Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

A welcome INFLUENZA

DB here:

Kristin and I are en route to the Vancouver International Film Festival, after a few days in Seattle visiting Sanjeev and Megan, nephew and niece-in-law. We were completely awestruck by the vast holdings of Scarecrow Video, where even the Warner Archives special-order DVDs can be rented. We also had a good long talk over JaK steaks with Jim Emerson, impresario of the superb website Scanners. Not to mention catching a screening of the lively Walt & El Grupo at the Seattle International Film Festival theatre. As a big fan of Saludos Amigos and Three Caballeros, I was thrilled to learn the background story, as well as to watch gorgeous 16mm Kodachrome footage.

Last year’s trip to Vancouver put us on the road for thirteen days, encountering movie-related stuff (and Obama) in surprising places. This time we took the plane—faster but less relaxing. To get a better look at the landscape, we’ll be taking a train up to Vancouver.

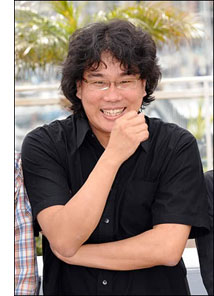

One of the films I’m most looking forward to at Vancouver is Bong Joon-ho’s Mother, brought to this year’s event by Tony Rayns. Alas, Bong himself will not be joining us. I enjoyed meeting him at my first Vancouver visit in 2006, when this blog was in swaddling clothes. He’s completely frank and unpretentious.

One of the films I’m most looking forward to at Vancouver is Bong Joon-ho’s Mother, brought to this year’s event by Tony Rayns. Alas, Bong himself will not be joining us. I enjoyed meeting him at my first Vancouver visit in 2006, when this blog was in swaddling clothes. He’s completely frank and unpretentious.

Even before meeting him, I had followed Bong’s career with keen interest. I think he’s one of the best Korean directors, though he probably doesn’t get as much attention as some others. Like the Japanese Kore-eda Hirokazu, Bong is the sort of quiet genre-hopper who’s hard to pin down. His first feature, Barking Dogs Never Bite, is a charming romantic comedy that also offers a portrait of neighborhood life. The mordant Memories of Murder (2003) quietly bends the conventions of the city-cop-in-a-village movie, mixing comedy into a serial-killer tale. Bong’s biggest commercial success came with The Host (2006), a monster movie in the grand tradition that manages to be at once scary, funny, and socially critical. Seeing it again this summer, I was struck by its compact elegance. Bong makes complex narrative and stylistic twists look easy.

Bong has also made some acute short films; he seems to understand that they require the snappy impact of a well-wrought short story. Probably his best-known short is the “Shaking Tokyo” segment of the omnibus movie Tokyo (2008). It focuses on a hikikomori, a young man who has withdrawn from social contact and lives wholly through the TV monitor and the computer screen. Bong’s hero tidily stacks empty pizza boxes along his walls like installation art. Only an encounter with a delivery woman makes him question his robotic seclusion. The ending, which lures our hero outside, provides a Twilight-Zoneish twist.

More single-minded, though, is a short I’ve just seen, the little-known Influenza (2004). There are several movies based on surveillance-camera footage; one of the most lyrical, Optical Vacuum, I reviewed here. Bong went instead for narrative. He staged a story in locales covered by surveillance cameras, and then retrieved the footage from the hours of material. Cut together, the shots follow Mr. Cho, a failed salesman who turns to petty theft and violent crime.

We discover Mr. Cho in men’s rooms, car parks, and ATM stations. The scenes, each shot in a single take, run through various spycam techniques: fixed high angle, black and white imagery, stuttering motion, mechanical scanning of the scene (sometimes leaving the main action behind). We see wide-angles, telephoto shots, barely legible long-shots, and split-screen imagery picking out opposite points of view.

Everything we see is staged, I think. Unrehearsed events seldom look this cogent and poised. Yet sometimes, especially during the climactic crowd scene, some of the action seems to have been left to luck.

Short but not sweet—mostly sour—Influenza shows what an ingenious filmmaker can do by setting himself a single, precise problem. Crossing the border between commercial fiction and avant-garde experimentation, the film deserves wider circulation.

As for Mother, Derek Elley’s Variety review promises the trademark Bong blend of gentle comedy and unsettling drama. And Vancouverites have an extra bit of luck: A program of shorts by Bong and his colleagues from the Korean Academy of Film Arts graces the festival this year. Bong’s next planned project, about the wretched survivors of a new Ice Age, shows him to be as unpredictable and unclassifiable as ever.

Thanks to Bong Joon-ho for his help in preparing this entry. The trailer for Walt & El Grupo is here. And there’s a poignant story of the founding and near-demise of Scarecrow Video here.

The Host.

(50) Days of summer (movies), Part 2

DB here:

How I spent part of my summer vacation: notes on three more films.

Gangbusters

Two major directors–one an emblem of goofy bravado, the other emerging as a contemporary master–gave us movies this summer, and both let me down. I have cautiously championed Tony Scott’s recent work because at least he’s willing to go all the way, however misguided the direction. From Spy Games on, he has stuck to the credo that too much is never enough. His technique is swaggering and undisciplined, mannered to the nth degree. Yet I find his fevered visuals more genuinely arresting than the safe noodlings of most of today’s mainstream cinema. Man on Fire and Déja Vu reheat their genre leftovers into something spicy, if not nourishing, while Domino, the cinematic equivalent of hophead graffiti, wraps its sleazy characters in a visual design apparently inspired by the glowing interior of a peepshow booth.

So it’s with a chagrin that I report that The Taking of Pelham 123 is utterly square. The violence isn’t reveled in, the color scheme isn’t garish, the story has a florid villain played by scenery-masticating Travolta, and Denzel Washington has never seemed more passive and drab. In Scott’s DVD commentaries, he insists that art-school training led him to approach cinema with a painterly eye. But this project has the feel of a commissioned magazine illustration, not the delirious wall-size outrage that he could make if given his head.

I’ve respected Michael Mann since I saw Thief on its initial run. Heat seems to me on the whole his best work, though I admire many qualities of Manhunter, The Last of the Mohicans, The Insider, and Collateral. Ali and Miami Vice seem to me lesser achievements, and with Public Enemies he has gone somewhere I can’t follow.

I found it a surprisingly flat exercise, skimming over familiar territory–the charming bandit vs. the square-jawed cop, the struggle of the freebooter vs. the mob, the cynical politics of law enforcement vs. the authentic impulses of the outlaw. The plot is unusually straightforward for Mann, and the last shot, which ought to be a corker, is wasted. Too many scenes are nakedly expository, relying on fussy period detail to carry them. At the same time, more basic exposition seemed to me botched at the outset. In the opening scene, shouldn’t we get a clearer sense of what Dillinger’s sidekicks look and act like? A classically constructed film would dwell on them, characterize them, give them bits of behavior that develop in the course of the film. Mann treats them as part of the scenery setting off his handsome hero. Later, when one of Dillinger’s hired pistoleros goes kill-crazy, shouldn’t we have been set up to see him as a possible risk?

Typically Mann romanticizes, even sentimentalizes, his hard cases in that tough-guy way we know from fiction. But I couldn’t discern any vivid attitude toward his parallel protagonists Dillinger and Purvis. After Heat, where crook and cop both show a willingness to abandon women who want them, it’s probably significant that Dillinger is characterized by his fidelity to Billie. Yet while she’s in jail he’s back to an insouciant night on the town with his familiar floozies. In all, I can’t figure out why Mann made this movie about these people, or why we should care.

Collateral was already veering toward a certain obviousness of construction, when Vincent talks initially about how in impersonal L. A. a dead guy can ride the subway without anyone noticing. In Public Enemies the final line returns to the film’s most underscored motif in a distressingly on-the-nose way. Similarly, one thing I admire about Heat is that it acts as if no other gangster movie has ever been made. Its scenes offer plenty of opportunities for cute citations of old crime movies, especially when Vincent (a different Vincent) catches his wife’s lover watching TV. Instead, Mann treats the material as cut off from cinema, and this saves him from the coyness of so much genre work today.

Is he then a realist? His interviews and DVD commentaries indicate that he thinks of himself this way. Yet he strikes me instead as a genre purist. Each film is sui generis because it aims to recover the authentic dramatic core of the policier, the social comment film, or the wilderness adventure. But in Public Enemies, Dillinger’s visit to the movie house to watch Manhattan Melodrama (1934), even though the event is historically accurate, hits the parallel chords hard. Dillinger, who’s about to be cut down in a few moments, smiles in fascination when Gable says: “Die the way you lived–all of a sudden.” In such scenes, Mann seems to me to have retreated into being a more ordinary filmmaker. The worst thing I can say about Public Enemies is that it risks becoming academic.

Mann’s claims to realism are partly his efforts to deny being a self-conscious stylist. For many of his admirers, me included, his pictorial sense is a large part of what makes his work distinctive. There’s plenty of controversy about the look of Public Enemies, and I have to come down on the side of the nay-sayers. I saw it twice, once in 2K digital projection in a superb multiplex in Europe. My second viewing was on 35mm, in a reliable Madison, Wisconsin venue. The digital version too often teemed with artifacts, blown-out bright areas, and disconcerting shifts in tonal values within scenes. The next two images are successive shots in the HD trailer, and I haven’t adjusted them. The disparities between them reflect the sort of mismatches that struck me in the digital screening.

On film, the faces lost the edge enhancement and the mushy textures I saw in the digital version, and the tommygun fire was less tinged with yellow, pink, and orange. On the whole, I thought that the images benefited from the mercies of emulsion.

The chance to take high-definition video all the way, especially in low-light situations, seems to have invigorated Mann creatively, but it may have distracted him from basic craft. Investing wholly in a new look, he belabors even the simplest action through staccato cutting; getting people in and out of cars should not take such effort. Action scenes occasionally succumb to the jittery camera. I consider the climactic bank robbery in Heat somewhat awkwardly staged (though the dazzling sound work there compensates somewhat), and similar short-cuts can be found in the Wisconsin shootout here.

If you find my tone tentative, you’re right. I didn’t care for The Insider on first viewing; it took me a second visit to grasp what I now take as its virtues. That’s why I saw Public Enemies twice. I expect as well that Mann’s eloquent defenders, such as Matt Zoller Seitz, who has done a passionate series of shorts on Mann, will find fault with my evaluation. For the film’s admirers, what I find sketchily indicated they could see as daringly elliptical; what I see as inconsistent they might consider calculatedly ambiguous. The incompatibilities of color and light could be part of Mann’s experimentation too. I see his oeuvre as largely updating cinematic classicism, while others tend to see it as a daring leap beyond it. Maybe I’ll come around eventually. For now, I have to consider Public Enemies the biggest disappointment of my fifty days.

A welcome basterdization

It’s a measure of the changes wrought by the Internets that Inglourious Basterds has in about a month amassed a daunting volume of serious commentary. Without benefit of DVD (let’s be charitable and assume no BitTorrenting), dozens of online writers have dug deep into this movie. As if to demonstrate the virtues of crowdsourcing, this flurry of critical discussion has shown that most professional movie reviewers have tired ideas, know little about film history, and are constrained by the physical format and looming deadlines of print publication. At this point, I’m very glad I’m not writing a book on Tarantino; the sort of secondary sources that normally take years to accrete have piled up in a few weeks, and the pile can only grow bigger, faster.

So what is there left for me to say? A little, though I can’t be sure every point isn’t made somewhere else. In any case, surely you’ve seen it, so I don’t have to warn you about spoilers, do I?

Since I thought Death Proof offered merely proof of the director’s creative death, I went to Inglourious Basterds with low expectations. I came out thinking that it was the most audacious and ambitious American movie I saw in my fifty days of summer viewing.

To deal with the current controversy immediately: I didn’t think its counter-history was intrinsically offensive or immoral, since I remembered those what-if-Germany-had-won counterfactuals in Deighton’s novel SS-GB and Brownlow’s film It Happened Here (1966). Did those express defeatism or an inability to counter the Nazi threat? So why not have a band of vindictive Jews seeking to match the Nazis in ruthlessness (except that their targets, so far as we see, are only soldiers and collaborationists)? We call it fiction.

You can quarrel about whether a revenge plot should carry some signals of the cost to the avenger, but I’m sufficiently convinced that tit-for-tat is embedded in human nature and will always be perceived, however recklessly, as virtuous. In any case, the movie’s emblem of revenge, the powerful image of Shosanna laughing mockingly as she goes up in flames along with the audience, carries the strategic ambiguity of a lot of cunning popular art. It’s at once a glorying in payback, a Jeanne d’Arc martyrdom, and a reminder of the fate of Jews elsewhere at that moment. It doesn’t permit a single easy reading.

Granted, there are some low-jinks, like the misspelled title and heroine’s name; are these jokes on Tarantino’s notorious spelling malfunctions? Yet the movie seemed to me Tarantino’s most mature (to use a term of praise that he hates) since Jackie Brown. I say that not because his other work is juvenile, which it’s not (except for Death Proof). I call Inglourious Basterds mature because it exploits his strengths in fresh but recognizable ways.

First, strengths of structure. Tarantino’s conception of storytelling owes at least as much to popular literature, particularly policiers, as it does to current conventions of screenwriting.

Take his penchant for repeating scenes from different viewpoints. In Elmore Leonard’s novel Get Shorty, Chapter 2 ends with Harry, seeing Chili at his desk, exclaiming, “Jesus Christ!” Chapter 3 consists of the first stretch of their conversation. Chapter 4 starts with Karen approaching Harry’s office and hearing him say, “Jesus Christ!” This overlapping-scene strategy, sketched in Reservoir Dogs, gets elaborated in Pulp Fiction and Jackie Brown.

Likewise, thrillers and crime novels commonly play on showing how distant lines of action unexpectedly intersect. In Peter Abrahams’ Hard Rain the agent who becomes the hero tells the story of two coal miners, Bazak and Vaclav, who meet after tunneling from two ends of the field. Needless to say, Hard Rain’s own plot enacts the same pattern. Charles Willeford’s chance-driven, parallel-action novel Sideswipe could be a model for the structure of Pulp Fiction. So it should be no surprise that Inglourious Basterds, labeling its long sequences “chapters,” should rely on the stepwise convergence of Shosanna’s plotline and the Basterds’ guerrilla operations, with the UK Operation Kino serving as the first sign of a merger.

So the film is built on large-scale alternation of the principal forces: Shosanna (Chapter 1), the Basterds (2), Shosanna again (3), the Basterds again (4), and finally the two strands knotting at the screening of National Pride (5). Landa also knits the two strands together, of course, starting when he investigates the tavern shootout at the end of (4). In Chapter 5 the alternation gets carried by classic crosscutting. We shift to and fro among Shosanna’s plot, the capture of Raine and Utivich, the conflagration in the auditorium, and the deal struck between Landa and the US command. Yet right to the end both Shosanna and the Basterds have no awareness of each other’s plan: only we grasp the double dose of Jewish vengeance. More than in most films, but typical for Tarantino, we’re aware of the plot’s abstract architecture.

Then there are strengths of texture—the moment-by-moment unfolding of the action. Again pulp fiction offers some models.

In Get Shorty, Leonard develops the scene I mentioned above in an extraordinary way. Chili, Harry, and Karen talk through the night about Chili’s purpose and about the ways of the movie industry. Their conversation runs for a remarkable seven chapters and sixty pages, interrupted only by a brief flashback. When I met Leonard at a book-signing event, I asked him why he took up a fifth of the novel with a single scene. He said that he hadn’t realized it consumed so much space, because it was “fun to write.”

Tarantino can lay bare his chapter-block architecture because his scenes are devoted to this sort of prolongation. You may remember the bursts of violence, but what he fashions most lovingly is buildup. Here the spirit of Leone hovers over our director. In each entry of the Dollars trilogy, you can see the rituals of the Western getting more and more stretched out, filled with microscopic gestures and eye-flicks. Eastwood’s lips stick slightly together and must peel apart when he speaks: This becomes a major event. I’m a primary-document witness to the fact that 1969 cinephiles were stunned by the long opening scene of Once Upon a Time in the West, which after painstakingly establishing the tics of several characters ends by eliminating them. Later, John Woo gained fame by dwelling on Homeric preparations for combat and endlessly extended bouts of gunplay. From these masters Tarantino evidently learned the power of the slow crescendo and the sustained aria.

Leone and Woo’s amped-up passages rely chiefly on imagery and music. Tarantino is no slouch in either department, but he relies, like his beloved pulp writers, on talk. As everyone has noticed, the conversations in Basterds go on a very long time. In an era when scenes are supposed to run two to three minutes on average, Tarantino has only a couple this brief. The introduction at LaPadite’s farm runs over eighteen minutes, by my count, and the more complicated Chapter 2, with intercut flashbacks and flash-forwards, runs about the same length. Thereafter scenes last anywhere between four and twenty-four minutes, and Chapter 5’s crosscut climax consumes a stunning thirty-seven minutes. All but the last depend completely on dialogue. Leonard would probably consider them to have been fun to write.

Talk in Tarantino comes in two main varieties: banter and intimidation. At the coffee shop the Reservoir Dogs squabble and soliloquize; later exchanges will be conducted at gunpoint. En route to the preppies’ apartment, Jules and Vincent chat casually; when they arrive, the talk turns threatening. If Death Proof lets banter dominate, Inglourious Basterds goes to the other extreme. Here talk is a struggle between the powerful and the powerless.

As Jim Emerson points out, nearly every scene is an interrogation. This entails that someone in authority (Landa, Aldo, Hitler, the Germans who question Archie’s accent in the tavern, Zoller) is trying to pry information out of someone else. Intimidation through interrogation gives every scene an urgent shape. Now Tarantino’s digressions (three daughters, rats and squirrels, a card game, the correct pronunciation of Italian) don’t read as self-indulgence, but rather as feints in a confidence game. Here Tarantino’s tendency to write endless scenes, something he confesses in his recent Creative Screenwriting interview on the film, is fully harnessed to more classic, albeit unusually extended, scene structure.

To keep us focused on the lines and the actors delivering them, Tarantino has adopted a classical approach to style. He shoots with a single camera, so every composition is calculated. “I’m not Mr. Coverage,” he remarked in 1994, “. . . . I shoot one thing specifically and that’s all I get.” He foreswears handheld grab-and-go. In Basterds he locks his camera down, or puts it on a dolly or crane. Cinematographer Robert Richardson says that there is only one Steadicam shot in the film.

We don’t usually call Tarantino tactful, but his technique can be surprisingly discreet. He has the confidence to let key dialogue play offscreen: in the café when Landa arrives at Goebbels’ lunch, we stay fastened on Shosanna, a good old Hitchcockian ploy that ratchets up the tenson. Although Tarantino cuts rapidly throughout each chapter (on average every 5.6 seconds), he repeats setups quite a bit. This permits a simple change of angle or scale to mark a beat or shift the drama to a new level.

He can bury details on the fringes of the shot, as when the cut to the tight close-up of LaPadite shows him tossing his match into an ashtray sitting beside Landa’s cap, which bears the insignia of a skull and crossbones. It’s out of focus and on the edge of the screen, but the glimpse of it increases our fear that LaPadite is indeed harboring a Jewish family. As in Jackie Brown, another film that extends its scenes through detailing of performance, lighting, and setting, there seems no doubt that Tarantino, for all his PoMo reputation, appreciates some traditional Hollywood virtues.

He can inflect them, however. Richardson finds that Tarantino has an unusual approach to the anamorphic format.

I naturally move [the framing of characters] to one side or the other, especially when shooting anamorphic, whereas Quentin enjoys dead-center framing. For singles in particular, we’re just cutting dead-center framing from one side to the other, with the actors looking just past the barrel of the lens.

I noticed this tendency most in the reverse angles. Tarantino’s two-shots tend to be simple and symmetrical, shooting the characters in profile, as in the image surmounting this entry. But in over-the-shoulder shots, about half the frame is unoccupied—as if Tarantino were compensating, like his 1970s mentors, for an eventual TV pan-and-scan version of the scene.

Or take the cliché of arcing the camera around a group of chatting people, picking up one after the other. Tarantino didn’t invent this, but the opening scene of Reservoir Dogs probably helped popularize it. In Chapter 5 he uses the technique in the lobby of the Le Gamaar cinema, only to break its momentum by having the camera trail Landa when he breaks out of the circle and retreats, in a paroxysm of giggles, after Bridget says she broke her leg while mountain climbing.

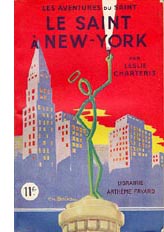

There are many other intriguing touches, like the mixed typography of the opening credits, all of which seem to use fonts derived from 1970s paperback novels. Or the reference to The Saint in New York, perhaps less important for its plot parallels than for the fact that author Leslie Charteris’ later Saint novel, Prelude to War (1938), was banned in Germany and Italy for its attacks on fascism (even warning about the camps). So is reading a Saint novel a covert act of defiance on Shosanna’s part? Later, she applies make-up in fierce strokes, like an American Indian, reminding us that Raine’s Basterds model their tactics on the Apache.

There are many other intriguing touches, like the mixed typography of the opening credits, all of which seem to use fonts derived from 1970s paperback novels. Or the reference to The Saint in New York, perhaps less important for its plot parallels than for the fact that author Leslie Charteris’ later Saint novel, Prelude to War (1938), was banned in Germany and Italy for its attacks on fascism (even warning about the camps). So is reading a Saint novel a covert act of defiance on Shosanna’s part? Later, she applies make-up in fierce strokes, like an American Indian, reminding us that Raine’s Basterds model their tactics on the Apache.

Perhaps most striking is the dairy motif, from the glass of milk in Chapter 1 to Landa’s ordering a glass for Shosanna in Chapter 3. Is this a hint that he suspects her of being the girl who fled the massacre? Or is it a test he offers to any French national he meets? In the restaurant scene, the extreme close-ups of the crème fraiche may underscore the possibility that Landa is looking for signs that she won’t eat dairy products not prepared according to Orthodox dietary rules. Few filmmakers today would trust audiences to imagine this possibility on their own; instead we’d get an explanation to an underling. (“So here’s a quick way to find out if we have a Jew ….”)

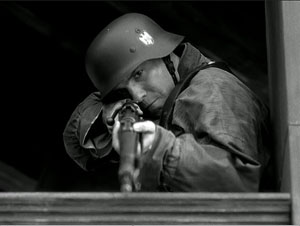

Another nest of details involves the film-within-the-film, Nation’s Pride. Many online critics have noticed that it provides the sort of film that Basterds refuses to be: We never see our squad in the sort of Merrill’s Marauders skirmishes we probably expected going in. What I find intriguing about the movie, purportedly directed by Eli Roth, is that despite some anachronisms it exemplifies the sort of confrontational cinema we find in the silent Soviet pictures. Surprisingly, this was a tradition that Goebbels admired. Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, he claimed, “was so well made that it could make a Bolshevist out of anyone without a firm philosophical footing.” So in Nation’s Pride Roth and Tarantino have provided a Nazified homage to Eisenstein: a baby carriage rolls away from a mother, a soldier suffers an assault to the eye reminiscent of the wounding of the schoolteacher on the Odessa Steps, and even Soviet-style axial cut-ins are used for kinetic impact.

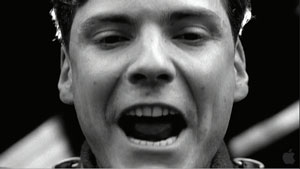

This pastiche of agitprop culminates in the sort of to-camera address we find in Dovzhenko. Zoller shouts, “Who wants to send a message to Germany?” But this is followed by Shosanna’s spliced-in close-up addressing the audience in her theatre.

She makes her own confrontational cinema.

Several years ago the film theorist Noël Carroll speculated that the Movie Brats of the 1970s sought to create a shared culture of media savvy that would replace the traditional culture based on religion, classical mythology, and official history. For the baby boomers, knowledge of the Christian Bible and iconography of American history would be replaced by deep familiarity with movies, pop music, and TV. This secular sacred would bind the audience in a new set of traditions. On this path, Scorsese, Spielberg, and Lucas didn’t go as far as Tarantino has. In his films every situation or character name or line of dialogue feels like a citation, a link in a web of pop-culture associations. (Aldo Raine = Aldo Ray = Bruce Willis, whom Tarantino once compared to Aldo Ray.) The only other filmmaker I know who has achieved this supersaturated cross-referencing is Godard, another exponent of the vivid-moments model (though he uses it to create a more fragmentary whole). Tarantino is the most visible evidence of what Carroll called “The future of allusion.”

But it’s too limiting to see Tarantino’s films as merely anthologies of references. I think he wants more.

Many viewers seem to assume that Tarantino’s film is somewhat cold. The Basterds are grotesques, parodies of men on a mission; Shosanna, though in a sympathetic position, must maintain a frosty demeanor. Even revenge, so central to films that Tarantino admires, is served frigid here, a purely formal postulate, like the urge for vengeance animating classic kung-fu films.

There is cinema that asks you to empathize with its characters. Then there is cinema that aims to thrill you with a cascade of vivid moments. There is How Green Was My Valley (1941) and Citizen Kane (1941). I think that Tarantino’s films mostly tilt to the vivid-moment pole, seeking to win us through their immediate verve, the way film noir and the musical and the action movie often do. The young man arrested by great bits from blaxploitation and biker movies sees cinema not as merely piling up cinephiliac references—though that’s surely part of it—but as a flow of tingle-inducing gestures, turns of phrase, shot changes, musical entrances. There can be pure pleasure in having time to see how actors move, or savor their lines, or simply fill up physical space by being centered in the anamorphic frame. Our fascination with Landa comes, I suspect, from the spectacle of a man who is utterly enjoying himself every second.

We might be tempted to claim that this effort to create what Jim Emerson calls “movie-movie moments” actually breaks the film’s overall unity. But Tarantino keeps nearly everything in check by the architectural clarity of his plot. The carving of the swastika on Landa’s brow sets you squirming, but it reveals itself as the culmination of a process we have seen piecemeal up to now. It’s the last in a string of firecracker bursts that have kept the film humming along.

So I’m not convinced that Inglourious Basterds lacks emotion. The emotions Tarantino aims for will arise not from character “identification” but from the overall structure and texture of the work. We are to be stirred, enraptured, astonished by a procession of splendors big and small. It’s the tradition (again) of Eisenstein, particularly in the Ivan films, but also of Leone and, in another register, Greenaway. Formal virtuosity isn’t necessarily soulless; it can yield aesthetic rapture.

The most sophisticated analyses and interpretations I’ve found online are led off by the indefatigable Jim Emerson (start here to track his many entries on the subject), along with his knowedgeable readers, who furnished a book’s worth of commentary and critique. Jim provides links to many other writers’ work (here, for example), not all of which I’ve been able to absorb. For exhaustive, not to say exhausting, coverage of things Tarantino, visit The Archives.

On Tarantino’s time-shuffling and its relation to crime fiction, see my Way Hollywood Tells It, 90-91. In Chapter 7 of Film Art Kristin and I provide an analysis of the replayed scene in Jackie Brown. Tarantino’s comments on writing the Basterds script are in Jeff Goldsmith’s article, “Glorious,” in Creative Screenwriting 16, 4 (July/ August 2009), 20-29. His comments on coverage come from Gavin Smith, “When You Know You’re in Good Hands,” in Quentin Tarantino Interviews, ed. Gerry Peary (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1998), 102. In the same interview he has illuminating comments on the role of the axis of action. Robert Richardson discusses filming Basterds in Benjamin Bergery, “A Nazi’s Worst Nightmare,” American Cinematographer 90, 9 (September 2009); the quotation here is from p. 47. This feature is available online here.

Goebbels’ remark on Battleship Potemkin is quoted in Klaus Kreimeier, The UFA Story: A History of Germany’s Greatest Film Company, trans. Robert and Rita Kimber (New York: Hill and Wang, 1996), 207. For background on Goebbels’ agenda for German cinema, summed up by Lt. Archie Hicox, see Eric Rentschler, The Ministry of Illusion: Nazi Cinema and Its Afterlife (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996). I talk about axial cutting in Eisenstein and other Soviet directors at various points in The Cinema of Eisenstein.

Noël Carroll’s comments about popular entertainment as a secular alternative to shared religious culture are in his essay, “The Future of Allusion: Hollywood in the Seventies (and Beyond),” in Interpreting the Moving Image (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 244, 261-63. On the idea of an emotionally arousing cinema that doesn’t rely on attachment to character psychology, see my Cinema of Eisenstein.

PS 20 Sept 2009: Curt Purcell, at The Groovy Age of Horror, finds a similar plot architecture emerging in the comic-book series Blackest Night.

(50) Days of summer (movies), Part 1

Ponyo on a Cliff by the Sea.

DB here:

Travel took me out of Madison for half of June and nearly all of July. While overseas, I saw only one recent US release. So I caught the American Summer Movies in two gulps–over a couple of weeks early on and over the last month or so. In all, exactly 50 days? Well, were there exactly 50 first dates in that movie?

Herewith, comments on a batch of titles. There are spoilers sprinkled throughout, but most of what I say won’t harm your encounter with the film. Because all my remarks amounted to an even longer blog than usual, I’ve broken it into two parts. The next installment, coming up in a few days, talks about The Taking of Pelham 123, Public Enemies, and Inglourious Basterds.

My summer movies were bracketed by two animated pictures. Up is to my mind the most mature Pixar film yet. It has all the virtues we associate with this studio: quick but not frantic pacing, expert handling of resonant motifs, technical brilliance (especially in its depiction of settings), and one-off gags. The poker-playing dogs had me laughing out loud. But as we’ve argued in other blogs (here and here and here), the Pixar team likes to set itself tough challenges. First there is the technical challenge of 3-D, which is easily surmounted. The 3-D effects get more pronounced once the plot lands in South America. More important, I think, is the challenge of representing the emotion of sorrow.

Another movie would have organized its plot around the kid, Russell, and let him meet the elderly Carl in the course of his adventures. That way, Carl would emerge as a merely touching secondary character. But by focusing point of view around Carl’s life, showing his marriage and widowhood, Pete Docter and his team have tackled one of the hardest problems of classic moviemaking. How do you render pure sentiment without becoming sentimental?

The protagonist’s portrait is surprisingly hard-edged. Carl is tightly wound even in his youth, unlike the exuberant and extroverted Ellie. Yet the couple seems to have no friends throughout their marriage, and it becomes easy to see how Carl could will himself into crabby isolation after her death. Thanks to the choice of viewpoint, Carl becomes no mere crank but a truly empathetic figure.

This is fragile stuff, and Docter handles it with tact. Many movies want you to cry at the end, but Up daringly invites you to indulge in its first ten minutes. It then spends the rest of its running time brightening your mood, so that the title could describe the film’s emotional trajectory. It’s one of my two favorite new movies I saw this summer.

Just a few days ago Kristin and I saw Ponyo on a Cliff by the Sea. We’ve been Miyazaki fans since Totoro, and have especially admired Kiki’s Delivery Service and Spirited Away. As with this last and with Howl’s Moving Castle, I have a hard time figuring out the premises of the plot. What rules govern Ponyo’s transformations? Why can’t she become a real girl, exactly? And then why is she permitted to? The well-timed interventions of her mother, like the Witch’s change of heart in Howl, seems a way out of plot difficulties, and as often happens in Miyazaki the plot resolution seems rushed in comparison with the leisurely development of characters’ relationships.

But as usual I was won over by the effortless virtuosity of the imagery and the weird conviction suffusing Miyazaki’s concept of nature. As in Spirited Away, animation becomes animistic. The sea is bursting with hidden forces: goldfish with extraordinary powers of group effort, waves that turn into blue fish, and bubbles as solid and slippery as balloons. Nobody but Miyazaki could imagine the quasi-Wagnerian scale of Ponyo’s race, atop gigantic fish-waves, to catch up with Sosuke and his mother fleeing in their car.

These shots burst with more dynamic shifts of mass and scale than I’ve felt in any official 3-D picture.

Sometimes Nature is scary. Although nothing here is as traumatic as Spirited Away‘s transformation of parents into swine, the tsunami scenes induce genuine awe at nature’s exuberant destructiveness. There follows a reassuring calm. Ponyo and Sosuke glide along the flood waters while ancient creatures zigzag in the depths, and the townspeople quietly accept that their homes have been engulfed. Ponyo is a gentle movie, aimed (as Miyazaki explains here) at a younger audience than was his recent work. It’s suffused with simple human affection, seen in acts of spontaneous generosity. What American movie could include a moment when Ponyo, fish become girl, offers a nursing mother a sandwich to help her make milk for her baby? Again, sentiment without sentimentality. Ponyo offers more evidence that whatever the disappointments we may find in live-action movies, we are living in a golden age of animation.

Am I just being perverse in finding Transformers 2: Revenge of the Fallen not as abysmal as others have? Don’t get me wrong. It is not what you’d call good. It is rushed and overblown. What other movie accompanies its opening company logos with gnashing sound effects? Its plot is even more preposterous than the first one’s. Its performers bear that sheen of meretriciousness that fills nearly every Michael Bay project. It is also lazy in its plotting. Worse, I couldn’t really make out the design of the ‘bots. It’s not that the cutting is abnormally swift (a mere 3.0 seconds ASL, about the same as in Up and slower than that in The Hurt Locker). The problem is that the digital camera is swirling around the damn things so fast as they take shape that you can’t get a fix on what they actually look like. All those spinning wheels and dangling carburetors ought to be worth a glance.

But still….For non-Transformers shots Michael Bay at least puts his camera on a tripod, which these days counts as a plus with me. And a minibot humps the heroine’s leg. And John Turturro is in it. Would he grace a movie that signals the fall of Western Civilization?

In a similar vein but more satisfying was District 9. Its “racial subtext” is as perfunctory and confused as such weighty hidden meanings usually are, and anyhow whatever political points the movie wants to make drift out of view halfway through. Moreover, its “documentary immediacy” is inconsistent: despite footage marked as coming from surveillance and TV cameras, we have unimpeded access to all plot matters. But here the Bumpicam probably allows for cheaper CGI, and as a run-around-shooting-things movie, it needs to keep things simple.

In a similar vein but more satisfying was District 9. Its “racial subtext” is as perfunctory and confused as such weighty hidden meanings usually are, and anyhow whatever political points the movie wants to make drift out of view halfway through. Moreover, its “documentary immediacy” is inconsistent: despite footage marked as coming from surveillance and TV cameras, we have unimpeded access to all plot matters. But here the Bumpicam probably allows for cheaper CGI, and as a run-around-shooting-things movie, it needs to keep things simple.

I found the smash-and-grab look far more distracting in The Hurt Locker. Kathryn Bigelow has directed several first-rate movies, notably Near Dark (where she used a tripod), Blue Steel (ditto), and Point Break (tripod mostly). On this project, she seemed to me to be doing more conventional work. There are the titles telling us that time is running out (“16 Days Left”). There’s classic redundancy of characterization, as when we’re told that James is a hot dogger–“He’s reckless!” “You’re a wild man!”–as we watch him be all that he can be, and more. There’s the hapless kid who is so near to the end of his tour that you know he’s a marked man. There are even aching slow-mo replays of explosions bowling guys to the camera. What if war films gave up this convention and just showed bombs going off and bodies hurled around as fast as in reality? Might war look a little less picturesque?

The camera is locked down for these iconic slow-mo shots, but most of the scenes are handled in heat-seeking pans, artful misframings, chopped-off zooms, and would-be snapfocusing that can’t find something to fasten on. The editing plucks out bits of local color and sprinkles in some glimpses of onlookers that tend to turn them into props. I’ve tried to show elsewhere that this trend in rough-hewn technique nonetheless adheres to the conventions of classical style: establishing/ reestablishing shots, eyelines, reactions, and close-ups to underscore story points. Even wavering rack-focus can still orient us to the action quite clearly.

The question is what the harsher surface adds, especially when it’s so pervasive. Habituation is one of the best-proven phenomena in psychology, and movies like this seem to prove that it works. After the first few minutes, we’ve adapted to any visceral punch that the Unsteadicam hopes to provide. Maybe it serves to ratchet up suspense? Doubtful. A director would have to be a real duffer to dissipate suspense in a movie about dismantling an explosive device. The trick is to do something different, as in bomb-disposal movies like the Chinese Old Fish and the British Small Back Room.

Still, the plot is decently engaging, and there’s a taut, unpredictable siege in the desert. That long sequence displays a disciplined interplay of optical viewpoints, a sense of constantly revised tactics, a new aspect of James’s leadership style, and nice details about sharing juice boxes. In another era, The Hurt Locker would have been a studio picture in the vein of Anthony Mann’s bleak Men in War. I suppose it shows that yesterday’s genre film, executed with conviction and a certain edginess, can become today’s art movie.

Speaking of suspense: I thought that the setup to A Perfect Getaway was reasonably engrossing. There was some clever self-referential teasing: our hero’s a screenwriter, and there’s talk of a “second-act twist.” And it was mostly shot on a tripod. I hoped that director-writer David Twohy would have the courage to stick with its initial premise and be Deliverance in Hawaii. But sure enough, the things that smelled like red herrings were red herrings, and the reversal that you feared comes to pass in one of those point-of-view switcheroos that movies now indulge in. Come to think of it, that was the second-act twist. But I did like the strategically placed telemarketer call.

We’re evidently allotted one crossover indie movie per summer, a fact acknowledged in the title of this year’s hit. (500) Days of Summer, which really needs its parentheses not just because everybody now overuses them (there’s even a blog confessing it), but because its strategy is to disarm you with its knowing cuteness. It is so self-consciously winning your teeth will ache. It’s a twentysomething romance of the sort usually called “bittersweet.” The guy’s after love and the girl withholds commitment. Guaranteed result: emotional roller coastering, because we’ve seen her flighty sort before in kooky-girl figures like Petulia. There’s a fantasy musical number with a touch of animation, an avuncular narrating voice sliding in and out, a shuffled time scheme sorted out for us with a sort of daily odometer reading, and pop-culture references including retro ones to The Graduate and Ringo Starr. Everybody smiles a lot, and when they’re not smiling they’re crinkling up their faces.

(500) Days plays by the book. Tom and Summer work for a greeting-card company, a satiric target only a little harder to hit than the Pentagon. As in the movies mentioned above, the cutting is intent on making sure we see everybody deliver every syllable. (What ever happened to offscreen dialogue? Did TV kill it?) (Sorry about the parentheses.) The four-part script layout is as neat as embroidery: the first kiss at the photocopiers comes at 24:00, the splitup comes at 47:00, Tom delivers his diatribe against the lies about love at about 72:00, and the epilogue, with its fatal final line, finishes at 90:00. Yet I’m not curmudgeon enough to despise a movie so desperate to be liked, and at last I found a film whose narration clicks along in syncopation with my little tally counter.

The real indie film I admired in my fifty days was Ramin Bahrani’s Goodbye Solo, or Good Bye Solo as the credit title has it. Kristin and I have registered our admiration for Bahrani’s films here and here on this site, and his latest is no less modest, well-crafted, and affecting. A Senegalese emigre cab driver befriends an enigmatic old man who at the start of the film offers him $1000 to pick him up on October 20 and drive him to Blowing Rock Mountain. Solo infers that William is planning a suicide and so starts to intervene in his life. His involvement with William gets intertwined with his family problems and his hopes of becoming an airline attendant.

Goodbye Solo exemplifies the “character-driven” movie. Solo is sunny, quick-witted, and socially adroit; his audition for the airline managers shows him as an ideal employee. William is just the opposite–morose, aggrieved, profoundly unhappy. The treatment is observational, with lengthy shots (an average of over twelve seconds) capturing dialogue and slowly shifting character response.

The characters change, but Bahrani and his co-screenwriter Bahareh Azimi, wary of quick fixes, don’t push this too far. It would be easy to make William soften more, even eventually make him likeable, and to keep Solo an indefatigable force for optimism. Instead, if William accepts more of Solo’s ministrations, it’s largely due to his passivity, not a fundamental change of heart. Meanwhile, Solo becomes more anxious and pessimistic, shedding some of that casual charm that captivated us in the opening. Neither executes that neat character arc that Hollywood tends to favor and that’s visible in Up and (500) Days of Summer.

The characters change, but Bahrani and his co-screenwriter Bahareh Azimi, wary of quick fixes, don’t push this too far. It would be easy to make William soften more, even eventually make him likeable, and to keep Solo an indefatigable force for optimism. Instead, if William accepts more of Solo’s ministrations, it’s largely due to his passivity, not a fundamental change of heart. Meanwhile, Solo becomes more anxious and pessimistic, shedding some of that casual charm that captivated us in the opening. Neither executes that neat character arc that Hollywood tends to favor and that’s visible in Up and (500) Days of Summer.

Bahrani’s hatred of cliché obliges him to make his story events mundane and equivocal. As in Man Push Cart and Chop Shop, the plot emerges from variations in routine, a lesson well-taught by European festival cinema of the 1950s. But when you have a stubborn, taciturn character like William, and you’re restricted to another character’s range of knowledge, it’s hard to give the film a forward propulsion. You have a deadline, but no momentum. So plot dynamics arise from Solo’s relation to his wife and daughter, his career goals, and above all his investigation of William’s past–his search for what could drive the man to suicide. And this investigation turns on conveniently discovered clues.

Someday I must do a blog entry on tokens in narratives. Any plot of some complexity seems to need physical objects that encapsulate dramatic forces, spread out information, or become emotion-laden motifs. The photograph is probably the most traditional one, but notes, diaries, rings, and so on are useful too. In Goodbye Solo, William’s tokens move the drama of disclosure forward, and it’s possible to object to the film’s reliance on so many of them.

The problem Bahrani faces is that the film has to give us personal information about William while retaining tact and respect for characters’ integrity. For William to open up into a Tarantino-style confession would tear the movie apart; even a quiet moment of sobbing vulnerability is too indiscreet here. The film needs its tokens, however awkward they may seem as narrative devices, to keep faith with its people.

Staying a little outside the characters, allowing them to retain some private motives, is exactly what (500) Days of Summer doesn’t attempt. Bahrani’s discretion extends to the very last scene. The title becomes a line that someone should speak but doesn’t. Up till now, the quietly precise images have been shot by a camera locked down, but atop a mountain the camera leaves its tripod and supplies some mildly shaky imagery. And now it fits. It’s not just that the drama has reached an emotional pitch. The camera is simply buffeted by the wind. Once more Bahrani lets his world do its work.

You can read about our summer film-related travel here and here and here and here and here.

Overwhelmed by all the material on Pixar and Up, I merely point to two encyclopedic experts: the ever independent-minded Mike Barrier and the always-informative Bill Desowitz, who offers information on Pixar’s approach to 3-D here. For Ponyo background and an interview with Miyazaki, turn again to Bill D, here; he provides a transcript of a conversation between Miyazaki and John Lasseter here. A fat book of Miyazaki interviews and essays has just been published, and it includes some incendiary stuff, such as “Everything that Mr. Tezuka [Osamu, the ‘god of animation’] talked about or emphasized was wrong” (197).

The parentheses in (500) Days of Summer are explained by screenwriter Scott Neustadter at Jeff Goldsmith’s Creative Writing podcast.

Roger Ebert has reviewed nearly all these films and as always he has sensitive things to say, particularly on Goodbye Solo. He’s been championing Bahrani’s films for many years and he offers a warm career appreciation here.

Goodbye Solo.

Now leaving from platform 1

From a Facebook post by Tahereh

To all my friends:

What can I reply to Hossein? He’s pursuing me so avidly, but you know he isnt really a prime catch. No education, no house. If it werent for the earthquake, I wouldnt give him a second look. But he does interest me a little—he’s made me lose track of my lines so many times!

Oh no, now he’s chasing me across the field. What can I tell him? BRB!

DB here:

Many people in the film industry hold media studies in disdain, and often the feeling is mutual. Filmmakers recoil from the abstrusities of Big Theory, and academics often consider filmmakers gearheads (just before wagging their fingers and warning us about the Intentional Fallacy). But scholars like Rick Altman, John Caldwell, Janet Staiger, Kristin, and me, and younger folks like Patrick Keating and Ben Wright have been trying to study filmmakers’ creative choices in concrete ways. Some of us even ask filmmakers what they were trying to do.

So it’s heartening to see movement in the other direction. For quite a while academically trained filmmakers like James Schamus and Todd Haynes have brought ideas from their university studies into their films. Recently Reid Rosefelt composed an enlightening blog entry on Kathryn Bigelow’s intellectual side. Now some terms and ideas are being spread even more widely across the industry.

For example, in a recent Entertainment Weekly story about why women viewers like horror, we read:

One of the most consistent tropes of the genre is the character whom filmmakers call ”the final girl” — the survivor.

Actually, it was Carol Clover, scholar of horror movies and Scandinavian epics, who came up with the “final girl” nickname in her book Men, Women, and Chainsaws. Going back to the EW sentence, you notice that academics helped popularize the term genre too, which you seldom find in Hollywood’s patter before the 1970s. And the very word trope smells of classrooms and chalkdust.

Even more striking is a recent Variety article entitled, “Transmedia Storytelling Is Future of Biz.” Peter Caranicas explains that it involves “developing a piece of intellectual property across multiple media platforms.” The Star Wars franchise is the major modern instance, as Caranicas explains.

What Lucas did went several steps beyond old-style character licensing and brand extensions. He created a unified body of work with an extensive backstory and mythology, and he determinedly guarded its canon [another academic term—DB] while simultaneously opening up peripheral parts of his universe to exploration by other contributors.

One of my former students assures me that Kristin and I used the term “transmedia” back in the 1990s, but we have no memory of doing so. More relevantly, Liz Rosenthal reminds us that Peter Greenaway was pushing the concept in 1993. “If the cinema intends to survive, it has to make a pact and a relationship with concepts of interactivity and it has to see itself as only part of a multimedia cultural adventure.”

In any case, the person who brought the concept of transmedia storytelling to the forefront of media studies, and thus industry parlance, was another Wisconsin student, Henry Jenkins. Henry has made the concept part of his broader research into how modern media connect with audiences, particularly fan audiences. In his 1992 essay on Twin Peaks, he was already exploring how fans used the still-emerging internet to respond to a range of ancillary texts around Lynch’s TV series. You can get a quick acquaintance with his most recent ideas in this 2007 blog essay. For me, his argument emerged most vividly in a talk he gave at Madison some years ago. The lecture became the chapter “Searching for the Origami Unicorn” in his book Convergence Culture. For his more recent thinking, you can check his current course syllabus, which includes reading and web references, in the 11 August entry here.

The platform-shifting that Caranicas describes is planned and executed at the creative end, moving the story world calculatedly across media. These, dubbed by Jenkins “commercial extensions,” differ from “grassroots extensions,” which are created by audience members without the permission, or even the knowledge, of the creators. The commercial extensions are what I’ll be considering here.

From aggregator Movie MMORPG:

Welcome to a sophisticated world teetering on the edge of decadence. Get hammered on Italian cocktails. Fight your way out of a hospital jammed with nymphos. Cheat on your wife. Seduce a married man. Wander through the streets and stare at gushing water. Have you got what it takes to survive a day in LaNotteCity? You’ll get hooked, since the endgame is always inconclusive!

As it’s currently discussed, transmedia storytelling has two uncontroversial components and one rare but intriguing one.

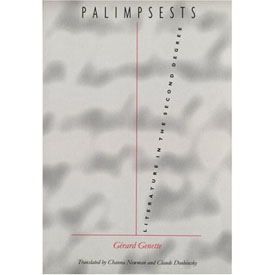

First, the term implies that a story is spread among a series of discrete “texts.” This “hypernarrative” idea was explored with taxonomic zeal by Gérard Genette in his 1982 book Palimpsests. His taxonomy of storytelling is worth considering a little here because he anticipated several possibilities we’re seeing now. Many of his categories have parallels in cinema, but I’ll stick to his domain, literature.

First, the term implies that a story is spread among a series of discrete “texts.” This “hypernarrative” idea was explored with taxonomic zeal by Gérard Genette in his 1982 book Palimpsests. His taxonomy of storytelling is worth considering a little here because he anticipated several possibilities we’re seeing now. Many of his categories have parallels in cinema, but I’ll stick to his domain, literature.

Novels and short stories feed off other novels and short stories. Obvious examples are parodies, pastiches, sequels, and continuations (sequels not written by the original author). Genette also considers what he calls the “transposition,” a very roomy category that’s of particular interest to us.

Transpositions are things like translations, rewritings, and literary adaptations, as when a novel becomes a play. A transposition also occurs when the original text is pruned or compressed, as in abridged versions of Don Quixote or Moby-Dick. At the other quantitative extreme is what Genette calls augmentation. Here, the derivative work expands the original, either in style (three sentences replace one) or narrative material (extra scenes or plots).

Yet another sort of transposition occurs when the story events in the original are rendered through alternative literary techniques. Charles Lamb retells Ulysses’ adventures in a different order than Homer does, and someone could rewrite the events of Madame Bovary in first person, from Charles’ point of view. When Genette was writing, he had to reach for some esoteric examples, but nowadays we have others. Alice Randall’s The Wind Done Gone (2001) retells Gone with the Wind from the point of view of a slave on Tara. The novel Wicked is a large-scale example, as is Tom Stoppard’s Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead.

All these examples of hypernarrative operate within a single medium. The second condition of transmedia storytelling is, of course, that it crosses media. Genette considers drama and written literature to be all part of the same medium, but if you don’t, then novels turned into plays, like Les Miserables, would count as transfers across media.

In this sense, transmedia storytelling is very, very old. The Bible, the Homeric epics, the Bhagvad-gita, and many other classic stories have been rendered in plays and the visual arts across centuries. There are paintings portraying episodes in mythology and Shakespeare plays. More recently, film, radio, and television have created their own versions of literary or dramatic or operatic works. The whole area of what we now call adaptation is a matter of stories passed among media.

What makes this traditional idea sexy? I think it’s a third, less common component that Henry has spotlighted. Some transmedia narratives create a more complex overall experience than that provided by any text alone. This can be accomplished by spreading characters and plot twists among the different texts. If you haven’t tracked the story world on different platforms, you have an imperfect grasp of it.

I can follow Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories well without seeing The Seven Percent Solution or The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. These pastiches/continuations are clearly side excursions, enjoyable or not in themselves and perhaps illuminating some aspects of the original tales. But according to Henry, we can’t appreciate the Matrix trilogy unless we understand that key story events have taken place in the videogame, the comic books, and the short films gathered in The Animatrix. The Kid in The Matrix Reloaded makes cryptic reference to finding Neo by fate, but only those who have watched the short devoted to him knows what that means. If Sherlock pastiches are parasites, the texts around The Matrix exist in symbiosis, giving as much as they take.

This strategy differentiates the new transmedia storytelling from your typical franchise. In most film franchises, the same characters play out their fixed roles in different movies, or comic books, or TV shows. You need not consume all to understand one. But Henry envisages the possibility of creating a whole that is greater than its parts, a vast narrative experience that doesn’t end when the book’s last page is turned or the theatre lights come up. His idea seems to be echoed in Will Wright’s suggestion:

It’s a fractal deployment of intellectual property. Instead of picking one format, you’re designing for one mega-platform. . . . We’ve been talking about this kind of synergy for years, but it’s finally happening.

Stimulating as this prospect is, it remains rare. The Matrix is perhaps the best example, but Henry suggests that it’s also an extreme instance: “For the casual consumer, The Matrix asked too much. For the hard-core fan, it provided too little” (p. 126). More common is a Genette-style transposition, in which the core text—usually the movie—is given offshoots and roundabouts that lead back to it. As I understand it, the Star Wars novels operate under the injunction that although they can take a story situation as the basis for a new plot, in the end that plot has to leave the films’ story arc unchanged. Similarly, websites with puzzles, games, clues, and other supplementary material tend to be subordinate to the film, planting hints and foreshadowings (The Blair Witch Project, Memento). Alternatively, the A. I. website provided a largely independent story world that impinged on the movie’s action only slightly.

The “immersive” ancillaries seem on the whole designed less to complete or complicate the film than to cement loyalty to the property, and even recruit fans to participate in marketing. It’s enhanced synergy, upgraded brand loyalty.

For the most part Hollywood is thinking pragmatically, adopting Lucas’ strategy of spinning off ancillaries in ways that respect the hardcore fans’ appreciation of the esoterica in the property. Caranicas quotes Jeff Gomez, an entrepreneur in transmedia storytelling, saying that for most of his clients “we make sure the universe of the film maintains its integrity as it’s expanded and implemented across multiple platforms.” It would seem to be a strategy of expanding and enriching fan following, and consequent purchases.

As best I can tell, then, in borrowing this academic idea, the industry is taking the radical edge off. But is that surprising?

Excerpt from www.ballsup.net

What a bloody week. Just now had a chance to update things. Fact is, it’s me last post. Luckily I let that cellphone drop and grabbed the satchel just before it fell into the Thames. Me and the crew are now packing for Bimini, ready for living large but in a rush becuz Big Chris may be looking for us. Hang on, must upload now, someone’s knocking at me d

Henry’s chapter in Convergence Culture grants that “relatively few, if any, franchises achieve the full aesthetic potential of transmedia storytelling—yet” (p. 97). Perhaps that hopeful “yet” will be fulfilled outside Hollywood? In the realm of the avant-garde, Matthew Barney has elaborated his own private mythology, dispersed among artifacts and hard-to-see films. In this he followed Joseph Beuys and Salvador Dalí. But you could argue that these artists really weren’t telling an overarching story. They were creating secular cults, full of arcana that only the pious initiates of Gallery Culture could grasp.

What about something more accessible? This month in Filmmaker magazine, Lance Weiler has suggested that indie filmmakers embrace the concept of transmedia storytelling (though he doesn’t use the term). Weiler argues that the explosion of digital technology has so transformed narrative that the filmmaker has to keep up. Instead of creating a script, with its genre formulas and three-act layout, the filmmaker should generate a bible, which plots an ensemble of characters and events that spills across film, websites, mobile communication, Twitter, gaming, and other platforms. The filmmaker designs “timelines, interaction trees, and flow charts” as well as “story bridges that provide seamless flow across devices and screens.”

Weiler doesn’t offer any specific examples apart from his Head Trauma, a horror feature accompanied by an alternate reality game that involved mobile and online access. You can watch his account of the “evolution of storytelling” here, where he and Ted Hope speculate about transmedia storytelling as offering economic help to filmmakers, reclaiming authorship from corporations, and promoting new relations with the audience.

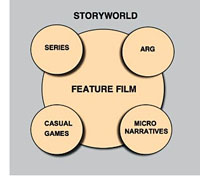

Hope and Weiler raise many fascinating questions about the prospects for multiplatform storytelling. At times, though, it seems that they accept the studio strategy of putting the film at the center of a multimedia ensemble. The diagram accompanying Weiler’s article illustrates that. It’s hard to think outside the franchise model, even if we want to denounce Hollywood for being stuck in an outdated commitment to the theatrical feature as foundational “content.”

Hope and Weiler raise many fascinating questions about the prospects for multiplatform storytelling. At times, though, it seems that they accept the studio strategy of putting the film at the center of a multimedia ensemble. The diagram accompanying Weiler’s article illustrates that. It’s hard to think outside the franchise model, even if we want to denounce Hollywood for being stuck in an outdated commitment to the theatrical feature as foundational “content.”

We should welcome experimentation, so I wish Hope, Weiler, and other creators well. But I think we ought to recognize some problems with expanding story worlds in these directions.

For one thing, most Hollywood and indie films aren’t particularly good. Perhaps it’s best to let most storyworlds molder away. Does every horror movie need a zigzag trail of web pages? Do you want a diary of Daredevil’s down time? Do you want to look at the Flickr page of the family in Little Miss Sunshine? Do you want to receive Tweets from Juno? Pursued to the max, transmedia storytelling could be as alternately dull and maddening as your own life.

Sure, somebody might go for it. Kristin points out, though, that people who would be motivated to follow up on all the transmedia bits of a spreadeagled narrative are people who would identify themselves as part of a fandom. There aren’t that many films/franchises that generate profoundly devoted fans on a large scale: The Matrix, Twilight, Harry Potter, The Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, Star Trek, maybe The Prisoner. These items are a tiny portion of the total number of films and TV series produced. It’s hard to imagine an ordinary feature, let alone an independent film, being able to motivate people to track down all these tributary narratives. There could be a lot of expensive flops if people tried to promote such things.

Consider a deeper point. Transmedia storytelling in the radical sense is posited as an active, participatory experience. Henry suggests that fans will race home from the multiplex to study up on iconography in The Matrix. Weiler’s article is accompanied by a hierarchy that lists “layers of interactivity.” The most superficial is “Passive Viewing,” defined as “Sit back and watch.” (Here Weiler parts company with Henry, who doesn’t consider ordinary viewing passive.) Further along are layers involving social networking, playing games, discussing or interacting with characters, finding hidden content, and even creating elements of the story world.

But it seems to me that film viewing is already an active, participatory experience. It requires attention, a degree of concentration, memory, anticipation, and a host of story-understanding skills. Even the simplest story gears up our minds. We may not notice this happening because our skills are so well-practiced; but skills they are. More complicated stories demand that we play a sort of mental game with the film. Trying to guess Hitchcock or Buñuel’s next twist can engross you deeply. And the very genre of puzzle films trades on brain strain, demanding that the film be watched many times (buy the DVD) for its narrational stratagems to be exposed. Films are interactive in the way a board game is: each move blocks certain possibilities, another anticipates what you’re going to do (mentally).

Moreover, how the ancillary texts add to the film is a crucial matter. No narrative is absolutely complete; the whole of any tale is never told. At the least, some intervals of time go missing, characters drift in and out of our ken, and things happen offscreen. Henry Jenkins suggests that gaps in the core text can be filled by the ancillary texts generated by fan fiction or the creators. But many films thrive by virtue of their gaps. In Psycho, just when did Marion decide to steal the bank’s money? There are the open endings, which leave the story action suspended. There are the uncertainties about motivation. In Anatomy of a Murder, did Lieutenant Manion kill his wife’s rapist in cold blood? Likewise, being locked to a certain character’s range of knowledge is the source of powerful emotional effects. We want to make the discoveries along with the character, be he Philip Marlowe or Travis Bickle.

The human imagination abhors a vacuum, I suppose, but many art works exploit that impulse by letting us play with alternative hypotheses about causes and outcomes. We don’t need the creators to close those hypotheses down. Indeed, you can argue that one of the contributions of independent film has been the possibility of pushing the audience toward accepting plots that don’t fit clear-cut norms. That innovation shrinks if we can run home to get background material online. By following the franchise logic, indie films risk giving up mystery.

At this point someone usually says that interactive storytelling allows the filmmaker to surrender some control to the viewer, who is empowered to choose her own adventure. This notion is worth a long blog entry in itself, so I’ll simply assert without proof: Storytelling is crucially all about control. It sometimes obliges the viewer to take adventures she could not imagine. Storytelling is artistic tyranny, and not always benevolent.

Another drawback to shifting a story among platforms: art works gain strength by having firm boundaries. A movie’s opening deserves to be treated as a distinct portal, a privileged point of access, a punctual moment at which we can take a breath and plunge into the story world. Likewise, the closing ought to be palpable, even if it’s a diminuendo or an unresolved chord. The special thrill of beginning and ending can be vitiated if we come to see the first shots as just continuations of the webisode, and closing images as something to be stitched to more stuff unfolding online. There’s a reason that pictures have frames.

Another drawback to shifting a story among platforms: art works gain strength by having firm boundaries. A movie’s opening deserves to be treated as a distinct portal, a privileged point of access, a punctual moment at which we can take a breath and plunge into the story world. Likewise, the closing ought to be palpable, even if it’s a diminuendo or an unresolved chord. The special thrill of beginning and ending can be vitiated if we come to see the first shots as just continuations of the webisode, and closing images as something to be stitched to more stuff unfolding online. There’s a reason that pictures have frames.

In between opening and closing, the order in which we get story information is crucial to our experience of the story world. Suspense, curiosity, surprise, and concern for characters—all are created by the sequencing of story action programmed into the movie. It’s significant, I think, that proponents of hardcore multiplatform storytelling don’t tend to describe the ups and downs of that experience across the narrative. The meanderings of multimedia browsing can’t be described with the confidence we can ascribe to a film’s developing organization. Facing multiple points of access, no two consumers are likely to encounter story information in the same order. If I start a novel at chapter one, and you start it at chapter ten, we simply haven’t experienced the art work the same way. This isn’t to say, of course, that each of us has an identical experience of a movie. It’s just that our individual experiences of the film overlap to an extent that allows us to talk about the patterning of the story under our eyes.

In correspondence with me, Henry suggests that transmedia storytelling may work best with television because of the serialized format; different people hop aboard at different points. I’d add that television’s installment-based storytelling, operating in the lived time of the audience, allows time for viewers to explore or create media offshoots. The installment-based nature of serial TV poses intriguing aesthetic problems of continuity, coherence, and memory. (See Jason Mittell’s essay on this matter.) For films, however, which are typically designed to be consumed in one sitting, multiple points of entry will tend to make plot patterns less clearly profiled.

If transmedia storytelling is difficult to apprehend for the viewer, it also makes critical analysis and evaluation much more difficult. How might we analyze overarching patterns of multiplatform plotting in The Matrix? True, one can itemize the inputs and decipher the citations, but it’s very hard to show how they work together, how they unfold, what it all adds up to—except to note that different people will encounter information bits at different times and with different states of knowledge.

Gap-filling isn’t the only rationale for spreading the story across platforms, of course. Parallel worlds can be built, secondary characters can be promoted, the story can be presented through a minor character’s eyes. If these ancillary stories become not parasitic but symbiotic, we expect them to engage us on their own terms, and this requires creativity of an extraordinarily high order.

Henry Jenkins suggests that for big-budget projects, this means finding unusually gifted collaborators. In the indie sector, the obstacles are even more considerable. Whether the result is Wendy and Lucy or Goodbye Solo, creating a first-rate feature-length movie takes tremendous talent, sweat, and resourcefulness. It is immensely harder to create a story universe that sustains the same intensity and quality across platforms. True, you can sprinkle clues and cryptic references among websites and YouTube shorts. The formulas of genre (horror, mystery) help you generate shock effects and mystification in teaser trailers. Appeal to stock characterization helps you mount a “realistic” Second Life life. But building a vast, sturdy world teeming with distinctive characters, unpredictable plotting, and human resonance is an immense task.

We await our multimedia Balzac. In the meantime, maybe indie filmmakers should settle for trying to be Chekhov.

http://tinyurl.com/scarkiller

Debbie, sorry 2 hav left SOOOO suddenlike. am @ Gila flats = cactus + varmnts. LOL with Blankethead!!! :-/

Uncl Ethan

Thanks to Henry Jenkins for comments on this entry. He recommends that interested readers have a look at Geoffrey Long’s 2007 MA thesis on the Jim Henson company, available, along with many other MIT projects, here. Thanks also to Kristin and Jeff Smith for suggestions, and to Janet Staiger for correcting my memory and calling attention to Dennis Bound’s book on “transmedia poetics” as applied to Perry Mason.

PS 11 Sept: Henry Jenkins has responded to my entry, with the first of three installments starting here.