Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

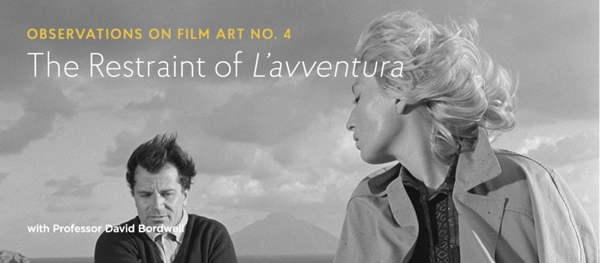

Going inside by staying outside: L’AVVENTURA on the Criterion Channel

DB here:

This month, our entry on FilmStruck’s Criterion Channel is a discussion of L’Avventura. This isn’t my favorite Antonioni movie, but it’s one I enjoy and admire—not least because of its striking originality of mise-en-scene. So that’s what I tackle in the Criterion entry.

The installment is here, and if you’re a subscriber you can watch it immediately. Otherwise, there’s a chance to sign up. If you’re not aware of FilmStruck, one of the great adventures in modern film culture, you can check on it here. (The Twitter feed is enjoyable even to non-tweeters like me.) Today, I want to flesh out my entry with some other comments. I hope they’ll be of interest even to those who aren’t signed on to the FilmStruck enterprise.

Two ways of doing deep

Le Amiche (1955).

During the 1950s, Antonioni displayed vigorous experimentation in visual style. Like many directors, he embraced the long take, usually in conjunction with camera movement. Within those parameters, he staged his action both laterally and in depth. But depth staging comes in many flavors.

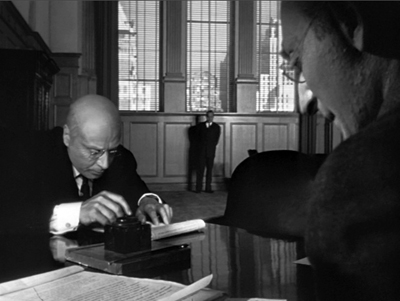

One is the aggressive deep-focus technique of Welles, with large heads or objects very close to the camera in the foreground. Here are two famous instances from Citizen Kane (1941).

This fairly extreme approach was picked up by some 40s and 50s directors, especially those interested in what came to be called film noir.

You can find somewhat mild versions of these compositions in early Antonioni, especially in cramped surroundings. A bus ride and a necking party in I Vinti (1953) bring forth some big foregrounds.

Despite occasional shots like these, Antonioni’s early work favors an alternative approach to depth, the one cultivated by Jean Renoir, Mizoguchi Kenji, William Wyler, and others. That approach doesn’t go for Citizen Kane baroque. It keeps the foreground plane fairly distant–say a medium-shot or further–and uses both lateral and fairly deep staging to multiply key points of interest in the shot. Less fancy than the Welles tradition, it allows more naturalistic blocking because it yields more playing space.

Go back to I Vinti, and we’ll find that most shots aren’t as thrusting as Welles’ images, largely because of their reliance on real locations and naturalistic lighting. The film tends to stages its long takes in mid-range, porous compositions. A two-minute shot of teenagers lounging at a cafe and plotting a murder is rendered in a gentle diagonal that spreads out multiple points of interest.

By the way: Why doesn’t anybody make shots like this any more?

One advantage is that while the packed Wellesian frame tends to make its actors assume fixed poses, the more open frames of the alternative can show more of actors’ bodies and develop gestures and other actorly bits. This happens in the I Vinti café scene, which depends on characters’ changing postures, along with the distraction of the annoying little girl blowing on drink straws.

Similarly, Antonioni’s first feature, the noirish romance Story of a Love Affair (1950) makes adroit use of the mid-range foreground. The famous single-shot, 360-rdegree scene between lovers quarreling on a bridge is a paradigm case of how location filming can be made rigorous and purposeful. A complex camera camera movement is coordinated with figures resolutely evading each other in constantly varied medium-shots.

Le Amiche (1955) continues down the same path, with characters alotted distinct pockets of the frame to expose their fleeting reactions.

But there’s now a more intricate choreography, as befits a plot with several story lines. A scene gathering the major characters at a cafe is a magnificent exercise in the Wyler manner, with heads meticulously spotted across the frame.

For years I was surprised that L’Avventura (1960) and its successors La Notte (1961) and L’Eclisse (1962) make less use of this sort of precise staging in depth. While the director’s style remains fluid and rigorously patterned, and powerfully exploits urban vistas, it relies more on editing. But looking again at L’Avventura for the Criterion Channel installment, I became convinced that he was exploring a new way to handle staging—one that built upon his mastery of Renoir-Wyler choreography.

From the back or from the front

When a film’s narrative harbors mysteries, they’re often a matter of plot. Something has happened that we don’t fully know about, and the business of the plot is to bring that to light, either in the short term or across the whole movie. In the detective film, there’s a mysterious crime that needs solving, and the clarification will typically come at the climax, when the malefactor (and the motive, and the means) will get revealed. Plot-centered mysteries are easily dismissed as superficial, but the great tradition of literary detection shows that they can be imaginative and gripping, while also exploring literary techniques in sophisticated ways.

There are also mysteries of character—not just whodunit, but something deeper. A narrative might induce us to ask what makes characters do what they do. This can result in fairly superficial probing, as in many psychoanalytic films of the 1940s, but it can, again, prod the storyteller to exploit some aspects of the medium that engage us. At the limit, mysteries of character can lead the narrative to explore the moods and motives of its people, bringing out contradictions of mind and action. Even a potboiler like Gone Girl not only reveals the rage bubbling beneath Amy’s perfect porcelain surface but explains that anger as a response to the Cool Girl role dictated by yuppie culture.

I usually don’t employ the distinction plot vs. character when I’m thinking about film narratives, but as a first approximation it points up the nuances of L’Avventura’s visual strategies. The film has, initially, a clear-cut plot-based mystery: What has led Anna to disappear? Is she dead, or lost, or simply escaping from the situation? This is, in a way, the bait luring us to pursue mysteries of character.

What, to start, does Anna want from her affair with Sandro? She seems alternately flirtatious, cynical, angry, and passionate. And assuming her disappearance wasn’t accidental, what impelled her to leave the party? As for Sandro, what sort of man is he? And why does he, with unseemly haste after Anna’s vanishing, seize Claudia and kiss her violently?

Claudia, for her part, seems to gradually accept her role as the Anna substitute. We’d expect her to be torn by her betrayal of her friend, and maybe she is, but we can’t be sure. With almost no backstory supplied for these people and no plunge into their inner lives through dreams, voice-over, subjective visions, and the like, we’re forced to read their minds and hearts on the basis of what they say and do. This is relentlessly behaviorist cinema.

Here’s where visual style kicks in, I think. Antonioni declared his interest in moving the Neorealist impulse from social observation to psychological revelation.

The neorealism of the postwar period, when reality was what it was, so intensely present, focused on the relationship between characters and reality. What was important was that very relationship, which created a cinema based on “situations.” . . . That’s why, nowadays it’s no longer important to make a film about a man whose bicycle has been stolen. . . . It is important to see what is inside this man whose bicycle was stolen, what are his thoughts, what are his feelings.

How to achieve this psychological penetration? Not through the sort of definite scene structure of a Hollywood film, a crisp slice of action that can be summed up in a story beat.

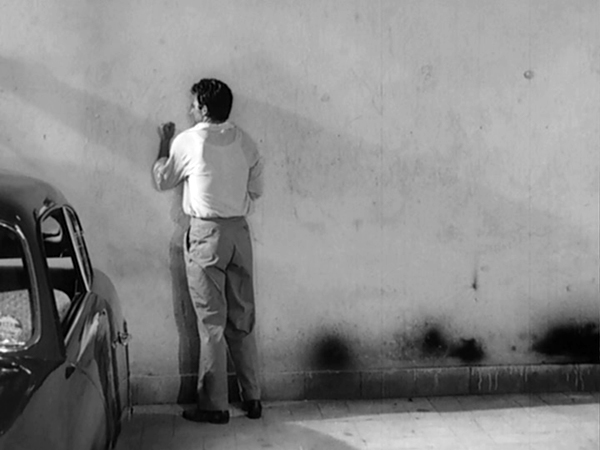

I believe it is much more cinematic to try and capture the thoughts of a person through an ordinary visual reaction, rather than enclose them in a sentence. . . . One of my concerns in filming is to follow the characters until I feel it is time to stop. . . When all has been said, when the main scene is over, there are less important moments; and to me, it seems worthwhile to show the character right in these moments, from the back or the front, focusing on a gesture, on an attitude.

Antonioni scenes, critics sometimes say, begin a bit before they start and end a bit after they stop.

You might expect from this emphasis on character psychology and the habit of lingering on a scene’s resonance would yield few mysteries. Yet what interests me in L’Avventura is the way in which it doesn’t allow us to “see what is inside” its characters. Perversely, having braked the dramatic momentum in order to probe character, Antonioni goes on to block our access to his people’s minds.

His visual strategies for doing this are many, and they’re flaunted in the film made just before L’Avventura. The witholding of character reaction is flamboyant in Il Grido (1957), maybe over the top.

L’Avventura‘s reticent pictorial strategies are more nuanced and naturalistic, and my FilmStruck contribution tries to chart them. For about the first hour of the film, Antonioni lets landscape overwhelms his characters, gives them equivocal facial expressions, refuses the full information of shot/reverse shot cutting, and at crucial moments simply makes his actors turn from the camera, denying us access to their emotional reactions.

What’s just as interesting, the second half of the film selectively returns to the techniques that were initially banned. It’s as if these more familiar image schemas–reverse shots, frontal close-ups, more marked facial reactions–have become suitable to the growing romance between Claudia and Sandro. Now the first hour’s stingy attitude toward psychological information is balanced by a greater degree of emotional exposure, especially on Claudia’s part. By the very end, the two broad strategies coexist uneasily, and some enigmas remain.

During the late 1960s Antonioni changed his style. He turned from deep-focus, wide-angle images to flat telephoto ones, and he began relying on a pan-and-zoom technique. These were partly responses to shooting in color and wider formats, I think, but they also offered the opportunity for a painterly look that he exploited in the films from Red Desert (1964) on. Fellini, Bergman, Visconti, and others took a similar path, as I tried to show in this early blog post.

In 1960 those developments were yet to come. It seems to me that the style of L’Avventura enhances the mysteries of plot and character in a unique and unsettling way. We get a visual surface that entrances us with its measured beauty and teases us with its calm opacity.

Thanks as usual to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and the Criterion team for including us in their FilmStruck enterprise.

My quotation from Antonioni comes from his essay “My Experience [1958],” in his book The Architecture of Vision: Writings and Interviews on Cinema (Marsilio, 1996), 7-9.

The L’Avventura discussion on FilmStruck is the fourth in our Criterion Channel series, “Observations on Film Art.” The others are Jeff Smith on the music of Foreign Correspondent, me on Sanshiro Sugata, and Kristin on landscape in Kiarostami. Some clip extracts can be found here and here. Jeff has amplified his installment with further comments on this blog, and I’ve done the same with Sanshiro , as today with L’Avventura. We introduce our collaboration in this entry. The Criterion introduction to us is here.

For more on Mizoguchi’s approach to depth staging, see this summary entry. There’s more on Wyler’s style here. I compare the two directors in this entry on sleeves. I discuss the broader shift from deep-focus techniques to pan-and-zoom ones in On the History of Film Style, Chapter 6.

I Vinti.

How LA LA LAND is made

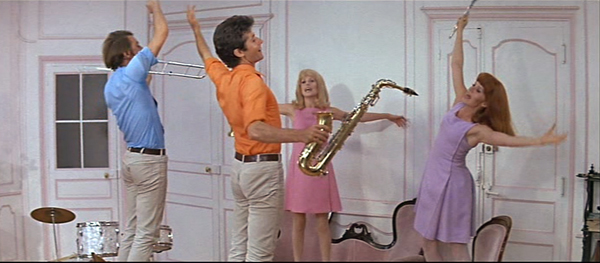

La La Land (2016).

The formal method is fundamentally simple. It’s the return to craft (masterstvo).

Viktor Shkovsky, 1923

DB here:

Not how it was made. We’ll get “The Making of La La Land” as a DVD bonus, and there are already behind-the-scenes promos.

No, this is about how it is made.

On this site, we mostly practice a criticism of enthusiasm. We write about what we like, or at least about films that intrigue us from the standpoint of history or aesthetics. Sometimes, what interests us intersects with a current controversy. Take La La Land.

Some of my cinephile friends disapprove of it. It swipes too much, they say, from classic studio musicals and the work of Demy, and it doesn’t live up to either model. But tastes change. I remember when the classic musicals that we venerate were considered fluff, and I recall how Demy’s films, especially Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, were held at arm’s length by many of my 60s pals. “He tries too hard,” a friend remarked. Some say that about Chazelle, and perhaps in a few decades La La Land will be remembered fondly.

In any case, I’m not aiming to denounce this ambitious, agreeable film. I’m more interested in asking how La La Land accords with the craft of studio musicals and Demy’s efforts. I’m also interested in tracing its affinity with a third tradition of song-and-dance: the Broadway show.

Along all three dimensions, I hope to take Shklovsky’s advice and ask about craft. La La Land is both derivative and original. Actually, most movies are, though in various proportions.

The song plot

If we want to understand how film form and style work, we can’t neglect the nuts and bolts of moviemaking. In trying to achieve particular effects, filmmakers have created craft traditions, favored options bounded by loose limits. Mostly these traditions grow up intuitively, as solutions that just feel right. In any case, behind the cluster of preferred practices we can often find principles of design and execution that can be made explicit.

A lot of what Kristin and I have been doing since the 1970s consists of trying to bring to the surface filmmakers’ underlying habits and conventions. Those help shape how viewers respond to films. We aren’t maniacs for systematization—art can’t be utterly systematized—but as analysts we want to discern patterns of story and style, what earlier entries have called schemas. And as historians we want to understand how patterns of story and style get passed down from earlier films, and passed around among contemporaries.

For example, some narrative schemas of American studio cinema are what I aim to lay bare in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. Without invoking the big guns of theory, I try to point out how craft traditions of plotting and narration got recast in those crucial years. A recent entry hereabouts tries to show the legacy of those years surfacing in current releases, La La Land included.

Other researchers work along these lines, and not just in film. Art historians have been doing this sort of research for a long time, as have musicologists. A more recent example in the domain of theatre aesthetics is Jack Viertel’s exhilarating book The Secret Life of the American Musical. Its subtitle, How Broadway Shows Are Built, is a throwback (inadvertent, I suppose) to Shklovsky’s essay “How Don Quixote Is Made.” The impulse is the same: to x-ray an art work, to reveal some fundamental principles of construction, while also doing justice to its revisions of inherited traditions.

Other researchers work along these lines, and not just in film. Art historians have been doing this sort of research for a long time, as have musicologists. A more recent example in the domain of theatre aesthetics is Jack Viertel’s exhilarating book The Secret Life of the American Musical. Its subtitle, How Broadway Shows Are Built, is a throwback (inadvertent, I suppose) to Shklovsky’s essay “How Don Quixote Is Made.” The impulse is the same: to x-ray an art work, to reveal some fundamental principles of construction, while also doing justice to its revisions of inherited traditions.

What Viertel brings to the table is the “song plot,” a sequence of musical numbers that has become conventional in Broadway shows. Often, of course, many numbers enhance the dramatic action, but sometimes they’re inserted for a change of mood or a burst of energy. The song plot both echoes the action plot and provides its own arc of pleasure, with musical numbers that may be more or less extraneous to the main action.

What makes Viertel’s anatomy of shows interesting is that even the narratively “irrelevant” numbers tend to occur in the same spot from show to show, and they have a common emotional quality. They aren’t just “spectacle interrupting narrative,” to use a film-studies commonplace. As spectacle, they have their own pattern, and that’s gratifying alongside the pleasures of the story. Viertel’s macro-schema is probably known to many insiders and fans, but it was all news to me, and it helps me understand the musical spine of this recent movie.

Hence today’s title, of an entry that is 100% spoiler-filled. I’ll consider La La Land as a classically constructed film. Then I’ll test its “making” against Viertel’s template of a musical. I conclude with some remarks on how analyzing these patterns highlights the movie’s variance from adjacent traditions.

From meet-cute to remeet, and re-remeet

Start with the Hollywood plot structure. Kristin has argued that even though mainstream American screenwriters sometimes claim to be following a three-act plot model, their craft practice often pushes them to a four-part schema. (She has discussed this here, and I’ve given examples here and here.) Specifically, the long second “act” is usefully thought of as two separate parts split by the film’s midpoint.

The conventional plot pattern consists of a Setup in which protagonists define their goals; a Complicating Action that redefines those goals; a Development that muddles, delays, or intensifies the goals; and a Climax that resolves them. These parts typically run 20-30 minutes, and films of varying lengths, long or short, can include more or fewer parts than these four. In most cases there will also be an epilogue or “tag.”

La La Land runs almost exactly 120 minutes, not counting the opening logos or the end credits. The Setup (running 25 minutes) establishes Mia and Sebastian as dual protagonists, caught in the midst of the initial traffic jam.

We then follow Mia through her day as a barista, her failed audition, her return to her apartment, and her agreement to go out to a networking party with her flatmates.

A flashback returns us to the traffic jam, and now we follow Sebastian to his apartment, where in a parallel to Mia’s day he makes coffee, rummages through unpaid bills, and talks with his sister. He goes on to his job as pianist playing Christmas music at a cocktail bar. Mia, who’s come in by accident, stands before him, moved by his switch into improvised jazz. But Sebastian is fired, and disgruntled, he coldly bumps past her.

The Complicating Action starts after Mia fails another audition. She goes to a pool party and sees Sebastian in the ensemble. She teases him, and they leave the party together. Although there’s friction between them, they start a friendship. They confess their dreams: she wants to be an actress and he wants to start a club that hosts classic jazz.

Mia absentmindedly agrees to go to a movie with him on a night she has a date with her boyfriend. But she’s haunted by Sebastian’s music and she finds him at the theatre, watching Rebel without a Cause. They go to the planetarium featured in the film and kiss. At the end of the Complicating Action, about 60 minutes in, Mia resolves to write a one-woman show for herself.

The Development is the stretch where backstory is introduced, obstacles create delays, and subplots intertwine with the main action. Since in La La Land the romance seems solid (there are no love rivals), and there are no secondary characters of consequence, the film is devoted to the other major plotline: the obstacles encountered in our couple’s quest for success. Those in turn affect the romance.

A Development also typically relies on montage sequences, and we get plenty here. Mia works on her show, while Sebastian is offered a chance to join his friend Keith’s combo. To stabilize his life with Mia, he takes the job.

Soon he’s on tour, and the band finds some success, though he’s compromising his principles. “Do you like the music you play?” Mia demands, and he evades answering. The crisis comes when a photo shoot delays his arrival at her premiere, which is a fiasco.

Mia declares: “It’s over”—meaning both her career and their affair. She goes back home. We’re at the 90-minute mark.

We’re ready for the Climax, which is often driven by a deadline. Sebastian takes the call asking Mia to audition, and he rushes her back to it. She gets the part, and the two of them decide to wait and see how their relationship develops.

Five years later, Mia is now a success. This seems an abrupt, even anti-climactic turn of events, coming only eleven minutes after the Climax started. Apparently, despite their declarations of undying love, the couple’s romance was never rekindled. We see Mia visit the café where she was once a barista and return to her hotel and her husband and daughter. Her activities are crosscut with glimpses of Sebastian alone in his apartment. In effect, this passage balances our alternating introduction to the couple during the Setup.

Mia and her husband drop in on a club that turns out to be Sebastian’s. Mia and Sebastian eye each other longingly. Mia watches him play Their Song, and this launches an apparently shared fantasy of an alternate-world climax and resolution.

There’s a replay of the two of them at the cocktail bar, but this time Sebastian doesn’t brush past her. They kiss passionately. After this what-if premise, the race to the audition is replayed in stylized form, and the trajectory of Mia’s career—going to Paris, finding screen success, forming a family—is reenacted with Sebastian as her mate. At the end, Sebastian, not her husband, is sitting with her in the club (listening in effect to himself), and they kiss.

This soufflé of flashbacks and fantasies ends the plot on the conventional romantic clinch. But the film’s tag, of course, is their return to reality and the sad smiles shared as she goes off with her husband. In all, this double climax/ resolution turns out to run almost thirty minutes, which would be unusually long for a non-musical.

As is customary in Hollywood narrative, motifs and parallels crisscross the film. The opening song on the freeway lays out hints of what is to come. The sequence alternates a woman singing about a career as a film star (“It called me to be on that screen”) and a man singing about a career honoring old music (“ballads in the bar rooms left by those who came before”). Anticipating the finale, the woman’s song includes mention of a boy seeing her on the screen and remembering that he knew her.

More parallels and rhymes follow. Mia nearly stands up Sebastian on their date; he misses her show. Each encourages the other to keep struggling. Mia’s blockhead boyfriend anticipates her eventual GQ husband, as if she has decided not to go for the edgy type Sebastian is. The motif of Mia’s beloved aunt, who inspired her love of movies and her urge to act, gets dramatized twice, once in her one-woman show and more successfully in her audition song, “Here’s to the Ones Who Dream,” which wins Mia the movie part.

So many things are doubled that it’s not surprising that the Setup parallels each protagonist’s day and establishes the crucial moment at the supper club. That too gets replayed—once in the real world, as she and her husband hear Sebastian’s performance of his tune for her, and once at the start of the fantasy projection of their future, which becomes a replay of her actual life with her husband.

So far, so classical. But—duh, as they say–La La Land is also a musical.

That’s the Broadway melodies

My outline of La La Land‘s construction is fairly hollow, and could be filled in with closer consideration of the moment-by-moment process of conflict and change, or the flow of information as we’re attached to one character or the other. But we get access to another layer of “making” by considering the film as a musical–more specifically, a Broadway musical. (No surprise that the lyricists are stage-based.) Viertel is a big help here. His account of the prototypical song plot fits La La Land fairly well, and the places where it doesn’t are pretty interesting too.

Broadway shows of the Golden Age (roughly 1942-1975) tend to have the double plotline characteristic of Hollywood films. Both shows and movies make romance central, and this permits the action plot and the song plot to fit together. In Broadway shows, as in many films, paired protagonists try to find happiness in both love and work. Intertwined goals are central to getting the action moving, and so goals are ingredient to the song plot.

Director Damien Chazelle apparently hesitated about opening with the freeway-gridlock number, but he and editor Tom Cross decided to announce the film’s song-and-dance premises immediately. I think the pressure of show-biz tradition helped. According to Viertel, the prototypical musical might start with a solo, as with Oklahoma!’s “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’.” But it may also start with a “blowout,” and La La Land’s “Another Day of Sun” surely counts as that. It establishes milieu and mood, in somewhat the manner of the bouncy introduction to Damon Runyon’s world in Guys and Dolls, and it announces the central goal of showbiz success.

Viertel marks the next number as crucial. It’s the “I Want” song, the initial crystallizing of the protagonist’s goals. In La La Land, that position is occupied by “Someone in the Crowd,” which starts as an ensemble number with Mia’s brassy roommates but devolves into a solo for her. By then, the “someone” she seeks isn’t only a career-enhancing meetup but a love partner.

After the plot moves into the Complicating Action phase, Mia and Sebastian meet cute again at the pool party. He’s playing in a lame retro band and she teases him, in revenge for his brushoff at the piano bar. There follows the next key item in the song plot, what Viertel calls “the conditional love song.” The prototype is “If I Loved You” (Carousel). Essentially it declares how wrong the boy and girl are for each other. It has the function of blocking and deferring the goals of the love plotline, and in non-musical rom-coms, it takes the shape of verbal sparring, quarrels, and competition (as in, say, You’ve Got Mail).

Clearly, “A Lovely Night” is a conditional love song, as Mia and Sebastian remark on how the LA view would be perfect for a couple who were really in love. But as often happens, while the words refuse romance, the music and the choreography show that the two ought to be together.

At this point in the song plot, Viertel suggests, the show needs a burst of energy. In La La Land, what he calls The Noise is delivered by the instrumental number at the jazz club, called in the soundtrack album “Herman’s Habit.” It’s not narratively gratuitous, as it’s an AV demo of the sweet collective creativity Sebastian admires in classic jazz. The number also marks Mia’s growing affection for Sebastian and her belief in his dream.

But now Viertel’s Broadway template diverges from La La Land, and it points up a crucial factor in the film. The conventional song plot typically devotes a number to a second couple or a subplot. Think of the comic couple in The Pajama Game, and the number “I’ll Never Be Jealous Again,” which expresses Hines’s unreasonable fear of losing Gladys. That show also includes the subplot of labor negotiations with the devious Mr. Hasler. But La La Land doesn’t have a subplot involving a second couple, a romantic triangle, or a villain. So no such song appears.

Next on the Viertel template is a star turn, a distinctive number for one of the major players. That function is fulfilled by “City of Stars,” the introspective musing of Sebastian on the pier. Viertel indicates that the following number tends to be a high-energy tentpole that starts the buildup to the first-act curtain. That position is occupied by the airy pas de deux at the Griffith Observatory on their first date.

We’re now into the Development section, with Mia working on her one-woman show and Sebastian touring with his friend’s combo. The summer montage sequences offer other numbers, including Sebastian’s performance with the jazz group and the “City of Stars” duet with the couple at the piano. These bits don’t fit easily into Veirtel’s template, but what does is the “curtain song,” the Messengers’ “Start a Fire” number. It’s splashily performed at the concert that makes Mia apprehensive.

The performance functions as a curtain song, I think, because of Viertel’s claim that the close of the first act typically signals dashed hopes. The curtain numbers of Gypsy, Guys and Dolls, Carousel, West Side Story, and other shows announce a failure to achieve goals. “The most typical kind of first act curtain,” Viertel explains, is “the unraveling, in an instant, of everything everyone has planned.” It’s too strong a description of La La Land’s concert, but Sebastian’s cynical keyboard tweaks during the band’s blast of adult contemporary R&B mark him as a sellout. “Do you like the music you play?” He seems to have given up his dream, a failure that becomes the first crack in the couple’s relationship.

There are fewer discrete numbers in the film’s last stretch; it lacks several songs in the Viertel template (the Welcome-Back number, the second star turn, more subplot songs, and the first big showpiece). Owen Glieberman has noted that the film’s second hour is notably less buoyant, and the first full-blown number in the Climax is melancholic.

“The Fools Who Dream” is gently confessional, in contrast to the overheated delivery of Mia’s earlier auditions. It’s what Viertel calls a second-act showpiece, and true to that convention it yields a big plot point: She wins the role.

The resolution of the plot, what Viertel calls the “next-to-last scene,” need not be a number at all. It’s often a “book scene,” and so it is here. After Mia wins the role, she and Sebastian admit both their love and the difficulty of staying together.

There follows the finale, a bookend to the freeway opening. “The 11:00 scene,” as Viertel points out, is often a wide-ranging reprise. La La Land’s eight-minute sequence presents a synthesis of the musical motifs and a revised, stylized version of Mia’s career.

Oklahoma! is usually credited with popularizing the fantasy ballet interlude, a convention that was picked up in the “Miss Turnstiles” daydream of On the Town, the Girl Hunt of The Band Wagon, and many other what-if sequences in Hollywood musicals. As a stroke of novelty, La La Land saves its fantasy ballet for the end, and makes it a bittersweet contrast to the real resolution.

Reports on the creative process behind La La Land indicate that the filmmakers were constantly weighing their choices about where to put their musical interludes. The fact that they settled on a layout that sticks fairly closely to the Broadway template suggests that Viertel’s song plot has advantages that creators intuitively gravitate towards. Its emotional arc both complements and extends the drama-driven plot.

The long and the short of it

Viertel’s anatomy of the Broadway song plot nicely fills out some patches of classical dramaturgy. It helps us better understand the tacit guidelines that creators follow, and it shows how even movies not drawn from stage shows have absorbed some of their conventions. Yet Viertel’s layout does more than point up the affinities between La La Land and stage musicals. It also helps us see where the film rejects the traditional schema.

The film’s deletions from the song plot omit love triangles (of any consequence), subplots, villains, and parallel couples. Sebastian’s sister is basically an expositional device, while Mia’s roommates are barely characterized and her parents barely seen. The bandleader Keith is mostly a mouthpiece for a musical idiom, and the other members of the combo aren’t individualized. No secondary character is granted a show-stopper like “Sit Down, You’re Rocking the Boat” or “Steam Heat” or “Make ‘Em Laugh.”

In sacrificing subplots and side bits, La La Land forfeits what such devices add: a different range of emotions, thematic contrasts, relief from overexposure of the two lovers, and comic relief. The film gives up accessory pleasures, like the counterpoint romance of Nathan Detroit and Adelaide in Guys and Dolls, or the ballad of the parents at the piano in Meet Me in St. Louis. In a bold genre change, La La Land stands or falls by its two principals.

Strangely, this spare plot consumes two full hours. Compare its Hollywood counterparts. Cover Girl, another showbiz tale, runs fifteen minutes shorter, but has time for a fully-rendered sidekick, a competitor for the heroine Rusty, a nice role for Eve Arden, and a parallel plot (thanks to flashbacks) devoted to Rusty’s grandmother. At 95 minutes, On the Town squeezes in three couples and a New York travelogue. As for the often-invoked Demy, compare the 90-minute Umbrellas of Cherbourg, which manages to deck the plot out with two old ladies and two deftly characterized rivals for the central couple. Better yet, recall Les Demoiselles de Rochefort. Granted, it too runs two hours, but it has to pack in five couples, one triangle, a starstruck café waitress, and for good measure a serial killer.

More broadly, La La Land doesn’t give its protagonists sharply defined goals. They just want to succeed, through rounds of auditions or short-term music gigs. In Cover Girl Rusty is given clear-cut options: To sign on as a model or stay a club dancer? To marry a piano player or a Broadway impresario? And as Viertel points out, there’s often a bigger issue at play—statehood in Oklahoma!, modernizing a country in The King and I, moving a family from St. Louis to New York. Nothing like this hovers over the couple in this rather hermetic movie.

What fills up that extra running time in La La Land? For one thing, the very parallels that I’ve mentioned, notably the extended scenes in the café; but also, I think, the pool party, with its sideswipes at the movie industry, and the planetarium dance, pretty as it is. A older studio-era film would have gotten the romance going sooner, in the Setup, sharpened the choices facing the characters, and fleshed out their milieu with friends, family, and minor players who get a little bit of the spotlight. (Keith would almost certainly have gained a romantic partner, hopefully a wise-cracker.) A Demy film would have added more characters as well, with a crisp geometry of counterparts and substitutions. Everything would be color-coded too.

The slimness of the plot can be taken as a point against the film, but focusing a musical so tightly on the couple was probably worth trying. If anybody cares, I enjoyed the film, and—to invoke the distinction between taste and judgment—I think it’s a solid, sometimes stirring effort. But what matters to me now is the way that thinking about craft traditions, particularly as they affect structure, allows us to plot some ways in which La La Land is both traditional and original. Evaluation is important, but it can be guided by analysis. An essential part of criticism involves studying how things are made.

Thanks to Jeff Smith for advice about the Messengers’ musical idiom, and to Michael Campi and Peter Rist for discussions about the film.

The quotation from Shklovsky at the start comes from the extract from A Sentimental Journey (1923) in Viktor Shklovsky: A Reader, ed. and trans. Alexandra Berlina (Bloomsbury, 2017), 150. For another Shklovskyan foray into contemporary moviemaking, you can try “Pulverizing Plots.” My quotation from Viertel on first-act curtains comes from The Secret Life of the American Musical, p. 152.

More on the making: A fairly detailed account of LLL‘s choreography is provided at the Verge, with more film references than you can shake a stick at. On the authenticity dimension, Glenn Kenny gets on the case of jazz purists.

Kristin’s discussion of four-part structure is at its fullest in Storytelling in the New Hollywood: Analyzing Classic Narrative Structure. I discuss it and apply it to some examples in The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Msodern Movies. For more examples, visit our category Narrative Strategies.

P.S. 24 January 2017: LLL has garnered a heap of Oscar nominations this morning. Now this Los Angeles Times story supplies more information on how it was made (financially).

Les Demoiselles de Rochefort (1967).

Modest virtuosity: A plea to filmmakers, old and young

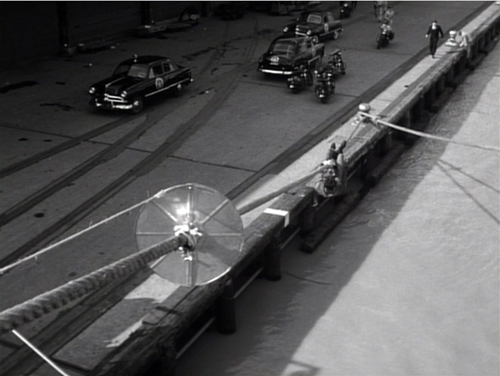

Panic in the Streets (1950).

“It’s where you put the camera and what’s in front of you [that’s important],” Deakins said. “There’s too much obsession these days about digital film…it’s becoming so technically-orientated, and that’s just distracting from what’s actually being put in front of the lens.”

DB here:

Every now and then I get worried by the repetitive look of recent films. I want to beg filmmakers (young ones especially) to try something else.

What could they do? Start with what to avoid. They could suspend the walk-and-talk, the tendency to rely on singles, the bumpy handheld takes, the swoopy crane shots, and the urge to cut on every line of dialogue. They could back off, in other words, from intensified continuity and go for something more daring and original.

More positively, there are some relatively unexplored areas of film style that yield results that are forceful and graceful. Today’s example: ensemble staging that minimizes camera movement and cutting. Minor spoilers.

Some basics

It’s a demanding technique. Essentially the filmmaker has to shape a scene among several actors in ways that guide our attention to the key pieces of information. That guidance is done through performance, framing, lighting, and other tactics. Beyond highlighting the major points of the scene, staging can create what critic Charles Barr called “gradation of emphasis.” Because several elements of the action are all visible at once, some can become primary, some secondary; and this interplay enriches our understanding of the scene.

So take this scene from Elia Kazan’s Panic in the Streets (1950). A dead man has been found to carry the Bubonic plague virus, and Dr. Clinton Reed is investigating people who have come in contact with him. A restaurant owner and his wife have denied knowing the victim, but now Reed and Police Captain Warren have learned that the wife has come down with the plague. They visit the apartment, too late to save her. Her husband Mefaris comes in and learns that she has died—and that she might have lived had the couple told the truth.

The two-minute scene plays out in just two shots, both with slight panning movements. The scene’s impact owes a lot to the performances: the line readings, facial expressions, and gestures, including the wonderful way that Richard Widmark rips off his surgical mask in angry frustration. But the scene also benefits from small but significant rearrangements of the actors in the frame. This staging ties together the performance elements in a smoothly rising flow.

Here’s the scene. I’ll try to indicate some practical directing principles at work.

After Captain Warren has sent his men to find the husband, we have our principal players in the middle ground in a framing from the knees up (the plan-américain). As is common in 1940s dramas, the scene will be given added depth, not only by the patrolman behind Warren but by the junior officer Paul behind Reed, coming out of the sickroom. That depth is activated when Reed comes forward to pack his briefcase and orders Paul to burn the bedding, and Warren orders the patrolman to close the bedroom door.

The opening and closing of the door becomes an important pictorial element, but for now it simply clears the background for the two-shot involving Warren and Reed talking of the death certificate. Noise from offscreen motivates the camera’s pan left to follow Warren as he meets the husband, Mefaris, coming in.

Mefaris confronts Reed and demands to know what’s happening. When he calls his wife, Paul steps out, guiding our attention to him as a sign of death. Mefaris begins to guess. The phlegmatic patrolman, who’ll feature throughout the scene, is there to keep Mefaris under control.

The risk is that we’ll watch that centrally place cop and miss something else, so Kazan takes care to make him impassive. Later, he’ll be more distant, in shadow, and out of focus. More generally, such ancillary characters need to keep still and stare at what we’re supposed to be watching.

Mefaris comes closer to Reed, blocking our view of Paul. Reed tells him his wife is dead. Mefaris tries to go to her room, but the patrolman shows his value by restraining him—and opening up a slot for us to see Paul, who confirms Reed: “She’s dead, mister.”

This sort of unnoticeable blocking and revealing through slight shifts in actors’ position goes back to 1910s cinema but is seldom used today.

Finally accepting the grim news, Mefaris ponders and comes forward. Without cutting, Kazan has brought him and Reed into closer visibility. As ever, a Cross refreshes the composition. And as Reed asks questions, his head blocks the patrolman so that we can concentrate on Mefaris’ indignant reaction.

Mefaris’ refusal to talk is the climax of the shot. We cut to Warren at the door and the camera pans with him to confront Mefaris angrily.

Now only Reed is visible in the background, squeezed between the two faces. Mefaris finally identifies Poldi as the man they need to find. Warren shoves him down and the space, quite clenched just a moment before, opens up. As gradation of emphasis, we get Reed brushing at Mefaris’ lapel after Warren’s meaty hands have crumpled it. After Warren’s outburst, Reed’s anger at Mefaris seems to have turned into a flicker of compassion.

Warren and Reed depart, just as Paul returns to the death room and the patrolman closes the door. The final framing leaves nothing to distract us from Mefaris, brought low by grief and his fatal failure to cooperate.

Kazan is, we might say, a “post-Welles” director in that he, like many others, adopted the vigorous use of depth staging and wide-angle cinematography made famous in Citizen Kane. It’s not hard to find elsewhere in Panic in the Streets some more flagrant instances of in-your-face deep focus, with big heads and exaggerated distant points.

In the scene above, the depth is nothing like so aggressive. It is, we might say, modestly virtuoso—a clean, unnoticeable, but well-calibrated piece of staging that unfolds the action so that we always know where to look.

Why not?

I anticipate some objections from a skeptical filmmaker.

“This scene isn’t cinematic. There isn’t enough cutting and it’s lacking close-ups.”

Today, though, everybody acknowledges that cutting isn’t the be-all and end-all of cinema. Directors get lots of credit for sustaining their shots, if it’s done with a self-congratulatory virtuosity. (See Gravity, Birdman, the opening sequence of Spectre.) In particular, a lengthy walk-and-talk shot is greeted as a bold stroke. So clearly the absence of cutting is okay if you make a big deal of it.

Close-ups are important, but maybe not as much as we think. Today’s style often relies too much on close-ups, partly because people think they won’t read well on small monitors and other displays. But those displays are getting bigger and sharper. I suspect that you’d find the Blu-ray edition of Panic in the Streets plenty okay for home viewing.

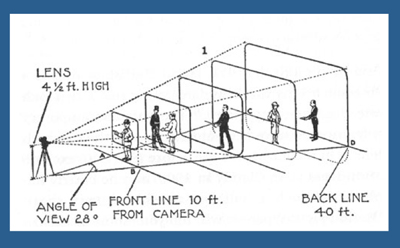

“Put it another way. This is too theatrical.”

Too reliant on actors, then? But what mainstream cinema isn’t? And isn’t today’s standard style, bombarding us with facial close-ups, quite “theatrical” in making the actor—and not even the body, just the face—the center of our attention?

Moreover, as I’ve argued here and elsewhere, the space of a shot is the opposite of the space onstage. Theatrical space is wide and rectangular, and actors tend to arrange themselves laterally, across the stage. Cinematic space–the space captured by the camera–constitutes a pyramid, extending narrowly away from the lens, and so it favors depth. (See the diagram above.) Theatrical space is calculated for the sightlines throughout the auditorium; cinematic space is calculated for one sightline, that of the camera. Accordingly, a film can have staging in depth that wouldn’t work onstage. You couldn’t arrange the Panic scene this way in live theatre; some people couldn’t see the background action clearly, because the foreground figures would mask it.

If “theatrical” also means “too tied to the proscenium,” that objection fails too. Granted, this is a scene that suggests a missing fourth wall. The camera doesn’t penetrate the space enough to suggest the entire room. Shortly, though, I’ll show you that this approach can be more immersive, activating areas behind the camera (and so behind us).

“It’s not realistic. People don’t stand and talk that way.”

Cinema ≠ reality.

“It’s too risky. Too much can go wrong with all that shifting in one shot.”

You need skillful actors who can time their lines, hit their marks, and coordinate with one another. If one thing goes wrong, you have to start again. Shrinking from this, directors opt for plenty of coverage to adjust pacing and select the best performances during editing. “The important thing for the editor is coverage,” notes Ridley Scott. “That’s why I always have multiple cameras, so I can shorten the scene.”

So, yes, it’s risky. But risk is celebrated in the noisy virtuosity of the flamboyant long takes. Why not take risks in this more unusual way?

“It’s too hard! I never learned how to do these things.”

Once upon a time, every director knew how to stage scenes like this. The “tableau cinema” of the 1910s cultivated a rich set of creative choices about staging, and directors proved very versatile in exploring them. With the arrival of continuity editing in the 1910s, a degree of de-skilling took place, but directors still retained some sense of dynamic staging. We see it in 1930s and 1940s films too.

Now, much later, this sense is all but gone. Is ensemble staging taught in film schools? Could even our best directors of today—Wes Anderson, Paul Thomas Anderson, Quentin Tarantino, et al.—pull off a scene in this manner? Soderbergh couldn’t do it when he tried in The Good German. (I look forward to seeing if Todd Haynes makes the effort in Carol.)

On the whole, though, I agree: It’s hard today. Neither directors nor actors nor DPs are, I think, well-versed in what’s necessary to stage scenes this way. Most directors, and nearly all viewers, have simply forgotten that this rich menu of expressive techniques ever existed. So why not revive it?

Post-grad work

One other objection occurs to me.

“Ensemble staging of this sort is too modest. In an age of directorial bravura, where every filmmaker tries to punch above his weight, nobody will notice if I direct scenes this way. And getting the next job demands that my contribution get noticed. I’m competing with a lot of eye candy out there.”

I’d agree. But there is a lot of leeway in this approach for more self-conscious effects. Maybe most viewers and even filmmakers wouldn’t notice the robust delicacy of the scene above. But how about offering something more audacious that stays within the parameters of this style?

Try this earlier scene from Panic in the Streets. Reed, his assistant Paul, and local officials are now identifying the plague virus and are beginning to figure out how to deal with it. I hope I’ve primed you to notice the less-quiet virtuosity on display here.

A director today might have shown us the body, the reporters photographing it, and the medical team in one vast shot, perhaps from a high angle that craned in. Or perhaps we’d have gotten a long walk-and-talk taking Reed through a hospital corridor as he snaps out orders to all the staff involved.

Instead, Kazan leaves a lot of this material offscreen, to be inferred through details. The plaguey corpse lies just outside the lower frame line, but we won’t realize this for a while. And the reporters are offscreen, “behind us.” So we’re inside the proscenium. Part of the interest of the scene is not just following the ongoing drama but figuring out what’s going around us.

In this more complex scene, Kazan threads characters through the space, making some more prominent and then letting them fall back. He obeys Alexander Mackendrick’s dictum:

Composing in depth isn’t simply a matter of pictorial richness. It has value in the narrative of the action, the pacing of the scene. Within the same frame, the director can organize the action so that preparation for what will happen next is seen in the background of what is happening now.

We start with Reed and his team bent over the microscope. In the background a patrolman passes. For an instant the frame flares up.

Reed looks up, slightly annoyed, but when it happens again we can see that it’s the result of a photographer’s flash. In the distance, after Reed bends over, we can see the patrolman blowing his nose. Because we know that the plague is loose, that simple gesture becomes a warning. And on the big screen you can now notice the vague reflection of the photographer in the window between Reed and Paul. The second fading flashbulb tells us where to find this man’s phantom image.

So the action develops in three zones.: the cops in the distance, the team at the microscope, and the offscreen police photographers behind us. Two of these zones get closed off when the photographers leave and Reed orders the curtains drawn.

The space goes shallow as we get a succession of two-shots, the first with the health officer who comes forward and learns that he must cremate the corpse, the second with the morgue supervisor.

Now we get a pause. Reed, isolated against the curtains, stares down at the corpse, trying to work out a plan. As in the earlier scene, a simple pan brings Paul to him for a final two-shot. The serum has arrived, and this sets up the second phase of the scene.

The scene has developed around two nodes: the microscope bench in the middle ground and the still-unseen corpse in the foreground. This use of depth has fulfilled Mackendrick’s dictum, as the action around the ‘scope has prepared us for the series of one-on-one instructions Reed issues to his team. As in the earlier scene, this shot ends with the figures closer to the camera than they were at the start.

As in the earlier example, we get a cut. (Critics have often talked about single-shot scenes. What about studying two-shot scenes? I suggest we start with Mizoguchi.) Reed heads outside for another encounter, this time with a police official, who gets emphasized not through cutting but by letting his head block that of the morgue supervisor.

We pan with Reed as he goes to the corridor and the gathering group. More blocking and revealing: As Reed asks the cop about people who’ve been in contact with the corpse, he pivots and the composition frames the sniffling cop in the vanishing point.

Today a filmmaker might give us a big close-up of this poor guy, playing up his misery. But that would suggest that he’ll become an important story factor. He’s actually not in danger, so his minor status in the frame is completely appropriate.

For similar reasons, no need to cut in to Reed addressing the assemblage of men; none will prove significant. Instead, the action moves back to the foreground. First, Reed thanks the morgue attendant.

More important, and more virtuoso, is the way that the key dramatic elements in what follows are framed in a tight space between Paul and Reed in the foreground. First it’s the official in charge of cremation, then it’s the two skeptics.

Once more a shot ends in the closest framings so far. As a complaining civilian quarrels with Reed, both advance to the camera and Reed obliges him to take his medicine. The shot ends with the man wincing and lowering his head as the needle goes in; not such a tough guy after all.

Far from being simply of casual interest, these reluctant ne’er-do-wells anticipate the stubbornness and stupidity that Reed will encounter when he ventures into the city among the populace.

It seems to me that this sequence, with the flashbulbs and the curtain and the line-up for the vaccine, provides a self-assured command of craft that is as exuberant as anything in today’s flashy direction. If you can be flashy in a quiet way, this scene manages it.

This kind of staging can give cuts extra force. In the first scene, the cut to Warren ratcheted up the tension: Reed’s persuasion failed to win over Mefaris, so brute force is the next step. In the mortuary scene, the cut to the corridor as Reed passes through is more perfunctory, but it at least maintains the fluidity of the action.

A more dramatic instance of saving your cut for maximum impact comes near the climax, when Poldi is carried down a precarious staircase and his crooked boss Blackie flings his body over the railing. The cut to the extreme long-shot shocks you with how far he must fall.

There is much else to admire in Panic in the Streets; it’s a fine instance of Joe MacDonald’s location cinematography as well. I use it as simply an example of how much classical cinema has to teach us. It’s a pity that our filmmakers have unlearned some of its lessons, but it’s not too late—especially for brave young filmmakers—to relearn them.

For an example of lateral, rather than depth-based, ensemble staging, see our most popular entry, “Watching you watch There Will Be Blood.” Use the category tableau staging to access entries on the principles I’ve mentioned. The whole subject is discussed in more detail in Chapter Six of On the History of Film Style and in Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. It’s also treated in my video lectures How Motion Pictures Became the Movies and CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See without Glasses. The diagram of the visual pyramid is from Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs, Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film (Oxford University Press, 1997), 170.

Panic in the Streets.

Il Cinema Ritrovato: Back to the future (of movies)

DB here:

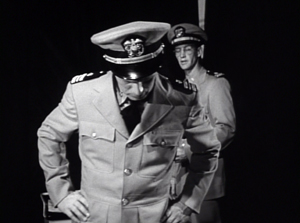

The Teatro Comunale of Bologna is an eighteenth-century opera house that was launched by a premier of a work by Glück. It has hosted massive productions of Wagner, Rossini, and Verdi, and was a favorite venue of Toscanini’s. Elegant and imposing, with box seats and an orchestra pit, it makes you feel like you’re in Senso or Liebelei.

In some years Cinema Ritrovato has secured the Teatro for gala screenings of silent films, complete with orchestral accompaniment. One show of Lady Windermere’s Fan was a delight. In another year, the hammering Meisel score for The Battleship Potemkin nearly blasted me out of my seat. I was sitting up front.

This year it was Rapsodia Satanica (1917) that got the Comunale treatment. This apparition has lost none of its exuberant morbidity, and we got to watch it with the original Pietro Mascagni score. Timothy Brock found that the original orchestra parts were lacking hundreds of tempo changes, because Mascagni himself conducted during screenings and never inserted them. Through careful testing against the film, Brock managed to create a score that brought a packed Communale audience to its feet cheering. One more testament to the power of 1910s cinema.

1915 and all that

Assunta Spina (1915).

I tried, really tried, to see other wonders from all the places and periods on display at this year’s overstuffed Ritrovato. But because of my love of ‘teens films, both American and not, I kept coming back to as many items from that era as I could squeeze in.

There was, centrally, the series Cento Anni Fa (A Hundred Years Ago), curated by Marianne Lewinsky and Giovanni Lasi. 1915 was, of course, a decisive year in American cinema, to be forever identified with Griffith’s monumental The Birth of a Nation. Standard histories would have it that this was the stroke that revealed the artistic power of cinematic storytelling. Griffith’s colossus was naturally very influential, but it wasn’t an isolated accomplishment. Earlier films, such as Weber/Smalley’s Suspense (1913), and other 1915 films–De Mille’s The Cheat and Walsh’s Regeneration in particular–are more typical stylistically of what Hollywood silent cinema would turn out to be.

Add to this list another 1915 item. If film history were an exercise in fairness, Reginald Barker would be recognized as one of the directors who set American filmmaking on its “classical” road. Working under Thomas Ince’s supervision, Barker showed a flair for economical framing, frequent changes of setup, and bold cutting within scenes. His Typhoon (1914) is at many moments more nuanced in its analytical editing than Birth.

1915 was a fine year for Barker. He turned out the long-praised The Italian (shown in the series), as well as the dynamic Civil War drama The Coward, along with superb William S. Hart westerns like On the Night Stage.

So The Despoiler, another Barker from 1915, did not disappoint. It survives only in a cut-down French print, but it still packs a sensational punch.

The original, according to a contemporary review, involves a border war in which troops invade a small town. The leader of the dark-skinned horde fastens on one beautiful woman, who has taken refuge in a nunnery. She is about to sacrifice herself to save the others, when the colonel learns that she is his own daughter. She is saved, and at the very end the whole thing is shown to have been a dream. The French version Châtiment (“Punishment”), painstakingly restored by the Cinémathèque Française in 2010, was modified to fit propaganda demands of the war period. Here the daughter really gets raped, and she shoots her attacker. The colonel turns his troops loose on the nunnery, but halts them in time when he realizes who the victim is. No dream stuff here.

Barker’s style is fluid, and he builds great suspense when the daughter, barely recovered, prepares to shoot her ravisher with his own pistol. The scene has judicious depth staging, as when the soldier lies drunkenly on the cot but he’s blocked by the woman’s gradual decision to use the weapon. At the proper moment she swivels aside to reveal his head lolling in the background.

The match-on-action when the woman turns and pulls up her sleeve is more perfect than many such cuts in Griffith’s films. She then strides to the background to give us a full view of her target.

A brief shot of the daughter’s attacker is replaced by a 3/4 view of her drawing a bead on him, with Jesus taking her side.

Other countries’ 1915 output wasn’t ignored. We got Denmark’s Revolutionary Wedding, proof that August Blom had not given up the somewhat rigid version of the tableau style he had used in Atlantis (1913). More florid were the Italian offerings. Assunta Spina (lovingly restored by Bologna’s own Cineteca and now available in a DVD), is a classic of the nation’s silent cinema. It was treated to a carbon-arc projection one evening in the courtyard. The less-known but no less flamboyant Il Fuoco (“The Fire”) is a melodrama about a rich woman who destroys a naive, passionate painter.

The two films are famous for showcasing the divas Francesa Bertini and Pina Menicelli respectively. But they’re just as important as powerful illustrations of the variety of 1915 pictorial styles. Assunta Spina is a triumph of tableau staging. By contrast, the opening of Il Fuoco, detailing the first encounter of the owl-woman and the burly artist, is as rigorous a piece of editing that I’ve seen anywhere at the period. Assunta Spina fills the frame with layers of depth (above and first still below). Il Fuoco makes play with bold optical POV, especially when the painter is transfixed by his languid model.

To which one can only say: Zowie.

Bluebirds of happiness

Back in the 1980s I wanted to see some films from Universal’s Bluebird Photoplay series. It had been accepted wisdom that the Bluebirds were among the first American films seen in Japan, and accordingly they had influenced Japanese filmmakers. My searchings led me merely to fragments at the Library of Congress. But today, according the Ritrovato’s indispensable catalog, about thirty complete titles have been found in archives. The most famous, Lois Weber’s Shoes (1916), screened at Bologna in 2011.

The Bluebird franchise was identified with feel-good stories, often rom-coms centered on women and derived from fiction by women. Mariann Lewinsky points out that the unit was a training ground for Rudolph Valentino, Mae Murray, Tod Browning, Rex Ingram, and several other notables. A striking number of Bluebirds were directed by women, in particular Elsie Jane Wilson. About 170 films were produced under the logo, and Hiroshi Komatsu’s catalogue entries confirm that they had a powerful impact on Japanese fans and filmmakers.

Four Bluebird titles, all discovered at the French CNC archive, confirmed the ingratiating charm attributed to the brand. Little Eve Edgarton (1916) centers on a botanist daughter who’s whip-smart in science. Her father tries to marry her off to an older colleague, but she resists. The Love Swindle (1918) is more elaborately plotted. The main couple meet cute during a comic home invasion, in which Diana Rosson proves better at defeating hungry tramps than Dick Webster, who gets conked out trying to protect her. After a date, Dick decides Diana’s too modern and highbrow for him. Diana, undaunted, takes a room in a pension and masquerades as her own impoverished sister, Miranda. Dick naturally falls for Miranda.

Here again, the polish and inventiveness of ‘teens Hollywood comes through. Stylistically, we find nearly everything characteristic of classical presentation: scene analysis, angled shot/reverse shot (though no over-the-shoulders), surprising camera movements, expressive low and high framings. In narrative terms, our heroines conceive goals and pursue them tenaciously. Rosamond in The Dream Lady (1918) even makes a list of her four aims in life. Getting a house is surprisingly easy; marrying a real gentleman takes a little longer.

There are as well ambitious storytelling gambits. At one point in The Dream Lady, an orphan girl imagines that she has a mother and lives in nice surroundings. Director Elsie Jane Wilson cuts freely between the girl’s fantasy and Rosamond looking in on her. One startling cut matches on the girl’s gesture of flouncing her ribbon, taking us between dream and reality. (It’s actually a cheat–wrong arm–but perhaps the change of angle covers the disparity. Sort of like here.)

Then there’s the plot of The Little White Savage (1919). It starts with a circus boss and his sidekick telling customers how they acquired a star attraction, a wild girl purportedly from an island on no maps. The flashback yarn is absurd from the get-go, and it gets wilder as it proceeds, as the heroic sidekick somehow goes from he-man adventurer to pious parson. In a surprisingly salacious passage, Minnie, escaped from the sideshow, hops into the clergyman’s bed. They squeeze and nuzzle unashamedly as nosy townsfolks watch in horror.

It’s all a tall tale, of course, confirmed when the frame story reveals Minnie as simply a cute modern girl. The Confession (Fox, 1918), hinged on a more serious lying flashback and may have supplied the premise for The Little White Savage. Again we find the 1910s as an era of fertile innovation. “Its breezy bold difference makes it worthwhile,” wrote a critic of this Bluebird release. “What Paul Powell and scenarist Waldemar Young have done here is the sort of adventure that makes screen progress.”

A bigger-budget Universal release served as pendant to the Bluebirds. Lois Weber’s Dumb Girl of Portici (1916) was a collaboration with dancer Anna Pavlova. A truncated version had long lain at the British Film Institute, but Geo Willeman and Valerie Cervantes found a 16mm print at the New York Public Library. That enabled them to create a very pretty, nearly-complete version, which now concludes with a lengthy Pavlova dance. The super-production, now running nearly two hours, was based on Daniel Aubert’s 1828 opera and offers some ambitious spectacle.

As a prestige entry with crowd scenes, lavish sets, and one of the stage’s top stars, it’s about as far from the humble Bluebirds as you can get. It’s notably stiffer and less dynamic too; what is it about costume pictures that makes for an academic approach? Still, The Dumb Girl of Portici and the Bluebirds exemplify the ways in which filmmakers of the period laid down many paths of exploration for the future.

The devil you know

I first saw Rapsodia Satanica some years back during a Brussels visit. I liked it fine, but seeing it with tinting and hand-coloring, on the big Comunale screen, with a live orchestra convinced me that it really needs its score. The plot is thin, but with the music throbbing along with its heroine’s seductive pirouettes and mournful drifting, the whole thing makes powerful cinema. It was in fact billed as a “Cinematic-Musical Poem,” suggesting that here lyricism will dominate.

With the score tightly matching fluent acting, I’m reminded of a point Kristin made some years ago. She wrote about the ‘teens as an era in which many directors opened up new domains of cinematic expressivity. Having developed effective methods of storytelling, they began looking for techniques that would deepen the emotional impact of the action. Rapsodia satanica is practically a case study for this tendency.

Countess Alba sells her soul to regain youth. One of her suitors kills himself, the other flees. She winds up alone on her estate. This simple story is elaborated through many techniques of mise-en-scène. There are the dancelike performances; Satan practically coils himself around his victim’s calf. There are the costume changes, as Alba moves from her heavy dowager dress to diaphanous veils in her voluptuous phase, and then, in her solitude, a simple shift. When she thinks the surviving lover is about to return, she wraps herself in the veils she wore before. Even the hand-coloring adds impact; as in the pair of stills below, often Alba’s dress is the only colored mass in the shot.

The hallucinatory images gain both precision and passion from the soaring score. Our heroine sells her soul to Satan in exchange for a return to youth. The moment when she sheds her elderly skin and emerges, like the butterfly we’ll see later, as a ravishing beauty is accompanied by a motif that exfoliates just as lushly. An offscreen pistol shot is prepared by a driving crescendo, but the orchestral outburst is still startling. The countess registers the realization that one lover has killed himself, and diva Lyda Borelli synchronizes her attitudes with that climax: body clenched at first, then sliding toward a more doleful pose.

At forty-two minutes, Rapsodia Satanica is practically, as Gian Luca Farinelli remarked in his introduction, an experimental film. Its unsettling use of multiple mirrors, trapping the heroine in fractured reflections, sets up Charles Foster Kane’s zombie-like passage through his palace. The film’s second part, in which the heroine drifts through landscapes and enormous rooms, looks forward to the American “trance films” of the 1940s and the Cinema of Walkies, from Neorealism and Antonioni to Tarkovsky. In all, the film lets us recognize the persistence of some trends across film history, and appreciate that the 1910s are not as far away as they might seem.

Thanks to Guy Borlée and Cecilia Cenciarelli for help with this entry.

The immense catalogue of this year’s Cinema Ritrovato, essential for background to the screenings, can be purchased here. There’s a pdf for reading or downloading here. These folks think of everything.

For contemporary accounts of The Despoiler, see the Lantern pages here and here. The Cinémathèque Française webpage provides a detailed explanation of the restoration. The Photoplay review of The Little White Savage is here.

You can read more about Bluebirds at Adrian Curry’s “Poster of the Week” site on mubi, from which I took the Bluebird logo above. Be sure to scroll down to enjoy the gorgeous designs on display.

For more on why the ‘teens are crucial, see the Vimeo talk, “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.” On continuity editing, you might start here; on tableau staging, here. Kristin’s article is “The International Exploration of Cinematic Expressivity,” in Karel Dibbets and Bert Hogenkamp, eds., Film and the First World War (1995).

Rapsodia Satanica.