Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

Len Lye, Renaissance Kiwi

Kristin here–

David and I have many pleasant memories from our May visit to New Zealand, where as Hood Fellows we were resident at Auckland University for a month. Among these memories is meeting Roger and Shirley Horrocks. Roger has been a major figure in the development of film studies and culture in New Zealand. He founded the Department of Film, Television and Media Studies at Auckland University and was its head until his retirement in 2004. He co-founded the Auckland International Film Festival and has written on television and film in New Zealand.

Shirley is a producer and director of documentary films, many of them about Kiwi art and culture, made primarily for TVNZ and NZ On Air. In 1984 she founded her own production company, Point of View Films.

Retrieving Len Lye

Among the Horrocks’ accomplishments has been to aid in the preservation of the work of filmmaker/ sculptor/ painter/ poet/ theorist Len Lye (1901-1980) and to disseminate information about this undeservedly overlooked figure. Roger generously gave us a copy of his impressive book, Len Lye: A Biography, and Shirley presented us with a DVD of her documentary on Lye, Flip & Two Twisters, named for one of the artist’s sculptures.

I remember seeing a few Len Lye films long ago and thinking they were delightful and innovative. In working on our textbooks, I had the privilege of sitting in one of the British Film Institute’s refrigerated viewing rooms and seeing a gorgeous nitrate copy of his 1936 film Rainbow Dance. Color frames from it appear in Film Art (8th edition, p. 164) and Film History (2nd edition, p. 321). I had also seen Lye’s strange and evocative first film, Tusalava (1929), an animated film with abstract shapes much influenced by Maori and Australian Aboriginal art (illustrated on p. 176 of Film History).

Lye was born and grew up in New Zealand, lived for stretches in Samoa and Sydney, moved to London as a young man, and moved permanently to New York in 1944. He was extraordinarily attuned to sensory perception and rhythm and was drawn to the indigenous art of the southwest Pacific area. From an early age he studied modern art and especially abstraction.

Lye belonged to a generation of innovative animators who began working in the 1920s and 1930s: Oskar Fischinger in Germany and later the U.S., and Alexandre Alexeïeff and Claire Parker in France and later Canada. Although their styles differed considerably, all sought to find alternatives to Hollywood cel animation and to explore the relationship between music and cinema.

Roger and Shirley’s gifts inspired me to renew my acquaintance with Lye’s work and take a closer look at his career. “I’ll just order a DVD of Lye’s films,” I thought to myself. Back in the late 1980s Pioneer had issued a marvelous though brief series called “Visual Pioneers.” David and I had bought “The World of Oskar Fischinger” and “The World of Alexandre Alexeïeff.” I figured that these had probably been re-issued on DVD, along with the rest of this short-lived series. It turns out, no. Lucky we held onto those laserdiscs!

Unfortunately, there was never a “Visual Pioneers” disc devoted to Lye.

The age of DVDs has not served these filmmakers well, either. One has to be doggedly determined in finding and acquiring their work. The bountiful “Unseen Cinema” set from Image contains Oskar Fischinger’s An Optical Poem (1938), an abstract short film made for MGM (!) after the filmmaker moved from Germany to the U.S. It’s on the disc titled “Viva la Dance: The Beginnings of Ciné-Dance.” Although the set claims to deal with the American avant-garde up to 1941, Alexeïeff and Parker’s 1934 masterpiece Une nuit sur le Mont Chauve (Night on Bald Mountain) is included. I suppose the logic there is that Parker was an American, though she and Alexeïeff (born in Russia) made the film in Paris and worked thereafter in Europe and Canada. (A few other émigré directors’ European works are in the set, though I can’t see why Anémic cinéma by Marcel Duchamp [aka Rrose Sélavy] should be there.)

There is a French region 2 DVD of the pair’s work available. I found it for sale online at fnac and Cinedoc. A DVD of ten Fischinger films is available from the Center for Visual Music’s shop; it actually sells the disc through Amazon, which might make it relatively easy for some to acquire.

The Center’s shop carries a variety of experimental cinema, and there I found a collection of Lye’s films—on VHS. “Rhythms” contains twelve of Lye’s major works, including A Colour Box (1935) and Rainbow Dance. It was brought out by Re: Voir, a major distributor of avant-garde cinema. One can buy it from that company, though in the U.S. the Center is a convenient source. My copy from the latter came quite quickly.

The cassette does not include Tusalava. The only place that seems to be available is on YouTube, and I hesitate to recommend it, given the fuzziness of the image. (Poor copies of some other Lye films are there as well, but since the tape contains far better versions there is no good reason to link to them.) Tusalava survives in beautiful condition, and I hope it eventually could be added to an expanded Lye collection on DVD.

Don’t be misled by the collection “The Experimental Avant-garde Series Number 19–The Serious, the Silly, and the Absurd.” There the short Lambeth Walk Nazi Style is wrongly attributed to Lye–a fairly common mistake. Lye’s short, Swinging the Lambeth Walk (1939), is an abstract film using the same pop song as a soundtrack; it’s on the “Rhythms” tape.

The Filmmaker

Perhaps one reason why Lye’s films command less attention today than they should is simply because they are so short. All twelve films on the “Rhythms” tape add up to a mere 47 minutes, and even the seven-minute Tusalava would fail to bring the total to one hour.

This paucity of footage results in part from the painstaking labor involved in making them. Some of Lye’s films depended on elaborate painting and scratching directly on 35mm film stock. This kind of animation was Lye’s innovation and not, as is widely assumed, that of Norman McLaren. A Colour Box looks remarkably like a McLaren film. The resemblance is not coincidental. One of the few periods during which Lye had institutional support was when he worked for the GPO Film Unit in London. McLaren was freshly out of art school and working at the same unit. He freely acknowledges his amazement at seeing and hearing A Colour Box and its influence on him: “Apart from the sheer exhilaration of the film, which intrigued me was that it was a kinetic abstraction of the spirit of the music, and that it was painted directly onto the film. On both these counts it was for me like a dream come true.” (pages 144-45 of Len Lye: A Biography.)

An equally revolutionary technique Lye used was no less time-consuming. The new color film stocks of the 1930s fascinated him, especially the three-strip processes. These recorded each of the three primary colors on a separate strip of black-and-white film, with the color of the final film being achieved by adding color dyes to the matrices and combining them. Technicolor is the most famous of these systems, though Lye drew upon European processes, including Gasparcolor. Lye seems to have been alone in his realization that one could use the three-strip technique on film shot originally in black-and-white.

Rainbow Dance was made by shooting, in black-and-white, a human figure leaping, playing tennis, and executing other actions against a white screen and then using the result as a silhouette filled with vivid, saturated colors. Abstract and semi-abstract shapes surrounding the figure, constantly moving and changing, create a dazzling effect. The film ends abruptly with the message, “The Post Office Savings Bank puts a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.” As advertisements, some of Lye’s films of the 1930s played in theaters, though viewers often perceived them as experimental shorts.

Another reason for the lack of attention paid to Lye is that he was always very much an eccentric loner, working on the periphery of Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, and kinetic art. Works by him were included in exhibitions devoted to these trends, but Lye always refused the prominence that allegiance with fashionable movements might have given him. He was also highly impractical about money and not adept at explaining his projects to potential grant-bestowing foundations.

The Legacy

Roger Horrocks met Lye late in the artist’s life and worked as his assistant in his final months. Roger and Shirley were involved in setting up the Len Lye Foudation, housed at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in New Plymouth, New Zealand. (Its website is the best online source of information on Lye.) The foundation’s collection include extensive unpublished writings by Lye, to which Roger had complete access. He also interviewed a wide range of people who had known Lye in various capacities. The result is not only thorough, but it also gives a lively sense of a profoundly eccentric artist.

As part of Lye’s fascination with the senses, he deliberately cultivated a sort of stream-of-consciousness language, both for speech and writing. The result often suggests someone communicating in poetry rather than prose, and the quotations are not always easy to understand. One note scribbled after Lye had seen a film reads, “The knobbly cast of the star Elliott Gould, bemused, his mouth full of marbles, finally flapping his foot-flippers enrout insouciantly to some horizon or other” (p. 294). Roger, however, has waded through a large, difficult set of notes and journals. As he puts it, “It took my years to find my way round this chaotic collection of fragments and drafts, but ultimately it proved a goldmine.” One early reader of the biography remarked that “the book felt at times more like an autobiography than a biography” (p. 3). This is an astute observation, for Roger has woven many quotations into his own prose and thus given a structure to the chaos. By the end one feels that one understands not just the facts of Lye’s life but also his personality.

(Unfortunately the biography, published by Auckland University Press in 2001, is already out of print. With luck there’s a copy in your local library.)

The Sculptor

For film fans and scholars with at least a passing knowledge of Lye’s shorts, the real news here will be his versatility as an artist. Before he started making films, he was already an accomplished painter. Because painting was a relatively inexpensive activity, Lye often did not promote his own work and simply gave the paintings to friends. He sought buyers and patrons for his kinetic sculpture, though, because he needed funding to build these ambitious projects.

A few museums, like the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney, own Lye pieces, but on the whole his kinetic sculptures, many of which are large and difficult to maintain in working order, are not widely or continuously displayed. Indeed, much of Lye’s later life was devoted to designing huge pieces, only some of which have been realized even now. The Len Lye Foundation is committed to realizing posthumously the plans he left behind, though no doubt some of his more grandiose schemes will remain too impractical to render.

Shirley’s documentary Flip and Two Twisters (1995) helps fill in that side of the artist’s career for those who cannot travel to New Plymouth. Although she sketches Lye’s career and shows clips from some of the films, the real revelation is footage of Lye at work on some of the main pieces, like “Blade” (1954) and “Flip and Two Twisters” (1965). The dates, by the way, are a little misleading, as Lye continued to modify his sculptures after their initial versions were finished—usually making them larger.

“Flip and Two Twisters” is a casual name for a formidable piece, though Lye eventually took to calling it “Trilogy.” The sculpture consists of a large looped ribbon of flexible steel suspended from the ceiling, flanked by two vertical strips of similar steel. Once set in motion, the thrashing and twisting movements of these three elements gradually become quite loud and violent. Onlookers declare that it is frightening to be in the same room with the sculpture, as even just watching it on video makes plausible.

This documentary would be a terrific teaching supplement for a course on avant-garde cinema. Copies are available direct from Point of View Films.

Shirley gave us three of her other documentaries. Kiwiana (1996), as its name suggests, explores some of the icons of New Zealand’s popular culture. Kiwis were beginning to appreciate these neglected everyday objects, which were becoming collectibles in the 1990s: the buzzy-bee, the gumboot, and, yes, the kiwi fruit. Peter Jackson even makes a brief appearance as a talking head. Marti: The passionate eye (2004) chronicles the extraordinary life of Marti Friedlander, who was raised in a Jewish orphanage during the 1930s and 1940s in London. She was trained as a photography laboratory technician but also became a photographer. Emigrating to New Zealand, she worked on a series of Maori portraits and documented such moments of political ferment as the Women’s Movement. Finally, The New Oceania (2005) is a portrait of the Samoan-born writer Albert Wendt and his fostering of a new Pacific culture based on local traditions but embracing modernism. All of these films are available from Point of View.

We are grateful to Roger and Shirley for being among the many who made us feel so welcome in Auckland. I’m particularly grateful for being led to revisit and explore a director who deserves to be far better known.

Watching movies very, very slowly

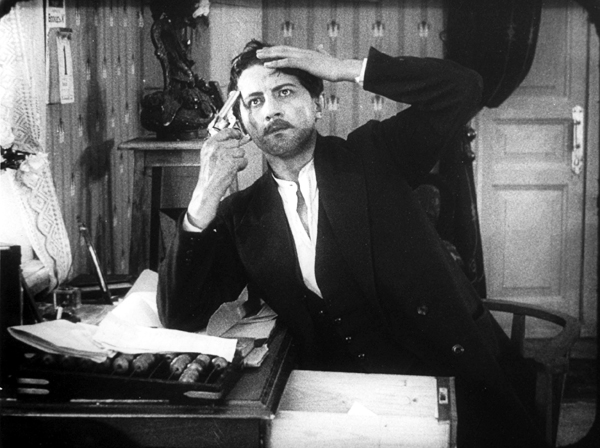

Children of the Age (1915).

DB here:

Before DVD and consumer videotape, how could you study films closely? If you had money, you could buy 8mm or 16mm prints of the few titles available in those formats. If you belonged to a library or ran a film club, you could book 16mm prints and screen them over and over. Or you could ask to view the films at a film archive.

I started going to film archives in the late 1960s, when they were generally more concerned with preserving and showing films than with letting researchers have access. Over the 1970s and 1980s this situation changed, partly because several archivists grew hospitable to the growing field of academic film studies.

I started going to film archives in the late 1960s, when they were generally more concerned with preserving and showing films than with letting researchers have access. Over the 1970s and 1980s this situation changed, partly because several archivists grew hospitable to the growing field of academic film studies.

At first archives found it easier to screen films for researchers in projection rooms, but eventually many let visitors watch the films on stand-alone viewers. That way the researcher could stop, go forward and back, and take notes. In researching my dissertation in the summer of 1973, I watched films at George Eastman House in 16mm projection, but a few weeks later in Paris, Henri Langlois of the Cinémathèque Francaise allowed me time on Marie Epstein’s visionneuse (a term I’ve admired ever since).

Over the years Kristin and I have visited archives in various countries. We’ve become particularly close to the Royal Film Archive of Brussels, partly because back in the 1980s the head, Jacques Ledoux, believed that Kristin’s research was worthwhile and allowed us to visit regularly. Without the cooperation of Ledoux and his successor Gabrielle Claes, we couldn’t have done a great deal of our research. No wonder it helped us so much: the Belgian Cinémathèque is arguably the most diverse archive in the world.

Case in point: My current visit. I came with two goals. First, I had to prepare for my lectures in Bruges later in the month. These consist of eight talks on anamorphic widescreen. So I planned to watch four early CinemaScope films, plus Oshima’s The Catch (1961) and the SuperScope version of While the City Sleeps.

I also wanted to fill in a big gap in my knowledge about a major silent filmmaker. More on him shortly.

Viewing on a visionneuse

If you’ve never watched a film on a viewer, let me explain. The classic viewer is a flatbed, or viewing table. It’s the size of an executive desk. Two platters or spindles hold a feed reel and a take-up reel. Motors drive the film through a series of sprocketed gates, past a projection device (usually a prism) and across a sound head. The film appears on a smallish screen. There’s usually a little surface space to set a notepad, along with a lamp on an articulated arm.

Before digital editing came along, such machines offered the only way filmmakers could cut sound and picture. (Now most phases of editing are done on computer, with physical editing reserved for late stages of postproduction.) Eventually flatbeds were offered in simpler versions for playback rather than editing.

The most common American-made viewer was the Moviola, which was initially not a flatbed but an upright machine. Eventually the German Steenbeck and KEM became the high-end standards for editing picture and sound. The Brussels archive relies on the Prévost, an Italian machine that is very easy to maintain. The Prévost, seen above, beams the image from the prism onto a mirror hanging over the machine, which bounces the picture onto the screen.

35mm films are mounted on 1000- or 2000-foot reels, the latter yielding about twenty minutes of film at sound speed. A feature film will consist of four or more 2000-foot reels. Even if you watch a film straight through, without stopping to make notes, it takes time to change the reels, so a two-hour movie will probably consume nearly three hours on a 35mm flatbed. And of course researchers stop a lot to take notes and move to and fro across a scene. If I’m studying a film intensively, I probably consume about an hour per 2000-foot reel. Across my life, I wouldn’t dare calculate how many months I’ve spent in visionneuse viewing.

Viewing on an individual viewer has both costs and benefits. Sometimes details you’d notice on the big screen are hard to spot on a flatbed. But with your nose fairly close to the film, you can make discoveries you might miss in projection. (Ideally, you would see the film you’re studying on both the big screen and the small one.) In addition, of course, you can stop, go back, and replay stretches. Above all, you get to touch the film. This is a wonderful experience, handling 35mm film. Hold it up to the light and you see the pictures. You can’t do that with videotape or DVD.

The scary part of any flatbed viewing, at least for me, is watching the film whiz along under your nose at ninety feet per minute. If you haven’t threaded the thing properly, or if the print has a weak splice or torn sprocket hole, you can rip the film. For this reason, archives typically don’t allow a researcher to handle films they hold in only one copy.

The average film you watch on a flatbed has an optical soundtrack, that squiggly line that is read by an optical valve. But early CinemaScope films had magnetic tracks so that they could provide stereophonic sound. In the picture below you can see that strips of magnetic tape, like those in tape cassette players, run along both edges of the film strip. For my Scope films, I was obliged to use a Prévost that could handle mag sound–and of course one that could be fitted with an anamorphic lens to unsqueeze the image to the proper proportions.

Hell on Frisco Bay (1954) was a color movie, but this print, like many from the period, has faded to bright pink. The Eastman color stock of the period was unstable, and many prints were processed carelessly. (In unsqueezing the frame, I’ve eliminated the color cast for better clarity.) Restoring color to films of this period is one of the major tasks facing film archivists. Cinema is a fragile art form.

Hours and hours of Bauers and Bauers

At the Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone in 1989, Yuri Tsivian’s retrospective on Russian Tsarist cinema convinced a lot of us that good filmmaking in that country didn’t start with the Bolshevik revolution. Along with that retrospective came a wonderful book, Silent Witnesses, edited by Yuri and Paolo Cherchi Usai. Unfortunately hard to find now, it’s filled with information about pre-Soviet filmmaking.

Although I enjoyed the Tsarist films, I didn’t know exactly what to watch for. It took me some years to appreciate their artistry, and some of my ideas about them showed up in On the History of Film Style (1997) and Figures Traced in Light (2005). In those places I studied 1910s “tableau” staging and used some examples from Yevgenii Bauer, by common consent the most pictorially ambitious Russian director of the period. Kristin and I also used Bauer as an example of tightly choreographed mise-en-scene in Film Art (p. 143). I thought it was time I examined his work more systematically, and I knew that the Royal Film Archive held some Bauer prints, which they acquired from Gosfilmofond of Moscow.

Bauer had a brief but prolific career. He started directing in 1912 and completed eighty-two films before his death in 1917. Unhappily, only twenty-six of his works survive. Just as bad, most of those lack their original intertitles, so we don’t have the expository and dialogue titles we expect in silent films. The placement of the titles is sometimes signaled by two Xs marked on two successive frames. Without titles, the storylines can get obscure. Yuri, Ben Brewster, and other scholars have sought to reconstruct something approximating the original titles by studying the plays and novels that Bauer adapted. Three of the reconstructed films are available on a DVD called Mad Love, and Yuri has also created an innovative CD-ROM (right) that takes us through works of Bauer and his contemporaries.

Bauer had a brief but prolific career. He started directing in 1912 and completed eighty-two films before his death in 1917. Unhappily, only twenty-six of his works survive. Just as bad, most of those lack their original intertitles, so we don’t have the expository and dialogue titles we expect in silent films. The placement of the titles is sometimes signaled by two Xs marked on two successive frames. Without titles, the storylines can get obscure. Yuri, Ben Brewster, and other scholars have sought to reconstruct something approximating the original titles by studying the plays and novels that Bauer adapted. Three of the reconstructed films are available on a DVD called Mad Love, and Yuri has also created an innovative CD-ROM (right) that takes us through works of Bauer and his contemporaries.

Although he made comedies, Bauer is most famous for his somber psychological melodramas, often centering on class exploitation. A woman becomes a rich man’s mistress; when she abandons her husband and takes their baby, he commits suicide (Children of the Age). A serving maid is seduced by her master and callously tossed aside when he marries a flirt (Silent Witnesses). Things can get pretty dark. This is the director who made films entitled After Death (1915) and Happiness of Eternal Night (1915). In Daydreams (1915), a widower sees a woman who strikingly resembles his dead wife. Like Scottie in Vertigo, he follows her and becomes increasingly obsessed. Did I mention that he keeps a ropy braid of his dead wife’s hair in a glass box?

Seeing several films again confirmed my view that Bauer knew better than most directors how to organize a shot. His contemporary Louis Feuillade favored a quiet, sober virtuosity, but Bauer developed a flashy visual style. He’s most known for his ambitious use of light (Frigid Souls, below) and big, textured sets packed with columns, trellises, drapes, brocades, embroidered pillowcases, and other elements that add abstract patterns to a scene (Children of the Age, below).

Even a hammock can be stretched and framed to create a swooping web around the innocent heroine of Children of the Age, ensnared by the demimondaine.

In particular, I admire Bauer’s constant inventiveness in moving his actors around the set in smooth ways that always direct our attention to what’s happening at the right moment. European directors of this period seldom cut up a scene into several shots of individual actors; the frame typically shows us the entire playing space. Directors were obliged to shift their actors across the frame and arrange them in depth, like chesspieces.

This master-shot, single setup approach might seem hoplelessly restrictive. Today we expect films to have lots of cutting and camera movement. How does the filmmaker sculpt the action, moment by moment within a static frame?

Blocking, as in blocking the view

I trace some principles of this approach in the books I already mentioned. I’ll mention two strategies here, and if you want to know more you can follow up in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light.

Filmmakers of the 1910s created intricate choreography by moving actors left or right, up to or away from the camera. Often they set up unbalanced compositions and then rebalanced them, creating a kind of spatial tension that parallels the drama. In the course of the action, actors close to the camera might conceal those that are farther away. The blocking of the actors, in other words, also sometimes blocks our view.

In Leon Drey (1915), Bauer tells the story of a cynical womanizer. In one scene, he’s dallying with his latest conquest when another of his lovers bursts into his apartment. The first phase of the shot is very unbalanced; most directors would have put the mistress at the door on one side of the frame and Leon and the woman in his arms at the opposite side. Immediately, though, the woman flees to the bed in the back of the shot and activates the right area of the frame.

As the mistress rushes to the woman in the rear, Leon strides to the foreground and his burly body blots out the drama between the two women. We’re forced to concentrate on his cold indifference to both of his lovers. Eventually his mistress comes to the foreground to remonstrate with him. Now, at the high point of the scene, we have a balanced frame. Note that Leon continues to conceal the first woman; the scene’s not yet about her.

The mistress leaves, angry and desperate, and Leon placidly pays her no mind. As the door closes, he hurries to lock it and summons the first woman, now visible, back from his bed. He will have little trouble convincing her to return to his arms.

The dramatic curve of the scene has been expressed in compositional asymmetry and symmetry, concealing space and then opening it up.

Most directors of the period used principles like these to turn dramatic conflict into vivid choreography. Bauer also tried more unusual tactics. He was especially good at shifting actors’ heads very slightly to open or close off channels of action behind them. Here’s an instance from Her Heroic Feat (1914).

The butler informs Lina and her mother that the scandalous ballerina Klorinda is calling on them. At first Lina’s head is solidly blocking the doorway in the rear. As the butler goes to the rear door, Lina pivots a little to clear our view of that doorway.

Klorinda sashays in, and who could miss it? She’s wearing a bright dress, she’s centrally positioned, and she’s moving toward us. The other women refuse to look at her, but their immobility assures that we keep our eye on Klorinda. When she stops to greet them, then they move, pivoting away; Lina’s head goes back to blocking the doorway. Imagine how things would have gone if her head had been there when Klorinda appeared in the background.

Of course, we should also study the performance techniques of Bauer’s actors–a subject examined in a fine book by Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs, Theatre to Cinema. The compositional tactics employed here work to draw our attention to the actors’ expressions and body language.

Still, not everything in 1910s ensemble staging owes a debt to the theatre. The changes in Lina’s head position, or Leon Brey’s calculated blockage of the women behind him, wouldn’t work on the stage; most of the audience wouldn’t see the exact alignment we get onscreen. Live theatre depends on varying sightlines, but in cinema, we all see the action from one position, that of the camera. Bauer, Feuillade, and their contemporaries realized that they could organize the action, down to the smallest detail, around what the camera could and could not take in.

The fluent choreography developed by 1910s directors is almost unnoticeable when you’re watching in real time. You’re supposed to register the what–the point of interest in the frame–rather than the how, the slight shifting of actors that highlights this face, then that gesture. By the time you realize that something has happened, the first stages of the process have slipped away, inaccessible to memory.

So there’s a need for slow viewing. Filmmakers have thousands of secrets, many that they don’t know they know. Sometimes we have to stop the movie, go back, and trace precisely how directors achieve their effects. Really slow viewing can help us discover how deep film artistry can be. All hail the visionneuse and the archives that allow scholars to use her.

For background on Bauer, see William M. Drew’s excellent career survey. I discuss Bauer’s relation to narrative painting in another blog entry.

In production and distribution of the period, the titles and inserts (close-ups of newspapers or messages) were sometimes stored on separate reels. In many cases, only the image reels have survived.

Several other Bauer films are available on Milestone’s invaluable DVD set Early Russian Cinema.

Christian Bale picks up a rail

DB here:

In James Mangold’s 3:10 to Yuma, some law officers are taking the captured killer Ben Wade (Russell Crowe) to the farmhouse of Dan Evans (Christian Bale). When the stagecoach sinks into a rut, Evans limps out of his house, snatches up a fence rail, and uses it to pry the wheel free.

Not an earth-shattering moment, but one I got to know pretty well last week when I visited the mixing session as the director’s guest. About a year ago, Jim sent me an email expressing his liking for my book The Way Hollywood Tells It. We kept corresponding through the planning and production of Yuma, and last month he asked me if I wanted to see the picture-locked film and visit a sound mixing session.

As we say in Wisconsin: You bet.

Watch their eyes

Mangold has been prolific, turning out seven films in about twelve years. Heavy, CopLand, Girl, Interrupted, Kate and Leopold, Identity, and Walk the Line nicely illustrate the difference between convention and cliché. While embracing each genre’s conventions, Mangold always tries to enlarge, enrich, and explore them. Where other directors try for brute impact, he seeks out implication and understated lyricism. Above all there are the nuanced performances, female ones in particular. (Remember those Oscars for Angelina Jolie and Reese Witherspoon.) If anybody can bring the psychological nuances of that elusive “indie sensibility” to mainstream filmmaking, James Mangold is a likely candidate.

As a writer-director, he balances concern for story and character with a carefully wrought visual style. The opening of Heavy makes a shabby tavern beautiful through precise compositions and geometrical cutting that recall Ozu, whom Mangold has acknowledged as an influence.

At the same time, he has understood one of the great strengths of the Hollywood tradition—letting the actors’ faces tell as much of the story as possible. He believes that the script should include not only dialogue but also “pieces of silent acting.” John Ford remarked of actors: “Watch their eyes.” Mangold’s version of this precept can be found on the DVD commentary of Girl, Interrupted: “Actors dance with their looks and glances.”

In fact, his commentary tracks are gold. Anybody who wants to know more about the craft of writing and directing should simply sit down and listen. Mangold is not one of those I-do-what-I-feel guys; he channels the story’s feeling into precise, writable and filmable moments, and his commentary tracks explain how he does it.

Delmer Daves’ original 3:10 to Yuma (1957) is one of Mangold’s favorite films, as he explained several years ago in the interview with Tod Lippy that prefaces the published screenplays of Heavy and CopLand. He’s been bold enough to remake it, in an era in which Westerns are supposed to be unpopular. I was keen to see what a director renowned chiefly for intimate psychological dramas would do with a Western. Yet maybe the gap isn’t so great after all. Mangold points out in the Lippy interview that most classic Westerns aren’t action pictures but character studies.

In the shadow of John Ford

The Yuma production has been chronicled elsewhere on the internets, so I won’t rehearse it here. I came in on the third day of mixing. The session was held on the Twentieth Century Fox lot, at the John Ford theater (a lucky spot, surely). Mangold, his editor Mike McCusker, and half a dozen sound specialists had already been working through the morning. The team included the lauded sound rerecording mixer Paul Massey, winner of three BAFTAs and recipient of five Oscar nominations. His work includes Nixon, Clueless, Gattaca, Jerry Maguire, Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World, the second and third Pirates of the Caribbean films, and not least, the wonderful SCTV parody The Last Polka.

For me, it was an intensive four-hour seminar. Once I start to focus on a movie soundtrack, I have to marvel at the level of precision you can find. As we tell our students: It’s hard to really watch a movie, but even harder to really listen to it.

When Jim asked if I’d sat in on a mix before, I had to confess that I’d visited only one—a session in which Walter Murch was blending rustling foliage and mosquito noises for a scene in Apocalypse Now. (Must blog about that some day.) Things had changed a lot since the 1970s. No longer was a scratchy black-and-white print run and rerun; now we get a 4K image on a large screen, crisp and bright and frozen on a frame for as long as you like. Now there are several mixing stations, each one with a glowing Mac monitor alongside.

The standard division of labor endures, but it’s much more refined. Music is filed on many tracks and with a few mouseclicks can be reworked in tempo, timbre, and orchestration. The dialogue tracks consist of thousands of stored line readings, ready to be pulled up in moments. As for sound effects, at this point Yuma had 96 effects tracks, each of them already premixed from many sources. I usually notice the impact that the digital revolution has had on camerawork and editing, but this session really drove home to me the ways in which the computer has made the art of the soundtrack more exact and exacting.

Details, details

Most of the session was devoted to effects. The first problem was that the track seemed to Mangold too “absent,” too thin and empty. Mike remarked that he didn’t feel the atmosphere, the air between the more discrete noises. “There’s nothing of any character that’s holding it all together,” Mike said. The difficulty, though, as Jim pointed out, is that if you simply add in more sounds, you can confuse things. “If we hear just one moo, that becomes an event.” How to thicken the acoustic atmosphere without muddying it or creating competing noises?

Step by step, the team filled in the ambience. They added tiny air currents, always seeking to avoid what Mangold called “radio wind.” We got very soft and distant moos, shifting horse hooves, even low “horse vocals.” After it was all blended, I found the ambience full and modest, but Jim and the others felt that it was still too bright. They would go back later and mute it a bit.

Now that the ambience was fleshed out, the rest of the session was devoted to specific effects and a few lines. Jim asked for a heaving sound as the stagecoach burst out of the rut, more jingling on the coach reins, a little clinking on Russell Crowe’s handcuffs, a gun-cock. When Crowe’s henchman (Ben Foster), watching from the ridge, urges his horse to move, he makes a smootchy tsk-tsk; Mangold wanted to give it a slightly mocking edge, suggesting the killer’s disdain for the guards’ efforts to protect Wade.

During the 1990s I’d noticed the greater detailing of movie soundtracks. I heard garments brushing against sofas and flakes of tobacco crackling when someone lit a cigarette. Now I was seeing and hearing how skilled artisans orchestrated thousands of such sonic micro-events. They clarified a muffled line. They inserted the sound of stagecoach springs shifting. The words “Good luck” were shifted eight frames. At one point Jim asked for a new line to be put in. “We need a ‘Let’s go.'” “Should I steal it?” “Steal it.” How much of this would be heard in the typical multiplex, or even in fancy home theatres? These guys were going all the way down, creating something of great finesse.

Jim reminded me that sound can create a sense of visual momentum too. The coach drives off in two shots, a long shot and an extreme long shot, and Mangold thought it seemed to go a bit faster in the second. So he added noise that gave an accelerating launch to the first shot.

Then there were Mr. Bale’s steps and the rail he picks up, which gave me an acoustic hallucination.

David is hearing things

As Dan Evans limps out of the cabin (he was wounded in the war), Jim found his footsteps too thudding. He wanted to hear that they were “grounded,” that there was some loose earth underfoot. The team worked to add the textures of pebbles and grit as Evans makes his way to the coach. The action was replayed many times. As the texture thickened, the fence rail that Evans grabs started to sound different to me. At first it was a soft but distinct scrape against the ground; at the end of the mix, it had a faintly twangy timbre. I congratulated the team on giving the rail its own little moment.

They looked at me. They hadn’t done a thing to the rail.

Two explanations arise, maybe both correct. (1) The sound team said that constantly replaying a clip can create such little mirages. Faced with so much repetition, maybe the mind needs to project some variation into it. (2) Changing the texture of the whole scene can alter our sense of the individual, unchanged elements. If there was a little twang to the rail, perhaps it came from overtones or other emergent qualities of the mix.

Maybe too, in my third hour of concentrating on minutiae of the track, I was getting oversensitive to sound.

Realism and convention

After the stagecoach drives off, Wade and the men guarding him trudge into Evans’ cabin. There’s a short scene with Wade and his wife, and that too needed its ambient filling in. I noticed that the banker, first glimpsed inside the cabin, is somewhat closer to the couple a few shots later. Jim noticed it too. In a jiffy three or four very soft bootsteps and slightly creaking boards were added, so that subliminally we were prepared to see the banker on the porch.

Night falls and two of the men guarding Wade are lingering on the cabin porch. It was simple dialogue, filled out with the atmospheric sound. The sound mixers had to redo one actor’s line reading, yanking an alternative out of the files. Jim still wasn’t satisfied and thought they might reloop the line later. Most interesting was Jim’s idea to add some softly clinking dishes to the tail of the scene, preparing us for the cut inside to Evans’ family at dinner with Wade. In these ways, barely perceptible sound smooths over cuts and shifts of point-of-view.

In the course of all this, as Paul and Mike and the others were fixing things, Jim came back to talk with me. He answered my questions and we chatted about directors, mostly Spielberg. Close Encounters is a favorite of his, and he pointed out ways in which it’s been influential on a range of other movies. He also showed how aware he is that realism in sound goes only so far and that pure conventions often kick in. In a movie, when somebody hangs up a phone abruptly, the person on the other end hears a dial tone. Does that ever happen in life? You just get silence. But the dial tone conveys a stronger sense that the line has been broken.

In the course of all this, as Paul and Mike and the others were fixing things, Jim came back to talk with me. He answered my questions and we chatted about directors, mostly Spielberg. Close Encounters is a favorite of his, and he pointed out ways in which it’s been influential on a range of other movies. He also showed how aware he is that realism in sound goes only so far and that pure conventions often kick in. In a movie, when somebody hangs up a phone abruptly, the person on the other end hears a dial tone. Does that ever happen in life? You just get silence. But the dial tone conveys a stronger sense that the line has been broken.

Jim halted the session as the family dinner scene began. The team would continue to polish it, and he’d be back tomorrow to keep going. I snapped a picture of him just before he left. Later, I caught up with Mike McCusker, who also edited Walk the Line. He has an enormous respect for Mangold, saying that his success with female performers was reminiscent of Cukor’s accomplishments.

Next day, watching the premix version of the whole movie, I saw Christian Bale limp thuddingly to the coach. Almost no moos or jingles, and definitely no clinking crockery. No twang when he picked up the rail. You almost never get a chance to notice this sort of before-and-after differences on soundtracks, and it brought home to me how much skill and effort would go into reworking every scene. Making movies is really, really hard work. And I remembered another reason I like movies: They sharpen your senses.

Coming attractions

I plan to write more on 3:10 to Yuma in a few days. In the meantime, Kristin may be posting her experience at another mixing session–that one in Wellington, New Zealand in May. Over the next week we’ll also be filing reports from Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna. Sign up for a feed if you want to keep abreast of developments.

Bando on the run

Sakamoto Ryoma (1928).

The Matsuda Eigasha company of Tokyo deserves enormous credit for restoring and making available classic Japanese films. My first visit to the firm twenty years ago was a revelation. Matsuda Shinsui was a former benshi, or spoken-word film accompanist, and he and his sons were collecting old films so that he could accompany them in screenings. A great many of the films were chambara, or swordfight movies. Most survived only in fragments, but what tantalizing fragments they were! (1)

The company made several of the films available on VHS tape, accompanied by benshi commentary prepared by Mr. Matsuda. I came away with several of these treasures. On later visits I was able to watch some films that hadn’t been transferred to video, and several of those deserve to be more widely seen.

When Mr. Matsuda’s son kindly drove me to my train station, I noticed that his car had a VHS player and video monitor installed in the dashboard. So much for my Tokyo-ga experience.

In 1979 Matsuda Eigasha compiled a documentary on the swordplay star Bando Tomasaburo. Now Digital Meme has made it available on DVD, complete with English subtitles. Bantsuma: The Life of Tomasaburo Bando is obligatory viewing for everyone interested in Japanese cinema. Not only does it handily trace Bando’s remarkable career through stills, interviews, and surviving footage. It also supports something I’ve tried to show for some time: that the Japanese action cinema of the 1920s and 1930s was one of the most powerful and creative trends in world filmmaking.

In 1979 Matsuda Eigasha compiled a documentary on the swordplay star Bando Tomasaburo. Now Digital Meme has made it available on DVD, complete with English subtitles. Bantsuma: The Life of Tomasaburo Bando is obligatory viewing for everyone interested in Japanese cinema. Not only does it handily trace Bando’s remarkable career through stills, interviews, and surviving footage. It also supports something I’ve tried to show for some time: that the Japanese action cinema of the 1920s and 1930s was one of the most powerful and creative trends in world filmmaking.

Action and innovation

Some writers have thought that Japanese filmmakers were developing a culturally anchored approach to filmic storytelling independent of Western influences. But in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema and two essays in my forthcoming Poetics of Cinema, I argue something different. By the early 1920s Japanese filmmakers had mastered Hollywood’s norms of visual storytelling. In the Matsuda documentary, this is evident from the clips from early Bando films like Gyakuryu (1924) and Kageboshi (1924). Long shots are broken up into closer views, and conversations are treated in reverse-angle shots of speaker and listener. Camera movements follow the characters as they walk or run.

So far, so conventional. But many Japanese filmmakers revised the American approach, turning it into something more expressive and experimental. So, for example, a very steep high angle in Kirarazaka (1925) serves at first to show us that Bando is surrounded by fighters who use ladders to try to trap him. As the scene returns to this framing again and again, it becomes more abstract, with the fallen ladders becoming vectors of a geometrical shot design targeting the hero.

An even more remarkable example is Orochi (1925), a Bando film that survives intact and in fine shape. (Matsuda released it on VHS; I don’t think it’s on DVD yet.) The clip in the 1979 documentary shows one of Orochi‘s most dazzling passages. The hero, played by Bando, fights his way through a town, and, backed up against a wall, he’s trapped on all sides by his opponents. An extreme long-shot (below) shows us the situation, with Bando in the distant center. Many shots break this space down into opposing forces, Bando versus his adversaries, and quite fast cutting shows the men on either side of him.

The stretch that interests me most begins with a shot of Bando looking left.

The director Futagawa Buntaro then breaks the confrontation into separate shots of the other swordsmen. Nothing unusual about that. But most directors would have handled the next few shots of the standoff this way:

Shot of Bando looking left.

Shot of a combatant looking right (implicitly, back at him).

Shot of Bando looking right.

Shot of a combatant looking left (implicitly, back at him).

This way we’d get a clear, simple sense of the fact that he’s surrounded on all sides. Instead, Futagawa follows the shot of Bando looking left with no fewer than twelve very close shots of fighters, all looking rightward. For example:

Then we get six shots of their arms outthrust, as here:

We then get a shot of several men looking straight to the camera, as if they represent the group directly in front of Bando, no longer at the left. Next there appear another ten shots of fighters looking leftward at Bando, all of them quite close to the camera. For example:

In both sets of shots, many images are composed to match each other graphically: the first group of faces tends to place each man on the left frame edge, while the second set puts most men at the far right. The first set of shots develops a pattern, moving from tight facial close-ups to shots of arms and swords thrusting toward Bando. The second set develops toward showing faces that are ever more cut off by the right frame edge.

Add in the fact that all these shots are cut very quickly, ranging from four frames down to one! This is extraordinarily rare in 1925 cinema. (I talk more about how to study such passages in an earlier blog.) Words can’t really convey the way these images clatter against one another. Their percussive speed makes them graspable only as a tense thrust in one direction countered by an equally tense one opposite. Faces pile frantically up against Bando first one one side, then the other. The sense of linear force is strengthened by the shift from the cluster of face shots to that of the arms, with the transition handled in a pair of weird jump cuts along different men’s arms.

The transition from the first shot above to the second creates the impression that the man has jabbed with his spear, while the cut from the second to the third shot eases us to the forearm shots shown earlier.

This bravura passage is triggered by the initial shot of Bando, haggard and shaky. Perhaps the cascade of shots is motivated as subjective, reflecting his exhaustion in the face of entrapment. Just as likely, I’d say, is the fact that Futagawa took a stereotyped situation, the hero surrounded by his adversaries, and looked for a way to make it fresh, to use energetic stylistic innovation to amplify the story point emotionally and perceptually.

Nothing in the sequence violates continuity editing’s basic principles. The shots keep screen direction constant and character position clear. Indeed, the director has understood spatial continuity very deeply: the men to the left of Bando are pushed far to the left side of the frame, the men to the right are squeezed rightward, so that Bando is always implicitly filling the area they’re recoiling from. But what American director would have risked such a bold piece of cutting?

Orochi, let’s remember, was released the same year as Strike and Potemkin. If this passage had been known to the earliest generation of film historians, Japan might well have been greeted as another birthplace of daringly dynamic montage. (2)

There are several other intriguing flourishes in the footage on display in Bantsuma, particularly a scene of Bando dying in a swirl of steam (this entry’s top image). But two points should be clear: this is innovative filmmaking of a high order, and it took place in a shamelessly commercial film industry. Mainstream filmmaking in Japan has been open to stylistic experiment to a degree rare in other popular cinemas. You can trace a line from the 1920s to the present, from the chambara directors through Ozu and Mizoguchi and Kinoshita and Suzuki Seijin right up to Kitano and Miike. Along a parallel path, Hong Kong action cinema pressed filmmakers toward creative renovation of film technique. (3) In this tradition, the action films of Bantsuma and his peers hold an honored place.

The lessons are familiar ones from this blog. Mass-market cinema harbors experimental impulses; creative directors working in well-known genres are often striving to push the limits. By attending to technique, we can discover a dazzling variety in areas of film history not usually considered “artistic.”

PS: Through Digital Meme, Matsuda has also made available a treasury of 55 animated films from the earliest years. The are at work on a DVD of early Mizoguchi films, including a fragment I’m keen to see from Tojin Okichi (Okichi, Mistress of a Foreigner, 1930).

(1) A large set of them has been available for some years on a DVD-ROM, also available from Digital Meme. For useful reviews, go to Midnight Eye and hors champ.

(2) ) I offer several other examples in the essays “Japanese Film Style, 1925-1945” and “A Cinema of Flourishes” in the forthcoming Poetics of Cinema.

(3) I make this argument in Planet Hong Kong and the essays “Aesthetics in Action” and “Richness through Imperfection” in Poetics of Cinema.