 3D, James Cameron, was discussing converting a film released in 1997 and not planned with 3D in mind: Titanic. (He plans to release it for the 100th anniversary of the ship’s 1912 sinking.) For Cameron, conversion is a problem when it is done hastily and carelessly. Of the retrofitting of Clash of the Titans he remarked, “It was just being applied like a layer, purely for profit motive.”

One problem with converting a 2D film to 3D comes from the fact that the process is far from an exact science (or art). Cameron commented on his search for a company to handle Titanic:

These conversions are so painstaking to complete correctly, Mr. Cameron said, because “there’s no magic-wand software solution for this.”

He added: “It really boils down to a human, in the loop, sitting and watching a screen, saying, ‘O.K., this guy is closer than that guy, this table is in front of that chair.’ ”

For his 3-D “Titanic” rerelease, Mr. Cameron said he had approached seven companies about working on the film, testing each by asking it to convert about a minute of movie footage before he chose the best two or three efforts.

“All seven of the vendors came back with a different idea of where they thought things were, spatially,” he said. “So it’s very subjective.”

He also points out that studios will inevitably search their vaults for films to convert.

How does 3D conversion work? An invaluable issue of Screen International, “European 3D Special 2010,” explains in terms reasonably comprehensible to the lay person:

While each company goes about it slightly differently, the requirements are broadly the same: the creation of a second identical version (to obtain a second eye view) and the isolation of foreground from background elements by rotoscoping, adding depth and then painting or animating in the gaps. “When you move an image in this way to create two views, the biggest problem is filling in and cleaning up the area left behind,” says Vision3 post-production supervisor Angus Cameron. (From “Conversion: 2D to 3D,” p. 9)

(This issue, by the way, shows that studios doing conversion are popping up in Europe as well as in the U.S.)

As Cameron’s statements and this description suggest, the process is a painstaking, lengthy one. Many in the industry praised Warner Bros.’ decision not to release Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part l in a 3D conversion. The studio cited insufficient time before the release date as its reason. Cameron remarked, “You can’t do conversion as part of a postproduction process on a big movie, because no one is willing to insert the two or three or four months necessary to do it well.” (Of course, some foes of 3D may have suspected that the real reason for Deathly Hallows I being released only in 2D may have been that WB saw the declining share of the box office going to 3D and decided it just wasn’t worth it.)

Graham Clark, the head of stereography for the Stereo D company, claims that the conversion process can be done well as long as enough time is allotted for it:

“The main thing is this is an artistic process,” he said of conversion. “Composing things in 3D space is every bit as artistic as composing things in 2D space.” […]

“Because there are so many factors that go into deciding how to compose a shot, you need interaction with the producer, director, cinematographer—so you are not, at the eleventh hour changing things,” he said. “Also, visual effects studios are used to handing off [VFX elements] at the eleventh hour. Conversion is new in the film pipeline, and people aren’t used to having to hand stuff off earlier.”

Clark points out some of the ways that conversion could be used to enhance a film. If a 3D camera can’t be fitted into a certain space, a shot can be done in 2D and converted. If after a scene is shot the filmmakers want to shift the spatial relations of elements within it, they can do so—eventually, at any rate, since the techniques for doing that are still being developed. As Clark points out, films shot in 3D usually have some shots that are converted. Even Avatar included some. (See Carolyn Giardina’s “The art of the 3D conversion,” The Hollywood Reporter, October 29, 2010, pp. 6, 87. The same article, retitled “Expert: The Biggest Challenge in 3D Conversion,” is available here for subscribers.)

Given that most effects-heavy films these days face a major crunch to make their release dates and have to employ multiple effects houses to do the job, a quality 3D conversion can only add to the headache. Not to mention more work for the conscientious director and cinematographer who have to sit in on the decision-making to prevent the quality of their work from being diminished.

All in all, it looks as though 3D will not die out completely. But will there come a time when every screen in the world’s major markets will have the capacity to show 3D films? That was Katzenberg and Cameron’s original ideal, or so they said. Others had the same vision. Katzenberg has committed Dreamworks Animation to making only 3D films. Does he plan eventually to eliminate 2D prints altogether? Cameron claimed he would do that with Avatar, but he had to give in on that one.

Maybe Katzenberg and Cameron would object that they didn’t mean that literally every screen would be 3D. Yet advocates for 3D often compare it to sound or color or widescreen, all processes which did fully penetrate theatrical exhibition. In major markets sound took about three years (though places like Japan and Russia still made a few silent films into the mid-1930s). Widescreen took about six years. The most apt comparison is perhaps color, which didn’t become really viable until the mid-1930s; it remained somewhat rare into the 1940s and didn’t really become dominant until the late 1960s. But in our era of fast-moving technology, perhaps three decades from now 3D, at least in its current form, requiring glasses, will be a dead technology.

In my first entry on 3D, I mentioned that not very many producers or directors have been proselytizing for the process nearly as much as Katzenberg and Cameron have. Lucas is converting the Star Wars series, but he doesn’t promote the process with the fervor he once devoted to digital cinematography and projection and Dolby sound. Spielberg’s first 3D film, The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn, is coming out in December, but he’s not making the round of the trade fairs singing the praises of the process. The same is true of Scorsese and his 3D debut, Hugo Cabret, also coming in December.

Peter Jackson and Guillermo del Toro had originally stated that The Hobbit would be 2D, so as to keep a unified look alongside the Lord of the Rings trilogy. But when Warner Bros. finally greenlit the film in October of last year, the press release included the news that the two parts will be shot in 3D. Peter Jackson is a big booster of the Red brand digital cameras (used on The Lovely Bones and District 9), and he enthused briefly in the Red press release about using the new Epic 3D model for The Hobbit. His Weta Digital facility did most of the effects for Avatar. Still, he’s not out on the stump, urging theaters to convert and warning filmmakers not to retrofit their films, and many fans wonder whether Warner Bros. left him any choice in the matter of using 3D. (Vague statements have been made about the trilogy being released in 3D eventually, but there’s no firm news about that.)

Of course, assuming 3D is here to stay, there will always be bad conversions because there are bad instances of anything. There are shoddy-looking 2D movies and always have been. Still, the studios didn’t charge extra for them. There are and will be movies originally shot in 3D that are bad. People will have to pay extra for them, too, at least in the near future. Somehow, paying that premium 3D price seems to make people more indignant about bad movies than paying the regular price does. Studios are not likely to heed Katzenberg’s plea that they not crank out cheap 3D-izations. If such sloppy jobs as Clash of the Titans continue to come out and sour people on paying premiums, the studios may have to lower those premiums until they just cover the extra costs of production and of the glasses. If 3D ceases to generate any significant extra profit, will the studios bother with it?

Or will they take the more sensible approach that I mentioned at the beginning of the first part of this entry, settling for multiplexes converting two or three screens for 3D capacity and showing either special-event films like Avatar or cheap genre films like Piranha 3D? Part of that approach would include continuing to make 2D prints of films. There are quite a few viewers who would prefer that option.

At least one studio chief agrees. Last summer Home Media Magazine‘s article on Toy Story 3 reported: “Disney CEO Bob Iger, in a recent financial call, cautioned flooding the market in 3D releases, opting instead that earmarked titles in the format should be done strategically, and not as an afterthought.”

Before moving on to vociferous 3D opponents, I’ll mention a couple of intriguing, possibly significant things that I’ve noticed that may indicate a short life (or possibly a marginalized long life) for 3D.

First, on January 10, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences announced its scientific and technical awards. (Those are the ones that are given out at a separate ceremony and are given a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it acknowledgment during the Oscar ceremony.) These awards are often given for developments that occurred years earlier. On the other hand, major innovations tend to get honored fairly soon. The two technical awards given for special-effects programs for The Lord of the Rings were given in 2004, the same year that The Return of the King swept the Oscars.

This year’s awards include none relating to 3D. (For Variety subscribers, the complete list is here; so far they don’t seem to be listed on the Academy’s website.) Instead, they relate to such inventions as a new winch for flying heavy props like cars, a new suspended-camera mount, systems for queuing special effects for rendering, a method for facial-expression capture, and an innovative way of using bounce lighting in computer animation. Maybe it’s not significant, but it may give a clue as to the professional motion-picture technicians’ view of 3D.

Second, this past summer David and I were able to attend a trade demonstration at a local theater. The Technicolor firm had innovated a 3D add-on lens for 35mm projectors. Technicolor had seven Hollywood studios signed on, agreeing to provide analog 3D prints formatted in the system. (13 of the 19 films released in 3D in 2010, beginning with How to Train Your Dragon, were available on 35mm 3D prints.) The main appeal of the system was that distributors don’t buy it; they rent it by the year. The special silver screen needed for the technology would cost around $4000 to $6000 to install (and could be used for some digital 3D systems, including RealD), and the lens would be rented at $2000 per 3D film exhibited, with a maximum of $12,000 per year. In contrast, a digital 3D conversion costs at least $75,000 per house.

Some small-town exhibitors from the surrounding area were obviously intrigued. They couldn’t afford to convert to digital/3D, but this offered a cheaper option. Nobody mentioned it during the demo, but the other obvious implication seemed to be, if you just rent your equipment, you won’t lose out if the 3D craze fizzles out. The firm anticipated having over 500 systems installed in the U.S. by the end of 2010. (For a case of a theater in Decatur, Illinois that canceled its deal with Technicolor, see here; the management failed to understand that one has to charge higher admission for 3D tickets because the print rental fees and 3D system cost more, and the projectionist keeps referring to the 3D lens as a “camera.” On the whole, one can’t feel that in this case the Technicolor system itself was to blame. The 25 equipped screens out of the 150 in the Bow Tie Cinemas chain in California presumably have fared better.)

[Added later the same day: Skip Huston, who run Huston’s Avon Theater 3 in Decatur, tells me that the reporter was the one who called the lens a “camera.” (Knowing what it is to be misquoted by a reporter, I can well believe it.) The owners tried to avoid raising ticket prices for their customers, but that just doesn’t work with 3D. Mr. Huston’s theater is a mom-and-pop establishment competing with two Carmike multiplexes. Those wishing to avoid 3D have the option of 100% 2D at the Avon.]

Naysayers galore

The more I see of the process, the more I think of it as a way to charge extra for a dim picture.

Roger’s remark sums up the two beefs people have with 3D. Not surprisingly, when 3D was a novelty and only major films had it, people were willing to pay extra. Now that any multiplex will be likely to have one or two screens devoted to 3D movies at any given time, the premium has begun to seem onerous. And yes, the glasses do cut out a noticeable part of the light coming from the screen.

According to a report by PricewaterhouseCoopers (quoted in The Hollywood Reporter), “a $5 premium per ticket is too much to expect audiences to pay for 3D. That survey indicated that 77% of Americans will not pay a premium of more than $4.” In terms of the industry’s attitude, the report adds, “Many people are over-excited by it. The danger is that industry players risk killing a golden goose by overselling and, in some cases,  overpricing the 3D experience—and by providing too much mediocre content that doesn’t do justice to the technology.”

overpricing the 3D experience—and by providing too much mediocre content that doesn’t do justice to the technology.”

Putting aside the high price, there are those who actively dislike the process. Others admit that there are a few films that justify the use of 3D but that most films using the process released so far have been attempts on the parts of the studio to jack up the ticket prices. If these people are entertainment journalists, they use the forum of their reviews or columns to air their complaints. If they are ticket-buying audience members, they search out the 2D screens or stay home. Some of them blog about their complaints, others write letters to the editor, and others carp about 3D around the water cooler.

Roger Ebert probably has the highest profile of the anti-3D naysayers, as least among the general public. In an article in Newsweek (May 10), he laid out his objections:

3-D is a waste of a perfectly good dimension. Hollywood’s current crazy stampede toward it is suicidal. It adds nothing essential to the moviegoing experience. For some, it is an annoying distraction. For others, it creates nausea and headaches. It is driven largely to sell expensive projection equipment and add a $5 to $7.50 surcharge on already expensive movie tickets. Its image is noticeably darker than standard 2-D. It is unsuitable for grown-up films of any seriousness. It limits the freedom of directors to make films as they choose. For moviegoers in the PG-13 and R ranges, it only rarely provides an experience worth paying a premium for.

Roger goes through each of these reasons in more detail. He writes with conviction, and the studios would be wrong to think that he stands alone. I wonder how many other websites have linked to the online version of the essay. I see it quoted and linked a lot, even eight months after it appeared.

Movie City News critic David Poland, also far from being a fan of 3-D, recently posted an entry called “Will 2011 Be A 3D Car Wreck?” He assesses many of the roughly 30 3D films announced for this year. As he points out, similar films will be competing with each other during the key release seasons, as with Scorsese’s Hugo Cabret, the third in the “Chipmunks” franchise, and Spielberg’s Tintin movie, which are coming out within a short period. He concludes:

But the problem remains… 3D is a tool, not an answer. The problem that I expect next December, for instance, will be a parade of high quality films of a similar tone all piled up in on month. Same with the load of animation in November. And whichever films pay the price – and some films will – it won’t be 3D’s fault, but rather, overloading the marketplace. The franchises are franchises and the product that isn’t franchise will need to be sold smartly and heavily… just as in a world without any 3D at all.

This is an interesting variant on the view of 3D as a symptom of the film industry’s problems. Often popular commentaries link 3D mainly to the loss of audiences to TV, video games, and other new media sources of entertainment. But Poland sees the problem as more related to the increasing dependence on franchises and big event films. When other methods of luring patrons into theaters fails (Johnny Depp and Angelina Jolie together for the first time!), 3D remains a lure–except when it doesn’t, as with Gulliver’s Travels.

These days Entertainment Weekly seems to be mounting a campaign against 3D. Lisa Schwarzbaum makes no bones about her increasing disenchantment with the format. About a quarter of the prose in her December 15 review of The Chronicles of Narnia:Voyage of the Dawn Treader (C rating) is devoted to it:

And that includes the option of watching The Voyage of the Dawn Treader in undistinguished, unnecessary 3-D. I’m more and more frustrated these days by movies that sell the 3-D movie experience as a kind of turbo-charged event, yet the greatest extra we see through plastic movie-theater goggles is the ”dimensionality” of a sword or a boot or the imaginary fur on a CGI  mouse. I’m confounded by the fact that, aside from the Pevensie siblings and their nicely obnoxious cousin, absolutely everything and everyone aboard the Dawn Treader looks one-dimensional, no matter how closely I peer through special specs.

mouse. I’m confounded by the fact that, aside from the Pevensie siblings and their nicely obnoxious cousin, absolutely everything and everyone aboard the Dawn Treader looks one-dimensional, no matter how closely I peer through special specs.

It’s not just that one film, either. Schwarzbaum called Tangled (B rating) “Disney’s new (yet not quite novel), musical (yet not quite memorable), 3-D (yet so what) animated retelling of the Grimm brothers’ Rapunzel.” Of The Green Hornet (C-), she remarked, “In a last-minute tweak, the production has also been meaninglessly 3-d-ified–never mind that there’s nothing whatsoever 3-D-ish going on. Maybe those clumsy 3-D glasses are meant to let moviegoers mimic the superhero mask-wearing experience? At any rate, they let moviegoers pay more for a ticket.”

OK, she’s one critic. But note EW‘s back-page “Bullseye,” which shows what one or more people on the staff think of as recent hits and misses in the sphere of popular culture. For the week of November 11, , there was an arrow fairly close to the center with the caption: “Good news for 2012: Batman gets a title (The Dark Knight Rises). Better news for 2012: He won’t be rising in 3-D.” For the year-end Bullseye from the undated last issue of 2010, an arrow on the outer rim had a distinctly unsympathetic caption (see above). The January 21 issue places an arrow near the outer ring, labeled “All that talk of making The Great Gatsby in 3-D.”

Lest anyone think that EW has some hidden agenda in knocking 3D, we should note that the magazine belongs to Time Warner, whose Warner Bros. studio is deeply invested in the success of the format.

There’s also a great deal of anecdotal material about how parents are tired of paying multiple 3D surcharges when taking a whole family—and tired of finding that the kids won’t wear the glasses through the whole show. Dorothy Pomerantz is one parent with a soapbox from which to state her case, in the form of her “The Biz Blog” for Forbes. On July 13 she wrote:

We went to an 11 a.m. showing (for matinee prices) of Despicable Me and it cost us $41 for a family of four. If we had decided to see the film in 3-D, it would have cost us $55 for tickets alone. In my mind, that’s too much money.

For one thing, my kids are scared of the 3-D effects and wiggle so much in their seats it’s hard to tell if they’re seeing the image clearly at all (and my daughter has a very hard time wearing the glasses over her normal glasses for 90 minutes at a time). I find the glasses sit very uncomfortably on my face and that the movie image is often dim. For some reason my husband doesn’t see the 3-D well and ends up with a horrible headache.

People seem to think that children’s animation is ideal for 3D—but if a lot of young children don’t like the glasses or can’t keep them on, maybe that’s not true. (The image above right is not a warning against such problems but a promotional item for watching 3D Blu-ray on PlayStation 3. Apparently children will be seen and be heard.)

Apart from journalists, ticket-buyers are complaining. Back to EW, where the January 14 edition’s letters page (p. 10) had this from Courtney Holcomb of Grand Prairie, Texas:

I’ve read many articles discussing the trend that Avatar started … yet most of them miss a simple point. The film was available in both 3-D and standard formats. The customer had to decide “Do I want to see it in 3-D or not?” More recent 3-D movies have changed the question to “Is it worth it to see the movie in 3-D?” Many of the ones on the “Bad!” end of your “Ranking 3-D Movies” chart might have done better if the standard version had been available as well.

Actually the chart (see left) was by quality, not income, but Ms Holcomb’s point could apply to box-office hits and disasters alike. People who had no access to 2D versions of any film on the list might have decided to go. A friend of mine told me he didn’t see The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, despite wanting to, because it was only showing in 3D.

On the same letters page, Stephen Wohlleb of Sayville, New York, wrote:

While studio execs scurry to push out any film they can in 3-D, they must keep in mind that 3-D should be used to enhance the story, not replace it. The “other Avatar,” The Last Airbender, was so poorly received because story still comes first; 3-D does not a film make.

I have not ventured too far into the depths of chat rooms and comments on the internet for the purpose of writing this blog, but of course, there one can find vociferous pro and con statements on 3D.

I have a friend with vision problems and frequent headaches, and she actually finds the 3D glasses improve her viewing of films. That doesn’t seem to be common, though. Mostly the headaches and the kids-having-trouble-with-glasses complaints seem to be shared by many.

Industry commentators don’t seem to mention the novelty effect of 3D much any more. Surely they never really thought that audiences will be dazzled forever. I think we reached the ho-hum point some time last year. I’ve mentioned that people began to resent the $3+ price hikes and to pick and choose more carefully among 3D releases, wanting the movie to be good enough to warrant paying more. But others perhaps decided 3D in general wasn’t worth it and that they would rather see a film the old fashioned way, seeing a flat image undimmed by glasses.

For me it was Toy Story 3. In 2009, David and I saw Up in 3D and enjoyed it. But we enjoyed it because it was another great Pixar film. As I said in my 2009 entry, I have remembered the film in 2D. We went to Toy Story 3 in 2D and enjoyed it. I have yet to see a film in both 3D and 2D to make a comparison, but my suspicion is that I would usually prefer the 2D version. I suppose the basic problem is that if the 3D is used for flashy depth effects with things flying out at the audience, it becomes too distracting and obtrusive. But if it’s used simply to make, say, jungle plants look closer to the viewer than Carl and Russell, then it’s unobtrusive—and hence not very interesting. Given that we have other mental tools besides binocular vision for grasping the spatial relations in an image, the jungle plants look closer in 2D as well.

A final thought on disaffected audiences. Currently there is a sector of the moviegoing public that loves 3D, will pay extra to see almost anything in 3D, and hopes the process expands. That part of the public is probably as big as it’s going to get. (Yes, new kids will grow up, but others will mature out of their adolescent obsessions with such things.) In the U.S. at any rate, right now there aren’t a lot of people suddenly discovering the joys of this wonderful new format. (It’s really just getting going in the major Asian markets.) But the proportion of the getting fed up by the process’ drawbacks—its higher cost, the growing numbers of mediocre and bad films in 3D, the glasses—is probably growing.

Just in time for inclusion in this entry, Roger has posted a new article, “Why 3D doesn’t work and never will. Case closed.” It includes a letter from Walter Murch, who is about as well-respected an expert on film technology as you could find. The letter explains how 3D systems work in ways that are contrary to the ways that our eyes and brains actually function. He deals with strobing, the convergence/focus issue (“So 3D films require us to focus at one distance and converge at another.” That’s where people’s headaches come from in watching 3D movies.) Murch concludes: “So: dark, small, stroby, headache inducing, alienating. And expensive. The question is: how long will it take people to realize and get fed up?”

Perhaps not very long. I was expecting that in the wake of last week’s post I would receive indignant email and get flamed on message boards. So far I have seen no indignation. One thread on imdb that linked to the entry led to about ten comments, all expressing dislike of or indifference to 3D. Of course, that entry was on the “advantages of 3D” (such as they are) for the industry. Maybe this one will rouse more ire.

A 3D film even a naysayer can love

There’s one 3D film that even 3D disparagers eagerly want to see: Werner Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams. It’s the one where Herzog got exclusive access to film in the Chauvet cave, which contains one of the largest and oldest sets of prehistoric paintings. I would love to see the cave, but it isn’t open to the public. So naturally I would love to see Herzog’s film. (He’s not exactly a bad filmmaker, either, whatever the topic). It seems the perfect use for 3D: showing people exciting places they will never get to see on their own. I could imagine a similar film being made in the tomb of Sety I in the Valley of the Kings, a very deep tomb full of paintings considered among the best that survive from ancient Egypt. It will almost certainly never be open to the public either.

IFC acquired the film at the Toronto International Film Festival in September. They don’t seem to be trying to publicize it very much. No announcement on their site of when it’s going to be released, and the Google link to the official trailer comes up with a “Page not found.” I had to go to The Documentary Blog to find out that the release date is March 25, but the author had no information about how many theaters would get it in 3D. I should think IFC would make more of a big deal about this film as a real “event” movie. Maybe they will, closer to the release date. With operas and sporting events playing in multiplexes, I would think that there’s a considerable audience for 3D films that bring special events to a far-flung audience. Every kid whose imagine was kindled by learning about prehistoric cave paintings in school, every art lover, plus every cinephile, would attend Cave of Forgotten Dreams if it came to a theater near them.

Direction: Come in and sit down

Tampopo (1985).

There is what we call the Hollywood Style. . . . . Master shot [filmed] from the very beginning [of the scene] to the end, then a close shot from beginning to end, then from angles A and B, cutaways, et cetera. Then all of the materials are assembled later in the editing room. But in Japan, the editing plan is prepared before shooting. When you cut, it’s a matter of trimming heads and tails and just putting it together. Three days after the end of filming, there is a rough cut of the film.

Itami Juzo (The Funeral, A Taxing Woman).

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong 2 still on the way…. very close to ready…. deciding among cover designs…. soon; sooner if possible….

In the meantime, some creative choices involved in directing a simple scene.

Shanghai’d

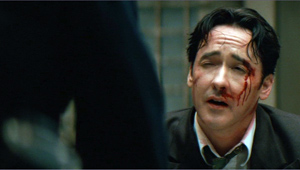

What could be easier than getting a man into a room and sitting him down? The opening scene of Shanghai (2010) seems to me to bungle this basic piece of tradecraft.

In the image above, journalist and spy Paul Soames is being beaten up by the minions of Captain Tanaka. Who’s the poor sod who has to hang those big flags so high in movie torture chambers like this? Anyhow, soon the torturers drag Soames up the stairs, likewise in long shot, to meet the captain.

A brief shot of a door opening seems to put us in Soames’ shoes. But that viewpoint isn’t carried through consistently: we cut abruptly to the other side of the door, to a long-lens medium shot of Tanaka opening it.

Soames steps forward and is greeted by Tanaka.

Now comes the establishing shot, from quite far away, as Soames walks to the desk. This shot is interrupted by cutting back to the shot of Soames moving forward.

As the shot continues, Soames sits down and looks up. Throughout the scene, this setup will be assigned to cover Soames, with the camera panning and reframing as necessary.

Counting the swinging-door shot, it has taken four shots to get Soames into the room. But the actors aren’t yet fully in place. As Soames turns his head, Tanaka (back to master shot) moves around on Soames’ left side. The phone starts ringing.

Tanaka begins to halt at his desk, but before he stops moving we cut again to Soames, whose attention has shifted to the phone. He has asked that his embassy be notified, and now he suggests that it’s the embassy calling.

Cut to a close-up of the telephone, the object of Soames’ attention, and another shot of Soames, as before, as he looks expectantly back at Tanaka.

Now we have a closer shot of Tanaka, still slightly moving, and we catch his disdainful expression.

After Tanaka lifts and drops the receiver to cut off the call (another close-up), he settles into place. The rest of the conversation is played out in those loose over-the-shoulder shots that modern directors like so much.

Throughout, the shots of Soames seem to be from the same camera setup as when he entered. No repositioning of the camera marks stages of his part in the conversation, though at the end of the scene a pair of close-ups shows Tanaka asking, “Where is she, Mr. Soames?” Cue the flashback.

It’s not just that it took director Mikael Håfström over a dozen shots to get Soames and Tanaka into position for their central duet. Hitchcock might use several shots too. But each of his would be calibrated for specific expressive effects, such as subjective point-of-view treatment or a striking composition. Instead, the Shanghai shots exemplify a fairly casual cover-everything approach–a scattergun version of what Itami called the Hollywood Style.

Here the individual shots make a big deal out of a simple piece of business. We don’t need to see all of Tanaka’s office (since the rest of the space never gets used in the scene), and it doesn’t need to be so vast in the first place (except to announce that this is an expensive movie). The long-lens camera setup that lets Soames advance into the room and sit exists solely to let us watch the actor act, and it provides awkward cuts when bits of it are embedded in extreme long-shots.

It’s not hard to imagine alternatives. A straightforward tracking back from Soames as he enters and sits, framed from further away, would have kept both him and Tanaka in the frame. This framing could have easily shown Tanaka coming around to take up a position in the foreground by the desk, perhaps turned partly toward us so that we could peg him as a major character. Then if you insist on a cutaway to the ringing telephone, it would have had more impact, interrupting a sustained shot and contrasting to the fuller frame showing the two men.

Today many directors believe that we must always see the face of the person who’s speaking. So we get lots of shots, mostly singles, one per line, and each face is usually in close-up or medium-shot. Hence the great number of cuts per scene; here, counting from the swinging door, we get 23 shots in 97 seconds. And hence the repetitive reverse shots that cover the conversation.

I’m not the only one who notices these things. “If I see another over-the-shoulder shot,” says Steven Soderbergh, “I’m going to blow my brains out.”

Television probably has a lot to do with the emergence of this style, as some historians, me included, have argued. You have to be a good director to overcome the choppiness inherent in this manner of filming. I don’t think that Hafstrom did that. If the director had planned his shots in the finer-grained way Itami indicates, we might have had more visual variety, along with compositions and cutting that take us beyond the actors’ faces and line readings.

Dandelion soup

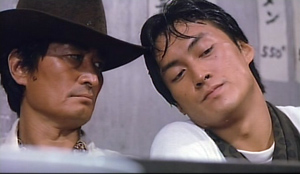

Now we might look at how Itami does it. An early scene of Tampopo (1985) also demands that a man, along with his sidekick, come into a room and sit down. We see Goro the trucker and his pal Gun enter the noodle shop, along with the little boy they’ve found lying on the street. We see them first from outside and then from inside the new locale, much as in our Shanghai example. But there’s no need for anything like that insert of the opening door.

Cut to a point-of-view shot that makes a point: Goro is entering a room full of thugs. Itami pans to show two knots of men in the shop, some of them threatening.

While each Shanghai shot does one thing at a time, this shot does two things at once. This shot sets up the hostilities that will ensue, while also laying out the space of the shop and positioning all Gun’s adversaries in it, along with the proprietress Tampopo.

Cut back to the men at the door, but it’s a different framing, from further back, than we saw initially. Now some of the thugs are staring at our heroes.

Itami is calibrating his compositions to give us new information. If this composition had been used for the first shot of the men entering, the subjective pan across the room wouldn’t have been so surprising. Now the camera cranes back to follow Goro and Gun striding to the middle of the shop and sitting down. They order bowls of noodles.

This orientation will be the dominant one in the course of the scene. But the space isn’t as bare as in the Shanghai scene; the men we see dotted around the room will play important roles in the action now and later. As in the Shanghai scene, there are cuts to close-ups, but they show more informative items than a ringing telephone. One shot picks out Tampopo herself (establishing her as a major character), another picks out Gun’s skeptical view of her cooking technique, and a third tilts down to show her hands cooking noodles in water not yet boiling.

To the noodle connoisseur Gun, this proves that she’s a maladroit cook, and another shot of the two men shows his reaction.

Cut to a long-shot. The long-shots of the office in Shanghai are always from a single position (the result of straight-through master-shot coverage), but here we get a slightly different framing than we’d seen earlier. The camera is somewhat lower, which allows Itami to stage a little piece of business. Tampopo’s son Tabo runs unseen out from behind the young thugs, along the aisle behind the stools, into the foreground, and out frame right. He has been beaten up outside, but Tampopo takes it in stride.

When Tabo has gone, the men resettle in for the next phase of the scene, when Tampopo serves Goro and Gun. The entire shot we’ve just seen is held for forty-one seconds. Soon a fight will erupt, delaying the revelation of how awful Tampopo’s noodles are.

This is not virtuoso direction, but it is smooth and precise. Each shot blends with the next with a degree of care we don’t get in the Shanghai instance. That’s partly because each shot is given its own small, completed arc of action. (The nine shots I’ve listed run ninety seconds.) For example, Tabo’s run down the aisle is prepared by a slight shift in Goro’s glance at the end of an earlier shot I’ve mentioned. He looks toward the door and tells Tabo he’ll catch cold.

This moment prepares us for the next bit of action, while also setting up the trucker’s gruff concern for the boy, an important element of the plot to come.

More generally, across the whole scene each long shot does more than simply orient us or cover changes in position; it’s enlivened by movement and incident. Nothing in the Shanghai scene approximates Itami’s willingness to let body language replace facial close-ups. Here Goro coolly samples the noodles while the gang prepares to rumble.

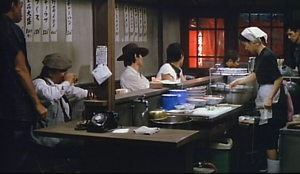

Later, an entire scene will be played in a packed long shot lasting nearly a minute. Goro has brought Tampopo to watch a master chef at work, and Itami is perfectly okay with concealing her face as she calls off all the orders that people have just made. We don’t need a close-up of her expression when she speaks; the important thing is her aptitude and the customers’ enthusiastic applause.

An unassertive shot like this, you want to say, respects the audience by letting us see everything that matters at each moment. We call it directing a movie.

Itami’s remarks in our epigraph come from Bob Strauss, “Director Juzo Itami,” Premiere (June 1988), p. 25. Soderbergh’s comment about OTS shots is taken from “Matt Damon: Steven Soderbergh really does plan to retire from filmmaking,” at the Los Angeles Times.

Shanghai has probably not come to a theatre near you. Delayed during the shooting, it sat on the shelf for some time before its premiere last summer in China. It’s announced for U. S. release in 2011 but the Weinstein company website says only that it’s “coming soon.” Planet Hong Kong redux will beat it, for sure.

As chance would have it, Tanaka in Shanghai and Gun in Tampopo are both played by Watanabe Ken.

My arguments about the emergence of this “intensified” version of classical continuity are made in The Way Hollywood Tells It, pp. 117-189. I’ve done a blog on the idea here; it’s hardly fair for me to compare Nora Ephron with Lubitsch, but she sort of asked for it. For more on economical staging and cutting, see our entry on Spielberg’s shooting style, as well as the idea of the Cross. For another comparison of Hollywood direction with an Asian alternative, see our entry on Jackie Chan’s Police Story.

A. D. Jameson makes strong points about inefficient shot breakdown in his essay “Seventeen Ways of Criticizing Inception.” Jameson invokes The Ghost Writer as a good counterexample, and indeed Polanski’s film often displays the sort of cut-to-cut restraint and control that Itami calls for. Jameson elaborates further in another epic post. There’s also an intriguing discussion at Jim Emerson’s Scanners blog of how much a filmmaker should rely on close-ups; the film at hand is Black Swan.

P.S. 5 January 2010: We’ve had an enthusiastic response to this entry; thank you, Twitterers. It occurred to me that readers might be interested in a similar comparison between Asian filmmaking and U.S. practice in a very early entry, back in 2006. Ironically, Soderbergh’s Good German was involved, the subject of an earlier post. The contrast case was Johnnie To’s PTU.

Shanghai (2010).

Three minutes of “Three Brothers”

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1

Kristin here:

Last wee I went to see Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1. Behind the pack, of course, since it had been out nearly a month. But I dislike watching films in a crowd. My ideal is to be alone in the theater, which David and I managed last week with Megamind. In this case I picked the first matinee on a school day and saw the film at our local Sundance multiplex. (Yes, even Sundance runs some popular films to help support the less successful art films.) I figured that noisy youngsters, even if they skipped school to see DH1, wouldn’t go to Sundance. I was right. Four or five adults were sitting about ten rows behind me. I never heard a peep or crackling candy wrapper out of them. The film was really film, too, 35mm.

I had been curious about how the filmmakers would deal with some of the stranger aspects of J. K. Rowling’s seventh and final book. Breaking it into two parts seemed an obvious and smart move, and it does have less of a rushed feeling than the previous adaptations had. But Deathly Hallows the book has some very unconventional aspects.

For a start, Rowling reveals dark, indeed downright nasty things alleged about Albus Dumbledore, who up to this point has been your standard-issue comic-but-wise, twinkly-eyed mentor figure. I wondered if the film would dare to do the same. It does, but so far only as a very minor side issue. In the first part, at least, Harry is obviously distinctly miffed that Dumbledore hasn’t left him more information about how to deal with horcruxes, but he doesn’t seem to feel that his hero had feet of clay.

Second, it seems downright perverse on Rowling’s part that in a long series which has come to focus on the search for horcruxes and should just be working up its climax, she throws another set of mysterious, lost objects, the three Deathly Hallows, at us. Let’s see, six horcruxes, three hallows. What’s the difference? Which should the characters be seeking, and why? Is Voldemort after them, too? In the book, Harry becomes obsessed with finding the hallows, even though the horcruxes are the main point. That last premise, Harry’s obsession, hasn’t shown up in the film, so far anyway, but otherwise the hallows are fully treated in the film.

Finally, Rowling gives us a very long portion of the book where Harry, Hermione, and, for a time, Ron, are fugitives moving from place to place, camping out each night as they try to figure out where the remaining horcruxes are—and not having much luck either with that or with destroying the one they have obtained. I personally think this is a rather daring move. Given that for this long section we are confined entirely to Harry’s point of view, we get little sense of what is happening in the outer world. Naturally the film can’t spend quite as much of its length on this period of nomadic existence. Still, it does devote an unexpectedly long time to portraying it.

Some critics have complained that the action stalls during this portion. Others have noted that the slow-down allows for us at last to linger over the psychological states of the three main characters, who are being worn down by fear, frustration, and the horcrux’s presence. This stretch also displays some beautifully bleak locations, well filmed. Plus, as Rowling no doubt intended, this part of the narrative conveys a real sense of the characters’ seemingly hopeless position: They are in great danger and without any apparent clue as to where to look next.

One minor obstacle that I remember noting when I first read the book is that the hallows are introduced by having Hermione read aloud a fairy tale from the book Dumbledore has bequeathed to her, The Tales of Beedle the Bard. The tale, “The Tale of the Three Brothers,” occupies only about two pages, but having someone read that much text aloud in a film can be deadly.

The filmmakers came up with a solution that is both inspired and extremely well executed. As Hermione reads, we see a roughly three-minute animated sequence that illustrates her words.  The filmmakers have acknowledged that their model was Lotte Reiniger’s technique of silhouette animation, which she developed in the 1920s and used for such classics as The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926). For DH1, similar silhouette effects are achieved with 3D digital animation.

The filmmakers have acknowledged that their model was Lotte Reiniger’s technique of silhouette animation, which she developed in the 1920s and used for such classics as The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926). For DH1, similar silhouette effects are achieved with 3D digital animation.

I wondered who had designed and animated this little sequence and determined to watch for references to it in the credits. As is typical with effects-heavy films these days, several companies were listed and the credits rolled by too quickly for me to catch much. Still, I don’t think that the little film-within-a-film was mentioned specifically or its creator named as having been attached to it. Even Variety‘s review, which refers in passing to the sequence, doesn’t mention its maker.

A lot of other viewers were impressed enough to try and find out who was responsible. DH1 was released in the US on November 19, and by the next day, Cartoon Brew posted a story on the subject: “A number of readers have written to ask who animated the shadow puppet-inspired ‘Tale of the Three Brothers’ sequence in the new Harry Potter film Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. It was directed and designed by Ben Hibon who produced it in association with Framestore.” Surprisingly, it also turns out that the section of Framestore that normally makes commercials did the “Three Brothers” scene.

I spent some time tracking Hibon down, finding some good-quality frames to display here, and locating clips. There are a few interviews with Hibon, plenty of clips and entire shorts, and filmographies. The video quality of some of these clips is dreadful, though, and a lot of the stories one finds via Google are short, repetitive pieces.

Most of this material is not all that easy to find, so herewith a guide to where you can most usefully find information on someone who seems to be an up-and-coming talent.

Hibon has designed video games, made music videos and commercials, done a short “screen” for MTV, and directed a few shorts and a trailer for a feature, A.D., which seems still to be in progress. The fullest filmography is the official one on the website for Hibon’s own company, Stateless Films.

Animation and effects expert Bill Desowitz has interviewed Hibon for Animation World Network. That’s recent, December 3, and deals exclusively with the DH1 scene. On November 23, fxguide posted an interview with Dale Newton, the sequence supervisor for the piece. An older, undated interview with Hibon on It’s Art Magazine concerns the series of five two-minute shorts collectively known as “Heavenly Sword.” These relate to a video game of the same name that Hibon designed. This series is visually quite distinctive, but it’s a far more conventional work than the “Three Brothers” short, being heavily influenced by anime.

Also on November 23, indiewire posted a short background article on Hibon, with several videos. With one exception, which I’ll get to shortly, don’t watch these films here or on YouTube. Why? Because the Stateless Films site has most of them and more. Hibon’s clips are larger and better quality than anything else I checked, plus they’re displayed with a black screen and far fewer distracting graphics than on YouTube. Click on the Archives link to see older works, including samples of Hibon’s work on videogames.

His site is the only place where I found a full version of his ad for the French bank, Crédit Agricole. The point of the ad is that this is the first green bank. It’s a gorgeous piece, full of images of pollution and decay gradually giving way to scenes of places restored to their pristine state and new, clean technology in place. Here are some images, from a vertical descent downward through a series of jet-trails (at bottom), a shot in which a wall of identical canned goods suddenly flies away to reveal a street market with fresh produce on sale, and windmills replacing old factory chimneys that fly apart:

There’s a dream-like quality to the whole thing, with a lot of shots, many with rapid movement, juxtaposed with slow, stately music.

The indiewire clips linked above include two shortened, English-language versions of this ad, with Sean Connery appearing to make the message explicit. There are also some Crédit Agricole ads made by more conventional filmmakers. Watch one or two of those, and you’ll find the contrast dramatic.

None of these sites and others with Hibon clips or shorts has the “Three Brothers” sequence, not surprisingly. That is, YouTube has some horrendous, out-of-focus subtitled auditorium videos, made in perhaps a South American or Spanish theater. Avoid like the plague.

Framestore’s site has some information on Hibon’s sequence, and the only clip from it that I could find. It’s very small and too dark to render the subtleties of the visuals, but there it is. Framestore also animated the two house-elves, Dobby and Kreatur, and there’s some information on that part of the project as well.

The January, 2011 issue of Cinefex has a story on DH1 that will undoubtedly include a section on the “Three Brothers” animation, but I haven’t seen that yet.

One reason that there are so many short pieces on Hibon on the internet is that at almost exactly the same time, on November 22, Variety announced that the filmmaker had been signed to direct a long-dormant New Line project, Pan. It’s a variation on the Peter Pan story, with the roles of villain and hero being switched; here Captain Hook is a detective on the trail of a certain child-kidnapper. The studio acquired the project in 1996, and for a while it looked as though Guillermo del Toro would direct. This time the film might get made, since the Variety story reports that it’s being cast and should start shooting next fall.

Back to the vaults, and over the edge

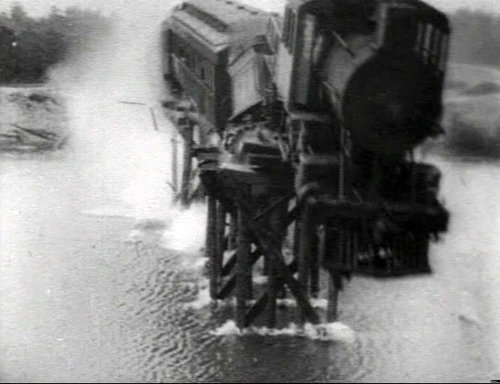

Unstoppable? Not really. The Juggernaut (1915).

DB here:

A few weeks ago, I praised Variety for making its back issues available digitally. The result is a magnificent vault of information. I also expressed frustration that the recent makeover of The Hollywood Reporter neglected to offer access to its original online archive, which indexed issues across the last twenty years. On the last point, some news.

First, my inquiry to the address listed on the HR website eventually yielded this blue note.

Good Morning,

We apologize for the delayed response.

I do not think there is a way to go back to prior to the changeover.

You would need to contact the publisher about that, as we do not handle the website directly.

Here is a phone number for you 323-525-2150.

Thank you.

I called the number, which handles only subscriptions, and the person answering had no idea what I was asking about.

But all is not lost. My first efforts to access the archive turned up very little for 2010, but shortly afterward I was able to access items from most of this year. Now, if you type a search term into the Search box of the HR site, it brings up items from as far back as 2008. This is an improvement over earlier attempts I made. It seems that THR is gradually adding old material to their archive, in reverse order.

Unfortunately, the search mechanism is quite indiscriminate. Searching “Johnnie To,” with and without quotation marks, yielded 290 hits, but I could find no articles about Johnnie To. Instead, the items with highest relevancy concerned Johnny Depp, Johnny English, John McCain, and the new Narnia movie.

The best news of all came from alert reader David Fristrom of Boston University. He advises me that the old HR archives are still available through LexisNexis. So I tried there with Johnnie To, and I got 338 references, stretching back to 1992. The ones at the top of the relevancy scale were indeed about Mr. To, including a Cannes piece called “Fest’s Red Carpet Flows with Blood.”

Accessing the archive isn’t straightforward, but you don’t need a subscription to HR if your library has purchased access to LexisNexis. I append David’s instructions at the end of this entry. Thanks to him for sorting this out for me.

Now, back into the Variety vaults.

This one’s a real train wreck

On 12 March 1915, Variety reviewed The Birth of a Nation. Alongside that review sits one of The Juggernaut, a Vitagraph feature directed by Ralph Ince. The reviewer, “Simc.,” dwells almost entirely on what he calls “the train-through-the-bridge thing.” The producers bought an old locomotive and some passenger cars, built a flimsy bridge, and ran their train off into what appeared to be a river.

The review exhibits some Variety touches that are still with us. Take the (quite reasonable) idea that nearly every movie is too long. “If this five-reeler were cut down to three reels, which could easily be done, the Vitagraph would have a real thriller.” There’s also the notion that people who come to the see the movie should be aware of its main attraction. “If the audience knows a train will go through a bridge at the finish, it won’t mind the fiddling about in the first four reels before that scene is reached. But if the audience doesn’t know what is to come, there may be many walk-outs.” At the beginning of Unstoppable we’ll sit through all the union and non-union wrangling and alpha-male preening if we’re sure we’re going to see a train that is certifiably unstoppable, except that it’s likely to be stopped by our heroes.

The Juggernaut does give us a pretty spectacular train wreck, as you see above. The entire film may not survive, but we have a version of the last reel (perhaps because a collector thought it worth saving). Train or no train, the film is of interest in showing what Griffith’s rivals were up to.

The plot centers on a crooked railroad magnate, Philip Hardin, and his college friend John Ballard. In the reel we have, Hardin’s daughter Louise, who loves John, sets out on an errand. When her car stalls she boards an express train. A track-walker finds worn ties on a bridge and warns the company, but too late. As Hardin races to stop Louise’s train, it arrives at the bridge and he watches it topple into the water. The sight kills him on the spot. John arrives and swims out to rescue Louise.

That’s when things get dicey. According to the Variety review and other sources, Louise dies in the wreck. Simc again:

The leading woman of the film, Anita Stewart, is discovered dead, lying against one of the windows, with particular pains taken that her features shall be clearly visible. . . . Anita is carried to shore and lain alongside of her father, who had died of heart failure (on land) a few moments before.

In the version available on DVD, John does bring her body ashore, but she revives, lifts herself up, and embraces him. The print ends there. Why the varying ending? Perhaps this is a version made at the time for a different market or in response to censorship, or it might be a rerelease using alternative footage. Or perhaps the press reviews were based on a synopsis supplied by Vitagraph, and the studio made modifications in the print before release.

The Juggernaut is also intriguing stylistically. By this point, crosscutting and scene analysis were common techniques in U. S. films. To set up the perilous situation, the cutting alternates shots of the track-walker, of Hardin, and of Louise. Once Hardin discovers that Louise is on the train headed for the dilapidated trestle, we are set up for a last-minute rescue–which fails. A particularly interesting series of shots shows Hardin’s trajectory converging with the train’s path. Riding in a power boat, Hardin looks back and we get a shot of the train in the distance, suggesting that he can see it.

From this we cut to a shot of Louise, confirming that she’s on board and showing her innocent lack of awareness. Then we get a repeated framing of the train rushing toward the bridge.

After another long shot of the train, we get a shot of Hardin in his powerboat with the train whizzing by in the background. This confirms that he was indeed watching it approach off screen left in the earlier shot, and it shows that he isn’t likely to catch up.

Once the train has toppled into the stream, there are some striking shots of people trapped inside or scrambling to escape. We see Louise raise one hand and then freeze, as if dying.

Earlier, there’s some emphatic “classical” cutting when Hardin learns that Louise is in danger. An enlarged framing (via an axial cut) underscores his reaction to the telegram.

Most striking is a series of shots of the dead-or-not Louise; the abrupt enlargement of her face has something of the force that Kurosawa would channel in his axial cuts.

Soon Ralph Ince cuts back along the same camera axis, and inward again as the couple embrace.

I can’t recall a comparable stretch of “concertina” cutting in the intimate scenes of Birth, and no such tight views of faces either. Griffith sometimes gives us “close-ups within medium-shots” by means of irising and vignetting.

Other directors (e.g., Dreyer) liked to use the serrated surround to highlight faces, but the American norm eventually became the unadorned closer view, as in the shot of Louise in The Juggernaut. Such shots probably saved production time as well. We’re confronted with the familiar situation that sometimes non-Griffith films from 1915 (e.g., The Cheat, Regeneration) look somewhat more “modern” than does Birth.

Going back to the train-through-the-bridge thing, the staging of the scene in late September 1914 elicited a lot of publicity. For one thing, the cost was played up; I’ve seen stories claiming $20,000, $30,000, and $50,000. The New York Times wrote up the shoot twice; the second of these could well be a publicity release from Vitagraph. According to the Times, the “river” was actually a flooded quarry. Before the shoot, buzz leaked out and crowds reported as numbering thousands showed up to watch. The crew spent hours herding them out of camera range. Actors were freezing in the water by the time cameramen got to take their shots. The Times also claims that the crash was filmed by fifteen (or twenty-five) cameras, a stupendously implausible number, especially in light of the footage we have. Worse, according to the second NYT story, Ince decided that the first pass didn’t work and they would have to start all over with a new train! A retake is not mentioned in Variety’s coverage, which does report some studio rivalry:

The ink on the New York dailies telling of the Vita’s big wreck stunt in the cameraing of “The Juggernaut” had hardly dried when the Universal sent over camera men posthaste Sunday to take views of what was left of the wreck. [Vitagraph studio manager Victor Smith], getting a hunch, got on the ground ahead of them and with a sturdy band of Vita “protectors” nipped the U’s little scheme in the bud.

One can only imagine how the “protectors” dealt with the Universal boys. Once more, the Variety Vault gives us the flavor, and perhaps sometimes the facts, of heroic times.

How to access the Hollywood Reporter archive, courtesy David Fristrom:

Once you are in LexisNexis, it can be a little tricky to search in The Hollywood Reporter (for some reason it doesn’t show up if you type “Hollywood Reporter” into the “Source Title” box), but you can follow these steps:

1. Click on “Power Search” in the upper-left corner.

2. On the “Power Search” page, find the “Select Source” box (near the bottom) and click on the “Find Sources” link.

3. On the “Find Sources” page, type “Hollywood Reporter” into the “Keyword” box and press enter.

4. At the top of the results should be “The Hollywood Reporter.”

Check the box next to it, then click on the “Ok-Continue” button that appears in the upper right corner.

5. You are now ready to search in the Hollywood Reporter archives –just type your search terms into the search box.

Thanks again to David!

The Variety review of The Juggernaut appears in the issue of 12 March 1915, p. 23. The story about Universal staff trying to shoot the wreckage is “Vita Putting It Over,” Variety, 10 October 1914, p. 23. The New York Times articles are “Film Train Wreck Almost a Tragedy,” NYT, 28 September 1914, p. 13, and “Tossing Dollars Around As If They Were Pennies,” NYT, 18 October 1914, p. X7. For more on Vitagraph, see Anthony Slide, The Big V: A History of the Vitagraph Company, rev. ed. (Metuchen: Scarecrow, 1987); Tony provides some production background on The Juggernaut on pp. 64-65.

The Juggernaut excerpt is available on Nickelodia 2, a DVD collection from Unknown Video. Oddly, the snapcase doesn’t list the reel as included on the disc, nor does the product information on the Unknown Video site or Amazon. I’d welcome more information about The Juggernaut‘s plot resolution if anybody out there has any.

The Juggernaut (1915).