Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

Pierced by poetry

DB here:

If I had a time machine, I’d zip over to Japan between 1924 and 1940. I’d trade a year of my life here and now for a year there and then.

Why? First, because the world I see in the movies of that period holds an irresistible fascination for me. I’d like to walk through Ginza, take a train to a spa, wander through Asakusa, have tea at the Imperial Hotel, hike around the temples of Kyoto. Second, if I could go back, I could see all the films I will never see—the lost Ozus and Mizoguchis, of course, but also the films we don’t even know are important.

For Japanese cinema in the 1920s and 1930s was one of the triumphs of world cinema. That era produced not only the two directors who are arguably the very greatest but also a host of talents you can’t really call “lesser.” The bench had depth in every position.

There are good reasons for this burst of genius. Quantity affects quality, but not the way snobs think: The more movies a country makes, the more good ones you’re likely to get. Although Japan had only a little more than half the US population, before 1940 it turned out about as many features as America did.In 1936, both countries released about 530 domestic productions.

The Japanese directors who started in the 1920s had, like Ford and Walsh in their salad days, to feed this audience. We tend to forget that even exalted figures entered the industry as high-volume producers. Mizoguchi averaged about ten releases per year in his first three years, Ozu about six. Everyone’s pace slowed with the coming of sound, but the sheer volume of movies pouring from studios big and small reminds us that young directors had plenty of opportunities to hone their skills.

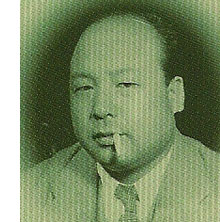

Probably the most startling instance is Shimizu Hiroshi. In a career that ran from 1924 to 1959, he’s credited with directing 163 films. The earliest one of his that I’ve seen is Seven Seas Part I; this 1931 feature was his seventy-fifth. “Next year,” he remarked in 1935, “I’m going to make only three films the way the company wants me to, and in exchange I can make two films that I want. I want a little more time. I’m too busy right now.” As things turned out, he signed seven films in 1936.

The great bulk of his work, 139 titles, falls before 1946. Fewer than two dozen of these seem to survive. With only about 17% of the films available, we have to keep our generalizations modest. Who knows what we would find in Love-Crazed Blade (1924) or Flaming Sky (1927) or Duck Woman (1929)? Shimizu contributed to a series, the “Boss’s Son” or “Young Master” films, of which only his first, The Boss’s Son at College (1933) seems to survive. What would we find in The Boss’s Son’s Youthful Innocence (1935) or The Boss’s Son Is a Millionaire (1936)?

Luckily, we’ve wound up with some extraordinary movies, not a clunker among the ones I’ve seen. If only a smattering of 1930s and 1940s titles is available, we should be happy that it was this smattering. Shimizu had concerns in common with Naruse Mikio and Ozu Yasujiro, but he established his own world, a rich tone, and a simple but subtle visual idiom. Along the way, he created some of the most heart-rending films in world cinema.

From the city to the spa

Shochiku talent at Izu hotspring, July 1928: Ozu Yasujiro (left), Shimizu Hiroshi (third from left), and screenwriters Fushimi Akira and Noda Kogo. Ozu and Shimizu were 23 years old.

Once more, all hail Criterion. TheTravels with Hiroshi Shimizu DVD collection released this spring includes Japanese Girls at the Harbor (1933), Mr. Thank You (1936), The Masseurs and a Woman (1938), and Ornamental Hairpin (1940). They were previously released on an expensive Japanese set (with English subtitles), but Criterion’s Eclipse series offers them at a more reasonable price, along with brief but helpful notes in English by Michael Koresky.

The collection’s title highlights the image of Shimizu that emerged in the 1980s. The films that struck Western critics then were typically shot outside the usual big cities (Tokyo, Kyoto, Osaka), in the mountains and seaside towns of the Izu peninsula. John Gillett’s 1988 National Film Theatre program, the first extensive survey of Shimizu’s work outside Japan, was entitled “Travelling Man.” Not only did Shimizu take his crew on the road, thanks to the expansion of the railway system, but he also exploited what became known as his signature technique: lengthy tracking shots down a road, following characters walking toward us.

Like Ozu, Shimizu worked in modern-day genres (gendai-geki), from slapstick comedies to college sports films. Most of what survives from before 1936 are social dramas of families, friendship, and fallen women. Seven Seas (1931-1932) deals with class conflicts, as a poor girl marries into a rich family and discovers that her husband is a bounder. Eclipse (1934) centers on the failure of young people from the countryside to succeed in a recession-hit Tokyo. The title of Hero of Tokyo (1935) is ironic, in that the stepson who abides by a mother held in disgrace by her other children, winds up destroying her last scrap of respectability. In Japanese Girls at the Harbor, two schoolgirls are driven apart by one’s passion for a young man. After a violent confrontation, she becomes a prostitute and her estranged friend winds up marrying him.

The Shochiku studio deliberately pursued a female market, and these tales of family intrigue and endlessly suffering mothers, wives, and daughters offer obvious figures of sympathy. Less predictably, the films simmer with criticism of modernizing Japan. They focus on the corruption of the upper classes, the collapse of traditions in the countryside, and the uprooting of the extended family.

Most significantly, Shimizu’s films indicate quite explicitly that Japan’s growing prosperity in the 1910s and 1920s was built on the backs of the rural poor, particularly the young women who flocked to textile mills, city shops, and brothels. Like many films of his contemporaries, Shimizu’s urban films mix sentiment and comedy with a harsh appraisal of social tendencies. I’d bet that we’d find both qualities in his Stekki garu (1929), a film apparently about the current craze for “walking stick girls,” women whom men hire to accompany them on strolls.

The manager Kido Shiro summed up the Shochiku spirit in the formula “smiles mixed with tears.” Ozu offered this blend in films like I Was Born, But… (1932) and Passing Fancy (1933), but there are precious few smiles in Shimizu’s surviving early thirties output. Then he took to the road.

In his films of travel Shimizu still offered social criticism, but he leavened it with off-center comedy. Indeed, he intensified Kido’s mandate: In Mr. Thank You, jaunty jazz and Latin American music accompany moments of sheer pathos. Now as well Shimizu’s intricate plotting, driven by the chance meetings and startling revelations of melodrama, could relax. Films like Mr. Thank You (1936), Star Athlete (1937), and The Masseurs and a Woman (1938) are expanded anecdotes, strings of situations that accumulate in casual fashion. Dramas emerge fleetingly, on the road or in hot-springs inns. The films tend to be brief, flowing toward abrupt, muted epiphanies in the manner of a short story. These movies make you ask whether 60-75 minutes might not be the ideal length for a movie.

In his films of travel Shimizu still offered social criticism, but he leavened it with off-center comedy. Indeed, he intensified Kido’s mandate: In Mr. Thank You, jaunty jazz and Latin American music accompany moments of sheer pathos. Now as well Shimizu’s intricate plotting, driven by the chance meetings and startling revelations of melodrama, could relax. Films like Mr. Thank You (1936), Star Athlete (1937), and The Masseurs and a Woman (1938) are expanded anecdotes, strings of situations that accumulate in casual fashion. Dramas emerge fleetingly, on the road or in hot-springs inns. The films tend to be brief, flowing toward abrupt, muted epiphanies in the manner of a short story. These movies make you ask whether 60-75 minutes might not be the ideal length for a movie.

The easygoing plots echo the movies’ production process. Shimizu wasn’t an obsessive planner. Whereas Ozu sketched every shot and checked the composition through the camera, Shimizu wrote minimal screenplays and seldom budged from his chair, even when the camera was traveling. He shot quickly, making up dialogue as needed and giving actors the most cursory direction imaginable. (“Run.”) Yet this wasn’t a high-pressure situation. Some days, uncertain about what to do, Shimizu would shut down the shoot and take people swimming.

Tears and smiles

I don’t want to leave the impression that Shimizu was careless; below I’ll try to show that he set himself some powerful storytelling problems. And his relaxed manner yielded a unique mixture of traditional drama and more vagrant appeals. Take Mr. Thank You, my pick for the crown of the Criterion set.

It’s a road movie, although the trip runs only twenty miles. A rickety bus winds through the mountains around the Kawazu region of Izu, an area of hot springs and tiny villages. The handsome, kindly young driver is known only as Mr. Thank You (Arigato-san) because whenever he forces walkers off the road he waves and calls his thanks. He has earned the devotion of people in the region, who entrust him with messages and duties on their behalf. On this particular day, his bus is carrying a stuffy real-estate agent; a wisecracking moga (modern girl); and a young girl whose mother is accompanying her to Tokyo, where she is to be sold into prostitution. Other passengers—wedding guests, lonely old men—get on and off in the course of the trip.

The bus stops often, and the encounters give us vignettes of the deteriorating life of the countryside. We hear of the magic attractions of Tokyo, reported by a prosperous woman about to get married. A Korean woman working on road construction asks Mr. Thank You to visit her parents’ grave, reminding us that this oppressed minority has contributed its sweat to the new Japan. Counterbalancing these stabs of pure feeling are simple running gags, such as one involving rude auto drivers who insist on passing the bus. And across the trip, the fate of the girl draws ever closer.

The moga (evidently a hooker) becomes our raisonneur, commenting on everyone’s motives, denouncing hypocrisies, flirting with Mr. Thank You, and eventually offering advice on how to save a life. Shimizu fills his film with talk and music, but in quieter moments imagery takes over: shimmering valleys below zigzag mountain roads, tunnels and forests and glimpses of steep paths along which road workers trudge. Within the bus, point-of-view is channeled fluidly. At one point we watch the moga watching the driver watching the girl. The climax of the action is simply omitted, yielding a quick, upbeat coda. In sum, Mr. Thank You radiates the cheerful, compassionate resilience of its namesake.

The mixture of tears and smiles is present as well in The Masseurs and a Woman. In Japan, blind people traditionally have taken up the trade of massage. So we start on the road, tracking back from two masseurs feeling their way along. The gags start immediately, with one praising the view, but poignancy comes just as fast: “It’s a great feeling to pass people who can see.” And again a gag undercuts it: “I bumped into some horses and dogs, though.” Shimizu sets up his brand of incidental suspense—uncertainty about matters of no dramatic moment—when the two begin to guess how many people are advancing to them. Eight and a half? We wait and, when the shot comes, we quickly count to check.

This seesawing between humor and pathos defines the tone of the whole film. Once the men arrive at the inn, we’re introduced to several guests, and a notably piecemeal plot: an aborted romance, a mysterious theft, and the attraction of one masseur toward an enigmatic woman. On the light side, students who tease the blind get extreme massage makeovers, reducing them to hobbling the next morning in a parody of the blind men’s halting gait. Shimizu assures their humiliation by head-on shots of modern girls hiking into the midst of them. And of course the blind-guy jokes multiply when several masseurs are trying to navigate a room or a street. Again, the film is over before you know it, leaving that Shimizu tang of chance encounters and what-if possibilities.

Blind masseurs play a minor role in another spa movie, Ornamental Hairpin (1941), but an almost-begun romance is there as well. Two women, Okiku and Emi, pass through an inn, and after they’ve left Emi’s hairpin jabs a young soldier’s foot. He will spend the rest of the story recovering his ability to walk. Emi returns to the inn and joins its summer guests: a cranky professor, a grandfather and his two pesky grandsons, and a married couple.

“Pierced by poetry,” says Nanmura casually about his wound, but the professor extrapolates on the phrase, trying to weave a romantic plot out of the accident. Shimizu declines to share the fantasy. A bit like Tati’s M. Hulot’s Holiday, the film is threaded with mundane vacation routines that become running gags, overwhelming what we expect to shape up as a courtship.

Bronzing in the sun and helping Nanmura recover his ability to walk, Emi comes to believe that she has found happiness. She has fled Tokyo and wants to start fresh. But her past, either as wife or kept woman, is kept vague. In two remarkable scenes, one a phone conversation and the other a dialogue with Okiku, her situation is sketched. We start to fear that her man will even come looking for her.

But these bits of conventional plotting are drop away among prolonged scenes of spa gossip and lazy pastimes. The most suspenseful sequences are devoted to Nanmura’s gradual recovery—a sort of deadline, since when he walks again, he will leave. If ever a climax refused to arrive, it’s during the last ten minutes or so of Ornamental Hairpin. The moments of pathos or conflict we would ordinarily see are skipped over, and the surroundings of “minor” scenes become infused with regret.

Shimizu’s ramblings through Izu didn’t lead him to abandon his probing of urban anomie, as we can see in Forget Love for Now (1937). (This must be one of the great Anglicized Japanese titles. I rank it with Blackmail Is My Life and Go, Go, Second-Time Virgin.) And at the same time he consolidated that talent for which he was best known in his lifetime: the exploration of childhood. Children in the Wind (1937), Four Seasons of Children (1939), and Introspection Tower (1941) offer unsentimental portrayal of boys’ rituals and their tenacity in the face of hardship. Shimizu founded an orphanage after the war, and he employed some of his charges in postwar films like Children of the Beehive (1948). Shochiku’s second boxed set, also with English subtitles, gives us the first three I’ve mentioned, plus the schoolteacher drama Nobuko (1940).

East meets West, and North meets South

Ornamental Hairpin.

Japanese film studios differed from their American counterparts in encouraging directors to cultivate individual styles. Kido supposedly fired Naruse by saying, “We don’t need two Ozus.” While Shimizu is not as daring or meticulous a stylist as Ozu, he managed to cultivate a visual approach that, however straightforward, was capable of delicate refinements.

In general, the Shimizus we have conform to trends in Japanese films of his period. His silent films from the years 1931-1935 adhere broadly to the Shochiku house style, using plenty of cuts and single framings of individuals. Most of the surviving silents have average shot lengths between 5 and 6 seconds, completely normal for both Japanese and US silent movies.

More remarkable is the number of dialogue titles, which make up between 24% and 44% of all shots. This would be exceptional for an American film of the 1920s. Other Japanese films, particularly Mizoguchi’s, are heavy with intertitles, but Shimizu took the trend somewhat farther. The preponderance of dialogue titles may owe something to the presence of both American and a few Japanese talking pictures at the time, which justified more spoken lines. In addition, at this period the influence of the benshi, the vocal accompanist to silent films, was waning, and the movies were becoming more self-sufficient in their narration. The hundreds of titles flashing by in Shimizu’s films would specify the scene’s action and curb the benshi’s urge to improvise.

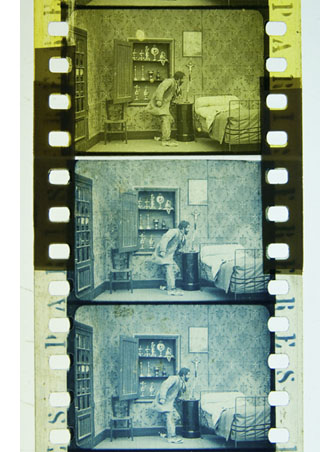

Shimizu’s silent films that survive also contain several instances of a technique I’ve called the “dissolve in place.” The camera setup remains fixed, but one or more dissolves convey the changes in the space across a period of time. It’s commonly used to show long periods; in A Hero of Tokyo, the family’s growing poverty is shown through dissolves that gradually remove the furniture they’re been forced to sell. The technique can be seen in American silent films, a major source for most Japanese directors. Here’s a lovely example from Frank Borzage’s Lucky Star (1929), as the partly paralyzed Tim struggles to climb onto his crutches.

Shimizu often goes a little further by matching the figures precisely across a dissolve. In The Boss’s Son at College, the hero comes home but then sneaks out in his bare feet, and the dissolves concentrate on the reversal of movement, first upstairs, then down.

Again, this device was used by other Japanese directors, even Ozu in some early works, but Shimizu seems to have clung to it longer than most.

In general, Shimizu’s silent films don’t borrow his pal Ozu’s more idiosyncratic techniques. Shimizu doesn’t employ intermediate spaces to link scenes, or create elaborately disruptive transitions, or embed characters in 360-degree shooting space. Sometimes he offers mismatched eyelines in reverse shots, but these don’t usually cultivate the graphically exact alignment we find in Ozu’s editing. Still, Shimizu does often construct a scene’s space in a distinctive way.

For one thing, he will stage many scenes in long shot or even extreme long shot. Within that sort of shot, he’s often drawn to deep perspective, often with a central vanishing point. This is most apparent as a visual motif throughout The Boss’s Son at College.

More interestingly, his fascination with perpendicular depth governs staging and cutting. Imagine a line stretched straight out from the camera lens. By 1935 this lens axis has become Shimizu’s lifeline, his equivalent of the surveyor’s level. Rather than filling the foreground with a big figure or a face or prop, and rather than spreading his depth items wide across the background, he will pack the most important people along the center axis, like crystals growing out from a string. Here are instances from Japanese Girls at the Harbor and Eclipse.

Shimizu’s co-workers have testified that he cared little for the 180-degree rule. Like many Japanese filmmakers, he played fast and loose with it. Instead of an axis running between the characters, he was more concerned with the axis of the lens itself. He often respects that by cutting from one shot to a point (along the axis) 180 degrees opposite.

He also respects the lens axis by cutting straight in and out. In Hero of Tokyo, the mother learns that her husband has pulled a swindle and fled; then the officials leave her alone with her children. Shimizu simply enlarges and shrinks her systematically along the axis. He takes us to the other side of the group for the climax, when her birth children pull away from her stepson. We see no other camera positions in the scene.

This patterning is less abrasive than it might appear because intertitles are sandwiched in among these shots. It’s an intriguing strategy for thrifty filmmaking, since it requires only a rudimentary set, but it also offers a simple way to inflect the drama. Similar axial cuts, though not cushioned by titles, can be found in the shooting scene of Japanese Girls at the Harbor (which may owe something to French and Soviet cutting experiments of the period).

The depth stretching out from the camera lens is crosscut by another plane, perpendicular to it. This plane is often a patterned surface—windows, grillwork, a bedstead. Again, instead of Mizoguchi’s or Ozu’s angular foregrounds, we have an east-west axis slicing through the shot. The frames become boxes, and the characters play out their dramas within the cells of a grid, as in Seven Seas Part II and Japanese Girls at the Port.

Here again, Shimizu is relying on a device that other directors were using at the time. Many compositions of the 1930s play peekaboo with characters and setting. Here’s a flamboyant example from First Steps Ashore (Shimazu Yasujiro, 1932).

So instead of defining space through exaggerated foregrounds, plunging diagonals, or curvilinear edges, Shimizu goes Cartesian on us. His most distinctive layouts rely on two dimensions, one running straight into depth, the other running left to right. The result is a discreet, foursquare style well-suited to concise storytelling (and presumably, to turning out films quickly). Shimizu’s peers indulged in flashier shots, but his persistent choices yield a quiet variant of that continuity system that was already the lingua franca of world cinema.

Hitting the road

What about the sound films? Many Shimizu films still rely on distant planes of depth, as in this shot from Children of the Wind, when, after the father’s arrest, the boys’ buddies arrive at a far-off vantage point.

Interiors will sometimes be given the axial-cutting treatment, as in this passage from Ornamental Hairpin.

And now the crosscut horizontal plane often gets actualized as rooms gliding by the lens in lateral tracking shots. But in general, interior scenes in this 1941 film aren’t as strictly organized as in the silent films. This corresponds to a general move toward more orthodox technique in Japanese films of the period.

Something more original happens in the outdoor traveling shots. Now Shimizu’s beloved camera axis finds tangible expression in the highway. His much-vaunted tracking shots up and down the road translate the silent films’ axial depth into forward and backward movement, and characters, again organized in relation to the axis, are presented with a new simplicity and directness. Rather than being a one-off device, the road shots seem to be a development of the Cartesian coordinates that Shimizu has experimented with in the interior spaces of his silent films.

Star Athlete offers some remarkable examples of the push-pull effects built around the axis—tracking back from advancing characters, or tracking toward retreating ones. But Shimizu’s most thoroughgoing exploration of the camera axis in transit takes place in Mr. Thank You. The first thirteen shots lay out a stylistic matrix, with variants dropped in to prepare us for more compact expression later.

Shot 1: A long shot of the bus approaching.

Shots 2-4: We get the bus’s point of view of the road, with road workers in view; head-on shot of the driver calling “Thank you!” as the men step back; and the bus’s pov of the road receding, with the workers resuming. Dissolve to:

Shots 5-7: Bus’s pov of horsecart ahead; reverse angle of driver calling, “Thank you!”; bus’s pov of cart receding. Dissolve to:

Shots 8-9: Bus’s pov of men toting wood; we hear, “Thank you!” as we dissolve to bus’s pov of men receding. Dissolve to:

Shots 10-11: Bus’s pov of women carrying bundles; we hear, “Thank you!” as we dissolve to bus’s pov of women receding. Dissolve to:

Shot 12: Bus’s pov of chickens in road. They scatter as we get closer.

Shot 13: Long shot of bus going into the distance as we hear, “Thank you!”

The cycles move from three-shot clusters to two-shot clusters to a single shot, and a gag at that. (This driver even thanks poultry for traffic courtesy.) As another touch, Shimizu’s prized dissolves-in-place are recalled when the pedestrians approached from the back transform themselves into figures dwindling into the distance.

The same insistence on rectilinear framing takes place on the bus. Using 180-degree reversals, Shimizu creates a remarkable variety of shot scales in the cramped space of a real vehicle, always obeying his self-imposed geometry–facing either forward or backward.

As the trip gains emotional intensity, Shimizu will vary his treatment of these principles. For example, the middle section’s emphasis on forward movement will be counterbalanced near the end by a string of shots of passengers already off the bus, passing into the distance as we roll away.

In Shimizu, compact storytelling is matched by a pictorial strictness that doesn’t seem forced or stiff. After all, people do tend to line up to face one another in depth, and roads and buses do seem to run in two directions. Poetry in language demands strictures of meter, rhythm, rime, and the like, for these can pressurize expressive energies. Shimizu’s films present a disciplined lyricism: powerfully oblique emotions are shaped by simple but rich techniques of storytelling and style.

Most of my information about Shimizu’s work habits comes from essays and interviews in Shimizu Hiroshi: 101st Anniversary, ed. Li Cheuk-to (Hong Kong: Hong Kong International Film Festival, 2004). For more on Shimizu’s surviving silent films, see William Drew’s penetrating essay in Midnight Eye. Alexander Jacoby offers a sympathetic career overview atSenses of Cinema. For a filmography, see Jacoby’s A Critical Handbook of Japanese Film Directors: From the Silent Era to the Present Day Stone Bridge, 2008). Isolde Standish reviews Shochiku’s studio policies in Chapter 1 of her A New History of Japanese Cinema: A Century of Narrative Film (Continuum, 2005).

Noël Burch was one of the first Western writers to appreciate Shimizu’s artistry. His indispensible 1979 book To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in the Japanese Cinema is available in its entirety here. The Shimizu chapter, concentrating mainly on Star Athlete, starts here. I offer discussions of stylistic trends in Japanese cinema in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema (Princeton University Press, 1988), available in toto here, and in two essays in Poetics of Cinema (Routledge, 2008), 337-395.

You can find passionate conversations about Shimizu and the release of these DVDs at the Criterion Forum. See especially the comments of Michael Kerpan.

Getting real

Art is not reality; one of the damned things is enough.

Attributed to Virginia Woolf, Gertrude Stein, and others.

DB here, with another followup to Ebertfest:

Ebertfest, once known as the Overlooked Film Festival, has always been keen to support American independent filmmaking. In previous incarnations, Roger spotlighted Junebug, Tarnation, and other movies that flew below the multiplex radar. This year’s crop was especially ripe. Besides The Fall and Sita Sings the Blues, there were important documentaries like Begging Naked and Trouble the Water. In particular, two fiction features set me thinking about types of independent storytelling and how they might be considered realistic.

The river is wide

Roger noted that when he first saw Frozen River, he wanted to bring it to his festival, but then it became the very opposite of an overlooked movie. It has grossed $4.3 million worldwide, a very healthy amount for a small-budget film without big stars. It won eleven national awards and was nominated for fourteen others, including a Best Original Screenplay Oscar. By now, you’ve probably seen it. I had been away during its Madison run, so I was happy to catch up with it.

“You have five minutes to show the audience you’re in charge,” commented director Courtney Hunt in the Q & A, and her film follows that advice. Seconds into Frozen River, we hit a crisis. Ray finds that her no-good husband has grabbed their savings and taken off to gamble, even as she waits for the delivery of their new prefab home. What begins as a drama of pursuit, with Ray trying to track down her husband, turns into a blocked situation. He’s gone and she has to not only pay off their mortgage but also keep her two sons going, counting on their school lunches to offset their domestic meals of popcorn and Tang.

Drama is about choices, and good drama is about bad choices. Ray has clearly made her share of mistakes—addictive mate, kids she can’t support, a bigscreen TV she can’t afford—and the plot shows her making the biggest of all. To scrape together money she agrees to transport illegal immigrants from Canada to upstate New York, driving across the frozen St. Lawrence. She casts her lot with Lila Littlewolf, a Native American with her own bad choices, and their common fate creates a series of parallels about motherhood that are resolved through Ray’s final sacrifice. The film also activates some current concerns about immigration, racism, and the problems shared by poor whites and ethnic minorities.

Resolutely unHollywood in its setting, theme, and characters—deglamorized women, especially—Frozen River still adheres to classical script structure. We have characters with goals, encountering obstacles and entering into conflicts, and the turning points come at the standard junctures. The ending is a resolution, although not an entirely happy one. In the course of the plot, suspense is built up at many points. Will Ray and Lila be caught by the state troopers who grimly monitor their comings and goings? What will become of that abandoned baby? The film is a sturdy example of how classic principles of construction can be applied to subject matter that is worlds away from our prototype of Hollywood filmmaking.

Neo-neo and all that

Ramin Bahrani’s Chop Shop, which I was also just catching up with, offers another flavor of independent dramaturgy. Roger has been a staunch supporter of Ramin’s films since Man Push Cart, and he has declared him “the new great American director.”

Bahrani has mastered a somewhat different narrative tradition than the crisis-driven plotting of Frozen River. “Neo-neorealism,” A. O. Scott has called it, linking Goodbye Solo to Wendy and Lucy, Treeless Mountain, Old Joy, and other films that offer us an “escape from escapism.” Now, Scott suggests, American cinema is having its delayed Neorealist moment. Richard Brody offers some useful, sometimes scornful, qualifications of Scott’s conjecture, reminding us of the urban dramas of the 1940s and the rise of Method acting. Scott has replied, claiming that their dispute essentially depends on their differing tastes in movies.

Here’s my $.02. “Neorealism” isn’t a cinematic essence floating from place to place and settling in when times demand it. The term, like the films it labels, emerged under particular circumstances, and it’s hard to transfer the label to other conditions. Moreover, there are many problems just with applying the term to Italian cinema, since it tends to cover not only the purest cases, like Bicycle Thieves, but also more mixed ones like the historical drama The Mill on the Po.

Still, because postwar Italian cinema had a big influence on other national cinemas, we have a prototype of The Italian Neorealist Movie. The filmmaker focuses on the lives of working people. He emphasizes their daily routines and travails. The film will be shot on location (at least in the exteriors) and may use nonactors in some or all roles. Bazin pointed out that we’re likely to find an elliptical or unresolved plot. It’s also very likely that we’ll see washlines and women in slips.

Why not just call this an Italian variant of that broad tradition of naturalism or verismo or “working-class realism” that we find in many national cinemas? In France there was the work of Andre Antoine (e.g., La Terre, 1921) and Jean Epstein’s Coeur fidele (1923) and his lyrical barge romance La Belle Nivernaise (1923). More famous are Renoir’s Toni (1935) and The Lower Depths (1936). (Recall that Visconti was Renoir’s assistant on A Day in the Country, 1936.) In Italy, there were harbingers too, not only the famous ones like Four Steps in the Clouds (1942) but also the charming Treno Popolare (1933). And Japan gave us many instances in the 1930s, notably Ozu’s Inn in Tokyo (1935) and The Only Son (1936).

Realer than real

On an Ebertfest panel Ramin Bahrani argued for a realist aesthetic. “Most people in movies never seem to pay rent or keep track of how often they can eat out . . . [Ordinary people] have day-to-day struggles; they ask how to survive.” That’s to say that a realistic work is distinguished primarily by its subject matter, the social milieu it presents. Bahrani also mentioned that some plot devices are unrealistic. Criticizing Slumdog Millionaire, he remarked: “My world doesn’t end in a Hollywood fantasy.” He didn’t deny the need for a dramatic structure, but he did insist on avoiding “obvious plot points like ‘He crossed the door and can’t go back.’”

This leads me to another $.02 contribution. I’m reluctant to contrast realism with something like artifice or formula. To me, realism comes in many varieties, but none escapes artifice. All realisms I know rely on conventions shaped by tradition.

For example, Chop Shop shows us a slice of life that most of us don’t know, the world of garages and salvage yards clustered around Shea Stadium. Such a low-end milieu is a convention of literary naturalism (Zola, Gorki). In this tradition, an artwork acknowledging the lives of the poor gains a dose of realism that, say, a novel by P. G. Wodehouse or a play by Noël Coward will lack. Some critics complained that when Rossellini’s Europa 51 and Voyage to Italy presented upper-class life, he left Neorealism behind.

There seem to me other conventions at work in Chop Shop. In one garage we find a boy, Alejandro, who has two goals. He wants to set up a food van that will sell meals to the men working in the neighborhood, and he wants to keep his sister Isamar safe from bad companions. Goal-driven plotting is central to Hollywood dramaturgy, as it is to much literary realism (e.g., An American Tragedy). It’s true that in real life people often form goals, but many do not, and those who do seldom come to a state of heightened awareness in the time frame typical of a movie’s plot. Alejandro fails to achieve one goal but partially achieves another, so we have an open, somewhat ambivalent ending—another convention of realist storytelling and modern cinema (especially after Neorealism). Life goes on, as we, and many movies, often say.

Instead of following a crisis structure, as Frozen River does, Chop Shop presents what we might call “threads of routine.” Most scenes consist of ordinary activities: the work of the garage, Alejandro’s sales of candy and DVDs, opening and closing the shop, Alejandro watching from the window of his room. But these vignettes aren’t sheer repetitions. They vary as Alejandro encounters progress or setbacks with respect to his goals. Most of the routines establish a backdrop against which moments of change and conflict will stand out.

Building a movie out of routines can also make convenient coincidences seem plausible. For instance, dramas have always relied on accidental discoveries of key information—the overheard conversation, the token that betrays what’s really happening. In Chop Shop, Ale and his pal Carlos discover that Isamar has become one of the hookers who service men in the cab of a tractor-trailer. They might have discovered this, as in life, by simply wandering by the spot on a single occasion. Instead, Bahrani’s script motivates their discovery by explaining that they habitually spy on the truck assignations. “Let’s go to the truck stop and see some whores.” Planting information in scenes of everyday activities seems more natural than giving it special emphasis at a moment of crisis. In two later scenes, the truck-stop becomes an arena for conflict, so Ale’s initial discovery motivates his later actions.

As for plot points, Chop Shop has them. (At about 15 minutes, the zone of the Inciting Incident, Ale declares his intention to buy the van. At about 30 minutes he discovers that Isamar is turning to prostitution.) Likewise, the threaded routines yield poetic motifs, such as the pigeons that are carefully established early in the film. Bahrani’s plotting is meticulous, and it highlights the paradox of realism: It takes effort and calculation to “capture reality.” De Sica was said to have endlessly rehearsed the boy in Bicycle Thieves.

What gives the film a more episodic organization than Frozen River, I think, and what gives it a greater sense of “dailiness,” is that it lacks deadlines. There’s relatively little time pressure on the action, except for Ale’s sense that he’s getting close to having enough money for the van. Chop Shop’s refusal of Hollywood’s ticking clock seems to me to confirm the observation, made by Geoff Andrew and J. J. Murphy, that in some respects American indie film is located midway between classical narrative cinema and “art cinema.”

The threads-of-routine pattern can be harnessed to character-driven drama, as in Chop Shop, but it can also be more opaque or minimalist. During at least half of Elia Suleiman’s Chronicle of a Disappearance, we watch anonymous characters go through routines, but instead of revealing their psychological drives, the scenes show the people overwhelmed by their surroundings. Narrative development is charted through changes in the spaces that the figures inhabit and vacate. The result is a “surreal realism” that evokes the anxieties of Magritte or de Chirico.

To say that realist traditions rely on conventions doesn’t make them less worthwhile. Chop Shops seems to me quite a good film. Nor would I deny that realist conventions do capture some aspects of real life. Both the crisis structure and the threads-of-routines structure can be taken as realistic. Sometimes our lives are in crisis, and at other times we do just plod along. But more stylized narrative forms can capture important aspects of reality too. The Searchers, a work of high artifice, renders a portrait of a self-destructive racist that many of us recognize in the world outside the movie house. Has any film better caught the adolescent yearning for romantic love and family stability than Meet Me in St. Louis?

The problem comes when we think that only one variant of realism can lay claim to validity, let alone beauty. Sometimes fidelity takes a back seat to vivacity. In Roy Andersson’s films, everyday nuisances like checking in to a plane flight or waiting in a clinic are inflated to grotesque, gargantuan proportions, becoming torments in a vision of hell. Like all caricatures, the exaggeration captures something true.

Comparing Wilkie Collins and Dickens, T. S. Eliot notes that both writers give us vivid characters. Collins’ characters are “painstakingly coherent and life-like,” terms of praise that we could assign to Bahrani’s films as well. But, Eliot adds, “Dickens’ characters are real because there is no one like them.”

What was Neorealism? Some of André Bazin’s invaluable essays on the subject can be found in What Is Cinema? vol. 2 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971). Kristin and I offer a survey of some historical factors in Chapter 16 of Film History: An Introduction. (Go here for a little bibliography.) For more on art cinema and its commitments to realism and open endings, see my essay, “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice,” in Poetics of Cinema, 151-169. On American indies’ borrowing of art-cinema conventions, see Geoff King, American Independent Cinema (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005) and J. J. Murphy, Me and You and Memento and Fargo (New York: Continuum, 2007). J.J. also has a blog entry on Chop Shop here. The quotations from T. S. Eliot come from “Wilkie Collins and Dickens,” Selected Essays (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1950), 410-411.

Songs from the Second Floor (Roy Andersson, 2000).

Color, shape, movement . . . and talk

Bonjour Tristesse.

DB here:

Our weekly Film Colloquium is sort of like your old high-school assembly, except that it’s fun. The Film Studies area meets nearly every Thursday afternoon at 4 to hear a paper by a grad student, a faculty member, or a guest. It’s a great forum for ideas and information, and it gives the speaker a chance to try out a talk before taking it to a conference or lecture gig. The local audience is, in my experience, the toughest I’m likely to encounter. And this spring, despite a heavy travel and work schedule, Kristin and I caught two outstanding presentations.

Not in color, but colored

By now we all understand that silent films were most often shown with musical accompaniment, and sometimes sound effects. But we tend to forget that most silent films were in color too.

By the early 1920s, 80% of films were colored in one way or another. There were a few efforts to record the actual colors in a scene, but most often color was added after filming. Areas of the frame might be painted over by stenciling or by freehand. More commonly, the shots were dipped into dyes, yielding images that were tinted (washing over the image and coloring the areas of white, as in the frames below) or toned (coloring the darkest areas and leaving the white areas white). Over the years, film prints were preserved in black and white, partly because color stock was more expensive than today. As a result, even archival prints lost the sense of what audiences actually saw. Today archivists labor to reconstruct what silent films looked like in all their rainbow glory.

Professor Joshua Yumibe of Oakland University wrote his Ph. D. thesis on early color processes, and his Colloquium talk asked some powerful questions. We know that there was a transition in film artistry from the late 1900s to the early 1910s, a shift toward what Tom Gunning has called the “cinema of narrative integration.” As films became longer and were shown in more or less permanent venues, moviemakers began to tell more complicated stories. How, Josh asks, did this shift away from a cinema of isolated “attractions” affect practices of coloring? Do color processes affect the way stories were told? Do the color processes change how people saw the space on screen? How did the trade press respond to different strategies of coloring?

Professor Joshua Yumibe of Oakland University wrote his Ph. D. thesis on early color processes, and his Colloquium talk asked some powerful questions. We know that there was a transition in film artistry from the late 1900s to the early 1910s, a shift toward what Tom Gunning has called the “cinema of narrative integration.” As films became longer and were shown in more or less permanent venues, moviemakers began to tell more complicated stories. How, Josh asks, did this shift away from a cinema of isolated “attractions” affect practices of coloring? Do color processes affect the way stories were told? Do the color processes change how people saw the space on screen? How did the trade press respond to different strategies of coloring?

These are fascinating questions, and Josh’s exploration of them was careful and detailed. He has done enormous research on the various color processes, and he was able to trace several lines of development. For instance, he found that writers of the earliest years thought that color enhanced the sensual and emotional effects of the image, even creating an illusion of 3-D. In a shot like that of the butterfly dancer, people seem to have sensed that her multicolored shape was thrusting out of the screen toward them.

Josh argues that with the growing emphasis on narrative, color became more muted. Filmmakers were no longer aiming at momentary stimulation but at ongoing mood. Now tinting and toning came into their own. Color codes developed: blue for night scenes, yellow for sunlight, red for fire, amber for artificial light. Josh also explored the different ways in which European and US companies conceived of color; there seem to have been different color policies at Pathé and at American companies. But this wasn’t the end of change. In the 1920s, with the feature film now at the center of the theatre program, a wide variety of color practices emerged, including those isolated Technicolor sequences we find in films like The Wedding March.

The Q & A was as lively as the talk itself, and afterward, we repaired to a bar and thence to dinner. Josh’s talk was a model of deep, imaginative research and it kept us thinking and talking for a long time afterward. Not to mention his slide show, which regaled us with gorgeous shots that make you realize how much you’re missing when you see an old movie in black and white.

Bass, o profondo!

Another stimulating Colloq session was presided over by our old friend Jan-Christopher Horak, director of the UCLA Film and Television Archive. Chris was in town because our Cinematheque has been showcasing UCLA archival restorations across the semester, and he introduced our screening of The Dark Mirror. But we also got him to give a talk, and that was quite something.

Chris reminded me that we first met thirty years ago, here in Madison, when he came to do research on his dissertation. Since then Chris has been a top-flight scholar and author of many books. His Lovers of Cinema, published by our series at the UW Press, laid the groundwork for the popular film series Unseen Cinema. He’s also been one of the world’s leading film archivists, having supervised collections at Eastman House, the Munich Film Archive, Universal studios, and most recently UCLA.

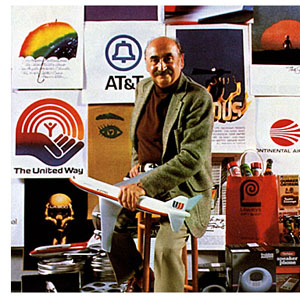

Chris has long worked at the intersection of film, photography, and the graphic arts. He is one of the world’s experts on the 1920s German avant-garde; one of his early curatorial coups was a 1979 restaging of the pioneering Film und Foto exhibition of 1929. Chris has also long been fascinated by film publicity, having written a book on the subject. So it’s natural that he would gravitate toward studying the film-related work of Saul Bass, one of America’s greatest graphic designers.

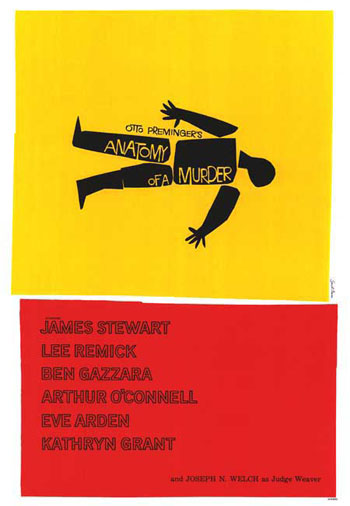

Chris’s talk focused not so much on Bass’s brilliant credit sequences for films by Preminger and Hitchcock as on Bass’s contributions to poster design. Bass turns out to have had a fascinating career, having worked in Manhattan advertising before moving to Los Angeles in 1948. Chris has found at least one early 1950s poster design that Bass probably executed, but he definitely worked for Preminger on publicity for The Moon Is Blue (1953) and Carmen Jones (1954)—the latter yielding to my mind one of the greatest credit sequences in film history. In 1955 Bass founded his own firm.

Chris’s talk focused not so much on Bass’s brilliant credit sequences for films by Preminger and Hitchcock as on Bass’s contributions to poster design. Bass turns out to have had a fascinating career, having worked in Manhattan advertising before moving to Los Angeles in 1948. Chris has found at least one early 1950s poster design that Bass probably executed, but he definitely worked for Preminger on publicity for The Moon Is Blue (1953) and Carmen Jones (1954)—the latter yielding to my mind one of the greatest credit sequences in film history. In 1955 Bass founded his own firm.

Throughout, he carried on the ideals of György Kepes, his teacher and a major conduit for Bauhaus ideas into America. Like his European models, Kepes promoted the idea of art as having cognitive value, teaching us to see the world in a new way. Kepes also emphasized that artworks could be of practical utility—an idea that chimed with Bass’s turn toward commercial design.

Chris was able to show that the Bauhaus tradition powerfully influenced Bass’s design principles. Who would have thought that the credits for The Seven Year Itch replayed Paul Klee? Obvious, though, when Chris showed us the images.

Chris emphasized two further points. First, Bass understood what we now call branding. We have to remember that it up to that time, most film publicity featured images of the stars, either in portraits or caught in typical scenes from the film. Bass’s poster design concealed the stars. Instead, he relied on dynamic geometrical design to capture a film’s mood in a powerful, stylized image. The result was an eye-catching logo, instantly recognizable: the flaming rose of Carmen Jones, the Vertigo whirlpool, the dismembered body of Anatomy of a Murder.

The key image could be repeated in newspaper ads, posters, credits, even the production company’s letterhead. When you saw the teaser trailer for Star Trek (“Under Construction”) dominated by that looming boomerang shape, you saw the heritage of Saul Bass. Who cares who’s in the movie? The very image is intriguing. No accident that Bass also designed many corporate logos, like the ATT bell and the United Way hand.

Chris’s second main point was that Bass was able to flourish because of the rise of independent production in the 1950s. Preminger, Hitchcock, and Wilder, acting as their own producers, could control the publicity for their films to a degree not possible for directors working in the classic studio system. Now films were sold as one-offs, and each film needed to pull itself above the clutter. In addition, Bass’s signature designs could set a director apart. In the 1950s, the Bass look was closely identified with his major clients like Hitchcock and Preminger, to the point that other designers for those directors tried to copy his style. I had always thought that Bass did the title design for Hurry Sundown, but Chris showed that it’s another artist’s pastiche of the master.

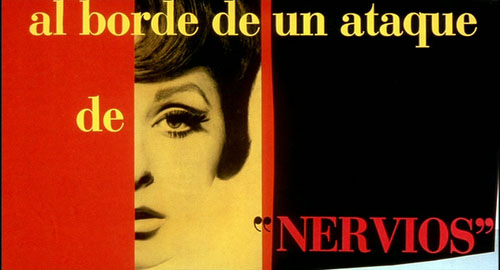

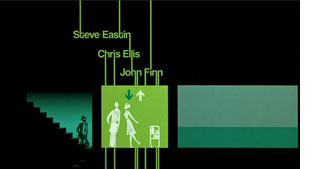

Chris’s talk reminded me that Bass contributed to making the opening credits a major attraction—not merely an overture, but an abstract treatment of the key story idea, a sort of graphic map that teases us into the main story. The opening sequences of Se7en and Catch Me If You Can (left) owe a lot to Bass’s idea that the credits should constitute a little movie, witty or ominous, tantalizing us with sketchy glimpses of what is to come. And Almodóvar’s diverting openings, probably the most sheerly enjoyable credit sequences we have today, are unthinkable without Bass. Synchronized with infectious music, Bass’s credit sequences can be seen as continuing the tradition of Walter Ruttmann and Oskar Fischinger, who back in the 1920s and 1930s made abstract films that advertised consumer goods.

Chris’s talk reminded me that Bass contributed to making the opening credits a major attraction—not merely an overture, but an abstract treatment of the key story idea, a sort of graphic map that teases us into the main story. The opening sequences of Se7en and Catch Me If You Can (left) owe a lot to Bass’s idea that the credits should constitute a little movie, witty or ominous, tantalizing us with sketchy glimpses of what is to come. And Almodóvar’s diverting openings, probably the most sheerly enjoyable credit sequences we have today, are unthinkable without Bass. Synchronized with infectious music, Bass’s credit sequences can be seen as continuing the tradition of Walter Ruttmann and Oskar Fischinger, who back in the 1920s and 1930s made abstract films that advertised consumer goods.

For such reasons, I’m glad I hung around Madison after my retirement. With visiting researchers like Josh and Chris, who wants to go fishing?

Woman on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown.

Thanks to Joshua Umibe for the silent-film illustrations. The first comes from Gaston Velle, Métamorphoses du Papillon / A Butterfly’s Metamorphosis (Pathé, 1904). Frame enlargement from Discovering Cinema (di. Eric Lange and Serge Bromberg, Lobster Film/Flicker Alley). The second comes from Albert Capellani’s Le Chemineau / The Vagabond (Pathé, 1905; tinted and toned). Frame enlargement Joshua Yumibe, courtesy of the Netherlands Filmmuseum.

Passion, mortality, and everyday life

DB, flying back from Hong Kong:

Some of the most important films playing at the Hong Kong International Film Festival were already familiar to me—Still Walking, Il Divo, Gomorrah, Ashes of Time Redux—and some of my discoveries in Hong Kong have been covered in more recent entries.

What remains? Accentuating the positive, I’ll not talk about the disappointing items, some with strong reputations. I hope to blog about others in the months to come, when I’ve had a chance to study DVDs.

In the meantime, Kristin has already touched on Beaches of Agnès, a real charmer. Varda can be whimsical without turning fey; even dressed as a potato she doesn’t seem to be trying to grab attention. The film is a digressive, passionate memoir. The background on her early life is captivating, and her career as a photographer, shooting snaps of Pierre Vilar and Gerard Philippe, furnishes a stab of pathos. A montage of beautiful boys and girls: gone. Soon we get Varda’s straightforward acknowledgment of Demy’s death from AIDS. “All the dead lead me back to Jacques.”

Götz Spielmann’s Revanche, which I’d passed up at other fests, was a very solid psychological thriller. It’s built around two contrasting worlds, the sex trade of Vienna and the placid, churchgoing lifestyle of a village. From the first comes Alex, a man-of-all-work in a brothel. He falls in love with a Ukrainian hooker, and between bouts of cocaine he vows to help her escape the business. In the village live the policeman Robert and his wife Susanne, trying to have a child. Their life is secure and cozy, though Robert is wound a bit tight. The two worlds intersect during a bank robbery, and the rest of the drama plays out in the countryside, with Alex taking refuge on his grandfather’s farm. Alex and Robert become two variants of masculine anxiety, each defined by his way with a pistol, and their decisive confrontation is deftly postponed until the very last moments of the film.

I admire the way that Spielmann uses a spare long-take technique to increase suspense. Each scene usually consists of a single shot, taken from a judiciously chosen angle that unfolds the drama smoothly. There are barely 200 shots in nearly two hours, but the scenes don’t seem stiff because the framing and staging are quietly varied. Shot/ reverse-shot cutting is reserved for two turning points, one in the middle and one at the end. It’s nice to see a movie with no filler material, no passages of people driving in cars or going into the buildings, none of those time-wasting aerial shots of cities.

Some nice sound work too! No Country for Old Men has been rightly praised for its use of offscreen noise, but the Coens look rather showoffish compared to what Spielmann has accomplished here. A shot of Robert and Susanne on their patio is accompanied by the faintest rustle on the right channel: Alex, spying on domestic happiness like a character out of Highsmith or Ruth Rendell, has slipped away.

Similarly elegant in its staging and sound work is Claire Denis’ 35 Shots of Rum. The teasing exposition—a man watches commuter trains, a young woman rides one—dares us to imagine scenarios that could involve both. Our speculations turn out to be too wild, since their relationship is the most uncomplicated to be imagined. Based frankly on Ozu’s Late Spring, 35 Shots builds up its drama through daily routines, following its principals and their neighbors in everyday situations until, quite unexpectedly, a quiet crisis blossoms. Soon one scene ends: “We could be like this forever.” Next scene: everything has been overturned, and characters must change their lives. Visually the film is a marvel, with glowing scenes of semidarkness and discreetly out-of-focus details. As in her masterful Beau Travail, Denis supplies a powerful last shot, this time of an object we’ve nearly forgotten.

Two more thoughts: In my discussion of Revanche and 35 Shots, I’ve had to be coy in explaining basic plot situations and character relationships. That’s because these films work elliptically, holding back the sort of expository information that would be given in a concentrated dose early in most classical narratives. This narrational strategy poses no problem for an academic analysis, which tends to assume that the reader has seen the film. But it’s more difficult to handle when you’re writing a review. You don’t want to spoil the viewer’s surprise by explaining a core situation that the filmmaker has chosen to unfold gradually. If reviewers of Hollywood movies can’t give away the ending, the reviewer of an art film probably shouldn’t give away the beginning, or at least the information that it keeps in suspension for some time.

In other respects, though, there isn’t a clear dividing line between the “psychological” drama of international festival cinema and the more “externally driven” action of mainstream entertainment. Popular cinema relies on physical props like clues, souvenirs, messages, and gifts to help drive the plot. So, less obviously, do art films. The two photographs in Revanche deepen the character drama while triggering a major realization. The accidentally discovered letter (a convention of melodrama akin to the overheard conversation) in 35 Shots not only explains past actions but primes us to expect some conflict to come. As Aristotle knew, stories seem to need tokens to drive character revelation and plot reversals. A narrative universal?

Japanorama

Naked of Defenses.

Many of the movies I most enjoyed were Japanese. No surprise there. I know I’m prejudiced in favor, but objectively speaking the Japanese industry has long combined high output with great diversity and depth. I’m inclined to think that across film history, the three most consistently excellent filmmaking nations have been America, France, and Japan.

During Filmart, Yoshizaki Masahiro gave a swift but informative report on the current state of Japan’s “content industry.” It is the currently the world’s second-largest national film market , but it will sooner or later be replaced by China. Currently Japanese films are reclaiming the local audience, sometimes grabbing over half the annual box office. Unfortunately, that audience isn’t growing, and with a plunging birthrate, it’s unlikely to do so. Moreover, Japanese cinema has always been difficult to export, even in Asia. The great exception, of course, is anime, but even that is starting to slump. Anime is largely a television/ video format, yielding about twice in those platforms what it yields in theatrical income. But as advertising dollars have withered in the recession, anime has been cut back.

Despite all this, Japanese companies manage to release a staggering 400 or so films per year. (What counts as a release—theatrical? direct to video?—we leave for another day.) And the variety remains remarkable, judging by what I saw during my stay in Hong Kong. Put another way: Japan makes movies that are sweet, touching, funny, silly, and peculiar to the point of perversity. Not necessarily perversion, but that’s there too. And yes, schoolgirls’ panties are involved.

Not part of the festival, but playing in town was the diverting comedy Happy Flight. Like Airport and Airplane!, it weaves together various characters involved with a single flight. It concentrates almost completely on the professionals, from gate agents and mechanics to pilots and air hostesses. The one passenger depicted in detail rings true: After being allowed to bring an oversized bag into the cabin, he becomes a browbeating jerk.

Not part of the festival, but playing in town was the diverting comedy Happy Flight. Like Airport and Airplane!, it weaves together various characters involved with a single flight. It concentrates almost completely on the professionals, from gate agents and mechanics to pilots and air hostesses. The one passenger depicted in detail rings true: After being allowed to bring an oversized bag into the cabin, he becomes a browbeating jerk.

The film maintains its infectious pacing, adorning the action with minor-key gags like the airport’s “Somkin Room” for smokers. I also liked the moments of teamwork. When the stewardesses need a cake, they concoct one out of various packaged snacks. A young mechanic, constantly berated by his boss, thinks he’s dropped a wrench into the plane’s engine, and the whole ground crew searches the hangar for it. As with Airplane!, the final credits resolve several plotlines and add a few gags. If you like Waterboys and Swing Girls, also directed by Yaguchi Shinobu, you’d probably enjoy this.

Just as light, but a lot more intricate is Nakamura Yoshihiro’s Fish Story. Another network narrative, this one traces how Japan’s purported first punk song changed the course of history. The plot skips among periods from 1953 to 2012, when a comet is about to incinerate the earth. With many pop-culture in-jokes, from Beatles albums to The Karate Kid, this breezy, off-kilter item gets by on sheer adrenaline and on a cascade of puzzles. Why does the Fish Story song make no sense? Why does it contain a one-minute passage of silence? How are all these stories connected? And how can a song save the world? The narration cleverly withholds the basic relationships among the characters until a dizzying montage at the end wraps everything up.

Still further out there on the Nutsometer is Love Exposure, your basic four-hour inquiry into Christianity, cross-dressing, superheroics, and schoolgirl underwear. The story starts with a boy who promises his mother he’ll marry a woman like the Virgin Mary, but thanks to digital photography and an acrobatic approach to filming schoolgirls’ nether regions, he becomes known to his peers as King of the Perverts. Director Sion Sono satirizes cult religions, which seems to include Catholicism (“Your sin is that you can’t remember your own sin”), while devoting some attention to pornographic movies and “Candle in the Wind.” Rambling and digressive, but rapidly paced, Love Exposure proves that nobody beats the Japanese for cheerful dirty fun.

Still further out there on the Nutsometer is Love Exposure, your basic four-hour inquiry into Christianity, cross-dressing, superheroics, and schoolgirl underwear. The story starts with a boy who promises his mother he’ll marry a woman like the Virgin Mary, but thanks to digital photography and an acrobatic approach to filming schoolgirls’ nether regions, he becomes known to his peers as King of the Perverts. Director Sion Sono satirizes cult religions, which seems to include Catholicism (“Your sin is that you can’t remember your own sin”), while devoting some attention to pornographic movies and “Candle in the Wind.” Rambling and digressive, but rapidly paced, Love Exposure proves that nobody beats the Japanese for cheerful dirty fun.

A more straightforward Japanese entry in the Asian Digital competition was Ichii Masahide’s Naked of Defenses (the most awkwardly titled film I saw). Two women work at a factory making plastic parts. Ritsuko, a plain but dogged supervisor, is becoming alienated from her husband after her miscarriage. She envies the pregnant and insouciant new hire Chinatsu, whose marriage is overcoming its problems. Plain and sincere in its technique, Naked of Defenses ends with an astonishing sequence. By all the evidence onscreen, Ichii got a pregnant woman to play Chikatsu and filmed her giving birth. Balancing this powerful ending is the striking performance of Moriya Ayako as a woman sinking into depression but who may be saved by friendship and maternal love.

I took the occasion to catch Departures at a local theatre, since I had missed it at earlier festivals. And I’m happy to report that it’s distributed in the US by Regent Entertainment, run by Wisconsin graduate and old friend Steven Jarchow.

By now you’ve probably seen Departures too. At one level, it’s a good old-fashioned Shochiku movie, mixing tears and good-natured humor. Some decry it as middlebrow sentiment, but I found it a touching, fluent tale. For me, the central attraction is the repertory of gestures. Our two professionals handle the recently deceased tenderly, but that doesn’t preclude a crisp efficiency in flaring out a sleeve. I don’t think I’ll forget the way the undertaker grasps the dead person’s clasped hands and then executes a circular snap. Precise manipulation becomes a sign of respect.

And it isn’t all sunniness. Handling dead bodies is hazardous cultural territory in Japan. It is traditionally a task for the burakumin, a minority group long looked down upon. Although discrimination against the group has apparently diminished, the fact that a big star like Motoki Masahiro could play the role of a corpse-preparer could help dispel a lingering social stigma.

You could almost mount a Japanese film festival about mortality. Some musts would be Ozu’s Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family and Tokyo Story, Kurosawa’s To Live, and Kore-eda’s After Life. Another required item would be Dying at a Hospital (1993), a rarely seen Ichikawa Jun film screened as part of a tribute to the recently deceased director. It consists of staged episodes showing a few cancer patients in their last months. An elderly husband and wife both have cancer, but must separate and be treated in different hospitals. A widow laments her rotten luck. A lively young man can’t accept the fact that he won’t see his children grow up. A homeless man is brought in, filthy and disoriented, and as he becomes aware of his plight, he still apologizes for accidentally turning up his pocket radio.

These and other cases are accompanied by voice-over narration from the doctor and nurse who treat them. Interspersed with these scenes are rapid documentary montages of people enjoying life—eating, drinking, viewing cherry blossoms, celebrating festivals, just walking down the street. The intimate facial reactions we’re denied in the hospital scenes are supplied in these vérité passages.

Dying at a Hospital is gentle and sympathetic, but its manner of shooting gives it special resonance. The hospital scenes are shot in planimetric fashion, with the camera rigidly facing a row of three beds, or a pair of beds, or only a single one. Everything is played in long shot, with no close-ups or camera movements to enlarge the faces.

Patients, visitors, and hospital staff move through these blocks of space. The lighting effects are particularly subtle, accentuated by very gradual fade-ins and fade-outs, as if dawn were breaking or night were coming on. As the film goes on, Ichikawa introduces variations in scale and new cutting patterns, creating what I called in Narration in the Fiction Film a sparse version of parametric narration. For instance, the spaces become more compact as terminal patients are shifted from a shared room to a private one, which permits nuanced effects of distant depth.

Ichikawa’s dry, physically detached treatment lets the poignancy of each situation emerge without any directorial boosting. The glimpses of daily life outside the hospital, zestful and shot on the fly, generate a powerful contrast: the preciousness of ordinary pleasures, and the dignity that must be accorded everyone about to leave them behind.

For a brief but sensitive appreciation of 35 Shots, see Ryland Walker Knight’s comments here–perhaps best read, for reasons mentioned above, after you’ve seen the film.

Departures.