Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

David Koepp: Making the world movie-sized

Stir of Echoes (1999).

DB here:

For a long time, Hollywood movies have fed off other Hollywood movies. We’ve had sequels and remakes since the 1910s. Studios of the Golden Era relied on “swipes” or “switches,” in which an earlier film was ripped off without acknowledgment. Vincent Sherman talks about pulling the switch at Warners with Crime School (1938), which fused Mayor of Hell (1933) and San Quentin (1937). Films referred to other films too, sometimes quite obliquely (as seen in this recent entry).

People who knock Hollywood will say that this constant borrowing shows a bankruptcy of imagination. True, there can be mindless mimicry. But any artistic tradition houses copycats. A viable tradition provides a varied number of points of departure for ambitious future work. Nothing comes from nothing; influences, borrowings, even refusals–all depend on awareness of what went before. The tradition sparks to life when filmmakers push us to see new possibilities in it.

From this angle, the references littering the 1960s-70s Movie Brats’ pictures aren’t just showing off their film-school knowledge. Often the citations simply acknowledge the power of a tradition. When Bonnie, Clyde, and C. W. Moss hide out in a movie theatre during the “We’re in the Money” sequence from Gold Diggers of 1933, the scene offers an ironic sideswipe at their bungled bank job, and a recollection of Warner Bros. gangster classics. When a shot in Paper Moon shows a marquee announcing Steamboat Round the Bend, it evokes a parallel with Ford’s story about an older man and a girl. Even those who despised the tradition, like Altman, were obliged to invoke it, as in the parodic reappearances of the main musical theme throughout The Long Goodbye.

But tradition is additive. As the New Hollywood wing of the Brats—Lucas, Spielberg, De Palma, Carpenter, and others—revived the genres of classic studio filmmaking, they created modern classics. The Godfather, Jaws, Star Wars, Carrie, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and others weren’t only updated versions of the gangster films, horror movies, thrillers, science-fiction sagas, and adventure tales that Hollywood had turned out for years. They formed a new canon for younger filmmakers. Accordingly, the next wave of the 1980s and 1990s referenced the studio tradition, but it also played off the New Hollywood. For “New New Hollywood” directors like Robert Zemeckis and James Cameron, their tradition included the breakthroughs of filmmakers only a few years older than themselves.

So today’s young filmmaker working in Hollywood faces a task. How to sustain and refresh this multifaceted tradition? One filmmaker who writes screenplays and occasionally directs them has found some lively solutions.

From the ’40s to the ’10s

The Trigger Effect (1996).

David Koepp was fourteen when he saw Star Wars and eighteen when he saw Raiders. By the time he was twenty-nine he was writing the screenplay for Jurassic Park. Later he would provide Spielberg with War of the Worlds (2005) and Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008). Across the same period he worked with De Palma (Carlito’s Way, 1993; Mission: Impossible, 1996; Snake Eyes, 1998), and Ron Howard (The Paper, 1994), as well as younger directors like Zemeckis (Death Becomes Her, 1992), Raimi (Spider-Man, 2002), and Fincher (Panic Room, 2002). The young man from Pewaukee, Wisconsin who grew up with the New Hollywood became central to the New New Hollywood, and what has come after.

He spent two years at UW–Madison, mostly working in the Theatre Department but also hopping among the many campus film societies. He spent two years after that at UCLA, enraptured by archival prints screened in legendary Melnitz Hall. The result was a wide-ranging taste for powerful narrative cinema. He came to admire 1970s and 1980s classics like Annie Hall, The Shining, and Tootsie. As a director, Koepp resembles Polanski in his efficient classical technique; his favorite movie is Rosemary’s Baby, and one inspiration for Apartment Zero (1988) and Secret Window was The Tenant. You can imagine Koepp directing a project like Frantic or The Ghost Writer.

Old Hollywood is no less important to Koepp. Among his favorites are Double Indemnity, Mildred Pierce, and Sorry, Wrong Number. In conversation he tosses off dozens of film references, from specifically recalled shots and scenes to one-liners pulled from classics, like the “But with a little sex” refrain from Sullivan’s Travels.

It’s not mere geek quotation-spotting, either. The classical influence shows up in the very architecture of his work. He creates ghost movies both comic and dramatic, gangster pictures, psychological thrillers, and spy sagas. The Paper revives the machine-gun gabfests of His Girl Friday, while Premium Rush gives us a sunny update of the noir plot centered on a man pursued through the city by both cops and crooks.

One of the greatest compliments I ever got (well, it seemed like a compliment to me, anyway) was when Mr. Spielberg told me I’d missed my era as a screenwriter–that I would have had a ball in the 40s.

Like his contemporary Soderbergh, Koepp sustains the American tradition of tight, crisp storytelling. He also thinks a lot about his craft, and he explains his ideas vividly. His interviews and commentary tracks offer us a vein of practical wisdom that repays mining. It was with that in mind that I visited him in his Manhattan office to dig a little deeper.

Humanizing the Gizmo

Today, the challenge is the tentpole, the big movie full of special effects. A tentpole picture needs what Koepp calls its Gizmo, its overriding premise, “the outlandish thing that makes the big movie possible.” The Gizmo in in Jurassic Park is preserved DNA; the Gizmo in Back to the Future is the flux capacitor. “The more outlandish the Gizmo, the harder it is to write everybody around it.” The problem is to counterbalance scale with intimacy. “You need to offset what’s ‘up there’ [Koepp raises his arm] with things that are ‘down here’ [he lowers it].” This involves, for one thing, humanizing the characters. A good example, I think, is what he did with Jurassic Park.

Crichton’s original novel has a lot going for it: two powerful premises (reviving dinosaurs and building a theme park around them), intriguing scientific speculation, and a solid adventure framework. But the characterizations are pallid, the scientific monologues clunky, and the succession of chases and narrow escapes too protracted.

The film is more tightly focused. In the novel, Dr. Grant is an older widower and has no romantic relation to Ellie; here they’re a couple. In the original, Grant enjoys children; in the film, he dislikes them. Accordingly, Koepp and Spielberg supply the traditional second plotline of classic Hollywood cinema. Alongside the dinosaur plot there’s an arc of personal growth, as Grant becomes a warmer father-figure and he and Ellie become short-term surrogate parents for Tim and Alexa.

Similarly, Crichton’s hard-nosed Hammond turns into a benevolent grandfather; in the film, his defensive attitude toward the park’s project collapses when his children are in danger. Even Ian Malcolm, mordantly played by Jeff Goldblum (stroking some of the most unpredictable line-readings in modern cinema), can be seen as the wiseacre uncle rather than the smug egomaniac of the novel.

Crichton’s tale of scientific overreach becomes a family adventure. Koepp’s consistent interest in the crises facing a family meshes nicely with the same aspect of Spielberg’s work, and it gives the film an appeal for a broad audience. In the original, Tim is a boy wonder, well-informed about dinosaurs and skilled at the computer. Koepp’s screenplay shares out these areas of expertise, making Lex the hacker and letting her save the day by rebooting the park’s defense system. There’s a model of courage and intelligence for everybody who sees the movie.

While giving Crichton’s novel a narrative drive centered on the surrogate family, Koepp also creates a more compressed plot. For one thing, he slices out the chunks of scientific explanation that riddle the novel. The main solution came, Koepp says, when Spielberg pointed out that modern theme parks have video presentations to orient the visitors. Koepp and Spielberg created a short narrated by “Mr. DNA,” in an echo of the middle-school educational short “Hemo the Magnificent.” The result provides an entertaining bit of exposition that condenses many scenes in the book. Why Mr. DNA has a southern accent, however, Koepp can’t recall.

Compression like this allows Koepp to lay the film out in a well-tuned structure. Most of his work fits the four-part model discussed by Kristin and me so often (as here). In Storytelling in the New Hollywood, she shows how Jurassic displays the familiar pattern of goals formulated (part one), recast (part two), blocked (part three), and resolved (part four). When I visited Koepp, he was laying out 4 x 6 cards for his screenplay for Brilliance, seen above. He remarked that the array fell into four parts, with a midpoint and an accelerating climax.

For a smaller-scale example of compression, consider a classic convention of heist movies: the planning session. In Mission: Impossible, Ethan Hunt reviews his plan for accessing the computer files at CIA headquarters. As he starts, the reactions of the two men he’s recruiting foreshadow what they’ll do during the break-in: the sinister calculation of Krieger (Jean Reno), in particular, is emphasized by De Palma’s direction. Ethan’s explanation of the security devices shifts to voice-over and we leave the train compartment to follow an ineffectual bureaucrat making his way into the secured room. (The room and the gadgets were wholly made up for the film; the Langley originals were far more drab and low-tech.)

Everything that will matter later, including the heat-sensitive floor and the drop of moisture that can set off the alarms, is laid out visually with Ethan’s explanation serving as exposition. Like the Mr. DNA short, this set-piece, extravagant in the De Palma mode, serves to specify how things in this story will work. Here, however, the task involves what Koepp calls “baiting the suspense hook. “ Each detail is a security obstacle that Hunt’s team will have to overcome.

The world is too big

Panic Room.

The overriding problem, Koepp says, is that the world is too big for a movie. There are too many story lines a plot might pursue; there are too many ways to structure a scene; there are too many places you might put the camera. You need to filter out nearly everything that might work in order to arrive at what’s necessary.

At the level of the whole film, Koepp prefers to lay down constraints. He likes “bottles,” plots that depend on severely limited time or space or both. The Paper ’s action takes 24 hours; Premium Rush’s action covers three. Stir of Echoes confines its action almost completely to a neighborhood, while Secret Window mostly takes place in a cabin and the area around it. Even those plots based on journeys, like The Trigger Effect and War of the Worlds, develop under the pressure of time.

Panic Room is the most extreme instance of Koepp’s urge for concentration. He wanted to have everything unfold in the house during a single night and show nothing that happened outside. (He even thought about eliminating nearly all dialogue, but gave that up as implausible: surely the home invaders would at least whisper.) As it worked out, the action in the house is bracketed by an opening scene and closing scene, both taking place outdoors, but now he thinks that these throw the confinement of the main section into even sharper relief. The result is a tour de force of interiority—not even flashbacks break us out of the immense gloom of the place—and in the tradition of chamber cinema it gives a vivid sense of the overall layout of the premises.

Panic Room, like Premium Rush, relies on crosscutting to shift us among the characters and compare points of view on the action. But another way to solve the world-is-too-big problem is to restrict us to what only one characters sees, hears, and knows. This is what Polanski does in Rosemary’s Baby, which derives so much of its rising tension from showing only what Rosemary experiences, never the plotting against her. Koepp followed the same strategy in War of the Worlds. Most Armageddon films offer a global panorama and a panoply of characters whose lives are intercut. But Koepp and Spielberg decided to show no destroyed monuments or worldwide panics, not even via TV broadcasts. Instead, we adhere again to the fate of one family, and we’re as much in the dark as Ray Ferrier and his kids are. Even when Ray’s teenage son runs off to join the military assault, we learn his fate only when Ray does.

Less stringent but no less significant is the way the comedy Ghost Town follows misanthropic dentist Bertram Pincus (Ricky Gervais). After a prologue showing the death of the exploitative exec played by Greg Kinnear, we stay pretty much with Pincus, who discovers that he can see all the ghosts haunting New York. Limiting us to what he knows enhances the mystery of why these spirits are hanging around and plaguing him.

Yet sticking to a character’s range of knowledge can create new problems. In Stir of Echoes, Koepp’s decision to stay with the experience of Tom Witzky (Kevin Bacon) meant that the film would give up one of the big attractions of any hypnosis scene—seeing, from the outside, how the patient behaves in the trance. Koepp was happy to avoid this cliché and followed Richard Matheson’s original novel by presenting what the trance felt like from Tom’s viewpoint.

The premise of Secret Window, laid down in Stephen King’s original story, obliged Koepp to stay closely tied to Mort Rainey’s range of knowledge. In his director’s commentary, Koepp points out that this constraint sacrifices some suspense, as during the scene when Mort (Johnny Depp) thinks someone else is sneaking around his cabin. We can know only what he sees, as when he glimpses a slightly moving shoulder in the bathroom mirror.

Having nothing to cut away to, Koepp says, didn’t allow him to build maximum tension. Still, the film does shift away from Mort occasionally, using a little crosscutting during phone conversations and at the climax. During the big revelation, Koepp switches viewpoint as Mort’s wife arrives at the cabin; but this seems necessary to make sure the audience realizes that the denouement is objective and not in Mort’s head.

Once you’ve organized your plot around a restrictive viewpoint, breaking it can be risky. About halfway through Snake Eyes, Koepp’s screenplay shifts our attachment from the slimeball cop Rick Santoro (Nicolas Cage) to his friend Kevin (Gary Sinese). We see Kevin covering up the assassination. In the manner of Vertigo, we’re let in on a scheme that the protagonist isn’t aware of. This runs the risk of dissipating the mystery that pulls the viewer through the plot. Sealing the deal, Snake Eyes then gives us a flashback to the assassination attempt. Not only does this sequence confirm Kevin’s complicity, it turns an earlier flashback, recounted by Kevin to Rick, into a lie. Although lying flashbacks have appeared in other films, Koepp recalls that the preview audience rejected this twist. The lying flashback stayed in the film because the plot’s second half depended on the early revelation of Kevin’s betrayal.

Because the world is too big, you need to ask how to narrow down options for each scene as well as the whole plot. Fiction writers speak of asking, “Whose scene is it?” and advise you to maintain attachment to that character throughout the scene. The same question comes up with cinema.

Say the husband is already in the kitchen when the wife comes in. If you follow the wife from the car, down the corridor, and into the kitchen, we’re with her; we’ll discover that hubby is there when she does. If instead we start by showing hubby taking a Dr. Pepper out of the refrigerator and turning as the wife comes in, it’s his scene. Note that this doesn’t involve any great degree of subjectivity; no POV shot or mental access is required. It’s just that our entry point into the scene comes via our attachment to one character rather than another.

Here’s a moment of such a directorial choice in Stir of Echoes. Maggie comes home to find her husband Tom, driven by demands from their domestic ghost, digging up the back yard. Koepp could have gotten a really nice depth composition by showing us a wide-angle shot of Tom and his son tearing up the yard, with Maggie emerging through the doorway in the background. That way, we would have known about the mess before she did.

Instead, Koepp reveals that Tom’s mind has gone off the rails by showing Maggie coming out onto the back porch and staring. We hear digging sounds. “Oh…kay…” she sighs.

She walks slowly across the yard, passing their son and eventually confronting Tom, who’s so absorbed he doesn’t hear her speak to him.

Once you’ve made a choice, though, other decisions follow. So Maggie provides our pathway into the scene, but how do we present that? Koepp asks on his commentary track:

What do you think? Is it better to do what I did here, which is pull back across the yard and slowly reveal the mess he’s made, or should I have cut to her point of view of the big messy yard right in the doorway? I went for lingering tension rather than the sudden cut to what she sees. You might have done it differently.

Sticking with a central character throughout a scene can have practical benefits too. Koepp points out that his choice for the Stir of Echoes shot was affected by the need to finish as the afternoon light was waning. Similarly, in the forthcoming Jack Ryan, Koepp includes an action scene showing an assault on a helicopter carrying the hero. Koepp’s script keeps us inside the chopper as a door is blown off and Ryan is pinned under it. Rather than including long shots of the attack, it was easier and less costly to composite in partial CGI effects as bits of action glimpsed in the background, all seen from within the chopper.

Saving it, scaling it, buttoning it

Ghost Town.

Because the world is too big, you can put the camera anywhere. Why here rather than there?

Standard practice is to handle the scene with coverage: You film one master shot playing through the entire scene, then you take singles, two-shots, over-the-shoulders, and so on. Actors may speak their lines a dozen times for different camera setups, and the editor always has some shot to cut to. Alternatively, the director may speed up coverage by shooting with many cameras at once. Some of the dialogues in Gladiator were filmed by as many as seven cameras. “I was thinking,” said the cinematographer, “somebody has to be getting something good.”

Koepp opposes both mechanical and shotgun coverage. Whenever he can, he seizes on a chance to handle several pages of dialogue in a single take (a “one-er”). “There’s a great feeling when you find the master and can let it run.” Sustained shots work especially well in comedy because they allow the actors to get into a smooth verbal rhythm. The hilariously cramped three-shot in Ghost Town (shown above) could play out in a one-er because Koepp and Kamps meticulously prepared its rapid-fire dialogue exchange.

When cutting is necessary, Koepp favors building scenes through subtle gradations of scale, saving certain framings for key moments. He walked me through a striking example, a five-minute scene in Panic Room.

Meg Altman and her daughter Sarah have been besieged by home invaders. Meg has managed to flee from their sealed safety room, but Sarah is trapped there and is slipping into a diabetic coma while the two attackers hold her captive. Now two policemen, summoned by Meg’s husband, come calling. The criminals are watching what’s happening on the CC monitor. Meg must drive the cops away without arousing suspicion, or the invaders will let Sarah die.

Koepp’s scene weaves two strands of suspense, the peril of the girl and Meg’s tactics of dealing with the cops. One cop is ready to leave her alone, but another is solicitous. Meg offers various excuses for why her husband called them—she was drunk, she wanted sex—but the concerned cop persists. The scene develops through good old shot/ reverse-shot analytical editing, with variations in scale serving to emphasize certain lines and facial reactions.

At the climax, the concerned officer says that if there’s anything she wants to tell them but cannot say explicitly, she could blink her eyes as a signal. When he asks this, Fincher cuts in to the tightest shot yet on him. The next shot of Meg reveals her decision. She refuses to blink.

Fincher saved his big shot of the cop for the scene’s high point. The cop’s line of dialogue motivates the next shot, one that keeps the audience in suspense about how Meg will respond. What I love about this shot is that everybody in the theatre is watching the same thing: her eyes. Will she blink?

Building up a scene, then, involves holding something back and saving it for when it will be more powerful. An extreme case occurs in Rosemary’s Baby. I asked Koepp about a scene that had long puzzled me. Rosemary and Guy have joined their slightly dotty older neighbors, the Castevets, for drinks and dinner. Having poured them all some sherry, Castavet settles into a chair far from the sofa area, where the other three are seated.

Mr. Castevet continues to talk with them from this chair, still framed in a strikingly distant shot.

Koepp agreed that virtually no director today would film the old man from so far back. Can’t you just see the tight close-up that would hint at something sinister in his demeanor?

We found the justification in the next scene, the dinner. This is filmed with one of those arcing tracks so common today when people gather at a table, but here it has a purpose. The shot’s opening gives us another instance of the Castevets’ social backwardness, as Rosemary saws away at her steak. (You’d think people in league with Satan could afford a better cut of meat.)

Mr. Castevet proceeds to denounce organized religion and to flatter Guy’s stage performance in Luther. As the camera moves on, the fulcrum of the image becomes the old man, now seen head-on from a nearer position.

“He was saving it,” said Koepp. “He was making us wait to see this guy more closely—and even here, he’s postponing a big close-up.”

Yet having given with one hand, Polanski takes away with the other. Next Rosemary is doing the dishes with Mrs. Castevet while the men share cigarettes in the parlor. Because we’re restricted to Rosemary’s range of knowledge, we see what she sees: nothing but wisps of smoke in the doorway.

We’ll later realize that this offscreen conversation between Roman and Guy seals the deal over Rosemary’s first-born.

Empty doorways form a motif in the film (the major instance has been much commented on), and they too point up Polanski’s stinginess—or rather, his economy. He doles his effects out piece by piece, and the result is a mix of mystery and tension that will pay off gradually. Koepp likewise exploits the sustained empty frame, most notably at the end of Ghost Town.

Building up scenes in this way encourages the director to give each shot a coherence and a point. Koepp recalls De Palma’s advice: “For every shot, ask: What value does it yield?” Spielberg comes to the set with clear ideas about the shots he wants, and when scouting or rehearsing he’s trying to assure that the set design, the lighting, and the blocking will let him make them. As Koepp puts it, Spielberg is saying: “This is my shot. If I can’t do X, I don’t have a shot.”

Compared to the swirling choppiness on display in much modern cinema–say, at the moment, Leterrier’s Now You See Me–Koepp’s style is sober and concentrated. For him, the director should strive to turn a shot into a cinematic statement that develops from beginning to end. The slow track rightward in Stir of Echoes has its own little arc, following Maggie leaving the porch, moving past their son, concluding on Tom as she speaks to him and he suddenly turns to her (at the cut).

Accordingly a shot can end with a little bump, a “button” that’s the logical culmination of the action. Something as simple as Rosemary turning her head to look sidewise is a soft bump, impelling the POV shot of the doorway. Something more forceful comes in Stir of Echoes, when the people at the party chatter about hypnosis and the camera slowly coasts in on Tom, gradually eliminating everybody else until in close-up he says cockily, “Do me.”

Shooting all the conversational snippets among various characters would have required lots of coverage, and it was cleaner to keep them offscreen as the camera drew in on Tom. With the suspense raised by the track-in (a move suggested by De Palma), Koepp could treat Tom’s line as a dramatic turning point and the payoff for the shot.

In a comic register, the button can yield a character-based gag. Bertram Pincus is warming to the Egyptologist Gwen; he’s even bought a new shirt to impress her. They discuss how his knowledge of abcessed teeth can help her research into the death of a Pharaoh. A series of gags involves Pincus’ discomfiture around the mummy, with Gwen making him touch and smell it. The two-shot, Koepp says, is still the heart of dialogue cinema, especially in comedy.

Bertram offers Gwen a “sugar-free treat” and shyly turns away. The gesture reveals that he’s forgotten to take the price tag off his shirt.

This buttons up the shot with an image that reveals the characters’ attitudes. Pincus’s error undercuts his self-important explanation of the pharoah’s oral hygiene. Yet it’s a little endearing; he was in such a hurry to make a good impression he forgot to pull the tag. At the same, having Gwen see the tag shows her sudden awareness that Bertram’s offensiveness masks his social awkwardness. As Koepp puts it: “He bought a new shirt for their meeting, she realizes it, and she finds it sweet.” She’s starting to like him, as is suggested when she turns and matches his posture.

Koepp gives the whole scene its button by cutting back to a long shot as Pincus murmurs, “Surprisingly delightful.” Is he referring to his candy, or his growing enjoyment of Gwen’s company? Both, probably: He’s becoming more human.

Like the Movie Brats and the New New Hollywood filmmakers, Koepp is inspired by other films. And as with them, his usage isn’t derivative in a narrow sense. He treats a genre convention, a situation, an earlier Gizmo, or a fondly-remembered shot as a prod to come up with something new. Borrowing from other films isn’t unoriginal; in mainstream filmmaking, originality usually means revising tradition in fresh, personal ways.

There’s a lot more to be learned about screenwriting and directing from the work of David Koepp. He told me much I can’t squeeze in here, about the Manhattan logistics of shooting Premium Rush and about the newsroom ethnography behind The Paper, written with his brother Stephen. What I can say is this: He really should write a book about his craft. I expect that it would be as good-natured as his lopsided grin and quick wit. It would illuminate for us the range of the creative choices available in the New Hollywood, the New New Hollywood, and the Newest Hollywood.

Thanks to David for giving me so much of his time. We initially came into contact when he wrote to me after my blog post on Premium Rush, which now contains a P.S. extracted from his email. We had never met, and I’m glad we finally caught up with each other.

I’ve supplemented my conversation with David with ideas drawn from his DVD commentaries for Stir of Echoes, Secret Window, and Ghost Town. Soderbergh provides intriguing observations on the commentary track for Apartment Zero. I’ve also found useful comments in these published interviews: “David Koepp: Sincerity,” in Patrick McGilligan, ed., Backstory 5: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1990s (University of California Press, 2010), 71-89; Joshua Klein “Writer’s Block, [1999],” at The Onion A.V. Club; Steve Biodrowski, “Stir of Echoes: David Koepp Interviewed [2000]” at Mania; Josh Horowitz, “The Inner View–David Koepp [2004]” at A Site Called Fred; “Interview: David Koepp (War of the Worlds)[2005]” at Chud.com; Ian Freer, “David Koepp on War of the Worlds [2006],” at Empire Online; “Peter N. Chumo III, “Watch the Skies: David Koepp on War of the Worlds,” Creative Screenwriting 12, 3 (May/June 2005), 50-55; E. A. Puck, “So What Do You Do, David Koepp? [2007]” at Mediabistro; Nell Alk, “David Koepp, John Kamps Talk Premium Rush, Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s Fearlessness and Pedestrian ‘Scum’ [2012]” at Movieline; and Fred Topel, “Bike-O-Vision: David Koepp on Premium Rush and Jack Ryan [2012]” at Crave Online.

Vincent Sherman discusses screenplay switching in People Will Talk, ed. John Kobal (Knopf, 1986), 549-550. My quotation from Gladiator‘s DP comes from The Way Hollywood Tells It, p. 159. For more on David Fincher’s way with characters’ eyes, see this entry on The Social Network.

Oscar fever up close

Kristin here:

Most years when I’m at home, I join in our departmental Oscar party, where grad student and faculty get together to watch the broadcast and match wits at predicting the winners. It beats the grimness of sitting home watching the show.

But this year, being a relatively new staff member on TheOneRing.net, I decided to attend their celebration, “The One Expected Party,” for The Hobbit. TORn put on three Oscar parties for The Lord of the Rings, in 2002, 2003, and 2004. Those parties became the stuff of legend within the fandom, having rapidly sold out each time. The nominees and winners from the trilogy dropped by the TORn party each year (fueling the next year’s ticket sales). I wrote about the Oscar parties as part of my coverage of TORn in my book, The Frodo Franchise, but I had never been to any of them.

In planning my trip, I quickly discovered that there are a lot of other activities around the run-up to the Oscar ceremony. I knew, of course, that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences offers screenings of the nominated films to their members and to anyone else lucky enough to get a ticket. But our old friend Chen Mei, who works for the Academy library, told me about panel sessions featuring the nominees in various categories and kindly obtained tickets for me to attend two of them.

Obviously the nominees take these events seriously. For both of those I attended, with one exception all the directors of the nominated films showed up to answer questions from a moderator. Obviously they couldn’t hope to influence the members’ votes, since the ballots had already been turned in. They generously gave time to offer insights into their work to audiences who clearly were knowledgeable about filmmaking.

“Oscar Celebrates Animated Features”

This panel discussion took place on the evening of February 21, the day I arrived in Los Angeles. When I got to the Academy’s Samuel Goldwyn Theatre, more than an hour before the 7:30 event, there was already a long line of ticket-holders hoping to get good seats. I gathered from conversations with people around me in line that tickets are getting harder to obtain each year.

Most of the best seats were roped off, reserved for Academy members and the guests of honor. I got an unreserved one in the second row but way over on the side. It actually gave a pretty good view of the stage. Unfortunately photos are strictly forbidden inside the Samuel Goldwyn Theatre, so I have none to show you.

Most of the best seats were roped off, reserved for Academy members and the guests of honor. I got an unreserved one in the second row but way over on the side. It actually gave a pretty good view of the stage. Unfortunately photos are strictly forbidden inside the Samuel Goldwyn Theatre, so I have none to show you.

Almost all of the directors of all five nominated features were there: Peter Lord for The Pirates! Band of Misfits; Sam Fell and Chris Butler for ParaNorman; Mark Andrews for Brave (co-director Brenda Chapman being unable to attend); Rich Moore for Wreck-It Ralph; and Tim Burton for Frankenweenie. (All but Burton stuck around to pose for the press; left to right, Moore, Butler, Andrews, Lord, and Fell.)

This line-up of talent should have made for an enlightening evening. Unfortunately the AMPAS had chosen as MC a comic actor, Rob Riggle (Talladega Nights, The Hangover) who turned out to know less about animation than most of the people in the audience did. He was obviously more concerned with being entertaining than with drawing out any solid information about the films. He kept asking the guests what inspired them to make their films, while very little got said about the films’ innovative techniques and the challenges the filmmakers faced–in short, about the films. Despite this obstacle, the guests managed to say some interesting things. There was obviously no audio recording either, so I frantically took notes.

One motif that cropped up several times was the fact that this year’s nominees included three stop-motion films. But as some of the animators emphasized, despite their love for the slow, frame-by-frame manipulation of puppets and objects, they do mix in new technologies. Fell described himself and fellow director Butler as “Luddites who’ve embraced the loom.” For example, although ParaNorman‘s young witch Aggie was animated as a puppet, her dress was an added digital effect. As Butler said, although they basically work with puppets, they will use whatever animation technique will look best on the screen. (Earlier this month, I discussed the use of color laser printing that made the wide variety of character expressions possible.)

Lord twice mentioned the convivial atmosphere created at Aardman’s Bristol studio, where people who love puppet animation have come together as a team. They avoid computer animation whenever possible, preferring “the lovely, amazing toys in the world, stuff the animators work with at Aardman.”

Fell and Butler described their influences as the horror films they saw during their childhoods in England. Butler had watched Night of the Living Dead at age 6, and Fell referred to “video nasties,” as they are labeled in England, very violent films that were banned or at least difficult to see. The age of VHS made such films as Driller Killer available, as Fell pointed out, though Butler hastened to point out that that particular film had not influenced ParaNorman.

Moore, who had directed episodes of both The Simpsons and Futurama, made Wreck-It Ralph as his first feature. Asked the difference between episodic animated TV and features, he responded that in features, characters move through an arc that changes their situation by the end. In TV, the characters start at square one, play out an action, and end up on square one by the end, ready to do the same thing the following week.

Burton was asked the difference between the original Frankenweenie short and the feature. Because the feature was animated, he considers it “a more pure version” of the original live-action short. In working on the style of the set designs for the feature, he went back not to the short itself, but to the drawings he had originally done for it. He also admitted that during the early days when he was had a job at Disney drawing cels for The Fox and the Hound (1981), his drawings of the fox looked “like road kill.”

Interlude: Ground Zero, the Dolby Theatre

The grand theater on Hollywood Boulevard where the awards ceremony takes place may now be named the Dolby, but it remains the Kodak Theatre on Google Maps and in the minds of the many who still call it that. Then again, I heard people at one of the Academy panels refer to “Grauman’s Chinese Theatre,” despite that fact that the Mann’s chain acquired it decades ago and it has again changed hands.

I was staying in the Hilton Garden Inn, on Highland Avenue a few blocks north of where it intersects Hollywood Boulevard at the corner dominated by the Dolby Theatre’s huge complex. Having a free morning on Friday, I wandered down, looking to take some pictures of the Oscar preparations.

The Dolby Theatre is also a shopping mall. It is surely the only mall in the world modeled on the work of D. W. Griffith, specifically his Babylon sets from Intolerance. Giant white elephants on pillars loom over tourists. (Top, and at left, a view looking toward the back of the complex from the north.)

Naturally the block of Hollywood Boulevard in front of the theatre was closed to traffic. Online one could find a complicated schedule of road and even sidewalk closings that went on for as much as a week before the day of the ceremony. Fortunately on this day the sidewalks were still open, so I could join the tourists watching the preparations and snapping photos. The bleachers had been installed, as had the famous red carpet. A larger nearby parking lot was filled with trailers sprouting satellite dishes. The infrastructure for this event is vast, as one would imagine. It’s also far from glamorous.

“Oscar Celebrates Foreign Language Films”

On Saturday morning I got to the Samuel Goldwyn Theatre earlier, about 8:30 am for a 10:00 event. This time I was among the first twenty-five or so in line and got an excellent seat in the third row opposite the podium. Mark Johnson, who until recently ran the foreign-language category, was the MC. David and I have known Mark for years, since the early 1970s, when we were all in graduate school in film studies at the University of Iowa. Between his film education and extensive work in the industry (including producing the Chronicles of Narnia films, Rain Man, Galaxy Quest, A Little Princess, and Breaking Bad), Mark was an excellent choice to host the event, as he had done several times in past years.

All the directors showed up: Michael Haneke for Amour; Kim Nguyen for War Witch; Pablo Larraín for No, Nikolaj Arcel for A Royal Affair; and Joachim Rønning and Espen Sandberg for Kon-Tiki. (I discussed No and A Royal Affair in a report from the Vancouver International Film Festival last year.)

As each director came onstage, Mark graciously asked him to acknowledge any members of his filmmaking team who were in the audience. These included three of the four producers of Amour, Stefan Arndt, Veit Heiduschka, and Michael Katz. When Mark asked where the fourth producer, Margaret Menegoz was, Haneke got off the first zingy of the evening, saying that she would be arriving that evening: “She was picking up the Césars.” (On Friday, Amour won five, for best picture, director, original screenplay, actor, and actress).

Mark’s excellent questions solicited much information. I can’t summarize it all, but here are some highlights, film by film.

Arcel emphasized how difficult it was to finance A Royal Affair, given that it was a big, expensive costume picture: “It’s a risk in Denmark, where we have more the kitchen drama.” Although Zentropa Productions made the film, there was considerable investment from other European countries. One of the film’s stars, Mikkel Boe Følsgaard, was an acting student when he was cast as the eccentric Danish king, and he won the best actor prize at Berlin. Arcel revealed that after making A Royal Affair, Følsgaard went back to resume his acting-school education, where the next unit was on film acting. A Royal Affair was the only nominee shot on 35mm. Rather than following the European art-cinema tradition, he was influenced by his favorite Hollywood films, like Gone with the Wind and Lawrence of Arabia.

No was the third film in a trilogy about the Pinochet years in Chile, the earlier ones being Tony Manero (2008) and Post Mortem (2010). Mark asked Larraín if he had initially planned a trilogy. He said no, “I would say it is mostly the press who have named this a trilogy.” On the other hand, he thinks the term makes sense when applied to these films, and he has no objection. He commented that the film depicts how the same tools of propaganda Pinochet used on the people were turned against him. Rather than staging a violent takeover, “They put him out with the tools of beauty.” His filmmaking team had intended the lead role for Gael García Bernal from the start, despite his being a Mexican actor. The other actors had been with Larraín on previous films and all are well-known in Chile.

Larraín also talked about the four 1983 video cameras that were used to simulate older footage, each of which produced footage with a slightly different look. The team was worried about the various shots not cutting together smoothly with each other and with the archival footage that was integrated into the film. During editing, however, they began to forget which footage was new and which was archival and realized that they were succeeding. “What we shot became documentary, and the documentary shots became fiction.”

Nguyen talked about casting War Witch. Seventy-five per cent of the cast were non-actors. Rachel Mwanza, who played a young African girl forced to serve as a child soldier, was recommended by some documentarists who had filmed her as part of a group of homeless street kids; she had been abandoned by her parents at age 6. The film was shot with an Alexa. Tires constantly burning in the streets of Kinshasa created a haze that the filmmakers used as a filter for the natural light. Nguyen read many autobiographies of child soldiers as models for the voiceover narration in the film.

Rønning and Sandberg were inspired by the story of Thor Heyerdahl’s raft voyage from South America to Polynesia in 1947. Heyerdahl was a national legend, and his documentary record of the trip, Kon-Tiki (1950), won the only Oscar so far awarded a Norwegian film. Heyerdahl’s life was extremely well-documented in his diaries, which guided the scriptwriting. The filmmakers were lucky enough to gain access to a replica of the original raft, which had been made by Heyerdahl’s grandson to repeat the original voyage. The shooting at sea lasted for a month. In addition, however, there were over 500 special-effects shots–making Kon-Tiki, like A Royal Affair, a big-budget, Hollywood-style film. The directors said that with so much drama on TV, they wanted to create an epic that cried out to be seen on a big theatre screen. The effects were mainly for creating sharks and other creatures, extending sets, and occasionally erasing boats or shorelines in backgrounds.

Mark pointed out to Haneke that a lot of Americans know Amour is good but avoid seeing it because they think it’s too grim. Haneke blamed the American media for giving that impression of the film, saying that he considers it to be about love rather than death. But with a smile he also admitted, “I’m afraid it’s partly my fault.” He has gotten a reputation “for inflicting pain on audiences.” From the start he had planned the film around Jean-Louis Trintignant and would not have made it had he refused the part. Emmanuelle Riva, however, he found through the conventional casting process of auditions.

Mark mentioned the fact that the film juxtaposes wide views with close-ups, with few camera distances in between. Some scenes play out in a single long shot. Haneke responded “I want to give my audience time to reflect […] I try to manipulate the audience as little as possible.” Mark pointed out that in spite of this, the spectator always knows where to look. Haneke replied: “It’s all a question of craft.” (This drew applause from the audience.) The apartment in the film was a set, a choice made mainly because the older actors could not work long hours in difficult circumstances. The views seen through the windows were added with computer effects. Haneke dislikes non-diegetic music in films, and so he writes characters who would naturally be playing or listening to music within the story. In the case of Amour, he chose all the classical music before writing the script.

“The Art of Production Design”

The AMPAS isn’t the only organization hosting events around the presence of so many Oscar nominees being in Los Angeles. Straight from the foreign-film event I went with our friend Jonathan Kuntz, who teaches film and television at Los Angeles City College and the University of California at Los Angeles, to the Egyptian Theatre on Hollywood Boulevard. There the Art Directors Guild, the Set Decorators Society of America, and the American Cinematheque were presenting a similar panel discussion on “The Art of Production Design.” Nearly all the nominees were present (with production designer listed first and set  decorator(s) second): Sarah Greenwood and Katie Spencer for Anna Karenina; Dan Hennah and set decorators Ra Vincent and Simon Bright for The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey; Eve Stewart and Anna Lynch-Robinson for Les Misérables; David Gropman and Anna Pinnock for Life of Pi (at right); and Rick Carter for Lincoln (set decorator Jim Erickson couldn’t attend). The co-moderators were Thomas A. Walsh, Production Designer and Co-Chair ADG Film Society with Academy Governor Rosemary Brandenburg, SDSA.

decorator(s) second): Sarah Greenwood and Katie Spencer for Anna Karenina; Dan Hennah and set decorators Ra Vincent and Simon Bright for The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey; Eve Stewart and Anna Lynch-Robinson for Les Misérables; David Gropman and Anna Pinnock for Life of Pi (at right); and Rick Carter for Lincoln (set decorator Jim Erickson couldn’t attend). The co-moderators were Thomas A. Walsh, Production Designer and Co-Chair ADG Film Society with Academy Governor Rosemary Brandenburg, SDSA.

Greenwood stressed how little time there had been to prepare the sets for Anna Karenina. The production at first was intended to be a conventional version, and location-scouting was done in Russia. The team decided to shoot in London, but there was no unifying conception until twelve weeks before principal photography director Joe Wright decided to stage the action in a set representing a theatre. There ended up being twelve days to actually construct the set, with the designers marking the sets in chalk on the floor and starting to build before there were drawings of them. She describes the theatre set as “rich but minimalist,” since the approach was to remove as many items as possible.

Hennah answered a question from the audience concerning where conceptual design, done for The Hobbit by illustrators John Howe and Alan Lee, ends and production design begins. He responded that conceptual design involves creating the environments as a whole, as if they were real places. “The production design kicks in in terms of what takes place in the parts of that set.” The sets were drawn digitally and then built as 3D models that went to the pre-viz department. Howe and Lee worked in at Weta Digital rather than in the art department, as did an assistant art director. Vincent and Bright both consulted on the color grading, among other roles.

Hennah spoke of the design of the huge Goblin Town set. He conceived it as having been built within a great diagonal rift inside the mountain caused by an earthquake. The Goblins being thieves, they constructed the buildings and bridges out of random stolen items like carts. The layout of the Dwarves kingdom within the Lonely Mountain derived from the idea that the space expanded randomly as the workers removed stone to follow veins of gold.

According to Stewart, the filmmakers did not try to make Les Misérables a faithful reproduction of the stage play. They wanted to do what the stage version couldn’t: “You can’t see big wides and you can’t see up people’s nostrils.” Hence the film utilized sweeping cityscapes with huge buildings and crowds, while the musical numbers are filmed in relentless close-ups. Tom Hooper likes to “make things up on the day,” so Stewart had to make the sets bigger than usual, since she couldn’t plan ahead for what he might improvise during filming.

Given how much of Life of Pi was shot in tanks, what did the designers have to do? Gropman explained that they designed the interior of the Indian house where the early part of the story is set, with the interiors being constructed in Montreal and the exteriors shot in India. The apartment in the frame story had to be simple and bland, so that it would not reflect the character at all. Since the film was not shot in continuity, a big challenge was keeping track of the deterioration of the lifeboat, which becomes more worn and damaged.

Given how much of Life of Pi was shot in tanks, what did the designers have to do? Gropman explained that they designed the interior of the Indian house where the early part of the story is set, with the interiors being constructed in Montreal and the exteriors shot in India. The apartment in the frame story had to be simple and bland, so that it would not reflect the character at all. Since the film was not shot in continuity, a big challenge was keeping track of the deterioration of the lifeboat, which becomes more worn and damaged.

Gropman asked artist Haan Lee, director Ang Lee’s son, to design the raft that Pi builds, and he came up with the idea of the raft as a triangle. The island was based on a single huge banyan tree in southern Taiwan, which was filmed for a day and then built in the studio.

Carter described having spent part of a day in the White House in preparation for Lincoln, including being left alone in the evening in the Lincoln bedroom. He graciously emphasized the importance of the set decoration, by the absent Erickson, as the main aspect of the settings that makes an impression on the audience. Virtually every day during the president’s last year of life was heavily documented, and research informed the set dressings. The designers also spent much time in Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the Confederacy, which Carter considered a city almost as much influenced by Lincoln as was Springfield, Illinois.

A member of the audience asked what effect 3D had had on the designers’ work. The two designers of 3D films gave similar answers. Gropman remarked, “There’s nothing you do where you’re not thinking about foreground, middle ground, and background. […] We’re creating the environment primarily for the actors.” Hennah’s response was, “It doesn’t change anything in terms of how you approach it. […] It’s about giving a feeling of depth and a feeling of separation, which you would do in the real world anyway.” In other words, 2D films have always had plenty of depth cues.

Afterward Jonathan introduced me to Rick Carter, a long-time friend with whom he had gone to school (Jonathan on the left, Rick on the right). He turned out to be the one from the group who won the Oscar the next evening.

The Hobbit, win or lose

TheOneRing.net’s celebration of The Hobbit‘s three nominations (production design, makeup and hairstyling, and visual effects) began on Friday night with an art show. I was one of many volunteers helping out with setting up that and the Sunday night party, so I ventured into the labyrinth of old warehouses east of downtown, an area now established as an arts district.

The show drew some major exhibitors, including veteran Tolkien illustrator Tim Kirk, seen above posing with his most famous paintings. I was also delighted to meet some fellow TORn staff members whom I had previously only known from the group email messages we exchange and from their postings on the site. They’re an enthusiastic group who all work on a strictly volunteer basis.

The big event was on Sunday at the Hollywood American Legion hall (at bottom, the entrance, with a representation of the Arkenstone above the door and a life-sized Gollum statue lurking inside to provide a photo op). I helped out with the setup that morning, hanging signs and folding a great many “One Expected Party” T-shirts to be sold in the “Rivendell” room (aka the shop).

The main auditorium, dubbed “The Hall of the Elven-King” for the occasion, was where most of the celebrants gathered to watch the Oscars on a vast TV screen. If they turned around, they would notice that a full sized cave troll from The Fellowship of the Ring was watching along with them:

I managed to watch the first half of the show but then was slotted to help sell T-shirts and CDs by the band that would be playing after the Oscar show ended: Billy Boyd’s “Beecake.” I was there long enough to sit through two of the categories for which The Hobbit was nominated and to be nearly deafened by the cheers–and then groans of disappointment. The fans reassure each other that as with The Lord of the Rings, the third part will scoop up Oscars serving to reward the whole trilogy.

Being in “Rivendell” selling stuff, I missed the second half of the show, but I gather that was not much of a loss. The Oscar fever being exhibited elsewhere in the building and around town turned out to be more interesting than the ceremony itself.

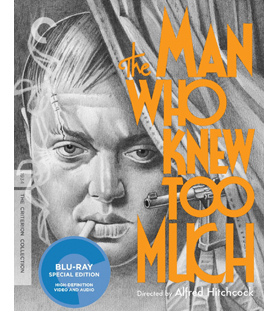

Sir Alfred simply must have his set pieces: THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO MUCH (1934)

The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934).

DB here:

Hitchcock made six remarkable thrillers from 1934 through 1938, and I have long believed that the first one was the best. I think very well of Sabotage, and both The Lady Vanishes and The 39 Steps are strong contenders. But for me, The Man Who Knew Too Much has got damn near everything going for it.

I came to it a little late. It wasn’t the first Hitchcock I wrote about; that was Notorious, in a 1969 piece that nakedly reveals the limitations of a college senior’s knowledge. Nor was it the first Hitchcock I saw; that was Vertigo, when I was about ten. Inauspiciously for me, when Vertigo was revived for national television broadcast in 1972, I was flying to a job interview in Madison, Wisconsin.

I got that job, though, and soon The Man Who Knew Too Much became very important for me. Seeing it at a film society screening, I was bowled over. Then I discovered that it was available for purchase in a cheap 16mm print. I bought a print and began teaching the film as a model of narrative construction. It worked its way into the first edition of Film Art, in 1979 and hung around there for several editions.

That sample analysis has been available as a pdf on our site, but check it out at the Criterion site, where it’s enhanced with nice frame enlargements and a major extract. The essay makes my case for the movie as an extremely well-constructed piece in the classical storytelling tradition.

So I was the ideal consumer for a spruced-up DVD/ Blu-ray release, and as usual Criterion doesn’t disappoint. It’s a handsome version, with some fine supplements. We get two rare interviews with Sir Alfred from CBS’s arts program Camera Three (featuring Pia Lindstrom and William K. Everson) and a perceptive discussion with Guillermo del Toro, who makes a vigorous case for the film. So does Philip Kemp in his commentary, which is strong on production background. Kemp offers valuable information on script versions and on Hitchcock’s niche in the English industry. The accompanying booklet includes a lively appreciation by The Self-Styled Siren, aka Farran Smith Nehme.

So I was the ideal consumer for a spruced-up DVD/ Blu-ray release, and as usual Criterion doesn’t disappoint. It’s a handsome version, with some fine supplements. We get two rare interviews with Sir Alfred from CBS’s arts program Camera Three (featuring Pia Lindstrom and William K. Everson) and a perceptive discussion with Guillermo del Toro, who makes a vigorous case for the film. So does Philip Kemp in his commentary, which is strong on production background. Kemp offers valuable information on script versions and on Hitchcock’s niche in the English industry. The accompanying booklet includes a lively appreciation by The Self-Styled Siren, aka Farran Smith Nehme.

Interest in Hitchcock seems to be the one constant in the whirligig of tastes in film culture. He is a mainstay of home video and cable television; apparently the films can be re-released in perpetuity. Professors love to teach his films. The techniques are obvious and vivid, and the films offer a manageable complexity that encourages interpretation. Class, gender, power, the law—whatever your favorite themes, they’re all on the surface, yet enticingly ambivalent. Not to mention how much fun these movies are to watch. I’ve always enjoyed introducing “lesser Hitchcock” like Stage Fright and Dial M for Murder and then watching the audience fall under their spell.

Critics navigate by Hitchcock as a fixed pole star. Reviewers compare every new thriller to the classics of The Master of Suspense. Just look at what people write about Soderbergh’s Side Effects. And for those who promoted the auteur approach to Hollywood cinema, Hitchcock was a beachhead. Who could doubt that this man turned out personal projects within the impersonal machine known as Hollywood? And if he could do it, why not Ford, Hawks, Sternberg, Ray, and all the rest? Hitchcock nudged skeptics down the slippery slope toward auteurism.

Even if Hitchcock isn’t to your taste, you can’t avoid his influence. That became obvious around the 1970s, when directors began borrowing from him more or less overtly: Spielberg’s Vertigo track-and-zoom in Jaws (now itself a convention), De Palma’s homages/pastiches, Polanski’s use of point-of-view in Repulsion and Rosemary’s Baby, the endless Psycho sequels and the van Sant remake, and the rest. But Hitch was no less influential in his own day; I’d argue that filmmakers of the 1940s had to raise their game if they wanted to meet the challenge of Rebecca, Foreign Correspondent, Suspicion, Shadow of a Doubt, Spellbound, and Notorious. Billy Wilder told a reporter that Double Indemnity was his effort to “out-Hitch Hitch.”

What was so special? Obviously, the throwaway humor—sometimes airy, sometimes slapstick, sometimes sardonic. And obviously a gift for switching situations around, playing them against cliché, setting us up for a jolt. But I think there’s something else afoot. Part of the Master’s repute rests on virtuosity of film technique. Hitchcock makes movie movies, even when, like Rope or Dial M, they seem “theatrical.” And this movieness is best seen, I think, by considering a term that always comes up with Lord Alfred: the set piece.

Maintaining a tradition

Hitchcock held onto the flamboyant expressive devices of silent and early sound cinema far longer than any other director. For decades he kept alive techniques that many directors thought were old hat: abrupt cuts to details of gestures and objects; blurry point-of-view images to suggest distraught or befuddled states of mind (as above); very brief insert shots to accentuate violence. Compare Battleship Potemkin with Foreign Correspondent’s assassination scene.

Hitchcock built entire films around classic silent techniques. The Kuleshov effect governs Rear Window; the German “entfesselte” or “unchained” camera dominates Rope and Under Capricorn. Rope and Dial M revive the aesthetics of the German kammerspielfilm, or “chamber play.” The Germanic look was alive and well in the spiderweb shadow-work of Suspicion, while both French Impressionism and German Expressionism inform the dream sequences of Spellbound and Vertigo. He also preserved the “creative use of sound” that was the hallmark of directors like Clair and Milestone. While others had pretty much given up the expressionistic use of music and effects, Hitchcock was always ready to draw on them. The hallucinatory Merry Widow Waltz haunts Shadow of a Doubt, while Hitchcock’s penchant for giving us two pieces of information simultaneously, one in the image and another on the soundtrack, let him design scenes visually and push a lot of dialogue offscreen.

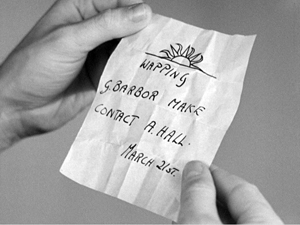

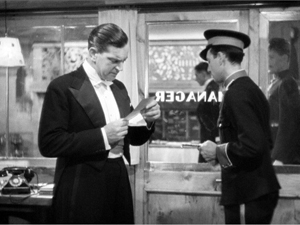

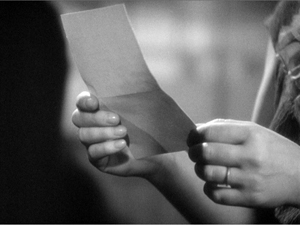

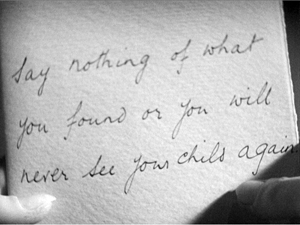

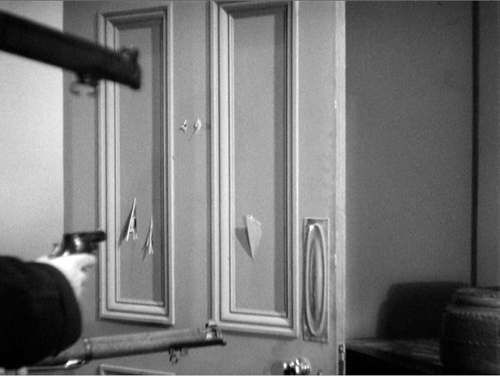

This flexibility of technique modulates from scene to scene. In The Man Who Knew Too Much, note-reading is presented in three ways, in rapid succession. First, Bob finds Louis’ note in the hairbrush.

Soon Bob gets a message from the front desk. What does it say? Hitchcock hides that by, for once, not supplying subjective point of view.

Only when the note is passed to Jill do we get to see it, but with a twist. Nobody but Hitchcock would add an extra shot that cuts to the note in her hand without revealing what it says.

That extra shot is what Eisenstein called a primer; as with dynamite, you need a little charge to trigger the blast.

We often forget that classic silent directors used their pictorial techniques for suspense. Lang’s Mabuse films and Spione furnish plenty of instances, but so do the Soviet montage films. The scene in which the police wait for the worker to return to his wife in The End of St. Petersburg now looks like pure Hitchcock, and of course the Odessa Steps sequence was the Psycho shower of its day. So it isn’t surprising that Hitchcock would turn his silent-film virtuosity toward creating scenes of high tension and threatened violence. Nor is it surprising that his skills would crystallize in “set pieces.”

Everybody talks about Hitchcock’s fondness for set pieces. It’s part of his brand. We have the Statue of Liberty climax in Saboteur, the milk carried up the staircase in Suspicion, the milk-and-razor scene and the final suicide in Spellbound, the spectacular rescue of Alicia at the end of Notorious, and the efforts of Bruno to retrieve the lighter in Strangers on a Train.

But, come to think of it, what makes something a set piece?

Game, set piece, match

Foreign Correspondent (1940).

As commonly understood in the arts, a set piece is a fairly self-contained portion of a larger work. It has a distinct beginning and end, and it’s understandable and impressive if extracted from its original. It’s designed to be a bravura display of concentrated virtuosity. In music, an example would be an operatic aria like the Queen of the Night’s in The Magic Flute: it is so flashy and complete in itself that it can enjoyed on its own, in a concert setting.

Two early uses of the term shed light on its implications. In stage parlance, a “set piece” is an item of the set that can stand alone, like a gate or fake tree. In pyrotechnics, a “set piece” is a carefully patterned arrangement of fireworks; here again, it implies a display that dazzles the audience.

In the silent era, I’d suggest, the clearest exponent of set pieces is Eisenstein, who became known as “the master of the episode.” Many of his big scenes, like the Odessa Steps massacre, are developed at such length that they function as mini-films. But you can consider passages in Chaplin and Keaton as set pieces—the dance of the breadrolls in The Gold Rush perhaps, or the windstorm in Steambout Bill, Jr. The musical would seem to be a natural home of the set piece, with numbers standing out against more mundane scenes. In modern cinema, again under the aegis of Hitchcock: De Palma offers plenty, and perhaps the prize fights in Raging Bull constitute a string of them. Today the home of the set piece is the action picture; the chases and fights are the main attraction, and the genre challenges directors and crew to find new ways to intoxicate us.

The aesthetic of the set piece implies that some scenes function as filler while others get the whipped-up treatment. If that’s right, many great directors don’t favor mounting set pieces. Ozu, Mizoguchi, Dreyer, Hawks, and others present what we might call “through-composed” films. Just as Wagnerian opera and its successors minimized set pieces, these filmmakers create a surface texture that doesn’t create self-contained high points. (I grant you that the immolation of Herlofs Marthe in Dreyer’s Day of Wrath might count.)

Given the detachable quality of set pieces, it’s true that some of Hitchcock’s can seem implausible or gratuitous. How essential is Guy’s lighter to any plausible scheme of Bruno’s? If you want to kill Roger Thornhill, why send him to a crossroads in Midwest corn country? (A knife in the back on the Greyhound is more reliable.) It was this tendency to sacrifice story logic for stunning anthology bits that Raymond Chandler deplored:

The thing that amuses me about Hitchcock is the way he directs a film in his head before he knows what the story is. You find yourself trying to rationalize the shots he wants to make rather than the story. Every time you get set he jabs you off balance by wanting to do a love scene on top of the Jefferson Memorial or something like that.

Chandler has a point. How do you integrate a set piece into a whole movie? (I’ll make some suggestions shortly.) But first, give Hitch his due. For him, I think a set piece was a compact repository of inherently cinematic ideas carried to a limit within a sequence. A set piece is a challenge: How much can you squeeze out of a situation?

Go back to Foreign Correspondent. Setting an assassination in Amsterdam allowed Hitchcock to integrate the idea of a clue based on a waywardly turning windmill. So far, Chandler’s objection seems tenable: The windmill is just a gimmick. But once Hitchcock sets his hero exploring the lair, he can create a set piece that answers a question that no one ever thought to ask before: How do you eavesdrop in a windmill?

Johnny Jones has to evade the killers by crawling up alongside the giant gears, then down, then up again. At each step he barely escapes being spotted. When he seems safe, his topcoat gets snagged in the grinding gears, so he has to slip his arm out of it—just in time to avoid being crushed.

Yet once Jones is freed from the coat, it’s carried around the gearwork and might be spotted by the gang. And the old diplomat upstairs, mind hazed by drugs, is likely to reveal Jones’ presence. Hitchcock squeezes seven minutes of suspense out of all this, with a casual air that suggests: Of course, dear chap, any director worth his salary can see that a windmill harbors all kinds of excruciating menace. All in a day’s work, you know.

A whispered terror on the breeze

If anything is a set piece, the Albert Hall sequence in The Man Who Knew Too Much is. Philip Kemp’s commentary for the Criterion DVD considers it Hitch’s first, although aficionados would probably consider the “knife” sound montage of Blackmail at the very least a rough sketch for what would come. Lucky you: The entire Albert Hall sequence is excerpted on the Criterion site.

A set piece benefits from a simple premise. Here, Jill’s child is being held hostage, which keeps her from informing the police of what little she knows about the plot. We know that during the concert an assassin will try to shoot a diplomat.

You can imagine Chandler asking: Why plug Ropa during a concert, with all those witnesses? Why not when the target is on the sidewalk, shot from a rooftop for easy escape? You can hear that bland replying murmur: Raaaymond, it’s only a moovie…

So we have some conditions for a set piece: a compact piece of action limited in time and space. But there’s also a strong time marker. Ramon the assassin is to wait for a dramatic pause in the score; it’s followed by a shattering choral outburst that will muffle the pistol shot. We’ve been given a rehearsal of the passage in a gramophone record, but since we don’t hear the whole piece then, we can’t predict exactly when the chorus will hit its peak.

Hitchcock magnifies this uncertainty by letting the piece, Arthur Benjamin’s Storm Clouds Cantata, play out in its entirety. Its combination of lyrical and dramatic passages blend into a stream of music that coincides with the emotional action onscreen. I suspect that the piece, composed specifically for the film, glances at the most celebrated new choral piece of the era, William Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast (1931). It too has a charged dramatic pause followed by a tremendous choral blast: “Slain!” You can listen to it here, and you can hear some of the musical affinities at 27:11 and after.

So the self-contained quality of the sequence is enhanced by the unfolding soundtrack, as well as its “bookend” structure: Jill arrives at the Albert Hall/ Jill leaves. (Hitchcock was very fond of this coming-and-going bracketing; many scenes of The Birds are built out of this.) But to be a set piece we need virtuosity too, right?

As our Film Art essay indicates, Hitchcock structures the scene using nearly every technique in the silent-cinema playbook. We get dynamically accentuated compositions, crisp point-of-view editing, subjective vision (even blurring as Jill drifts into a panicky reverie), and suspenseful crosscutting back to the gang holding Bob and Betty prisoner. The techniques build to their own crescendo, with more and shorter shots of Jill, the orchestra players, and the curtain concealing Ramon. As the climax approaches, details of the players’ performance pass in a flash. As another layer, though, all these visual techniques are synchronized with the musical structure of the piece. Most obvious is the slow tracking shot back from Jill as the female soloist launches in:

There came a whispered terror on the breeze./ And the dark forest shook.

The text has always teased me, because in my early years of studying the film I couldn’t hear everything there. Now that the Storm Clouds Cantata has become a minor concert piece, we have a full version of the text. It’s the description of an especially ominous storm, one that drives birds away and makes trees tremble in fear. The only creature left, vulnerable to the gale, is a child:

Around whose head screaming/ The night-birds wheeled and shot away.

The orchestral and choral forces mount on the line that has always come through the sound mix:

All save the child—all save the child.

The line is ambiguous. Its literal sense is that all the creatures have fled the oncoming storm except the child (“all save the child”). But Hitchcock’s cutting and the film’s overall context leave it as an imperative: the child must be rescued. Thus the musical dynamics and the text stress, for us and presumably for Jill, that Betty’s safety depends on what she does.

Soon the cantata’s text finds another analog in the concert hall. The choir sings of the storm clouds finally breaking and “finding release.” That phrase, repeated with rising intensity, yields the dramatic pause and then the final outburst that is to cover Ramon’s pistol shot. But now we have to see this phrase as prophecy and comment: Jill’s scream during the pause is the release of her tightened anxiety. And of course the line slyly signals the release of the suspense built up through the whole sequence.

With Hitchcock, you always get more.

In all, the sequence becomes exactly what a set piece ought to be: compact, with sharp boundaries and a strongly profiled arc of interest, elaborated with a great variety of technical resources and a thrusting emotional impact. But is it too much of an independent sequence? One can imagine Chandler worrying that Hitch doesn’t care much about how to hook it up with everything else. Let’s see.

This scepter’d isle

There’s no doubt that a plot driven by set pieces can seem episodic, just a matter of pretty clothes clipped to a slender line. In action movies it’s a classic problem, which, say, Speed doesn’t fully solve but Die Hard does.

You can mask an episodic plot, though, through some stratagems. First, make your filler material charming. The Man Who Knew Too Much gives us comedy in the dentist office and in the Tabernacle, with Bob and Clive mumbling messages through hymnody. You can also whisk the audience from scene to scene so quickly that the viewer has to concentrate on local connections. This is one purpose of what I’ve called the hook, the transition that smoothly links the end of one scene with the beginning of the next. If you’ve got some plot holes, strengthen your hooks–especially those that hide your gaps.

The Man Who Knew Too Much has some nifty hooks. I especially like the way the fingers pointing to the bullet hole are followed by a shot of Ramon’s head: effect and cause neatly given by a straight cut. Then there’s the contrast of the fire in the fireplace dissolving to the skier pin, a sort of thermal hook. But probably the most memorable one is Betty’s line about Ramon’s brilliantined hair.

This hook is a motif as well, and recurring images or sounds like this can help knit together your movie. In Foreign Correspondent, we get hats and birds in various scenes. Here, as our Film Art essay indicates, teeth, the skier pin, sharpshooting, the cantata’s main theme, and other motifs weave through the overall structure of the film.

You can as well knit your big scenes together through certain narrative patterns, such as a trip or a search, both strategies that Hitchcock employs in many movies. In The Man Who Knew Too Much, Bob’s investigation of the gang follows the menu set out in Louis’ note: the sun emblem, Wapping, G. Barbour, and A. Hall. This serves as a sort of map for the middle act of the film. Once Bob has cracked the message, though, the film shifts into a new register. Jill, who has been waiting passively at home, takes over the role of protagonist. And her actions will fulfill another motif: that of interruption and distraction.

The film begins with Betty’s dog disrupting Louis’ ski jump. That’s an innocent accident, as is the moment when Jill nearly spoils Roman’s skeet shooting. But soon afterward Abbott’s chiming watch deliberately breaks Jill’s concentration, making her lose the shooting match. In effect the Albert Hall sequence offers payback: With her scream Jill not only disrupts the performance but spoils Ramon’s aim as Abbott had spoiled hers.

The Albert Hall sequence fits into the film in a less obvious way, one that plays along the thematic dualities that marble the movie. Throughout the film contrasts “Englishness” with “foreignness,” the latter split between allies (Louis, Ropa) and enemies. The Storm Cloud Cantata and what follows represent a sort of triumph of England over her adversaries.

At the St. Moritz resort, the Lawrence family is set off from Louis, their French friend, and two men: Abbott the German and Ramon the Latin. (He’s handily fudged; he has a Spanish name but calls the English “extraordinaire.” And his hair is greasy.) “Sworn enemies, eh?” Jill says half-humorously to Ramon before losing the skeet shoot. After Louis’ death Bob is at a loss in the hotel, unable to speak German or Italian, and distracted while Betty is kidnapped. The English aren’t at home in this world.

Once Bob and Jill have returned to London, they join the family friend Clive, a Wodehousian upper-class twit but gifted with loyalty and tenacity. Bob and Clive have learned from Gibson of the Foreign Office that the gang intends to assassinate the diplomat Ropa. They must tell what they know; the killing could prove as catastrophic as the assassination that triggered the war of 1914-1918. Yet Bob keeps mum. He might be enacting E. M. Forster’s dictum: “If I had to choose between betraying my friend and betraying my country, I hope I would have the guts to betray my country.”

The conflict between family love and civic duty is played out in the rest of the second act, when the men’s investigation takes them to a working-class neighborhood of Wapping. There, we learn that behind respectable English institutions—a dentist, eccentric religion—foreign elements lurk. Bob has solved Louis’ riddle, but at the cost of becoming another hostage. Bob and Betty re-meet, in a characteristically subdued stiff-upper-lip encounter that denies Abbott the tearful scene he expected. The dignity with which Bob conducts himself, asking about Betty’s dressing gown and her school grades while staring defiantly at the gang, leaves the others abashed.

Clive has escaped, though, and has managed to send Jill to the Albert Hall. That musical set piece initiates the film’s climax dramatically but also thematically. For one thing, Benjamin’s cantata reaffirms another bit of Englishness. A national choral tradition runs back to Purcell and Handel, was sharpened in Mendelssohn’s Elijah, and was revived in the early twentieth century by Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius and Vaughan Williams’ Sea Symphony. Hitchcock and screenwriter Charles Bennett could have used Bach or Beethoven, but the choice of this brooding, mildly modernistic piece reminiscent of Walton is a nice bit of propaganda for British musical culture of the interwar years.

More importantly, the concert sequence solves the film’s ideological problem: How to save the world without destroying your family? Jill’s impulsive scream doesn’t divulge what she and Bob know about the gang, but it does serve to derail the gang’s plan and save Ropa. And by leading the police to follow Ramon to the hideout, she in effect chooses to risk Betty and Bob for the capture of the gang. Here, perhaps, the sheer drive of the action muffles the significance of her choice; Chandler complains that Hitchcock tended to take refuge from plot problems in “wild chases.”

What follows, in the middle of some violence that remains shocking today, is a vigorous reassertion of Englishness. The vignettes during the siege display stalwart national virtues. A postman insists on making his rounds during the gunplay. An inspector swipes sweets and pauses for a cup of tea. The police reluctantly take up arms, only after several of their unarmed number are mowed down. Slipping into adjacent buildings, snipers move a piano while its fussy owner rescues his potted plant. And a cop who was slated to go off duty finds a warm mattress to die on. This unassuming valor, so different from Ramon’s petulant swagger and Abbott’s self-congratulatory sadism, will win out. The victory is announced by the pent-up crowd rushing jubilantly forward as the siege ends.

In any other movie the mother would have been huddling with the child and the man would grab a rifle to pick off his enemy on the roof. But making Jill the crack shot reasserts another quintessentially English image: the hunting, shooting, riding mistress of the estate. She gets her second chance to fire, bringing down Ramon when even the police sniper hesitates. It’s also a bit of guilty revenge for the death of Louis, whom Jill danced into the line of fire. Hitchcock, as usual, renders it elliptically: we see Jill grab the gun but not fire it. As she and Bob and Betty are reunited, the movie that began with the line, “Are you all right, sir?” ends with a mother reassuring her weeping daughter, “It’s all right.”