Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

More light from the East

Useless (Jia Zhang-ke, China, 2007).

DB’s last communiqué from the 2007 Vancouver International Film Festival:

I’m so taken with José Luis Guerin’s En la ciudad de Sylvia (Spain/ France) that I’ll be devoting a separate blog entry to it soon. At Vancouver it was projected with his Unas fotos en la ciudad del Sylvia, a remarkable sketchpad for and rumination on the feature. Rubbed together, the two films throw off sparks. En la ciudad is in color and very tightly constructed, Unas fotos consists of hundreds of black-and-white stills linked by associations and intertitles, with no sound accompaniment. Guerin, an admirer of Murnau, says that as a young man he watched old films in “a sacred silence” and he wanted to try something similar.

Unas fotos may not be factual—call it a lyrical documentary—but it illuminates En la ciudad in striking ways and is intriguing in its own right. Structured as a quest for a woman the narrator met 22 years ago, the film moves across several cities and invokes as its patrons Dante and Petrarch, each of whom yearned for an unattainable woman. But this isn’t exactly a photo-film à la Marker’s La jetée; it uses dissolves, superimpositions, and staggered phases of action to suggest movement. The subjects? Dozens of women photographed in streets and trams. Some will find a creepy edge to the movie, but it didn’t strike me as the obsessions of a stalker. Guerin becomes sort of a paparazzo for non-celebs, capturing the many looks of ordinary women.

Watch this space for more on the many looks of Sylvia. For now, more Asian highlights from Vancouver.

Fujian Blue.

Johnnie To and Wai Ka-fai have reunited for The Mad Detective (Hong Kong), which is as off-balance as you’d expect from its premise. Evidently spun off those TV series that feature telepathic profilers, the film stars Lau Ching-wan as a detective who solves cases by intuiting crooks’ “inner personalities.” We’re introduced to him crawling into a suitcase and asking his partner to throw it downstairs. After a few bumpy descents, he flops out and names the man who packed up a girl’s body the same way. Soon Lau is mentally reenacting a convenience-store robbery, and To/Wai cut together various versions of it as he plays with the possibilities.

Years after Lau leaves the force, his partner brings him back as a consultant to another case. By now, though, our mentalist has gone mental. The filmmakers get comic mileage, and some genuine poignancy, out of intercutting his hallucinations with what’s really happening. Lau envisions multiple personalities within the man they’re hunting, and as he traces out clues each personality flares up. To and Wai carry their dotty premise to a vigorous climax that multiplies the mirror confusions of both Lady from Shanghai and The Longest Nite. The brilliant sound designer Martin Chappell is back on the Milkyway team, making the effects and music magnify Lau’s heroic disintegration.

Lee Chang-dong, of Peppermint Candy and Oasis, has won his widest acclaim yet with Secret Sunshine (Korea). As your basic domestic crime-thriller Born-Again-Christian female-trauma melodrama, it’s undeniably gripping.

Lee Chang-dong, of Peppermint Candy and Oasis, has won his widest acclaim yet with Secret Sunshine (Korea). As your basic domestic crime-thriller Born-Again-Christian female-trauma melodrama, it’s undeniably gripping.

Secret Sunshine earns its 130-minute length, because Lee needs time to do several things. He traces the assimilation of a widow and her little boy into a rural town. Then he must follow the remorseless playing out of a harrowing crime. He makes plausible her succumbing to fundamentalist Christianity and her growing conviction that she needs to forgive the criminal. And there are more changes to come.

For me the most unforgettable moment was the heroine’s appalled confrontation, in a prison visiting room, with the man who wronged her. His unexpected reaction dramatizes how religious faith can cultivate both emotional security and an almost invincible smugness. Jeon Do-yeon won the Best Actress award at Venice for her nuanced performance, and Song Kang-ho, best known for The Host and Memories of Murder, lightens the somber affair playing a man of indomitable cheerfulness and compassion.

I found Brillante Mendoza’s Slingshot (Philippines) quite absorbing. Hopping among various lives lived in the Mandaluyong slums, it’s shot run-and-gun style, but here the loose look seems justified by both production circumstances and aesthetic impact. It was filmed on actual locations across only 11 days, and though it feels improvised, Mendoza claims that it was fully scripted and the actors were rehearsed and their movements blocked. Most of the actors were professionals, intermixed with non-actors—a strategy that has paid off for decades, in Soviet montage films and Italian Neorealism. Slingshot reminded me of Los Olvidados, both in its unsentimental treatment of the poor and its political critique, the latter here carried by the ever-present campaign posters and vans threading through the scenes. I suspect that the final shot, showing an anonymous petty crime accompanied by a crowd singing “How Great Is Our God,” would have had Buñuel smiling.

I found Brillante Mendoza’s Slingshot (Philippines) quite absorbing. Hopping among various lives lived in the Mandaluyong slums, it’s shot run-and-gun style, but here the loose look seems justified by both production circumstances and aesthetic impact. It was filmed on actual locations across only 11 days, and though it feels improvised, Mendoza claims that it was fully scripted and the actors were rehearsed and their movements blocked. Most of the actors were professionals, intermixed with non-actors—a strategy that has paid off for decades, in Soviet montage films and Italian Neorealism. Slingshot reminded me of Los Olvidados, both in its unsentimental treatment of the poor and its political critique, the latter here carried by the ever-present campaign posters and vans threading through the scenes. I suspect that the final shot, showing an anonymous petty crime accompanied by a crowd singing “How Great Is Our God,” would have had Buñuel smiling.

Off to China for Fujian Blue by Robin Weng (Weng Shouming). The setting is the southeastern coast, a jumping-off point for illegal immigration. The plotline has two lightly connected strands. In one, a boys’ gang tries to blackmail straying wives by photographing them with boyfriends, going so far as to sneak in homes and catch the couples sleeping together. The other plot strand presents Dragon, a boy who’s trying to sneak out of China and make money overseas. The whole affair is reminiscent of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Boys from Fengkuei, and in Dragon’s story we can spot overtones of Hou’s distant, dedramatized imagery. Yet Weng adds original touches as well, including an almost subliminal ghost of London across the blue skies of the China straits.

Fujian Blue shared the festival’s Dragons and Tigers Award with Mid-Afternoon Barks (China) by Zhang Yuedong. The two films are very different; if Weng echoes Hou, Zhang channels Tati and Iosseliani. (When I asked him if he knew the directors, he didn’t recognize the names.) Mid-Afternoon Barks is broken into three chapters. In the first, a shepherd abandons his flock and wanders into a village. An unknown man shoots pool. Dogs bark offscreen. The shepherd shares a room with another visitor, but midway through the night, the innkeeper orders them to put up a telegraph pole. When he awakes, the man is gone, and so is the pole. He wanders on.

Fujian Blue shared the festival’s Dragons and Tigers Award with Mid-Afternoon Barks (China) by Zhang Yuedong. The two films are very different; if Weng echoes Hou, Zhang channels Tati and Iosseliani. (When I asked him if he knew the directors, he didn’t recognize the names.) Mid-Afternoon Barks is broken into three chapters. In the first, a shepherd abandons his flock and wanders into a village. An unknown man shoots pool. Dogs bark offscreen. The shepherd shares a room with another visitor, but midway through the night, the innkeeper orders them to put up a telegraph pole. When he awakes, the man is gone, and so is the pole. He wanders on.

In the second episode . . . But why give away any more? In this relaxed, peculiar little film Beckett meets the Buñuel of The Milky Way and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. As the enigmatic men without pasts or even psychologies wound their way through the long shots, Zheng’s quietly comic incongruities won me over long before the last dog had barked and the last ball had bounced.

Jia Zhang-ke is known principally for fiction films like Platform, The World, and Still Life, but from the start of his career he has shown himself a gifted documentarist as well. His In Public (2001) is a subtle experiment in social observation, and Dong (2006) made an enlightening companion piece to Still Life. Useless is more conceptual and loosely structured than Dong. Omitting voice-overs, Useless offers a free fantasia on the theme of China as apparel-house to the world.

The first section of the film presents images of workers in Guangdong factories as they cut, sew, and package garments. Jia’s camera refuses the bumpiness of handheld coverage; it opts for glissando tracking shots along and around endless rows of people bent over machines. (Now that fiction films try to look more like documentaries, one way to innovate in documentaries may involve making them look as polished as fiction films.) Jia also gives us glimpses of workers breaking for lunch and visiting the infirmary for treatment.

In a second section, Useless follows the success of a fashion house called Exception, run by Ma Ke. Her new clothing line Inutile (Useless) consist of handmade coats and pants that are stiff and heavy, almost armor-like, and that flaunt their ties to work and nature. (Some outfits are buried for a while to season.) Ending this part with Ma’s Paris show, in which the models’ faces are daubed with blackface, Jia moves back to China and the industrial wasteland of Fenyang Shaoxi. There he concentrates on home-based spinning and sewing. Neighborhood tailors patch up people’s garments while the locals descend into the coalmines. A former tailor tells us that he gave up his work because large-scale clothes production rendered him useless.

Jia’s juxtaposition of three layers of the Chinese clothes business evokes major aspects of the country’s industry: mass production, efforts toward upmarket branding, and more traditional artisanal work. Without being didactic, he uses associational form to suggest critical contrasts. The miners’ sooty faces recall the Parisian models’ makeup, and their stiff workclothes hanging on a washline evoke the artificially distressed Inutile look. What, the film asks, is useless? Jia shows industrial China’s effort to move ahead on many fronts, while also forcefully reminding us of what is left behind.

Thanks to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Mark Peranson, and all their colleagues for a wonderful festival. They’re so relaxed and amiable, they make it look easy to mount 16 days crammed with movies. Be sure to check on CinemaScope, the vigorous and unpredictable magazine that makes its home in Vancouver. It gives you many gems online, but it’s well worth subscribing to.

Alan Franey, Director of the Vancouver International Film Festival; PoChu AuYeung, Program Manager; and Mark Peranson, Program Associate and Editor of Cinema Scope.

Vancouver visions

Drizzle every day can’t dampen audiences’ enthusiasm.

DB again:

More dispatches from the Vancouver International Film Festival.

“Be pleased, then, you living one, in your delightfully warmed bed, before Lethe’s ice-cold wave will lick your escaping foot.” As a tram destination, Lethe makes a brief appearance in the Swedish film You, the Living, Roy Andersson’s latest comedy of trivial miseries. The line from Goethe is apt. After ninety minutes of drab apartments and Balthus-like figures, all bathed in sickly greenish light, you’re ready to stay in bed forever.

As in Songs from the Second Floor, Andersson gives us a loose network narrative, with barely characterized figures threading their way through urban locales. Long-shot, single-take scenes turn clinics and dining rooms into monumentally desolate spaces. Humans, either bulbous or emaciated, trudge through torrential rain and peer out from distant windows. The bodies may be distorted and careworn, but the spaces are even more so. We get a sort of dystopian Tati, in which gags, near-gags, and anti-gags are swallowed up in the cavities we call home and workplace. A carpet store stretches off into the distance, and a cloakroom seems like a basketball court.

In You, the Living, Andersson’s characters recount their dreams, and these open onto areas only a step beyond our world in their lumpish crowds and eerie vacancy. Judges at a trial are served beer as they condemn the accused. Spectators at an electrocution snack on popcorn from supersized buckets. How can I not like a filmmaker so committed to moving his actors around diagonal spaces, even if the frame is either sparse or uniformly packed, and though he does treat his people like sacks of coal? Don’t look for hope here, only a sardonic eye attracted by banality and pointlessness, images made all the bleaker by an occasional song.

I’m drawn to directors who create a powerful visual and auditory world more or less out of phase with reality as we usually see it (in life and in movies). Andersson is one such director; Jiang Wen is another, whose audacious The Sun Also Rises is one of my favorites of the festival so far. Not doing so well with Mainland Chinese audiences, according to the International Herald Tribune, it hasn’t warmed up a lot of Western critics either. Amazingly, it was declined for competition at Cannes.

It seems impossible to discuss The Sun Also Rises without using the word “magic,” as in magic realism, but I saw it as more of a fairy tale or fable. Set in the Cultural Revolution, it tells two stories in the first two sections. A young boy’s mother goes a little mad on a labor farm; in another village, a teacher is compromised by the passionate love of a nurse and an accusation of sexual misconduct. The two stories intersect in a third section, which leads to a jubilant, if disconcerting, final stretch.

At the center of each plot stands a vivacious, passionate woman who unleashes a cascade of unhappy events. Yet the tone of the film is cheerful, almost giddy, thanks not only to Joe Hisaishi’s buoyant score (he may now be the Nino Rota of Asian cinema) but to Jiang’s fresh, assured technique. The movie starts with tight close-ups—the fish-design shoes the mother wants, her feet and hands, her son’s hands at the abacus—edited at a cracking pace. Staccato movements in and out of the frame give the whole passage a visual snap that launches the movie. Characters lunge through the shots, running this way and that without catching breath, and Jiang’s camera follows them without pausing for the sort of stately scene-setting that audiences may expect. Likewise, the second story opens with hands at play and work, the teacher stroking his guitar strings and a bevy of woman kneading bread dough.

At the center of each plot stands a vivacious, passionate woman who unleashes a cascade of unhappy events. Yet the tone of the film is cheerful, almost giddy, thanks not only to Joe Hisaishi’s buoyant score (he may now be the Nino Rota of Asian cinema) but to Jiang’s fresh, assured technique. The movie starts with tight close-ups—the fish-design shoes the mother wants, her feet and hands, her son’s hands at the abacus—edited at a cracking pace. Staccato movements in and out of the frame give the whole passage a visual snap that launches the movie. Characters lunge through the shots, running this way and that without catching breath, and Jiang’s camera follows them without pausing for the sort of stately scene-setting that audiences may expect. Likewise, the second story opens with hands at play and work, the teacher stroking his guitar strings and a bevy of woman kneading bread dough.

The exuberance of the characters and the style contrasts with the usual presentation of this cruel era of PRC history. Jiang finds real pleasure in Cultural Revolution kitsch, and he links a snapshot of the missing father to an iconic image from The Red Detachment of Women. It’s another knot joining the two plot strands; in the second section, villagers watch a screening of that film. Jiang makes the event a real festivity, with couples courting, the teacher humming along with the tunes, and an old lady feeding fish in a pond. Jiang dares to suggest that the force-fed popular culture of Maoism, so scoffed at now, gave genuine enjoyment

The fairy-tale atmosphere is conjured up by little mysteries, such as a talking bird and the possibility of taking dictation on an abacus, and bigger ones about fatherhood, a stone hut in the forest, and a shadowy figure named Alyosha, whose identity is more or less revealed in the film’s final long sequence. Variety‘s Derek Elley found The Sun Also Rises both rushed and dawdling, but you could say that about 8 ½ too. Like Fellini’s film, Jiang’s shows a filmmaker at the top of his powers inviting us to savor the exhilarating attractions of imagination.

Another world, another vision. The camera frames a rope descending into black water and tilts slowly, really slowly, up to reveal the ship’s prow and the deck, swathed in darkness. Two silhouettes are visible, and one says, “Don’t follow me too soon.” Soon we’re following the transfer of a small suitcase, the disembarking of passengers making their way to a train. This nearly thirteen-minute shot (!) gives way to another long take, in which we see, in the distance, a murder on the quay.

Béla Tarr has called The Man from London a film noir, and he explained that to me by saying, “Not an American film noir. They were done by bad directors. More like the original French film noirs.” Indeed, the opening shot, with its mists and murky waterfront, suggests Quai des brumes. But here the plot action is slight, presented at a distance, and opaque in its motives; 10 % story, we might say, but 90 % atmosphere. The camera coasts across the waterfront town with the same grave deliberation we see in Damnation, Sátántangó, and Werckmeister Harmonies, swallowing up the Simenon situation in Tarr’s fluid way of seeing, a scanning of ever-shifting surfaces and vistas.

With fewer than thirty shots across about 133 minutes, The Man from London is another exercise in long-take virtuosity, but I thought I noticed some fresh departures. For one thing, there are few characters and relatively few locales, and situations are brought out with unusual explicitness (for Tarr). Instead, it seemed to me that Tarr was exploring new possibilities in one of his pet techniques, the over-the-shoulder long shot I mentioned in an earlier entry.

The opening shot, at first an apparently objective survey of the moored ship, turns out to be a view from the tower manned by Maloin. In shooting the wharf, the camera is forever oscillating, within a single shot, between what we can see outside, at a distance, from a high angle, and glimpses of Maloin at his post, his head or shoulder sliding into the foreground. Imagine Rear Window without the reverse shots of Jimmy Stewart watching.

In earlier films, Tarr tended to be quite clear when his foreground character was noticing something in the distance; his chief interest lay in suppressing the character’s reaction. What we get here can be seen as a refinement of the opening shot of Damnation, with its awesome landscape gradually reframed by Karrer looking out his window, or of passages of the doctor at his window in Sótántangó. Several of the tower scenes in The Man from London, are elaborations of that image scheme, but with more ambiguity. The camera, slipping from long-shot background and close-up foreground, coasts along without telling us whether Maloin has seen exactly what we’ve seen. The result is a suspenseful uncertainty not only about what’s happening in the noir plot but also about what Maloin knows.

There are many other points of interest in the new film, and after one viewing I can’t claim to have a grip on them. But I do think critics have overlooked its sheer visual beauty and Tarr’s efforts to turn his style toward a fluid pictorial suspense.

Altogether less flamboyant than any of these was Suo Masayuki’s I Just Didn’t Do It (Japan), which I’d been looking forward to since my February entry. It’s definitely a change of pace for a director known for comedies that satirize youth culture and middle-aged boredom. A young man is accused of groping a schoolgirl on a crowded traincar. The police advise him to confess and pay a fine, but he insists on his innocence. This decision drops him into a judicial mill that grinds slow and altogether too fine.

The script carpentry seems to me excellent. The presentation of each phase of the boy’s case could have been dry, but Suo makes each step hinge on a detail of fact or inference, so small questions keep popping up—including questions about whether the boy really might have done it. The finale, which recalls Kurosawa’s Ikiru in its methodical summing up of everything we have seen, becomes grueling, but in a salutary way. In Japan, the film is a trailblazing critique of the criminal justice system, where most people arrested confess in order to avoid the almost inevitable guilty verdict in a trial. Eliminating a jury, barring defense counsel’s discovery of prosecution evidence, and capriciously replacing one judge by another midway through a case, the system encourages cynical submission.

Suo avoids stylistic pyrotechnics. He plays down his signature mugshot framings (the publicity still above is an exception) and has recourse to handheld camerawork simply to distinguish the train scenes from the rest of the film. Still, his shooting displays a quiet agility. The high point is probably the testimony of the schoolgirl, her identity protected by screens set up around her. Suo finds a remarkable variety of camera setups here, each well-judged to impart a particular piece of information. (In its resourceful changes of viewpoint, the sequence reminded me of Mizoguchi’s courtroom scenes in Taki no Shiraito and Victory of Women.) The title suggests a strident social-problem film, but Suo’s calm plainness of handling yields a quality rare in the genre: tact.

Many more films to report on, including Johnnie To’s latest, but I must rush off to—what else?—another movie. I’ll try for a wrapup on Thursday, while I’m on that highway in the sky.

The critics line up: Bérénice Reynaud, Shelly Kraicer, Chuck Stephens, and Tony Rayns.

The sarcastic laments of Béla Tarr

Werckmeister Harmonies.

DB here:

Last weekend, Facets MultiMedia in Chicago held a tribute to Béla Tarr. Milos Stehlik and his colleagues have been long-time champions of Tarr’s work, holding retrospectives and releasing nearly all his features on DVD (with Sátántangó soon to come). Tarr arrived on Saturday, but an emergency sent him back to Hungary sooner than he expected. So instead of discussing his work with a panel, he could only introduce the screening of Werckmeister Harmonies before running off to the airport.

The panel went ahead, with Jonathan Rosenbaum, Scott Foundas, and me chatting with Susan Doll of Facets. It wasn’t as pungent a session as it would have been with Tarr there, but I thought it was still pretty interesting. Jonathan, Scott, and Susan had thoughtful comments, and the questions from the audience were exceptionally good. The whole session was recorded for an online broadcast at some point, so you might want to watch out for that. And I have earlier blog entries on Sátántangó here and here.

In preparation for the panel I spent last week reconsidering Tarr’s work, so I offer a few notions about his films and how we might place them in the history of cinematic form and style. Some of these remarks build on things I said at the session.

Up close and personal

Some directors accommodate critics, accepting or at least tolerating writers’ efforts to probe the work. Not Tarr. Ask about his plots and characters, and he claims that he doesn’t tell stories. Point out what seem allegorical or symbolic touches, and he protests that he doesn’t make allegories and he hates symbols. Mention contemporary cinema, and the reply is abrupt: “For me, when I see something at the cinema it is always full of shit.” And if you tell him that his early films seem quite different from his more recent ones, he vehemently disagrees.

Some directors accommodate critics, accepting or at least tolerating writers’ efforts to probe the work. Not Tarr. Ask about his plots and characters, and he claims that he doesn’t tell stories. Point out what seem allegorical or symbolic touches, and he protests that he doesn’t make allegories and he hates symbols. Mention contemporary cinema, and the reply is abrupt: “For me, when I see something at the cinema it is always full of shit.” And if you tell him that his early films seem quite different from his more recent ones, he vehemently disagrees.

As Scott pointed out in our panel, though, it can be plausible to apply the concept of “period” to filmmakers’ work as we do to painters’ careers. Lars von Trier has been fairly explicit that after mastering a polished style for his work up through Zentropa/ Europa he wanted to try something new, and with The Kingdom he shifted toward a looser, on-the-fly style that pointed toward Dogme 95. Any viewer can be forgiven for thinking that Tarr has moved in the opposite direction of von Trier, from a pseudo-documentary approach toward something much more grave and majestic.

The first three theatrical features focus on the urban working class and their struggles to improve their lot. In Family Nest (1979), a family who can’t afford a flat of their own squeezes in with the husband’s parents. The tight quarters, the ceaseless complaints of the father-in-law, and the husband’s inertia force his wife and child to flee to the streets. The Outsider (1981) follows a young violinist as he drifts among jobs and into a passive marriage before being called up for military service. The family in The Prefab People (1982) has a flat and a decent job, but the wife finds the husband indifferent to her boring routines, and he looks for an escape in a job in another town. The concentration on ordinary people’s lives and the search for drama in the everyday dissatisfactions of city life put the films in the neorealist line of succession.

Stylistically, the films are stripped down in ways that also owe debts to modern traditions. Shot mostly handheld, adjusting the framing to the actors’ performances, they belong to a strain of films from the 1960s on that sought to suggest the immediacy of cinéma-vérité documentary. Unlike many such films, however, Tarr’s buy into a long-take aesthetic. Perhaps surprisingly, these movies’ shots run abnormally long: an average shot length of 32 seconds for Family Nest, 33.5 for The Outsider, 47 seconds for Prefab People. By comparison, Hollywood films of these years were consistently running between 4 and 8 seconds per shot, and comparatively few European and Asian films rely on shots as lengthy as Tarr’s.

Most scenes in these three films are dialogues, and the camera holds intently, if shakily, on faces. This concentration is enhanced by the general absence of establishing shots. A scene opens more or less in the middle of a conversation, and we get a character already challenging another. The visual pattern is that of shot/ reverse-shot, and in most scenes the first face is counterposed to a second one by either a cut or a pan. Shooting on location in cramped rooms, Tarr makes his framings tight; in Family Nest, the jammed frames give us and the characters almost no breathing space.

By relying on more or less isolated faces in close-ups, Tarr can absorb us in the intimate drama while sometimes catching us off guard. For instance, when we get a single character without an establishing shot, there is often a momentary uncertainty about where we are, or when the action is taking place. We also can’t be sure of who’s present besides the speaker, so the close view of him or her leaves us hanging: To whom is s/he talking? We’re pushed to pay close attention to what the character is saying, looking for any clues to the dramatic context. Tarr’s tactic also delays the reaction of the listener; he may withhold sight of the conversational partner until s/he speaks. The effect, heightened by the lengthy takes, is to turn many of these scenes into monologues, in which a character pours out his or her reaction to a situation, and we’re forced to take that in more or less pure form.

By the end of Family Nest, Tarr is shooting entire scenes concentrated on a single face, and because we don’t know if there is anyone else present, we have to take the talk as virtually a soliloquy.

It’s as if Tarr invoked the stylistic schema of shot/ reverse shot and simply postponed or suppressed the reverse shot, leaving only an inexpressive shoulder in the foreground, if that. I’ve discussed the delayed reverse-shot as a convention of European cinema in an earlier blog, and Tarr makes ingenious use of it.

Tarr builds these films out of conversational blocks, punctuated by undramatic routines. The result is that often major plot actions take place offscreen, or rather in between the dialogues. Exposition that other filmmakers would give us up front is long delayed, with bits of information sprinkled through the entire film. In Family Nest, the father claims that he’s seen Iren having an affair with another man. We can’t be sure he’s lying because we haven’t strayed enough out of the household to judge her activities. In The Outsider, one scene ends with the drifter Andras telling Kata, a woman he has recently met, that he has a child by another woman. The scene ends with him smiling in indifference, leaving his sentence unfinished. In the next scene, a band strikes up a tune: Andras and Kata are celebrating their marriage.

Most filmmakers would show us more of the courtship and a scene of proposal, but Tarr moves directly to the next block, suggesting Andras’ laid-back heedlessness. Agreeing to get married is no big deal. Further, by skipping over the most obviously dramatic incidents, Tarr’s storytelling joins that tradition of ellipsis celebrated by André Bazin in his essays on neorealism. No longer does the filmmaker have to show us every link in the causal chain, and no longer are some scenes peaks and others valleys. By deleting the obviously dramatic moments, the filmmaker forces us to concentrate on more mundane preambles and consequences.

This block construction yields an unusually objective narration. These films lack voice-overs, subjective flashbacks, dreams, and other tactics of psychological penetration. We have to watch the people from the outside, appraising them by what they say and do. It is a behavioral cinema. True, Prefab People opens with a flashback: The husband is packing to leave his wife, and the plot moves back to an anniversary dinner that ends badly. But the flashback to the earlier phase of the marriage isn’t framed as the wife’s memory. When the plot’s chronology brings us back to the moment of the husband’s departure, the replay of the opening allows us to watch the characters with more knowledge of what is driving them apart. Unsurprisingly if you know Tarr’s earlier films, that replay is followed by a long monologue showing the wife expressing her sorrow at his departure, without any visual cues about who, if anyone, is listening.

Then, without preparation, we see the couple back together, shopping in an appliance store. How did they reconcile? Have their attitudes changed, or are they simply reconciled to their old life? Like Antonioni and many other modern filmmakers, Tarr doesn’t tell us such things. He simply ends his film on a long take of husband and wife riding expressionless in the back of a truck, as much pieces of cargo as the washing machine beside them.

After the Fall

The second-phase films do look and feel rather different. Almanac of Fall (1984), a story of duplicity and spite among people sponging off a well-to-do older woman, offers a wholly elegant mise-en-scene. Characters are often framed from far back, surroundings take on much more importance, the framing is stable—often with windows, doors, and furnishings impeding our view of the action—and the camera moves smoothly, often in arcs around stationary figures. The takes are even longer, averaging just under a minute. The rococo lighting (patches of color seem to follow actors around) and atmosphere of strained upper-class narcissism seem like quite a break from the working-class films. If I had to find an analogy to Almanac of Fall, it would be Fassbinder’s Chinese Roulette (1976), with its camera arabesques and slightly decadent ostentation.

The overripe shots of Almanac of Fall signaled a shift toward a self-consciously formal cinema, but then Tarr stripped his settings and cinematography down. From Damnation (1988) onward, his films feature ruined exteriors, shabby interiors, elaborate chiaroscuro, rhythmic camera movement, and very long takes. (Damnation has an ASL of 2 minutes; Sátántangó, 2 minutes 33 seconds; Werckmeister Harmonies, 3 minutes 48 seconds).

Tarr insisted in conversation with me that there isn’t a sharp break between early and late styles. For one thing, his video piece Macbeth (1982) consists of only two shots across 63 minutes. It was made before The Prefab People, so his shift toward the ambulatory long take was already in the works. Moreover, The Outsider ends with a strained restaurant encounter captured in a virtuoso handheld shot running nearly seven minutes. A nightclub scene in The Prefab People likewise features some sidewinding long takes around a dance floor that wouldn’t be out of place, at least in their repetitive geometry, in Damnation.

If we’re inclined to look for other continuities, we can find them. In the films from Damnation onward, the deferred reverse shot has been put at the service of attached point of view, so that often when Tarr’s protagonists peer around a corner or out of a window, instead of optical pov cutting we have an over-the-shoulder view that conceals their facial reaction. One scene in Damnation starts as a typically Tarrian scrutiny of texture, with the wrinkling wall echoing Karrer’s topcoat. But then the camera arcs and refocuses, showing what Karrer is watching but not how he responds.

The blocklike construction of scenes in the early films carries on in the later work, but now Tarr minimizes the cuts within a scene, so that it becomes an even more massive hunk of space and time. Tarr refuses as well to use crosscutting, which would show us various characters pursuing their activities at roughly the same time—another strategy that keeps us fastened to one relentlessly unfolding chain of actions and, usually, one character’s range of knowledge. The avoidance of crosscutting will have major structural implications in Sátántangó, which overlaps characters’ individual points of view by replaying certain events and stretches of time.

The long-held facial shots of the early films don’t create a natural arc; the shot will go on as long as the character wants to talk. Similarly, many long takes in the later films don’t present a beginning-middle-end structure. We simply follow a character walking toward or away from us, pushing into a stretch of time whose end isn’t signaled in any way. This becomes especially clear in those extended long shots in which a character walks away toward the horizon and the camera stays put. Traditionally, that signals an end to the scene, but Tarr holds the image, forcing us to watch the character shrink in the distance, until you think that you’ll be waiting forever. Likewise, the diabolical dance shots of Sátántangó, built on a wheezing accordion melody that seems to loop endlessly, are exhausting because no visual rhetoric, such as a track in or out, signals how and when they might conclude. Early and late, Tarr won’t hold out the promise of a visual climax to the shot, as Angelopoulos does; time need not have a stop.

Nonetheless, I do agree with my fellow panelists that the later films have a significantly different look and feel, and it’s on them that Tarr’s place in world film history will chiefly rest. As I indicated at the end of Figures Traced in Light, he stands out as a distinctive creator in a contemporary tradition of ensemble staging. Like Tarkovsky, he shifts our attention from human action toward the touch and smells of the physical world. Like Antonioni and Angelopoulos, he employs “dead time” and landscapes to create a palpable sense of duration and distance. Like Sokurov in Whispering Pages (1993), he takes us into an eerie, Dostoevskian realm where characters are cruel, possessed, mesmerized, humiliated, and prey to false prophets.

Ties to tradition

Tarr, however, maintains that his work, early or late, owes little to cinema. He claims not to have been influenced by other directors, and he asserts that he gets his ideas from life, not from films. When pressed, he admits that he knew the films of Miklós Jancsó “and I liked them very much. But I think what he does is absolutely different from what we do.”

It’s not uncommon for strong creators to reject the idea of influence, and many feel that they may sap their originality if they’re exposed to other work. Still, nothing comes from nothing. Any artwork is linked to others through an expanding network of affinity and obligation. Often influence is like influenza; you catch it unawares, despite your efforts to ward it off. And sometimes artists on their own find strategies that other artists have already or simultaneously hit upon.

Whether or not Tarr consciously joined a tradition, his practices do link him to several trends. Tarr has rejected the idea, floated by Jonathan, that his early films are indebted to Cassavetes, but there seems little doubt that by 1979, when Family Nest was released, it contributed to the fictional-vérité tradition, regardless of his intent. Likewise, his late films’ reliance on long takes is part of a broader tendency in European cinema after World War II. The neorealists taught us that you could make a film about a character walking through a city (The Bicycle Thieves, Germany Year Zero), and other directors, such as Resnais in the second half of Hiroshima mon Amour, developed this device. With Antonioni, Dwight Macdonald noted, “the talkies became the walkies.” Jancsó took Antonioni further (acknowledging the influence) in the endless striding and circling figures of The Round-Up, Silence and Cry, and The Red and the White. So even if there wasn’t any direct influence, Antonioni and Jancsó paved the way for Tarr; they made such walkathons as Sátántangó and Werckmeister thinkable as legitimate cinema.

Still more broadly, as Hollywood cinema has become faster-paced, accelerating its action and cutting, art cinema in Asia and Europe has tended toward ever slower rhythms. Visit any festival today, as Scott mentioned in our panel, and you’ll see plenty of films with long takes and fairly static staging. I criticize this fashion a bit in Figures, but it’s undeniably a major option on today’s menu. It’s even been picked up in contemporary American indies, with Gus Van Sant’s work from Elephant on offering prominent examples. He, of course, has been crucially influenced by Tarr, but Hou, Tsai Ming-liang, Sokurov, and other directors haven’t. We seem to have a case of stylistic convergence, with Tarr choosing to explore the long take at the same time others were doing so.

Within recent Hungarian cinema, it would be fruitful to examine Tarr’s relation to his contemporaries. Janós Szasz’s Woyzeck (1994) takes place in a wasteland not unlike those of Damnation and Sátántangó. Even closer to Tarr is the work of György Fehér. I’ve seen only Passion (1998; right) and one scene from Twilight (1990). Here again we get very long takes with a supple camera, grungy settings, and down-at-heel characters wandering in rain and mist or dancing as if possessed by demons. Fehér has worked with Tarr as producer, dialogue writer, and “consultant.” We could also explore Tarr and Fehér’s affinities with Benedek Flieghauf, the younger director of The Forest (2003) and Dealer (2004). Fleghauf builds these films around extensive long takes, and the remarkable Forest carries the idea of the suppressed reverse-shot to an eerie extreme, as characters study mysterious offscreen objects that may never be shown us.

Within recent Hungarian cinema, it would be fruitful to examine Tarr’s relation to his contemporaries. Janós Szasz’s Woyzeck (1994) takes place in a wasteland not unlike those of Damnation and Sátántangó. Even closer to Tarr is the work of György Fehér. I’ve seen only Passion (1998; right) and one scene from Twilight (1990). Here again we get very long takes with a supple camera, grungy settings, and down-at-heel characters wandering in rain and mist or dancing as if possessed by demons. Fehér has worked with Tarr as producer, dialogue writer, and “consultant.” We could also explore Tarr and Fehér’s affinities with Benedek Flieghauf, the younger director of The Forest (2003) and Dealer (2004). Fleghauf builds these films around extensive long takes, and the remarkable Forest carries the idea of the suppressed reverse-shot to an eerie extreme, as characters study mysterious offscreen objects that may never be shown us.

More generally, and more speculatively, we could look to a wider movement in late and post-Soviet art toward mournfulness and lamentation in response to cultural collapse. Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia is one instance, but Larissa Shepitko’s The Ascent (1976) and Elem Klimov’s Come and See (1985) point in this direction too. Vitaly Kanevsky’s Freeze, Die, Come to Life! (1989) offers a rusting, dilapidated world not far from Tarr’s. In the 1970s and 1980s, composers like Arvo Pärt, Henryk Górecki, Giya Kancheli, Vyacheslav Artyomov, and Valentin Silvestrov created austere, threnodic music that sometimes evokes spirituality but just as often suggests a bleak end to everything. The very titles—Symphony of Sorrowful Songs (Górecki), Symphony of Elegies (Artyomov), Postludium (Silvestrov)—evoke something more than the death rattle of Communism. The pieces can be heard as meditations on the ruins of modern history, asking what humankind has accomplished and what can come next. Tarr’s severe parables, grotesque and sarcastic in the manner of Kafka, don’t exude the religiosity we can find in some of this music or filmmaking, but, at least for me, they share the impulse to lament humans’ inability to transcend their brutish ways. “I just think about the quality of human life,” he remarks, “and when I say ‘shit’ I think I’m very close to it.”

I have more ideas about Tarr, especially on Sátántangó and Werckmeister, but I have to stop somewhere. I hope to see his new film The Man from London when I go to the Vancouver International Film Festival next week, and of course I’ll report on it here.

The best piece of writing I know on Tarr’s cinema is András Bálint Kovács’ “The World According to Tarr,” in the catalogue Béla Tarr (Budapest: Filmunio, 2001).

Béla mesmerizes Lola, Chicago 15 September 2007.

Thanks to Milos Stehlik, Susan Doll, Charles Coleman, and Megan Rafferty of Facets, to Béla Tarr for generous conversation, and to András Kovács for enlightening discussions over the years.

PS 20 September: The reports of Tarr’s earlier visit to Minneapolis are emerging; here’s a good link.

[insert your favorite Bourne pun here]

DB here:

You may be tired of hearing about The Bourne Ultimatum, but the world isn’t.

It’s leading in the international market ($52 million as of 29 August) and has yet to open in thirty territories. It’s expected, as per this Variety story, to surpass the overseas total of $112 for the previous installment, The Bourne Supremacy. According to boxofficemojo.com, worldwide theatrical grosses for the trilogy are at $721 million and counting. Add in DVD and other ancillaries, and we have what’s likely to be a $2-$3 billion franchise.

There’s every reason to believe that the success of the series, plus the critical buzz surrounding the third installment, will encourage others to imitate Paul Greengrass’s run-and-gun style. In an earlier blog, I tried to show that despite Greengrass’s claims and those of critics:

(1) The style isn’t original or unique. It’s a familiar approach to filmmaking on display in many theatrical releases and in plenty of television. The run-and-gun look is one option within today’s dominant Hollywood style, intensified continuity.

(2) The style achieves its effect through particular techniques, chiefly camerawork, editing, and sound.

(3) The style isn’t best justified as being a reflection of Jason Bourne’s momentary mental states (desperation, panic) or his longer-term mental state (amnesia).

(4) In this case the style achieves a visceral impact, but at the cost of coherence and spatial orientation. It may also serve to hide plot holes and make preposterous stunts seem less so.

I got so many emails and Web responses, both pro and con, that I began to worry. Did I do Ultimatum an injustice? So I decided to look into things a little more. I rewatched The Bourne Identity, directed by Doug Liman, and Greengrass’s The Bourne Supremacy on DVD and rewatched Ultimatum in my local multiplex. My opinions have remained unchanged, but that’s not a good reason to write this followup. I found that looking at all three films together taught me new things and let me nuance some earlier ideas. What follows is the result.

For the record: I never said that I got dizzy or nauseated. The blog entry did, however, try to speculate on why Greengrass’s choices made some viewers feel queasy. Some of those unfortunates registered their experiences at Roger Ebert’s site. For further info, check Jim Emerson’s update on one guy who became an unwilling receptacle.

Another disclaimer: For any movie, I prefer to sit close to the screen. In many theatres, that means the front row, but in today’s multiplexes sitting in the front row forces me to tip back my head for 134 minutes. So then I prefer the third or fourth row, center. From such vantages I’ve watched recent shakycam classics like Breaking the Waves and Dogville, as well as lesser-known handheld items like Julie Delpy’s Looking for Jimmy. My first viewing of Ultimatum was from the fifth row, my second from the third. (1)

Finally: There are spoilers ahead, pertaining to all three films.

How original?

Someone who didn’t like the films would claim that they’re almost comically clichéd. We get titles announcing “Moscow, Russia” and “Paris, France.” You can poke fun at lines of dialogue like “What connects the dots?” and “You better get yourself a good lawyer” and the old standby “What are you doing here?” But these are easy to forgive. Good films can have clunky dialogue, and you don’t expect Oscar Wilde backchat in an action movie.

More significantly, all three films are quite conventionally plotted. We have our old friend the amnesiac hero who must search for his identity. Neatly, the word bourne means a goal or destination. It also means a boundary, such as the line between two fields of crops–just as our hero is caught between everyday civil law and the extralegal machinery of espionage.

The film’s plot consists of a series of steps in the hero’s quest. Each major chunk yields a clue, usually a physical token, that leads to the next step. Add in blocking figures to create delays, a hierarchy of villains (from swarthy and unshaven snipers to jowly, white-haired bureaucrats), a few helpers (principally Nicky and Pam), and a string of deadlines, and you have the ingredients of each film. (Elsewhere on this site I talk about action plotting.) The last two entries in the series are pretty dour pictures as well; the loss of Franka Potente eliminates the occasional light touch that enlivened Bourne Identity right up to her nifty final line

All three films rely on crosscutting Bourne’s quest with the CIA’s efforts to find him, usually just one step behind. Within that structure most scenes feature stalking, pursuits, and fights. In the context of film history, this reliance on crosscutting and chases is a very old strategy, going back to the 1910s; it yields one of the most venerable pleasures of cinematic storytelling.

Mixed into the films is another long-standing device, the protagonist plagued by a nagging suppressed memory. Developing in tandem with the external action, the fragmentary flashbacks tease us and him until at a climactic moment we learn the source: in Supremacy, Bourne’s murder of a Russian couple; in Ultimatum, his first kill and his recognition of how he came to be an assassin. The device of gradually filling in the central trauma goes back to film noir, I think, and provides the central mysteries in Hitchcock’s Spellbound and Marnie.

By suggesting that the films are conventional, I don’t mean to insult them. I agree with David Koepp, screenwriter of Jurassic Park and Carlito’s Way, who remarks:

There are rules and expectations of each genre, which is nice because you can go in and consciously meet them, or upend them, and we like it either way. Upend our expectations and we love it—though it’s harder—or meet them and we’re cool with it because that’s all we really wanted that night at the movies anyway. (2)

There can be genuine fun in seeing the conventions replayed once more.

The series makes some original use of recurring motifs, the most obvious being water. The first shot of the first film shows Jason floating underwater; in the second film he bids farewell to the drowned Marie underwater; and in the last shot of no. 3, we see him submerged in the East River, closing the loop, as if the entire series were ready to start again. There’s also a weird parallel-universe moment when Pam tells Jason his real name and birthdate. She does it in 2, and then, as if she hasn’t done it before, tells him again in 3, in what seem to be exactly the same words. In 3, though, it has a fresh significance as a coded message, and a new corps of CIA staff is listening in, so probably the second occurrence is a deliberate harking-back. Or maybe Bourne’s amnesia has set in again. [Note of 9 Sept: Oops! Something that’s going on here is more interesting than I thought. See this later entry.]

The look of the movies

The big arguments about Ultimatum center on visual style. The filmmakers and some critics, notably Anne Thompson, have presented the style as a breakthrough. But again, the movie is more traditional than it might first appear.

In a film of physical action, the audience needs to be firmly oriented to the space and the people present. The usual tactic is to present transitional shots showing people entering or leaving the arena of action. What might be filler material in a comedy or drama—characters driving up, getting out of their vehicles, striding along the pavement, entering the building—is necessary groundwork in an action sequence. So we see Bourne arriving on the scene, then his adversaries arriving and deploying themselves, in the alternation pattern typical of crosscutting. Surprisingly, for all the claims made about the originality of Greengrass’s style in 2 and 3, he is careful to follow tradition and give us lots of shots of people coming and going, setting up the arena of confrontation.

Then the director’s job is just beginning. Traditionally, once the scene gets going, the positions and movement of the figures in the action arena should be clearly maintained. Likewise, it’s considered sturdy craftsmanship to delineate the overall space of the scene and quietly prepare the audience for key areas—possible exits, hiding places, relations among landmarks. (See this entry for how one modern director primes spaces in an action scene.) I claimed in the earlier entry that such basic orienting tasks aren’t handled cogently in Ultimatum, and a second viewing of the scene in Waterloo Station and the chase across the Tangier rooftops hasn’t made me change that opinion. Later I’ll discuss how Greengrass and some commentators have defended the loss of orientation in such scenes.

All the films in the trilogy employ traditional strategies of setting up the action sequences, but the series displays an interesting stylistic progression. In Identity, Liman gives us mostly stable framings and reserves handheld bits for moments of tension and point-of-view shots. He saves his fastest cutting for fights and chases.

Supremacy displays a more mixed style. It contains passages of wobbly, decentered framing, but those exist alongside more traditionally shot scenes—stable framing, with smooth lateral dollying and standard establishing shots. There are some aggressive cuts, as in the crisp emphasis on the sniper at the start of the first pursuit, but on the whole the editing isn’t more jarring than usual these days. We also get, as I mentioned in the earlier entry, some almost willfully obscure over-the-shoulder shots, and occasionally we get the eye-in-the-corner technique that would become more prominent in Ultimatum.

As we’d expect, in Supremacy the bounciest camerawork and choppiest editing are found in the sequences of the most energetic physical action. Most of the surveillance scenes get a little bumpy, while the chases are wilder. The most extreme instance, I think, is the very last chase in the tunnel, when Bourne avenges the death of Marie and slams the sniper’s vehicle into an abutment. As in Identity, Supremacy arrays its technique along a continuum, saving the most visceral techniques for the most brusing action sequences.

So Ultimatum raises the stakes by applying the run-and-gun style more in a more thoroughgoing way. Everything is dialed up a notch. The flashbacks are more expressionistic than those of Supremacy: instead of dark hallucinations we get blinding, bleached-out glimpses of torture and execution, in staggered and smeared stop-frames. The conversation scenes are bumpier and more disjointed; the cat-and-mouse trailings are more disorienting, with jerky zooms and distracted framings; the full-bore action scenes are even more elliptical and defocused. It’s as if the visual texture of Supremacy’s tunnel chase has become the touchstone for the whole movie.

That texture I tried to describe in the earlier entry. Greengrass relies on camerawork, cutting, and sound to convey the visceral impact of action, rather than showing the action itself. The most idiosyncratic choices include framing that drifts away from the subject of the shot, oddly offcenter compositions, and a rate of cutting that masks rather than reveals the overall arc of the action. Some critics have liked the film’s technique, some have hated it, but I think my account stands as a fair account of the destabilizing tactics on the screen, and a likely source of some spectators’ vertigo.

Run-and-gun, with a gun

The style of Ultimatum is a version of what filmmakers call run-and-gun: shot-snatching in a pseudo-documentary manner. This approach has a long history in American film. The bumpy handheld camera, I tried to show in The Way Hollywood Tells It, has been repeatedly rediscovered, and every time it’s declared brand new. I have to admit I’m startled that critics, who probably have seen Body and Soul, A Hard Day’s Night, The War Game, Seven Days in May, or Medium Cool, continue to hail it as an innovation. Today it’s a standard resource for fictional filmmaking, to be used well or badly.

What’s at issue here are the role it plays and the effects it achieves. In Lars von Trier’s The Idiots, I’d argue that handheld work becomes genuinely disorienting because the camera is scanning the scene spontaneously to grab what emerges. But von Trier’s roaming camera yields rather long takes compared to what we find in the Bourne series. Greengrass is practicing what I called, in Film Art and The Way Hollywood Tells It, intensified continuity.

This approach breaks down a scene so that each shot yields one, fairly straightforward piece of information. The hero arrives at the station. Car pulls up; cut to him getting out; cut to him walking in. Traditional rules of continuity—matching screen direction, eyelines, overall positions in the set—are still obeyed, but the dialogue or physical action tends to be pulverized into dozens of shots, each one telling us one simple thing, or simply reiterating what a previous shot has shown. (Oddly, sometimes intensified continuity seems more, rather than less, redundant than traditional continuity cutting.)

Within the intensified continuity approach, we can find considerable variation. I argued that one highly mannered version can be found in Tony Scott’s later work, where the shots are fragmented to near-illegibility and treated as decorative bits. You can find Scott’s signature look tawdry and overwrought, but Liman and Greengrass belong in the same tradition. All three directors rely on telephoto lenses, for example, and they have recourse to well-proven techniques for rendering hallucinatory states of mind, as in these multiple-exposure shots, one from Man on Fire and the second from Bourne Supremacy.

Despite the stylistic differences among the three Bourne films, the basic one-point-per-shot premises remain in place. Here’s a passage from Supremacy. Jason gets off the train in Moscow. We get an establishing shot of the station as the train pulls in, followed by a shot of him getting off, moving left to right. The establishing shot is a smooth craning movement down, but the following shot is a little shaky.

Then we get a blurry shot of him walking, taken with a very long lens. A head-on shot like this traditionally creates a transition allowing the filmmaker to cross the axis of action, letting Jason walk right to left in the next shot.

Cut to closer view: Jason turns his head slightly. Cut to what he sees, in a shaky pov: Cops.

The answering handheld shot shows Jason reacting. As he strides on purposefully, a still closer shot accentuates his eye movement and adds a beat of tension.

Jason turns and goes to the pay phones, followed by the unsteadicam, then turns his head watchfully. A smooth match-on-action cut brings us closer.

But then Jason turns back to his task, and suddenly a passerby blots out the frame.

When the frame clears, a jouncy shot shows Jason’s hands thumbing a phone book. This might be a continuation of the same shot, or the result of a hidden cut. I suggest in The Way Hollywood Tells It that such stratagems are common in intensified continuity: blotting out the frame, flashing strobe lights, and other devices can create a pulsating rhythm akin to that of cutting. Jason turns the pages, and a jump cut shows him on another page.

Cut back to him scanning the pages. He writes down an address, in a very shaky framing.

Cut back again to Jason, and another smooth match-on action brings us back to the slightly fuller framing we’ve seen already. Greengrass shoots with at least two cameras simultaneously, which can facilitate match-cutting like this.

Jason strides toward us, going out of focus. Then a stable long shot pans with him, moving left as before. He leaves the station.

A very simple piece of action has been broken into many shots, some of them restating what we’ve already seen. In the days of classic studio filming, most directors wouldn’t have given us so many shots of Bourne leaving the train platform; a single tracking shot would have done the trick. A single shot could have shown us Jason at the phone, scribbling down the address. As a result, the whole passage is cut faster than in the classic era. The sequence lasts only forty-one seconds but shows sixteen shots. Two to three seconds per shot is a common overall average for an action picture today. The rapid cutting helps create that bustle that Hollywood values in all its genres.

It’s clear, I think, that here the run-and-gun technique is laid over the premises of intensified continuity, letting each shot isolate a bit of narrative information to make sure we understand, even at the risk of reiterating some bits. Jason has arrived in Moscow, he has to be careful because cops are everywhere, now he needs an address, he finds it, he’s writing it down . . . . All of this action is bookended by long shots that pointedly show us the character arriving at the station and leaving it.

I suggested in the earlier entry that in Ultimatum, Greengrass takes more risks than in the previous film. He still assigns one piece of information per shot, but now that piece is sometimes not in focus, or slips out of the center of the frame, or is glimpsed in a brief close-up. The September issue of American Cinematographer, which arrived as I was completing this entry, explains that he encouraged his camera operators to follow their own instincts about focus and composition. (3) Seeing Ultimatum again, I realized that the film can get away with this sideswiping technique by virtue of certain conventions of genre and style.

A telltale clue, like the charred label left over from a car bomb, can be given a fleeting close-up because physical tokens are carrying us from scene to scene throughout the film and we’re on the lookout for them. A sniper racing away out of focus in the distance is a character we’ve seen before, and he’s spotted in frame center before he dodges away. The larger patterning of shots relies on crosscutting or point-of-view alternation (Jason looks/ what he sees/ Jason reacts), and so the framing of any shot can be a little less emphatic. Given intensified continuity’s emphasis on tight close-ups for dialogue, faces can be framed a little loosely, trusting us to pick up on what matters most—changes in facial expression.

In short, because there’s only one thing to see, and it’s rather simple, and it’s the sort of thing we’ve seen before in other films and in this film, it can be whisked past us. This tactic crops up from time to time in Liman’s first installment, when a shot seems to fumble for a moment before surrendering the key piece of data. For example, Jason is striding through the hotel and a wobbly point-of-view shot brings the hotel’s evacuation map only partly into view.

Again, Greengrass takes a visual device that was used occasionally in Identity and extends it through an entire film.

Realism, another word for artifice

Finally, what’s the purpose behind Ultimatum’s thoroughgoing exploitation of run-and-gun? I quoted Greengrass’s claim that it conveys Bourne’s mental states, and some critics have rung variations on this. Of course the cutting is choppy and the framing is uncertain. The guy’s constantly scanning his environment, hypersensitive to tiny stimuli. Besides, he’s lost his memory! Yet the same treatment is applied to scenes in which Bourne isn’t present—notably the scenes in CIA offices. Is Nicky constantly alert? Is Pam suffering from amnesia?

Alternatively, this style is said to be more immersive, putting us in Bourne’s immediate situation. This is a puzzling claim because cinema has done this very successfully for many years, through editing and shot scale and camera movement. Don’t Rear Window and the Odessa Steps sequence in Potemkin and the great racetrack scene in Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan thrust us squarely into the space and demand that we follow developing action as a side-participant? I think that defenders need to show more concretely how Greengrass’s technique is “immersive” in some sense that other approaches are not. My guess is that that defense will go back to the handheld camera, distractive framing, and choppy cutting . . . all of which do yield visceral impact. But why should we think that they yield greater immersion?

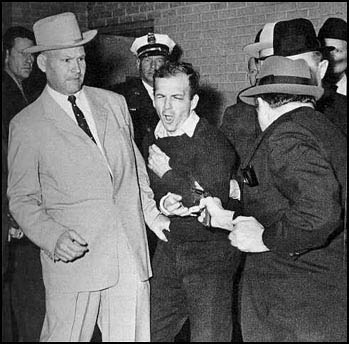

I think we get a clue by recalling that Supremacy and Ultimatum display the run-and-gun strategy that Greengrass employed in Bloody Sunday and United 93. This approach implies something like this: If several camera operators had been present for these historic events, this is something like the way it would have been recorded. We get a reality reconstructed as if it were recorded by movie cameras. I say cameras because we’re telling a story and need to change our angles constantly; a scene couldn’t approximate a record of the event as experienced by a single participant or eyewitness. In movies, the camera is almost always ubiquitous.

Recall the famous TV footage of Jack Ruby shooting Lee Harvey Oswald. There the lone camera lost some of the most important information by being caught in the crowd’s confusion and swinging wildly away from the action. But in a fiction film, we can’t be permitted to miss key information. So with run-and-gun, the filmmakers in effect cover the action through a troupe of invisible, highly mobile camera operators. That’s to say, another brand of artifice.

In general, the run-and-gun look says, I’m realer than what you normally see. In the DVD supplement to Supremacy, “Keeping It Real,” the producers claimed that they hired Greengrass because they wanted a “documentary feel” for Bourne’s second outing. Greengrass in turn affirms that he wanted to shoot it “like a live event.” And he justifies it, as directors have been justifying camera flourishes and fast cutting for fifty years, as yielding “energy. When you get it, you get magic.” (4)

I’d say that the style achieves visceral disorientation pretty effectively, but some claims for it are exaggerated. So far Greengrass has matched the style to hospitable genres, either historical drama or fast-paced espionage. But isn’t immersion something we should try for in all genres? Wouldn’t High School Musical 2 gain energy and magic if it were shot run-and-gun? If a director tried that, some critics might say that it added intensity and realism, and suggest that it puts us in the minds and hearts of those peppy kids in a way that nothing else could.

I finish this overlong post by invoking Andrew Davis, director of The Fugitive (which back in 1993 gave us fragmentary flashbacks à la Bourne Ultimatum) and the admirable Holes.

When you think about the beginnings: everything was very formal and staged and composed, and then years later people said, “We want it shaky and out of focus and have some kind of honest energy to it.” And then it became a phony energy, because it was like commercials, where they would make everything have a documentary feel when they were selling perfume, you know? (5)

Whether you agree with me or not, I’m glad that The Bourne Ultimatum raised issues of film style that audiences really care about. I’m eager to look more closely at the movie when the DVD is released, but don’t worry–I don’t expect to mount another epic blog entry.However, I do have an item coming up that talks about how we assess what filmmakers say about their movies….

(1) I’m aware that this can be an uncomfortable option, but not as bad as with music. Many years ago I sat in the front row of a John Zorn concert, and I don’t think my ears ever recovered.

(2) Quoted in Rob Feld, “Q & A with David Koepp,” in Josh Friedman and David Koepp, War of the Worlds: The Shooting Script (New York: Newmarket Press, 2005), 136-137.)

(3) See Jon Silberg, “Bourne Again,” American Cinematographer (September 2007), 34-35, available here.

(4) Oddly, though, in the DVD supplement to The Bourne Identity, Frank Oz says that Liman brought “a rough-edged, very energetic” feel to the project, thanks to his indie roots. Interestingly, the energy is attributed to Liman’s abilities as a camera operator, a skill that enables him to shoot things quickly. The same supplement offers a familiar motivation for the film’s purportedly jittery style: the hero is trying to figure out who he is, and so is the viewer. Just as the films revamp a basic plot structure each time, perhaps the producers’ rationales get recycled too.

(5) Quoted in The Director’s Cut: Picturing Hollywood in the 21st Century, ed. Stephan Littger (NY: Continuum, 2006), 96.

PS: On a wholly unrelated subject Kristin answers a question on Roger Ebert’s Movie Answer Man column: What was the first movie?

PPS 5 January 2008: Steven Spielberg weighs in on the Bourne style here, confirming that he’s a more traditional filmmaker. Thanks to Fred Holliday and Brad Schauer for calling my attention to his remarks.