Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

What-if movies: Forking paths in the drawing room

Dangerous Corner (1934).

DB here:

We habitually indulge in what-if thinking. What if you hadn’t gone to that particular school, met those specific friends, lived in that particular place? Your future would have been very different, in ways you sometimes speculate about. Here is Brian Eno explaining how he found his career:

As a result of going into a subway station and meeting Andy [Mackay], I joined Roxy Music, and as a result of that I have a career in music I wouldn’t have had otherwise. If I’d walked ten yards further on the platform or missed that train or been in the next carriage, I probably would have been an art teacher now.

We think this way on a small time-scale too. If you had left that damned parking lot a little earlier, you wouldn’t have had the fender-bender you had down the street.

Just as flashbacks exploit our common-sense intuitions about memory, other narrative strategies tap our habit of what-if thinking. Some movies evoke alternative but parallel fictional worlds. The most recent what-if movie I know is Edge of Tomorrow, whose tagline and video release title, Live Die Repeat, sums up its premise. I thought it was an ingenious use of the format, although the ending left me puzzled. Earlier on this site I wrote about a more intriguing example, Duncan Jones’s Source Code. Sometimes I call these “multiple-draft” plots because they keep revising the action until it comes out right.

Hong Sangsoo has explored the what-if possibility with unusual energy, but he’s less explicit about setting up the structure than Hollywood films are. With his movies, sometimes you don’t realize you’re in a parallel-world plot until you notice repetitions of action with tiny differences. (We have entries on Hong here and here and here.)

Some years back I wrote an essay, “Film Futures,” in which I analyzed the what-if, or “forking-path” narrative. That essay, revised for the book Poetics of Cinema, is now available on this site. It explores several examples: Kieślowski’s Blind Chance, Tykwer’s Run Lola Run, Wai Ka-fai’s Too Many Ways to Be Number One, and Peter Howitt’s Sliding Doors.

One Hollywood experiment in this vein was a film version of J. B. Priestley’s 1932 play, Dangerous Corner. I mentioned the play in the essay, but I wasn’t then aware that a film version had been made by RKO in 1934. (To add an extra sting to my ego, it was sitting in our massive collection of RKO movies on campus.) I learned of it just recently when it aired on Turner Classic Movies, a national treasure I have celebrated before. The film quickly showed up online at Rarefilmm, and probably elsewhere.

In the essay, my approach was to treat these films as a sort of genre. What conventions rule them? What motivates the forking-path format—a science-fiction device such as a time machine, or fortunetelling, or something else? How do they tap our what-if thinking? Dangerous Corner lets me test my proposal on a new instance and offer a trailer for a new online essay.

As with any comprehensive narrative analysis, there are spoilers.

They have been here before

Darkness. We hear a gunshot and a woman’s scream. The stage lights come up and reveal some women in a drawing room listening to a radio play, “The Sleeping Dog.” Soon they’re joined by their male partners. An inadvertent remark by one of the women starts a cascade of confessions. The couples reveal a seething mass of illicit affairs, drug addiction, and repressed sexual desires.

As a result of the frenzy of truth-telling, the husband who set the process in motion lurches offstage and shoots himself. Darkness descends; a woman’s scream. When the lights come up, we are back in the drawing room. The broadcast play is at the same point as before. This time things go differently, and music from the radio fills the room as the couples enjoy a banal evening.

The action centers on three men who are partners in a publishing house. Robert is married to Freda, Gordon is married to Betty, and Charles is unattached. The young woman Olwen works at the firm, and Robert’s dissolute brother Martin is dead when the plot begins. The action centers around some missing bonds, which either Robert, Charles, or Martin stole a year earlier. Soon after the bonds went missing, Martin was found shot dead, an apparent suicide. He was assumed to have been the thief.

The action centers on three men who are partners in a publishing house. Robert is married to Freda, Gordon is married to Betty, and Charles is unattached. The young woman Olwen works at the firm, and Robert’s dissolute brother Martin is dead when the plot begins. The action centers around some missing bonds, which either Robert, Charles, or Martin stole a year earlier. Soon after the bonds went missing, Martin was found shot dead, an apparent suicide. He was assumed to have been the thief.

In the course of evening number one, all sorts of naughtiness are revealed. Martin, much loved by all, is revealed to have been a thrill-seeking drug addict with whom Robert’s wife Freda has been having an affair. Olwen is secretly in love with Robert. Gordon’s wife Betty is Charles’s mistress. Gordon in turn is in love with Martin, and we’re to understand they’ve had an intermittent gay affair. Martin has died not by suicide but by accident, when Olwen was struggling to escape from his attempt to rape her. In all, the three publishers’ private lives would suffice for a steamy best-seller.

The point of Priestley’s play is that revealing the truth is a risky business, like driving around a dangerous corner. He uses the forking-path format to suggest the harm of revealing things best kept hidden. Hence the radio play’s title, a reference to letting sleeping dogs lie. For Priestley, however, the parallel-worlds conceit was more than an artistic device. He insisted that Dangerous Corner not be regarded as a dream play but rather “a What Might Have Been.” It proceeded from Priestley’s deep interest in time, which he saw as not merely the linear, “once-and-for-all” track of daily life.

Our real selves are the whole stretches of our lives, and . . . at any given moment during those lives we are merely taking a three-dimensional cross-section of a four-, or multi-dimensional reality.

The same interest in time as split or looped is seen in his 1937 plays Time and the Conways and I Have Been Here Before.

The film version of Dangerous Corner makes some important changes. As you’d expect for a film of the 1930s, the gay plotline and the drug addiction are excised. The character of Charles (Melvyn Douglas) is made more virtuous. He is revealed as the thief, as in the original, but here he has stolen the bonds to help Betty pay off gambling debts. She is no longer his mistress but a friend he is protecting. In addition, Charles is shown pursuing Ann (the play’s Olwen), who turns aside his proposals of marriage. At the end of the film, she agrees to marry him, providing a romantic wrapup.

The first seventeen minutes of the film establish the Charles-Ann courtship and present portions of the play’s backstory. We witness the three men discovering the theft of the bonds, and soon we watch Charles’ discovery of the dead Martin. An inquest declares the death a suicide, and a year passes. Now begins the play’s opening situation, with the women in the parlor. But there’s no longer a radio play running; instead, they’re listening to music before they hear a gunshot. That turns out to be the result of Robert’s firing his pistol into the garden to show it off to Gordon and Charles.

Coming into the drawing room, the men pair up with the woman and banter with their guest, the novelist Maude Mockridge. (She’s in the play as well.) The radio becomes important when Gordon goes to it to tune in some dance music, but the tube fails and, as he puts it, “I guess we’ll have to talk.” From then on the film follows the general contours of the play, and I think it exemplifies the conventions of forking-path plots pretty well. What are those conventions?

Using the correct fork

In the essay I start by suggesting that the action in forking-path plots is understood to be linear. Within each track, there is a smooth progression of cause and effect. Both play and film obey this condition through the simple chronology of scenes, but it’s also controlling the puzzle of the missing bonds, which is eventually explained by detective-story logic. Charles admits to taking them, and in the film Betty further explains that he did it to cover the gambling debts she wouldn’t confess to Gordon.

Linearity is also reinforced by a simple either-or switch. In the film’s tell-all version, Gordon can’t play dance music on the radio because there isn’t a spare tube for the radio set. Then begin the exposures of all the peccadilloes. In the alternate-reality version, there is a spare tube in the drawer, and so the exposures can be averted. Tube there: certain things follow. Tube not there: other things follow. Each chain of events proceeds without break or further splitting.

The radio tube is part of the film’s use of a second principle, what my essay calls signposting. If we’re to understand that there are alternative plotlines, we need some clear markings. In the film, we get several.

First there is the “reset” moment in the second version, when we return to the women moving to the French windows and hearing Robert’s firing of the pistol into the garden. That is a pure replay. What follows reiterates the action we saw earlier: The men joining the women, the radio announcing the time, and the initial chat before the signal fails and Gordon looks for—and this time, finds—a fresh radio tube. He thoughtfully reiterates the split for us. Dancing with Betty, Gordon says: “If Freda hadn’t had that spare radio tube, there wouldn’t have been any dance music, and then—well, anything might have happened.” As I suggest in the essay, characters in forking-path plots often get quite explicit about the what-if premise.

More unusual is the film’s use of intertitles as signposts. Robert, overcome with despair by the results of his relentless demand that everyone confess, runs to his room and shoots himself. The screen goes dark, with traces of smoke. Then we get this title:

At face value, this intertitle says that the stretch of time in which the characters exposed their private lives (the first “This”) is fictitious, while the amicable, truth-concealing version we’re about to see (the second “This”) is veridical.

Is this a bit of hand-holding for an audience that wasn’t prepared for the forking-path device? It does have that function, and to our taste it’s probably too explicit signposting. But it’s more interesting than it appears, because it reverses an intertitle that appears in the film’s opening.

Before the action starts, we get this expository title.

Even without knowing how the film will develop, we are invited to imagine a two-part structure. After seeing the whole film, we can see that this puts the dual worlds on the same footing. The phrasing could be suggesting that the cascade of admissions we’ll see is what really happened, while the smooth social veneering of the final scenes was only an alternative possibility. At the climax, we’ll see the second title as a revision of this slightly puzzling one, which now might seem a bit of playful misleading.

But I think this first title is ambiguous in an intriguing way. The film really has three parts. First there are the 1933 events outside the drawing room, involving the robbery and Martin’s apparent suicide; these scenes aren’t in the play. Next block is the first, confessional versions of the 1934 evening. The third part is the alternative, calm version of the 1934 evening. From this angle, the first title is telling us that the 1933 section leading up to the crucial evening is “what really happened,” and that is indeed the case. We don’t get alternative versions of the robbery or Martin’s death. Accordingly, the sordid first iteration of the evening, the film’s second part, becomes “what might have happened.” In a weird way, the title is accurate about the first two chunks of the plot.

In other words, I’m suggesting that the titles fit the film’s structure as follows. The first title is in red, the second in green.

“This is a story of what really happened…”: The 1933 section.

“…and what might have happened.”/“This is what might have happened…”: First, scandalous version of 1934 evening events.

“…this is what did happen.”: Second, banal version of 1934 evening events.

Anyhow, two versions of the evening are quite enough for us. We can imagine more, but in films we never really encounter the radical plurality of multiple worlds. The physics of a true multiverse would offer indefinitely many variants, including ones in which any particular person doesn’t exist. In some worlds, Gordon would be married to Ann, Robert would court Betty, Charles would be a terrier, and so on. But—and here’s my third principle of such storytelling—the usual forking-path plot revisits essentially the same story world with the same characters, relationships, and settings, and most of the same actions. I call it the principle of intersection.

Intersection assures that we don’t get overwhelmed by having to meet a raft of new characters, figure out new settings or time periods, and generally reorient ourselves with each path we’re led down. Forking-path plots, from A Christmas Carol to It’s a Wonderful Life, keep things simple for us by changing very a few features of their rival worlds. Despite Priestley’s belief that each instant of our lives opens up many alternatives, that gigantic exfoliation of actions is very hard to dramatize and even harder for us to keep track of. So in both play and film, we have the same small world, with only a few differences. That works to the plot’s advantage, because those small differences—the radio works/ it doesn’t work, the cigarette box attracts attention/ it doesn’t—can be given enormous importance.

More rules

A fourth principle of forking-path plots involves the use of cohesion devices—elements of story or narration that smoothly link scenes. Cohesion devices are mid-sized examples of Hollywood’s love of continuity on every scale: cause and effect across the whole plot, foreshadowing of a later scene by an earlier one, hooks between sequences, and at the finest grain, shot-to-shot matching. Accordingly, each path in a forking plot ought to lead us along as easily as a normal plot would.

The essay mentions appointments and deadlines as common cohesion tactics. These aren’t very prominent in either the play or the film version of Dangerous Corner, chiefly because the forked action takes place in such a limited time span. But other devices, such as dissolves and fades, help the parts stick together. In the film a flashback dramatizes what Ann says took place on the night of Martin’s death in a way that fits tidily into the overall arc of the plot.

More interesting in the film are the parallels, a common byproduct of forking-path construction. At a macro-level, the two or three or however many paths are sensed as equivalent, variant versions that the viewer is invited to liken or contrast. And both our play and film reiterate the parallels among the couples; the visiting novelist Maude Mockridge says in the film that Charles and Ann should marry and complete the perfect symmetry set up by the “snug” pairings of the two other couples.

In the course of the first night’s exposures, hidden parallels are brought to light. Ann is mutely in love with Robert, who is mutely in love with Betty. Both the Freda-Robert marriage and the Gordon-Betty one are revealed as loveless. In the play, more parallels are piled on: Both Freda and Gordon have Martin for a lover, while Charles keeps Betty as his mistress.

Since parallels invite us to note contrasts, we can see that Phil Rosen (never accorded the status of an auteur) has somewhat altered things during the replay portion of the climax. Some variations in framing mark the second version as different from the first.

Mostly the purpose of the new angles in the replay is to highlight Charles and Ann, preparing us for their romantic alliance on the patio. The first version makes them small and far off-center left; the second emphasizes them much more, with the high angle enlarging and centering their flirtatious encounter.

My two last principles are also borne out in the film version of Dangerous Corner. One says that the last path traced presupposes the others. By that I mean it can take the earlier iterations as already read.

One result is that later versions of events can presented more briefly. When an alternative reality runs through bits we’ve already seen, we don’t need to see the full original version. This happens in the second fork of the film, which takes less than three minutes to get us to the crucial split—when Gordon discovers the fresh radio tube and tunes in the dance music. The first iteration of the evening’s events took almost five minutes to get us to the same point. This may seem a minor difference, but such intervals matter in a movie whose action consumes only sixty-two minutes on the screen.

Moreover, one time-saving passage shows the importance of the first iteration as setting up the situation. In the first version, Maude the novelist inquires about Martin, and she bends over a portrait photo of him.

This shot is less for her than for us, introducing the character whom we’ll see in Ann’s flashback. During the second version, we don’t get the full discussion between Maude and Freda, and we aren’t shown the photo. The narration assumes that after the flashback Martin is vivid enough in our memory. What replaces the insert of Martin is a reverse shot of Freda, describing Martin.

Now that we know she was Martin’s mistress, we’re in a position to appreciate how her dialogue and expressions conceal their relationship.

Similarly, the first version stresses the cigarette box that Ann inadvertently says she recognizes. The second version contents itself with a long shot, because now no one will question her about it.

The sense that the last path we see presumes the others has a more interesting side effect. Sometimes we get the sense that in the last go-round the character is mysteriously aware of the other paths she or he has taken. This happens in Sliding Doors and Run Lola Run, when each heroine seems to have learned from her experiences in the parallel worlds. And multiple-draft films like Groundhog Day and Edge of Tomorrow make this learning process essential to the action. The premise is illogical, but narratives often violate logic.

Something similar happens in the film (but not the play) of Dangerous Corner. Alone with Charles on the patio, Ann accepts his marriage proposal because the cigarette box she saw at Martin’s, now in Freda’s hands, made her realize she’s “been a fool.” We have seen the flashback in which she fought off Martin and accidentally killed him. The flashback isn’t in the play, and it’s especially interesting because presumably that scene really did take place, in both paths. That is, the evening orgy of confessions is one hypothetical alternative, but the manner of Martin’s death a year before, revealed in this path, is an actual event. It’s as if reliving Martin’s attack during the first path has made Ann appreciate Charles’s genuine love for her.

My seventh principle also bears on the last path we encounter. It’s a simple one: We take the final path as the correct one. Since endings are typically the place where all is revealed, we’re prepared to accept the last reiteration as what really happened. (This can be reinforced by a character’s learning curve, such as Ann’s.) Dangerous Corner is a good example.

I think we’re urged, by the second intertitle but also by the overall arrangement of the parts, to see that the quiet maintenance of civility predominated during that evening. The more sordid alternative, though given at much greater length, is what’s under the surface but what will never be acknowledged. The truth of the theft and Martin’s death, along with all the love affairs and animosities spilled out in the first version, will never be brought to light.

Other factors give the second version more weight. There are the shots I mentioned that stress the Ann-Charles relationship more, but for me the clinchers are more structural than stylistic. For one thing, both Ann and Charles play the role of raisonneur–the character(s) who explains the action and articulates central themes of the piece. In both the first path and the second, Ann echoes Priestley’s notion of our limited knowledge, saying that we prefer half-truths to the complete, factual account, the one that only God knows. And in both paths Charles warns against telling the truth, as it presents a “dangerous corner” that could lead to a smash-up. No other characters reflect so fully on the consequences of letting everything out.

Another structural factor involves the film’s beginning and the ending. The 1933 section starts with a scene in which Charles calls on Ann and once more asks him to marry her. Thanks to the primacy effect, this pair of characters becomes more salient in what follows than the married couples do. As a result, the epilogue, set on a terrace like the first one, harks back to the indubitably actual, pre-fork opening.

The fact that the movie ends with the creation of a couple, the uniting of the two characters who are the most self-aware and sympathetic throughout the film, reinforces the sense that this is the “real” outcome.

I hope you’ll read the whole essay. My purpose is to understand the dynamics of a small but increasingly common body of films. Forking-path films ask us to construct stories in unusual ways, but we quickly learn what guidelines to follow. Once the format exists, filmmakers take up the challenge of mastering it, stretching it, applying it to new material. (Edge of Tomorrow was sometimes considered Groundhog Day Goes to War against Aliens.) As filmmaking practice develops, we can track contemporary experiments and relate them to earlier efforts they are based on.

In addition, it’s worth knowing that a fairly sophisticated filmic treatment of the format appeared eighty years ago. In the essay, I find even earlier examples. And in a period when every movie seems at least 130 minutes long, it’s nice to encounter one that offers so much narrative complexity in about half that running time.

More generally, I think that probing this body of film shows the value of systematically studying narrative formats of any type. We’re used to talking about genre as a fluctuating body of conventions, but we should also study conventions that cross genres—conventions of story worlds, plot structure, and narration. These conventions can prod us to execute some unusual mental moves. Filmmakers are practical psychologists, and they’ve learned how to tease and tickle our minds. What-if movies are just one example of how norms and forms guide our understanding of story.

My first quotation from Priestley comes from Three Plays and a Preface (Harper and Brothers, 1935), ix. The second comes from Two Time Plays (Heinemann, 1937), ix.

In production, Dangerous Corner seems initially to have replaced Priestley’s what-if premise with more of a whodunit plot, while incorporating subjective sequences. According to a Variety review of an 83-minute cut before release, the explanations offered for Martin’s death by the various men are followed by something fairly unusual.

Surprise and twist, with increasing suspense, are accomplished through a shift from the factual elements to subjective processes on the part of the three women most closely related–as wives or sweethearts–with the suspected men. An innocent revolver shot precipitates the terrific speculations as each woman wonders if her man has killed himself in an adjoining room (Daily Variety, 13 September 1934, p. 3).

By the final release, however, the film had lost twenty minutes, and the result was the version we have. I haven’t seen versions of the screenplay, but I bet they’d be interesting. We’re left with other what-if questions, this time about the production of the movie itself.

Some of the basic concepts I employ here and in “Film Futures” are explained in the essay “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative,” online here. That essay is in turn applied to The Wolf of Wall Street in this blog entry.

Dangerous Corner (1934).

GRAVITY, Part 2: Thinking inside the Box

Kristin here:

In my previous entry, I described Gravity as an experimental film. I had thought of it that way ever since seeing trailers for it online back in mid-September. I described it as reminding me “of Michael Snow’s brilliant Central Region, but with narrative.”

Last time I developed that notion in more detail and analyzed the narrative structure of the film. Now I’ll analyze the experimental aspects of the film’s style and the dazzling means by which they were created. I don’t have the technical expertise to explain the inventions and ingenuity that went into creating Gravity, so I have sought to pluck out the best quotations from the many interviews and articles on the film and organize them into a coherent layout of how its most striking aspects were achieved.

As in that entry, SPOILER ALERT. This is not a review but an analysis of the film. Gravity does depend crucially upon suspense and surprise, and I would suggest not reading further without having seen the film.

Screaming on the set

I’ve written about Cuarón’s use of long takes, a stylistic device that has drawn a huge amount of attention in the press. Here the editing is so subtly done that even someone like me, who typically notices every cut, missed a lot of them during early viewings. There are bursts of rapid editing, as when the ISS is struck by debris and is destroyed, or more conventional cutting, as when the camera follows the Chinese pod and surrounding remnants of the station as they heat up in the atmosphere.

The long takes go beyond what Cuarón has done before. In Variety, Justin Chang describes one major difference: “As the movie continues, the filmmakers even add a new wrinkle, which Lubezki calls ‘elastic shots’: Takes that go from very wide shots to medium closeups, then segue seamlessly into a point-of-view shot, so the viewer is seeing the action through the character’s eyes, right down to the glare and reflections on a helmet visor.” Such moments are rare in Gravity, but one occurs in the “drifting” portion, shortly after the segment laid out above:

As Cuarón has pointed out, his long takes eliminate the need to cut in to closer views: “The language I have been working on with Chivo in these recent films is not one based on close-ups. We include close-ups as part of a longer continuous shot. So this all becomes choreography.” Another point he makes in this and other interviews is the influence of Imax documentaries on Gravity: “My process of exploring long takes fits in with that IMAX documentary notion, because when they capture nature it isn’t like they can go back and pick up the close-up afterward. There isn’t that luxury in space either. So then it falls to us to find a way to deliver that objective view, but then transform it into a more subjective experience.” Hence the “elastic shots.”

The long takes often dictate a refusal to cut in to reveal significant action. There is the moment in the epic opening shot, for example, when Shariff is suddenly killed in the background while in the foreground Kowalski tries to help Stone detach from her mechnical arm and into the shuttle. Did you see the flying piece of debris that struck his head? I didn’t, not until the fourth time I watched the film, knowing that it was coming and determined to spot it. It’s there, a little white dot that flashes through the frame in a split second. Shariff’s abrupt movement to the side, stopped with a jerk by his tether, is what we spot, since his bright white suit moves so suddenly and quickly, ending up against the pitch black of space:

A great deal happens in such moments of action, and we are left to spot what we can.

If these long takes are dazzling on the screen, think what they must have been like to witness being made. Lubezki has suggested how complicated the long takes in Gravity and earlier films were to shoot:

There are very few director/cinematographer teams working today as well known for a certain aspect of filmmaking as you and Alfonso are, which is that long extended take, or the seamlessly edited take. What it is like actually shooting those scenes?

I’m going to tell you something, the reality is that the movie was so new that when we finished a shot we would get so excited people would scream on set—probably me before anybody else. There were moments when we were shooting and Alfonso said ‘cut’ we would all just jump and scream out of happiness because we’d achieved something that we knew was very special.

In Children of Men, we also had moments like that. When we finished the first shot inside that car [the aforementioned ambush scene], the focus puller started crying. There was so much pressure that, when he realized he had done a great job, he just started crying.

There is something breathtaking about the achievement of complex long takes that seems not to arise from any other cinematic technique. I have seen Russian Ark three times now, and each time I feel an inexplicable tension, wondering whether the camera team will make it through the entire one-shot film without a mistake. I’ve already seen it happen, and yet it still seems unbelievable that they did.

In Gravity, of course, the “long takes” were not actual lengthy runs of the camera. Nor were they, as in Children of Men, several camera takes stitched together digitally to create lengthy single shots. Rather, they were created in the special-effects animation, with the faces of the actors being jigsawed into them through a complex combination of rotoscoping and geometry builds. (See this Creative Cow article for an example.)

The choice to present the action in long takes was crucial to the look of the film. Most films set in space rely heavily on editing, since for decades the special effects needed to convey space walking were best handled in a series of shots. In Star Trek Into Darkness, Kirk flies through space toward a spaceship breaking up and surrounded by debris, a situation somewhat comparable to that in Gravity. The sequence is built up of many short shots of Kirk against shots of dark space, point-of-view shots through his helmet, and cutaways to characters inside the Enterprise conversing with him via radio. Here’s a brief sample of four contiguous shots:

The sequence conveys little sense of weightlessness, partly because the actor adopts a traditional superhero-style flying pose. With no air in space, there would be no need to compact oneself into a streamlined shape. The fast cutting keeps repeating similar compositions, as with frames 2 and 4 above, with the fast editing presumably intended to generate excitement. (Star Trek Into Darkness has at least 2200 shots in a little over two hours, while Gravity has about 200 in 83 minutes.) Gravity‘s success in creating a realistic environment in space is dramatically evident when contrasted with this film’s more traditional outer-space conventions.

But it turns out that the commitment to the long take led Cuarón toward less common choices about editing, staging, and lighting.

Follow the bouncing axis

For much of the film, there is minimal spatial stability for the characters or for our viewpoint into the diegetic world. There is no ground, so we cannot imagine the camera resting on anything. When outside the space vehicles, the camera moves nearly all the time. In an interview with ICG Magazine, director Alfonso Cuarón was asked, “So with the camera and characters in constant motion and changing perspective, how did you figure up from down?” He replied:

There is no point of departure because there is no up or down; nobody is sitting in a chair to orient your eye. It took the animators three months to learn how to think this way. They have been taught to draw based on horizon and weight, and here we stripped them of both.

Undoubtedly many scenes contain an axis of action running between the characters, but it is not of a traditional kind. Unlike in a classically edited film, in Gravity‘s action scenes in space, the axis is in constant, fleeting motion, and any given center line between two characters must in quick succession run not only left and right but also up and down, diagonally, in almost any direction. Any given screen direction set up by the axis is ephemeral and offers little to help orient us spatially. Eyeline directions mean very little, since there are few cuts to things that the characters have seen offscreen. (True, when characters look offscreen, they establish eyelines, and the camera sometimes pans from Stone or Kowalski to some object they have been looking at. But a pan from a person to an object automatically establishes the spatial relations between them, whether or not the character is looking at the object.)

As a result, the spatial cues used in continuity editing system are not so much eliminated as made irrelevant for long stretches. That system is meant, after all, to guide our understanding of the story space across cuts. There are exceptions, such as a brief shot/reverse-shot exchange: Stone, loosely attached to the International Space Station (ISS) by ropes, pleads with Kowalski not to untether himself from her and float away to die in space, and he insists that it is the only way to allow her to live. When Kowalski and Stone, tethered together, travel toward the ISS, he is always at screen left, she at screen right, with the strap joining them stretched out as a sort of visible axis of action; straight cut-ins to close views of each character, and even at one point Kowalski’s point of view, obey the 180-degree rule and create an almost conventional scene. Actions inside the spacecrafts are more oriented as well. In the ISS Stone moves weightlessly through a series of pods, all the while maintaining screen direction. Similarly, inside the vehicles, especially late in the film when Stone is strapped into seats, she is usually upright, her head oriented toward the top of the frame. Some sustained actions in space also keep her right-side up, as when she removes the bolts holding the parachute cords to the Soyuz landing vehicle.

In part because of such orienting devices, we are seldom seriously confused about where the characters are, or at least not for long. Otherwise we would not be able to comprehend the story action. Still, compared to typical classical films, Gravity conveys little sense of spatial stability. The disorienting simulation of weightlessness for characters and camera dominates the scenes outside the vehicles and creates a style that can truly be called experimental.

Take the brief segment (about 14 seconds) below, from the 13-minute opening shot. Stone has been standing at the end of a large mechanical arm which gets knocked off the space shuttle by a piece of hurtling debris. It spins rapidly, with the camera framing it from long-shot distance. The camera is not entirely static, reframing slightly, but we can see the earth in the background fairly clearly. Stark sunlight comes from offscreen left, and as Stone’s body whips through space, the shadows move accordingly around her, with the back of her body in deep shadow in the first frame and then her front shadowed in the second:

The fact that the light source, the sun, is offscreen left during this spinning segment suggests that the camera and hence our viewpoint are in a stable position. Yet that position is maintained for only a short time. At this point in the shot, the camera is essentially waiting for her to draw near in order for it to execute a change that will govern the penultimate part of the lengthy shot.

That happens when, after she has spun wildly toward and away from us several times, the camera “attaches” to her, so that we are now seeing her in medium shot and spinning with her. Instead of seeing the earth clearly, we see her while the blurred surface of the earth and the blackness of space alternate rapidly. This was the technique that led me, when I first saw the film’s trailers, to compare Gravity to Michael Snow’s Central Region:

Being closer to Stone, we can see more clearly the shadows coming and going; her face is sometimes illuminated brightly by the sun and sometimes in near darkness:

The function of the attachment to Stone, apart from allowing us to see her fear and confusion, is to show us that her hands are working to detach her from the arm, as a tilt down reveals:

As she soars off the arm and tumbles into the black depths of space, the camera leaves its “attachment” to her, and she spins away from it:

Cuarón’s commitment to the long take thus made him rely more than usual on events taking place within the frame–camera movement and figure movement in particular. Yet these movements had to occur in a microgravity environment radically different from the earthbound surroundings of Children of Men and Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. This new constraint led to some technological innovations of remarkable originality.

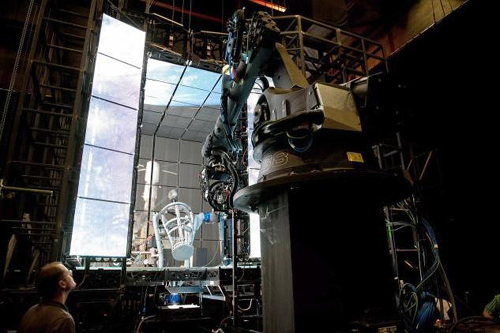

The LED Light Box

Early on it became clear that moving the actors through space on wires would not create the desired realism of weightlessness, and obviously they could not be whipped about and tumbled in ways that the film ultimately achieved. The actors would have to be relatively static, with the illusion of movement created through other means. One of the main challenges was to have the lighting on their stationery faces support that illusion. And it would have to be done perfectly in order to achieve the photorealistic depiction of space that the filmmakers were after.

Usually in watching a film heavily dependent on CGI, one notices elements that have been assembled into a single composition but don’t quite match each other. A matte painting that isn’t lit from precisely the same angle as all the other components stands out from the rest (as, it has to be admitted, happens in the best of CGI scenes, including those in The Lord of the Rings). The problem was solved for Gravity using the LED Light Box, a device frequently mentioned in the press coverage of the film but seldom explained. (See image at the top.) The concept is truly revolutionary, although I am not sure to what extent it would work for other films that did not present such peculiar challenges.

In American Cinematographer‘s article on Gravity, “Facing the Void,” cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki explains why consistency of lighting is crucial and how he came up with his solution:

Lubezki emphasizes that Gravity‘s blending of real faces with virtual environments posed a tremendous challenge. “The biggest conundrum in trying to integrate live action with animation has always been the lighting,” he says. “The actors are often lit differently than the animation, and if the lighting is not right, the composite doesn’t work. It can look eerie and take you to a place animators call ‘the uncanny valley,’ that place where everything is very close to real, but your subconscious knows something is wrong. That takes you out of the movie. The only way to avoid the uncanny valley was to use a naturalistic light on the faces, and to find a way to match the light between the faces and surroundings as closely as possible.”

This challenge led Lubezki to imagine a unique lighting space that was ultimately dubbed the “LED Box.” He recalls, “It was like a revelation. I had the idea to build a set out of LED panels and to light the actors’ faces inside it with the previs animation.” Lubezki conducted extensive LED tests and then turned to [special effects head Tim] Webber and his team to build the 20′ cube and generate footage of the virtual environments, as seen from the actor’s viewpoint, to display inside it. While constructing the LED Box, the crew also solved problems involving LED flicker and inconsistencies.

Inside the LED Box, the CG environment played across the walls and ceiling, simulating the bounce light from Earth on the faces of Clooney or Bullock, and providing the actors with visual references as they pretended to float through space. This elegant solution enabled the real faces to be lit by the very environments into which they would be inserted, ensuring a match between the real and virtual elements in the frame.

This ingenious approach largely did away with traditional three-point lighting in the exteriors. As Lubezki explains in the AC article,

When you put a gel on a 20K or an HMI [Hydrargyrum medium-arc iodide], you’re working with one tone, one color. Because they LEDs were showing our animation, we were projecting light onto the actors’ faces that could have darkness on one side, light on another, a hot spot in the middle and different colors. It was always complex, and that was the reason to have the Box.

The crucial point here is that the lighting was being created by playing the previs animation of the earth, space, the moon, and the large reflecting objects like the space shuttle on the sides of this 20′ by 10′ box. In other words, the moving images from the nearly finished special effects were used to light the faces of the actors, and those faces were later joined to those very same special effects, in a more polished form, to create the final images.

Lubezki gives an excellent description of the Box in his interview with Bryan Abrams, a series of responses which is worth quoting at length. Note that Lubezki refers to the Box as an LED monitor–essentially a giant television screen turned inside out and surrounding the actor:

Can you touch upon some of the pieces of technology and equipment that were created to make Gravity possible?

To make this movie we used many different methodologies. For one of them, we invented this LED box that you’ve probably read about, which is basically this very large LED monitor that is folded into a cube. So all the information and images that you input into this monitor lights the actors, and you can input all of the scenes that were pre-visualized to create the movie—all the environments that we had created—and you can input them into this large cube so space itself is moving around the actors.

So it’s not Sandra Bullock spinning around like crazy, it’s your cameras.

Yes, instead of having Sandra turning in 360s and hanging from cables, what’s happening is she’s standing in the middle of this cube and the environment and the lighting is moving around her. The lighting on the movie is very complex—it’s changing all the time from day to night, all the color temperatures are changing and the contrast is changing. There were a lot of subtleties that you can capture with the box, subtleties that make the integration of the virtual cinematography and the live-action much better than ever before.

The effects of the LED projections are visible in the changes on Stone’s face in the extended example above. Here’s a brief example of changes on Kowalski’s face in the opening shot:

The harsh light in the right frame above is a real lamp. The LEDs could not produce a local, hard light intense enough to simulate the sun. The team placed “a small dolly and jib arm alongside the actors” with a lightweight spotlight. This was moved “according to the progression of the virtual sun.” Such harsh light was necessary because outside the atmosphere there is nothing to filter bright sunlight. Several moments where the actors’ faces and suits are severely overexposed reflect this technique:

The Box also contained a large video monitor, visible to the actor, which displayed the previs animation. Lubezki explains: “This was wonderful in a couple of different ways. The actor sees the environment and how objects are moving in that environment, and at the same time we can see the interaction of that light on the actor. We capture true reflections of the environment in the actor’s eyes, which makes the face sit that much better within the animation.”

Previs as environment

The fact that almost everything in the film was created digitally–including the space suits in which the actors bob and spin in the exteriors–necessitated an extraordinary amount of planning and pre-production. “Pretty much we had to finish post-production before we could even start pre-production, because of all the programming,” Cuarón says. This was one reason why there was such a long gap between Children of Men (2006) and Gravity. Four and a half years were spent in developing the new technology and preparing to shoot.

The team started with geography:

The filmmakers began their prep by charting a precise global trajectory for the characters over the story’s time-frame, so that Webber and his team could start creating the corresponding Earth imagery. Cuarón chose to begin the story with the astronauts above his native Mexico. From there, the precise orbit provided Lubezki with specific lighting and coloring cues. The cinematographer recalls, “I would say, ‘In this scene, Stone is going to be above the African desert when the sun comes out, so the Earth is going to be warm, and the bounce on her face is going to be warm light.’ We were able to use our map to keep changing the lighting.”

Next, the filmmakers defined the camera and character positions throughout the story so that animators at Framestore could create a simple previs animation of the entire movie. [“Facing the Void”]

Lubezki was completely involved in planning the digital lighting. He recalls, “I would wake up at 4 a.m., turn on my computer, I’d say good morning to my gaffer and start working on a scene. I would say, ‘Move the sun 60,000 kilometers to the north.’ That way I could put the lighting anywhere I wanted.”

The reference material for the earth imagery came in part from NASA reference footage and photos. You can get a sense of these from the NASA films posted online, although these are mostly done in fast motion, unlike the ones the filmmakers would have used. One good example is “Earth HD.” There, at 2:25 and again at 2:41, one of the most recognizable locations on earth, the Nile Valley and Delta, are visible:

A similar image of the Nile appears on earth as Kowalski and Stone slowly make their way from the space shuttle to the ISS, with him asking her about her hometown and any family she might have waiting for her. (I was also happy to see the area of the site where I work in Egypt, Tell el-Amarna, which lies about midway between the Delta at the upper left and the large bend in the river.)

This geographical plotting included some ellipses. Although commentators have suggested that the film takes place in real time, or nearly so, there are temporal gaps. Shortly after the first pass of the speeding debris field, Kowalski tells Stone to set her watch’s timer for 90 minutes, since he calculates that is when they will encounter the orbiting debris again. That happens when she exits the Soyuz vehicle to detach its parachute. She again sets her timer for 90 minutes, and the debris field shows up at the Chinese station, battering it to the point where it sinks into the atmosphere and breaks up into chunks melting from the friction of reentry. Thus a little over three hours should be passing in the 83 minutes of screen duration.

Cuarón more or less confirms this timetable when he describes the creation of the previs: “The screenplay describes a journey that takes place mostly in real time, with only a couple of time transitions. We travel around Earth three times, so in previs we planned out visuals with specific knowledge of where we’d be in orbit at any given point in the story, whether it was in sunlight or darkness.”

In the film there are very few places where we can assume a significant ellipsis occurs. After Stone enters the ISS, sheds her helmet and suit, and drifts in a fœtal position, there is a gap. It’s probably not long, since she still holds some hope of going to rescue Kowalski, but she pauses to recover after her trying experience. Later, there is a cut from her inside the landing module, not in the suit, to her emerging from the hatch fully suited up–a gap we might assume to be ten minutes or so. Most notably, the cut from the nighttime shot of the earth that includes the aurora borealis at the right to the extreme close-up of frost on the window ellides a longer stretch of time. Stone has become hoarse in the interval as she tries to send a mayday message via radio. In other cases, such as Stone and Kowalski’s slow journey toward the ISS, time seems to be somewhat compressed though not ellided.

Staging without a stage

A lack of depth cues hampered the animators charged with creating the previs. The absence of one major depth cue, aerial perspective (the tendency of layers of space in the distance to turn successively bluer and blurrier due to the filtering quality of the atmosphere), caused problems. Visual-effects supervisor Tim Webber, of the effects house Framestore, remarks:

You can’t rely on aerial perspective because without atmosphere there is no attenuation of image due to distance. And the lack of reference points [in space] can get you into trouble, like not being able to tell if the character is coming toward you or the camera is moving toward him. Even though we played it straight with respect to science and realism, we did put in more stars than you’d be able to see in daylight, just so there’d be some frame of reference to gauge movement.

Presumably Webber is referring here to the movement of the characters and objects through space, not the camera movement. (The lack of any “frame of reference” against which to sense movement is part of what makes the Star Trek scene illustrated above seem so unsophisticated.)

Naturally, since the actors were not standing on a floor or solid ground, the blocking was difficult, but it also had to be planned completely in advance:

Cuarón laughs as he recalls the surprises inherent in blocking characters in a zero-gravity environment. “The complications are really something because you have characters that are spinning. Say you want o start your shot with George’s face and move the camera to Sandra, who is spinning at a different rate. You start moving around her, and then you start to go back to George, only to realize that if you go back to George at that moment, you will be shooting his feet! So then you have to start from scratch. Sometimes you find amazing things accidentally, but sometimes you have to reconceive the whole scene.” [“Facing the Void”]

Finally, after all the planning, the previs animations were made. These had to be refined considerably so that they could adequately serve in the Light Box to illuminate the actors’ faces. According to Bill Desowitz, “The previs was so good, in fact, that the daughter of cinematographer Emmanuel (“Chivo”) Lubezki thought it was the real movie.”

The previs became so sophisticated because it evolved during preproduction. Cuarón recalled that Lubezki’s inspiration to create the LED Light Box changed the planning tactics:

Then that kind of had a ripple effect back into the previz, because originally they were going to just be a model that we could look back at, but we realized that the previz was more than that. That was something that [James] Cameron kept on talking about. He would say “I don’t use previz anymore, I use it as if it is the first painting on a canvas.” In other words it was the stuff that you kept on painting on top of and the thing with that is that it became very clear that in order to use these technologies, we needed to program stuff and the previz was going to have to be precise in terms of camera movements, choreography, timing and light.

As a result, the movie changed very little during principal photography. Senior visual-effects producer Charles Howell told American Cinematographer: “I think there were only about 200 cuts in the previs animation, [whereas] an average film has about 2,000 cuts. Because these shots had to be mapped out from day one, many of the lengthy shots didn’t really change in the three years of shot production. Because we did a virtual prelight of the entire film with, the whole film was essentially locked before we even started shooting.” [“Facing the Void”]

David counted 206 shots in Gravity, not including the two opening titles about life in space being impossible. This suggests that Howell is right, and that the film underwent little revision after the planning phase.

Several years ago I suggested on this blog that animated films, notably those of Pixar and Aardman, were on average better than mainstream live-action films because they had to be planned so carefully and thoughtfully. Gravity, being very close to an animated film, provides more evidence for that claim. Not that thought, time, and money can guarantee quality, but they certainly narrow the odds.

Iris in

The Light Box technology is astonishing enough, but within its confined space there also had to be a way to photograph the actors. In Lubezki’s interview with Bryan Abrams, he explains:

So we built the box, but that wasn’t it. To be able to shoot inside the box, we had to build a special rig that holds the camera and moves with motion control. So we had people build a very narrow, lightweight but sturdy rig to control the camera. If you imagine the big box of LEDs, it has a gap that is almost a foot and a half or two feet wide, and the camera has to go into the box and make all these moves to make the audience believe that Sandra is turning and turning, but it’s really the camera and the environment in the box that is moving. So we built the box, the rig, and then used a company called Bot & Dolly. These guys are from San Francisco, and they use robots from the automotive industry. They redid all the software for us, so we were able to use these robots to move the cameras and the lights around the actors. It was just a big ballet of gadgets and new technology for the film.

Bot & Dolly is a San Francisco company specializing in robots for the automobile industry. It built or perhaps modified an elaborate rolling, multiply-jointed camera mount called Iris especially for Gravity. It has been used in other features and in ads since then. (See image at the bottom.) An impressive demo film shows the Iris gracefully writhing about, quickly pointing the camera in many directions. (The camera in the film is a Red, though Gravity used an Alexa.) According to ICG Magazine, “The firm devised a Maya-based series of commands that allowed Framestore animators to direct the robots in ways that matched previs action in precise detail.” (Maya is the industry standard computer animation program.)

Typically this camera was inserted through an opening in the Light Box and swooped around the actor, who stood in a gyroscopic basket, seen in the production photo below. The photo shows one side of the Box open, though this would not be the case during shooting:

The combination of the Light Box and Iris made it possible to blend the special-effects shots and the live-action photography of the actors so smoothly that there is no “uncanny valley” effect, no sense of an obvious matte painting stuck into the middle of an image. The shots in Gravity are all photorealistic to a degree that is rare, if not unique, in recent effects-heavy films.

Iris brings us back to the comparison with Central Region. Snow built a special camera mount (below) designed to allow his images to rotate freely in almost any direction. During the three-hour film the camera never repeated any of its trajectories. Some images were close views of the pebbles on the ground; others were upside views of the bleak Canadian mountains in the distance. A nighttime segment was completely black except when the moon occasionally swept through the frame. The one area that the camera didn’t survey was the camera support itself, the “central region” of the title.

The vital difference between Snow’s machine and Iris is that the new system has no fixed anchor. Not only does it slide on a track, but everything it photographs can be digitally altered to erase any traces of the machine. It moves with entire freedom through a constructed space that has no central region, no fixed point around which everything else revolves.

Puppeteers and eyes

Gravity‘s utterly spherical space, beyond anything we normally find in commercial cinema, placed unusual demands not only on camera movement but also upon the actors’ blocking and performances. Our first entry on Gravity begins with a quotation from Sandra Bullock, which included the statement, “No character was like Stone, no film set was ever like these sets, not one member of this crew had ever done this before.” That may seem an exaggeration until one grasps how Bullock and Cuarón’s team built her character.

We all know from infotainment coverage that Bullock was isolated in the Light Box through entire days and that it was a trying experience. What doesn’t come through in such accounts is that she was often enclosed in the gyroscopic basket, visible in the photo of the Iris rig and Light Box above, as well as in the same setup visible behind Cuarón in this photo:

That was only the start of it. Anne Thompson’s interview with Cuarón and producer David Heyman reveals some of the details of blocking a character who is unrestricted by gravity:

AC: The physical aspect, not anybody can do what she did. On the one hand the physical discipline she went through to make this film, the training and the workouts. She also has an amazing capability for abstraction. Those emotional performances, it was as if they were an exercise in abstraction, like she was bonded to very precise cues. And physically that was very difficult: she trained and practiced like crazy, together with the stunt people and special effects. And the puppeteers from “War Horse” were helping her, supporting a leg or an arm, all the floating elements, they were creating approaching objects toward her in perfect timing. Then after she practiced so much her whole concern was only about emotions and performance.

Imagine a ballet dancer with really strict physical discipline in terms of what a body has to do, positions and precise choreography, who goes through months of training for one choreography so when they are performing they have expressiveness and emotion.

What was the most challenging scene to realize?

David Heyman: When Sandy comes into the ISS for the first time. She takes off her suit, then goes into fetal position, all in one shot. It was the most difficult. All the objects, getting the suit off, and into fetal position in such a way that it felt effortless, not as it was–she was sitting on a bicycle with one leg tied down leaning back in a 12-wire rig, with puppeteers. One of the things you forget about Sandy’s performance, which seems so truthful, is all the effort and physical exertion that went into making it, the precision of the technical aspects. She had to move her hands at a third of speed — zero G –while talking. Each shot connects with the next at very precise points where her head began and end and begin and end. She’s on a bicycle stringing uncomfortable with people moving around on 12 wires, through it all, with no gravity. Physically the body must not show the tension, so it looks effortless. What I loved about it is the performance behind the visor shines through, her eyes. You can’t slouch your shoulders to show sadness or weight, it’s just the eyes.

Bullock did all this with four 10′ by 20′ walls of LEDs projecting moving images of the earth and of exploding space stations around her. I think it is safe to say that this was a unique kind of performance.

The sounds of silence

As the film’s ominous opening titles point out, there is no sound in space. In keeping with the overall attempt to duplicate the effects of weightlessness immersively, Cuarón’s team limited the track to two types of sound: diegetic sounds heard by the characters and a non-diegetic, modernist musical track. In an interview with Cuarón, Wired‘s Caitlin Roper pointed out that there was an explosion in one of the trailers. Cuarón replied:

Yes, but that’s just the trailer. I honor silence. The only sound you hear in space in the film is if, say, one of the characters is using a drill. Sandra’s character would hear the drill through the vibrations through her hand. But vibration itself doesn’t transmit in space—you can only hear what our characters are interacting with. I thought about keeping everything in absolute silence. And then I realized I was just going to annoy the audience. I knew we needed music to convey a certain energy, and while I’m sure there would be five people that would love nothingness, I want the film to be enjoyed by the entire audience.

As in other areas of the film, we see the compromise between an experimental technique–an attempt to suggest the silence of space–and the desire to provide something more familiar for the broad audience. In this case, music acquires an expanded role, substituting for sound effects and conveying the rapidly shifting emotions of the scenes.

Sound effects are not entirely eliminated. Many sounds that the astronauts would hear via vibrations of things they come into contact with are included. In some cases these are fairly clear, as with the voices heard within their helmets–their own voices or others’ via radio. Other effects are heard in a distorted fashion. Glenn Freemantle, the supervising sound designer and editor, describes the process:

“When [Bullock] is in the suit, you hear her voice and her breathing, and you hear through her suit when she is in contact with things,” he explains. His team captured sounds by recording with contact mics at car plants and hospitals. “We even recorded through water with a [submerged] guitar,” he recalls.

One obvious example of distortion comes in the opening scene, when Stone is unscrewing bolts and sliding a panel out of the transmitting device she is working on. The sounds of the bolts and the sliding metal are audible but muffled, as though they were recorded under water or electronically manipulated.

Yet other sound effects not heard by the characters were relegated to musical expression. As Angela Watercutter put it in a Wired article based on interviews with Cuarón and composer Steven Price,

Every time there’s a collision in the movie the audience doesn’t hear a bang – they hear a sonic boom. The same goes for the characters’ — and, by extension, the audience’s — feelings of anxiety, claustrophobia, and agoraphobia. Much of what is seen in Gravity is terrifying, and when the audience can’t hear the horror of a space shuttle breaking apart or an airlock flying open, Price had to fill the void with his nerve-wracking score.

Cuarón dictated that one of the rules for the film’s score was the eliminating of percussion, to avoid the “cliché of action scoring.” Watercutter continues:

As a result the score for Gravity serves as more than just musical accompaniment – it also provides the movie’s sound effects. There are some non-music sounds that would be space audible, like the ones transmitted by vibrations characters feel in their spacesuits, but for the most part everything that happens in open space is accompanied only by Price’s music and the voices of Stone and astronaut Matt Kowalski (George Clooney), which “freed up the rest of the frequency spectrum for me,” Price noted.

Price used a mix of organic and electronic sounds to meld the natural world of space with the mechanical world one of the space exploration. There are also moments where he took an analog instrument – a cello, for example, or even a human voice – and ran its notes through a synthesizer or processor in order to create a whole new sound. And for the opening song on the score, “Above Earth,” Price took a track he was already working on and slowed it to about 1/60th its original speed. “Basically,” Price said, “what you’re hearing is the space between the notes.”

In an interview with Rolling Stone, Price discussed some of the aesthetic principles and functions he aimed for with his score:

Really it was all very much led by the character of Ryan. I tried to be with her all the time. The idea was that the music was up there in space and we made it very immersive and used a lot of elements and a lot of layering so that things would move around you all the time. The writing of those elements and what they were, were always influenced by what Ryan was feeling and where she was emotionally in the whole thing. And also where the camera was, where things were moving and what point of view the camera was facing, whether it was looking at them or kind of looking through their eyes. Some of it was melodic and some of it was intended to underscore a kind of emotional journey, and then there were a lot of sounds that were there to express real terror. It was those two extremes, really, expressing the beautiful nature of where they were but also absolutely a massively terrifying situation.

With little expertise in musical analysis, I can simply say that I hear the score as a combination of traditional instrumental music and electronically synthesized instrumental music. Under this, typically in tense passages, there are abrupt or charging percussive emphases, not using percussion instruments but, in some cases, deep string chords. Scenes of damage or tension are sometimes accompanied by sounds like stressed, grinding metal. Other sounds like distorted, high-pitched radio waves (in the “ISS” and “Fire” tracks) are included, reminiscent of electronic music of the 1960s.

Other critics have offered suggestive descriptions. Justin Chang’s review refers to “Steven Price’s richly ominous score, playing like an extension of the jolts and tremors that accompany the action onscreen.” David S. Cohen and Dave McNary’s Venice festival coverage characterizes the track: “Much of the action, even the debris storms, plays out against eerie silence, broken only by the score. The silence is more startling after the score builds to deafening crescendos, then stops abruptly. But during the interior scenes, the rumbles and groans of failing space gear are as frightening as the roars of any classic movie monster — even more so because their source is unseen.”

Price has contributed a remarkable score, one which is highly original and yet completely motivated by the story situation it accompanies.

The space between

The immersive, 360-degree surrounding and sound fields made Gravity a natural for 3D exhibition, but they also posed unique problems. Given the long takes, the need for complex camera movements, the demands of the LED Box, and the complicated acting conditions, it would have been very difficult to shoot the film in 3D. In most scenes, of course, there were no real objects juxtaposed in different layers of depth in front of the camera. Even the actors’ placements in long shots would have be created digitally. So the project had to be converted to 3D. But this forced choice actually yielded strong results.

The press coverage of popular cinema has come to treat films shot in 3D (“native” 3D) as pure and admirable and films converted to 3D after shooting as crass and compromised. But is there all that much difference? Even Avatar, the film made with an intention of promoting the universal use of 3D, had some converted footage. With conversion technology improving, the notion of waiting until after filming to create a movie’s 3D is becoming less onerous. As Variety‘s David S. Cohen pointed out earlier this year, Iron Man 3, Man of Steel, Star Trek into Darkness, and Pacific Rim have been post-converted with little objection from the public or press.

That conversion techniques for generating 3D images are not inferior became much more evident during the early decision-making process for shooting Gravity. Nikki Penny, the film’s executive producer, took some test footage shot by in 3D to Prime Focus World, a conversion house that ended up doing 27 minutes of Gravity. The filmmakers were trying to decide whether to shoot the live action portions in 3D or use conversion. In an article on Creative Cow, Debra Kaufman explains what happened:

The production had done a test shoot in 3D, which involved placing the cumbersome 3D rigs inside the cramped space capsule. When Penny brought the 3D live action footage to Prime Focus World, she asked that they test 3D conversion by utilizing a single eye from the same footage. The results convinced Cuarón and producer David Heyman that conversion would not only look as good as shooting in native 3D, and would be much easier and more efficient to accomplish.

That is, the footage shot by one of the two lenses in the 3D setup was separated out. It was then treated as if it were native 2D footage and put through a conversion process to create a 3D image. The result resulted in 3D that was not inferior to the original native-shot 3D. The lesson, I think, is that the question is not usually whether a film is shot in 2D and converted; it’s whether it was planned to be completed as a 3D film (and has sufficient budgets and skills invested in it) .

Gravity couldn’t be shot in native 3D, since in most scenes there were not real objects juxtaposed in different layers of depth in front of the camera. Also, the camera was too cumbersome to fit into the space-capsule sets. With so much of the characters’ surroundings done as CGI, however, the conversion to 3D could be done concurrently with the filming. Kaufman describes the process at Prime Focus World, one of the firms that handled the conversion:

Unlike the more typical post-production 3D conversion, Gravity involved PFW working on the 3D conversion during production. The work on 3D conversion began with six months of pre-production, during which the production’s Stereo Supervisor Chris Parks worked closely with the PFW team to explain his carefully plotted depth map, which contrasted the vast emptiness of space with the tight, nearly claustrophobic quarters of the space capsules.

From the beginning, the challenge for Prime Focus World would be to make sure that the 3D converted footage integrated seamlessly with the extensive 3D CGI. Both the live action footage and CGI would be 3D, but 3D from two different worlds, conversion and visual effects – and they would both be active or “live” during the production process. At the same time, the PFW team wanted to retain the creative flexibility of its View-D conversion process, while integrating the stereo VFX universe. What made it trickier was that, unlike a completed film, Prime Focus would be working with work-in-progress shots and an open edit.

For more on the technical aspects of the integration of converted footage and CGI, along with an example of the stages that went into creating a single shot, see the Kaufman article.

In an essay on ICG Magazine, Vision3 stereo supervisor Chris Parks describes some of the narrative functions of the film’s 3D:

We had a virtual camera at Framestore that let us control depth functions. When Sandra floated off in space, we separated her slightly from the starfield, using 3D to make her feel very small. At another point we went very deep, when we see her POV as her hands reach out to those of another astronaut coming to camera. At the point when they make contact, we increased the interaxial to five times normal, then scaled it back down as they separate and drift apart.

Parks also comments on the scene where Stone and Kowalski look through the shattered windows of the space shuttle and a crew member’s dead body suddenly falls into the shot:

Alfonso asked how the 3D could make this more powerful, but without just throwing something out into the audience to make them duck. We decided to float a little Marvin the Martian doll out into the audience, which is a kind of fun, lighthearted tension-breaker, and then we whip-pan right off that to the dead astronaut, which makes the emotional revelation more jarring.

In fact the Marvin doll (derived from Chuck Jones’s Warner Bros. cartoons) comes diagonally forward from the depths of the shuttle interior, and the camera pans with it as it moves out of the ship past Stone, who watches it and then turns back to look inside again. The corpse falls into the shot from above left, but not out toward the audience. It bumps Stone’s helmet, and the camera pans to reveal it more fully and continue almost nonchalantly onward to show another dead astronaut further back in the shuttle interior.

Finally, Parks points out an expressionist distortion of space for subjective purposes in the dream sequence where Kowalski joins Stone in the Soyuz landing vehicle:

It’s a dream sequence that doesn’t reveal itself as such right away. To give a subconscious impression that something different was happening, we pushed the top right corner into the set while pulling the bottom left corner ahead, skewing the whole view. That sense of unease represents, to me, how 3D can be expanded beyond just giant VFX movies. It’s a tool that can be most effective in very small spaces, as this one shot reveals.

Outside the dream scene, we see the wall panel of instrument controls at an angle to the camera, with Stone in her seat at the left. During the dream, the panel is suddenly turned so that it is almost straight into depth, so that we are pressed up obliquely against it. Stone’s seat at the left is further away from it. The result is that the space is strangely skewed during the dream.

In all, shooting in long takes, building each shot with CGI yet including complex camera and figure movement, canceling the sense of horizons and ground planes, and enhancing all these choices through 3D, has resulted in a film in which stylistic patterning becomes an object of fascination in its own right.

Despite the occasional joke about a Gravity sequel, it seems unlikely that Cuarón will tackle similar subject matter and formal strategies in his next film. Dealing with space without horizons and characters without weight was a formidable task. At the end of his Wired interview, asked what his next film will be, he replied, “Any movie in which the characters walk on the floor.” Welcome back, axis of action.

Most of the frames used here and in Part 1 were taken from a New York Times article containing a clip from the opening shot with commentary by Cuarón.

Thanks to Stewart Fyfe, who shared links to some of the sources cited in this entry.

Film-industry pros share secrets in Vancouver

Kristin here:

Even while tempting us with many, many films, the Vancouver International Film Festival runs an event that could all too easily lure us away from viewing and into the world of film-industry gurus: the Film and Television Forum. Its website describes it as “four days of professional development for senior and emerging professionals, from financing to production, to marketing and distribution, to storytelling and engagement.”

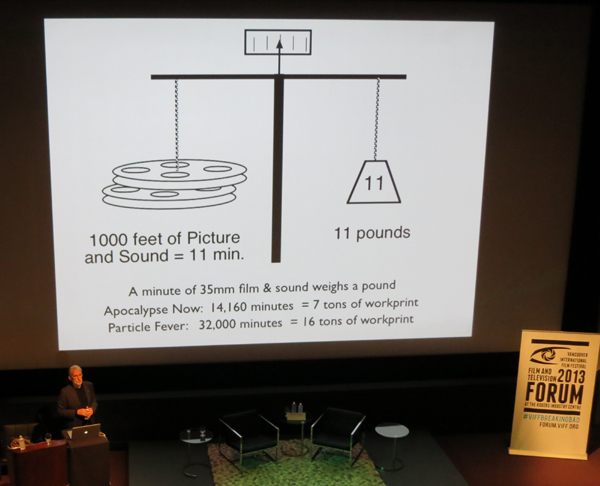

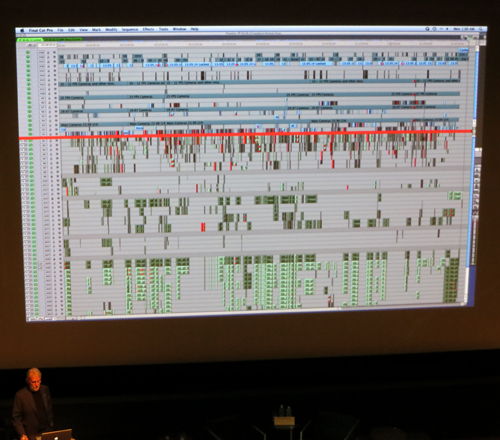

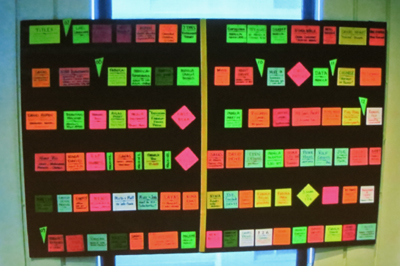

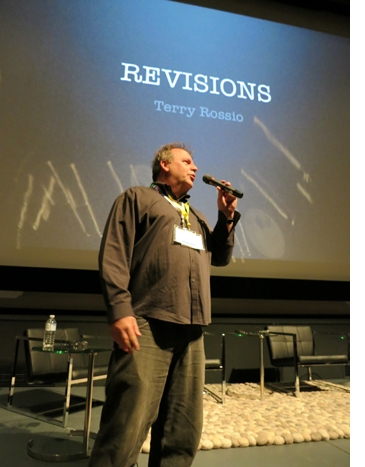

In an ideal world, we would attend all of the sessions, but they run concurrently with as many as eight films showing elsewhere. Two talks were particularly appealing, though, given our interest in the  practice of making films within the mainstream American industry. I slipped away to hear master-classes by Terry Rossio (screenwriter for all of the Pirates of the Caribbean films) and Walter Murch (editor of Particle Fever, shown at the festival, and sound designer on many films, including Apocalypse Now).

practice of making films within the mainstream American industry. I slipped away to hear master-classes by Terry Rossio (screenwriter for all of the Pirates of the Caribbean films) and Walter Murch (editor of Particle Fever, shown at the festival, and sound designer on many films, including Apocalypse Now).

Terry Rossio

Rossio’s modest title was “Revisions,” though his discussion ranged far beyond advice on how to rewrite a script. He immediately won over the audience, clearly many of them professional or aspiring screenwriters, by passing around a flash-drive and inviting anyone with a script-in-progress on their laptop to put some pages on it. He would end the session by making some impromptu revisions of those pages.

I’m not secretly working on a screenplay or even aspiring to write one, but if I were, I think I would have gleaned some valuable tips from Rossio’s talk.

Most panels and seminars tend to be too general, he said. They “focus on the business side, tell personal anecdotes,” and so on. He feels that it is probably impossible to teach screenwriting: “No, the better question is, can writing be learned?” Yes, but people must teach themselves.

Writing and revising

To Rossio, one crucial thing to learn is that finishing a story is not the end. One should have both doubt and faith: doubt that a story or scene is good enough, and faith that it can be better.

Revision, according to Rossi, is “talent reapplied.” One may have a limited amount of talent for writing, but it can be stretched by reapplying it over and over during the revision process.

Rossio is a big advocate of succinctly creating a strong visual sense in each scene. Even on Rossio’s desktop he comes up with a distinctive icon for each folder (see top): a Rubik’s cube for “Screenwriting,” a little gramophone for “Music,” and so on.

For Rossio, each scene should consist of:

- Opening image

- Key moment (character revelations, reversals, etc.)

- Throw (i.e., the setup for the next scene)

Apart from visual imagery, writing should be situation-based: “Every scene you write must be an obvious situation.” A screenplay is a string of situations, which creates a compelling interest in the scene. His example was two people discussing an important deal in a car on the way to a meeting. The dialogue might become boring because of the static setting, but the writer could make them experience car trouble and have their discussion outside the car while worrying whether they will make it to the meeting: “The easiest way to create interest is through some sort of dilemma.”