Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

Now you see it, now you can’t

DB here:

We usually respond to films spontaneously, but afterward we can think about our responses and figure out why we reacted as we did. When we’re fooled by a mystery, for instance, we can re-watch the film and trace exactly how we were misled. Now that Shutter Island is out on DVD, fans will be dissecting its visual gimmicks. Even when a film isn’t a mystery, a lot of critical analysis involves what we might call a rational reconstruction of how the whole shebang works. Novice screenwriters crack open a movie like The Apartment or The Godfather to peer into the fine mesh of plot construction, to tease out all the setups and plants and twists that seem inevitable only after the fact.

This is film research, we might say, at the personal level. Not in the sense of your or my unique identity, but rather at the scale we see the world. We don’t see atoms or gravity. We evolved to sense and think about middle-sized social and physical phenomena, like places and objects and, especially, other humans. We’re aware of the world because we sense ourselves as individual agents, guided by intentions and desires and beliefs. We’re used to talking about films at this level. When we track action and character, note surroundings and time passing, or ask about the purposes of a plot device or theme, we are working at the level of personhood.

But life assigns us to other levels too. There is the subpersonal level. All kinds of things are happening to you now that you can’t be aware of. You can’t watch the cells in your retina detect this sentence, or the neurons in your brain firing to make sense of it, or the flow of signals to your hand urging the mouse to scroll onward. A huge amount of our mental activity takes place behind the scenes that flit through our consciousness. We can’t pay attention to the man behind the curtain—partly because there is nobody there.

There’s also the suprapersonal level, the level of collective behavior patterns. Now we’re talking about people as parts of large-scale forces, like groups and cultures and societies. Historians have traditionally worked at this level. For example, some researchers have traced how film audiences, en masse, have responded to movies.

More strikingly, many scientists now study “self-organization”—the emergence of patterns of order that don’t seem to be willed or intended by individuals or groups. We find impressive instances in nature: fish swim and birds flock in intricate patterns that no one fish or bird could imagine or dictate. Such self-organization is even more striking in human activities like traffic flow or online networks. Is there a sort of “physics of society”? No doubt people have intentions and quirks, but often we can bracket those out and see shapes in the data that no one could have designed. The classic instance is a power law. A remarkable example is Vilfredo Pareto’s discovery that income distribution in any society tends to settle out as 20 percent of the people controlling 80 percent of the wealth. Mark Buchanan sums up the suprapersonal viewpoint this way: “Think patterns, not people.”

We know we can study films at the personal level. How can we study films subpersonally and suprapersonally too?

Reverse-engineering a movie

Mon Oncle.

My answer comes after four days earlier this month at the annual convention of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. We met in Roanoke, Virigina, in a massive nineteenth-century hotel made over into a convention center. You know the place has things under control when every PowerPoint presentation works flawlessly.

What ideas unite the film scholars, psychologists, and philosophers who gathered here? Roughly, the members explore moving-image media through empirical methods. Empirical inquiry can include classic scientific method (hypothesis/ experiment) or methods of aesthetic, historical or quantitative analysis. Typically the goal is not interpretation of a particular film or TV show or videogame but rather understanding of some general aspects of these media. Not explication, we might say, but rather explanation. Further, most members of the Society are interested in ways that film can be illuminated by areas of modern psychological research, such as neuroscience, cognitive science, and evolutionary psychology.

Some of our philosophers would say that they pursue conceptual analysis rather than empirical inquiry. Still, they join our meetings because the sorts of concepts they want to analyze are the ones that the film folk and the psychologists deploy—concepts like artistic intention or the nature of genre. Many of our liveliest sessions have come from disputes between Filmies, Psychos, and Philosophes.

For more on what we do, I’ve offered some background in earlier entries on this site. I previewed the 2008 convention here and here. I previewed the 2009 convention here and here.

Previews, but not followups. The big problem covering these events is that they’re so busy I have no time to blog during them, and by the time they’re over I’m usually en route to Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna. So I tended to make those entries introductions to the cognitive perspective, rather than surveys of who said what. This year, because our gathering was earlier than usual, I’m trying to sum up the event reasonably soon after it ended. We had simultaneous sessions, sometimes three at once, so I attended fewer than half of the talks. I’ll try to mention presentations that seem relevant, even if I didn’t hear them. Similarly, I heard some presentations (e.g., Lisa Broad on possible worlds) that were stimulating but don’t quite fit into my thesis here.

There were plenty of talks that developed arguments at the level I called personal. That is, they analyzed how films were designed to achieve certain effects. This calls for “reverse engineering”: starting from plausible viewer responses and then looking for creative choices made by the filmmakers that seemed to fulfill particular functions.

Take as an example Carl Plantinga’s paper on how we strike up moral attitudes toward characters. He was interested in how we achieve what Murray Smith calls “allegiance”—a “pro-attitude” toward certain characters. Is it just a matter of wishing good things for them, or admiring their positive traits? Is it a matter of sympathy for their situation?

Take as an example Carl Plantinga’s paper on how we strike up moral attitudes toward characters. He was interested in how we achieve what Murray Smith calls “allegiance”—a “pro-attitude” toward certain characters. Is it just a matter of wishing good things for them, or admiring their positive traits? Is it a matter of sympathy for their situation?

Carl argued that all these factors play a role, but they aren’t enough to assure our siding with a character. He argues that allegiance also involves moral judgments, or rather moral intuitions. Films exploit two facts about these moral intuitions: they must be summoned up quickly, without much thought, and they are often driven by emotion rather than ideas.

Oddly enough, our moral intuitions are not necessarily driven by moral standards! Carl drew on Anthony Appiah’s analysis of moral judgments as influenced by how a situation is framed, ordered, and primed—basic cognitive cues that influence responses. For example, Legends of the Fall sets up two brothers, one conventionally moral and the other not. Yet it’s the wild, violent Tristan who earns our sympathies, because he displays vitality, youth, beauty, sensitivity, and closeness to nature. The upshot is that we rationalize a moral judgment on non-moral grounds. Carl got several questions about his conception of morality and the possibility that our moral intuitions are tied to things we value, like beauty.

Malcolm Turvey offered a paper on gags in Jacques Tati. Pointing to prior work on how Tati’s gags are integrated into a shot’s composition (scattered so that we may miss them) and linked to one another (through overlap, Kristin has suggested), Malcolm went on to argue that the gags themselves don’t obey the conventions of classic comedy. They exhibit strategies of misinterpretation, blockage, ellipsis, fragmentation, and concealment that are highly original and unusually challenging. Malcolm is working on a book on “ludic modernism,” and he sees Tati as fitting into this tradition.

Malcolm’s precise and persuasive account was framed by a strong attack on the tendency of cognitive film theory to concentrate on ordinary, even undistinguished films and ignore problematic and avant-garde instances. He pointed to passages in Stephen Pinker’s writings that mock experimental art, and he urged cognitive film researchers to “call Pinker out” for his borderline Philistinism. He remarked that psychological researchers could learn as much from Tati’s work as from ordinary films…and maybe discover new things.

A similar sort of rational reconstruction at the level of personal response was found in many other papers I heard. Jason Gendler dissected the misleading narration in The Blue Gardenia. Rory Kelly wondered why viewers tend to forget the water-utility plotline at the start of Chinatown. James Fiumara considered why modern startle effects are comparatively rare in classic horror films. Torben Grodal isolated a group of “disgust-driven phobic films” (Taxi Driver, Blade Runner, Se7en) that sink so deeply into disgust that melancholy drives out empathy. Lennard Hojberg studied circular camera movements that express the dizziness of love as based on embodied vision.

A similar sort of rational reconstruction at the level of personal response was found in many other papers I heard. Jason Gendler dissected the misleading narration in The Blue Gardenia. Rory Kelly wondered why viewers tend to forget the water-utility plotline at the start of Chinatown. James Fiumara considered why modern startle effects are comparatively rare in classic horror films. Torben Grodal isolated a group of “disgust-driven phobic films” (Taxi Driver, Blade Runner, Se7en) that sink so deeply into disgust that melancholy drives out empathy. Lennard Hojberg studied circular camera movements that express the dizziness of love as based on embodied vision.

Some researchers used quantitative procedures to capture a film’s regularities. Monika Suckfuell (right) exposed some very complex patterns in a short film, Father and Daughter. These create a distinct emotional tone through what she calls “distance editing.” The patterns are combinations of thematic units like problem-solving or humor, and the recurring combinations arouse both comprehension and pleasure. In another quantitative study, Tseng Chiaoi and John Bateman sought to tie concrete uses of filmic elements with more abstract aspects of meaning. (Chiaoi and John had done a presentation on film-based discourse semantics at last year’s event.) Concentrating on characters’ action patterns, Chiaoi used computer software to trace their structures in television commercials and the war genre.

Squeezing the stimulus

Bopping after a session: Tseng Chiaoi and Paul Taberham.

The talks I’ve mentioned, along with several others, analyze processes that we can access by re-viewing films, studying their form and materials, and examining the genres and stylistic traditions to which they belong. But other talks concentrated on the subpersonal areas, the parts of our responses that we can’t access so easily.

For instance, how do we mentally stitch together various shots to create a unified space for a scene’s action? Film scholar Todd Berliner and psychologist Dale Cohen presented an account of how we achieve an illusion of spatial continuity. Initially the brain grasps shots as if they were pieces of space selected by the viewer, and then it builds up a model of the whole space—say a porch in front of a house’s front door. When a character moves his arm a certain way toward an offscreen area, our model of porches and doors makes it most probable that he is pressing the doorbell.

For instance, how do we mentally stitch together various shots to create a unified space for a scene’s action? Film scholar Todd Berliner and psychologist Dale Cohen presented an account of how we achieve an illusion of spatial continuity. Initially the brain grasps shots as if they were pieces of space selected by the viewer, and then it builds up a model of the whole space—say a porch in front of a house’s front door. When a character moves his arm a certain way toward an offscreen area, our model of porches and doors makes it most probable that he is pressing the doorbell.

In such ways we run “beyond the information given.” Filmmakers count on our doing that, so they give us feedback (say, the sound of a doorbell, or a shot of a door opening) that confirms our model of the space. Most mainstream films build in such redundancy. But the unity of these spaces is undermined by some contemporary exhibition technology. Todd and Dale suggested that the mental models we build of space exclude the movie theatre, so that surround sound and 3D become problematic.

They also got several good questions. How concretely specified are these model spaces? How do they develop in the course of a scene? Might our perception of continuity come down to a lack of perception of discontinuity—that is, maybe we operate on very simple default assumptions and don’t build up many models of the space.

Todd and Dale’s presentation was in the Helmholtz tradition; they even invoked “unconscious inference” as part of the story. Another tradition, represented by SCSMI founders Joseph and Barbara Anderson, invokes James J. Gibson’s ecological approach to perception, which argues that such modeling and inference-making isn’t really happening. Things are much more direct: Perception is data-driven, and needs top-down correction only in rare cases (like nighttime or fog).

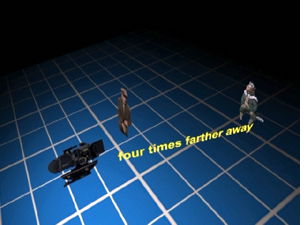

Other perceptual researchers try for a more parsimonious research strategy: How much information about the visual world can we squeeze out of the stimulus? This question was raised by Jordan DeLong, who has been exploring how we can identify emotional arousal through very “low-level” information. Using a corpus of 150 films (more on this later), he looked at shot lengths, the distribution of shot-lengths across a film, and a purely physical measure of visual activity (essentially the change from frame to frame) to see if they correlate with genres we associate with high levels of arousal, like action and adventure films. Jordan’s study is preliminary, but there is the possibility that certain purely physical features are reliable indices to levels of arousal—even if people don’t notice those features and are much more fastened on characters and their actions.

The current projects of Tim Smith’s research team exemplify the parsimonious strategy. Tim is a long-time participant in SCSMI, and his talks show how a research program can expand and enrich itself.

We know people look at certain areas of a shot. We also know that our attention is directed, driven by features of the stimulus. What features? We filmies would pick out shot composition, color, movement, lighting, shot scale, etc. We can access those middle-level variables through expert introspection and analysis. But can those features be further decomposed?

Tim thinks so. We can consider any of these technical qualities as made up of luminance, color channels, and other low-level physical aspects of vision. Through signal-detection methods, Tim seeks to pinpoint what the crucial variables are. The results of his work are soon to be published, and I don’t want to give the game away. I’ll just say that he has shown through eye-tracking that certain low-level features are more important than others in engaging viewers’ attention.

One implication of Tim’s findings is that what I’ve called “intensified continuity” seems to have an optimal grip on spectators. This technique, he remarked, “almost paralyzes the eyes,” yielding “an illusion of active vision with passive eyes.” More generally, his work seems to back up James Cutting’s remark that “There is no such thing as voluntary attention sustained for more than a few seconds at a time.” Most of our attention is at the mercy of the outside world, which means that filmmakers need to engage us at every moment—either with narrative, or with something else we’ll find arresting.

Dan Levin, Pia Tikka; in the background William Brown, Carl Plantinga, and Dirk Eitzen.

Dan Levin gave the keynote address at SCSMI two years ago, and he showed how we vastly overrate our ability to spot outrageous changes in the world or on the movie screen. (He’ll have a field day with the tricks in Shutter Island, such as the one surmounting this blog.) This time around Dan talked about Theory of Mind in the movies, the ways that films exploit our (species-specific?) inclination to attribute beliefs, desires, and goals to the creatures we see in the world, and in films. His paper scanned mandatory, bottom-up cues, middle-level activity (the sort of organization of visual space Todd and Dale discussed), and then “controlled cognition,” such as our narrative expectations. So for Dan it’s not all in the stimulus. Once we’ve picked out certain aspects of it, our Theory of Mind system locks on them.

What aspects? Chiefly, signals of intention and marked eye direction. When we think we’re watching an intentional agent, like a movie character, we tend to see the agent’s eye direction as giving us a clue to his or her aims. Using films he has made, Dan tests people for how eyeline-matched cuts are read, and he varies the cues to see how people construe them differently.

Interestingly, when he showed the same shots in a different order, about two-thirds of the subjects didn’t notice that the order was different. That is, whether the object of the glance or the person glancing came first, gaze deflection remained the primary cue to understanding the situation. This suggests to me that storytelling cinema doesn’t absolutely need the classic pattern of person looking/ person looked at/ person looking, but the extra shot makes sure we all understand (redundancy again).

A similar sort of top-down/ bottom-up theory was proposed by Dan Barratt, who gave it a more computational spin. Like Tim, he works on eye movements; like Todd and Dale he’s interested in how we construct space; like Dan, he seeks out intentional factors. It’s not all in the stimulus, but we won’t know how much until we keep squeezing.

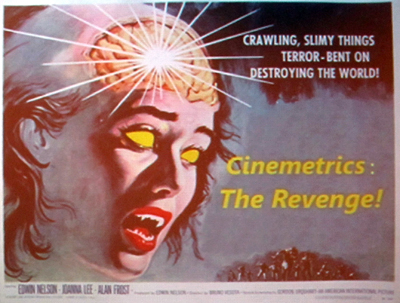

Ripples in the flow of films

The Society broke new ground in what I called the “suprapersonal” realm, that of large-scale patterns of activity that aren’t explicitly coordinated by individuals or groups. Several researchers are probing this in relation to films. Films are, in effect, deposits of human behavior; they are artifacts resulting from choice. What if we find patterns of choice that we can’t plausibly trace to coordinated decision-making?

Chris Atherton raised the issue by considering how to study style statistically. Citing Barry Salt as a pioneer in the area, he focused on the work of the Cinemetrics group and offered suggestions on how to better collect data and track patterns at various levels of generality. More sharply, he posed the question of function. How can you measure that? One implication was that in a big body of films we can disclose order that can’t wholly be explained as the sum of individual choices. Those choices matter, but so do forces we have yet to determine, including historical processes. Chris’s reflections chimed nicely with those of our keynote speaker.

James E. Cutting is a distinguished perceptual psychologist at Cornell. He’s written a fine book on motion perception and has done a quantitative historical study of the creation of the canon of French Impressionist painting. He’s a former dancer and a sensitive appreciator of art and music (and film). He’s the ideal person to analyze ticklish aesthetic issues.

You may have run across him recently because his research on Hollywood films was picked up and trumpeted in the press. “Solved: The Mathematics of the Hollywood Blockbuster,” read one headline. Needless to say, James was doing something more subtle. You can read summaries here and here.

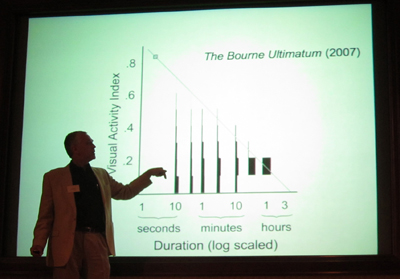

In his lively address, “Attention, Intensity, and the Evolution of Hollywood Film,” James explained two of his areas of interest: the ebb and flow of change across a film, and how that change is tied to human pickup. James studies these topics with a big database: 150 movies from 1935 to 2005. He emphasizes widely seen films belonging to five genres and chosen from the highest-rated titles on IMDB. But there’s a micro- side too. He and his research team went through every film frame by frame coding each one along many dimensions.

Naturally, he takes on the vexed issue of Average Shot Length. You can read the ongoing discussions of this concept on Yuri Tsivian’s Cinemetrics site. What interests James is less ASL in itself than the ways in which comparable patterns of shot lengths cluster in certain parts of the film. A film’s ASL may be 8 seconds, but in some passages several shots might have similar lengths, say 12 seconds each. Moreover, those patterns may “ripple through the film,” recurring at certain intervals and different scales (shot clusters, scenes, or other chunks).

Not every film shows such patterns; film noirs seem random in their patterns of shot lengths. But many movies, especially those of the last fifty years do display these patterns—typically clusters of short shots for physical action, clusters of longer ones for conversations. This clustering tendency is on the increase, even outside the action genre.

Not every film shows such patterns; film noirs seem random in their patterns of shot lengths. But many movies, especially those of the last fifty years do display these patterns—typically clusters of short shots for physical action, clusters of longer ones for conversations. This clustering tendency is on the increase, even outside the action genre.

The finding leads James to ask about the pacing of visual change, which raises the prospect of the sort of tension/ release dynamics we find in music. The patterns he finds don’t look arbitrary because they match the so-called 1/f or pink-noise pattern. This pattern has been detected in the natural world, in heartbeats, and in brain activity. It’s also been discovered in reaction times to tasks. In effect, the 1/f pattern captures not continual attentiveness but rather an alternation of intense concentration, moments of slower pickup, and moments of sheer mind-wandering. A nontechnical explanation of the 1/f pattern is here; a technical one is here.

As for intensity, James is seeking to measure visual activity in the shots. How much change, in effect, can there be from frame to frame? This can be captured by correlating each frame with its mates. James and his team find that from 1930 to 1950, there’s been a steady increase of frame-to-frame visual activity across all genres. The images became busier, with more movement. Today, he suggests, Hollywood is exploring ways to raise the frame-to-frame visual activity—not only through lots of movement of characters (the action film comes to mind) but also through “queasicam” handheld movements.

In combination with decreasing ASLs, Hollywood seems to be asking: How briefly can I show you this and still get the point across? So far, James suggests, films like Mission: Impossible III and The Bourne Ultimatum seem to be the busiest at the visual level. But animated films score about the same.

James has a caveat: The size of the screen matters. Even a big home-theatre screen doesn’t duplicate the breadth of a theatre screen, which activates not only our central vision but our peripheral vision too. That’s why bumpy shots that you can tolerate on a computer monitor may make you queasy at the multiplex. Interestingly, the Bourne films and Cloverfield, James suggests, were more popular on IMDB after the DVD versions came out. Perhaps people were better able to assimilate them on a smaller display.

At one level, James is interested in the subpersonal factors. He grants that you don’t notice cuts but can attend to them if you shift your focus from the story. But the widespread patterns he discloses aren’t easy to ascribe to deliberate planning. Nobody but an avant-gardist would decide to have shots of similar lengths at points 14 minutes or 25 minutes apart throughout the film. But James finds such correlations at levels beyond chance.

I can’t pretend to understand everything mathematical in James’ argument, but I think that his discoveries open up a new way to think about pacing in film. My first impulse is to think about historical causes, as Chris suggests: filmmakers learning from each other, converging on optimum choices. But I also like to entertain the possibility that this optimum carries a resonance even beyond the flux of history. Perhaps like fish and fowl, filmmakers are obeying and viewers are fulfilling, completely unawares, deep rhythms built into nature and numbers.

A tangled databank

Traditional humanists would decry a lot of what goes on at SCSMI meetings. The appeal to general explanations, the recourse to biology and evolution, the use of quantitative and experimental methods would all smack of “scientism.” But more and more, humanists are starting to turn away from the endless reinterpretation of canonical or non-canonical artworks. Many are also quietly defecting from the Big Theory that dominated the 80s and 90s. In film publishing, I’m told, editors have come to an informal moratorium on books on Deleuze. Possibly more people write them than read them.

Committed to a theory of permanent revolution in Theory, humanists are seeking new pastures. Some have discovered neuroscience, others evolutionary psychology. Franco Moretti has launched quantitative studies of the literary marketplace. For many converts, the reconciliation with science is just a bandwagon to hop onto, and they will jump off when a newer one trundles past. But other scholars have been committed from early on. The prospect of “consilience,” the compatibility between the sciences and the arts, is something the literary Darwinists like Brian Boyd, Jonathan Gottschall, Joseph Carroll, and like-minded souls were defending long before it became fashionable.

Film theory, as Joe Anderson is fond of pointing out, has a long and intense fascination with experimental psychology. Hugo Münsterberg, Rudolf Arnheim, and Sergei Eisenstein saw no conflict in studying film art with tools and findings derived from the sciences. That interest was lost in the 1960s, for a variety of reasons. But some of us have persisted. An explicitly “cognitive” perspective has been developing in film studies for the last twenty-five years, and SCSMI has nurtured this tradition since 1997. Our commitment is deep. We’re making headway. We’re not going to go away.

There is grandeur in this view of life, and cinema.

Our Society owes a great debt to Stephen Prince of the Virginia Tech School of Performing Arts and Cinema, who hosted this year’s convention. He also gave a splendid paper on the research traditions behind precinematic optical toys, as a way of thinking about modern CGI.

I found these books on suprapersonal patterns helpful: Mark Buchanan, The Social Atom: Why the Rich Get Richer, Cheats Get Caught and Your Neighbor Usually Looks Like You (London: Cyan, 2007); Steven Strogatz, Synch: The Emerging Science of Spontaneous Order (New York: Theia, 2003); Philip Ball, Critical Mass: How One Thing Leads to Another (New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 2004).

Todd Berliner and Dale Cohen’s paper, “The Illusion of Continuity: Active Perception and the Classical Editing System,” is scheduled for publication in the Journal of Film and Video in 2011. Tim Smith’s paper is in press at Cognitive Computation as P. J. Mital, T. J. Smith, R. Hill, and J. M. Henderson, “Clustering of gaze during dynamic scene viewing is predicted by motion.” You can check Tim’s DIEM project for video demonstrations, and his blog, Continuity Boy.

The original article by James Cutting, Jordan DeLong, and Christine Nothelfer, “Attention and the Evolution of Hollywood Film,” appeared in the March issue of Psychological Science. Access is through subscription.

As for Shutter Island, thanks to Justin Daering for pointing out the double sleight-of-hand. More thoughts on the film and Scorsese’s expressionist/ impressionist tendencies are in our backfile.

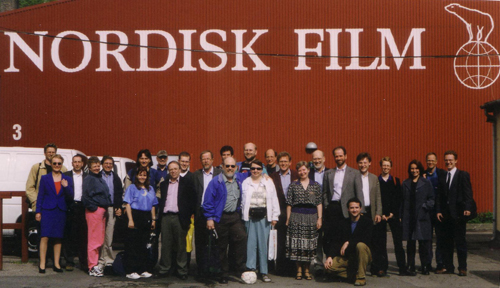

1999 Conference of the Center [later Society] for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image; Valby, Denmark. Photo by Johannes Riis.

Dreyer re-reconsidered

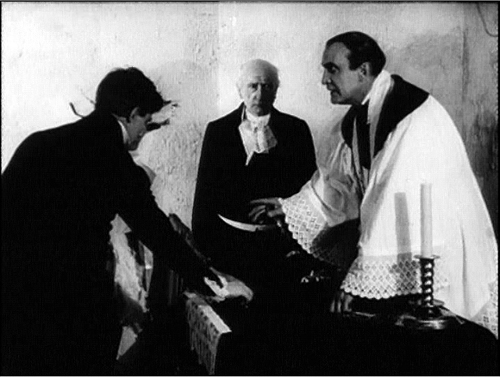

The President (1920).

DB here:

I was late to the feast, but my contribution to the Dreyer site is now up, thanks to Lisbeth Richter Larsen‘s quick work. You can read it here.

Danish cinema was the first national cinema I studied, and Dreyer was my point of entry. I went to Copenhagen in 1970 to see his films for a little book I wrote in the Movie/ Studio Vista series. The manuscript was finished but never published because the series ceased. Good thing for me. I’d be embarrassed today if that book was still floating out there.

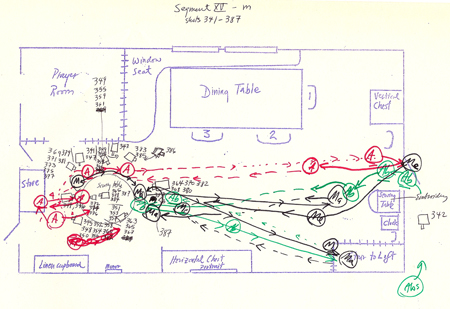

Kristin and I went back to Copenhagen in 1976 to re-watch the Dreyer oeuvre, and I saw the films with new eyes. I had learned a lot more about film analysis and film history, so I was able to see different things in his movies. Now obsessed with how films construct space and time, I drew up elaborate and clumsy plans of actor blocking, camera setups, and camera movements.

What? You don’t recognize this as a string of shots from Day of Wrath? I even notated actor movements offscreen (with dotted lines).

The result of all this fussbudgetry was a 1981 book on Dreyer. I think that some of the ideas there still hold up. But as I learned more about film history in the 1990s, I came to believe that some of my conclusions were off-base.

In particular, my treatment of Gertrud as a radical, deliberately “empty” film seemed tenuous. Influenced by minimalist cinema of the 1970s, especially that of Straub and Huillet (huge admirers of Dreyer), I pushed the case that at the end of his life Dreyer dared to make a movie that was by all ordinary standards simply boring.

Steadier heads tried to talk me out of it, but I clung to the idea. What can I say? I was young and stubborn.

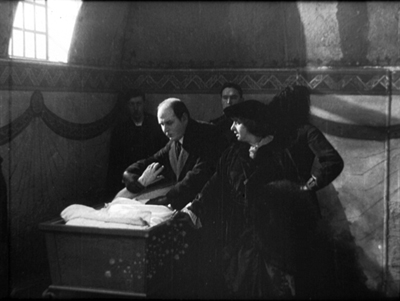

As I studied more cinema of the 1910s, I began to see Dreyer’s career, and particularly his silent films, as tied in complicated ways to other films of that period–not least Danish cinema. For, as I’ve sketched here, Danish cinema of the 1910s was one of the richest traditions of “tableau” staging in Europe. I was able to put my ideas about the Danes’ achievements into clearer form in the last chapter of On the History of Film Style and in an invited essay on the Nordisk company published in a collection at the Danish Film Institute.

Like their peers in other countries, the Danes often stuffed their shots with furniture and props, in a riot of patterns and textures. Here is an example from Den Frelsende Film (The Woman Tempted Me, 1916). It survives only in fragments, but those fragments are in fine shape.

In addition, the Danes developed elaborate lighting patterns and complex, somewhat Gothic special effects. You can see these options in Ekspressens Mysterium (Alone with the Devil, 1914) and Doktor Voluntas (1915).

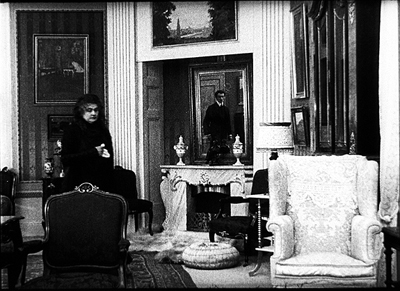

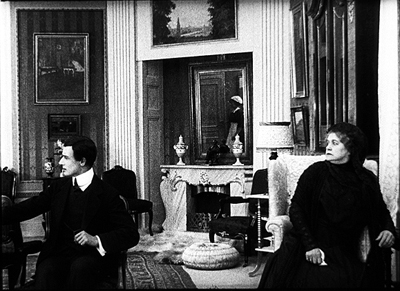

Above all there was the intricate staging in depth, often using mirrors. Here’s a seldom-seen example. In Under Blinkfyrets Straaler (Under the Lighthouse Beam, 1913), the father has died, and his wife and son meet in the parlor. A mirror catches them entering, in phases.

The mirror shows Hugo entering the room by moving straight and forward, but when he gets into the shot he comes in somewhat diagonally from the left.

After a moment of sitting in silence, mother and son turn as a maid enters. They look off left, but because we’ve seen Hugo enter in the mirror, we look to the center and see her reflection as she shuts the door.

The maid brings the widow a letter from her other son, Robert. Hugo, fretful, departs and in the mirror we see him look back at his mother.

Or does he? The angle of his glance makes sense compositionally: In reflection Hugo seems to be meeting his mother’s eyes, left to right. But in my first frame, he advanced into the room by looking straight ahead. If he looked straight into the room again now, he’d be looking more or less at us, not at his mother. So I suspect that in my last frame, the actor is actually not looking directly at the actress but off at an angle. He has been directed to this position to allow the mirror to create an artificial, but highly readable, image.

The novice Dreyer, I realized, didn’t indulge in such tableau trickery. His first two films, The President (made in 1918) and Leaves from Satan’s Book (made in 1919), are quite different from the norms that ruled his local cinema. By the time he came to directing, he was more oriented toward analytical editing and fairly flat staging than were the old guard. In this regard he was closer to a younger group of filmmakers emerging at the same time in other countries: Gance, Lang, Murnau, Joe May, and many others, along with Americans like Ford, Walsh, et al. So my newest take is that Dreyer is part of a generation of directors moving toward an editing-driven cinema and away from the tableau style. This idea in turn helped me see Gertrud in a more convincing light.

If you want the argument in full, you can check it on the Dreyer site. The lesson for me is twofold. (A) Dreyer is inexhaustible. (B) The more you learn about cinema (and about life), the more you can see in films that you think you have already understood.

The only book in English surveying the cinema of Dreyer’s elders is Ron Mottram’s indispensable The Danish Cinema before Dreyer (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow, 1988). It doesn’t consider the dual traditions of staging and editing, but it offers a very thorough history of studios, directors, and genres, and mentions some stylistic patterns. The article I referred to is “Nordisk and the Tableau Aesthetic” in Lisbeth Richter Larsen and Dan Nissen, eds., 100 Years of Nordisk Film (Copenhagen: Danish Film Institute, 2006), 80-95. This gorgeous book can be ordered from the DFI shop;I’ll be adding my essay here some time this summer.

For more on the tableau tradition, go to other blog entries here and here and here and here. On the emergence of continuity editing, chiefly in the US, try here and here and here. More detailed treatments are in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, On the History of Film Style, and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging.

I’m grateful as ever to Marguerite Engberg, Dan Nissen, Thomas Christensen, and Mikael Brae for their help in my research on Danish silent film.

PS 16 June: Jonathan Rosenbaum has republished on his site his detailed and engrossing 1985 study of Gertrud, which includes discussion of the play from which Dreyer adapted his film. Thanks to Jonathan for making his essay available.

The President (1920).

The Cross

The Puffy Chair (2005).

Mark: [The actors] need to improvise. They need to find the moments, and we don’t let them lean on the script too much. We want them to try to reinvent some of the dialogue and make it fresh.

Jay: We don’t do any blocking. Our whole goal is just to set up a room and basically foster an interaction that we feel is interesting and real.

Mark: And spontaneous.

Jay: And spontaneous.

Jay and Mark Duplass, talking of their new film Cyrus.

DB here:

We don’t do any blocking. Dude, we noticed. In The Puffy Chair, the Duplass brothers typically settle the actors into one spot and pan or cut between them.

Seldom do the characters move around the setting. When they do, it’s usually by means of a walk-and-talk traveling shot that transitions to the next static layout of actors.

We are talking about filmmakers who refuse the challenge of staging.

At the other extreme of budget and commercial clout, consider another film by two brothers. In The Matrix Reloaded, Neo meets the Oracle in the virtual courtyard and sits on a bench with her.

The whole scene, which runs nearly seven minutes, contains 94 remarkably static shots. After Neo settles on the bench beside her, we get simple reverse shots—lots of them, mostly one per line of dialogue. The setups are maniacally repeated. There are thirty-one iterations of the first framing below and eighteen of the second.

The only variation is a slightly tighter framing on each character, creating another brace of single setups during Neo’s acknowledgement of his dream of Trinity’s death. Each of these gets nine iterations.

Sustained two-shots would have let the actors do more with their upper bodies, but in this string of singles, faces and dialogue have to present Neo’s reactions to his new mission to save Zion. Granted, there are seven shots showing both Neo and the Oracle in the same frame, but these are very brief and seem to be there simply to provide beats and add some variety to the load of exposition the scene must carry.

Breaking the scene up so much has interesting rhythmic implications. Paradoxically, our movies are cut very fast but they feel rather slow (and run very long). When we need a cut to see a character’s reaction, a scene plays out more slowly than if the characters were held in the same frame for a significant period. Then we might see Neo’s reactions while the Oracle is speaking, rather than having to wait for them afterward.

But my main point is that the actors are planted in one spot. Like the Duplasses, the Wachowski brothers have felt no need to imagine the characters’ interaction through blocking. Indeed, when shooting a conversation, most of today’s filmmakers seem happiest if the actors stay riveted in place—standing, seated, riding in a car, typing at a computer terminal. Improvised cinema or storyboard cinema: Both camps are refusing the challenge of staging.

In some books and some web entries (most recently, here and here and here and here), I’ve tried to trace the rich tradition of ensemble staging. From almost the start of cinema, filmmakers have explored creative ways of moving actors around the set, aiming at both engaging storytelling and pictorial impact. Since the 1960s, on the whole, this tradition has been waning. Now, I fear, it has nearly disappeared.

I’m not going to reiterate those earlier arguments. Instead I want to talk about one simple staging tactic that directors almost never employ today. I offer it at no cost to young directors. Try it! You might get a taste for a range of cinematic expression that is nowadays neglected.

Cross and double cross

Assume you have two characters in a set. At a crucial moment, you invent some business that lets them exchange places, so that the one on the left winds up on the right, and vice-versa. At a minimum, this gives you visual variety; it keeps the viewer’s attention engaged by refreshing the composition. It can of course also heighten dramatic impact.

Naturally, we expect to find the Cross in the first golden age of cinematic staging, the 1910s. Here’s a case that combines the cross with depth staging, from the Doug Fairbanks picture The Matrimaniac (1916).

Marna and the Court officer have switched places in the frame. Note especially that her movement to the right, clearing our view of the officer at the door, is motivated by her hesitation at following him. Actually such moments probably don’t need much motivation; the flow of the action is so quick that no viewer will ask why she moved to the right, since our attention is on what her action reveals.

One way to motivate the Cross is to have A turn sharply away from B but keep talking. This is a bit of actor’s business that seems far more common in the classical era of moviemaking. Here is an excerpt from a single-shot scene in Budd Boetticher’s The Tall T (1957). Brennan tries to console Mrs. Mrs. Mims, who has realized that her husband betrayed her. He enters the shack and then walks past her, as if considering exactly how to calm her.

This has been the prelude to a more intense confrontation. She comes closer to the camera, and Brennan joins her, forcing her to look at him as he says they must concentrate on staying alive.

In Demy’s Lola (1961) the Cross is motivated by the urge to offer another emphatic view of the protagonist. Roland has been talking to the two mother-figures who run the café he frequents. He’s dragging himself off to work as Jeanne fetches her radio from the bar and goes into the back room. We get two Crosses.

The shot’s climax comes when Roland pauses in the foreground and says: “One day I’ll go away too.” Again, a key character is turned from the other but continues to speak.

No need to cut in to a close-up because Roland’s face is perfectly visible. Just as important, while his face shows a certain reverie, his nervousness is conveyed by the way he waggles the novel in his hand. The actor is given a chance to act, not just with line reading and facial expression but with his slumped posture and his arms—one casual, the other in anxious motion. Taken together, the body and the face present Roland’s confusion.

Crossfire

Don Siegel’s The Big Steal (1949) yields many offhand instances of the Cross, indicating how taken for granted the technique was in studio films. When the slippery Fiske invites Joan in, she comes to the left foreground and he moves to the right side of the frame to shut the door.

Approaching her by stepping into medium shot, he tries to warm her up, but she slaps him. Cut in to underscore her reaction. “What did you expect—kisses?”

In a return to the earlier setup, she turns away and executes another Cross, settling on the sofa.

Simple and concise; some would say banal. But compared to The Puffy Chair and The Matrix Reloaded, it looks brisk. The characters move easily through the frame without camera arabesques, and the medium shot is saved for the slap. The single of Joan adds another spike to the drama. Close-ups no longer rule but are used for momentary emphasis.

So the Cross can be sustained by cutting and camera movement. In The Lady Is Willing, Liza has found a baby and called a pediatrician. Director Mitchell Leisen gives us an over-the-shoulder shot of her and at the close of it she walks around Dr. McBain’s arm, with her feathery hat brushing his face.

If the shot were sustained with a pan, we’d have a Cross, but instead there’s a cut to Liza continuing the movement. McBain turns to watch her.

He starts to follow her diagonally. When she pauses to face him, the Cross is completed.

They leave the room. After a cutaway shot showing Liza’s secretary, the camera pans to follow McBain into depth washing his hands. When he comes through the door past Liza, we get another Cross.

With positions switched, the camera travels with her as she catches up with him in a medium shot. He is opening his medical bag.

This pause enables Leisen to underscore a key line of dialogue. “I detest children of all ages. I detest infants particularly.”

One more Cross and the shot is done. The camera pans again to follow McBain bending over the child, and Liza slips into the shot behind him, remonstrating with him. “A man who dislikes children simply can’t be a baby specialist.”

As so often, the Cross is used to present one character turning from another, or one trying to catch up with another who for dramatic reasons plows ahead. And the Cross favors a moderate depth, not the eye-smiting foregrounds of Welles but something less aggressive. In these ways, the simple device can participate in a broader pattern of fluid craftsmanship. The action can unfold in a clean rhythm, consistent with what Charles Barr calls “gradation of emphasis.” Story points arise smoothly out of the flow of behavior. Actors get a chance to use their whole bodies, to create character through posture or stance, or even the angle of the elbows. Imagine if Dietrich, in the left shot just above, had sauntered to McBain with her hand on her hip as she does in so many other movies; the scene would take on a different tint.

When thinking about staging, we usually invoke Renoir or Ophuls or Jancsó, directors who integrate complex choreography with complicated tracking shots. (They also use the Cross a lot.) My examples try to show that even simple camerawork can enhance the performers’ grace. Nor do they have to execute the calisthenics on display in the office scenes of His Girl Friday. The modest moves we see in The Big Steal and The Lady Is Willing are within the grasp of eager filmmakers and game actors.

Cross purposes

I don’t have a good explanation for why such simple staging tactics have gone out of fashion. It’s too easy to cite laziness or lack of imagination, though they may play a role. I wonder as well if complicated staging is much taught in film schools. More specifically, improvisational methods may actually inhibit creative blocking. An actor who’s winging it may be reluctant to shift around the set, for fear that this creates new problems for framing or lighting or the other performances. Better, the actor may think, to concentrate on line readings, expressions, and other things that she can control while staying rooted to the spot. And maybe our directors don’t want to work their actors too hard, especially when the actors are beginners or nonprofessionals, as we find in indie filmmaking. Yet some masters of supple, intricate staging, such as Hou Hsiao-hsien, employ untrained performers.

Contemporary directors may have a more principled objection to the older staging style: It’s too artificial. In real life, people mostly chat with each other when they’re sitting down, or walking, or riding in a car. Static staging, some might say, captures the passive nature of everyday interactions.

But dramatic narrative typically doesn’t consist of ordinary life. A film offers heightened, focused, pointed encounters, shot through with meaning and feeling. The actors and the filmmaker have a chance to sharpen the viewer’s perception of the situation and pass along the moment-by-moment play of thought, emotion, and action. There are both loud and quiet ways of doing this. Antonioni’s famously “dedramatized” scenes are staged as dynamically as the more florid moments of Visconti or Fellini. Emotionally subdued action can be shaped just as precisely as passionate outbursts, and it can carry its own impact.

I should make it clear that I’m not asking anybody to embrace a single style. Sometimes stand-and-deliver and intensified continuity editing work very well. Directors will always seek specific solutions to the problems of a scene. But I don’t see much variety in the solutions many people now pursue. I don’t see evidence that most young filmmakers around the world are aware that traditions furnish lots of alternatives.

In earlier periods, some directors were as editing-oriented as today’s mainstream ones, while other directors adopted more staging-driven approaches. But either sort had a broader palette than what we see today. Any accomplished director could stage a conversation in a variety of ways. Just to take Demy, some scenes in Lola are handled in full shots like the one highlighting Roland in the café. Other scenes are broken up into tight singles, and still others are treated in two-shots.

All the classical films I’ve mentioned are pluralistic in their technical choices. Today, though, we see more uniformity, or rather conformity.

Cinephile conversation on the internet is currently rippling around a controversy about “slow cinema.” Whatever that rough category covers, it surely includes those festival films that put the camera in one spot per scene and simply observe. I’d argue that many of these minimalist movies are also AWOL when it comes to staging. After watching a long-take, flatly shot film with me, a Hong Kong filmmaker friend remarked, “This sort of thing is just too easy.” One difference between a solid “slow film” and an empty one, I suspect, lies in the extent to which the filmmakers explore the resources of staging. How do we know? We have to analyze the films. (More on this matter here.) Absent that analysis, critics’ appeals to realism or meditative restfulness or “time flowing through the shot” risk becoming alibis for inert moviemaking.

Many young directors want to be innovative. They want to shake things up. This is a good impulse. The way things are going, the ambitious way forward is obvious: Go backward. Avoid stand-and-deliver. Avoid walk-and-talk. Get your actors on their feet and move them around the setting. Invent bits of business that let them crisscross the frame, laterally and in depth. Dynamize all areas of the shot. In the process you may discover new dimensions of creativity.

The Cross is only one tactic, but I think it’s useful as a way to sensitize ourselves to staging. The best way to understand staging is to watch, really watch, a lot of classic cinema from Hollywood and elsewhere. When you’re ready for the hard stuff, Mizoguchi is waiting.

I expect disagreements with my criticisms of contemporary film technique, so I hope skeptics will consider my more extensive arguments in On the History of Film Style, Figures Traced in Light, and The Way Hollywood Tells It.

I haven’t found references to what I call the Cross in manuals of direction. The closest technique, and the one that called my attention to the possibilities of the technique, is what Mike Crisp in his valuable book The Practical Director (first ed., 1993) calls the “rise and cross.” This refers to actors getting up from sit-down conversations in one spot and moving to another sit-down area, while switching position in the frame. I’ve expanded the idea to cover a broader variety of situations.

As far as I can tell, my term doesn’t have much in common with the stage direction “Cross,” which you’ll find in play scripts. Janie Jones provides definitions here. While staging in film is in many respects different from that in theatre, I think that moviemakers can find intriguing practical ideas in Terry John Converse, Directing for the Stage.

Alicia Van Couvering’s interview with the Duplass brothers, “Don’t you want me?”, is published in Filmmaker 18, 3 (Spring 2010; not yet available online); my quotation is from p. 43. In his essay Slow Cinema Backlash, Vadim Rizov argues that lesser attempts at “slow cinema” have led to a somewhat predictable style.

Raining in the Mountain (King Hu, 1979).

Beyond praise 3: Yet more DVD supplements that really tell you something

Darby O’Gill and the Little People (1959)

Kristin here–

Every now and then I discuss a few DVD supplements that teachers might find useful for their classes, though they might be of interest to others as well. Previous installments can be read here and here.

Darby O’Gill and the Little People (Walt Disney Video)

Yes, you read that right. I can’t claim credit for having discovered this disc’s excellent supplement, “Little People, Big Effects.” Shortly after the second “Beyond praise” entry, Dan Reynolds, who teaches at the University of California Santa Barbara, wrote to recommend it.

Darby O’Gill was one of the few Disney live-action films I missed when I was growing up in the 1950s. I acquired the disc and started by watching the feature. I must say that this is one weird movie.

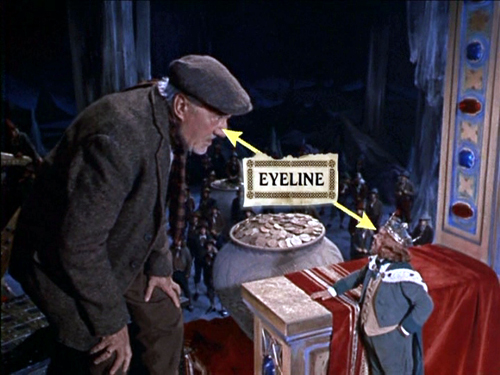

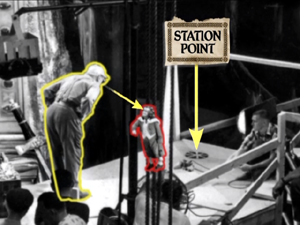

The “little people” of the title are leprechauns, and the special effects used to make them look small are mostly achieved through forced- perspective techniques. In less than eleven minutes, this supplement demonstrates the use of glass paintings, mattes, false perspective, and even a revived Schüfftan process, most famously used for Metropolis, where scale is manipulated by shooting into an angled, partially transparent mirror. Careful calculations allow for over-sized sets in the background to be lined up precisely with normal-scale ones in the foreground, so that the foreground person looks much larger then the background one. Since the two characters, here Darby and King Brian, are supposed to be conversing face-to-face, a manipulation of eyelines, a term we use a lot in Film Art, is necessary. (Despite what my spell-check keeps trying to tell me, “eyeline” is one word in the movie business, as demonstrated above.) In explaining how the actors knew where to look in the shot illustrated at the top, the film shows that “station points” were placed on the floor so that the characters’ eyelines would seem to match up (below). These days actors alone against blue or green screens often have to look at tennis balls to make the direction of their gaze match correctly.)

Clearly some behind-the-scenes footage was made during the production of Darby O’Gill, and this is incorporated into a documentary that includes interviews with master effects expert Peter Ellenshaw, who died in 2007. Ellenshaw worked as a matte painter on half the British classics of the 1930s and 1940s, including Black Narcissus (which has perhaps the greatest matte paintings ever). He then moved to Hollywood in 1950 and began a string of films with Disney that won him an Oscar for Mary Poppins. It’s good to have even these short clips of him demonstrating and discussing his work.

“Little People, Big Effects” should give students (and just about anyone else) a better grasp of perspective and its importance in the representation of depth on a flat screen. I would definitely show it as part of a study of cinematography. If a fifty-year-old film seems a bit out of date, point out to students that, as the narrator mentions, exactly the same techniques were used in many scenes of The Lord of the Rings to make the hobbits and dwarves look small. Similar demonstrations are provided in the supplements to the extended DVD version of The Fellowship of the Ring (Disc 1, “Visual Effects: Scale”).

Elijah Wood sits further from the camera than Ian McKellen in order to make him appear as small as a hobbit

Zodiac (“2-Disc Director’s Cut,” Paramount)

At the end of my first “Beyond praise” entry, I complained about the lack of supplements on the initial DVD release of Zodiac. Then, after the two-disc set with the supplements appeared in early 2008, I forgot to include it in the second entry. Better late than never, so I’m tackling it here. (The supplements are apparently the same for the Blu-ray set.)

As the “DVD Talk” review says. “The self-congratulatory praise is kept to a minimum.”

The main supplement is a 53-minute film called “Deciphering Zodiac.” It’s a good, objective, chronological summary of the film’s production. A lot of talking heads are included, such as the producer, scriptwriter, set decorator. That’s usually a good sign, since it shows that care was taken with the making-of and that enough of the crew members are participating that the account will probably be rounded. There’s a 15-minute making-of specifically on “The Visual Effects of Zodiac.”

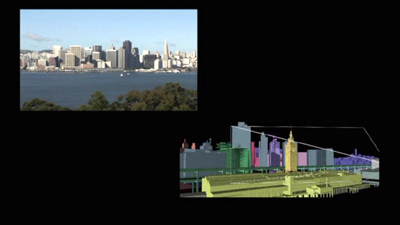

Zodiac was primarily shot on professional-level digital cameras, apart from the slow-motion shots, which still need to be done on 35mm due to limitations of the digital technology. Hence there’s a lot of information here on digital techniques. Most of these techniques are used in ways that aren’t necessarily obvious to the viewer. If you want to show students some material on digital effects, this might be a good choice, since it avoids the flashy, obvious effects that so many fantasy and sci-fi DVD supplements concentrate on.

“Deciphering Zodiac” has shots showing the digital camera attached to an elaborate rig around a car, which was used to follow moving cars, including the famous opening tracking shot along a suburban street. The video-assist monitor is often visible in the shots.

One change that digital filming has made in production has been the frequent use of “digital dailies” rather than dailies on film. (Dailies are the unedited takes just as they come from the camera(s); directors and other key creative people typically watch them at the end of each day.) Several scenes of the “Deciphering” documentary show raw shots and are labeled as digital dailies, something which doesn’t seem to be a common feature of supplements. It’s pretty obvious that the shot of Jake Gyllenhaal below would need to be manipulated in post-production. There’s also informative coverage of the methods used to match location and studio-shot footage, particularly for the scene where the killer shoots a taxi driver.

The visual effects documentary has good explanations of the early shot of a rapid move across the bay toward San Francisco as it looked in the period when the film’s action begins, a shot that was done entirely digitally.

Now that so many best-lists for the decade have included Zodiac, it seems to be an official modern classic. Perhaps a somewhat more dignified way of teaching special effects than using a Transformers movie.

The Dark Knight (Two-Disc Special Edition, Warner Home Video)

The supplements for The Dark Knight make a nice contrast with those for Zodiac. Here the makers of a spectacular action movie avoided digital special effects to a surprising extent. Instead they used practical effects, that is, effects accomplished via physical means while shooting rather than those done in post-production via laboratory or digital manipulation. Digital technology was used, of course, but often for rather modest tasks in planning and in erasure of unwanted elements. It’s also interesting as the first 35mm fiction feature to be shot partially on Imax cameras.

The main supplement is “Gotham Uncovered.” It begins by showing how the Imax camera was initially tested on a single action scene shot on location in Chicago. The results led to additional Imax scenes being added to the film. The advantages of Imax—primarily a huge gain in visual quality due to the larger size of the individual frames—are shown to be balanced against the camera’s limitations. The camera is much larger, making handheld shots difficult. It holds only three minutes of film and has a shallower depth of field. While interesting, this first section is surprisingly lacking in actual footage of the filming, often depending on still photos. We tend to assume that in this day and age, the making-of is taken into account from early on in a production. It’s surprising how often that turns out not to be the case.

A five-minute segment, “The Sound of Anarchy,” shows Hans Zimmer sitting at a computer and talking about the modernist, dissonant music for the Joker character. It’s mildly informative.

“The Chase” is perhaps the most useful section of the making-of. The decision was made to shoot the scene on Lower Wacker in Chicago. Here digital effects were kept to a minimum, with multiple cameras mounted on vehicles like the motorcycle below. These were special smaller Imax cameras. Only four such cameras existed at the time, though an accident reduced that to three!

One big moment in the chase has the Batmobile crashing into a garbage truck. Again, rather than resorting to digital effects, the crew built miniatures of the two vehicles and the set. The decision was also made to shoot a crash of an 18-wheeler on LaSalle Street using a real truck on location, and the scenes showing the practice sessions for this reveal the kind of planning that goes into the big action scenes that are so common in films these days.

A multi-vehicle crash scene was done with several cameras, which is common practice for unrepeatable actions. (Even on a big-budget film like this, no one would want to crash more than one Lamborghini.) The cameras often show up in each other’s shots, and the supplement shows the resulting footage and how CGI is later used to erase them—again, a very common use of digital tools. Here a camera on a crane is visible at the center left in the original footage of the crash:

In one scene, the Joker walks out of a hospital, which explodes behind him. A prime candidate for digital effects, one would think. Instead, the filmmakers opted to have a demolition company destroy a real building. CGI was used to plan the scene:

A shorter supplement, “The Evolution of the Knight,” deals mostly with the design process for Batman’s suit and the Batpod. Again the emphasis is on bringing reality into the filming. It’s pointed out that while much of Batman Returns was shot on sound stages, the team decided to try and shoot the sequel in the city streets as much as possible.

Beware of these

I have to admit, one reason that this series appears so rarely is that for every DVD with useful supplements that I find, there are two or three uninformative ones that I have to sit through–or at least sample. In addition to recommendations, let me warn you away from some of the ones I switched off.

I had expected the Slumdog Millionaire DVD extras to be interesting, given the mixture of digital and 35mm shooting, the location work, and so on. But obviously the filmmakers had no idea that the film would be a success, so they seem to have done little behind-the-scenes shooting as they made it. The result is a not terribly informative, bare-bones 18-minute making-of.

Supplements as praise-fests have not gone away. Musicals seem especially to bring them out. “Get Aboard! The Band Wagon” provides 36 minutes of mutual admiration. In “From Stage to Screen: The History of Chicago,” Chita Rivera unintentionally achieves a parody of the gushing movie star who lauds everyone she worked with.

David and I just watched Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs. I had liked it when I saw it in first run, and predictably, David enjoyed it, too. It’s a clever, well-scripted, well-animated film. We hoped to learn something from its supplements, but the making-of seems to be aimed at children, and young ones at that. The co-directors and some of the other filmmakers look distinctly embarrassed to be participating, partly because a lame comparison of making a film to mashing food together forms a running motif. A pity, since the movie deserves better. As reviewers keep pointing out, the best animated films these days are made for adults as much as for children.