Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

Truly madly cinematically

DB here, still in Hong Kong:

You are a film director. How do you convey to an audience that a character mysteriously sees hidden personalities in other characters?

Filmmakers are problem-solvers, at least sometimes, and I’ve argued elsewhere that we can often explain their creative choices as efforts to pose and solve problems. I ran across an intriguing example during my stay here in Hong Kong. I interviewed Tina Baz, the editor for Johnnie To’s film Mad Detective (2007), which I blogged about from Vancouver in October.

Tina has a fascinating history. Lebanese and French-educated, she attended art school in Beirut and film school in Paris. Armed with a maitrise from the Sorbonne, she began editing. Over a dozen years, she has built up an impressive career. She was editor on The Mourning Forest (2007), A Perfect Day (2005), and several other high-profile projects.

Tina has a fascinating history. Lebanese and French-educated, she attended art school in Beirut and film school in Paris. Armed with a maitrise from the Sorbonne, she began editing. Over a dozen years, she has built up an impressive career. She was editor on The Mourning Forest (2007), A Perfect Day (2005), and several other high-profile projects.

Mad Detective was Tina’s first film for Johnnie To, as well as her first experience with the Hong Kong crime genre. She was accustomed, she says, to the more psychologically-driven narratives of French cinema, and she had to work in a new way during the seven weeks it took to edit the film. This is an unusually long editing time for Hong Kong filmmaking, and it reflects the complicated tasks this film set her.

If you haven’t seen Mad Detective, you will probably want to stop reading. The scenes I’m discussing come fairly early in the film, but they do contain some surprises you might not want to know about in advance.

Headquarters

The rough cut of the film, adhering closely to Wai Ka-fai’s script, displayed a complicated flashback structure. The plot began fairly far into the action and then jumped back to establish the exposition. Central to that exposition is the film’s premise: Detective Bun, played by Lau Ching-wan, solves cases by extraordinary telepathic/ intuitive/ visionary insights. But the original cut blurred that concept, mixing it with an early revelation of the identity of the villain, a corrupt cop named Ko Chi-wai, and background on Bun’s young partner Ho. How to cut through the clutter?

The first step to a solution was to straighten out the chronology and to focus tightly on Bun from the start. The audience needed to understand the film’s eccentric psychological premise—specifically, that Bun’s gift allows him to detect multiple personalities buried within another person.

In talking with me, Tina went over three scenes that establish Bun’s peculiar abilities. (1) The sequences furnish striking examples of how filmmakers find precise technical solutions to storytelling problems. This trio of scenes also follow Hollywood’s Rule of Three. According to this, a key piece of information should be presented three times, preferably in different ways. (2) (Once for the smart people, once for the average people, and once for slow Joe in the back row.) Tina smiled. “This is not something that French directors would say.” The Rule of Three can be seen as another aid to solving the broad problem of clarity—making sure that the audience understands the story.

Discussing all three scenes adequately would take a lot of space and require dozens of stills, so I’ll concentrate on the first two. These should suffice to show how the filmmakers solved a tricky narrational problem.

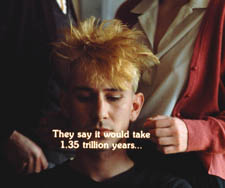

The first scene takes place in police headquarters and it’s the simplest. It starts with Bun absorbing details of Ho’s investigation. We hear, offscreen, a whining woman complaining that a maniac can’t solve a case. We think at first that it’s the voice of another cop, but after a second complaint from offscreen, Bun looks up. Cut to the whining woman, who stands among the cops.

Bun rises and walks to a pudgy cop who grins ingratiatingly. Now cut from the cop to the whining woman, in a similar composition against the same background.

An over-the-shoulder shot presents Bun staring as we hear the fat cop asking, “Do you recognize me?”

After the fat cop flatters him, Bun head-butts him. Bending over the fallen cop, Bun says, “Shut up. I see and hear you, bitch!” Cut from the bloody-nosed cop to Bun to the bloody-nosed woman.

After Ho dismisses the team, Bun slowly approaches and confides: “I can see the inner personalities of a person” (below). This line of dialogue crystallizes what we’ve seen–the bitchy woman inside the ingratiating man–and prepares for the next few scenes.

On the street

The second vision scene is more complicated, and Tina had several discussions with To and Wai about whether to include it. The new problem, based on the key line above, is to establish that Bun can see not one but several hidden personalities in Ko, the crooked cop. How can this premise be shown?

The major scene coming up shows the two partners confronting Ko at a restaurant. There Bun will envision some of Ko’s inner people manifesting themselves. But there’s also dramatic conflict to be conveyed in the scene, which culminates in a beating in the men’s room. Again, too much information! Tina, To, and their colleagues decided to include an intermediate scene, one that had little dramatic consequence but got audiences more comfortable with the premise.

Ho and Bun trail the suspect along the street, first in a car and then on foot. The results have the kind of precision I’ve pointed to in another Milkyway film, PTU.

In the car, Tina’s cutting establishes the differences between the two cops’ points of view. A two-shot of Ho and Bun yields to a straightforward POV shot of Ko striding along the sidewalk.

But a cut to Bun watching is followed by a shot of seven people in Ko’s place. In a nice instant of uncertainty, a few heads emerge from behind a parked van and are only partially visible. At first glance we might take them for passersby walking ahead of Ko.

Before we can fully identify this band of spirits, and as the car draws abreast, a cut to Ho watching leads to a shot of Ko, whistling.

Another cut to Bun, and now we see, as he apparently does, a full view of the platoon of Ko-personalities striding along whistling.

This mildly wacko variant is consistent with the narration’s mixed attitude toward Bun’s visions: are they supernatural insights or hallucinations?

Bun leaps from the car and pursues Ko’s band of personalities, and a new variation shows him and them in the same frame. But this is re-framed by Ho’s POV, which reasserts that to anyone but Bun, Ko is all by himself.

Abruptly, the visions halt and turn, staring at Bun. By now we are trained to understand what’s happening without a corresponding objective shot of Ko. Ko, we infer, has turned around to check on who’s following him.

Likewise, we can grasp the image of Bun passing through the group of figures as simply Bun walking past Ko.

At this point, we have no need to see the objective action. To and Tina have stressed the absence of an objective view by showing Ho, in the background, looking in another direction and missing this byplay (above). After Bun has passed, the troupe of avatars walks in their new direction, and then we get the objective shot of them “as” Ko.

This effect is anchored when Ho turns and notices Ko going into the restaurant.

As a meticulous touch, Ko’s departure from the frame reveals Bun still walking away in the distance. The geography is simple and impeccable.

The idea of seeing “inner personalities” has been made concrete while undergoing a lot of variation. Sometimes shots of the spirits are sandwiched between shots of Bun looking; sometimes not. Sometimes we have Ho to verify what’s really happening, but sometimes not. And sometimes Bun can be in the same frame as the avatars. Otherwise, Tina points out, the scenes would become boring.

Once the street scene has laid out how Bun sees Ko Chi-wai, the next scene, unfolding in the restaurant and a men’s toilet, can play with the premise still more. Tina explains that the creative team constantly asked, “How far can we go with Bun’s point of view, his vision?” Quite far, it turns out. The premise gets varied further across the whole movie, in imaginative ways. Which is to say that a solution to a problem can pose new problems, which the filmmakers go on to grapple with.

In our discussion, Tina noted that the street scene goes beyond simply giving us information. There’s a disquieting emotional effect when the spirits turn and confront Bun, their expressions ominously blank. Finding a solution to a creative problem often yields an unexpected payoff like this.

Bonus features

As I indicated, I can’t pursue the felicities of the restaurant scene here. Instead, here are some quick final thoughts.

*Mad Detective shows once more the power of basic techniques of performance (e.g., the act of looking), framing, and editing. To and Wai have no need for fancy CGI effects to evoke the “inner personalities” of Ko or the other cop. Our minds make the necessary connections. Lev Kuleshov would have admired the engineering economy of this sequence.

*In passing Tina and I talked about actors’ eyes, a special interest of mine. (3) Tina had noticed that actors try not to blink. She agreed that blinks pose problems for editors: “Blinking is very hard on cutting.” She remarked that Elia Suleiman would strain to keep from blinking until tears flowed from his eyes.

*Mad Detective was signed by both Johnnie To and Wai Ka-fai, but their joint projects are usually filmed by To, with Wai supplying the script and consulting as production proceeds. Tina confirms To’s habit of shooting with the whole scene’s layout in his head, using very few takes per shot and not a lot of coverage. The film is “very pre-cut,” she says. You can see this, I think, in the way To relies on matches on action and ends one shot with something that prepares you for the next one.

*To follows Hong Kong tradition of adding all the sound in postproduction. This makes for economy and efficiency in shooting, but it also gives HK films the fluency of silent cinema. The filmmaker gains a freedom of camera placement and is encouraged to think about how to tell the story visually. Tina and Shan Ding, To’s all-around assistant, pointed out that sync sound might make the director depend more on dialogue and static conversation scenes. Still, I think that sometimes they wish for a scene shot with direct sound.

*As with many Milkyway films, several scenes were filmed at the company headquarters. An earlier blog here discussed the ambitious rooftop set for Exiled. For Mad Detective, the fistfight in the restaurant toilet was filmed in the main men’s room of the Milkyway building, with a fake urinal added. Shan Ding provides documentation in the snapshot below, using a double for Lam Suet.

To come: Another Milkyway interview, this one with ace sound designer Martin Chappell. And a final batch of impressions from the Hong Kong International Film Festival, which ends on Sunday.

(1) If you know Mad Detective, you’re aware that Bun’s ability to discern hidden personalities is displayed in an earlier scene. But given the way in which that story action is presented, we can’t say that that his powers are established there. This scene is one of many clever narrational stratagems in a film that benefits from being rewatched.

(2) See Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), 31.

(3) Laugh if you must, but I wrote an essay about this. “Who Blinked First?” is available in Poetics of Cinema.

Pausing and chortling: A tribute to Bob Clampett

The Great Piggy Bank Robbery

Kristin here–

During my first year as a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the great animator Bob Clampett paid a visit to our campus. I actually got to sit next to him at lunch, and he was a charming, amusing man. Unfortunately I didn’t really know at the time what a genius he was, and, to my eternal regret, I neglected to ask for his autograph.

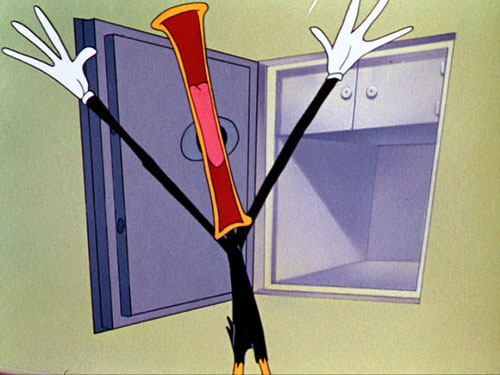

Today Clampett is less well-known to the general public than is Chuck Jones or Tex Avery. Jones and the other main creators of the classic Warner Bros.’s cartoons reportedly resented Clampett’s attempts to promote his own reputation by claiming sole credit for major achievements, such as “inventing” Bugs Bunny. When Jones put together The Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Movie (1979), there were no Clampett-supervised cartoons included. Clampett never wrote his memoirs. Jones did and left Clampett out. (Below, Draftee Daffy, 1945.)

These three major directors had their own distinctive approaches. Jones was on the whole more cerebral and often opted for beautiful visuals, perhaps most obviously evident in What’s Opera, Doc. Avery had a penchant for bad puns, often assembling whole cartoons based entirely around them. Clampett went for craziness and often for break-neck speed. The Wikipedia entry on him has this to say: “his characters are easily the most rubbery and wacky of all the Warner directors’.” (Above, Baby Bottleneck [1946].)

That wackiness was built into the name of one of Warner’s two animated series, “Looney Tunes.” Daffy Duck’s name characterizes him, but modern audiences may not be aware that “Bugs” also was a slang term for “crazy.” Along with Porky Pig, those were the two characters that Clampett used most often.

I’m not going to sum up Clampett’s career here. There is already quite a bit of excellent material on him available on the internet. For an overview of his career and style, see Adrian Danks’s “It Can Happen Here! The World of Bob Clampett” on Senses of Cinema; Michael Barrier’s epic 1970 interview with Clampett, with comments and corrections, is available on his website. That website contains many other shorter pieces on Clampett. Danks and the Wikipedia entry both give enough bibliographical sources to direct enthusiasts to additional information.

My purpose here is more modest. I simply want to point out how to find even more hilarity in Clampett’s cartoons beyond simply watching them.

As I’ve mentioned, David and I are in the process of revising our second textbook, Film History: An Introduction. The other day I was working on the section that deals with Hollywood animation in the 1930 to 1945 period. We’re adding more color to the book for its third edition, so I decided that Draftee Daffy, which we describe briefly, should have its own color plate.

As I watched the film on DVD, I paused on a number of possible frames to use, and I found myself laughing out loud at almost every one—something that doesn’t often happen during the revision of a textbook. Some of the character movements in Clampett’s films are so fast and brief that they come across as a flurry of images too fleeting to register. Frozen, they reveal some of the extraordinary means that the director and his animators used to achieve those effects of speed. Clampett was also adept at highly exaggerated reactions and hilarious distortions of the animal body. Watching these cartoons with a finger on the pause button can yield hilarity and teach you a lot about normally hidden aspects of the art of animation.

David has written about the artistry in Walt Disney’s films. He points out that a quick movement may be accomplished by adding extra limbs, as when in Melody Time Johnny Appleseed gathers an armload of falling apples and multiple arms and hands convey the speed of his gestures—as do a pair of phantom heads in the uppermost frame of the three David reproduces.

Such multiple images work without our noticing them. It’s not an obvious sort of technique to use. As David wrote, “Through trial and error Disney’s animators learned that rather strange single images will look exactly right on the screen; these men were practical perceptual psychologists.”

The same was true in the Warners animation department. In The Big Snooze (1946), Clampett’s last cartoon for the studio, he includes a scene of Bugs rapidly tying Elmer to some railroad tracks. In a couple of frames, he sprouts extra arms and hands. In The Great Piggy Bank Robbery (1946), phantom images of Daffy accompany his firing a machine gun.

But Clampett’s single images were often far stranger than the ones in the Melody Time example. In this one from Draftee Daffy, for example, the extra figures of Daffy as he frantically builds a wall between himself and his nemesis (the little man from the draft board) are purple.

I suppose that’s because multiple black figures of Daffy would blend together, but it’s still a bit weird. As an animator, how do you decide on a color?

Maybe it’s because purple is a subdued color that won’t call attention to the extra ducks and yet will contrast well with the black. It’s also the same color as the floor, so that might create an extra reason why we won’t notice them as standing out from the overall composition as it flashes past. If you know those purple ducks are there, you can just barely see them during normal projection. If you don’t know that, then you’re likely to miss them.

(I used that example of Daffy building the wall in my sole academic publication on animation, “Implications of the Cel Animation Technique,” in Teresa de Lauretis and Stephen Heath, eds., The Cinematic Apparatus [St. Martin’s Press, 1980]. There it had to be in black and white, unfortunately.)

Clampett often draws upon a standard animation device, “stretch,” to convey a sense of speed–although his characters may cross a room in as little as two or three frames. The first image of the telephone scene from The Great Piggy Bank Robbery is a fairly straightforward example of stretch, yet in the same scene, Daffy rapidly turning around uses the opposite technique, “squash.”

A similar technique which Clampett uses occasionally for a character about to launch into a rapid movement is a sort of squash with a perspective effect stretching the character toward the viewer, as in The Big Snooze when Bugs instructs Elmer to “Run this way.” (Bugs isn’t the only one who gets into drag in these cartoons.)

I’ve picked some of my favorite Clampett films, but many frames worth pausing on are to be found in others. With the Looney Tunes boxed sets still coming out, in five volumes to date, one can hunt out the Clampett films–though annoyingly, the indexes list neither the date nor the supervising animator, and there seems to be little logic involved in which films go on which discs. (There are also occasional jumps where something has presumably been censored.) It’s best to get thoroughly familiar with these films by simply viewing them. Then, pick up that remote and begin your search. You’ll discover that Clampett was one of the most imaginative of those “practical perceptual psychologists.”

The Great Piggy Bank Robbery.

Hands (and faces) across the table

DB here:

In books and blogs, I’ve expressed the wish that today’s American filmmakers would widen their range of creative choices. From the 1910s to the 1960s (and sometimes beyond), US filmmakers cultivated a range of expressive options—not only cutting and camera movement but other possibilities too. Studio directors were particularly adept at ensemble staging, shifting the actors around the set as the scene develops.

You can still find this technique in movies from Europe and Asia, as I try to show in Figures Traced in Light and elsewhere on this site. But it’s rare to find an American ready to keep the camera still and steady and to let the actors sculpt the action in continuous time, saving the cuts to underscore a pivot or heightening of the drama. Now nearly every American filmmaker is inclined to frame close, cut fast, and track that camera endlessly. I’ve called this stylistic paradigm intensified continuity.

As Los Angeles agent and former editor Larry Mirisch once put it in conversation with me: “They used to move their actors; now they move the camera.” Most of today’s prominent directors prefer kinetic camerawork and machine-gun cutting. This tends to make their staging rather simple and static: we get stand-and-deliver or walk-and-talk (subject of a blog entry here).

The result is a split in contemporary American style. Action scenes are often gracefully and forcefully choreographed (though sometimes the editing fuzzes up character position and overall geography). By contrast, conversation scenes, which could be choreographed as well, are handled either as a Steadicam walk-and-talk or simply as seated actors talking to one another, with cuts breaking up the lines and the camera on the prowl. (I discuss some examples in The Way Hollywood Tells It, pp. 128-173.) (1) You sometimes suspect that today’s directors are most at home shooting lots of people hunched over workstations, making the principal form of suspense a LOADING command.

Don’t get me wrong. Like all styles, intensified continuity isn’t a bankrupt option; many fine directors, from the Coens to Michael Mann, have worked vigorous variants on it. What I’m arguing for is more plurality, more tones in the director’s palette. I’ve revived these cranky ideas in discussing a single shot, this time in Variety. Today’s blog entry expands on that brief piece, so you may want to hop over to it here before reading what follows.

Directing us

One task facing any director is to direct—not only actors but us. The filmmaker must direct our attention to what’s important for responding to the drama at any moment. Since the late 1910s, we’ve known that close-ups and frequent cutting do just that. Tight framings and rapid cuts can steer the audience’s attention through a scene. So the question becomes: How can you direct attention without using close views and fast cutting?

Well, for one thing you can place the main action in the center of the picture format. If there are several points of interest in the shot, which is usually the case, you can arrange them symmetrically around the central zone of the shot—in film, usually an zone just above the geometrical center of the picture format. You can also position your main players so that the most important ones are closer and/or facing toward the camera. By turning a character away from the camera, you can drive the audience’s eye to someone else. There are other pictorial cues worth mentioning (lighting, color combinations, patterns in the set design), but these will hold us for now. Add in movement—characters shifting their position, especially coming closer to the camera—and you have a suite of cues that a film shot can provide.

Apart from these purely compositional factors, you the director can exploit some cues that are part of our social proclivities. When we watch other people, we’re attracted to areas of high information—which, for creatures like us, are faces and hands. Faces send signals about what people are thinking and feeling, with the areas around the eyes and mouth telling us most. Hands are the source of gestures, as well as potential threats. And of course if someone is speaking and others are listening, we are likely, all other things being equal, to look at the speaker.

The crucial fact is that in ensemble staging all these cues, and more, are at work at the same time. The director’s skill is orchestrating them so that they support one another, guiding us to see this or that. (On rare occasions, the director will use them to misguide us, but let’s stick with the default for the moment.) For a long time, filmmakers knew intuitively how to coordinate these cues to create rich and intricate shots; I fear that they no longer know how. (2)

That’s what makes one passage in Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood of interest to me. The scene presents Paul Sunday explaining to Daniel Plainview that there’s oil on his family’s property. Daniel and Paul are bent over a map on a tabletop, with Daniel’s assistant Fletcher Hamilton and Daniel’s son HW watching. The scene is presented in a single shot, with a slight camera movement forward at the start.

The composition could hardly be simpler: four people lined up, three at the edge of the table. The heads cluster around the center of the format, with HW lower and off-center; no surprise that he’s the least important character in the scene (though his question to Paul foreshadows action in the film to come). Paul is explaining where the oil is, and the two men’s faces and hands command our attention as they speak.

Many directors would have cut in to a close-up of the map, showing us the details of the layout, but that isn’t important for what Anderson is interested in. The actual geography of Plainview’s territorial imperative isn’t explored much in the movie, which is more centrally about physical effort and commercial stratagems.

Questioning Paul about his family, Daniel turns slightly away. This clears a moment for HW to ask about the girls in Paul’s family, and for a moment our attention is steered to the right, to pick up their interchange.

Then Fletcher asks about the farm, and as Paul and Daniel tilt their faces to him, he earns his place in the center of the frame. Before, when we could see the faces of the two men closest to the camera, he was subsidiary, but now he becomes salient. On the left, Daniel shifts away uneasily, turning almost completely away from the camera. In answering Fletcher, Paul turns away in the opposite direction, as if shy or guilty; his awkward gesture of stroking his hat seems to confirm Daniel’s doubts about him.

During a pause, Paul turns back to stare directly at Daniel, saying quietly, “The oil is there.” At the same time, Daniel, still turned away, is exchanging a glance with Fletcher. At this point, Anderson’s training of us pays off: we’re ready to detect the slight shift in Fletcher’s eyes, which confirms that Daniel’s looking at him. “Watch their eyes,” as John Ford liked to say.

Paul sets out to leave, and he refuses the invitation to stay the night. At this point comes the scene’s biggest gesture. Daniel raises his hand, in the dead center of the frame.

Spreading his long, thin fingers, Daniel commands our attention. He seems at once to be halting the young man and threatening him. But the gesture becomes the prelude to a handshake. Daniel’s characteristic blend of bluff assurance, friendliness, and aggressiveness are packed into this single gesture. (At the climax, other gestures will recall this one.)

Daniel steps closer to Paul, blocking out Fletcher, to make his threat: If he travels so far and doesn’t find oil, he’ll find Paul and “take more than my money back.” Paul agrees and moves away. “Nice luck to you, and God bless.”

The men watch Paul leave the building. End of scene.

Without any close-ups or cutting, Anderson has skillfully steered us to the main points of the scene, which are carried by the performers. The drama builds through small changes of position, shifts of weight, and facial expressions that accompany the dialogue. (The somber, plaintive music adds an uneasy edge.) Daniel seems more threatening when we don’t see his reaction, and Anderson’s camera forces us to scrutinize Paul’s expressions and body language for signs that this is a scam. It takes confidence to make a raised hand the climax of a scene, but the gesture gains its force by being the most aggressive moment in an arc of quietly accumulating tension.

All the principles involved here—frontality, spacing of figures, slight shifts of compositional focus, actors’ body language—are simple in themselves, but they gain a strong impact by cooperating with one another. The scene’s quiet obliqueness is characteristic of the film, which, at least until the last few minutes, carries us along with hints about where the action might go and what drives its characters.

Yet simplicity shouldn’t imply simplification. Anderson’s willingness to give the shot several points of interest, some more stressed than others, creates an understated tension. The shot’s gravity stems from its conciseness, a quality that Anderson admires in 1940s studio films like The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.

Two more tabletops

The staging strategies Anderson uses aren’t new, as I’ve suggested. They’re part of the history of film as an art form, and many directors have continually relied on them. I don’t think that this is always a matter of influence, although surely filmmakers learned from watching earlier films. Often, directors working within similar constraints intuitively rediscover what other directors have already done.

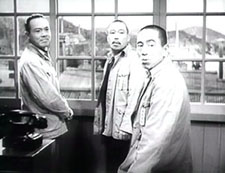

Consider this scene from Kurosawa Akira’s The Most Beautiful (1944). The setting is a plant where Japanese workers, mostly girls and women, are manufacturing bombsights. The workers have vowed to increase production for the war effort, and they are working to the point of exhaustion. The plant supervisors are worried that the pace will take its toll on the girls.

The scene starts with the eldest supervisor studying the output chart, lying on a table below the frame edge. His colleagues are turned away, at the window. He is the one who must decide how to keep the girls healthy and the output steady. The table and the window will be the two poles of the action, and the actors will oscillate between them. The process starts when the eldest retreats to the window, and one comes forward to study the report.

He’s followed by his opposite number, and they echo one other in rubbing their necks. They’re as tired as the assembly-line girls. Their superior turns and says that there’s no point in lowering the quota because the girls are so devoted that they’d push harder anyway.

The men have turned to listen to him, driving our attention to his centered, frontal figure. After the elder has turned away again, the man on the right says that this might be the critical juncture. Remarkably, all three men remain turned from us, creating a slight pictorial tension.

This tension is extended when the supervisor on the left states his confidence in the children, their team leader, and their teacher. This makes the eldest turn around.

The speaker walks to the window, arguing that the girls will succeed, but the leader turns away again dubiously. He doesn’t offer a decision because an offscreen voice announces that a teacher has come to see them, and they all turn to look.

The factory’s problem isn’t solved; the seesawing of the staging has presented that irresolution dynamically. In a single shot, the difficulty of the administrative decision has been expressed in counterweighted movements in and out, by the figures’ frontality and dorsality. Again, it can seem simple, but where a contemporary American director would have given us a prolonged passage of stand and deliver, with intercut close-ups, Kurosawa has created a little ballet out of the men’s uncertainties. Like Daniel’s raised hand, but with even less emphasis, the assistant’s plea on behalf of the girls’ commitment has gained a subtle prominence. Yet all he has done is walk to the window.

I’m not saying, of course, that Anderson took the idea from Kurosawa. Given the initial choice to stage the scene behind a table, and the inclination to present the action in one shot, both directors spontaneously drew on basic staging principles. This is what film directors have always done. So as a finisher, here’s one last tabletop interlude from Cecil B. DeMille’s Kindling (1915). The entire scene is a dense and intricate affair, but let’s pick just one moment. Maggie has become a servant to a rich woman, Mrs. Burke-Smith, and she’s about to be arrested for theft. Detective Rafferty is ready to handcuff her, but Mrs. Burke-Smith changes her mind.

DeMille arranges his actors so that we can’t miss the rich woman’s moment of decision. She is in the foreground, and her face is in the upper center of the frame. The other actors are blocked, so that her expression is the only one we can see clearly at the crucial moment. Her hand gesture, stretching across the central axis of the frame, confirms that she won’t charge Maggie. (For a similar use of “blossoming” actors’ movements in 1910s cinema, go here and look at Figs. 2A10-2A11.) What DeMille knew, Kurosawa discovered afresh, and Anderson hit upon it again.

Strategies of staging, like other principles shaping how films tell stories, lie behind each concrete creative decision the film artist makes. They run as undercurrents through film history, almost never discussed by critics. They form a body of tacit knowledge, flowing across our usual distinctions of period, genre, director, national cinema. We can trace continuities and changes, examining how the strategies are revived, revised, or rejected. They can provide us with subtle but powerful experiences. They constitute a skill set that is available to filmmakers today. . . if any will, like Anderson, seize the chance.

(1) True, Wes Anderson keeps the camera still, but in his frontal, family-portrait framings the cutting and line readings do all the work; dynamic staging isn’t on his menu.

(2) I survey the development of these and other tactics in Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style. On this site, for one example go here and scroll down to the Bauer material.

What happens between shots happens between your ears

DB here:

In Number, Please? (1920) Harold Lloyd plays a lovesick boy who’s been jilted by his girl. Moping at an amusement park, he sees her arrive with a new beau.

He shifts to another spot to watch them. When she notices him, she scorns him, and he reacts.

She and the escort stroll past, then she turns and cuddles up to him, making sure Harold notices.

Her flirting precipitates the rest of the action in this very funny short.

In this scene from Number, Please? Harold and the couple aren’t shown in the same frame. The action is built entirely out of singles of Harold and two-shots of the couple, with an especially emphasized close-up of the girl’s snooty reaction. The sequence is rapidly paced and carefully matched in angle; note the shift in eyelines as the girl and her beau walk a little way and then she looks back at Harold.

This approach to building a scene was consolidated in American studio cinema in the late 1910s, as we noted recently, and it soon spread around the world. One of the places it caught on most fervently was Soviet Russia.

Kuleshov glories in the gaps

The great director and theorist Lev Kuleshov always claimed that he and his associates learned the power of editing from American cinema. Russian films were slowly paced, consisting of long tableaus occasionally broken by an inserted closer view of an actor. (For examples, see my Bauer blog entry from the summer.) Kuleshov noted that the Hollywood films brought into Russia grabbed audiences’ interest more intently, and Kuleshov attributed this effect to the fact that the Americans exploited editing more fully, creating the scene out of many shots.

Kuleshov’s example was the formulaic scene of a man sitting at his desk and deciding to commit suicide. The Russians, Kuleshov claimed, would handle this all in one distant framing, with the result that the key actions were just part of the overall view. By contrast, Americans would shoot the scene in a series of close-ups: the man’s face, his hand taking a pistol out of a desk drawer, his finger tightening on the trigger, and so on. This gave the scene a powerful concreteness, and was cheaper to film besides (no need to have a full set).

But most American filmmakers didn’t create the scene wholly out of close-ups. Typically there would be an establishing shot before the action was broken down into detail shots. The process has come to be called analytical editing. (We discuss it in Chapter 6 of Film Art.) As the label implies, the cutting analyzes an orienting view into its important details.

Less commonly, as in our Number, Please? example, American directors could create a scene entirely out of separate areas of space, without ever showing a master framing. This technique, usually called constructive editing, remains common today as well, especially in action scenes.

While praising analytical editing, Kuleshov was particularly taken with constructive editing, because that shows that cinema can call on the spectator’s tacit understanding to assemble the separate shots. Kuleshov realized that we will build a sense of the scene’s space and action out of separate shots without need for the comprehensive view supplied by an establishing shot.

What the Americans developed, the Soviets thought seriously about. Around 1921, Kuleshov and his students mounted some experiments, several of which he discusses in his books and essays. He probably didn’t need to experiment; the American films were full of examples. Indeed, the Number Please? passage is more intricate than any experiment Kuleshov seems to have mounted. But he had a bit of the engineer about him, and he sought to break the technique into its simplest components.

For one thing, constructive editing offered production efficiencies. You could film two actors separately, at different times, and then cut them together. Further, Kuleshov saw that editing could abolish real-world constraints. It created events that existed only on the screen, with an assist from the viewer’s mind.

This is perhaps best seen in his experiment involving an “artificial person.” Evidently it wasn’t a case of constructive editing, because it seems to have begun with an establishing shot. The first shot shows a girl sitting at her vanity table putting on makeup and slippers. A series of close-ups of lips, hands, legs, and the like were derived from different women, and they were edited together to create the impression of a single woman. (Something of this effect survives in the idea of a body double in contemporary films and TV commercials.) But the point is that the woman on screen, made out of different parts, doesn’t exist in the real world.

The same possibility could apply to geography, if we delete the establishing shot. As Kuleshov describes his experiment, we initially get a shot of a woman walking along a Moscow street. She stops and waves, looking offscreen. Cut to a man on a street that is in actuality two miles away. He smiles at her and they meet in yet a third location, shaking hands. Then together they look offscreen; cut to the Capitol in Washington DC. Kuleshov saw the potential for imaginary geography as both a useful production procedure and a demonstration that editing could create a purely cinematic space, one not beholden to reality.

Kuleshov’s most famous experiment, the one he identified with the “Kuleshov effect” proper, involves a stock shot of the actor Ivan Mosjoukin, taken from an existing film. In his writing he’s rather vague and laconic about the results.

I alternated the same shot of Mosjoukin with various other shots (a plate of soup, a girl, a child’s coffin), and these shots acquired a different meaning. The discovery stunned me—so convinced was I of the enormous power of montage. (1)

Kuleshov’s pupil the great director V. I. Pudovkin offers a different description of the shots: a plate of soup, a dead woman in a coffin, a little girl playing with a teddy bear. He also goes farther in reporting how the audience responded. People read emotions into the neutral expression on Mosjoukin’s face.

The audience raved about the actor’s refined acting. They pointed out his weighted pensiveness over the forgotten soup. They were touched by the profound sorrow in his eyes as he looked upon the dead woman, and admired the light, happy smile with which he feasted his eyes upon the girl at play. But we knew that in all three cases the face was exactly the same. (2)

Now it isn’t only geography or a human body that has been created by editing; it’s an emotion.

These experiments have been poorly documented, and only a couple have survived. One consists of fragments of the imaginary geography exercise. Here is Alexandra Khokhlova waving, but we don’t have the answering shot of the male actor responding. The two meet at the foot of a statue.

After the two shake hands, they look up and out of the frame, but unfortunately we lack the shot of the Capitol.

Kristin and other scholars have written more about these surviving fragments, and their essays are published along with Kuleshov’s proposal for funding the experiments and his wife Khokhlova’s memoir of filming them. (3)

It’s worth taking these prototypes of constructive editing apart a little bit. Clearly, there are several cues that prompt us to see the shots as continuous.

One cue is a common background, or at least a consistent one. Kuleshov thought that sometimes a neutral black background worked best, especially for close shots, as you can see with the handshake shot. Another cue is roughly consistent lighting from shot to shot. Yet another is the presumption of temporal continuity; no moments seem to be omitted in the cut from shot A to shot B. It never occurs to us to consider that Kuleshov’s man is looking at something hours or days before the soup is laid on the table in the second shot.

One of the most important cues goes unmentioned by Kuleshov: the very act of looking. Like most commentators, he seems to take it for granted. Yet it’s crucial in prompting us to imagine an overall space in which the actions take place. Knowing the real world as we do, we can infer that if you’re close enough to watch someone, both people are probably in a shared space, such as the arcade strip in the amusement park in Number, Please?

Another cue is facial expression. In his soup/girl/coffin sequence, Kuleshov supposedly picked a shot of Mosjoukin that doesn’t have a clearly identifiable expression. If Mosjoukin was smiling in his interpolated shot, he would presumably seem not grieving but wicked. Normally, though, performers seen in the single shot are expected to express the appropriate emotion more fully, in order to specify what we take the characters’ mental states to be. Our sequence from Number, Please? makes sure we understand the drama by giving the actors unambiguous expressions.

Finally, in the Kuleshov prototypes each shot should be simple. Its action can be stated in a brief sentence. A woman waves. A man responds. A man looks. A plate of soup sits on a table. Even in Number, Please? we can summarize each shot: Harold looks off. His former girlfriend disdains him. That’s to say that the shots are composed to present only one, quickly grasped point of interest.

Filmmakers don’t need to tease apart all these cues; they use them intuitively. Soon after Number, Please?, Hollywood filmmakers were creating amazing passages of eyeline-match editing—the most virtuoso being probably the racetrack sequence in Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan (1926). Within a few years of Kuleshov’s experiments, Soviet filmmakers were creating their own masterworks, like Battleship Potemkin (1925) and Kuleshov’s By the Law (1926). Benefiting from a very compressed learning curve, filmmakers took constructive editing to new heights.

Constructive editing, dissolved relationships

Sometimes constructive editing is used to save a scene when production goes astray. When Doug Liman reshot the climax of The Bourne Identity, Julia Stiles couldn’t be on set, so singles of her taken from the first version were wedged in among the retakes, to create the impression that she was watching Jason confront his controller. More positively, a carefully calibrated constructive editing is central to a sequence I analyzed a while back in In the City of Sylvia. For over 100 shots, the spatial relations are built up without an overall establishing shot. (4)

Constructive editing can be used systematically throughout a film. A good example is Alan J. Pakula’s thriller Presumed Innocent (1990). Spoilers coming up!

Harrison Ford plays Rusty Sabitch, a prosecutor in the District Attorney’s office who becomes infatuated with a new woman on the staff. He has a brief affair with her, but after she’s broken it off she’s found brutally murdered. He has to investigate the crime without involving himself, but eventually he becomes the prime suspect.

At the start of the film before Rusty learns of the murder, Rusty and his wife Barbara are shown at breakfast, and establishing shots bring them together.

At the office Rusty learns of Carolyn’s death, and after he comes home, the conversation between Rusty and Barbara is treated without an establishing shot. Barbara knows about the past affair, and Rusty is wracked by guilt and shame. The cutting seems to reflect the fact that Carolyn’s death has revived the pain in their marriage.

In a series of flashbacks, Rusty relives his affair with Carolyn. Pakula treats their early encounters by means of constructive editing. The common-background cue is especially helpful in this scene in a kindergarten.

Only after Carolyn and Rusty cooperate and win a child-abuse case does the cutting’s rationale become clear. Pakula has saved the traditional two-shot framing for their moment of passion, as they make furious love in the office.

But soon their affair wanes and Rusty is reduced to watching Carolyn from across the street in point-of-view shots.

After the flashbacks end, Rusty is investigated and eventually charged with Carolyn’s murder. In these scenes Pakula often situates Rusty and Barbara in the same frame, as if the threat to him has healed the breach between them.

Yet in the film’s climax—and here is the big spoiler—they are pulled apart again. The last scene is a sustained monologue by Barbara. As Rusty listens, across twenty-six shots the two are never shown in an establishing shot.

Contrary to the standard Hollywood ending, in which the loving couple embrace in reunion, here they are left divided.

Pakula’s use of constructive editing has effectively traced two arcs: the growth and dissolution of Rusty’s affair, and the reuniting and dissolution of his marriage. In such ways, what might seem a purely local effect, confined to a handful of shots, can create stylistic patterning across a film. The judicious use of constructive editing matches the dramatic development.

Godard of the gaps

Robert Bresson has made more varied and complex uses of constructive editing across a film, as I tried to show in Narration in the Fiction Film and in an Artforum essay. (5) A more radical approach, somewhat in the purely Kuleshovian spirit, can be seen in Godard’s films since the late 1970s. In presenting a scene, Godard often omits an establishing shot, so constructive editing takes over. But he makes the technique quite abrasive and ambivalent.

In watching films like Number, Please? and Presumed Innocent, we fill in the gaps between shots with ease. Godard, however, makes his images and sounds more fragmentary by equivocating about the Kuleshovian cues. The background elements and lighting don’t match entirely; time seems to be skipped over; glances and facial expressions are ambivalent. Adding to these factors, lines of dialogue slip in from offscreen. Godard does present a dramatic scene taking place, but he also creates a sense that images and sounds have been pried loose from their place in an ongoing action, floating somewhat free and functioning as objects of contemplation for their own sake. The cues that Lloyd insists on and that Kuleshov plays with are ones that Godard suppresses or makes ambiguous.

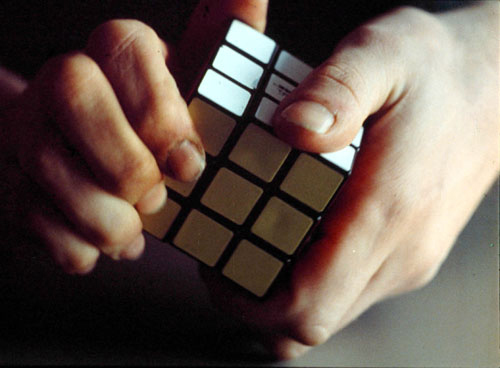

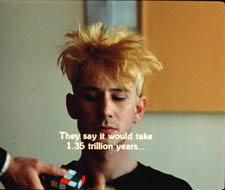

I’ve mentioned this tendency in a recent entry, but to elaborate a little, consider the science lecture in Hail Mary (Je vous salue Marie, 1985). A professor who has emigrated from an Eastern bloc country is explaining his theory that life on earth began and evolved because it was directed by extraterrestrials. No establishing shot of the classroom shows us where he, Eva, and two male students are located, so we have to construct a rough sense of their positions on the basis of a few cues. As Eva, perched on a windowsill, toys with a Rubik’s cube, we hear the professor’s lecture begin to speculate on whether life could have evolved spontaneously. His remarks about sunlight coincide with a burst of sun on her face.

After the Biblical title, “In those days,” we get a series of shots that allow us to apply our mental schema of a classroom lecture: attentive students looking off, a professor at the blackboard.

Lacking an establishing shot, we can’t specify how many people are in the class, nor indeed where Eva and her classmate are sitting—since the professor looks off in several directions during his talk.

At the end of his talk he remarks, still scanning the room, that we can presume that life exists in space. “We come from there.” At that point Godard cuts to the head of another student, seen from behind. The sproingy haircut is a little explosion of yellow, and it’s accompanied by a burst of choral music. And as the shot goes on, we start to notice that the professor is pacing in the background, out of focus.

The student, whom we’ll learn is named Pascal, asks a question (at least the slight head movement suggests that it comes from him), and the professor replies. Pascal scratches his head as the professor continues, still out of focus. If I had to choose one shot that condenses Godard’s strategy of suppression in this sequence, this shot would be my candidate.

At the end of the shot, the professor asks Eva to stand behind Pascal. Cut 180 degrees and somewhat farther back to Pascal, now seen from the front. The professor’s hand brings the Rubik’s cube into the shot and Eva comes up behind Pascal as the professor passes.

Later she and the prof will become lovers, but Godard lets them meet first as simply two torsos intersecting behind Pascal. The purpose is a demonstration that a “blind” agent can be steered toward a goal through simple yes/no commands. This models the professor’s theory that an alien intelligence could have guided evolution.

Pascal will twist the facets of the cube under Eva’s hints. Godard makes this a tactile, even erotic exchange, with the close-up of her by his ear and Eva saying, “Yes,” more urgently as Pascal’s hands arrive at a solution, in the close-up surmounting this blog entry.

The next two shots of the sequence center on the prof, who has exited frame right from the “three-shot.” Now he’s at the window, recalling the initial shot of Eva; but unlike her he’s little more than a silhouette. As crashing organ music is heard, he seems to be watching the experiment from afar. The second shot, an axial cut-in, coincides with the offscreen voice of a male student: “Were you exiled for these ideas?”

“These ideas, and others,” the prof replies. He says he’ll see the class on Monday, evoking the idea that he’s dismissing the offscreen students, and he turns his head slightly, though we can’t be sure they’re on his right. This shot will be held for some time as students quiz him more about his theory, and Eva asks him if he’d like to come over for a drink some evening. But we don’t see her say it. Godard cuts to a shot of Eva at the window, bathed in sunlight, opening and shutting her eyes as she slightly lifts and lowers her head.

As we see her, we hear the rustling of people leaving (so the class was evidently larger than three). And we hear him reply to her invitation, “That’s another story [scénario].” Are Eva and the prof looking at each other? We’re inclined to say yes, but her closed eyes and tilting head suggests someone lost in contemplation rather than engaged in conversation. Here the classic facial-expression cue is made indeterminate. We have no way of knowing if the prof’s line comes from offscreen, or is displaced from another point in time; maybe he has left the room. Such displaced diegetic sound occurs elsewhere in the film.

We don’t have to decide; our indecision is the point. By pruning away the most reliable cues, Godard wins both ways. We’re kept somewhat oriented to an intelligible action: a prof sets forth his far-fetched theory of human origins and a woman in his class invites him for coffee. This side of the balance allows us to feel that a story, however sketchy, is moving forward.

But the moment-by-moment texture of the scene allows the individual shots, gestures, and sounds to drift somewhat free. Each image takes on a more intrinsic weight, and the juxtaposition of picture and sound acquires a resonance that we usually call poetic. A shot of Eva in the sun playing with the Rubik’s cube, unanchored in time (during class? before class started?), invites us to apply metaphors, especially once we learn her name. Pascal’s thorny hair suggests not only extraterrestrials but the explosion of a nova. The silhouetted prof, detached from the mechanism he has set in motion, hints at an unknown deity watching the game play out according to his rules. Why do Godard films spawn long essays built out of erudite associations? Because the narrative progression relaxes and we can weave our own connotations out of what we see and hear.

If you don’t want to go down the expanding-association route, there’s another one open. When individual moments no longer accumulate ordinary dramatic pressure, we can savor the fugitive pleasures of the separate shots (light on face, lips by ear) and the patterns they form: flipover cuts, yellow hair and yellow facets, bookended shots of Eva at the window.

Those patterns, it should be clear, depend on our sensing a bump at every shot change, looking for a way to skip across the gap that Godard creates. The same belief that meaning and effect are born of gaps impelled Kuleshov too, and perhaps even Lloyd. If we pay attention to those gaps we can feel minds—both the filmmaker’s and ours—at work in them.

(1) Lev Kuleshov, “’50’: In Maloi Gznezdinokovsky Lane,” Kuleshov on Film, trans. and ed, Ronald Levaco (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974), 200.

(2) V. I. Pudovkin, “The Naturschchik instead of the Actor,” Selected Essays, ed. and trans. Richard Taylor (Oxford: Seagull, 2006), 160.

(3) See Kristin Thompson, Yuri Tsivian, and Ekaterina Khokhlova, “The Rediscovery of a Kuleshov Experiment: A Dossier,” Film History 8, 3 (1996), 357-367.

(4) The sequence does begin with a long shot of the café, but it is so distant, crowded, and brief that it can’t really be said to establish the spatial relationships among the several characters we see.

(5) “Sounds of Silence,” Artforum International (April 2000): 123.