Archive for the 'Film theory: Cognitivism' Category

Movies by the numbers

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022). Publicity still.

DB here:

Cinema, Truffaut pointed out, shows us beautiful people who always find the perfect parking space. Mainstream movies cater to us through their stories and subjects, protagonists and plots. But they have also been engineered for smooth pickup. Their use of film technique is calculated to guide us through the action and shape our emotional response to it.

How this engineering works has fascinated film psychologists for decades. Over a century ago, Hugo Münsterberg proposed that the emerging techniques of the 1915 feature film made manifest the workings of the human mind. In ordinary life, we make sense of our surroundings by voluntarily shifting our attention, often in scattershot ways. But the filmmaker, through movement, editing, and close framings, creates a concentrated flow of information designed precisely for our pickup. Even memory and imagination, Münsterberg argued, find their cinematic correlatives in flashbacks and dream sequences. In cinema, the outer world has lost its weight and “has been clothed in the forms of our own consciousness.”

Over the decades, many psychologists have considered how the film medium has fitted itself to our perceptual and cognitive capacities. Julian Hochberg studied how the flow of shots creates expectations that guide our understanding of cinematic space. Under the influence of J. J. Gibson’s ecological theory of perception, Joseph Anderson reviewed the research that supported the idea that films feed on both strengths and shortcomings of the sensory systems we’ve evolved to act in the environment. In more recent years, Jeff Zacks, Joe Magliano, and other visual researchers, have gone on to show how particular techniques exploit perceptual shortcuts (as in Dan Levin’s work on change blindness and continuity editing errors https://vimeo.com/81039224). Outside the psychologists’ community, writers on film aesthetics have fielded similar arguments. An influential example is Noël Carroll’s essay “The Power of Movies.”

Over the decades, many psychologists have considered how the film medium has fitted itself to our perceptual and cognitive capacities. Julian Hochberg studied how the flow of shots creates expectations that guide our understanding of cinematic space. Under the influence of J. J. Gibson’s ecological theory of perception, Joseph Anderson reviewed the research that supported the idea that films feed on both strengths and shortcomings of the sensory systems we’ve evolved to act in the environment. In more recent years, Jeff Zacks, Joe Magliano, and other visual researchers, have gone on to show how particular techniques exploit perceptual shortcuts (as in Dan Levin’s work on change blindness and continuity editing errors https://vimeo.com/81039224). Outside the psychologists’ community, writers on film aesthetics have fielded similar arguments. An influential example is Noël Carroll’s essay “The Power of Movies.”

James Cutting’s Movies on Our Minds: The Evolution of Cinematic Engagement, itself the fruit of many years of intensive studies, builds on these achievements while taking wholly original perspectives as well. Comprehensive and detailed, it is simply the most complete and challenging psychological account of film art yet offered. I can’t do justice to its range and nuance here. Consider what follows as an invitation to you to read this bold book.

Laws of large numbers

The Martian (2015). Publicity still.

Cutting’s initial question is “Why are popular movies so engaging?” He characterizes this engagement—a more gripping sort than we experience with encountering plays or novels—as involving four conditions: sustained attention, narrative understanding, emotional commitment, and “presence,” a sense that we are on the scene in the story’s realm. Different areas of psychology can offer descriptions and explanations of what’s going on in each of these dimensions of engagement.

His prototype of popular cinema is the Hollywood feature film—a reasonable choice, given its massive success around the world. The period he considers runs chiefly from 1920 to 2020. He has run experimental studies with viewers, but the bulk of his work consists of scrutinizing a large body of films. Depending on the question he’s posing, he employs samples of various sizes, the largest including up to 295 movies, the smallest about two dozen. Although he insists he’s not concerned with artistic value, most are films that achieved some recognition as worthwhile. He and his research team have coded the films in their sample according to the categories he’s constructed, and sometimes that process has entailed coding every frame of a movie.

Like most researchers in this tradition, Cutting picks out devices of style and narrative and seeks to show how each one works in relation to our mind. His list is far broader than that offered by most of his predecessors; he considers virtually every film technique noted by critics. (I think he pins down most of those we survey in Film Art.) In some cases he has refined standard categories, such as suggesting varieties of reaction shot.

Starting with properties of the image (tonality, lens adjustments, mise-en-scene, framing, and scale of projection), he moves to editing strategies, the soundtrack, and then to matters of narrative construction. For each one he marshals statistical evidence of the dominant usage we find in popular films. For example, contemporary films average about 1.3 people onscreen at all times, while in the 1940s and 1950s, that average was about 2.5. Across his entire sample, almost two-thirds of all shots show conversations—the backbone of cinematic narrative. (So much for critics who complain that modern movies are overbusy with physical action.) And people are central: 90% of all shots show the head of one or more character.

Some of these findings might appear to be simply confirming what we know intuitively. But Big Data reveal patterns that neither filmmakers nor audiences have acknowledged. Granted, we’ve all assumed that reaction shots are important in cueing the audience how to respond. Cutting argues that despite their comparative rarity (about 15% of a film’s total) they are central to our overall experience: they are “popular movies’ most important narrational device.” They invite the audience to engage with the character’s emotions, and they encourage us to predict what will happen next.

This last role emerges in what Cutting calls the “cryptic reaction shot,” in which the response is ambivalent. Such shots show a moment when a character doesn’t speak in a conversation (for example, Jim’s reactions in my Mission: Impossible sequence). Filmmakers seem to have learned that

these shots are an excellent way to hook the viewer into guessing what the character is thinking—what the character might have said and didn’t. They also serve as fodder for predicting what the character will do next (174-175).

Cryptic reactions gather special power at the scene’s end. Whereas films from the 1940s and 1950s ended their scenes with such shots about 20% of the time, today’s films tend to end conversations with them almost two-thirds of the time. Since reading Cutting’s book I’ve noticed how common this scene-ending reaction shot is in movies (TV shows too). It’s a storytelling tactic that nobody, as far as I know, had previously spotted.

Similarly, Cutting tests Kristin’s model of feature films’ prototypical four-part structure. He finds it mostly valid, both in terms of data clustering (movement, shot lengths, etc.) and viewers’ intuitions about segmentation. But who would have expected what he found about what screenwriters call the “darkest moment”? Using measures of luminance, he finds that “this point literally is, on average, the darkest part of a movie segment” (285).

Cutting has found resourceful ways to turn factors we might think of as purely qualitative into parameters that can be counted and compared. To gauge narrative complexity, he enumerates the number of flashbacks, the amount of embedding (stories within stories), and particularly the number of “narrational shifts” in films. Again, there is a change across history.

Movies jump around among locations, characters, and time frames considerably more often than they used to. . . . Scenes and subscenes have gotten shorter. In 1940, they averaged about a minute and a half in duration, but by 2010 they were only about 30 seconds long (271-272).

His illustrative example is the climax of The Martian, where in four minutes and 35 shifts, the narration cuts together seven locations, all with different characters. Something similar goes on in the motorcycle chase of Mission: Impossible II and the final seventy minutes of Inception.

These examples show that Cutting is going far beyond simply tagging regularities in an atomistic fashion. Throughout, he is proposing that these patterns perform functions. For the filmmakers, they are efforts to achieve immediate and particular story effects, highlighting this or that piece of information. Showing few people in a shot help us concentrate on the most important ones. Conversations are the most efficient way to present goals, conflicts, and character relationships. Editing among several lines of action at a climax builds suspense. He suggests that because viewer mood is correlated with luminance, the darkest moment is triggering stronger emotional commitment.

But Cutting sees broader functions at work underneath filmmakers’ local intentions. Movies’ preferred techniques, the most common items on the menu, smoothly fit our predispositions—our tendencies to look at certain things and not others, to respond empathically to human action, to fit plots together coherently. Filmmakers have intuitively converged on powerful ways to make mainstream movies fit humans’ “ecological niche.”

And those movies have, across a century, found ways to snuggle into that niche ever more firmly. As we have learned the skills of following movie stories, filmmakers have pressed us to go further, stretching our sensory capacities, demanding faster and subtler pickup of information. Cutting’s numbers lead us to a conception of film history, the “evolution of cinematic engagement” promised in his subtitle.

Film history without names

Suspense (Weber and Smalley, 1913).

Central to Cutting’s psychological tradition is the idea that engagement depends minimally on controlling and sustaining attention. The techniques itemized almost invariably function to guide the viewer to see (or hear) the most important information. Filmmakers discovered that you can intensify attention by cooperation among the cues. Given that humans, especially faces, carry high information in a scene, you can use lighting, centered position, frontal views, close framings, figure movement, and other features of a shot to reinforce the central role of the humans that propel the narrative. When the key information doesn’t involve faces or gestures, you can give objects the same starring role.

Movies on Our Minds is very thorough in showing through statistical evidence that all these techniques and more combine to facilitate our attention. As an effort of will you can focus your attention on a lampshade, but it won’t yield much. The line of least resistance is to go with what all the cues are driving you to. But the statistical evidence also points to changes across history. What’s going on here?

Most basically, speedup. Cutting asked undergraduate students to go through films twice, once for basic enjoyment and then frame by frame, recording the frame number at the beginning and ending of each shot. He found that by and large the students enjoyed the older films, but some complained that these older movies were slower than what they ordinarily watched.

This impression accords with both folk wisdom and film research. Most viewers today note that movies feel very fast-moving, compared with older films. There’s also a considerable body of research indicating that cutting rates have accelerated since at least the 1960s. More loosely, I think most people think that story information is given more swiftly in modern movies; our films feel less redundant than older ones. Exposition can be very clipped. Abrupt changes from scene to scene are accentuated by the absence of “lingering” punctuation by fade-outs or dissolves. Indeed, one scene is scarcely over before we hear dialogue or sound effects from the next one. Characters’ motives aren’t always spelled out in dialogue but are evoked by enigmatic images or evocative sound. The Bourne Identity attracted notice not just for its fragmentary editing but also for its blink-and-you’ll-miss-them “threats on the horizon”—virtually glimpses of what earlier films would have dwelled on more. From this angle, Everything Everywhere All at Once represents a kind of cinema that grandpa, and maybe dad, would find hard to follow. (Actually, I’m told that some audiences today have trouble too.)

In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I suggested some causal factors shaping speedup, including various effects of television. Cutting grants that these may be in play, but just as he looks for an underlying pattern of functional factors in his ecology of the spectator, he posits a broad process of cinematic evolution similar to that in biology.

Look at film history simply as succession of movies. From a welter of competing alternatives, some techniques are selected and prove robust. They are replicated, modified in relation to the changing milieu. Others fail. For instance, the split-screen telephone shot of early cinema, as in the above frame from Suspense, became “a failed mutation” when shot/ reverse-shot editing for phone calls became dominant. As the main line of descent has strengthened, variation has come down to “selected tweaks” like eyelights and Steadicam movement.

Within this framework, filmmakers and audiences participate in a give-and-take.Through trial and error, early filmmakers collectively found ways to make films mesh with our perceptual proclivities. As viewers became more skilled in following a movie’s lead, there was pressure on filmmakers to go further and make more demands. If attention could be maintained, then shots could be shorter, scenes could move faster, redundancy could be cut back, complexity could be increased.

Viewers responded positively, embracing the new challenges of quicker pickup. As viewers became more adept, filmmakers could push ahead boldly, toward films like Memento and Primer. The most successful films, often financially rewarding ones like The Martian and Inception, suggest that filmmakers have continued to fit their boundary-pushing impulses to popular abilities.

Which means that audiences have adapted to these demands. But this isn’t adaptation in the strong Darwinian sense. With respect to his students’ reactions, Cutting writes:

I think . . . that the eye of a 20-year-old in the 2010s was faster at picking up visual information than the eye of a 20-year-old in the 1940s. This is not biological evolution. This is cultural education, however incidental it might be.

This process of cultural education, he suggests can be understood using Michael Baxandall’s concept of the “period eye.” Baxandall studied Italian fifteenth-century painting and posited that an adult in that era saw (in some sense) differently than we do today. Granted, people have a common set of perceptual mechanisms, but cultural differences intervene. Baxandall traced some socially-grounded skills that spectators could apply to paintings. In parallel fashion, given the rapidity of cultural change in the twentieth century, young people now may have gained an informal visual education, a training of the modern eye in the conventions of media.

Cutting insists that he isn’t suggesting that our attention spans have recently decreased, as many maintain. Instead, the idea of a period eye centers on

the growth and improvement of visual strategies as shaped by culture. If this idea is correct, then contemporary undergraduates have reason to complain about movies from the 1940s and 1950s that I asked them to watch.

By this account, film teachers have to recognize that their students, for whom any film before 2000 is an old movie, are possessed of a constantly changing “period eye.”

Failed mutations, or revision and revival?

City of Sadness (Hou, 1989).

I do have some minor reservations, which I’ll introduce briefly.

First, I don’t think that Baxandall’s idea of a period eye is a good fit for the dynamic that Cutting has identified. Baxandall’s concern is with a narrow sector of the fifteenth-century public: “the cultivated beholder” whom “the painter catered for.”

One is talking not about all fifteenth-century people, but about those whose response to works of art was important to the artist—the patronizing class, one might say. In effect this means a rather small proportion of the population: mercantile and professional men, members of confraternities or as individuals, princes and their courtiers, the senior members of religious houses. The peasants and the urban poor play a very small part in the Renaissance culture that most interests us now.

Ordinary viewers could recognize Jesus and Mary, the Annunciation or the Crucifixion, but for Baxandall the “period eye” involved a specific skill set. This was derived from such domains as business, surveying, ready reckoning, and a widespread artistic concepts like “foreshortening” or “stylistic ease.” The study of geometry prepared the perceiver to appreciate the virtuosity of perspective or proportion, but the untutored viewer could only marvel at the naturalness of the illusion.

It seems to me that Cutting’s 20-year-olds are not prepared perceivers in Baxandall’s sense. True, they may be alert to faulty CGI or a lame joke, but the whole point of focusing on mass-entertainment movies is that they engage multitudes, not coteries. The techniques Cutting explores are immediately grasped by nearly everybody, and no esoteric skills are necessary to feel their impact. Baxandall’s viewer is able to appreciate a painter’s rendition of bulk because he’s used to estimating a barrel’s capacity, but all Cutting’s viewer needs to get everything is just to pay attention.

Because the skills of following modern movies are so widespread, I wonder if Cutting’s case better fits the explorations of Heinrich Wöfflin, who flirted with the idea that “seeing as such has its own history, and uncovering these ‘optical strata’ has to be considered the most elementary task of art history.” Throughout his late career Wöfflin struggled to make the “history of vision” thesis intelligible. At times he implied that everyone in a given era “saw” in a way different from people in other eras. At other times he proposed that of course everyone sees the same thing but “imagination” or “the spirit” of the period and place shape how we understand what we see. This is murky water, and you can sense my skepticism about it. I don’t see how we could give the “period eye” for cinema much oomph on this front, but I think we might salvage Cutting’s central point. See below.

Secondly, by concentrating on mass-market cinema, “the movies,” and suggesting they fit our evolved capacities, we can easily overlook the alternatives. Obvious examples are the earliest cinema, which did involve some precise perceptual appeals (centering, frontality, selective lighting, emphasis through foreground/background relations) but not all the ones associated with editing. Given that tableau cinema had a longish ride (1895-1920 or so), it’s not inconceivable that, had circumstances been different, we would still have a cinema of distant framings and static long takes.

Cutting is aware of this. Rewind the tape of history, he says, and eliminate factors like World War I, and things could have turned out differently. But where would a long-running tableau cinema leave the story of cinema’s dynamic of natural selection? Would we have simply a steady state, without the acceleration of the last sixty years? Or would we look within the long history of tableau cinema for mutations and failed adaptations?

We have contemporary examples, in what has come to be called “slow cinema.” Hou Hsiao-hsien, Theo Angelopoulos, and other modern filmmakers have exploited the static long take for particular aesthetic effects. In another universe, they are the “movies” that hordes flock to see. Tableau cinema seems to me not a failed mutation, replaced by a style that more tightly meshed with spectators’ proclivities; it was an aesthetic resource that could be revived for new purposes. On a smaller scale, something like this happened with split-screen phone calls (as in Down with Love and The Shallows).

As the other arts show us, the past is available for re-use in fresh ways. Maybe nothing really goes away.

Which brings me to my last point. Baxandall’s emphasis on skills reminds us that we can acquire a new “eye” for appreciating films outside the mainstream. Cutting’s 20-somethings can learn to appreciate and even enjoy films that might strike them as slow. We call this the education of taste.

My inclination is to see the contemporary embrace of speedup as based in filmmakers’ and viewers’ more or less unthinking choices about taste. Indeed, Baxandall suggests that the period eye is a matter of “cognitive style,” a set of skills one person may have and another may lack.

There is a distinction to be made between the general run of visual skills and a preferred class of skills specially relevant to the perception of works of art. The skills we are most aware of are not the ones we have absorbed like everyone else in infancy, but those we have learned formally, with conscious effort: those which we have been taught.

Once the skills have been taught, we can exercise them for pleasure.

If a painting gives us opportunity for exercising a valued skill and rewards our virtuosity with a sense of worthwhile insight about that painting’s organization, we tend to enjoy it: it is to our taste.

I’d suggest that we have “overlearned” the skills solicited by mainstream movies and made them the automatic default for our taste. But we can also learn the skills for appreciating 1910s tableau cinema or City of Sadness. As we do so, we find we have cultivated a new dimension of our tastes. From this standpoint, the sensitive appreciators of slow cinema are far more like Baxandall’s educated Renaissance beholders than are the Hollywood mass audience. Perhaps to enjoy Feuillade or Hou today is to possess a genuine “period eye.”

None of this undercuts Cutting’s findings. But given the variety of options available, I’d argue that what the history of cinema reveals, among many other things, is a history of styles—some of which are facile to pick up, for reasons Cutting and his tradition indicate, and others which require effort and training and an open mind. Not clear-cut evolution, then, but just the blooming plurality we find in all the arts, with some styles becoming dominant and normative and others becoming rarefied . . . until artists start to make them mainstream. And the whole ensemble can be mixed and remixed in unpredictable ways.

There’s far too much in Movies on Our Minds to summarize here. It’s a feast of ideas and information, presented in lively prose. (The studies that the book rests upon are far more dependent upon statistics and graphs.) I should disclose that I read the book in manuscript and wrote a blurb for it. Consider this entry, then, as born of a strong admiration for James’s project.

Cutting’s book rests on years of intensive studies. Go to his website for a complete list. Most recently, he has traced a rich array of phone-call regularities across a hundred years. He has been a recurring player on this blog, notably here and here. James and I spent a lively week watching 1910s films at the Library of Congress, with results recorded here and here. The last link also provides more examples of revived “defunct” devices.

The tradition of film-psychological research I rehearse includes Hugo Münsterberg, The Film: A Psychological Study in Hugo Munsterberg on Film: The Photoplay: A Psychological Study and Other Writings, ed. Allan Langdale (Routledge, 2001; orig. 1916); In the Mind’s Eye: Julian Hochberg on the Perception of Pictures, Films, and the World, ed. Mary A. Peterson, Barbara Gillam, H. A. Sedgwick (New York: Oxford, 2007); Joseph D. Anderson, The Reality of Illusion: An Ecological Approach to Cognitive Film Theory (Southern Illinois University Press, 1996); Jeffrey Zacks, Flicker: Your Brain on Movies (Oxford, 2014). Noël Carroll’s essay “The Power of Movies” is included in his collection Theorizing the Moving Image (Cambridge, 1996).

Michael Baxandall’s most celebrated work is Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy (Oxford, 1972); citations come from pages 29-29. My mention of Wölfflin relies on Principles of Art History: The Problem of the Early Development of Style in Early Modern Art, trans. Jonathan Blower (Getty Research Institute, 2015). My citation comes from p. 93.

One reference point for Cutting’s work is a book Kristin and I wrote with Janet Staiger, The Classical Hollywood Cinema, discussed here. See also Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood, which elaborates the argument for the four-part model, and my books On the History of Film Style and The Way Hollywood Tells It, along with the web video “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.”

Bye Bye Birdie (1963).

Vancouver envoi: What happens in movies happens between your ears

Summer 85 (2020).

DB here:

One of the nicest things anybody ever said to me came from Jacques Aumont, the distinguished French film scholar. He was visiting us in the early 1980s and I showed him a book manuscript I had just sent to the publisher. He read the first three chapters and said, “You remind us of something important. The spectator is thinking.” The book eventually came out as Narration in the Fiction Film.

In emphasizing that the spectator thinks, at least a little, I was driven to pay special attention to openings. The opening is where a film sets up information about its story world, about the action that will take place in it. We usually call this exposition. But a film also attunes us to the how as well as the what: how the story will be told. Exposition, in other words, includes introducing us to the characters and their situation but also to the ways we’ll learn about them. In the book I called the latter the “intrinsic norms” of narration.

But exposition isn’t simply a part of the plot, a chunk of opening material we need to digest. Exposition, the narrative theorist Meir Sternberg shows, is a process. In revealing what we call “backstory,” circumstances that predate the first scenes we see, exposition can go on throughout a film. (Kristin talks about this in her entry on Inception, and in revised form in our Nolan book.) So it turns out that the spectator has to keep thinking, keep reevaluating what’s being told about the story world and the way the story is told.

Three films showcased at the Vancouver International Film Festival set me thinking about these matters. Two depended on surprises, and these stemmed from the way exposition was handled. The third had very sparse exposition, asking us to gradually fill in story background through drifts and whiffs of information. In all cases, our enjoyment depends on thinking.

Surprise!

Bettina Oberli’s My Wonderful Wanda updates the ingredients of classic bourgeois comedy for the modern world of migratory caregivers. Josef and Elsa Wegmeister-Gloor oversee their pampered and confused son and daughter. Into the household comes a servant who is exploited for sexual favors by the old man. Wanda, the nurse brought in from Poland, is today’s equivalent of the chambermaid lusted after by both father and son.

As in most domestic comedies of class relations, Wanda the worker is no fool. Her duties help support her father, mother, and sons back home, and she proves herself a shrewd negotiator from the start. When Elsa asks her to perform extra chores, she demands more money. And when Elsa’s stroke-felled husband is willing to pay for sex, she agrees. Their secret bargain will, in good farce fashion, come to light in the most embarrassing way possible.

I went into the film knowing much less of the plot than I’ve just told you, so I want to keep back the rest. (Alas, the trailer overshares.) I was able to appreciate the way that Oberli’s tight script kept the surprises coming. Her script finds an admirable balance between clear structure and unpredictable turns.

Here the exposition is, in Sternberg’s terms, mostly concentrated and preliminary. The early scenes fill us in on the basic situation. Wanda is among several women met at the bus by Elsa. This is a compact way to suggest how much this class depends on the arrival of emigrant labor. Wanda is then taken to the family’s sumptuous villa. We learn about the situation as she does, and this introductory stretch culminates in Wanda’s introduction to her cramped basement room. In good traditional fashion, the exposition quickly encourages us to sympathize with the protagonist by showing her treated unfairly. On the basis of the information we get, the film’s first “act” becomes a tensely rising action in which Wanda becomes victimized by the petty conflicts that wrack the family.

A second long section begins in a lighter key, with the dismissed Wanda returning after some months, in a scene parallel to the opening. This chunk provides another concentrated dose of information, bringing us up to date on the family’s situation. Comic complications emerge when the family has to cope with a new, more pressing set of demands.

In good Renoirian fashion, Oberli gives everyone a dose of sympathy. The frailties of the son and daughter get nuanced and softened, and we see this coddled pair as less selfish than self-destructive. The action tapers into cringe comedy (drunken embarrassment) and farce (an errant cow), but it’s steered by carefully modulated character revelation, particularly on the part of Elsa, who is played by an indominatable Marthe Keller.

My Wonderful Wanda keeps surprising you to the very end; it trains us not to take everything for granted. There’s even a classic theatrical denouement, itself twisty, which is undercut by a final shot of GOFAC (Good Old-Fashioned Art Cinema) uncertainty. Yet after each reversal, you think it had to be that way. What happens later is consistent with the exposition we’ve built up.

Surprise, postponed

Concentrated exposition, gathered in an opening or elsewhere, sets our expectations, so new story information can modify or revise them. For instance, when Wanda is summoned late at night to Gunther’s bedside, I assumed he needed meds or some help going to the toilet. The expository scenes had set her up as a traditional caregiver. So I was surprised when she mechanically slipped into what became clear was a sexual routine. That prompted me to recalibrate my sense of their relationship, and it made me aware of the limits of what I’d assumed.

Which is to say that exposition as a process is usually partial. We don’t get everything in the backstory at once, and sometimes what’s suppressed is central (as in My Wonderful Wanda). A more extreme example is François Ozon’s Summer 85 (Été 85). Here the expository information is distributed much more widely across the film. We get the backstory only gradually and piecemeal. Because some important information is withheld, the film nudges us toward certain expectations that need to be adjusted.

Again, I have to be careful about spoilers, so let me talk generally. In the book that I mentioned and for many years since, I’ve written a lot about flashbacks. One common schema for flashbacks is the crisis structure. The plot starts near a story’s climax and then suspends the outcome in order to shift back into the past and show how the crisis came about. The crisis structure can provide a film’s overall intrinsic norm of narration, so we expect that this pattern will carry through from scene to scene.

Ozon, another elegant storyteller, knows we have learned the crisis structure. When the opening of Summer 85 shows the teenager Alex dragged into a corridor and then interviewed by police authorities, we’re encouraged to summon up our experience of other movies. A crime has been committed, and he’s either a witness or a suspect. Ozon sets up a familiar to-and-fro pattern between past and present, an investigation and the mysterious crime leading up to it.

The distributed exposition provides flashbacks that take us chronologically through the events leading up to the night of the arrest. Alex is drawn into a love affair with David, a charismatic older boy. With his mother David runs a shop on the beach. She is slightly scatterbrained and seems unaware of their passions, while Alex’s parents are likewise in the dark (and surely disapproving). When the English au pair Kate shows up on the beach, Alex fears David will abandon him, and we expect that a classic romantic triangle will drive the film forward.

Except that’s not quite what happens. As Alex’s jealousy deepens, we might expect a sort of Patricia Highsmith crime to ensue. Instead, Ozon dares to go with a less brutal but more plausible turn of events–one that makes us reevaluate why Alex is being investigated, and what his actual crime is. By distributing exposition slowly across the whole film, Ozon not only creates a lot of curiosity about what has actually happened, he’s able to arouse expectations that will get challenged by new revelations. He exploits the how of narration to modify our understanding of what has occurred–and, it turns out, why.

I’m sorry to be so cryptic, but I face the reviewer’s dilemma of not giving away plot twists that should take you by surprise. Here, though, the surprises aren’t short and sharp, as in My Wonderful Wanda. They unfold more gradually and allow you time to think–about the characters and their motivations, and about what you took for granted might have happened. You might even feel a bit ashamed for misjudging Alex, who turns out to be loyal and forgiving in ways we might call unexpected. Yes, dancing is involved.

Surprise?

My Wonderful Wanda has a straightforward arc of conflict and resolution. Summer 85 is more nonlinear, skipping to and fro through time, but it too can be plotted as a drama of tension and release. What then to say about Kala Azar? It’s another film that teaches us how to watch it, and how to think through it. But it seems to lack those traditional patterns of coherence.

Or rather, it has other patterns. Instead of a drama of conflict and change, it explores a situation built out of routines, gradually revealed and eventually varied. This is another plot strategy, one familiar from “art cinema.” It builds a mystery into not only the story action but into the way the story is told. What is going on? And why am I told about it in this way?

Start with the title. It refers to a severe infectious disease spread to animals and humans by sandflies. It’s currently raging as a pandemic in over seventy countries. But the film Kala Azar is less about the disease (although we spot some lesions on characters who might be infected) than about the relations of humans and animals–specifically, some marginal Greeks scrounging a living on the outskirts of a city, along with the dogs, cats, and other creatures that wander into their lives.

There are three strands of action, each with its own routines. Most prominent are the couple, a young man and woman working for a service that cremates household pets. The couple live mostly on the road in their van, gathering pet remains from households and bringing them back to a central facility. They then return the ashes (not always scrupulously preserved, it seems) to the waiting owners. Another couple, the woman’s father and mother, keep stray dogs in their house. A third line of action involves Orguz, a migrant worker glimpsed from time to time at a chicken farm nearby.

The central couple have started adding roadkill to their cargo, as if believing that these creatures too deserve a serious farewell to life. And at certain points the story strands meet, although glancingly. In something close to a traditional climax, the young man, provoked by seeing a shooting party, takes a decisive action.

All of what I’ve told you is built up through dozens of short scenes, usually without dialogue. There’s probably more going on here than I’ve been able to grasp on one viewing. But the sparse, widely distributed exposition, and the apparent looseness of the plot challenge us to fill in things as best we can. Just as important, by not providing a traditional dramatic arc, director Janis Rafa encourages us to shift our attention to other aspects of her film.

We’re invited, for instance, to examine shot composition, to explore the landscapes on which the camera dwells, to scrutinize textures and gestures. These items are sometimes seen at one remove, through dirty panes of glass or layers of focus or in slim apertures.

Entire scenes often chop off faces in order to emphasize the contact that the bodies make with their surroundings, or to turn bodies into pure pattern, as when two grieving pet lovers are shown dressed identically.

These visual strategies may seem a bit arty, but I think they build up a tactile sense of the environment of these routines. Rafa has said that she wanted to evoke the “animalistic” quality of the imagery, which isn’t only a matter of a low camera position. The sensuous quality of the vegetation, streams, and roaming dogs comes across strongly. Kala Azar earns its severe gravity through its patient attention to details of a world in which humans and animals interact in very tangible ways. Stray animals meet stray humans, and the visual style registers the encounter with quiet nuance.

From concentrated preliminary exposition, to distributed and elliptical exposition, to what we might call minimal exposition: This continuum shows some creative options available to filmmakers in telling their stories. Each one invites us to build up expectations, to reconsider new information in the light of what we knew (or thought we knew), and to assemble a coherent line of action. In other words, we think. That’s not all we do, but it’s a big part of how we watch movies.

As usual, special thanks to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Jane Harrison, Curtis Woloschuk, and their colleagues for their help during this reliably exciting festival. This is usually the time of the year when Kristin and I wish we lived in Vancouver, and that feeling is sharpened by the health crisis now engulfing so many countries. Cinema helps keep us civilized.

These and other films we’ve reviewed should be making their way to other festivals, so we hope you have a chance to catch up with them.

For more on the narrative strategies I’ve discussed here, see Meir Sternberg’s magisterial Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction (1978). This is in my view one of the great books in narrative theory.

For more on narratives built on threads of routines, see this earlier entry on Chop Shop and other films at Ebertfest. An entry on editing pursues the between-your-ears theme.

Kala Azar (2020).

Mirror neurons and cinema: Further discussion

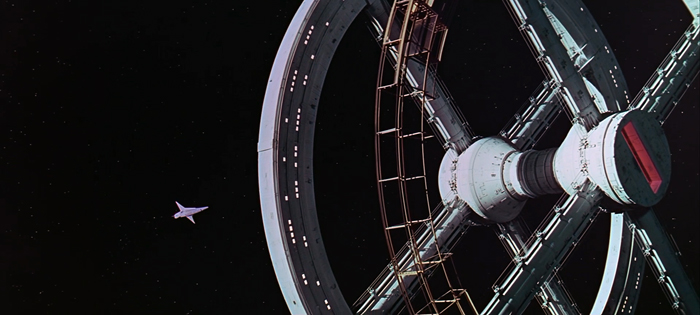

The Fugitive (1993).

DB here:

How do we respond to films? How are they designed to have effects on us? How do our responses outrun the “programmed” effects filmmakers aim to create?

These are perennial questions of film studies. Since the 1990s, neuroscientists have tried mapping our brains’ reactions to moving images, and one school of thought in that tradition has sought answers in the phenomenon of mirror neurons.

In my spring seminar, I tried to introduce students to a bit of this debate. First I laid out what I’ve taken to be the most useful psychological findings for my research–what has been known as “classic cognitivism,” stemming from the New Look psychology of the 1950s and 1960s.

At the same time I wanted the group to consider alternative theories, and the timing of the book The Empathic Screen, by Vittorio Gallese and Michele Guerra, seemed propitious. In addition, I learned of Malcolm Turvey’s response to their research and brought that essay to the seminar. For some years Malcolm has been advising caution about importing scientific research into humanistic studies generally and film studies in particular.

Because of the coronavirus, our seminar had to meet online, so I prepared an online text version of my planned lecture. One advantage of that was that I could get very long-winded about things. But it also meant I could post a shorter prepublication version of Malcolm’s essay on the subject. And remote access brought him into the seminar to make his case when we met.

I invited a response from Vittorio and Michele, and they duly sent one along. It is published here, followed by comments from Malcolm and me.

If you haven’t read my initial entry or Malcolm’s, I hope you will try before you read what follows. (Just homework; they won’t be on the final.) If you saw them at the time, a quick look back should suffice.

And yes, The Fugitive is involved. Eventually.

The Neuroscience of film: A reply to David Bordwell and Malcolm Turvey, and a contribution to further the debate

Vittorio Gallese and Michele Guerra

The contribution cognitive neuroscience can offer to film studies and in a broader perspective to the debate within the humanities is at the same time potentially priceless and to be carefully evaluated. Still in its early infancy, the field of “neurohumanities” represents a great challenge to a new way of thinking our relationship with the mediated worlds of the arts. In the last twenty years, more or less, we have been observing a very productive exchange between psychologists, cognitive scientists, neuroscientists and scholars from literature, theater, art, music, dance, and cinema, aiming to develop what Shaun Gallagher would call a “critical neuroscience”, suitable to inform a critical theory about the role our brain-body system plays in our aesthetic experiences.

What is at stake here is, on the one hand, the relevance of these experiences in our lives, the nature of our being “storytelling animals” (to borrow Jonathan Gottschall’s definition), both when we produce stories and when we play the role of readers or viewers, and the updating of our embodied relationship with the simulated worlds of the arts and the technologies we live in and through. On the other hand, we are facing a fascinating challenge for theory, in our case film theory, where words like action, interaction, empathy, intersubjectivity, we have been using for years within our fields of study, have to be reconsidered after the neuroscientific discoveries of the last decades.

The idea both of us shared at the beginning of the research that has brought us to perform experiments on cinema, to test the role of motor cognition during film watching and then to the publication of our book The Empathic Screen. Cinema and Neuroscience, was – and still is – that the contribution of cognitive neuroscience is first of all theoretical, as the one of psychology or cognitive science has been within the humanities, and then empirical, trying to shape, step by step, a new proposal to study parts of our film experience, which can confirm, renew, or in some cases overturn our ideas.

We know that the debate is still oscillating between two positions which we could, just to be clear and simple, describe as “neuromaniac” and “neurophobic”, where in the first case the risk is seeing neuroscience as the right place for explaining and clarifying the secret of life, while in the second case the risk is not seeing the productivity of a confrontation with its theories and empirical findings. David Bordwell’s and Malcolm Turvey’s entries on David’s blog about this topic and our book are a relevant sign of the need of debating about neuroscience and film, and we are confident that the next chances for exchange – the film journal Projections is going to schedule an issue to host part of this debate – will widen the discussion, involving scholars with different and enriching positions.

What we would like to do here, as a short reply to some of David’s and Malcolm’s observations, is to put forward three lines for reflection that we consider methodologically important to carry on the debate facing directly the core of the matter, and that guided the writing of The Empathic Screen. First of all, we want to say something about what we mean when we say “neuroscience”, what neurons can do and what they cannot, until where neuroscience can talk, and where it has to stop and leave room to theory and to ideas for new research within this open minded new field. Secondly, we have to ask ourselves which kind of film theory can host such a new debate, how it can converse with the main theories that have been taking the field in the last decades, and how we can think of teams and groups of research able to develop the critical neuroscience we need. Lastly, we would like to say something about why it is important to do experiments, what a serious experiment can give us, and what is its function for the debate (on this point, the abovementioned entries already said something).

1) Critical Neuroscience. It is hardly disputable that there cannot be any mental life without the brain. More controversial is whether the level of description offered by the brain is also sufficient to provide a thorough and biologically plausible account of social cognition – and of aesthetic experience. We think it isn’t. Such assertion is based on two arguments: the first one deals with the often overlooked intrinsic limitations of the approach adopting the brain level of description, particularly when the brain is considered detached from the body, or when its intimate relation with the body and the contextualized relation the body entertains with the world are neglected. The second argument deals with social cognitive neuroscience’s current prevalent explanatory objectives and contents, in many quarters still dominated by the logocentric solipsism heralded by classic cognitivism. As we wrote in the book, we think that “neuroscience can offer a genuine contribution to the re-definition and comprehension on new empirical grounds of fundamental and paradigmatic themes of the human condition, such as the perception of images and the construction of our network of relations with objects and other human beings.

Action, perception and cognition are terms and concepts describing different modalities which are permanently bound by the embodied and relational essence of all living beings, including humans.” In that respect, some theoretical premises David Bordwell cites, like the modular mind as proposed by the analytic philosopher Jerry Fodor, are patently contradicted by neuroscientific research. At the same time, to quote our book again, “If the neuroscientific approach to cinema [proposed in this book] is to be applied successfully, it must be critical, its potential and its heuristic limitations must be clear, it must be open to dialogue and constructive collaboration with other disciplines such as the history of cinema and the theory of film, philosophy and other fields of studies.” Neurosciences are aptly declined in the plural, because in spite of the same basic methodological approaches and methodologies, the questions neuroscientists ask and the answers they are seeking by applying those approaches and methodologies can be incredibly different.

In the last thirty years or so, when investigating human social cognition cognitive neuroscience has mainly tried to locate the abovementioned cognitive modules in the human brain. Such an approach suffers from ontological reductionism, because it reifies human subjectivity and intersubjectivity within a mass of neurons variously distributed in the brain. This ontological reductionism chooses as level of description the activation of segregated cerebral areas or, at best, the activation of circuits that connect different areas and regions of the brain. However, if brain imaging is not backed up by a detailed phenomenological analysis of the perceptual, motor and cognitive processes that it aims to study and – even more importantly – if the results are not interpreted on the basis of the comparative study of the activity of single neurons in animal models, and the study of clinical patients, cognitive neuroscience, when exclusively consisting in brain imaging loses much of its heuristic power and reduces to a 2.0 version of phrenology.

It should be added that the competence of understanding others -real people as well as fictional character- is uniquely describable at the personal level, and therefore is not entirely reducible to the sub-personal activation of neural networks in the brain, hypothetically specialized in mind-reading, as too many neuroscientists nowadays think. Indeed, neurons are not epistemic agents. The only things neurons “know” about the world are the ions constantly flowing through their membranes. Thus, we think that the final goal of cognitive neuroscience should be to profitably and personally conjugate the experiential dimension through a study of the underlying sub-personal processes and mechanisms expressed by the brain, by its neurons, and by the body. A cognitive archeology that can successfully integrate our knowledge of the personal level of our experiences.

2) Film theory. For what concerns its theoretical contribution to film studies, our position in The Empathic Screen is that cognitive neuroscience can play a role in the study of spectatorship, film style, and the analysis of new devices and the ways we interact with them. Obviously these aspects are strongly intertwined, as when we study the effects of camera movements on motor cortex activation (in one out of the six chapters of the book) we are, for instance, already studying the viewer’s basic response and his or her motor involvement during film watching, the impact of some stylistic elements on film composition, and the evolution of these movements in new aesthetic forms like those implied by an action camera, or a drone (this is also the reason why we decided to dedicate the last chapter of the book to the matter of new mediations provided by the screens of our laptops, smartphones, and the like).

Though David wrote that our book is “the fullest account” of mirror neurons application to cinema, we think that it would be more correct to say that The Empathic Screen is perhaps the fullest account of the application of embodied simulation (ES) theory to film studies. Basically, this is what we have been working on since 2012, when a first theoretical article (“Embodying Movies: Embodied Simulation and Film Studies”) appeared in Cinema: Journal of Philosophy and the Moving Image, and then when we presented and discussed the outcomes of our three film experiments in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, Cognitive Science, and PloS One. Of course, ES relies on the discovery of mirror neurons, but as it has been demonstrated in an articulated debate which has gone through philosophy, aesthetics, psychology, psychoanalysis, linguistics, and the arts, ES theory goes beyond the (scientifically proved) action and functioning of mirror neurons to enter the discussion on the role our brain-body system plays when it is engaged in real life and virtual environments.

We found that the questions raised by ES theory had been to some extent anticipated by the first physiological studies on film between the 1910s and 1920s (with relevant examples in Italy and France), and the almost coeval American literature on the didactics of cinema, where people like Epes Winthrop Sargent, Henry Albert Phillips, or Victor Oscar Freeburg focused both on “action” as the basis for film style and cinematic intersubjectivity, and the idea that the response of our senses to film movement, like to any physical movement, takes place before we have time to interpret the dramatic significance of the visible stimulus. Of course, as argued in our book, we do not think that film experience could be explained just focusing on action and the viewer’s responses to motor stimuli, but we think that film cognition should not ignore the role of motor cognition, and unfortunately this is what happened till now with few exceptions (the more noticeable back in the 1920s, then in the ambitious season of French filmology, and in some notes by Maurice Merleau-Ponty for a 1953 course at the Collège de France). Neuroscience can provide inspiration to explore this field, and it can also provide new methodologies to support theories and to update and problematize some of them.

Sometimes the most skeptical scholars say that neuroscience when applied to arts, tells us nothing new, or just already expected things. Obviously, we could say the same of semiotics, phenomenology, or cognitive science, but this is not the point. We do not need just “new things”, or new data, we need theories capable of raising more questions, of articulating and inspiring new lines of research, of shedding light again on neglected topics. Otherwise we would fall in the trap of expecting the definitive answers from the study of the brain. As we wrote in the Introduction to the book, our goal was “to present a study of film starting from the sensorimotor and affective implications, identifying a series of neurophysiological mechanisms as a tool for the deconstruction and comprehension of the conceptual instruments usually adopted in debates on the various aspects of cinema.” From this perspective Murray Smith, in his Foreword, emphasizes very well our pluralist approach across the history of film theory, putting forward the strong proposal of a new conjugation of the experiential dimension of cinema with the study of the underlying sub-personal processes and mechanisms expressed by the brain-body. It is from here that a discussion has to start. To us, it is not useful to give up such a complex and enriching debate taking a pessimistic position that does not consider the complete scientific debate behind ES theory. The history of film theory, from the classical period to the present, has greatly profited of the confrontation with science, even when some insightful observations came from very debated arguments (sometimes not confirmed arguments, unlike the case of mirror neurons). This doesn’t mean that we have to ignore the debate around scientific matters, but that we have to cope differently and more profoundly with the science on the theories we propose and discuss, not being “optimistic” or “pessimistic” (read, in this case, neuromaniac or neurophobic), but just informed and critical.

3) Experiments. In his essay David Bordwell wrote “my model of the spectator is agnostic about how the processes are instantiated in physical stuff. Doubtless retinas and neurons and inner ears and the nervous system are involved, but I’m not providing the details. I have no idea how to do so.” Neuroscientific experiments, as those described in The Empathic Screen, aim to shed light upon the contribution of the brain-body to our relationship with films. As we wrote in the book, “What appears on the screen, the ways and means, the strategies of appearance in cinema are the result of the direct relationship our perceptual system has with technology and are influenced by production processes and needs that consolidate the social aspects.” The naturalization of mediated forms of intersubjectivity, such as the experience of film, should start from the deconstruction and reconfiguration of the concepts that we normally use to describe it, by literally studying their component parts and where they come from through the experimental approach of investigation and the level of description of the brain-body system allowed by neuroscience.

To that purpose, we decided to start investigating some important elements of film style, whose intrinsic performative character is betrayed by its etymology from the Latin stilus, the ancient writing tool. We did so by focusing on some constitutive elements of what does it mean to perceive a film: camera movements and montage, which filmmakers employ to modulate spectators’ engagement and possibly intensify it. We decided to side with what many filmmakers do, that is, conceiving of style from a bottom-up perspective, concerned with the perception of film and the ways to calibrate what the spectators see. We should add that our take on visual perception, hence on film perception, parts from the standard account of vision as the mere expression of the visual part of the brain. To the contrary, evidence shows that vision is multimodal, as it encompasses the activation of motor-, tactile- and emotion-related brain circuits.

The experiments on camera movements described in The Empathic Screen, kindly discussed by David Bordwell and Malcolm Turvey, were originated by the idea that it is possible to test whether and to which extent spectators’ bodily perception of the film can be partly determined by their simulation of camera movements. The rationale being that the more these movements mimic human bodily movements –as with the Steadicam– the more they activate motor simulation in spectators’ brains, hence intensifying their reactions to them.

Thus, in the first experiment we correlated the electroencephalographic activation of spectators’ brains during the observation of clips showing an actor performing hand actions shot with a still camera, zoom lens, dolly and Steadicam with their explicit rating of engagement with the same clips. The results showed that clips shot with the Steadicam evoked the strongest motor simulation and correlated with the most intense perception of camera movements’ resemblance of realistic bodily movements and identification with the filmed actor (see Heimann et al., 2014).

In the second experiment the same rationale was used to test what happens when the different camera movements film an empty room. Once more, and in spite of the total lack of filmed bodily actions, the spectators’ brains showed the strongest motor simulation when perceiving clips shot with the Steadicam. In this experiment, we added some open questions to further explore the spectators’ phenomenal experience of the observed film clips: the results showed that the Steadicam induced the strongest motor simulation and led the participants to feel like walking together with the camera’s eye (see Heimann et al., 2019).

Taken together, these two pioneering experiment show for the first time that the Steadicam’s power of bringing the audience literally into the scene is related to its capacity to trigger stronger motor simulation and stronger feelings of engagement than all the other tested camera movements. We never claimed that spectators’ whole film engagement amounts to simulating camera movements. We argued that, “If film has something to do with subjectivity, it is to the extent that its moving form bears the imprint of a subjectivity”, as posited by Dominique Chateau, our two experiments provide empirical support to the idea that the intersubjectivity instantiated by film can be profitably studied by focusing on the ‘motor cognition’ stimulated in spectators by the film techniques employed. Furthermore, we think that our results can also offer a valid contribution to the debate within film studies on the supposed lack of subjectivity of the Steadicam, as argued by Jean-Pierre Geuens (1993-94) who held that the Steadicam produces a totally disembodied type of viewing.

Even when delimiting in such a way the field of empirical investigation, as we did with our experiments, a caveat is in order: one should bear in mind that a lab is not a movie theatre and participants in the experiment are not members of a film audience (film scholars are obviously perfectly aware of this aspect, as it is at the basis of several experiments in the field of the neuroscience of film). The whole experimental context aims at mimicking those conditions in the best possible way, but it remains true that experimental conditions are nothing but an oversimplified and coarse replica of real life situations. Of course, this does not apply just to our experimental approach to cinema, but to cognitive neuroscience at large.

Any empirical approach uses experiments to verify hypotheses that generate predictions. Obviously, both hypotheses and predictions do not grow out from the void, but are consonant to and inspired by the presupposed theoretical background, hopefully based on previous empirical evidence.

We think that our hypotheses are based on rock-solid ground, as they capitalize upon almost three decades of neuroscientific research on the perceptual and cognitive role of the motor system, with results that go from single neurons’ recordings in macaques, birds, rodents and humans to non-invasive behavioral, EEG, and fMRI studies carried out on the human brain in hundreds of labs around the world. We believe that the adoption of a comparative perspective, framing the cognitive functions and aesthetic proclivities of humans within a broader evolutionary scenario may secure a deeper understanding of human cognition – hence also of film perception – than the experimental approach still endorsed by many cognitive neuroscientists, whose study of the brain translates in the neo-phrenologic reification of the ‘boxology’ of classic cognitive science into brain areas, supposedly housing the very same boxes. A telling example comes from the endless brain imaging experiments realized to support the hypothesis that propositional attitudes (e.g., beliefs, desires and intentions) ‘reside’ in distinct brain areas. Unfortunately, empirical evidence showed that the activation of those brain areas is neither causally relevant nor specific to engage in mindreading activity, whatever that means.

We think that these experiments that still receive the acritical acceptance by many quarters of cognitive science, are less illuminating on the relationship between brain and cognition than the perspective offered by the embodied cognition approach. With our book, we aimed to show the heuristic potentialities of this approach when applied to film theory.

When the debate starts, it means that it is time to make a new and updated point on the forms of confrontation between science and the arts, what we try to do, coming from a different training, working around the multiannual project of The Empathic Screen, and keeping open the discussion with colleagues, friends, and scholars from several fields of research. Are we exerting an optimism both of intellect and will? We don’t know, we are just doing research in a very challenging and promising field.

Response from Malcolm Turvey

I thank Vittorio Gallese and Michele Guerra for their reply to my blog entry about their book, The Empathic Screen, and its arguments about camera movement. Although they do not respond to my criticisms of their work, in their reply they reiterate some of the principles informing their neuroscientific research on cinema as well as the results of their experiments. Here, I will comment on some of these, pointing to areas of both agreement and disagreement.

Gallese and Guerra contrast what they call the “neuromaniac” and “neurophobic” positions about the role of neuroscience in film studies. Personally, I don’t subscribe to either. My position (which I develop in a forthcoming paper in Projections from which my blog entry is extracted) is what I call serious pessimism about the possible contribution of neuroscience to the study of film and art. Serious pessimism is not neurophobia, as there is nothing to fear about neuroscience (except perhaps overconfidence in its explanatory possibilities). Rather, I doubt that neuroscience can answer certain kinds of questions we standardly ask about film and the other arts, and I’ll provide an example in a moment. But even if I am wrong about this, the neuroscience of film is still in its infancy, and we must wait and see whether its discoveries have a significant impact on our discipline or not. New scientific paradigms often generate an “irrational exuberance” about their explanatory possibilities until researchers less invested in their success expose their flaws and limitations. I think we should suspend judgment about the contribution of neuroscience to film studies until more results are in. Call me “neuro-cautious.”

This is not Gallese and Guerra’s position. Although they claim not to be “neuromaniacs,” they seem to assume that neuroscience, or at least their version of it, will have a major impact on the study of film and the arts if it hasn’t already. They write in their reply that it “represents a great challenge,” that “words like action, interaction, empathy, intersubjectivity [that] we have been using for years within our fields of study, have to be reconsidered after the neuroscientific discoveries of the last decades,” and that their work is “a tool for the deconstruction and comprehension of the conceptual instruments usually adopted in debates on the various aspects of cinema.”

Notice, however, that they do not provide a single example of how the neuroscience of film has required us to revise our concepts of cinema, and I find it hard pressed to think of any. To be sure, neuroscience can and has revealed the neural underpinnings of our perceptual, cognitive, affective, and bodily capacities, including those engaged by film and other forms of the moving image. Perhaps it will also lead to a conceptual revision at some point, at least in our theories of cinema. But it hasn’t, to my knowledge, done so yet.

For example, the two experiments that Gallese and Guerra have undertaken on camera movement seem to show, as they report, that “the Steadicam’s power of bringing the audience literally into the scene is related to its capacity to trigger stronger motor simulation and stronger feelings of engagement than all the other tested camera movements” (my emphasis). I write “seem” to show because in my blog entry and the longer article from which it is extracted, I provide a number of reasons why Gallese and Guerra’s two experiments don’t in fact support their thesis about the Steadicam and camera movement. Most obviously, it cannot “literally” be the case that we are brought “into the scene” when simulating a Steadicam’s movements because, literally speaking, we are typically sitting in a seat while watching a film. But even if a deflationary version of this thesis is defensible, in what respect does it necessitate conceptual revision or represent “a great challenge”? They do not say.

Gallese and Guerra’s more modest assertion that “cognitive neuroscience can play a role in the study of spectatorship, film style, and the analysis of new devices and the ways we interact with them,” is, I think, incontestable, although, to repeat, it is an open question how big a role. This does not mean, however, that we should accept every neuroscientific theory of film unconditionally. As with any theory, a neuroscientific theory must be tested. Is it conceptually precise and logically coherent? Are its conclusions licensed by the evidence? Are there better theories? Just because one contests a specific neuroscientific theory, as I do in the case of Gallese and Guerra’s theory, does not mean one rejects neuroscience or is a neurophobe. Indeed, the testing of theories is one reason why (neuro-)science, and other forms of rational inquiry, make progress. Unfortunately, perhaps due to the authority of science, film scholars who draw on scientific paradigms such as mirror neuron research and Embodied Simulation sometimes neglect to do this, including Gallese and Guerra in their book.

Gallese and Guerra are also right, I think, to warn against “ontological reductionism” in neuroscientific film studies. For there is much we can discover about camera movement and other aspects of film without knowledge of the “sub-personal” level of the brain. For instance, in his book the The Dynamic Frame, Patrick Keating explores the rich history of camera movement in 1930s and 1940s Hollywood, showing how available technologies along with industrial organization shaped the use of various types of camera movement by filmmakers for specific purposes, such as revealing characters’ mental states. He does all of this without appealing to neuroscience, and in general much of film studies, like the humanities more broadly, is aimed at understanding the “personal” level of intentional, broadly rational actions (“the space of reasons”) of human beings in particular historical circumstances.

Neuroscientific descriptions of brain activity won’t tell us the reason(s) Hitchcock used the short dolly or tracking shot toward Sebastian’s keys in the scene from Notorious that Gallese and Guerra discuss in their book and I in my blog entry, or the function Hitchcock intended it to perform in the film. Nor will they tell us anything about the historical conditions–the available technologies, the craft practices operative in Hollywood at the time, the financial and other industrial conditions of the moment, the period norms governing camera movement–that constrained and shaped Hitchcock’s decision to use that particular camera movement where and when he did. To be sure, neuroscientific explanations may be able to supplement, enrich and perhaps even modify humanistic ones such as Keating’s. But this does not mean they replace them. This is one reason I am pessimistic about the contribution of neuroscience to film studies.

Gallese and Guerra would presumably agree with at least some of this, as they rightly decry the “endless brain imaging experiments realized to support the hypothesis that propositional attitudes (e.g., beliefs, desires and intentions) ‘reside’ in distinct brain areas.” They also warn that “neurons are not epistemic agents. The only things neurons ‘know’ about the world are the ions constantly flowing through their membranes.” However, it is not clear to me that their theory avoids either reductionism or the homunculus fallacy. For all of their talk of “embodied” cognition and simulation, and their professed hostility to “classical cognitivism,” they seem to locate the viewer’s purported feeling of being brought “into the scene” in a brain area too, namely, the activation of the motor cortex by camera movement. Identifying an area of the brain (the motor cortex) and correlating its activation with an observable form of human behavior (feeling that one is brought “into the scene”) seems like pretty standard brain science to me. And there could be many reasons a viewer feels that they are brought “into a scene” in addition to the degree of motor cortex activation in their brains. Meanwhile, in claiming that our neurons “simulate” the actions of others (including Steadicams), Gallese and Guerra appear to be guilty of ascribing “knowledge” to neurons. For how do our neurons “know” the meaning or purpose of the action they are supposed to simulate? And to who or what do they simulate it? I point to these and many other problems with their account in my forthcoming paper in Projections.

Science, and rational inquiry more broadly make progress in part through rigorous criticism of theories. Theories are either discarded in light of criticisms, or they prosper through successful efforts to show that criticisms of them can rebutted or that they can be improved in light of said criticisms. It is notable that Gallese and Guerra don’t engage with any of my (or David’s) criticisms of their theory in their reply. I would love to learn from them why I am wrong: why, in other words, there is after all enough empirical data to support their bold claim about camera movement, why the counter-examples I cite don’t in fact disprove their theory but can be accommodated by it, why they are not guilty of the homunculus fallacy among other philosophical errors, and so on. I would love, in other words, to learn why I shouldn’t be so skeptical of their theory of camera movement and the mirror neuron research informing it. But this can only happen if they respond to criticisms of their theory and show why they are mistaken.

There is no doubt that neuroscience has a role to play in film studies. The doubt, on my part at least, is about Gallese and Guerra’s specific neuroscientific theory of cinema.

Some final remarks from DB

I see Vittorio and Michele’s reply as a promissory note. It’s a delineation of their difference from other neuroscientific researchers and an aspirational account of their future contributions. It doesn’t, as far as I can tell, offer any replies to Malcolm’s or my criticisms of the arguments laid out in their book.

For example, they claim that in Notorious, any suspense we feel “has nothing whatsoever to do with the story” (p. 54). Malcolm’s essay suggests that what they call a “precise schema of camera movements and editing that keeps us on the edge of our seats” works largely because of higher-level knowledge we have of the plot, the situation that the heroine is in, and what’s at stake in her duplicity. Vittorio and Michele do not here clarify or qualify their argument.

Likewise, reading that La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc is an example of the “oppressiveness” of the fixed camera, compelled me to mention that the film is filled with camera movements; in fact, it starts with one. More generally, their claim that “the involvement of the average spectator is directly proportional to the intensity of camera movements” (p. 91) would make most of the first thirty years of cinema pretty uninvolving. But then, what does “involving” mean here?

Most generally, I would be interested in Vittorio and Michele’s response, however brief, to the critique of mirror-neuron theory advanced by Gregory Hickok in The Myth of Mirror Neurons and other writings. They mention above “the (scientifically proved) action and functioning of mirror neurons” without further explanation, but as an outsider browsing the literature, I’m struck by a good deal of debate about these neurons’ status and functions. Here, for example, is an interesting exchange between Vittorio and Hickok from 2015. There’s a good, nontechnical talk by Hickok from three years later.

My amateur sense is that Vittorio and Michele have relaxed a strict adherence to mirror-neuron accounts in favor of what they call Embodied Simulation, a broader view close to phenomenology. I am not sure that this is necessarily a step forward. Phenomenology all too often proffers lyrical description rather than concrete explanation. In any case, I take it that their position relies upon the Simulation Theory of Mind, an alternative to the “Theory of Mind” Theory. It would be good if they would spell out how ES is preferable to its philosophical rival.

There is much more in The Empathic Screen that should be discussed. The chapter on multimodality offers a lot of evidence on how visual stimuli can activate the sense of touch. There’s also a great deal of broad critical commentary on particular films, and frequent invocations of earlier film theorists. This last point is raised in their reply. I have to say that claiming one’s theory harmonizes with an earlier theory isn’t itself terribly convincing, for the reason that the early theory might be faulty. As for the critical interpretations offered in the book, many of those seem detachable from the theories being proposed. Several I find hard to follow. (“While in the zoom-out the iconic annuls the diegetic, in the zoom-in the reasoning of the diegetic limits that of the iconic,” 99).

On one new point Vittorio and Michele make in their reply, I want to register a specific disagreement. They write:

Sometimes the most skeptical scholars say that neuroscience when applied to arts, tells us nothing new, or just already expected things. Obviously, we could say the same of semiotics, phenomenology, or cognitive science, but this is not the point.

Actually, I think that semiotics and cognitive science have produced fresh knowledge about film. (Phenomenology is another story.) Often these lines of inquiry show that apparently unconnected phenomena have fairly coherent underlying principles. Exposing their “logic” allows us to understand creative options. For instance, Metz’s Grande Syntagmatique of narrative film, probably the most famous, or notorious, semiological enterprise, showed that there might be a coherent set of expressive alternatives in constructing scenes and sequences. The concepts of paradigm and syntagm did useful work in organizing craft practices and audience skills.

Similarly, I’d argue that robust cognitive findings like the primacy effect, anchoring, belief fixation, “folk psychology,” hindsight bias, and “the curse of knowledge” help us understand something important about how stories are constructed. They suggest that principles of narrative construction and uptake depend on both folk causality and informal reasoning routines, the heuristics and biases and shortcuts we use in everyday life. Again, ideas from another discipline can reveal patterns we might not otherwise detect. We want to make new discoveries, not re-label things we already know!

For now, I’ll finish with a couple of broad points about the book’s research strategies. This is an effort to specify further the outlines Vittorio and Michele offer above.

I consider film studies largely an empirical enterprise. Not an empiricist one: We need concepts, hypotheses, rival explanations, interrogation of our presuppositions, and the like. Central to the enterprise, I think are precise research questions that we can recast as analyzable problems. Even though Vittorio and Michele claim that their perspective will generate new questions, I am left wondering exactly what those are.

I infer that they are searching for causal accounts of film style. I’m hospitable to this impulse. I once hoped that mirror neurons could be part of a causal explanation of certain responses we have to film. But I think the results so far are scanty and vague, for reasons rehearsed in my entry.