Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

Showing what can’t be filmed

DB, again:

People tend to think that documentary films are typified by two conditions. First, the events we see are unstaged, or at least unstaged by the filmmaker. If you mount a parade, the way that Coppola staged the Corpus Christi procession in The Godfather Part II, then you aren’t making a documentary. But if you go to a town that is holding such a procession and shoot it, you are making a doc—even though the parade was organized to some extent by others. Fiction films stage their events for the camera, but documentaries, we tend to think, capture spontaneous happenings.

Secondly, in a documentary the camera is seizing those events photographically. The great film theorist André Bazin saw cinema’s defining characteristic as its capacity to record the actual unfolding of events with little human intervention. All the other arts rely on human creation at a basic level: the novelist selects words, the painter chooses colors. But the photographer or filmmaker employs a machine that impassively records what is happening in front of it. “All the arts are based on the presence of man,” Bazin writes; “only photography derives an advantage from his absence.” This isn’t to say that cinema can’t be artful, only that it offers a different sort of creativity than we find in the traditional arts. The filmmaker works not with pure imaginings but obstinate chunks of actual time and space.

Given these two intuitions, unstaged events and direct recording of them, it would seem impossible to consider an animated film as a documentary. Animated films consist of almost completely staged tableaus—drawings, miniatures, clay, even food or wood shavings (in the works of Jan Svankmajer). And animated movies offer no recording in Bazin’s sense of capturing the flow of real time and space. These films are made a frame at a time, and the movement we see onscreen doesn’t derive from movement that occurred in reality. And of course you can make an animated film without a camera, for instance by painting directly on film or assembling computer-generated imagery.

Recently, however, we’ve been faced with animated films that claim documentary validity. How is this possible? Maybe we need to rethink our assumptions about what documentary is.

In certain types of documentaries, especially those in the Direct Cinema or cinéma vérité traditions, the assumption that we’re seeing spontaneously occurring events holds good. But a documentary can consist wholly of staged footage. Think back to those grade-school educational shorts showing a tour of a nuclear power plant. Every awkward passage of dialogue recited by the hard-hatted, white-coated supervisor was scripted. The whole show was planned and rehearsed, but that doesn’t detract from the factual content of the film.

Go further. Recall those attack maps that are shown in war films, tracing the progress of an army through enemy terrain. Now imagine an entire film made of those animated maps. The maps might even be enhanced with a few cartoon images, as in the above shot from one of the Why We Fight films. The film would be entirely designed, presenting no spontaneous reality being captured by the camera. Yet it would plainly be a documentary, telling us that, say, the Germans marched into the Sudetenland in 1938 and proceeded on to Poland. So we don’t need photographic recording of actual events to count a film as a documentary either. Both the staging and the recording conditions don’t have to be present for a film to count as a documentary.

I’m not saying that the claims advanced in my nuclear-power film or my attack-map movie would necessarily be accurate. They might be erroneous or inconclusive or false. But that possibility looms for any documentary. The point is that the films, presented and labeled as documentaries, are thereby asserting that the claims and conclusions are true.

Film theorist Noël Carroll defines documentary as the film of “purported fact.” Carl Plantinga makes a similar point in saying that documentaries take “an assertive stance.” Both these writers argue that we take it for granted that a documentary is claiming something to be true about the world. The persons and actions are to be taken as representing states of affairs that exist, or once existed. This is not something that is presumed by The Gold Rush, Magnificent Obsession, or Speed Racer. These films come to us labeled as fictional, and they do not assert that their events and agents ever existed.

This isn’t just a case of a professor stating something obvious in a fancy way. Once we see documentary films as tacitly asserting a state of affairs to be factual, we can see that no particular sort of images guarantees a film to be a doc.

Take the remarkable documentaries made by Adam Curtis. These are in a way very old-fashioned. Blessed with a voice whose authoritative urgency makes you think that at last the veils are being ripped away, Curtis mounts detailed arguments framed as historical narratives. Freudian theory shaped the emergence of public relations, which was in turn exploited not just by business but by government (Century of the Self). Islamic fundamentalism grew up intertwined with US Neoconservatism, both being reactions to perceptions that the West was becoming heartlessly materialistic (The Power of Nightmares). Mathematical game theory came to form politicians’ dominant conception of human behavior and civic community (The Trap). The almost uninterrupted flow of Curtis’s voice-over commentary could be transcribed and published as a piece of nonfiction. True, there are some interpolated talking heads, but those experts’ statements could be printed as inset quotations.

What’s particularly interesting is that Curtis’ rapid-fire declamation accompanies images that often seem not to illustrate it, or at least not very firmly. Like the found footage in the preacher’s sermon “Puzzling Evidence” in True Stories, Curtis’ images are enigmatic, tangential, or metaphorical.

Here are a few seconds from the start of The Power of Nightmares. Eyes are staring upward, as if possessed.

We hear: [Our politicians] say that they will rescue us from dreadful . . .

The eyes are replaced by a shot of a man wearing a cowl, and as this image zooms back the commentary continues.

. . . dangers that we cannot see and do not . . .

Cut to a magician or mime demanding silence.

. . . understand.

Cut to rockets being fired.

And the greatest danger . . .

Cut to a procession of cars, seen from above, rounding a corner into a government compound at night.

. . . of all is international terrorism.

Cut to shot of security agent staring at us.

The ominous, not to say paranoid, tenor of the sequence is aided by the unexpected juxtapositions. For instance, you’d think that the shot of the iconic terrorist (anonymous, with automatic weapon) would be synchronized with the final line of the commentary, referring to “international terrorism.” Instead the commentary links the mention of terrorism to an image of government deliberation, and then to an image of surveillance (aimed at us, but also perhaps suggesting the previous high-angle shot was the spy’s POV). The wild-eyed close-up might belong to a terrorist, but is accompanied by claims about rescuing us from fearsome threats, so the eyes could also belong to someone panicked–especially since they contrast immediately with the sober eyes of the gunman in the cowl. Perhaps the first shot represents the fearful public ready to be led by the politicians playing on fear. And the insert shot of the mime becomes sinister but also comic, perhaps debunking the official position that our dangers are unseen and unknowable. In all, the sequence bubbles with associations that are less fixed and more ambiguous than we’re likely to find in a more orthodox documentary, like Jarecki’s Why We Fight.

My point isn’t to analyze the image/ sound relations in Curtis’s work, a task that probably demands a whole book. (This sequence takes a mere eleven seconds.) I simply want to propose that regardless of what pictures Curtis shows, his films are documentaries in virtue of a soundtrack constructed as a discursive argument that makes truth claims. The picture track often works on us less as supporting evidence than as a stream of associations, the way metaphors or analogies give thrust to a persuasive speech.

Just as we could have an account of Germany’s 1938 invasion of Czechoslovakia presented in cartoon form, we could imagine The Power of Nightmares illustrated with political cartoons. Once we’ve pried the image track loose from the assertions on the soundtrack, anything goes.

One example much on our minds now is Waltz with Bashir. Ari Folman interviews former Israeli soldiers. But instead of using film footage of their conversations and, say, still photos of the events in Lebanon they took part in, he provides (until the final sequence) drawings a bit in the Eurocomics mold of Tardi or Marc-Antoine Mathieu. The result takes the form of a memoir, admittedly. But in both literature and cinema, memoir is a nonfiction genre.

Another memoir supports the point. Marjane Satrapi’s autobiographical graphic novels, Persepolis and Persepolis 2, assert factual claims about her life. The claims are presented as drawings and texts rather than simply as texts, but that doesn’t change the fact that she presents agents and actions purported to have existed. True, on film the people whom she remembers are represented through voice actors speaking lines she wrote. But as with written memoirs (especially those that claim to remember conversations taking place fifty years ago), we can always be skeptical about whether the events presented actually took place.

Another memoir supports the point. Marjane Satrapi’s autobiographical graphic novels, Persepolis and Persepolis 2, assert factual claims about her life. The claims are presented as drawings and texts rather than simply as texts, but that doesn’t change the fact that she presents agents and actions purported to have existed. True, on film the people whom she remembers are represented through voice actors speaking lines she wrote. But as with written memoirs (especially those that claim to remember conversations taking place fifty years ago), we can always be skeptical about whether the events presented actually took place.

Turning Satrapi’s published memoir into an animated film did not change its status as a documentary. If we had contrary evidence, we could charge her with fibbing about her family life, her rebelliousness, or her life in Europe. But we’d be questioning the presumptive assertions the film makes, not the fact that it is drawn and dubbed rather than photographed from life.

We’re tempted to see the animation in these films as adding a level of distance from reality. We’re so used to fly-on-the-wall documentaries that we may be suspicious of the cobra-like caricatures of the female teachers in Persepolis or the hallucinatory dawn bombardment in Bashir. Yet animation can show things, like the Israeli veterans’ dreams, that lie outside the reach of photography. And the artificiality doesn’t dilute the claims about what the witnesses say happened any more than does purple prose in an autobiography. In fact, the stylization that animation bestows can intensify our perception of the events, as metaphors and vivid imagery in a written memoir do.

I realize I’m pointing toward a slippery slope here. Strip off the image track from Aardman‘s Creature Comforts and you have impromptu recordings of ordinary people talking about their lives. Those monologues could have been accompanied by documentary-style talking heads. Does that make Creature Comforts a documentary? I’d say not because the film doesn’t come to us labeled that way; it’s presented as comic animation using found soundtracks (like the movie based on the Lenny Bruce routine Thank You Mask Man). Then there are Bob Sabiston‘s rotoscoped films like Waking Life and The Even More Fun Trip, recently released on Wholphin no. 7. The latter (left) takes another documentary form, the home movie, as the basis for its animation. This seems to me an instance where the documentary category has the edge, but it’s a surely a borderline case.

I realize I’m pointing toward a slippery slope here. Strip off the image track from Aardman‘s Creature Comforts and you have impromptu recordings of ordinary people talking about their lives. Those monologues could have been accompanied by documentary-style talking heads. Does that make Creature Comforts a documentary? I’d say not because the film doesn’t come to us labeled that way; it’s presented as comic animation using found soundtracks (like the movie based on the Lenny Bruce routine Thank You Mask Man). Then there are Bob Sabiston‘s rotoscoped films like Waking Life and The Even More Fun Trip, recently released on Wholphin no. 7. The latter (left) takes another documentary form, the home movie, as the basis for its animation. This seems to me an instance where the documentary category has the edge, but it’s a surely a borderline case.

Animated documentaries are likely to remain pretty far from our prototype of the mode. Still, we should be grateful that even imagery that seems to be wholly fictional—animated creatures—can present things that really happen in our world. This mode of filmmaking can bear vibrant witness to things that cameras might not, or could not, or perhaps should not, record on the spot.

André Bazin’s arguments for the documentary basis of cinema are set out in “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” in What Is Cinema? ed. and trans. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), 9-16. Noël Carroll’s argument that documentaries are framed as presenting “purported fact” can be found in Theorizing the Moving Image (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 224-259. On the “assertive stance” of documentaries, see Carl Plantinga, Rhetoric and Representation in Nonfiction Film (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 15-25. Errol Morris interviews Adam Curtis here. Thanks to Mike King for pointing me toward The Even More Fun Trip.

PS 10 March: Harvey Deneroff writes:

Very much enjoyed your post on animated documentaries, a topic of some interest to and often discussed in the animation studies community. There was a panel on it during last year’s Society for Animation Studies conference and there will also be one at this year’s as well.

Two recent Oscar recipients for Best Animated Short Subject are also documentaries: Chris Landreth’s wonderful computer animated Ryan (produced by the NFB about animator Ryan Larkin, and features a lot of talking heads) and John Canemaker’s The Moon and the Son: An Imagined Conversation, which is about Canemaker’s father and mixes animation with home movies and photographs.

At least two winners in the Oscar Documentary Short Subject category were largely animated: Chuck Jones’ So Much for So Little (WB, 1949, which I believe was made for the US Public Health Service) and Norman McLaren’s Neighbours. The Story of Time, a 1951 British documentary which featured stop motion animation was nominated in the same category.

Also, the International Leipzig Festival for Documentary and Animated Film includes a section for animated documentary films.

Thanks to Harvey for this. I’m not sure I’d categorize Neighbours as a doc, but it’s a long time since I’ve seen it. On Harvey’s site he also has a note quoting Ari Folman on the difficulty of funding animated docs. And thanks to Ryan Kelly and Pete Porter for reminding me of Winsor McCay’s Sinking of the Lusitania from 1918.

Acting up

Germinal (1913).

DB here:

Film performance is notoriously difficult to analyze. We don’t lack zesty celebrations of actors; I think especially of Richard Schickel on Doug Fairbanks and Gary Giddins on Jack Benny and Bob Hope (praised in an earlier entry). But we have long found it difficult to penetrate actors’ secrets with the same precision that we bring to editing or framing or a film’s musical score.

Actors’ performances don’t offer themselves in neat slices, the way that shots come to us. There isn’t a firm notational system that lets us capture performances the way that scores can pick out important patterns in music.

Moreover, it’s hard to dissect something that seems so evanescent, so direct, and so natural. When we see someone smile on the bus or at a party, we react immediately and without any apparent thought. When someone smiles in a movie, we’re tempted to say that we respond just as directly. But then, what is acting? Just doing what comes naturally?

Acting is clearly an art and a craft. Not everyone can do it, and comparatively few do it well. So if there is a skill or a technique involved, surely acting goes beyond ordinary behavior. And if as in other arts there are creative choices involved, there is likely to be a menu of options to be chosen from. Some of those options are likely to be conventions sanctioned by tradition. How strongly, then, is acting conventionalized? If it’s conventionalized to some degree, we should be able to analyze it.

A small-scale debate has gone on for some years in film studies about whether film acting is heavily conventionalized, even coded. Advocates of the coding view point to the fact that acting styles vary in different places and change across time. What does Kabuki performance have in common with Method acting? It’s hard to claim that there is a universally realistic acting style that naturally represents human behavior. Against this, others have argued that even if there is no absolute and unchanging standard of realism, we can speak of more or less realistic aspects of performance. Some styles, like Method are just less artificial than others, like Kabuki—even if both are somewhat stylized with respect to realistic behavior.

My own view, explored in Poetics of Cinema, is that performance traditions streamline or stylize a common core of widely shared human behaviors. In everyday life, smiling expresses happiness and/or serves as a social signal of openness. We’re unlikely to find a distant culture in which smiling expresses rage. (Of course we can have an instance of smiling concealing rage, but that would acknowledge the difference between the two states.) Some acting traditions, like Kabuki, retain certain common behaviors like weeping or proud walking, but make them more dancelike. Other acting traditions stylize core behaviors in different ways–the mumble of the Method, or the comic double-take. The differences lie in what aspects of facial expressions, gestures, gait, and the like are on the tradition’s menu, and how they become “streamlined” for expressive purposes and spectatorial uptake.

In short, I’m a moderate constructivist about such matters. I agree that we have to learn to comprehend performances in different traditions. But our learning is fast and spontaneous, not at all like learning Morse code or English, because we already have strong hunches about what a frown or a wail might express. Frowning or wailing are likely to be contingent universals of human behavior. An intuition about the meaning of the performance guides us to recognize the more stylized aspects of the presentation. When Cesare coasts along walls in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, we take that to be a stylized representation of the act of stalking. That construal relies on the hunch that he’s doing something we already understand–stalking–in an unusual way. Although sometimes we might have to revise our intuitions about the meaning, those intuitions serve as a point of departure. (Where do our intuitions ultimately come from? Short answer: The evolution of humans as a social species.) E. H. Gombrich put it well: “It is the meaning which leads us to the convention and not the convention which leads us to the meaning.”

Assunta Spina (1915).

The faculty and alumni of the Film Studies program here at Wisconsin keep in touch through a (closed) listserv, and thanks to Jonathan Frome we also have a wiki, to be found here. It’s just starting to fill up, mostly with ideas for teaching and examples of sample sequences to illustrate film techniques. But now the wiki has gained striking essays on acting from two scholars of early cinema.

Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs’ book, Theatre to Cinema, took on the problem of what early feature films owed to the stage, and they concluded: Quite a lot. But instead of condemning this tradition as “uncinematic,” as most historians have, they showed that a highly engaging form of cinema arose by reshaping theatrical traditions. Specifically, Ben and Lea examined how “situational” plotting principles were carried into film, and they discussed film’s debt to the “pictorialist” drama of the nineteenth century. Many scholars had argued that melodramatic theatre was replaced by the Naturalist theatre, derived from the literary movement associated with Émile Zola. But Lea and Ben argued that a pictorialist conception of theatre and its modified form in early feature films cut across this distinction. A film that was avowedly Naturalist in plot or theme could maintain conventions of earlier forms.

Consequently, they argued that film acting of the period, even when it seemed to be moving toward greater realism, was still building on the stereotyped expressions, gestures, and attitudes of pictorialist theatre. Actors were called upon to execute vivid stage tableaus. Standard gestures had to be imbued with fresh emotional intensity, and actors were expected to move gracefully from one expressive picture to another.

Now Ben and Lea have extended their book’s argument in two in-depth studies posted on the UW wiki. Ben’s essay examines that great Capellani film Germinal (1913) and shows that it often perpetuates the poses and expressions of pictorialism, while also scaling them down. Lea tackles the work of the diva Francesca Bertini, including an analysis of the wonderful Assunta Spina (1915). Her piece is a companion to Ben’s. She writes:

While I do not doubt that the plot of Assunta Spina fits under the rubric of naturalism, and that the acting and staging of some scenes in the film also show the influence of naturalism in the theatre, it seems to me that Bertini’s technique (and incidentally that of [Asta] Nielsen as well) is more reminiscent of Bernhardt than it is of the Duse, and that the blocking and use of gesture in the film is largely governed by what Brewster and I have discussed in terms of “pictorialism” in acting.

By considering 1910s performance as a modification of theatrical poses, attitudes, and staging conventions, Jacobs and Brewster are led to remarkably detailed analyses. They have studied the conventions of acting at that period, and because they are alert to standard bits of business, so they are able to show fine points of performance that we would ordinarily miss.

They’re also able to hold the realism/ artifice dispute in suspension by concentrating on particular historical traditions. They shrewdly note that as acting styles change, the newer one is likely to be praised as more realistic than the styles it supplants. In turn, that style will be considered artificial when a still newer one comes along. For this reason, Method acting may seem less realistic and more artfully contrived today than it did in the 1950s.

Apart from the subtle discussion of acting styles, one merit of these essays is that they recognize how films can take bits and pieces of different traditions and modify them for particular ends. I’m sympathetic to this perspective. For instance, I still think that many of today’s Hollywood films, despite their contemporary look and feel, draw on principles of narration and plot structure that we can find in classic American studio cinema.

In addition, you ought to visit the site to see how detailed their analyses are and how extensively they draw on frame stills. Indeed, one reason they published these pieces online was that no academic film journal could have accommodated so many illustrations. So much the better for us. The frames, taken from 35mm prints with a Nikon lens and negative film, are among the most beautiful you’ll find on the Internets. I swiped some here.

Sangue bleu (1914).

The quotation from E. H. Gombrich comes from his essay “Image and Code: Scope and Limits of Conventionalism in Pictorial Representation,” in The Image and the Eye: Further Studies in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1982), 289.

Kristin has written a couple of blog entries concentrating on performance, here and here.

Coraline, cornered

DB here:

It’s common for academics in one field to borrow ideas from other domains of research. But people outside academe sometimes object when a film scholar talks about movies using a term or idea originating elsewhere. These people usually think of themselves as hard-headed pros. Everything we need to understand film, they think, can be derived from the concepts already used by practitioners.

No doubt, we should be attentive to the ways in which filmmakers think and talk about their work. There’s a lot to be learned from shop talk and insider information–hence the enduring value of interviews, DVD commentaries, and the like. Yet no activity explains itself. Often practitioners do things intuitively, without making their background ideas explicit. We can often illuminate a filmmaker’s creative choices by spelling out the unspoken premises behind the work.

Further, filmmakers themselves have traditionally drawn ideas from other arts and sciences. For example, storytelling techniques referred to as exposition, point of view, or motivation have their origin in theories of literature and drama. Filmmakers have been quite pluralistic in their creative practices; why can’t critics and historians be open to outside influences?

Back in the 1980s I began speculating on how the film image represented space, and I adopted the then-current terminology of perceptual psychology. Researchers spoke of depth cues, those features of the real world that prompt our visual system to make fast inferences about a three-dimensional layout. Classic depth cues are the Gestalters’ figure/ ground relation, da Vinci’s “atmospheric perspective” (the haze that envelops more distant planes), and Helmholtz’s “kinetic depth effect,” the way that when you’re moving, closer objects change at a different rate than more distant ones.

These features can also be invoked in two-dimensional images, as I tried to show in Narration in the Fiction Film. Nowadays, deeper explanations of these effects are available using geometrical or computational approaches to perception. But depth cues remain a useful informal way of studying how artists manipulate images. For this reason, in Film Art: An Introduction, we’ve continued to itemize some depth cues that are important in cinema. These concepts furnish analytical tools for understanding things that filmmakers do spontaneously when they compose or light a shot.

So imagine my happiness when I hear filmmakers talk directly about depth cues.

In a fascinating article in American Cinematographer, Pete Kozachik, Director of Photography on Coraline, explains that the filmmakers were very conscious of perceptual factors throughout, and not just in creating the stereoscopic effect. For example, they designed and filmed our heroine’s alternative world in normal perspective, but her boring normal world was designed to seem off-kilter and flat by means of inconsistent depth cues within the shots. “The compositions match in 2-D, but the 3-D depth cues evoke a different feel for each room.”

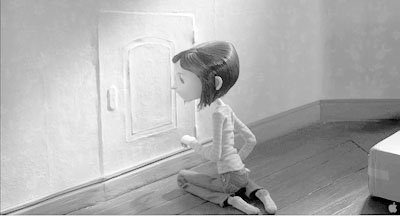

This is hard to illustrate in a two-dimensional medium, but the Coraline trailer offers some examples. Consider this image.

The tiles in the family shower don’t recede into the distance, either across or upward. They are more or less the same size, just arrayed along a diagonal. A degree of recession is supplied by tonality and lighting, but the corner of the shower stall remains somewhat ambiguous. If you try to do a Gestalt flip, you can see the corner as a chimney poking out at you rather than one receding inward. (To see this, try covering the rest of the shot with your hands.)

In the garden of the “Good Household,” however, the bricks recede naturalistically in shape and size. The lighting and tonal gradients create a strong sense of depth.

Here is the Good Family’s hallway.

It displays central perspective, with everything receding as it should (as if seen by a wide-angle lens).

By contrast, here is an oblique shot of Coraline’s real-world bedroom. The doorway’s edges recede pretty steeply, but the baseboard doesn’t taper as it moves toward and past the corner. Instead, it moves in parallel lines. The same thing is happening with the floor planks.

You can see the effect more clearly if we drain the color and lower the contrast. (Sorry, Messrs. Selick and Kozachik.)

Now you can also see the weird, almost cubistic edges of floorboards poking up just behind the carton. Again, lighting and tonality create a sense of depth that the geometry of the edges denies. The depth cues within Coraline’s normal life are inconsistent.

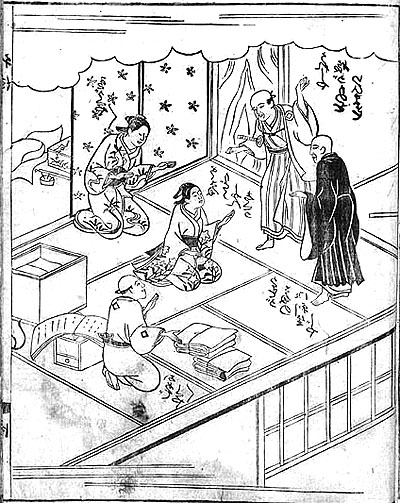

Stare at the rear stretch of the baseboard awhile, and you’ll find that its contours may look a bit wider than those in the foreground. This sort of “parallel perspective” can be found throughout Asian art. Here is a Japanese book illustration from 1713, in which many of the edges run in parallel perspective. Again, instead of meeting in the distance, diagonals seem to be converging out in front of the picture plane, making some areas appear wider in the rear than in the front.

If my invocation of other artistic traditions seems a highfalutin way of talking about an animated movie, check the Van Gogh joke in the Coraline frame at the bottom of this entry.

Kozachik also explains how he spent a lot of time trying to vary the two images’ interocular distance, the distance between our two eyes, in order to give a greater sense of volume. The care paid off, at least for me. Coraline is the best 3D film I’ve seen, as well as the scariest. (For our take on Beowulf see this entry.)

In addition, Coraline helps me push a general point: Cinema is at least partly an affair of perception. Filmmakers are practical psychologists, artists who have mastered the skill of playing with our senses. We can open up their secrets a little by using tools borrowed from the sciences of mind.

For more on Coraline, see Bill Desowitz’s Animation World interview with Tadahiro Uesugi and his interview with Henry Selick. Background on the production is supplied by Thomas J. McLean’s article from last year.

For an overview of spatial perception, see Maurice Hershenson, Visual Space Perception (MIT Press, 1999). A more detailed account is Stephen E. Palmer, Vision Science: Photons to Phenomenology (MIT Press, 1999). A geometrical explanation of the kinetic depth effect is offered in James E. Cutting, Perception with an Eye for Motion (MIT Press, 1986).

An old-fashioned, sentimental avant-garde film

Kristin here–

A great many silent films that were almost impossible to see when David and I were in graduate school are now available on DVD. And it’s not just a matter of titles becoming available. In those days we might be able to see a classic film, but it was likely to be a shortened, fuzzy version made from a worn distribution print. Now government support for film archives and revenues from home video have promoted many more restorations. There are still companies releasing poor-quality DVDs of silent films, but beautiful prints, complete with tinting, toning, hand-coloring, and specially composed musical tracks, as well as supplementary material, are becoming more common.

A case in point is the new DVD version of Abel Gance’s 1922 epic, La roue (“The Wheel”), which the enterprising company Flicker Alley released last year. In its short existence since 2002, Flicker Alley has done exciting work. Its recent “A Modern Musketeer” collection finally makes a selection of Douglas Fairbanks’ pre-swashbuckler comedies and dramas available. I personally prefer these lively, witty, imaginative films to Fairbanks’ 1920s costume pictures. Flicker Alley’s George Méliès set is one of the great achievements of DVD production and deservedly won last year’s prize for the best silent DVD set at Il Cinema Ritrovato. Other highlights include F. W. Murnau’s rare psychological drama Phantom (1922) and Louis Feuillade’s serial, Judex (1917). I wrote about Flicker Alley’s release of Discovering Cinema, on early sound and color.

David and I first saw La roue in 1973, in a 16mm print at George Eastman House. It lasted around two hours projected at sound speed. We had another chance to see it at a 1979 screening of a 35mm nitrate print at the Museum of Modern Art. Again, it was a truncated version. In short, you had to see La roue at an archive.

The restoration

The original 32-reel version would have run between seven and eight hours. That doesn’t survive, but versions longer than the ones we had seen survived in various collections. A more common release version made in the 1920s reduced the film to 12 reels, or about three hours. Other still shorter versions also circulated.

Flicker Alley’s version is none of these. The liner notes say that it’s 20 reels, and it runs about 260 minutes. (The total time given on the box is 270 minutes, which I assume includes an eight-minute making-of supplement.) So what we have here is not an approximation of one of the release prints, but an attempt to reassemble as much footage as possible.

Here’s what Flicker Alley’s press release said about the restoration:

La Roue was originally shown in France over three days, in 32 reels, with a running time of almost eight hours, but was soon shortened to 12 reels, the maximum length for a typical feature film at the time. This new restoration, produced by Eric Lange, David Shepard and Jeff Masino with invaluable support from Turner Classic Movies, began with a 35mm master positive of this 12-reel version, a Russian print of an 8-reel version, two incomplete tinted nitrate prints of a longer French version, and finally, for two short but critical scenes, a 4-reel abridged version released by Pathe on 9.5mm for home movie screening. Conflating all of this material, the Lobster Film Studios restoration team headed by Eric Lange was able to prepare and digitally restore a 20-reel version, by far the most complete edition of La Roue seen anywhere since 1923. This release possesses exceptional pictorial quality and English titles that use the type font and moving photographic backgrounds of the original film.

The notes call this restoration “the fullest presentation of La Roue to reach the public since 1923,” which may or may not be true. I have seen a print of La roue of roughly the same length which has a significant number of scenes that aren’t present in the Flicker Alley release-and lacks several of the scenes included here. That was at the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, though they don’t hold the original material on it; that’s in a French archive. That version runs 287 minutes at 18 frames per second; I can’t find an indication of projection speed on the DVD, though I would guess that it’s comparable.

I definitely don’t want to suggest that the Flicker Alley DVD is not worth buying or viewing. Quite the contrary, it’s a valuable release of an extremely influential and important film. Perhaps a longer version will eventually be assembled, but I doubt that will happen any time soon. Those who have been waiting for years to see La roue should pounce on this, and it’s ideal for instructors who want to show clips of highly influential sequences in classes.

The visual quality of the print is mostly excellent, apart from a few passages where the restorers had to use a 9.5 mm print to fill in a few scenes–and even those look pretty good. Blue tinting is used in the night scenes, and the film is accompanied by Robert Israel’s effective score.

Gance’s innovations

[SPOILER ALERT]

Gance has many ardent admirers, to judge by the effusive reviews of the DVD on Amazon. But I find his major silent features a maddening blend of exciting stylistic innovation and old-fashioned, maudlin storytelling. La roue was, as far as we know, the first film to use rapid, rhythmic editing, at times going down to single-frame images. It’s also full of the subjective camera techniques typical of French Impressionist filmmaking: out-of-focus shots, white masks, superimpositions, and so on.

The plot, however, is simple and melodramatic; it centers on Sisif, a train engineer, and his secret adopting of a little girl who survives a train wreck in the opening scene. Norma grows up assuming herself to be his daughter, and Sisif’s son Elie, a sensitive violin-maker, believes her to be his sister. Sisif falls in love with her but stifles his feelings, giving her in marriage to a rich man whom she doesn’t love. When Elie learns the truth, he comes to love her as well but also hides his secret. A great deal of suffering ensues, over which Gance lingers lovingly with many shots of agonized faces.

Most famous are three scenes. The film’s action begins dramatically with the train crash, vividly rendered in many fairly quick shots. In the second, Sisif decides to crash the train in which Norma is traveling to her marriage. Even faster, accelerating editing conveys both Sisif’s anguish and Norma’s growing alarm. It’s a bold and suspenseful scene, and required viewing for anyone interested in silent cinema and the history of film style. The second passage comes after a fight between Elie and Norma’s husband that ends with Elie dangling from a tree root over a cliff. As he hears Norma approaching in an attempt to save him, their life  together literally flashes before his eyes in a series of shorter and shorter shots that end with a flurry of single-frame images that end with his fall.

together literally flashes before his eyes in a series of shorter and shorter shots that end with a flurry of single-frame images that end with his fall.

Much of the imagery is also beautiful, in particular the shots of trains passing sinuously along rails, a motif that punctuates the film.

These innovative scenes and other flashy techniques tended to be retained as distributors cut out more and more footage. What got trimmed seems to have been details of the quadruple romance plot. Scenes in the Belgian print that aren’t on the DVD include two brief ones indicating that the husband’s fortunes are declining. This sets up for the moment when Norma is revealed to have been left destitute after his death, a development that comes abruptly in the DVD version. The Belgian print also contains a rather silly scene in which Sisif talks to his train engine and imagines it replying to him.

Modern viewers may find it a bit disconcerting that the interior scenes of Sisif’s small house, built between the rails in a real train-yard, are lit with bright sunlight. Immediately after World War I the French film industry was short on studios and lighting equipment. Using open-air sets and full sunlight was not uncommon there or in countries with small film industries.

A brief but valuable bonus

Most films of this era did not have making-of documentaries. In this case, though, poet Blaise Cendrars, a great cinema enthusiast, filmed some scenes of Gance and his team at work and put together a fascinating short. A couple of shots show the camera used to film the tavern scene mounted on a dolly.

One view reveals just how close to the rails the sets for Sisif’s house were built. Trains passed so close to them that someone had to be stationed nearby to warn the crew of oncoming trains. Cendrars also recorded a visit Charles Pathé paid to the location, and there’s a heroic view of the director in the cab of a moving locomotive. This film has hitherto been très rare, so we are lucky to have it now.

The booklet accompanying the discs has an excellent essay on the history of the production by William M. Drew and notes by Israel on his score.

David insisted on having the photo at the bottom included among the illustrations. Gance appeared at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis when he was 91 years old, which means that must have been in 1980. He had come to introduce a screening of Bonaparte and the Revolution, an early attempt to restore Napoléon vu par Abel Gance. At a reception afterwards, M. Gance was gracious enough to inscribe a photo and our copy of a book he had published in the 1920s, purchased back in the days when one could still find such things fairly readily in Parisian used bookshops. He also let David take a picture of him and me. He died the following year.

Note: Filmmaker and blogger Kevin Lee has created two more of his “Shooting Down Pictures” video analyses, with me speaking about La roue (five minutes) and Variety (six minutes) to clips Kevin has edited.