Archive for the 'Film theory: Cognitivism' Category

Minding movies

DB here:

When we watch films, our bodies and minds are engaged at a great many levels. Nobody doubts this claim. The interesting questions are: What forms does this engagement take? What gives movies the ability to seize our senses, prod our minds, and trigger emotions? How have filmmakers constructed films so as to tease us into such activities? What, to use a phrase from the philosopher Noël Carroll, creates the power of movies?

On this blogsite, I’ve touched on such questions in concrete cases—how eye movements shape our uptake of story information (here and here), how suspense can be created and sustained (here). Those are just small-scale samples of what is, to me, an exciting and promising way of studying certain aspects of cinema. That research trend is growing substantially, and an upcoming event on our home turf marks a new phase.

In June, the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image will hold a conference here in Madison. This organization was officially created in 2006. Its membership grew out of an informal group of scholars who had been meeting every couple of years since 1997. The meetings have been stimulating affairs, bringing together film historians and theorists, filmmakers, philosophers, and social scientists. Now we’re a full-fledged, incorporated association. We have annual membership dues (cheap at $25), a slate of officers, and a set of bylaws. The Society’s conferences will become annual next year, when we convene at the University of Copenhagen.

You can learn details about the organization here, and you can scan the conference schedule here. There’s also information about getting to Madison and visiting local attractions. (I recommend The House on the Rock.) The earlier incarnation of our group, The Center for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image, has a rather full archive here.

As president of SCSMI, I’ve had my say about the organization’s remit on the webpage. I’m using today’s blog entry to gesticulate toward some ways that the organization tries to advance our understanding of films, filmmaking, and film viewing. I’ll also shamelessly promote our event.

What is this fascinating new film theory known as cognitivism?

There are, roughly, two ways to think about doing film theory. One way is to look at a body of research or reflection in some established area (history, philosophy, psychology, etc.) and ask: What can it tell me about movies? So you might look at Freudian psychoanalysis or Gestalt perceptual psychology as a whole and then home in on ideas that seem to have relevance to cinema.

The other way to do film theory is to look closely at some filmic phenomenon and ask: What’s the best way to understand this aspect of movies? Your reading and thinking might then lead you to adjacent fields of inquiry for help. In the first instance, you start broad and move to particular cases. In the second, you start with particular cases and explore what broader ideas or information can shed light on them.

On the whole, academic film studies of the 1970s and 1980s started from the big-picture end. Several scholars decided, on various grounds, that psychoanalysis (a mixture of Freudian and Lacanian versions), provided a powerful explanatory system for virtually all human activity. The ideas of that system were then mapped onto many humanities disciplines, and then applied to particular instances of literature, the visual arts, and cinema. Many times, the big system became a doctrinal whole, a Theory of Everything, that was unquestioningly accepted.

In a 1989 essay called “A Case for Cognitivism” (available online here), I suggested that Freud did not intend his theories to become this sort of all-encompassing doctrine. And whatever Freud thought, in that essay and a later one for Post-Theory I argued that it’s more fruitful to develop film theories in a middle-level fashion, shifting from concrete problems to broader explanatory frameworks. My collaborator Noël Carroll called this focus on particular problems “piecemeal” theorizing.

It was through middle-level, piecemeal thinking that I first became interested in the cognitive sciences. During the early 1980s, I was concerned to understand how films told their stories. This process was usually called narration. From the start it seemed clear to me that filmic storytelling doesn’t work unless the spectator does certain things. We make assumptions, frame expectations, notice certain things, draw inferences, and pass judgments on what’s happening on the screen.

Film narratives are designed for just this sort of active pickup. I was interested, then, in how certain traditions of filmmaking shaped that pickup—by parceling out story information, composing shots, structuring scenes, and so on. Going beyond those particular traditions, what general capacities of spectators enabled us to understand the twists and turns of a film’s action, as presented by the movie?

During the 1960s Christian Metz had posed my question in a precise and provocative way—“We must understand how films are understood”—and had used it to found his initial version of a semiotics of cinema. But by the early 1980s, it wasn’t a question that much exercised people working in the dominant paradigm of the moment, psychoanalysis. Moreover, I was and remain skeptical of the psychoanalytic framework; I don’t think it has very solid scientific support.

So I began reading in other domains of psychology. At this point, the “cognitive sciences” were coming into their own as a result of work in linguistics, psychology, and anthropology. I didn’t have the benefit of Howard Gardner’s masterful state-of-play survey The Mind’s New Science (1985), but I saw some of the convergences he was pointing out. Perceptual psychology, social psychology, the shortcuts and shortcomings of informal reasoning, studies in classification and story comprehension–all these illuminated my central questions.

Characterizing, quick and dirty

The answers I proposed to those questions showed up in Narration in the Fiction Film (1985). Nowadays we’d call it an attempt at reverse engineering. In many instances, that book argued, features of narratives in film seemed designed to solicit activities that research in the cognitive sciences has studied. Here’s one example.

The first time we encounter a character in a narrative, we tend to form an immediate, fairly fixed judgment about what sort of person she or he is. Why is this? Why don’t we suspend judgment and wait until we have more information? At least two reasons.

First is what psychologists call the primacy effect, the likelihood that the first item or few items in a series tend to form a benchmark for what will follow. Here are two multiplication exercises:

8 x 7 x 6 x 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1 = ?

1 x 2 x 3 x 4 x 5 x 6 x 7 x 8 = ?

Give a person just one of the problems and ask him or her not to do the math but to quickly offer a rough estimate of the size of the result. What happens? People given the first problem tend to give bigger estimates than those given by people who see the second problem. Even though the product is exactly the same, the order of presentation—starting with large or small numbers—seems to have biased people toward different results. The initial items become a rangefinding device for later judgments.

A second reason for our snap judgments about characters stems from a well-supported finding of social psychology. We tend to size up other people using a rule of thumb, or heuristic, that attributes their actions to personality rather than to circumstances. If someone acts bossy in a meeting, we’re inclined to say that the person has an aggressive nature. But if you ask the person why he or she came on so strong, the answer is likely to be “I was having a bad day,” “The responses I was getting were just so lame,” “The pressures of those meetings are intolerable,” and so on. This is called the fundamental attribution error. We tend to assign behavior to character traits rather than take into account contextual factors. We are biased toward believing that others’ misbehavior is due to their temperament while ours was forced by circumstances beyond our control.

In real life, the primacy effect and the fundamental attribution error can be quite unfair ways of coming to conclusions, and they can lead us astray. But filmmakers and other storytellers, being intuitive psychologists like the rest of us, realize how strong these heuristics are, so they design their stories so as to make use of them. Usually, when a character walks into the story world, he or she is characterized by signaling key traits right off the bat.

Consider Back to the Future (released the same year as NiFF was published). It might have begun with Marty McFly skating down the street for several minutes on the way to Doc’s laboratory. Instead, the narration introduces Marty by showing him cranking up the lab’s amplifier to overdrive. He strikes a star pose, hits a guitar chord, and is blasted off his feet. He’s shaken up but awestruck: “Whoa. . . Rock and roll.” We now assume that Marty likes to take risks, that he’s committed to his music, that he’s a bit preening, and that he can bounce back. Likewise, before Marty comes in, during the opening shots exploring the lab, we get information about Doc as well, though more indirectly. For both characters, the narration encourages us to leap to conclusions that will be confirmed again and again in the story that follows.

Sometimes, though, filmmakers thwart our propensities by either neutralizing the initial cues (we don’t know how to read the character) or offering strong ones that are later countermanded (we’ve been led to misread the character). Preminger offers wonderful examples of both possibilities in Anatomy of a Murder. Either way, the filmmaker is still exploiting the primacy effect and the fundamental attribution error, but in order to yield different experiences. Meir Sternberg’s superb book, Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction (1978), points out such strategies and explores in detail what he called, “the rhetoric of anticipatory caution”—the ways that novelists trigger the primacy effect only to force us to reevaluate our snap judgments. Sternberg was, I think, one of the first narrative theorists to bring cognitive research to bear on storytelling strategies.

I found, in short, that experimental results in the cognitive sciences could explain, in a fairly direct way, many of the tactics that stories use to engage us. Contrary to what my Wikipedia entry implies, I’m not a cognitivist 24 hours a day; many of the research questions I tackle don’t depend on such assumptions. Still, since NiFF, I’ve revisited them a few times. Making Meaning (1988), for example, tried to show that a lot of cinematic interpretation is explainable in cognitive terms.

Most recently, some essays in Poetics of Cinema (2007) draw on psychological and anthropological research to clarify why films use certain formal strategies. For instance, what aspects of Mildred Pierce mislead us about what is happening, and how are we led to misremember those aspects? Why do actors stare at each other in a way we seldom see in life? And why don’t they blink the way we do? Another essay in the collection, “Convention, Construction, and Cinematic Vision,” moves to broader terrain. It argues that a great deal of our understanding of films relies not on codes particular to cinema (contra the semiotic tradition) but rather on our everyday inference-making habits and skills.

The cognitive turn

Written in 1982-83, Narration in the Fiction Film leaned heavily on what was then called “New Look” psychology, the first wave of cognitive research in psychology. The pioneers of that program, such as Jerome Bruner, R. L. Gregory, Ulrich Neisser, and others, emphasized the mind’s role in actively building up structures of meaning on the basis of incomplete or ambiguous information. So my claims that films cue us to flesh out their action, invoke schemas (knowledge structures), ask us to reorganize story order, and to fill in missing bits—all stem from that research program. The art historian E. H. Gombrich, another big influence on me, was perhaps the first person to see how New Look psychology could inform theorizing in the humanities.

In the late 1990s, cognitively inflected film theory really took off, and in directions that shaped the growth of SCSMI. The first avatar of the SCSMI was founded by Joseph and Barbara Anderson. Joe and I were graduate students together at Iowa in the early 1970s, where he wrote a dissertation on binocularity in the cinema, and later we worked together here at Madison, where Barb was a grad student. Joe taught a course in film perception that I sat in on occasionally, and it was a revelation. When NiFF came out, Joe (by then a film producer) felt encouraged to go on with his own work, and the result was The Reality of Illusion (1998). It proposed an alternative to the New Look orientation, grounded in J. J. Gibson’s theories of ecological perception. Since then, Joe and Barb have published two anthologies, with contributions from SCSMI members.

At the same period, Torben Grodal published Moving Pictures (1997) a comprehensive theory of cinema grounded in the cognitive sciences, with particular focus on brain functions. Torben was also a founding member of the SCSMI group.

Since 2000, publications in the area have increased markedly, parallel to the growth of cognitive studies in literature and other areas. I hope to discuss some of these books and articles in a later blog.

Broadly, cognitive film theory has tracked the development of the cognitive sciences. After the New Look and ecological frameworks, we’re seeing more emphasis on evolutionary psychology and neuroscience as explanatory forces. Film scholars who talk about adaptive fitness and mirror neurons are still, for the most part, doing middle-level, piecemeal theorizing—trying to explain particular processes by appeal to what scientific research has brought to light. None, I think, expects cognitivism to provide a Big Theory of Everything.

Early on, Noël, I, and others sought to show that the cognitive perspective offered better explanations for some aspects of cinema than the dominant psychoanalytic approach. We were sometimes chastised for being pugilistic and polemical. Yet interestingly, nobody responded to our arguments, let alone replied at the same level of detail. The situation reminded me of Godard’s response to people who complained that Letter to Jane (1972) mistreated Jane Fonda. His reply was: “I merely wrote her a letter, but she never answered.”

In the years since, I have yet to see a substantive critique of the cognitive research tradition in film studies. The only extended argument I know of isn’t really focused on cognitivism and is surprisingly flimsy. (My response to it is here.)

Advocates for Poststructuralist or Cultural Studies perspectives sometimes dismiss the cognitive framework as “common sense.” But common sense is in the eye of the beholder, and there’s no reason to assume that flagrantly uncommensical claims are any more likely to be accurate than those which seem intuitively right. In doing research, we just try to ascertain the evidence for any belief, commonsensical or not. The primacy effect might seem simply to rely on the old saw, “First impressions matter,” but it’s good to know that at least one commonplace is well supported. By contrast, the fundamental attribution error doesn’t on the face of it seem either common sense or not. It’s something that our folk psychology doesn’t guide us toward or away from. It’s actually a fresh discovery about some habits of our minds.

Moreover, a great deal of cognitivism flouts what some might take as common sense. Before Chomsky, most intellectuals thought that language was social through and through. He was able to show that certain features of it, including syntax, are likely to be part of our biological endowment. A lot of cognitive social psychology has been dedicated to showing how common-sense inferences are often illogical. These findings are now being popularized in books like Cordelia Fine’s A Mind of Its Own: How Your Brain Distorts and Deceives, and Thomas Kida’s Don’t Believe Everything You Think (from which my multiplication example comes). As for humanists’ suspicion of science, I address that unfounded fear in the introduction to Poetics of Cinema. If you prefer big-picture arguments about the issue, try Edward Slingerland’s new book.

Movies on the brain

The real debate on cognitivism in film studies has yet to take place. Meanwhile, the cognitivists keep plugging away. Over the years, the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image has attracted, broadly, three sorts of persons. All are represented in our upcoming conference.

*There are the film-trained academics like me, who have branched out into cognitive film theory to illuminate particular research projects. Our June gathering includes a great many such scholars, many of them pioneers in the cognitive perspective like the Andersons, Carroll, Grodal, Murray Smith, Carl Plantinga, Patrick Colm Hogan, et al.

*There are the psychologists, who are interested in explaining the psychological mechanisms of cinema. They tend to focus on particular phenomena, like eye movements, cutting, or other triggering processes, and they study the effects at various levels, from perceptual response to brain-scanning. Their great predecessor is Julian Hochberg, who studied cinema as a sort of stage show that displayed psychological processes with particular clarity. A magisterial collection of Hochberg’s work, In the Mind’s Eye, has recently been published. At our June gathering, an entire thread is largely devoted to psychological research into cinematic uptake. Our two plenary speakers, Uri Hasson of NYU and Dan Levin of Vanderbilt, also represent this tradition.

*Then there are the philosophers. Most are concerned with art and literature, and most incline to an Anglo-American form of conceptual analysis. These scholars come to SCSMI because they are of a cognitivist bent, or because they want to argue with cognitivist work, or because this is a useful forum for the sort of film-based questions they want to pursue. The June event includes many of the most prominent philosophers of film, and a panel session is devoted to critiques of Noël Carroll’s recent book The Philosophy of Motion Pictures.

Visit our schedule page, and you’ll get a sense of how varied this work is. Speakers are talking about everything from editing patterns to the effects of digital technology on filmic perception. The participants consider propaganda, melodrama, TV series, and videogames. There are presentations on the emotional dimensions of horror and on the ways that color works in particular movies. How do viewers who have never seen films before understand cutting? In what sense is film content fictional? How does the language of film theory affect the way we theorize? Is there something inherently filmic that sets cinema apart from other media?

Cognitivism isn’t a Big Theory of Everything; nobody has a clue about how these diverse research programs would fit together. The variety is what makes it fun. I think that anybody who wants to know more about movies would find something worthwhile at the Madison event, not least the opportunity to shmooz. And there’s The House on the Rock.

The evidence is mounting. Cognitivism is cool.

PS 17 April: This line of thought strikes a chord in Lee Marshall, who offers encouragement at Screen International here.

Angles and perceptions; with a note on Thai censorship

Hide your face

“Angles alter perceptions,” notes a recent Newsweek story. You bet, as we say in Wisconsin. But intriguing evidence emerges from new research into videotaped confessions.

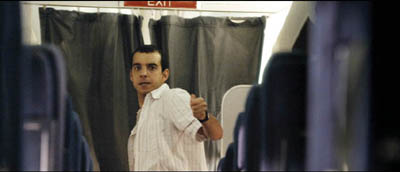

Over 500 jurisdictions now record confessions on video, we’re told. In virtually all instances, there’s only one camera, and it shows only the accused. That means, in movie terms, there are no reverse shots of the questioner.

What difference does it make? Quite a lot, it seems.

In Newsweek‘s words, “When a camera shows only a suspect’s face, studies show, potential jurors are more likely to believe the confession was voluntary and the suspect guilty than when it shows the faces of both suspect and interrogator.” The problem may also infect judges. Experiments conducted by G. Daniel Lassiter at Ohio University found that a sample of 21 judges appraised the confessions as more voluntary when the camera framed only the confessor and didn’t show the police officer.

The obvious worry is that we can’t be sure that the confession is voluntary if we don’t get any sight of the questioner. To take an extreme, but not fanciful, possibility, maybe the person offscreen is holding a weapon. But even if the questioner isn’t threatening the confessor, his or her facial expression will help us appraise the whole situation more fully. Is s/he reacting with sympathy, anger, or neutrality? Do the questioner’s facial expressions set a context for the questions asked? We can’t know, and this absence of knowledge may encourage us, by default, to side with authority and presume that the confession is genuine.

In fiction films, sometimes the camera doesn’t give us the reverse angle. It may simply dwell on one character, often when she or he is delivering a monologue. A close analog to the videotaped confession occurs in Truffaut’s 400 Blows when an offscreen therapist questions the boy Antoine about his life.

Several effects flow from Truffaut’s choice of this technique. The handling suggests a quasi-documentary objectivity in recording Antoine’s replies. Making the questioner unseen suggests that she won’t become a significant character, rather a voice that typifies the impersonal authority of the detention facility. The fact that the questioner is a woman reminds us of Antoine’s relation to his mother, an important topic in the interview. In all, this strategy concentrates on Antoine, letting us see new sides of his past and his mind.

In other scenes, I’ve noticed that suppressing the reverse angle not only showcased the character we see but also rendered the scene’s action more suspenseful or ambiguous. Recall the famous first shot of The Godfather, which concentrates on the mortician and refuses to supply the reactions of Don Vito.

The shot gives full sway to Bonasera’s monologue. At the same time, by slowly zooming back, the shot creates a growing suspense. To whom is he speaking? What is the listener’s reaction? Only at the end of Bonasera’s plea, when he rises to whisper in Vito’s ear, does Coppola supply the view of Don Vito—a big theatrical entrance for this character and the actor playing him.

Less operatic is an early scene in Sauvage Innocence (2001), by Philippe Garrel. The filmmaker François is going over his dead wife’s belongings, which his friend has preserved. Garrel gives us an establishing shot of the action, then, as the friend continues to talk, the camera concentrates on Francois’s reaction to the letters, poems, and photographs. Although his expressions are somewhat ambivalent, at least we can see them.

But in the next scene, a single shot lasting about seventy-five seconds, Garrel withholds the reverse angles that we’d normally get when his protagonist speaks. The camera favors the friend, a minor character, who asks questions about François’s new film while feeding a baby. François replies that he’s having trouble finding a producer, and if this last opportunity fails, the project will be over.

Garrel doesn’t choose to reveal François’s expression as he reports this critical state of affairs: no reverse shots. We must infer his emotional state from his voice, his pauses and sighs, and his postures as he replies, rises, and sits down.

At most we can assume that he’s dispirited, perhaps because of his film’s slim prospects and the reminder of his dead wife.

In the scene, there’s one glimpse of his face, as he turns slightly, and—Tim Smith might be able to confirm this—I’d bet that most viewers zero in on him at that moment. (The movement is centered in the frame as well.) But that view is pretty brief and uninformative.

Overall, we have to infer François’s attitude from other cues than his expressions, and the results aren’t clear-cut. It seems to me that Garrel’s choices here are typical of one strain of “art cinema.” This storytelling tradition aims to make scenes somewhat indefinite in their meaning and to leave considerable room for spectators to play with various implications of the action.

Cutting and Social Intelligence

Some years ago I developed some ideas about the importance of shot/ reverse shot cutting in an essay called “Convention, Construction, and Cinematic Vision.” (1)

One school of thought in film studies holds that cinematic conventions are wholly arbitrary social constructions. This implies that we have to learn to watch movies, just as we have to learn any arbitrary sign system, like Morse code or written languages. My essay argued that cinema, like painting, offers a continuum of conventions: some require a lot of exposure to learn, while others require much less. The easiest ones rely on regularities of everyday experience. I tried to show that shot/ reverse shot is a fairly easy convention to learn because it mimics the alternation between speaker and listener that we find in the turn-taking of ordinary conversation.

As my examples suggest, even if person A is doing all the talking, we don’t fully understand the scene if we can’t also monitor the reactions of B. By contrast, the shot/ reverse-shot patern keeps a running tab of the dynamics of the conversation. When a director wants to suppress information about B’s response, deleting the reaction shot can create uncertainty or suspense.

Confessions aren’t fictional films; we don’t assume that they use much staging. I’d argue that in videotaped interrogations any uncertainty about the listener’s reactions is quelled by our assumption that the officer is neutral or that any emotion she expresses has no effect on the confession. In other words, during a videotaped confession, any reaction on the part of B is presumed, perhaps wrongly, to be irrelevant. But in watching a fiction film, we tacitly assume that the director has suppressed B’s reaction in order to shape our experience in a particular way. The use of shot/ reverse shot, then, has a narrational function, governing the flow of story information.

We might posit this maxim of social intelligence: We understand an interchange more fully when we can see both participants’ responses to it, moment by moment. This notion underpins our old friend shot/ reverse shot, a convention that requires no specialized learning beyond watching and participating in conversations in real life. The absence of the reverse shot in videotaped confessions forces us to fill in one side of the conversation, and what we fill in may not be warranted.

Lassiter suggests a subtler effect of single-shot confessions. He has specialized in what psychologists call “illusory causation,” as explained in a 2002 press piece.

Criminal interrogations are customarily videotaped with the camera lens zeroed in on the suspect. Psychological research has shown that objects that are the focus of attention, are “more likely than less conspicuous objects to be judged the originators of a physical event, even when there is no objective basis for such a conclusion,” said G. Daniel Lassiter, author of the study. This phenomenon is referred to as “illusory causation.”

So by concentrating wholly on the suspect, the framing attributes a greater causal power to him or her than would a shot/ reverse-shot sequence.

I can’t at the moment see how this might come into play in a fiction film. In both of my major examples here, Bonasera and the baby-feeding friend have less causal power than the character whose response is suppressed. I suspect that the story context of film scenes provides our main sense of who has the causal power, which film style can reiterate or undercut.

Censoring Syndromes

Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Syndromes and a Century was one of the best new films I saw last year. It has played at Venice, Vancouver (my quick remarks are here), Hong Kong, and other major festivals. It also won the best editing award at the Asian Film Awards. You can read the Variety review here. Jeff Reichert’s exhilarating appreciation appears, in keeping with the theme of the above entry, at Reverse Shot.

But now Apichatpong has withdrawn the film from theatres because local censors have demanded cuts. The objectionable portions include shots of monks playing with toys and a doctor kissing his girlfriend in a hospital. Details are available at Variety and Limitless Cinema. According to Screen Daily (not available free online):

Apichatpong questions why many other Thai and foreign films which contain excessive violence, nudity, coarse language, crude jokes on other ethnic groups, and monks doing stupid things did not suffer the same fate.

Below I reprint Apichatpong’s most recent statement and information about a petition that’s available online.

Free Thai Cinema Movement Petition

Statement by Apichatpong Weerasethakul with Bioscope, the Thai Film Foundation, Thai Film Director’s

Association, and Alliances.

I am saddened by what has happened to my film. However, this is not the venue to try to make SYNDROMES AND A CENTURY shown in Thai theaters. It is not my intention to use this opportunity to promote my work.

But, it is time to seriously think about what is going on with our censorship laws, so that the next generation of filmmakers will not face the same problems as us, and so that the Thai audiences can truly achieve a freedom of choice.

It is time we discuss whether all films, before being released, should be seen by the Buddhist council, doctors council, teachers council, labor council, the army, pet lovers group, taxi union, representatives from other foreign countries etc? Or, is it easier to turn our nation into a Fascist state so that we can live in harmony and don¹t have to waste time talking about democracy?

The system of the Thai Board of Censors needs to be evaluated. Their members’ relevancy and efficiency needs to be questioned, and we should decide whether the laws should be changed.

I would like to ask you to reflect on the censorship practices in our country and to provide us with advice at

http://www.petitiononline.com/nocut/petition.html

Later on, this Petition will be submitted to the Thai government. Your support will be a great contribution to our fight for one of our most basic rights – that of freedom.

I am grateful for your time and your participation. Thank you very much.

Warmest Regards,

Apichatpong Weerasethakul

KICK THE MACHINE FILMS Co., Ltd.

(1) It’s not available online; it was published in Post-Theory and will be reprinted in my forthcoming Poetics of Cinema collection.

Trims and outtakes

Some jottings from DB:

Continuity Boy meets Badgers

Tim Smith, who studies how we perceive film, recently visited our department at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. His talk was splendid.

Tim Smith, who studies how we perceive film, recently visited our department at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. His talk was splendid.

Tim studies the ways we scan shots and shift our attention across cuts. His talk was illustrated with film sequences showing little yellow dots swarming around the frame; these indicate the points in the image where his subjects’ glances landed. Tim shows pretty conclusively that there’s a consensus about where viewers look during a shot (faces, movement, the center of the frame) and that classical continuity cuts can push our attention to and fro with remarkable facility. One of the most surprising findings was that viewers are often starting to shift their attention to a new frame area just before the cut comes. Why? Tim has some intriguing suggestions.

Tim also showed some remarkable effects of what I’ve called “intensified continuity,” the fast-cut close-ups that characterize so much current cinema. Because these passages leave no time for visual exploration, viewers seem to revert to a cursory test for the shot’s basic point, usually at the center of the frame. Tim’s examples from Requiem for a Dream were fascinating, showing how real viewers are playing catchup in very fast-cut sequences.

This is rich and promising research, showing once more that Leonardo da Vinci, Eisenstein, and a few others were right to think that many creative choices in the arts can be studied with the tools of science. It also shows that filmmakers, like other artists, are seat-of-the-pants psychologists, achieving complex effects through decisions that “feel right” and that they have no need to explain theoretically. That’s our job.

For Tim’s narrative of his visit, and a lot more about his research program, go here. For something not quite completely different, about eye-tracking, print ads, and crotches, go here.

Six more from RKO

The enterprising folks at Turner Classic Movies have discovered six RKO films that have been missing for many years. It’s a harvest of 1930s titles, promising some intriguing situations (e. g., Ginger Rogers as a telemarketer) and carrying the names of directors like William Wellman, John Cromwell, and Garson Kanin.

A Man to Remember (1938; at the top of this page), Kanin’s first film, is the only one of the batch I’ve seen so far. One of the New York Times‘ ten best films of 1938, it went virtually unseen until a print surfaced at the Netherlands Filmmuseum in 2000. A Man to Remember is a portrait of a small-town doctor who tends to the poor and lets others, chiefly a cadre of corrupt businessmen, take credit for his good works.

It could all be mawkish, but Edward Ellis plays the doctor as a testy guy who levels with his patients and wins the town’s respect through quiet cussedness. The performance echoes Ellis’ crabby but likable inventor in The Thin Man (1934). Dalton Trumbo’s script has an intriguing flashback structure, less bold than in The Power and the Glory (1933) but still ambitious for a B project.

The six RKO discoveries are screening on April 4th as an ensemble, then they’re scattered through the rest of the month. All should be worth checking out. Once more TCM proves itself the film-lover’s channel of first choice.

Bambi or kitty?

Two recent books support the claim that New Hollywood, or New New Hollywood, is at bottom in debt to old Hollywood. (The full case is presented in The Way Hollywood Tells It and Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood.)

David Mamet’s Bambi vs. Godzilla: On the Nature, Purpose, and Practice of the Movie Business (Pantheon) is as pungent and eccentric as you’d expect, but also deeply traditional in its storytelling advice. A movie’s characters must have goals, and over the course of three acts they achieve them, or definitively don’t. The Lady Eve is Mamet’s model of this construction. Furthermore, three questions structure every scene: Who wants what from whom? What happens if they don’t get it? Why now? In wide-ranging essays, Mamet pays tribute to the craftsmanship of below-the-line talent and celebrates movies as various as The Diary of Anne Frank and I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead (whose protagonist is remarkable for “his personification of enigma”).

David Mamet’s Bambi vs. Godzilla: On the Nature, Purpose, and Practice of the Movie Business (Pantheon) is as pungent and eccentric as you’d expect, but also deeply traditional in its storytelling advice. A movie’s characters must have goals, and over the course of three acts they achieve them, or definitively don’t. The Lady Eve is Mamet’s model of this construction. Furthermore, three questions structure every scene: Who wants what from whom? What happens if they don’t get it? Why now? In wide-ranging essays, Mamet pays tribute to the craftsmanship of below-the-line talent and celebrates movies as various as The Diary of Anne Frank and I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead (whose protagonist is remarkable for “his personification of enigma”).

Mamet adds a fair amount on editing, supplementing the remarks in his Pudovkin-flavored On Directing Film. For instance: “At the end of the take, in a close-up or one-shot, have the speaker look left, right, up, and down. Why? Because you might just find you can get out of the scene if you can have the speaker throw the focus. To what? To an actor or insert to be shot later, or to be found in (stolen from) another scene. It’s free. Shoot it, ’cause you just might need it.”

Mamet bemoans the script reader, whose motto must be Conform or Die. By contrast, Blake Snyder makes conformity seem fun and–well, if not easy, at least attainable. His Save the Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting You’ll Ever Need (Michael Wiese Productions) bulges with formulas, recipes, and gimmicks.

Like Kristin and me, Snyder treats the Second Act as really two sections, broken by a midpoint. But for him three acts are just the beginning. He demands that there be an Opening Image (on script p. 1), Theme Stated (p. 5), Catalyst (p. 12) and on and on until we get the Finale (pp. 85-110) and the Final Image (p. 110). This is the most strictly laid-out cadence I’ve seen; it would be fun to see if actual scripts adhere to it. In addition, you get catchy tips like Save the Cat! (show the protagonist doing something likable early on) and the Pope in the Pool (burying exposition). Snyder includes a list of the most common screenplay errors. An enjoyable read with some hints about construction I hadn’t encountered before.

Like Kristin and me, Snyder treats the Second Act as really two sections, broken by a midpoint. But for him three acts are just the beginning. He demands that there be an Opening Image (on script p. 1), Theme Stated (p. 5), Catalyst (p. 12) and on and on until we get the Finale (pp. 85-110) and the Final Image (p. 110). This is the most strictly laid-out cadence I’ve seen; it would be fun to see if actual scripts adhere to it. In addition, you get catchy tips like Save the Cat! (show the protagonist doing something likable early on) and the Pope in the Pool (burying exposition). Snyder includes a list of the most common screenplay errors. An enjoyable read with some hints about construction I hadn’t encountered before.

Speaking of screenplays….

J. J. Murphy is an old friend (we went to grad school with him in 1971) and colleague (he teaches in our department). Renowned as an experimental filmmaker, he has turned his attention to American indie cinema. His new book Me and You and Memento and Fargo: How Independent Screenplays Work offers an in-depth analysis of several recent films. J. J. shows how they obey mainstream conventions of construction while still innovating in other ways. I especially like his discussions of Hartley’s Trust, Korine’s Gummo, and Lynch’s Mulholland Dr. I think it’s a book that everyone interested in current American cinema would find stimulating.

You can find out more about it, and read an excerpt, here. Congratulations, J. J.!

This is your brain on movies, maybe

United 93.

From DB:

Normally we say that suspense demands an uncertainty about how things will turn out. Watching Hitchcock’s Notorious for the first time, you feel suspense at certain points–when the champagne is running out during the cocktail party, or when Devlin escorts the drugged Alicia out of Sebastian’s house. That’s because, we usually say, you don’t know if the spying couple will succeed in their mission.

But later you watch Notorious a second time. Strangely, you feel suspense, moment by moment, all over again. You know perfectly well how things will turn out, so how can there be uncertainty? How can you feel suspense on the second, or twenty-second viewing?

I was reminded of this problem watching United 93, which presents a slightly different case of the same phenomenon. Although I was watching it for the first time, I knew the outcomes of the 9/11 events it portrays. I knew in advance that the passengers were going to struggle with the hijackers and deflect the plane from its target, at the cost of all their lives. Yet I felt what seemed to me to be authentic suspense at key moments. It was as if some part of me were hoping against hope, as the saying goes, that disaster might be avoided. And perhaps the film’s many admirers will feel something like that suspense on repeated viewings as well.

Psychologist Richard Gerrig in his book Experiencing Narrative Worlds calls this anomalous suspense: feeling suspense when reading or viewing, although you know the outcome.

Anomalous suspense: Some theories

Anomalous suspense has been fairly important in the history of film. One of the most famous instances in the early years of feature film is the assassination of President Lincoln in Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915). Griffith prolongs the event with crosscutting and detail shots in a way that promotes suspense, even though we know that Booth will murder Lincoln. Anomalous suspense, of course, isn’t specific to movies; we can feel this way reading a familiar book or watching a TV docudrama about historical events. Young children listening to the story of Little Red Riding Hood seem to be no less wrought up on the umpteenth version than on the first.

This is very odd. How can it happen?

One answer is simple: What you’re feeling in a repeat viewing, or a viewing of dramatized historical events, isn’t suspense at all. Robert Yanal has explained this position here. He suggests that you’re responding to other aspects of the story. Maybe in rewatching Notorious you’re enjoying the unfolding romance, and you attribute your interest to suspense. And there are feelings akin to suspense that don’t rely on uncertainty–dread, for instance, in facing likely doom. (This is my example, not Yanal’s, but I think it’s plausible.) Another possibility Yanal floats is that on repeat viewings, you have actually forgotten what happens next, or how the story ends.

Yanal’s account doesn’t fully satisfy me, largely because I think that most people know what suspense feels like and attest to feeling it on repeat viewings. I did feel some dread in watching United 93, but I think that was mixed with a genuine feeling of suspense–a momentary, if illogical uncertainty about the future course of events. In any case, I didn’t forget what happened at the end; I expected it in quite a self-conscious way.

Yanal’s account doesn’t fully satisfy me, largely because I think that most people know what suspense feels like and attest to feeling it on repeat viewings. I did feel some dread in watching United 93, but I think that was mixed with a genuine feeling of suspense–a momentary, if illogical uncertainty about the future course of events. In any case, I didn’t forget what happened at the end; I expected it in quite a self-conscious way.

Richard Gerrig, the psychologist who gave anomalous suspense its name, offers a different solution. He posits that in general, when we reread a novel or rewatch a film, our cognitive system doesn’t apply its prior knowledge of what will happen. Why? Because our minds evolved to deal with the real world, and there you never know exactly what will happen next. Every situation is unique, and no course of events is literally identical to an earlier one. “Our moment-by-moment processes evolved in response to the brute fact of nonrepetition” (Experiencing Narrative Worlds, 171). Somehow, this assumption that every act is unique became our default for understanding events, even fictional ones we’ve encountered before.

I think that Gerrig leaves this account somewhat vague, and its conception of a “unique” event has been criticized by Yanal, in the article above. But I think that Gerrig’s invocation of our evolutionary history is relevant, for reasons I’ll mention shortly.

Suspense as morality, probability, and imagination

The most influential current theory of suspense in narrative is put forth by Noël Carroll. The original statement of it can be found in “Toward a Theory of Film Suspense” in his book Theorizing the Moving Image. Carroll proposes that suspense depends on our forming tacit questions about the story as it unfolds. Among other things, we ask how plausible certain outcomes are and how morally worthy they are. For Carroll, the reader or viewer feels suspense as a result of estimating, more or less intuitively, that the situation presents a morally undesirable outcome that is strongly probable.

When the plot indicates that an evil character will probably fail to achieve his or her end, there isn’t much suspense. Likewise, when a good character is likely to succeed, there isn’t much suspense. But we do feel suspense when it seems that an evil character is likely to succeed, or that a good character is likely to fail. Given the premises of the situation, the likelihood is very great that Alicia and Devlin will be caught by Sebastian and the Nazis, so we feel suspense.

What of anomalous suspense? Carroll would seem to have a problem here. If we know the outcome of a situation because we’ve seen the movie before, wouldn’t our assessments of probability shift? On the second viewing of Notorious, we can confidently say that Alicia and Devlin’s stratagems have a 100% chance of success. So then we ought not to feel any suspense.

Carroll’s answer is that we can feel emotions in response to thoughts as well as beliefs. Standing at a viewing station on a mountaintop, safe behind the railing, I can look down and feel fear. I don’t really believe I’ll fall. If I did, I would back away fast. I imagine I’m going to fall; perhaps I even picture myself plunging into the void and, a la Björk, slamming against the rocks at the bottom. Just the thought of it makes my palms clammy on the rail.

Carroll points out that imagining things can arouse intense emotions, and his book The Philosophy of Horror uses this point to explain the appeal of horrific fictions. The same thing goes, more or less, for suspense. If the uncertainty at the root of suspense involves beliefs, then there ought to be a problem with repeat viewings. But if you merely entertain the thought that the story situation is uncertain, then you can feel suspense just as easily as if you entertained the thought that you were falling off the mountain top.

In other words, the relation between morality and probability in a suspenseful situation is offered not to your beliefs but to your imagination. When you judge that in this story the good is unlikely to be rewarded, you react appropriately–regardless of what you know or believe about what happens next. Carroll outlines this view in his book Beyond Aesthetics.

How are we encouraged to entertain such thoughts in our imagination? Carroll indicates that the film or piece of literature needs to focus our attention on the suspenseful factors at work, thus guiding us to the appropriate thoughts about the situation. There might, though, be more than attention at work here.

The firewall

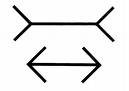

In Consciousness and the Computational Mind (1987), psychologist Ray Jackendoff asked why music doesn’t wear out. When composers write tricky chord progressions or players execute startling rhythmic changes, why do those surprise or thrill us on rehearing? Similarly, you’ve seen the Müller-Lyer optical illusion many times, and you know that the two horizontal lines are of equal length. You can measure them.

Yet your eyes tell you that the lines are of different lengths and no knowledge can make you see them any other way. This illusion, in Jerry Fodor‘s phrase, is cognitively impenetrable.

We can reexperience familiar music or fall prey to optical illusions because, in essence, our lower-level perceptual activities are modular. They are fast and split up into many parallel processes working at once. They’re also fairly dumb, quite impervious to knowledge. Jackendoff suggests that our musical perception, like our faculties for language and vision, relies on

a number of autonomous units, each working in its own limited domain, with limited access to memory. For under this conception, expectation, suspense, satisfaction, and surprise can occur within the processor: in effect, the processor is always hearing the piece for the first time (245).

The modularity of “early vision”–the earliest stages of visual processing–is exhaustively discussed by Zenon W. Pylyshyn in Seeing and Visualizing: It’s Not What You Think (2006).

As students of cinema, we’re familiar with the fact that vision can be cognitively impenetrable. We know that movies consist of single frames, but we can’t see them in projection; we see a moving image.

Early vision works fast and under very basic, hard-wired assumptions about how the world is. That’s because our visual system evolved to detect regularities in a certain kind of environment. That environment didn’t include movies or cunningly designed optical illusions. So there might be a kind of firewall between parts of our perception and our knowledge or memory about the real world.

Daniel J. Levitin’s lively book, This is Your Brain on Music summarizes the neurological evidence for this firewall in our auditory system. When we listen to music, a great deal happens at very low levels. Meter, pitch, timbre, attack, and loudness are detected, dissected, and reconstructed across many brain areas. The processes runs fast, in parallel, and we have very little voluntary control of them, let alone awareness of them. Of course higher-level processes, like knowledge about the piece, the composer, or the performer, feed into the whole activity. But that’s inevitably running on top of the very fast uptake, disassembly, and reassembly of sensory information. Go here for more information on the book, including some music videos.

Daniel J. Levitin’s lively book, This is Your Brain on Music summarizes the neurological evidence for this firewall in our auditory system. When we listen to music, a great deal happens at very low levels. Meter, pitch, timbre, attack, and loudness are detected, dissected, and reconstructed across many brain areas. The processes runs fast, in parallel, and we have very little voluntary control of them, let alone awareness of them. Of course higher-level processes, like knowledge about the piece, the composer, or the performer, feed into the whole activity. But that’s inevitably running on top of the very fast uptake, disassembly, and reassembly of sensory information. Go here for more information on the book, including some music videos.

So here’s my hunch: A great deal of what contributes to suspense in films derives from low-level, modular processes. They are cognitively impenetrable, and that creates a firewall between them and what we remember from previous viewings.

A suspense film often contains several very gross cues to our perceptual uptake. We get tension-filled music and ominous sound effects, such as low-bass throbbing. We get rapid cutting and swift camera movements. Often the shots are close-ups, as in Notorious‘s wine-cellar scene and during the characters’ final descent of the staircase. Close-ups concentrate our vision on one salient item, creating the attentional focus Carroll emphasizes. The shots are often cut together so fast that we barely have time to register the information in each one.

This isn’t to say that the action itself has to be fast. The action in the Hitchcock scenes isn’t rapid, but its stylistic treatment is. In typical suspense scenes, our “early vision” and “early audition,” biased toward quick pickup, are given rapid-fire bursts of information while our slower, deliberative processes are put on hold. This is happening in the Birth of a Nation assassination scene, as well as in the frantic second half of United 93.

Further, what is shown can push our processing as well. Seeing people’s facial expressions touches off empathy and emotional contagion, perhaps through mirror neurons.

This tendency may explain why we can, momentarily, feel a wisp of empathy for unsympathetic characters. When their expressions show fear, we detect and resonate to that even if we aren’t rooting for them to succeed.

We may also be responding to some very basic scenarios for suspenseful action. Imagine dangling at a great height; “hanging” is the root of the word suspense. Or imagine hurtling toward an obstruction, or being stalked by an animal, or being advanced upon by a looming figure. As prototypes of impending danger, these events may in themselves trigger a minimal feeling of suspense. And such situations are part of filmic storytelling from its earliest years.

Maybe we’re predisposed to find facial expressions and dangerous situations salient because of our evolutionary history, or maybe they’re learned from a very young age. Either way, such responses don’t require much deliberate thinking. They just trigger rapid responses that we can reflect upon later.

Stylistic emphasis and prototype situations surely help the attention-focusing that Carroll discusses. But I’m suggesting something stronger: Many of these cues don’t merely guide our attention to the critical suspense-creating factors in the scene. These cues are arresting and arousing in themselves. They trigger responses that, in the right narrative situation, can generate suspense, regardless of whether we’ve seen the movie before.

Beyond these cues, of course we have to understand the story to some degree. Probably some of the aspects of storytelling that Carroll, Gerrig, and others (including me) have highlighted come into play. As Hitchcock famously pointed out, suspense sometimes depends on telling the viewer more than the character knows. We have to see the bomb under the table that the character doesn’t know about. Suspense is also conjured up by Carroll’s ratio of morality to probability, our real-world understanding of deadlines, and other higher-order aspects of comprehension. In addition, our knowledge of how stories are typically told probably shapes our uptake. We expect suspense to be a part of a film, and so we’re alert for cues that facilitate it.

Involuntary suspense

So I’m hypothesizing that part of the suspense we feel in rewatching a film depends on fast, mandatory, data-driven pickup. That activity responds to the salient information without regard to what we already know.

According to this argument, the sight of Eve Kendall dangling from Mount Rushmore will elicit some degree of suspense no matter how many times you’ve seen North by Northwest, and that feeling will be amplified by the cutting, the close-ups, the music, and so on. Your sensory system can’t help but respond, just as it can’t help seeing equal-length lines in the pictorial illusion. For some part of you, every viewing of a movie is the first viewing.

This tendency may hold good for other emotions than suspense. In the psychological jargon I adopted in Narration in the Fiction Film, experiencing a narrative is likely to be both a bottom-up process and a top-down process. Suspense and other emotional effects in film may depend not only on conceptual judgments about uncertainty, likelihood, and so on. They may also depend on quick and dirty processes of perception that don’t have much access to memory or deliberative thinking.

Film works on our embodied minds, and the “embodied” part includes a wondrous number of fast, involuntary brain activities. This process gives filmmakers enormous power, along with enormous responsibilities.

PS: 9 March. Jason Mittell writes a comment, based on his recent research on TV fans’ attitudes toward spoilers, at his site here. More later, I hope, when I have a chance to assimilate his argument.