Archive for the 'Film theory: Cognitivism' Category

Pleased to meet you. What’s the greatest movie ever made?

(From the Seth Saith blog)

Kristin here:

Way back in January Jim Emerson participated in the “Movie Tree House” conversation on Sergio Leone and the Infield Fly Rule. On January 14, his blog recounted his discussion of the differences between “average viewers” and those of us who are more intensely involved in films in one way or another:

I met a very nice, intelligent woman (maybe ten years older than me) at a New Year’s Eve party and she told me “The King’s Speech” was the best movie she’d ever seen. I responded politely by showing (genuine) enthusiasm for Geoffrey Rush’s performance. But I don’t know what to say to something like that. I mean, I had no reason or desire to dismiss her, but it wasn’t the kind of statement that calls for critical analysis, either. It was just social small talk. But I believe she was quite moved by the film. And, yes, there’s nothing at all wrong with that.

He added:

I thought of saying, “Wow. My favorite movie is ‘Nashville.’ Or maybe ‘Chinatown.’ Or ‘Only Angels Have Wings.'” But I didn’t think the conversation would have much opportunity to go anywhere from there, so I didn’t.

I suspect Jim’s experience is common among people whose main vocation is writing about films. When I meet someone who isn’t a film buff or scholar, he or she almost inevitably asks one of two questions: “What is your favorite film?” or “What do you think is the greatest film ever made?” From the looks on their faces, I suspect they really want to know the answer and think that it will be interesting, even gratifying. After all, meeting a film critic or historian is less common and more potentially interesting than meeting a mathematician.

Up to now, I have generally answered honestly that I think the greatest film ever made is Jacques Tati’s Play Time and that it’s probably my favorite as well. Or I say that it’s hard to choose, but some candidates would be  Ozu Yasujiro’s Late Spring, Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game, Sergei Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible, and Play Time. Almost invariably the smile on my interlocutor’s face fades into disappointment as he or she admits to never having heard of any of these films, let alone having seen them. Awkward pause, with conversation turning to other matters or my making a feeble attempt to say sometime to encourage the person to give these films a try.

Ozu Yasujiro’s Late Spring, Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game, Sergei Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible, and Play Time. Almost invariably the smile on my interlocutor’s face fades into disappointment as he or she admits to never having heard of any of these films, let alone having seen them. Awkward pause, with conversation turning to other matters or my making a feeble attempt to say sometime to encourage the person to give these films a try.

I think I’ve come up with a better way to answer these questions. I’ll say something like, “Well, lately I’ve really enjoyed True Grit and Toy Story 3.” This dodges the question, but the person is bound to have heard of these, likely to have seen one or both, and may well have something to say about them—though I hope it isn’t “Yes, that’s the best film I’ve ever seen.”

Maybe that tactic will work. After all, most movie-goers work on what in cognitive psychology is called “the recency effect.” Our memories of things we’ve just experienced are more vivid in our minds than those from longer ago, even though those older experiences may have seemed equally intense or pleasurable at the time.

I ran across a good example of this effect in an Amazon review of True Grit posted by Harold Greene. Giving the film five stars, he enthuses, “I am reluctant to declare it THE best movie I have ever seen in my life but in five weeks watching it every Saturday night I can recall none to surpass it.” As a fan of True Grit and the Coen Brothers, I would believe that possibly it is the best film Mr. Greene has ever seen. But it could equally be that the intense repetition of viewings may have solidified the recency effect and diminished his memory of other films that he esteemed equally at the time.

More generally, the recency effect tends to be borne out when one of my colleagues in film studies here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison surveys their students at the beginning of a course. The goal is to find out something about their knowledge of film going into the class. One question, “What is your favorite film?” almost invariably elicits a title released in the past year or so.

So I suspect that the party-goer asking about my favorite film would be satisfied with my talking about recent movies I’ve enjoyed. The real puzzle, though, is why such people would ask such questions to begin with.

One possibility is that most people have very little sense that there is a vast body of movies out there, from over a century and from many significant filmmaking countries. Their impression of film history, as reflected in the popular media, could reasonably be that the film I might name as the greatest is probably one they’ve heard of, maybe Casablanca or Citizen Kane or The Godfather or La Dolce Vita or even Avatar.

Could it be that my questioner is hoping, probably without realizing it, that I will name his or her own favorite film? Or at least a title that he or she has seen and enjoyed? Or at least heard of? In the latter case, the person can hold up his or her side of the conversation by responding, “Oh, I’ve heard of that and have been meaning to watch it. I must put it in my Netflix queue.” A satisfactory conclusion to that little stretch of social interaction, and it does happen, albeit rarely.

I try to imagine whether scholars of opera or poetry get such questions at parties. Does someone who has just been introduced to them ask what their favorite opera or poem is? Maybe. I wouldn’t. My typical response on learning that a perfect stranger standing in front of me is a professor of something is to ask what his or her area of specialization is, hoping that it’s something I know a bit about (Vivaldi operas as opposed to Verdi, nineteenth-century Victorian novels as opposed to Renaissance poetry).

to Verdi, nineteenth-century Victorian novels as opposed to Renaissance poetry).

I have to admit, some people I meet at parties do launch in by asking me what areas of film I study, which makes the subsequent conversation less likely to end in mutual embarrassment. That is, with me looking like a pointy-headed, ivory-tower intellectual who wouldn’t be caught dead watching Cedar Rapids (which I’m actually looking forward to seeing) and my new acquaintance looking like an ignorant clod who doesn’t look beyond this year’s Oscar nominees (even though he or she has probably in reality seen quite a lot of excellent movies).

This entry on Jim’s blog led to a touchy exchange in his comments section about whether he and the other participants in the dialogue were being condescending to “average viewers.” This sort of disagreement seems inevitable, since people who know a great deal about any subject are likely to seem condescending to people who don’t, even if that is not their intention. But the question I’m asking is not whether “average viewers” have good taste. Some do, some don’t. So far I’ve just been trying to figure out why many of them seem determined to ask experts questions that will very likely expose their own lack of knowledge.

Beyond that issue, though, is the symptomatic implication of these two nearly universal cocktail-party questions. I think people are more apt to ask “What do you think the greatest film is?” than “What do you think the greatest opera is?” because film is still taken less seriously as an art-form than are the “high” arts. Most people think they know more about film than they do about opera because almost anyone you and I are likely to meet goes to movies more than to operas. The fact that a steady diet of well-reviewed, even Oscar-nominated Hollywood films remains only a tiny slice of the entire range of surviving movies made so far doesn’t occur to them. The same is true even for those who see the occasional indie or foreign-language film.

It used to be that a good liberal-arts education gave a young person a solid foundation in fields like music and art. I took two four-credit semesters of classical-music appreciation as a freshman and have benefited ever since. I took literature courses, and although I took only one semester of art appreciation, I have filled in by visiting museums all over the world. Even so, I would be cautious in trying to make conversation about topics like ballet, which I realize I know very little about.

Yet, the “What’s your favorite film?” question doesn’t just come from neighbors I see only at the annual block-party potluck or over bed-and-breakfast buffets. It comes from college professors who themselves are often specialists in one of the arts. They probably would feel, as well-rounded intellectuals, required to know at least something about the other arts—except film.

David was once talking with a distinguished literary scholar who would have been appalled if someone in a university had never heard of Faulkner or Thomas Mann. But when David said he admired many Japanese films, the scholar asked incredulously, “All those Godzilla movies?”

That’s really the crux of what bothers me about the awkward great-film/favorite-film question. If it’s a non-academic who asks it, it tends to be a conversation-stopper, which is unfortunate. But anyone is entitled to love the movies they want to love and to believe, if they wish, that Avatar is the greatest film ever made.

But when academics who would claim to be well-educated in the arts look blank when I mention The Rules of the Game or one of the other likely masterpieces of world cinema, I do mentally pass judgment. Is it more important to be aware of Monteverdi’s Orfeo or Velasquez’s Las Meninas than of Renoir’s film? Obviously I would say no. Yet I don’t think that these academics feel particularly embarrassed at not recognizing the title of a mere film.

This is not to say that all liberal-arts academics in other fields are ignorant of film and its history. On the contrary, we have friends who certainly know as much about the subject as we do about any other art form. But on the whole, in-depth knowledge of film is fairly uncommon across the campus. There are physicists who play piano sonatas and biologists who love painting, but those typically aren’t the people showing up for our Cinematheque screenings. The question isn’t merely one of taste either. In universities, people in the other arts vote on funding for film programs. If they deep down consider film a lesser art form and hence an inconsequential subject of study, we can expect less support, or perhaps the sort of condescending support that says, in effect, “Well, I suppose that since it’s popular with students we should go ahead . . .”

A final note. If anything I have said here sounds “elitist,” you might consider the vast movement we see occurring in this country’s politics, especially on the far right, where any learning at all is equated with elitism and any experience in public office is equated with being tainted. When our educational system is being systematically downgraded, expecting people to learn things is simple common sense.

More work for the eyes

DB here:

While in NYC I’ve been catching up with old friends, eating too much, and seeing movies. In my next entry I hope to write about movies and some venues showing same.

In an earlier blog, I wrote about research into the ways our eyes scan pictures. In his blockbuster follow-up Tim Smith shared his current research into tracking viewers’ eye movements when they watch a movie scene. Today, I go back to still images, inspired by a couple of visits to the place where Kristin is finishing up her fellowship, the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

3D or 2D?

Sculpture, we say, is three-dimensional and painting is two-dimensional. That’s mostly true, but in the case of relief carving we have something in between. Consider the above nifty Egyptian shallow relief from the mid-fourteenth century BCE, the Amarna period, discovered in Memphis. A servant is force-feeding some cattle. As an effect of the lighting and the carving, his foot protrudes a bit from the overlapping surfaces behind him.

On a lesser scale, the same thing can happen with paintings. We commonly say that paintings are flat, relying on pictorial cues to suggest depth. But paint applied to a surface has its own thickness, a quality that is largely lost in reproductions. One of the virtues of seeing a painting in the flesh is that you can study (at least as closely as the guard ropes allow) the subtle ways in which even a little dab of paint can give the painting a tangible depth, sort of 2D plus.

I first noticed this, I think, when I saw José de Ribera’s Holy Trinity (1636) in the Prado many years ago.

The painting wasn’t under glass, so I could see that Ribera had made Christ’s wound horrifying by laying a scab of paint on the picture surface. It was as if the canvas itself were bleeding. (More generally, that trip to the Prado convinced me that Dali’s work, and the Andalusian Dog film, made a lot more sense after you saw Spanish baroque art.)

So at the Met last week I was inclined to keep my eye out for bits of paint that seem to lie on top of other patches. I was rewarded initially when I visited Vermeer’s great Allegory of the Faith (1670-1672). This has provoked many questions as to whether Vermeer used a camera obscura in planning, drawing, or even painting his images. Some claim to find the camera booth reflected in the crystal ball hanging over the lady’s head.

Peering at the tapestry curtain on the far left edge, I was gratified to find white speckles dappling it.

Some scholars propose that these stipples are the specular reflections that an optical instrument like the camera obscura create. Robert Huerta proposes, though, that these signature devices are used in a variety of ways in Vermeer’s paintings, often suggesting surface texture. Here, they are present only on the fabric, not in other areas of the painting; they stop at the curtain’s edge. Are they then Vermeer’s effort to represent needlework, slight bumps on the surface of the curtain? I have to leave it to experts.

I’m more confident about what I saw in looking at Rembrandt’s Aristotle with a Bust of Homer (1653).

It’s a very big picture, nearly six feet high, but again my eye was caught by a detail. While Aristotle’s left hand rests against his elaborate belt, his pinky ring, a sharp, highlighted strip of paint, seems to protrude from the canvas.

The slight pop-out effect probably comes partly from the hard-edged ring set against the sketchy hand. Still, as far as I could tell, the dabs of paint sit on top, a thin layer of golden light. The ring’s gleam lights up the bottom corner of the picture. It works better than many 3D movie effects I’ve seen.

Misdirection

More amateur art appreciation, this time tied to our earlier theme of where you look in an image. There’s plenty of detail to study in Georges de La Tour’s The Fortune Teller (probably 1630s).  For one thing, we get a powerfully illusionistic representation of brocade in the sash of the wizened fortune-teller (right). However, what grabbed me was the composition of the drama. A somewhat condescending young man is paying the old woman, stereotyped as a gypsy, to have his fortune told. But the women surrounding him are her confederates. One woman is stealing his purse, the other is snipping off a medallion. The theft might be more evident to you looking at this tiny image, but the picture is so large (about 40 inches by 48 inches) that a gallery visitor must scan it in great saccadic sweeps. So I’d hypothesize that in front of the picture you don’t spot the grift right away.

For one thing, we get a powerfully illusionistic representation of brocade in the sash of the wizened fortune-teller (right). However, what grabbed me was the composition of the drama. A somewhat condescending young man is paying the old woman, stereotyped as a gypsy, to have his fortune told. But the women surrounding him are her confederates. One woman is stealing his purse, the other is snipping off a medallion. The theft might be more evident to you looking at this tiny image, but the picture is so large (about 40 inches by 48 inches) that a gallery visitor must scan it in great saccadic sweeps. So I’d hypothesize that in front of the picture you don’t spot the grift right away.

I think that the painter has engineered a pretty game of misdirection. He has used cues that draw our eyes to one area of the frame and so one aspect of the drama, the exchange of glances, before letting us explore the frame to detect the pocket-picking. Several bottom-up, stimulus-driven cues work together to draw us toward the top half of the picture.

Framing is a major cue. When a picture cuts off the human body at the thigh or crotch we’re steered to the upper area of the frame. That’s where the action is likely to be; knees aren’t usually as expressive as heads.

Faces, as Tim’s analysis shows, are magnets for our attention, and the painter exploits this. The two women’s heads on the far left are played down: one is turned away, the other, with a neutral expression, is in profile and semidarkness. Her glance directs us to study the slightly suspicious expression of the youth and the edgy gaze of the central woman, and then imagine a drama played out. The head positions of the two central figures represent a compromise between readability (frontality is a strong attention-getter) and realism (people do share gazes). But the painter profits from the compromise by letting man and woman, facing front, move their eyes shiftily, raising the atmosphere of suspicion. The almost grotesque face of the fortune teller, a richer brown than those near her, also attracts our notice.

Another powerful cue is horizon-line isocephaly. The term is a mouthful, but the idea is worth knowing about. This common Renaissance technique places several heads, regardless of their distance from us or one another, along the same plane. It’s especially marked here because even the eyes of three figures fall almost exactly on the same line.

Centering in the picture format works to make the gesture of exchanging money very important. With the expressive hand gestures, we seem to have a complete story: The skeptical youth, dirt under his fingernails, has just paid the fortune-teller, who may be crossing his palm with silver in the course of her predictions.

There are other cues that keep our eyes exploring the upper half of the frame, such as the streak highlighting the hot-pink blouse. But all are merely decoys delaying our noticing the covert action in the bottom half of the image, the activity carried out entirely by hands.

Hands are normally areas of high information content, second only to faces, I suppose. But the michievous hands of the pickpockets are low in the frame, one is in shadow, and both are subordinated not only to the faces but also to the more expressive hands just above: one on a hip, two gesturing around the coin.

It’s as if there are three layers: the heads, the hands executing the business transaction, and the hands underneath doing the real business. The third level harbors something still more covert. Only on several passes did I notice that the second, profiled woman on the left has her hand ready to receive the purse from the woman lifting it.

There’s a lot else to admire here, not least the way that the two women on the left seem to merge into one two-headed pickpocket, thanks to the shared contours, their orange vests, and the angle of the first woman’s arm.

I wish Tim or someone would try eye-scanning on this picture. In what order do viewers sample the layout? Do some viewers never look below and realize what’s going on?

In any case, my example shows the importance of top-down thinking. Recently preoccupied with eyes (in The Social Network) and visual scanning, I’d naturally be drawn to this image. I wouldn’t even care if it was the fake it’s sometimes claimed to be. But even that speculation involves top-down conceptual testing! If we entertain the prospect that The Fortune Teller was painted in the 1920s, then we might be inclined to see its cunning misdirection, and perhaps even the “cubistic” merger of the two women on the left, as influenced by modern art’s spatial ambiguities.

Bottom-up and top-down perception work smoothly together. The eye is sensitive to both stimuli and stored concepts; it’s driven by the environment and by the brain. The interplay of the two should fascinate anyone interested in cinema, which is at least partly a visual art.

PS 1 March: Tim Smith, our guest blogger last month, writes to remind me that the book I discussed in an earlier post, Land and Tatler’s Looking and Acting, makes reference to another famous de La Tour painting, The Cheat, and an eyescan study of it by Iain Gilchrist. The zigzag pattern of fixations suggests that people did indeed start with the faces of the players before discovering the cheating that’s going on. Eyescans of the painting are analyzed in John M. Findlay and Iain Gilchrist’s Active Vision: The Psychology of Looking and Seeing. Gilchrist discusses the painting in a fascinating illustrated lecture.

Some readers of my entry above have wondered if eyescan experiments could study how magicians misdirect us. Tim recommends Gustav Kuhn’s work on this problem, to which I can add this article: Peter Lamont, John M. Henderson, and Tim J. Smith, “Where Science and Magic Meet: The Illusion of a ‘Science of Magic,'” Review of General Psychology 14, 10 (2010), 16-21.

Watching you watch THERE WILL BE BLOOD

DB here:

Today’s entry is our first guest blog. It follows naturally from the last entry on how our eyes scan and sample images. Tim Smith is a psychological researcher particularly interested in how movie viewers watch. You can follow his work on his blog Continuity Boy and his research site.

I asked Tim to develop some of his ideas for our readers, and he obliged by providing an experiment that takes off from my analysis of staging in one scene of There Will Be Blood, posted here back in 2008. The result is almost unprecedented in film studies, I think: an effort to test a critic’s analysis against measurable effects of a movie. What follows may well change the way you think about visual storytelling.

Tim’s colorful findings also suggest how research into art can benefit from merging humanistic and social-scientific inquiry. Kristin and I thank Tim for his willingness to share his work.

Tim Smith writes:

David’s previous post provided a nice introduction to eye tracking and its possible significance for understanding film viewing. Now it is my job to show you what we can do with it.

Continuity errors: How they escape us

Knowing where a viewer is looking is critical to beginning to understand how a viewer experiences a film. Only the visual information at the centre of attention can be perceived in detail and encoded in memory. Peripheral information is processed in much less detail and mostly contributes to our perception of space, movement and general categorisation and layout of a scene.

The incredibly reductive nature of visual attention explains why large changes can occur in a visual scene without our noticing. Clear examples of this are the glaring continuity errors found in some films. Lighting that changes throughout a scene, cigarettes that never burn down, and drinks that instantly refill plague films and television but we rarely notice them except on repeated or more deliberate viewing. In my PhD thesis I created a taxonomy of continuity errors in feature films and related them to various failings during pre-production, filming, and post-production.

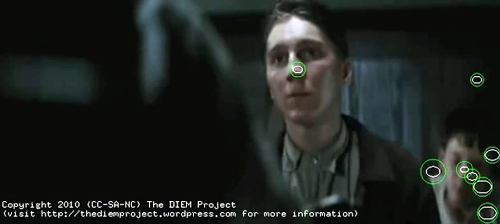

Our inability to detect continuity errors was elegantly demonstrated in a study by Dan Levin and Dan Simons. In their study continuity errors were purposefully introduced into a film sequence of two women conversing across a dinner table. If you haven’t seen it before, watch the video here before continuing, and see how many continuity errors you can spot.

Two frames from the clip used by Levin and Simons (1997). Continuity errors were deliberately inserted across cuts (e.g., the disappearing scarf), and viewers were asked after watching the video whether they noticed any.

The short clip contained nine continuity errors, such as a scarf that changed colour, then disappeared, plates that changed colour and hands that changed position. During the first viewing, viewers were told to pay close attention but were not informed about the continuity errors. When asked afterwards if they noticed anything change, only one participant reported seeing anything and that was a vague sense that the posture of the actors changed. Even during a second viewing in which they were instructed to detect changes, viewers only detected an average of 2 out of the 9 changes and tended to notice changes closest to the actors’ faces such as the scarf.

Although Levin and Simons did not record viewer eye movements, my own experiments investigating gaze behaviour during film viewing indicate that our eyes will mostly be focussed on faces and spend virtually no time on peripheral details. If you as a viewer don’t fixate a peripheral object such as the plate, you are unable to represent the colour of the plate in memory and can, therefore not detect the change in colour when you later refixate it.

Tracking gaze

To see how reductive and tightly focused our gaze is whilst watching a film, consider Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood (TWBB; 2007). In an earlier post, David used a scene from this film as an example of how staging can be used to direct viewer attention without the need for editing.

The scene depicts Paul Sunday describing the location of his family farm on a map to Daniel Plainview, his partner Fletcher Hamilton, and his son H.W. The entire scene is treated in a long, static shot (with a slight movement in at the beginning). Most modern film and television productions would use rapid editing and close-up shots to shift attention between the map and the characters within this scene. This frenetic style of filmmaking–which David termed intensified continuity in his book The Way Hollywood Tells It (2006)–breaks a scene down into a succession of many viewpoints, rapidly and forcefully presented to the viewer.

Intensified continuity is in stark contrast to the long-take style used in this scene from TWBB. The long-take style, which was common in the 1910s and recurred at intervals after that period, relies more on staging and compositional techniques to guide viewer attention within a prolonged shot. For example, lighting, colour, and focal depth can guide viewer attention within the frame, prioritising certain parts of the scene over others. However, even without such compositional techniques, the director can still influence viewer attention by co-opting natural biases in our attention: our sensitivity to faces, hands, and movement.

In order to see these biases in action during TWBB we need to record viewer eye movements. In a small pilot study, I recorded the eye movements of 11 adults using an Eyelink 1000 (SR Research) eyetracker. This eyetracker uses an infrared camera to accurately track the viewer’s pupil every millisecond. The movements of the pupil are then analysed to identify fixations, when the eyes are relatively still and visual processing happens; saccadic eye movements (saccades), when the eyes quickly move between locations and visual processing shuts down; smooth pursuit movements, when we process a moving object; and blinks.

Eye movements on their own can be interesting for drawing inferences about cognitive processing, but when thinking about film viewing, where a viewer looks is of most interest. As David demonstrated in his last post, analysing where a viewer looks whilst viewing a static scene, such as Repin’s painting An Unexpected Visitor, is relatively simple. The gaze of a viewer can be plotted on to the static image and the time spent looking at each region, such as a characters face or an object in the scene can be measured.

However, when the scene is moving, it is much more difficult to relate the gaze of a viewer on the screen to objects in the scene. To overcome this difficulty, my colleagues and I developed new visualisation techniques and analysis tools. These efforts were part of a large project investigating eye movement behaviour during film and TV viewing (Dynamic Images and Eye Movements, what we call the DIEM project). These techniques allow us to capture the dynamics of gaze during film viewing and display it in all its fascinating, frenetic glory.

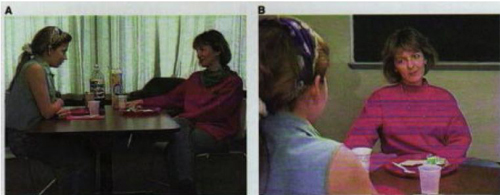

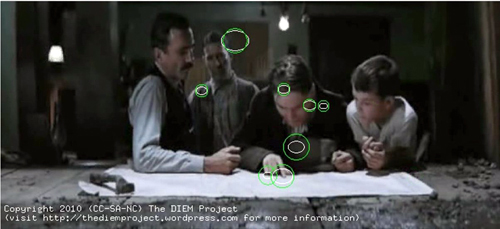

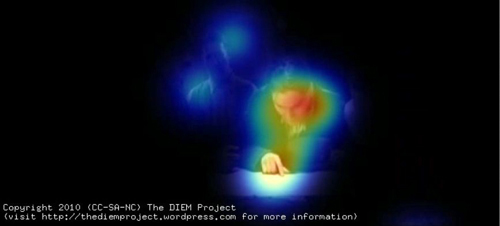

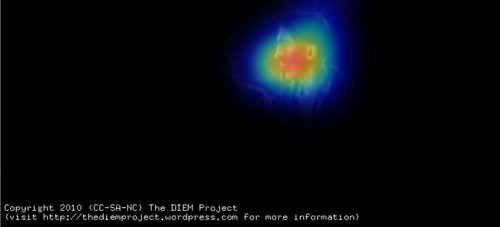

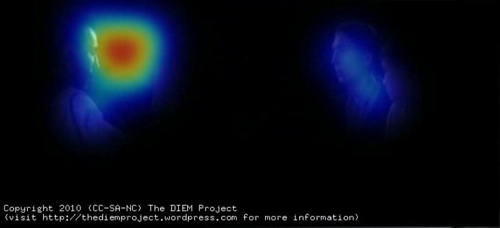

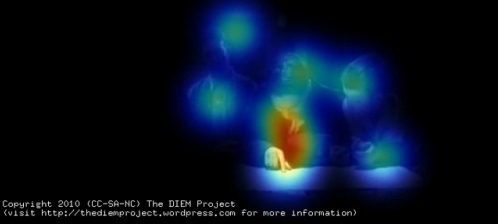

To begin, the gaze location of each viewer is placed as a point on the corresponding frame of the movie. The point is represented as a circle with the size of the circle denoting how long the eyes have remained in the same location, i.e. fixated that location. We then add the gaze location of all viewers on to the same frame. Although the viewers watched the clip at different times, plotting all viewers together allows us to look for similarities and differences between where people look and when they look there. This figure shows the gaze location of 8 viewers at one moment in the scene. (The remaining 3 viewers are blinking at this moment.)

A snapshot of gaze locations of 8 viewers whilst watching the “map” sequence from There Will Be Blood (2007). Each green circle represents the gaze location of one participant, with the size of the circle indicating how long the eyes have been in fixation (bigger equals longer).

You have a roving eye

Plotting static gaze points onto a single frame of the movie allows us to see what viewers were looking at in a particular frame, but we don’t get a true sense of how we watch movies until we animate the gaze on top of the movie as it plays back. Here is a video of the entire sequence from TWBB with superimposed gaze of 11 viewers.

You can also see it here. The main table-top map sequence we are interested begins at 3 minutes, 37 seconds.

The most striking feature of the gaze behaviour when it is animated in this way is the very fast pace at which we shift our eyes around the screen. On average, each fixation is about 300 milliseconds in duration. (A millisecond is a thousandth of a second.) Amazingly, that means that each fixation of the fovea lasts only about 1/3 of a second. These fixations are separated by even briefer saccadic eye movements, taking between 15 and 30 milliseconds!

Looking at these patterns, our gaze may appear unusually busy and erratic, but we’re moving our eyes like this every moment of our waking lives. We are not aware of the frenetic pace of our attention because we are effectively blind every time we saccade between locations. This process is known as saccadic suppression. Our visual system automatically stitches together the information encoded during each fixation to effortlessly create the perception of a constant, stable scene.

In other experiments with static scenes, my colleagues and I have shown that even if the overall scene is hidden 150milliseconds into every fixation, we are still able to move our eyes around and find a desired object. Our visual system is built to deal with such disruptions and perceive a coherent world from fragments of information encoded during each fixation.

The second most striking observation you may have about the video is how coordinated the gaze of multiple viewers is. Most of the time, all viewers are looking in a similar place. This is a phenomenon I have termed Attentional Synchrony. If several viewers examine a static scene like the Repin painting discussed in David’s last post, they will look in similar places, but not at the same time. Yet as soon as the image moves, we get a high degree of attentional synchrony. Something about the dynamics of a moving scene leads to all viewers looking at the same place, at the same time.

The main factors influencing gaze can be divided into bottom-up involuntary control by the visual scene and top-down voluntary control by the viewer’s intentions, desires, and prior experience. As part of the DIEM project we were able to identify the influence of bottom-up factors on gaze during film viewing using computer vision techniques. These techniques allowed us to dissect a sequence of film into its visual constituents such as colour, brightness, edges, and motion. We found that moments of attentional synchrony can be predicted by points of motion within an otherwise static scene (i.e. motion contrast).

You can see this for yourself when you watch the gaze video. Viewers’ gazes are attracted by the sudden appearance of objects, moving hands, heads, and bodies. The greater the motion contrast between the point of motion and the static background, the more likely viewers will look at it. If there is only one point of motion at a particular moment, then all viewers will look at the motion, creating attentional synchrony.

This is a powerful technique for guiding attention through a film. But it’s of course not unique to film. Noticing points of motion is a natural bias which we have evolved by living in the real world. If we were not sensitive to peripheral motion, then the tiger in the bushes might have killed our ancestors before they had chance to pass their genes down to us.

But points of motion do not exist in film without an object executing the movement. This brings us to David’s earlier analysis of the staging of this sequence from TWBB. This might be a good time to go back and read David’s analysis before we begin testing his hypotheses with eyetracking. Is David right in predicting that, even in the absence of other compositional techniques such as lighting, camera movement, and editing, viewer attention during this sequence is tightly controlled by staging?

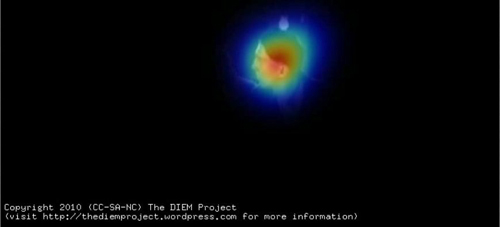

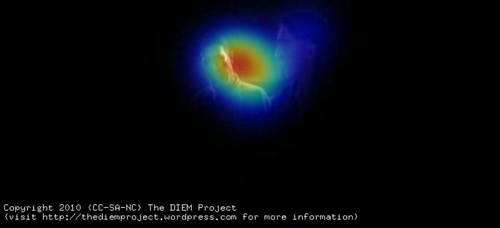

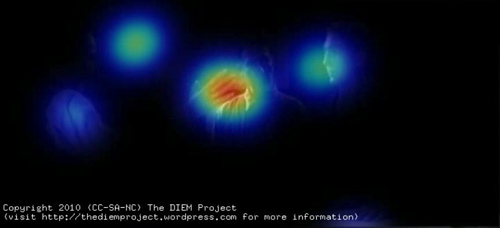

All together now

To help us test David’s hypotheses I am going to perform a little visualisation trick. Making sense of where people are looking by observing a swarm of gaze points can often be very tricky. To simplify things we can create a “peekthrough” heatmap. A virtual spotlight is cast around each gaze point. This spotlight casts a cold, blue light on the area around the gaze point. If the gazes of multiple viewers are in the same location their spotlights combine and create a hotter/redder heatmap. Areas of the frame that are unattended remain black. By then removing the gaze points but leaving the heatmap we get a “peekthrough” to the movie which allows us to clearly see which parts of the frame are at the centre of attention, which are ignored and how coordinated viewer gaze is.

Here is the resulting peekthrough video; also available here. The map sequence begins at 3:38.

Here is the image of gaze location I showed above, now matched to the same frame of the peekthrough video.

The gaze data from multiple viewers is used to create a “peekthrough” heatmap in which each gaze location shines a virtual spotlight on the film frame. Any part of the frame not attended is black, and the more viewers look in the same location, the hotter the color.

David’s first hypothesis about the map sequence is that the faces and hands of the actors command our attention. This is immediately apparent from the peekthrough video. Most gaze is focused on faces, shifting between them as the conversation switches from one character to another.

The map receives a few brief fixations at the beginning of the scene but the viewers quickly realise that it is devoid of information and spend the remainder of the scene looking at faces. The only time the map is fixated is when one of the characters gestures towards it (as above).

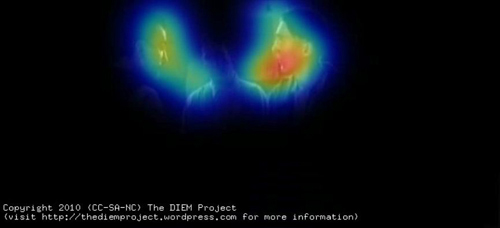

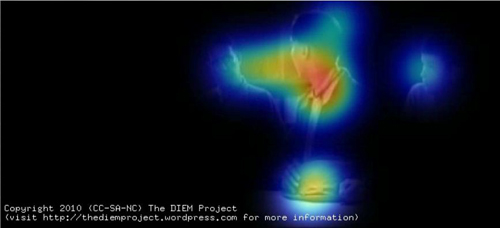

We can see the effect of turn-taking in the conversation on viewer attention by analyzing a few exchanges. The sequence begins with Paul pointing at the map and describing the location of his family farm to Daniel. Most viewers’ gazes are focused on Paul’s face as he talks, with some glances to other faces and the rest of the scene. When Paul points to the map, our gaze is channeled between his face and what he is gazing/pointing at.

Such gaze prompting and gesturing are powerful social cues for attention, directing attention along a person’s sightline to the target of their gaze or gesture. Gaze cues form the basis of a lot of editing conventions such as the match an action, shot/reverse-shot dialogue pairings, and point-of-view shots. However, in this scene gaze cuing is used in its more natural form to cue viewer attention within a single shot rather than across cuts.

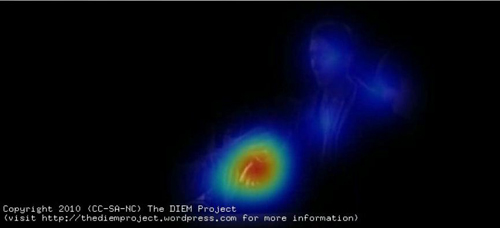

As Paul finishes giving directions, Daniel asks him a question which immediately results in all viewers shifting the gaze to Daniel’s face. Gaze then alternates between Daniel and Paul as the conversation passes between them. The viewers are both watching the speaker to see what he is saying and also monitoring the listener’s responses in the form of facial expressions and body movement.

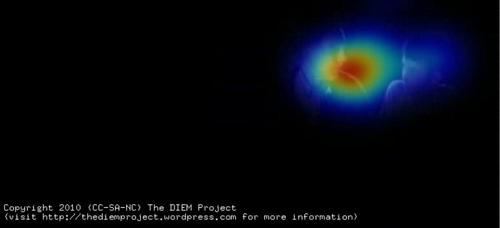

Daniel turns his back to the camera, creating a conflict between where the viewer wants to look (Daniel’s face) and what they can see (the back of his head). As David rightly predicted, by removing the current target of our attention the probability that we attend to other parts of the scene is increased, such as H. W., who up until this point has not played a role in the interaction. Viewers begin glancing towards HW and then quickly shift their gaze to him when he asks Paul how many sisters he has.

Gaze returns to Paul as he responds.

Gaze shifts from Paul to Daniel as he asks a short question, and then moves to Fletcher as he joins the conversation.

The quick exchanges of dialogue ensure that viewers only have enough time to shift their gaze to the speaker and then shift to the respondent. When gaze dwells longer on a speaker, such as during the exchange between Fletcher and Paul, there is an increase in glances away from the speaker to other parts of the scene such as the other silent faces or objects.

An object that receives more fixations as the scene develops is Paul’s hat, which he nervously fiddles with. At one point, when responding to Fletcher’s question about what they grow on the farm, Paul glances down at his hat. This triggers a large shift of viewer gaze, which slides down to the hat. Likewise, a subtle turn of the head creates a highly significant cue for viewers, steering them towards what Paul is looking at while also conveying his uneasiness.

The most subtle gesture of the scene comes soon after as Fletcher asks about water at the farm. Paul states that the water is generally salty and as he speaks Fletcher shifts his eyes slightly in the direction of Daniel. This subtle movement is enough to cue three of the viewers to shift their gaze to Daniel, registering their silent exchange.

This small piece of information seems critical to Daniel and Fletcher’s decision to follow up Paul’s lead, but its significance can be registered by viewers only if they happened to be fixating Fletcher at the time he glanced at Daniel. The majority of viewers are looking at Paul as he speaks and they miss the gesture. For these viewers, the significance of the statement may be lost, or they may have to deduce the significance either from their own understanding of oil prospecting or other information exchanged during the scene.

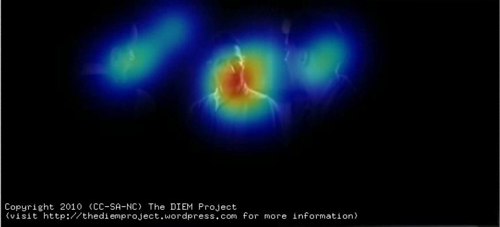

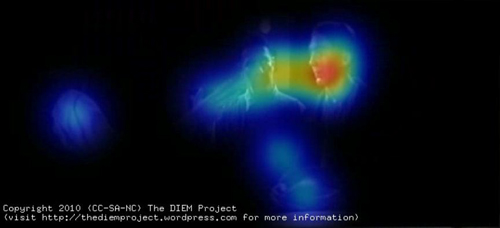

The final and most significant gesture of the scene is Daniel’s threatening raised hand. As Paul goes to leave, Daniel stalls him by raising his hand centre frame in a confusing gesture hovering midway between a menacing attack and a friendly handshake. In David’s earlier post he predicted that the hand would “command our attention.” Viewer gaze data confirm this prediction. Daniel draws all gazes to him as he abruptly states “Listen….Paul,” and lifts his hand.

Gaze then shifts quickly; the raised hand becomes a stopping off point on the way to Paul’s face. . .

. . . finally following Daniel’s hand down as he grasps Paul’s in a handshake.

We like to watch

The rapid sequence of actions clearly guide our attention around the scene: Daniel – Hand -Paul – Hand. David’s analysis of how the staging in this scene tightly controls viewer attention was spot-on and can be confirmed by eyetracking. At any one moment in the scene there is a principal action signified either by dialogue or motion. By minimising background distractions and staging the scene in a clear sequential manner using basic principles of visual attention, P. T. Anderson has created a scene which commands viewer attention as precisely as a rapidly edited sequence of close-up shots.

The benefit of using a single long shot is the illusion of volition. Viewers think they are free to look where they want but, due to the subtle influence of the director and actors, where they want to look is also where the director wants them to look. A single static long shot also creates a sense of space, clear relationship between the characters, and a calm, slow pace which is critical for the rest of the film. The same scene edited into close-ups would have left the viewer with a completely different interpretation of the scene.

I hope I’ve shown how some questions about film form, style, practice, and spectatorship can be informed by borrowing theory and methods from cognitive psychology. The techniques I have utilised in recording viewer gaze and relating it to the visual content of a film are the same methods I would use if I was conducting an experiment on a seemingly unrelated topic such as visual search. (See this paper for an example.)

The key difference is that the present analysis is exploratory and simply describes the viewing behaviour during an existing clip. What we cannot conclude from such a study is which aspects of the scene are critical for the gaze behaviour we observe. For instance, how important is the dialogue for guiding attention? To investigate the contribution of individual factors such as dialogue we need to manipulate the film and test how gaze behaviour changes when we add or remove a factor. This type of empirical manipulation is critical to furthering our understanding of film cognition and employing all of the tools cognitive psychology has to offer.

But I expect an objection. Isn’t this sort of empirical inquiry too reductive to capture the complexities of film viewing? In some respects, yes. This is what we do. Reducing complex processes down to simple, manageable, and controllable chunks is the main principle of empirical psychology. Understanding a psychological process begins with formalizing what it and its constituent parts are, and then systematically manipulating and testing their effect. If we are to understand something as complex as how we experience film we must apply the same techniques.

As in all empirical psychology the danger is always that we lose sight of the forest whilst measuring the trees. This is why the partnership between film theorists and empiricists like myself is critical. The decades of film theory, analysis, practice and intuition provide the framework and “Big Picture” to which we empiricists contribute. By sharing forces and combining perspectives, we can aid each other’s understanding of the film experience without losing sight of the majesty that drew us to cinema in the first place.

On the importance of foveal detail for memory encoding, see J. M. Findlay, Eye scanning and visual search, in The Interface of Language, Vision, and Action: Eye movements and the visual world, ed. J.M. Henderson and F. Ferreira (New York: Psychology Press, 2004), pp. 134-159. Levin and Simons’ continuity-error experiment is explained in D. T. Levin and D. J. Simons, “Failure to detect changes to attended objects in motion pictures,” Psychonomic Bulletin and Review4 (1997), pp. 501-506.

A note about our equipment and experimental procedure. We presented the film on a 21 inch CRT monitor at a distance of 90cm and a resolution of 720×328, 25fps. Eye movements were recorded using an Eyelink 1000 eyetracker and a chinrest to keep the viewer’s head still. This eye tracker consists of a bank of infrared LEDs used to illuminate the participant’s face and a high-speed infrared camera filming the face. The infrared light reflects of the face but not the pupil, creating a dark spot that the eyetracker follows. The eyetracker also detects the infrared reflecting off the outside of the eye (the cornea) which appears as a “glint”. By analysing how the glint and the centre of the pupil move as the viewer looks around the screen the eyetracker is able to calculate where the viewer is looking every millisecond.

As for the heatmaps, the greater the number of viewers, the more consistent the heatmaps. The present pilot study used gaze from only 11 viewers, which introduces a lot of noise into the visualisations. Compare the scattered nature of the gaze in the TWBB video to a similar scene visualised with the gaze of 48 viewers. We would probably see the same degree of coordination in the TWBB clip if we had used more viewers.

For a comprehensive discussion of attentional synchrony and its cause, see Mital, P.K., Smith, T. J., Hill, R. and Henderson, J. M., “Clustering of gaze during dynamic scene viewing is predicted by motion,” Cognitive Computation (in press). Social cues for attention, like shared looks, are discussed in Langton, S. R. H., Watt, R. J., & Bruce, V., “Do the eyes have it? Cues to the direction of social attention,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 4, 2, pp. 50-59. For more on our inability to detect small discontinuities, see Smith, T. J. and Henderson, J. M., “Edit Blindness: The relationship between attention and global change blindness in dynamic scenes,” Journal of Eye Movement Research (2008) 2 (2), 6, pp. 1-17.

For further information on the Dynamic Images and Eye Movement project (DIEM) please visit http://thediemproject.wordpress.com/. This research was funded by the Leverhulme Trust (Grant Ref F/00-158/BZ) and the ESRC (RES 062-23-1092). To view more visualisations from the project visit this site. The DIEM project partners are myself, Prof. John M Henderson, Parag Mital, and Dr. Robin Hill. Gaze data and visualisation tools (CARPE: Computational and Algorithmic Representation and Processing of Eye-Movements) can also be downloaded from the website. When using or referring to any of the work from DIEM, please reference the Cognitive Computation paper cited above.

Wonderful work in this area has already been conducted by Dan Levin (Vanderbilt), Gery d’Ydewalle (Leuven), Stephan Schwan (KMRC, Tübingen), and the grandfather of the recent revival in empirical cognitive film theory, Julian Hochberg. I am indebted to their pioneering work and excited about taking this research area forward.

Finally, I would like to thank David and Kristin for inviting me to describe some of my work on their wonderful blog. I have been an avid follower of their work for years and David has been a great supporter of my research.

DB PS 26 February: The response to Tim’s blog has been astonishing and gratifying. Tens of thousands of visitors have read his essay here, and his videos have been viewed over 700,000 times on sites across the Web. I’m very happy that so many non-psychologists–scholars, critics, and filmmakers–have found something of value here. The extended discussion on Jim Emerson’s scanners site, in which I participated a little, is especially worth reading. For more comments and replies from Tim and his team, go to Tim’s Continuity Boy blogpage and the DIEM team’s Vimeo page. At Continuity Boy, Tim will post more videos based on his group’s experimental efforts.

DB PS 18 October: Tim has posted a new, equally interesting experiment on tracking non-visible (!) movement on his blogsite.

The eye’s mind

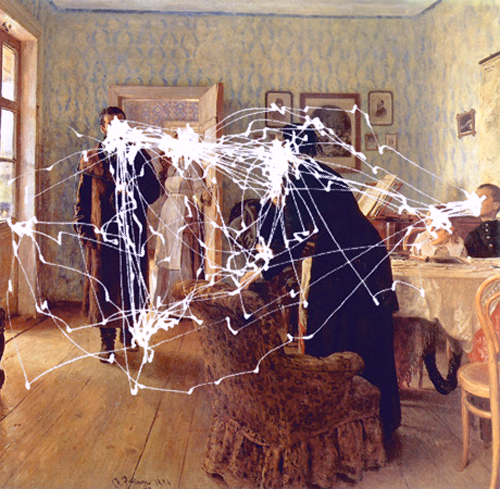

Sasha Archibald, after Alfred Yarbus, after Ilya Repin, They Did Not Expect Him (aka An Unexpected Visitor, 1884).

DB here again:

One blog about eyes deserves another–actually a couple more. These entries, however, won’t be about actors’ or characters’ eyes. They’re about yours and mine.

We use them when we watch movies, but there’s been surprisingly little talk about how we do it. Even film theorists who talk about the Gaze or Visual Culture have not devoted much time to studying how we actually see movies. The whole business is pretty complicated, I grant. But if you’re willing to start by thinking about how we use our eyes in getting through the world, and then move to thinking about how we look at pictures, we can pretty quickly gain some understanding about how we watch films. That’s the business of this entry and the next one.

Bottom-up or top-down?

Unless you’re reading this in a cyclotron or on a roller coaster (always a possibility in these days of mobile media), your surroundings seem pretty stable, no? Look up from your screen and you’ll register the continuous space of a room, or a city vista, or a landscape. What’s remarkable is that this sense of a visual environment that’s all of a piece is composed of thousands of probes. Our eyes sample our surroundings, and the pieces that we snatch somehow melt into a solid, coherent world.

Surprisingly, our eyes have a very limited ability to focus precisely. The fovea, that compact scoop of cells that registers fine detail, is very tiny (about a millimenter in diameter) and has an angular coverage of less than two degrees. Yet it’s a key conduit of information. About 50% of visual nerve fibers are dedicated to the fovea, and acuity falls off very fast beyond it. Other areas of the eye can detect grosser changes in the environment, but in order to see anything clearly, we must constantly shift our eyes to bring the fovea to bear on it. When we follow a moving object, our eyes execute what are called smooth pursuit movements. In viewing a more or less static visual array, we execute saccades, very fast jumps from one fixation to another. Vision is a matter of saccades and fixations, scanning and sampling. A striking fact about saccades is that from one fixation to the next we are mostly blind to what’s happening in the visual field.

But what guides that scanning and sampling? We usually think it’s a matter of attention, and that’s probably not far off. It’s hard to pay visual attention to something that isn’t the target of foveal fixation. When we examine something in detail, we’re clearly devoting mental resources to it, whether it’s a streaky tulip or a misplaced comma. But what triggers our attention, and thus our foveal activity, in the first place?

Commonly we say that something catches our eye, cries out to be noticed, grabs our attention. That is, something out there becomes salient, so we send a saccade to it and fixate on it to get information. This is what psychologists call a bottom-up account. A stimulus triggers our visual system, which in turn recruits our mind to make sense of what has popped out.

An example: Looking straight ahead, you’re starting to cross a street. Something registered on the periphery of your vision seems to be suddenly bearing down on you. You turn your head and look: a car isn’t slowing down for the stoplight and you involuntarily jerk yourself back out of harm’s way. The errant car was salient, your visual system kicked in, and your body obeyed—all in a flash. You might not even be able to identify the car or driver as it runs the light, and you might say: “I didn’t even have time to think about it.” This is bottom-up, stimulus-driven seeing and acting.

Contrast another way to use your eyes. You’ve parked your car outside the Mall of America. Hours later you come out, a little uncertain about where the car is. Once you get to the general vicinity you recall, you use your knowledge of the vehicle to search it out. Let’s see, silvery Toyota sedan. Hell, too many Toyata sedans, all silvery. Wait, mine has a faded Obama-Biden sticker on the bumper and a rabbit with glowing eyes in the back window. Aha, there it is. This is a mode of looking guided by ideas and prior knowledge. Here perception is top-down, idea-driven; vision is informed by what you expect, recall, or believe about the world.

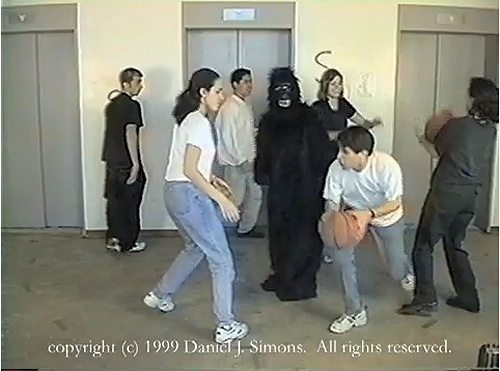

Top-down perception can focus our attention so drastically that we miss some glaringly obvious things. Consider Dan Simons and Chris Chabris’s famous basketball video experiment. If you’re not aware of this demonstration, proceed immediately to this page and take the test yourself.

Using a video of several players passing basketballs to one another, Simons and Chabris asked volunteers to silently count the passes made by players in white. But what Simons and Chabris were really testing was the extent to which people display “inattentional blindness.” About half the viewers were so preoccupied with the task assigned that they missed a rather salient item in the display: a gorilla that walks onto the court, thumps its chest, and walks off.

Simons and Chabris weren’t concerned with tracking eye movements (though later researchers have tried with the video; see the end of this piece). What the gorilla experiment indicates, however, is that top-down control has the drawback of narrowing our attentive focus so drastically that we miss the obvious. The curious phenomenon of inattentional blindness has become a robust area of research in cognitive psychology.

They did not expect…what?

We might think that visual search like the one demanded by the gorilla experiment is a special case. Isn’t most looking, including those saccades we execute all the time, bottom-up? After all, we are fairly passive, and we must take what we’re given by the world around us. Our attention is drawn to what pops out. There are a lot of features of the world that seem salient—bright colors, movement, strong contrasts, things coming toward us, and so on.

There’s another school of thought, though, and it’s articulated carefully in Michael F. Land and Benjamin W. Tatler’s Looking and Acting: Vision and Eye Movements in Natural Behavior (Oxford University Press, 2009). In ordinary life, they argue, we don’t just float though the world. We’re taken up with tasks. We walk, read, and make sandwiches. The tasks we undertake tacitly shape how and where we look and what we see. Land and Tatler want us to remember the top-down guidance of vision—the mind in the eye, so to speak.

There’s another school of thought, though, and it’s articulated carefully in Michael F. Land and Benjamin W. Tatler’s Looking and Acting: Vision and Eye Movements in Natural Behavior (Oxford University Press, 2009). In ordinary life, they argue, we don’t just float though the world. We’re taken up with tasks. We walk, read, and make sandwiches. The tasks we undertake tacitly shape how and where we look and what we see. Land and Tatler want us to remember the top-down guidance of vision—the mind in the eye, so to speak.

Their central chapters trace how our acts of looking serve two basic functions: “finding and identifying the objects needed for the various tasks and guiding the actions that make use of these objects” (p. 59). In reading and drawing, or even walking or hitting a ball, the authors show, our eyes serve our brain’s sense of what must be done moment by moment. Wearing a nifty lightweight eyepiece or pair of spectacles, the experimental subject can act quite naturally and allow her point of gaze to be tracked and recorded to video. The results show that the tasks we launch, from crossing a street to reading a piece of music, create a series of phases that our eyes recognize and help us through, all without much conscious effort.

What about pictures? We aren’t interacting with them in the way we interact with teacups and steering wheels; we can’t affect their unfolding. Do our eyes behave as they do in our ordinary activities? In 1965 the Russian psychologist Alfred Yarbus reported the results of experiments that tracked eye movements. In some of them, he used Ilya Repin’s classic painting They Did Not Expect Him (aka An Unexpected Visitor, 1884). The dramatic image depicts a hollow-eyed man, gaunt and wrapped in a patchy coat, striding into a comfortable middle-class parlor.

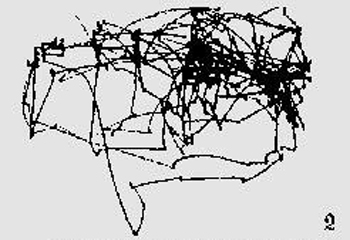

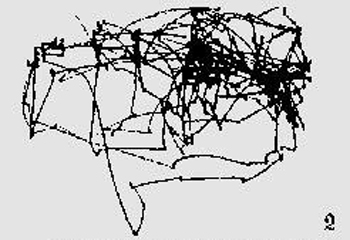

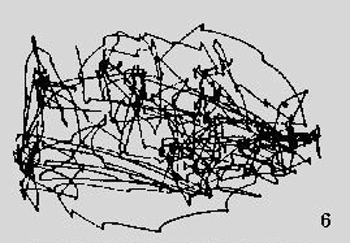

First Yarbus simply let his subjects view the picture without any instructions from him. Their saccadic patterns were typified by this subject’s result.

Each line represents the fast movement of the eyes from one location to another (saccades) and clusters of lines are the traces of fixations. The denser the lines, the longer and more often a point was fixated. Sasha Archibald’s reconstruction at the top of this entry superimposes this pattern on the original picture.

Then Yarbus tried asking his subjects questions about the image. Here is the result of his asking one subject to estimate the material circumstances of the family.

A very different trajectory of attention emerges. Now the scanning was more purposeful, and it focused on the areas most likely to fulfill the task of identifying the family’s social class–clothes, the piano, the children, and other items. Moreover, when given more time to examine the picture, subjects did not roam around every cranny of the frame but returned constantly to the areas they had already examined, the ones that were most relevant to the task. Hence the blotchy areas, which are nodes where the eyes fixated very often.

Artists often claim that color, composition, and other features attract a viewer’s attention. But Yarbus concluded that while some sorts of visual material, chiefly faces and bodies, were targeted during the undirected scanning, many other features, such as color, edges, light or dark regions, and so on were not. “The character of the eye movements is either completely independent of or only very slightly dependent on the material of the picture and how it was made. . . . Depending on the task in which a person is engaged, i.e., depending on the character of the information which he must obtain, the distribution of the points of fixation on an object will vary correspondingly” (pp. 190, 192).

Your mission in watching a movie

Generally speaking, in blocking and framing a shot, the most important thing is to make sure the audience is looking where you want them to look.

Robert Zemeckis

Like painters, film directors talk of guiding our attention, isolating this actor, throwing one plane out of focus in order to emphasize another one. And we commonly say that the movie is designed to grab our eyes and guide them through each shot. As Zemeckis’ remark suggests, directors direct actors but they also direct us; they direct our attention, and they do it by making certain things salient in each shot.

Or so we think. If Yarbus and Land and Tatler are right, are we deeply wrong about how movies work? I don’t think so, but convincing you requires that I unpack some assumptions.

First, the world doesn’t come to us in a frame. A film shot, like a still photo or a painting, is bounded by edges, and as Rudolf Arnheim and Jean Mitry have pointed out, the very existence of the frame inevitably organizes what is put inside it. It makes little sense to say that something is in the center of your visual environment—that depends on where you’re looking—but everyone will agree what is in the center of a picture. And we are very likely to look at that central area of a frame or screen; Land and Tatler call it a “bias” (p. 39).

Repin took advantage of this bias by composing the primary action around a central region. It’s not the geometrical center of the image, which falls on a fairly innocuous patch of gray near the elbow of the woman seated at the piano. But there is a cluster of heads and shoulders just above that center. Fans of the “rule of thirds” will point out the glances of the man, the women in the background, the woman at the piano, and the rising woman lie along a line marking off the top third of the picture. The frame, by being a certain shape, creates lines of force within the image, and these can attract our scrutiny.

Second, human faces are a special case. We are sublimely sensitive to them. Faces are recognized even in low-resolution images, they are detected faster than other configurations, and we readily project them into ambiguous patterns. Hence we see the Man in the Moon and the Savior on a Cheeto. Naturally, artists realize the power of faces and gestures to attract our attention. Repin’s compositional design facilitates our pickup of the human drama he presents.

Filmmakers follow suit. Knowing that faces and movements are zones of high information, directors light, frame, compose, and edit their shots so that these zones get highlighted. Indeed, we might say that today’s “intensified continuity” style of filmmaking, emphasizing singles and facial close-ups, goes with the flow, giving us a full dose of what we’d look for anyway.

Yarbus stresses the all-over quality of undirected vision, at least when compared with more specific tasks. But I’d say that the scanpaths we find in his free version line up pretty well with Repin’s compositional pattern and the pictorial roles he gave to faces, bodies, and gestures. True, there is a lot of visual search in unrewarding areas. Nonetheless, that high, slightly sloping area above the geometrical center attracts heavy traffic, as does the daringly edge-centered children on the far right. It is simply the line of least resistance, at least when all other considerations are equal.

Yarbus made other things unequal. He asked questions, which created more guided paths. Still, regardless of what task they were assigned, Yarbus’ informants seem largely to have followed the compositional path Repin laid down. Asked to estimate the ages of the people in the picture, viewers gave a tighter, simplified version of the default, undirected path. To determine ages, face and height matter; the left window and furniture didn’t have to be explored much. Here is one subject’s pattern of scanning for signs of age.

Asked to memorize the costumes, the subjects also stuck to the program, with more searching of the body areas. Here is one example.

And asked to estimate how long the visitor had been away from the family, another viewer’s gaze traces a comparably tight slope, dwelling especially on the children at the far right.

In short, Yarbus’s questions about age, clothing, and years of separation were best answered by the faces and bodies on display–exactly the areas highlighted by Repin’s composition, color, and ensemble staging. Unsurprisingly, however, if your task is to estimate the family’s wealth, you’ll probably roam to the periphery of the action, as one subject did.

And if you’re told to memorize the spatial layout–a very unusual task that you’d seldom impose on yourself–you will spread your net quite widely, as one viewer did.

Yarbus’ results suggest to me that representational pictures elicit a set of default strategies: Start from the approximate center of the format. Watch for faces and gestures and an exchange of looks. Then launch further exploration of the picture space, anchoring that to the main compositional vectors and human signals. And of course take the title into account. The “they” of They Did Not Expect Him (virtually a literal translation of the original Russian title) prompts us to look for the reactions of onlookers.

With film, of course, we have additional pointers: sound, especially dialogue; camera movement, which is constantly redirecting our attention; and figure movement, which is a powerful eye-catcher. All things being equal, these channels of information will usually work in tandem with composition and the human signal patterns at work in a scene. Most films can be thought of as massively redundant systems for drawing our visual attention to certain items in the frame, second by second.

Story as task

One more point. Most of the factors I’ve mentioned involve bottom-up cueing. If in ordinary life our saccadic probes are governed by top-down task assignment, what about still images or moving pictures? Are there no task dictates at work? I think there are.

Recall most of the questions that Yarbus asked his viewers: the figures’ ages and clothing, their activities before the man entered, the family’s material circumstances. These are relevant to the tale the painting tells. It’s what we call a narrative painting, and most of Yarbus’ pointers are addressed to filling out the story.

The story may not be obvious to us today, but most commentators seem to agree that image represents a political exile returning from a labor camp to his family. The woman rising in the foreground is his mother, while his wife can be seen stirring from her place at the piano. His children are on the right, and many commentators interpret the somewhat fearful or puzzled expression on the little girl to indicate that she is too young to remember him. The image developed out of Repin’s sympathy for Russian radical movements of the time, and it was widely circulated by the later Bolshevik regime. Very likely Yarbus’s subjects would have seen the picture before and known the story behind it.

The point I want to make is that we do take on tasks when we watch a film image. Perhaps the most basic one is maintaining our interest, seeking out something that will keep our attention engaged at a basic level. But one major way to achieve interest is to make an effort to grasp how what’s happening onscreen develops the story.

Once the movie has started, we know who the main characters are and thus whom to watch most closely in ensuing scenes. We know something of their minds and motives, and we are sensitive to anything that impinges on those matters. So our top-down hypotheses about what’s going on and what will happen next shape what we look at and when we look at it.

Since story comprehension is one of our primary tasks in watching a mainstream movie, we will tend to ignore other things. We will miss changes in objects’ position across cuts (“cheats”) and disparities of lighting from shot to shot (e.g., the opening office scenes of The Godfather). These would seem to provide equivalents for the invisible-gorilla effect, although bottom-up factors are at play in such cases as well. Alternatively, when we don’t have any narrative expectations, as when we’re confronted with a lyrical avant-garde film by Stan Brakhage or Nathaniel Dorsky, perhaps we will let our eyes roam around the images more freely. Confronted by a film that denies us a narrative, we attend to composition, color, and other qualities that we may not notice in most storytelling cinema.

I’m convinced that research into vision is important to understanding film, but I’m a duffer at this. Next time, we hear from Tim Smith, a sort of modern-day Yarbus who monitors how we watch movies. An early example of his work is here, but next time we’ll catch up with his recent efforts.

Yarbus’s book is Eye Movements and Vision (New York: Plenum, 1967). It is rare and expensive, but a pdf is available online here. Google “Yarbus” and “Repin” together and you will find a great many research articles on eye movements and imagery. I’m grateful to amonseuldesir’s sitefor providing sharper diagrams of Yarbus’ result than I could squeeze out of my copy of his book.

Sasha Archibald has made a valiant effort to map Yarbus’ reported results onto the painting, as indicated in the image at the top of this entry. I thank Cabinet magazine for permission to reprint her schema. Thanks as well to Maria Belodubrovskaya for confirming the correct translation of the painting’s title. She recalls that in school she and other children were asked to discuss the reactions of the family portrayed in the painting.

For more on Dan Simons and Chris Chabris’ work, see The Invisible Gorilla and Other Ways Our Intuitions Deceive Us. Daniel Memmert has performed eye-tracking experiments with children watching the gorilla video. (See “The Effects of Eye Movements, Age, and Expertise on Inattentional Blindness,” Consciousness and Cognition 15 [2006], pp. 620-627.) Surprisingly, Memmert found that many subjects who fixated on the gorilla during the video still didn’t claim to notice it! Simons and Chabris use this finding to suggest that even fixations don’t guarantee awareness. It seems that fixation is a necessary but not sufficient condition for noticing something; once more, the task at hand can block out even things that we can see clearly.

Related to inattentional blindness is “change blindness.” As I mentioned in an earlier blog, Dan Levin, who worked with Simons, has explored how our inability to detect changes in images or in the real world can affect our understanding of edited scenes in films. Tim Smith has further studied “edit-blindness” as a cinematic parallel to change blindness.

Robert Zemeckis’ remark about guiding the viewer’s eye is quoted in Jay Holben, “Sole Survivor,” American Cinematographer 82, 1 (January 2001), p. 40. For more on that idea, see the opening chapter of my Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. More broadly, I discuss cinematic experience, and especially story comprehension, as an interaction of top-down and bottom-up factors in Narration in the Fiction Film and the first chapter of Poetics of Cinema.