Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

Paris fun, in at least three dimensions

What he saves films from: Serge Bromberg faces down the flames.

We’re ending the first week of three in Paris. At the invitation of Jean-Loup Bourget and Françoise Zamour, David is giving three weekly lectures at the École Normale Superieure. He’s introducing some ideas about the development of film style in the 1910s and early 1920s, updated with new material from his summer research in Denmark and Brussels. Jean-Loup and Françoise have proven excellent hosts, and the first lecture seemed to go well.

We thought that Paris in January might be chilly and rainy, but we figured it had to be warmer than Madison. It turned out that Paris is experiencing unusually cold weather—about what would be normal in Wisconsin. There was light snow yesterday and last night, and the wind-chill factor was enough to turn our fingers numb if we stayed out long enough. The fountain in the center of the intersection at the northeast corner of the Jardin de Luxembourg has gradually become an iceberg.

We thought that Paris in January might be chilly and rainy, but we figured it had to be warmer than Madison. It turned out that Paris is experiencing unusually cold weather—about what would be normal in Wisconsin. There was light snow yesterday and last night, and the wind-chill factor was enough to turn our fingers numb if we stayed out long enough. The fountain in the center of the intersection at the northeast corner of the Jardin de Luxembourg has gradually become an iceberg.

Turns out, though, that it is still warmer than Madison, which is having highs in the single digits, as the weather forecasters say, and lows below zero. We’re better off here, though we wish we had brought our parkas.

It’s like Avatar, but much shorter

KT here:

The cold has driven us indoors, to museums and movies. As always seems to be the case, the Cinémathèque Française is hosting retrospectives of American films—in this case works by Laurel and Hardy and Gordon Douglas. There’s also a 3D series, which caught our attention right away. It’s not just your standard Kiss Me Kate and Dial M for Murder programming. In addition to such classics, there are many obscure films. We happened to arrive in time for the final two programs of the series, which ran from December 16 to January 3.

Our first full day in Paris ended with an evening of shorts presented by Serge Bromberg, who in 1985 founded Lobster Films. Lobster has put out many DVDs by now, some of which we have reported on previously, here and here. In July, one of our entries on Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna mentioned that Serge presented a program of Georges Méliès films, in conjunction with the French release of Lobster’s huge DVD set of the great magician’s films.

Serge is quite a showman and obviously a popular figure, since there was a large crowd, including many families with children. On Saturday he chose and introduced a set of short 3D films in his series of programs usually titled “Retour de Flamme,” or “Saved from the Flames.” To begin the evening’s entertainment, he explained how, unlike modern celluloid 35mm film, the nitrate variety used up until the early 1950s ignites and burns easily. With the help of a rightly apprehensive volunteer holding up a film-can lid, Serge showed how modern celluloid catches fire only briefly and then dies out. The few inches of nitrate, however, flared up quickly.

Serge introduced each film thereafter, playing the piano to accompany the silents. The audience had been given both anaglyph (red-green) and polarized glasses, and Serge’s introductions to the films gave us time to switch between systems.

Many of the shorts shown on the program are available on DVD or YouTube, but the 3D effect plays best on the big screen. The evening began with an unannounced item, Three Dimensional Murder, a “Metroskopics” comedy short from 1942. A nervous detective visits a mysterious house and encounters Frankenstein, creeping hands, skeletons, and other ghouls and beasties, all of which find some occasion to throw things or hurl themselves toward the camera. The humor is, as a contemporary audience member might have said, pure corn and the 3D effects repetitive, but it was certainly a rare item.

Next came one of the Fleischer brothers’ cartoon shorts, Musical Memories. It was made with a patented system that used three-dimensional models as settings against which 2D cartoon figures drawn on cels moved about. (Such models can be seen fairly often in Popeye and other Fleischer cartoons of the 1930s.) There is some sense of depth. Still, the effect is strange, since the models have shading and the flat-looking figures do not. The cartoons are not 3D in the sense we typically think of, since there are no glasses involved.

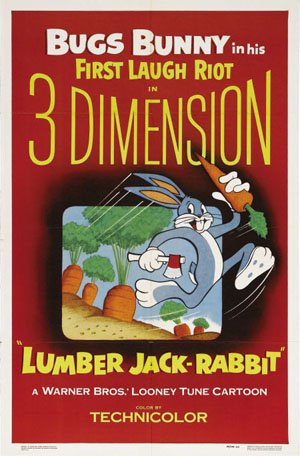

More cartoons followed, from the two main competing animation studios. Disney’s contribution was Working for Peanuts, a story set in a zoo with Chip and Dale stealing peanuts from an elephant and Donald Duck trying to foil them. Many a peanut seemed to fly out toward the spectator. Chuck Jones directed Lumber Jack-Rabbit (1954), a film that mixed size gags and spatial ones, with Bugs wandering into the domain of the gigantic Paul Bunyan. Perhaps not one of Jones’s best, but distinctly more interesting in 3D.

As Serge pointed out, most 3D technology was pioneered in the U.S. He included some exceptions, however, with a series of Soviet “Parade of Attractions” shorts shown at intervals during the evening. Experiments with underwater 3D photography and a garden of plants lacked soundtracks, but the final item, a vaudeville act with jugglers, had music and lots of bowling pins flying at the camera.

Unbelievably, there were efforts toward 3D as early as 1900. Serge showed some 3D experiments from that period by inventor Rene Bunzli. These were only about 10 seconds long and included a mildly risqué scene of a man arriving to visit his mistress and another discovering his wife in bed with her lover. The first color 3D film was shown: Motor Rhythm, made by Charley Bowers in 1940 for the Chicago Exposition and distributed by RKO. Using a combination of pixilation and 3D, the film shows a car jauntily assembling itself to a musical accompaniment, with many of the parts moving out toward the camera before attaching themselves in their proper places.

The National Film Board of Canada contributed Munro Ferguson’s Falling in Love Again, with characters wafted into the sky by road accidents and, while falling, falling in love. To watch it in high-quality 3D, go here. Pixar was represented by John Lasseter and Eben Ostby’s early digital experiment in 3D, Knick Knack, as a snowman trapped in a snow globe tries to break free to join a bathing beauty.

The evening ended with a surprise, two films that had never been meant to appear in 3D.

Méliès’s early shorts were often pirated abroad, and a lot of money was being lost in the American market in particular. After the Lubin company flooded that market with bootleg copies of a 1902 film, Méliès struck back by opening his own American distribution office. Separate negatives for the domestic and foreign markets were made by the simple expedient of placing two cameras side by side. The folks at Lobster realized that those cameras’ lenses happened to be about the same distance apart as 3D camera lenses. By taking prints from the two separate versions of a film, today’s restorers could create a simulated 3D copy!

Two 1903 titles–I think that they were The Infernal Cauldron and The Oracle of Delphi–triumphantly showed that the experiment worked. Oracle survived in both French and American copies, and the effect of 3D was delightful. For Cauldron only the second half of the American print has been preserved. Watching the film through red-and-green glasses, you initially saw nothing in your right eye, while the left one saw the image in 2D. Abruptly, though, the second print materialized, and the depth effect kicked in. The films as synchronized by Lobster looked exactly as if Méliès had designed them for 3D.

Film scholars gone wild

DB here:

William Cameron Menzies is most famous as an art director on films like The Thief of Baghdad (1924) and Gone with the Wind. He was one of the most visually daring artists to work in classic Hollywood; his eccentric framings and looming foregrounds may have influenced Orson Welles. (The Gothic distortions of Our Town and Kings Row are unlikely to be the creation of director Sam Wood.) Menzies also directed a few films, most notably the slightly nutty anti-Commie film The Whip Hand (1951).

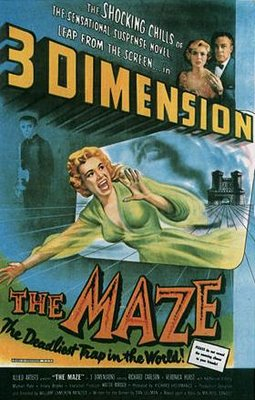

So Kristin and I had to go back to the Cinémathèque for Menzies’ rarely-seen 3D feature The Maze (1953). Alas, it was a washout. The feeble story concerns an heir returning to a castle to confront a giant frog, who may be his relative. I’d expected bravura deep-focus, with planes jutting out at me, but the film was dramatically and visually flat–no wordplay intended. The trailer, complete with fake bats on strings, is here.

We have other incidents to chronicle, but this dispatch can end with a quick list of some of the film friends we’ve encountered. We’ve already mentioned Professor Bourget, whose book on Fritz Lang came out recently (below left). We also ran into Cindi Rowell, an old friend from Pordenone and The Griffith Project, who had the excellent idea that we go to Chinatown–here hidden behind the facades of tower blocks. Cindi has vast experience in many aspects of film culture–preservation, programming, publication, web design, and the like–and is currently affiliated with the Middle East International Film Festival in Abu Dhabi.

Another old friend, Yuri Tsivian, is in Paris teaching during our visit, so we had a chance for a good dinner and lots of talk about editing in the 1910s. Below, he and Kristin pay homage to one of the shrines of Parisian cinephilia, the Studio des Ursulines movie theatre.

Left: Jean-Loup Bourget and his new book on Lang. Right: Yuri and Kristin at the Urselines.

Last night, with Kristin away in Berlin, I went to a dinner hosted by Jacques Aumont and Lyang Kim. Jacques is a major film theorist, whose many books and essays probe into the artistic qualities of cinema. His book on Eisenstein is available in English translation, as is his far-ranging study of the history and functions of images. Lyang is an outstanding photographer, whose book of haunting Christmas images Dans l’ombre de noël was just published in December. Among her pictures here are some gorgeous “fusion” images that recall our recent 3D experiences.

Then who should turn up but Marc Vernet and Rick Altman? It was an Iowa-Wisconsin reunion in the 10th. Marc is an expert on film noir, on cinematic images of absence, and on the American film company Triangle–associated with both Griffith and Ince. (Again, the 1910s.) Marc has set up a beautiful webpage full of information about early American cinema, and he blogs there frequently. Rick is known for his in-depth studies of film genre (especially the musical), film sound, and narrative theory. His most recent books, Silent Film Sound and A Theory of Narrative, are splendid contributions. Below, all four toast what turned out to be Rick’s birthday.

Today: More preparations for my lecture tomorrow, and of course at least one movie. Agora? Wiseman’s La Danse? Kinatay? The new Eugène Green, La religieuse portugaise? Or a rerelease (new print) of Minnelli’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse? Or….? The usual Parisian problem, but a good problem to have.

P. S. March 2010: After this Paris trip, I wrote an essay on William Cameron Menzies for this site.

Jacques Aumont, Lyang Kim, Rick Altman, and Marc Vernet, 9 January 2010.

Tell, don’t show

Exodus.

DB here:

Watching the film adaptation of Stieg Larsson’s Girl with the Dragon Tattoo reminded me how common fragmentary flashbacks have become. Granted, we’re living in a period of flashback frenzy, one comparable to the delirious 1940s and 1960s. But the format of the flashbacks has changed a bit. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, like many other films, gives us mere glimpses of earlier events–literally, flashes back to the past.

The technique is actually quite old. American films of the 1910s often interrupted present-time scenes to remind us of actions we’ve already seen or been told about. But the fragmentary flashback waned during the heyday of sound cinema. There conversations did nearly all the work. Of course there were flashbacks, as I’ve discussed in an earlier entry. But those flashbacks tended to be extended scenes, not the jagged bursts we get now.

A cynic might say that today’s audiences are so thick-headed and impatient that simply mentioning what happened earlier isn’t enough. Viewers now would chafe at the long interrogations in The Maltese Falcon and The Big Sleep. The scenes would need to be split up by images showing what the characters were explaining. The new rule: Add redundancy, but dress it up in whipcrack visuals.

So are the flurries of mini-flashbacks there just because filmmakers doubt that viewers can follow a twisty intrigue given in dialogue? Not necessarily. I suspect that these flourishes are traceable to a piece of current screenwriting advice. It’s usually formulated as Show, don’t tell.

The very distinction has some ancient ancestry. Plato and Aristotle both distinguished between verbal narration, as in the Homeric epics, and theatrical presentation. Aristotle, always more interested in craft than Plato, went on to point out that the distinction couldn’t be absolute. Epic narration could include simulated conversations, for example. Aristotle did not, so far as I can tell, urge composers of epics to avoid “showing” or dramatists to avoid having characters report offstage action.

Today’s bias in favor of “showing” is probably traceable to the emergence of the modern novel. “Dramatize, dramatize!” Henry James (a failed playwright) advised the novelist. That is, make the action on the page seem vivid and palpable. It was Joseph Conrad, not D. W. Griffith, who first claimed that his purpose was “to make you see.” A major trend in the theory of prose fiction ca. 1900 was the effort to turn words on the page into a surrogate for visual storytelling; hence the very term “point of view” and James’ comparison of unfolding narrative to a “corridor” that we traverse. It remained for Percy Lubbock, in The Craft of Fiction (1921) to sum up this trend. “A novel is a picture,” he claimed, and he suggested that novels, either “panoramic” ones like Vanity Fair or “dramatic” ones like The Awkward Age, can make us forget that they are actually verbal contraptions:

The art of fiction does not begin until the novelist thinks of his story as a matter to be shown, to be so exhibited that it will tell itself.

Screenplay manuals have picked up on the general advice, even while modifying it to suit the particularities of film. Novices are advised to reduce dialogue to the minimum. Even a novel committed to “showing” will rely on conversation, but in cinema long stretches of dialogue, and especially, God forbid, monologue are uncinematic and run the risk of boring the audience. Cinema, the reasoning goes, is a visual medium, and whenever you can replace a word, or a string of them, by images you should try to do so. The aim is what we now call visual storytelling.

Now I’m all for presenting the story through pictures. Show, don’t tell can challenge the screenwriter and director to get story points across through imagery and character behavior rather than expository dialogue. One mark of filmmaking skill is to guide the audience to make inferences rather than simply take in bald information.The question is: How far to go?

In their urge to picture every bit of action, contemporary filmmakers may be missing a chance to exploit another resource of cinema: the sustained scene in which a character talks about a past event without any visual supplement. A long verbal account of the past has unique virtues.

In other words: Filmmakers, consider telling and not showing what’s told.

Talking it through

In Persona, the nurse Alma has grown more intimate with her patient Elisabeth, a famous actress who has frozen on stage and now refuses to speak. During their time together, Elisabeth’s treatment becomes therapy for Alma. Compelled to fill the silences, she gradually reveals more about herself. Tonight, a little drunk, Alma confesses something shocking. Once, while her lover was away, she and a girlfriend had sex with a couple of young men. Her telling of it makes her more and more distraught, until she breaks down weeping in Elisabeth’s arms.

In this nearly seven-minute monologue, Alma describes the incident. She mentions a few details, such as the weather on the isolated beach and the blue ribbon on her straw hat. Mostly, though, she simply describes what happened, in laconic but vivid sentences. The result is an anecdote of absorbing eroticism. Lacking any images of the events, we get to imagine the scene of sexual exchange. Bergman releases us from what James once called “weak specificity”: perhaps no imagery this side of pornography could be as arousing as this bare-bones account.

But the fairly neutral words are given emotional coloration through Alma’s manner of telling. Her reaction mixes astonishment at the pleasure, guilt at betraying her lover, and shame in telling it to Elisabeth. By the end, she collapses into weeping confusion; the incident has made her doubt what sort of person she is. Here Bibi Andersson’s performance is crucial, with trembling sincerity giving way to anguish and self-reproach.

In sum, by presenting this monologue wholly in the present, Bergman gives us two layers of action simultaneously, a charged sex scene and its long-range emotional consequences. But there’s more. Had he given us flashbacks, he could not preserve the flow of the present-time action. The staging and cutting during Alma’s confession use simple film techniques, but they add another layer to the scene.

The master shot, seen above, gives us the two women as Alma begins her tale. Then straightforward analytical editing isolates each woman.

In a classic gesture of intensification, the next shots of Alma and Elisabeth are closer than the earlier ones. This pair of shots accompanies the highest point of what Alma is telling us—the first couplings.

The tight shot of Alma, in which she describes achieving orgasm, lasts almost two minutes and is the lengthiest shot in the sequence. Then the action pauses as Alma nervously curls over to grab a cigarette, goes toward a distant window to light it, then settles on the sill to resume her story.

The earlier close shot of Elisabeth had hidden her reaction behind her hand. Now she watches Alma in a sort of enjoyment. Friendly empathy or triumph at eliciting a damaging admission? It’s hard to say. Alma retreats to another window and turns away, as if responding to Elisabeth’s smile.

Alma finishes her tale by saying that that night, reunited with her lover, she had the most pleasurable sex of their relationship. Turning from the window, her face is angled in such a way that her confession seems at once indifferent to Elisabeth (the eyeline doesn’t seem angled toward the bed) and challenging to her: “Can you understand that?”

The next line of dialogue—“And I got pregnant of course”—introduces a rupture in the action’s space and time.

Now Alma is in bed with Elisabeth, as if her question had impelled her to the closest physical contact yet. As Alma twists in pathetic uncertainty, weeping, Elisabeth’s reaction is again initially suppressed (Alma’s arm blocks her patient’s eyes) before finally revealing Elizabeth’s face during the embrace. Yet the expression remains ambiguous—sympathetic, or victorious in having exposed her nurse’s inner life.

Later we will learn that Elisabeth’s caresses aren’t as affectionate as they might first appear. In any event, given the tenor of Alma’s revelation, it is hard not to see them as erotic gestures in the present, parallel to those Alma recounted.

By telling rather than showing, then, Bergman has been able to tell and show. Bergman lets Alma’s telling provide a sort of virtual flashback, while he also creates a ripening interchange between characters in the present. Instead of simply sandwiching fragments of the past into the present action, he has built up two smooth arcs of action, one that we imagine and one that is set before us in precise detail, with its own emotional modulation. The bliss of the past events is refracted through the pain of telling them.

Telling as therapy

Part of the rationale for telling rather than showing the beach orgy is, of course, the fact that much of it couldn’t be presented so literally on film; censors would object. More important is the fact that showing a heavy-breathing sexual encounter would be likely to undercut the developing revelation of Alma’s present feelings, the tension between the memory of uninhibited pleasure and the lingering shame and confusion.

The issue of what should be shown comes up in another classic scene of confession, the moment in Exodus when the Jewish teenager Dov Landau admits that he was an accomplice in running a concentration camp. Again the result is a tearful breakdown. Here, however, a conversational partner coaxes out the truth by quietly corrosive questions.

Dov is trying to join the Irgun, a guerrilla band seeking to drive the British out of Palestine. The senior officer, Akiva Ben Canaan, lets the cocky youth expand on his boast that he began fighting Nazis in the Warsaw ghetto but then was captured and sent to Auschwitz. At first Akiva probes gently. How did the camp officials decide who would live? And what did the Nazis do to the girls? Dov starts to shift uneasily. How was the killing accomplished?

Like Bergman, Preminger employs the standard method of providing closer views as the tension rises. Dov starts to relax as Akiva provides softball questions, but then he has to confess that the bodies were dumped in mass graves. Who dug the graves? Dov admits that demolition squads used dynamite to blow out trenches. Akiva induces him to admit that this was Dov’s job.

In the course of all this, Akiva moves around the room and leans closer to Dov, but the boy remains motionless in the same setup. The fixed framing accentuates his subtly changing expressions across the scene.

Akiva retells what Dov must have done: shave heads, collect bodies, harvest gold fillings. Dov crumples like a child under the admission (see the frame surmounting this entry), and like Alma at key points in her monologue hides his face in shame. “What could I do?”

What else has he to confess? Dov won’t say, until he collapses again: “They used me . . . like you use a woman.”

The distant framing here prepares for the scene’s final phase: the men rise and swear Dov into their group.

Today a filmmaker would be tempted to show at least some of what Dov tells us. We could get glimpses of life in the camp, along with subjectively distorted imagery of sexual abuse, perhaps from Dov’s point of view. But this could turn out to be James’ “weak specificity.” “Let the reader think the evil,” James advised. Accordingly, Preminger sticks obstinately to what Dov says and how Akiva’s softly voiced but damning interrogation brings out the truth.

Again, the scene’s power comes from the character’s emotional development during the telling. We can imagine the horrors that Dov faced as a boy, and our pity comes from empathizing with his changing expressions–bravado, ruffled concern, realization that he has been caught lying, revulsion at his betrayal and the sexual assault. That is, we sympathize through his response now, rather than through direct vision of what he encountered. We react to his reactions.

By the end, Dov seems dazed that his confession has been accepted. Partly this is surprise that he isn’t being rejected, but also it’s as if he has awakened from a dream–that of himself as a resistance hero. Akiva Ben Canaan forces him to confront what he had not faced. Once more, the confession becomes a talking cure.

As in Persona, the confession also characterizes the interlocutor. Akiva ‘s gentle manner fuses wisdom and severity, making him a quietly stern father confessor. He’s also a shrewd exponent of psychology, one who picks the moment of the boy’s greatest self-revulsion to declare that Dov is accepted into the Irgun. The confession has broken him; the Irgun will remake him. Having surrendered himself utterly he will prove a more loyal soldier than any recruit with an innocent past.

Again, the scene of telling has given us two continuous emotional arcs in two time frames, one concrete and one virtual: a past event we’re cued to imagine and a present stripping away of the teller’s defenses. People who complain that the dialogue scenes in Inglourious Basterds are overlong should consider the tradition of movies like Exodus and Persona.

Psycho babble

Persona and Exodus suggest two virtues of sustained recounting: arousing the viewer’s imagination, and providing an unbroken arc of present-time action that can generate sympathy through face, gesture, and voice. There’s one more advantage that isn’t perhaps so evident nowadays.

Current films give us “lying flashbacks” fairly often. But in the old days, with very few exceptions like courtroom films and tales like Rashomon, a flashback was veridical. In recounting a story action, a character might lie or make mistakes, but if the film’s narration showed us that action, we could trust that as the truth. As a result, many detective stories presented suspects’ versions of events through question and answer but climaxed in a flashback that showed us what really happened.

If, however, you want to induce doubt about what really happened, you might have the detective’s climactic explanation pricked by inconsistencies. This is what seems to me to be happening at the finale of Psycho. (Do I really have to warn about spoilers here?)

After Norman Bates has been captured, halted in another murder attempt, the psychiatrist Dr Richmond explains the young man’s split personality—part Norman, part Mrs. Bates, his mother. Richmond claims to have gotten the truth “from the mother.” At this point, he says, the Mom part of Norman has taken over wholly, a claim confirmed when we hear Norman speak in an old lady’s voice in the epilogue. Richmond goes on to claim that his questioning determined that Mother “killed the girl.” To get literal, it was as Mother that Norman murdered Marion Crane.

A contemporary film would very likely replay the murder so as to validate the psychiatrist’s analysis: Norman dressing up as his mother, assuming a cackling old-bat accent, killing Marion in images that fill in the silhouette that we saw in the shower sequence. We would see that Norman-as-Mother is the culprit.

But this visual confirmation of Richmond’s diagnosis would be made problematic by the epilogue that Hitchcock includes. In the final sequence we see Norman, staring out at the camera, and hear Mother’s voice declaring that her son committed the murders. According to her, Norman is the culprit; she wouldn’t hurt a fly. How then can Richmond declare that Mother told him that she killed the girl?

We might say that the doctor is extrapolating: the truth he took from the mother is that she is dissembling, shifting the guilt to Norman. But Richmond could have stated that was his reasoning, and he doesn’t. The incompatibility between his explanation and Mother’s soliloquy opens up the possibility that he has not probed to the depths of Norman’s madness.

Despite the fact that the psychiatrist’s analysis arrives at the moment when a conventional movie delivers the whole truth, the very last minutes of the film incline me to doubt Richmond’s ability to grasp the whole situation. It’s as if our parting vision of the character disturbs the smug certainties of the diagnosis.

I haven’t dived deeply into the Talmudic sea of Psycho commentary, so it’s likely that this issue has been hashed out extensively. Perhaps my construal won’t stand up. Take it, then, as a possible instance of the ways in which a verbal recounting, “unconfirmed” by a tangible flashback, can stand as only a candidate explanation rather than the whole truth. In general, telling and refusing to show can induce what Meir Sternberg calls “anticipatory caution,” a warning that the telling is only one, and not necessarily the most truthful, version of events.

Show, don’t tell is usually good advice. But I’m suggesting a codicil. Consider showing the telling. Fill it out. Pack it with actorly detail and psychological implication. Stage and shoot and cut it so as to create an engrossing, unfolding rhythm. That’s visual storytelling too, and it requires fine judgment. Who knows? More scenes relying on telling might also teach audiences to be a little patient.

The best modern account I know of the subtle differences between showing and telling, and the cases when the categories blur and fracture, can be found in Meir Sternberg’s Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction. I talk a little about the distinction in Chapter Two of Narration in the Fiction Film. See also The Way Hollywood Tells It for some comments on today’s vogue for unreliable flashbacks. And way back in 2006 Matt Zoller Seitz wrote a passionate attack on the idea of “Show, don’t tell” while defending the value of voice-over narration.

N. B. I’m not ignoring the possibility that film can present showing and telling in two simultaneous streams: imagery of the present situation accompanied, perhaps alongside, by continuing imagery of the past scene, as in Suddenly Last Summer. This can be a fruitful option, but it relieves the spectator of the obligation to imagine the past—an important advantage of the pure telling. There’s also the tricky matter of giving the two streams of information enough density. The past event needs to gain enough body to be more than a simple illustration, while the present-time telling could become merely a prop for the flashback. In the dual-presentation mode, the filmmaker risks dividing our attention and thinning the texture of each time frame, with the result that both lose vividness. That seems to me to happen in Suddenly Last Summer.

Psycho.

The ten-plus best films of … 1919

KT here, with some help from DB:

Two entries are enough to create a tradition. Once again, at a time of year when critics are picking their 10-best lists for 2009, we jump back ninety years and give our choices for 1919.

(For our 1917 list, see here, and here for 1918.)

I remarked in last year’s post that it was a bit difficult to come up with ten films, a result perhaps of accidents of preservation or slackening of activity by certain major filmmakers. There was no such problem for 1919, and films had to be bumped off the initial list to keep it to ten. (In fact, you’ll notice we didn’t quite manage to keep it to ten.) Since some people may take these lists as a guide to exploring the cinema of the teens, we’re adding some also-rans at the end, all very much worth watching.

With 1919, we’re approaching the decade when many of the most widely known silent classics were made. Some titles on this year’s list will be very familiar. Erich von Stroheim’s first film came out in 1919, as did Carl Dreyer’s. Ernst Lubitsch, always a prolific director, was particularly busy that year. Other titles are less well-known, still being largely the province of silent-film festivals and archival research.

Three, sadly, are not available on DVD, and some others have to be ordered from sources in their countries of origin. In this day of internet sales around the world, such orders are not difficult. You need, however, a multi-region DVD player.

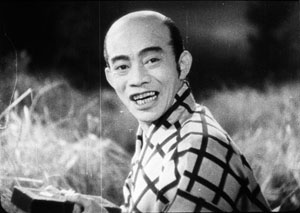

Charles Chaplin had long since left his knockabout comedy behind and was making more controlled, poetic films by  this point. The Little Tramp was beloved around the world, and numerous impersonators were turning out films to cash in on his popularity. Sunnyside is his most highly regarded film of 1919, in large part because of a dream sequence in which the Tramp wakes up by a little bridge to find himself welcomed by a bevy of wispily dressed young ladies. The subsequent open-air dance displays Chaplin’s extraordinary ability to inject humor into such a scene without marring its lyricism. (The only DVD version currently available in the U.S. is a fuzzy copy.)

this point. The Little Tramp was beloved around the world, and numerous impersonators were turning out films to cash in on his popularity. Sunnyside is his most highly regarded film of 1919, in large part because of a dream sequence in which the Tramp wakes up by a little bridge to find himself welcomed by a bevy of wispily dressed young ladies. The subsequent open-air dance displays Chaplin’s extraordinary ability to inject humor into such a scene without marring its lyricism. (The only DVD version currently available in the U.S. is a fuzzy copy.)

Cecil B. De Mille had begun his series of high-society battle-of-the-sexes films by this point. Male and Female differs from the others in that it is based on a prominent literary source, The Admirable Crichton, J. M. Barrie’s successful 1902 play. The plot involved the butler of a wealthy British family. He becomes their leader when the pampered group is cast away on an unpopulated island. A romance develops between the spoiled daughter, Lady Mary (Gloria Swanson), and Crichton (Thomas Meighan).

De Mille spiced up the story with a fantasy scene based on William Ernest Henley’s popular poem of 1888, “I was a King in Babylon.” It dealt with reincarnation, one of several spiritualist fads of the period, which also included psychic contact with the dead and the fairy photographs that deluded Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Crichton refers to the poem, leading into a scene of him as king in a Babylon. When a Christian slave girl rejects his advances, he orders her thrown to the lions. The scene providesa glimpse of the costume-epic style that De Mille would increasingly turn to as his career advanced.

Henley, by the way, is largely forgotten today, but another of his poems, “Invictus,” inspired Nelson Mandela and lends its name to the latest Clint Eastwood film.

D. W. Griffith released an impressive lineup of features in 1919, despite the fact that he was also acting as the producer for other directors. His output includes a charming set of pastoral stories A Romance of Happy Valley, True Heart Susie, and The Greatest Question; a belated war film, The Girl Who Stayed at Home; a Western, Scarlet Days; and a melodrama that ranks among his most admired films, Broken Blossoms. Griffith’s status within the industry was  reflected by the fact that this same year same the formation of United Artists as a company to distribute films by him and the other founders, Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks.

reflected by the fact that this same year same the formation of United Artists as a company to distribute films by him and the other founders, Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and Douglas Fairbanks.

Broken Blossoms owes its simplicity to the fact that Griffith was then making a series of films based on short stories. The title of Thomas Burke’s “The Chink and the Child” sounds offensive today, but it was an ironic reference to the epithet forced upon an idealistic young Chinese man who comes to London’s grim Limehouse district and becomes disillusioned. He falls in love with the delicate Lucy, abused by her violent, drunken father. These three form the main characters. Another Chinese man lusts after Lucy, but for once in Griffith’s work, the sexual threat to the innocent heroine takes second place to her abuse by her father. Lillian Gish and Richard Barthelmess convey the quiet resignation that at intervals gives way to Donald Crisp’s vicious outbursts.

Apart from the strong performances from the three leads, the film was perhaps the first to consistently use the “soft style” of cinematography, an approach that borrowed from a recently established trend in still photography. The hazy views of the Chinese setting in the opening and of the Limehouse docks later on would be enormously influential on films of the 1920s.

Raymond Longford is far and away the least known of the directors in this list. Films were increasingly being made in countries outside the U.S. and Europe, but few have survived. Longford’s The Sentimental Bloke is widely held to be the first major Australian film and perhaps the best of the silent era. Based on a verse poem using vernacular language and serialized from 1909 to 1915, it was set among working-class characters and filmed on location in an inner-city district of Sydney. It follows the reformation of the Bloke, a drinking, gambling man reformed by his love for Doreen. The film’s original intertitles, based on the poem and told in first person by the hero, were too colloquial for Americans to comprehend, and the film failed there, even after a new set of intertitles were substituted.

Raymond Longford is far and away the least known of the directors in this list. Films were increasingly being made in countries outside the U.S. and Europe, but few have survived. Longford’s The Sentimental Bloke is widely held to be the first major Australian film and perhaps the best of the silent era. Based on a verse poem using vernacular language and serialized from 1909 to 1915, it was set among working-class characters and filmed on location in an inner-city district of Sydney. It follows the reformation of the Bloke, a drinking, gambling man reformed by his love for Doreen. The film’s original intertitles, based on the poem and told in first person by the hero, were too colloquial for Americans to comprehend, and the film failed there, even after a new set of intertitles were substituted.

The Sentimental Bloke was restored in 2004 and this past April appeared in a DVD set prepared by the Australian National Film & Sound Archive. A supplementary disc includes historical material, information on the new musical accompaniment, and an interview with Longford. A book of historical essays is also included in the box, which is available directly from the DVD company Madman. (Note that although there is no region coding, it is in the PAL format.)

When I was studying film in graduate school, Ernst Lubitsch’s German period was known mainly for the 1919 historical epic Madame Dubarry. There was little known about the two comedies that came out that year, perhaps the most amusing and delightful of all his German films in this genre: Die Austernprinzessin (“The Oyster Princess,” though seldom called by that title) and Die Puppe (“The Doll,” also a little-used name).

It’s hard to choose which of these three is Lubitsch’s best for the year. Ironically Madame Dubarry isn’t watched much any more, and it’s not on the recent DVD set “Lubitsch in Berlin,” though the two comedies are. Complete prints are rare, due in part to censorship. (If the print you see ends with a close-up of the heroine’s head held up after she is executed, you’ve probably been watching a reasonably complete version.) It may seem a bit stodgy upon first viewing, but I warmed up to it during repeated screenings while researching my book on Lubitsch’s silent films. There are many excellent moments: the extended series of eyeline matches when Louis XV first sees Jeanne, the masterfully timed and staged long take when Choiseul refuses to let Jeanne accompany Louis’s coffin, and a meeting among the revolutionaries that ends as Jeanne reacts in horror to their bloodthirsty plans, backing dramatically into shadow in the background (below).

Given how different these films are, I’m going to declare a tie between Madame Dubarry and one of the comedies. Wonderful though The Oyster Princess is, I’m opting for Die Puppe (above). Its story-book opening and stylization are charming. The hilarious scenes in the doll workshop and the monastery full of greedy monks fill out the plot, making it considerably denser than that of Die Austernprinzessin.

As with Lubitsch, when I was first studying film and for many years thereafter, Swedish director Mauritz Stiller was known mainly for one film, Sir Arne’s Treasure (Herr Arnes Pengar), though an abridged version of The Saga of Gösta Berling also circulated. Sir Arne’s Treasure was assumed to be his masterpiece. The gradual rediscovery and restoration of other Stiller films from the 1910s has considerably broadened our view of him. Perhaps Sir Arne’s Treasure is not the solitary, towering masterpiece it was long thought to be. Still, it holds up well upon revisiting.

It is a period piece set in a small seaside community. A group of foreign men massacre most of a family, in search of their mythical riches. They are forced to remain in the village when the ship in which they are to sail becomes  icebound. The surviving daughter of the family unwittingly falls in love with one of the killers.

icebound. The surviving daughter of the family unwittingly falls in love with one of the killers.

Sir Arne’s Treasure was one of the films which gained the Swedish cinema of the 1910s the reputation for brilliantly exploiting natural landscapes. Few silent films have exploited actual winter settings so well. The actors are clearly working in genuine snow; one can sometimes see their breath fog as they speak. Atmospheric shots show the wind sweeping snow across the ice. Stiller uses the blank backgrounds created by the snow to create stark, simple compositions of dark figures and objects.

Kino’s DVD release uses a print from Svensk Filmindustri’s own archives. To my eye, the tinting used is too dark, especially since much of the action naturally takes place in the dark of the northern winter days. Deep blues somewhat obscure parts of the action. Still, the darkness adds to the brooding tone that pervades the story.

Erich von Stroheim’s first film, Blind Husbands, is the only one he completed that has come down to us in more or less its original version. As the director’s artistic ambitions expanded, his studios’ willingness to accommodate the growing  length and scope of his films diminished. His features of the 1920s were re-edited without his consent, most notoriously when the eight-hour naturalistic film Greed (1924) was released in a version that ran little more than two hours. For many the original remains at the top of the wish list for lost films to be recovered someday. (Number one on my list is Lubitsch’s Kiss Me Again, released in 1925 just before his masterpiece, Lady Windermere’s Fan.)

length and scope of his films diminished. His features of the 1920s were re-edited without his consent, most notoriously when the eight-hour naturalistic film Greed (1924) was released in a version that ran little more than two hours. For many the original remains at the top of the wish list for lost films to be recovered someday. (Number one on my list is Lubitsch’s Kiss Me Again, released in 1925 just before his masterpiece, Lady Windermere’s Fan.)

Blind Husbands is my favorite among von Stroheim’s films. It tells its story of sin and punishment with a lighter touch than his later films would. The director plays a would-be seducer of a neglected wife when the group converges in a village for a mountain-climbing vacation. Von Stroheim’s eye for striking compositions against the snow-clad landscapes and his skillful use of the inn’s hallways and doors to convey the characters’ shifting relationships show an already mature grasp of the art form. (See right, where the villain eyes the heroine in her room but is himself watched by the protective guide in the hallway between the rooms.)

Maurice Tourneur’s Victory runs a mere 63 minutes in its current version, but the original footage count suggests that what we have is substantially complete. That’s somewhat short for a feature by a major director at this point in history, but the simple, intense plot, based on a Joseph Conrad short story, benefits from the compression. The protagonist is a man who has escaped his past and lives as a virtual hermit on a South Seas island. Attracted despite himself, he befriends a young woman playing in a visiting orchestra and rescues her from the abuse of the orchestra’s owner and the lustful advances of the local hotel owner. Returning with the woman to his lonely island, he faces the intrusion of three thugs deceived by the vengeful hotel owner into thinking that the hero has riches hidden on his island.

By this point Tourneur has fully mastered the “rules” of classical continuity style and of three-point lighting. Many of the compositions in Victory look like they could have been made in the 1930s. When I first saw the film about thirty years ago, I found the earliest case of true over-the-shoulder shot/reverse shot that I had ever seen:

Since then, David has found an earlier one that sort of qualifies (maybe more on this in an upcoming entry), but this is a purer case.

Tourneur had also developed a distinctive approach to filming settings in long shot with framing elements within the mise-en-scene and figures silhouetted in the foreground (see top). In general the lighting is superb. Few Hollywood directors had reached this level of sophistication by 1919.

Victory has been released on DVD largely because it features Lon Chaney as one of the thugs. Image offers it paired it with another Chaney film. For some reason the titles are out of focus, but the rest of the film fortunately is in good condition and presents Tourneur’s visual style well.

DB’s picks:

Carl Theodor Dreyer began his film career writing scripts at the powerful Danish studio Nordisk. When he started directing, however, World War I had destroyed Nordisk’s markets, and the American cinema was on the rise. Dreyer’s generation was the first to register the impact of the emerging Hollywood cinema, and he displayed his understanding of Griffithian technique in The President (Praesidenten).

The English title should probably be something like “The Head Magistrate” or “The Presiding Judge,” and the plot appropriately sets up a tension between justice and personal obligation. One of Nordisk’s favored genres was the “nobility film,” in which illicit passion plunges a wealthy man or woman into the lower depths of society. Dreyer gave the studio a nobility film squared, using flashbacks to show how two generations of men in a family have seduced working-class women. The present-day drama displays the crisis that ensues when a respected judge realizes that the woman to be tried for infanticide is his illegitimate daughter. Dreyer’s abiding concern for the exploitation of women under patriarchy begins in his very first film.

From the early 1910s, Danish films displayed a mastery of tableau staging and careful pacing. But The President bears the mark of American technique in its bold close-ups and reliance on editing to build up its scenes. (There are nearly 600 shots in the film, yielding a rate of about 8.8 seconds per shot—quite swift for a European film of the era.) Perhaps more important are Dreyer’s efforts to shove aside the heavy furnishings of bourgeois melodrama. Compare the overstuffed set of Hard-Bought Glitter (Dyrekobt Glimmer, 1911) to this daringly bare one, with its sweep of cameos.

In the late teens, other Danish directors were moving toward simpler settings, but The President carries this tendency to geometrical extremes. Dreyer’s walls, bare or starkly patterned, isolate the players’ gestures and heighten moments of stasis. The result is one of the most adventurously designed film of its time, and if some of its experiments do not quite come off, already we can see that impulse toward abstraction that would be given full rein ten years later in La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc. The all-region DVD from the Danish Film Institute provides a somewhat dark tinted copy with original intertitles and English translations.

Dreyer deeply admired Victor Sjöström, who had already given Swedish cinema some of its enduring masterpieces: Ingeborg Holm (1913), Terje Vigen (1917), The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), and The Outlaw and His Wife (1918). Sjöström would go on to make The Phantom Carriage (1921), The Scarlet Letter (1926), and The Wind (1928). Several other outstanding movies he signed remain little known; worth watching for are The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), Karin Ingmarsdotter (1920), and the deeply moving Mästerman (1920; look for this on our list next year). Among these unofficial classics Sons of Ingmar (Ingmarssönerna, 1919) stands out especially.

Dreyer deeply admired Victor Sjöström, who had already given Swedish cinema some of its enduring masterpieces: Ingeborg Holm (1913), Terje Vigen (1917), The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), and The Outlaw and His Wife (1918). Sjöström would go on to make The Phantom Carriage (1921), The Scarlet Letter (1926), and The Wind (1928). Several other outstanding movies he signed remain little known; worth watching for are The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), Karin Ingmarsdotter (1920), and the deeply moving Mästerman (1920; look for this on our list next year). Among these unofficial classics Sons of Ingmar (Ingmarssönerna, 1919) stands out especially.

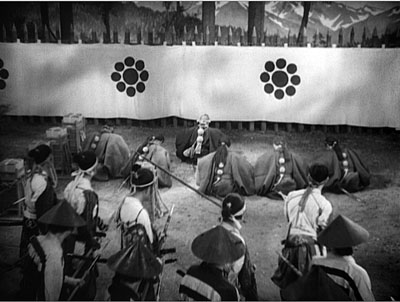

A prologue shows lumbering, somewhat thick-headed Ingmar climbing a ladder to heaven, where generations of Ingmars sit in dignity around a massive meeting-room (see below). There his father tells him that he must find a wife. But Ingmar then explains that he once took a wife, with unhappy results. Some long flashbacks ensue, showing Ingmar forcing a young woman to marry him. The plot takes some doleful turns, with the result that the woman is sent to prison.

Running over two hours (and initially released in two parts), Sons of Ingmar has a fittingly lengthy climax that portrays the pains of reconciliation between a sensitive woman and an inarticulate man. In the film’s final scenes, Sjöström risks a delicate emotional modulation that would daunt a director today. Using Hollywood continuity cutting with a casual assurance, he relies on subtly timed cuts and changes of shot scale to trace the couple’s wavering guilts and hopes. These last scenes have a human-scale gravity that balances the weighty paternal authority of the heavenly sequences. In Theatre to Cinema our colleagues Lea Jacobs and Ben Brewster have written a penetrating analysis of the performances of Sjöström as Ingmar and Harriet Bossa as Brita.

Unhappily, we know of no video version of this wonderful film. It should be a top priority for DVD companies specializing in silent cinema.

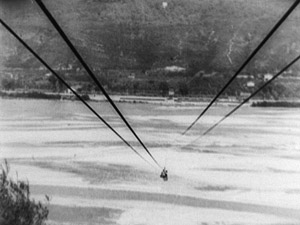

Another 1919 candidate for ambitious DVD purveyors is Louis Feuillade’s great serial Tih Minh. It has been overshadowed by Fantômas (1913-1914), Les Vampires (1915-1916), and Judex (1917), but it has a playful charm of its own. It is, in a way, the anti-Vampires. Instead of chronicling the triumphs of an all-powerful secret society, this six-hour saga gives us a few ill-assorted conspirators who inevitably fail at every scheme they try. The plot is no less far-fetched than that of the earlier serial, but the twists are more comic than thrilling. (Which is not to say that we’re denied some astonishing real-time stunt work performed by the actors, as above.) The film’s genial tone assures us that nothing bad will happen to the poor girl Tih Minh, but the villains will get enjoyably harsh punishment. In the course of the adventure three couples are formed, the routines of provincial life are filled in with leisurely detail, and the whole thing ends with a big wedding.

Unlike the Paris-bound serials, Tih Minh allowed Feuillade to apply his elegant staging skills to natural landscapes. By now he was filming in Nice, and the chases and fistfights are enhanced by gorgeous mountains, vistas of water, and hairpin roads. More than one connoisseur has confessed to me that this is their favorite Feuillade serial, and it’s hard to disagree. I always find that viewers are carried away by its zestful tale of good people who come to a good end.

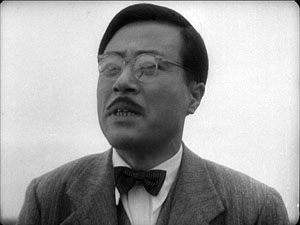

DB’s runner-ups: Perhaps not as fine as the above, but definitely of bizarre interest, are two Robert Reinert films from 1919. The title of Opium pretty much sums up this fevered movie. It includes sinister Asians, drug-addled doctors, a lions’ den, and Conrad Veidt in a suicide-haunted performance that makes his Cesare role in Caligari look underplayed (see right). Later in the same year Reinert gave us an even more overwrought tale, Nerven. This is a movie about collapse–the collapse of a community, of a business, and of the tormented minds of buttoned-up citizens. Reinert renders melodrama in images of controlled frenzy unlike any others I know from the period. Had his films been as widely seen as the official Expressionist classics, I think he would be much admired today. I analyze these two movies in Poetics of Cinema, and say a bit about them in this entry. A DVD of Nerven is available from the Munich Film Archive.

DB’s runner-ups: Perhaps not as fine as the above, but definitely of bizarre interest, are two Robert Reinert films from 1919. The title of Opium pretty much sums up this fevered movie. It includes sinister Asians, drug-addled doctors, a lions’ den, and Conrad Veidt in a suicide-haunted performance that makes his Cesare role in Caligari look underplayed (see right). Later in the same year Reinert gave us an even more overwrought tale, Nerven. This is a movie about collapse–the collapse of a community, of a business, and of the tormented minds of buttoned-up citizens. Reinert renders melodrama in images of controlled frenzy unlike any others I know from the period. Had his films been as widely seen as the official Expressionist classics, I think he would be much admired today. I analyze these two movies in Poetics of Cinema, and say a bit about them in this entry. A DVD of Nerven is available from the Munich Film Archive.

KT’s runners-up: I suppose that there will be some tongue-clicking over the fact that Abel Gance’s J’accuse! is not present in our list. There’s no doubt it’s historically important and influential, but it’s also heavy-handed and doesn’t add the leavening of humor to its melodrama, as some of the above films do. But it does deserve a mention in an overview of 1919. (I’ve posted about what I see as Gance’s limitations here.)

Last year I put Marshall Neilan’s Mary Pickford vehicle, Stella Maris, in the top ten. I’d be tempted to do the same with his (and her) Daddy-Long-Legs, but this year there’s a lot more competition. But it’s a charming film, and the great cinematographer Charles Rosher provides another series of beautiful images using the new three-point lighting system. It was the first Pickford film into Germany after the war and considerably influenced Lubitsch and other German directors.

Similarly, in a year with fewer major films, Victor Fleming’s When the Clouds Roll By, a wacky, inventive tale of superstition and psychological manipulation starring Douglas Fairbanks, would make the main list. David illustrated some of that inventiveness in his epic entry on Fairbanks.

Within a few years, compiling our 90-year picks will become increasingly difficult. Experimental cinema will blossom, as will animation. The Soviet Montage and German Expressionist movements will get started, and French Impressionism, still a minor trend in the late teens, will expand. Filmmakers like Murnau, Lang, Vidor, and Borzage will gain a higher profile, and more films by veteran directors like Ford will survive. Maybe we’ll have to expand the annual list even further. . . .

A very happy New Year to all our readers! Assuming we make it through the security lines, we shall be celebrating New Year’s Eve on a plane bound for Paris, where David will be doing a lecture series over the first few weeks of January. Paris is the world capital of cinema, at least as far as the diversity of films on offer goes, so we shall no doubt find occasion to blog while there.

Sons of Ingmar.

Kurosawa’s early spring

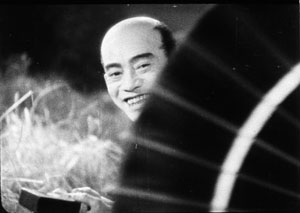

The Most Beautiful (1944).

For Donald Richie

DB here:

Cinephile communities aren’t free of peer pressure. Sometimes you must choose or be thought a waffler. In postwar France, the debate within the Cahiers du cinéma camp often came down to big dualities. Ford or Wyler? German Lang or American Lang? British Hitchcock or American Hitchcock? In the America of the 1960s and 1970s, we had our own forced choices, most notably Chaplin or Keaton?

This maneuver assumed that a simple pair of alternatives could profile your entire range of tastes. If you liked Chaplin, you probably favored sentiment, extroverted performance, and direction that was straightforward (“theatrical,” even crude). If you liked Keaton, you favored athleticism, the subordination of figure to landscape, cool detachment, and geometrically elegant compositions. One director risked bathos, the other coldness. The question wasn’t framed neutrally. My generation prided itself on having “discovered” the enigmatic Keaton, in the process demoting that self-congratulatory Tramp. Keaton never begged for our love.

Of course it was unfair. The forced duality ignored other important figures—Harold Lloyd most notably—and it asked for an unnatural rectitude of taste. Surely, a sensible soul would say, one can admire both, or all. But we weren’t sensible souls. Drawing up lists, defining in-groups and out-groups, expressing disdain for those who could not see: it was all a game cinephiles played, and it put personal taste squarely at the center of film conversation.

In the 1950s another big duality slipped into Paris-influenced film talk. Virtually nobody knew about Ozu, Shimizu, Gosho, Naruse, Shimazu, Yamanaka, et al., so two filmmakers had to stand in for the whole of Japanese cinema. Mizoguchi or Kurosawa?

A problematic auteur

For Cahiers the choice was clear. Mizoguchi was master of subtly shaping drama through the body’s relation to space, thanks to quiet depth compositions and modulations of the long take. In Japan, land of exquisite nuance, the dream of infinitely expressive mise-en-scene seemed to have come true.

There seemed to be nothing nuanced about Kurosawa, whose brash technique, overripe performances, and propulsive stories seemed disconcertingly “Western.” Sold, like Satyajit Ray, as a humanist from an exotic culture, he played into critics’ eternal admiration for significance. This director wanted to make profound statements about the bomb (I Live in Fear), the relativity of truth (Rashomon), the impersonality of modern society (Ikiru), and the complacency of power (High and Low, The Bad Sleep Well). Even his swordplay movies seemed moralizing, with the last line of Seven Samurai (“The victory belongs to these peasants. Not to us.”) summoning up a cheer for the little people. Kurosawa could thus be assigned to Sarris’s category of Strained Seriousness. “He’s the Japanese Huston,” said a friend at the time.

But there was no overlooking his cinematic gusto. He made “movie movies.” He flaunted deep-focus compositions, cunningly choppy editing, sinuous tracking shots (through forests, no less), dappled lighting, and abrupt addresses to the viewer, by a voice-over narrator or even a character in the story. He exploited long lenses and multiple-camera shooting at a period when such techniques were very rare, and he may have been the first director to use slow-motion for action scenes. Bergman, Fellini, and other international festival filmmakers of the 1950s didn’t display such delight in telling a story visually. If you liked this side of his work, you overlooked the weak philosophy. On the other hand, if you found the style too aggressive, it could seem mere calculation on the part of a man with something Important to say.

The case for the defense was made harder by the fact that he was a controversial figure at home as well. Japanese critics I met over the years expressed puzzlement about Western admiration for the director’s style. I was once on a panel in which an esteemed critic blamed Kurosawa for influencing Western directors like Leone and Peckinpah. His violence and showy slow-motion had helped turn modern cinema into a blunt spectacle. No wonder Lucas, Spielberg, Coppola, and Walter Hill have loved this macho filmmaker.

Today passions seem to have cooled, but I should confess that my own tastes remain rooted in my salad days (1960s-1970s). I could live happily on a desert island with only the films of Ozu and Mizoguchi. I’d argue forever that Japanese cinema of the 1920s through the 1960s is rivaled for sheer excellence only by the parallel output of the US and France. (For more on this matter, see my blog entry on Shimizu.) On Kurosawa, however, my feelings are mixed. I still find most of his official classics overbearing, and the last films seem to me flabby exercises. But there are remarkable moments in every movie. Overall, I’ve responded best to his swordplay adventures; Seven Samurai was the first film that showed me the power of the Asian action aesthetic. I think as well that his earliest work up through No Regrets for Our Youth (1946), along with the later High and Low and Red Beard, are extraordinary films. And, like Hitchcock and Welles, he is wonderfully teachable.

We don’t live on desert islands, and gradually we’re gaining easy access to the range of Japanese filmmaking of its great era. We can start to see beyond the fortified battlements set up by generations of critics. With so many points of entry into Japanese cinema, mighty opposites lose their starkness; polarities dissolve into the long tail. Nevertheless, personal tastes take you only so far, and objectively Kurosawa still looms large. Whatever your preferences, it’s important to study his place in film history and film art.

Gauging that place involves thinking outside some traditional conceptions of how films work. Like most ambitious Japanese directors, Kurosawa provides bursts of cinematic swagger. This six-shot passage from Rashomon revels in its own strangeness.

Here traditional over-the-shoulder shots submit to a brazen geometry. Out of an ABC film-school technique Kurosawa creates a cascade of visual rhymes and staccato swiveled glances. Yes, an ingenious critic could thematize this bravura passage. (“The symmetries put the central characters, each of whom asserts a different version of what happened, on the same visual and moral plane.”) Instead I’m inclined to think that the shots constitute a little thrust of “pure cinema,” a brusque cadenza that keeps our eyes, if not our hearts or minds, locked to the screen. From this angle, Kurosawa claims some attention as an inventor of, or at least tinkerer with, the disjunctive possibilities of film form.

His centenary arrives in 2010, and the occasion is celebrated by Criterion with a set of twenty-five DVDs. Most of these titles have already been available singly, and the discs lack all the bonus features we have come to admire from the company. Yet the crimson and jet-black box, the discreet rainbow array of slip cases, and the subtly varied design of the menus add up to a good object, like the latest iPod—something you want even if it means re-buying things you already have. There’s also a handsome picture book with notes by Stephen Prince on each film.

To viewers who need the assurance of cultural importance, this behemoth announces: You must know Kurosawa to be filmically literate. And that’s more or less true. Just as important, the inclusion of four rarities from his early years gives the collection a claim on every film enthusiast’s attention. One hopes that those titles will eventually appear separately, perhaps in an Eclipse edition. [See 15 May 2010 update at the end.] For now these copies of the wartime features are far better than the imports I’ve seen.

The Big Box makes it tempting to mount a career retrospective on this site, but that’s far beyond my capacity. Future blog entries may talk more of this complicated filmmaker, but for now I’ll confine my remarks to these early works. They offer plenty for us to enjoy.

Audacious propaganda

Although Kurosawa was only seven years younger than Ozu, he belongs to a distinctly different generation. Ozu directed his first film in 1927, at the ripe age of twenty-four. He grew up with the silent cinema and made masterful films in the early 1930s, during the long twilight of Japanese silent filmmaking. Kurosawa became an assistant director in the late 1930s. Although he evidently directed large stretches of Yamamoto Kajiro’s Horse (1941), he didn’t sign a feature as director until he was thirty-three. His closest contemporary, and a director whom some Japanese critics consider his superior, is Kinoshita Keisuke. Kinoshita was born in 1912 and his first feature, The Blossoming Port, was released in the same year as Kurosawa’s debut.

Kurosawa and Kinoshita began their careers making wartime propaganda. Their task was to display Japanese self-sacrifice and spiritual purity in stories of both the past and the present. In the Sanshiro Sugata films (1943, 1945), Kurosawa presents judo as an integral part of Japanese tradition and a path to enlightenment. Much of the external conflict is devoted to uniting martial arts (ju-jitsu, karate) under the rubric of the less aggressive but more powerful judo, and to showing how it can defeat American-style boxing. But the internal dimension is also important. Judo is a means of tempering character and accepting one’s proper place. Humble, unflagging devotion to one’s vocation becomes heroic.

The same quality can be found in The Most Beautiful (1944), a story of teenage girls working in a factory manufacturing lenses for binoculars and gunsights. Vignettes from the girls’ lives dramatize the need for cooperation and sacrifice, even as wartime demands for output threaten the girls’ health.

A more detached conception of the Japanese spirit underlies The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail (1945). This adaptation of a plot from Noh and Kabuki theatre shows officers escorting a general through enemy territory. Disguised as monks, the bodyguards are forced to bluff their way through a checkpoint. The situation is one of hieratic suspense, made more tonally complex by Kurosawa’s addition of the movie comedian Enoken. Enoken plays a dimwitted porter reacting to the charade played out by his betters. By dramatizing one of the most famous episodes in Japanese literature, Kurosawa was reasserting the tradition of devotion to duty and honor. The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail was released the same month that the atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima.

During earlier decades, Japanese cinema had created a complex tradition. In part, it conducted a sustained dialogue with Western cinema. Tokyo had access to a wide range of Hollywood movies, and directors studied American technique closely. Just as Ozu would not be Ozu without his early fondness for Lubitsch and Harold Lloyd, Mizoguchi learned a good deal from von Sternberg. Between 1938 and 1942, alongside German imports Tokyo theatres screened Fury, Only Angels Have Wings, The Sea Hawk, The Awful Truth, Angels with Dirty Faces, Boys Town, Young Tom Edison, Only Angels Have Wings, and many French titles. In 1942, with Hollywood films now banned, one could still see René Clair’s Le Million and À Nous la liberté—films that had been circulating in Japan since the early 1930s and could have served as models of flashy sound technique. It’s misleading to talk of Ozu as “purely Japanese” and Kurosawa as “Western”: All Japanese directors of the 1920s and 1930s were deeply acquainted with Western cinema, and American cinema in particular furnished a foundation for most local filmmaking.

Yet there are crucial differences. Japanese cinema welcomed extremes of stylistic experimentation that would have been rare in Western cinema. The 1920s swordplay films (chambara) pioneered rapid editing, handheld camerawork, and abstract pictorial design. (I supply some examples here.) Directors working in the contemporary-life mode (the gendai-geki) experimented similarly, often achieving remarkable visual effects and bold stylization. Mizoguchi and Ozu have become our emblems of this creative rigor and richness, but they are the peaks of what was a collective approach to filmic expression. Not every film was an experiment—indeed, most behave like Hollywood or European productions—but many ordinary movies, signed by unheralded directors, exhibit flashes of unpredictable imagination. This was the tradition of permanent innovation that directors of the Kurosawa-Kinoshita generation inherited.

As the war dragged on, however, Japanese studio productions lost much of their audacity. Production fell from over 400 films in 1939 to fewer than 100 in 1943. Censorship may have made filmmakers cautious about style as well as subject and theme. Most of the fifty-plus films I’ve been able to see from the period 1940-1945 are quite conservative aesthetically. Several of these seem to me quite good, but they rely on fairly standard Hollywood technique sprinkled with touches that had become markers of Japanese cinema (sustaining scenes in rather distant shots, using cuts rather than dissolves to shift scenes, and so on). Swordplay films become more severe and monumental. Even Mizoguchi’s Genroku Chushingura (1941-42) and Ozu’s There Was a Father (1942), superb as they are, are more elevated in tone than the directors’ earlier works.

Against this backdrop, Kurosawa’s films stand out; they are the most extroverted works I know in this period. Their innovations remain vivid; Sanshiro Sugata, for one, with its hierarchy of competitors, its rivalry among schools, and its visceral technique, may have invented the modern martial arts film. But we should also realize that these early films build upon the traditions already firmly established in Japanese cinema.

Playing with the passing moment

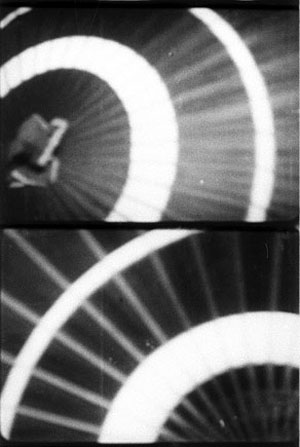

Consider transitions. Kurosawa is famous for his elaborate links between sequences, from the hard-edged wipes to swift imagistic associations. But we should recall that transitional passages offer moments of flashy style in American and European cinema of the 1920s and 1930s, and indeed right up to this day. (For examples, go here and here.) In the same year as Sanshiro, Kinoshita gave us this moment in Blossoming Port. A con artist is trying to bilk money from a town. He bows, leaving an empty frame.

Without a discernible cut, heads pop into the empty frame, rocking to and fro.

Another cut reveals that the people we see are in a boat tossing on the waves, and the conman’s partner is enjoying an outing with the locals. Kurosawa’s scene-changes—sites of what Stephen Prince has called “formal excess”—can be seen as prolonged, imaginative reworkings of this tricky-transition convention.

Japanese filmmakers were more willing to play with the expressive and “decorative” side of filmmaking than most of their Western peers. Directors created not only flashy transitions but moments of stylistic playfulness within scenes. Sometimes this just adds to the overall tone of comedy, as in this pretty passage in Heiroku’s Dream Story, another 1943 release. The hero, played by Enoken, is squatting and talking to a charming girl (Takamine Hideko). She twirls her parasol between them, and we get a straight-on cut that creates a moment of abstraction as the parasol glides across the frame in contrary directions. (The vertical pair of frames shows the cut.)

This decorative symmetry would be rare in Hollywood outside a Busby Berkeley number, but it enlivens the characters’ exchange in a way similar to the more dramatic Rashomon sequence. To borrow a phrase that Kepler applied to nature’s way with snowflakes, a filmmaker may seek to ornament a scene by “playing with the passing moment.”

Likewise, in The Blossoming Port, as an older woman recalls a romance of her youth, the natural sound fades out and the back-projection behind the carriage shifts from the seaside to urban imagery of the period she’s remembering.

The frank artifice of this shot shows that Japanese filmmakers were eager to let us enjoy the forms with which they were working.

A similar explicitness about style can be seen in one of Kurosawa’s signature devices, the axial cut. This technique shifts the framings toward or away from the subject along the lens axis. If the shots are short enough, we sense a bump at the abrupt change of shot scale.

Kurosawa often uses this cutting to stress a momentary gesture or to prolong a moment of stasis. But it can structure a simple dialogue scene as well. In Sanshiro Sugata, the hero’s first conversation with Sayo takes place as they descend a stair toward a gateway. Kurosawa uses axial cuts to keep up with them as they move away from us down the steps. Illustrated with stills, this technique looks like a forward camera movement, but in fact these images come from separate shots.

The crux of the scene is Sayo’s revelation that the man Sanshiro must fight is her father, and instead of big close-ups to underscore his reaction, Kurosawa simply lets his hero halt while Sayo continues down the steps. The steady pattern of cut-ins to the characters’ backs makes Sayo’s sudden turn to the camera more vivid, and Sanshiro’s reaction is underplayed by not giving us direct access to his face.

An earlier entry traces theaxial cut back to silent film, when its jolting possibilities were exploited in Soviet montage cinema. Japanese directors also used the device often. Yamanaka Sadao, one of the most-praised directors of the 1930s, used axial cuts prominently in an early dialogue scene of Humanity and Paper Balloons (1937). The cuts are accentuated by low-height compositions that maintain the steep perspective of the street.

The technique gains more punch in Japanese swordplay films. Here is a percussive instance from Faithful Servant Naosuke (1939), four short shots yanking us inward in a way that Kurosawa would make his own.

Tom Paulus reminds me that Capra films sometimes make use of this technique, as in this string of concentration cuts from Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939).

Interestingly, Mr. Smith ran on several Tokyo screens in October 1941; it may have been the last Hollywood feature to receive theatrical distribution before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

To say that Kurosawa adapts traditional devices doesn’t take away from his accomplishment. No artist starts from zero, and in commercial cinema, filmmakers commonly revise schemas already in circulation. So Kurosawa puts his own spin on the axial cut, not only by using it frequently, but also by varying it in the course of a film. Sanshiro Sugata 2 makes the axial shot-change a sort of internal norm, but then varies it: inward or outward, cuts or dissolves, how great a variation of scale? When Sanshiro leaves Sayo, the three phases of his departure are marked by simple repetition: each time he halts and looks back, she responds by bowing.

Like the Rashomon sequence, this shows Kurosawa’s fondness for permuting simple patterns. But there’s an expressive payoff too. The framings that make Sayo dwindle to a speck give the axial cuts the forlorn, lingering quality we usually associate with dissolves. In addition, for viewers who know Sanshiro 1, the scene calls to mind the staircase passage we’ve already seen. Their first extended encounter is paralleled by their last one.

Axial cuts are easier to handle when the subject is unmoving, or moving straight toward or away from the camera. What about other vectors of motion? In The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail, as the general’s bodyguards file out of the compound, they pass a line of soldiers in the foreground. Kurosawa combines concentration cuts with lateral cutting, so our men stalk leftward through the frame once, then again, then again, each time both closer to us and further along the row of soldiers.

Kurosawa revises other traditional techniques. You can find moments of extended stasis in swordplay films of earlier decades, and the technique surely owes something to the prolonged mie poses in Kabuki. But Kurosawa’s early films turn long pauses into living freeze-frames. Instead of using an optical effect, he simply asks his actors not to move! One combat in Sanshiro shows the audience caught in absolute stillness, staring at the result of Sanshiro’s throw. In Sanshiro 2, our hero and the boxer stand like statues in the prizefight ring until the American collapses. And in The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail, the groups gathered at the checkpoint are absolutely unmoving for nearly fifty seconds as Benkei leads them in prayer.

This shot’s tactful, reverential composition echoes a fairly standard image for showing loyal retainers; here’s an example from a 1910s version of Chushingura.

In sum, I think that for his “manly movies” Kurosawa sifted through the Japanese film tradition and pulled out the most vigorous techniques he could find, all the while recognizing that rapid pacing needs the foil of extreme immobility. He compiled a digest of many arresting visual schemas available to him, and then pushed them in fresh directions. He realized as well that he could apply this sharp-edged style to genres dealing with modern life.

A most stubborn young woman

Although we think of Kurosawa as a “masculine” director, two of his finest films center on women. The Most Beautiful and No Regrets for Our Youth can be thought of as propaganda, but this label shouldn’t put us off. Propaganda works partly because it taps deep-seated emotions, and I’d argue that the formulaic nature of a “social command” can allow filmmakers a chance at emotional and formal richness. Because the message can be taken for granted or read off the surface, an ambitious director can go to town—nuancing the presentation, complicating its implications, taking the clichéd message as an occasion for pushing formal experiment. (Which is one aspect of what the Soviet montage filmmakers did.)

The Most Beautiful, probably the best movie ever made about child labor, starts off as a doctrinaire effort. Before even the Toho logo fades in, a title declares: “Attack and Destroy the Enemy.” The first fifteen minutes are filled with pledges to help the war effort, work to meet an emergency quota, obey orders, display filial devotion, build noble character, and think constantly of how making flawless lenses saves soldiers’ lives. The rest of the movie focuses on the pain of doing all this. This story of patriotic affirmation is steeped in tears.