Archive for the 'Film theory: Cognitivism' Category

You and me and every frog we know

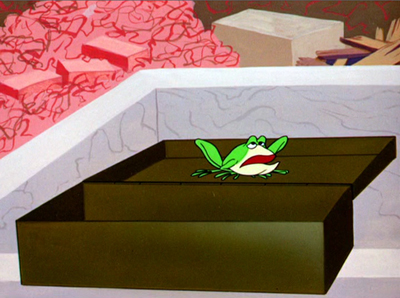

Frog TV (2014, N. Joe Myers).

DB here:

Be patient, the frogs are coming. But first, a bit of film theory.

Movies in code

Once many film scholars were captivated by the idea that our responses to a movie were coded, we might say, all the way down.

Here, code means something like a way of assigning meaning that is both arbitrary and relative to time and place. The code is arbitrary in that it might just as easily have been otherwise. A code is relative because in different circumstances it might vary.

One prototype for the early semiologists was the code regulating traffic. In a traffic light, there is no natural or necessary connection between green and “Go!” or red and “Stop!” We’ve just agreed on these meanings. We could have assigned red to “Go!” and green to “Stop!” And indeed other cultures might do just that. A gesture may mean something friendly in one culture and something naughty in another.

The presumption is that because a code is both arbitrary and relative, it has to be learned. You need to live in a culture to understand the traffic code and the code of gestures. Through either observation or training (such as learning the codes of written language) you master the codes of your culture.

Clearly, movies include many codes. A film can show us traffic lights or hand gestures. Films include language as well, which is coded to a high degree. The crucial question is: How much in our responses to film is coded?

Almost everything, some said. There was a wing of semiology ca. 1970 that suggested that both what’s represented in film and the ways things are represented are arbitrary and culturally variable in the extreme. Some theorists suggested that just recognizing an object in a shot relies not on natural perception but rather on a code. Indeed, the argument was made that “natural” perception is itself coded. A favorite corollary of this was that language was such a powerful code that it reshaped perception. Put bluntly, if your culture’s language doesn’t distinguish red from green, you won’t see the traffic light’s top and bottom lamps as different colors.

I resemble that remark; or do I?

Surely, somebody will say, many film images resemble the things they portray. A shot of a man and a woman looks, in certain relevant respects, like a man and a woman. We’re able to recognize them as such. Yet 70s semiology held that there was nothing natural about this. The image-object resemblance, often called “analogy,” and “iconicity,” was considered to be coded.

Here, for instance, is Umberto Eco in 1967:

We know that it is necessary to be trained to recognize the photographic image. . . . Even if there is a causal link with the real phenomena, the graphic images formed can be considered as wholly arbitrary.

Christian Metz brings out the cultural variability of recognition in a 1970 essay:

The apprehension of a resemblance implies an entire construction whose modalities vary notably down through history, or from one society to another. In this sense the analogy is, itself, codified.

Here is Dudley Andrew commenting on this line of thought in 1984:

The discovery that resemblance is coded and therefore learned was a tremendous and hard-won victory for semiotics over those upholding a notion of naive perception in cinema.

The semiological tradition pointed out, correctly I believe, that the parallel between the image and the thing it represents lies not in some relation between the two but in the comparable ways in which we understand each one. But can this process be considered both arbitrary and relative?

Can we, for instance, imagine a culture in which recognition was fundamentally arbitrary—where a picture of a bunch of bananas depicts, by cultural fiat, a clutch of cherries? More exactly, where a picture of a bunch of bananas is seen as a clutch of cherries?

We can imagine a very capricious filmmaker who set up a code with an introductory credit:

Every time I show you a shot of bananas, see cherries.

But you couldn’t see cherries. At best, the result would involve imagination, not perception. Even cooperative spectators would recognize the bananas as bananas, though they would go on to think of cherries.

The distinction between perception and thought seems to have been blurred in semiological theory. Perhaps the 70s arguments traded on the various meanings of “perception”, such as “I perceive that he’s unhappy today” or “I want to change your perception of Rosicrucianism.” The same would go for various senses of “recognition”: “I recognize the father’s face in the son,” “He had aged so much I didn’t recognize him.” These senses of the word bring in matters of conception and attitude, not just visual input.

Perception and evolution

Not that perception is easy to define. When the semiologists were writing, they may have been influenced by psychological theories that assigned a big role to concepts in perception—“top-down” models that claimed perception to be “cognitively penetrable.” It’s fair to say that there’s now good evidence that the perceptual activities involved in visual recognition are largely fast, automatic, fairly dumb, and cognitively impenetrable.

Another error, it seems to me, was also the product of the period: the ignoral of evolution. The 1970s advocates of sociobiology seem to have been simply ignored, perhaps because they seemed to be naïvely attempting to see culture as nature. Yet I think that J. J. Gibson was right (also in the 1970s) in proposing that evolutionary theories could help explain why perceptual recognition is so swift and efficient.

Creatures evolved in an environment that selected for accurate perception, including very very very fast recognition of predators, prey, and mates. Evolution, we might say, provided long-term survival training in recognition, weeding out any creatures who didn’t register salient features of their world. A hominid who needed explicit teaching to recognize a tiger wouldn’t last as long as one who came to the task with senses pre-tuned. As with learning spoken language, all that would be needed is some exposure to the regularities of the ancestral environment. The baby born into our world is bombarded with redundant information that is non-arbitrary and non-relative; she quickly grasps that a face is more informative than a knee. It will take her quite a bit more time, along with some tutelage, to learn traffic signals and even more to learn to read.

Cinema taps some of our most fundamental capacities. Film images aren’t reality, but they present certain salient triggers for us to recognize what they represent. Indeed, the very perception of motion in movies is an illusion—a glitch in our visual system that cannot be arbitrary or culturally relative. Nobody in any time or place sees movies for what they are, a succession of still images. There are enough cues for movement to fool everybody’s visual system. And films preserve enough other features of the world to trigger automatic recognition processes. Perceptual recognition of something in the image is on the whole neither arbitrary nor culturally variable.

The likeliest conclusion is that we share with other creatures some native propensities which, given the right early exposure to the physical and social world, will be exercised in comparable ways. Of course there are differences. Minnows can’t enjoy Matisse, and we can’t smell as well as dogs can. Still, sensory systems overlap among many species.

So consider the frogs of the field: they toil not, neither do they spin.

Frogs like the front row too

We know quite a bit about how frogs see the world. A classic paper in animal neurology, “What the Frog’s Eye Tells the Frog’s Brain,” was crucial in suggesting the highly specialized nature of nerve fibers feeding information to the visual system. Those data streams—about edges, movement, and variable illumination—get reintegrated, but not necessarily thanks to high-level mental activity. “Early vision,” in frogs and in us, involves not some some brainy entity interpreting the image on the retina but rather several specialized, quite stupid systems that pool information before thought ever enters the picture. No codes necessary. What came to be called “distributed processing” does a large share of the job.

Though untrained in the codes of our culture, these frogs appear to recognize what matters to them, even on the mini-movie screen. (Sorry the video embed no longer works.)

If pigeons can quickly learn to interpret human faces in pictures, and female jumping spiders react to video images of males as if they were real, we shouldn’t be surprised that frogs can respond very—ah—actively on first exposure to movies showing things they really care about.

Of course a lot of our activity isn’t as data-driven and mandatory as recognition. Higher-level concepts do all sorts of work when we watch movies, from understanding who the protagonist is to grasping a film’s theme or point. And of course all manner of conventions in films require sophisticated cultural knowledge. My point is just that some aspects of our response are very basic. I hazard that our responses to cinema mix together all kinds of skills, abilities, biases, and proclivities. A movie is a package of appeals, a buffet with something for all our visual and auditory appetites.

First, thanks must go to N. Joe Myers, who posted this neat experiment in natural perception a year ago. (Has the filmmaker tried it with an iPad or a computer monitor that would make the worms look huge? Would that induce large-scale frog panic?) For vastly more frog-related information, go to N. Joe’s page here.

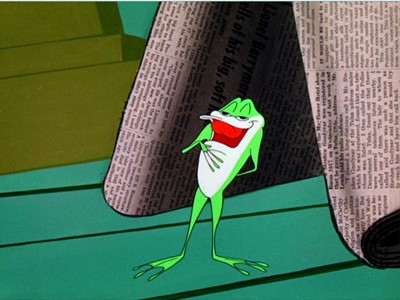

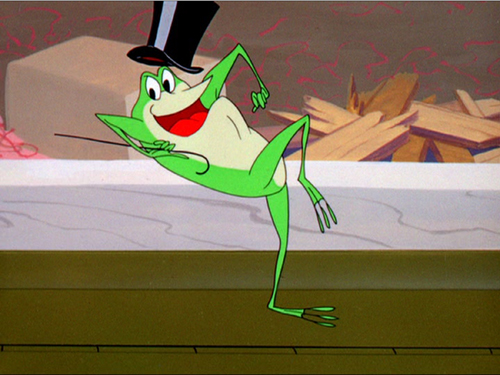

Thanks also to Darlene Bordwell, who called the piece to my attention, and Barb Anderson who pointed me to the spider studies. The illustrations are of course from Chuck Jones’ Warner Bros. cartoon One Froggy Evening (1955).

My quotations are from Umberto Eco, “Articulations of the Cinematic Code,” and Christian Metz, “On the Notion of Cinematographic Language,” both in in Movies and Methods, ed. Bill Nichols (University of California Press, 1976), 594 and 584; and Dudley Andrew, Concepts in Film Theory (Oxford University Press, 1984), 25. See also Metz, “Au-delà de l’analogie, l’image (1969),” Essais sur la signification au cinéma, vol. II (Klincksieck, 1972): “Resemblance itself is codified, because it makes appeal to a judgment of resemblance: the judgment of an image’s degree of resemblance will vary according to the time and place” (154).

J. J. Gibson’s writings mounted a strong case for what he called “direct perception” in The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception (Houghton Mifflin, 1979). His ideas were developed by Claire F. Michaels and Claudia Carello in Direct Perception (Prentice-Hall, 1981) and, more critically, by James Cutting in Perception with an Eye for Motion (MIT Press, 1986); pdf. Joseph Anderson’s The Reality of Illusion: An Ecological Approach to Cognitive Film Theory (University of Southern Illinois Press, 1998) is the trailblazing application of Gibson’s ideas to cinema. More generally, Paul Messaris’ Visual Literacy: Image, Mind and Reality (Westview, 1994) reviews the empirical findings that show virtually no cultural variability in perceiving line drawings and photographic images as depictions of recognizable persons, places, and things.

At some point in discussions of the cultural variability of perception, someone is likely to mention Eskimo cultures’ purported range of words for snow. But this is a long-standing error. See Geoffrey K. Pullum’s The Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax and Other Irreverent Essays on the Study of Language (University of Chicago Press, 1991) and John H. McWhorter’s The Language Hoax: Why the World Looks the Same in Any Language (Oxford, 2014).

What happened to these 1970s beliefs about the film image’s coded nature? It seems to me that when semiology as a research perspective waned, academics mostly stopped talking about the issue of resemblance and recognition. Researchers retained a general sense that films are coded, but they concentrated on less controversial conventions, like social stereotyping, representations of power, and so on. I’ve been told that the level of perception is merely a matter of “physiology” (wrong word) and thus of no consequence for the important issues that scholars should be studying. But of course filmmakers shape our response chiefly by controlling our perception, and if we want a comprehensive account of how films work and work on us, we can’t ignore this level of the viewer’s activity. I consider this problem in the title essay of Poetics of Cinema.

For a more developed argument about how films bundle a range of appeals, from sensory triggors to high-level concepts, see my essay, “Convention, Construction, and Cinematic Vision” in Poetics of Cinema. Online, I discuss these matters here and here and here (under “Representational Relativism,” which involves not frogs but our ancient ancestors).

P.S. 21 September 2015: Apes appear to remember episodes after watching movies. Thanks to Bill Evans.

One Froggy Evening.

The book stops here: Theory, practice, and in between

Tinpis Run (Pengau Nengo, 1991).

DB here:

Apart from things I’m reading for research (academic monographs, 1940s Hollywood novels, star bios and autobios), the film books I like best are blends. They bring together information, ideas, and opinion. I learn some facts about films and their contexts. I encounter some concepts that illuminate those facts. And I get introduced to some arguments about the best way to understand the information and ideas. In my ideal world, the blend winds up answering some questions—maybe questions I’ve thought about, maybe ones that never occurred to me.

I especially like books that have one foot, or toe, in filmmaking practice. The poetics of cinema I try to practice is, from one angle, an effort to grasp the principles underlying filmmakers’ creative choices. Sometimes those choices are announced by the filmmakers; sometimes we have to reconstruct them on the basis of the films and other data. So for me a drastic split between theory and practice isn’t very informative.

These pronunciamientos are but prelude some comments on books that push several of my buttons. Maybe they’ll do the same for you.

Philosophy goes to the multiplex

Stagecoach (1939); True Grit (1969).

What book brings together Cézanne and Tony Soprano, Gregory Peck and Simone de Beauvoir, Plato and South Park, The Twilight Zone and Wittgenstein?

Okay, I know the answer: Practically every book by a littérateur convinced that Great Big Theory gives you a way of talking authoritatively about anything, especially pop culture. So I rephrase my question: What book brings together these and many more items with care, rigor, and infectious amusement?

That narrows the field quite a bit. A strong candidate is a book that has chapters like “What Mr. Creosote Knows about Laughter,” “Andy Kaufman and the Philosophy of Interpretation,” and “The Fear of Fear Itself: The Philosophy of Halloween”— not the movie but the holiday itself.

The short answer to my question: Noël Carroll’s new collection of essays, Minerva’s Night Out: Philosophy, Pop Culture, and Moving Pictures.

Noël Carroll isn’t merely the most important philosopher ever to write about popular culture. He has been for decades a major force in film theory and criticism, as well as a philosopher making contributions to moral and legal theory, historiography, and a welter of other areas. His fertile mind and prodigious typing skills have combined to produce over fifteen books and a list of articles running to triple digits.

It’s not just quantity, of course. For those of us in media studies, Carroll has been the most well-informed and adroit analyst of trends in film theory. His Philosophical Problems of Classical Film Theory (1988), Mystifying Movies: Fads and Fallacies in Contemporary Film Theory (1988), and Post-Theory: Reconstructing Film Studies (1996, coedited with me) have proven enduring contributions to the debates about the best ways to understand the nature and functions of cinema. He is, as you can tell, a controversialist. Like all good philosophers, he’s devoted his life to getting the ideas right. Over the same period, Carroll has proven himself a wide-ranging practical critic, discussing classic silent films (especially comedy), modern avant-garde work, and Hollywood movies from the 1930s to the most recent releases. This isn’t to slight his important work as a dance and television critic as well.

It’s not just quantity, of course. For those of us in media studies, Carroll has been the most well-informed and adroit analyst of trends in film theory. His Philosophical Problems of Classical Film Theory (1988), Mystifying Movies: Fads and Fallacies in Contemporary Film Theory (1988), and Post-Theory: Reconstructing Film Studies (1996, coedited with me) have proven enduring contributions to the debates about the best ways to understand the nature and functions of cinema. He is, as you can tell, a controversialist. Like all good philosophers, he’s devoted his life to getting the ideas right. Over the same period, Carroll has proven himself a wide-ranging practical critic, discussing classic silent films (especially comedy), modern avant-garde work, and Hollywood movies from the 1930s to the most recent releases. This isn’t to slight his important work as a dance and television critic as well.

This focus on film theory stems from the fact that Noël’s first Ph.D. degree was in film studies. But soon afterward he went on to get a second Ph.D. in the philosophy of art. His cinema research was always philosophically informed, but once he became a card-carrying philosopher, he commuted between two academic areas. He helped found the broader movement called Philosophy of Film, and he continues to write on a lot of different topics. His Humour: A Very Short Introduction is due out in a couple of weeks.

Minerva’s Night Out scans the range of his interests—not only all types of media (which he genuinely enjoys) but a variety of the philosophical puzzles they pose. These he tackles with verve, patient but not plodding analysis, and a range of references that make you wonder if this guy has seen and read pretty much everything.

Here’s the sort of thing that Noël thinks about. We all know that to enjoy a movie fully we often have to appreciate the way in which a star’s performance builds on previous roles. But there’s a problem. The fictional world of a film makes only certain types of knowledge relevant to our experience. At the center of this knowledge is what Carroll calls the “realistic heuristic,” the premise that all other things being equal, the things happening in the fiction are assumed to operate under the laws of our everyday world. Sherlock Holmes (whether incarnated by Basil Rathbone or Benedict Cumberbatch) is presumed to have lungs like the rest of us, unless we’re told otherwise. Likewise, it is true in the fiction that a room’s walls are solid, while they might in reality be fake. If I see the walls as painted sets or green-screen mattes, then I’m not responding to them as part of the story world.

The same attitude shapes our sense of the unfolding plot. Armed with the realistic heuristic, we have to assume that characters’ destinies are open, that many things can happen to them (as with us). But the principles by which a movie fiction is constructed—say, boy gets girl—aren’t part of our realistic heuristic. “What we believe is probable of a movie qua movie is radically different from what we believe to be probable in a movie conceived as a credible fictional world.” Movie lore tells us that boy will get girl, but to grasp and respond to the story emotionally, we have to feel in doubt. (Perhaps this is what people mean when they say that a mistake in the movie, or a distraction in the auditorium, takes them “out of the movie.” We’ve left the fiction.)

Similarly, movie lore connects the Ringo Kid of Stagecoach to Rooster Cogburn of True Grit (the original) because John Wayne portrays both. Yet the characters live in different, sealed-off story worlds. Ringo and Rooster have no knowledge of each other. Barring transmigration of souls, how can their connection be part of our experience of either movie as a consistent fiction?

Similarly, movie lore connects the Ringo Kid of Stagecoach to Rooster Cogburn of True Grit (the original) because John Wayne portrays both. Yet the characters live in different, sealed-off story worlds. Ringo and Rooster have no knowledge of each other. Barring transmigration of souls, how can their connection be part of our experience of either movie as a consistent fiction?

Carroll comes up with an ingenious explanation. Movies summon up star personas in the manner of allusions. Just as our experience is enhanced when we see a movie refer to another movie—Carroll’s example is a citation of Rocky in In Her Shoes—so do our mind and emotions respond to the presence of the star, as either a continuing allusion throughout the film or a one-off one, as with a cameo or walk-on. As he often does, Noël points out that practicing filmmakers use the concepts he elucidates. “Allusive casting” became part of the 1970s trend of paying homage to old Hollywood, but even in the studio era it wasn’t unknown. Carroll points to The Bigamist (above left), in which somebody says another character looks like Edmund Gwenn. Of course said character is played by Edmund Gwenn.

I’ve shrunk down Carroll’s line of reasoning to give you the flavor of the way he thinks. His piecemeal approach to theory focuses not on loosely named topics but specific questions. For example:

What if anything justifies us talking about popular culture as all one thing?

How do fiction films engage us in the emotional lives of their characters? Hint: It’s not through identification.

What makes us laugh at Mr. Creosote, rather than be horrified or disgusted by his vomit-laced gluttony?

How does a tale of dread, such as Poe’s “The Black Cat,” differ from a horror story?

Why should we care about Tony Soprano, who barehanded commits “crimes of which I don’t even know the names”?

Are the feelings awakened by art akin to friendship?

What role do moral emotions, such as the sense of community, play in our response to characters?

As for the jokes, they’re not of the esoteric academic type but rather straight-out funny. Just one essay, on the vague/implausible (you pick) notion that modernity (traffic, window displays, lotsa flashing lights) changed the very faculty of human perception:

The human eye rarely fixates; saccadic eye movement is the norm. We did not suddenly become attention-switching flâneurs in the late nineteenth century; we have been natural-born flâneurs since way back when.

No amount ot cultural conditioning will succeed in making normal viewers worldwide literally see human faces as cross-sections of centipedes.

I’m sure he’d give any indie filmmaker the rights to make Natural Born Flâneurs.

Viewers and their habits

Natsukawa Shizue in Town of Hope (Ai no machi, 1928).

Carroll tries to figure out certain logical conditions on spectators’ experience in general. That’s one province of film theory. But he’s also sensitive to the constraints on those conditions, the ways that historical and institutional circumstances can shape how viewers watch movies. (That’s part of the star-as-allusion argument.) Other researchers, historians by trade but sensitive to theoretical implications, have tried reconstructing the activities of theatres, trade personnel, and audiences in particular times and places.

A good cross-section of approaches has just appeared from Karina Aveyard and Albert Moran. Their anthology Watching Films: New Perspectives on Movie-Going, Exhibition and Reception contains 22 chapters of empirical research spread across the Europe, New Zealand, Australia, and the U.S. The researchers take us to particular cities and towns (Antwerp, Nottingham, and the Scottish Highlands) and to various points in history, from the 1920s to the present, passing en route the arrival of TV and the effects of the VHS revolution. There are also considerations of early reception theorists like Barbara Deming, along with studies of fan activities in Italy and elsewhere. Altogether, you couldn’t ask for a more enticing sampler of contemporary strategies for studying how audiences interact with cinema. Multiplicity long preceded the multiplex.

A good cross-section of approaches has just appeared from Karina Aveyard and Albert Moran. Their anthology Watching Films: New Perspectives on Movie-Going, Exhibition and Reception contains 22 chapters of empirical research spread across the Europe, New Zealand, Australia, and the U.S. The researchers take us to particular cities and towns (Antwerp, Nottingham, and the Scottish Highlands) and to various points in history, from the 1920s to the present, passing en route the arrival of TV and the effects of the VHS revolution. There are also considerations of early reception theorists like Barbara Deming, along with studies of fan activities in Italy and elsewhere. Altogether, you couldn’t ask for a more enticing sampler of contemporary strategies for studying how audiences interact with cinema. Multiplicity long preceded the multiplex.

A similar approach, but focused with razor acuity on a single country and period, is Hideaki Fujiki’s Making Personas: Transnational Film Stardom in Modern Japan. This book is an expedition into a nearly sunken continent, Japanese film of the silent era. Frustratingly few films have been preserved from those years, but paper documents abound. Fujiki has made intense use of them to answer the question: What were the cultural causes and results of the early star system in Japan?

The answers are rich and detailed. The very first stars weren’t on the screen at all; they were the benshi who narrated the silent program. Hideaki goes on to trace the career of the paradigmatic male star, Onoe Matsunosuke, and to show how his main traits (virtuosity and stature as “great man”) were reinforced by a troupe-based business model. Later chapters focus more on female stars, with emphasis on the influence of American actresses like Clara Bow. The flapper figure shaped not only Japanese female performers but women in real life.

Fujiki traces in some detail how the “modern girl” or moga floating through Ginza owed a good deal to Hollywood movies. He makes good use of what films survive from this period, particularly The Cuckoo (Hototogisu, 1922) and Town of Love (Ai no machi, 1928). In-depth analysis of the star image Natsukawa Shizue, above, allows him to discuss fan culture and movies’ role in accelerating trends in fashion and advertising. In all, Making Personas is a fascinating consideration of stardom as both an industrial and social construction in one of the world’s most important national traditions.

Education and environment

Institutions of another sort feature in two impressive books from the prolific Mette Hjort. She has had the very good idea of assembling documentation about how film schools work. How do different schools, academies, and more informal agencies understand the craft of filmmaking? What ethical values and social commitments are brought to the classroom and enacted in the production process? What are the histories of film schools around the world?

The answers come in two packed anthologies, The Education of the Filmmaker in Africa, The Middle East, and the Americas, and The Education of the Filmmaker in Europe, Australia, and Asia. From these we learn of the creative practices put into action by institutions in Nigeria, Palestine, Denmark, the West Indies, China, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Sweden, Germany, Australia, Japan, and many other localities. We get a real sense of intercultural communication and its breakdowns. Rod Stoneman points out that Tinpis Run, Papua New Guinea’s first indigenous feature, demanded postproduction discussions when outsider viewers couldn’t distinguish the villages presented in the story.

Things happen in these places that would astonish students at UCLA and NYU. Hamid Naficy tells of taking his Qatar students to Tanzania, where they worked on research projects only after spending the morning doing clerical and custodial work in schools and hospitals. We learn of children’s filmmaking initiatives in Mexico City, programs for at-risk youths in Brazil’s City of God favela, and students making photo and sound montages in Calcutta. One purpose of Mette’s collections is to remind us that film training goes far beyond getting your MFA and a showreel on a maxed-out credit card.

Hjort’s initiative, while already stimulating, ought to be continued and enriched. People are starting to understand the importance of film festivals within film culture—as distribution mechanisms, publicity arms, and in a roundabout way feedback systems shaping production. (One essay, by Marijke de Valck, points out the move by festivals toward film training.) More generally, we need to understand film education at all levels as shaping film production and film audiences.

Hjort’s introduction emphasizes that institutional politics are always related to larger political and cultural concerns. Social implications of filmmaking are brought to the fore in another emerging area of research. As each day seems to signal a new ecological disaster, it’s timely that a critical school has emerged to track how films and TV represent our relation to nature and technology. Among the scholars working prolifically in this area are Robin L. Murray and Joseph K. Heumann.

Hjort’s introduction emphasizes that institutional politics are always related to larger political and cultural concerns. Social implications of filmmaking are brought to the fore in another emerging area of research. As each day seems to signal a new ecological disaster, it’s timely that a critical school has emerged to track how films and TV represent our relation to nature and technology. Among the scholars working prolifically in this area are Robin L. Murray and Joseph K. Heumann.

Their first book, Ecology and Popular Film: Cinema on the Edge argues that apart from films like An Inconvenient Truth, which wear their green politics on their sleeve, there’s a much bigger and broader tradition of films about humans and the environment, ranging from fictional films with explicit messages, like Happy Feet (2006), to films with unintentional ones, like The Fast and the Furious (2001).

As “second-wave” practitioners of eco-criticism, Murray and Heumann aren’t much concerned with cheerleading or finding villains. They want to explore how media representations of the environment have responded to various cultural pressures. Their two most recent books are good examples. That’s All Folks? (2009), building on their analysis of Lumber Jerks in their first book, concentrates on American animated features. They perform careful symptomatic readings while also providing industrial context, such as the tactics by which Lucas and Spielberg adapted to the growing dinosaur craze of the 1990s.

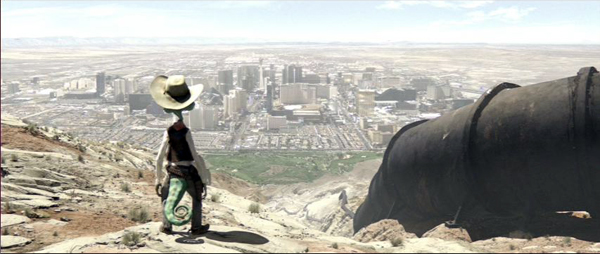

In Gunfight at the Eco-Corral (2012), Murray and Heumann tackle the Westerm on similar grounds, ranging from Shane and Sea of Grass to There Will Be Blood and Rango. Reading these chapters I was reminded how often the genre’s plots hinge on disputes over natural resources. Water, minerals, timber, grazing land, and what the authors call “transcontinental technologies” like the telegraph and the railroad are at the heart of classic Westerns, and the genre’s formulaic conflicts often have strong ecological resonance. This is the sort of criticism that refreshes your vision of movies you think know very well.

Their next book, Film and Everyday Eco-disasters is due out in June.

Things stick together

Lone Survivor (2013).

Finally, two more books merging theory and practice—but from opposite ends of the spectrum. One question that intrigues me involves coherence and cohesion in film. Roughly speaking, coherence involves the way the whole movie hangs together. If it’s a narrative film, how do the scenes or sequences fit into the larger plot? If it’s not narrative, what other principles organize the whole shebang? Cohesion involves how adjacent parts fit together—shot against shot, sequence to sequence. Both these concepts have practical implications, since every filmmaker confronts concrete choices about them in scripting, shooting, and editing.

Michael Wiese has contributed enormously to our understanding of filmmaking practice by publishing a series of books on cinema craft. The most recent one I know is by Jeffrey Michael Bays and it bears directly on cohesion. It’s called Between the Scenes: What Every Film Director, Writer, and Editor Should Know about Scene Transitions. Bays himself has written and directed films, written radio dramas (a great place to study transitions), and published books on filmmaking.

Between the Scenes is an entertaining and damn near exhaustive account of the ways that images and sounds can tie one scene to another. Bays considers aspects of space, like location or objects or actors; time; and visual graphics. The book also shows how sounds can bind scenes or emphasize sharp contrasts. In the example from Lone Survivor above, a soft whir of helicopter blades is heard over the first shot and grows louder when we move from the map to the landing area.

In a web essay called “The Hook” I explored some aspects of this process, but Bays goes into much more detail with many recent examples. He also raises ideas I never considered. For example, if we think of narratives as people traveling from one place to another (and most narratives are that, at least), then every filmmaker faces a choice: Show the journey or don’t show it. And if you show it, what parts and why and what does it tell us about the character? The larger point is: “Make sure you know where every character goes between every scene.” Thinking about this suggests ways to enrich your presentation, and it allows the characters—if only in your imagination—to inhabit a more fleshed-out world. Ideas like this can provoke everyone, filmmakers and film scholars alike.

Small-scale links between parts are considered more theoretically in Chiao-I Tseng’s Cohesion in Film: Tracking Film Elements. Trained in functionalist linguistics, Tseng brought her expertise to bear on film analysis. The results show a remarkable kinship between devices in language and certain cinematic transitions. Such linguistic functions as saliency (what stands out) and presumption (what can be taken for granted) are found in audiovisual texts too. For example, a shot taken over one character’s shoulder tends to lessen that character’s saliency and make another character, the one we see more clearly, more prominent.

Small-scale links between parts are considered more theoretically in Chiao-I Tseng’s Cohesion in Film: Tracking Film Elements. Trained in functionalist linguistics, Tseng brought her expertise to bear on film analysis. The results show a remarkable kinship between devices in language and certain cinematic transitions. Such linguistic functions as saliency (what stands out) and presumption (what can be taken for granted) are found in audiovisual texts too. For example, a shot taken over one character’s shoulder tends to lessen that character’s saliency and make another character, the one we see more clearly, more prominent.

This example is simple, but once Chiao-I gets going, she’s able to show how nearly every cut or camera movement can be seen as activating a unique tissue of cohesion devices. The words in a paragraph not only refer to ideas or things; they also link to other words in the paragraph and in the larger discourse. Similarly, in film, different aspects of the images and sounds stand out and adhere to one another instant by instant. Tseng’s analyses of passages in Memento, The Birds, The Third Man, and other films are accompanied by equally close studies of television commercials and educational documentaries. At the end, analysis is supplanted by synthesis, as she shows how the configurations she has pulled apart coalesce into levels that highlight characters and actions. It’s a fresh way to think about how we understand films within genres and stylistic traditions.

In effect, she’s showing the fine-grained patterns that emerge from the choices every filmmaker faces. It would be fascinating to sit in on a dialogue between Bays and Tseng, for they belong to the same community, or so I think anyhow. We’re all trying to understand aspects of cinema, and by focusing on certain phenomena rather closely, we have a good chance to understand them better.

So to the filmmaker who’s skeptical of theory, I say: We can’t think clearly without concepts, or talk clearly without terms. We need to develop rigorous ideas and arguments (i.e., theory) to understand film as best we can. But to the would-be theorist I say: Keep fastened on the look and feel of the films, and test your ideas and arguments not only against them, but against what you can find out about the craft of cinema, in all its historical implications.

I was pleasantly surprised, after I’d decided to talk about these books, to find work by Kristin and myself cited in some of them. Remaining coldly objective, however, I didn’t let these mentions diminish my praise.

Rango (Gore Verbinski, 2011).

Understanding film narrative: The trailer

The Wolf of Wall Street.

DB here:

At many points in The Wolf of Wall Street, we hear the voice of Jordan Belfort chronicling his exploits in building up a rapacious investment company. A few times he even addresses the camera.

What’s he doing? Well, he’s telling us a story, obviously. Stories are what many (not all) films present to us. But how, exactly, can we understand the storytelling process in film? What do the filmmakers do, and what do we do?

For my book Poetics of Cinema, I wrote a chapter called “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative.” This 2007 essay tries to come to grips with several questions. Some are pretty general. What makes a film a narrative? How does a narrative film shape our response? What roles do visual and auditory techniques play? What are the roles of emotional responses and broad cultural factors? How does characterization work in a movie?

Other questions are narrower. How revelatory is Hollywood’s three-act model of plot? How do we pick out a story’s protagonist? Do literary concepts like “narrator” and “implied author” apply to films?

Since the chapter is part of a larger book, some of these matters are dealt with at greater length in other chapters. Some are developed in other books, notably Narration in the Fiction Film, and elsewhere on this site. This essay was my attempt to boil down my thinking about filmic storytelling into one convenient, if sometimes sketchy, form.

Today I’m posting a corrected, slightly revised version of that chapter as a downloadable pdf file. Thanks to our web tsarina Meg Hamel, it has links as well. Students, teachers, researchers, and casual or ardent cinephiles: Make use of this as you like.

The essay is here.

This blog entry is a guide to the essay, or maybe just a trailer. As with a trailer, my use of The Wolf of Wall Street is illustrative; I’m not offering anything like a full analysis or even a review. And like most trailers, mine has spoilers.

The three dimensions I explore in the essay are narration, plot structure, and story world.

Dimension 1: Pushy narration

A film’s narration I take to be unfolding and organization of story information as the viewer encounters it, moment by moment. . (This is distinct from the term “voice-over narration,” like Jordan’s in The Wolf of Wall Street, though voice-over commentary is part of the overall narration.) Narration is designed to shape our itinerary through the film. It’s a complex array of cues that guide us in building up the story.

In The Wolf of Wall Street, the first dose of information we get is a TV commercial for the Stratton Oakmont investment company. We see busy, efficient brokers bent over their desks in a vast office as a lion paces the aisles. But then we get another view of the office, as partying staff prepare to launch a little man in a Velcro suit toward a target. The man is hurled, and one of the men who tosses him identifies himself as Jordan Belfort. We’re then launched into a sequence laying out Jordan’s lifestyle.

One thing this portion of the narration does is to peel back the staid, solid image of the brokering house and show the orgiastic self-indulgence behind it. What if Scorsese and his screenwriter Terrence Winter hadn’t included the commercial? Our sense of the contrast between public image and internal debauchery wouldn’t be so strong.

The quick scenes of Jordan’s lifestyle, driven by drugs, sex, and high living constitute a block of concentrated exposition. The narration could have introduced Jordan’s debauchery gradually through hints, but instead we’re told of it bluntly and swiftly. Jordan boasts that at age 26 he made nearly fifty million dollars a year. We’re coaxed to ask: How did he get so far?

This is, we might say, a curiosity question—a question about what in the past led up to the present. A film’s narration is often prodding us to ask just this question. A piece of narration may also provoke effects of surprise, as when the Velcro-target episode undercuts the corporate image. Surprise is central to narrative because knowledge is distributed unequally among characters and spectators; any character may have a secret.

There’s also suspense, which we can consider broadly as a sharpened anticipation of what might happen next. In The Wolf, I’d argue that there’s some suspense when Jordan, zonked on Quaaludes, must save Donnie from choking on a piece of ham. Curiosity, surprise, and suspense aren’t of course the only effects of storytelling, but they function as “master-effects,” in Meir Sternberg’s phrase. They are central to our comprehension of the story.

Style as narration

At the same time, narration is shaping our experience through film style. The staid tracking shot along the desks in the commercial, with the firm’s trademark lion prowling the aisles, clashes with the abrupt editing and freeze-frame that introduces Jordan. The actors’ performances, centrally the swaggering performance of DiCaprio, are part of narration as well. The soundtrack’s stylistic texture contributes a lot too, with Jordan’s voice-over and the music and effects creating a rousing, exhilarating effect. The narration’s use of film technique, I think, aims to summon up a shocked but fascinated and amused awareness of the decadent world that Jordan rules.

Throughout Wolf, Scorese’s stylistic choices serve narrational purposes. There are rapid montage sequences, commenting musical tunes, and dialogue hooks (“I won’t call him”/shot of Denham, called, approaching Jordan’s yacht). Scorsese’s fondness for rendering psychological states—here, druggy ones—is presented through classic “impressionist” techniques. As the film goes on, he starts to take us into characters’ minds through inner monologues and misperceptions (the smashed Ferarri). Stylistic patterning also contributes to the film’s tone of grotesque comedy, not just through the dialogue, delivery, and music but through editing. The potentially dramatic moment of Jordan rescuing Donnie with CPR is intercut with a Popeye cartoon: Jordan’s miraculous spinach is coke.

By shaping our knowledge, the narration also throttles the film’s emotional appeal up or down. For example, in one scene Jordan punches his second wife Naomi. Scorsese presents the action in a distant shot, in which a doorway allows us merely to glimpse the violence.

This choice lessens the impact of Jordan’s aggression. It gives us important information about the story action, but not nearly as forcefully as the tight close-ups of sexual and drug-fueled escapades in other scenes do. You could argue that closer and more visceral views (of the sort we get during Raging Bull’s domestic violence, as above) would make it harder to treat Jordan’s bad-boy high-jinks as entertaining.

A more detailed analysis would trace the overall development of the film’s narration. We’d consider, for instance, how it restricts our information at key points. Although the narration breaks with its attachment to Jordan to show Denham’s investigation, it doesn’t reveal Naomi’s scheme to divorce him. We learn of that only when he does. As we indicate in Film Art: An Introduction, “Who knows what when?” is a central question for understanding film narration.

Narration as inference-making

More generally, the essay develops in some detail a notion that’s central to understanding narration. I offer a mentalistic account of narrative understanding.

I think that a storytelling movie, through its narration, impels us to draw inferences. To follow a movie story is to turn the images and sounds into characters, actions, events, causes, and the like. This happens partly through fast, automatic inferences of the kind we make constantly in perceiving the world, and partly and more evidently through the inferences we make in building up that construct we call the movie’s story.

Everything I’ve been describing so far asks us to fill in, extrapolate, and draw conclusions at the level of comprehension. We take the Stratton Oakmont commercial as indicating trustworthiness. We’re encouraged to see the little-person-tossing scene as outrageous and boisterous but cruel, the amusement of people charged with a reckless energy. Jordan’s bragging montage sequence invites us see him as powerful, arrogant, and materialistic.

By saying that narration pushes us to make inferences I’m not suggesting that the inferences are models of deep thinking. They are, we say, commonsensical. In the multiplex, we’re not logicians. Understanding and responding to a story are processes based largely on folk psychology. In that respect, the chapter argues a point I’ve made elsewhere on the site.

Of course not all our inferences will be correct. It would be possible to knock down our first impressions of Jordan with information suggesting that beneath the sharkskin is a likable idealist. (That happens in Jerry Maguire.) Here, other sorts of moments steer our inferences astray. We’re led to think that Jordan drives his Lamborghini home safely, but that impression gets recalibrated the next morning. Earlier, when Denham visits Jordan on his yacht, the rather long, tense scene leads us to consider the possibility that the FBI agent is susceptible to bribery. His questions and facial expressions suggest that he’s weighing Jordan’s offer to help him with some investments. This interchange is conveyed in fairly tight shot/ reverse shots.

Only when Denham asks Jordan to repeat his offer does Scorsese cut to an angle showing that Denham’s colleague has, offscreen, quietly stepped close enough to bear witness to the bribe Jordan might offer.

Scorsese has choked off some information about the scene in order to yield a surprise, one that corrects the impression we were building up. One of cinema’s great pleasures is catching up with a narration that has been designed to lead us astray. Hitchcock fans, take note.

Dimension 2: Plot as pattern

You can also think about the narrative as having a more abstract, geometrical structure: that’s given to us as the plot. Narration creates on-line, moment-by-moment pickup; as viewers we go with the flow. The plot is more architectural, a sort of static anatomy of the film as a whole. We can think of it in a couple of ways.

As a map of a particular film, the plot consists of the overall arrangement of incidents. It lays out the story actions in time. It can proceed chronologically, as plots do most of the time, or it can rearrange incidents out of linear order. The Wolf of Wall Street follows the Stratton Oakmont commercial with the Velcro-target scene, and then presents Jordan at the height of his powers. But after the quick exposition of his lifestyle, the plot flashes back to his first day on Wall Street in 1987.

Now the film presents a mostly chronological layout. Jordan gets his broker’s license, loses his job, picks up a low-end one, and then rises to the spot running his company. This trajectory is sometimes interrupted by quick flashbacks filling in background on a character or a situation; we even get flashbacks within flashbacks. The overall time scheme is hazy, since we’re never shown exactly what point in time is “now.” There’s the suggestion that the initial flashback is rounded off when Jordan’s cohorts meet to plan the Velcro-tossing stunt, but that opening scene isn’t replayed, so we can’t be sure exactly when the opening flashback ends. The flashback must be finished at some indeterminate time late in the film, when Jordan’s fortunes decline and Naomi is alienated from him. But the narration whisks us along without establishing the firm framing devices of traditional flashback plotting.

From this perspective, every film establishes its own plot structure, based on the overall “geometry” of its scenes and sequences. There’d be a lot to say about this in The Wolf, such as the introduction of Denham (and the brief alternating scenes of his investigation) and the various lines of action that fill out the plot: Jordan’s addictions, his plan for an IPO, his two marriages, the SEC inquiry, his Swiss money-laundering schemes, and the like. The craft of screenwriting consists in large part of developing and braiding lines of action in this way. Several entries on this site, as well as many chapters of Narration in the Fiction Film and Poetics of Cinema, analyze how such plot patterns work in tandem with the narration’s unfolding.

Caught in the act(s)

Another way to think about plot structure is to consider how the particular film obeys broader principles of construction. Tragedy, comedy, melodrama, mystery stories, and other genres have distinct, widely-known conventions of plot geometry. There are as well traditions of plotting that cross genres.

In modern commercial cinema, the most famous structural convention is the three-act pattern. Kristin has proposed that Hollywood feature filmmaking is better thought of as adhering to a multiple-part principle based on characters’ goals. The film might have two, three, four, or more parts, depending on its running time and the ways it shows character goals created, reformulated, blocked, delayed, and fulfilled (or not). We’ve tested Kristin’s proposal in books (Storytelling in the New Hollywood, The Way Hollywood Tells it) and on this site (here and here and here and here).

The essay considers the matter more theoretically, but just to illustrate, I’ll hazard a layout of The Wolf of Wall Street’s plot structure. It’s nothing but spoilers, so I’ve flagged it all in olive green if you want to skip it.

Since Wolf runs about 173 minutes without credits, I think it can be usefully laid out in five large-scale parts. These are framed by a brief prologue (the commercial and the Velcro-target scene) and an epilogue summing up Jordan’s court sentence, his stay in a country-club prison, and his new career as “the World’s Greatest Sales Trainer.”

The Setup shifts from Jordan’s life at the pinnacle to his beginnings in the business and his rise as an entrepreneur. In the course of this portion he meets Donnie and the two assemble their team of eccentric, grotesque staff. After establishing Stratton Oakmont, Jordan demonstrates his sales technique and the script his salespeople will follow. This section consumes the first thirty-five minutes of the film.

What Kristin calls the Complicating Action, which resets the protagonist’s goals, centers on Jordan’s plan for an IPO and his affair with Naomi. Around the hour mark, Jordan is divorced and free to pursue the IPO, but now Denham of the FBI is following the company and the SEC is getting curious.

The Development section, which typically expands and delays the fulfillment of the goals set earlier, shows Jordan marrying Naomi, the firm’s frenzied launch of the IPO, and Jordan’s botched effort to bribe Denham. By about 96 minutes into the film, the two antagonists, Jordan and Denham, have faced off in a preliminary conflict. What remains is to see how Jordan will evade capture.

I’m inclined to see the fourth part as a second Complicating Action, because Jordan recalibrates his goal. Stratton Oakmont is making so much money he needs to find an offshore place for it. He decides on Switzerland, and the bulk of this section of Wolf focuses on whether he’ll be successful. But the SEC is breathing down his neck, and he momentarily considers quitting his firm. During a pep talk to his staff, his resolve weakens (he’s sold by his own rhetoric), and he decides to fight the regulatory battle. This is a turning point: now both the SEC and the FBI are on his tail with renewed vigor.

This section, a bit longer than the others, runs about forty minutes. I attribute that mostly to a wedged-in scene that’s almost pure delay: Jordan’s and Donnie’s wild night on Quaaludes, which ends with Jordan crawling toward his car, smashing it up, and saving Donnie from choking. Nearly all of this has no effect on the plot’s forward movement; Donnie survives and Jordan isn’t charged for the road mishaps. The only plot causality here is the fact that a wacked-out Donnie makes an incriminating call on Jordan’s home phone, which is tapped. This bit of action could have been handled much more briefly, but the Quaalude gluttony is so inherently funny, and forms such a plausible topper to the ‘lude motif throughout the film, that it’s expanded to a remarkable twelve minutes. This sort of delay is usually seen in Development sections, but because Jordan resets his goals in this section I’m considering it a Complicating Action.

The Climax (25 minutes) arrives when Jordan, hiding in Italy with Donnie and their wives, learns that Aunt Emma, his front for the Swiss money-laundering, has died. He must race back to Zurich to shift the money to a new account, and in the process the yacht is wrecked in a storm. He’s arrested and agrees to rat on his friends. Naomi divorces him. He tries to protect Donnie but fails and is sent to jail. In the epilogue he’s shown bouncing back, playing to an audience of suckers who share his dream of getting very rich.

Winter’s screenplay, with its parallelled and intertwined lines of goal-driven action and its reiteration of one large-scale component, a second Complicating Action, shows how the classical pattern can be expanded to fill out a longer-than-average running time.

Dimension 3: The story and its world

There’s a tendency to think of the story action as existing virtually before it becomes a plot and is presented through narration. It’s as if the story was already there, waiting to be turned into a film. To some extent, this can happen with documentary narratives and adaptations of novels, plays, and comic books. Nonetheless, as viewers we access a movie’s world only through narration and plot structures. In fact, “access” isn’t quite right. As I’ve indicated, I think that we construct the story inferentially, on the basis of the cues given by those other dimensions.

If every viewer has to build up the story herself, shouldn’t we have widely different senses of what happens? To some extent we do. People might fill in certain gaps differently, or draw divergent conclusions about what made something happen. Certain films, not typically Hollywood ones, do encourage more open explorations of the story situations. Here plot construction and narration may follow other conventions, such as those I’ve tried to chart in Narration in the Fiction Film and elsewhere.

Mostly, though, even in “independent films,” there’s a great deal of convergence among viewers’ inference-making. Sooner or later, we arrive at a common understanding of most of what happened and why. As we leave the shared realms of perception and comprehension, of course, viewers’ construals can diverge a lot. Once we get to abstract interpretations—such as whether The Wolf of Wall Street celebrates or condemns the anything-for-a-buck culture—we should expect a lot of variations. (I try to explain why this happens elsewhere in the book, in the essay “Poetics of Cinema.”)

“Three Dimensions of Film Narrative” considers the story and its world broadly, in terms of cues for causation and characterization. It focuses particularly on characters and how we understand them. Again I argue for an inferential model. This means that, as in real life, we’re practicing “mind-reading”—trying to figure out characters’ traits and temperaments on the basis of their behavior, trying to grasp their motives and goals. We build them up as persons on the basis of cues, and we ascribe to them many of the qualities we expect persons in the real world to exhibit. Again, folk psychology provides the ground: the film is likely to streamline and simplify the complexities of real-world personhood.

As viewers we don’t understand a character in isolation. Characters interact, and the narration and plot structure prompt us to compare them, rank them, sort them in different ways. In The Wolf, Jordan is handsome, brazen, and suave; Donnie, a classic weak friend, is awkward and homely, but he has a primal energy that matches Jordan’s slick élan.

Jordan’s father and most of his elders are more prudent and cautious than his crew, who are uninhibited. The guys are a bevy of misfits, distinguished from one another by looks and one or two tricks of demeanor.

Jordan’s first wife is a brunette hair stylist who voices doubts about his schemes; his second wife is a gorgeous blonde party girl who happily plunges into his lifestyle. In each case, the narration and the plot structure give us the necessary cues, usually redundantly. Jordan’s voice-over commentary reinforces the character information we get from the actors’ appearance and performance.

The essay also considers how films present character change. Sometimes characters come to learn more; they may not vary their distinguishing traits but they realize they have made a mistake. More deeply, characters may decide to get in touch with a suppressed side of themselves. That’s what happens, I think, in Jerry Maguire; he becomes the man his wife thinks he could be.

But very often characters don’t change. Jordan, in The Wolf of Wall Street, has an opportunity to confess, return the money he fleeced from his clients, and take his punishment. Instead, he insists that everything he’s done has been for his friends—the staff of the firm—and they deserve to succeed as he has. (Even though he is deceiving them too; he buys shares in his own IPO and orders the salespeople to push that stock.) What shocks many viewers about the film, I suspect, is that Jordan doesn’t become a better person in the course of his adventures. His punishment is light, he learns nothing, and by the end of the film he’s as amoral as he was when he started the company. (“Sell me this pen.”) As sometimes happens, the interest of the plot comes from watching a gifted, resourceful scoundrel adapt his techniques to changing situations.

But wait, there’s more

Okay, you may be asking impatiently. But why? Why offer these categories, carve things up, make supersubtle distinctions, concoct new terminology? Why not just do film criticism?

Well, partly because I want to articulate more than my response to a particular movie. I want to understand the more general ways in which films work and work upon us. I think we can usefully look for explanations of movies’ functions and effects, and these are things that ordinary film criticism doesn’t typically offer. For example, noticing how a film’s elements function with respect to narration, plot, style, and story world can do more than sensitize us to this or that movie. This sort of analysis can make us aware of broad norms of moviemaking and how particular films relate to those norms, currently and historically.

At the same time, the line of thinking I’m proposing casts light on the skills we deploy, mostly unawares, in experiencing films. No matter how simple-minded the movie, I think that we do things in following it; we exercise our narrative competence. On the other side, sorting things out this way can explain the range of choice and control open to the filmmaker. I think that the poetics of cinema I propose can help filmmakers become aware of the tools they are using–and perhaps encourage them to try other ones. My categories are derived from filmmaking craft, and perhaps they can in turn illuminate the practical tasks facing filmmakers.

A couple of final points. In the chapter I draw examples from a variety of films, many American (Cellular, Boyz N the Hood, You’ve Got Mail, etc.). Despite my consideration of Ashes of Time, Claire Dolan, Memento, and other films, some readers will ask why I don’t consider more non-Hollywood examples. The choice was strategic: Hollywood films throw the areas I’m charting into sharp relief. They provide clear-cut (not necessarily simple) examples of my points. And historically, the dominance of Hollywood film in the world’s theatrical market have given them a lot of influence. Much of what we think of as non-Hollywood is based on attempts to revise or reject those norms.

At the same time, I’m counting on readers cutting me some slack because I’ve written a lot about alternatives to Hollywood. My books on Eisenstein, Ozu, Dreyer, and Hong Kong cinema try to analyze diverse storytelling options. Elsewhere in Poetics of Cinema I discuss various narrative traditions, including varieties of network narratives and forking-path plots. Narration in the Fiction Film explores still other storytelling modes. And on this site I’ve had a lot to say about non-Hollywood constructive principles (for example, here and here).

The last section of the essay considers what is probably inside-baseball for many readers. Yet the underlying question is important. How adequately can film narrative can be understood on a model of literary narrative? Some theorists think that the basic principles of narrative are to be found in verbal storytelling, and narratives in other media must find equivalents for them. My own view is that narrative as a phenomenon gets mapped onto different media in varying ways. There may not be a single model that will be valid for plays, novels, dance, comic strips, radio drama, film, digital fiction, and so on.

For example, if Jordan Belfort were a character in a novel, certain weird things wouldn’t be happening onscreen. A first-person narrator in the novel can tell us only things that she or he knows about. But “inside” Jordan’s tale we get all kinds of scenes that he didn’t witness. True, he knew that FBI agent Denham was on his trail, but he couldn’t know the color of Denham’s office, or what Denham said to his colleagues. Nor could Jordan know exactly how the quarrel between his partner Donnie Azoff and his ally Brad Bodnik went down, even though we see the entire scene embedded in “his” telling.

Of course we can say that these scenes are just movie conventions. We accept that in film, first-person voice-over often includes scenes that the speaker didn’t witness, or maybe didn’t even know about. But that convention points to the limits of importing models of storytelling from literature to the study of cinema. A novel can’t wedge those things in without raising the question of how the narrator knows this. We just don’t ask such a question about Jordan.

By a path too winding to summarize here, these and other observations lead me to a counterintuitive conclusion: Narrative, at least in film, isn’t best understood as an act of communication from an author-like entity to a reader-like one. Why do I say that? How can film not be communication? Answer, too brief: What most people call communication I call converging inferences.

And to end my trailer, I suggest that we think of narrative in all media, most especially film, as inherently promiscuous. It will pull in anything that gets the immediate job done. That includes grabbing one element of ordinary conversation–a guy telling a story–without keeping the other bits of the communicative chain, such as feedback from a listener. Jordan is talking to us, but he doesn’t know we’re here, and we can’t interrupt him.

One more time: You can get the essay here. Thanks for reading!

In a way this post is a sequel to the previous entry; background on Meir Sternberg’s account of curiosity, suspense, and surprise can be found there. For more on the subject, see our category “Narrative strategies” and the essay “Common Sense + Film Theory = Common-Sense Film Theory?”

Many of the everyday terms we apply to stories are ambiguous or vague, so sometimes we need to define our terms or invent new ones. Take “narration.” In ordinary talk, can mean “voice-over commentary,” such as Jordan Belfort’s in The Wolf of Wall Street. But if we restrict our usage to just this form of sound, we don’t have a good term for the general flow of narrative presentation in the film, let alone films that don’t have voice-overs. So it’s useful to reserve “narration” for that general process and use “voice-over” in some form to describe the soundtrack’s role in that.

The same problem comes up with the term “point of view,” which has many different meanings. It might refer to first-person reportage, or what a character thinks and feels, or what she believes. (Obama is a good president from her point of view.) If we want to be precise in talking about these qualities of storytelling, we need to explain the terms we’re using.

And sometimes it’s just easier to introduce new terms. In the essay, I’ll sometimes call the plot the syuzhet and the story the fabula. Why the fancy terminology? Won’t “plot” and “story” do? Well, yes, up to a point. In this entry I did use those terms, and our textbook Film Art: An Introduction has done that ever since its first edition of 1979. Still, when we’re working within a research community, it helps to have terms, even unusual ones, which say exactly what we mean. The original readership for the “Three Dimensions” chapter knows that “plot” and “story” have different meanings in our culture, and so I tried to use terms that were less ambiguous. Not incidentally, I wanted as well to signal my debt to the Russian Formalist literary critics, perhaps our first modern narratologists.

Other chapters of Poetics of Cinema are posted online here.

P.S. 14 January 2014: Thanks to Steve Hilby for correcting me: I originally mis-identified Jordan’s car as a Ferrari.

P.S.S. 14 January 2014: My old friend Brian Rose signals his Academy interview with the filmmakers, in which Scorsese and Schoonmaker declare a lack of interest in “plot.” Pfui, says I.

Twice-told tales: MILDRED PIERCE

Mildred Pierce (1945).

DB here:

At the climax of Now You See Me, a barrage of brief shots skips back in time to show how our quartet of magicians pulled off the complicated illusion we’ve just seen. (A very, very complicated illusion, in fact. You and I should be so lucky.) Soon our Four Horsemen come to realize that a puppetmaster behind the scenes has been steering them, and this awareness comes in another flurry of flashbacks.

Today’s movies are constantly using fragmentary flashbacks to fill in elements left out of earlier scenes. I recently considered how Safe Haven and Side Effects use the convention, but lots of other films will furnish examples. Crucial to this technique is an illusion created by cinematic narration. The first time through a scene, we think we’re seeing everything. But the replay shows us bits and pieces that were left out, or that we didn’t notice, or that we’ve forgotten about.

Back in 1992 I wrote an essay about this technique. “Cognition and Comprehension: Viewing and Forgetting in Mildred Pierce” focuses on the murder of Monte Beragon in the 1945 film. A revised version of the essay appears in Poetics of Cinema and is now available on this website. The piece tries to show that a cognitive approach to comprehension and recollection can explain how a film shapes viewers’ responses—in this case, creating mystery while making viewers forget certain things they’ve seen.

Today I’m going to consider Mildred again, but by doing something I couldn’t do in print. The wonders of the Internetz let me use video extracts to show concretely how clever this replay is. I frame my case here differently than in the earlier piece, although there are ideas and examples common to both. Perhaps what I do here will tease you into reading the more technical essay.

And of course there are spoilers—most thoroughly in reference to Mildred, more mildly in reference to Side Effects and The Unfaithful (1947).

Hiding murder

At the start of Mildred Pierce we see Monte shot down in a beach house, but we don’t see who did it. At the climax of the film, we’ll see a flashback replay the murder, filling in elements that were suppressed in the earlier version. In these sequences, director Michael Curtiz and the film’s screenwriters make choices about at least three narrative conventions.

How do you present the original scene? How do you handle the flashback? How do you present the replay?

These choices confront every screenwriter or director who wants the Aha! effect of dramatically revealing what was really happening in an earlier sequence.

The filmmakers’ decisions will be shaped by the urge to make the audience’s pickup fast and effortless. The filmmakers know that we tend to want to cut to the core of a story situation, to grab its gist and move on, and we trust that the film’s unfolding will help us do that. But this very speed can work against us. By counting on our knowledge of conventions, filmmmakers can encourage us to jump to conclusions that will turn out to be inaccurate.

Start with the handling of the original scene. Your choices are basically these: We can see the action fully, or we can see it only partially, with some aspects suppressed. Consider the opening of The Letter (1940). Leslie Crosbie strides out of a cottage, blasting away at a man who tries to crawl away from her.

We see the crime fully, so the mystery involves circumstances. What led up to this murder? The rest of the film’s plot will concentrate on that.

Alternatively, some element of the initial scene can be omitted. This is what we get in the shooting of Miles Archer near the start of The Maltese Falcon (1941).

It’s familiar territory. The film’s narration conceals the identity of the killer by framing him or her out of the shot. The question of who killed Archer will propel part of the action to come.

The crucial action can be suppressed even more thoroughly. In The Accused (1947), a woman is followed into her home. We already know her as a wealthy wife waiting for her husband to come home, but we aren’t shown the identity of the shadowy male figure who grabs her and forces his way into the house.

And the camera stays obstinately outside while someone is shot in the house.

Only later will we find out who the victim is, and the entire film will slowly reveal what really happened inside, and what led up to it.

I’ll have some things to say about Mildred’s initial murder scene shortly, but now let’s consider the second key convention: the flashback device itself. What is a flashback? Most basically, it involves presenting earlier story events in the midst of later ones. It’s often motivated as a memory, as when a woman recalls her childhood. But there doesn’t have to be a memory motivation; the film’s narration can directly show us bits of action that occurred in the past (as in the “objective” flashbacks in Kubrick’s The Killing).

Mildred Pierce is built on three flashbacks. Two long ones explain the course of her life with her family, and a final one dramatizes Mildred’s explanation of what happened during Monte’s murder.

What, then is a replay, the third convention I’m considering? I don’t think critics and filmmakers have a very stringent sense of this device. (See the codicil for further comments.) I’d suggest that basically a replay is a flashback that revisits scenes we’ve already seen. When our heroine recalls her childhood in scenes we didn’t see before, we have a flashback. But if later in the film we see those childhood scenes again, I’d call it a replay. Centrally, a replay revisits scenes we’ve already witnessed, or at least glimpsed.

So not all flashbacks are replays. Are all replays flashbacks? Some would say yes, but I’m more cautious. I’m inclined to say that a mechanical recording of a scene shown earlier could count as a replay without being a flashback. In Rebecca the newly-married couple watches home movies of their honeymoon. This scene fulfills the function of a flashback, but the action we see remains in the present: the couple are screening the film. The footage doesn’t show scenes we’ve already seen, but if it had, I’d call the screening of the movies a replay, but not a flashback—since, again, the action framing it is visible in the present.

This sort of mechanical recording/ replay is very common in modern films, reflecting the ubiquity of surveillance cameras, cellphones, and the like. In an earlier blog entry I talked about a purely auditory replay in Sudden Fear that’s made possible by an audio recording device. It would be odd to call the home movies or the SoundScriber playback flashbacks.

So some replays are flashbacks, and some aren’t. When they’re flashbacks, replays are often used subjectively, as when a character remembers an earlier action. Recall all those dream sequences that present, often with distorted imagery or sound, action we’ve seen previously in the film. But a replay may also supply new information about actions we already witnessed and thought we understood. We thought we grasped an earlier scene because nothing signaled to us that pieces of information were missing.

This possibility goes to another creative option. Sometimes the film tells us that something has been omitted. In my Maltese Falcon and Unfaithful examples, the narration is openly suppressive: It announces that it’s not telling us certain things. This of course adds mystery to the plot.

Alternatively, the presentation of the initial scene might be covertly suppressive; it hides things and doesn’t tell us it’s hiding them. In Side Effects, we see the heroine commit murder and then go to bed. Later the murder scene is replayed, but with extra shots showing actions we didn’t see or surmise before. The idea of replaying to fill in previously suppressed information is quite old; you can see it at work in Griffith’s Romance of Happy Valley and Ford’s Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. In modern cinema, we sometimes revisit an earlier scene several times, with each pass yielding new information (e.g., Go). You might want to call these “multiple-draft replays.”

Gunplay and replay

We start with two establishing views of the beach house, with a car outside. Over the second, gunshots are heard. Shot by an unknown assassin, Monte staggers forward and falls back onto the carpet. A close shot shows him saying, “Mildred” as he dies.

The camera tracks to the bullet-riddled mirror and we hear the sound of a a door. A new shot lingers on Monte’s corpse. We then see the car drive off.

The next scene shows Mildred pacing nervously on the pier.

I think that this opening lays out two options, one for the trusting viewer and one for a more skeptical one. The trusting viewer assumes that Mildred killed Monte. He seems to glance at her as he speaks her name, and the shot of the car pulling away leads smoothly to the sequence showing Mildred on the pier.

Not so fast, says the skeptical viewer. If Mildred did it, why doesn’t the film show her doing it, as the Letter scene does? The absence of a reverse shot of the killer resembles the missing reverse shot in the Maltese Falcon scene. So the scene leaves some doubt about whether Mildred is guilty.

The film rushes us along, so we aren’t obliged to decide one way or the other. Eventually we can reconcile the opening with either possibility. If Mildred turns out to be innocent, we can say the film played fair by not showing the killer. If she turns out to be guilty, the missing reverse shot will be seen as simply a device to postpone telling us.

She certainly acts guilty enough in what follows. On the pier, she seems to consider leaping into the surf, only to be put off by a cop on a beat. The lubricious Wally lures her into his tavern, where she stares coldly at him before suggesting they go to the beach house. There, she locks him in, and he discovers Monte’s corpse.

Passing policemen in a patrol car see Wally break out of the house and arrest him on the beach. Mildred’s daughter Veda is briefly introduced at their home, when two policemen come to take Mildred in for questioning. She seems to feign ignorance of Monte’s death, still trying to frame Wally.

At the headquarters, the police inspector announces that they have the killer—not Wally but Mildred’s first husband Bert. Distraught, she claims Bert is innocent and to exonerate him she tells her story, taking us through her two marriages and her successful career.

At the climax of Mildred’s second flashback, she realizes that Monte’s free-spending ways have enabled Wally to cheat her out of her restaurant chain. She fetches a pistol and drives to the beach house, in a framing that reminds the first-time viewer of the film’s opening shots.

We see her walk through the house, but then the flashback breaks off. We’re taken back to the present, with her talking to the chief detective. “Monte was alone, and I killed him.” The detective replies that she’s lying; someone else was in the house. Who? Not Bert but Veda, brought in by the cops who have grabbed her when she tried to leave town.

Before Mildred can hush her, Veda snaps out, “You promised not to tell! You promised! You said you’d help me get away!” Veda became increasingly important to the plot as the years went by in Mildred’s flashbacks, but her almost total absence from the opening minutes blocks our thinking of her as a candidate for the killer’s role. Soon we’ll see the pains the narration took to make sure we didn’t spot her at the crime scene.