Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

Lucky ’13

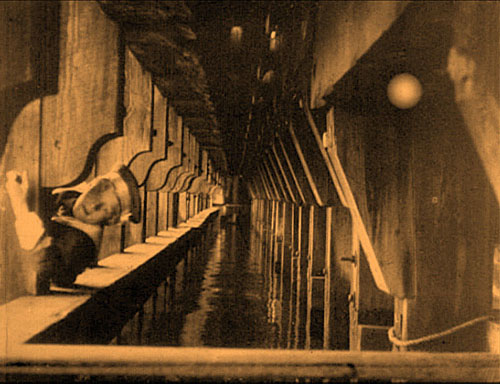

The Mysterious X (1913).

Each film is interlocked with so many other films. You can’t get away. Whatever you do now that you think is new was already done in 1913.

Martin Scorsese, quoted in Scorsese by Ebert (University of Chicago Press, 2008), 219.

DB here:

Most historical events don’t abide by clocks and calendars. Seldom does a trend begin neatly on one date and end, full stop, on another. Changes have vague origins and diffuse destinies. When Kristin and I, along with others, argued for 1917 as the best point to date the consolidation of the Hollywood style of storytelling, we realized that it’s a useful approximation but not as exact as a Tokyo subway timetable.

It’s just as hard to argue that a year constitutes a meaningful unit in itself. Who expects anything but tax laws to change drastically at midnight on 31 December? Yet evidently our minds need benchmarks. Film historians, while being aware that trends are slippery and dating is approximate, have long spotlighted certain years as particularly significant.

Take 1939, which has become a sort of emblem of the peak achievements of Hollywood’s Golden Age. We had Gone with the Wind, The Wizard of Oz, Only Angels Have Wings, Stagecoach, Gunga Din, Wuthering Heights, Dark Victory, Young Mr. Lincoln, Beau Geste, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Ninotchka, The Roaring ‘20s, and Destry Rides Again. I’d watch any of those, except Gone with the Wind, right now—something I find it hard to say about most Hollywood movies I’ve seen in 2008.

Another strong year is 1960, with La Dolce Vita, L’Avventura, Rocco and His Brothers, The Apartment, Elmer Gantry, Spartacus, Psycho, Exodus, The Magnificent Seven, Shadows, Late Autumn (Ozu), and The Bad Sleep Well (Kurosawa). Arguably, 1960 was owned by the French, who gave us Breathless, Shoot the Piano Player, Paris nous appartient, Les Bonnes femmes, Le Trou (Becker), Moi un noir (Rouch), and Letter from Siberia (Marker). (See Postscript.)

Let’s go back still further. Researchers sometimes split the silent-film period in two, with the first stretch, usually called “early cinema,” running up to 1915 or so. (1) The second phase then runs roughly from 1915 to 1928. (2) So for many historians the year 1915 functions as a tacit pivot-point, and it is remembered not only for The Birth of a Nation but also for Regeneration, The Tramp, Kindling, The Cheat, Les Vampires, Daydreams (Yevgenii Bauer), and several William S. Hart films. But another year holds a special place in the minds of silent film aficionados.

Over a decade ago, the annual Days of the Silent Cinema festival (Il Giornate del cinema muto), took 1913 as its focus. (3) It was an extraordinary year. Denmark produced Atlantis (August Blom) and The Mysterious X (Benjamin Christensen). From France we had L’Enfant de Paris (Leonce Perret), Germinal (Albert Capellani), and Louis Feuillade’s Fantomas series. Germany gave us Urban Gad’s Engelein and Filmprimadonna and Franz Hofer’s obsessively symmetrical The Black Ball. The staggering set of Italy’s Love Everlasting (Ma l’amor mio non muore!, Mario Caserini) was matched by the breadth of Enrico Guazzoni’s Quo vadis? In Russia Bauer released Twilight of a Woman’s Soul. American audiences saw Traffic in Souls (George Loane Tucker) and Death’s Marathon and The Mothering Heart, from a guy named Griffith. Several historians would argue that 1913 marked the first major achievements of film as an artform.

Two outstanding films of that annus mirabilis have recently been issued on US DVD. One is a striking accomplishment, the other a flat-out masterpiece. Both discs belong in the collections of everyone who’s serious about cinema.

Your call is important to us

A wife and her baby are alone in an isolated house when a tramp breaks in. As the wife tries to keep the invader at bay, her husband happens to telephone and learn what’s happening. He scrambles to return home. He steals an idle car, and its owner, accompanied by police, race after him. We cut rapidly between the besieged mother and the husband’s frantic drive, as he is in turn pursued. Just as the tramp is about to attack the wife, the husband bursts in, followed by the police. The family is saved.

This is the story of the 1913 one-reel film, Suspense, co-directed by Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley. If the plot sounds familiar, it’s probably because you know that one of D. W. Griffith’s most famous films, The Lonely Villa (1909) tells the same basic tale.There are still earlier versions, including one, The Physician of the Castle (Le Médécin du chateau, 1908), which may have inspired Griffith. The ultimate source seems to be a 1902 play by André de Lord, Au téléphone (translated here).

So Weber and Smalley are reviving an old idea. Their task is to make it fresh. How they do so has been studied in depth by Charlie Keil in his book Early American Cinema in Transition: Story, Style, and Filmmaking, 1907-1913.I can’t match Keil’s subtlety, and it’s better that you see the film first, so I’ll drop only some hints, pointers, and comments.

We’re inclined to say that The Lonely Villa influenced Suspense. But maybe we can capture the situation in a more illuminating way. The art historian E. H. Gombrich has suggested that we can often trace the relationship between artworks in terms of schema and revision. (4) A schema is a pattern that we find in an artwork, one that a later artist can borrow. Most often, later artists copy the schema straightforwardly. This is the usual way we think of influence. But instead of replicating the schema, the next artist can revise it. She can elaborate on it, strip it to its essence, drop parts and add others, whatever—in order to achieve new purposes or evoke fresh responses.

In The Lonely Villa, Griffith uses crosscutting to build suspense. He cuts among the thuggish vagrants trying to break in, the wife and daughters trying to hold them off, and the father learning by phone of the situation and then plunging after them with a policeman. The obvious pattern here is the principle of alternation between different lines of action, all taking place at the same time and converging in a last-minute rescue.

So Smalley and Weber inherit the crosscutting schema, but they go beyond simply copying it. They find ways to revise it, some quite surprising. These revisions aim to create more tension and to dynamize the situation.

The obvious option, at least to us today, would be to use more shots than Griffith does; we think that increasing the cutting pace builds up excitement. Interestingly, however, Suspense uses only a couple of more shots than The Lonely Villa within a comparable running time. (5) We usually expect that American films become more rapidly cut as the 1910s go on, but this isn’t the case here. Shortly, I’ll suggest why.

Smalley and Weber recast Griffith’s parallel editing in several ways. For instance, The Lonely Villa prolongs the phone conversation between husband and wife, building suspense through the husband’s instruction to use his revolver on the thugs. Suspense, by contrast, doesn’t dwell on the telephone conversation but devotes more time (and shots) to the chase along the highway. That’s because Weber and Smalley have complicated the chase by having the husband pursued by the irate motorist and the police, something that doesn’t happen in the Griffith film.

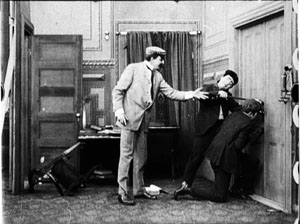

Just as important, Smalley and Weber revise the crosscutting schema through framings that are quite bold for 1913. For example, Griffith’s tramps break into the house in long shot, and they move laterally across the frame.

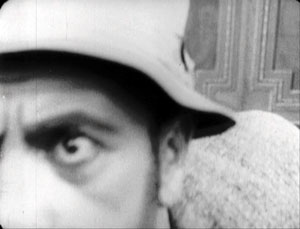

But Weber and Smalley’s tramp sneaks steadily up the stairs, into a menacing extreme close-up.

Elsewhere, Suspense gives us close views of the wife and of the door as the tramp breaks in. There are oblique angles on the back door of the house, and virtually Hitchcockian point-of-view shots when the wife sees the tramp breaking in and he looks straight up at her.

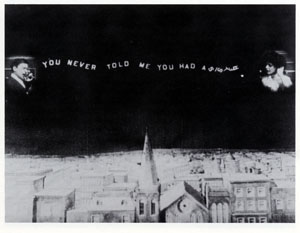

What struck me most forcibly on watching the film again was the way in which Weber and Smalley’s daring framings serve as equivalents for parallel editing. In effect, they revise the crosscutting schema by putting several actions into a single frame. The most evident, and the most famous, instances are the triangulated split-screen shots. They cram together three lines of action: the wife on the phone, the husband on the phone, and the tramp’s efforts to break into the house (here, finding the key under the mat). (6)

Split-screen effects like this were common enough in early cinema, especially for rendering telephone conversations. Eileen Bowser points out that the three-frame division was one variant, with a landscape separating the two callers. (7) Her example is from College Chums (1907).

But my sense is that in early cinema the split-screen effect was used principally for exposition or comedy, not for suspense. Smalley and Weber have made this framing substitute for crosscutting: instead of giving us three shots, we get one, showing the plot advancing along different lines of action. These splintered frames function much like Brian De Palma’s multiple-frame imagery in Sisters, Blow-Out, and other films. There’s also the nice touch of the conical lampshade over the husband’s head, providing a fulcrum for the composition.

Earlier in the film, instead of crosscutting between the tramp outside and the wife indoors, Suspense gives us both in the same shot, with the tramp peeking in behind her.

A more ingenious revision of the crosscutting schema comes during the shots on the road. Instead of cutting between the father in the stolen car and the police pursuing him, Suspense packs them into the same frame. This is done not only in long shot but also in striking depth compositions.

Flashiest of all are the shots showing the pursuers reflected in the rear-view mirror of the father’s car as he races ahead of them.

Again, a single framing has done duty for two shots, one of the father looking back and another showing the cops coming closer to him. By compressing several lines of action into a single frame, our 1913 film doesn’t need to use significantly more shots than the 1909 one.

These are just a few of the imaginative ways in which Weber and Smalley have recast their standard situation. I could have considered as well the unobtrusive use of the knife as a multi-purpose prop, the echoed shots of mirrors, and the shrewd employment of repetitions in the intertitles.

It would take an early-cinema specialist like Keil to trace out all the connections between Suspense and other films of its era. One among many would be the fact that Griffith wasn’t exactly standing still between 1909, the year of The Lonely Villa, and 1913. For instance, his Battle at Elderbush Gulch, made about the same time as Suspense (though released in 1914), displays far more rapid cutting than Weber and Smalley attempt. Griffith also employed a swelling advance to the foreground, like that of the tramp shot I showed above, in The Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912).

Here, Smalley and Weber seem to have replicated a schema that was believed to ratchet up tension, the so-called looming effect.

The very title of the film exhibits self-consciousness about its artistic purpose. By 1913, it seems, American filmmakers were confident enough in their skills to announce their aims. We want, the title seems to say, to arouse you, to make you wait, hanging there, for the resolution. We know how to tell a twelve-minute story cinematically. The film seems uncannily to anticipate all those one-word titles that Hitchcock invoked to unsettle us–Suspicion, Spellbound, Psycho, Frenzy. As in a Hitchcock movie, the fact that we are pretty certain how Suspense will turn out doesn’t seem to dissipate our anxiety. (For more on this paradox of suspense, see this entry.)

Tunnel vision

It was during the Pordenone 1913 season that the full brilliance of Victor Sjöström’s Ingeborg Holm hit me. I had seen the film a couple of times before and found it deeply moving in its restrained treatment of a poignant situation. The film traces the dissolution of a family. Sven Holm is doing a brisk retail business, but his health problems, along with a thieving clerk, plunge the family into poverty. When Holm dies, his wife Ingeborg must take the children into the poorhouse, and from there they are boarded out to foster families. Her plight worsens over the years, and its sorrowful depths are revealed when her son, now grown, returns to visit her.

Ingeborg Holm has long been recognized as a milestone in European film, not least for its effect on improving Sweden’s treatment of the poor. (8) The acting style is muted and delicate, with no mugging or arm-waving. For long periods, the main actors turn from the audience. (9) Just as impressive are the poised compositions, sustained in unhurried long takes. These give what is essentially a bourgeois tragedy a kind of majestic relentlessness. Watching, I remembered what Dreyer had admired in Sjöström’s Ingmar’s Sons (1918):

The film people here at home shook their heads because Sjöström had really a boldness to let his farmers walk heavily and soberly as farmers do. Yes, they used up an eternity to come from one end of the room to the other. (10)

But sitting in the Cinema Verdi in 1993, I spotted yet another level of artistry. Knowing the story of Ingeborg Holm, I was able to watch the shots unfold. I could study how Sjöström was unobtrusively moving characters so that they became shifting centers of interest. Although he didn’t cut in to close-ups, he harmonized his actors’ movements so that at one point you noticed Ingeborg, at another her husband. Performers spread themselves across the frame, arrayed themselves in depth, turned from or toward the camera. Most subtly of all, one actor might mask another one, driving our attention to other parts of the frame. Sjöström could sustain this intricate play of blocking and revealing for minutes on end.

My favorite example of this tactic is the three-minute passage showing Ingeborg’s daughter and son taken away by new mothers. You can read the whole discussion on pp. 191-195 in On the History of Film Style (1997), but here is an excerpt, with stills intercalated. (These stills, grabbed from the DVD, lack a little on the left. The film has been printed and reprinted so many times, and now fitted to the TV monitor, that it has lost some information along that edge.)

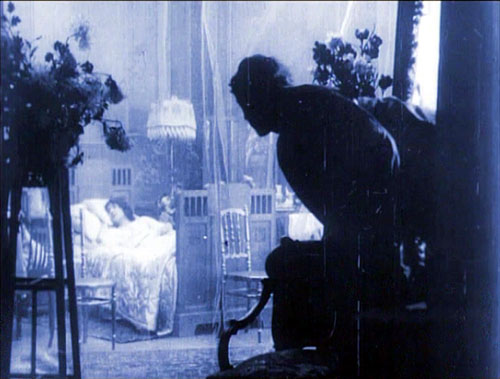

Ingeborg’s entry with her children from the rear doorway establishes the trajectory that will be followed during the scene, as foster mothers come in and take away the children. (Again, the scene is built around movements toward and away from the camera.) In a brilliant stroke, Sjöström immediately plants the young son in the foreground, back to us. The boy will stand there immobile for this first phase of the scene, occasionally serving to block the superintendent.

Ingeborg buries her face in her daughter’s shoulder at the precise moment the foster mother enters from the rear left. She passes behind Ingeborg, and as she is momentarily blocked, the superintendent twitches into visibility, handing the woman a document to sign.

During the signing, when the woman is briefly obscured, the superintendent shifts position again and Ingeborg lifts her face once more. Then Ingeborg and her daughter move slightly leftward as the foster mother comes forward.

This phase of the scene concludes with the departure of the daughter and the embrace of Ingeborg and her son in the foreground, once more concealing the superintendent.

Granted, I picked one of the film’s most exactingly staged scenes, but there are several other examples. Consider the climax, when the adult son comes to visit Ingeborg: the camera position and staging ask us to recall the scene I’ve just mentioned. Or take a look at the handling of the space behind the counter in the various scenes in the Holms’ shop. One instance surmounts this section.

This choreography is hard to catch on the fly: by the time you notice a change, what prepared for it has gone. To understand the overall dynamic, we must reverse-engineer the effects, moving backward from the result to the conditions. As I studied the film, it became clear that creating shifting centers of interest was basic to the scenes’ effects. All the finesse of acting, both solo and ensemble, would come to little if we weren’t primed to watch the most important area of the shot. Directors of the 1910s became supremely skilful in guiding our eye from one major story point to another within the fixed frame.

Some of the tactics of guiding our attention could be borrowed from other arts. Painting and theatre supplied certain schemas, like placing an item in the center of the picture format and turning faces toward the viewer. But some tactics for directing our eye relied on capacities that were as “specifically cinematic” as cutting was argued to be. Theatre is staged for many sightlines, but cinema is staged for a single one, that of the camera lens. That fact allowed directors to organize the unfolding action in depth, prompting the viewer to notice things at many distances from the camera.

It also allowed a precise blocking and revealing of information that would not work on the stage. In a live theatre performance, the slight shifts we detect in the Ingeborg Holm scene would be apparent to only very few viewers; people sitting in other vantage points wouldn’t see them. For another example of this phenomenon, go elsewhere on this blogsite.

There’s a more basic explanation of what’s going on. Cinematic space is a result of optical perspective, like the space of classic painting. The actors may seem to be standing in a cubical space, but in fact they move within a tipped-over pyramid, with the tip resting at the camera lens. They work inside a ground area that’s the shape of a slice of pie. Here’s a reminder from The Black Ball.

When there are figures close to the camera, as here, they fill up more of the frame, indicating that the field of view has narrowed. Filmmakers of the 1910s had discussed this property of their “cinematic stage,” so as researchers we can confirm that the control of position and timing we observe on screen results from the firm intentions of the makers. They might have echoed Uccello, the Renaissance artist who bent over his drawings late at night and exclaimed: “How sweet a thing is this perspective!”

Suddenly the tableau tradition made sense to me. Directors had to organize both the two-dimensional composition and the tapering three-dimensional playing space in front of the camera. The purpose was to create ever-changing centers of interest, laterally and in depth, flowing along with the key moments in the unfolding action.

By studying the same tactics in Feuillade, Bauer, and others, I found that these principles offered a fruitful way to understand much of what was happening in the films of the tableau era. The dynamic of schema and repetition/revision was at work as well, since I found earlier, more rudimentary uses of these principles; these were then refined during the 1910s. Moreover, the idea helped me generalize beyond that era and analyze later directors, including Mizoguchi Kenji and Hou Hsiao-hsien, who also used staging to shape the viewer’s experience. The results can be found in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light. Those books largely owe their existence to that flash of awareness kindled by Ingeborg Holm. (11)

We can’t reconstruct Sjöström’s stylistic development with much confidence. (12) His first directed film, The Gardener (Trädgärdsmästaren, 1912) survives, but I saw it before I knew how to watch 1910s movies in this way, so I can’t comment on it. Of the twenty-six films he made from 1912 to 1917, nearly all have been lost. Apart from Ingeborg, I have managed to see Havsagamar (The Sea Vultures, 1916). This retains aspects of the tableau tradition, but virtually no scenes display the intricate staging of his 1913 masterpiece.

In the late 1910s, judging by the films we have, Sjöström seems to have moved quickly toward continuity editing in the American vein. (13) The Girl from Stormycroft (Tösen frän Stormyrtorpet, 1917) contains extended passages of analytical editing, and the scenes display a freedom of camera setup one seldom sees in European cinema of the period. Sjöström clearly understands the principles of continuity down to the smallest detail. For instance, he not only uses the frame-edge cut (the cut that lets a character exit one shot and enter another, as the body crosses the frameline); he accelerates it. Our heroine leaves the kitchen, and in the shot’s final frame she hits the right edge. Another director would have had her exit the frame entirely and held the kitchen shot a little longer, to give her time to get to the next room. But Sjöström simply cuts to her already in another room, completing her trajectory.

Sjöström presumes that the constant pace of her approach and the vector of her movement will smooth the shot-change. It does, but few directors of that day would had such confidence that our mind would create continuity of motion.

During this summer’s archive viewing, I spent some time studying Sjöström’s cutting in The Girl from Stormycroft and subsequent films. I may offer some more thoughts later. For now I’ll just say that in these early years we seldom encounter such a versatile director, one who mastered the tableau tradition and then moved, with apparently little effort, to nuanced continuity editing. More generally, examining his technique isn’t a dry exercise. We never lose by studying craftsmanship. Sjöström’s films succeed because his style carefully guides our moment-by-moment apprehension of the heart-rending stories he has chosen to tell.

Have I convinced you to surrender your credit-card number? Suspense is available in a dazzling Flicker Alley collection, Saved from the Flames, compiled from the French series Retour de flame. Ingeborg Holm comes with a tinted print of the estimable Terje Vigen (A Man There Was) on a DVD from Kino. The latter disc includes vibrant scores from Donald Sosin and David Drazin.

(1) For the purposes of the outstanding Encyclopedia of Early Cinema (New York: Routledge, 2005), the editor Richard Abel considers that the early cinema constitutes the period from film’s invention ca. 1894 to the mid-1910s.

(2) Silent films were still made into the 1930s, notably in Russia and Japan—a situation that shows the rough-and-ready quality of period divisions.

(3) For an informative series of articles around the 1913 theme, see Griffithiana no. 50 (May 1994).

(4) Gombrich proposes these ideas at various points in Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation, new ed. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000). The book is a milestone in twentieth-century humanistic inquiry.

(5) The Lonely Villa (1909) has, in the version I’ve seen, 54 shots in a 750-foot reel (that is, about twelve and a half minutes at 16 frames per second). Suspense has nearly the same number of shots, 56, in about the same running time.

(6) Sharp-eyed readers will recognize one of these shots as Fig. 5.82 in Film Art: An Introduction, 8th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008), 187.

(7) Eileen Bowser, The Transformation of Cinema 1907-1915, vol. 2 of History of the American Cinema (New York: Scribners, 1990), 65.

(8) For more background on the film, see Jan Olsson, “‘Classical’ vs. ‘Pre-Classical’: Ingeborg Holm and Swedish Cinema in 1913,” Griffithiana no. 50 (May 1994), 113-123.

(9) Kristin wrote about this technique in “The International Exploration of Cinematic Expressivity,” in Film and the First World War, ed. Karel Dibbets and Bert Hogenkamp (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1995), 65-85. She also discusses it in our Film History: An Introduction, 2d ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), 67.

(10) Carl Dreyer, “A Little on Film Style,” Dreyer in Double Reflection, ed. and trans. Donald Skoller (New York: Dutton, 1973), 133.

(11) I was probably primed for this by lectures presented by Yuri Tsivian, who has long been studying mirrors in 1910s cinema and calculating how they revealed offscreen space.

(12) Detailed information on Sjöström’s relation to the film industry in these years can be found in John Fullerton’s epic Ph. D. thesis, The Development of a System of Representation in Swedish Film, 1912-1920 (University of East Anglia, 1994). See also Fullerton, “Contextualising the Innovation of Deep Staging in Swedish Film,” Film and the First World War, ed. Dibbets and Hogenkamp, 86-96.

(13) Several people have analyzed Sjöström’s editing. Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs’ Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 133-136 shows how cutting supports the acting in a crucial scene of Ingmar’s Sons. Tom Gunning’s essay “‘A Dangerous Pledge’: Victor Sjöström’s Unknown Masterpiece, Mästerman,” in John Fullerton and Jan Olsson’s anthology Nordic Explorations: Film before 1930(Sydney: John Libbey, 1999), 204-231, argues that Sjöström’s cutting gives his characters a degree of psychological opacity. Most recently, in an unpublished paper Jonah Horwitz discusses patterns of performance, composition, and editing in Terje Vigen (1917).

Twilight of a Woman’s Soul (1913).

PS 31 August: Some corrections. David Cairns writes to point out that the triangle at the top of the frame in the Suspense split-screen isn’t a lamp but simply the shade behind the father’s head, cropped by the masking. Wishful thinking on my part, I’m afraid. By the way, David has an intriguing movie giveaway going on his site.

Roland-François Lack corrects dates on two of my Greatest French Hits from 1960: “The great Marker from that year is Description d’un combat, not Lettre de Sibérie (1958), and likewise Rouch’s Moi un noir is from 1958.” Thanks to him and David. To my original list, I should probably have added Cocteau’s Testament d’Orphée, released in 1960.

Superheroes for sale

DB here:

After a day at the movies, maybe I am living in a parallel universe. I go to see two films praised by people whose tastes I respect. I find myself bored and depressed. I’m also asking questions.

Over the twenty years since Batman (1989), and especially in the last decade or so, some tentpole pictures, and many movies at lower budget levels, have featured superheroes from the Golden and Silver age of comic books. By my count, since 2002, there have been between three and seven comic-book superhero movies released every year. (I’m not counting other movies derived from comic books or characters, like Richie Rich or Ghost World.)

Until quite recently, superheroes haven’t been the biggest money-spinners. Only eleven of the top 100 films on Box Office Mojo’s current worldwide-grosser list are derived from comics, and none ranks in the top ten titles. But things are changing. For nearly every year since 2000, at least one title has made it into the list of top twenty worldwide grossers. For most years two titles have cracked this list, and in 2007 there were three. This year three films have already arrived in the global top twenty: The Dark Knight, Iron Man, and The Incredible Hulk (four, if you count Wanted as a superhero movie).

This 2008 successes have vindicated Marvel’s long-term strategy to invest directly in movies and have spurred Warners to slate more comic-book titles. David S. Cohen analyses this new market here. So we are clearly in the midst of a Trend. My trip to the multiplex got me asking: What has enabled superhero comic-book movies to blast into a central spot in today’s blockbuster economy?

Enter the comic-book guys

It’s clearly not due to a boom in comic-book reading. Superhero books have not commanded a wide audience for a long time. Statistics on comic-book readership are closely guarded, but the expert commentator John Jackson Miller reports that back in 1959, at least 26 million comic books were sold every month. In the highest month of 2006, comic shops ordered, by Miller’s estimate, about 8 million books (and this total includes not only periodical comics but graphic novels, independent comics, and non-superhero titles). There have been upticks and downturns over the decades, but the overall pattern is a steep slump.

Try to buy an old-fashioned comic book, with staples and floppy covers, and you’ll have to look hard. You can get albums and graphic novels at the chain stores like Borders, but not the monthly periodicals. For those you have to go to a comics shop, and Hank Luttrell, one of my local purveyors of comics, estimates there aren’t more than 1000 of them in the U. S.

Moreover, there’s still a stigma attached to reading superhero comics. Even kitsch novels have long had a slightly higher cultural standing than comic books. Admitting you had read The Devil Wears Prada would be less embarrassing than admitting you read Daredevil.

For such reasons and others, the audience for superhero comics is far smaller than the audience for superhero movies. The movies seem to float pretty free of their origins; you can imagine a young Spider-Man fan who loved the series but never knew the books. What’s going on?

Men in tights, and iron pants

The films that disappointed me on that moviegoing day were Iron Man and The Dark Knight. The first seemed to me an ordinary comic-book movie endowed with verve by Robert Downey Jr.’s performance. While he’s thought of as a versatile actor, Downey also has a star persona—the guy who’s wound a few turns too tight, putting up a good front with rapid-fire patter (see Home for the Holidays, Wonder Boys, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, Zodiac). Downey’s cynical chatterbox makes Iron Man watchable. When he’s not onscreen we get excelsior.

Christopher Nolan showed himself a clever director in Memento and a promising one in The Prestige. So how did he manage to make The Dark Knight such a portentously hollow movie? Apart from enjoying seeing Hong Kong in Imax, I was struck by the repetition of gimmicky situations–disguises, hostage-taking, ticking bombs, characters dangling over a skyscraper abyss, who’s dead really once and for all? The fights and chases were as unintelligible as most such sequences are nowadays, and the usual roaming-camera formulas were applied without much variety. Shoot lots of singles, track slowly in on everybody who’s speaking, spin a circle around characters now and then, and transition to a new scene with a quick airborne shot of a cityscape. Like Jim Emerson, I thought that everything hurtled along at the same aggressive pace. If I want an arch-criminal caper aiming for shock, emotional distress, and political comment, I’ll take Benny Chan’s New Police Story.

Then there are the mouths. This is a movie about mouths. I couldn’t stop staring at them. Given Batman’s cowl and his husky whisper, you practically have to lip-read his lines. Harvey Dent’s vagrant facial parts are especially engaging around the jaws, and of course the Joker’s double rictus dominates his face. Gradually I found Maggie Gyllenhaal’s spoonbill lips starting to look peculiar.

The expository scenes were played with a somber knowingness I found stifling. Quoting lame dialogue is one of the handiest weapons in a critic’s arsenal and I usually don’t resort to it; many very good movies are weak on this front. Still, I can’t resist feeling that some weighty lines were doing duty for extended dramatic development, trying to convince me that enormous issues were churning underneath all the heists, fights, and chases. Know your limits, Master Wayne. Or: Some men just want to watch the world burn. Or: In their last moments people show you who they really are. Or: The night is darkest before the dawn.

I want to ask: Why so serious?

Odds are you think better of Iron Man and The Dark Knight than I do. That debate will go on for years. My purpose here is to explore a historical question: Why comic-book superhero movies now?

Z as in Zeitgeist

More superhero movies after 2002, you say? Obviously 9/11 so traumatized us that we feel a yearning for superheroes to protect us. Our old friend the zeitgeist furnishes an explanation. Every popular movie can be read as taking the pulse of the public mood or the national unconscious.

I’ve argued against zeitgeist readings in Poetics of Cinema, so I’ll just mention some problems with them:

*A zeitgeist is hard to pin down. There’s no reason to think that the millions of people who go to the movies share the same values, attitudes, moods, or opinions. In fact, all the measures we have of these things show that people differ greatly along all these dimensions. I suspect that the main reason we think there’s a zeitgeist is that we can find it in popular culture. But we would need to find it independently, in our everyday lives, to show that popular culture reflects it.

*So many different movies are popular at any moment that we’d have to posit a pretty fragmented national psyche. Right now, it seems, we affirm heroic achievement (Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, Kung Fu Panda, Prince Caspian) except when we don’t (Get Smart, The Dark Knight). So maybe the zeitgeist is somehow split? That leads to vacuity, since that answer can accommodate an indefinitely large number of movies. (We’d have to add fractions of our psyche that are solicited by Sex and the City and Horton Hears a Who!)

*The movie audience isn’t a good cross-section of the general public. The demographic profile tilts very young and moderately affluent. Movies are largely a middle-class teenage and twentysomething form. When a producer says her movie is trying to catch the zeitgeist, she’s not tracking retired guys in Arizona wearing white belts; she’s thinking mostly of the tastes of kids in baseball caps and draggy jeans.

* Just because a movie is popular doesn’t mean that people have found the same meanings in it that critics do. Interpretation is a matter of constructing meaning out of what a movie puts before us, not finding the buried treasure, and there’s no guarantee that the critic’s construal conforms to any audience member’s.

*Critics tend to think that if a movie is popular, it reflects the populace. But a ticket is not a vote for the movie’s values. I may like or dislike it, and I may do either for reasons that have nothing to do with its projection of my hidden anxieties.

*Many Hollywood films are popular abroad, in nations presumably possessing a different zeitgeist or national unconscious. How can that work? Or do audiences on different continents share the same zeitgeist?

Wait, somebody will reply, The Dark Knight is a special case! Nolan and his collaborators have strewn the film with references to post-9/11 policies about torture and surveillance. What, though, is the film saying about those policies? The blogosphere is already ablaze with discussions of whether the film supports or criticizes Bush’s White House. And the Editorial Board of the good, gray Times has noticed:

It does not take a lot of imagination to see the new Batman movie that is setting box office records, The Dark Knight, as something of a commentary on the war on terror.

You said it! Takes no imagination at all. But what is the commentary? The Board decides that the water is murky, that some elements of the movie line up on one side, some on the other. The result: “Societies get the heroes they deserve,” which is virtually a line from the movie.

I remember walking out of Patton (1970) with a hippie friend who loved it. He claimed that it showed how vicious the military was, by portraying a hero as an egotistical nutcase. That wasn’t the reading offered by a veteran I once talked to, who considered the film a tribute to a great warrior.

It was then I began to suspect that Hollywood movies are usually strategically ambiguous about politics. You can read them in a lot of different ways, and that ambivalence is more or less deliberate.

A Hollywood film tends to pose sharp moral polarities and then fuzz or fudge or rush past settling them. For instance, take The Bourne Ultimatum: Yes, the espionage system is corrupt, but there is one honorable agent who will leak the information, and the press will expose it all, and the malefactors will be jailed. This tactic hasn’t had a great track record in real life.

The constitutive ambiguity of Hollywood movies helpfully disarms criticisms from interest groups (“Look at the positive points we put in”). It also gives the film an air of moral seriousness (“See, things aren’t simple; there are gray areas”). That’s the bait the Times writers took.

I’m not saying that films can’t carry an intentional message. Bryan Singer and Ian McKellen claim the X-Men series criticizes prejudice against gays and minorities. Nor am I saying that an ambivalent film comes from its makers delicately implanting counterbalancing clues. Sometimes they probably do. More often, I think, filmmakers pluck out bits of cultural flotsam opportunistically, stirring it all together and offering it up to see if we like the taste. It’s in filmmakers’ interests to push a lot of our buttons without worrying whether what comes out is a coherent intellectual position. Patton grabbed people and got them talking, and that was enough to create a cultural event. Ditto The Dark Knight.

Back to basics

If the zeitgeist doesn’t explain the flourishing of the superhero movie in the last few years, what does? I offer some suggestions. They’re based on my hunch that the genre has brought together several trends in contemporary Hollywood film. These trends, which can commingle, were around before 2000, but they seem to be developing in a way that has created a niche for the superhero film.

The changing hierarchy of genres. Not all genres are created equal, and they rise or fall in status. As the Western and the musical fell in the 1970s, the urban crime film, horror, and science-fiction rose. For a long time, it would be unthinkable for an A-list director to do a horror or science-fiction movie, but that changed after Polanski, Kubrick, Ridley Scott, et al. gave those genres a fresh luster just by their participation. More recently, I argue in The Way Hollywood Tells It, the fantasy film arrived as a respectable genre, as measured by box-office receipts, critical respect, and awards. It seems that the sword-and-sorcery movie reached its full rehabilitation when The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King scored its eleven Academy Awards.

The comic-book movie has had a longer slog from the B- and sub-B-regions. Superman, Flash Gordon, and Dick Tracy were all fodder for serials and low-budget fare. Prince Valiant (1954) was the only comics-derived movie of any standing in the 1950s, as I recall, and you can argue that it fitted into a cycle of widescreen costume pictures. (Though it looks like a pretty camp undertaking today.) Much later came revivals of the two most popular superheroes, Superman (1978) and Batman (1989).

The success of the Batman film, which was carefully orchestrated by Warners and its DC comics subsidiary, can be seen as preparing the grounds for today’s superhero franchises. The idea was to avoid simply reiterating a series, as the Superman movie did, or mocking it, as the Batman TV show did. The purpose was to “reimagine” the series, to “reboot” it as we now say, the way Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns re-launched the Batman comic. Rebooting modernizes the mythos by reinterpreting it in a thematically serious and graphically daring way.

During the 1990s, less famous superheroes filled in as the Batman franchise tailed off. Examples were The Rocketeer (1991), Timecop (1994), The Crow (1994) and The Crow: City of Angels (1996), Judge Dredd (1995), Men in Black (1997), Spawn (1997), Blade (1998), and Mystery Men (1999). Most of these managed to fuse their appeals with those of another parvenu genre, the kinetic action-adventure movie.

Significantly, these were typically medium-budget films from semi-independent companies. Although some failed, a few were huge and many earned well, especially once home video was reckoned in. Moreover, the growing number of titles, sometimes featuring name actors, fueled a sense that this genre was becoming important. As often happens, marginal companies developed the market more nimbly than the big ones, who tend to move in once the market has matured.

I’d also suggest that The Matrix (1999) helped legitimize the cycle. (Neo isn’t a superhero? In the final scene he can fly.) The pseudophilosophical aura this movie radiated, as well as its easy familiarity with comics, videogames, and the Web, made it irrevocably cool. Now ambitious young directors like Nolan, Singer, and Brett Ratner could sign such projects with no sense they were going downmarket.

The importance of special effects. Arguably there were no fundamental breakthroughs in special-effects technology from the 1940s to the 1960s. But with motion-control cinematography, showcased in the first Star Wars installment (1977) filmmakers could create a new level of realism in the use of miniatures. Later developments in matte work, blue- and green-screen techniques, and digital imagery were suited to, and driven by, the other genres that were on the rise—horror, science-fiction, and fantasy—but comic-book movies benefited as well. The tagline for Superman was “You’ll believe a man can fly.”

Special effects thereby became one of a film’s attractions. Instead of hiding the technique, films flaunted it as a mark of big budgets and technological sophistication. The fantastic powers of superheroes cried out for CGI, and it may be that convincing movies in the genre weren’t really ready until the software matured.

The rise of franchises. Studios have always sought predictability, and the classic studio system relied on stars and genres to encourage the audience to return for more of what it liked. But as film attendance waned, producers looked for other models. One that was successful was the branded series, epitomized in the James Bond films. With the rise of the summer blockbuster, producers searched for properties that could be exploited in a string of movies. A memorable character could tie the installments together, and so filmmakers turned to pop literature (e.g., the Harry Potter books) and comic books. Today, Marvel Enterprises is less concerned with publishing comics than with creating film vehicles for its 5000 characters. Indeed, to get bank financing it put up ten of its characters as collateral!

Yet a single character might not sustain a robust franchise. Henry Jenkins has written about how popular culture is gravitating to multi-character “worlds” that allow different media texts to be carved out of them. Now that periodical sales of comics have flagged, the tail is wagging the dog. The 5000 characters in the Marvel Universe furnish endless franchise opportunities. If you stayed for the credit cookie at the end of Iron Man, you saw the setup for a sequel that will pair the hero with at least one more Marvel protagonist.

Merchandising and corporate synergy. It’s too obvious to dwell on, but superhero movies fit neatly into the demand that franchises should spawn books, TV shows, soundtracks, toys, apparel, and so on. Time Warner’s acquisition of DC Comics was crucial to the cross-platform marketing of the first Batman. Moreover, most comics readers are relatively affluent (a big change from my boyhood), so they have the income to buy action figures and other pricy collectibles, like a Batbed.

The shift from an auteur cinema to a genre cinema. The classic studio system maintained a fruitful, sometimes tense, balance between directorial expression and genre demands. Somewhere in recent decades that balance has split into polarities. We now have big-budget genre films that made by directors of no discernible individuality, and small “personal” films that showcase the director’s sensibility. There have always been impersonal craftsmen in Hollywood, but the most distinctive directors could often bring their own sensibilities to projects big or small.

David Lynch could make Dune (1984) part of his own oeuvre, but since then we have many big-budget genre pictures that bear no signs of directorial individuality. In particular, science-fiction, fantasy, and superhero movies demand so much high-tech input, so much preparation, so many logistical tasks in shooting, and such intensive postproduction, that economy of effort favors a standardized look and feel. Hence perhaps the recourse to well-established techniques of shooting and cutting; intensified continuity provides a line of least resistance. A comic-book movie can succeed if it doesn’t stray from the fanbase’s expectations and swiftly initiates the newbies. Not much directorial finesse is needed, as 300 (2007) shows.

The development of the megapicture may have led the more talented directors to the “one for them, one for me” motto. Think of the difference between Burton’s Planet of the Apes or even Sweeney Todd and, say, Ed Wood or Big Fish. Or think of the moments of elegance in Memento and The Prestige, as opposed to the blunt handling of Batman Begins and The Dark Knight.

Shock and awe in presentation. The rise of the multiplex meant not only an upgrade in comfort (my back appreciates the tilting seats) but also a demand for big pictures and big sound. Smaller, more intimate movies look woeful on your megascreen, and what’s the point of Dolby surround channels if you’re watching a Woody Allen picture? Like science-fiction and fantasy, the adventures of a superhero in yawning landscapes fill the demand for immersion in a punchy, visceral entertainment. Scaling the film for Imax, as Superman Returns and The Dark Knight have, is the next step in this escalation.

Shock and awe in presentation. The rise of the multiplex meant not only an upgrade in comfort (my back appreciates the tilting seats) but also a demand for big pictures and big sound. Smaller, more intimate movies look woeful on your megascreen, and what’s the point of Dolby surround channels if you’re watching a Woody Allen picture? Like science-fiction and fantasy, the adventures of a superhero in yawning landscapes fill the demand for immersion in a punchy, visceral entertainment. Scaling the film for Imax, as Superman Returns and The Dark Knight have, is the next step in this escalation.

Too much is never enough. Since the 1980s, mass-audience pictures have gravitated toward ever more exaggerated presentation of momentary effects. In a comedy, if a car is about to crash, everyone inside must stare at the camera and shriek in concert. Extreme wide-angle shooting makes faces funny in themselves (or so Barry Sonnenfeld thinks). Action movies shift from slo-mo to fast-mo to reverse-mo, all stitched together by ramping, because somebody thinks these devices make for eye candy. Steep high and low angles, familiar in 1940s noir films, were picked up in comics, which in turn re-influenced movies.

Movies now love to make everything airborne, even the penny in Ghost. Things fly out at us, and thanks to surround channels we can hear them after they pass. It’s not enough simply to fire an arrow or bullet; the camera has to ride the projectile to its destination—or, in Wanted, from its target back to its source. In 21 of earlier this year, blackjack is given a monumentality more appropriate to buildings slated for demolition: giant playing cards whoosh like Stealth fighters or topple like brick walls.

I’m not against such one-off bursts of imagery. There’s an undoubted wow factor in seeing spent bullet casings shower into our face in The Matrix.

I just ask: What do such images remind us of? My answer: Comic book panels, those graphically dynamic compositions that keep us turning the pages. In fact, we call such effects “cartoonish.” Here’s an example from Watchmen, where the slow-motion effect of the Smiley pin floating down toward us is sustained by a series of lines of dialogue from the funeral service.

With comic-book imagery showing up in non-comic-book movies, one source may be greater reliance on storyboards and animatics. Spfx demand intensive planning, so detailed storyboarding was a necessity. Once you’re planning shot by shot, why not create very fancy compositions in previsualization? Spielberg seems to me the live-action master of “storyboard cinema.” And of course storyboards look like comic-book pages.

The hambone factor. In the studio era, star acting ruled. A star carried her or his persona (literally, mask) from project to project. Parker Tyler once compared Hollywood star acting to a charade; we always recognized the person underneath the mime.

This is not to say that the stars were mannequins or dead meat. Rather, like a sculptor who reshapes a piece of wood, a star remolded the persona to the project. Cary Grant was always Cary Grant, with that implausible accent, but the Cary Grant of Only Angels Have Wings is not that of His Girl Friday or Suspicion or Notorious or Arsenic and Old Lace. Or compare Barbara Stanwyck in The Lady Eve, Double Indemnity, and Meet John Doe. Young Mr. Lincoln is not the same character as Mr. Roberts, but both are recognizably Henry Fonda.

Dress them up as you like, but their bearing and especially their voices would always betray them. As Mr. Kralik in The Shop around the Corner, James Stewart talks like Mr. Smith on his way to Washington. In The Little Foxes, Herbert Marshall and Bette Davis sound about as southern as I do.

Star acting persisted into the 1960s, with Fonda, Stewart, Wayne, Crawford, and other granitic survivors of the studio era finishing out their careers. Star acting continues in what scholar Steve Seidman has called “comedian comedy,” from Jerry Lewis to Adam Sandler and Jack Black. Their characters are usually the same guy, again. Arguably some women, like Sandra Bullock and Ashlee Judd, also continued the tradition.

On the whole, though, the most highly regarded acting has moved closer to impersonation. Today your serious actors shape-shift for every project—acquiring accents, burying their faces in makeup, gaining or losing weight. We might be inclined to blame the Method, but classical actors went through the same discipline. Olivier, with his false noses and endless vocal range, might be the impersonators’ patron saint. His followers include Streep, Our Lady of Accents, and the self-flagellating young De Niro. Ironically, although today’s performance-as-impersonation aims at greater naturalness, it projects a flamboyance that advertises its mechanics. It can even look hammy. Thus, as so often, does realism breed artifice.

On the whole, though, the most highly regarded acting has moved closer to impersonation. Today your serious actors shape-shift for every project—acquiring accents, burying their faces in makeup, gaining or losing weight. We might be inclined to blame the Method, but classical actors went through the same discipline. Olivier, with his false noses and endless vocal range, might be the impersonators’ patron saint. His followers include Streep, Our Lady of Accents, and the self-flagellating young De Niro. Ironically, although today’s performance-as-impersonation aims at greater naturalness, it projects a flamboyance that advertises its mechanics. It can even look hammy. Thus, as so often, does realism breed artifice.

Horror and comic-book movies offer ripe opportunities for this sort of masquerade. In a straight drama, confined by realism, you usually can’t go over the top, but given the role of Hannibal Lector, there is no top. The awesome villain is a playground for the virtuoso, or the virtuoso in training. You can overplay, underplay, or over-underplay. You can also shift registers with no warning, as when hambone supreme Orson Welles would switch from a whisper to a bellow. More often now we get the flip from menace to gargoylish humor. Jack Nicholson’s “Heeere’s Johnny” in The Shining is iconic in this respect. In classic Hollywood, humor was used to strengthen sentiment, but now it’s used to dilute violence.

Such is the range we find in The Dark Knight. True, some players turn in fairly low-key work. Morgan Freeman plays Morgan Freeman, Michael Caine does his usual punctilious job, and Gary Oldman seems to have stumbled in from an ordinary crime film. Maggie Gylenhaal and Aaron Eckhart provide a degree of normality by only slightly overplaying; even after Harvey Dent’s fiery makeover Eckhart treats the role as no occasion for theatrics.

All else is Guignol. The Joker’s darting eyes, waggling brows, chortles, and restless licking of his lips send every bit of dialogue Special Delivery. Ledger’s performance has been much praised, but what would count as a bad line reading here? The part seems designed for scenery-chewing. By contrast, poor Bale has little to work with. As Bruce Wayne, he must be stiff as a plank, kissing Rachel while keeping one hand suavely tucked in his pocket, GQ style. In his Bat-cowl, he’s missing as much acreage of his face as Dent is, so all Bale has is the voice, over-underplayed as a hoarse bark.

In sum, our principals are sweating through their scenes. You get no strokes for making it look easy, but if you work really hard you might get an Oscar.

A taste for the grotesque. Horror films have always played on bodily distortions and decay, but The Exorcist (1973) raised the bar for what sorts of enticing deformities could be shown to mainstream audiences. Thanks to new special effects, movies like Total Recall (1990) were giving us cartoonish exaggerations of heads and appendages.

A taste for the grotesque. Horror films have always played on bodily distortions and decay, but The Exorcist (1973) raised the bar for what sorts of enticing deformities could be shown to mainstream audiences. Thanks to new special effects, movies like Total Recall (1990) were giving us cartoonish exaggerations of heads and appendages.

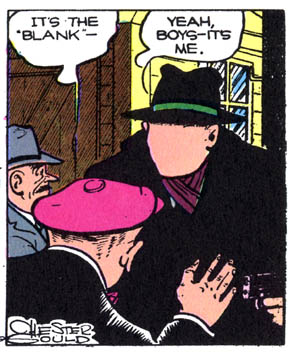

But of course the caricaturists got here first, from Hogarth and Daumier onward. Most memorably, Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy strip offered a parade of mutilated villains like Flattop, the Brow, the Mole, and the Blank, a gentleman who was literally defaced. The Batman comics followed Gould in giving the protagonist an array of adversaries who would even raise an eyebrow in a Manhattan subway car.

Eisenstein once argued that horrific grotesquerie was unstable and hard to sustain. He thought that it teetered between the comic-grotesque and the pathetic-grotesque. That’s the difference, I suppose, between Beetlejuice and Edward Scissorhands, or between the Joker and Harvey Dent. In any case, in all its guises the grotesque is available to our comic-book pictures, and it plays nicely into the oversize acting style that’s coming into favor.

You’re thinking that I’ve gone on way too long, and you’re right. Yet I can’t withhold two more quickies:

The global recognition of anime and Hong Kong swordplay films. During the climactic battle between Iron Man 2.0 and 3.0, so reminiscent of Transformers, I thought: “The mecha look has won.”

Learning to love the dark. That is, filmmakers’ current belief that “dark” themes, carried by monochrome cinematography, somehow carry more prestige than light ones in a wide palette. This parallels comics’ urge for legitimacy by treating serious subjects in somber hues, especially in graphic novels.

Time to stop! This is, after all, just a list of causes and conditions that occurred to me after my day in the multiplex. I’m sure we can find others. Still, factors like these seem to me more precise and proximate causes for the surge in comic-book films than a vague sense that we need these heroes now. These heroes have been around for fifty years, so in some sense they’ve always been needed, and somebody may still need them. The major media companies, for sure. Gazillions of fans, apparently. Me, not so much. But after Hellboy II: The Golden Army I live in hope.

Thanks to Hank Luttrell for information about the history of the comics market.

The superhero rankings I mentioned are: Spider-Man 3 (no. 12), Spider-Man (no. 17), Spider-Man 2 (no. 23), The Dark Knight (currently at no. 29, but that will change), Men in Black (no. 42), Iron Man (no. 45), X-Men: The Last Stand (no. 75), 300 (no. 80), Men in Black II (no. 85), Batman (no. 95), and X2: X-Men United (no. 98). The usual caveat applies: This list is based on unadjusted grosses and so favors recent titles, because of inflation and the increased ticket prices. If you adjust for these factors, the list of 100 all-time top grossers includes seven comics titles, with the highest-ranking one being Spider-Man, at no. 33.

For a thoughtful essay written just as the trend was starting, see Ken Tucker’s 2000 Entertainment Weekly piece, “Caped Fears.” It’s incompletely available here.

Comics aficionados may object that I am obviously against comics as a whole. True, I have little interest in superhero comic books. As a boy I read the DC titles, but I preferred Mad, Archie, Uncle Scrooge, and Little Lulu. In high school and college I missed the whole Marvel revolution and never caught up. Like everybody else in the 1980s I read The Dark Knight Returns, but I preferred Watchmen (and I look forward to the movie). I like the Hellboy movies too. But I’m not gripped by many of the newest trends in comics. Sin City strikes me as a fastidious piece of draftsmanship exercised on formulaic material, as if Mickey Spillane were rewritten by Nicholson Baker. Since the 80s my tastes have run to Ware, Clowes, a few manga, and especially Eurocomics derived from the clear-line tradition (Chaland, Floc’h, Swarte, etc.). I believe that McCay and Herriman are major twentieth-century artists, with Chester Gould and Cliff Sterrett worth considering for the honor too.

You can argue that Oliver Stone’s films create ambivalence inadvertently. JFK seems to have a clear-cut message, but the plotting is diverted by so many conspiracy scenarios that the viewer might get confused about what exactly Stone is claiming really happened.

On the ways that worldmaking replaces character-centered media storytelling, the crucial discussion is in Henry Jenkins, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide (New York University Press, 2007), 113-122.

On franchise-building, see the detailed account in detail in Eileen R. Meehan, “‘Holy Commodity Fetish, Batman!’: The Political Economy of a Commercial Intertext,” in The Many Lives of the Batman, ed. Roberta E. Pearson and William Uricchio (Routledge, 1991), 47-65. Other essays in this collection offer information on the strategies of franchise-building.

Just as Star Wars helped legitimate itself by including Alec Guinness in its cast (surely he wouldn’t be in a potboiler), several superhero movies have a proclivity for including a touch of British class: McKellan and Stewart in X-Men, Caine in the Batman series. These old reliables like to keep busy and earn a spot of cash.

PS: 21 August 2008: This post has gotten some intriguing responses, both on the Internets and in correspondence with me, so I’m adding a few here.

Jim Emerson elaborated on the zeitgeist motif in an entry at Scanners. At Crooked Timber, John Holbo examines how much the film’s dark cast owes to the 1990s reincarnation of Batman. Peter Coogan writes to tell me that he makes a narrower version of the zeitgeist argument in relation to superheroes in Chapter 10 of his book, Superhero: The Secret Origin of a Genre, to be reprinted next year. Even the more moderate form he proposes doesn’t convince me, I’m afraid, but the book ought to be of value to readers interested in the genre.

From Stew Fyfe comes a letter offering some corrections and qualifications.

*Stew points out that chain stores like Borders do sell some periodical comics titles, though not always regularly.

*Comics publishing, while not at the circulation levels seen in the golden era, is undergoing something of a resurgence now, possibly because of the success of the franchise movies. Watchmen sales alone will be a big bump in anticipation of the movie.

*As for my claim that film is driving the publishing side, Stew suggests that the relations between the media are more complicated. The idea that the tail wags the dog might apply to DC, but Marvel has made efforts to diversify the relations between the books and the films.

They’ve done things like replacing the Hulk with a red, articulate version of the character just before the movie came out (which is odd because if there’s one thing that the general public knows about the character is that he’s green and he grunts). They’ve also handed the Hulk’s main title over to a minor character, Hercules. They’ve spent a year turning Iron Man, in the main continuity, into something of a techno-fascist (if lately a repentant one) who locks up other superheroes.

Stew speculates that Marvel is trying to multiply its audiences. It relies on its main “continuity books” to serve the fanbase who patronizes the shops, and the films sustain each title’s proprietary look and feel. In addition, some of the books offer fresh material for anyone who might want to buy the comic after seeing the film; this tactic includes reprinted material and rebooted continuity lines in the Ultimate series. Marvel has also brought in film and TV creators as writers (Joss Whedon, Kevin Smith), while occasionally comics artists work in TV shows like Heroes, Lost, and Battlestar Galactica. So the connections are more complex than I was indicating.

Thanks to all these readers for their comments.

Rio Jim, in discrete fragments

The first moving-pictures, as I remember them thirty years ago, presented more or less continuous scenes. They were played like ordinary plays, and so one could follow them lazily and at ease. But the modern movie is no such organic whole; it is simply a maddening chaos of discrete fragments. The average scene, if the two shows I attempted were typical, cannot run for more than six or seven seconds. Many are far shorter, and very few are appreciably longer. The result is confusion horribly confounded. How can one work up any rational interest in a fable that changes its locale and its characters ten times a minute?

H. L. Mencken, 1927

DB here:

Between about 1913 and 1920, the way movies looked changed, and we are still living with the results. What were the changes? What brought them about?

I’m just back from Brussels, after a two-week visit to the archive. During earlier trips, I’ve concentrated on examining films from the 1910s that exemplify the tableau tradition. That’s what we might call the stylistic approach that tells the story and achieves its other effects predominantly through staging—by arranging the actors within the frame, forming patterns that reflect what is important at a given moment.

The tableau tradition dominated European cinema of the early and mid-1910s, and it was also on display in the U. S. It is sometimes considered “theatrical” and “uncinematic,” but that’s a shortsighted view. The tableau tradition is one of the great artistic triumphs of film history. For backup on this, consult Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs’ Theatre to Cinema and my On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light. And you can go here and here on this site.

As the 1910s moved on, the staging-driven approach gave way to one dominated by editing. Roughly speaking, this strategy surfaced at two levels. Directors began to use crosscutting, aka parallel editing, more strenuously. By alternating shots, you could show events taking place at two or more locations. This technique was not used only for last-minute rescues; it was a way of keeping track of all the characters in nearly every sequence, whether they were going to converge or not.

Second, within a single strand of action, 1910s directors exploited analytical editing, breaking down a scene’s space into a host of details. Griffith often gets the credit for this tactic (and he happily claimed to have invented it), but it’s probably most fairly understood as a collective innovation.

Directors in the tableau tradition didn’t entirely avoid crosscutting or analytical editing, but there was a measurable shift of gravity in the second half of the 1910s. In the U.S., many filmmakers pushed editing techniques very hard. You can sense their exhilaration in discovering how editing lets them control pacing, make story points concisely, build suspense, and force the viewer to keep up.

During the 1910s, American movies became breathless. The hurtling pace of Speed Racer or The Dark Knight has its origins here; seen today, The Battle at Elderbush Gulch (1913) and Wild and Woolly (1917) still look mighty rapid-fire. And then as now some observers, like Mencken, complained that it was all too fast and furious.

Over the last thirty years, many scholars have studied this change, but for a glimpse of some supporting data, you can visit the remarkable website Cinemetrics. Yuri Tsivian, Barry Salt, and a corps of volunteer scholars have been measuring Average Shot Lengths in films from all eras. The data from the 1910s are pretty unequivocal. In the US around 1916-1918, movies became editing-dominated, shifting from an ASL of over 10 seconds, sometimes as much as 30 seconds, to 5-6 seconds or less. A 4-6 second average per shot persists in Hollywood through the 1920s, so Mencken’s guess about the “scenes” (as shots were then known) changing ten times a minute was more or less right.

Back in the 1980s, Salt and others, including Kristin and me, picked 1917 as a plausible point of reference for the consolidation of the continuity style. That was the point at which virtually every US film we watched contained at least one example of specific continuity techniques. (Most contained many more instances, of course.) We talk about that magical year in this entry, which you might want to read as an introduction to what follows today.

In just a few years, continuity editing became a coherent, supple means of expression, and it has defined Hollywood film style up to the present. What brought this about? Kristin and Janet Staiger offered an explanation in our 1985 book, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960. They traced out several factors that encouraged and sustained this style. Especially important were the development of longer films, a conception of filmic quality, and the emergence of a specific division of labor.

Lately I’ve been revisiting these early years, chiefly to watch how directors pick up and refine the stylistic schemas that were coming into broader use. I want to know more about the little touches that directors had to control in creating this style. I’ve also been interested in to what extent these techniques were picked up by directors in Europe and Asia. The evidence is pretty clear that continuity cinema became a lingua franca of film style.

So if last year I pondered the minute compositional adjustments of Evgenii Bauer, this year it was all cutting. I focused on three filmmakers, but I’ll save discussion of two of them for a rainy day, or a book. In all, it was a thrill, as ever, to watch a stylistic system coalesce across a batch of films that are seldom mentioned in the history books.

The trail to continuity

The extraordinary films starring William S. Hart typify early American continuity techniques. After a distinguished career on the stage, Hart began as a film actor in 1914, when he was nearly fifty. He was intent on bringing realism to the newly burgeoning Western genre. His films were at first made under the auspices of Thomas Ince, a pioneer of rationalized production techniques, and with his Ince pictures Hart found worldwide success. He followed a rousing feature debut (On the Night Stage, 1915) with many shorter films. In 1917—mark the year—Hart broke with Ince and set up his own firm for The Narrow Trail. He continued to make films into the early 1920s, with Tumbleweeds (1925) marking his farewell to cinema.

Hart often directed his own pictures, though he also had the services of strong directors like Reginald Barker. The films have an assured brio, thanks to careful cutting and some felicitous touches.

They are fast-moving: In the five 1915 Hart films I watched, the ASL ranged from 8 to 11 seconds, but in 1916, the average jumped to 5-6 seconds per shot. The Narrow Trail seems to have an ASL of 3.7 seconds, but I can hardly believe it and I must verify it with another viewing. The 1918 and 1920 films I viewed average between 4.9 and 5.4 seconds per shot.

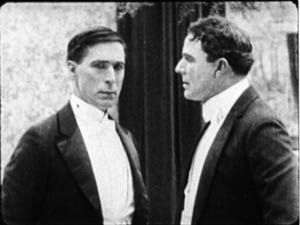

Just as important as the speed of cutting, naturally, is what Hart does with his cuts. In one scene from Between Men (1916), you can see the tableau aesthetic undermined by analytical editing. Gregg is a shifty stock trader, a species we still nurture. He’s trying to destroy Hampton’s fortune because he thinks that when the old man is destitute he’ll force his daughter to marry Gregg. Hampton has asked Bob White (Hart) to help get the goods on the suitor.

In one scene, the master shot approximates a tableau setup: Bob and Gregg stand in the middle ground, with a room visible behind them.

As the men swap increasingly tense challenges, Margaret Hampton enters the adjacent room and stands behind them as they talk. A director in the tableau tradition would have sustained the master shot and shown Margaret approaching in the background and drawing closer, reacting to what the men say. She could easily have been stationed hovering at the curtain on the right.

Instead, director C. Gardiner Sullivan has her arrive from another doorway in the adjacent room, one not visible in the master shot of the two men. He then cuts back and forth between the men and Margaret, and he positions her at the left curtain–so that the men block her from our view! The blockage motivates cutting to Margaret for her reactions to what Bob and Gregg say.

Only when she wants to challenge Bob’s suggestion that he might marry her does Margaret come into the same frame as the men, who part to make room for her.

It turns out that this sequence is but a rehearsal for a lengthier passage in which Hampton will come in from the adjacent room (via the door we do see in the background). As with Margaret’s entrance, his arrival will be blocked by Gregg’s body, and Sullivan will cut among the trio in the foreground and Hampton’s approach behind them. That passage, which could also have been handled in a single framing in the tableau style, consists of four distinct setups and eighteen shots!

So even depth-based scenes can be recast as rapid découpage. The passage is probably overcut, but you can sense the filmmakers’ exhilaration in their power to chop up the world into separate, slightly jolting bits, forcing the audience to keep abreast of each item of information.

Managing details

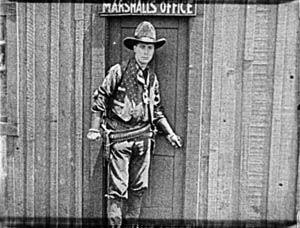

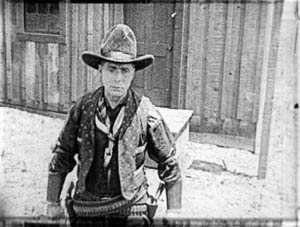

The variety of setups is worth noticing in another film, for here we can see the filmmakers taking pains to show each bit of action most clearly and emphatically. In The Return of Draw Egan (1916), when Egan sees the mayor’s daughter Myrtle he decides to stay on as marshal of Yellow Dog. The first shots show them looking at each other.

The next pair of shots shows the two looking at each other in close-up.

This gradual enlargement of the figures in a reverse-shot sequence would of course become a staple of analytical editing—perhaps it already was in 1916. Cut back to another framing of Egan, as the mayor signals Myrtle to join them. The slightly off-center composition reiterates her position off left.

Cut back to Myrtle, exiting her close-up. The next shot shows her joining the men, to be introduced to Egan.

But this is a different camera position than the one showing the men just previously. The daughter’s entrance has motivated a slightly changed composition. In the 1910s, cutting began to dictate staging, so that each composition had to fit smoothly into the flow of shots.

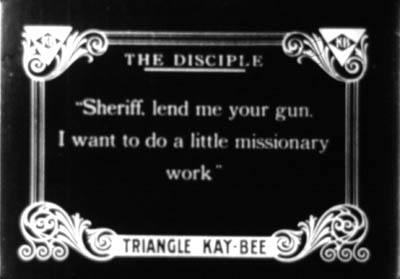

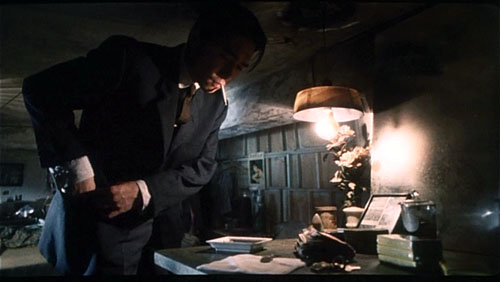

This sequence from Draw Egan doesn’t utilize axial cuts, those cuts that keep to the same angle and move straight in or out. Here the actors are angled to suggest that we are to some degree in between them. Indeed, sometimes the camera will put us directly between the characters. Here is a climactic confrontation from The Disciple (1915). A doctor has cuckolded Hart, but Hart brings him to save his daughter. As the doctor enters, the wife’s shameful look is met by Doc’s anxious expression, with a furious Hart pressing a pistol to his back.

This freedom of camera placement extends to point-of-view cutting. Again, this is an old technique, but like other old techniques, it was revived and refined as part of the synthesis that became the continuity style. So Keno Bates, Liar (1915; a splendid title) can make use of a cameo picture that captivates Bates after a shootout with the man who robbed him.

Later, the dance-hall girl catches sight of her rival when Bates muses on the cameo.

The pov framings don’t change much, but the angle chosen easily approximates both Bates’ view and her view over his shoulder. Moreover, the shot of Bates’ hands isn’t the sort of vacuous insert we often see at the period, with a letter or an object isolated against a blank ground. Here, the backgrounds change, so that the first shot is situated naturally in the wild, while the second is consistent with the barroom locale.

Putting the pieces together

From very early in the history of Westerns, the main street shootout seems to have been a solid convention. Already in The Return of Draw Egan, it’s treated with a vitality and ingenuity that suggests creative reworking of a staple. The climactic shootout also shows just how flexible the new technique could be.

Egan has told his enemy, Arizona Joe, that he’ll meet him when the setting sun’s rays hit the saloon window. So the film crosscuts Egan in his marshal’s office with a nervous Joe, seen in close-up, eyeing the window.

When Joe gets up the nerve to leave, he hides behind a barrel and waits to ambush Egan. When Egan leaves his office, a reverse tracking shot follows him striding toward us.

Then we get an orienting long shot with Joe in the foreground and Egan approaching.

Edging sideways, Egan spots a reflection of Joe’s head in a window. These shots surmount today’s blog entry. You can see Egan’s reflection in the upper left pane.

Now aware of Joe’s tactic, Egan steps diagonally forward, coming ominously right up to the camera.

He fires and dispatches Joe. The townsfolk, who have been huddled in a house watching, declare they want Egan to stay on as marshal, despite his outlaw past. Myrtle chimes in, and we get a happy ending. Chaotic fragments? Mencken couldn’t have been more wrong. Or maybe he was just being grumpy.

The trail to Hollywood

There’s plenty more in these films—beautiful, sometimes minuscule matches on action; subtle timing of frame entrances and exits; and even proto-over-the-shoulder reverse shots. And we don’t have to claim that Hart’s films are the only innovative ones. They take their place within a broader, collective achievement that we still haven’t fully grasped.

Editing permitted everyone to act at small scale; the bargirl who sees Bates’ cameo need only lower one fist, tighten the other, and narrow her eyes to express her jealousy. The new style nurtured laconic stars like Hart. His films are full of pathetic situations that demand he display stoicism but also sensitivity. The long shots could emphasize his gestures and stances, while close-ups could display his worn, haunted face and pale eyes. He acts with those eyes, glancing aside to recall a traumatic event or looking downward as he hesitates to break bad news. Often the plot demands that he conceal his feelings or hide the truth behind an event, and the changing shots could penetrate the surface drama and highlight his slightest reactions. Hart could underplay his role because the editing shows us everything he might have said.

Known in France as Rio Jim, Hart was very influential on the Europeans. His pictures, along with De Mille’s The Cheat (1915) and the films of Chaplin and Fairbanks and many others, offered tutorials in the new style. Arguably, the cumulative force of these mainstream releases was greater than the influence of Griffith’s more prestigious output of the moment. There was only one Intolerance (1916), the film by which Griffith was most widely known abroad, but week by week the Westerns and comedies and dramas pouring out of Hollywood flaunted a new, almost frighteningly energetic approach to cinema.

Timing favored the Americans. The style emerged at around the start of World War I, when hostilities gave U. S. films a chance to displace the big French and Danish companies in many markets. Kristin explains how this happened in Exporting Entertainment, and she talks about the exceptional case of Germany in Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood.

Some European directors picked up the new style immediately, others took a bit longer, and a few, like Feuillade, never fully adjusted to it. The principles of the older tableau style never utterly died out, as I try to show in Figures Traced in Light. But the future belonged to the editing-based aesthetic. Canonized, tweaked, updated, dismantled, undermined—however filmmakers reacted to classical continuity, it became the basis of international cinematic storytelling.

My epigraph comes from H. L. Mencken, “Appendix from Moronia: Note on Technic,” from Prejudices: Sixth Series (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1927), rep. in Phillip Lopate, ed., American Movie Critics: An Anthology From the Silents Until Now, expanded edition (New York: The Library of America, 2006), 35-36.

Silent film speeds can vary, so shot counts can yield different averages. I saw some of the Harts I mention in projection at last year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato, and they were projected at 18 or 19 frames per second, a common speed for the period. My ASLs are based on the running time. For the titles I saw in Brussels on a flatbed viewer, my basis was the length in meters. From that I’ve calculated running times and averages, assuming 18 frames per second. Projectionists of the time had freedom to screen at different speeds, so it’s possible that late 1910s Hart films were sometimes shown at 20 frames per second, which of course would make their cutting pace even faster.