Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

Times go by turns

Kristin here—

Last week during the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image conference here in Madison, I got to talking with Prof. Birger Langkjær of the University of Copenhagen. He asked me some questions about the concept of “turning points” in film narrative as I had used it in my book, Storytelling in the New Hollywood: Understanding Classical Narrative Technique. Specifically he wondered if turning points invariably involve changes of which the protagonist or protagonists are aware. The protagonist’s goals are usually what shape the plot, so can one have a turning point without him or her knowing about it?

I couldn’t really give a definitive answer on the spot, partly because it’s a complex subject and partly because I finished the book a decade ago (for publication in 1999). It seemed worth going back and trying to categorize the turning points in films I analyzed. Describing those turning points more specifically could be useful in itself, and it might help determine to what extent a protagonist’s knowledge of what causes those turning points typically forms a crucial component of them.

Characteristics of turning points

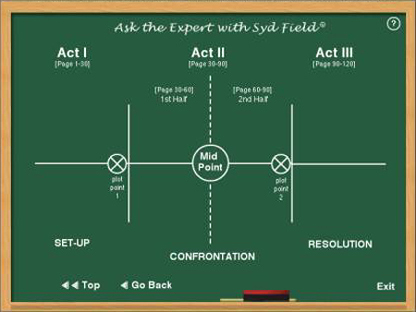

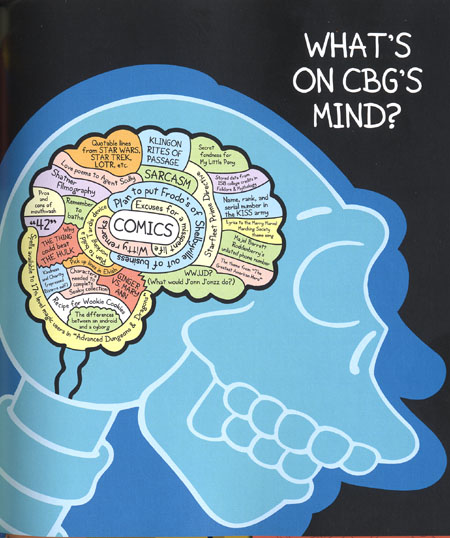

Most screenplay manuals treat turning points as the major events or changes that mark the end of an “act” of a movie. Syd Field, perhaps the most influential of all how-to manual authors, declared that all films, not just classical ones, have three acts. In a two-hour film, the first act will be about 30 minutes long, the second 60 minutes, and the third 30 minutes. The illustration at the top shows a graphic depiction of his model, which includes a midpoint, though Field doesn’t consider that midpoint to be a turning point.

I argued against this model in Storytelling, suggesting that upon analysis, most Hollywood films in fact have four large-scale parts of roughly equal length. The “three-act structure” has become so ingrained in thinking about film narratives that my claim is somewhat controversial. What has been overlooked is that I’m not claiming that all films have four acts. Rather, my claim is that in classical films large-scale parts tend to fall within the same average length range, roughly 25 to 35 minutes. If a film is two and a half hours rather than two hours, it will tend to have five parts, if three hours long, then six, and so on. And it’s not that I think films must have this structure. From observation, I think they usually do. Apparently filmmakers figured out early on, back in the mid-1910s when features were becoming standard, that the action should optimally run for at most about half an hour without some really major change occurring.

Field originally called these changes “plot points,” and he defined them as “an incident, or event, that hooks into the story and spins it around into another direction.” Perhaps because of that shift in direction, these moments have come more commonly to be called “turning points.” But what are they? Field’s definition is pretty vague.

In Storytelling I wrote, “I am assuming that the turning points almost invariably relate to the characters’ goals. A turning point may occur when a protagonist’s goal jells and he or she articulates it .… Or a turning point may come when one goal is achieved and another replaces it.” I also assumed that a major new premise often leads to a goal change (p. 29). “Almost invariably” because I don’t assume that there are hard and fast rules. As with large-scale parts, my claims about other classical narrative guidelines aren’t prescriptive in the way that screenplay manuals usually are.

To reiterate a few other things I said about turning points. They are not always the same as the moments of highest drama. Using Jaws as my example, I suggest that the moments of decision (not to hire Quint to kill the shark and later to hire him after all), rather than the big action scenes of the shark attacks, shape the causal chain (p. 33).

Not all turning points come exactly at the end of a large-scale part of the film (an “act” in most screenplay manuals). A turning point might come shortly before the end of a part, or the turning point may come at the beginning of the new part (pp. 29-30). The final turning point that leads into the climax comes when “all the premises regarding the goals and the lines of action have been introduced” (p. 29).

Most screenplay manuals consider goals to be static. To me, “Shifting or evolving goals are in fact the norm, at least in well-executed classical films” (p. 52). This doesn’t mean that the goal changes at every turning point. Instead, the end of a large-scale part may lead to a continuation of the goal(s) but with a distinct change of tactics (p. 28).

One big advantage of talking about different types of turning points is that it allows the analyst to see how the different large-scale parts function. A well-done classical film doesn’t just have exposition and a climax with a bunch of stuff in the middle. (Field calls that long second act the “Confrontation” in the diagram above.) I believe that once the setup is over, there is a stretch of “complicating action,” which often acts as a sort of second setup, creating a whole new situation that follows from the first turning point. The third part is the “development,” which often consists of a series of delays and obstacles that essentially function to keep the complications from continuing to pile up until the whole plot becomes too convoluted. The development also serves to keep the climax from starting too soon. The third turning point is the last major premise or piece of information that needs to be set in place before the action can start moving toward its resolution in the climax.

David uses this approach to large-scale parts in his online essay, “Anatomy of the Action Picture,” which discusses Mission: Impossible III.

TYPES OF TURNING POINTS

Returning to some of the examples I used in Storytelling, let’s see what sorts of changes their turning points involve. In most of these cases, the protagonist is aware of what is happening, but there are some exceptions or nuances.

1. An accomplishment, later to be reversed

Top Hat: end of setup, Jerry and Dale fall in love, but she soon conceives the mistaken idea that he is married to her best friend. (p. 28)

Tootsie: end of setup, Michael gets a job, but the results will throw his life increasingly into chaos. (p. 60)

Parenthood: end of complicating action, the parents seem to be making progress in solving their problems. (p. 268)

2. Apparent failure, reiteration of goal

The Miracle Worker: end of development, parents remove Helen from cabin, Anne states goal again. (p. 28)

The Silence of the Lambs: turning point comes at beginning of development, Chilton makes Lecter a counter-offer, removing him from the FBI’s charge. The FBI’s tactic has failed, but soon Clarice visits Lecter to pursue her questioning. (p. 123)

Here’s a case where we don’t see Clarice learning about Chilton’s treacherous undermining of the FBI’s efforts. A few scenes later she simply shows up to visit Lecter, and we realize that she has not given up her goal of getting information from him. Clearly a turning point can occur without the main character’s knowledge, but he or she will usually learn about it shortly thereafter.

Groundhog Day: end of development. Failure to save old man. No reiteration of goal, which is implicitly that Phil will continue to improve himself. (p. 147)

2a. Failure, new goal

Amadeus: end of complicating action, Salieri declares that he is now God’s enemy and will ruin Mozart. (p. 195)

Amadeus is an example of what I call a “parallel protagonist” film. Here Salieri is aware of his own decision, but Mozart never learns that his colleague hates him so. Parallel protagonists have separate goals, but they need not be aware of each other’s goals. The same would be true in a film with multiple protagonists, to the extent that they have separate goals.

2b. Failure, lack of goal

Groundhog Day: end of complicating action, suicidal despair. (p. 144)

Amadeus: end of setup, Salieri humiliated by Mozart, conceives strong resentment but no specific goal. (p. 191)

Parenthood: end of development, the parents are all resigned to their failures. (pp. 275-76)

3. Major new premise, reiteration of strategy

Witness: end of complicating action, Carter tells Book to stay hidden. (p. 29)

The Wrong Man: end of complicating action, Manny is freed on bail; he has the chance to try and prove his innocence. (p. 39)

Terminator 2: end of development, Sarah, Terminator, and John steal chip from Cyberdine, continue in their attempt to destroy it. (p. 42)

Amadeus: end of second development, Constanza leaves Mozart, allowing Salieri the access that will permit him to fulfill his goal of killing his rival. (p. 205)

4. Protagonist/Important character makes a decision, then changes or modifies goal

Little Shop of Horrors (1986): end of complicating action, Seymour agrees to kill someone to feed blood to Audrey II. (p. 29)

The Godfather: end of development, Michael says family will go legit, asks Kay to marry him. (p. 30)

Casablanca: end of complicating action, Rick rejects Ilsa’s account of her relationship with Victor. (p. 32)

The Producers: end of setup, Leo decides to join Max in committing fraud. (p. 38)

Tootsie: end of complicating action, Michael decides to start improvising Dorothy’s lines, setting up “her” success. (p. 64)

Back to the Future: end of development. Martie decides to leave a message for Doc warning him about the Libyan attack; the result is to save Doc from being killed. (p. 94)

Desperately Seeking Susan: end of setup, Roberta apparently decides to pursue Susan, change her boring life. (p. 166)

Such decisions obviously form the basis for turning points fairly frequently, and by definition the protagonist is aware of what is happening.

5. Major Revelation, new goal or move into climax

Witness: end of setup, Book is told the killer is a cop, changes tactics, flees. (p. 28)

Witness: end of development, Book learns partner has been killed, realizes he must act. (p. 29)

The Bodyguard: end of development, revelation of Nikki as villain, attack on house, death of Nikki. (p. 31)

Terminator 2: end of setup, John discovers the Terminator must obey him, sets goals of protection without killing and of rescuing Sarah from the asylum. (p. 41)

Terminator 2: end of complicating action, Sarah realizes that the war can be prevented, conceives goal of killing Dyson. (p. 42)

Tootsie: end of development, Michael’s agent tells him he must get out of playing Dorothy without being charged with fraud. (p. 69)

The Silence of the Lambs: end of setup, Clarice finds the body in the warehouse and realizes that Lecter is willing to help her. (p. 115)

The Silence of the Lambs: end of development, Clarice and Ardelia realize “He knew her,” the clue that will lead to the solution. (p. 126)

Alien: end of development, revelation that the “company” and Ash are prepared to sacrifice the crew; will lead to decision by survivors to abandon the ship and save themselves. (p. 299)

Such revelations usually involve the protagonist knowing what is happening, but I believe there are exceptional cases where the viewer learns something that the protagonist does not. This kind of revelation often involves either villains turning out to be allies or apparent allies turning out to be villains.

Take the case of Demolition Man. At 54 minutes into the film, about nine minutes before the end of the complicating action, the audience learns that the apparently benevolent Dr. Cocteau (Nigel Hawthorne), who has developed the new pacifist society of Los Angeles, is a ruthless villain. This moment isn’t the turning point that ends the complicating action; I take that to be the escape of the “Scraps,” the rebels who oppose Cocteau, from their underground prison. Most of those nine minutes consist of the hero, John (Sylvester Stallone) meeting Cocteau and going out to dinner with him. John shows signs of strongly disliking the new society, and he refuses to kill the rebels when they escape. Still, there is no sign that he considers Cocteau a villain. Rather, John thinks of himself as a misfit and expresses a desire to leave the new Los Angeles. The turning point that ends the complication depends on his assumption that Cocteau on his side, even if John considers the leader’s bland society to be unattractive.

The development portion is full of typical delays: the scene of John visiting Lenina Huxley’s (Sandra Bullock) apartment, where she invites him to have virtual sex, and the following scene of John exploring the odd, modernistic apartment assigned to him. At 74 minutes in, or about six minutes before the end of the development, John begins to learn of Cocteau’s true nature. He confronts Cocteau in the latter’s office and nearly shoots him. The scene where John tells the members of the police department who remain loyal to him that they will invade the underground prison to capture Cocteau’s violent agent, Simon Phoenix (Wesley Snipes) marks the end of the development, with a new, specific goal determining the action of the climax.

Here is a case where for a significant portion of the narrative the protagonist remains ignorant of something that the audience has been shown. Even here, however, John displays a dislike of Cocteau and what he has done to Los Angeles society. Classical films seem disinclined to show their heroes as thoroughly deluded. John’s underlying decency and common sense make him ready to distrust a leader whom everyone else, including Lenina, admire.

6. Enough information accumulates to cause the formulation of goals

Back to the Future: end of complicating action, goals of synchronizing with lightning storm, getting Marty’s father and mother together at dance. (p. 90)

Desperately Seeking Susan: end of complicating action. Information about gangsters and growing attraction to Dez lead to convergence of Roberta’s goals. (p. 170)

Parenthood: end of setup, in this case with multiple goals formed for four separate plotlines.

7. A disaster, accidental or deliberate, changes the characters’ situations/goals

The Wrong Man: end of setup, Manny is mistakenly arrested. (p. 39)

Jurassic Park: end of complicating action, Nedry shuts down the electricity grid of the park, letting the dinosaurs loose. (p. 32)

Jaws: end of complicating action; the attack involving his son makes Brody force the mayor to accept his original, thwarted tactic of hiring Quint. (p. 34)

Alien: end of setup, facehugger attaches itself to Kane. The goal conceived shortly thereafter is to investigate it and save him. (p. 292)

Alien: end of complicating action, alien bursts from Kane’s stomach; goal becomes to save the crew and ship. (p. 295)

Desperately Seeking Susan: end of development, Roberta’s arrest leads to a low point, and she opts to turn to Dez for help. (p. 172)

Amadeus: end of first development, death of Leopold, which Salieri later exploits in his plot against Mozart. (p. 201)

The Hunt for Red October: end of complicating action, Ramius realizes he has a saboteur aboard and needs Ryan’s help; Ryan starts planning actively to help him. (p. 233)

8. Protagonist’s tactics are blocked or he/she is forced to use the wrong tactics

Jaws: end of setup, Brody’s desire to hire Quint rejected. (p. 23)

Back to the Future: end of setup, Doc sets time machine’s date; after new large-scale section begins, attack by Libyans accidentally sends Marty back to 1955. (p. 85)

Groundhog Day: end of setup, Phil trapped in repeating time, goal of becoming a network weather forecaster destroyed. He soon opts for irresponsible self-indulgence. (p. 139)

9. Characters working at cross-purposes resolve their differences

Jaws: end of development, the three main characters bond, allowing them to cooperate to kill the shark. (p. 35)

The Hunt for Red October: end of development, Ramius and Ryan make contact, with Captain Mancuso’s help, they start working together. (p. 237)

10. A supernatural premise determines a character’s behavior

Liar, Liar: end of setup, Max wishes that his father would have a day where he is unable to tell a lie. Also end of complicating action, where Max fails to cancel the wish. (p. 38)

11. The protagonist/major character succeeds in one goal, allowing him/her to pursue another

Liar, Liar: end of development, Fletcher wins his court case, freeing him to try and regain his wife and son. (p. 39)

The Hunt for Red October: end of setup, Ramius learns that the silent feature of his new submarine works; he apparently intends some sort of attack on the US but is in fact plotting an elaborate ruse to defect. (p. 225)

These examples suggest that protagonists usually do know about the major events that form turning points, or they learn about them shortly after they occur. The main exception would seem to be when there are two major parallel characters, one of whom is to some extent villainous, as in the case of Amadeus, where one of the characters is duped. This reminds me of The Producers, where Max and Leo leave the theater early, convinced that they have succeeded in their goal of creating a box-office disaster. Lingering in the theater, the narration allows us to see the transition from audience disgust to fascination. Only after the audience comes into the bar where the two partners are celebrating do they realize what has happened (“I never in a million years thought I’d ever love a show called Springtime for Hitler!”) To understand the irony and/or humor in such situations, the film spectator must at least briefly know more than the main characters do.

The examples also confirm that character goals seldom endure unchanged across the length of a film. Revelations, decisions, disasters, supernatural events, and presumably others kinds of causes frequently cause major shifts in characters’ goals or at least in the tactics they employ in pursuing them. Even in what seems like a fairly straightforward thriller like Alien, the crew’s assumptions that they must loyally protect their spaceship are completely reversed at the end of the development, and the narrative turns into an attack on corporate greed and ruthlessness. Whatever one thinks of classical Hollywood films, they are usually more complex than the three-act model allows for.

Note: My title comes from Robert Southwell’s poem of the same name.

[July 11: Jim Emerson has made some insightful comments on this entry on his Scanners blog.]

Coming attractions, plus a retrospect

Invasion of the Brainiacs

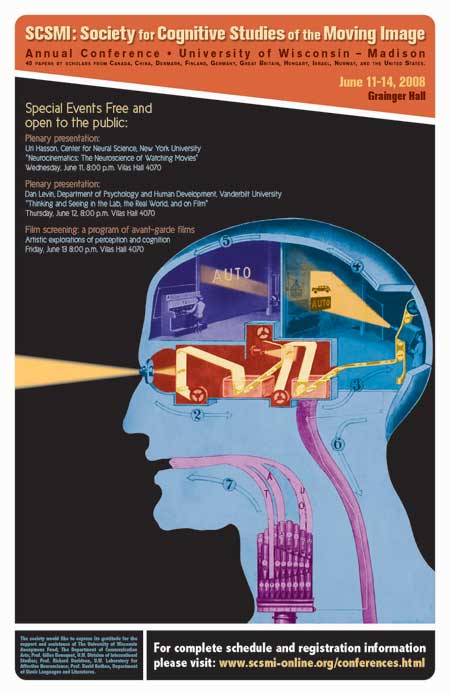

First, the event that will occupy us through next week: the annual conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image, a group founded in 1997. This year’s gathering brings researchers from Britain, Germany, Hungary, Israel, Turkey, Canada, China, and the Nordic countries, as well as many from the U. S. The meeting is here in Madison, from 11 to 14 June.

In over forty sessions, researchers will be talking about how we respond to movies, TV shows, and videogames. How has digital imagery changed our experience of cinema? How does film music enhance our emotional response to the story? How do films guide our visual attention to one part of the screen, and how much do viewers differ in this? How do we respond when movie characters behave inconsistently?

I’ve already blogged and bragged about our event here, but now I want to highlight four attractions. If you’re in or near Madison, you might want to stop by; and in any case, you might want to check the links mentioned below.

For some years Professor Uri Hasson of New York University’s Center for Neural Science has studied how the human brain responds during film viewing. Using fMRI techniques, he has discovered that Hollywood films, such as those by Hitchcock, have created remarkably similar responses across a variety of viewers. Art films, he says, may require just as much concentration, but they will elicit less convergent reactions. He’ll present the fruits of his research on June 11. You can learn more about Uri’s research here.

On June 12, Professor Dan Levin will lecture on “Thinking and Seeing in the Lab, the Real World, and on Film.” Levin has been actively studying how viewers’ concentration, watching a film or in real life, encourages them to overlook actions or changes taking place in front of them. He showed the power of “inattentional blindness” in his famous “gorilla-suit” experiments. Filmmaker Errol Morris recently interviewed Levin for The New York Times about continuity errors in films. You can read more of Dan’s fairly mind-bending work here.

On June 12, Professor Dan Levin will lecture on “Thinking and Seeing in the Lab, the Real World, and on Film.” Levin has been actively studying how viewers’ concentration, watching a film or in real life, encourages them to overlook actions or changes taking place in front of them. He showed the power of “inattentional blindness” in his famous “gorilla-suit” experiments. Filmmaker Errol Morris recently interviewed Levin for The New York Times about continuity errors in films. You can read more of Dan’s fairly mind-bending work here.

NB: 12 June 2008: In fact, the gorilla-suit experiment was conducted by Dan Simons, not Dan Levin. The last link takes you to Simons’ article. Both Dans work in the area of attention and “change blindness,” and they have collaborated on several projects. I apologize for the error.

There is a registration fee for the conference’s day events, but these evening lectures are free and open to the public. Each begins at 8:00 PM and will be held in 4070 Vilas Hall, 821 University Avenue.

The final night of the conference is devoted to a screening of experimental and avant-garde films that provoke questions about how we respond to cinema. There will be a discussion of them afterward, which will include two of the filmmakers, Joseph Anderson and J. J. Murphy. This screening, open to the public, starts at 8:00 PM in 4070 Vilas.

During the conference, one event is devoted to a discussion of Noël Carroll’s The Philosophy of Motion Pictures. This book is a remarkable effort to mount a systematic philosophy of film, TV, and related media. It’s full of provocative claims (e.g., that cinematic movement isn’t an illusion) and nifty examples. Noël is a polymath, with two Ph. D.s and more books and articles than anybody, including he, can count. Four other scholars will criticize some aspect of the book’s arguments, and Noël will respond. (One of those critics, Lester Hunt, is a philosophy prof here who maintains a wide-ranging website and a blog that often touches on film.) There should be some fireworks.

There are other brainiacs coming, many of them pioneers in this area: Joe and Barb Anderson, Murray Smith, Torben Grodal, Patrick Colm Hogan, Carl Plantinga, Paisley Livingston, Sheena Rogers, Dan Barratt, and Tim Smith (aka Continuity Boy), and too many others to include here. In all, I’m proud of what our local team, with the energetic Jeff Smith as point man, has accomplished in setting up this jamboree.

As regular readers know, I think that cognitive research into cinema holds great promise. It brings together a group of scholars from different disciplines who want to understand, in an empirical way, how movies work. The field is very young, and it’s not the only way to go; but it has a lot to contribute to our understanding of media, and maybe our understanding of the mind too.

Up to now SCSMI has been quite an informal group, but now we have a more systematic organization. We have officers, bylaws, and a sense that our research is coalescing around key ideas, about which there is lively and congenial disagreement. And, because there are more people who want to get involved, we’ll start meeting every year. The 2009 gathering is slated for Copenhagen.

I hope to dash off a blog entry in medias res. We’ll also do our best to introduce our colleagues from overseas and from the Coasts to the glories of brats, cheese, beer, and of course The House on the Rock.

By the way, you might want to check on this cognitive scientist, who claims that every one of us can see into the future (but only a little bit).

Kristin and the Comic-Book Guys (100,000 or so)

Speaking of gatherings of like-minded individuals, TheOneRing.net people have invited Kristin to take part in their panel on the upcoming Hobbit project at Comic-Con in San Diego, on Friday, July 25 at 10 am. She hopes to blog from among the multitudes.

A new website and a nervous DVD

There’s a new and attractive website up and running. Sponsored by the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, NYC, Moving Image Source is a vast project packed with links, research data, and essays about films both classic and contemporary. The first posse of writers includes Michael Atkinson, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Ed Sikov, Melissa Anderson, and other luminaries. The topics range from Andy Warhol and Howard Hawks to Werner Herzog (an interview). Steered by Dennis Lim, this is bound to be an essential watering hole for everybody interested in film history and criticism.

Speaking of film history, an important film is coming to DVD. Robert Reinert’s 1919 Nerven, which I wrote about in Poetics of Cinema, has been restored by Stefan Drössler and his crew at the Munich Filmmuseum. This is one of the strangest movies of the silent era. The plot, as Chris Horak points out in his accompanying essay, is steeped in Spenglerian melancholy, reminding us that Expressionism could be politically conservative as well as revolutionary. The visuals are at once monumental and unstable, like boulders teetering over a precipice. I try to analyze them in another contribution to the DVD booklet. Drössler has contributed an essay on the process of restoration.

Nerven was a box-office fiasco and never achieved the fame of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. In a way, it is more disturbing than that official classic because Reinert’s alternation of frenzy and somnambulism takes place in a more or less solid world, like ours. Frantic scenes of street fighting mix with brooding images of a bourgeoisie sliding into religious possession or straight-up lunacy. It is not every day that you see a movie that begins with a man throttling his wife and then lovingly refilling their parakeet’s water cup. If you’re a fan of wild deep-space imagery way before Citizen Kane (as above), this one’s for you. And yes, it will have English subtitles.

Nerven will be available later this summer from the Filmmuseum’s shop. It joins an abundance of other fine DVD titles, such as Borzage’s The River and a collection of Walter Ruttmann’s works.

Retrospect: In Europe they do things differently?

Because we see a very thin slice of foreign-language cinema, audiences underestimate the extent to which European films often imitate Hollywood. Surely the cultures of the great continent would never stoop to the crassness of our movies? A trip to any multiplex in Paris or Berlin would probably disabuse people of this notion. The current instance is the reigning French hit Bienvenue chez les ch’tis (Welcome to the Sticks), apparently a fish-out-of-water tale that would induce groans from our intelligentsia.

Kristin has already written about this phenomenon here. I found some supporting evidence last week while scrabbling through an old folder for our Film History revision. It was a 2002 pamphlet from the Filmboard of Berlin Brandenburgh GmbH, a publicly limited company coordinating German state funding. The text laid out a set of guidelines, in English, for productions that the Filmboard would support. After explaining that the judges must consider financial return as well as cultural factors, the guidelines insist that the quality of the screenplay is of paramount importance. What makes a good screenplay?

The success of a film decisively depends upon whether the audience can engage enthusiastically with the actors on the screen. An audience looks for strong central characters whose fates it can identify with. The hero or heroine should have goals and needs and should have an emotional effect on an audience. Further dramaturgical criteria:

There must be a concrete goal, which at the end of the story is either reached—or not.

There should be a risk involved for the central character in not reaching his/her goal.

The goal is perhaps difficult to reach, and the struggle to do so should bring the central character into conflict. The audience sympathizes with the story when, for example, the hero or heroine follows the wrong goal, makes mistakes, or experiences a crisis.

This sounds easy to understand. But writing screenplays is more complex.

*The central character should have subconscious needs. He/ she should lack an important human quality and only gradually experience this for him/herself.

*At the end of the story the central character should come to know his/her unconscious needs and gain a satisfactory recognition about him/herself and life in general, which can be formulated in the emotional subject matter of the film.

*The central character should undergo a process of development, as characters that do not develop are boring. Moments of decision in stories are the key for good character development.

The passage lays out a lot of what U. S. screenplay manuals have been asserting for decades (notions that Kristin and I have analyzed in various books). This is still more evidence that the Hollywood model, with its goal-oriented chain of causes and effects and its protagonist who improves through a “character arc,” holds sway far beyond our own shores. Whether it should be so widespread is another question, but for Kristin and me, this template or formula is a bit like the sonnet or the well-made play: a form that can yield results good, bad, and indifferent. The point is to take the form seriously enough to understand what makes it work.

From Comic Book Guy’s Book of Pop Culture (New York: HarperCollins, 2005), n.p.

Reflections in a crystal eye

Whew! After many months of work, we finally sent in our revised third edition of Film History: An Introduction. Elsewhere on this site you can read about its earlier incarnations, and we expect to say more about it as it approaches publication in February 2009. But writing this tome isn’t as fast as webposting, for sure.

So how did we celebrate? A meal out and Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (after about sixteen trailers for Paramount and DreamWorks releases). As with Beowulf and Ratatouille, we talk/ write about it together, but not in dialogue form. Kristin gets her time at the podium, then David. And there are of course spoilers.

Don’t even mention pyramid power

Kristin here:

I enjoyed the first half or so of IJatKotCS, but gradually it occurred to me that it wasn’t really building. It was violating the basic law of suspense films, which is to make your villain threatening and the things at stake important. Sure, in the B-film serials that inspired the Indiana Jones films, the premises are ludicrous. But so are the sets and the acting and just about everything about them, because they were so cheaply and quickly made.

With Indiana Jones, these adventure films become high-budget productions with the biggest, best special effects that money can buy. They star actors who have won or been nominated for Oscars. Moreover, the scripts don’t imitate the clichéd, bare-bones plots of the Bs. These are complicated stories that not only move ahead at a pace undreamed of in the serial days, but they toss in many little details and in-jokes in the backgrounds. With Steven Spielberg directing, one expects the non-stop thrills to also make sense, at least in a casual way.

Eventually I became distracted by the fact that certain things stopped making sense to me. Most obviously, what is at stake with that crystal skull? The Soviets want it, and Irina Spalko informs Indy that it’s to make a psychic weapon. Hmmm. And what is that, exactly? She doesn’t explain, and it’s clear that the Reds don’t know enough about the crystal skull to really understand what they’d do with it. In fact, they need Indy to help them every step of the way, and after a certain point his expertise becomes irrelevant, and they’re all dependent on Prof. Oxley to lead them to the kingdom.

I suspect most people’s reaction to her “psychic weapon” announcement is to think she’s nuts, deluded. The skull has apparently driven Oxley crazy (John Hurt playing loony as only he can do). Or did that just happen because he was locked in a very grim Peruvian insane asylum? We’re allowed to go on wondering if the skull has any psychic powers until the scene where Indy gets strapped in a chair and forced to stare into the eyes of the skull. The fact that he is so profoundly shaken by the experience finally shows that the object does have some sort of psychic effect.

But how could it be a weapon? Earlier an atomic bomb has gone off, and that’s engineered by our side, the good guys. How could a psychic weapon top that? Are the Russkies going to strap all the American soldiers one by one into chairs and make them stare into the skull? Talk about creeping Communism!

Spalko can’t explain it to us, since she is trying not only to get the skull but to figure out its secrets. Up to the very end, she says “I vunt to know.”

Of course, ignorance on the part of the villains need not be a problem. In Raiders of the Lost Ark, the Nazis didn’t know what power the Ark of the Covenant contained until it was too late. At least there, though, we understand from early on that the Ark really is dangerous in what is presumed to be a physical way. Moreover, there the villains were Nazis. We know what horrors the Nazis perpetrated on the world, and we and our allies actually went to war with them. With the Soviets, it was largely a long, tense brinksmanship. Luckily we never found out what a war with the USSR would be like. Today, well after the Soviet Union imploded on its own, the paranoia over reds in our midst seems quaint in an adventure film. Early on Indy and his department chair (Jim Broadbent) lose their jobs, and in a glum scene they deplore how Americans’ irrational fear of Communism has caused it. Yet soon after we discover that there really are Communist spies looking to steal America’s secrets. A mixture of tone, to say the least.

In Raiders, the Nazis seemed to be part of a worldwide network of spies. Spalko seems to be operating with only the group of soldiers that accompanies her. She never reports back to “headquarters.” One wonders if maybe Khrushchev sent her off on a wild-goose chase to get rid of her for a while.

Professor Jones Flunks Archaeology 101

One thing that distracted me and that seems to vitiate the notion of real threat in IJatKotCS is the fact that it’s based on hoaxes and wacko theories. At least there’s some archaeological evidence that elements of the Bible have their bases in real events. There may have been some sort of Ark of the Covenant and a Holy Grail. But to base the premise of the film on Chariots of the Gods (Erich von Däniken, 1968) and crystal skulls gives it a certain ludicrous quality that wasn’t there in the earlier films’ premises, wild though they were.

The film flits lightly past the nuts and bolts of how that Kingdom of the Crystal Skull came to be. Presumably, as in Chariots of the Gods, the aliens arrived and traveled around giving instructions on how to build such things as pyramids and Easter Island statues. The room in IJatKotCS where artifacts from Egypt, China, and other ancient cultures are gathered implies that long ago the aliens visited the earth, collected examples of the fruits of their teachings, and … instead of putting them in their space ship to take home, they left them in a chamber that would be crushed when the Kingdom built over the space ship is destroyed. (Don’t get me started on where the ancient Peruvian warriors who pop out of the walls to briefly chase the good guys came from.)

Then there are the skulls. The “real” crystal skulls held in museums, most notably the British Museum one referred to in the film, have been shown to be objects made in modern times, probably within the past 150 years. Those skulls, however, are of normal proportions. The ones in the movie are strangely elongated. Head-binding, Indy offhandedly explains.

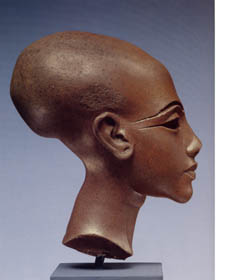

There’s another apparent source for this, one that I’m familiar with. The pharaoh Akhenaten, famed equally for inventing monotheism back in the 14th Century BCE and for being married to Nefertiti, has been the subject of much far-out speculation. The art of his era, the Amarna Period, shows his family with strikingly elongated skulls, as in the quartzite head of the statue of a princess at the left. Head-binding, various medical syndromes, and pictorial stylization have been posited. One imaginative claim has it that Akhenaten and his family actually were space aliens.

There’s another apparent source for this, one that I’m familiar with. The pharaoh Akhenaten, famed equally for inventing monotheism back in the 14th Century BCE and for being married to Nefertiti, has been the subject of much far-out speculation. The art of his era, the Amarna Period, shows his family with strikingly elongated skulls, as in the quartzite head of the statue of a princess at the left. Head-binding, various medical syndromes, and pictorial stylization have been posited. One imaginative claim has it that Akhenaten and his family actually were space aliens.

In fact, we still have no convincing explanation as to why this style occurred in Amarna statuary. (The Egyptian expedition I work on is at Amarna, the ancient city built by Akhenaten, and I work with statuary fragments found there.) The film, of course, doesn’t bring Akhenaten into it, though I think I did spot a photo of the seated statue of him in the Louvre on the chalkboard of Indy’s classroom. Akhenaten is a figure of considerable interest to New Age enthusiasts. Every now and then a group of people in white robes and turbans actually come to Amarna to worship in the ruins of the temples.

The ancient-aliens-visited-earth premises and the less explicit references to Amarna are woven in with El Dorado and with the Roswell myth that modern aliens visited earth. There’s even a nod to the Alien Autopsy film that David discussed in an entry on “Film Forgery.” The film also brings in the mysterious Nazca Lines, the shapes carved into the earth over which Indy and Mutt fly as they arrive in Peru. Some have claimed that the lines are runways for alien ships, and I think the film tries to imply that. But why would a flying saucer that takes off (and presumably lands) vertically need a runway, let alone one shaped like a monkey or any of the other complex figures that survive today?

The silliness that hovered near the edge of plausibility in the earlier films has crossed that line. At least the first and third movies made an effort to ground their mcguffins in real history and real places. Tanis, where a lengthy portion of Raiders takes place, is a real set of ruins in Egypt. In Last Crusade, Indy and his father can spar by showing off their knowledge of actual or apparently actual history. (I’ll leave it to the comments on the “goofs” page of the Internet Movie Data-base to deal with the transfer of the Mayans from Central America to Peru.) Each of those films was a race to prevent a lethal object falling into the hands of those who would both desecrate it and use it for evil purposes. Crystal Skull is a race to figure out what the apparently dangerous object is, given that the only person who knows, Oxley, is conveniently rendered unable to explain it.

Indy and his group win the race and get to the chamber ringed by crystal skeletons first, so that Spalko is effectively defeated before she gets there, though she doesn’t know that yet. Which brings me to the last thing that baffled me. Why, if the thirteen skeletons were separate beings, as they are depicted in the wall paintings, do they merge into one before being restored to life? Apparently the space ship was waiting to depart because, unlike in E.T., the aliens didn’t want to leave one of their number behind. But is there more than one alien left at the end to depart in the huge ship? Does the ship wait simply because it brought only one passenger, and that passenger can’t start it moving until it gets its head back? Yet surely there would have had to have been a crew to help build all those ancient wonders and bring the evidence back to the “kingdom.”

Maybe a second viewing would clear all this up, but the old serials didn’t need second viewings to be understood—and neither did the earlier Indy films.

The Spielberg Touch

DB here:

Kristin’s critique reminds us that the classic Hollywood structure demands a linear logic, but not a plausible or even particularly deterministic one. Like other action films, Crystal Skull follows the template she pointed out in her New Hollywood book: four parts, the first three running about half an hour and the climax somewhat shorter, the whole capped by an epilogue. It goes to show the difference between plot structure and the events of the fictional world that structure presents. The structure can make preposterous or puzzling chains of action seem acceptable—especially if it whisks them along.

I was taken, as usual, by Spielberg’s brisk direction. In the last decade he’s had a remarkably hot hand. Amistad, Saving Private Ryan, A. I., Minority Report, Catch Me If You Can, The Terminal (much underrated, I think), The War of the Worlds, and Munich are very strong movies. For all their faults (sometimes those slippery endings), they would be enough to establish a younger director at the very top. So I was watching for what I take to be The Spielberg Touch.

His staging is still solid and resourceful. When he has to let people talk, he moves them around the set, avoiding those dreary passages of stand-and-deliver that most directors today resort to. (Check the dialogue scenes from The Matrix Reloaded.) In a soda fountain, he lets your attention drift from the exposition between Mutt and Indiana to the teenyboppers behind them, to the point where I was distracted from Mutt’s explanation of those muddled plot premises Kristin points out.

Spielberg has said that he favors lengthier shots than are typical today. That’s true in most of his dramas and comedies, but here the cutting is fast. The shots average 4.6 seconds by my count, which is about the same as the other Indiana Jones films (1). But whatever his shot length, Spielberg doesn’t resort to choppiness, the sort of image-snatching that typifies today’s mainstream cinema. He’s one of the few filmmakers working today (Shyamalan is another) who tries to give most shots a distinct arc—a beginning, a middle, and an end.

Granted, most shots in any movie will develop or progress, even if a character just steps forward or raises an eyebrow at the end of a spoken line. But Spielberg enriches his shots in the way that the old adage suggests: The only problem of direction is to prepare the audience for what is going to happen next.

The ambitious Spielberg shot starts with something that links precisely to a previous shot, then develops a visual or narrative premise of that, then ends with a firm point of information that carries us into the next shot. His main tools for building the shot are are spatial depth and camera movement.

Linking the shots, in multiple ways

In War of the Worlds. the protagonist Ray is hurrying toward the center of his neighborhood, where people are gathering. He passes a garage, where the mechanic Manny and his assistant are trying to fix a burned-out ignition. As Ray strides by, he suggests changing the solenoid, and Manny agrees. This becomes important later, when Ray will seize the vehicle because it’s the only civilian car that’s working.

Spielberg binds his shots together in this way. The end of the first shot shows Ray, along with others, hurrying to the left. Cut to a shot from inside the garage, with a silhouette in the foreground bending over a car’s engine. Ray becomes visible in the distance.

Ray’s appearance and reappearance link the shots, while Spielberg’s composition has prepared us for a dialogue between Ray and the man, as yet unseen, in the foreground. Cut to a moving point-of-view shot of Manny rising and turning to Ray (us) and explaining what has happened.

Reverse shot of Ray, still trotting along, over Manny’s shoulder as he suggests changing the solenoid. As he goes on, cut: The moving shot now detaches itself from Ray’s point of view and shows Manny ordering his assistant to change the solenoid. The assistant bends over the engine.

Cut to another driver bent over his engine. This reiterates the story point that everybody’s car has stopped, but it also echoes the end of the last shot (and the beginning shot of Manny in silhouette). Crane up slightly to pick up Ray walking leftward in the distance, an echo of the foreground/ background interplay of the Manny/ Ray shot.

How to develop this shot? We follow Ray, along with a skateboarder, to the intersection, where Spielberg introduces a new element. The shot gradually brightens and as Ray moves to the major intersection, rays of light wash out the image.

The next shot will repeat this pattern, from darkness to rays of light, so that the following shot can start with a burst of light that envelops Ray.

Then a new story component, involving Ray’s two buddies, comes in from the foreground. Their conversation with Ray will get a tracking shot devoted to it, but it will end with a story point….and so on.

Spielberg maps his story points quite precisely onto the beginning/ middle/ end of his shots so that they link smoothly with one another. Each camera movement or depth pattern leads to a distinct revelation, sometimes a fresh one, sometimes an expansion or specification of information we’ve already received. This is one reason he uses so many matches on action, even in simple dialogue scenes. The last bit of one shot can serve as the premise for the next if its movement can be carried over the cut.

Something extra between the shots

Sometimes that last bit is a surprise. Something pops up in the foreground or on the frame edge, or the camera slides over or back to reveal something that impels us toward the next shot. In Crystal Skull, Indy swiftly empties a refrigerator, hurls himself in, and as he yanks the door closed it swings toward us revealing the label LEAD LINED before it shuts . . . and the atom bomb goes off.

Sometimes the end-of-shot payoff sets up a motif that itself will be paid off later. When Ray runs from the spindly, towering alien vehicle, he ducks around a corner and halts, but Spielberg’s framing gives us time to see the fleeing crowd reflected in a shop window. Spielberg introduces a new motif when Ray, stepping out from behind a car, is standing near a man taking a photograph.

Shortly, another reflection, this time supplying both action and reaction: the alien walker seen in in a shop window as people inside stare at it. And again we have photography, when, in a shot echoing the earlier one, a man upstages Ray and films the creature’s advance with a video camera.

At the climax of this string of shots, the creature’s approach is again given in reflection, only now it’s Ray standing alongside it (bringing together two elements previously kept apart, Ray and the reflection of the aliens). After the creature sends out its death vibes, the video camera falls into the shot, showing us, in its own version of reflection, the fleeing crowd–the subject of the first reflected image we saw.

Following the end-of-shot hooking principle, the image on the video screen will link to the next shot we see of the people fleeing in panic. My larger point is that the braiding of motifs—reflections, photography—ends with them knotting together in a single image, the shot of the video camera. This sort of patterning was something that Eisenstein both theorized and practiced; he called it “wickerwork” montage construction. Spielberg has, in the context of American action pictures, rediscovered how powerful it can be.

He brings the same shot-by-shot fluency to dialogue scenes. A small scene in The Terminal shows Victor tussling with an official over his passport. Spielberg sets it up with our old friend, over-the-shoulder shot/ reverse shot, but he gives us two bits of business: The official slipping Victor’s plane ticket into a pouch, and Victor grabbing back his passport.

Match on action as the official continues to put away the ticket and demands the passport. A change of angle to a profile view adds a little amusement to the scene.

In reverse-angle Victor warily extends the passport. Cut back and forth as the two men tug on it, the action accentuated by a squeezing sound.

The official wins, and he slips the passport into the pouch. Spielberg gives us a variant on the reverse-angle on Victor, adding a fast rack-focus that resolves the scene with a neat snap.

In making even small gestures engage us in a visual flow that is rhythmically arresting, Spielberg displays craftsmanship of a high order. Despite his influence on a generation of filmmakers, this level of skill is rare today. If this be Storyboard Cinema, make the most of it.

I’ve already gone on too long, but I want to suggest that this cunning arc of interest, of doling out story points within shots and across cuts, also quickens his chase scenes. We say that his action scenes are clear, and partly that comes from his patient willingness to design long shots and overall views that keep us oriented. But these sequences also draw us in because shot by shot they build carefully, with little transitions—a glance, a gesture, a shift of focus or framing—that crisply link to what we will see next.

I saw a little of this crispness and fluidity in the pursuits of Crystal Skull. They can’t help but seem fairly stale, since Spielberg is competing with himself and with directors who learned from him (e.g., John McTiernan in Die Hard). And as per convention, bad guys have bad aim and they run out of bullets at an awkward moment. Yet the chases still piled complication upon silly complication, from ants and rapiers to cliffs and waterfalls, often set up at the end of one shot and paid off at the beginning of the next, which also sets up another.

The Spielberg Touch includes some visual wit. Everyone remembers the shot from Jurassic Park showing the T-Rex pursuing the Land Rover, as reflected in a side mirror saying “Objects in mirror are closer than they appear.” I think the habit goes back to Jaws, possibly still Spielberg’s best movie: the billboard with the graffiti and of course the rise of Bruce from the sea as Brody is scooping chum over the side. To make audiences gasp and laugh at the same time is no mean feat.

Crystal Skull seems to display less of this wit. The glimpse of the Ark of the Covenant in the warehouse and especially the montage of a squeaky-clean suburbia about to be vaporized were typical Spielberg, but I wanted more. Maybe a second viewing will show me that more.

But I was glad to see the Roswell ingredient here, and to learn that Indy did his duty in July 1947, even if he wasn’t there for the alien autopsy.

Faces and light

Finally, a little image-cluster that recurs in Spielberg’s work intrigues me. It was in Close Encounters that I first noticed his fascination with linking faces and beams of light. In that movie people just watch, transfixed by the luminous aerobatics of the vagrant UFOs and then eventually by the four-alarm light show pumped out by the mother ship. Then there’s the iconic image of Elliott staring at E. T.’s luminous digit, and the radiance of the church in the above scene from War of the Worlds.

Light beams can be punishing too. They melt faces in the first Raiders and blow a woman’s face to bits in War of the Worlds. They’re back again here—sprayed out by an alien intelligence and infecting the bad guys. Poor Irina Spalko, played with pelvic-thrust relish by Cate Blanchett, absorbs the rays through her eyes before detonating in one of those Armageddons that are obligatory in today’s megapicture. (Why do blockbusters have to include literal blockbusters?)

Maybe a critic in the vast Spielberg literature has discussed this dynamic between uplifting light and damning light, the enthralled face and the blasted one, characters spellbound by light and doomed by it. My hunch is that it will take us into religious and/or New Age territory.

(1) I get 4.3 seconds for Raiders, 3.5 for Temple of Doom, and 4.7 for Last Crusade.

Minority Report.

Some cuts I have known and loved

DB here, belatedly:

We’ve been so busy revising our textbook, Film History: An Introduction, for its third edition that we’ve had no time to see new movies, let alone blog on our regular schedule. To those loyal readers who have been checking back occasionally, we say: Thanks for your patience. An entry that should intrigue you is in the works, possibly to be posted very soon.

In the meantime, here’s an item on a subject I’ve been meaning to slip in at some point. It’s a tribute to cuts I admire.

Warning: Superb as Eisenstein’s, Ozu’s, and Hitchcock’s cuts are, I’m deliberately leaving them out. Too obvious!

Kata and cutting

Okay, Kurosawa is an obvious choice too, but I can’t pass up some of the first outstanding cuts I noticed in his work, back when I was projecting movies for my college film society. The cuts occur during the climactic battle of Seven Samurai (1954).

As is well-known, Kurosawa shot the sequence with several cameras using different focal-length lenses. What is less often acknowledged, I think, is the power of certain cuts as they combine with fixed camera positions. In his last films, Kurosawa would rely strongly on long-lens shots that pan over the pageantry of his crowd scenes, but here he exploits static frames.

In the eye of the battle, Kambei fires his arrow in one shot, and a horseman falls victim to his marksmanship in the next. So far, so conventional. But what’s unusual is that we don’t actually see the arrow hit its target. Kambei fires, and Kurosawa cuts to an empty bit of the town square, churned with mud and dimly visible through horses’ legs. Only after an instant does a fallen bandit skid into the telephoto frame.

The same thing happens when Kambei shoots his second arrow: we must wait for the victim to plunge into the frame.

The result, I think, is a sense of exhilarating inevitability. The camera knows that the horseman will fall, and it knows exactly where. That’s a way of saying that Kurosawa’s visual narration fulfills our expectation, but with a slight delay. The empty frame prompts us to anticipate that the man will be hit—why else show it?—and we have a moment of suspense in waiting to confirm what we expect. Moreover, the force of Kambei’s arm is given us through a principle of Movie Physics: motion communicated to another body is magnified, not diminished, and the fixed frame allows us to see just how far the bodies are propelled. The arrow must have been Homerically powerful if it sends these men to earth with such impact.

Most directors would have panned to follow the victim as, wearing the arrow, he tumbled off his horse and hit the ground. This choice would have been natural given the multiple-camera situation. Instead Kurosawa had his camera operators frame the exact spot the stuntman would hit and wait for the action to hurtle into the shot. The patient expertise of Kambei’s marksmanship has its counterpart in the confidence of Kurosawa’s style. (1)

The moving image, Mr. Griffith, and us

Then there’s Intolerance (1916).

The Musketeer of the Slums is trying to seduce the young man’s wife, the Dear One. He pretends he can retrieve her baby. But his earlier conquest, the Friendless One, has followed him to the tenement, and at the same time the Boy has learned about the Musketeer’s visit. As the Musketeer attacks the Dear One, the Boy bursts in. The two men struggle and the Boy is momentarily knocked out; the Dear One has swooned. So no one sees what really happens next: From the window ledge the Friendless One fires her pistol and downs the gangster. She flees, and the boy believes that he is the killer. He will be charged with the murder.

Here’s what I admire. Griffith sets the situation up with his usual rapid crosscutting—the Musketeer and the Dear One struggling, the Boy returning, and the Friendless One crawling out on the ledge. When the fight starts, Griffith shows the Friendless One growing wild-eyed at the window. She fires once, and Griffith gives the action to us in three shots: a medium shot of her in profile, a medium-long shot of the pistol at the window (irised so we notice it), and a long-shot of the room, as the Musketeer is hit.

Griffith repeats the series of shots when the Friendless One fires again.

This time the Musketeer staggers out to the hall and dies. Neatly, Griffith gives us three more shots, but omits the setup showing the Friendless One. Cut to the curtains again, with her hand waving the pistol, then to another long shot of the room as the gun is tossed in, and finally to a close-up of the pistol landing on the floor.

If you’re looking for a pattern, the pistol in close-up is in effect substituted for the shot of the Friendless One at the start of each cycle. But I’m most interested in the shots of the pistol. The first one at the window goes by at blinding speed—ten frames in the two prints Kristin and I have examined. (2) That works out to a bit more than half a second, if you assume 16 frame per seconds as the projection rate, which was common at the time.

Okay, fussy, but I’ve already confessed that I turn into a frame-counter, when I get the chance. The second shot of the pistol poking out of the curtains, parallel to the first, is also ten frames long. Griffith seems to have been a frame-counter too.

What’s most remarkable is that the long-shot of the pistol being flung into the room is even briefer than these closer views—only seven frames long, or less than half a second at 16fps. As a nice touch, the close-up of the pistol landing in the corner is twice that (15 frames).

In the decades that followed, directors would believe that long shots shouldn’t be cut as fast as close-ups, so the Intolerance passage can strike us as a typical Griffith misjudgment. But I admire his willingness to cut long shots so fast. It certainly creates a percussive accent. In case we didn’t catch the story point, the close-up of the pistol hitting the floor clinches it.

This is the sort of sequence that the Soviet filmmakers probably learned from. They may even have gotten ideas from Griffith’s interspersed black frames (two by my count) before each of the shots of the pistol thrusting out of the curtain. (3)

Behind the desk

Speaking of the Russians, one of my favorite cuts in Pudovkin’s movies comes during a confrontation in The End of St. Petersburg (1927). The somewhat oafish young worker known only as the Lad, who has sold out his comrades, attacks the boss Lebedev in his office. He seizes the boss and shoves him down, jamming him between his desk and the window. We see the action from one angle and then what seems to be an opposing angle.

Actually, this is a big discontinuity. Using the desk, the telephone, and the window as reference points, we can see that in the first shot, the Lad moves in from the left side of the desk to push the boss down. In the second, he has come in from the right side and Lebedev’s head is pointing in the opposite direction. We can see the weirdness of this more clearly if we simply flip one of the frames: now it looks like a consistent change of angle.

Pudovkin has created an impossible event. But the cut gives the strong sense of graphic conflict that the Soviets (not just Eisenstein) sought, creating a kind of visual clatter to underscore the violence of the action. It’s possible that Pudovkin actually flipped a “correct” framing to create the disjunction, as some of his contemporaries did. (4)

Meg, all aflutter

Pudovkin’s cut reminds us that filmmakers can get away with a lot if they change the angle drastically. It’s harder to spot a cheated element or a mismatch if the new shot makes us reorient ourselves. Why does this happen? That’s a subject for research, as I’ll suggest at the end.

Here’s another tricky item. In Kate & Leopold (2001), Kate has brought her time-traveling guest to an audition for a butter commercial. In the studio, he’s behind her as she tries to convince her colleagues to watch him. As she talks, she first watches Leopold in the monitor above them, then swivels to talk to her boyfriend and other suits. The camera positions change 180 degrees.

This drastic shift works to prepare us for a remarkable cut a little later. Kate waves her hand, saying she only needs two minutes. She pivots her body, moving her hand downward.

Cut 180 degrees to a setup similar to the one we’ve seen earlier: She drops her hand to her side as she swings to us.

The gesture is smoothly matched. The only trouble is that it’s executed by the wrong hand. In the first shot Kate is wiggling her left hand, but in the second, it’s her right hand that continues the movement and drops to her hip.

I don’t think that many people would notice this. Indeed, when I first saw the film, I felt a bump hereabouts, but when I watched it over again on DVD, it looked fine to me. Then I watched it again and saw what was wrong. Even then, I thought I might be hallucinating. It’s one of the trickiest cheats I know of, and it’s beautifully done.

The real question is: Why don’t we notice it? We usually say, “Because we’re watching the story and ignore little irregularities.” But that’s not very satisfactory. Why isn’t the wave of Kate’s hand part of the story? We certainly notice it as expressing her attitude—hence as part of the story. And if you didn’t notice the disjunction in my End of St. Petersburg example, the same question arises: Isn’t the Lad’s attack on the boss the very story action we’re watching?

Consider the alternative. If director James Mangold had matched the left hand, it would have to cross the center of the frame as Kate pivots, shifting from screen left to screen right before landing at her hip. It would have been ostentatious and somewhat graceless, and perhaps that would have been distracting. So the mismatch is perhaps a line of least resistance, a compromise–as so many stylistic choices are.

In addition, Kristin suggests that our pickup is made easier by the placement and action of the hand. In both shots it’s quite central and moving in the same direction at the same rate, so that it’s easy to read as a graphically continuous element across the cut.

Perhaps too the fact that we’re switching our position 180 degrees leads us to expect, wrongly, the sort of reversal we get here—the way that we think our reflection in a mirror is the way we really look. And of course the earlier 180-degree switch, in which no mismatch occurs, probably serves to prime us for the shift in orientation this provides.

Mangold doesn’t mention the cut in his director’s commentary on the Kate & Leopold DVD, but when I asked him he said: “I think of shots as blocks, like legos or words. I don’t want them to resolve–come to an end. . . . Movement cuts work as long as the action is somewhat similar. The tough continuity cuts when you have a mismatch are the still ones.” Even if the mismatch here was accidental, it works very well. More generally, like other mismatches this one obliges us to think about what we see and what we don’t see when we watch a movie.

Hawks’ eyes

Among the many pleasures of Howard Hawks’ movies are their lovely matches on action. Of course his editors had a lot to do with this, but Hawks clearly had to provide the right footage so that it could be precisely matched. Bringing Up Baby (1938) yields a crisp cut as Susan, perched on the constable’s desk, strikes a match. (I show the cuts from a 16mm print; enough of this video stuff.)

Here Hawks seems to rely on what’s been called the two-frame rule: If you’re going to match on action, overlap the action by two frames to show a bit of the action again. This allows the audience time to absorb the fact of the cut and then to see the action as continuous. But Hawks could be quite cavalier about his matches as well. The golfing scene from Bringing Up Baby is full of wild cuts.

The caddies advance and recede, Susan and David are caught in different postures, and at some cuts they’re striding across different parts of the course. These cuts have a swagger about them, as if Hawks is daring us to spot his outrageous cheats. How many of us do?

All these trompe l’oeil effects can be studied psychologically, and prominent researchers who have tested such effects in the laboratory are attending our 11-14 June meeting of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. Dan Levin studies discontinuities in film from the standpoint of “inattentional blindness”; here he’s interviewed by Errol Morris. Barry Hughes of Arizona State University at Tempe has probed the two-frame rule, and he’s talking in Madison as well. Go here for more information; I’ve plugged the event previously here.

Next time, we expect: Secrets of film restoration.

(1) Kurosawa has prepared us for this passage when Kikuchiyo’s sword attacks the bandits earlier in the sequence. There too a shot of his flailing stroke is followed, after a pause on a patch of mud, by a falling horseman. But the calm deliberateness of Kambei’s drawing of his bow enhances the sense of inevitability, I think. Kiku does his damage through furious energy, but Kambei hits his mark thanks to a mature warrior’s almost contemplative precision.

(2) Forget checking these frame counts on DVD. I get several different counts, depending on the player I use. For reasons discussed here, DVDs don’t preserve the original film frames, and in a fast-cut passage you can lose any sense of how many frames the shot lasted.

(3) By the way, Griffith died on 23 July 1948, my first birthday.

(4) For more on this extraordinary movie’s use of discontinuity editing, see Vance Kepley, Jr., The End of St. Petersburg (London: Tauris, 2003).