Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

A hundred years, plus a few thousand more, in a day

Charlie Keil, Yuri Tsivian, Henry Jenkins, Kristin Thompson, and Janet Staiger. Photo by Joel Ninmann.

Last Saturday we held the symposium “Movies, Media, and Methods” in honor of Kristin’s arrival at age sixty. Four distinguished scholars, all professors from major universities, presented top-flight talks. As a bonus, Kristin gave The Film People a glimpse into her Egyptological work. I report on this very full day in the hope of giving a sense of how stimulating we found it.

Thanhouser was an American film company that flourished between 1909 and 1917. It has been overshadowed by Biograph because that firm put out more films and, not incidentally, employed D. W. Griffith. But Ned Thanhouser has been diligently gathering his family company’s output from archives around the world and releasing it in informative DVD editions. The most famous Thanhouser production is probably Cry of the Children (1912), a powerful attack on child labor. You could also try the thriller The Woman in White (1917), adapted from Wilkie Collins’ masterful novel. A study in sadism, and more subtle than The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

Charlie Keil, an expert in 1910s US film from the University of Toronto, examined Thanhouser’s films with two questions in mind. Did the studio have a “distinctive personality” in its products? And does its output reflect the development of film style across the crucial transitional years of the early 1910s? Borrowing a method that Kristin had applied to Vitagraph films in an essay, Charlie took one film from 1911, one from 1912, and one from 1913. Charlie wasn’t ready to conclude that these specimens displayed a unique studio style, but it was clear that across just three years, big changes in storytelling were taking place.

The plot of Get Rich Quick (1911) involves a man who joins a business that is scamming innocent investors. The film uses only five locales and plays scenes in long takes. The Little Girl Next Door (1912) has a more complex plot, with two distinct lines of action that converge on a child’s drowning. It uses many more locales and an ellipsis of a year to trace the changes in a family’s fortunes. It also incorporates cut-in close views and point-of-view editing. The Elusive Diamond (1913) is less psychology-driven than The Little Girl Next Door, but its intrigue relies almost completely on dialogue titles and it includes many close-ups and variation of camera setups.

Three films and three years: A vivid cross-section of the rapid development of what soon became classical visual storytelling. Moving from 18 shots to 53 shots to 74 shots, the films became less dependent on staging and more dependent on editing. At the same time, Charlie didn’t fail to notice how the long takes in Get Rich Quick allow some felicities of performance, particularly the way that the wife’s handling of her apron charts her psychological states. She brushes it aside to show how poor they are, then she uses it as a giant hankie.

Like all good papers, Charlie’s left a lot to be discussed. People asked about how much pre-planning was done at Thanhouser, about the directors and screenwriters on staff, about the division of labor. We were left with a sense that here was another mostly unknown region that would reward further study.

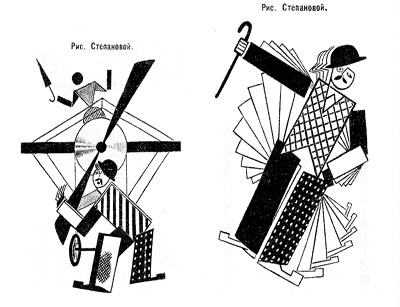

Fernand Léger, Cubist Charlot (1923).

Yuri Tsivian of the University of Chicago carried us into the twenties with an in-depth examination of early Russian reactions to Charlie Chaplin. The paper held many surprises. Chaplin was popular in many countries from 1915 onward, and very soon after he was celebrated by European intellectuals. But Russia lagged behind; there’s no concrete evidence that any Chaplin films were shown there until 1922. Yet the Soviet avant-garde embraced him. How and why?

Instead of looking for a dual relationship—Chaplin directly influencing Russian artists—Yuri postulated a “triangular” relationship, in which Chaplin’s image was mediated through other European sources. For instance, Léger’s numerous images of a fragmented Chaplin led Futurists and Constructivists to declare Charlie “one of us.” They loved the idea of man as a machine executing precisely articulated movement, and what they heard of Chaplin’s pantomime and gags led them to praise him. Chaplin, said Lev Kuleshov, is “our first teacher” because he knows bio-mechanical premises better than anyone. According to the photographer and graphic designer Rodchenko Chaplin instructs viewers in how to walk or put on a hat in the most perfect manner.

So strong was this “virtual” image that artists could read Chaplin into the slapstick comedians they did see. Yuri showed that Varvara Stepanova’s striking rendition of Chaplin as an airplane propeller derived from a film he wasn’t in!

Perhaps she didn’t care: Nikolai Foregger suggested that Chaplin himself was unimportant, that the crucial fact was that he created a whole school of comedians within what Yuri called “a collaborative research community”—that is, Hollywood!

Yuri’s paper, in homage to the Russian Formalists, invoked the “law of fortuity” in art. This refers to the possibility that artistic borrowings, blendings, and crossovers are not determined by any broader social processes, as the Marxists were arguing, but are merely contingent. “Life interferes with art from below.” Accidents and unforeseen intersections, such as the Chaplin craze meeting the Constructivist movement, allow artists to seize on whatever is around them for new material. Yuri’s reference was to Kristin’s revival of Formalist methods in her “neoformalist” studies of Eisenstein, Tati, and other filmmakers.

Janet Staiger of the University of Texas at Austin collaborated with us on The Classical Hollywood Cinema, and she has for several years been the leading scholar of reception studies in film and television. In looking at the Indiana Jones series, her paper nodded to Kristin’s work on the Lord of the Rings franchise and her study of fans’ responses to the films.

“Nuking the fridge,” Janet explained, has become fan jargon for an outrageous plot twist. The phrase comes from a notorious moment in Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008), in which Professor Jones escapes an atomic blast by diving into a lead-lined refrigerator. The moment becomes a crux for clashing fan judgments: This is totally unrealistic vs. Realism doesn’t matter. Janet went on to show how these and other fan responses, entwined in IMDB commentary threads, utilized several different interpretive frames.

One was authorship. Like academics and journalists, fan are auteurists. They assign the director responsibility for major aspects of the film. But this doesn’t mean that they agree in how to use this frame. In the case of Crystal Skull, a certain Kid Mogul asked if Spielberg’s willingness to reinvigorate the franchise was purely mercenary: “Is it just about the money?” Others took a more career-survey approach, noting that after prestige pictures like Schindler’s List Spielberg recalibrated his popcorn movies, particularly by handling violence more gingerly.

Another frame was story-based “lit talk.” Fans disparaging the film found it clumsily plotted and lacking in character development. Several were quite sensitive to narrative coherence, one-off gags (such as nuking the fridge), and pacing. Those defending the film appealed to the emotional burst of the final chase scenes.

Janet’s third frame of reference was what she called “formula dissonance.” She sought to capture what seeing the film would be like for those who knew Indy’s story only through the TV series or video versions of the earlier installments in the franchise. She suggested that the formula was by 2008 quite abstracted and idealized for many fans. Their sense of the franchise was thus tested by the extraterrestrial twist that resolved the Crystal Skull plot. Does it reframe the whole series in a cosmic context, or is it a violation of the premises of the Indy universe?

Janet’s survey of these types of responses made me notice that the assumptions of academic film studies and of journalistic criticism overlap with fan conversation. Fans who liked the film tried to make everything fit by appeal to organic unity, technical proficiency, emotional intensity, and other familiar criteria. It made me suspect yet another reason why “amateur” and “professional” film criticism seem to be merging: Perhaps their conceptual frames of reference aren’t so far apart. But their tastes and their degrees of commitment surely are.

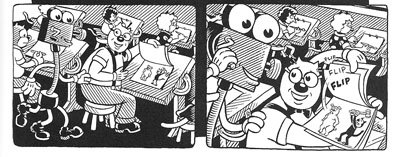

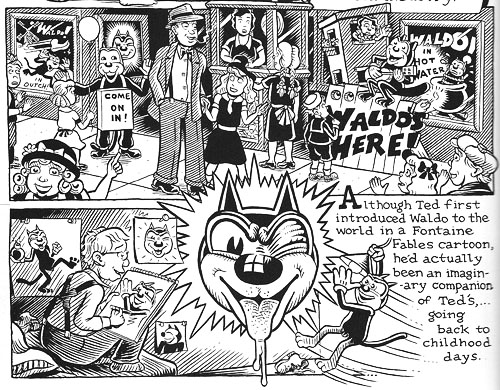

You might have expected Henry Jenkins of the Annenberg School at the University of Southern California to talk about fans too. After all, he practically invented the modern study of media fandom with his book Textual Poachers, and his work influenced Kristin’s study of fan promotion of The Lord of the Rings. Instead he turned to a survey of an artist’s oeuvre. He showed how Kim Deitch’s vast output of stories appropriate imagery from nineteenth and twentieth century mass media and present highly personal versions of the history of popular culture.

In a way, though, Henry’s talk involved fandom because Deitch is himself a prototypical fanman. He’s an obsessive collector, likely to turn his search for a rare toy or drawing into a Byzantine odyssey on the page. Fascinated by Hollywood scandal, he has constructed a phantasmagoric history of mass media through fictional characters (e.g., fake movie stars) who confront real people (e.g., Fatty Arbuckle). He’s particularly concerned about what he takes to be the warping of animated film by the influences of the mass market, epitomized by the Disney empire. The emblematic moment in Boulevard of Broken Dreams comes when Deitch’s Winsor McKay stand-in addresses torpid animators at a tribute dinner and denounces them for selling out.

Deitch’s most famous character is Waldo the cat, and Henry traced the powerful connotations of this emblematic figure. Waldo recalls Felix, the most heavily merchandised comics figure before Mickey, as well as the black cat as a figure of deception, witchcraft, and even African-American minstrelsy. Through Waldo, Deitch could hop across the history of film and comics, from McKay to Mighty Mouse and 1940s abstract films. In Alias the Cat!, Deitch finds in the 1910s everything that we associate with media today: serial narrative, stories shifting across different media platforms, an uncertain line between publicity and self-expression, and a mixing of news and sensational fiction.

Henry situated Deitch in a broader trend of comic artists trying to find a new history of their medium, one that dislodges superheroes from a central role. Deitch’s themes of old-fashioned craftsmanship, lovably antiquated technology, adult dread and degeneracy lurking behind children’s stories, and the commodity demands of comic art link him to contemporaries like Chris Ware and Art Spigelman.

Henry’s talk spurred a lot of discussion, including the question of whether we can treat an artist as offering a history that is comparable to academic research. Can Deitch’s hallucinatory vision of American media be a plausible basis for understanding what really happened? On the whole we don’t expect an artist to offer rigorous arguments. An artwork appropriates history for its own end. (Not all the Greek philosophers actually gathered together in the way Raphael depicts them in the School of Athens painting.) How cogent you find Deitch’s critique probably also depends on whether you share his disdain for Disney. His floppy-limbed denizens fuse headcomix grotesquerie with the 1930s animation that most prestige studios abandoned. As in Sally Cruikshank’s sprightly cartoon Quasi at the Quackadero, Deitch’s rubbery frames revive a style in which everything seems to throb and shimmy.

Kristin’s talk, “How I Spend My Winter Vacations: The Amarna Statuary Project and Techniques of Visual Analysis,” had two parts. In the second part, she reviewed her recent work in assembling statues out of tiny bits that had been dumped by archaeologists decades ago. You can read some of this story here. The side of her work most intriguing to students of film, I think, involves her attraction to Egyptian art in the first place.

Egyptian art is often thought of as unrealistic, but during his reign in the fourteenth century BCE the pharaoh Akhenaten introduced a peculiar sort of stylization into it. When he instituted a monotheistic religion centered on the sun god Ra (embodied in the Aten), he also demanded a new pictorial style. Thus the Aten is depicted as a disc shedding rays, a symbol of life and dominion. In addition, the royal family displays biggish hips and thighs, which fit the fecundity theme. More strikingly to our eye, Akhenaten’s family were represented as somewhat distorted, with long and narrow faces, hands, and feet. The ruler’s crown is elongated as well. Several aspects of the new style are present in Kristin’s favorite scene, a beautiful relief carving known as the Berlin family stela.

You can see the Aten’s rays ending in little hands holding ankh signs to the royal couple’s noses. But just as important is the human dimension of the scene, and two sorts of action displayed there: swiveled shoulders and pointing hands.

Unlike the flat, frontal portrayal we associate with Egyptian art, the family members are caught in twisting postures that bring one shoulder forward. Kristin explained:

Akhenaten is lifting his daughter, his foreground arm moving backward to hold her legs, the other moving forward to support her body as he kisses her. She reaches with her rear arm to chuck him affectionately under the chin, while her other arm moves backward in a pointing gesture. On the opposite site, Nefertiti’s foreground arm is held bent and backward to steady the youngest daughter of the three present, who is standing on her thigh and reaching up rather precariously to grab a golden decoration hanging from her mother’s crown. Nefertiti’s rear hand goes forward to steady the second daughter, who is also pointing, this time with her rear arm as she twists to look at her mother. These kinds of gestures can be found again and again in such scenes.

The twisting movement wasn’t unknown among images of workers and private individuals; Amarna artists, presumably encouraged by Akhenaten, applied the device to portraying the royal family.

Just as significant are the pointing gestures we find in the stela. Some scholars have interpreted them as protective gestures, which are found in other images. But Kristin points out:

In those cases, the protecting figures hold their arms straight, they stare in the direction of the thing to be protected (as one presumably would in reciting a spell), and there is something dangerous present. None of this applies in the scene in the stela.

In those cases, the protecting figures hold their arms straight, they stare in the direction of the thing to be protected (as one presumably would in reciting a spell), and there is something dangerous present. None of this applies in the scene in the stela.

After pondering this scene quite a lot, it occurred to me that it looked like a really early film, a short scene, perhaps 30 seconds long, that we were to interpret as a tiny narrative. The pointing gestures seemed comparable to pantomime, where one has to interpret movements in the absence of intertitles.

Given that so much Amarna art is about displaying the royal couple as having created life by giving birth to their daughters and as sustaining that life, it seems to me that this stela is full of indications of nurturing. The columns and roof indicate that the parents have their kids in a little shelter to keep them out of the hot sun. The rows of pots behind Akhenaten’s stool are no doubt filled with cool drinks for them. Nefertiti carefully holds onto the two children on her lap while Akhenaten kisses the eldest. My interpretation is that the eldest is saying something like, why don’t you kiss sister, too?” and the one opposite is pointing out the kiss to her mother and saying something like, “Look, daddy’s kissing sister; I want a kiss too.”

This may not sound like the sort of thing kids would say, but the circulation of affectionate gestures among the family members in these casual scenes is nearly universal. The chucking under the chin gesture used by Meretaten here shows up again and again, as do embraces and kisses.

Despite all the stylization, then, Kristin concludes that the stela depicts a scene of intimate affection, complete with a child toying with a mother’s ornament. This homely realism chimes with other realistic tendencies in Amarna art, such as the differentiation of right and left feet and the presentation of plants and animals in non-stereotyped ways. In sum, Kristin’s ability to look closely at film style helped her make discoveries about visual narrative in a completely different domain.

So our Saturday talks included cinema-related material from 1911 to about 2010, and with Kristin’s lecture we flashed back about 3300 years. Every talk was crisp and lucid. We were spared the juggling of empty abstractions, the free-associative rambling, and the self-congratulatory cleverness that plague the humanities. We got knowledge and opinion presented with enthusiasm, modesty, and good humor.

Kristin and I are grateful to our presenters, as well to all the friends old and new who showed up: Leslie Midkiff Debauche from Stevens Point, Carl Plantinga from Michigan, Peter Rist from Montreal, Brenda Benthien from Cleveland, Virginia Wright Wexman from Chicago, Vicente José Benet from Spain (via Chicago) and many others. In all, a day to remember.

For more information on Kristin’s research see my earlier entry. For other cinematic implications of the Berlin stela of Akhenaten’s family , see Kristin’s blog entry here. Her article, “Frontal Shoulders in Amarna Royal Reliefs: Solutions to an Aesthetic Problem,” is available in The Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities 27 (1997, published 2000).

All of our speakers are represented on the Web: Henry here, Charlie here, Janet here, and Yuri here (and of course on Cinemetrics). For more on Janet’s study of online critics and the frames they inherit, see her essay, “The Revenge of the Film Education Movement.”

Kim Deitch, Boulevard of Broken Dreams.

Festival as repertory

DB here:

This picture points backward and forward. It looks back to the days when movies were shown on a big screen to hundreds of people in real time. No pausing or fast forwarding; you take what you get. Some viewers are settled in pretty close to the screen, and a few dare to sit in the front row. (Save me the center seat, fortunately still vacant.) The critic sits slumped far back, implying coolly distant appraisal. The pen is poised to note down moments of power, beauty, or stupidity.

But the big auditorium is nearly empty, and this makes the drawing foreshadow the approaching end of moviegoing. The warning signs are emerging: Visit any movie, even an Imax spectacular, in the off-hours (Monday through Wednesday, especially matinees) and you’re likely to find the house as empty as it is here. As for the critic, ready to jot down notes for a review: An anachronism these days, as many will tell you.

But wait. Isn’t the theatrical business booming? We’re told that 2009 was a banner year, and 2010 will be even better. True, worldwide admissions for 2009 totaled $29.9 billion, a new high. But the increase, according to the MPAA, is mostly due to 3D. In the US, the format accounted for 11 % of the country’s $10.6 billion box-office income, a sum about equal to the gain over last year’s take. Moreover, the number of domestic tickets sold increased only a little from recent years, to 1.4 billion. Overall, the years 2005-2009 have fallen off from the high points of 2002-2004, when attendance was 1.5 billion or more.

Nor is the international film industry expanding its audience. For the last five years or so, worldwide attendance has been remarkably flat, with only the Asia-Pacific region seeing signs of growth. Overall, it seems, 3D serves to let Hollywood hang on to its audience, and charge more.

The spurt in theatrical income helps offset the decline of packaged media. The DVD sell-through boom lasted from 1998 to about 2008, when subscription rental companies (Netflix, Lovefilm) and kiosks (Redbox et al) pushed down retail sales. The slump was accelerated by a glut of DVD releases, big-box stores offering discs at rock-bottom prices, the rise of downloading and video on demand, and, not least, a massive recession that made consumers cost-conscious. Today, many industry observers think that young people are more inclined to graze in the luxuriance of YouTube than visit the multiplex. At best, the Millennials might watch a current hit streaming on their cellphones or laptops or TV monitor. An admittedly small-scale inquiry in the recent Screen Digest (April, p. 100; here, but proprietary) suggests that most young entertainment fans don’t feel a need to rent a disc, let alone buy one. Moreover, all those sampled saw far more movies on monitors, often through shady downloads, than on theatre screens.

It’s not hard to imagine a near future when a movie opens simultaneously on the global market to satisfy its most devoted public before moving in a very few weeks to DVD, VOD, iTunes, and other digital platforms. It then snuggles into hundreds of thousands of hard drives around the world, ready to be awakened when somebody feels the urge to watch. These seem to be the two poles we’re moving toward: the brief big-screen shotgun blast, and the limbo of everlasting virtual access. You can argue that the very success of home video, cable, and the internet have cheapened our sense of a movie’s identity.

Which is one reason why film festivals are very, very important.

Apocalypse then and now

I’ve spent most of the last several weeks at festivals. The Hong Kong International Film Festival is a 2 1/2 week showcase of global cinema, attached to a major regional market assembly and spiced with local attractions and international retrospectives. The Wisconsin Film Festival is a 4 1/2 day local event highlighting US independent cinema but with a leavening of recent arthouse titles and restored classics. Ebertfest, formerly Roger Ebert’s Festival of Overlooked Films, is a topical festival held in a single venue, featuring a wide array of guests, and reflecting its founder’s eclectic tastes.

Each offers unique pleasures, and each reaffirms the value of the theatrical motion-picture experience. I’ve already written a bit about Hong Kong here and here and here, and I hope to write more about the Wisconsin event soon. For now I’ll concentrate on a few high points of Ebertfest, which took Roger’s cartoon above as its emblem. Kristin and I have been guests for many years (our posts are in the Festivals: Ebertfest category on the right), but this time she was in Egypt scouring the sands for pieces of statues. So I’ve had to blog solo.

Fortunately, we now have a vast archive of what happened in Urbana. With the generosity typical of Roger’s event, all the Q & A sessions and panel discussions were recorded and streamed. They’re available here. And for an appreciative account of what it all means, see Jim Emerson’s piece on Roger’s site.

Start with the obvious. Apocalypse Now Redux was shown in a Technicolor restoration in the Virginia Theatre, a picture palace built in 1926. The image loomed, the sound engulfed you. Several people, most of them young, told me that they felt privileged to have seen the film, for once in their lives, as it must be seen. As soon as you get a home theatre that matches this presentation in sheer primal impact, call me. I’m coming over.

Editor and sound designer Walter Murch, one of my heroes, was prevented from coming by the European volcano ash. So I tried in my introduction to pay homage to what is surely one of the most complex soundtracks of any film of the period—a mixture of synthesizer, rock and roll, and layer upon layer of subtly enhanced noises. During the screening I was able to appreciate some of the daring soundfields Murch created. When Willard gets up to look out the blinds of his Saigon hotel, the sound in the left and right and surround channels narrows abruptly to the central speaker, bringing him back to mundane R & R reality. Later, most ordinary dialogue comes from the central speaker, but when Willard voices his commentary, we hear him from all three front speakers; the soft tone creates an intimacy, while the auditory spread gives it weight and authority.

A panel of commentators including Ali Arikan, Michael Phillips, and Janet Pierson did a fine job of probing various aspects of the film. Ali considers it Coppola’s crowning achievement and one of the great American films. Michael, by contrast, thought that what he aptly called the “terror and grandeur” of its opening half gives way to off-kilter and pretentious scenes in Kurtz’s compound. Janet, who had seen the film on the big screen more often than any of us, found it an enduringly impressive accomplishment in both sound and image. With the audience we had a lively exchange about the role of women in the film and the inclusion of the notorious French plantation sequence. Matt Zoller Seitz made a shrewd point about how the film shows Americans bringing along homegrown entertainments (Playmate performances, rock music, surfing) to redefine the war in familiar terms.

Despite all the shock and awe, I like the film only moderately. It’s a stunning logistical accomplishment, and it has some brilliant moments; but I think it has problems almost as soon as Willard moves upriver. I might be the only person who finds the Kilgore scenes overdrawn, almost Dr. Strangeloveish. When Kurtz bends down to give water to the wounded Vietnamese, he’s interrupted by news of surfing, and he yanks his canteen away as the VC scrabbles for it.

Heavy, heavy—as is the repeated motif of Americans strafing civilians and then tending to their wounds. Willard spells it out: “We cut them in half and then give them a Band-Aid.” Yet I still admire the utterly disorienting opening, which mixes thrumming choppers with ceiling fans and justifies what Michael Herr called it: the rock-and-roll war. Later we’ll see battles wreathed in psychedelic haze, and a hallucinatory assault on the bridge, with Willard stumbling through the dark and watching battle-fried infantrymen hurl ordnance into a void. It’s like a light show at the climax of a rock concert.

One of my favorite comments about the movie came during Dick Cavett’s television show circa 1980. Dick asked Jean-Luc Godard what he thought of Apocalypse Now. This was a period in which most of the press coverage obsessed about the film’s soaring budget. Godard remarked that Coppola had not spent enough. Cavett asked for an explanation. Godard: “Well, he spent only fifty million dollars and the war cost fifty billion. You cannot film this war on such a small budget.” That’s the way I remember it, anyhow.

From Rwanda to LA

Quick notes on two other E’fest titles. (I’ve already discussed Departures here.)

“I wanted to make a film for a Rwandan audience.” Not what you might expect to hear from an American director of Korean descent. Accordingly, Lee Isaac Chung gave Munyurangabo a leisurely pace and structure. The plot centers on two young men, Sangwa and Munyurangabo (aka Ngabo), taking what seems to be an enigmatic journey. One is Hutu, the other Tutsi. Longish takes and fairly distant framings follow them hitchhiking and stopping over at Sangwa’s home. Gradually, hints such as Ngabo’s carefully wrapped machete suggest that they are heading toward a confrontation. When the revelation comes, our attachment shifts from Sangwa and his family conflicts to Ngabo’s mission of vengeance. Chung explained that the soundtrack develops accordingly, moving from objectivity to subjectivity as we start to hear what his two protagonists hear.

The production background, explained by Chung and his colleagues Sam Anderson (co-writer and producer) and Jenny Lund (co-producer and sound recordist), was fascinating. The script consisted largely of a scene outline, and the dialogue was developed with the actors. The Americans worked with translators in guiding the performances. In some cases they drew on their own experiences. Perhaps partly because of its respect for everyday life, the film has been shown on local television and in the Parliament. It has become a Rwandan film.

My colleague J. J. Murphy has written an acute analysis of Munyurangabo. He rightly praises the sudden entrance of a bardic young man who recites a six-minute poem celebrating liberation and reconciliation. The performance wasn’t planned, Chung said, but it has become a high point of the film. J. J. also links to other enlightening interviews given by Chung, Anderson, and Lund.

If Munyurangabo’s loose structure evokes the Dardennes brothers, Michael Tolkin’s The New Age has the coiled-serpent dramaturgy of a classic psychodrama-comedy. It’s 1994, and a prosperous LA couple is suddenly without income. Facing bankruptcy, Katherine and Peter auction off their paintings, try to borrow from Peter’s father, and eventually open a boutique catering to the tastes of their friends. At the same time they slide into casual affairs and ceremonies of New Age spirituality. Ebert’s review captures the movie’s range of reference:

Tolkin gives us one richly detailed set piece after another, involving luncheons, openings, massages, telephone tag, psychic consultations, sex, heartfelt conversation, and pagan rituals led by a bald-headed woman who sees what others cannot see. Meanwhile, the material universe remains the one thing Peter and Katherine can really count on.

Few American films examine money and class, but this one is actually about needing a paycheck. By the end, when each of our protagonists becomes a seller rather than a buyer, we have seen a remarkably sharp dissection of a lifestyle.

In the Q & A afterward, Tolkin said that the genesis of the film came from watching a Melrose shop sink into failure. When I saw the film on its initial release, lines like “It’s not an insult, it’s an intervention” and “We need space” (psychological, but also retail) leaned me toward taking the film as satire. I still do. But Tolkin insists that it’s not. The plot dares to have two truly repellant protagonists, but Tolkin doesn’t find them nasty. “I like them.” He majored in religion in college and he takes his characters’ beliefs, no matter how shallow, seriously—not a big surprise from the creator of The Rapture.

He elaborated on some differences between novels and films. When he rereads one of his novels, he thinks, “How was I ever that smart?” but when he rewatches a film it’s the imperfections that jump out. A movie has to be more compressed and rhythmically varied than a novel—something The New Age demonstrates in its brisk montages alternating with slowly unfolding scenes. In the discussion Jim Emerson praised the film’s density of detail, Tolkin elaborated by invoking William Carlos Williams’ belief in compact expression.

The next two paragraphs include plot details you may prefer to pass over.

Tolkin’s script is indeed firmly contoured. The couple’s crucial quarrel takes place at the thirty-minute mark and launches the two major plot lines. They decide to try a separation (while sharing the house), and they launch their boutique. The development section begins about halfway through, as they conduct their love affairs and watch the shop founder. The last act presents their options: bankruptcy, suicide, low-end work.

Arguably the climax is Peter’s desperate effort to make his first telemarketing sale. Here, I think, Tolkin’s ambivalent sympathies come out. Early in the film Peter had asked a cold-caller whether he ever thought he’d be doing this as a career; it’s less a moral condemnation than glib snobbery. But when Peter has to close the sale, his self-loathing is mixed with a certain pride. The cashiered ad exec finds that he can do this. He’s on the road back.

The gorgeously designed movie, with hard blacks and saturated primaries, has a developing palette (“swatches for each act,” Tolkin says). Unhappily, I can’t study the design arc here because The New Age seems never to have had a DVD release. So much for the Celestial Multiplex. Good old 35mm pulled us through, in a radiant print.

Scholars seem now to agree that film festivals serve as an alternative international distribution system. Like Hollywood’s more formal and routinized machine, festivals bring movies to audiences. Usually the movies are current ones, and a festival is offering local viewers their only chance to see such pictures before video release.

Ebertfest shows that there’s an essential place for what we might call the repertory festival. That’s one that revives and reappraises films from earlier periods—and “earlier” may mean only a few years ago. Jumping from 1929 (Man with a Movie Camera, accompanied by the Alloy Orchestra) to the 1980s (Apocalypse Now, Barfly) and the 1990s (The New Age) and then right up to 2008 (Vincent, Trucker, Departures, Synecdoche, New York, Song Sung Blue), this year’s edition reminds us that every film, old or new, is a part of history.

To come fully into history, I’m convinced, a film needs scale. Even intimate dramas attain their true gravity when spread out like a gigantic picnic on a pale blanket. It’s not the only way to enjoy cinema, certainly; but it’s one that we must never abandon. Like the note-taker in the back row and the geeks up front, everyone needs a full view.

Apocalypse Now Redux.

PS 28 April: I just discovered this piece by Steven Zeitchik, who argues that reviving classics in a big-screen event format could also be good business.

Scorsese, ‘pressionist

Shutter Island.

I was interested in the way she presented herself at that moment. Later on I figured out that as she gets up from the chair we should do it in three cuts, three separate close-ups, because I think he’ll never forget that moment the rest of his life. He’ll play it back many times. . . . It’s just his perception, his memory of what it’s going to be like. . . . We shot it very quickly, two takes each, one at 24 frames, one at 36, and one 48.

Martin Scorsese, on filming The Age of Innocence.

DB here:

Few directors think so carefully about how a film looks and sounds. Sensitive to technique in the work of classic filmmakers, Martin Scorsese has always tried to give each picture a vivid visual and auditory profile. Although he’s often praised for his realism (usually prefaced by the adjective “gritty”), Scorsese is often a subjectively oriented director. This quality goes beyond the justly celebrated performances of his actors. He is unafraid to use unusual cinematic techniques to thrust us boldly into the characters’ minds and emotions. In this effort he joins some great cinematic traditions. No surprise there: He has an immediate sense that film history hovers over every choice a director makes.

Spoilers loom out of the mist ahead.

Inside out, outside in

Raskolnikov.

Once American filmmakers developed a model of visual storytelling in the late 1910s, filmmakers elsewhere were surprisingly quick to push it in more subjective directions. There emerged something like an international division of techniques.

To convey inner experience, German directors of the 1910s and 1920s worked principally on aspects of mise-en-scene—performance, staging, setting, lighting, costume, make-up, and the like. The classic example is The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), in which the cutting and camerawork are fairly conservative, but the setting and acting seek to convey a madman’s vision of the world.

Caligari “subjectivizes” the characters’ surroundings, a process signaled through warped perspectives and fantastically distorted settings.

This brand of visual contortion became the hallmark of what was called German Expressionist cinema. Scholars argue about exactly what films belong under that rubric, but Caligari, along with From Morn to Midnight (1920) and Raskolnikov (1923, above), are pretty uncontroversial examples of making the external world reflect the characters’ psychic turmoil.

At the same period, French directors were also experimenting with subjective cinema. But they tended to concentrate less on mise-en-scene and more on what the camera could do to suggest both optical and mental point of view. In the so-called “French Impressionist” school, we find framings, angles, distorting lenses, changes of focus, slow-motion, and other cinematographic techniques used to suggest characters’ mental states. Thus in Germaine Dulac’s Smiling Madam Beudet (1923), the downtrodden wife sees her husband as monstrous.

In El Dorado (1921) Marcel L’Herbier uses a gauzy filter to suggest that his heroine is distracted, before pulling it aside and letting her face come into focus.

A little later, leading Soviet filmmakers made editing, not mise-en-scene or camerawork, their most salient technique. They experimented with graphic and rhythmic montage, as well as cuts that sacrificed spatial and temporal continuity to eye-smiting impact.

Of course this three-way division of technical labor is too neat. You find some camera experimentation in German Expressionism, as with the fast motion in Nosferatu (1922). The French were using rapid cutting even before the Soviets, as Gance’s La Roue (1923) shows. And some Soviets, such as Eisenstein and the FEKS directors, explored unusual lighting and camera angles. It should be said, though, that these shared techniques often serve different purposes. Fast cutting in Impressionist films tends to suggest the heightened experience of the characters, rather than serving, as in the Soviet case, to dynamize a historical situation for the viewer. The quick cutting in the carnival ride in Jean Epstein’s Coeur fidèle (1923) simulates the chaotic burst of “impressions” felt by the characters, but the quick cutting in the street riot of Strike (1925) doesn’t mimic the characters’ states but aims to arouse shock and suspense in us.

In any case, my technical division remains only a first approximation toward understanding pretty complicated historical trends. The main point is that both the German Expressionist and the French Impressionist filmmakers of the 1920s were seeking to use particular film techniques to give the audience a deeper sense of the characters’ sensory experience and emotional states.

American cinema selectively adopted some of these tactics of lighting and set design. In a blog entry and a web essay, I’ve written about William Cameron Menzies as one importer of the German approach. You can see Expressionist touches in Fox’s Mr. Moto movies. Likewise, 1940s films particularly enjoyed mimicking Impressionist camera tricks to signal drunkenness, delirium, hallucination, and other altered states. Hitchcock’s Spellbound (1945) and Wilder’s Lost Weekend (1945) are famous examples. Typically such Expressionist and Impressionist touches were associated with crime, craziness, or genre stylization. Much of this flagrant irrealism went out of A-pictures in the 1950s, but it survived in horror and, interestingly, in the US avant-garde cinema of Deren, Markopoulos, and others.

One of Scorsese’s contributions to the 1970s, I think, was to revive and consolidate this legacy. While we were celebrating his films as victories for urban realism and neo-Method acting, many of the movies were also charged exercises in subjective cinema.

Making streets mean, and meaningful

Taxi Driver.

From Mean Streets (1973) everyone remembers the aura of street-punk camaraderie, the harsh turns of mood (usually triggered by Johnny Boy’s recklessness), and the vibrancy of the neighborhood, with its social hierarchy and rituals of bullying and bluff and negotiation. Alongside these tokens of realism we find breathless grace notes, as when Charlie glides through the club, a visual equivalent of his joy in being among pals and sexy women. (The shot was made by having Keitel ride the dolly instead of walking in front of it.)

This euphoria of this neo-Impressionist shot is counterbalanced later by the Rubber Biscuit song, with Charlie now thoroughly drunk and floating in grotesque frontal close-up before the floor rises up to kiss his head.

Charlie has come in to the club announcing himself as Jesus, a pious man to create order. Now this shot charts his fall from drunken exuberance into queasiness and mounting anxiety about Johnny Boy’s debt.

More generally, Tony’s club is given heavily unrealistic treatment through slow-motion and faked slow-motion, along with character movement synchronized with the music. If the camerawork mimics Charlie’s mental states in Impressionist fashion, the ruby-red club lighting suggests his erotic inflammation in a mildly Expressionist one.

Taxi Driver (1976) is Scorsese’s most famous venture into subjectivity. From the first shot of the cab heaving through wafting vapor—steam? smoke? sulfur fumes?—we cut to a man’s eyes, and then to dissolving views of the city through a rainy windshield.

From the start Scorsese announces one of his most basic strategies: a realistic motivation for expressionist effects. It’s only rain, but shooting it through the windshield and adding slow motion gives the streets an otherworldly shimmer. As the neon dribbles down the glass, and we see pedestrians moving through tinted clouds like hesitant ghosts, the man’s face becomes bathed in a red glow—vaguely motivated as reflected from the traffic light, but unrealistically saturated, as in the Mean Streets club.

We see the real New York, but filtered through the eyes of a man who considers it an open sewer. The plot will soon lock us into his consciousness more explicitly, through restricted point of view and voice-over diary extracts and crisp montages of the cruising cab. In addition, the motifs introduced here, particularly purifying water and blips of light, will become elaborated in the course of the movie. The general point, however, is that Scorsese has updated Impressionist and Expressionist tactics in order to reveal a man’s mind through images.

Qui tollis peccata mundi

Bringing Out the Dead.

In some films Scorsese plays things straighter, invoking subjectivity only briefly. There are the prizefights and the visions of Vicki in Raging Bull (1980), and the slipperier passages of fantasy in The King of Comedy (1982). But other films plunge us deeply into subjectivity, forcing the world through the filter of a driven character’s sensibility.

For thoroughgoing efforts in this direction we can look to Bringing Out the Dead (1999). In this movie about a paramedic haunted by spirits of those unfortunates he might have saved, Scorsese along with cinematographer Robert Richardson and production designer Dante Ferretti reinvoke the nightmarish qualities of Taxi Driver. The exhilaration Frank Pierce gets from saving lives is offset by his despair at gambling with death every night. The result is another exercise in neo-Impressionism and –Expressionism.

Once again rain and light, objectively out there in the urban world, become projections of the character’s tormented psyche, thanks to camera angle and framing. The windshield gives Frank’s face phantom tears.

Once again concrete shapes and colors, filtered through a moving vehicle, are distorted to suggest the protagonist’s anxieties.

To measure Frank’s descent into desperation, the camera even follows the ambulance upside down, or sideways.

Scorsese ventures into full-blown Expressionism as well. There are naturally dream sequences, but we also get the unforgettable image of the drug dealer Sy, impaled on a fence rail and reaching toward skyscrapers as fireworks (real fireworks?) consecrate his gesture. Later, hurtling through the city and moving closer to mental breakdown, Frank starts to see every woman on the street as Rosa, the woman he could not rescue. How the Germans would have loved having CGI available for such a hallucination.

Perhaps the subtlest touches are the patches of blown-out white. At first they seem a signal of death, gleaming off the bodies of Mary’s father and the young man found on the street.

In the final scene, Frank tells Mary of her father’s death (and sees her as Rosa). She invites him in and eventually he falls asleep in her arms. The final shot quietly shifts from a normal, rather dark texture, to one endowing his shirt with a blinding glow.

This change in lighting and exposure, unmotivated by any realistic source, suggests that Frank feels he has found a bit of peace, while also hinting that a spiritual radiance has entered this unhappy world through a tortured secular saint.

Shutter Island caters to the ‘pressionist side of Scorsese’s vision. It hovers between realism and subjectivity: parts of what we see are really happening in the fiction, while other parts are wholly in Teddy/ Edward’s mind. The difference is that here the balance tips strongly toward expressionism. Apart from the dream sequences, certain hallucinations are rendered in undistorted terms. So, for instance, scenes like the cave conversation with the second Rachel Solando are wholly Teddy’s mental projections. Other scenes oscillate between subjectivity and objectivity, as when Teddy is preparing to set fire to Cawley’s car and talks with his wife Dolores–although the next shot confirms she’s not really there.

I find all this less resourceful than the virtuosic ways in which Scorsese subjectivizes the neighborhoods of New York. The Gothic trappings of the hospital, the cagelike wards, and the rainswept island offer less opportunity for novel stylization than an urban landscape. Moreover, I think that the creaky gimmick ruling the plot of Shutter Island relies on farfetched explanations and leaves too many loose ends. If the storm didn’t really occur, as Dr. Cawley tells us, then did the storm-tossed dialogues with Chuck not occur either? Why are the doctors talking about the prospects of a (nonexistent) flood before Teddy even comes into the room? And could the inmates be relied upon to execute the physicians’ complex role-playing game? A second viewing left me in the dark about matters that a Shyamalan would have tidied up.

But I did have to admire the way in which Scorsese uses Teddy’s breakdown as an alibi for the mismatched cuts I’ve objected to before. (Some legerdemain with a water glass is particularly clever.) And the ending supplies one further twist that somewhat ennobles the whole loopy contraption.

Cranking it up

Crank 2: High Voltage.

You can argue that Scorsese’s talent was well suited to this project: We don’t notice the plot problems because his stylistic assurance carries us along smoothly. That assurance allows me to raise my final point.

I’ve argued elsewhere, in books and on this site, that Hollywood storytelling techniques have been overhauled in recent decades. Over the last forty years or so, filmmakers have amped up the “continuity style” forged in the 1910s. They have cut faster, sometimes averaging 2-3 seconds per shot across a film. They have relied more heavily on singles (shots of one character), and these singles are often fairly large close-ups. Directors have also embraced extremes in lens lengths—very long lenses (for that perspective-flattening effect) and very wide-angle ones (often yielding flagrant distortions). Filmmakers have also relied a great deal on camera movement, frequently tracking in or out or even circling around the characters as they speak. The basic premises of continuity cinema aren’t violated, but the result is more aggressive visuals. Hence my label “intensified continuity.”

I think that intensified continuity became the new baseline for popular filmmaking both in the US and overseas. Over this style, however, some filmmakers have laid lots of fancy filigree. Many flashy techniques fill our movies. We get slow-motion, fast-motion, reverse-motion, ramping, and freeze-frames. There are brutal jump cuts, ragged shifts between color and monochrome, deliberately awkward framings, abrupt overhead compositions, slippery focus, and jerky handheld shooting. On the soundtrack we get ominous rumblings, metallic crashes, and noisy transitions. The Bourne films and The Hurt Locker (2009) offer moderate examples, but edging toward the extreme you have Crank 2: High Voltage (2009). Here intensified continuity has itself been intensified to a height of frenzied artifice. “Over the top” doesn’t capture it. There is, it seems, no longer a top to go over.

This swaggering style takes classical space and time as its basis—we still have analytical cutting, over-the-shoulder shots, and the like—but it pushes beyond the modest demands of simply laying out dramatic elements for easy comprehension. The intensified approach, itself trying for punch, has been raised to a new level of shock and awe. This trend, I’d speculate, is an escalation of tendencies seen in 1970s-1980s filmmakers like Brian De Palma, Ken Russell, Nicholas Roeg, Ridley Scott, and Scorsese.

Scorsese’s stylistic élan proved enormously influential, I think; Mean Streets is virtually a compendium of the new techniques. But unlike some others, he explored the emerging style in order to probe characters’ feelings and moods. Many of today’s amped-up techniques come off as merely eye candy, or prods for visual arousal, or pieces of narrational subterfuge (as often in De Palma). Scorsese has sought to make these decorative techniques more operatic—perhaps in the tradition of Visconti, Michael Powell, and other filmmakers he admires. The images (and of course the music) swirl around the action, providing cadenzas that bring out feelings which his men often can’t articulate. Sometimes the stylistic accompaniment becomes bombastic, as I think Shutter Island largely is. Yet the finest of Scorsese’s pictures contribute to a rich tradition in which the cinema, normally committed to objective realism, makes palpable what goes on inside us.

Scorsese’s remarks on The Age of Innocence come from a Film Comment interview with Gavin Smith reprinted in Martin Scorsese Interviews, ed. Peter Brunette (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1999), 200. For more on Expressionist and Impressionist silent cinema, see our Film History: An Introduction, Chapters 4 and 5. By the end of the 1920s, these tendencies and Soviet Montage were blending into a sort of international style, a development considered in Chapter 8.

Taxi Driver.

PS 24 April: Filmmaker Max Jacoby writes:

I just read your blog entry on Scorsese’s style. You point out the glowing light which appears in some scenes of Bringing out the Dead. That is actually a signature lighting effect of cinematographer Bob Richardson. He has used this before he came into contact with Scorsese. You can already see it in some of the Oliver Stone films that he shot, such as JFK. This glowing effect is achieved by combining an overexposed toplight (several stops over key) with a diffusion filter (such as a White Pro Mist) in front of the lens or a net behind the lens. You can actually see the pattern of the net in question on the close-up of Nic Cage that you picked; it clearly stands out from the out-of-focus highlights in the background.

The net is more than likely a Christian Dior Denier 10 stocking, made of silk. They are very sought after and hard to find nowadays, because Dior stopped making these some years ago and switched to nylon instead. Once that became known, you had plenty of cinematographers invading women’s underwear stores to buy up the last remaining stock!

Max’s point helpfully indicates how a director can give a DP’s preferred choice a particular function. It seems to me that Scorsese’s patterned usage of the glowing white patches creates a significant motif in the movie–especially when it dominates the last shot, always a crucial moment. Thanks to Max for this, and for a followup reference to Eric Rudolph’s article, “Urban Gothic” in American Cinematographer 80, 11 (November 1999), 30-41; available here. In it Richardson discusses the flaring whites I mention in the blog entry.

That reminds me …

Enter the Frog Footman in Alice

Kristin here:

One film I can’t work up much enthusiasm about is everywhere, and another I very much want to see doesn’t seem to have a North American distributor. Luckily each reminds me of an older film that isn’t widely enough known. This seems like the perfect chance to point them out.

Recently the latest Screen International, in its new monthly format, arrived, with literally back-to-back reviews of the two films: Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland and Sylvain Chomet’s The Illusionist.

Let me say first off that Johnny Depp looks great in eyeliner, as in Pirates of the Caribbean. He looks positively grotesque with pink lips and raccoon eyes. Of course, grotesque could work well for Alice, especially as adapted by Burton. Yet the reviews suggest that the film is actually tamer than one would expect. Screen International’s Brent Simon calls Burton’s film: “A gorgeously mounted but fundamentally humdrum telling of Lewis Carroll’s fantasy novels” (March 2010 issue, p. 61). Variety’s Todd McCarthy makes a similar remark: “But for all its clever design, beguiling creatures and witty actors, the picture feels far more conventional than it should; it’s a Disney film illustrated by Burton, rather than a Burton film that happens to be released by Disney.”

Back in 1951 Disney did a fine version of Alice in Wonderland, one which does capture something of the lunacy of the original. It also benefited from the talent of some of the studios’ best artists, including Mary Blair. Always worth going back to.

But if one wants a truly surrealist, unconventional adaptation, I doubt if anything can top Jan Švankmajer’s feature Něco z Alenky, aka Alice. David and I saw it in a theater when it was released in the U.S. in 1988. It was my first exposure to the great Czech surrealist animator, and we gradually caught up with his earlier films. At the time it had a considerable success on the art-cinema circuit, though I’m not sure how well known it is among younger film fans.

Švankmajer had used both live-action, as in his morbid documentary The Ossuary (1970), and stop-motion animation of objects, as in his brilliant, dark look at human relations, Dimensions of Dialogue (1982). DVD anthologies of his shorts are available. Kino Video’s “The Collected Shorts” volume isn’t as complete as its name may imply. It’s missing several films including The Last Trick, his first but far from least film, and what may be his very best, Jabberwocky (1971), a non-narrative short incorporating Carroll themes. If you’ve got a Region 2 or multi-standard player, opt instead for “Jan Švankmajer: The Complete Short Films,” from the British Film Institute. It has a third disc with extras.

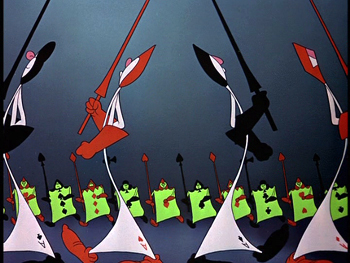

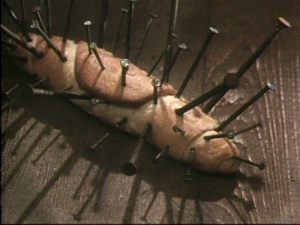

Alice is suffused with a marvelous imagination. Many of the characters are museum specimens. The White Rabbit begins as a stuffed creature in a Victorian glass case, freeing himself by pulling up the nails that keep him rigidly posed. Breadrolls sprout quills made of nails, and unnatural skeletons of creatures straight out of a Bosch painting creep about.

Švankmajer takes advantage of the mingling of two-dimensional figures based on playing cards and three-dimensional figures in ways that few adapters of Alice in Wonderland have managed, as when the White Rabbit passes the Queen of Hearts in a stage setting built of painted flats:

The Mad Hatter in Švankmajer’s film is definitely not Johnny Depp. He’s an antique wooden puppet of the sort that often crops up in the filmmaker’s work. He’s also not as loquacious as the chap in the book. The March Hare, who is definitely mad, steals the scene from him. Buttering a watch’s innards is a pure Švankmajerian gesture.

Alice was Švankmajer’s first feature film. In it he mixed live-action in with the stop-action more than in most of his shorts, presumably in part as a way to save money in making a much longer film. When Alice is full-size, she is played by a real girl, but when she shrinks she becomes a pixilated doll. It works well in this case, but the filmmaker depended more and more on live-action in his later features, like Faust (1994), with animated interludes becoming rarer and rarer. I found these features less entertaining and original and more heavy-handed in their social commentary. (The shorts contained vicious satire, but it was often rendered in bizarre, striking ways that made it palatable.) After thoroughly disliking Conspirators of Pleasure (1996), I gave up on his new films and stuck with the old ones. He’s making one now, called Surviving Life, which he apparently has said will be his last.

A final word on Alice. As should be obvious, this isn’t your charming adaptation for children, at least small ones. Alice points that out during the credits, “Now you will see a film made for children. Perhaps.” Most kids these days seem to be more hard-boiled than in my youth, but seeing this film at age 10 would have left me with nightmares. The White Rabbit, scarier than any fuzzy little bunny I’ve ever seen (including the one in Monty Python and the Holy Grail), runs around with scissors, quite willing to obey the Queen of Hearts’s order, “Off with her head!”; the little skeleton creatures crawl over Alice; and creepy glass eyes give staring life to inanimate objects like the Frog Footman or the sock that turns into the Caterpillar:

They tend to stare right out at us, too.

Tati on Parade

Most readers of this blog will be familiar with the great Jacques Tati. But it was news to me that he had left an unproduced screenplay, finished in the 1950s and now adapted by French animator Sylvain Chomet. Those who saw Chomet’s first feature, the 2D animated film The Triplets of Belleville (2003), probably noticed the occasional Tati homage lurking in the backgrounds and on the walls. Now Chomet’s admiration for Tati has emerged front and center in his second animated feature. The Illusionist‘s protagonist is modeled directly on Tati; he’s a old-fashioned magician eking out a living in the fading world of music-halls. (The Russian trailer has been posted here; apparently that’s the only footage on the internet so far.)

The Illusionist premiered at the Berlin Film Festival this year and met with a warm reception from critics. Writing in Screen International, Lisa Nesselson calls it “a delightfully bittersweet valentine to the music-hall tradition” and says that its animation “simply could not be better” (March, 2010 issue, p. 62). Leslie Felperin’s Variety reviews dubs it “a very happy marriage of Tati’s and Chomet’s distinctive artistic sensibilities.”

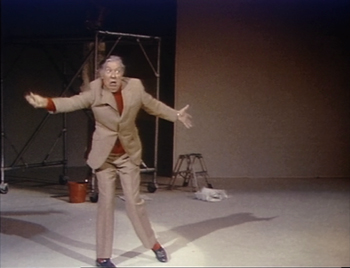

While we are waiting for an American distributor to pick up the film (ahem!), let me recommend Tati’s least-known feature. After his financial difficulties in the wake of Play Time‘s high budget and tepid box-office performance, the director set out to make Traffic, his last film featuring his M. Hulot character. Funding on this film collapsed midway through shooting, but Swedish TV stepped in and bailed the production out. Traffic came out in 1971, and in exchange for the assistance Tati made the 85-minute telefilm Parade (1974).

It has been available on French DVD (now out of print), but now the British Film Institute has released its own edition. The transfer isn’t the greatest, though it seems to be the same or similar to the French version. It smooths over the peculiarities of the original film. David and I saw it in 35mm in Brussels (where we also saw The Triplets of Belleville). It was obvious that while most of the film had been shot on somewhat fuzzy video in front of a live audience, some acts had been staged in a studio on crystal-clear 35mm. It was an oddly mixed format for an odd film. The BFI version also features optional English subtitles. Given the paucity of audible speech, they don’t seem vital.

After the audience files in and takes their seats and an opening parade introduces the main acts, Tati steps forward as emcee and informs the spectators that they will be as much a part of the show as the performers onstage. Sure enough, the audience has been staged by Tati, accoutered in outrageous, colorful outfits and instructed to turn their heads back and forth rhythmically during his tennis routine or to bounce balloons around. Occasionally “ordinary” people from the stands step forward to challenge the acts onstage, trying and sometimes succeeding in out-doing them in magic or musical performances. The black-and-white life-size cutout people that had been used as extras in the backgrounds of scenes in Play Time return here as prominent members of the audience and even the stage acts. In the scene of Tati’s mime of a goalie (see below), the cutouts provide an unmoving backdrop to the action.

After the audience files in and takes their seats and an opening parade introduces the main acts, Tati steps forward as emcee and informs the spectators that they will be as much a part of the show as the performers onstage. Sure enough, the audience has been staged by Tati, accoutered in outrageous, colorful outfits and instructed to turn their heads back and forth rhythmically during his tennis routine or to bounce balloons around. Occasionally “ordinary” people from the stands step forward to challenge the acts onstage, trying and sometimes succeeding in out-doing them in magic or musical performances. The black-and-white life-size cutout people that had been used as extras in the backgrounds of scenes in Play Time return here as prominent members of the audience and even the stage acts. In the scene of Tati’s mime of a goalie (see below), the cutouts provide an unmoving backdrop to the action.

The BFI DVD includes a brief but informative booklet with essays by Philip Kemp and Jonathan Rosenbaum. As Kemp  points out, the acts out of which Tati built his film are, apart from himself, not much to boast about: “His colleagues’ juggling, acrobatics, and, literally, horseplay (much use is made of an upright piano that doubles as a vaulting-horse) are diverting but nothing special.” Yet that, I suspect, is part of the underlying strategy. The film is quite Tatiesque, despite its lack of M. Hulot or a real plot. The juxtaposition of the three separate spaces of the audience, the stage, and the carpenters’ shop directly abutting the performance space, allows the creation of the sort of visual jokes that Tati loves. It also permits a flow between roles, as when the “carpenters” emerge briefly to juggle with their brushes or to play their tools like xylophones before returning to work. All these performers are quite good, but really great acts would distract from the best act of all: Tati’s overflowing visual imagination.

points out, the acts out of which Tati built his film are, apart from himself, not much to boast about: “His colleagues’ juggling, acrobatics, and, literally, horseplay (much use is made of an upright piano that doubles as a vaulting-horse) are diverting but nothing special.” Yet that, I suspect, is part of the underlying strategy. The film is quite Tatiesque, despite its lack of M. Hulot or a real plot. The juxtaposition of the three separate spaces of the audience, the stage, and the carpenters’ shop directly abutting the performance space, allows the creation of the sort of visual jokes that Tati loves. It also permits a flow between roles, as when the “carpenters” emerge briefly to juggle with their brushes or to play their tools like xylophones before returning to work. All these performers are quite good, but really great acts would distract from the best act of all: Tati’s overflowing visual imagination.

Ultimately, though, the main boon of Parade was to preserve for posterity Tati’s famous series of sport-based pantomimes that he had developed in the 1930s, when he was a successful stage performer. He started off on the same music-hall stage that he celebrates in Parade and now, posthumously, in The Illusionist. Some of these mimes, such as the man-and-horse trick rider, the over-confident goalie, the over-the-hill boxer, or the disappointed fisherman (bottom) may have remained unchanged across Tati’s career. (After he became famous as a filmmaker and actor, he often had the chance to perform these brief skits on TV variety and talk shows.)

Horse-man

Goalie

Boxer between rounds

Tennis in slow motion

There’s one magic moment in these mimes, however, that Tati presumably updated. During the tennis match, he lapses briefly into slow motion. Not a slow motion achieved in the camera, which keeps running at normal speed. No, he mimes a player as seen in slow motion, quite convincingly and yet moving in ways that one wouldn’t consider possible for the human body. It’s hard to describe, but believe me, it’s amazing to watch.

Tati’s performances as the postman in Jour de fête or as Hulot in the four films featuring that character are usually not flashy. They’re designed to merge into the story and make the hero one of many amusing characters in an ensemble. But in Parade, with the pantomimes performed outside a narrative context and primarily against dark or blank white backgrounds, we can savor the man’s dazzling skill. His utter control of every gesture echoes his directorial mastery of every stylistic component of his films. In Parade, the moments when he tries to subdue a flapping fish before it escapes or when his head snaps back in reaction to an imaginary opponents’ blows are mindboggling in their precision. He was a great actor before he was a great filmmaker, and fortunately that early skill lingered long enough to be recorded.

Gone fishing