Archive for the 'Film theory: Cognitivism' Category

THE SOCIAL NETWORK: Faces behind Facebook

DB here:

What do John Ford, Andy Warhol, and David Fincher have in common? Eyeball these remarks.

Ford, asked what the audience should watch for in a movie: “Look at the eyes.”

Warhol: “The great stars are the ones who are doing something you can watch every second, even if it’s just a movement inside their eye.”

Fincher, on the big club scene in The Social Network: “What’s cinematic are the performances . . . . What their eyes are doing as they’re trying to grasp what the other person is telling them.”

It isn’t just cinema that makes eyes important. Eyes are felt to be significant in literature, from the highest to the lowest. In just a couple of pages of a pulp adventure story you can read these sentences:

“Then it certainly does look very mysterious,” he said, but his blue eyes were quiet and searching.

Chief Inspector Teal suddenly opened his baby-blue eyes and they were not bored or comatose or stupid, but unexpectedly clear and penetrating.

What do quiet eyes look like, actually? Or searching ones: perhaps they’re moving a bit? Bored or comatose eyes might be droopy, so let’s count the eyelids as part of the eye. But what could make eyes, by themselves, penetrating? Nonetheless, we think we understand what such sentences mean.

Watching eyes is tremendously important in our social lives. We need to monitor other people’s glances to see if they are looking at us. We need to track what else they might be looking at. We need to watch for signals sent by the eyes, particularly attitudes toward the situation we’re in. For example, we seldom look directly into each others’ eyes, as characters in movies do constantly; in real life, “mutual gaze” is intermittent and brief. But if two people stare intently at each other, we’re likely to assume keen attraction or rising aggression.

In an essay from Poetics of Cinema available on this site, I talk about mutual gaze in cinema and how it can be exploited for dramatic purposes. The same essay takes up the issue of blinking; we blink frequently, but film characters seldom do, and the actors usually make the blinks emotionally expressive (of fear, uncertainty, weakness, etc.).

The problem is that eyes, by themselves, tell us very little about what the person behind them is thinking or feeling. We can show this with a little experiment.

Do the eyes have it?

What do these eyes tell us?

Certainly they give us information–about the direction the person is looking, about a certain state of alertness. The lids aren’t lifted to suggest surprise or fear, but I think you’d agree that no specific emotion seems to emerge from the eyes alone.

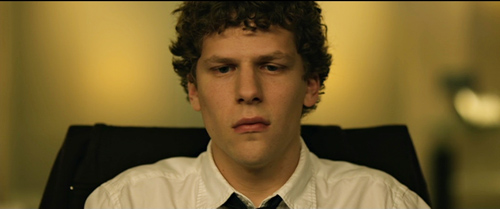

So what happens if we add eyebrows? (I’ve tipped the one above to conceal the brows; now you get to see the face’s proper angle.)

Now there’s a degree of surprise. The brows are lifted somewhat. But still the emotion seems fairly unspecific: not particularly sad or angry or distressed; probably not joyous either. Then what?

I’d call this dazed, slightly perplexed surprise. The sloping brows suggest the man is trying to figure out what’s happened; but the mouth is a slight gape. You can almost imagine the lips murmuring: “Ohhh,” or “Wow,” and not in appreciation or pleasure. If you wanted to show someone being blindsided, this is a pretty precise way to do it.

Of course context helps us a lot. Eduardo Savarin has just been gulled by his partner Mark Zuckerberg and by the interloper Sean Parker. His stock in the company that he co-founded is now worthless. So the situation informs our reading of Eduardo’s expression, and this permits the actor to underplay. Actor Andrew Garfield doesn’t give us bug-eyed surprise or frowning bafflement; he relies on our understanding of what he must be feeling (what we would feel) in order to refine and nuance his expression. When an actor underacts, we’re often expected to fill in the emotions we could plausibly imagine him to be feeling, on the basis of the story at this point. In isolation, the expression might be vague or ambiguous; the narrative situation helps sharpen it.

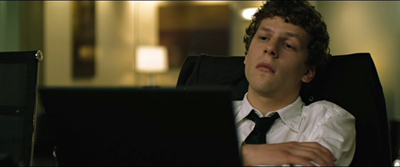

Back to the main question: How informative are the eyes alone? Try this one.

Again, I’ve tipped the shot a little to conceal the brows. Not much evident from the bare eyes, is there? Again, a certain focus and interest, but that’s about it. No marked surprise or fear or sadness.

Something has been added. The brows aren’t lifted in surprise or fear or sadness or distress; they seem to be relaxed. The angle of the look suggests concentration, but we’re not getting as much information as we got from Eduardo’s brows. We need a mouth.

The impression of concentration is greater, and I think we’d agree that this small smile of satisfaction gives us some insight into what the character is feeling. Again, the eyes tell only part of the story.

And again context matters. Mark Zuckerberg has just figured out that he can enhance The Facebook by adding users’ information about their romantic relationships. The tight, sidelong smile confirms not only his genius but also his view that college is partly about getting laid.

Less with the eyebrows

At this point you might be getting impatient with me. Isn’t this all obvious? Of course the actors use their faces–they’re paid to do that. But sometimes going obvious can get us to notice things.

For one thing, the eyes in themselves aren’t that emotionally informative. Pupil dilation can convey physical arousal, but that’s another story for another time. More commonly, the eyes give us the all-important information about what the person is looking at. The lids convey alertness, or drowsiness, or if they’re pinched a bit, concentration or anger.

Sometimes the eyes give us all the information we get. Here is Mark just before he agrees to take the job coding for the Winklevoss brothers’ project, The Harvard Connection. He moves from alertness to calculation by narrowing his eyes. As the phrase goes, you can hear the wheels turning.

Crucial to this moment is that nothing but Mark’s eyes and lids move; he doesn’t even turn his head. At the film’s climax, he will open up a little bit, and the eyelids play a central part. Getting the news that the Facebook party has been busted, Mark starts to breathe more laboriously, then wobbles his head slightly and closes his eyes. For once his concentration is broken.

It’s about as close as Mark comes to a canonical expression of sadness.

Obvious as it seems, by isolating the eyes we can notice the division of labor among eyes, eyelids, brows, and mouth: Each component supplies a bit of information. We’re remarkably skillful in integrating all these cues. What researchers into face perception call the informational triangle–the two eye regions tapering down to the mouth–creates a package of social and psychological signals. It’s this whole ensemble, the most informative parts of the face working together, that guides us in making sense of other people, or of film acting.

I’ve come to especially appreciate eyebrows. Daniel McNeill, in The Face: A Natural History, writes:

The eyebrow is the great supporting player of the face, and its work generally escapes notice. It helps signal anger, surprise, amusement, fear, helplessness, attention, and many other messages we grasp almost at once. Indeed, without eyebrows the surprise expression almost disappears. The eyebrows are such active little flagmen of mind-state it’s amazing anyone can wonder about their purpose. We use them incessantly (p. 199).

Since eyebrows are so important, actors must control them carefully. In the film’s first scene, Erica Albright moves her eyebrows vivaciously (and widens her eyelids too), but Mark’s brows are rigid and knit together.

This scene introduces us to Mark’s facial behavior. He will glance to the side when he’s pressed, but he’ll focus sharply on the other person when he’s trying to dominate the conversation. His mouth seems to be ruled by the triangularis and mentalis muscles, creating the inverted smile sometimes called the “facial shrug,” even when the lips are relaxed. Erica smiles a lot, something that usually triggers a responding smile. But not from this guy, though a smirk will occasionally flit over his mouth when he says something insulting. The closest we get to a true smile, I think, is at the blowout conclusion of the contest for internships, and that’s seen in the fairly distant long shot at the top of this section.

Above those eyes and that mouth sit those hooded brows, almost never lifting or lowering. Which is to say that Mark seldom shows surprise, and his anger will usually be visible in the set of his mouth (and in his words.) His flatlined brows sometimes suggest keen concentration, sometimes aloofness when he tilts his head back, or more pervasively the sense that everything in the vicinity is irritating. He seems to be permanently scowling, an effect that Fincher and DP Jeff Cronenweth accentuate by lighting that draws his brows closer together and hollows out the eye sockets.

How different this performance is from the actor Jesse Eisenberg’s everyday facial configuration (or at least the one he employs to send us other signals) can be seen in the making-of documentary accompanying The Social Network on DVD. One example surmounts this entry and shows a much different set of expressive cues–raised eyebrows, wider eyes, more cheerful mouth. The actor’s face is very mobile; he can even turn in the inner corners of his brows, which is hard to do voluntarily.

In one section of the making-of, Jesse reports that Fincher was often telling him, “Less with the eyebrows,” and onscreen Eisenberg delivered. By the end, for the last shots of Mark alone, Fincher asked for what’s become famous as the Queen Christina effect–an expression that could be read in many ways. “I want everybody to put anything on it.”

The result is a portrait of Generation Whatever, or an image of stoic loneliness, or of bemused curiosity about an old girlfriend, or. . . .

One more consequence of my noting the obvious: The centrality of faces to modern movies. Today’s films use close-ups very heavily, probably more than at any other point in film history. (The Way Hollywood Tells It explores some reasons why.) What I’ve called the “intensified continuity” style of modern cinema relies on tight single shots of individual players.

So modern players must be maestros of their facial muscles and eye movements. In other styles of filmmaking, currently and historically, the actor’s performance is projected onto more body parts through gestures, stance, gait, and the like. Recall Cary Grant, who performed with his whole body. Of course he wasn’t bad in close-ups either.

Faces aren’t everything in movies like The Social Network. Most characters use their arms and hands freely–probably the Winklevi the most. Mark is straightjacketed, but even he will gesture sometimes, as when a drooping Twizzler becomes his hand prop. He usually prefers a shrug, though it’s executed without the eyebrow lift most people add. Postures and personal walking styles play key roles in the film as well.

Still, as in most movies today, here eyes and brows and mouths are the main channels of emotional information. Fincher again: “It was really a movie about kids’ faces.” And even films from the 1910s, made before directors used a lot of cutting, often used long-shot staging to direct attention to the body’s most informative zones. A 1913 book on film acting noted, “Facial expression is perhaps the most important part of photoplaying. . . . After all is said and done the eyes are really the focus of one’s personality in photoplaying.”

Facebook facework

I can’t offer a complete account of nonverbal behavior in The Social Network here, but I want to end with a hypothesis that would be worth more detailed inquiry. The film’s central relationship is that between über-nerd Mark and Econ-major Eduardo, the coder and the aspiring tycoon (although he also supplies Mark with a crucial algorithm). Through facework, Fincher and his actors delineate the contrasting personalities and trace their shifting dynamic.

From the start, we get Mark’s stare of frowning concentration, drawing on the muscle called the corrugator, Darwin’s “muscle of difficulty.” By contrast, Andrew Garfield’s performance is marked by a look of worry and abashment. He’s often kinking his eyebrows, furrowing his brow, and ducking his head. Fincher motivates this behavior by having him often stoop over Mark’s workstation, tilt his head downward, and lift his eyes from underneath his brow.

In this shot/ reverse-shot passage, Mark’s mask never slips but Eduardo, wrinkling his brow and tipping his chin down a bit, looks apologetic.

Even when Eduardo has every right to berate Mark, he looks like he’s the one in the wrong. Instead of displaying the jammed-down, pinched-together brows of an angry man, he won’t lose his patient, slightly anxious look.

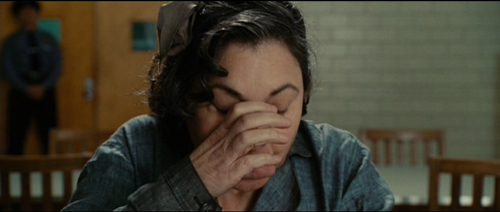

See the last image on this entry for a moment when Eduardo seems on the verge of tears–and this is after he’s gotten an invitation to join two alluring women.

You can argue that the blindsided expression we dissected earlier is one culmination of the facial cues that Andrew Garfield has been blending in the course of the film. But things are more complicated. The plot gives us two forward-moving timelines, one in the past tracing the rise of Facebook, the other in the present, during which Mark is deposed in two lawsuits. At an early deposition, Mark’s implacable stare works to make Eduardo revert to his old obeisance.

But in a climactic face-off, we come to see a different Eduardo.

Eduardo’s quiet testimony about whether anyone’s share but his was diluted (“It wasn’t”) affects Mark more deeply than the bluster of the Winklevoss brothers. The words are delivered without the usual sidelong glance, kinked eyebrows, or head ducking that has defined Eduardo earlier. His brow is smooth, his brows level. This is man to man, and it’s Mark who breaks off eye contact.

You could nuance this transformation by tracing it scene by scene, and contrasting it with the body language displayed by other characters. For today I simply wanted to sketch the broad development that I think is at work in this core relationship. The drama of domination and betrayal is played out in eyes, eyebrows, mouths, mutual gazes, and the like as much as it is in the dialogue and incidents.

There is no art, Shakespeare’s Duncan says, to read the mind’s construction in the face. He’s right about the reading part; we grasp expressions fast, intuitively, and often reliably. But there is art in the performer’s construction of the face, and of the director’s cinematic shaping of it.

John Ford’s remark about looking at the eyes is quoted in Joseph McBride’s Searching for John Ford (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010), p.2; the Warhol quotation comes from Andy Warhol and Pat Hackett, POPism: The Warhol ’60s (New York: Harper and Row, 1980), p. 109; quotations from David Fincher come from the bonus features on the collector’s edition DVD of The Social Network. My quotations about eyes in fiction are drawn from Leslie Charteris, Prelude for War (New York: Doubleday, Doran, 1938), pp. 171, 173. The 1913 quotation about eyes comes from Francis Agnew’s Motion Picture Acting (Syracuse: Reliance Newspaper Syndicate), p. 40; I learned of it from Janet Staiger’s article, “‘The Eyes Are Really the Focus’: Photoplay Acting and Film Form and Style,” Wide Angle 6, 4 (1985), pp. 14-23.

Ed Tan offers a very good analysis of the issues I mention here in his article “Three Views of Facial Expression and Its Understanding in the Cinema,” in Moving Image Theory: Ecological Considerations, ed. Joseph D. Anderson and Barbara Fisher Anderson (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005), pp. 107-127. I find Vicki Bruce and Andy Young’s In the Eye of the Beholder: The Science of Face Perception (Oxford University Press, 1998) a very helpful guide to ideas in this research area. The “facial shrug” is described in Gary Faigin’s excellent The Artist’s Complete Guide to Facial Expression (New York: Watson-Guptill, 1990), pp. 104-105.

There’s a fascinating debate in the human sciences about whether particular aspects of nonverbal communication are constant across cultures. Gestures vary considerably, but are facial expressions universal to some degree? Or do they differ from culture to culture? Are they primarily expressions of the person’s emotion, or are they signals which have developed, through evolution or cultural convention, to influence others? You can read more about these and other issues in Paul Ekman and Wallace V. Friesen, Unmasking the Face (Cambridge, MA: Maor Books, 2003) and Alan J. Fridlund, Human Facial Expression: An Evolutionary View (San Diego: Academic Press, 1994). The classic account is by Darwin, whose 1872 book Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals is available in an edition in which Ekman includes an afterword explaining the development of this research tradition.

Up to the minute, more or less: Contemporary research on smiling and eye contact.

PS 2 February: Thanks to William Flesch for correcting my Shakespeare citation: I originally attributed it to Hamlet.

Now you see it, now you can’t

DB here:

We usually respond to films spontaneously, but afterward we can think about our responses and figure out why we reacted as we did. When we’re fooled by a mystery, for instance, we can re-watch the film and trace exactly how we were misled. Now that Shutter Island is out on DVD, fans will be dissecting its visual gimmicks. Even when a film isn’t a mystery, a lot of critical analysis involves what we might call a rational reconstruction of how the whole shebang works. Novice screenwriters crack open a movie like The Apartment or The Godfather to peer into the fine mesh of plot construction, to tease out all the setups and plants and twists that seem inevitable only after the fact.

This is film research, we might say, at the personal level. Not in the sense of your or my unique identity, but rather at the scale we see the world. We don’t see atoms or gravity. We evolved to sense and think about middle-sized social and physical phenomena, like places and objects and, especially, other humans. We’re aware of the world because we sense ourselves as individual agents, guided by intentions and desires and beliefs. We’re used to talking about films at this level. When we track action and character, note surroundings and time passing, or ask about the purposes of a plot device or theme, we are working at the level of personhood.

But life assigns us to other levels too. There is the subpersonal level. All kinds of things are happening to you now that you can’t be aware of. You can’t watch the cells in your retina detect this sentence, or the neurons in your brain firing to make sense of it, or the flow of signals to your hand urging the mouse to scroll onward. A huge amount of our mental activity takes place behind the scenes that flit through our consciousness. We can’t pay attention to the man behind the curtain—partly because there is nobody there.

There’s also the suprapersonal level, the level of collective behavior patterns. Now we’re talking about people as parts of large-scale forces, like groups and cultures and societies. Historians have traditionally worked at this level. For example, some researchers have traced how film audiences, en masse, have responded to movies.

More strikingly, many scientists now study “self-organization”—the emergence of patterns of order that don’t seem to be willed or intended by individuals or groups. We find impressive instances in nature: fish swim and birds flock in intricate patterns that no one fish or bird could imagine or dictate. Such self-organization is even more striking in human activities like traffic flow or online networks. Is there a sort of “physics of society”? No doubt people have intentions and quirks, but often we can bracket those out and see shapes in the data that no one could have designed. The classic instance is a power law. A remarkable example is Vilfredo Pareto’s discovery that income distribution in any society tends to settle out as 20 percent of the people controlling 80 percent of the wealth. Mark Buchanan sums up the suprapersonal viewpoint this way: “Think patterns, not people.”

We know we can study films at the personal level. How can we study films subpersonally and suprapersonally too?

Reverse-engineering a movie

Mon Oncle.

My answer comes after four days earlier this month at the annual convention of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. We met in Roanoke, Virigina, in a massive nineteenth-century hotel made over into a convention center. You know the place has things under control when every PowerPoint presentation works flawlessly.

What ideas unite the film scholars, psychologists, and philosophers who gathered here? Roughly, the members explore moving-image media through empirical methods. Empirical inquiry can include classic scientific method (hypothesis/ experiment) or methods of aesthetic, historical or quantitative analysis. Typically the goal is not interpretation of a particular film or TV show or videogame but rather understanding of some general aspects of these media. Not explication, we might say, but rather explanation. Further, most members of the Society are interested in ways that film can be illuminated by areas of modern psychological research, such as neuroscience, cognitive science, and evolutionary psychology.

Some of our philosophers would say that they pursue conceptual analysis rather than empirical inquiry. Still, they join our meetings because the sorts of concepts they want to analyze are the ones that the film folk and the psychologists deploy—concepts like artistic intention or the nature of genre. Many of our liveliest sessions have come from disputes between Filmies, Psychos, and Philosophes.

For more on what we do, I’ve offered some background in earlier entries on this site. I previewed the 2008 convention here and here. I previewed the 2009 convention here and here.

Previews, but not followups. The big problem covering these events is that they’re so busy I have no time to blog during them, and by the time they’re over I’m usually en route to Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna. So I tended to make those entries introductions to the cognitive perspective, rather than surveys of who said what. This year, because our gathering was earlier than usual, I’m trying to sum up the event reasonably soon after it ended. We had simultaneous sessions, sometimes three at once, so I attended fewer than half of the talks. I’ll try to mention presentations that seem relevant, even if I didn’t hear them. Similarly, I heard some presentations (e.g., Lisa Broad on possible worlds) that were stimulating but don’t quite fit into my thesis here.

There were plenty of talks that developed arguments at the level I called personal. That is, they analyzed how films were designed to achieve certain effects. This calls for “reverse engineering”: starting from plausible viewer responses and then looking for creative choices made by the filmmakers that seemed to fulfill particular functions.

Take as an example Carl Plantinga’s paper on how we strike up moral attitudes toward characters. He was interested in how we achieve what Murray Smith calls “allegiance”—a “pro-attitude” toward certain characters. Is it just a matter of wishing good things for them, or admiring their positive traits? Is it a matter of sympathy for their situation?

Take as an example Carl Plantinga’s paper on how we strike up moral attitudes toward characters. He was interested in how we achieve what Murray Smith calls “allegiance”—a “pro-attitude” toward certain characters. Is it just a matter of wishing good things for them, or admiring their positive traits? Is it a matter of sympathy for their situation?

Carl argued that all these factors play a role, but they aren’t enough to assure our siding with a character. He argues that allegiance also involves moral judgments, or rather moral intuitions. Films exploit two facts about these moral intuitions: they must be summoned up quickly, without much thought, and they are often driven by emotion rather than ideas.

Oddly enough, our moral intuitions are not necessarily driven by moral standards! Carl drew on Anthony Appiah’s analysis of moral judgments as influenced by how a situation is framed, ordered, and primed—basic cognitive cues that influence responses. For example, Legends of the Fall sets up two brothers, one conventionally moral and the other not. Yet it’s the wild, violent Tristan who earns our sympathies, because he displays vitality, youth, beauty, sensitivity, and closeness to nature. The upshot is that we rationalize a moral judgment on non-moral grounds. Carl got several questions about his conception of morality and the possibility that our moral intuitions are tied to things we value, like beauty.

Malcolm Turvey offered a paper on gags in Jacques Tati. Pointing to prior work on how Tati’s gags are integrated into a shot’s composition (scattered so that we may miss them) and linked to one another (through overlap, Kristin has suggested), Malcolm went on to argue that the gags themselves don’t obey the conventions of classic comedy. They exhibit strategies of misinterpretation, blockage, ellipsis, fragmentation, and concealment that are highly original and unusually challenging. Malcolm is working on a book on “ludic modernism,” and he sees Tati as fitting into this tradition.

Malcolm’s precise and persuasive account was framed by a strong attack on the tendency of cognitive film theory to concentrate on ordinary, even undistinguished films and ignore problematic and avant-garde instances. He pointed to passages in Stephen Pinker’s writings that mock experimental art, and he urged cognitive film researchers to “call Pinker out” for his borderline Philistinism. He remarked that psychological researchers could learn as much from Tati’s work as from ordinary films…and maybe discover new things.

A similar sort of rational reconstruction at the level of personal response was found in many other papers I heard. Jason Gendler dissected the misleading narration in The Blue Gardenia. Rory Kelly wondered why viewers tend to forget the water-utility plotline at the start of Chinatown. James Fiumara considered why modern startle effects are comparatively rare in classic horror films. Torben Grodal isolated a group of “disgust-driven phobic films” (Taxi Driver, Blade Runner, Se7en) that sink so deeply into disgust that melancholy drives out empathy. Lennard Hojberg studied circular camera movements that express the dizziness of love as based on embodied vision.

A similar sort of rational reconstruction at the level of personal response was found in many other papers I heard. Jason Gendler dissected the misleading narration in The Blue Gardenia. Rory Kelly wondered why viewers tend to forget the water-utility plotline at the start of Chinatown. James Fiumara considered why modern startle effects are comparatively rare in classic horror films. Torben Grodal isolated a group of “disgust-driven phobic films” (Taxi Driver, Blade Runner, Se7en) that sink so deeply into disgust that melancholy drives out empathy. Lennard Hojberg studied circular camera movements that express the dizziness of love as based on embodied vision.

Some researchers used quantitative procedures to capture a film’s regularities. Monika Suckfuell (right) exposed some very complex patterns in a short film, Father and Daughter. These create a distinct emotional tone through what she calls “distance editing.” The patterns are combinations of thematic units like problem-solving or humor, and the recurring combinations arouse both comprehension and pleasure. In another quantitative study, Tseng Chiaoi and John Bateman sought to tie concrete uses of filmic elements with more abstract aspects of meaning. (Chiaoi and John had done a presentation on film-based discourse semantics at last year’s event.) Concentrating on characters’ action patterns, Chiaoi used computer software to trace their structures in television commercials and the war genre.

Squeezing the stimulus

Bopping after a session: Tseng Chiaoi and Paul Taberham.

The talks I’ve mentioned, along with several others, analyze processes that we can access by re-viewing films, studying their form and materials, and examining the genres and stylistic traditions to which they belong. But other talks concentrated on the subpersonal areas, the parts of our responses that we can’t access so easily.

For instance, how do we mentally stitch together various shots to create a unified space for a scene’s action? Film scholar Todd Berliner and psychologist Dale Cohen presented an account of how we achieve an illusion of spatial continuity. Initially the brain grasps shots as if they were pieces of space selected by the viewer, and then it builds up a model of the whole space—say a porch in front of a house’s front door. When a character moves his arm a certain way toward an offscreen area, our model of porches and doors makes it most probable that he is pressing the doorbell.

For instance, how do we mentally stitch together various shots to create a unified space for a scene’s action? Film scholar Todd Berliner and psychologist Dale Cohen presented an account of how we achieve an illusion of spatial continuity. Initially the brain grasps shots as if they were pieces of space selected by the viewer, and then it builds up a model of the whole space—say a porch in front of a house’s front door. When a character moves his arm a certain way toward an offscreen area, our model of porches and doors makes it most probable that he is pressing the doorbell.

In such ways we run “beyond the information given.” Filmmakers count on our doing that, so they give us feedback (say, the sound of a doorbell, or a shot of a door opening) that confirms our model of the space. Most mainstream films build in such redundancy. But the unity of these spaces is undermined by some contemporary exhibition technology. Todd and Dale suggested that the mental models we build of space exclude the movie theatre, so that surround sound and 3D become problematic.

They also got several good questions. How concretely specified are these model spaces? How do they develop in the course of a scene? Might our perception of continuity come down to a lack of perception of discontinuity—that is, maybe we operate on very simple default assumptions and don’t build up many models of the space.

Todd and Dale’s presentation was in the Helmholtz tradition; they even invoked “unconscious inference” as part of the story. Another tradition, represented by SCSMI founders Joseph and Barbara Anderson, invokes James J. Gibson’s ecological approach to perception, which argues that such modeling and inference-making isn’t really happening. Things are much more direct: Perception is data-driven, and needs top-down correction only in rare cases (like nighttime or fog).

Other perceptual researchers try for a more parsimonious research strategy: How much information about the visual world can we squeeze out of the stimulus? This question was raised by Jordan DeLong, who has been exploring how we can identify emotional arousal through very “low-level” information. Using a corpus of 150 films (more on this later), he looked at shot lengths, the distribution of shot-lengths across a film, and a purely physical measure of visual activity (essentially the change from frame to frame) to see if they correlate with genres we associate with high levels of arousal, like action and adventure films. Jordan’s study is preliminary, but there is the possibility that certain purely physical features are reliable indices to levels of arousal—even if people don’t notice those features and are much more fastened on characters and their actions.

The current projects of Tim Smith’s research team exemplify the parsimonious strategy. Tim is a long-time participant in SCSMI, and his talks show how a research program can expand and enrich itself.

We know people look at certain areas of a shot. We also know that our attention is directed, driven by features of the stimulus. What features? We filmies would pick out shot composition, color, movement, lighting, shot scale, etc. We can access those middle-level variables through expert introspection and analysis. But can those features be further decomposed?

Tim thinks so. We can consider any of these technical qualities as made up of luminance, color channels, and other low-level physical aspects of vision. Through signal-detection methods, Tim seeks to pinpoint what the crucial variables are. The results of his work are soon to be published, and I don’t want to give the game away. I’ll just say that he has shown through eye-tracking that certain low-level features are more important than others in engaging viewers’ attention.

One implication of Tim’s findings is that what I’ve called “intensified continuity” seems to have an optimal grip on spectators. This technique, he remarked, “almost paralyzes the eyes,” yielding “an illusion of active vision with passive eyes.” More generally, his work seems to back up James Cutting’s remark that “There is no such thing as voluntary attention sustained for more than a few seconds at a time.” Most of our attention is at the mercy of the outside world, which means that filmmakers need to engage us at every moment—either with narrative, or with something else we’ll find arresting.

Dan Levin, Pia Tikka; in the background William Brown, Carl Plantinga, and Dirk Eitzen.

Dan Levin gave the keynote address at SCSMI two years ago, and he showed how we vastly overrate our ability to spot outrageous changes in the world or on the movie screen. (He’ll have a field day with the tricks in Shutter Island, such as the one surmounting this blog.) This time around Dan talked about Theory of Mind in the movies, the ways that films exploit our (species-specific?) inclination to attribute beliefs, desires, and goals to the creatures we see in the world, and in films. His paper scanned mandatory, bottom-up cues, middle-level activity (the sort of organization of visual space Todd and Dale discussed), and then “controlled cognition,” such as our narrative expectations. So for Dan it’s not all in the stimulus. Once we’ve picked out certain aspects of it, our Theory of Mind system locks on them.

What aspects? Chiefly, signals of intention and marked eye direction. When we think we’re watching an intentional agent, like a movie character, we tend to see the agent’s eye direction as giving us a clue to his or her aims. Using films he has made, Dan tests people for how eyeline-matched cuts are read, and he varies the cues to see how people construe them differently.

Interestingly, when he showed the same shots in a different order, about two-thirds of the subjects didn’t notice that the order was different. That is, whether the object of the glance or the person glancing came first, gaze deflection remained the primary cue to understanding the situation. This suggests to me that storytelling cinema doesn’t absolutely need the classic pattern of person looking/ person looked at/ person looking, but the extra shot makes sure we all understand (redundancy again).

A similar sort of top-down/ bottom-up theory was proposed by Dan Barratt, who gave it a more computational spin. Like Tim, he works on eye movements; like Todd and Dale he’s interested in how we construct space; like Dan, he seeks out intentional factors. It’s not all in the stimulus, but we won’t know how much until we keep squeezing.

Ripples in the flow of films

The Society broke new ground in what I called the “suprapersonal” realm, that of large-scale patterns of activity that aren’t explicitly coordinated by individuals or groups. Several researchers are probing this in relation to films. Films are, in effect, deposits of human behavior; they are artifacts resulting from choice. What if we find patterns of choice that we can’t plausibly trace to coordinated decision-making?

Chris Atherton raised the issue by considering how to study style statistically. Citing Barry Salt as a pioneer in the area, he focused on the work of the Cinemetrics group and offered suggestions on how to better collect data and track patterns at various levels of generality. More sharply, he posed the question of function. How can you measure that? One implication was that in a big body of films we can disclose order that can’t wholly be explained as the sum of individual choices. Those choices matter, but so do forces we have yet to determine, including historical processes. Chris’s reflections chimed nicely with those of our keynote speaker.

James E. Cutting is a distinguished perceptual psychologist at Cornell. He’s written a fine book on motion perception and has done a quantitative historical study of the creation of the canon of French Impressionist painting. He’s a former dancer and a sensitive appreciator of art and music (and film). He’s the ideal person to analyze ticklish aesthetic issues.

You may have run across him recently because his research on Hollywood films was picked up and trumpeted in the press. “Solved: The Mathematics of the Hollywood Blockbuster,” read one headline. Needless to say, James was doing something more subtle. You can read summaries here and here.

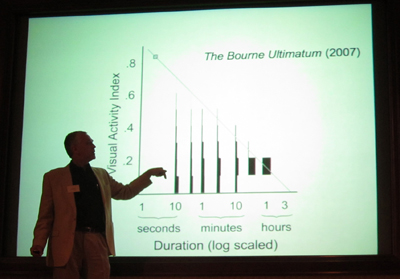

In his lively address, “Attention, Intensity, and the Evolution of Hollywood Film,” James explained two of his areas of interest: the ebb and flow of change across a film, and how that change is tied to human pickup. James studies these topics with a big database: 150 movies from 1935 to 2005. He emphasizes widely seen films belonging to five genres and chosen from the highest-rated titles on IMDB. But there’s a micro- side too. He and his research team went through every film frame by frame coding each one along many dimensions.

Naturally, he takes on the vexed issue of Average Shot Length. You can read the ongoing discussions of this concept on Yuri Tsivian’s Cinemetrics site. What interests James is less ASL in itself than the ways in which comparable patterns of shot lengths cluster in certain parts of the film. A film’s ASL may be 8 seconds, but in some passages several shots might have similar lengths, say 12 seconds each. Moreover, those patterns may “ripple through the film,” recurring at certain intervals and different scales (shot clusters, scenes, or other chunks).

Not every film shows such patterns; film noirs seem random in their patterns of shot lengths. But many movies, especially those of the last fifty years do display these patterns—typically clusters of short shots for physical action, clusters of longer ones for conversations. This clustering tendency is on the increase, even outside the action genre.

Not every film shows such patterns; film noirs seem random in their patterns of shot lengths. But many movies, especially those of the last fifty years do display these patterns—typically clusters of short shots for physical action, clusters of longer ones for conversations. This clustering tendency is on the increase, even outside the action genre.

The finding leads James to ask about the pacing of visual change, which raises the prospect of the sort of tension/ release dynamics we find in music. The patterns he finds don’t look arbitrary because they match the so-called 1/f or pink-noise pattern. This pattern has been detected in the natural world, in heartbeats, and in brain activity. It’s also been discovered in reaction times to tasks. In effect, the 1/f pattern captures not continual attentiveness but rather an alternation of intense concentration, moments of slower pickup, and moments of sheer mind-wandering. A nontechnical explanation of the 1/f pattern is here; a technical one is here.

As for intensity, James is seeking to measure visual activity in the shots. How much change, in effect, can there be from frame to frame? This can be captured by correlating each frame with its mates. James and his team find that from 1930 to 1950, there’s been a steady increase of frame-to-frame visual activity across all genres. The images became busier, with more movement. Today, he suggests, Hollywood is exploring ways to raise the frame-to-frame visual activity—not only through lots of movement of characters (the action film comes to mind) but also through “queasicam” handheld movements.

In combination with decreasing ASLs, Hollywood seems to be asking: How briefly can I show you this and still get the point across? So far, James suggests, films like Mission: Impossible III and The Bourne Ultimatum seem to be the busiest at the visual level. But animated films score about the same.

James has a caveat: The size of the screen matters. Even a big home-theatre screen doesn’t duplicate the breadth of a theatre screen, which activates not only our central vision but our peripheral vision too. That’s why bumpy shots that you can tolerate on a computer monitor may make you queasy at the multiplex. Interestingly, the Bourne films and Cloverfield, James suggests, were more popular on IMDB after the DVD versions came out. Perhaps people were better able to assimilate them on a smaller display.

At one level, James is interested in the subpersonal factors. He grants that you don’t notice cuts but can attend to them if you shift your focus from the story. But the widespread patterns he discloses aren’t easy to ascribe to deliberate planning. Nobody but an avant-gardist would decide to have shots of similar lengths at points 14 minutes or 25 minutes apart throughout the film. But James finds such correlations at levels beyond chance.

I can’t pretend to understand everything mathematical in James’ argument, but I think that his discoveries open up a new way to think about pacing in film. My first impulse is to think about historical causes, as Chris suggests: filmmakers learning from each other, converging on optimum choices. But I also like to entertain the possibility that this optimum carries a resonance even beyond the flux of history. Perhaps like fish and fowl, filmmakers are obeying and viewers are fulfilling, completely unawares, deep rhythms built into nature and numbers.

A tangled databank

Traditional humanists would decry a lot of what goes on at SCSMI meetings. The appeal to general explanations, the recourse to biology and evolution, the use of quantitative and experimental methods would all smack of “scientism.” But more and more, humanists are starting to turn away from the endless reinterpretation of canonical or non-canonical artworks. Many are also quietly defecting from the Big Theory that dominated the 80s and 90s. In film publishing, I’m told, editors have come to an informal moratorium on books on Deleuze. Possibly more people write them than read them.

Committed to a theory of permanent revolution in Theory, humanists are seeking new pastures. Some have discovered neuroscience, others evolutionary psychology. Franco Moretti has launched quantitative studies of the literary marketplace. For many converts, the reconciliation with science is just a bandwagon to hop onto, and they will jump off when a newer one trundles past. But other scholars have been committed from early on. The prospect of “consilience,” the compatibility between the sciences and the arts, is something the literary Darwinists like Brian Boyd, Jonathan Gottschall, Joseph Carroll, and like-minded souls were defending long before it became fashionable.

Film theory, as Joe Anderson is fond of pointing out, has a long and intense fascination with experimental psychology. Hugo Münsterberg, Rudolf Arnheim, and Sergei Eisenstein saw no conflict in studying film art with tools and findings derived from the sciences. That interest was lost in the 1960s, for a variety of reasons. But some of us have persisted. An explicitly “cognitive” perspective has been developing in film studies for the last twenty-five years, and SCSMI has nurtured this tradition since 1997. Our commitment is deep. We’re making headway. We’re not going to go away.

There is grandeur in this view of life, and cinema.

Our Society owes a great debt to Stephen Prince of the Virginia Tech School of Performing Arts and Cinema, who hosted this year’s convention. He also gave a splendid paper on the research traditions behind precinematic optical toys, as a way of thinking about modern CGI.

I found these books on suprapersonal patterns helpful: Mark Buchanan, The Social Atom: Why the Rich Get Richer, Cheats Get Caught and Your Neighbor Usually Looks Like You (London: Cyan, 2007); Steven Strogatz, Synch: The Emerging Science of Spontaneous Order (New York: Theia, 2003); Philip Ball, Critical Mass: How One Thing Leads to Another (New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 2004).

Todd Berliner and Dale Cohen’s paper, “The Illusion of Continuity: Active Perception and the Classical Editing System,” is scheduled for publication in the Journal of Film and Video in 2011. Tim Smith’s paper is in press at Cognitive Computation as P. J. Mital, T. J. Smith, R. Hill, and J. M. Henderson, “Clustering of gaze during dynamic scene viewing is predicted by motion.” You can check Tim’s DIEM project for video demonstrations, and his blog, Continuity Boy.

The original article by James Cutting, Jordan DeLong, and Christine Nothelfer, “Attention and the Evolution of Hollywood Film,” appeared in the March issue of Psychological Science. Access is through subscription.

As for Shutter Island, thanks to Justin Daering for pointing out the double sleight-of-hand. More thoughts on the film and Scorsese’s expressionist/ impressionist tendencies are in our backfile.

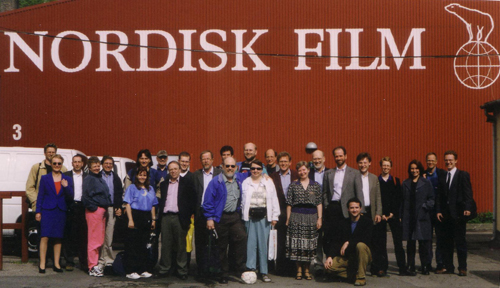

1999 Conference of the Center [later Society] for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image; Valby, Denmark. Photo by Johannes Riis.

Things we like of late

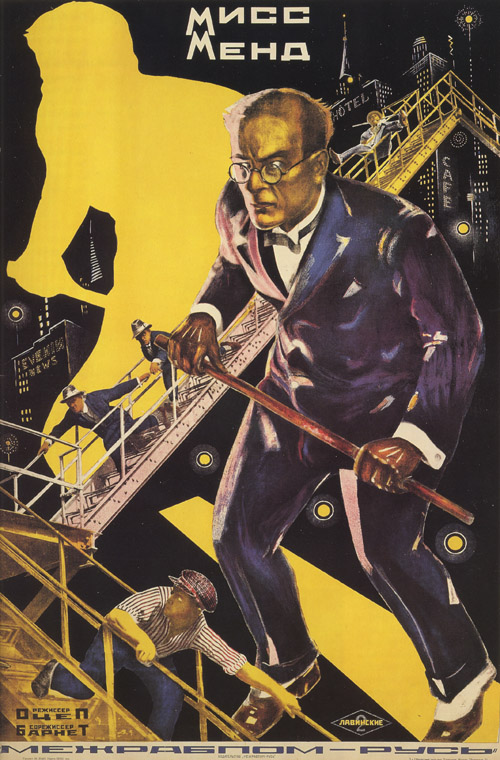

One of several posters the Stenberg brothers designed for Miss Mend.

We’ve been quite busy in the tail end of October. David sweated over a Bresson essay, started on his online version of Planet Hong Kong, and continued to help out in Lea Jacobs’ seminar on film stylistics. Kristin has started organizing a book about the statuary from the site in Egypt where she works for three weeks each year. And both of us have been steering the ninth edition of Film Art: An Introduction through the final phase of production. So instead of a blog essay this week, we offer some items from recent months that we think deserve wider notice and in some cases a pat on the back.

In our second report from the Vancouver film festival, Kristin wrote about a Chilean film, The Maid. She suggested that it was entertaining enough to be remade in English as a vehicle for an actress willing to play middle-aged and curmudgeonly. On October 16, the film was released theatrically. Starting in one theater, then going to six, and now 13 in its third week, it’s doing pretty well judging by per-theater averages. It’s not likely to get beyond big-city arthouses, but at least a release means that it should come out on DVD.

Speaking of DVDs, German silent cinema continues to be well-served with two new releases from British firm Eureka! F. W. Murnau’s 1922 film Phantom was already available in the US on the 2006 disc from Flicker Alley. The new Eureka! set includes both Phantom and Die Finanzen des Grossherzogs (1924). We saw the latter years ago at the National Film Theatre in London. It’s a comedy, and it struck us that Murnau was a bit ill at ease in that genre. Still, any Murnau film is worth a look. The set contains commentary on Die Finanzen by David Kalat, and there’s an essay on both films by Janet Bergstrom.

Speaking of DVDs, German silent cinema continues to be well-served with two new releases from British firm Eureka! F. W. Murnau’s 1922 film Phantom was already available in the US on the 2006 disc from Flicker Alley. The new Eureka! set includes both Phantom and Die Finanzen des Grossherzogs (1924). We saw the latter years ago at the National Film Theatre in London. It’s a comedy, and it struck us that Murnau was a bit ill at ease in that genre. Still, any Murnau film is worth a look. The set contains commentary on Die Finanzen by David Kalat, and there’s an essay on both films by Janet Bergstrom.

One of the best arguments that sequels and series, even those about super-villains out to rule the world, aren’t necessarily bad is Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse films. They span almost the length of his directorial career, from the two-part serial Dr. Mabuse der Spieler in 1922 through Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse in 1933, up to his last but definitely not least film, Die 1000 Augen des Dr. Mabuse (1960), which David included in his Belgian summer course. For those who can’t get enough of this arch-fiend and his followers, Eureka! has packaged all three in a new boxed set. There are numerous extras, which you can read about here. For those who have only seen The 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse dubbed in English, this set gives the option of German with subtitles or dubbed. (The films are not available from Eureka! separately.)

The films of Lev Kuleshov pupil Boris Barnet are only gradually being discovered outside Russia. One of the hits of this year’s “Il Giornate del Cinema Muto” was his 1928 comedy, The House on Trubnaya. Yes, there were Soviet Montage comedies, and this is one of the funniest. Let’s hope an enterprising company brings it out on DVD.* In the meantime, Flicker Alley is doing its bit to make Barnett known by releasing his 1926 three-part serial, Miss Mend. We saw it years ago without subtitles, so we look forward to finally finding out exactly what this fast-paced thriller is about. Something anti-capitalist involving the “Rocfeller and Co.” factory.

Soviet film was much on our minds this semester because our Cinematheque was running a series of films by Grigori Alexandrov. Probably best known for collaborating on Eisenstein’s silent films, Alexandrov came into his own in the 1930s with a series of lumpy but ingratiating musicals. They run the gamut from slapstick to mild satire (of familiar targets like bureaucrats). He likes silly gags, direct address to the audience, and a sort of relentless jollity that seems designed to prove Stalin’s claim in those years of privation that “Life has become gayer, comrades, life has become more joyous.”

Jolly Fellows (aka Jazz Comedy, 1934) is a somewhat labored effort in Marx Brothers absurdity, while Bright Path (1940) gives us a Stakhanovite Cinderella. It’s full of special-effects trickery used for comic effect, as when a poster coyly comes to life.

Although Alexandrov helped bring Hollywood production values to Soviet cinema, his 1936 Circus is a pointed critique of American racial bigotry.

Alexandrov’s best known film is Volga Volga (1938), reportedly Stalin’s favorite movie. It’s a meandering tale enacting the battle of highbrow music and popular tastes, including a clever scene (perhaps derived from the “Isn’t It Romantic?” number of Love Me Tonight) in which the movie’s principal tune jumps from boat to boat down the river, until it has become an unofficial national anthem. The films star Alexandrov’s wife, Lyubov Orlova, whose bullheaded energy swamps all resistance. The series is from a touring program, Red Hollywood, and you can read the background here.

Wisconsin Bioscope silent films went south in August–specifically, to São Paulo’s third Brazilian Days of the Silent Cinema. Here at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Dan Fuller, a photographer and historian of photography, teaches students to use classic cameras and devise their own 1910s movies. Of the two Bioscope films chosen for the São Paolo festival, A Expedição brasieira de 1916 (2006) depicts the first earthlings’ arrival on the moon. It features a stirring performance by a novice actor (above) whose film career was tragically cut short when he decided to become a professor.

Cinema in yet another land is the subject of Research Guide to Japanese Film Studies by Abé Mark Nornes and Aaron Gerow. At its center is a robust bibliography, including journals as well as books, but there’s much more: a survey of archival collections of films and documents, a list of film distributors, a gathering of online resources, and even a list of bookstores specializing in Japanese cinema. Donald Richie calls it “a reference work which both illuminates and defines this field, clearing a formerly obscured terrain for future scholarship.” Markus and Aaron are strong participants in a tide of younger scholars, both Asian and Western, who are rethinking this very important national cinema.

Images, not moving, come at you in another package. Remember Viewmasters? Vladimir, a projectionist at the Northwest Film Center in Portland, makes handsome viewmaster-style discs presenting strange tales culled from Kafka, Calvino, and less-known sources. The images are still-lifes incorporating toys and props, and it’s up to you to figure out the narrative. Concept sometimes outruns execution, but the shots suggest a childhood world turned sinister. You can even get your own viewer–called, naturally, a Vladmaster.

Images, not moving, come at you in another package. Remember Viewmasters? Vladimir, a projectionist at the Northwest Film Center in Portland, makes handsome viewmaster-style discs presenting strange tales culled from Kafka, Calvino, and less-known sources. The images are still-lifes incorporating toys and props, and it’s up to you to figure out the narrative. Concept sometimes outruns execution, but the shots suggest a childhood world turned sinister. You can even get your own viewer–called, naturally, a Vladmaster.

At Parallax View, Sean Axmaker is building an online archive of the complete run of the legendary magazine Movietone News. Richard T. Jameson and Kathleen Murphy are leading voices in American film criticism, but I suspect that the younger generation isn’t as aware of them as it should be. In Movietone News and elsewhere they provide a body of criticism that nicely balances judgment, information, and ideas. Hats off to Jim Emerson for using Halloween as an occasion to point up Richard’s astute observations on modern shot design.

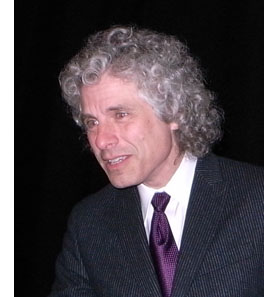

On Sunday night we went along with Jeff Smith to a campus lecture by Steven Pinker. The talk was a condensation of Pinker’s book The Stuff of Thought, a fascinating effort to show how various dimensions of language, chiefly semantics and pragmatics, reflect basic concepts of space, time, causality, and social relations. Language, Pinker says, furnishes a window into human nature. In a virtuoso turn, the book wraps up two trilogies at once: it caps a pair on cognitive and evolutionary theory (How the Mind Works and The Blank Slate) and a pair on grammar and semantics (The Language Instinct and Words and Rules).

On Sunday night we went along with Jeff Smith to a campus lecture by Steven Pinker. The talk was a condensation of Pinker’s book The Stuff of Thought, a fascinating effort to show how various dimensions of language, chiefly semantics and pragmatics, reflect basic concepts of space, time, causality, and social relations. Language, Pinker says, furnishes a window into human nature. In a virtuoso turn, the book wraps up two trilogies at once: it caps a pair on cognitive and evolutionary theory (How the Mind Works and The Blank Slate) and a pair on grammar and semantics (The Language Instinct and Words and Rules).

David first heard Pinker speak at an at extraordinary conference in Santa Barbara in August 1999. Coordinated by Leda Cosmides and John Tooby, “Imagination and the Adapted Mind” was an effort to explore how the arts could be illuminated by contemporary psychology, particularly one informed by an evolutionary perspective. This event–featuring not only Pinker but also Mark Turner, Eleanor Rosch, Ellen Dissayanake, Don Browne, and other luminaries–was a major moment in bringing “evolutionary aesthetics” to the table, although it’s taken about a decade for most humanists to catch up. (Several of the papers are available in a double issue of SubStance.) It was at that event that Pinker made his notorious suggestion that art was a byproduct of the brain’s evolution, a sort of “mental cheesecake” designed as a compact “superstimulus” appealing to our senses, mind, and emotions.

David had read The Stuff of Thought when it came out and had viewed the talk online. Sunday’s lecture remained a compelling performance, packing a remarkable number of ideas, data, and vivid examples into an entertaining seventy-five minutes. Pinker has been called the Dawkins of linguistics and cognitive psychology, but his sense of humor is rowdier. His straightfaced analysis of swearing is lively enough on the page, but it’s uproarious live.

Finally: Ever notice how many classic kung-fu movies are in widescreen? David has posted a new online essay tracing how Shaw Brothers popularized the anamorphic format in Hong Kong. The essay also considers how the widescreen format led Hong Kong filmmakers toward a distinctive approach to composition, cinematography, and dynamic movement. . . . of which the image below is a fair instance.

*[Nov 5: Thanks to James Steffen for alerting us to the fact that Edition Filmmuseum is bringing out The House on Trubnaya, along with Barnett’s other silent comedy of the same period, The Girl with the Hat Box, soon. There’s an impressive list of films in preparation, including the rare Expressionist classic Von morgens bis Mitternacht (1920), by Karl Heinz Martin. Comedy lovers should key an eye open for the release of a collection of Max Davidson’s hilarious silent comic shorts, including, we presume, the immortal Pass the Gravy.

Variety also has announced that Sundance is going national. On January 28, 2010, eight filmmakers will present their films and hold Q&As in eight theaters across the U.S.A. Madison, with one of only two Sundance multiplexes in the country, will be one of the host cities.]

Return to the 36th Chamber.

Who will watch the movie watchers?

DB here:

Today, I offer more on cognitive film studies, the activities of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image, and why both matter. For background, visit the previous post and here and here. Throughout, I’ll harken back to the issue of convergent audience responses: How can viewers from different cultures grasp certain appeals that films provide?

This research tradition seeks to answer questions about moving-image media, especially questions of an artistic nature. The researchers examine filmmaking with the assistance of findings and theoretical frameworks that have emerged in the cognitive sciences of psychology, anthropology, and other disciplines. Some specifics:

Cognitive film studies emphasizes explanations over interpretations. Explanations can be causal (what made this happen) or functional (pointing out the purposes that something fulfills). When human action is part of what we’re studying, the explanations tend to involve goals and motives, means and ends. By contrast, a lot of humanistic media study emphasizes interpreting films but leaves causal and functional processes unexamined.

This research tradition is mentalistic. In explaining viewers’ responses, it looks first to features of the human mind. This doesn’t mean that researchers study minds cut off from society; rather, the emphasis is on the mental activities tied to all sorts of experience, including social action and interaction.

This tradition is naturalistic. The explanations it mounts try to fit in with current understanding of human capacities as analyzed by the social sciences. That entails that psychoanalysis, another mentalistic theory of human action, has not on the whole proven a source of reliable explanations. Some cognitively inclined researchers would add that psychoanalytic inquiry has been fruitful for pointing to areas of behavior that answer to naturalistic investigation.

The line of argument, accordingly, is that of rational inquiry, induction and deduction. It stands in contrast to much current film theory, which consists of more or less free association and the rote citation of major thinkers. Cognitive film theory tries to formulate clear-cut questions and to seek answers that have empirical grounding and conceptual coherence.

The tradition has a strong tendency to look for cross-cultural regularities among artworks and viewer experiences. The sources of these regularities need not be innate in any strong sense. Critics sometimes claim that cognitivists believe that everything is “hard-wired,” but virtually no cognitivists say or believe that. For one thing, our “wiring” changes at certain critical periods, especially two months, nine months, and four years of age. Moreover, the regularities in behavior we notice occurring across cultures or social milieus may have come into existence for many contingent reasons. That doesn’t make them any less interesting as explanatory factors.

For example, no culture is without fibers to bind things, but we shouldn’t expect to find a “string” gene or neuron. In this case, and many others, humans equipped with some common faculties and faced with common demands have found common solutions. We can study shared strategic behaviors without committing ourselves to biological determinism.

People who believe in the cultural construction of nearly everything appeal to learning as the means by which cultural processes shape individual action. Yet cultural constructivists have on the whole been unable to specify how learning is possible. Since an utterly vacant mind could never actively pursue or acquire or organize knowledge, we’re obliged to consider that some innate propensities are in place before humans make contact with the manifold of experience. No one needs to teach a newborn to pick out moving objects or synchronize lip movements with sound patterns.

Moreover, if you rest your case on the metaphor of construction, you need to specify the materials out of which action is built. Up to a point you can say that there are cultural constructions out of other constructions and so on. But the system has to get started somewhere. You have to be able to see color before you can learn that stoplights and stop signs are red. Ingrained capacities and tendencies are the best candidates for being the stuff out of which various cultural conventions are constructed.

Most cognitivists hold to the post-Chomskyan view of learning as the unfolding and refinement of innate predispositions and mental structures. In order to learn something, you need to know something else. In fact, a lot else. It now seems overwhelmingly evident that humans come into the world with many predispositions, some broad and vague, some quite concrete. Some of these are primed in the womb, as with a newborn’s preference for mother’s smell. Other predispositions require only a few confirming encounters to be locked in. A baby is sensitive to a certain range of phonological and prosodic patterns, and so she is ready to fasten on those characteristic of a specific language. Babies seem as well to have an intuitive physics; they are surprised when objects disappear or turn into something else. Babies also are sensitive to eye contact and smiling, both crucial to social interaction and reading others’ intentions.

In sum, the most plausible learning model is that of predispositions, often sometimes quite narrowly constrained, that are confirmed and fine-tuned by the environment (often within a critical period of exposure). We need active engagement with the environment, both physical and social, to let our intrinsic capacities develop to their full strength. Nature via nurture, as Matt Ridley likes to say.

One implication for film is that humans would be likely to recognize film images without extensive training or even a lot of exposure. (Sermin Ildirar found this in the village study mentioned in my previous post). Some understanding of the actions and emotions we see onscreen may have quite specific neural sources, with “mirror neurons” as currently good candidates for grounding recognition and empathy. Other patterns of storytelling and style could be quickly learned, as they piggyback on our understanding of real-world knowledge of social interactions.

Having a battery of predispositions would make sense in evolutionary terms. We gain survival advantage by coming into the world ready to have our biases fine-tuned by experience. Increasingly, for some researchers, the puzzles of cinematic convergence and divergence find their ultimate explanations in human biological and cultural evolution.

Booked

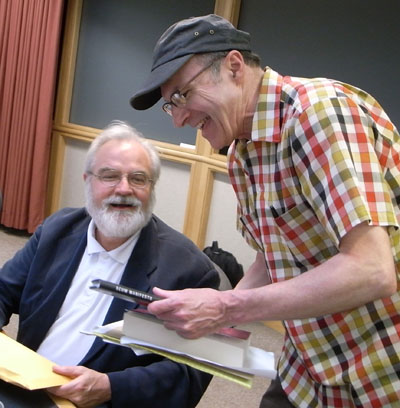

Noël Carroll and JJ Murphy, SCSMI convention June 2008.

I try never to take the present moment as a culmination or turning point in anything. Yet I can’t help noticing that the tenets of cognitive film studies chime in with three wider trends in our current intellectual life.

First, there is a burst of interest in the psychology of informal reasoning. A host of books talks about the shortcuts, heuristics, and predictable errors we make in everyday actions. Examples would be Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson’s Mistakes Were Made, Ori and Rom Brafman’s Sway, Gary Marcus’s Kluge, Jonah Lehrer’s How We Decide, Joseph T. Hallinan’s Why We Make Mistakes, and Dan Zariely’s Predictably Irrational. The flourishing area of behavioral economics, typified by Akerlof and Shiller’s Animal Spirits, is an outgrowth of this line of inquiry. Most of these books explore the cognitive biases that were brought to light by psychologists some time ago, but now emotion is seen as playing a central role.

A second thread in the cultural conversation involves neurology. Now that brain scanning has yielded more precise ways of tracking mental activity, our common-sense actions are seen to have surprising and tangled roots. Many of the books just mentioned draw upon neuroscience to identify the sources of cognitive biases. A rich survey of the neurological territory as currently mapped can be found in Human: The Science Behind What Makes Us Unique, by Michael Gazzaniga.

Then there’s the hottest topic of all, a renewed interest in evolutionary biology. A host of books is rolling out explaining and debating Darwinism. (By the way, Charles, happy centenary.) A good recent example is Jerry Coyne’s Why Evolution Is True. But the interest in evolution has given a new salience to evolutionary psychology, that area of inquiry that investigates how our minds have been shaped and constrained by adaptation and other evolutionary processes.

Evolutionary psychology came to prominence in the social sciences with the 1992 breakthrough book The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture. There Jerome H. Barkow, Leda Cosmides, and John Tooby flung down a challenge to traditional social science. Most researchers assumed that the mind was plastic and variable to a very large extent, both between cultures and within an individual’s lifetime. Culture held an irresistible sway over mental life. The essays collected in The Adapted Mind, particularly Tooby and Cosmides’ introductory manifesto, suggested that psychologists needed to consider evolution as a powerful source of explanations for mental activity. Steven Pinker’s The Blank Slate (2002) brought this line of thinking to a much broader public.

Although many humanists are proud of owing nothing to science, it’s curious that they often share traditional social sciences’ belief in a more or less blank slate. Virtually everything is culturally constructed; any biological givens are written off as nonexistent, unimportant, or uninteresting. But some humanistic scholars are starting to show that such factors possess both interest and explanatory value.

Studies linking art and literature to biological and cultural evolution are enjoying great prominence this year. Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct and Brian Boyd’s On the Origins of Stories have sparked a wide discussion of how the play instinct, mate selection, and other adaptations might shed light on narrative, music, and the visual arts.

Now, when cognitive and evolutionary models are the latest thing in literary studies, to be applauded or denounced by the MLA rank and file, it’s worth remembering that film studies has been plowing this field for quite some time. Some people would say that my Narration in the Fiction Film (1985) opened up this wing of film studies, but although that book drew on current developments in cognitive psychology, it didn’t outline a broad research program.

More far-reaching was Noël Carroll’s “The Power of Movies,” also published in 1985. Carroll’s seminal essay laid out a concise explanation of cultural convergence through cinema, or as he put it, how “movies have engaged the widespread, intense response of untutored audiences throughout the century.” Carroll’s critique of then-current film theory, Mystifying Movies (1985 again), developed the essay’s idea as a counterweight to psychoanalytic and neo-Marxist explanations for the power of popular cinema. The importance of attention, the role of visual techniques in shaping uptake, and the possibility of evolutionary sources for cinema’s appeals—these and other themes of today’s cognitive film research can be found in Carroll’s work of twenty-five years ago. I suppose that “The Power of Movies” is the cognitivist’s equivalent to Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.”

A turning point?

Joe, Barb, and Amy Anderson; SCSMI convention, June 2008.

Grand Theory in the humanities has prided itself on being cutting edge, yet it has ignored virtually all of the major developments in the human sciences, from Chomskyan linguistics through cognitive science and now evolutionary and neurological research. That ignoral can seem almost wilful. The 1990s saw a flourishing of cognitive film theory, such as Ed Tan’s study of emotion in cinema and Murray Smith’s study of characterization. Yet in 2006, when I was invited to London to give a paper surveying the perspective, I seemed to be speaking Martian. Two of the most distinguished senior film scholars in the UK said they couldn’t really comment adequately. The approach was all so new and unfamiliar!

If I had been haughty enough to offer two veterans of Screen some reading tips, I could have referred them to two compelling overviews. Paul Messaris’s Visual Literacy: Image, Mind, and Reality (1994) synthesized psychological and anthropological research on how people responded to media and concluded that there wasn’t yet any evidence that images and their normal combination were radically coded. Joseph Anderson’s Reality of Illusion (1998) showed how key questions of cinematic perception and comprehension have been addressed by empirical research in the social sciences. Joe and his wife Barbara were also pioneers in bringing evolutionary explanations to bear on cinematic problems, thanks to James J. Gibson’s “ecological” frame of reference.

In just the last year, three of the people deeply involved with SCSMI have published books that push the conversation in fresh directions. Assume that widely distributed propensities, either innate or converging through cross-cultural regularities, get fine-tuned by the specifics of cultural experience. How do these convergences and divergences emerge in films?

The most wide-ranging book comes from Torben Grodal. His first book, Moving Pictures (1999), was part of the last decade’s surge of cognitivist work. In Embodied Visions: Evolution, Emotion, Culture, and Film (Oxford), Grodal continues to explain our experience of film with the help of what we know about how brain areas are activated. At the center is the process that Torben calls PECMA (for Perception-Emotion- Cognition-Motor-Action). In this model, activation begins in brain areas dedicated to perception and flows on to associational and emotional centers, and then to areas providing cognitive appraisal. Here Grodal agrees with current thinking on the central role of emotion in processing information. Along with this “inner” account of cinematic response, Torben proposes an evolutionary account of enduring cinematic attractions. Romantic love, horror, and adventurous exploration all have evolutionary rationales.

The most wide-ranging book comes from Torben Grodal. His first book, Moving Pictures (1999), was part of the last decade’s surge of cognitivist work. In Embodied Visions: Evolution, Emotion, Culture, and Film (Oxford), Grodal continues to explain our experience of film with the help of what we know about how brain areas are activated. At the center is the process that Torben calls PECMA (for Perception-Emotion- Cognition-Motor-Action). In this model, activation begins in brain areas dedicated to perception and flows on to associational and emotional centers, and then to areas providing cognitive appraisal. Here Grodal agrees with current thinking on the central role of emotion in processing information. Along with this “inner” account of cinematic response, Torben proposes an evolutionary account of enduring cinematic attractions. Romantic love, horror, and adventurous exploration all have evolutionary rationales.

On both fronts, the book tries to balance the convergence/ divergence tendencies. Take My Neighbor Totoro.

The film is clearly influenced by its Japanese origin, from the use of Shinto gods to the rice fields and sliding doors. But the fact that children all over the world are fascinated by the film is only loosely related to those cultural specificities. . . . Miyazaki uses a series of devices that tap into innate and universal mental mechanisms and emotions. Central, of course, is the fascination with the soft, organic counterintuitive agent Totoro, who provides attachment security and empowerment for the little girl, Mei, in the absence of the parents.

Torben goes on to discuss how Miyazaki exploits our interest in “counterintuitive” phenomena, like ghosts and gods, in the figure of a cat who is also a bus.

While Embodied Visions offers a very broad theoretical framework, Carl Plantinga’s Moving Viewers: American Film and the Spectator’s Experience (University of California Press) focuses on Hollywood cinema and how it arouses emotions. Plantinga, who also contributed to the 1990s discussions, surveys the literature on emotion and explores varieties of emotions in film viewing. He makes fruitful distinctions between “long-range” emotions, like suspense, and those brief and intense feelings, like surprise and disgust.

While Embodied Visions offers a very broad theoretical framework, Carl Plantinga’s Moving Viewers: American Film and the Spectator’s Experience (University of California Press) focuses on Hollywood cinema and how it arouses emotions. Plantinga, who also contributed to the 1990s discussions, surveys the literature on emotion and explores varieties of emotions in film viewing. He makes fruitful distinctions between “long-range” emotions, like suspense, and those brief and intense feelings, like surprise and disgust.

Perhaps more interesting, Carl suggests that while sympathetic narratives evoke compassion and pity, distanced narratives evoke cooler feelings, like respect or disdain. This distinction allows him to deny that the common claim that the aesthetic distance we find in Antonioni or Angelopoulos is unemotional; these artists simply deal in different emotions. The distinction also enables him to puncture the belief that Hollywood offers only sentimental hogwash.

It might be thought that sympathetic narratives are the norm in Hollywood. Yet distanced narrative is pervasive in Hollywood, as it is in the “art” cinema. The distanced mode rejects the evocation of strong sympathy for characters—sympathies that are sometimes dismissed as sentimentality—in favor of a more distanced, critical, sometimes humorous, and occasionally cynical perspective.

Plantinga’s examples are action films like The Hunt for Red October, which evokes admiration for gallant stoicism, ironic comedies like Raising Arizona, and puzzle films like House of Games and The Usual Suspects.

One of Carl’s key points is that sympathetic narratives must evoke some negative emotions, when their characters are hit by misfortune. So melodrama is the sympathetic narrative par excellence. Moving Viewers closes with a sensitive discussion of how a film can orchestrate negative emotions in complicated ways, focusing on disgust as it is evoked in films as different as Mask and Polyester.

A comparable concern for how culture can fine-tune cross-cultural tendencies is set forth by Patrick Colm Hogan in Understanding Indian Movies: Culture, Cognition, and Cinematic Imagination (University of Texas). Hogan is an expert on Indian literature and aesthetics; I called him in to help me understand Slumdog Millionaire in an earlier entry. Hogan is also a major narrative theorist. His The Mind and Its Stories is a powerful study of cross-cultural narrative structures and their relation to prototypical emotions.

A comparable concern for how culture can fine-tune cross-cultural tendencies is set forth by Patrick Colm Hogan in Understanding Indian Movies: Culture, Cognition, and Cinematic Imagination (University of Texas). Hogan is an expert on Indian literature and aesthetics; I called him in to help me understand Slumdog Millionaire in an earlier entry. Hogan is also a major narrative theorist. His The Mind and Its Stories is a powerful study of cross-cultural narrative structures and their relation to prototypical emotions.

Understanding Indian Movies shows how those universal plot structures gain richness and emotional force through their encounter with Indian traditions and current social conditions. For example, the sacrificial plot found in all cultures is particularized in Santosh Sivan’s The Terrorist. The film transforms the standard plot for the sake of ideological point and emotional force, modeling its suicide-bomber tale on the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi. “The contemporary history depicted by the film was already emplotted in a prototypical narrative form by the people who made that history.”

Hogan’s book is not as localized in its concerns as the title might imply. It’s not only about how to watch Indian movies but also about how to do cognitive studies of media. For instance, Patrick often pauses to criticize over-simplified evolutionary explanations, and he urges that such explanations be used cautiously. But he nonetheless defends the overall convergence/ divergence perspective.