Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

All singing! All dancing! All teaching!

Kristin here—

David and I are currently revising our second textbook, Film History: An Introduction, for a third edition due out next year. As part of the research, I’ve been watching two recent DVDs on the early history of sound and color. Both offer valuable resources for those teaching introductory film-history classes, as well as more specialized ones.

Twenty-five years ago, when I last taught a survey history class, the resources for teaching about the innovation of sound were discouragingly limited. The early Vitaphone shorts were as yet unrestored, with most of their accompanying discs damaged or lost. The most famous early sound films were mainly available in mediocre 16mm prints. Showing an “early” sound film often meant a René Clair classic from the early 1930s—a time when the transition to sound was well along, if not over. Le Million or Á nous la liberté demonstrated the artistry that an imaginative director could bring to the early sound cinema, but it wouldn’t give much idea of the struggle inventors and filmmakers went through to create the complex technology.

The same was true for pre-1935 color. There was no way to adequately survey the range of processes and experiments, from early hand painting and stenciling to two-strip Technicolor. The poor 16mm prints of early films often gave no real indication of what they had looked and sounded like when they were made.

Since then archivists have been intensively discovering and preserving films, and in some cases these have been released on DVD. Often these discs are simply collections of films, but documentaries incorporating short films and clips are becoming more common, especially since they make attractive television programs.

Discovering Cinema (Flicker Alley)/Les Premiere pas du cinéma (Lobster & histoire)

A two-DVD survey from the very active Lobster archive in Paris devotes a disc each to sound (2003) and color (2004). Lobster is a private archive started in 1985 by two film enthusiasts, Serge Bromberg and Eric Lange. (The website offers a choice of French or English text.) It began as an effort to discover lost films. Building on its success, Lobster has grown into a major resources for restoring films—both their own discoveries and commissions from other archives and from film companies.

David and I bought this set when it came out. The French boxed set offers a choice of French- or English-language versions. (It’s not region-coded, but it is PAL, which means it won’t play on NTSC players, the standard in the U.S. and some other countries.) The French version isn’t on the Amazon.fr site, but fnac is offering it.

In September, 2007, the American version was released by Flicker Alley. This is another private archive, founded in 2002, also by an enthusiast, Jeffery Masino. The company hasn’t put out many titles yet, but the DVDs available so far are impressive. Flicker Alley collaborates with Turner on restorations, and presumably its catalogue will grow.

Each Lobster documentary is about 52 minutes long, and the supplements include a number of complete films.

The disc devoted to color is subtitled “Un rêve en couleur” and in English the slightly more poetic “Movies Dream in Color.” It’s organized by the three types of cinematic color: Colors and Tints (that is, black and white film painted or dyed), Additive Synthesis (using filters on the projector lens to add color to black-white film), and Subtractive Synthesis (recording separate colors on separate strips of film and combining them in printing).

The disc devoted to color is subtitled “Un rêve en couleur” and in English the slightly more poetic “Movies Dream in Color.” It’s organized by the three types of cinematic color: Colors and Tints (that is, black and white film painted or dyed), Additive Synthesis (using filters on the projector lens to add color to black-white film), and Subtractive Synthesis (recording separate colors on separate strips of film and combining them in printing).

There’s a quick run-through on color in pre-cinema devices: slides, peep shows, and topical toys. The next section gives a splendid demonstration of how stencils were used to hand-color films (such as the unidentified example above), as well as some briefer coverage of tinting and toning.

Moving to additive color systems, the film deals with Friese-Green’s early experiments, Charles Urban’s Kinemacolor, with its brief commercial success, Gaumont’s technically sophisticated Chronochrome, and various lenticular systems. Given that these attempts require special projection, the recreated examples given here are one of the few ways that we can see such films today. All of them proved dead ends, however, so they are of more interest for their technical ingenuity than for their ultimate impact.

The final part of the film turns to Technicolor, founded in 1915. The firm quickly turned away from its early additive experiments and settled on a subtractive system using two strips of film and later, in the 1930s, three strips—resulting in the vibrant hues that many people still think of as the acme of filmic color. “Movies Dream in Color” gives a brief but useful run-down of Technicolor’s progress, through its early two-strip successes like The Black Pirate through the exclusive contract with Disney in the 1932-36 period, and its triumph thereafter as the main color system of Hollywood. There is also some coverage of the two brands that combined all colors on a single negative, Kodachrome and Agfacolor, but the coverage essentially ends in 1939, before either had become widespread.

Incidentally, an in-depth study of Technicolor has recently been published: Scott Higgins’ Harnessing the Rainbow: Color Design in the 1930s.

The filmmakers weave together interviews with a number of prominent archivists, including Paolo Cherchi Usai (co-founder of “Le Giornate del Cinema Muto” festival and now director of Australia’s national archive) and Gian Luca Farinelli (director of the Cineteca di Bologna).

“Learning to Talk” (in the French set “Á la recherche du son”) uses the same group of experts and a somewhat similar three-part organization: “artistic sound” (that is, live sound during the projection of silent films), sound on disc, and sound on film.

The segment on live sound is excellent. It again starts with pre-cinema music and effects for magic-lantern shows and progresses to Reynaud’s hand-drawn Pantomimes lumineuses, with their specially written music. One highlight is documentary footage of a man demonstrating the use of an elaborate sound-effects box, with its brushes, cans of pebbles, and other crank-operated devices that simulated such actions as trains moving and crockery being smashed.

The sections devoted to sound-on-disc and sound-on-film are less well set forth, since the filmmakers try to cover many pioneers in France, the U.S., Germany, and Denmark. Again, several of the devices covered were novelties that led nowhere or that failed for lack of amplification, the use of non-standard film widths, and other reasons.

Once the story reaches the lengthy invention process of the two main American systems, Warner Bros.’ Vitaphone (using discs) and Fox’s Movietone (sound-on-film), it proceeds more clearly. “Learning to Talk” includes some of the Case and Sponable demo films, a Movietone News interview with Mussolini, and a clip from Don Juan. Presumably because of rights problems, no footage from The Jazz Singer is shown.

The bottom line is that the color disc strikes me as the more useful for teachers. The sound one gives good coverage, but again many of the systems discussed are not historically significant to anyone but specialists. For a history of that deals largely with the American innovation of sound, one can now turn to a superb recent DVD.

A Century of Sound: The History of Sound in Motion Pictures: The Beginning: 1876-1932 (UCLA Film & Television Archive and the Rick Chace Foundation).

This disc originated in a lecture on early sound by Robert Gitt, who has long been the preservation officer for UCLA’s film archive. Gitt has supervised on the restoration of many important films. In 1991 his team launched the Vitaphone Project. Vitaphone, Warner Bros.’s commercially successful sound system of the 1926-31 period, used phonograph records rather than optical tracks on the film strip. Over the decades many of those discs were damaged or separated from the original reels, and the Vitaphone shorts sat in their cans, reduced to silence.

Gitt and company set about finding as many discs for the surviving Vitaphone films as they could. Over the years they were amazingly successful in tracking them down and rejoining sound and image in a sound-on-film format that can be shown on modern projectors. You can trace the progress of the project since its beginning through its online newsletter, which currently runs from fall, 1991 to winter, 2007/08.

Colleagues urged Gitt to turn his lecture on sound, copiously illustrated with clips, into a DVD. He took the opportunity to expand the talk and to incorporate more and lengthier clips. Most documentaries on film history include only brief clips from any scene. Gitt has wisely opted to include whole scenes, and he has had access to high-quality archival prints of the key early sound films. He also offers early tests made by the companies responsible for innovating sound, as well as documentary shorts they used in selling their processes to industry executives. Rather than writing a script for someone else to read, Gitt appears as presenter and narrator. He humorously admits to the dullness of some of the technical shorts and acknowledges the occasionally silly or racist content of some of the films. At the same time, though, he makes clear what is significant about the examples he presents, and they all become more intriguing than they would if seen individually, out of context.

Colleagues urged Gitt to turn his lecture on sound, copiously illustrated with clips, into a DVD. He took the opportunity to expand the talk and to incorporate more and lengthier clips. Most documentaries on film history include only brief clips from any scene. Gitt has wisely opted to include whole scenes, and he has had access to high-quality archival prints of the key early sound films. He also offers early tests made by the companies responsible for innovating sound, as well as documentary shorts they used in selling their processes to industry executives. Rather than writing a script for someone else to read, Gitt appears as presenter and narrator. He humorously admits to the dullness of some of the technical shorts and acknowledges the occasionally silly or racist content of some of the films. At the same time, though, he makes clear what is significant about the examples he presents, and they all become more intriguing than they would if seen individually, out of context.

The result offers an extraordinary array of clips that teachers could draw upon even if they don’t have time to show the entire lengthy documentary. For Vitaphone there are some of the early shorts, the entire duel scene from Don Juan, extended excerpts from The Better ‘Ole, Old San Francisco, Lights of New York, and others. For Fox Movietone there are scenes from 7th Heaven and Sunrise, as well as George Bernard Shaw’s charming appearance in an issue of Movietone News.

Despite some lively moments, many of the early sound films are slow and clunky, due to the limitations of the available equipment. Gitt balances them by ending with some familiar examples of the imaginative early use of the new technique: the “Paris, Please Stay the Same” number from Lubitsch’s The Love Parade, a generous excerpt from Mamoulian’s Applause, and a portion of I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (which, be warned, gives away the ending). Teachers whose schedules don’t permit them to devote precious screening time to an early sound feature can give their students a reasonably good sense of the transitional period with such clips.

We’ve all heard the stories about how certain actors’ careers were destroyed by sound, but for the teacher there’s again the problem of how to demonstrate this to classes. Gitt has filled this need as well. Among the bonuses (which are few because so much is included in the film), there is one on the fates of actors. For each Gitt supplies both a clip of the actor in a silent film and in a sound one. The actors whose careers took a nose dive in sound films are represented by Rod La Roque, Norma Talmadge, John Gilbert, and Charles Farrell. Those who successfully made the transition are Ronald Colman, Joan Crawford, William Powell, and Laurel and Hardy. Gitt makes plausible cases why the public responded to each actor as it did.

As the disc’s title implies, it is intended to be part of a series of three documentaries that will cover the entire century. If Gitt continues to get access to the sort of material he presents here, the result should be an impressive overview of the subject and a boon to educators. If in the 1970s and 1980s we had dreamt up our ideal documentary subject for teaching early sound, it would have looked a lot like A Century of Sound—except we couldn’t have imagined all the material that existed in the vaults, waiting to be found and restored.

A Century of Sound is not available commercially. Educators and researchers can request a free copy (with a $10 shipping charge) by downloading a pdf form here.

The Jazz Singer (Warner Bros.)

Released this past October, this three-disc deluxe set marks the first time that The Jazz Singer has been on DVD. (Legally, that is; there was apparently a Chinese bootleg.) It also includes numerous supplements, some of which might be useful for teaching the introduction of sound.

The first disc contains the restored print of The Jazz Singer, a complete version of Al Jolson’s Vitaphone short, A Plantation Act, and some other shorts. One of these is the classic Tex Avery cartoon, I Love to Singa, inspired by The Jazz Singer and starring “Owl Jolson.”

An 85-minute documentary, The Dawn of Sound: How Movies Learned to Talk is the main item on the second disc. It was made by Turner Entertainment and bears a copyright date of 2007. Like so many TV shows, it doesn’t trust enough in the inherent interest of its topic. Rather than explaining the sound systems clearly by type, the writers have opted to try and stress the four Warner brothers as interesting personalities (not very successfully) and the intense competition among the sound systems in the late 1920s. The opening third cuts together too many brief, unidentified film clips and talking-heads comments, which doesn’t make for a coherent introduction to the topic. The production of the Vitaphone shorts is not well explained, though the film does point out that the shorts were more influential than Don Juan in making the new process appeal to audiences. There are excerpts from the main early Warners sound films, as well as a section on actors who succeeded or failed in talkies.

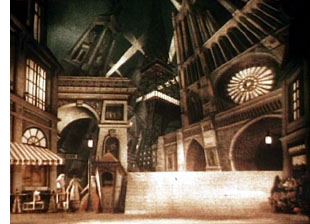

Another item on this second disc is the entire surviving footage—two scenes—from Gold Diggers of Broadway, a two-strip Technicolor musical from 1929. It’s rather an arbitrary inclusion, but as it’s not likely to come out on DVD in any other context, we should be grateful to have it. The scenes are pretty dreadful, apart from the spectacularly cubistic melange of Parisian landmarks in the set.

Another item on this second disc is the entire surviving footage—two scenes—from Gold Diggers of Broadway, a two-strip Technicolor musical from 1929. It’s rather an arbitrary inclusion, but as it’s not likely to come out on DVD in any other context, we should be grateful to have it. The scenes are pretty dreadful, apart from the spectacularly cubistic melange of Parisian landmarks in the set.

The rest of the disc consists mainly of some older documentaries on early sound made by Warner Bros. One, The Voice from the Screen (1926) was intended as a demonstration of Vitaphone for technicians. The presenter is not, to say the least, charismatic, and it’s obvious why Discovering Cinema and A Century of Sound use only excerpts. Nice to have it complete, but students wouldn’t sit still for the whole thing. The Voice that Thrilled the World was directed by Jean Negulescu in 1943, on the occasion of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences adding a best-sound Oscar—the first of which happened to go to Warners’ Yankee Doodle Dandy. This short seems to be the source for the staged footage of early sound breakthroughs that show up, unidentified, in The Dawn of Sound and the other documentaries. Not surprisingly, The Voice that Thrilled the World primarily hypes the Vitaphone process.

“Okay for Sound” (1946) celebrated the twentieth anniversary of Don Juan’s premiere, and it recycles a lot of material from the 1943 short. Like The Voice that Thrilled the World, it was a theatrical short, intended as much to promote current Warners’ films as to celebrate the studio’s past triumphs. The film handily includes an extended clip of Jolson singing the saccharine “Sonny Boy” number in The Singing Fool (1928).

(A companion book with a slightly different title, “Okay for Sound!” was published in 1946. It’s a picture history of sound. The photos are not well produced, and many are just publicity stills from films. It does contain quite a few photos of sound equipment. It turns up with surprising frequency in used-book stores. The phrase, by the way, is what recordists would call out to indicate to directors when the sound was operating and the action could start–their equivalent of the camera operators’ “Speed!”)

When the Talkies Were Young (1955) is an odd, low-budget documentary that consists of fairly extended clips from some early Warners’ talkies: Sinners’ Holiday (1930), 20,000 Years in Sing Sing (1932), Night Nurse (1931), Five Star Final (1931), and Svengali (1931). These aren’t bad, though unfortunately the narrator occasionally interjects comments during the action.

The third disc contains over three and a half hours of restored Vitaphone shorts, a treasure trove for teachers who want to show some examples of these. The first one, Behind the Lines (1926), is the example we use in our box on “Early Sound Technology and the Classical Style” in Chapter 9 of Film History: An Introduction (see Figures 9.4 and 9.5, p. 197 in the second edition).

If I had to make a choice of just one of these three DVD releases in looking for clips for a unit on early sound, I would favor A Century of Sound as having the best organized presentation and the most useful set of excerpts. The “Learning to Talk” disc could be useful as a briefer, self-contained teaching tool. The Jazz Singer package is a bit of a hodgepodge, but educators who want to deal with early sound in depth could pluck out some very useful additional material from it.

A May 12, 1925 Case test with Gus Visser and his duck singing a duet of “Ma, He’s Making Eyes at Me.” (Added to the National Film Registry in 2002 and included in both Learning to Talk and A Century of Sound.)

A behemoth from the Dead Zone

DB here:

The first quarter of the year is the biggest slump time for movie theatres. (1) Holiday fatigue, thin budgets, bad weather, the Super Bowl, and the distractions of the awards season depress admissions. If people go to the movies, they tend to catch up on Oscar nominees, and studios don’t want to release high-end films that might suffer from the competition. But screens need fresh product every week, so most of what gets released at this time of the year might charitably be called second-tier.

Ambitious filmmakers fight to keep out of this zone of death. You could argue that the January release slot of Idiocracy told Mike Judge exactly what Fox thought of that ripe exercise in misanthropy. Zodiac, one of the best films of 2007, opened on 1 March, and even ecstatic reviews couldn’t push it toward Oscar nominations. You can imagine what chances for success Columbia has assigned to Vantage Point (a 22 February bow). [But see my 4 Feb. PPPS below.]

Yet this is a flush period for those of us who like to explore low-budget genre pieces. I have to admit I enjoy checking on those quickie action fests and romantic comedies that float up early in the year. They’re today’s equivalent of the old studios’ program pictures, those routine releases that allowed theatres to change bills often. In their budgets, relative to blockbusters, today’s program pix are often the modern equivalent of the studios’ B films.

More important, these winter orphans are often more experimental, imaginative, and peculiar than the summer blockbusters. On low budgets, people take chances. Some examples, not all good but still intriguing, would be Wild Things (1998), Dark City (1998), Romeo Must Die (2000), Reindeer Games (2000), Monkeybone (2001), Equilibrium (2002), Spun (2003), Torque (2004), Butterfly Effect (2004), Constantine (2005), Running Scared (2006), Crank (2006), and Smokin’ Aces (2007). The mutant B can be found in other seasons too—one of my favorites in this vein, Cellular (2004), was released in September—but they’re abundant in the year’s early months.

By all odds, Cloverfield ought to have been another low-end release. A monster movie with unknown players, running a spare 72 minutes sans credits, budgeted at a reputed $25 million, it’s a paradigm of the winter throwaway. Except that it pulled in $46 million over a four-day weekend and became the highest-grossing film (in unadjusted dollars) ever to be released in January. Here the B in “B-movie” stands for Blockbuster.

I enjoyed Cloverfield. It starts with a sharp premise, but as ever, execution is everything. I see it as a nifty digital update of some classic Hollywood conventions. Needless to say, many spoilers loom ahead.

If you find this tape, you probably know more about this than I do

Everybody knows by now that Cloverfield is essentially Godzilla Meets Handicam. A covey of twentysomethings are partying when a monster attacks Manhattan, and they try to escape. One, Rob, gets a phone call from his off-again lover Beth, who’s trapped in a high-rise. He vows to rescue her. He brings along some friends, one of whom documents their search with a video camera. It’s a shooting-gallery plot. One by one, the characters are eliminated until we’re down to two, and then. . . .

Cloverfield exemplifies what narrative theorists call restricted narration. (Kristin and I discuss this in Chapter 3 of Film Art.) In the narrowest case of restricted narration, the film confines the audience’s range of knowledge to what one character knows. Alternatively, as when the characters are clustered in the same space, we’re restricted to what they collectively know. In other words, you deny the viewer a wider-ranging body of story information. By contrast, the usual Godzilla installment is presented from an omniscient perspective, skipping among scenes of scientists, journalists, government officials, Godzilla’s free-range ramblings, and other lines of action. Instead, Cloverfield imagines what Godzilla’s attack would look and feel like on the ground, as observed by one group of victims.

Horror and science fiction films have used both unrestricted and restricted narration. A film like Cat People (1942) crosscuts what happens to Irena (the putative monster) with scenes involving other characters. Jurassic Park and The Host likewise trace out several plot strands among a variety of characters. The advantage of giving the audience so much information is that it can feel apprehension and suspense about what the characters don’t know is happening. Our superior knowledge can make us worry about those poor victims oblivious to their fate.

But these genres have relied on restricted narration as well. Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) is a good example; we are at Miles’s side in almost every scene, learning of the gradual takeover of his town as he does. Night of the Living Dead (1968), Signs (2002), and War of the Worlds (2005) do much the same with a confined group, attaching us to one or the other momentarily but never straying from their situation.

The advantages of restricted narration are pretty apparent. You can build up uncertainty and suspense if we know no more than the character(s) being attacked by a monster. You can also delay full revelation of the creature, a big deal in these genres, by giving us only the glimpses of it that our characters get. Arguably as well, by focusing on the characters’ responses to their peril, you have a chance to build audience involvement. We can feel empathy and loss if we’ve come to know the people more intimately than we know the anonymous hordes stomped by Godzilla. Finally, if you need to give more wide-ranging information about what’s happening outside the characters’ immediate situation, you can always have them encounter newspaper reports, radio bulletins, and TV coverage of action occurring elsewhere.

People sometimes think that theoretical distinctions like this overintellectualize things. Do filmmakers really think along these lines? Yes. Matt Reeves, the director of Cloverfield, remarks:

The point of view was so restricted, it felt really fresh. It was one of the things that attracted me [to this project]. You are with this group of people and then this event happens and they do their best to understand it and survive it, and that’s all they know.

For your eyes only

Restricted narration doesn’t demand optical point-of-view shots. There aren’t that many in Invasion of the Body Snatchers or the other examples I’ve indicated. Still, for quite a while and across a range of genres, filmmakers have imagined entire films recording a character’s optical/ auditory experience directly, in “first-person,” so to speak.

Again, it’s useful to recognize two variants of this narrational strategy. One we can call immediate—experiencing the action as if we stood in the character’s shoes. In the late 1920s, the great documentary filmmaker Joris Ivens tried to make what he called his I-film, which would record exactly what a character saw when riding a bike, drinking a glass of beer, and the like. He was dismayed to find that bouncing and swiveling the camera as if it were a human eye ignored the fact that in real life, our perceptual systems correct for the instabilities of sensation. Ivens abandoned the project, but evidently he couldn’t get the notion out of his head; he called his autobiography The Camera and I. (2)

Hollywood’s most strict and most notorious example of directly subjective narration is Robert Montgomery’s Lady in the Lake (1947). Its strangeness reminds us of some inherent challenges in this approach. How do you show the viewer what your protagonist looks like? (Have him pass in front of mirrors.) How do you skip over the boring bits? (Have your hero knocked unconscious from time to time.) How do you hide the inevitable cuts? (Try your best.) Even Montgomery had to treat the subjective sequences as long flashbacks, sandwiched within scenes of the hero in his office in the present telling us what he did next.

Because of these problems, a sustained first-person immediate narration is pretty rare. The best compromise, exploited by Hitchcock in many pictures and especially in Rear Window (1954), is to confine us to a single character’s experience by alternating “objective” shots of the character’s action with optical point-of-view shots of what s/he sees.

What I’m calling immediate optical point of view is just that: sight (and sounds) picked up directly, without a recording mechanism between the story action and the character’s experience. But we can also have mediated first-person point of view. The character uses a recording technology to give us the story events.

In a brilliant essay on the documentary Kon-Tiki (1950), André Bazin shows that our knowledge of how Thor Heyerdahl filmed his raft voyage lends an unparalleled authenticity to the action. Heyerdahl and his crew weren’t experienced photographers and seem to have taken along the 16mm camera as an afterthought, but the very amateurishness of the enterprise guaranteed its realism. Its imperfections, often the result of hazardous conditions, were themselves testimony to the adventure. When the men had to fight storms, they had no time to film; so Bazin is able to argue, with his inimitable sense of paradox, that the absence of footage during the storm is further proof of the event. If we were given such footage, we might wonder if it was staged afterward.

How much more moving is this flotsam, snatched from the tempest, than would have been the faultless and complete report offered by an organized film. . . . The missing documents are the negative imprints of the expedition. (3)

What about fictional events? In the 1960s we started to see fiction films that presented themselves as recordings of the events as the camera operator experienced them. One early example is Stanton Kaye’s Georg (1964). The first shot follows some infantrymen into battle, but then the framing wobbles and the camera falls to earth. We see a tipped angle on a fallen solider and another infantryman approaches.

He bends toward us; the frame starts to wobble and we are lifted up. On the soundtrack we hear, “I found my camera then.”

The emergence of portable equipment and cinema-verite documentary seems to have pushed filmmakers to pursue this narrational mode in fiction. One result was the pseudo-documentary, which usually doesn’t present the story as a single person’s experience but rather as a compilation of first-person observations. Peter Watkins’ The War Game (1967) presents itself as a documentary shot during a nuclear war, and it contains many of the visual devices that would come to be associated with the mediated format—not only the flailing camera but the face-on interview and the chaotic presentation of violent action. There’s also the pseudo-memoir film, pioneered in David Holzman’s Diary (1967). Later examples of the pseudo-documentary are Norman Mailer’s Maidstone (1971) and the combat movie 84 Charlie MoPic (1989). (4)

As lightweight 16mm cameras made filming easier, directors adapted that look and feel to fictional storytelling. The arrival of ultra-portable digital cameras and cellphones has launched a similar cycle. Brian DePalma’s Redacted (2007), yet another war film, has exploited the technology for docudrama. A digital equivalent of David Holzman’s Diary, apart from Webcam and YouTube material, is Christoffer Boe’s Offscreen (2006), which I discussed here.

Interestingly, Orson Welles pioneered both the immediate and the mediated subjective formats. One of his earliest projects for RKO was an adaptation of Heart of Darkness, in which the camera was to represent the narrator Marlowe’s optical perspective throughout. (5) Welles had more success with the mediated alternative, though in audio form. His “War of the Worlds” radio broadcast mimicked the flow of programming and interrupted it with reports of the aliens’ attack. The device was updated for television in the 1983 drama Special Bulletin.

Sticking to the rules

Cloverfield, then, draws on a tradition of using technologically mediated point-of-view to restrict our knowledge. Like The Blair Witch Project (1999), it does this with a horror tale. But it’s also a Hollywood movie, and it follows the norms of that moviemaking mode. So the task of Reeves, producer J. J. Abrams, and the other creators is to fit the premise of video recording to the demands of classical narrative structure and narration. How is this done?

First, exposition. The film is framed as a government SD video card (watermarked DO NOT DUPLICATE), the remains of a tape recovered from an area “formerly known as Central Park.” This is a modern version of the discovered-manuscript convention familiar from the nineteenth-century novel. When the tape starts, showing Rob with Beth in happy times, its read-out date of April plays the role of an omniscient opening title. In the course of the film, the read-outs (which come and go at strategic moments) will tell us when we’re in the earlier phase of their love affair and when we’re seeing the traumatic events of May.

Likewise, the need for exposition about characters and relationships at the start of the film is given through a basic premise. Jason wants to record Rob’s going-away-party and he presses Rob’s friend Hud into service as the cameraman. Off the bat, Hud picks out our main characters in video portraits addressed to Rob. What follows indicates that Hud will be amazingly prescient: His camera dwells on the characters who will be important in the ensuing action.

Next, overall structure. The Cloverfield tape conforms to the overarching principles that Kristin outlines in Storytelling in the New Hollywood and that I restated in The Way Hollywood Tells It. (Another example can be found here.) A 72-minute film won’t have four large-scale parts, most likely two or three. As a first approximation, I think that Cloverfield breaks into:

*A setup lasting about 30 minutes. We are introduced to all the characters before the monster attacks. Our protagonists flee to the bridge, where Jason dies. Near the end of this portion, Rob gets a call from Beth, and he formulates the dual goals of the film: to escape from the creature, and to rescue Beth. Along the way, Hud declares he’s going to record it all: “People are gonna know how it all went down. . . . It’s gonna be important.”

*A development section lasting about 22 minutes. This is principally a series of delays. Rob, Hud, Lily, and Marlena encounter obstacles. Marlena falls by the wayside. They are given a deadline: At 0600 they must meet the last helicopters leaving Manhattan.

*A climax lasting about 20 minutes. The group rescues Beth and meets the choppers, but the one carrying Rob, Hud, and Beth falls afoul of the beast. They crash in Central Park, and Hud is killed, his camera recording his death at the jaws of the monster. Huddled under a bridge, Rob and Beth record a final video testimonial before an explosion cuts them off.

*An epilogue of one shot lasting less than a minute: Rob and Beth in happier times on the Ferris wheel at Coney Island—a shot left over from the earlier use of the tape in April.

Next, local structure and texture. It takes a lot of artifice to make something look this artless. The imagery is rich and vivid, the sharpest home video you ever saw. The sound is pure shock-and-awe, bone-rattling, with a full surround ambience one never finds on a handicam. (6) Moreover, Hud is remarkably lucky in catching the turning points of the action. All the characters’ intimate dramas are captured, and Hud happens to be on hand when the head of Miss Liberty hurtles down the street.

Bazin points out that in fictional films the ellipses are cunning gaps, carefully designed to fulfill narrative ends—not portions left out because of the physical conditions of the shoot. Here the cunning gaps are justified as constrained by the physical circumstances of filming. When Hud doesn’t show something, it’s usually because it’s what the genre considers too gross, so the worst stretches take place in darkness, or offscreen, or strategically shielded by a prop when the camera is set down.

Mostly, though, Hud just shows us the interesting stuff. He turns on the camera just before something big happens, or he captures a disquieting image like that of the empty Central Park carriage.

At least once, the semi-documentary premise does yield something evocative of the Kon-Tiki film. Hud has to leap from one building to another, many stories above the street. He turns the camera on himself: “If this is the last thing you see, then I died.” He hops across, still running the camera, but when a rocket goes off nearby, a sudden cut registers his flinch. For an instant out of sheer reflex, he turned off the camera.

Overall, Hud’s tape respects the flow of classical film style. Unlike the Lady in the Lake approach, the mediated POV format doesn’t have a problem with cuts; any jump or gap is explained as a moment when the operator switched off the camera. Most of Hud’s “in-camera” cuts are conventional ones, skipping over a few inconsequential stretches of time. There are as well plenty of hooks between scenes. (For more on hooks, go here.) Hud says: “I’ll walk in the tunnels.” Cut to characters walking in the tunnels. More interestingly, visible cuts are rare, which again respects the purported conditions of filming. Cloverfield has much longer takes than any recent Hollywood film I know. I counted only about 180 shots, yielding an average of 24 seconds per shot (in a genre in which today’s films average 2-5 seconds per shot).

The digital palimpsest

We could find plenty of other ways in which Cloverfield adapts the handicam premise to the Hollywood storytelling idiom. There are the product placements that just happen to be part of these dim yuppies’ milieu. There are the character types, notably the sultry Marlena and the hero’s weak friend who’s comically a little slow. There’s the developing motif of the to-camera addresses, with Rob and Beth’s final monologues to the camera counterbalancing the party testimonials in the opening. There’s the final romantice exchange: “I love you.” “I love you.” The very last shot even includes a detail that invites us to re-view the entire movie, at the theatre or on DVD. But let me close by noting how some specific features of digital video hardware get used imaginatively.

I’ve already mentioned how the viewfinder date readout allows us to keep the time structure clear. There’s also the use of a night-vision camera feature to light up those spidery parasites shucked off by the big guy. Which scares you more—to glimpse the pinpoint eyes of critters skittering around you in the dark, or to see them up close in a sickly green light?

More teasing is the fact, set up in the first part, that this video is being recorded over an old tape of Rob’s. That’s what turns the opening sequence of Rob and Beth in May into a prologue: the tape wasn’t rewound completely for recording the party. Later, at intervals, fragments of that April footage reappear, apparently through Hud’s inadvertently advancing the tape. The snippets functions as flashbacks, showing Rob and Beth going to Coney Island and juxtaposing their enjoyable day with this horrendous night.

Cleverly, on the tape that’s recording the May disaster something always prepares the audience for the shift. For instance, when Jason hands the camera over, we hear Hud say, “I don’t even know how to work this thing.” Cut to an April shot of Beth on the subway, suggesting that he’s advanced fast forward without shooting. Likewise, when Rob says, “I had a tape in there,” we cut to another April shot of Beth. As a final fillip, the footage taken in May halts before the tape ends, so we get the epilogue showing Rob and Beth on the Ferris wheel in April, emerging like figures in a palimpsest.

No less clever, but also a little poignant, is the use of the fallen-camera convention. It appears once when Beth has to be extricated from her bed. Hud sets the camera down by a concrete block in her bedroom, which conceals her agony. More striking is the shot when the camera, dropped from Hud’s hand, lies in the grass, and the autofocus device oscillates endlessly, straining to hold on his lifeless face.

In sum, the filmmakers have found imaginative ways of fulfilling traditional purposes. They show that the look and feel of digital video can refresh genre conventions and storytelling norms. So why not for the sequel show the behemoth’s attack from still other characters’ perspectives? This would mobilize the current conventions of the narrative replay and the companion film (e.g., Eastwood’s Iwo Jima diptych). Reeves says:

The fun of this movie was that it might not have been the only movie being made that night, there might be another movie! In today’s day and age of people filming their lives on their iPhones and Handycams, uploading it to YouTube. . . .

So the Dead Zone of January through March yields another hopeful monster. What about next month’s Vantage Point? The tagline is: 8 Strangers. 8 Points of View. 1 Truth. Hmmm. . . . Combining the network narrative with Rashomon and a presidential assassination. . . . Bet you video recording is involved . . . . See you there?

PS: At my local multiplex, you’re greeted by a sign: WARNING: CLOVERFIELD MAY INDUCE MOTION SICKNESS. I thought this was just the theatre covering itself, but I’ve learned that no recent movie, not even The Bourne Ultimatum, has had more viewers going giddy and losing their lunch. You can read about the phenomenon here, and Dr. Gupta weighs in here. My gorge can rise when a train jolts, but I had no problems with two viewings of Cloverfield, both from third row center.

Anyhow, it will be perfectly easy to watch on your cellphone. But we should expect to see at least one pirate version shot in a theatre by someone who’s fighting back the Technicolor yawn, giving us more Queasicam than we bargained for.

(1) The only period that rivals this slow winter stretch is mid-August to October, when genre fare gets pushed out to pick up on late summer business. [Added 26 January:] There are, I should add, two desirable weekends in the first quarter, those around Martin Luther King’s birthday and Presidents’ Day. Studios typically aim their highest-profile winter releases (e.g., Black Hawk Down, 2001) for those weekends.

(2) Joris Ivens, The Camera and I (New York: International Publishers, 1969), 42.

(3) André Bazin, “Cinema and Exploration,” What Is Cinema? Vol. 1, trans. and ed. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), 162.

(4) Not all pseudodocumentaries present themselves as records of a person’s observation. Milton Moses Ginsberg’s Coming Apart (1969) presents itself as an objective record, by a hidden camera, of a psychiatrist’s dealings with his patients. Like a surveillance camera, it doesn’t purport to embody anybody’s point of view.

(5) Jonathan Rosenbaum, Discovering Orson Welles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 28-48.

(6) For Kevin Martin’s informative account of the film’s polished lighting and high-definition video capture, go here (and scroll down a bit). For discussions of contemporary sound practices in this genre, see William Whittington’s Sound Design in Science Fiction (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007).

PS: Thanks to Corey Creekmur for correcting two slips in my initial post!

PPS 28 January: Lots of Internet buzz about the film since I wrote this. Thanks to everyone who linked to this post, and special thanks for feedback from John Damer and James Fiumara.

Some people have asked me to comment on the social and cultural implications of Cloverfield’s references to 9/11. At this point I think that genre cinema has dealt more honestly and vividly with the traumas and questioning around this horrendous event than the more portentous serious dramas like United 93, World Trade Center, and the TV show The Road to 9/11.

The two most intriguing post-9/11 films I know are by Spielberg. The War of the Worlds gives a really concrete sense of what a hysterical America under attack might be like, warts and all. (It reminded me of a TV show I saw as a kid, Alas, Babylon (1960), a surprisingly brutal account of nuclear-war panic in suburbia.) Spielberg’s underrated The Terminal reminds us, despite its Frank Capra optimism, that the new Security State is run by bureaucrats with fixed agendas and staffed by overworked people of color, some themselves exiles and immigrants.

I think that Cloverfield adds its own dynamic sense of how easily the entitlement culture of upwardly mobile twentysomethings can be shattered. Genre films carry well-established patterns and triggers for feelings, and a shrewd filmmaker can channel them for comment on current events—as we see in the changing face of Westerns and war films in earlier phases of Hollywood history.

On this point, Cinebeats offers some shrewd responses to criticisms of Cloverfield here.

Finally: In the new Creative Screenwriting an informative piece (not available online) indicates that the initial logline for Vantage Point on imdb is misleading. Screenwriter Barry Levy planned to present the assassination from seven points of view, but reduced that to six. As for my speculation that video recording/replay would be involved, a production still seems to offer some evidence. Shall we call it the Cloverfield effect? The same issue of CS has a brief piece on the script for Cloverfield.

Finally: In the new Creative Screenwriting an informative piece (not available online) indicates that the initial logline for Vantage Point on imdb is misleading. Screenwriter Barry Levy planned to present the assassination from seven points of view, but reduced that to six. As for my speculation that video recording/replay would be involved, a production still seems to offer some evidence. Shall we call it the Cloverfield effect? The same issue of CS has a brief piece on the script for Cloverfield.

PPS 30 January: Shan Ding brings me another story about the making of Cloverfield, and Reeves is already in talks for a sequel, says Variety.

PPPS 4 February: A recent story in The Hollywood Reporter offers a nuanced account of how Hollywood is rethinking its first-quarter strategies. Across the last 4-5 years, a few big releases have done fairly well between January and April; a high-end film looks bigger when there is less competition. The author, Steven Zeitchik, suggests that the heavy packing of the May-August period and the need for a strong first weekend are among the factors that will encourage executives to spread releases through the less-trafficked months. I hope, though, that tonier fare won’t crowd out the more edgy, low-end genre pieces that bring me in.

PPPPS 8 February: How often has a wounded Statue of Liberty featured in the apocalyptic scenarios of comics and the movies? Lots, it turns out. Gerry Canavan explains here.

Manhattan: Symphony of a Great City

DB here:

In December Kristin and I attended a wide-ranging conference at Rome University devoted to “Exploded Narration”—the effects that digital technology has had on storytelling in film and television. As our host Vito Zagarrio put it, the question is one of continuity or rupture. Have new formats like HD, the Internet, and DVD revolutionized media storytelling? Or are they serving traditional approaches?

Many papers explored the “rupture” option, while Kristin and I offered presentations that emphasized continuity. You can find one version of my argument elsewhere on this site. Still, both of us also pointed up some innovations, or what I called “spillover” effects. As so often with such questions, the answer turned out to be complicated.

We enjoyed the conference, and one standout aspect was the presence of Amos Poe. Poe is probably best known for his first feature, Alphabet City (1985), and for his 16mm film on the Punk scene, The Blank Generation (1976). His Triple Bogey on a Par Five Hole (1991) has also attracted attention. For three decades Poe has worked as a director, producer, screenwriter, and teacher. The Sundance festival is playing Amy Redford’s The Guitar, which Poe wrote and coproduced.

We enjoyed the conference, and one standout aspect was the presence of Amos Poe. Poe is probably best known for his first feature, Alphabet City (1985), and for his 16mm film on the Punk scene, The Blank Generation (1976). His Triple Bogey on a Par Five Hole (1991) has also attracted attention. For three decades Poe has worked as a director, producer, screenwriter, and teacher. The Sundance festival is playing Amy Redford’s The Guitar, which Poe wrote and coproduced.

Amos was great fun. A soft-spoken man with a quick and wicked sense of humor, he enlivened our dinners at various ristoranti. He also spoke extensively about screenwriting, which he teaches at NYU and at NYU’s Florence program. Like many screenwriters, he’s extremely intelligent and articulate about his craft. Three examples:

*How to learn screenwriting? Get a script version of a film you admire. Read the first ten pages, then closely watch the first ten minutes of the movie. Go back and read the next ten pages, and go ahead and watch the corresponding ten minutes. And so on until the end. Do this with three first-rate films, and you will have a concrete, intuitive understanding of how a screenplay works.

*A screenplay, Amos points out, isn’t a short story or novel or play. It’s a movie in words. It must make the reader see and hear an imaginary film, and not only the action, either. Without indicating specific shots, the descriptions should suggest the flow of long-shots and close-ups (”Her lipstick leaves a smear on the cigarette butt”). “The screenwriter is a filmmaker.”

*Write sounds into the background of scenes, setting them up for fuller presence later. If a train becomes important late in the story, mention the wail of a distant train early in the screenplay. This sort of auditory planting quietly strengthens the structure of the story in your reader’s mind.

Amos must be a terrific teacher. I learned a great deal from his descriptions of contemporary film conventions, several of which I hadn’t noticed before. Don’t be surprised to find some of them creeping into future blogs.

Given Amos’ expertise in mainstream storytelling, the film he presented was quite a surprise. It’s called Empire II, and though you don’t normally call a three-hour movie a delight, I can’t think of a better word. After a week of tourism and no films, it was just the sensuous boost that my hungry eyes needed.

Man with a Video Camera

Poe’s apartment on Christopher Street yields a stunning view of the Manhattan skyline—the Chrysler Building, Jefferson clock tower, and of course the Empire State Building. He planted a Sony PD150 video camera at his window for a year, from 1 November 2005 to 31 October 2006, and took time-lapse shots. Through single-framing, he captured a total of 1 or 1 ½ seconds of every thirty seconds of real time. He shot traffic, people, skies, and the horizon. He did not look at the footage until after the year was up.

He wound up with sixty hours of imagery. He then made an absolute gesture. Using Final Cut Pro, he compressed all sixty hours into three. What was already highly elliptical, a string of tiny slices of action, became enormously accelerated.

Poe and his students then spent months blending up to forty tracks of music, spoken verse, and sound effects. It’s a crisp stereo mix, with remarkable audio-visual correspondences: whipping wind and ticking machinery sync up with snow and the tower clock. The music, which ranges from alt-rock to Keith-Jarrettish piano strumming, works sympathetically but not redundantly with the imagery. (No surprise that Poe has made music videos.) Shooting the film cost virtually nothing, but Poe spent about $100,000 for music clearances, though old friends like Patti Smith and Deborah Harry gave him their material for free.

The result is a city symphony, a lyrical tribute to the looks and sounds of New York. It joins the tradition of Walter Ruttmann and Dziga Vertov, as well as Paul Strand’s Manhatta (1921) and Jay Leyda’s Bronx Morning (1931). It also reminds you that Poe has roots in the downtown avant-garde. In 1972-1975, he often watched works by Jonas Mekas, Stan Brakhage, Michael Snow, Bruce Baillie, and Jack Smith at Millennium Film Workshop, and he made films for its Friday night open screenings. As a result, Empire II carries premises of lyrical and Structural cinema into the digital era.

The conditions of production are at once subjected to strict guidelines—a single year, only views from the window, the 20x compression—and open to chance. As with the films of Ernie Gehr, chance becomes more felicitous when set within a rigid frame. “I needed to create a base for accidents to happen.” Poe refused to cut or rearrange what he had (”I don’t edit unless I get paid for it”) and so he was ready to accept what came out. “I had to let go of the result.” That result mixes smoothness and fracture; the moon arcs like a golf ball, but traffic hammers relentlessly in a way recalling the last sequence of Man with a Movie Camera. Every so often there are calm islands of blank frames, provided by Poe’s occasional neglect to set focus or exposure.

Poe’s Book of Hours and Days

The title pays homage to Warhol’s 1964 film, so often discussed and so little seen. In many ways, though, Poe gives us an anti-Empire. Instead of a silent film, sound, both aggressive and immersive. (The stereo tracks shoot noises bouncing across channels, swallowing you up.) Instead of a single night, a year’s time span. Warhol shot Empire at 24 frames per second but insisted on projecting it at 16, slowing up time; Poe’s single-frame sampling and frantic acceleration speed time up. Warhol used for the most part a single camera position and shot in long takes, but Poe presents a flutter of shots. The framing is steady, but what we see flickers and pulsates, creating superimposition effects comparable to Ruttmann’s and Vertov’s slashing diagonals.

Warhol was withdrawn and impersonal, but Poe turned on the camera when he spotted something that looked interesting. He felt free to focus, reframe, zoom, and shift camera position for different angles on the life beyond his balcony. Likewise, the automaton Warhol (”I’d like to be a machine”) is counterposed to Poe’s more organic sensibility. He never lets us forget the flowers twitching on his windowsill, and their growth and rearrangements become traces of his daily life in the apartment.

The rules are simple and viewer-friendly. We instantly recognize the trappings of city life; we know the cycles of the seasons and the shifts between night and day. This cogent structure throws all our attention on what we see from moment to moment, and how we see it.

The Empire State Building and the skyline around it, along with the flowing clouds, remain stable reference points for a flurry of visual transformations. The taxis and pedestrians we glimpse move in jagged, incomplete rhythms very different from the smooth flow of fast motion in Godfrey Reggio’s films like Koyaanisqatsi.

As you see, high angles, plays of focus, and tight framings provide energetic abstraction. Flaring exposure makes the Building look like it’s in flames, triggering echoes of the 9/11 attacks.

When the weather changes, the light does too. Raindrops become not only a pebbly surface on the windows but tiny filters. As with Warhol’s films, we have to change our conception of what counts as an event. Slight differences of framing and texture become visual epiphanies. Rain can be gray-green, and snow can go pale red. At times, the steeple clock face in the lower right becomes an imperturbable timekeeper, a sort of pictorial timecode, reminiscent of the clock in the corner of the shots of Robert Nelson’s Bleu Shut (1971).

Spring comes about halfway through. It’s as lyrical as you’d expect, but again the colors startle. If snow can be red, then budding trees can be blindingly white.

As in Ives’ Holidays Symphony, the festive iconography of Americana is made somewhat dissonant. July Fourth fireworks become splinters, and the slurred, jerky figures in the final Halloween chapter recall Mekas’ Notes on the Circus. Now shooting more continuously, with handheld shots and bumpy pans and zooms, Poe lets his 20x compression turn the parading ghosts, skeletons, nuns, and dark angels into scurrying hallucinations, complete with cellphones.

Empire II is at once exuberant and tranquil. What a pleasure to find a film devoted simply to seeking out beauty in everyday surroundings. “She celebrates the small,” sings Jimmie James while we see snow lashing the sidewalks. So does Poe. He has said that he made the film at a difficult period of his life, but what he has given us, I think, is jubilation.

PS 22 Jan: For more on Empire II, including a trailer, go to amospoe.com.

Happy birthday, classical cinema!, or The ten best films of … 1917

Wild and Woolly (1917).

KT:

Periodization is a tricky task for historians, and there are a lot of disputes about how to divide up the 110-plus years of the cinema’s existence. We all have to deal with it, though, if we want to organize our studies of the past into meaningful units. How to do that?

Do we divide the periods of film history according to major historical events? World War I had a huge impact on the film industry, to be sure, and we might say that one significant period for cinema is 1914-1918. Yet 1919 didn’t mark the start of a new period. The major European post-war film movements didn’t start then. French Impressionism arguably began in 1918, German Expressionism in 1920, and Soviet Montage in 1924 or 1925.

Carving up film history partly depends on what questions the historian is asking. If you’re studying wartime propaganda, 1914 and 1918 would provide significant beginning and end points. If you want to trace the development of significant film styles, it doesn’t seem very useful.

While historians have difficulties agreeing on periodization, just about everyone concurs that there were two amazing years during the 1910s when filmmaking practice somehow coalesced and produced a burst of creativity: 1913 and 1917.

One can point to stylistically significant films made before 1913. Somehow, though, that year seemed to be when filmmakers in several countries simultaneously seized upon what they had already learned of technique and pushed their knowledge to higher levels of expressivity. “Le Gionate del Cinema Muto” (“The Days of Silent Cinema”), the major annual festival, devoted its 1993 event to “The Year 1913.” The program included The Student of Prague (Stellan Rye), Suspense (Phillips Smalley and Lois Weber), Atlantis (August Blom), Raja Harischandra (D. G. Phalke), Juve contre Fantomas (Louis Feuillade), Quo Vadis? (Enrico Guazzoni), Ingeborg Holm (Victor Sjöström), The Mothering Heart (D. W. Griffith), Ma l’amor mio non muore! (Mario Caserini), L’enfant de Paris (Léonce Perret), and Twilight of a Woman’s Soul (Yevgenii Bauer). .

1917, by contrast, was primarily an American landmark. As 2007 closes, we thought it appropriate to wish happy birthday to the most powerful and pervasive approach to filmic storytelling the world has yet seen. That would be classical continuity cinema, synthesized in what was coming to be known as Hollywood.

DB:

In The Classical Hollywood Cinema and work we’ve done since, we’ve maintained that 1917 is the year in which we can see the consolidation of Hollywood’s characteristic approach to visual storytelling. This idea was first floated by Barry Salt, and our research confirms his claim. Over the ninety years since 1917 the style has changed, but its basic premises have remained in force.

Before classical continuity emerged, the dominant approach to shooting a scene might be called the tableau technique. Action was played out in a full shot, using staging to vary the composition and express dramatic relationships. Elsewhere on this site I’ve mentioned two major exponents of this approach, Feuillade and Bauer.

When there was cutting within the tableau setup, it usually consisted of inserted close-ups of important details, especially printed matter, like a letter or telegram. Occasionally the close-up of an actor could be inserted, usually filmed from the same angle as the master shot. The tableau approach was more prominent in scenes taking place in interiors; filmmakers were freer about cutting action occurring outdoors.

We shouldn’t think of the tableau as purely “theatrical.” For one thing, the master shot was typically closer and more tightly organized than a scene on the stage would be. Moreover, for reasons I discuss in Figures Traced in Light, the playing space of the cinematic frame is quite different from the playing area of the proscenium theatre. The filmmaker can manipulate composition, depth, and blocking in ways not available on the stage.

The tableau approach was the default premise of US filmmaking through the early 1910s. You can see it at work, for example, in this shot from At the Eleventh Hour (W. V. Ranous, 1912). Mr. and Mrs. Richards are in the study of Mr. Daley. After Richards has refused to sell his railroad bonds, Daley’s wife shows off her diamond necklace to the visitors.

At first the two couples are separated in depth, the men in the foreground and the women further back. In the first frame below, a new necklace has just been delivered, and a servant gives it to Mrs. Daley. Only the servant’s hand is visible, as she is blocked by Richards in the foreground. In the second frame, the two women come forward. Mrs. Daley holds the necklace up and Mrs. Richards oohs and ahhs over it, while her husband glances at Daley as if to wonder how he could afford it.

Instead of breaking the scene into closer views, spreading the characters’ reactions across separate shots, Ranous squeezes all of their actions and expressions into a tight space across the center of the shot. Nor does he provide a close-up of the necklace, which will be important in the plot. (1) We might be inclined to say that this is a “theatrical” shot, but on a stage the actions in depth (the women chatting, the servant handing over the parcel) wouldn’t be visible to everyone in the auditorium. Likewise, on a stage the packed faces in the later phase of the scene wouldn’t be visible to people sitting on the sides.

As films became longer, American filmmakers were starting to organize their plots around characters with firm goals. Conflicting goals would set the characters in opposition to one another, and at a climax, usually under the pressure of a deadline, the protagonist achieves or fails to achieve the goals. The plot also tends to build up two lines of action, at least one involving romance.

There’s no reason this conception of narrative could not have been applied to the tableau style; in many cases it was. But hand in hand with the rise of goal-driven plotting came a new approach to filming. Sporadically before 1917, filmmakers in many countries were exploring ways to build scene out of many shots. (If you want to know the process in the US in more detail, check out Early American Cinema in Transition by Charlie Keil.) By 1917, American filmmakers had synthesized these tactics into an overall strategy, a system for staging, shooting, and cutting dramatic action.

We know the result as the 180-degree system. This encourages the filmmaker to break a scene into several shots, taken from different distances and angles, all from one side of an imaginary line slicing through the space. Around 1917, this stylistic approach comes to dominate US feature films, in the sense that every film made will tend to display all the devices at least once. The system remains in place to this day, and it came to form the basis of popular cinemas across the world. (2)

Once you break a scene into several shots, some characters won’t be onscreen all the time. So you need to be clear about where offscreen characters are; you need to supply cues that allow the audience to infer their positions. So 1910s filmmakers developed various ways of “matching” shots.

Shots can be connected by character looks, thanks to the eyeline match. Here’s an instance from Victor Schertzinger’s The Clodhopper (1917). First there is a master shot of the mother and son in their farm kitchen.

This is followed by a separate shot of each one. Their bodily positions and eyelines remind us that the other is just out of frame.

Although over-the-shoulder shooting hadn’t yet been developed, a conception of the reverse angle is at work here too. Schertzinger’s camera doesn’t shoot the actors perpendicularly, but takes up an angle on one that becomes an echo of that filming the other. Here’s another example of reverse angles from The Devil’s Bait (1917, director Harry Harvey).

The camera doesn’t just enlarge a portion of the space, as in the inserted shot in a tableau scene. The angle of view has changed significantly.

Changes of angle within the scene have become fairly complex by 1917. This strategy is apparent when the action takes place in a theatre, a courtroom, a church, or some other large-scale gathering point. The camera position changes often in this scene from The Girl without a Soul (director John Collins).

The concept of matching extends to physical movement too, through the match on action. This device allows the director to highlight a new bit of space while preserving the continuity of time. In Roscoe Arbuckle’s The Butcher Boy, the cut-in to Fatty (with a change of angle) also matches his gesture of putting his hands on his hips.

Interestingly, even this early, directors have learned to leave a little bit of overlapping action across the cut. If you move frame by frame, you’ll see that Fatty’s gesture is repeated a bit at the start of the second shot.

When a character leaves one frame, he or she can come into another space, from the side of the frame consistent with the 180-degree premise. This is matching screen direction. A cut of this sort lets us know that the next portion of the locale that we see is more or less adjacent to the previous one. In Field of Honor (director Allen Holuban), Wade crosses to Laura, who’s waiting in a carriage. A few years earlier, the director might have presented his greeting in a single deep-space long shot. Instead, Wade exits one shot and enters the next.

Again, the reverse-angle principle governs the camera setups. Wade moves along a diagonal toward the camera and away from it.

More generally, Field of Honor exhibits a polished handling of the new style: lots of reverse shots and eyeline matches, fades that bracket flashbacks, binocular points of view, rack-focus shots, and rapid cutting (there’s even a ten-frame shot). The point is not to claim Field of Honor as an undiscovered masterpiece but rather to indicate that by 1917 a director could handle all the devices with assurance.

Match-cutting devices had been used occasionally before 1917, but by that year filmmmakers melded them into a consistent and somewhat redundant method of guiding the audience through each scene.

The continuity system not only creates a basic clarity about characters’ positions. It can as well generate a speed and accentuation not easily achieved within a single shot. For example, Wade’s frame exit and entrance above is cut so as to skip over moments that he consumes crossing the driveway. Continuity editing enhances the rapid pace of US films, a quality immediately noted by foreign observers in the 1910s and 1920s.

Two of the best films of 1917 exploit the dynamism of continuity cutting. The Doug Fairbanks comedy western, Wild and Woolly, seems designed to prove that American films could proceed at breakneck speed. In climactic scenes, we’re caught in a whirlwind of fast cutting, with the pace set by the hyperactive protagonist, a financier’s son who longs to prove himself as a cowboy.

John Ford’s Straight Shooting proceeds at a more measured pace, but in its final shootout we see a prototype of all the main-street gundowns that will define the Western. Ford provides alternating shots of the cowboys advancing toward each other, framing each man more tightly and concluding with suffocating close-ups of each man’s face, highlighting the eyes.

Sergio Leone, eat your heart out.

Propelled by goal-driven characters and a linear arc of action, films like Wild and Woolly and Straight Shooting are completely understandable and enjoyable today. (But when will we have them on DVD?) Their stories are engrossing and their performances are engaging, but just as important their storytelling technique has become second nature to us. The narrative strategies that coalesced in 1917 remain fundamental to mainstream cinema.(2)

The Mystery of the Belgian Print

KT:

For decades now we have been visiting Brussels and working at the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique/Koninklijk Belgisch Filmarchief. Sometimes I feel that we would know half as much about the cinema were it not for the unfailing hospitality we have been shown, initially by the great archivist Jacques Ledoux and now by his successor Gabrielle Claes. Our indebtedness to this institution and its staff are reflected in David’s named professorship; he is the Jacques Ledoux Professor of Film Studies. We dedicated our Film History: An Introduction, to Gabrielle.

We do whatever favors we can in return for such wonderful help. David lectures regularly at the biannual summer school run by the Flemish Service for Film Culture in partnership with the Royal Film Archive. (David wrote about the 2007 event in an earlier entry.) I try to identify silent films. I am not always successful, but I suppose over the years I have been able to put names to thirty-some mystery prints.

Silent films are more likely to be unidentified than sound ones because it was standard practice to splice in intertitles in the local language. Sometimes too the film’s title was changed. The film’s actors may be forgotten today, or the print may be incomplete, lacking the opening title and credits. Sometimes even the country of origin is unknown.

Back in the early 1990s I was asked to identify a five-reel nitrate print with the title Père et fils. It was an original distribution copy from the silent era. The information on the archival record card listed some possible identifications: Father and Son, a 1913 Vitagraph film or Father and Son, produced by Mica in 1915. It was tentatively thought to be American.

As I watched the film, it quickly became apparent that it was indeed American. It centered on the rivalry between a small dime store owned by the heroine’s father and a modern dime store being built in the same town. The hero is charged with the mission of driving the older store out of business.

So we had our typical goal-driven plot. The style was what David has described as typical of 1917, so that was my tentative dating. I felt almost certain that the reels I was watching were not from a 1913 or 1915 movie. The film was a fairly modest item, done on a relatively low budget and not starring any actors that would be familiar to most modern viewers. I had seen the actor playing the hero before, however, and I thought he might be Herbert Rawlinson. By the time I finished the film, those were my clues: a medium-budget American film of c. 1917 concerning dime stores and perhaps starring Rawlinson.

My task turned out to be fairly simple. A little research after we returned home confirmed the Rawlinson guess. In preparing the write The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I had seen him in The Coming of Columbus (a 1912 Selig film) and in Damon and Pythias (Universal, 1914).

My next step was to consult the monumental, indispensible reference book, The American Film Institute Catalog. This multi-volume set, many years in the making, was originally published as books. It is now online, but available only to AFI members or through libraries. The catalogues were published by decade—thus obviating the problem of periodization. Each decade gets two volumes, one of entries on all the films, listed in alphabetical order. Credits, production companies, release dates, plot synopses, and other information are included. A second volume indexes the films by chronology, personal names, corporate names, subject, genre, and geography (i.e., where the films were shot).

Until now I had found little use for the subject index, but now it came to my aid. I turned to the Ds to see if there was an entry for dime stores. The AFI indexers were thorough, and sure enough, there was one entry: Like Wildfire. A check of the personal names index under Rawlinson, Herbert revealed that he had acted in a film called Like Wildfire, made in 1917 by Universal. Once I had the title, I checked its catalog entry and found that its plot description matched the film I had seen. Case closed.

Admittedly, in this instance the date wasn’t a crucial clue. Still, determining a film’s year of release can narrow down the possibilities. Thanks as well to the development of classical cutting, a close view of an actor helps in identifying him.

The Best of 1917

DB:

This is the season when everybody makes a list of best pictures. We have stopped playing that game. For one thing, we haven’t seen all the films that deserve to be included. For another, the excellence of a film often dawns gradually, after you’ve had years to reflect on it. And critical tastes are as shifting as the sirocco. Never forget that in 1965 the Cannes palme d’or was won by The Knack . . . and How to Get It.

Still, enough time has elapsed to make us feel confident of this, our list of the best (surviving) films of 1917, both US and “foreign-language.” Titles are in alphabetical order.

The Clown (Denmark, A. W. Sandberg)

Easy Street (U.S., Charles Chaplin)

The Girl from Stormycroft (Sweden, Victor Sjöström)

The Immigrant (U.S., Charles Chaplin)

Judex (France, Louis Feuillade)

The Mysterious Night of the 25th (Sweden, Georg af Klercker)

The Narrow Trail (U.S., Lambert Hillyer)

The Revolutionary (Russia, Yevgenii Bauer)

Romance of the Redwoods (U.S., Cecil B. De Mille)

Terje Vigen (Sweden, Victor Sjöström)

Straight Shooting (US, John Ford)

Thomas Graal’s Best Film (Sweden, Mauritz Stiller)

Wild and Woolly (US, John Emerson)

Next year, maybe we’ll draw up our list for 1918.

(1) For more on this scene and the film as a whole, see Kristin Thompson, “Narration Early in the Transition to Classical Filmmaking: Three Vitagraph Shorts,” Film History 9, 4 (1997), 410-434.

(2) Beyond The Classical Hollywood Cinema, see Kristin’s Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood and Storytelling in the New Hollywood. I’ve talked about these issues in On the History of Film Style, Planet Hong Kong, Figures Traced in Light, The Way Hollywood Tells It, and essays included in Poetics of Cinema. The basics of classical continuity are presented in Chapter 6 of Film Art: An Introduction, and we trace some historical implications of it in Film History: An Introduction.