Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

Happy birthday, Film Workshop

Tsui Hark is the mad genius of Hong Kong cinema. The problem comes with assigning proportions. 10 % mad, 90% genius? 50-50? 99 % mad, 1 % genius?

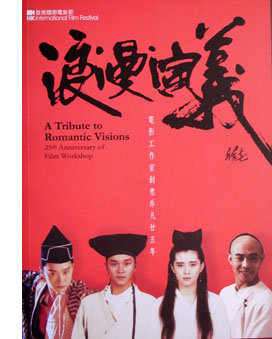

Across a career that’s lasted more than thirty years, Tsui has had more ups and downs than the local economy. On the twenty-fifth anniversary of Film Workshop, the company he founded, the Hong Kong International Film Festival mounted a tribute. That provides an occasion to examine what he did and didn’t accomplish.

25 years old, but who’s counting?

Nansun Shi and Tsui Hark.

At this year’s Asian Film Awards, Film Workshop was given a special prize for outstanding achievement. On another evening there was a party gathering many Workshop alumi, from which the above photo comes. You can see more pictures from that party here. At the agnes b. gallery, a small show featured posters, a looped video documentary, a photocopy of the Better Tomorrow script, and some memorable props.

Nat Olsen has other pictures at his lively Hong Kong Hustle site.

The catalogue, A Tribute to Romantic Visions: 25th Anniversary of Film Workshop, is a must for all aficionados of Hong Kong film. Consisting largely of interviews, it offers many glimpses of creative choices and business strategies governing the company. Nansun Shi, Tsui’s partner and business manager, recalls how they placed films in overseas markets and won critical acclaim in Europe. She also explains matter-of-factly how frantic the midnight-show system was. In those days, Hong Kong filmmakers test-screened a movie to a midnight audience, and then reedited the film based on perceived reaction. Shi explains:

The catalogue, A Tribute to Romantic Visions: 25th Anniversary of Film Workshop, is a must for all aficionados of Hong Kong film. Consisting largely of interviews, it offers many glimpses of creative choices and business strategies governing the company. Nansun Shi, Tsui’s partner and business manager, recalls how they placed films in overseas markets and won critical acclaim in Europe. She also explains matter-of-factly how frantic the midnight-show system was. In those days, Hong Kong filmmakers test-screened a movie to a midnight audience, and then reedited the film based on perceived reaction. Shi explains:

Cinemas often wondered what could be done to a film in the eight hours between the midnight show and the day-time show the next day. I ran some calculation with the technicians: what is the least amount of time for them to do this and that, and then sent them to the cinemas to do the work. If worse comes to worst, they could do the re-editing when the show was running (80).

There isn’t much sugar-coating in the interviews. Collaborators often found Tsui a harsh taskmaster. At peak pressure, he seldom halted shooting for sleep and instead took cat naps on the set. Those who couldn’t keep up his pace, or adjust to his demands, left the company. There are also some comments on production practices. Herman Yau, for instance, notes: “Directors, in general, use most of the shots to tell the story. Tsui prefers images that look good on their own” (121).

Overall, the catalogue confirms that what started as a “workshop” designed to enable directors to realize individual creative visions became a company built around Tsui’s restless ideas about cinema. This was more or less the premise of the panel on Friday afternoon. Two critics, Keeto Lam and Longtin, discussed the Film Workshop enterprise largely as an extension of Tsui’s interests. Keeto had been a screenwriter at the company and shared information about the making of A Chinese Ghost Story 2, while Longtin speculated on Tsui’s interest in transcending polarities, particularly those between human and demon and male and female. Another scriptwriter was in the audience and contributed information as well.

One of Keeto’s points set me thinking. Having characterized Leslie Cheung as the “Golden Boy” of Film Workshop, he asked who the Golden Girl was, and he and audience members discussed candidates for the honor. (My vote, obviously, would go to Brigitte Lin.) But I began to speculate that one of Film Workshop’s main contributions was in star-making. Tsui has mentioned that his early films with gorgeous women tried to create a “comedy of pretty faces” opposed to the “comedy of ugly faces” that ruled in the 1970s and early 1980s. (Think of Michael and Ricky Hui, Karl Maka, Jackie Chan, and Sammo Hung.) By coaxing Brigitte Lin to Hong Kong and by giving Sally Yeh, Leslie Cheung, Chow Yun-fat, and other younger players big roles, Film Workshop created a new generation of glamorous stars.

A better yesterday

This celebration comes at a parlous period in Tsui’s career. Over the last dozen years Tsui directed some weak, even awful movies. Granted, even a bad Tsui movie is bad in a unique way, but that doesn’t make Tri-Star (1996), the Van Damme outings (Double Team, 1997; Knock Off, 1998), and The Legend of Zu (2001) any better. Some films he has produced, like Era of Vampires (2002) and Xanda (2003), are best forgotten. Today, after the only moderate success of Seven Swords (2008) and the disappointments Missing (2008) and All About Women (2008), many local film professionals consider him a spent force.

I’d argue that Tsui and Jackie Chan were the two most ambitious young filmmakers of 1980s Hong Kong. Tsui was the more daring and mercurial; he seemed to be trying a dozen things at once. He made some bad films, but others changed the face of local film: Shanghai Blues (1984), Peking Opera Blues (1986), A Better Tomorrow III (1989), Once Upon a Time in China I and II (1991, 1992), The East Is Red (1993), and The Chinese Feast and The Blade (both 1995). He also produced, and often co-directed, A Chinese Ghost Story and A Better Tomorrow (both 1986), The Big Heat and Gun Men (1988), The Killer (1989), the demented Wicked City (1992), and Iron Monkey (1993). These films had enormous impact locally, and they made Hong Kong film a major force in world cinema.

The problem is the mad-genius thing. Tsui is uneven, not only from film to film but within each one. Tsui can create a fairly unified tone, as The Blade and Seven Swords show. But more likely a Tsui film will contain something brilliant, something banal, something silly, and something just weird. Labored facetiousness is a virus plaguing Hong Kong film generally, but Tsui seems entirely too fond of bursts of dumb comedy. He replies: “Sometimes it’s fun to be stupid.”

Yet the thrown-together quality of many of his movies also means that even a troublesome one is likely to have a passable sequence. More important, his best films use the lurches in tone to create a grotesque, sweeping verve. Things happen so fast you can’t protest; either go with it or walk out.

Tsui’s strategy is based upon a breathless rhythm. He chops off scenes without warning, and he bustles his actors around the set maniacally; the poor things seldom rest long. Almost never do characters simply sit down and talk to one another, as in those bland American indie films. The beginning of Triangle (2007) shows how nervous, even opaque, Tsui’s style becomes when characters have to sit still.

For Tsui, story action is a matter of physical movement, and the film frame becomes a force-field, with actors popping in and out with abandon. He carries the staccato choreography of martial-arts film down to the most straightforward dramatic scene. He’s not alone in this; you can find it in the 1980s martial-arts films too, but Tsui gives it a special force with his pitched angles, his wide-angle lenses, and his love of comic-book-rococo compositions. Try, for instance, this shot of a woman getting an injection in Missing.

Such images can seem merely cheap flash, but what saves the best ones from preciosity is their constant but disciplined rhythm. In Once Upon a Time in China, Wong Fei-hung is about to be arrested after a clash with local thugs. The shot starts with the police official pointing his pistol to Wong’s head.

Another cop comes in to tell the official that the invaders left something. Any other director would have shown the cop’s face, but why? He’s important only to get the official out of the frame, so he becomes just a red hat poking in from the lower right corner.

The official dodges out, moving rightward across the frame.

There’s a pause, then Wong, now isolated in the shot, snaps his head around to follow what’s happening.

Tsui isn’t usually considered an economical director, but it’s hard to imagine a more crisp way to handle this routine bit of action. The shot takes less than eight seconds.

The same restless energy rules Tsui’s cutting, which has a punch and recoil derived, I think, partly from New Hollywood (Spielberg especially; see the Jaws example here) and partly from the local martial arts tradition. (Some proto-Tsui cutting is on display in Lau Kar-leung’s Legendary Weapons of China, 1982.) Watching Once Upon a Time in China at the retrospective, I was reminded that Tsui not only cooks up sequences that you can’t forget (three words: fight on ladders), but he risks audacious cuts on movement that few contemporary directors could bring off. When he wants to emphasize a moment, he channels Eisenstein. During the final combat of Wong and Iron Robe Yim, the iron weight sliding down the platform gets the Potemkin treatment. Four shots stretch out the instant through overlapping movement.

As we might expect, Tsui goes beyond Eisenstein by accentuating major points of impact with swift camera movements forward.

Tsui thinks visually. True, some sound is important—he is a master at merging music and image—but words are a last resort. He has been known to change dialogue in post-production so radically that the dubbing doesn’t match the actors’ lip movements. Shooting without sound gives Tsui, like other Hong Kong directors, a freedom of camera placement that recalls the silent cinema. And like a silent director, he thinks that every story point needs to be pictured. Kenny Bee is looking for the girl he met years ago (Shanghai Blues)? So let’s have an image that dramatizes the problem.

The inclusion of Kenny’s graduation picture might seem superfluous, but it makes the frame an anticipatory wedding picture, and it gives us a sense of his pure, if naïve, romantic impulses.

Motion plus or minus emotion

Shanghai Blues.

If you disapprove of what Spielberg and Lucas did to the American cinema, you will hate Tsui’s love of remakes, sequels, and spinoffs, his frequent confusion of SPFX with imagination, and his efforts to milk franchises to a point that can be considered cynical. Yet historically, he pushed Hong Kong cinema forward.

Before the star-making efforts I’ve already mentioned, indeed before Film Workshop was created, Tsui’s Dangerous Encounters: First Kind (1980) offered a blistering attack on class disparity in Hong Kong. He updated Cantonese fantasy swordplay in Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain (1983), and he tried his hand at a local version of low-budget exploitation in We’re Going to Eat You (1980). Keeto’s catalogue essay argues that Film Workshop pioneered six new genres in Hong Kong film, from comic-book adaptations to science-fiction and animation. And there’s more variety than we might expect. Film Workshop directors might have sometimes mimicked his style, but John Woo’s Workshop projects managed to do something quite different. Despite Tsui’s hands-on involvement, the lyrical Iron Monkey and the more hard-edged Gun Men and The Big Heat avoid the eccentricities of his signed work while maintaining his love of flamboyant set-pieces and visual creativity.

Tsui’s scripts often seem like patchwork, granted, but I tried to show in Planet Hong Kong that the episodic, additive plotline is a convention of Hong Kong cinema. Tsui—like Wong Kar-wai, though in a different key—took advantage of this formula to explore the power of the arresting image and an infectious rhythm. (You might say that Wong’s rhythm is that of cool jazz, while Tsui’s is closer to the percussiveness of Chinese opera.) Shanghai Blues and Peking Opera Blues, two of Tsui’s most ingratiating movies, jump smartly from one thrusting scene to the next, shifting emotional registers with dazzling speed. These movies can turn on a dime.

Tsui’s scripts often seem like patchwork, granted, but I tried to show in Planet Hong Kong that the episodic, additive plotline is a convention of Hong Kong cinema. Tsui—like Wong Kar-wai, though in a different key—took advantage of this formula to explore the power of the arresting image and an infectious rhythm. (You might say that Wong’s rhythm is that of cool jazz, while Tsui’s is closer to the percussiveness of Chinese opera.) Shanghai Blues and Peking Opera Blues, two of Tsui’s most ingratiating movies, jump smartly from one thrusting scene to the next, shifting emotional registers with dazzling speed. These movies can turn on a dime.

Part of what pulls us along is characters we care about—especially strong women. In the old days, we Hong Kong fans used to love the idea that John Woo, carrying on the Chang Cheh tradition, specialized in the sorrows of masculine obligation, while Tsui was much more interested in women. He gave us the comedy of pretty faces, the wide-eyed innocence of Joey Wong, and the severe beauty of Brigitte Lin who, in the final installment of the Swordsman series, becomes a sheer force of nature. (Her bi-gendered role in Ashes of Time stems from Tsui’s creation of her as such in Swordsman II and The East Is Red.) When Tsui took over the Better Tomorrow franchise, his prequel showed that Woo’s ideal hero Mark (Chow Yun-fat) learned his combat crafts from, of all people, a woman. Even the non-stop testosterone fervor of The Blade, all sweaty torsos and clanking weaponry, may be the hallucination of a madwoman.

These were rousing yarns. Yet at some point, I think, Tsui lost interest in telling a story. This tendency can be detected already in the Van Damme projects; the opening of Knock Off revels in visual effects (microscopic close-ups of the ripping fibers inside running shoes) but doesn’t dwell on what we need to know. Tsui’s task in the collaborative film Triangle was to simply to set up the premises of the action, but dialogue-driven exposition seems to bore him, and the opening scene is a frenzy of eccentric angles and barely registered plot points. His SPFX extravaganza The Legend of Zu has a fairly incomprehensible story to begin with, but by swamping it in explosions and magical transformations, Tsui makes a movie that is, like Spinal Tap’s amplifier knob, permanently set at 11.

With the lack of interest in economical storytelling comes a resistance to emotional engagement. Time and Tide has some virtuoso passages—the tenement sniping, the finale in Kowloon Station (with a woman giving birth during a gun battle)—but the film’s jittery momentum and lack of a coherent point of view sacrifice everything to momentary visceral impact. The death of a little boy caught in the crossfire is not a stab of pathos but the pretext for the visual shock of a ricocheting skateboard.

Tsui’s first films often shied away from sustained romantic scenes, a point made by Sylvia Chang in a catalogue interview. Still, he sometimes translated the awkwardness of love into gesture and motion, from the race to the train at the end of Shanghai Blues to the tender exchange of morsels of food between reconciled husband and wife in The Chinese Feast. Even Once Upon a Time in China can pause for a moment to let Aunt Yee reveal her growing affection for Wong Fei-Hong by having her shadow stroke his.

In the early FW films, emotion was translated into movements large or small. Losing her love makes a woman turn abruptly and snap out her cape, underneath a billboard advertising her lover’s song. But more recently Tsui seems to suffocate emotion in a welter of one-off effects. The lustrous HD shots of Missing make it visually striking, but the lacquered technique doesn’t seem to me to serve the story’s core drama of loss.

We can’t write Tsui off. He’s not yet sixty, and his new project, the Tang era mystery Detective Dee, sounds promising. Whatever happens next, his many admirers thank him and the FW team for some of the most radiant moments in modern cinema. Everyone who has seen Shanghai Blues needs only the stills at the top and bottom of this entry to conjure up the scene: Kenny plays his violin on the rooftop, we hear the soaring tune “Shanghai Nights,” and as we see Sally listening on another balcony, a chill goes up your spine. A little mad, but mostly genius.

Thanks to Alvin Tse for the illustration from the Film Workshop party.

A masterpiece, and others not to be neglected

About Elly.

DB still in Hong Kong:

I haven’t been slack, honest; I’ve caught several items at the archive and during the first weekend of the Film Festival. I even saw Watchmen, accompanied by rump-shaking Shaw Active Sound. But today let me get caught up with some films I saw in Filmart last week.

I was unimpressed by the picture that launched Filmart, Derek Yee’s Shinjuku Incident. Billed as Jackie Chan’s emergence as a real actor, it features him as a confused illegal immigrant thrown into the Tokyo underworld. His character never made sense to me, and the direction was formulaic: basically pan around a group of actors until somebody says something. Daniel Wu gets to play another maniac.

Less heralded Filmart screenings were much more satisfying. The best, and my favorite film I’ve seen so far this year, was About Elly. It is directed by Asghar Farhadi, and it won the Silver Bear at Berlin. I can’t say much about it without giving a lot away; like many Iranian films, it relies heavily on suspense. That suspense is at once situational (what has happened to this character?) and psychological (what are characters withholding from each other?). Starting somewhat in the key of Eric Rohmer, it moves toward something more anguished, even a little sinister in a Patricia Highsmith vein.

Gripping as sheer storytelling, the plot smoothly raises some unusual moral questions. It touches on masculine honor, on the way a thoughtless laugh can wound someone’s feelings, on the extent to which we try to take charge of others’ fates. I can’t recall another film that so deeply examines the risks of telling lies to spare someone grief. But no more talk: The less you know in advance, the better. About Elly deserves worldwide distribution pronto.

Also worth seeing was A Place of One’s Own, a Taiwanese film that uses imagery of living spaces to explore generational differences. As a young rock singer’s career fades, his pop-star girlfriend’s career takes off. Their fates are intertwined with those of a family who live near a cemetery. The father makes exquisite paper dwellings that are burned during funeral ceremonies, the mother maintains gravesites (and talks to ghosts), while the son launches himself on a real-estate career with the help of a dodgy rich kid. Director Ian Lou (God Man Dog) enhances this network narrative with some clever flashback constructions as well.

My Dear Enemy.

Two films I saw in the market display different ways of using past incidents to explain a story’s present-time crises.

My Dear Enemy, by Lee Yoon-ki, exhibits a striking concentration and dramatic focus. Hee-soo’s boyfriend Cho borrowed $3500 from her before they broke up. Today she has tracked him down and demands it back. She drives him around as he visits various associates—his biker cousin, a high-class prostitute, a rich older woman who seems to be using his sexual services, an unmarried mother—scrounging for money to pay Hee-soo back. Across a day of setbacks both comic and frustrating, we come to learn of their romance and their deeper personalities.

At first Cho seems the classic annoying charming rogue, chattering about the music he likes, pausing to buy flowers and oversweet coffee, flattering every woman he meets, and on the verge of ducking Hee-soo’s demands. Every time he gets out of the car, you think he might bolt. These first impressions, however, get nuanced as we see how he moves easily and even gracefully through his milieu. He seems a loser, but we learn that he is resilient and resourceful. Meanwhile Hee-soo’s righteous determination to get her money back comes to seem something of a desperate effort to close the book on painful episodes from her past.

Lee Yon-ki, who earlier gave us This Charming Girl, is very good at structuring scenes so that we understand every character’s changing attitudes. To get the money, Cho lets his target think that he’s helping out Hee-soo, and at one point he implies that she’s pregnant. As Hee-soo realizes that he’s making her play a part in his drama of self-aggrandizement, she is hurt and ashamed. And Cho’s happy-go-lucky facility in his milieu makes her feel more of an outsider. One scene, in which Cho’s hooker friend calmly insults Hee-soo, is a subtle study in casual humiliation.

Yet Hee-soo’s tenacity wins Cho’s respect. At the same time, while as the day passes into night, Cho emerges as a figure with his own code of honor (he eventually provides a meticulous account of what he’s cost her in the day’s expenses) and even a dream of success that might, the last shot suggests, be fulfilled. Bits of business around coffee, cellphones, flowers, and a broken windshield wiper chart the fluctuations in their relationship concisely. My Dear Enemy is a model of how to make a tight, intimate movie focused on simple incidents that carry almost Hitchcockian tension: Will Cho pay Hee-soo off? Will he slip away and abandon her again? What will we learn next about each one’s past? Like About Elly, this is a character study with an engrossing plot.

More diffuse, I thought, was Ann Hui’s unfortunately titled Night and Fog. It’s a companion piece to The Way We Are, her 2008 study of life in the Tin Shui Wai area of Hong Kong. I offered an admiring account here.

This is the “darker story” Ann promised us at last year’s festival, and it’s based on an actual case. Lee Sum has married a Mainland woman, Ling, and has fathered two daughters with her. He’s on social security and Ling works as a waitress. But Lee is considerably older, and he suspects her of flirting with other men. He becomes insanely jealous, beating her and throwing her and their daughters out. Ling finds happiness in a woman’s shelter, but social services fail her and Lee brutally murders her and the children.

No harm in telling you the ending because the murder is the first thing we see. The film consists of a series of flashbacks, some nested within others, that trace what led up to Lee’s horrendous crime.The plot is presented in the framework of a police investigation, with witnesses to Ling’s life answering questions that pass into scenes from the past. The early flashbacks are quite linear, treating the buildup to Ling’s stay in the shelter and a moment in which she sings a song about a mushroom maiden. Then we plunge further into the past, showing her leaving her provincial home as an adolescent on the way to work in the city. Soon we’re given early moments in Lee’s courtship of her.

One effect of introducing the early stages of their marriage late is to mitigate the harsh portrayal of Lee that has dominated the first half of the film. He seems genuinely in love with Ling, and he rebuilds her parents’ home. Already, however, we glimpse his drunkenness, his sadism, and his aggressive sexual appetites.

On the whole, I’m not sure that this complicated flashback structure serves the film well. At times it is strikingly symmetrical, as when a scene of Lee returning from Shenzhen on the train is followed by a distant flashback of the marriage, and this is closed off by a shot of Ling and her daughters traveling on the same train. At other points, though, the relation between the witness’s testimony and the flashback episodes is arbitrary, with the flashbacks showing scenes unrelated to that witness’s knowledge of the family drama.

It seems to me as well that the power of the events leading up to Lee’s murder of his family is vitiated by the protracted Mainland visits, widening the film’s field of view to life in Sichuan and Ling’s family. Where My Dear Enemy lets its backstory emerge in piecemeal fashion through hinting dialogue, dramatizing every relevant moment in Ling’s past seems to lose some focus.

Likewise, there’s a certain fuzziness about the film’s main thrust. Is it a character study, trying to explain why Lee is violently jealous and why Ling stays with him? The only clear answer I could determine was her sense of indebtedness for his help to her parents. Is Night and Fog then best taken as a critique of the Hong Kong bureaucracy? The social workers are portrayed as indifferent or unable to understand domestic violence. But in that case we need to see more of the mechanisms of decision-making than we do, and then many of the intimate relations of the couple would be extraneous. The battered women’s shelter, while not unblemished, becomes the opposite pole to Ling’s dangerous household, and Huipresents it as a safe space where women can express their feelings spontaneously. But again, this angle on the material seems vitiated by bringing in a public protest against real-estate development of the harbor area—an important issue, but in the context a bit distracting.

The film seems to me to excel in areas that Hong Kong cinema has made its own: extreme emotion and sheer physicality. The violence of Lee’s assaults on his family are terrifying, and Simon Yam’s performance is tremblingly ferocious. Smoking furiously, swigging cans of beer, Yam gives us Lee Sum as a figure on the edge of destruction. He makes even fishing seem an act of aggression. Lee’s incessantly jiggling leg is like the timer on a pressure cooker, and when he sits down with his son from a previous marriage—a sleepy-eyed young pimp—the two of them share the same foot-jiggling tic. In this shot, Hui gives us a diagram of male aggression ready to burst.

If My Dear Enemy trades on suspense, Night and Fog creates dread. One is roundabout, the other more direct; one suggests much, the other shows everything. Two ways, we might say, of making modern cinema.

More, including another Iranian masterpiece, in my next communiqué.

Night and Fog.

Beyond praise 2: More DVD supplements that really tell you something

Kristin here-

In September of 2007 I posted the first “Beyond praise” entry, the idea being that I would recommends DVD supplements that didn’t just contain a lot of participants in the filmmaking process gushing about how wonderful their colleagues were. Such supplements would reveal something about the filmmaking process, and perhaps something about the publicizing and exhibition as well.

I intended to make this a regular feature of the blog, so it’s high time to post a follow-up entry. These comments don’t necessarily deal with very recent releases. Some are a few years old by now. Still, I’ve just caught up with them, and they haven’t lost their interest for film buffs, teachers, and students.

Collateral (“Two-disc Special Edition,” DreamWorks Video)

The making-of, “City of Night: The Making of Collateral,” is short by current standards, at about 39 minutes. It’s dense with information, though. Indeed, David and I were inspired by it, along with the account of the film’s making in American Cinematographer, to add a case study on the film’s production to Film Art. The 9th edition, coming in December, will start with this case study and how the aesthetic decisions made by the filmmakers affected the final film. (One of the book’s users suggested this idea, and we think the result improves the opening chapter.)

Michael Mann wanted to capture the unique glow of Los Angeles at night, caused by the bright lights of its flat grid being reflected by the atmosphere over the city. To do so, he employed digital cameras for most scenes. The documentary shows how the cameras allowed filming almost entirely with ambient light. (See illustration below.) Fill light was added subtly by innovative flexible panels Velcro-ed onto the interior of the cab that forms a major setting for the action. One suspenseful scene near the end was filmed in a darkened office, with the actors becoming completely black silhouettes against the lights of the city outside the windows. For those who may not be familiar with professional-level digital filming, this making-of offers a succinct introduction. Collateral remains one of the best films shot primarily with digital cameras, and it makes a good case for the new technology for those who may doubt that it can ever be as effective as 35mm film.

“City of Night” also has the best demonstration I’ve seen of the use of multiple cameras to shoot a big action scene, detailing how the spectacular taxi crash was planned and executed. (But see also the 3:10 to Yuma description below.) There’s an interesting segment on the music, where composer James Newton Howard talks about composing the music for the extended climactic chase in “three movements.”

There’re also some rehearsal footage and other minor supplements, but the main documentary is far and away the most informative. It could be quite useful for teaching cinematography.

Hellboy (“2-Disc Special Edition,” Columbia Tristar Home Entertainment) and Hellboy II: The Golden Army (“3-Disc Special Edition,” Universal Studios Home Entertainment)

Guillermo del Toro being the geeky fanboy that he is, the supplements for the two Hellboy films are lengthy and full of solid information. The first film was made on a smaller budget, as was its main making-of, “Hellboy: The Seeds of Creation.” Essentially it alternates candid footage captured on working sets, which is really more decorative than informative, with interviews and segments on specific topics. There’s a little of everything one would expect for an effects-heavy film: bits on maquettes, set models, testing of stunts, animatronic figures, and so on. Cinematographer Guillermo Navarro talks briefly about lighting tests for Hellboy, accompanied by such beautiful images as the one above, imitating the vivid, high-contrast look of the original comic.

The making-of contains nice little segments that superimpose a digital double on raw footage (at about 29:30 minutes), a good illustration of building a CG figure by adding musculature to a wire-frame base (70 min.), and a more detailed treatment of ADR than most supplements offer.

The making-of for the sequel, “Hellboy: In Service of the Demon,” is more extensive and was evidently planned  more thoroughly. One early scene has del Toro seated on the floor having a decidedly informal meeting with his design staff. It’s clearly a real, working meeting, not one staged for the camera. The director has some intelligent things to say about the monsters he wants from his team (“No aliens!”), and his voice continues over shots of the designs that the people sitting with him came up with. There’s a great deal of material on the design and construction of the famously large number of demons, 32 in all, as well as on-set demonstrations of how the elaborate costumes are worked by the actors inside them and by remote control.

more thoroughly. One early scene has del Toro seated on the floor having a decidedly informal meeting with his design staff. It’s clearly a real, working meeting, not one staged for the camera. The director has some intelligent things to say about the monsters he wants from his team (“No aliens!”), and his voice continues over shots of the designs that the people sitting with him came up with. There’s a great deal of material on the design and construction of the famously large number of demons, 32 in all, as well as on-set demonstrations of how the elaborate costumes are worked by the actors inside them and by remote control.

Highlights: a good explanation of how points of control are added to CGI creatures and function to create the final image; another on how motion-control is used for special effects; a view of a video-assist playback. Particularly impressive is the lengthy scene in which we watch the make-up for the Angel of Death being designed and applied while actor Doug Jones talks intelligently about the make-up and the character.

The supplement is long, about two and a half hours, but I think I’d choose it, or at least big portions of it, if I wanted to teach about special effects to an introductory class. Like Peter Jackson, GDT is a big advocate of using practical effects whenever possible and resorting to CGI only when they aren’t possible. As a result, this making-of demonstrates an unusually wide range of kinds of effects. It’s also entertaining, clear, and has interviews with most of the principals involved in each kind of task.

3:10 to Yuma (Lionsgate)

The supplements for James Mangold’s Western (the sound mixing of which David blogged about here) are less lavish but still of interest. There’s a section on how the four major sets were constructed on location rather than in sound stages. One detailed segment shows a camera rig for moving with a stagecoach and the practical special effects used for the scene in which the coach is  flipped over. I learned, for example, that “crash cam” is the name for the metal cylinder used for the camera most likely to get hit by the flipping vehicle-a device also on view in the Collateral supplements. The crash scene is particularly well done, showing the shooting with multiple cameras and then immediately the crash as edited.

flipped over. I learned, for example, that “crash cam” is the name for the metal cylinder used for the camera most likely to get hit by the flipping vehicle-a device also on view in the Collateral supplements. The crash scene is particularly well done, showing the shooting with multiple cameras and then immediately the crash as edited.

There are bits of out-of-the-way but fascinating information here. For example, there are companies that rent old trains for film production. There are also guns that shoot dust capsules (left) into the set to simulate bullet impacts and other bits of flying debris. Apart from the main documentary, there’s a six-minute segment, “An Epic Explored,” where Mangold talks about making a Western in a period when the genre is out of fashion, and a brief history of “Outlaws, Gangs and Posses” that could be useful for background information on Westerns in general.

The Golden Compass (“New Line 2-Disc Platinum Series,” New Line Home Entertainment)

I was interested in The Golden Compass from its inception, since it was New Line’s intended replacement for The Lord of the Rings as the studio’s prestige franchise. That didn’t work, of course. (I wrote about how New Line copied its Rings strategies in promoting The Golden Compass here and about why the film succeeded abroad but not in the U.S. here.)

As an admirer of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy, I was also curious about how well the lengthy, complicated first novel could be adapted for the screen. My impression upon seeing the film was that the first half raced along, presenting essentially a brief summary of each scene and trying to cram in exposition about the huge number of characters and plot points retained from the novel. The second half calmed down and was more successful in its rendering of events.

The Golden Compass was a failure from New Line’s point of view-and that of parent company Time Warner, which used that failure as an excuse to fold the semi-independent studio into Warner Bros. It made about $372 million internationally, but the overseas take was $302 million of that total. That money stayed with the foreign distributors, who had helped finance the film through pre-sales of rights. That and its reported $180 million budget meant that New Line lost a bundle.

The DVD supplements reflect nothing of these problems. They’re distinctly better than the lackluster titles of the individual segments suggest. There’s a nice section on the novel, with Pullman saying some interesting things. “The Adaptation” mostly depends on interviews with director Chris Weitz and producer Mark Ordesky. Throughout the supplements, Weitz, who was relatively inexperienced when he took on the epic production, is not only modest but downright self-deprecating-sort of the opposite of too much praise. (“The fact of the matter is that there have been hundreds of people working on this just as hard as I have, and this is not the kind of film that really fits in with a kind of an auteur theory of filmmaking.”) Perhaps the director will feel more confident on his next project, the sequel to Twilight.

The makers of the supplements chose an effective tactic of choosing one major item in each category to concentrate on, rather than trying to cover every aspect of casting, design, and so on.

“Finding Lyra Belaqua” seemed to promise the usual uninformative gushing about how wonderful Dakota Blue Richards was in the lead role. In fact it’s quite an interesting account of how open casting calls work. The casting team have calls in multiple towns, where enthusiastic little girls in the queues explain their fascination with the project. The casting of Richards must have become pretty likely at some point, since the documentarists followed the young actress and her mother through a string of call-backs and the tense process of whittling the short-list down.

The “Daemons” section spends minimal time on explaining the concepts and instead concentrates on the design, the creation of maquettes for CGI work, and the necessary but rather silly use of stuffed animals on the set to stand in for the daemons. The section on how Freddie Highmore had to dub in Pantalaimon’s dialogue in ADR while watching unrendered computer images of his character is particularly interesting.

Again, a fairly lengthy session devoted to the design and making of “The Alethiometer” (15 minutes on a single prop) is not simply devoted to explaining what it is. Instead, it gives a real sense of the elaborate process of seeking real-world models, finding experts create for each type of part needed, and making the prototype. The section on production design focuses on the use of conflicting shapes as motifs throughout the film: circles for Oxford, Lyra, and the Alethiometer, ovals for Mrs. Coulter and the Magisterium. These show up in vehicles, sets, and props:

Other segments are similarly clever and informative: on how costumes affected the way the actors had to walk; on the steps used to create the entirely CGI-based armored-bear battle; on the music’s use of exotic instruments to characterize the various imaginary ethnic groups. There’s even a segment on the Cannes press-junket launch, with a brief interview with a junket producer-something I certainly haven’t seen in a supplement before.

I had hoped to be able to recommend the supplements for Across the Universe. Julie Taymor’s musical is so imaginative and appealing that one would expect some clever and original making-ofs as well. Unfortunately most of the five brief documentaries fall into the mutual-praise trap (“Everyone wants to work with her!”). “Stars of Tomorrow” is 27 minutes of guff about how the young actors were cast and how wonderfully they fit their roles. “Moving across the Universe,” on the choreography, is pretty good-but only 9 minutes long. The best things in the supplements are the clips from the film. Watch it, skip the extras.

Niceties: how classical filmmaking can be at once simple and precise

DB here:

A film academic once complained that I was too preoccupied with “formalistic niceties.” So here I go again. But read no further if you haven’t seen Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige.

Dueling magicians: The film’s premise might be considered high-concept. In turn-of-the-century London, two young conjurers launch their careers with different attitudes toward their craft. Robert Angier favors audacious showmanship, while Alfred Borden is committed to finding a trick that will baffle the experts. Their rivalry is ignited when Alfred accidentally kills Angier’s wife during a dangerous underwater stunt. Their struggle peaks around each one’s supreme trick: transporting himself from one point to another instantaneously.

The item that attracts my attention today is established in the film’s opening sequence. As the voice of Cutter (Michael Caine) explains a magic trick’s three acts, we see a climactic confrontation between the competitors. Hoping to discover Robert’s secret, Alfred watches the Real Transported Man performance from the audience.

As Cutter’s narration mentions “a man,” the camera picks out Alfred in the crowd. Cut to Robert onstage, a shift that establishes the two as our protagonists.

What interests me is the view of the bearded Alfred: a medium-shot framing him nearly in profile facing right. This framing will be repeated, but varied, when Alfred’s voice-over diary entry introduces both him and Robert as apprentices, working as audience shills for another magician:

We were two young men at the start of a great career—two young men devoted to an illusion, who never intended to hurt anyone.

The new shot parallels the introduction of Alfred in the first scene, but varies it. Again we see Alfred in the audience, but now without a beard, and the camera tracks rightward to show Robert in another row.

In this sequence, our protagonists are connected by a camera movement rather than the cut employed in the opening. The two men’s reactions—Robert grinning (his wife is onstage), Alfred more pensive—add to the characterizations that we will see played out.

This simple camera motif gets varied further in the course of the film. The disastrous immersion illusion that drowns Robert’s wife is initiated by another tracking shot of the two men in the audience, a variation of the earlier shot.

The new combination starts with Robert and ends on Alfred. At this point, not only are the two men linked but they replace one another. If you want to push your luck, you could say that this variant quietly affirms the film’s overall dynamic of substitution (doubles, twins, clones).

Earlier, a contrasting way of showing the men in an audience is given us when they attend a performance of the wizard Chung Ling Soo. Cutter provides a dialogue hook, warning Robert that “the blokes at the ends of row three and four” can see him kissing his wife’s leg.

Cut to our protagonists, sitting at the end of a row watching the Chinese magician.

A nicety: Now the men are sitting side by side and facing left rather than right. Just through camera placement and character position, we know we’re in a different performance, one in which our apprentices play no role.

As they study the trick, Nolan gives us another characterizing shot: Robert is amazed, but Alfred grins: He’s worked out Chung’s secret.

What would have happened if Nolan had framed the men sitting apart and/or facing to the right? For an instant we might have thought we were back in the act they shill for. Simple but reiterated differences assure immediate comprehension: medium shot/ long shot, looking rightward/ looking leftward, men in different rows/ men in the same row. Just as the repeated framings of their own act clarify the situation, so do these little polarities. Call it redundancy, if you like, but it’s also precision and economy.

With Julia’s death, the men become enemies. But each will still slip into the audience of the other’s performances. From now on, the magician is always on the right, the onlooker on the left. Nolan and company could have handled their rivalry in camera setups that exactly mimic the early ones. Instead, a new pattern of parallels comes into play, building on the earlier ones but different enough to heighten the symmetries.

The new pattern is set up by restricting our range of knowledge. First, we are attached to Alfred when he performs his bullet catch in a barroom theatre. Robert, seeking vengeance for Julia’s drowning, steps up to spoil the trick, but we don’t know he’s there until Alfred does, and then it’s too late.

Similarly, we’re restricted to Robert’s range of knowledge when he tries to execute his disappearing dove trick. Only when Alfred is about to trigger the collapsing cage—killing the dove and wounding a lady from the audience—does Robert realize that his adversary has struck back.

Another nicety: The two shots of each man in similar disguises, seen in 3/4 view, reset the stylistic parameters. But the image of the bearded Alfred is given extra punch through a tilt up from his missing fingers–the result of the parallel, bullet-catch scene before.

The whole pattern shifts yet again when Robert sneaks in to watch Alfred’s Transported Man illusion. We get a shot of him (in a beard again) that fuses two of the cues from the earlier scenes: He’s in the audience, as in the early sequences, but he’s shown from an angle congruent with that of the earlier beard shots.

And perhaps we can take the shot of Robert at home, telling of his amazement at Alfred’s illusion, as an echo of the initial prototype: A magician staring intently rightward at a dazzling trick played out offscreen, but now in memory.

Robert returns from Colorado with the Tesla-designed “Real Transported Man,” and Alfred’s visit to watch the stunt reworks the givens of this pattern yet again. Alfred is seated, minimally disguised, in the standard audience spot looking right, but he is not in profile and the camera position is much closer than before. The answering shot of Robert onstage recalls the gesture we saw at the film’s outset and anticipates what we will see when that opening scene is replayed, with the wicked Alfred climbing onstage.

At the close of the trick, yet one more variant: Robert appears in the rear balcony and the crowd all turns to watch him off left.

After a glance back, Alfred turns away, looking right–the first time any character has flinched from the performance. His puzzlement is mixed with anger (at last a trick he can’t see through), a less charitable response than we saw in Robert’s stunned fireside recollection of Alfred’s Transported Man.

The things held constant, such as camera placement and position in the locale, set off the differences in characters’ disguises and reactions, while this shot carries faint echoes of our very first view of Alfred during Cutter’s voice-over monologue. That view, and its answering shot of Robert in the spotlight, will recur when Robert’s pseudo-death is replayed.

Nolan’s audacious film is built out of more marked parallels than these, but I wanted merely to highlight the ups and downs of one small pattern. Many films work varied repetitions like these into their shot-by-shot texture. Back in the 1930s, Eisenstein saw this possibility clearly, as I try to show in my book on his work. In the 1960s and 1970s, Raymond Bellour called our attention to such patterns in films by Hitchcock, Hawks, and Minnelli. His collection of essays The Analysis of Film includes pioneering studies of how fine-grained such things can become.

I wouldn’t go as far as Bellour does in seeing varied repetition as the motor force of classical filmmaking, but it surely plays an important role. What he takes as a manifestation of pure textual difference I’m inclined to psychologize: these differences help the audience understand, usually without awareness, the ongoing narrative dynamic and have the extra payoff of creating tacit narrative parallels. But from either perspective, object-centered or response-centered, studying such microforms is enlightening. It’s a way to understand films as wholes, dynamic constructions that shift their shapes across the time of their unfolding. Moreover, by examining things this closely, we can try to understand not only how this or that film works, but how this or that film relies on principles distinctive of a filmmaking tradition. Consider this another plug for poetics.

I’d add that such principles neatly fuse two pressures: toward narrative coherence and comprehension on the one hand, and toward production efficiency on the other. It’s cheaper and easier to repeat camera setups if you can. Artistic economy and financial economy can work together, nicely.

Speaking of repetitions….