Archive for the 'Film technique' Category

Is there a blog in this class? 2012

From the xkcd webcomic

Kristin here:

August is here, and many film teachers are back from summer research trips and starting to prepare syllabi for the fall. Those who are using the new tenth edition of Film Art will have noticed that tucked away in its margins are references to blog entries relevant to the topics of each chapter. But since the new edition went to press, we’ve kept blogging. As has become our tradition, we offer an update on blogs from the past year that teachers might want to consult as they work on their lectures or assign their classes to read. Even if you’re not a teacher, perhaps you’d be interested in seeing some threads that tie together some recent entries.

For past entries in this series, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011.

First, some general entries about the blog itself and the new edition of Film Art. On our blog’s fifth anniversary last year, we posted a brief historical overview of it. That entry contains some links to some of our most popular items. If you’re new to the blog and want some orientation, it could prove useful. Maybe students would be interested as well. At least the photos reveal our penchant for Polynesian adventure and shameless pursuit of celebrities.

In case you haven’t heard about the changes we made for the new Film Art, including our groundbreaking new partnership with the Criterion Collection to provide online examples with clips from classic movies, there’s a summary post available.

And here’s another entry on the new edition, discussing a new emphasis on filmmakers’ decisions and choices.

Now for chapter-by-chapter links.

Chapter 1

Understanding the movie business often means being skeptical of broad claims about supposed trends. We explained why the widespread “slump” of the movies in 2011 was no such thing in “One summer does not a slump make.”

Trying to keep one step ahead of students (or just keep up with them, period) on the conversion to digital projection and its many implications? Our series “Pandora’s Digital Box” explores many aspects:

In multiplexes: “Pandora’s digital box: In the multiplex”

In small-town theaters: “Pandora’s digital box: The last 35 picture show”

At film festivals: “Pandora’s digital box: At the festival”

On home video: “Pandora’s digital box: From the periphery to the center or the one of many centers”

In art-houses: “Pandora’s digital box: Art house, smart house”

Challenges to film archives: “Pandora’s digital box: Pix and pixels”

How projection is controlled from afar: “Pandora’s digital box: Notes on NOCs”

Problems introduced by digital: “Pandora’s digital box: From films to files”

Another case study of a small-town theater: “Pandora’s digital box: Harmony”

Or you can pay $3.99 and get the whole series, updated and with more information and illustrations, as a pdf file.

3D is a technological aspect of cinematography, but it’s also a business strategy. We explore how powerful forces within the industry used it as a stalking horse for digital projection in “It’s good to be the King of the World” and “The Gearheads.”

Independent films can be the basis for blockbuster franchises. “Indie” doesn’t always equal “small,” as we show in “Indie blockbuster franchise is not an oxymoron.”

One of the top American producers and screenwriters of independent films is James Schamus, head of Focus Features. We profile him in “A man and his focus.”

3D is probably here to stay, but it may have already passed its peak of popularity, as we suggest in “As the summer winds down, is 3D doing the same?”

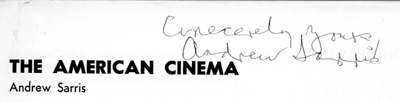

The late Andrew Sarris played a crucial role in shaping the “auteur” theory of cinema. We talk about his work in “Octave’s hop.”

Chapter 2 The Significance of Film Form

“You are my density” is an analysis of motifs in Hollywood cinema, including a detailed look at a scene from Fritz Lang’s Hangmen Also Die.

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

We offer a narrative analysis of a Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, a film many viewers found difficult to follow on first viewing, “TINKER TAILOR: A guide for the perplexed.” A follow-up, “TINKER TAILOR once more: Tradecraft,” concentrates on the adaptation of Le Carré’s novel.

A tricky narrative structure in Johnnie To’s Life without Principle called forth our entry, “Principle, with interest.”

In “John Ford and the Citizen Kane assumption,” we consider the possibility that Kane, analyzed in this chapter, might not be the greatest movie ever made.

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-scene

For some reason teachers (and apparently students) always want more, more, more on acting, the most difficult technique of mise-en-scene to pin down. “Hand jive” talks about hand gestures, which in the past were used a lot more than they are now. “Bette Davis eyelids” takes a close look at the subtleties of Bette Davis’ use of her eyes.

“You are my density,” already mentioned, offers several examples of dynamic staging in depth.

Chapter 8 Summary: Style as a Formal System

We have posted two entries dealing with form and style, specifically experimental artifice in 1940s Hollywood. These could be of interest to advanced students. “Puppetry and ventriloquism” deals in general with the topic, while “Play it again, Joan” looks at scenes that replay the same action or situation. The latter contains an analysis of a lengthy scene of Joan Crawford performing that could be useful in discussing staging and acting for Chapter 4.

Chapter 9 Film Genres

If you teach a unit on genre and choose to focus on mysteries, “I love a mystery: Extra-credit reading” gives some historical background information on the genre in popular literature and cinema.

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

“Solomonic judgments” centers on the gorgeous experimental films of Phil Solomon.

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

Our discussion of Tokyo Story in Film Art could be supplemented by this brief birthday tribute: “A modest extravagance: Four looks at Ozu.”

Chapter 12 Historical Change in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

Last September I found an extraordinary little piece of formal and stylistic analysis using video, Variation: The Sunbeam, David W. Griffith, 1912. A Spanish film student, Aitor Gametxo, had displayed the staging and cutting patterns of Griffith’s Biograph short, The Sunbeam, by laying out the shots in a grid reflecting the actual spatial relations among the sets and running the action in real time. If you teach a history unit or just want an elegant, clear example of how editing of contiguous spaces works, this is a wonderful teaching tool. Classes may be particularly intrigued that a student was able to put together something this insightful. Plus The Sunbeam is a charming film that would probably appeal to students more than a lot of early cinema would. See “Variations on a Sunbeam: Exploring a Griffith Biograph film.” Gametxo’s film also provides an elegant example of how editing of adjacent spaces works and could be a useful teaching tool for Chapter 6.

Teachers showing a Georges Méliès film might have their students read “HUGO: Scorsese’s birthday present to George Méliès,” which has some background information on the career of this cinematic conjurer.

German silent film was the focus of “Not-quite-lost shadows.”

Not strictly on the blog, but alongside it, is a survey of how developments in film history generated changes in film theory. The essay is “The Viewer’s Share: Models of Mind in Explaining Film.”

Further general suggestions

Looking for some new and interesting films to add to your syllabus? We cover quite a few in our dispatches from the Vancouver International Film Festival 2011: “Reasons for cinephile optimism,” “Son of seduced by structure,” “Ponds and performers: Two experimental documentaries,” “Middle-Eastern crowd-pleasers in Vancouver,” and “More VIFF vitality, plain and fancy.”

Or if you seek information on historical films newly available on DVD, we occasionally post wrap-ups of recent releases, including a cornucopia of international silent films. See “Silents nights: DVD stocking-stuffers for those long winter evenings.”

We have also carried on our tradition of a year-end ten-best list—but of films from 90 years ago. Not all the films on our list for 1921 are on DVD, but most are: “The ten best films of … 1921.”

Every now and then we post an entry pointing to informative DVD supplements that might be useful teaching tools. It’s surprising how few of them go beyond a superficial level where the actors and filmmakers sit around praising each other: “Beyond praise 5: Still more supplements that really tell you something.”

Beyond praise 5: Still more supplements that really tell you something

Real-time performance-capture images for The Adventures of Tintin.

Kristin here:

The Extraordinary Voyage (2011, Serge Bromberg and Eric Lange)

I had expected to follow up my entry on Hugo when the DVD was released. I anticipated that its supplements would explore the flashy technical and artistic aspects in detail. But the lengthy first chapter proved to be largely the cast and crew presenting variations on how lucky they were to have worked with Martin Scorsese (and each other) and how much they learned from him.

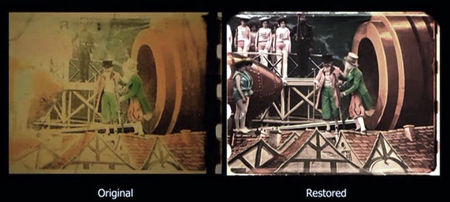

That wasn’t promising, and I turned instead to Georges Méliès himself. Flicker Alley, which has served the filmmaker so well in the past (see here), has recently released the restored color version of A Trip to the Moon in a Blu-ray/DVD combination set. It is accompanied by a 65-minute documentary on the Méliès, the film, and the restoration. It’s odd to call a 65-minute film that accompanies a fifteen-minute “feature” a supplement, but I recommend it anyway.

I suspect that The Extraordinary Voyage would be quite effective in easing students into very early silent cinema and intriguing them about an era that must seem hopelessly remote to them. It begins with a charming introduction to the context of the turn of the previous century and then moves quickly into the director’s young-adult life. When it comes to the famous incident in which Méliès’ camera jammed while he was filming, creating an inadvertent magical transformation, the filmmakers have an actual 1937 recording of Méliès himself describing the event. Presumably this was the original source of this oft-repeated anecdote. He specifies that it happened on the Place de l’Opéra and involved a bus turning into a hearse. I still wonder if it all happened so neatly, but hearing it directly from Méliès makes it a little more plausible. If it wasn’t true, it should have been.

The film includes as talking heads several filmmakers who admire Méliès’ work: Costa-Gavras, Jean-Pierre Jeunet, Michael Gondry, Tom Hanks, and Michel Hazanavicius. There is a good summary of the fascination with the moon in popular culture of the day,  including works by Jules Verne, Jacques Offenbach, and H. G. Wells.

including works by Jules Verne, Jacques Offenbach, and H. G. Wells.

The documentary touches on issues relevant to early silent cinema in general. One of these is the frequent pirating of films, with Méliès starting an American branch of his Star Films in New York, under the direction of his brother Gaston, to help protect his intellectual property. A clip from the Segundo de Chomon version of the film, An Excursion to the Moon, is included.

At about 23 minutes in, a short overview of early movie music is given, followed by a helpful explanation of how the hand-coloring of Méliès’ films was handled by a local workshop run by women. At 30 minutes in there are several dazzling examples of hand-colored scenes (right).

After a quick summary of Méliès’ decline and death, the film moves to the restoration of the only known hand-colored copy of A Trip to the Moon, found in the film archive in Barcelona. Here the hero is Tom Burton, the Director of Technicolor Creative Services, who gives a brief indication of how computers have transformed restoration:

We have a palette of digital tools to work from that are a collection of maybe five or six of the main commercially available restoration platforms, but then we also bring into the mix all of the approaches that you would use if you were doing visual effects for a modern movie.

The comparison of visual effects with restoration is in some ways an apt one and might lead students to look upon early films in a new light.

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (Blu-ray/DVD/Ultraviolet set, Sony Pictures Home Entertainment)

It’s probably a good idea to supply both Blu-ray and DVD discs in one package, but including the supplements only in Blu-ray is annoying and increasingly common. That’s the way the Girl with the Dragon Tattoo discs have been handled. Teachers without access to a Blu-ray player have fewer options when trying to use supplements in teaching. It also makes it much more difficult to make frame grabs from the supplements to, say, illustrate a blog entry on useful supplements.

I decided to check out the supplements for this film because the ones for Zodiac and The Social Network were so good. I figured David Fincher was particularly concerned about his films’ bonus materials. Unfortunately this set of supplements is quite uneven. The cast and crew seem to be obsessed with the character of the heroine and with the delights of shooting in Sweden. I confess that I stopped watching some of the chapters as the talking heads went on and on about these subjects. Some of the tracks also consisted of a lot of candid behind-the-scenes footage, which is all very well, but there was little structure to this and only occasional comments to explain what was going on.

Fortunately the “Post-Production” section is very informative and interesting. “In the Cutting Room” is fairly technical but makes some fascinating points. I particularly liked the description of how Fincher eliminates reframings and unsteady shots by using the extra image space allowed by newer capture media. (Earlier digital film frames allowed no extra image area outside what would show up on the screen; as the image below indicates, the final frame can be selected from a larger picture.) This desire for a stable image in an era where the “queasi-cam” so often rules points to one distinctive trait in Fincher’s style. It indicates a willingness to actually think through the framing of each individual shot and the purpose for choosing that framing. Steven Spielberg does the same thing. Many don’t.

Editor Angus Wall talks about this advantage of the extra size of the image and how Fincher uses it to stabilize unsteady images. It’s worth quoting at length, and it demonstrates the thoughtful commentary in this particular supplement:

I’ve never seen a movie that was sort of “re-operated” to the extent that this one was. Which I think has an effect on the viewing of the movie. David is really type-A in terms of making the shots very specific. They start in a certain way, they end in a certain way. And the framing, he’s very precise in terms of his composition. He doesn’t like a lot of what you see in 99% of movies, which is very subtle moves where the operator will actually reframe according to how the actor’s moving. David doesn’t like that. Even if there were a lot of those in this film, and before, some of those takes we would have thrown out, because we just wouldn’t have been able to stabilize them to the degree that he likes it. With this, because you have this full raster, this big area around the image, you can take those images and stabilize them, really lock them down. So the movie is really locked down in terms of camera operating. More than any other movie that I can think of.

The smooth glide as the car initially approaches the country house is one example of that utter stability, used to ominous effect in that particular scene.

There’s also some interesting discussion about how the two main characters don’t meet each other until well into the film and how that affected decisions about editing. Rather than frequently intercutting between Mikael Blomkvist and Lisbeth Salander, the filmmakers decided to create longer self-contained scenes involving each, thus switching back and forth less frequently. The idea was that the exposition set forth in each scene would be too difficult to absorb if it was chopped into smaller segments. Form, style, and function, neatly explained.

Fincher also points to an interesting underlying anxiety the spectator might feel because the narrative progress gives little sense of how much action is still to come:

You don’t know where you are in the narrative. You don’t know if you’re at the beginning of the third act or … I don’t think it’s bad, because we have a five-act movie. I think that’s what’s causing everybody’s anxieties, that it doesn’t feel like, OK, here’s where we are, we’re entering the third act now. Now it feels like, fuck, this movie could go on … indefinitely. That’s the part that’s bothering me. If we told them it was going on for another forty-five minutes, they wouldn’t have a problem. It’s the indefinite part.

Since I’ve written a book claiming that classical films usually don’t have three acts, I was intrigued by this statement. (See also my earlier blog entry here and David’s essay here.) I posit instead that classical films typically create acts that run about 25 to 30 minutes, and that the film’s length determines how many acts it has. Four acts is the most common throughout Hollywood’s history, but a 158-minute film would be likely to have five acts. (Has David Fincher read my book?!) His point about the audience feeling a bit lost in an unconventional narrative structure is a rare instance of a director talking about form in such an abstract way, and it seems quite valid for The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

It’s also rare to get a supplement on ADR (automated [or additional] dialogue replacement), but there’s a six-minute one in the “Post-Production” section. This consists of a behind-the-scenes session with Rooney Mara supplying not just dialogue but breathing, grunts, and other noises. It’s clearly a real session, not a staged one, though the actress does seem a bit self-conscious with the documentarian’s camera turned on her. Fincher’s and Mara’s banter between takes gives a sense of what I suspect really goes on during this phase of production.

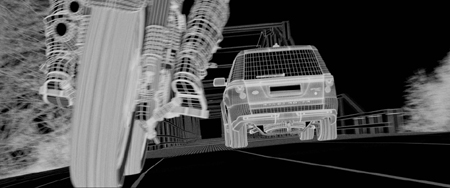

There’s a brief supplement called “Main Titles,” which deals with the form and inspiration for the CGI under the titles. Fincher wanted to tell the story of the whole trilogy in two and a half minutes, “and it has to be spectacular.” Apart from the discussion of form, there’s a good look at unrendered CGI footage compared to the finished images.

Finally, an eight-minute “Visual Effects Montage” displays a variety of special effects in a clever way. There is a section at the beginning where we are shown the image without added effects, then the same image with the areas to be altered highlighted in various superimposed colors, and finally the finished images with the effects added. This is particularly good for showing the sorts of mundane effects that are used to enhance shots unnoticeably, adding cars’ headlight beams, reflections in glass, falling snow, and the like. There is a shot with a section of a building on location blotted out with a greenscreen and the final shot showing the use of alterations in the building:

Obviously here the fog was also added with CGI.

This montage goes very quickly. If you’re using it in a class, best to prepare ahead and be ready to pause and point out what’s going on in the many short shots used in the demonstrations.

The second half of the effects montage moves to splashier scenes of the type the public associates with “special effects”: wire-frame vehicles for a chase (see image at the top of this section), head-replacement to add Mara’s head to her stunt-double’s body, and explosions.

Don’t bother with the “Stockholm Syndrome” section. Basically all we learn is that when a scene is shot on location, sheep can unexpectedly wander in and interfere.

The Adventures of Tintin (Blu-ray/DVD/Digital Copy combo, Paramount Pictures)

Again, the supplements for this release are available only in Blu-ray.

Steven Spielberg and Peter Jackson decided some years ago to collaborate on what was announced to be a three-film series adapted from Hergé’s Tintin comic books. The notion was that each of them would direct one film, with an as-yet-unspecified director doing the third. Spielberg’s initiatory film did not do as well at the domestic box-office as had been hoped, though it fared better in Europe and other non-North American markets, where the comics are highly popular. Jackson has announced that after he finishes both parts of The Hobbit, he will launch into the next Tintin film. (At least, that’s what he said originally. After yesterday’s announcement that there will be three Hobbit films, his start on the Tintin film will presumably be delayed.)

The supplements form a narrative of the film’s making, bookended by “Toasting Tintin” and “Toasting Tintin Part 2,” brief episodes set at the launch and wrap parties. The tale is pleasant and generally worth watching, though they are far from as entertaining and informative as the supplements that Michael Pellerin produced and directed for Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings and King Kong DVD sets. But this is Spielberg’s show, since he did the first film and indeed originated the project. At first he envisioned the film as live-action, with the dog Snowy the only major CGI character. Spielberg asked Jackson’s effects house Weta Digital to do some tests animating Snowy. To his (apparent) surprise, Jackson himself, as a fan of the comics since childhood, played Captain Haddock in the test. That fact was well known to fans, and the inclusion of the test footage (above) is no doubt a crowd-pleaser.

The decision to use cutting-edge performance-capture techniques led to the film being entirely animated.

“The World of Tintin” gives background on Hergé and deals briefly with the screenwriting process. This leads into “The Who’s Who of Tintin,” dealing with characters and acting, with some good material on performance capture near the end. The next section, “Tintin: Conceptual Design” has good material on the visual style of the characters and near the end includes some pre-viz material.

The outstanding supplement, however, is “Tintin: In the Volume,” nearly 18 minutes of footage concerning performance capture. Spielberg’s role as director was primarily concentrated into a remarkably short 31-day shoot with the actors. This was done in a state-of-the-art performance-capture facility called “The Volume” and located at Giant Studios. The Volume is a large space with about 160 cameras built into the ceiling and pointing down into the performance space. These capture the space from multiple angles. Additional cameras on the stage level follow the actors’ movements, which are inserted into the space. Moreover, hand-held monitors similar to portable gaming devices allow the filmmakers to see simple versions of the settings and the partially rendered characters while pointing the device at the actors in their performance-capture rigs.

There are also larger monitors that show the actors their own performances translated into the characters (top of entry). Whatever one thinks of the look of contemporary animation of this type, the technology has evolved to a remarkable level, and this supplement provides an excellent explanation of the practicalities of performance capture. We see the motion-capture suits being put on and the dots painted onto the actors’ skin. There is also information on how the set elements and props need to be transparent so that the cameras can capture the dots on the actors’ faces and costumes through them. The image at the bottom shows Jamie Bell as Tintin looking at a mock-up of the model ship. It’s made of little metal rods and rendered into a ship on the monitors.

“Snowy: From Beginning to End” is less cutesy than it sounds. It discussed the digital tool developed for modeling the dog’s fur. There’s also good stuff on how several dogs were recorded to provide different-sounding barks depending on the type of action in a scene.

The biggest tasks on the film came after the performance capture and editing. Weta Digital spent two years creating the final images. “Animating Tintin” is an excellent eleven-minute account of that process.

The sections “Tintin: The Score” and “Collecting Tintin” (on Weta Workshop’s designs for the collectible figures) are rather thin and could be skipped unless a teacher wants to show the whole set of supplements as a single “making-of” documentary.

It’s become apparent that many of the best supplements on Blu-ray and/or DVD releases are devoted to special effects, especially performance capture. The Adventures of Tintin does genuinely involve innovations in this technology, and the “In the Volume” chapter is very informative. Supplements are getting repetitive, though, and I would like to see the producers of such documentaries pay more attention to techniques and choices in other areas. Comparing final cuts of scenes with earlier cuts, or showing story conferences where real debates about scripts occur (as was done in the first Pirates of the Caribbean film’s supplements), or displaying how decisions about digital-intermediate grading are made–a bit of imagination could spice up the offerings. That and a realization that film fans are interested in just about any aspect of production (or distribution, for that matter). Supplements risk falling into conventional patterns, and that won’t make them the appealing bonus material that they used to be.

While I was gearing up to write this entry, we received Mark Parker and Deborah Parker’s book, The DVD and the Study of Film: The Attainable Text (Palgrave, 2011). Based on a great deal of research, including many interviews, the authors include a summary history of DVDs and supplements; there is a detailed chapter on The Criterion Collection, interviews with directors and scholars who have recorded commentary tracks, and a case study of Atom Egoyan.

You the filmmaker: Control, choice, and constraint

DB here:

The tenth edition of our textbook, Film Art: An Introduction will be available in early July. It has so many new features that it’s our most extensive revision in at least a decade.

Kristin has already written about one of our major additions: supplemental film extracts from the Criterion Collection, with voice-over commentary and other sorts of analysis. (Go here for a sample.) These will be accessible to professors for incorporation into their syllabi. More of them may also become generally available on the Criterion website.

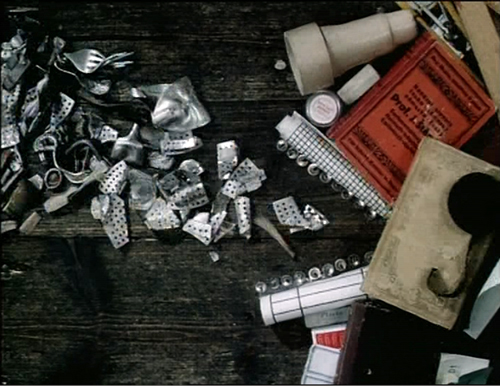

The text has been extensively rewritten, aiming at maximal clarity and freshness. There are many local changes too, with updated examples from a variety of films both old and new. Regular readers will notice that we have made two replacements: Koyaanisqatsi is now our example of associational form, and Švankmajer’s Dimensions of Dialogue is our example of experimental animation. Regretfully, we had to drop our earlier examples, Bruce Conner’s A Movie and Robert Breer’s Fuji, because they are available only in 16mm, and most teachers and readers don’t have access to them. On the other hand, we enjoyed analyzing the new items and think that they serve their purpose very well.

Today I’m going to point out some of the broader changes, while also considering the book’s overall approach.

Parts and wholes

When Film Art appeared in 1979, it was the first textbook in English written by people who had received Ph.D.s in film studies. Specifically, FA emerged from my teaching a lecture-and-discussion course called “Introduction to Film” to several hundred students each semester for many years.

In the mid-seventies, there were almost no film studies textbooks, and none of them seemed to us to reflect the directions of current research. As a result, the first edition of FA included topics that were emerging in the field, such as narrative theory and conceptions of ideology. It also suggested a coherent, comprehensive view of cinematic art, from avant-garde and documentary cinema to mainstream film and “art cinema.”

The book has changed since then, but its approach has remained consistent in two primary respects. For one thing, it tries to survey the basic techniques of the medium in a systematic fashion. Here the key word is “systematic.” It seemed to us that we might go beyond simple mentioning this or that technique—editing, or acting, or sound—and instead treat each technique in a more logical and thorough way. But film aesthetics wasn’t yet conceived in this way, so to a considerable extent the textbook had to offer some original ideas.

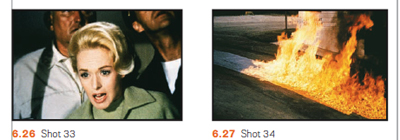

For example, most people thought of editing primarily as a means of advancing the film’s story. That’s certainly accurate up to a point, but we tried to go up a level of abstraction. We suggested that the change from shot to shot had implications for what was represented (the space shown in the shots, the time of the action presented), as well as for the sheer graphic and rhythmic qualities onscreen, independent of what was shown. That created four dimensions that the filmmaker could control, and we illustrated how Hitchcock shaped all of them in a sequence from The Birds.

Nobody before had surveyed editing’s possibilities in this multidimensional way. The result was that we were able to trace out several expressive options. We analyzed the 180-degree system for presenting story space, and Film Art became the first film appreciation textbook to explain this. We also laid out ways in which shots could manipulate the order, duration, and frequency of story action. We also considered sheerly graphic and rhythmic possibilities of editing, not all of which are tied to narrative purposes. Similarly, we tried to show that sound, another familiar technique, could be understood as a bundle of systematic options relating to sound quality, locations in space, relation to time, and other factors.

In sum, very often the array technical options had an inner logic. This urge to cover all bases helped us notice options that usually escaped critics. So by concentrating on the graphic dimension of editing, we noticed that some filmmakers tried to create pictorial carryovers from shot to shot, a device we called the “graphic match.”

A second core principle of the book was the idea that we ought to think about films as wholes. There’s a strong tendency in film criticism, in both print and the net, to fasten on memorable single sequences for study. There’s nothing wrong with this, of course, but we think it needs to be balanced by considering how all the sequences in a film fit together. That led us to consider various types of large-scale form, both narrative and non-narrative.

Again, this was new to the field. We showed students how to divide films into parts and then trace patterns of progression and coherence across them. This is a valuable skill for both intelligent viewers and people who might want to work in filmmaking. We showed how the distinction between story and plot could help explain large-scale narrative construction. We suggested that issues of point-of-view and range of character knowledge exemplified broader principles of narration, the ways films pass information along on a moment-by-moment basis. And although most film courses show narrative films (mine did too), we wanted students to think about other large-scale organizational principles too, such as rhetorical argument and associational form. Again, thinking about these more general possibilities led us to consider creative options that hadn’t been the province of introductory texts, such as rhetorical documentary and poetic experimental cinema.

These two efforts—comprehensive study of techniques and a holistic emphasis on total form—weren’t FA’s only salient points. We tried to incorporate more familiar elements from genre studies and historical research. But they did set the book apart, and do still. I believe that we made contributions to our understanding of film aesthetics. One measure of these contributions is the extent to which FA has been regarded as not only a textbook but an original contribution to film aesthetics. Another sign is the fact that other textbooks have relied, sometimes to a startling degree, upon FA for concepts, organization, and examples.

Categories, categories

Associational form: Koyaanisqatsi.

Still, we did encounter objections.

Some readers worried that FA’s layout of logical categories took away some of the magic and mystery: Art dies under dissection. Some also protested that filmmakers didn’t use the categories and terms we invoked. These concerns have, I think, waned a bit over the years, but I’ll address them anyhow.

First, as to the need for categories. As a genre, the textbook in art theory has a very old ancestry. Aristotle’s Poetics, a survey of what we’d now call literary art, bristles with categories—drama vs. epic, comedy vs. tragedy, types of plots, etc. In the visual and musical arts, from the Middle Ages into the Renaissance, writers tried to systematically understand the principles of artists’ practice. Leon Battista Alberti’s treatise on painting tried to show that as an activity, painting had many “parts,” such as drawing, color, and light.

This classificatory urge continued through the centuries, and it continues today. Pick up a book on the visual arts today and you’ll see chapters on composition, color, texture, and the like. The same goes for music; an introductory book will survey rhythm, harmony, melody, musical forms, and so on. There’s no escaping some sort of categorizing if we want to understand any subject, and this goes as well for art traditions.

The categories governing centuries-old arts are largely taken for granted. But film is a newish medium, and film studies a still-young academic discipline, so there remains a lot of exploratory thinking to be done. In the late 1970s, Film Art undertook some of that exploration.

A lot of thinking about film employs categories that are very abstract and general (say, “realism” versus “non-realism”). Our frame of reference tries to be more concrete, more fitted to the particularity of what films actually look and sound like. Whenever we could, we incorporated filmmakers’ explicit concepts into our analyses. FA, for instance, was the first appreciation textbook to introduce the principles of continuity editing that were craft routines among directors and cinematographers.

At other times, we tried to synthesize ideas that were circulating in the filmmaking community. For example, for several decades filmmakers and critics have been saying that editing is getting faster, close-ups are getting more prominent, and camera movements are becoming more salient, even aggressive. From studying hundreds of films, we came to the conclusion that these trends are part of a new approach to film style, and we dubbed that “intensified continuity.” That term aims to capture the idea that for the most part these techniques are in accord with traditional continuity editing, but they sharpen and heighten its effect.

Occasionally we tried to clarify concepts. Most notoriously, we borrowed from French film theory the distinction between “diegetic” and “nondiegetic” sound because all the other terms (“source music,” “narrative music,” etc.) seemed to us ambiguous or inexact. As with most categories, individual films can play with or override this distinction, but it’s a plausible point of departure because traditionally the distinction is respected.

Contrary to some objections, then, we often worked with ideas used by practicing filmmakers. Where traditional terminology seemed inadequate to those ideas, we created our own. And some effects we may notice in movies may have no currently accepted names. In some cases, as in the graphic match, the phenomenon may not even have been identified. We haven’t tried to conjure up fancy labels; we’ve just tried to point to the ways some films work. Anyhow, the term doesn’t matter much, but the concept does.

So one way to think about the categories of form and style in FA is to see them as bringing out principles underlying filmmakers’ practical decisions. A director may choose to do something on the basis of intuition, but we can backtrack and reconstruct the choice situation she faced. If we want to survey the possibilities of the medium, one way to do it is to build categories that show the expressive options available, even if filmmakers don’t sit down and brood on each one.

Thinking like a filmmaker

Walt Disney’s Taxi Driver (Bryan Boyce).

Categories are inevitable, and they allow us to consider creative choices systematically. Making this second point explicit is the most important overall revision in the new version of Film Art.

Previous editions took the perspective of the film viewer. This is reasonable: Teachers want to enhance their students’ skills in noticing and appreciating things in the movies. But from the start FA also indicated that the things we discussed also mattered to filmmakers. As the years went by, we incorporated more comments and ideas from screenwriters, cinematographers, sound designers, directors, and other artisans—often as marginal quotes that, we hoped, would reinforce or counter something in the main text.

Now, though, we’ve shifted the perspective more strongly toward the filmmaker—or rather, toward getting the viewer to think like a filmmaker.

Until recently, most of our readers hadn’t tried their hand at making movies. But with the rise of digital media, a great many young people have begun making their own films. Some of these are variants of home movies, records of concerts or parties or a night out. But many of these DIY films are more thoroughly worked over. They’re planned, shot, and cut with considerable care. Posted on YouTube or Vimeo, they exist as creative efforts in cinema no less than the films that get released to theatres or TV. If you doubt it, look at lipdubs, or meticulous mashups like Bryan Boyce’s.

So, we thought, many students are now able to consider film art as practicing filmmakers. For one thing, that means they’re more aware of the techniques we explain. (Probably nothing in Film Art is as tough as mastering Final Cut Pro.) Moreover, the very act of making films has made students sensitive to alternative ways of doing anything. Accordingly, this edition emphasizes that the resources of the film medium that we survey constitute potential creative choices which yield different effects.

Take an example. We can explain the idea of restricted versus unrestricted narration abstractly. Restricted narration ties you to a limited range of knowledge about the story action; unrestricted narration expands that range, often presenting action that no single character could know about. Filmmakers intuitively make choices along this spectrum even if they don’t use the terminology. Then again, sometimes they do. A while back we quoted the director of Cloverfield:

The point of view was so restricted, it felt really fresh. It was one of the things that attracted me [to this project]. You are with this group of people and then this event happens and they do their best to understand it and survive it, and that’s all they know.

In Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus, the hero and three other captives are chosen to fight in the arena. They sit sealed in the holding pen while we hear Crassus and his elite colleagues chatting pleasantly about their trivial affairs.

When the combat starts, we’re still confined to the shed. Crixus and Galeno are summoned out, and the door slides shut, leaving Spartacus and Draba alone.

The director has already made several important choices, notably contrasting the carefree chatter of the rulers with the grim prospects of the gladiators (the latter underscored by relentless music). But now there’s a big fork in the road: To show the first combat, or not?

Kubrick chooses not to. We hear the call, “Those who are about to die salute you!” We hear swords clashing, and Spartacus peers outside through the slats. We see only what he sees.

Draba studies Spartacus, who closes his eyes to shut out the spectacle outside.

The two men share a look, but Spartacus turns his gaze away, as if unwilling to confront the cost of killing this man who has done him no harm.

This stretch of the scene is too detailed and varied for me to replay in full, but it’s all confined to the two men in the shed—their reactions to what they hear and what Spartacus sees, and the development of a mix of wary appraisal and desperation. No words are spoken.

The fight outside concludes, and at the climactic moment Kubrick cuts to a new angle that puts Draba and Spartacus in the same frame, realizing that their time has come. The door slides open again, and the men step out.

The exchange of glances has been just ambiguous enough to make us wonder whether the two will really try to kill one another. Restricting us to the holding pen gives us a moment to watch them pondering their fates and enhances the suspense about the outcome of their fight.

Every instant presents the director with a choice that can shape the viewer’s experience. When the men go out, Kubrick must decide on what to show us next. Most daringly, he could keep us in the shed and let us glimpse the fight from there. But that would be a very unusual option in American commercial cinema. Instead, the next shots expand our range of knowledge by shifting us to a different character’s reaction. Before showing us the arena, we get a shot of Virinia, the slave just bought by Crassus. As a result, she is marked as important before we get a general shot of the arena.

Eventally, a master shot ties together all the characters before we move to the next phase of the scene.

As Darba and Spartacus start their fight, you can argue that the effect of it is even stronger because we haven’t seen the earlier match. Restricted presentation of the first combat, seen only through Spartacus’s eyes, throws the emphasis on this one.

By shifting our attention to filmmakers’ areas of choice, we haven’t really abandoned thinking from the standpoint of the spectator. The two views complement each other. In effect, we’re reverse-engineering: thinking like a filmmaker sharpens our sense of how the spectator’s experience can be shaped. From either perspective, we need concepts, categories, and terminology.

To futz or not to futz?

Undercover Man (1949).

Once we notice the concrete results of creative choices by director, cinematographer, editor, and others, we’re inclined to compare how filmmakers have pursued different options, and how these decisions yield different effects. So you might contrast Kubrick’s treatment of the combat with the free-for-all in Ridley Scott’s Gladiator. There the period of waiting is short, and all the emphasis is put on the bloody combat.

Film Art uses the comparative method often, again to illustrate the range of choice available to the filmmaker. Let’s take some instances that have implications for both narration and sound. Telephone conversations are a staple of filmic storytelling. In such a scene, you as a director face a decision tree. Whatever you choose leads to other choices.

Should you show both characters in the conversation, or only one? A passage from The Big Clock presents both options, one after the other.

This illustration suggests that if the character on the other line plays a significant role in the story, you may want to show him or her. Max isn’t as important as Stroud’s wife and son. Once you’ve decided to cut back and forth, you’ll still have to decide when to cut—at what points to show us characters’ reactions. You might want to replay this clip to see how the cutting pattern highlights certain responses.

Alternatively, you can stick with one character and conceal the other party, even if that character is important. Here’s an example from Joseph H. Lewis’s Undercover Man.

Unlike Max in the Big Clock scene, this caller is an important character, a prospective snitch. By not showing him on the other end of the line, Lewis concentrates our attention on the federal agents and builds a little suspense. He goes even further: By not cutting in to Warren as he talks, the direction emphasizes the reactions of Judy, Warren’s wife. Her response is highlighted when she turns slightly into profile, registering her realization that her husband has to leave her on a dangerous mission sooner than she expected.

Sticking with one character triggers another choice about telephone talk: Do you let us hear the other party or not? So far, all our examples have suppressed the voice of the person on the other end of the line. But of course you could let the viewer hear that.

There’s a new problem coming up, though. You need to make it clear that the voice is coming through the receiver, not from someone outside the frame. So a convention has arisen: Words coming through the phone line are distorted, in a process called “futzing.” Here’s an example of subdued futzing from I Walk Alone.

And here’s a case from The Blue Dahlia illustrating the difference between the two sorts of sound even more sharply. Here it’s especially important to let the audience know that what’s being heard is a recording.

This isn’t to say that every choice is absolutely fixed. You can experiment. This is what King Vidor did in H. M. Pulham, Esq. Pulham gets a call, and though we stay with him, the voice isn’t futzed; the effect is a bit unnerving.

Vidor explains:

We were breaking with tradition. When the sound men took over, it became the cliché to put all telephone voices through some sort of filtering device. This made it sound distorted and weird. It occurred to me, why should the audience strain to listen? The person with the receiver up there on the screen doesn’t strain to hear the voice. There isn’t any kind of mechanical distortion. I thought we should just direct it to sound the way it sounded to the person.

The film’s plot concerns Pulham’s regrets about the missed opportunities of his youth. When he gets calls from old friends, their voices seem unusually immediate, more vital and “present” for him than the people in the life he’s leading now.

These creative options show how even small stylistic decisions affect narration and the viewer’s response. Presenting both characters on the phone creates more unrestricted narration, and this allows us to gauge reactions to the action. By showing only one character, you concentrate on that person and the people around them.

If you suppress the words spoken on the other end of the line, you maintain some uncertainty about what’s happening, and you don’t share with us what the listener knows. In contrast, if you let us hear what the listener hears, you tie us to their range of knowledge and perhaps create a bond with them. And as Vidor suggests, you can try to create a deeper subjectivity by letting us hear the speaker as the listener does.

Although Vidor’s experiment wasn’t taken up, directors have continued to try different ways of rendering phone conversations. It would be fun to compare Larry Cohen’s two “phone” scripts, Cellular and Phone Booth, in these terms—not least because of the eerie sound design applied to the mysterious caller harassing the hero of Phone Booth.

Choice and change in history

Un Chien andalou (1928); Blue Velvet (1986).

In such ways, the categories we survey can be thought of as a range of possible options facing filmmakers. But all of them aren’t available to every filmmaker. As every filmmaker knows, you choose within constraints, and some of those constraints are the result of history.

As in earlier editions, Film Art concludes with a chapter surveying artistic trends across film history. But now we’ve tried to integrate the idea of thinking like a filmmaker into that section, emphasizing the interplay of choice and constraint. Most obviously, budgets limit choices. Other constraints might be technological; not all filmmakers have been able to film in color, or to use advanced special effects. Some constraints involve matters of fashion: some acting styles and staging methods aren’t widely acceptable today. In our final chapter we show how certain traditions and schools of filmmaking confronted the constraints of their period and place. Sometimes filmmakers worked within those constraints, and sometimes they overcame them by trying something different.

At the same time, we break with our previous editions by weaving recent films into the history chapter. We try to show that the expressive choices made by filmmakers long ago have returned in our time. The earliest short films, based on novelty and surprise events, have successors in YouTube videos. Contemporary filmmakers draw on techniques favored by German Expressionism and French Impressionism. (Recent examples on the blog are here and here.) Current Iranian films owe a good deal to Italian Neorealism, while the Dogme filmmakers tried to revive some of the insolent force of the French New Wave. It isn’t just a matter of influence, either. Contemporary filmmakers face problems of storytelling and style that others have faced before. The choices our filmmakers make often recall those made in the past.

We’re very proud of this edition of Film Art. We hope that the changes will whet the interests of teachers, students, film lovers, and that generic “curious general reader”—who, we persist in believing, isn’t mythical.

Just to be clear: Our Spartacus example doesn’t appear in the book. Our layout of choices about handling phone conversations does, but with different examples. Thanks to Kevin Lee and Jim Emerson for advice on video embedding.

King Vidor’s remarks about H. M. Pulham, Esq. are taken from Nancy Dowd and David Shepard, King Vidor: A Directors Guild of America Oral History (Scarecrow, 1988), 188. A library of futzed sound clips is here. For a more detailed study of how phone conversations may be presented through both sound and image, see Michel Chion’s Film, A Sound Art, trans. Claudia Gorbman (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 365-371. (An outline of his typology is here, in French.) Chion’s research is a good example of showing how a systematic set of principles can underlie the practical decisions facing filmmakers.

Alert reader Chris Freitag has steered me to a recent and fine lipdub here. It exemplifies how competition within a genre can spur innovation. More specifically, how to create a new sort of lipdub? Well, how about proposing marriage?

Instructors interested in obtaining a desk copy of Film Art: An Introduction can visit this website.

Dimensions of Dialogue (1982).

P.S. 27 June: Some correspondence I’ve just gotten reminds me of two things I neglected to mention in the entry. First, this edition of Film Art contains a great deal more material on digital cinema, from production and postproduction through to distribution and exhibition. We’ve woven digital technology into sections on various techniques, particularly cinematography, and we’ve added material on 3D cinema.

Second, our decision to replace our sections on A Movie and Fuji doesn’t mean that those discussions will vanish forever. For some years we’ve been putting up older Film Art material as pdf files on this wing of the site. Later this summer we’ll be doing the same with the Movie and Fuji sections of the book. Instructors who want their students to read that material are welcome to send them there, where the essays can be downloaded.

Octave’s hop: Andrew Sarris

La Règle du jeu (The Rules of the Game, 1939).

DB here:

The death of Andrew Sarris last week isn’t just a saddening moment for those of us who admire exhilarating film criticism. It also reminds us how much American culture can owe to a single person.

Everyone who writes about Sarris writes about how they came to know his work. It was that powerful, and if it hit you young, you were never the same. (You never hear about the sixty-year-old who suddenly becomes an auteurist.) The period of his greatest impact was the 1960s-1970s when, to borrow a phrase from Dave Kehr, movies mattered. But his influence has lingered, powerfully, a lot longer.

I think that the best way to honor Sarris is to take his ideas–not just his opinions, but his ideas–seriously, so that’s what I’ve tried to do in this tribute. First, though, some comments that are obligatory in any discussion of Sarris.

Obligatory autobiography 1

1963: When I was sixteen I wrote to various film magazines and asked for sample issues as a “prospective subscriber.” Surprisingly, several answered, and I amassed a few copies of Film Quarterly, Films and Filming, and Movie. No gift from the land of film journals was more propitious than that fateful issue 28 of Film Culture entitled “American Directors.” It was the first draft of what would become Sarris’ 1968 book, The American Cinema.

Issue 28 was a dangerous item to give a kid. It contained what Georgie Minafer calls “touchy chemicals.” At first I was baffled. There were those famous categories: How to distinguish “Lightly Likeable” from “Less Than Meets the Eye”? Who were Budd Boetticher, Tay Garnett, and John M. Stahl? What did it mean to say that Robert Montgomery “executed a charming champ-contre-champ joke in Once More, My Darling”? To me it was all Expressive Esoterica. Here was a cave of mysteries, but it hinted at treasures.

Sarris’s filmographies were packed with titles I’d never heard of. How could I catch up? Around 1955, the studios had begun selling their pre-1948 titles to local television stations. By the next year, people living in major cities could tune in five or six movies a day. At the forefront of TV sales was the financially precarious RKO, which sold over seven hundred titles to an outfit called C & C. C & C packaged the library as 16mm TV prints under the rubric of “Movietime.”

Sarris’s filmographies were packed with titles I’d never heard of. How could I catch up? Around 1955, the studios had begun selling their pre-1948 titles to local television stations. By the next year, people living in major cities could tune in five or six movies a day. At the forefront of TV sales was the financially precarious RKO, which sold over seven hundred titles to an outfit called C & C. C & C packaged the library as 16mm TV prints under the rubric of “Movietime.”

Auteurism owes a good deal to the 1950s-1960s equivalent of home video, the thousands of 16mm prints floating around local TV stations. In Manhattan, WOR-TV screened their films under the rubric “Million Dollar Movie.” The same film might run once or twice every night for a week (and twice or more on weekends). Without benefit of WOR or New York’s revival houses, I was still able to use Rochester television to sample some of the titles that Sarris had listed, especially those given in big caps. (Italicizing must-see items didn’t show up until the book version.) Sarris’s essay, “Citizen Kane: The American Baroque,” was published in Film Culture in 1956, the same year that the RKO library began to be syndicated and Kane was reissued in theatres around the country.

I did wind up subscribing to Film Culture. It was the least I could do to pay them back.

Obligatory autobiography 2

Fall 1965: At a state college up the Hudson, the English department hosted a debate on contemporary American movies. The adversaries were Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris, both just coming into the national spotlight. One freshman came early and sat with comic earnestness in the front row, a spot he would fetishize later.

Kael was witty and acerbic, tossing off judgments with a wave of her cigarette holder. The Cincinnati Kid was the best of the current crop; Jewison showed great promise. She was riding high because I Lost It at the Movies had come out that spring and was greeted with hosannas. The New Yorker review contrasted her with “the far-out Sarris.”

He didn’t look so far-out. In a crumpled suit, he was resolutely uncharismatic, looking mildly unhappy to be dragged blinking out of the Thalia and shipped upstate. He talked fast, interrupted himself, and, finding few recent movies to praise, celebrated Max Ophuls and Jean Renoir. He delivered enigmatic observations like, “All movies should probably be in color.”

At evening’s end, I knew which camp I belonged in. I got an appropriately nerdy autograph for my Film Culture issue: “Cinecerely yours, Andrew Sarris.” More important, I exulted in a sense that my almost grim obsession with movies had been validated. Not for some time would I realize that I had enlisted, to put it melodramatically, in a fight for American film culture. The battle lines were drawn more sharply in Manhattan than in Albany, but everywhere one thing was clear. Kael was clearly the standard bearer for them, and Sarris was ours.

Obligatory comparison: S vs. K

Who were the them? They were the hip intellectuals who enjoyed a night at the movies. At faculty parties throughout the 1970s I had to check myself when professors of lit or law asked me if I didn’t find Kael’s review that week intoxicating. And she writes so well! As chief New Yorker critic, Kael became the grand tastemaker, a person even filmmakers courted. But who would try to curry favor with the guy who wrote for the Village Voice? It reminds you of the joke about the starlet so dumb she slept with the screenwriter.

Of course like all acolytes we overplayed the differences. Both Kael and Sarris loved classic studio cinema, the performers and scripts as much as the directorial handling. Both critics bemoaned Soviet montage and what they saw as its descendant, the overbusy technique of the 1960s. Both deplored stylistic aggressiveness (the Tony Richardson Syndrome) and both idolized Renoir. Both loved lyricism.

According to us, though, Kael wrote for those who dug movies, while Sarris wrote for those who loved cinema—the medium itself, or rather an exalted idea of the medium’s potential, an ideal form of expression at once dramatic, poetic, pictorial, and musical. He saw each film as bearing witness to the promise of what cinema might be, and he looked in even the tawdriest products for something approximating his dreams. Despite his enthusiasms, he tried for detachment, viewing the latest movie from some unpredictable historical perspective.

Kael famously declared that she watched a new film only once, because that was the way her readers would consume it. But who, we thought, would want to write about a movie after seeing it only once? Mightn’t it reveal some strengths or weaknesses on a second viewing? If it was a good movie, who wouldn’t want to see it more than once? In that same freshman semester, when there were still first-run double features, I sat through The Glory Guys twice in order to watch Help! three times. And that wasn’t even a particularly good movie.

Kael pounced on faults, Sarris savored beauties. Kael made each weak film seem like a blow to her intelligence. Sarris, although he could be harsh, tended to forgive. He taught that it was better to leave a door open than to write someone off—even Bergman, whom some of us would never learn to like until Persona, some not until Fanny and Alexander. Sarris subordinated his personality to that of the movie and its director, which made him seem less fiery than his uptown counterpart; but his attitude suited our own somewhat adolescent amorphousness of character. The arrogant certainty of our tastes was, paradoxically, born of a passionate humility, a sense of serving wise masters named Dreyer, Murnau, Mizoguchi.

Rethinking film history

Sarris is known primarily as the man who gave us the American version of auteurism, or what he called “the auteur theory.” It wasn’t a theory of cinema as such, but rather a heuristic approach to criticism: tips on what to think about and look for when you wanted to plumb a movie’s artistry. But initially, auteurism claimed to be a theory of something else. The opening chapter of The American Cinema is called “Toward a Theory of Film History.”

In Sarris’s day, most people writing about the history of film as an art accepted a notion of technical progress. According to this view, filmmakers became significant by contributing toward the development of the medium. Editing emerged through the efforts of Méliès, Porter, and Griffith, followed by the Russian Montage directors. Various national schools revealed more possibilities of the medium: fantasy and abstraction with the German Expressionists, derangement of sense with the Surrealists.

When sound arrived, a few directors (Clair, Mamoulian, Hitchcock) explored the stylized possibilities of that new technology. But many historians, considering that cinema was inherently a visual medium, declared sound an unwanted intrusion. Clearly, the great days of cinematic artistry were over. Most synoptic histories of the period fell silent about the evolution of technique after the 1920s and concentrate on the emergence of certain genres, such as the musical and the film of social comment.

Even André Bazin could be said to accept the premises of step-by-step artistic progress. Bazin showed that sound cinema wasn’t a dead end, that new artistic possibilities were exploited in the 1930s and 1940s. These were mostly creative alternatives to editing-based technique: the long take, extended camera movement, deep-space staging, and deep-focus cinematography. Bazin claimed that these techniques were most fully on display in the works of Renoir, Wyler, Welles, and some Neorealists.

Sarris was deeply influenced by Bazin’s ideas, but he didn’t accept the conception of film history as an accumulated technical evolution. Sarris called this the “pyramid fallacy,” with each filmmaker adding his slab to the rising and narrowing edifice of cinema. Instead, he proposed thinking of film history as an inverted pyramid, “opening outward to accommodate the unpredictable range and diversity of individual directors.”

In practice this demands that the historian survey entire careers, especially the works of ripe old age. It demands that the historian plot directors’ creative trajectories as paralleling and intersecting and overlapping—perhaps coalescing into broader trends, perhaps creating dead ends. The cinematic universe expands with each new film made, every old film rediscovered or simply re-seen. Auteurism “places a premium on having seen every work by a director who is deemed worthy of a study in depth; and by the time all the cross-references have been pursued in every possible direction auteurism seems to insist that every film ever made is relevant to the inquiry.”

Film history becomes less a linear progress toward something than a vast network of affinities and differences. This idea naturally led Sarris the writer not to the mammoth survey but to multifaceted essay collections. His big book, “You Ain’t Heard Nothin’ Yet,” looks like a panoramic history but is in fact a free-range miscellany, a sort of unbuttoned late-career redo of that Film Culture issue..

You can argue that Sarris was proposing a non-historical history, one that dispenses with concepts of influence and cause and that pulverizes any coherent narrative. That seems to me a valid objection. Despite its claim to be a theory of film history, Sarris’s auteurism strikes me as a historically informed approach to film criticism. The ultimate aim isn’t a convincing historical narrative but a compelling aesthetic judgment. Sarris’s idea of expanding filiation, infinite comparison and contrast, allows him to pursue what matters: evaluation.

In this respect at least, he’s agreeing with his predecessors, the writers who saw history as linear progress. But his criteria of value are different. For the traditionalists, the filmmakers who grasped the next step that the medium should take in its creative development become the best. For Sarris, the best filmmakers used the resources at their disposal to create valuable works that also displayed a distinct conception of human life. “Griffith, Murnau, and Eisenstein had different visions of the world, and their technical ‘contributions’ can never be divorced from their personalities.” Innovation was secondary to expression, and expression could best be gauged by tracking the wayward currents of the history of film style.

Auteur, yes; but of what?

New York Film Festival 1966: Pier Paolo Pasolini, translator, Andrew Sarris, and Agnes Varda. Photo by Elliott Landy. From Film Culture no. 42 (Fall 1966).

The auteur “theory” creates a decentralized and dispersed conception of film history—not a tree with a solid trunk and clear-cut branches but a bristling, tangled bush. The historian will dissolve big changes and broad trends into the doings of particular film artists. Who are these artists? Well, obviously, directors.

This move shouldn’t have been controversial. Critics had long assigned primary creative responsibility to directors. In the 1910s Louis Delluc heaped praise on DeMille and Sjöström, while Griffith was acknowledged around the world as a great innovator. Later von Stroheim, von Sternberg, Eisenstein, Pabst, Clair, Welles, Hitchcock, Maya Deren, and many other filmmakers were recognized as the artistic authority behind their work. In the early 1950s, foreign-language filmmakers such as Kurosawa and Bergman were identified (and even promoted by their distributors) as all-powerful creators saying something through their art.

Sarris’s real innovation was, along with the critics around Cahiers du cinéma and Movie, to transfer the idea of the expressive film artist from the headier regions of art cinema to the jostling, compromised world of Hollywood. There were obvious objections.

*Filmmaking is a “collaborative” activity, so you can’t attribute the final work to a single hand.

Yet in the collaborative medium of opera we speak of a Zeffirelli production as opposed to a Peter Sellars one. Why can’t a film director be a synthesizing artist orchestrating the contributions of many other artists?

*But in opera and other theatre forms, you have a preexisting text, the script or libretto or score. Why isn’t the screenwriter the artist, as Shakespeare or Verdi is?

Because theatrical texts are designed to be instantiated on different occasions, while film scripts are written to be produced only once. The film’s final form includes elements of the script, but that final form, being cinematic, can’t be uniquely specified in verbal language. As we all realize, give the same screenplay to six filmmakers, and you get six different and equally free-standing films.

*Popular film can’t be compared to high art. Artistry demands control, and the novelist, the painter, and even the opera director will exercise complete control over the final work. A Bergman or Antonioni has the cultural clout to dictate every aesthetic effect, but the Hollywood filmmaker works as part of a larger process controlled by others. He is handed a script and shoots it, and not necessarily all of it; second-unit and visual effects staff have their input too. The producer may demand more close-ups. In the classic studio system, the director wouldn’t typically get final cut; the producer would shape the released film. All these conditions constitute barriers to artistic expression. The auteur theory, when applied to Hollywood, is deeply inappropriate.

One answer to this objection is that many directors, including some of the best ones, did have a good deal of control over their work: Hitchcock, Hawks, and others were their own producers and worked on their scripts and oversaw their post-production. Moreover, a director can control choices down the line in sneaky ways, as when Ford shot his films so that they could be assembled in only one way.

Sarris advanced another reply to the control objection. If it owed something to the Cahiers young critics, he articulated and practiced it more keenly than they. He proposed a critical method: Take as many films signed by the director as you can find. Attend to the way they exercise their craft, the way they tell their stories and convey their meanings. Seek out an expressive core that seems distinctive, even unique.

Most directors’ collected works won’t yield this. “Not all directors are auteurs. Indeed, most directors are virtually anonymous.” Only the best directors will display a distinct expressive quality. Hawks and Hitchcock evoke radically different worlds of action and feeling, just as Mozart and Rembrandt can.

Fifteen years after his initial statement on the matter, “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962,” Sarris suggested that the elusive concept of personality was not to be derived from the director’s biography. “I was never all that interested in the clinical ‘personalities’ of directors. . . . A director’s formal utterances (his films) tell us more about his artistic personality than do his informal utterances (his conversation).”

For example, we understand John Ford’s respect for what Sarris calls “codes of conduct” not through the old curmudgeon’s interviews but by confronting the tangible texture of the movies. One of Sarris’s favorite examples occurs in The Searchers. Drinking his coffee, the Ward Bond character glances toward the wife of the household. Then his point of view reveals her stroking the uniform of her husband’s brother, played by John Wayne.

Cut back to Bond as the wife and her brother-in-law meet for a tender farewell. Bond stares off into space, chewing.

“Nothing on earth,” writes Sarris, “would ever force this man to reveal what he had seen. There is a deep, subtle chivalry at work here, and in most of Ford’s films, but it is never obtrusive enough to interfere with the flow of the narrative.” The economy is part of the point. “If it had taken him any longer than three shots and a few seconds to establish this insight into the Bond character, the point would not be worth making.”

In the Hollywood studio context, there was something heroic about the rare director who could surmount all the pressures, filter out all the noise, and shape the impact of his work. “The auteur theory values the personality of the director precisely because of the barriers to its expression.” Like a great Renaissance painter paid by a pope or a duke and pledged to illustrate well-known stories, the Hollywood director working for a studio could occasionally conjure up something powerful and distinctive.

Auteurism, Sarris claimed, is our straightest road to determining a film’s value. The great films, by and large, will be those that evoke distinctive directorial sensibilities. But “by and large” allows for the possibility of excellent movies that we can attribute to other forces—script, stars, source material, the happy intersection of talents. Casablanca, writes Sarris, “is the most decisive exception to the auteur theory.” Sarris loved movies more than he loved his theories.

Compare, contrast, repeat

Sarris’s breakthrough essay, “Citizen Kane: The American Baroque,” appeared in Film Culture during the 1956 revivals of the film. This detailed explication, published when Sarris was twenty-eight, betrays his grad-school training at a period when the New Criticism reigned. In a single stroke, he pioneered the sort of close reading that would become central to Anglo-American academic film criticism.

I can’t recall any later Sarris essay offering such an intensive analysis of a single film. As he developed his historically-guided critical appraisals, he favored synoptic appreciations of directorial careers. These became the occasions for him to point out interacting directorial personalities that comprise that vast network of cinema.

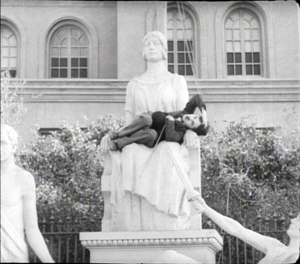

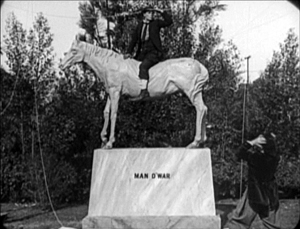

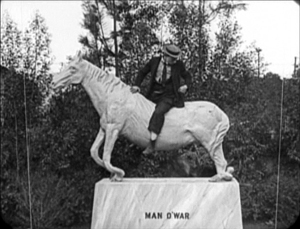

Instead of macro-analysis, Sarris embraced a strategy of “drilling down,” we’d now say, to a single revelatory passage. The chief tactic is comparison, often involving two directors faced with a comparable situation. Both City Lights and The Goat show a protagonist hiding on a statue about to be unveiled. Chaplin seizes the chance to deflate the ceremony.

But Keaton, says Sarris, is less interested in satire; he is “a pessimist in perpetual motion.” In The Goat, “Keaton remains mounted on the clay horse until it begins to sag and crumple under his weight, and the sculptor, a bearded nincompoop in a beret, proceeds to break down and weep.”

“Keaton’s expression here,” Sarris claims, “is mercilessly pragmatic. What good is a clay horse (art?) if you can’t mount it to your own advantage? There is something unabashedly ruthless about Keaton’s comedy, which chills his humor.” This was the period when critics, having just rediscovered Keaton’s films, claimed him as a “metaphysician.” Sarris likened him to Beckett.

Sarris wasn’t alone in turning to detailed commentary at the period; we had Dwight Macdonald’s appreciative 1964 essay on 8 ½ and John Simon’s book-length study of Bergman (1973). But Sarris got there early with the Kane piece, and throughout his career he used analysis to pinpoint authorial personality. Attention to nuanced differences allowed him to create a kind of connoisseurship.

The ultimate expression of this connoisseurship emerges in his concern for privileged moments. A critic has to be alert for shots or gestures or lines of dialogue that encapsulate the emotional tenor of a film and a director’s sensibility. Sarris’ example is a moment in La règle du jeu:

Renoir gallops up the stairs, stops in hoplike uncertainty when his name is called by a coquettish maid, and then, with marvelous post-reflex continuity, resumes his bearishly shambling journey to the heroine’s boudoir.

If I could describe the musical grace note of that momentary suspension, and I can’t, I might be able to provide a more precise definition of the auteur theory. As it is, all I can do is point at the specific beauties of interior meaning on the screen and later catalogue the moments of recognition.

No director but Renoir, Sarris suggests, would have Octave break the scene’s rhythm in exactly this way–and in a manner, Sarris’s bear-metaphor hints, that anticipates Octave’s costume for the climactic party in the chateau. The nonchalant, slightly awkward interruption epitomizes Renoir’s entire style of filmmaking, which has room for casual deflections from neat plotting and groomed performances. The critic’s words can’t wholly capture the force of Octave’s hop, and its resonance for Renoir’s film and his oeuvre. It is, says Sarris, “imbedded in the stuff of cinema.”

Both cinephiles and ordinary viewers are seized by luminous instants that change our skin temperature. We come out of a film satisfied if a few epiphanies have flashed upon us. The critic can signal them but not explain them fully. Interior meaning is the product of craft and personality, but it can’t be reduced to them. It creates a tingling, fugitive beauty that is unique to cinema.

Everyone has his or her own Sarris. The foregoing offers merely bits of mine, and they’re largely academic in slant. That’s because I think that Sarris changed, among other things, the way film history and criticism were taught in American universities. While Kael influenced film journalism, particularly in the upscale markets, Sarris’s legacy is best seen in cinephile criticism (Film Comment, Film Quarterly et al.) and academic film studies. Some Paulettes went to work for the New York cultural weeklies, high and low. Many people who were Sarrisites to some degree (Jeanine Basinger, James Naremore, John Belton, William Paul, Elisabeth Weis, Chuck Wolfe, Mark Langer, Robert Lang, et al.) became professors. Kael’s followers turned out essays, but Sarrisites like Todd McCarthy and Joseph McBride wrote books based firmly in research. Sarris’s version of auteurism has been reworked, in plenty of intriguing ways, in directorial monographs from university presses. He once remarked ruefully that he was an academic among journalists and a journalist among academics, but he managed to bridge the gap adroitly.

Sarris was too far-out for the New Yorker in 1965, and probably for the New Yorker of today. But history, and not just the history of movies, was on his side.

Sarris’ life and death have called forth many eloquent tributes. Among the best are Kent Jones’ career overview, Richard Corliss’s moving memoir, and Jim Emerson’s calm discussion of the excesses of the Sarris vs. Kael dichotomy. See also Ben Kenigsberg’s memories of Sarris’s teaching style.

My quotations are taken from Film Culture no. 28 (Spring 1963), The American Cinema (Dutton, 1968), Confessions of a Cultist: On the Cinema, 1955/1969 (Simon and Schuster, 1971), The Primal Screen (Simon & Schuster, 1973), and The John Ford Movie Mystery (Secker & Warburg, 1976). Thanks also to email conversations with John Belton of Rutgers and Dennis Bingham of Indiana University.

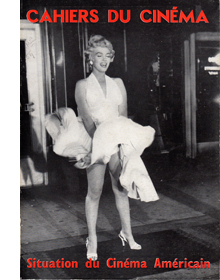

When I received Film Culture no. 28, I didn’t know that it represented a continuation of a Cahiers du cinéma tradition. In December 1955, the journal had published a special issue, “Situation du Cinéma Américain” (no. 54). It included not only critical essays but a “dictionary” of contemporary American directors: small-print filmographies followed by a paragraph of lapidary commentary. (“Lang’s work is founded on a metaphysics of architecture.”) Later issues devoted “dictionaries” to current French cinema (no. 71, May 1957), the Nouvelle Vague (no. 138, December 1962), and more recent American cinema (no. 150-151, December 1963-January 1964). In his American Cinema project, Sarris altered the format significantly by expanding the commentaries into essays and then grouping directors within sharp-edged, highly memorable categories of value. In turn, Sarris’s catalogue seems to have been the model for Martin Scorsese’s “Personal Journey through American Movies.” In the same tradition is Jean-Pierre Coursodon and Pierre Sauvage’s too-little-known American Directors (1983).