Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

Ozu the compassionate satirist: THE FLAVOR OF GREEN TEA OVER RICE on Criterion Blu-ray

DB here:

Another bountiful disc release from Criterion: Ozu’s 1952 classic in a 4K digital restoration, with newly translated subtitles. It comes with an enlightening essay by Junji Yoshida and Daniel Raim’s ingratiating documentary on Ozu’s collaboration with his screenwriter Kogo Noda. I contributed a video essay on the film. The most wonderful bonus is Ozu’s 1937 feature What Did the Lady Forget?, which has fascinating affinities with the later movie.

What did which lady forget?

I’ve long been a fan of What Did the Lady Forget? It’s a quasi-screwball comedy treating the clash of the sexes and the generations. As is typical for Ozu, it starts light, abetted by a languid guitar-and-banjo soundtrack, before sidling into graver moments.

In my commentary I touch on its social satire. As the Shochiku studio began making more films about prosperous families, Ozu moved away from the working-class and salaryman milieus he had explored in many masterpieces of the 1930s. I argue in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema that this film’s comic treatment of the professional class looks forward to what he’ll offer in Equinox Flower (1958) and other postwar films.

A married couple hosts a visit from their sashaying, cigarette-smoking niece, a moga (modern girl) who turns out to be not quite as tough as she thinks. While exploring the city’s nightlife (and occasionally brandishing a fencing foil), Setsuko exposes the tensions in the apparently easygoing marriage. The comedy drifts into moments of Ozuian pathos and melancholy–a chastened Setsuko has to leave Tokyo–but the film ends on a light note.

Stylistic finesse is on display throughout. The framings are dazzlingly inventive, the perspectives are steep, and we’re given those quietly permutational “establishing shots” that introduce scenes in Setsuko’s room.

The weird graphic matches in the two boys’ “hit the spot” game could not have been devised by anybody else.

I just love this stuff. There’s so much here, how can this movie be only 70 minutes long?

What Did the Lady Forget? contains a disturbing burst of domestic violence. But the husband soon regrets it, and Ozu and his screenwriter Akira Fushimi develop the crisis in way that keeps shifting our judgment about what characters learn from the incident.

A distressed marriage

In a parallel situation in the “remake,” The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice, the husband remains calm in the face of his wife’s criticism. Mokichi is far from a paragon (he’s a phlegmatic workaholic, he’s out of touch with young folks and urban culture), but at home he’s quiet and apologetic. When Taeko complains about his table manners, he tries gently to explain why he slurps his rice.

Daniel Raim’s short on the Ozu-Noda collaboration concentrates on the planning of An Autumn Afternoon (1962), well-documented in Donald Richie’s Ozu. But we also have some records of their work routine on Green Tea. Ozu kept no fewer than five notebooks that year, sometimes recording the same event in two or more.

On 20 January, he notes that he and Noda are “bringing back a problematic script.” That’s because the original Flavor of Green Tea over Rice was refused by censors in 1940. In early 1952 Ozu was in the process of moving to Kamakura, so the two men’s collaboration took place in inns, Noda’s home, and the studio. One notebook logs Ozu’s production schedule, while others are more personal.

Ozu’s films from the 1950s on were typically planned in the winter, shot in spring and summer, and premiered in the fall, as if he were determined to document each year’s good weather. Ozu and Noda began writing Green Tea on 29 February and finished on 1 April, sometimes preparing three scenes a day. After consulting with Shiro Kido, the studio head, they revised the script. Ozu’s efficiency in planning every scene and sketching every shot allowed production to proceed fast. The crew began shooting on 7 June, in an office set. They finished on 13 July (“Finally, rest!”) and The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice premiered on 1 October.

Pretty intensive work. But you wouldn’t know it from the companion notebooks. Among chronicles of naps, baths, social gatherings, changing weather, baseball games, and bar-hopping with friends, how did they get any work done? Above all there’s Ozu’s careful record of his alcohol intake (“drank until 2 AM”). A stomach ache makes him think he might have an ulcer. “I must resolve not to drink too much. And stick to it!” Today we would call him a high-functioning alcoholic. “With the whisky I drank this morning and the shumai I brought back from Tokoen, I wasn’t at all hungry tonight.”

As in his films, the everyday and the unusual get equal treatment. While staying at one inn, he calmly observes the arrival of a woman’s baseball team. And he remained a cinephile. He’s happy to interrupt an evening of dining and drinking to go see William Dieterle’s September Affair (1950).

The film that resulted, I suggest in the supplement, modulates between satire and a generous comedy that gives the main characters, no matter their failings, moments of warmth and dignity. With a light hand Ozu summons up narrative parallels, and he spotlights the split between men’s culture and women’s culture. A troubled marriage is given due weight, but it’s saved by graciousness, as when (above) Mokichi rescues Taeko’s sleeve from the water in the sink.

Ozu carries the humor down to the fine grain of technique, teaching us to play a private cinematic game in which the characters participate all unawares. The Criterion creative team has ingeniously used split screens to help me show the evolution of stylistic patterns across the film. Shedding my Mr. Rogers sweater for a sport coat, I try to crack the mystery of those eerie tracking shots. Like the situations and the dialogue, these barely moving images ought to make you smile.

Thanks to producer Elizabeth Pauker and her colleagues at Criterion, especially Peter Becker and Kim Hendrickson. Thanks as well to Erik Gunneson and James Runde here at UW–Madison.

Ozu’s diaries of shooting The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice are available, with helpful annotations, in Yasujiro Ozu: Carnets 1933-1963, trans. Josiane Pinon-Kawataké (Editions ALIVE, 1996), 267-318.

My book, Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, is available for free here. Color pictures and everything! But be patient; it’s big and takes a while to download. There are many entries on Ozu and Donald Richie elsewhere on this site.

What Did the Lady Forget? (1937).

The raptures of rigor: Roy Andersson’s ABOUT ENDLESSNESS at Venice 2019

About Endlessness (Roy Andersson, 2019).

DB here:

In the midst of the frenzy of fast cutting in films of the 1990s, a few directors reminded us of the virtues of simply putting your camera on a tripod and letting the action unfold in front of it. Abbas Kiarostami, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Kitano Takeshi, Tsai Ming-liang, and several other filmmakers reminded us that the fixed camera and long take, i.e. the “theatrical” cinema so despised in the 1920s and 1930s, still harbored great expressive resources.

It’s a lesson we have to keep learning–with Warhol and Tati in the 1960s, Akerman and Duras and Angelopoulos in the 1970s, Iosseliani in the 1980s, and not least with one of the greatest exponents of the tendency, Manoel de Oliveira. His 1963 film Rite of Spring initiated his persistent, endlessly inventive exploration of the tableau shot. Doomed Love (1978; briefly discussed here) is a superb example; Francisca (1981) is another, and we were lucky to catch a superb restoration on display in the Venice Classics section. I hope to write about it soon!

After four years of production, Roy Andersson’s Songs from the Second Floor was released in 2000 and established his distinctive approach to the tableau tradition. Since then he has made only three features, the most recent of which played in competition at Venice 76. Of course we had to see it, and to visit his press conference.

This is visionary cinema of a unique kind.

Landscapes of unhappiness, minor and major

Start with some brute facts. About Endlessness runs only seventy minutes (without credits), and it consists of 32 one-shot scenes. As in Andersson’s other films since 2000, most scenes stand alone, without narrative connection to others.

Some are bare-bones situations, as when a young man watches a young woman watering a plant, or when a father ties his little girl’s shoe in a rainstorm. Others unfold a dramatic crisis. A man bursts into tears on a city bus, complaining that he doesn’t know what he wants. A dentist, put off by a patient’s yowls of pain, simply walks out of the consultation and ends up in a bar.

Some shots draw on our knowledge of a broader story, as when Hitler stalks into one chamber of his bunker and his lieutenants, exhausted by the bombardment, sporadically salute him. He hardly seems to notice. A few tableaux present a recurring thread, like minimalist running gags. A man recognizes a schoolmate, but wonders why the man won’t greet him. A priest feels himself losing his faith, gets drunk while celebrating mass, and consults a doctor for advice. And one recurring image shows a woman cradled in a man’s arms floating in the sky–at one point drifting over the ruins of the bombed Cologne of World War II.

What makes Andersson’s cinema so fascinating is his effort to design intricate, gradually unfolding compositions that harbor powerful emotional expression. Dialogue is at a minimum; objects are arranged with the precision of still lifes. His people are often doughy and plodding, with hangdog expressions and complexions like pumice, living in a world dominated by grays and pastel browns. His movies reveal how many shades of beige there can be.

The grandeur of the distant framings accentuate the impotence of the characters. These sad creatures are caught in strict, unsympathetic perspective, all sharp angles and endless vistas. They stand exposed by flat, minimally sculptured lighting. “I avoid shadows,” he explained at the press conference. “I want to make pictures where people can’t hide. A light without mercy.”

The same mercilessness is seen in the settings, which may look fairly naturalistic but are wholly artificial. Andersson uses miniatures, background painting, and digital effects to create his picture-book landscapes. Streets, cities, train platforms are all the product of years of preparation. Like Tativille in Jacques Tati’s Play Time, Andersson’s sets create a beguilingly realistic version of a wholly fake city.

The sets are calculated to make sense from a single vantage point, as Renaissance paintings are. In a shot like the first one below, moving the camera would reveal the forced-perspective buildings outside.

Some of these landscapes are as eerie as de Chirico’s, but without any of the sensuous shading.

Which means that posture, gesture, and objects near and far have to carry the drama, however anecdotal it may be. The man who thinks his old friend has snubbed him tells us that the friend has a Ph.D. His wife consoles him (after all, they’ve been to Niagara Falls), but he’s still anxious. His puzzled fretfulness is carried by his slumped bearing, his plaintive expression, and his clinging to his slotted spoon. Meanwhile we hear his pasta simmering ever more loudly in the kettle in lower frame right, a light objective correlative to his annoyance.

Andersson teases us by letting us imagine how a micro-story might unfold. In a cafe, a woman sits alone, with no drink in front of her. She’s in the classic posture of waiting, A man eats dinner behind her (his cutlery clinks) and an empty table on far right bears the traces of another customer. In comes a large, lumpish fellow brandishing a bouquet. He hesitantly asks for Lisa Larsson. So it’s a rendezvous?

Nope. A bald man enters from frame left bearing two beers.

The lady doesn’t admit to being Ms. Larsson. Maybe she really isn’t, or maybe she found a better date. In any case, the newcomer turns and leaves, a bit sadly. Of course, there’s always the possibility that the absent customer on the right was his date. We, and he, won’t know.

Note, in passing, Andersson’s use of classic staging techniques. Tableau cinema needs to guide our attention through pictorial tactics such as central placement, frontal positioning, and patterns of blocking-and-revealing. By giving the bald man a central position in the format and letting him mask our view of the man eating in the corner, Andersson makes sure we’ll register the confrontation between him and the intruder.

Most of the tableaux are accompanied by a brief voice-over, a woman saying, “I saw…” followed by a single-sentence description of the action. Andersson claims to see her as a bit like Scheherazade, but she has as little commitment to a full story as he does. Her narration provides very little judgment on the scene but does supply a bit of information–often grim, as when we learn that a busker lost his legs in combat.

Indeed, war is a recurring motif in the film, making it bleaker than any of the other Andersson films I recall. Now the minor miseries and absurdities of modern life sit along a continuum of death and destruction. A sequence of spontaneous dance here, a father’s awkward love for his daughter there–these don’t wholly compensate for a wartime execution or the bombing of Dresden. The gags are fewer now, and Andersson’s fantastical but stubbornly tangible cities have never looked more oppressive. The idea of endlessness stretches in many provocative directions: the infinite vistas of city and sky, the pinpricks of guilt and frustration in everyday life, the obscene endlessness of war. Lucky are those who can in a gentle embrace float above it all.

Andersson’s last film, A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence, won the Golden Lion for Best Film in Venice in 2014. Maybe this one will too? It’s one of the best new films I’ve seen here this year. More on the others, in later entries!

Thanks to Paolo Baratta and Alberto Barbera for another fine festival, and to Peter Cowie for his invitation to participate in the College Cinema program. We also appreciate the kind assistance of Michela Lazzarin and Jasna Zoranovich for helping us before and during our stay.

We’ve written bits on Andersson’s films elsewhere in our blog entries. See our entries on tableau staging for lots more on how this stylistic approach works. I discuss the technique as well in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging.

To go beyond our Venice 2019 blogs, check out our Instagram page.

About Endlessness (2019).

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in paperback: Much ado about noir things

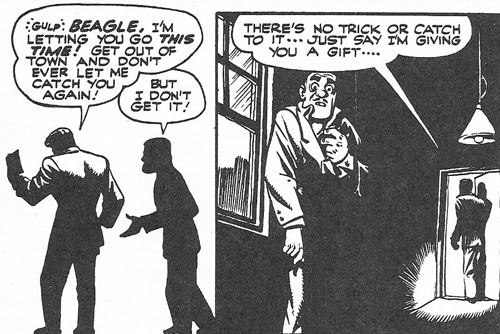

From “The Killer,” Spirit Comics (8 December 1946), by Will Eisner and studio.

DB here:

This is my final effort to cram my latest book down the resisting gullet of the reading public. Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling has just come out in paperback and I’ve been using our blog to trace out some relevant ideas that surfaced in recent books and DVD releases. The first entry dealt with some general issues, the second with popular culture’s drive toward variation, the third with craft and auteurism. This one has murder on its mind.

Noir as mystery and mystique

Sorry, Wrong Number (1948).

Crime looms large in Reinventing Hollywood. But I forsake the usual category of film noir. It didn’t exist as a concept for the filmmakers or audiences of the day. It’s the creation of critics, first overseas and then, much later, here at home. That doesn’t make the category invalid, though. Many art-historical categories (Baroque, Gothic) are later inventions, and those can be illuminating. Still, I think we gain some understanding if we situate our inquiry, for a time at least, at the level of what people seemed to be trying to do at the time.

Put it another way. By focusing on noir as the model of Forties narrative, we miss the ways in which the films we pick out under that rubric participate in wider trends. We miss, for instance, the new importance of mystery in all plotting of the period.

In the 1930s, mystery was mostly confined to detective stories. Think of your prototypical 1930s movie; it’s unlikely to have a mystery at its center. (Okay, maybe we’re curious about the identity of Oz the Great and Powerful.) In the 1940s, though, filmmakers began to scatter mystery devices into other genres. Mystery became a central storytelling strategy for personal dramas (Citizen Kane, 1941; Keeper of the Flame, 1943), romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan, 1945), war films (Five Graves to Cairo, 1943), social comment films (Intruder in the Dust, 1949), and domestic melodrama (Mildred Pierce, 1945; The Locket, 1946; A Letter to Three Wives, 1948). Some of what we call noir is part of this trend.

Over the same period, a fairly minor genre got promoted. Psychological thrillers can be traced back to Gothic novels and sensation fiction, but they became a distinct part of crime literature in the 1930s. They became an important genre for cinema in the 1940s, and so Reinventing Hollywood devoted a chapter to films like The Spiral Staircase (1945) and Sorry, Wrong Number (1948).

These aren’t canonical “noir” films, at least if your notion of noir stems from hard-boiled fiction. Some rely on the guilty-party plot exemplified in C. S. Forester’s novel Payment Deferred (1926), Patrick Hamilton’s play Rope (1929), and Anthony Berkeley Cox’s novel Malice Aforethought (1931). Less famous but just as interesting is the “woman-in-peril” thriller.

This was an upmarket version of romantic suspense novels associated in earlier decades with Mary Roberts Rinehart and Mignon Eberhart. Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938), one of the top-selling books of the 1940s, lifted the genre to respectability. Revisiting traces the wide-ranging variations that followed in film, fiction, and theatre. (An early draft of that chapter is elsewhere on this site.) Mystery is central to this subgenre. Who is endangering the protagonist? What are the real motives of the people around her, especially her lover or husband? Are her friends complicit? How will she escape?

The gynocentric thriller remains powerful in popular literature today. We’re currently in a rapid-fire cycle of it, typified by the work of Laura Lippman and Gillian Flynn. Some of the books have come to the screen: Gone Girl (2014), The Girl on the Train (2016), and A Simple Favor (2018). The HBO series Big Little Lies (2017-on), turns a fairly satiric domestic-suspense novel into a heavier exploration of spousal abuse. I’ll be writing more about this cycle later (and giving a paper on it this summer), but let me note two recent examples. One takes its Forties sources for granted, the other flaunts them. Both are coming to a screen near you.

In Alex Michaelides’ new novel The Silent Patient Alicia Berenson, an emerging painter, is found guilty of shooting her husband. Because she seems in permanent shock and refuses to speak a word, she’s confined to a mental institution. There the ambitious young psychotherapist Theo Faber tries to ferret out why she remains silent. The narration alternates, Gone Girl fashion, between Theo’s first-person investigation and Alicia’s diary of events leading up to the killing.

It’s a spare tale narrated in a clumsy style that doesn’t distinguish the two voices. And it reminds us that if you become a character in a novel or movie, don’t get into a car. But it does show the persistence of Forties strategies.

There’s the Crazy Lady (recalling Shock of 1946, above, and Possessed of 1947, as well as John Franklin Bardin’s 1948 novel Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly). There’s the sinister side of the artworld, with a predatory dealers, a demented painter, and portraits that suggest sinister psychic forces. There’s the apparently rational man who becomes obsessed with a woman in a picture (as in Laura, 1944). There’s a mythological parallel to the heroine (here, Alcestis; in The Locket of 1946, Cassandra). There’s the therapeutic motif of a doctor falling in love with a mentally disturbed patient (Spellbound, 1945). And there is, of course, a twist depending on suppressive narration.

The Silent Patient quietly absorbs these Forties conventions, with virtually no mention of the tradition. At the other extreme sits the self-conscious geekery of A. J. Finn’s The Woman in the Window. In an earlier entry on the eyewitness plot I swore I wouldn’t give space to this novel, largely because I resist people swiping titles of movies I admire. But after alert colleague Jeff Smith told me, “It’s as if he read your Forties book,” I figured I could break my rule.

Indeed this eyewitness thriller relies on a great many narrative tricks from the period. We get a Crazy Lady, dreams, hallucinations, an unreliable narrator, the drama of doubt, flashbacks within flashbacks (with the revelatory one coming at the end), and a Gothic climax punctuated by lightning bursts. Also, inevitably, a car crash.

The book’s epigraph comes from Shadow of a Doubt, and the pages that follow are littered with references to 1940s movies. Our homebound heroine lives in thrall to DVDs and TCM, though her impending fate gives a new meaning to “Netflix and chill.”

The Woman in the Window is soaked in contemporary movie-nerd culture. The heroine updates Jeffries’ tech gear in Rear Window by shooting video footage of the suspects across the way. She mentions Kino and Criterion discs, and even refers to “diegetic sound.” (Has she read Film Art: An Introduction?}

Like The Silent Patient, Finn’s book illustrates how much modern thrillers owe to Forties movies. But it also exemplifies how noir has become a kind of brand and a signal of hip tastes. Maybe that’s a reason to back off the label for a while.

Noir in brief

But let’s not back off too far. Any student of 1940s Hollywood can learn a lot from the vast literature on noir. The most recent item to cross my desk is James Naremore’s Film Noir: A Very Short Introduction. (It’s due to be published in April.) As you’d expect, the author of More Than Night will bring a wide-ranging expertise to a compact survey of books, films, and ideas.

I wish I could’ve signaled his study of “the modernist crime novel” in my book. I emphasize how modernist narrative techniques shaped middlebrow fiction, which in turn made their way into movies. Naremore points out some more direct affiliations:

I wish I could’ve signaled his study of “the modernist crime novel” in my book. I emphasize how modernist narrative techniques shaped middlebrow fiction, which in turn made their way into movies. Naremore points out some more direct affiliations:

In the previous two decades modernism had influenced melodramatic fiction of all kinds, and writers and artists with serious aspirations now worked at least part time for the movies.

When the trend reached a peak in the early 1940s, it made traditional formulas, especially the crime film, seem more “artful.”. . . And yet there was a tension or contradiction within the Hollywood film noirs of the 1940s. Certain attributes of modernism—its links to high culture, its formal and moral complexity, its frankness about sex, its criticism of American modernity—were a potential threat to the entertainment industry and were never fully absorbed into the mainstream.

Naremore goes on to discuss several influential writers—Hammett, Greene, Cain, Chandler, Woolrich—and key films such as The Maltese Falcon and Double Indemnity as examples of “tough modernism” in fiction and film. One of the virtues of the book is its sweep: it covers nearly eighty years of noir on the page and on the screen. Like everything else Jim writes, it’s essential for film fans and researchers. His recently inaugurated webpage displays his range of interests.

The Big Nutshell

Did the 1940s give us the habit of calling a movie The Big Whatever? True, we had The Big Parade in 1925 and The Big Broadcast of 1935 but it seems that the next decade was quite big on bigness. Apart from The Big Sleep (1946), we had The Big Store (1941), The Big Street (1942), The Big Shot (1942), The Big Clock (1948), The Big Steal (1949), and The Big Cat (1949). Many episodes of Dragnet, as both radio show and later TV program, had The Big . . . as their title prefix.

So I wish I’d known about David W. Maurer’s 1940 book The Big Con: The Story of the Confidence Man. It’s hard-boiled reportage in the vein of Courtney Riley Cooper’s flinty Here’s to Crime (1941). Maurer introduces us to a repertoire of grifts that will nimbly extract dough from the mark (aka the fink).

So I wish I’d known about David W. Maurer’s 1940 book The Big Con: The Story of the Confidence Man. It’s hard-boiled reportage in the vein of Courtney Riley Cooper’s flinty Here’s to Crime (1941). Maurer introduces us to a repertoire of grifts that will nimbly extract dough from the mark (aka the fink).

There are small-scale operations (the short con), as well as complex ensemble efforts using, naturally, the Big Store (fitted out with a fake racetrack wire). The scam shown in The Sting (1973) is a Big Store con. Maurer provides a sociological study as well: “Confidence men, like civilians, mate once or more (usually more) in their lives.” I don’t know exactly how I would have worked in a footnote to The Big Con, but I would have tried.

While Maurer was writing The Big Con, something more sinister was going on. In her four-story farmhouse, Frances Glessner Lee was laboring over the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death.

These were crime scenes presented on an itty-bitty scale. Little corpses—stabbed, drowned, hanging—are surrounded by the most banal furnishings. Exquisitely miniaturized chairs, rugs, lamps, beer bottles, calendars (“Corn Products Sales Company”) surround the pathetic figures. A woman stares up from a bathtub alongside tiny towels, hanging socks, and even a simulacrum of tap water endlessly gushing. Frank Harris is found drunk and crumpled in front of a saloon; the next scene shows him dead in his cell. What happened?

Ms Lee, a wealthy devotee of criminal investigation, recreated these grim tableaus as audio-visual aids for police training. Exactly how useful they were as pedagogy isn’t clear. The imagery recalls classic mysteries, and it’s not surprising that Lee was a friend of Erle Stanley Gardner, creator of Perry Mason. Yet her scenes have a creepy melancholy quite alien to Golden Age puzzle plots. As a testimony to the 1940s fascination with aestheticized homicide, they’re close to Weegee or Chester Gould. But they’re rendered as fastidiously as a Joseph Cornell box. I see in the Nutshells the populist Surrealism that led, at the other end of the scale, to Wisconsin’s House on the Rock (which began construction in the 1940s).

Corinne May Botz is the David Fincher of the Lee oeuvre. Her camera in The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death gets deep into the scene and renders the most upsetting images with a cold precision that matches the staging. These bits of cloth and plastic, sculpted and arranged with maniacal precision, make death at once childish and bleak. Blown up in Botz’s photos, the scenes radiate anxiety and menace. Dollhouse noir?

Frozen movies

Will Eisner, “Beagle’s Second Chance,” Spirit Comics (3 November 1946).

In Reinventing Hollywood I suggest that techniques we find in the films have their counterparts in popular novels, short stories, plays, and radio shows. Artists in these media were also exploring shifting time frames and viewpoints, voice-over narration, and other devices. I called it the multimedia swap meet, where mass-culture wares were available for use and revision (thanks to the variorum).

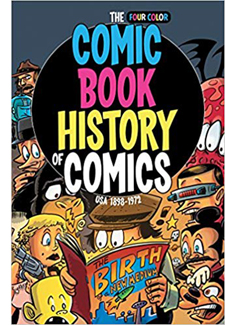

A Christmas gift from alert programmer Jim Healy reminded me of my neglect of a major medium. Jim gave me the wondrous Comic Book History of Comics by Fred Van Lente and Ryan Dunlavey. Each teeming page is jammed with facts, figures, and follies from the history of American comic art, illustrated with frantic drawings and exploding panels. As a comics fan, I should have mentioned how the narrative strategies I traced in film have counterparts in many of the trends Van Lente and Dunlavey cover.

A Christmas gift from alert programmer Jim Healy reminded me of my neglect of a major medium. Jim gave me the wondrous Comic Book History of Comics by Fred Van Lente and Ryan Dunlavey. Each teeming page is jammed with facts, figures, and follies from the history of American comic art, illustrated with frantic drawings and exploding panels. As a comics fan, I should have mentioned how the narrative strategies I traced in film have counterparts in many of the trends Van Lente and Dunlavey cover.

One example is shown at the top of today’s entry: an effort toward optical POV in Will Eisner’s The Spirit. Eisner renders almost all the panels on that page as subjective. At the time, films were exploring the same idea for certain scenes (e.g., Hitchcock’s work), for long stretches (Dark Passage, 1947), and for nearly the whole movie (The Lady in the Lake, 1947).

Of course Eisner’s Spirit tales evoke noir visuals as well–and become more noirish as the Forties go along, at least to my eye. Other cartoonists, particularly Chester Gould and Milton Caniff, push toward the steep compositions and chiaroscuro lighting we find in the films. I’m inclined to say that the movies got there first; I argued in The Classical Hollywood Cinema that noirish visual designs were often recruited for scenes of crime and mystery in the 1920s and 1930s. (A blog entry found examples from the 1910s.) I suspect that artists of the comics adopted those schemas when they started to make cops-and-robbers strips. By the 1940s, though, with Eisner and others, the visual dynamism pushed beyond what we see in most films. Except, as always, for Welles: Mr. Arkadin seems an Eisner comic brought to life.

Vanilla noir

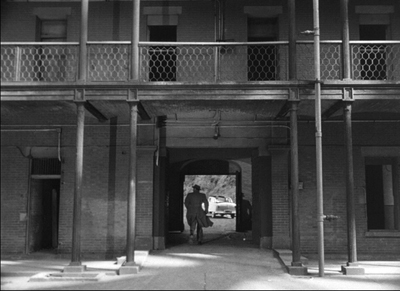

The Man Who Cheated Himself (1950).

Noir is a tricky category because it’s a cluster concept. It can refer to visual style, matters of narrative or narration (haunted protagonists, plays with viewpoint), genre (drama, not comedy), and themes (betrayed friendships, dangerous eroticism, male anxiety). Take away one dimension and you might still be inclined to call the movie a noir. Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956) has a noir plotline, but its disarmingly drab images mostly lack the low-key look. And maybe someone would call Murder, He Says (1945) a noir comedy.

A good example of mild noirishness is The Man Who Cheated Himself (1950), now made available in a handsome UCLA restoration from Flicker Alley. Ed Cullen is a tough homicide cop lured by a rich woman into a murder plot. He helps her cover it up, but his younger brother, just starting out in the police force, gets too close to solving the case.

The action climaxes in a vigorous showdown in San Francisco’s Fort Point compound. Director Felix Feist, who gave us the better-known The Devil Thumbs a Ride (1947) and The Threat (1949), exploits this impressive location.

Most of the film is more soberly shot, but one long take of an interrogation uses the typical Forties image: a low-slung camera, figures deployed in depth and rearranged as the pressure intensifies.

The Blu-ray release includes a well-filled booklet and two excellent documentaries. Brian Hollis pinpoints the use of San Francisco locations and has interesting comparisons with Vertigo. A second short provides background on the participants and the film’s production, with shrewd remarks on the film’s casting by Eddie Muller. I was also pleased to see that the film, full of smokers, includes Hollywood’s favorite brand of the Forties, Chesterfields.

From Sunrise to Moonrise

Moonrise offers a different negotiation of noir conventions. The Criterion Blu-ray release, produced by Jason Altman, makes this 1948 classic available in a much better version than I’ve seen before. I discuss the opening in Reinventing, taking it as an example of a deeply subjective montage sequence, and I posted the clip online as a supplement.

After knowing the film for years, I expected that the 1946 source novel by Theodore Strauss would have some of the delirious prose we get in Steve Fisher’s I Wake Up Screaming (1941). Strauss wrote film journalism for the New York Times, so it seemed likely he would incorporate some of the pseudo-cinematic techniques of voice-over, subjectivity, and the like, as do other crime novels I mention in Reinventing. Instead, the storytelling is standard hardboiled. Here, for instance, is Strauss sketching the buildup of grudges that leads Danny to kill his long-time nemesis Jerry:

Every time his fist smacked into Jerry’s soft side or smashed Jerry’s mouth against his teeth Danny knew he was paying back. He was paying back for that first day at grade school when he was the new kid and Jerry had whipped him with the whole playground backing him. He was paying back for the night Jerry and his gang took him into the alley and tarred him because Jerry said he’d squealed to the principal. He was paying back for the scar on his shoulder left by Jerry’s cleats in scrimmage seven years ago. He was paying back for every dirty crack jerry had ever made about him or his father in public or private, to his face and behind his back. Paying back. Paying pack good.

Borzage’s movie turns this compact backstory into something much more hallucinatory.

The montage intersperses a hanged man with vignettes of his son being bullied from childhood on. First the rippling miasma seen under the credits gives way to blobs appearing as if in reflection. The camera reveals them as mysteriously projected on a wall (or is it a screen?), and then it picks up feet stalking toward the gallows.

Witnesses are revealed standing in the rain, and the camera rises to show the execution as shadows flung onto the wall/screen.

It seems more of a feverish childhood vision of the hanging rather than any veridical presentation. Cut to a view of a baby with a doll dangling over his crib. This traumatic image is followed by scenes of jeering schoolboy cruelty. (“Danny Hawkins’ dad was hanged!”)

It’s a murky, delirious passage. Its tactility, with mud smeared into Danny’s face, admirably prepares us for a film steeped in swamp water and dank foliage. Here, as elsewhere, 1940s filmmakers are rehabilitating the expressionist devices of late silent film.

The rest of the film doesn’t present such overpowering imagery, but by continuing the opening sequence in the present, following Danny as he drifts past a dance pavilion, the narration makes Danny’s fight with the bully Jerry a furious culmination of all the indignities he’s suffered.

The plot traces a familiar Forties trajectory, following a flawed but not despicable man driven to conceal a crime. In the course of his evasions, he tries to make a life with a compassionate woman. There are many wonderful scenes, including a suspenseful ride on a ferris wheel and a lyrical dance in an abandoned mansion. The lawman tracking Danny comes off as gentle and compassionate. The rippling imagery of the opening recurs in the background of shots, as if the swamp were waiting to claim Danny. As Hervé Dumont points out in a bonus conversation with Peter Cowie on the Criterion disc, all this gloom eventually clears to arrive at a sun-drenched resolution quite different from your typical noir payoff. (Though it’s faithful to the novel, as indeed most of the film’s plot is.)

This time around I was struck by the delicacy of Frank Borzage’s direction in the less flamboyant passages. This master of silent cinema knows how to let a pair of hands show distress, an effort toward tenderness, and then rejection.

Borzage was most famous for his feelingful melodramas Humoresque (1920), Seventh Heaven (1927), and Street Angel (1928). He made those last two features at Fox while F. W. Murnau was there, and it’s probably not too much to see the brackish mist of Borzage’s 1948 film as reviving the look of the nocturnal countryside scenes of Sunrise (1927).

Some shots might almost be homages to Murnau’s film.

The compositions remind us that the 1940s deep-focus style isn’t far from the wide-angle imagery Murnau pioneered in the silent era. Although Strauss’s novel gives the Borzage film its title, we’re free to imagine Sunrise (in which the moon figures prominently) as a prefiguration of Moonrise, in which we never see the moon rise.

A final thanks to all who have picked up a copy of Reinventing Hollywood. Apart from its arguments, I hope that it steers you toward some new viewing pleasures.

Film rights to The Silent Patient, whose author has an MFA in screenwriting, have been sold to Annapurna and Plan B. Amy Adams is set to star in The Woman in the Window, from Fox 2000.

It seems that The Woman in the Window owes a debt to more than movies. A detailed profile of its author in The New Yorker suggests that exposure to Highsmith’s Ripley novels at an impressionable age can have serious consequences, especially if you wind up among the Manhattan literati.

Robert C. Harvey offers a careful analysis of Eisner’s Spirit story, “Beagle’s Second Chance,” in The Art of the Comic Book: An Aesthetic History (University Press of Mississippi, 1996), 178-191. Interestingly, the chapter is titled, “Only in the Comics: Why Cartooning Is Not the Same as Filmmaking.”

The most comprehensive book on Borzage’s career I know is Hervé Dumont’s de luxe edition Frank Borzage: Sarastro à Hollywood (Cinémathèque Française, 1993). An English translation was published in 2009.

The following errors are in the hardcover version of Reinventing Hollywood but are corrected in the paperback.

p. 9: 12 lines from bottom: “had became” should be “had become”. Urk.

p. 93: Last sentence of second full paragraph: “The Killers (1956)” should be “The Killing (1956)”. Eep. I try to do the film, and its genre, justice in another entry.

p. 169: last two lines of second full paragraph: Weekend at the Waldorf should be Week-End at the Waldorf.

p. 334: first sentence of third full paragraph: “over two hours” should be “about one hundred minutes.” Omigosh.

We couldn’t correct this slip, though: p. 524: two endnotes, nos. 30 and 33 citing “New Trend in the Horror Pix,” should cite it as “New Trend in Horror Pix.”

Whenever I find slips like these, I take comfort in this remark by Stephen Sondheim:

Having spent decades of proofing both music and lyrics, I now surrender to the inevitability that no matter how many times you reread what you’ve written, you fail to spot all the typos and oversights.

Sondheim adds, a little snidely, “As do your editors,” but that’s a bridge too far for me. So I thank the blameless Rodney Powell, Melinda Kennedy, Kelly Finefrock-Creed, Maggie Hivnor-Labarbera, and Garrett P. Kiely at the University of Chicago Press for all their help in shepherding Reinventing Hollywood into print.

The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death: Parsonage Parlor, by Lorie Shaull.

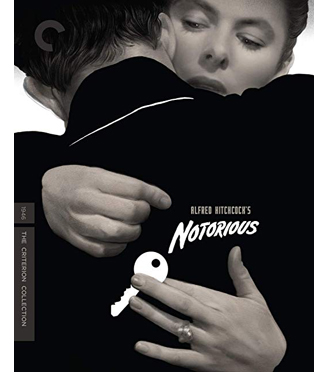

NOTORIOUSly yours, from Criterion

DB here:

Notorious was the subject of the first piece of criticism I published. The venue was Film Heritage, one of those little cinephile magazines that flourished, if that’s the word, in the 1960s. My appreciative essay came out in 1969, as I was finishing my senior year in college.

I haven’t dared to look back at it. Actually, I’m not sure I have a copy. The soft-focus imagery of memory tells me that some things that would preoccupy me in the future–interest in narrative structure, style, point-of-view, the spectator’s engagement with mystery and suspense–are there, though in ploddingly naive shape.

Since those days Hitchcock has always been with me. He’s been the subject of articles and blogs and many, many classroom sessions. Now, thanks to the Criterion collection, I’ve had a chance to revisit Notorious.

The new Blu-ray edition includes a dazzling array of extras. Many were available on the now out-of-print 2001 Criterion DVD: two audio commentaries featuring Rudy Behlmer and Marion Keane, the Lux Radio Theatre adaptation starring Joseph Cotten, and newsreel footage of Hitchcock and Bergman. Added to that earlier material are an interview with Donald Spoto, a video essay on technique by John Bailey, a 2009 documentary about the film, a study of the film’s preproduction by Daniel Raim, and a print essay by Angelica Jade Bastien. Since I just got my copy and wanted to tell you about it, I haven’t had time to plunge into all of this, but the samples I’ve checked are exhilarating.

The new Blu-ray edition includes a dazzling array of extras. Many were available on the now out-of-print 2001 Criterion DVD: two audio commentaries featuring Rudy Behlmer and Marion Keane, the Lux Radio Theatre adaptation starring Joseph Cotten, and newsreel footage of Hitchcock and Bergman. Added to that earlier material are an interview with Donald Spoto, a video essay on technique by John Bailey, a 2009 documentary about the film, a study of the film’s preproduction by Daniel Raim, and a print essay by Angelica Jade Bastien. Since I just got my copy and wanted to tell you about it, I haven’t had time to plunge into all of this, but the samples I’ve checked are exhilarating.

Hitchcock is the most teachable of classic directors. His strategies are just obvious enough for beginners to notice them, but they always open up new directions for more experienced viewers.

I reconfirmed all this when I decided to devote a chapter of Reinventing Hollywood to Hitchcock and Welles. These two masters decisively influenced the 1940s, the period I was considering. But they were in turn influenced by the crosscurrents in their filmmaking community. And they came to epitomize, for me, the artistic richness of what Hollywood could do in this golden age.

In addition, I tried to make the case that they carried storytelling strategies typical of the period into later eras. I declared, in a burst of geek recklessness:

Vertigo constitutes a thoroughgoing compilation/revision of 1940s subjective devices. The obsessive optical POV shots of Scottie trailing Madeleine give way to a dream tricked out with pulsating color, abstract rear projetion, stark geometric patterns, and animated flowers. . . . Along with all the other echoes–portraits, therapy for a traumatized man, voice-over confession, point-of-view switches, the hint of a reincarnated or time-traveling woman–the powerful probes of subjectivity make Vertigo, though released in 1958, one of the most typical forties movies.

But then so is Notorious, a film I had little to say about in the book. So I’m glad that Criterion’s invitation to contribute a 30-minute short on this new release led me back to a film I’ve loved for over fifty years.

Darned sophisticated, or dead

My supplement concentrates on the climax in Alicia’s bedroom and on the staircase of Sebastian’s mansion. Spiraling out from that sequence, I try to show how it’s the culmination of many storytelling strategies, from point-of-view editing to long takes. I also trace out something I didn’t fully realize until I researched the film’s reception: It was considered very sexy.

For one thing, Ingrid Bergman was associated with innocents, and her playing a promiscuous party girl (“notorious”) was a bit of spice. For another, Hitchcock’s earlier films, though they always had erotic overtones, didn’t really center on a passionate romance. His heroines didn’t convey much smoldering passion, despite all his prattle about glacial blondes thawing out fast. His darkly handsome protagonists (Maxim in Rebecca, Johnnie in Suspicion, Uncle Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt) are more steely than steamy. As for Joel McCrae in Foreign Correspondent and Bob Cummings in Saboteur, they seem virtual Boy Scouts. Only Spellbound, which introduces a psychoanalyst to ecstasy in the rangy form of Gregory Peck, seems a first stab at the sexual complications of Notorious. And the analyst is played, of course, by Bergman, radiant as soon as she takes off her glasses.

The 1940s had a well-established convention that a handsome friend of the family could rescue a wife from the predations of her husband (Gaslight, Sleep My Love) or other tormentor (Shadow of a Doubt). Film scholar Diane Waldman called this figure the helper male. In the second half of Notorious Devlin plays this role. The basic situation–a man stealing another man’s lawfully wedded wife–is pretty edgy in itself, especially since Sebastian is far more frankly in love with Alicia than Devlin is. I try to show that Hitchcock wrings new emotion from the convention by making the husband, trapped between his Nazi gang and his ruthless mother, sympathetic. Meanwhile, the helper male comes off unusually cruel, needling Alicia about the carnal bargain he plunged her into.

And then there’s all that snogging. The romance in Notorious is one long tease–between the characters, and between the screen and the viewer. The Los Angeles Times critic made it the basis of his lead:

Devlin and Alicia are all over each other, notably in the famous scene in her apartment. (Have they done The Deed? Obviously yes.) Their tight embrace, their constant pecking and nibbling and nuzzling as they float across the room, provoked a lot of notice. In the supplement I quote Dorothy Kilgallen, whom my oldest readers will remember from “What’s My Line?” on TV. She wrote this in Modern Screen:

So it makes a certain amount of sense for a power company to assume that incandescent stars can sell electricity, as below. In Toledo, too.

For this and other reasons, I’m happy to have a chance to revisit one of my very favorite Hitchcock films. I bet that you’ll enjoy seeing this stunning copy and immersing yourself in all the bonuses. Hitch is endlessly fascinating, and he’s one of the main reasons we love movies.

Thanks to Curtis Tsui, who produced the disc, as well as Erik Gunneson and James Runde here at UW–Madison, and all the New York postproduction team. Thanks as well to Peter Becker and Kim Hendrickson for all they do to keep Criterion at the top of its game.

Greg Ruth, designer of cover art for Criterion, explains his creative process on their site. More details on the release, with clip, are here.

The Los Angeles Times review comes from the issue of 23 August 1946, p. A7. The Kilgallen Modern Screen piece is available via Lantern, here. If you youngsters didn’t get her reference to Helen Hokinson, go here.

For another in-depth analysis of a single sequence, see Cristina Álvarez López & Adrian Martin’s Filmkrant video essay, “Place and Space in a Scene from Notorious.” They showed me things I had never noticed–more proof of the richness of Hitchcock World.

Cary Grant’s image was used to sell oil a few years before, as illustrated in this entry.

P.S. 21 January 2019: For more on the steamy side of Notorious, there’s “The Clinch That Filled 1,200 Seats,” at the redoubtable Greenbriar Picture Shows. Thanks to John McElwee for bringing it to my notice!

Better Theatres (24 August 1946).