Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

Revisiting Planet Hong Kong

The East Is Red (1993).

DB here:

In about two weeks, we try something new here. It’s an experiment in self-publishing, like everything on this site, but this time we offer a new version of an oldish book.

Planet Hong Kong was published in 2000. It sold pretty well for an academic book, shifting about 7000 copies through 2007. It was translated into Chinese twice, once in Hong Kong and once on the mainland. It also got encouraging reviews; I’ve put up links at the end of this entry.

At some point in 2008, Harvard University Press took the book out of print, a decision I learned about accidentally in spring of 2009. The story is here.

Since then, the book has become rather scarce; only about twenty copies are currently offered on Amazon. Rather than letting the poor thing fade away, I considered revising it for the web. The more I thought about it, the better the prospect looked. I could add as much to the text as I wanted. The text could be corrected, updated, and supplemented in the future. I could add photos, lots of them, and they could be in color. The text would be searchable. And instead of waiting nine to thirteen months to see the result, I could see it in weeks.

Moreover, readers could use the book as they liked. If it was presented as a pdf download, they could read it on a computer or on several models of e-book readers. They could also print out all or part of it. Interestingly, when I asked students and faculty if they’d use the book, nearly all said they’d print it, or let a facility like Kinko’s do it. All in all, it looked like an experiment worth trying.

[Insert montage of fluttering calendar pages here]

God of Gamblers (1989).

Since July I’ve spent virtually all my time on the book, with a break to go to the unmissable Vancouver film fest. Reworking the manuscript, watching and rewatching films, and preparing new material kept me from writing other things I had planned. No blog for Godard’s eightieth birthday, aiming to defend Film Socialisme as an intelligible part of his career. No web entry on the remarkable films of Kon Satoshi, creator of Perfect Blue, Millennium Actress, and The Girl Who Leaped through Time. No discussion of the 1950s-1960s art-cinema canon in the light of Tino Balio’s fine new book on that period in U. S. film culture. No speculations on the psychological processes aroused by a movie’s opening scenes. Maybe next year.

Instead, apart from two quick entries provoked by Inception, I was absorbed in Hong Kong movies on film and DVD, notes from ten years of film festivals and conferences, and plenty of books and websites. Two blog entries, one on coincidence and the other on Jackie Chan’s Police Story, were chips from the workbench. As for my seeing recent releases, The Social Network and Megamind have been about it.

Now, after a month of fourteen-hour days, Planet Hong Kong redux is close to ready. I hope to make it available on this site during the week of 20 December.

The beast has grown in captivity. The first edition ran about 130,000 words; the new version adds 40,000 words. (In defense, I remind you of Adorno explaining why The Authoritarian Personality turned out so long: “We didn’t have enough time to make it short.”) There are over 150 new stills, all in color and many from 35mm prints. But no clips! These films are too beautiful to be reduced to those wretched mutants you get on YouTube. Besides, I don’t have the rights.

Planet Hong Kong 2.0 will not be free. My Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema and Kristin’s Exporting Entertainment are free online, but neither of those was revised, and we absorbed comparatively little of the costs of production. By contrast, the digital PHK is the fruit of a lot of paid labor. Heather Heckman and Mark Minett did excellent scanning and Photoshop tweaking, and Meg Hamel, our web tsarina, designed the book and is making it web-ready. I’m still reckoning the cost of the e-book, but it will be $20 or less. Payment will be rendered unto Caesar, aka Caesar Bordwell, via PayPal.

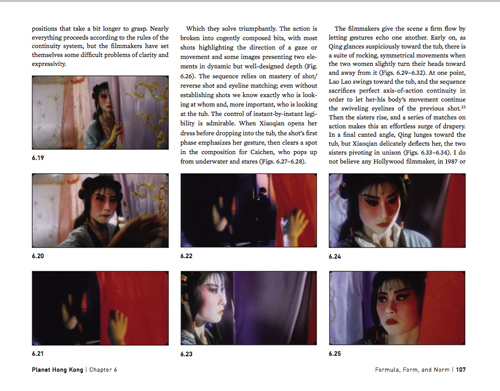

Here’s a sample page from our beta version. I’m still fiddling with the text, but the design looks to me like a nice compromise between the stability of a book page and the flow of a website. The file I’m using here is low-resolution, and this frame from it is a paltry 72 dpi jpeg, but the final pdf page should look very sharp. For curious boffins, the 35mm frame stills were scanned at 2000 dpi and reduced to 300 dpi for insertion. We don’t know yet how big the whole book’s file will be, but of course Meg will optimize it for downloading.

By the way: No, Wong Kar-wai did not invent the luscious image of the yearning woman.

Once the book is up, I plan to add a Hong Kong picture gallery to this site. It will include snapshots of celebs and fans from across the years 1995-2010.

ISNAQs (Infrequently, Sometimes Never, Asked Questions)

Enter the Dragon (1973).

PHK isn’t a comprehensive history of Hong Kong filmmaking; for that you must turn to Stephen Teo’s Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimensions. Nor is it a fan’s guide to the wild and crazy side of this local cinema. Stefan Hammond’s two books handle that task nicely, and there are many similar handbooks since. Most strikingly, the fanboys have been usurped by the professors. A geyser of academic books and articles about Hong Kong cinema burst in the new millennium, along with invaluable documentation from the Hong Kong Film Archive and the Hong Kong International Film Festival. My book doesn’t rival these.

What does this book do, then?

I try to design my books in layers, with different implications and possibly different readerships, at each level. The first and founding layer of Planet Hong Kong is my effort to convey the sheer pleasure offered by this filmmaking tradition. I write as an enthusiast for other enthusiasts, and for potential converts. In this respect, PHK is an academic dressup of a noble gonzo tradition. Hong Kong cinema has benefited from the gusto of admirers like Ross Chen, Lisa Morton, Stephen Cremin, Grady Hendrix, Stefan Hammond, Chuck Stephens, Richard Corliss, David Chute, Howard Hampton, and other lively writers. This cinema inspires dazzling, sometimes headbanging appreciations from critics.

Next there’s a historical layer. Hong Kong cinema is, I’m convinced, an important “national school” in world film history. It shaped global popular culture to a degree matched only by the westerns and gangster films turned out by the Hollywood studios. Every video game that includes martial arts, every American action movie, and every comic book showing a sword-wielding superhero owe a lot to Bruce Lee and the cinema he springs from. Less obviously, Hong Kong innovated approaches to film form and style that remain striking today. When I wrote the book, this artistic heritage was almost completely unappreciated, by both general audiences and specialized film scholars. The situation is a little better now, but the case always needs restating. Through close analyses of many films and sequences, the book tries to show the originality and force of the Hong Kong touch.

Another layer up, the book asks how popular cinema works. The clichéd split between “art” and “business” isn’t much help in understanding mass-entertainment film. The business relies on artistic traditions, and those traditions in turn are born from and shaped by industrial factors–not just constraints but also enabling opportunities. Hong Kong film provides a case study in how a mass-entertainment movie builds its effects on genre, star appeal, storytelling strategies, and stylistic tactics. It shows vividly how a media industry relies on conventions, and how artists tap those, stretch them, and sometimes twist them out of recognition. My interviews with several writers, directors, choreographers, and actors helped me understand the ways that creativity could be fostered by craft traditions.

At the most general level, PHK is a small-scale demo of an approach to asking questions about cinema. It shows how we might systematically study the principles of construction informing popular filmmmaking. Stealth poetics, in other words.

The old and the new

Leave Me Alone (2004).

The big changes in Asian cinema of the last decade make the original book something of a historical artifact itself. I did the research across the 1990s and wrote nearly all of it in 1998. Its emphases reflect issues circulating in fan and academic culture at that time. DVDs, introduced in 1997, had not become widespread, and VCDs were unwatchable. (Still are.) Most of the films that mattered had to be studied on film copies, although laserdiscs offered a passable backup in some cases. VHS tapes were seldom letterboxed, but laserdiscs often were.

The biggest constraint on the book was the scant availability of Shaw Brothers films on any format. Thanks to the Hong Kong International Film Festival, trips to archives, and the film collector’s market, I was able to see quite a few, but nothing like what’s available now in the massive and restored Shaw DVD library. Consequently, apart from the work of King Hu, Chang Cheh, and Lau Kar-leong, PHK doesn’t deal with the very interesting output of the territory’s most famous company. Fortunately, Shaws has been carefully studied in the years since my book, in a massive volume from the Hong Kong Film Archive and in Poshek Fu’s China Forever: The Shaw Brothers and Diasporic Cinema. For my part, this web essay and these blog entries try to make amends.

I could have recast PHK top to bottom, but I wasn’t convinced that I could come up something as pointed as the original. The text has been corrected, of course, and patches have been recast for greater clarity. It has also been enhanced by a few more examples, film sequences I referred to in passing but could not illustrate because I couldn’t find a print or couldn’t include color images. The chief updating is a series of sections added to the back end.

So here is what the book now looks like.

The first chapter broaches the general idea of an aesthetic of popular cinema. There follows an interlude comparing Hong Kong and Hollywood, focusing on The Untouchables and Gun Men. Instead of launching into a general history of local cinema, Chapter 2 sketches some general features of the territory’s film culture, concentrating on its audiences and its critics. The following interlude,”Two Dragons,” talks about Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan, the two most famous Hong Kong heroes. Chapter 3 provides a condensed history of Hong Kong filmmaking up to 1997. The next chapter, “Once Upon a Time in the West,” traces how Hong Kong film attracted fans and festival prestige. There’s an interlude devoted to John Woo, then the fanboys’ demigod.

The first chapter broaches the general idea of an aesthetic of popular cinema. There follows an interlude comparing Hong Kong and Hollywood, focusing on The Untouchables and Gun Men. Instead of launching into a general history of local cinema, Chapter 2 sketches some general features of the territory’s film culture, concentrating on its audiences and its critics. The following interlude,”Two Dragons,” talks about Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan, the two most famous Hong Kong heroes. Chapter 3 provides a condensed history of Hong Kong filmmaking up to 1997. The next chapter, “Once Upon a Time in the West,” traces how Hong Kong film attracted fans and festival prestige. There’s an interlude devoted to John Woo, then the fanboys’ demigod.

Chapter 5 surveys the industry, with emphasis on filmmakers’ craft traditions (how stories are planned, scenes are cut, and so on). The interlude that follows takes Tsui Hark as an instance of a director who creatively reworked such traditions. Chapters 6 and 7 go into the most detail about the aesthetics of Hong Kong film, surveying the dynamics of genre, the star system, visual style, and plot construction. Between these two chapters is sandwiched an interlude devoted to Wong Jing, the most disreputable major filmmaker in the territory. The longest chapter, the eighth, explores the distinctive aesthetic of action pictures, from martial arts to contemporary crime movies. The interlude that follows discusses three outstanding directors in the martial-arts tradition: Chang Cheh, Lau Kar-leung, and King Hu. The final chapter of the original book considers how the premises of popular cinema can be adapted to create “art films.” The principal, but not sole, example is the work of Wong Kar-wai. The original book concluded with an analysis of Chungking Express.

The new material in this edition starts with a chapter on changes in the film industry since 1997. That’s followed by an interlude focusing on the Infernal Affairs trilogy, which was as you know the source for The Departed. The next chapter considers how the artistic trends surveyed in the first edition have changed over the last ten years or so. While discussing developments in genre, storytelling, technology, and style, the chapter includes sections on Stephen Chow (particularly Shaolin Soccer and Kung-Fu Hustle), Wong Kar-wai (In the Mood for Love and 2046), and Johnnie To Kei-fung. The final interlude is a more in-depth discussion of To’s crime films and their relation to the indigenous action-movie tradition. At the very end is a new bibliography and endnote citations.

Readers not drawn to Hong Kong cinema might find my more general arguments of interest. For example, I suggest that Hong Kong shows us how important regional and diasporan networks are in creating and maintaining a film culture. To the claim that films reflect their societies, I reply that Hong Kong films suggest a different way to think about such a dynamic, using the model of cultural conversation. Readers interested in fandom should find something intriguing in the story of how cultists around the world helped establish Hong Kong film as a cool thing in the early 1990s. I also argue against the tendency in film studies to assume that when a film tradition doesn’t follow the rules of classical plot construction it must be based on something called “spectacle.” I suggest instead that we need to study principles of episodic plotting, which are probably quite common in popular art generally. In these and other areas, I wanted to use this cinema as a way into thinking about popular moviemaking as a whole.

After World War II, a tailor shop in Hong Kong put up a sign: “Reopening soon. Sooner if possible.” The same goes for me: Planet Hong Kong Redux is coming soon. Sooner if possible.

Here are some reviews of Planet Hong Kong by Richard Corliss in Time Asia (said I typed in my shorts with a beer at my elbow), Paul F. Duke in Variety (liked the book, worried that I talked like a Marxist), an anonymous writer in The Economist (said I’m a scholar who writes as a fan), Steve Erickson in Senses of Cinema (noticed my appreciation of stars), Mina Shin for Framework (developed my suggestions about festival culture), Leon Hunt in Scope (liked book, called me an empiricist, which tickles me down to my sense data), and Shelly Kraicer at chinesecinemas.org (as usual, more generous than he should be).

The most unexpected mention of the book seems to have vanished from the web. A New York critic who is surprisingly easy to outrage made an interesting attempt to charge me with synergistic marketing. He proposed, in the midst of a pan of Tsui Hark’s Time and Tide, that PHK was a covert attempt to promote Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, which had just won acclaim at Cannes. I wrote James Schamus, writer-producer of CTHD: “Now that we’ve been found out, we have to abandon our scheme to reprint my Dreyer book so as to coincide with Ang’s remake of Ordet.”

My quotation from Adorno may be apocryphal.

P.S. 13 December: Thanks to Daniel Erdman, I’ve now got the synergistic review mentioned above. It’s here. Thanks as well to Antti Alanen, who writes from Finland:

About ‘no time to be short’: quite possibly Adorno said so, and you are in good company:

Blaise Pascal: “Je n’ai fait celle-ci plus longue que parce que n’ai pas eu le loisir de la faire plus courte” (The Provincial Letters). J.W. von Goethe: »Da ich keine Zeit habe, dir einen kurzen Brief zu schreiben, schreibe ich dir einen langen« (letter to his sister Cornelia, but Goethe had apparently learned this from Cato and Cicero).

And soon after that came from Antti, Philippe Theophanidis wrote to point out the Pascal source as well. Once more I pay for the lack of a classical education!

Golden Scissors Part I (1963). Famous martial-arts choreographer and director Lau Kar-leung is on the far right. Source: Hong Kong Film Archive.

The buddy system

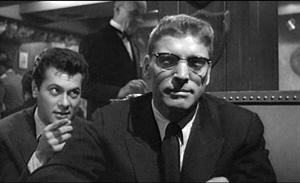

Sweet Smell of Success.

DB here:

Many of our friends write books, and what are friends for if not occasionally to promote each other’s books? Here’s an armload of titles, most of them recently published. They’re so good that even if the authors weren’t our friends and colleagues, I’d still recommend them.

James Naremore has made major contributions to film studies since his fine monograph on Psycho, published way back in 1973. That book remains one of the most sensitive analyses of this much-discussed movie. Now he has another monograph, on the stealth classic Sweet Smell of Success. When I was coming up, Alexander Mackendrick wasn’t much appreciated, and this movie slipped under the radar. More recently it has emerged as one of the model films of the 1950s, and not just for James Wong Howe’s spectacular location cinematography. It’s a very brutal story, with Tony Curtis playing against type as venal press agent Sidney Falco and Burt Lancaster as J. J. Hunsecker, a monstrously vindictive newspaper columnist.

Jim’s book provides a scene-by-scene commentary but also more general analysis of production circumstances and directorial technique. An enlightening instance is what Mackendrick called “the ricochet”—when character A talks to character B but is aiming at character C. This allows the filmmaker great flexibility in framing and cutting, often showing C’s reactions while we hear the dialogue offscreen. In the shots surmounting this blog, Sidney is needling J. J. by asking the Senator if he approves of capital punishment. Jim’s book joins his work on Welles, Kubrick, and film noir as part of a subtle reassessment of American postwar cinema.

With the current revival of interest in André Bazin’s film theory, it’s fruitful to look again at the “classical” theoretical tradition in which he participated. “Classical” here refers to the very long period before the emergence of semiotic and psychoanalytic theories of cinema in the 1960s. The newer theories have somewhat beclouded our recognition of how imaginative and wide-ranging the old folks were. In Doubting Vision: Film and the Revelationist Tradition, Malcolm Turvey scrutinizes four thinkers who saw film as having the power to show us things beyond (or above, or below) surface reality. In the spirit of analytic philosophy, Turvey carefully lays out the positions of Béla Balázs, Jean Epstein, Siegfried Kracauer, and Dziga Vertov before asking whether their claims hold up.

With the current revival of interest in André Bazin’s film theory, it’s fruitful to look again at the “classical” theoretical tradition in which he participated. “Classical” here refers to the very long period before the emergence of semiotic and psychoanalytic theories of cinema in the 1960s. The newer theories have somewhat beclouded our recognition of how imaginative and wide-ranging the old folks were. In Doubting Vision: Film and the Revelationist Tradition, Malcolm Turvey scrutinizes four thinkers who saw film as having the power to show us things beyond (or above, or below) surface reality. In the spirit of analytic philosophy, Turvey carefully lays out the positions of Béla Balázs, Jean Epstein, Siegfried Kracauer, and Dziga Vertov before asking whether their claims hold up.

I’m not giving much away by revealing that Malcolm thinks the revelationist tendency has its problems. But his purpose isn’t simply to reject the position. He treats it as an instance of what he calls “visual skepticism,” the idea that we ought to treat our ordinary intake of the world as something suspect. This idea, Malcolm argues, is central to modernism in the visual arts. He extends his critique of visual skepticism to more recent theorists as well, notably Gilles Deleuze, and he shows how his own ideas apply to films by Hitchcock, Brakhage, and other directors. Malcolm’s book is a model of theoretical clarity and probity, and a stimulating read as well.

Skepticism of another sort is central to Carl Plantinga’s Rhetoric and Representation in Nonfiction Film. One result of semiotic theory was to question whether a film could ever adequately represent reality. If a movie is only an assembly, however complex, of conventional signs, it can’t give us access to something out there. Even a documentary, some theorists argued, had no privileged access to the real world, let alone to general truths. “Every film is a fiction film” was a refrain often heard at the time. Carl tackles this assumption head-on by carefully arguing that just because a documentary is selective, or biased, or rhetorical, that doesn’t mean that it can’t affirm true propositions about our social lives.

Like Malcolm, Carl brings a philosopher’s training in conceptual analysis to debates about the ultimate objectivity of any documentary. In adopting a position of “critical realism” opposed to skepticism, Carl examines the realistic status of images and sounds, the way documentaries are structured, and filmmakers’ use of technique. He shows, convincingly to my mind, that a documentary may offer an opinion and still be objective and reliable to a significant degree. Carl’s 1997 book went out of print before it could be published in paperback. He has enterprisingly reissued it as a print-on-demand volume, and it’s available here.

To take film theory in another direction, there’s Evolution, Literature, and Film, edited by Brian Boyd, Joseph Carroll, and Jonathan Gottschall. As a wider audience has become aware of the power of neo-Darwinian thinking, more and more scholars have been arguing that evolutionary theory can shed light on aesthetics. The most visible effort recently is Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct.

To take film theory in another direction, there’s Evolution, Literature, and Film, edited by Brian Boyd, Joseph Carroll, and Jonathan Gottschall. As a wider audience has become aware of the power of neo-Darwinian thinking, more and more scholars have been arguing that evolutionary theory can shed light on aesthetics. The most visible effort recently is Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct.

For some years Brian, Joe, and Jonathan have been in the forefront of this trend, with many books and articles to their credit. Their anthology pulls together broad essays on biology, evolutionary psychology, and cultural evolution before turning to art as a whole and then focusing on literature and cinema. There are also pieces displaying evolutionary interpretations of particular works, and a finale that provides examples of quantitative studies of genre, gender variation, and sexuality, including an article called “Slash Fiction and Human Mating Psychology.”

Among the film contributors are other friends like Joe Anderson, a pioneer in this domain with his 1996 book The Reality of Illusion, and Murray Smith, who provides an acute piece called “Darwin and the Directors: Film, Emotion, and the Face in the Age of Evolution.” There are also essays of mine, drawn from Poetics of Cinema. In all, this book presents a persuasive case for an empirical, broadly naturalistic approach to the arts.

By the way, the same team is involved with an annual, The Evolutionary Review, edited by Alice Andrews and Joe Carroll. Its first issue offers articles on Facebook, musical chills, women as erotic objects in film, and Art Spigelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers (by Brian Boyd).

Some books emerge from conferences, and Tom Paulus and Rob King’s Slapstick Comedy is a good instance. Based on “(Another) Slapstick Symposium,” held at the Royal Film Archive of Belgium in 2006, the anthology brings together a host of experts who look back at madcap comedy in American silent film. There are essays on particular creators—Griffith, Sennett, Fatty, and Chaplin, inevitably—as well as pieces on slapstick parodies of other movies and the genre’s relation to modernity, also inevitably. Tom Gunning offers a fine analysis of Lloyd’s Get Out and Get Under (1920), concentrating on a complex string of gags around an automobile. The collection gathers work by some of the outstanding scholars of silent film while also, of course, making you want to see these crazy movies again.

You also want to see all the movies lovingly evoked by Gary Giddins in Warning Shadows: Home Alone with Classic Cinema. As indicated in another blog entry, I find Giddins one of the best appreciative critics we’ve ever had. Any essay, indeed almost any sentence, cries out to be quoted. Here he is on Edward G. Robinson:

You also want to see all the movies lovingly evoked by Gary Giddins in Warning Shadows: Home Alone with Classic Cinema. As indicated in another blog entry, I find Giddins one of the best appreciative critics we’ve ever had. Any essay, indeed almost any sentence, cries out to be quoted. Here he is on Edward G. Robinson:

His round, thick-lipped, putty face could brighten like paternal sunshine or shut down in implacable contempt or stall with crafty desperation or pontificate with ingenuous wisdom; his short, stumpy, erect frame could sport a tailor-made as smartly as Cary Grant.

Some of the pieces in Giddins’ latest collection were designed to accompany DVDs, but they will outlast this evaporation-prone genre. Other reviews come from the New York Sun, which gave him freedom to mix and match his subjects: Young Mr. Lincoln and Lust for Life (both biopics), Lady and the Tramp and Miyazaki movies. The collection opens with Giddins’ thoughts on how changes in film exhibition, from nickelodeons to digital screens, have altered our relationship with the movies. This isn’t just nostalgia, because his survey allows him to celebrate the power of DVD to exhume forgotten titles. The standards for a film classic, he notes, “are gentler and more flexible” than those in appraising other arts. “The passing decades are a boon to the appreciation of stylistic nuance that gives certain melodramas and genre pieces the heft of individuality.”

Who was Segundo de Chomón? In the 1970s, I kept finding that films I thought were by Méliès turned out to bear this mysterious signature. You imagine a man in a cape and a floppy hat. Photographs show someone a little less operatic, but with a superb mustache. Today he’s far from a mystery, although many of his movies can’t be fully identified. Several scholars have followed his trail, none more thoroughly than Joan M. Minguet Batllori in Segundo de Chomón: The Cinema of Fascination.

Chomón started as a cinema man-of-all-work in Barcelona, translating film titles, distributing copies, and producing films for Pathé. After moving to Paris in 1905, he continued working for the company and established his fame with trick films. He returned to Barcelona to create a production company, but that failed. On he went to Italy, where he specialized in visual effects, most famously for Cabiria (1914).

In his Parisian Pathé years, he was in charge of all the studio’s trick films, which included not only stop-motion, superimpositions, and other effects but also marionettes and animation. Joan argues that he was a prime exponent of the “cinema of attractions,” Tom Gunning’s term for that early mode of filmmaking which aims to startle and enchant the audience. A famous instance is Kiriki, acrobats japonais (1907), which shows gravity-defying stunts.

Chomón accomplished this by shooting from straight down, filming the performers on the floor. They had to simulate leaps and flips as they rolled along each other’s bodies, and then they had to slip perfectly into position. This English edition of Joan’s book on Chomón, full of information and providing a “provisional filmography” along with many pages of gorgeous color images, will be available soon here.

We recently noted the anniversary of our book on classic studio cinema, a 1985 project in which we bypassed talking about exhibition. That part of the industry has been a scholarly growth area in the years since, and one of the newest yields is Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History, by Sheldon Hall and Steve Neale. It’s a chronological account of Big Movies, from the earliest features to the digital era, and it concentrates on how such films have been marketed and shown. It explains how exhibition changed across the decades, and how we got the phenomenon of the “roadshow” movie, the film shown selectively (only certain cities), at intervals (perhaps only one matinee and one evening screening), and at more or less fixed prices. My middle-aged readers will remember roadshow releases like The Sound of Music (1965), although there were many before and even a few since.

We recently noted the anniversary of our book on classic studio cinema, a 1985 project in which we bypassed talking about exhibition. That part of the industry has been a scholarly growth area in the years since, and one of the newest yields is Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History, by Sheldon Hall and Steve Neale. It’s a chronological account of Big Movies, from the earliest features to the digital era, and it concentrates on how such films have been marketed and shown. It explains how exhibition changed across the decades, and how we got the phenomenon of the “roadshow” movie, the film shown selectively (only certain cities), at intervals (perhaps only one matinee and one evening screening), and at more or less fixed prices. My middle-aged readers will remember roadshow releases like The Sound of Music (1965), although there were many before and even a few since.

Sheldon and Steve trace in unprecedented detail the cycles of blockbusters that have run throughout American cinema. In the process they refreshingly redefine the very idea. We don’t usually think of The Best Years of Our Lives as a Big Movie, but it runs three hours and was considered a “special” production, comparable to the more obvious sprawl of Duel in the Sun. The authors bring the story up to date by considering today’s event movies as a “Cinema of Spectacular Situations.” Yes, that category includes comic-book films, Inception, and, of course, the 3D sagas that may finally be wearing out their welcome. (My editorializing, not theirs.)

Japanese cinema is endlessly fascinating in all its eras; I’d argue that in toto it’s one of the three greatest national cinemas in film history. The postwar period is exceptionally interesting because of the American occupation (1945-1951) and its effects on Japanese film culture. This period has already provoked one of the best books we have on Japanese cinema, Kyoko Hirano’s Mr. Smith Goes to Tokyo, and it finds a worthy accompaniment in Hiroshi Kitamura’s Screening Enlightenment: Hollywood and the Cultural Reconstruction of Defeated Japan. Kyoko focused on how US policy shaped domestic filmmaking, while Hiroshi asks how the Occupation helped American studios penetrate the local market.

Over six hundred Hollywood movies poured into Japan during the period, and Hiroshi traces how local tastemakers as well as U.S. policymakers drew audiences to them. Young Japanese learned about the Academy Awards, assembled in movie-study clubs to discuss what they were seeing, and were urged to consider even a gangster tale like Cry of the City (1950) as demonstrating the humanistic side of democracy. A center of this activity was Eiga no tomo (“Friends of the Movies”), a magazine that went beyond entertainment news and tried to reshape the tastes of young people. In sharp prose and vivid evidence, Hiroshi captures the ways in which American cinema promised to help heal a devastated country.

The Danish Directors, by Mette Hjort and Ib Bondebjerg, has become a standard companion to the most successful “small cinema” on the European scene. Now it has a successor in The Danish Directors 2: Dialogues on the New Danish Fictional Cinema, edited by Mette, Eva Jorholt, and Eva Novrup Redvall. Once again, we get lengthy, in-depth interviews covering the value of film education, the vagaries of funding, and filmmakers’ creative decision-making. Lone Scherfig, Christoffer Boe, Per Fly, Paprika Steen, and many other major figures are included. (Disclosure: The editors were kind enough to dedicate the book to me.)

The Danish Directors, by Mette Hjort and Ib Bondebjerg, has become a standard companion to the most successful “small cinema” on the European scene. Now it has a successor in The Danish Directors 2: Dialogues on the New Danish Fictional Cinema, edited by Mette, Eva Jorholt, and Eva Novrup Redvall. Once again, we get lengthy, in-depth interviews covering the value of film education, the vagaries of funding, and filmmakers’ creative decision-making. Lone Scherfig, Christoffer Boe, Per Fly, Paprika Steen, and many other major figures are included. (Disclosure: The editors were kind enough to dedicate the book to me.)

While the first volume is a rich storehouse of information on Danish film in “the Dogma era,” the newest volume shows how directors (some of whom made Dogma projects) have gone beyond it. In preparing 1:1, a film about Danes and Arab immigrants living in a housing project, Annette K. Olesen had a full script but concealed it from the non-professional cast. After getting the performers comfortable with ordinary situations, she began staging scenes while encouraging improvisation. Screenwriter Kim Fupz Aakeson incorporated the improvised material into revisions of the script.

By contrast, the prolific director-screenwriter Anders Thomas Jensen (Adam’s Apples, The Green Butchers), relies on strong structure, with lean expositions and sharply defined climaxes. He appreciates clean filming technique too.

It’s easy to make something that’s ugly and handheld, but you have to take telling stories with images seriously. You have to take the language of film seriously. Many Danish directors have started doing this in recent years and it’s wonderful, because there was a time when everything looked Dogma-like and I found myself thinking, “It’s got to stop now.”

To those who think that Danish cinema is at risk of becoming a cinema of cozy liberal reassurance, this collection offers many salutary signs. Every director speaks of the need to keep innovating, to push ahead provocatively. Simon Staho, whose Day and Night seems to me one of the most adventurous Danish films of recent years, aims at utter purity: “My task is to figure out how to add as little as possible to the black screen. The damned problem is that you have to add image and sound!”

What makes all these books exciting to me is a willingness to test ideas–sometimes very general ones–about cinema and the wider world by examining film as a distinctive art form. Even the most conceptual books on this week’s shelf are firmly rooted in the particular choices that creators make and the concrete ways that viewers respond.

Next stop: Vancouver International Film Festival. Whoopee!

Day and Night.

What makes Hollywood run?

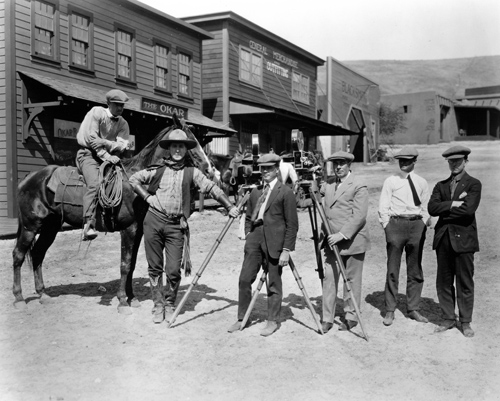

William S. Hart and crew at Inceville, 1910s.

DB here:

For decades most people had a sketchy idea of The Hollywood Studio Film. Boy meets girl, glamorous close-ups, spectacular dance numbers or battle scenes, happy endings, fade-out on the clinch. But even if such clichés were accurate, they didn’t cut very deep or capture a lot of other things about the movies. Could we go farther and, suspending judgments pro or con the Dream Factory, characterize U. S. studio filmmaking as an artistic tradition worth studying in depth? Could we explain how it came to be a distinctive tradition, and how that tradition was maintained?

In 1985 Routledge and Kegan Paul of London published The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960. Kristin, Janet Staiger, and I wrote it. Since it’s rare for an academic film book to remain in print for twenty-five years, we thought we’d take the occasion of its anniversary to think about it again. Those thoughts can be found in the adjacent web essay, where we three discuss what we tried to do in the book, spiced with comments about areas of disagreement and more recent thoughts. This blog entry is just a teaser.

A touch of classical

John Arnold, a Bell & Howell camera, and Renée Adorée in 1927.

The prospect of analyzing Hollywood as offering a distinctive approach to cinematic storytelling emerged slowly. The earliest generations of film historians tended to talk about the emergence of film techniques in a rather general way. For example, historians were likely to trace the development of editing as a general expressive resource, appearing in all sorts of movies. While they recognized that, say, the Soviet filmmakers made unusual uses of this technique, writers still tended to think of editing as either a fundamental film technique or a very specific one—e.g., Eisenstein’s personal approach to editing.

An alternative approach was to understand the history of film as an art as a stream of cinematic traditions, or modes of representation, within which filmmakers worked. From this angle, there was a Hollywood or “standard” or “mainstream” conception of editing, and this didn’t exhaust all the creative possibilities of the technique. But it went beyond the inclinations of any particular director. People had long recognized that there were group styles, like German Expressionism and Italian Neorealism, but it took longer to start to think of mainstream moviemaking as, in a sense, a very broad and fairly diverse group style.

In the late 1940s André Bazin and his contemporaries started to point out that different sorts of films had standardized their forms and styles quite considerably. Bazin attributed the success of Hollywood cinema to what he called “the genius of the system.” In my view, his phrase referred not to the studio system as a business enterprise but rather to an artistic tradition based on solid genres and a standardized approach to cinematic narration. This artistic system, he suggested, had influenced other cinemas, creating a sort of international film language.

The idea that there was a dominant filmmaking style, tied to American studio moviemaking, was developed in more depth during the 1960s and 1970s. Christian Metz’s Grande Syntagmatique of narrative film pointed toward alternative technical choices available in the “ordinary film.” Raymond Bellour’s analysis of The Birds, The Big Sleep, and other films pointed to a fundamental dynamic of repetition and difference governing American studio cinema. Somewhat in the manner of Roland Barthes’ S/z, Thierry Kuntzel’s essays explored M and The Most Dangerous Game looking for underlying representational processes that were characteristic of studio films. From a somewhat different angle, in the book Praxis du cinema and later essays Noël Burch traced out a dominant set of techniques that formed what he would eventually call the “Institutional Mode of Representation.” The Cahiers du cinéma critics famously posited different categories of filmic construction, each one tied to the representation of ideology. In English, Raymond Durgnat was an early advocate of studying what he called the “ancienne vague,” the conventional filmmaking that young directors were rebelling against.

The trend was given a new thrust by the British journal Screen, which disseminated the idea of a “classical narrative cinema,” a mode of representation characterized by distinctive dynamics of story, style, and ideology. Perhaps the most emblematic article of this sort was Stephen Heath’s in-depth analysis of Touch of Evil. Over the same years a new generation of film historians was studying early cinema with unprecedented care, and they too were finding a variety of modes of representation at work in filmmaking of the pre-1920 era.

The effect was to relativize our understanding of Hollywood. Mainstream U. S. commercial filmmaking wasn’t the cinema, merely one branch of film history, one way of making movies. Breaking a scene into a coherent set of shots, to take the earlier example, wasn’t Editing as such. It was one creative choice, although it had become the dominant one. And what made Hollywood’s brand of coherence the only option? Eisenstein, Resnais, Godard, and other filmmakers explored unorthodox alternatives.

Nearly all of the influential research programs of the period emphasized the film as a “text.” This wasn’t surprising, since several of the writers were working with concepts derived from literary semiotics and structuralism. At the same period, other scholars were developing ideas about Hollywood as a business enterprise. Douglas Gomery, Tino Balio, and a few others were showing that the studio system was just that—a system of industrial practices with its own strategies of organization and conduct. But most of those business studies did not touch on the way the movies looked and sounded, or the way they told their stories.

Could the two strains of research be integrated? Could one go more deeply into the films and extract some pervasive principles of construction? And could one go beyond the films and show how those principles of style and story connected to the film industry?

The prospect of integrating these various aspects—and, naturally, of finding out new things—intrigued us.

Secrets of the system

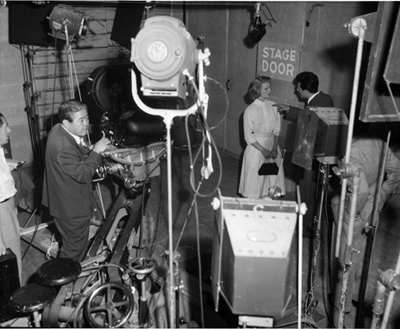

Main Street to Broadway (1953, MGM release). Cinematographer James Wong Howe on left.

The overall layout of CHC tried to answer these questions while weaving together a historical overview. Part One, written by me, provided a model or ideal type of a classical film, in its narrative and stylistic construction. Part Two, by Janet, outlined the development of the Hollywood mode of production until 1930. In Park Three, Kristin traced the origins and crystallization of the style, from 1909 to 1928. Part Four included chapters by all three authors on the role of technology in standardizing and altering classical procedures during the silent and early sound era. In Part Five Janet resumed her account of the mode of production, tracing changes from 1930 to 1960. The technology thread was brought up to date in Part Six, where I discussed deep-focus cinematography, Technicolor, and the emergence of widescreen cinema. Part seven, which Janet and I wrote together, pointed out implications of the study and suggested how Hollywood compared with alternative modes of film practice.

Clearly, CHC was several books in one. Janet could easily have written a free-standing account of the mode of production. Kristin could have done a book on silent film technique and technology. I could have focused on style and form, using sound-era technologies as test cases. The point of interspersing all these studies (and creating a slightly cumbersome string of authorial tags within sections) was to trace interdependences. For instance, Kristin examined the emerging stylistic standardization in the 1910s. Janet showed how that standardization was facilitated by a systematic division of labor and hierarchy of control, centered around the continuity script. At the same time, the organization of work was designed to permit novelties in the finished product, a process of differentiation that is important in any entertainment business.

Moreover, once the stylistic menu was standardized, it reinforced and sometimes reshaped the mode of production. At every turn we found these mutual pressures, a mostly stable cycle among tools, artistic techniques, and business practices. Once the studios became established, they needed to outsource the development of new lighting equipment, camera supports, microphones, make-up, and other tools. A supply sector grew up, carrying names like Eastman, Bell & Howell, Mole-Richardson, Western Electric, and Max Factor. But the suppliers had to learn that they couldn’t innovate ad libitum. The filmmakers laid down conditions for what would work onscreen and what would fit into efficient craft routines. In turn, the routines could be adjusted if a new tool yielded artistic advantages. And the whole process was complicated by an element of trial and error. The film community often couldn’t say in advance what would work; it could only react to what the supply firms could provide.

Moreover, once the stylistic menu was standardized, it reinforced and sometimes reshaped the mode of production. At every turn we found these mutual pressures, a mostly stable cycle among tools, artistic techniques, and business practices. Once the studios became established, they needed to outsource the development of new lighting equipment, camera supports, microphones, make-up, and other tools. A supply sector grew up, carrying names like Eastman, Bell & Howell, Mole-Richardson, Western Electric, and Max Factor. But the suppliers had to learn that they couldn’t innovate ad libitum. The filmmakers laid down conditions for what would work onscreen and what would fit into efficient craft routines. In turn, the routines could be adjusted if a new tool yielded artistic advantages. And the whole process was complicated by an element of trial and error. The film community often couldn’t say in advance what would work; it could only react to what the supply firms could provide.

In the late 1920s, for instance, sound recording made the camera heavier than the tripods of the silent era could bear. Supply firms engineered “camera carriages” that could wheel the beast from setup to setup. But this development occurred soon after filmmakers had noticed the expressive advantages of the “unleashed camera” in German films and some American ones. So the camera carriage became a dolly, redesigned to permit moving the camera while filming. It’s not that there weren’t moving-camera shots before, of course, but with the camera permanently on a mobile base, tracking and reframing shots could play a bigger role in a scene’s visual texture. Similarly, studio demands for ways of representing actors’ faces in close-ups forced Technicolor engineers back to their drawing boards again and again. Once the problem of rendering faces pleasant in color was solved, filmmakers could then redesign their sets and adjust their make-up to suit the vibrant three-strip process. And the interaction of work, tools, and style triggered larger cycles of activity. The need to pool information about stylistic demands and technological possibilities helped foster the growth of professional associations and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

This give-and-take among the studios, the supply sector, and the stylistic norms had never been discussed before, and we couldn’t have done justice to it in separately published books. Nor could isolated studies have easily traced how industrial discourses—the articles in trade journals, the communication among the major players—helped weld the mode of production to artistic choices about filmic storytelling.

The Classical Hollywood Cinema was generously reviewed, in terms that made us feel our hard work had been worth it. Books we’ve written since haven’t been so widely acclaimed. (Nothing like peaking young.) We’re grateful to the reviewers who praised the book, and to the teachers and students who have strengthened their biceps by picking it up to read. Of course there are others who don’t consider the project worthwhile; the TLS reviewer called it “sludge.” Probably nothing we say in the accompanying essay will persuade those readers to take a second look. Without responding to all the criticisms the book received (that would take a book in itself), our accompanying essay tries to position this 1985 project within our current lines of thinking.

We studied how Hollywood routinized its work, but that doesn’t mean that we think division of labor is always alienating. It may produce a much better outcome than do the efforts of a solitary individual. For us, that’s what happened during this rewarding exercise in collaboration.

Our thinking was shaped by many sources; here are some of them.

For André Bazin on “the genius of the system,” see “La Politique des auteurs,” in The New Wave, ed. Peter Graham (New York: Doubleday, 1968), pp. 143, 154, and “The Evolution of the Language of Cinema,” in What Is Cinema? ed. and trans. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), pp. 23-40. Christian Metz explains the Grande Syntagmatique of the image track in “Problems of Denotation in the Fiction Film,” Film Language, trans. Michael Taylor (New York: Oxford University Press, 1974), 108-146. Raymond Bellour’s essays of the period are available in The Analysis of Film. Thierry Kuntzel’s essay on The Most Dangerous Game was translated into English as “The Film-Work 2,” Camera Obscura no. 5 (1980), 7-68. An important gathering of essays in this line of inquiry is Dominique Noguez, ed., Cinéma: Théorie, lectures (Paris: Klincksieck, 1973).

Noël Burch’s early ideas are set out in Theory of Film Practice, trans. Helen R. Lane (New York: Prager, 1973). Even more important to our project was Noël Burch and Jorge Dana, “Propositions,” Afterimage no. 5 (Spring 1974), 40-66, and Burch’s To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in Japanese Film (London: Scolar Press, 1979), available online here.

Raymond Durgnat’s series, “Images of the Mind,” deserves to be republished, preferably online. The most relevant installments for this entry are “Throwaway Movies,” Films and Filming 14, 10 (July 1968), 5-10; “Part Two,” Films and Filming 14, 11 (August 1968), 13-17; and “The Impossible Takes a Little Longer,” Films and Filming 14, 12 September 1968), 13-16. Stephen Heath’s analysis of Touch of Evil may be found in “Film and System: Terms of Analysis,” Screen 16, 1 (Spring 1975), 91-113 and 16, 2 (Summer 1975), 91-113.

Barry Salt’s Film Style and Technology: History and Analysis (London: Starword, 1983) works in comparable areas to CHC, though without our interest in industry-based sources of stability and change. The newest edition is here.

Tino Balio’s courses and his collection The American Film Industry (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1976) had a substantial influence on us. He has been a wonderful friend and guide for us all since the 1970s. Our friendship with Douglas Gomery dates from our early days in Madison. Many conversations, along with his teaching in our program, shaped our thinking. A good summing up his of decades of work on the business and economics of Hollywood is The Hollywood Studio System: A History (London: British Film Institute, 2008).

Some of the stylistic traditions discussed in this entry are discussed in my On the History of Film Style. Several blog entries on this site fill in more details; click on the category “Hollywood: Artistic traditions.”

PS 26 September 2010: Douglas Gomery reminds me that the idea of sampling Hollywood films in an unbiased fashion–one feature of our method in CHC–was suggested to us by Marilyn Moon, economist extraordinaire. I’m happy to thank Marilyn, along with Joanne Cantor and Douglas himself, who helped us devise a sampling procedure.

Actors and set for Blondie Johnson (Warners, 1933).

Tintinopolis

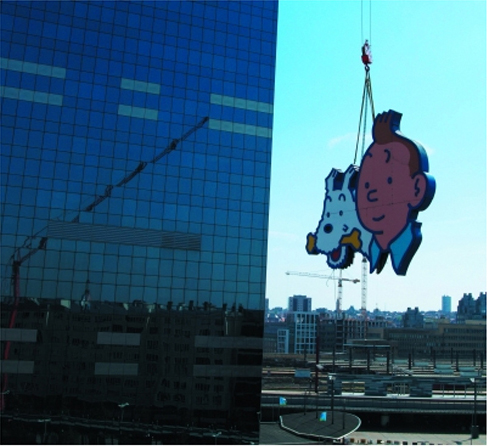

Photo by David Bordwell, July 2009. Tous droits réservés.

DB here:

He’s the world’s most famous fictional Belgian, miles ahead of Hercule Poirot. But I ignored him for about sixty years. Tintin wasn’t part of my childhood, and I didn’t get interested in his adventures until recently. Now, though, the scales have fallen from my eyes and I realize that Hergé is a great comics artist. And naturally I see him doing some things that shed light on cinema.

I came to the work obliquely. Since the 1980s Kristin and I have admired the Dutch cartoonist Joost Swarte. When we started to collect his books, lithographs, and CDs back in the 1980s, he was becoming known in the US through Art Spiegelman and Francois Mouly’s Raw. We were much taken with Swarte’s exact drawing style and mordant wit. I then got interested in the crisply drawn “clear line” tradition of French, Belgian, and Dutch cartoon artists stemming from Hergé—Chaland, Floc’h, Goffin, Ted Benoît, etc.—but I still didn’t pay much attention to the master himself.

This spring I gave a talk on La Ligne Claire to Kristin’s reading group, which explores fantasy (especially Tolkien), science fiction, comics, movies, and almost everything else. In preparing that, naturally I had to go back and read Hergé. Now I’m a believer. Some day I may polish that presentation and put it up as a web essay, but for now I just offer some notes, sojourning as I was recently in Tintin’s home town.

His own museum

Photograph copyright Nicholas Borel; Christian de Portzamparc, architect.

Brussels has its own superb museum of comic art, the Belgian Comic Strip Centre in Rue des Sables. Last year, however, the Musée Hergé opened in Louvain-La-Neuve.

Louvain-La-Neuve is itself an unusual place: a town created more or less from scratch when the Catholic University of Louvain split off from the Dutch-speaking University of Leuven. Originally designed for students, the town now has a population of about 30,000, with many citizens commuting to jobs in Brussels. This planned city has been hailed as a model of urban design; parking and car traffic, for instance, are underground.

Go through the square to a wooded park and soon you’re in the Musée Hergé. It is one those buildings that aim to awe you. There are few right angles, and huge spaces are dominated by pyramids, cylinders, and other three-dimensional solids, all in muted colors and bearing the sorts of squiggles Herge might use for foliage.

Photograph copyright Nicholas Borel; Christian de Portzamparc, architect.

Architect Christian de Portzamparc‘s statement of principles is here.

The first floor consists of the lobby, rest rooms, a restaurant, and a space for temporary exhibitions. As luck would have it, a tribute to Joost Swarte’s 40-year career was on display, and it was jammed with material. I could easily have spent the whole day here, even though I’d seen much of the material before. Swarte was also the “scenographer” of the Musée, offering ideas on interior design and decoration. The witty museum logo, as well as details like the signage, seem to be Swarte’s creations.

The first floor consists of the lobby, rest rooms, a restaurant, and a space for temporary exhibitions. As luck would have it, a tribute to Joost Swarte’s 40-year career was on display, and it was jammed with material. I could easily have spent the whole day here, even though I’d seen much of the material before. Swarte was also the “scenographer” of the Musée, offering ideas on interior design and decoration. The witty museum logo, as well as details like the signage, seem to be Swarte’s creations.

According to the guidebook, 80 % of Herge’s working material survives. This mountain of sketches, layouts, inked pages, color pages, and the like gives the curators a huge amount to pick from. Although the exhibition halls don’t feel stuffed, you quickly realize that you are in for total immersion.

You start at the third floor, and the first room supplies a survey of Hergé’s career. The information on the walls is pretty skimpy; the details are offloaded onto the headset commentary, I suspect. Charles Trenet’s ditty “Boum!” is playing over and over in this room, presumably not as an homage to Toto le héros but as a broad gesture to the interwar period. There are some intriguing Hergé illustrations here, including a 1939 political cartoon showing a Belgian shaking his fist at German planes flying over Brussels and shouting, “Dirty Boches!” before running to hide in his basement.

Another room is devoted to Hergé’s commercial art–posters, magazine advertisements, and book covers (including one for Christ, King of Business, 1929). Also on display are some striking images from less-known Hergé comic series, such as Quick and Flupke, Tom and Millie, and especially Jo, Zette, and Jocko. From here you move to a room devoted to the characters. Each one (except Tintin) gets a vitrine full of imagery. The final room on the floor is devoted to the cinema. The displays trace many of the situations and characters that Hergé borrowed from films of the 1920s and the 1930s. There’s also a filmed biography of Hergé screening on a loop.

The second floor was what held my interest most intently. One room includes a huge display of research materials for each book–not only notes and photos, but artifacts too. There’s also a case showing early Tintin games, toys, apparel, and other merchandise. The next hall gets to the root of my interest, Hergé’s creative process. Several displays trace the progress of a single page from rough layout to final coloring and printing. He was quite explicit about his aesthetic: Color is applied uniformly, with no shading, which yields “une grande lisibilité.” As I’ll suggest below, story legibility is central.

In this display room as well you can see how Hergé designed pages for periodical publication in landscape mode, then redesigned them for the vertical book format. That entailed cutting out panels, drawing new ones, and even changing gags. The books would then sometimes be recast for later editions. All these multiple versions have kept Hergé scholars busy for decades.

At about age 40 Hergé began to take on collaborators, and he eventually created a team of scenarists, lettering specialists, inkers, painters, and the like. In the next display room, you can see a TV documentary touring the studio and interviewing staff. This room also includes some gorgeous black-and-white ink drawings of pages and one-off projects, like Christmas cards. Your tour of the Museé ends with a room devoted to Hergé’s fame, starting with the famous wishes sent by Alain Saint-Ogan, creator of the breakthrough French comic strip Zig et Puce. In here you find praise from Balthus, Philip Pullman, Andy Warhol, and Alain Resnais: “Belgium belongs to the realm of fantasy. I found this out through reading Tintin.”

All in all, an exhilarating place to visit. It is unabashedly a tribute to Hergé and makes no effort to invoke the controversies around the man. I could find no reference to his wartime career and the political controversies that followed, to his divorce, or to the spiritual quest of his later years. This is the modern art museum in wholly celebratory mode. Still, few exhibitions of comic art I’ve seen make such a persuasive case for the enduring quality of an artist’s achievement.

Cinema on the page

I have taken from the current cinema its devices of découpage: once a character becomes important, you show what he’s doing, you vary the shots, you show the same scene from far off and then quite close.

Hergé, 1939

I’m a man of order, you see, even in drawing. I draw orderly things so one can read what I am drawing.

Herge, 1975

All comic strips and books remind us of cinema in one way or another, and many researchers have analyzed the affinities. The panels can simulate cutting, or panning camera movements, or even the fixed frame in which actions unfold over time. (Blondie is a classic example.) Artists have provided unusual angles and dynamic compositions that have a filmic feel. And like films, comics are usually narratives, stories told in pictures, so we can study how different comics artists use point-of-view, plot structures, suspense, and the like. (I did this last year with a recent twist in the Archie series.)

Most commentators on Hergé mention that he was a film fan and drew many situations from movies of the 1920s and 1930s. Like Hollywood studio cinema, his tales put striking technique in the service of fluent storytelling. Pause to study the narrative and you’ll find a surprising richness to the imagery; start by looking at the pictures as pictures, and you’ll see how composition, color, and detail smoothly advance the action. Hergé was well aware that his polished imagery could stand scrutiny in its own right, but he saw it as serving a larger narrative dynamic. He noted (my emphasis added):

I don’t try only to tell a story, but rather I try above all to tell a story. There’s a slight difference.

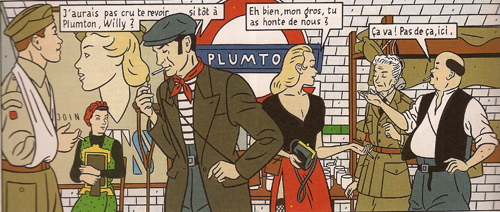

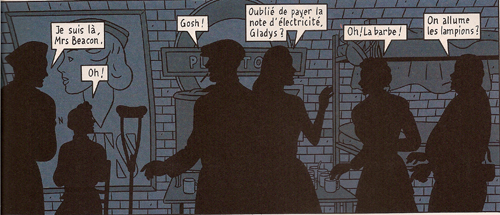

We can get a sense of this approach by contrasting it with one of the best Clear Line followers. Jean-Claude Floc’h’s albums are retro studies of a cozy, more or less imaginary England of the 1920s through the 1950s. He has provided his main characters, Francis Albany and Olivia Sturgess, with fake biographies that tie them to real artistic circles of the period. A series of books set in wartime (Blitz, 1983; Underground, 1996; Black Out, 2010) presents gorgeous tableaux. Here are two panels from facing pages of Underground. Londoners are huddling during a Nazi bombing run.

The images are designed to be compared in detail; we’re to note the slight changes in figures’ position. The story halts while you study the panels (and admire the artist’s finesse). This is technique calculated to dazzle.

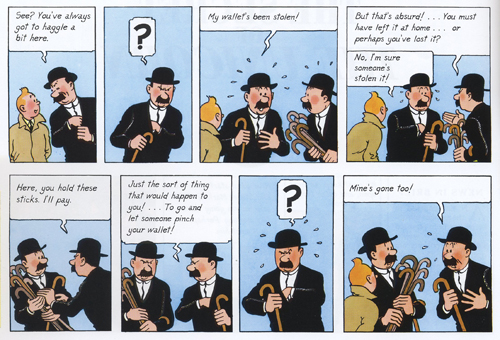

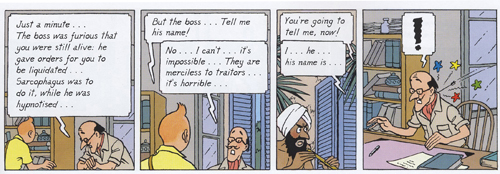

Hergé’s pages warrant the same sort of scrutiny, but you aren’t invited to dwell on them through a flagrantly overdesigned layout. The echoes and rhymes in this passage of the final English-language version of The Secret of the Unicorn are at least as intricate as Floch’s, but they’re at the service of symmetrical gags nestled in a broader comic buildup. Thompson and Thomson have had their pockets picked in a street market.

Hergé erases the background detail to allow us to concentrate on the graphic play of the black-suited figures (“spotting blacks,” as it’s called in the trade). The second panel reverses Thom(p)son’s attitude in the first, and both find a neat mate in the next-to-last panel. The third panel on top is rhymed with the last panel on the bottom. In between, the interplay of the two detectives is given in slightly varied compositions, with the extra walking sticks shifting around in their own patterns. The gag is a variant of the basic premise of Thompson and Thomson’s existence: they are mirror-images in all they do and say.

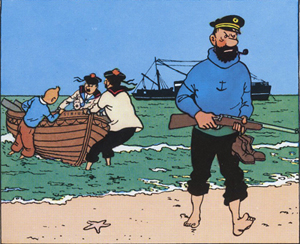

Given this play of variations, how does Hergé achieve narrative flow? One factor is the width of the panels, expanded or pinched according to the information in each and coordinated rhythmically across the page. Hergé also avoids gesture lines. Instead, one panel presents a point of motion as if captured by snapshot, and then the next panel provides the next phase of the movement. We might notice as well how the left-to-right propulsion of his drawings lays out narrative elements concisely. He declared this panel, from Red Rackham’s Treasure, one of two images that gave him most satisfaction:

Solely through the drawing, which shows the captain striding onto the beach with naked feet while his companions haul their boat onto shore, the viewer-reader [spectateur lecteur] mentally reconstructs everything that has already happened: The Sirius was put at anchor, the rowboat was lowered, Tintin and his companions set out; they have rowed to arrive at the island, where the captain climbed out. . . Everything that preceded the action shown in the drawing is expressed by a single composition.

Here’s another subtle technique Hergé used to make his stories flow. Psychologists speak of the “priming” effect. You’ll notice something faster if it chimes with something you’ve recently encountered. The classic experiment uses a string of words. If you’re first shown the word yellow, you’ll identify the word banana faster than if the trigger word is red.

Priming is a basic filmmaking resource. What the screenwriter calls “planting”–the pistol on the mantelpiece in Act I–is a type of longer-range priming. On a smaller scale, one purpose of an establishing shot is to prime certain areas of a locale for future action. Here’s a simple example from Norman Taurog’s The Caddy (1953). Jerry Lewis is fleeing from a pair of German Shepherds and he takes refuge in a men’s changing room.

A new shot shows him closing the door, and it makes prominent the coat rack nearby. Eventually Jerry notices it and expresses happiness as only Jerry can.

Using the robe and beret hanging there, he tries to disguise himself.

A close look at my first frame shows that the coat rack was (subliminally?) primed in that shot too; you can glimpse it when Jerry opens the door. This reminds us that the filmmaker can prime our response by including a little something at the end of one shot that ties it to the next. Both Spielberg and Johnnie To are skilful at this; see earlier blog entries (here and here) for examples.

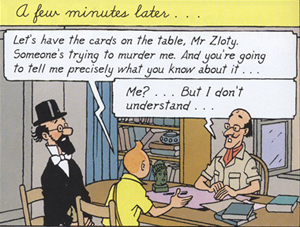

It seems to me that Hergé makes use of fine-grained priming in the flow of his panels. Here’s an example from the final English-language version of Cigars of the Pharaoh. The “establishing shot” shows Tintin and Sarcophagus consulting Zloty. The composition is simple and balanced, with Tintin as the fulcrum. The window behind Zloty is unobtrusively primed.

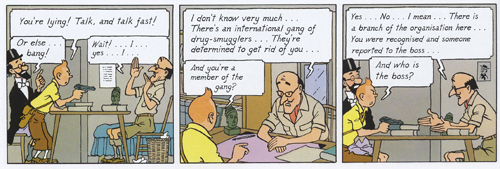

The next stretch of panels breaks this overall layout down into two sorts of shots: a profile view and an over-the-shoulder view of Zloty.

The first and the third panels are variants, with the framing getting closer as we proceed. Hergé often propels his story through these tighter framings, as if to ratchet up the tension in a filmic way. The more compressed array of figures at the end of the series also allows for more spacious speech balloons, always a major consideration in the Tintin saga. Hergé didn’t reiterate the window in every framing; only the middle panel re-primes it through our angled view of Zloty.

Now the framing will get even tighter on Tintin and Zloty, losing Sarcophagus altogether, and the window will become more salient, even though it’s still a minor element of each design.

The massive balloon at the top of the first frame in this series obliges Hergé to push his figures quite low, but he compensates by letting them lean on the bottom edge as if it were the desktop. (Hergé likewise often makes his characters stand directly on the frameline.) The first panel retains the window frame. The second, another over-the-shoulder shot but even tighter than the first, introduces the shutters in a prominent position behind Zloty. These shutters prime the third frame. They now anchor a crucial action: the Fakir is lurking outside those shutters.

The final panel provides the payoff. The open window frame that seemed at first just a realistic detail becomes necessary to understanding the action. It could have been established in a wider shot, but in keeping with his urge for economy Hergé has primed it in the most compact way possible–as a peripheral element, in the background or on the frame edge. (Compare Taurog’s thrusting the coat rack under our noses.) You have to wonder if such economy of expression will be on display in the Spielberg-Jackson Tintin movie project.

I know, I know: David, it’s just a window. Or: David, it’s just a comic strip. But as film students we ought to be interested in how images shape our experience, and we can learn from any craftsmanship as precise and engaging as Hergé’s.

For more on the Clear Line style, see the series of articles at Paul Gravett’s excellent site.

The official Tintin website is available in an English version here. Since photography is not permitted in the Musée, for illustrative purposes I have drawn on the official images on the building’s website, with copyright and credit as noted in the captions. Bart Beaty, expert on Eurocomics, provides a carefully considered report on his trip through the galleries. The Musée’s catalogue is a trilingual survey of major items on display, although it neglects to illustrate changes in layouts across different editions.

On the aesthetics of comics and cinema, see Manuel Kolp, Le Langage cinématographique en bande dessinée (Brussels, 1992). Principles of page composition, including spotting blacks, are explained in Gary Spencer Millidge, Comic Book Design: The Essential Guide to Designing Great Comics and Graphic Novels.

The best general introductions to Hergé’s artistry seem to me to be Benoît Peeters’ Tintin and the World of Hergé and Michael Farr’s Tintin: The Complete Companion. Both offer occasional comparisons of different editions of the books. See as well Philippe Goddin’s multi-volume set of primary materials. Goddin supplies a shorter sampling of the artist’s creative process in his charming but now rare Comment naît une bande dessinée: Par-dessus l’épaule d’Hergé. For an example of in-depth inquiry into the various changes that a tale underwent from one edition to another, see Étienne Pollet, Dossier Tintin: L’Isle noir: Les Tribulations d’une aventure.

My first and fourth Hergé quotations come from Bob Garcia’s Hergé et le 7ème art, pp. 6 and 9. My second quotation is taken from the English edition of the Musée Hergé guidebook (Moulinsart, 2009), p. 48; I don’t find it to be available for purchase online. My third quotation comes from Numa Sadoul’s Entretiens avec Hergé: Tintin et moi, p. 46. According to Harry Thompson in another good introduction, Tintin: Hergé and His Creation, the young Hergé wanted to be a film director (p. 26).

A very extensive web resource on Floc’h is here. As for Archie’s wedding: It did turn out to be one of those parallel-universe stories. It has developed over seven issues since last September in a “mini-series.” Abrams will be publishing a special collector’s edition, according to the press release, “for the Archie fan in all of us.”

This is probably as good a place as any to mention that Intellect Press has just launched a new journal, Studies in Comics. Details, as well as downloadable essays from the first issue, are here.

PS 24 January 2011: This essay was named one of the best pieces of online comics criticism of 2010 in an exercise conducted by The Hooded Utilitarian of The Comics Journal. What an honor! Thanks to the judges, and congratulations to the other writers who earned places on the list.

Les dessins, textes et symboles extraits de l’oeuvre de Hergé cités dans ce essai sont la propriété exclusive de © Moulinsart S. A. ou © Hergé ou © Casterman et sont montrés à titre de référence et d’exemple.

Photo, uncredited, from this site.