Archive for the 'Film theory' Category

Do filmmakers deserve the last word?

DB here:

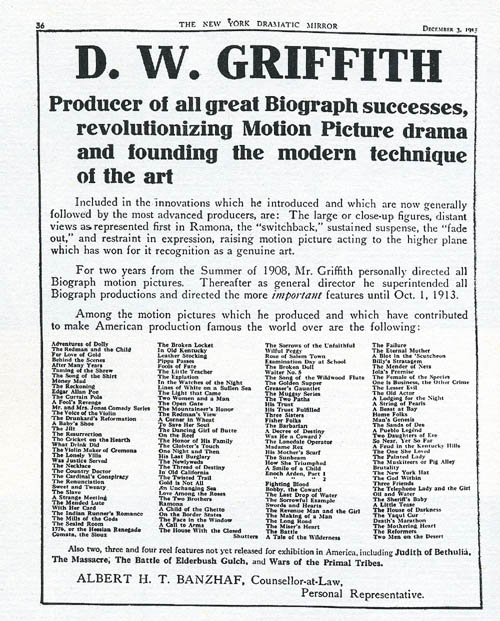

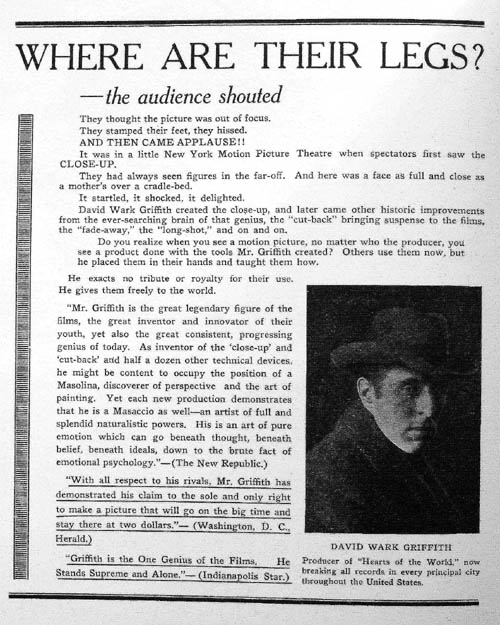

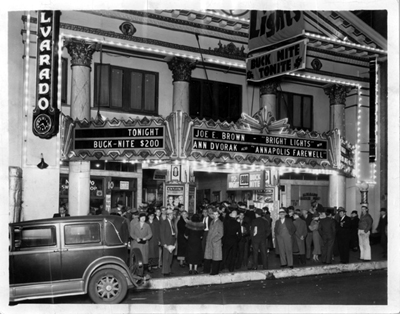

On 3 December 1913, the above advertisement appeared in the New York Dramatic Mirror. D. W. Griffith had left the American Biograph company and set out on an independent path that would lead to The Birth of a Nation and beyond. Because Biograph never credited directors, casts, or crews, he wanted to make sure that the professional community was aware of his contributions. Not only did he point out that he had made several of the most noteworthy Biograph films; he also took credit for new techniques. He introduced, he claims, the close-up, sustained suspense, restrained acting, “distant views” (presumably picturesque long-shots of the action), and the “switchback,” his term for crosscutting—that editing tactic that alternates shots of different actions occurring at the same time.

Griffith’s bid for credit was a shrewd move for his career, and it had repercussions after the stunning success of The Birth of a Nation two years later. Many historians took Griffith at his word and credited him with the breakthroughs he listed. He became known as the father of “film grammar” or “film language.” The idea hung on for decades. Here’s the normally perceptive Dwight Macdonald, criticizing Dreyer’s Gertrud for being anachronistic:

He just sets up his camera and photographs people talking to each other, usually sitting down, just the way it used to be done before Griffith made a few technical innovations. (1)

Filmmakers believed the Griffith story too. Orson Welles wrote of the “founding father” in 1960:

Every filmmaker who has followed him has done just that: followed him. He made the first close-up and moved the first camera. (2)

In the late 1970s a new generation of early-cinema scholars gave us a more nuanced account of Griffith’s place in history. They pointed out that most of the innovations he claimed either predated his Biograph work, (3) or appeared simultaneously and independently in Europe and in other American films. Some Griffith partisans had already conceded this, but they maintained that he was the great synthesizer of these devices, and that he used them with a vigor and vividness that surpassed the sources.

That judgment seems right in part, but Eileen Bowser, Tom Gunning, Barry Salt, Kristin Thompson, Joyce Jesniowski, and other early-cinema researchers have drawn a more complicated picture. (4) Griffith did speed up cutting and devote an unusual number of shots to characters entering and leaving locales. But these innovations weren’t usually recognized as original by previous historians. More interestingly, much of what Griffith did was not taken up by his successors. His technique was idiosyncratic in many respects. By 1915 younger directors like Walsh, Dwan, and DeMille were forging a smoother style that would be more characteristic of mainstream storytelling cinema than Griffith’s somewhat eccentric scene breakdowns. Instead of creating film language, he spoke a forceful but often unique dialect.

The New York Dramatic Mirror ad coaxes me to reflect on how filmmakers have shaped critics’ and historians’ responses to their work. Hawks and Hitchcock developed a repertory of ideas, opinions, and anecdotes to be trotted out on any occasion. Today, directors write books, give interviews, appear on infotainment shows, and provide DVD commentary. We know that many of the talking points are planned as part of the film’s publicity campaign, and journalists dutifully follow the lead. (In Chapter 4 of The Frodo Franchise, Kristin discusses how this happened with Lord of the Rings.) For many decades, in short, filmmakers have been steering critics and viewers toward certain ways of understanding their films. How much should we be bound by the way the filmmaker positions the film?

Deep focus and deep analysis

Citizen Kane (1941).

Determining intentions is tricky, of course. Still, I think that in many cases we can reconstruct a plausible sense of an artist’s purposes on the basis of the artwork, the historical context, surviving evidence, and other information. (5) This may or may not correspond to what the artist says on a particular occasion. For now, I want simply to point to one instance in which filmmakers have shaped critical uptake, with results that are both illuminating and limiting.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, André Bazin, one of the great theorists and critics of cinema, argued that Orson Welles and William Wyler created a sort of revolution in filmmaking. They staged a shot’s action in several planes, some quite close to the camera, and maintained more or less sharp focus in all of them. Bazin claimed that Welles’ Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons and Wyler’s The Little Foxes and The Best Years of Our Lives constituted “a dialectical step forward in film language.”

Their “deep-focus” style, he claimed, produced a more profound realism than had been seen before because they respected the integrity of physical space and time. According to Bazin, traditional cutting breaks the world into bits, a series of close-ups and long shots. But Welles and Wyler give us the world as a seamless whole. The scene unfolds in all its actual duration and depth. Moreover, their style captured the way we see the world; given deep compositions, we must choose what to look at, foreground or background, just as we must choose in reality. Bazin wrote of Wyler:

Thanks to depth of field, at times augmented by action taking place simultaneously on several plane, the viewer is at least given the opportunity in the end to edit the scene himself, to select the aspects of it to which he will attend. (6)

While granting differences between the directors, Bazin said much the same about Welles, whose depth of field “forces the spectator to participate in the meaning of the film by distinguishing the implicit relations” and creates “a psychological realism which brings the spectator back to the real conditions of perception” (7).

In addition, Bazin pointed out, this sort of composition was artistically efficient. The deep shot could supply both a close-up and a long-shot in the same framing—a synthesis of what traditional editing had given in separate shots. Bazin wove all these ideas into a larger theory that cinema was inherently a realistic medium, bound to photographic recording, and Welles and Wyler had discovered one path to artistic expression without violating the medium’s biases.

There are many objections to Bazin’s argument, some of which I’ve rehearsed in On the History of Film Style. My point here is that Bazin was presenting analytical points that stemmed from publicity put out by Welles, Wyler, and especially their talented cinematographer Gregg Toland.

In a 1941 article in American Cinematographer, Toland talked freely about how he sought “realism” in Citizen Kane. The audience must feel it is “looking at reality, rather than merely a movie.” Key to this was avoiding cuts by means of long takes and great depth of field, combining “what would conventionally be made as two separate shots—a close-up and an insert—into a single, non-dollying shot.”(8) Toland defended his sometimes extreme stylistic experimentation on grounds of realism and production efficiency, criteria that carried some weight in his professional community of cinematographers and technicians. (9)

Toland’s campaign for his style addressed the general public too. For Popular Photography he wrote an article (10) explaining again that his “pan-focus” technique captured the conditions of real-life vision, in which everything appears in sharp focus. A still broader audience encountered a Life feature in the same year (11), explaining Toland’s approach with specially-made illustrations. Two samples show selective focus, one focused on the background, the other on the foreground.

An accompanying photo shows pan-focus at work, with Toland in frame center, an actor in the background, and Toland’s camera assistant in the foreground.

In sum, Toland’s publicity prepared viewers, both professional and nonprofessional, for an odd-looking movie.

Throughout the 1940s, Welles and Wyler wrote and gave more interviews, often insisting that their films invited greater participation on the part of spectators. In a crucial 1947 statement, Wyler noted:

Gregg Toland’s remarkable facility for handling background and foreground action has enabled me over a period of six pictures he has photographed to develop a better technique for staging my scenes. For example, I can have action and reaction in the same shot, without having to cut back and forth from individual cuts of the characters. This makes for smooth continuity, an almost effortless flow of the scene, for much more interesting composition in each shot, and lets the spectator look from one to the other character at his own will, do his own cutting. (12)

Some of this publicity material made its way into French translation after the liberation of Paris, just as Kane, The Little Foxes, and other films were arriving too. Bazin and his contemporaries picked up the claims that these films broke the rules. Deep-focus cinematography became, in the hands of critics, a revolutionary new technique. They presented it as their discovery, not something laid out in the films’ publicity.

But the case involved, as Huck Finn might say, some stretchers. Watching the baroque and expressionist Kane, it’s hard to square it with normal notions of realism, and we may suspect Toland of special pleading. Some of Toland’s purported innovations, such as low-angle shots showing ceilings, had been seen before. Even the signature Toland look, with cramped, deep compositions shot from below, can be found across the history of cinema before Kane. Here is a shot from the 1939 Russian film, The Great Citizen, Part 2 by Friedrich Ermler.

More seriously, some of Toland’s accounts of Kane swerve close to deception. For decades people presupposed that dazzling shots like these were made with wide-angle lenses.

Yet the deep focus in the first image was accomplished by means of a back-projected film showing the boy Kane in the window, while the second image is a multiple exposure. The glass and medicine bottle were shot separately against a black background, then the film was wound back and the action in the middle ground and background were shot. (And even the middle-ground material, Susan in bed, is notably out of focus.) I suspect that the flashy deep-focus illustration in Life, shot with a still camera, is a multiple exposure too. In any event, much of the depth of field on display in Kane couldn’t have been achieved by straight photography. (13)

RKO’s special-effects department had years of experience with back projection and optical printing, notably in the handling of the leopard in Bringing Up Baby, so many of Kane‘s boldest depth shots were assigned to them. But here is all that Toland has to say on the subject:

RKO special-effects expert Vernon Walker, ASC, and his staff handled their part of the production—a by no means inconsiderable assignment—with ability and fine understanding. (14)

Kane’s reliance on rephotography deals a blow to Bazin’s commitment to film as a medium committed to recording an event in front the camera. Instead, the film becomes an ancestor of the sort of extreme artificiality we now associate with computer-generated imagery.

Despite these difficulties, Toland’s ideas sensitized filmmakers and critics to deep space as an expressive cinematic device. Modified forms of the deep-focus style became a major creative tradition in black-and-white cinema, lasting well into the 1960s. Bazin’s analysis certainly developed Toland’s ideas in original directions, and he creatively assimilated what Toland and his directors said into an illuminating general account of the history of film style. None of these creators and critics were probably aware of the remarkable depth apparent in pre-1920 cinema, or in Japanese and Soviet film of the 1930s. Their claims taught us to notice depth, even though we could then go on to discover examples that undercut Toland’s claims to originality.

Some little things to grasp at

I assume that Toland and his directors were sincerely trying to experiment, however much they may have packaged their efforts to appeal to viewers’ and critics’ tastes. But sometimes artists aren’t so sincere. By the 1950s, we have directors who started out as film critics, and they realized that they could guide the agenda. Here is Claude Chabrol:

I need a degree of critical support for my films to succeed: without that they can fall flat on their faces. So, what do you have to do? You have to help the critics over their notices, right? So, I give them a hand. “Try with Eliot and see if you find me there.” Or “How do you fancy Racine?” I give them some little things to grasp at. In Le Boucher I stuck Balzac there in the middle, and they threw themselves on it like poverty upon the world. It’s not good to leave them staring at a blank sheet of paper, no knowing how to begin. . . . “This film is definitely Balzacian,” and there you are; after that they can go on to say whatever they want. (15)

Chabrol is unusually cynical, but surely some filmmakers are strategic in this way. I’d guess that a good number of independent directors pick up on currents in the culture and more or less self-consciously link those to their film.

Today, in press junkets directors can feed the same talking points to reporters over and over again. An example I discuss in the forthcoming Poetics of Cinema is the way that Chaos theory has been invoked to give weight to films centering on networks and fortuitous connections. As I read interview after interview, I thought I’d scream if I encountered one more reference to a butterfly flapping its wings.

More recently, Paul Greengrass gave critics some help when he suggested that the jumpy cutting and spasmodic handheld camera of The Bourne Ultimatum suggested the protagonist’s subjective point of view–presumably, Jason’s psychological disorientation and frantic scanning of his surroundings. I expressed skepticism about this on an earlier blog entry, Anne Thompson replied on her blog, and I returned to the subject again. Any director’s statement of purpose is interesting in itself, but it should be assessed in relation to the evidence we detect onscreen.

Another recent instance: the new Taschen book on Michael Mann. The luscious pictures, mainly from Mann’s archive, are the volume’s raison d’etre, but the filmmaker seems to have placed unusual demands on the text. F. X. Feeney writes:

An earlier version of this book completed by another writer attempted (in a spirit of sincere praise) to treat Mann’s films as reactions against film traditions, as subversions of genre. This fetched a rebuke from Mann: “It’s irrelevant and neither accurate nor authentic to compare my films to other films because they don’t proceed from genre conventions and then deviate from those conventions. They proceed from life. For better or worse, what I’ve seen and heard and learned on my own is the origin of this material. Maybe the film medium by nature spawns conventions, because we all built on what’s gone before, but the content and themes of my films are not facile and derivative. They are drawn from life experience.” (16)

We have to wonder if Mann’s objection played a role in eliminating the earlier writer’s version. If that happened, it’s an unusually strong instance of a director’s holding sway over critical commentary. (17)

In the text we have, Feeney provides a chronological account of Mann’s career: plot synopses, thematic commentary, production background. There’s no discussion of broader historical trends, such as the migration of TV directors into film, the creative options available in 1980s-1990s Hollywood, the development of self-conscious pictorialism in modern film, the possibility of genre films becoming art-films or prestige pictures, or the changes in media culture or American society. All of these lines of inquiry would require comparing Mann with other filmmakers. It remains for other writers, perhaps without the director’s cooperation, to put Mann’s achievement into such contexts.

It’s always vital to listen to filmmakers, but we shouldn’t limit our analysis to what they highlight. We can detect things that they didn’t deliberately put into their films, and we can sometimes find traces of things they don’t know they know. For example, virtually no director has explained in detail his or her preferred mechanics for staging a scene, indicating choices about blocking, entrances and exits, actors’ business, and the like. Such craft skills are presumably so intuitive that they aren’t easy to spell out. Often we must reconstruct the director’s intuitive purposes from the regularities of what we find onscreen. (For examples, see this site here, here, and here.) And it doesn’t hurt, especially in this age of hype, to be a little skeptical and pursue what we think is interesting, whether or not a director has flagged it as worth noticing.

(1) Macdonald, “Gertrud,” Esquire (December 1965), 86.

(2) Quoted in Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, ed. Jonathan Rosenbaum, This is Orson Welles (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 21).

(3) Such would seem to be the case of the close-up, which of course is found very early in film history. But Griffith’s idea of a close-up may not correspond to ours. More on this in a later blog, perhaps.

(4) I give an overview of this rich body of research in Chapter 5 of On the History of Film Style. See also various entries in the Encyclopedia of Early Cinema, ed. Richard Abel (New York: Routledge, 2005).

(5) The most detailed argument for this view I know is Paisley Livingston’s book Art and Intention: A Philosophical Study.

(6) “William Wyler, or the Jansenist of Directing,” in Bazin at Work: Major Essays and Reviews from the Forties and Fifties, ed. Bert Cardullo (New York: Routledge, 1997), 8.

(7) Orson Welles: A Critical View, trans. Jonathan Rosenbaum (New York: Harper and Row, 1978) 80).

(8) Toland, “Realism for Citizen Kane,” American Cinematographer 22, 2 (February 1941), 54, 80.

(9) See the discussion in Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), 345-349.

(10) Toland, “How I Broke the Rules in Citizen Kane,” Popular Photography (June 1941), 55, 90-91.

(11) “Orson Welles: Once a Child Prodigy, He Has Never Quite Grown Up,” Life (May 26, 1941), 110-111.

(12) Wyler, “No Magic Wand,” The Screen Writer (February 1947), 10.

(13) Peter Bogdanovich was to my knowledge the first person to publish some of this information; see “The Kane Mutiny,” Esquire 77, 4 (October 1972), 99-105, 180-90.

(14) Toland, “Realism,” 80.

(15) “Chabrol Talks to Rui Noguera and Nicoletta Zalaffi,” Sight and Sound 40, 1 (Winter 1970-1971), 6.

(16) F. X. Feeney, Michael Mann (Cologne: Taschen, 2006), 21.

(17) Mann’s reasoning puzzles me. He insists that his films can’t be compared to others along any dimensions, especially thematic ones. Yet in saying that his films are lifelike, he suggests that other films aren’t as realistic as his. Moreover, what about comparisons on grounds of technique, surely one of the most striking and admired features of Mann’s work? For reasons that are obscure, the director discourages any critical consideration of style; Feeney tells us that Mann hates the very word (p. 20).

Ad in Wid’s Year Book 1918.

PS: 15 October: I’ve received a clarification from Paul Duncan, editor of F. X. Feeney’s Michael Mann book for Taschen. He expresses general agreement with my suggestions about how directors shape the uptake of their work, but he explains that the Mann book isn’t an instance of it. Here are the comments bearing on my blog entry.

In reply to my suggestion of other avenues to explore about Mann’s career:

In fairness to F.X. Feeney, he only had 25,000 words to cover Mann’s career, and all the subjects you write about are really outside the scope of the book. It sounds as though these are subjects that you would like to explore, and I can’t wait to read them in a future book or blog.

As for whether Mann exercised some control over the book’s final form, which I float as one possible explanation for its compass:

First, you speculate whether Mann caused the first version of the book to be scrapped, i.e. He exerted editorial control/censorship over the book. This is not the case, and if it was, do you think that he would have allowed F.X. to write that in the published version of the book?

In Note 17 appended to Feeney’s quote, you write: “Yet in saying that his films are lifelike, he suggests that other films aren’t as realistic as his.” If you had continued Mann’s quote, you would have reported the following: “I don’t look at the excellent French director Jean-Pierre Melville to decide how to tell the story in Thief. I meet thieves. And I guarantee you the reason Melville’s Le Samourai 1967) has authenticity, the reason Raoul Walsh’s White Heat (1949) has authenticity, is because those film-makers knew thieves, too.” I do not see any evidence here that Mann suggests that his films are more lifelike than other directors’. Only that his films stem from life like other films stem from life.

Also, in Note 17, you write: “For reasons that are obscure, the director discourages any critical consideration of style; Feeney tells us that Mann hates the very word (p. 20).” The reason Mann hates the word “style”—and I apologize for not making this clear in the book—is because after producing the Miami Vice TV show, he was forever referred to as a stylist, and the “style” of the show was all anybody ever talked about. The implication was that Mann is a director of style without substance. Subsequently, Mann has been very wary of the word, and discussion of it, because it puts undue weight on one aspect of his work.

Finally, I would like to explain a little of the working method with Mann on the book. The book was researched and written during rehearsal, filming and editing of Collateral. F.X. wrote the text and was given full access to everything that Mann had said in interviews. Mann then read and annotated the text, and this was discussed face-to-face with F.X. Most of these annotations were of a factual nature, correcting dates, being precise about the sequence of events, and to correct misinterpretations of his comments in previous interviews. However, they would also bring up new comments from Mann about his work. F.X. then rewrote some texts to include Mann’s comments, and then F.X. wrote his replies. In this way, the book became more of a dialogue between Mann and F.X. and is stronger for it I feel. So, in this case, the filmmaker did not get the last word.

I thank Paul for his clarifications, which should be of interest to all the book’s readers. On only two matters do we disagree.

First, Feeney’s book achieves what it set out to achieve, and it deserves credit for giving us valuable information about Mann in a clear, pungent style. And no one expects a Taschen book to be an in-depth monograph covering all aspects of a director’s career. But I still think that length limits don’t prevent an author from raising the contextual issues I mention. Many articles manage to address matters that go beyond the sort of career survey that Feeney provides, so there are ways to sketch such issues in an abbreviated way. I inferred, erroneously, that the choice not to tackle them could have been related to Mann’s own views on the comparative dimension that such issues tend to rely on.

Secondly, a minor matter: The fact that Mann can invoke Melville and Walsh on films about thieves suggests that a comparative perspective is valuable; he’s including himself in the company of directors who know their subjects from life, in explicit contrast to those who don’t. I didn’t include the extra sentences because I thought that they simply provided further signs of the contradiction I found in Mann’s own position—that his films can’t be compared to other directors’ works.

Bergman, Antonioni, and the stubborn stylists

DB here:

Jonathan Rosenbaum has created quite a stir. His New York Times Op-Ed piece, “Scenes from an Overrated Career,” offers a fairly harsh judgment on the films of Ingmar Bergman. In one sense the timing was awkward; the poor man had just died. But the article wouldn’t have attracted much attention if Rosenbaum had waited a few months, so if creating a cause célèbre was his goal, he chose the right moment.

Timing aside, there wasn’t much in the piece that hasn’t been said by certain cadres of cinephiles for decades. Back in the 1960s, people called Bergman “theatrical,” “uncinematic,” pretentious, and intellectually shallow. He was even accused of hypocrisy. His spiritual, philosophical films always seemed to depend on a surprising number of couplings, killings, rapes, and gorgeous ladies, often naked. Rosenbaum contrasts Bergman with Bresson and Dreyer, more austere religious filmmakers as well as great formal innovators, and this gambit too is familiar from late-night film-society disputes. Jonathan’s case is news in the good, grey Times, but it’s an old story among his (my) generation.

I think that this generational antipathy has many sources. While Bergman had considerable academic cachet, this may have hurt him with smart-alecks like us. Cinephile priests and professors told us that Bergman was a great mind, but we suspected them of snobbery, for they often disdained even foreign filmmakers who dabbled in popular genres. Kurosawa was admired for Rashomon and I Live in Fear rather than for Seven Samurai and Yojimbo. And many of Bergman’s intellectual fans despised the classic tradition of American studio film. Hitchcock had not yet convinced literature profs of his excellence, and Ford was a gnarled geezer who made Westerns. Bergman and his acolytes seemed just too square. Our money was on Godard, especially after Susan Sontag’s magisterial essay on him.

Furthermore, some critics were on our side. Pauline Kael, with her nose for elitism, mocked ambitious European experiments like Marienbad. Andrew Sarris, who had a huge influence on our generation, initially registered respect for the arthouse kings. They proved that an artist could put a personal vision on film, thus buttressing the auteur approach to criticism. But Sarris retreated fairly fast. He was more unflaggingly enthusiastic about American popular cinema, and by contrast he often characterized the new Europeans as gloomy, middlebrow, and narcissistic. (He did, after all, coin the phrase “Antonionennui.”) Sarris made it possible for us to argue that, say, Meet Me in St. Louis was a better film than L’Eclisse or Winter Light. (1)

Of course I’m generalizing; no Boomer’s experience was identical with any other’s. Speaking just for myself, I didn’t have a deep love for Bergman, and I still don’t. I was drawn to his early idylls (Monika, Summer Interlude) and impressed but chilled by the official classics (Smiles of a Summer Night, The Seventh Seal, The Virgin Spring). Persona, I admit, was a punch in the face. Seeing it in its New York opening, I felt that all of modern cinema was condensed into a mere eighty minutes. But no Bergman film afterward measured up to that for me, and after The Serpent’s Egg I just lost interest, catching up with Cries and Whispers, Scenes from a Marriage, Fanny and Alexander, and a very few others over the later decades.

We can talk tastes forever. Maybe you think Bergman is great, or the greatest, or obscenely overrated. I think that there’s something more general and intriguing going on beyond our tastes. What makes this hard to see is that the venues of popular journalism don’t allow us to explore some of the ideas and questions raised by our value judgments.

Critical semaphore

Take some of Rosenbaum’s criticisms, which Roger Ebert has persuasively answered. I’d add that Jonathan is sometimes applying criteria to Bergman that he wouldn’t apply to directors he admires. Bergman isn’t taught frequently in film courses? So what? Neither is Straub/Huillet or Rivette or Bela Tarr. Bergman is theatrical? So too are Rivette and Dreyer, both of whom Rosenbaum has written about sympathetically.

More importantly, Jonathan’s critique is so glancing and elliptical that we can scarcely judge it as right or wrong. A few instances:

*Bergman’s movies aren’t “filmic expressions.” There’s no opportunity in an Op-Ed piece for Jonathan to explain what his conception of filmic expression is. Is he reviving the old idea of cinematic specificity—a kind of essence of cinema that good movies manifest? As opposed to theatrical cinema? I’ve argued elsewhere on this site that we should probably be pluralistic about all the possibilities of the medium.

*Bergman was reluctant to challenge “conventional film-going habits.” Why is that bad? Why is challenging them good? No time to explain, must move on….

*Bergman didn’t follow Dreyer in experimenting with space, or Bresson in experimenting with performance. Not more than .0001 % of Times readers have the faintest idea what Jonathan is talking about here. He would need to explain what he takes to be Dreyer’s experiments with space and Bresson’s experiments with performance.

In his reply to Roger Ebert, Jonathan has kindly referenced a book of mine, where I make the case that Dreyer experimented with cinematic space (and time). Right: I wrote a book. It takes a book to make such a case. It would take a book to explain and back up in an intellectually satisfying way the charges that Jonathan makes.

Popular journalism doesn’t allow you to cite sources, counterpose arguments, develop subtle cases. No time! No space! No room for specialized explanations that might mystify ordinary readers! So when the critic proposes a controversial idea, he has to be brief, blunt, and absolute. If pressed, and still under the pressure of time and column inches, he will wave us toward other writers, appeal to intuition and authority, say that a broadside is really just aimed to get us thinking and talking. But what have we gained by sprays of soundbites? Provocations are always welcome, but if they really aim to change our thinking, somebody has to work them through.

I’ve suggested elsewhere that too much film writing, on paper and on the Net, favors opinion over information and ideas. Opinions, which can be stated in a clever turn of phrase, suit the constraints of publication. Amassing facts and exploring ideas in a responsible way—making distinctions, checking counterexamples, anticipating objections, nuancing broad statements—takes more time. Academics are sometimes mocked for their show-all-your-work tendencies, and I grant that this can be tedious. But we’re just trying to get it right, and that can’t be done quickly.

Now you know why our blog entries are so damn long.

This one is no exception.

Too often film talk slides from being film comment to film chat to film chatter. Even our best critics, among whom Rosenbaum must be counted, make use of a kind of rapid semaphore, signaling to the already converted. Evidently his ideal reader agrees that good cinema is challenging and experimental, directing actresses is a minor talent, and being admired by upscale Manhattanites is a sign of a sellout. Readers will self-select; those who have congruent tastes will pick up the signals. But these beliefs aren’t really knowledge. They’re just, when you get right down to it, attitudes.

I’ll try to explore just one of the issues Jonathan raises but can’t pursue: the question of how stylistically innovative Bergman was. Of course, I can’t write a book here either. I offer what follows as simply the start of what could be an interesting research project.

One stylistic arc

The rise of European arthouse auteurs in film culture of the 1950s and 1960s put the question of personal style on the agenda, but back then we didn’t have many tools for analyzing stylistic differences among directors. We didn’t know much about the local histories of those imported films; as Sarris recently pointed out, L’Avventura was Antonioni’s sixth feature but was his first film released in the US. Moreover, we didn’t know much about the norms of ordinary commercial filmmaking, in the US or elsewhere. (2) Today we’re in a better position to characterize what went on. (3)

In most countries, quality cinema of the late 1940s relied on variations of the Hollywood approach to staging, shooting, and cutting that had emerged in the silent era. Directors moved their performers around the set fairly fluidly and used editing to enlarge and stress aspects of the action. You can see a straightforward example of this approach on an earlier entry on this blogsite.

Many directors of the period built upon this default by creating deep space in staging and framing. Using wide-angle lenses, directors could allow actors to come quite close to the camera, sometimes with their heads looming in the foreground, while other figures could be placed far in the distance. Several planes of action could be more or less in focus. Here’s a straightforward example from William Wyler’s The Little Foxes.

We find directors exploiting this approach not only in the United States but in Eastern and Western Europe, Scandinavia, the Soviet Union, Japan, Mexico, and South America. Here’s an instance from the French film Justice est faite (1950).

Why did this approach emerge in so many countries at the same time? We don’t really know. It wasn’t simply the influence of Citizen Kane, as we might think. The Stalinist cinema had developed deep-space shooting in the 1930s, and we can find it elsewhere. Probably Hollywood’s 1940s films helped spread the style, but there are likely to be local causes in various countries too.

In any event, during the 1950s two technological changes posed problems for this style. One was the greater use of color filming, which renders depth of field much more difficult. The other innovation was anamorphic widescreen, a technology seen in CinemaScope and Panavision. These systems also had trouble maintaining focus in many planes when the foreground was close to the camera. The flagrant depth compositions we find in black-and-white ‘flat’ films were quite difficult to replicate in color and anamorphic widescreen.

Through the 1960s, the deep-focus style became a minor option and directors found other alternatives to presenting character interactions. The most basic one was simply to station the camera at a middle distance and create a more porous and open staging, with fewer planes of action and simple panning movements to follow characters.

One new approach relied not on wide-angle lenses but on lenses of long focal length. Instead of staging scenes in depth, putting the camera close to a foreground figure, filmmakers began keeping the camera back a fair distance and using long lenses to enlarge the action. This accompanied a trend toward greater location shooting; it’s easier to follow actors on a street or highway if the camera shoots with a telephoto lens. The long lens also reduces the volumes of each plane, so that figures tend to look like cutouts (4). This lens facilitated the development of those perpendicular images I’ve called, in some writing and on this blog, planimetric shots.

What fascinates me about this general pattern of stylistic change in the US is how many of the Euro auteurs go along with it. Take Fellini, who shifts from the bold depth compositions of I Vitelloni to the fresco-like flatness of Satyricon.

![]()

Likewise, Luchino Visconti’s early black-and-white work affords textbook examples of deep-focus cinematography, but in the 1960s he embraced the telephoto look, heightened by what we can call the pan-and-zoom tactic. In Death in Venice, the camera often scans a scene, searching out one player to follow then zooming back to reframe the figure in relation to others. One shot starts with the boy Tadzio, pans right across the hotel salon, to end on von Aschenbach, staring at the boy, and then zooming back to take in the larger scene.

Probably Rossellini’s 1960s films, such as Viva l’Italia! and Rise to Power of Louis XIV, were key influences on this look.

Leaving Europe, there’s Kurosawa, who was the first major director I know of to build zoom and telephoto lenses into his style. Satayajit Ray followed much the same trajectory from the Apu trilogy’s flamboyant depth to the pan-and-zoom close-ups of The Home and the World. Not every filmmaker took the long-lens option, but as it became commonplace in the 1960s, many major directors tried it.

What about Bergman? It seems that in most respects he went along with the general trends. We find deeply piled-up bodies early in his career (e.g., Port of Call, below) and through the 1950s and early 1960s (The Face, below).

Like his peers, with color and widescreen he shifted toward more open staging, long lenses, and zooms. For example, one telephoto shot of Cries and Whispers zooms back as the little girl emerges, zig-zagging, from behind the lace curtain.

We might conclude that Bergman mostly worked with the received forms of his day. At the level of shot design, The Face might have been shot by the Sidney Lumet of Fail-Safe. But Bergman did innovate somewhat, I think. Most obviously, he sometimes had recourse to the suffocating frontal close-up, as in a childbirth scene from Brink of Life.

He develops this visual idea by creating heads floating unanchored in both foreground and background. Here’s a famous image from Persona.

Pace Rosenbaum, I’d say that this sequence, with Elisabeth Vogler apparently quite oblivious to her husband’s mating with Alma, definitely “challenges conventional film-going habits”—or at least conventional ways we read a scene. It seems to combine the deep-space, big-foreground scheme of the 1940s with the tight close-ups of Bergman’s early work, and instead of specifying space it undermines it. We have to ask if what happens in the background is Elisabeth’s hallucination.

My case is very schematic, and we would need to study Bergman film by film and scene by scene to confirm that he stuck to the broad norms of his time. The norms themselves also deserve deeper probing than I’ve given them. (5)

But let’s push a bit further and examine Antonioni, that perpetual foil to Bergman. Broadly speaking, he passed through the same arc, from deep-focus compositions in the 1950s and early 1960s to telephoto flatness in his color work. Yet there are some important differences.

In the 1950s, unlike Bergman, Antonioni employed quite intricate staging, sustained by long takes. He usually didn’t opt for big foregrounds, favoring more distant framings and sidelong camera movements. The most famous instance is the startling 360-degree long take on the bridge in his first feature, Story of a Love Affair, but Le Amiche is also full of intricate staging in mid-ground depth. One scene shows fashion models bustling around after a successful show, congratulating the shop’s owner Clelia. She opens a card from her lover, is distracted by the arrival of her friends coming to congratulate her, and goes off with them. One model darts diagonally forward to investigate the message. All of this is handled in a single graceful take.

Antonioni relies on the fluid staging techniques developed in the early sound era and taken in diverse directions by Renoir, Ophuls, Preminger, Mizoguchi, and other directors of the 1930s and 1940s. Often, however, Antonioni’s characters move rather slowly and hold themselves in place, and as a result the overall spatial dynamic unfolds in marked phases. (6)

In the trilogy starting with L’Avventura, Antonioni relies on shorter takes and less florid camera movement. Now he emphasizes landscape and architecture so as to diminish the characters. If the expressionist side of Bergman plays up the psychological implications of the drama, the more austere Antonioni plays things down, “dedramatizing” his scenes by keeping the camera back, turning the figures away from us, and reminding us of the milieu. (You see the Antonioni influence on similar strategies in the work of Edward Yang, as I discussed recently on this blog.)

Once color came along, Antonioni changed his style, moving toward less dense staging and at times almost casual framing (as in The Passenger). He also had recourse to the telephoto technique, but I’d argue he brought something new to it. With Red Desert he accepted the abstraction inherent in the long lens and combined that with color design to create a pure pictorialism.

Ironically, Red Desert may have made Antonioni another sort of ‘expressionist’ than Bergman. The stylized palette of the film encourages us to ask if the industrial landscape is really so smeared and bleached out, or if we’re seeing it as Giuliana does. The same sort of painterly abstraction can be found in Zabriskie Point. In one scene, a pan over the travel decals on a family’s car window treats the boy inside as no more than another thin slice of space. Other scenes turn campus policemen into figures in grids.

You might even argue that the pan-and-zoom style gets a kind of meta-treatment in the climactic shot of The Passenger. There in a grandiose technical gesture Antonioni’s concern for architecture, his refusal to underscore a melodramatic plot twist, and his love of camera movement blend with the technology of the zoom. At the time, several of us (maybe Jonathan too) saw this shot as a response to Michael Snow’s Wavelength, relayed through the sensibility of Passenger screenwriter and avant-garde filmmaker Peter Wollen. Now it looks to me like a natural response of a very self-conscious artist to a stylistic trend of the moment.

A bestiary of stylists

To get crude and peremptory: Let’s say that once a director has reached maturity and become a confident artisan, several choices offer themselves. The filmmaker can be a flexible stylist, a stubborn stylist, or a polystylist (sorry for the awkward term).

A flexible stylist adapts to reigning norms. Bergman could be an aggressive-deep-focus director, then a pan-and-zoom director. Both approaches to staging and shooting preserved the expressive dimensions that mattered most to him: performance (chiefly face and voice), Ibsenesque bourgeois tragedy, Strindbergian play with dream and dissolution of the ego, and other elements.

Most of the major 1960s arthouse directors, from Truffaut and Wajda to Pasolini and Demy, were flexible stylists in this sense. So were a great many Hollywood and Japanese directors, such as Lubitsch and Kinoshita. Perhaps Ousmane Sembene, who also died recently, would be another instance. Buñuel becomes a fascinating case: He adopts the blandest, calmest version of each trend, creating a neutral technique, the better to shock us with what he shows.

A stubborn stylist pursues a signature style across the vagaries of fashion and technology. Dreyer from Vampyr onward does this; I argue in the book Jonathan cites that he seeks to “theatricalize” cinema in a way that goes beyond the norms of his moment. Perhaps Hitchcock and von Sternberg (at least in the 1920s and 1930s) fit in here as well. Bresson, Tati, and supremely Ozu were stubborn stylists. Give them a western or a porno to shoot, and they’d handle each the same way. (7)

This isn’t to argue that stubborn stylists never change or always do the same thing. Mizoguchi has a signature style and yet remains fairly pluralistic, at least at a scene-by-scene level. I think that the test comes in seeing how stubborn stylists persistently explore the constrained conditions they’ve set for themselves.

Signature styles help a filmmaker in the festival market, so we don’t lack for current examples of stubborn creators: Godard, Theo Angelopoulos, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Kitano Takeshi, Tsai Ming-liang, and Jia Zhang-ke. Granted, some of these may be rethinking their commitment to their stylistic premises.

A polystylist tries out different styles without much concern for what the reigning norms demand. Polystylistics holds a high place in modernist aesthetics. After the great triumvirate of Picasso, Joyce, and Stravinsky, with their bewildering arrays of periods and pastiches, the idea of the modernist as a virtuoso steeped in several styles became a powerful option. What’s been called postmodernism is no less favorable to polystylism; if you mix styles, you’ve presumably mastered them.

In cinema, some polystylists are just eclectic. Steven Soderbergh can give us the portentous pictorialism of The Underneath or Solaris, the grab-and-go look of Traffic, and the trim polish of Ocean’s 11. More deeply, there are directors like R. W. Fassbinder, Raoul Ruiz, and Oshima Nagisa who seem to pursue polystylistics on principle. It’s as if, rejecting the very idea of a signature style, they set themselves fresh, severe conditions for each project.

After The Boss of It All, we may want to count von Trier as a polystylist, not merely a director who changed his style from one phase of his career to another. Perhaps the best current example is Aleksandr Sokurov; who would dare predict what his next film will look like?

This whole entry is pretty sketchy, I grant you. The categories need further refining. I’ve ignored sound, which is very important. I’ve emphasized visual style, and just shooting and staging within that. (Nothing about lighting, cutting, etc.) So this is tentative—notes perhaps for a book-length argument. But I’ve made my point if you see that some ideas and some historical information can put intuitions about originality into a firmer framework.

And I’ve left the value judgments suspended. If you think originality trumps other criteria, then Bergman doesn’t probably come up as strong as Antonioni, let alone Bresson or Ozu or Dreyer. But if you can entertain the possibility that a great filmmaker can accept certain norms of his time, making those serve other channels of expression, then Bergman can’t automatically be faulted. At least thinking about him and his peers in the context of the history of film art gives us some data to ground our arguments. The world is more interesting and unpredictable than our opinions, especially those we formulated forty years ago.

(1) I actually hold this opinion.

(2) I assume that the arthouse auteurs were no less commercial filmmakers than their Hollywood counterparts. They were sustained by national film industries and supported by the international film trade. Eventually many were funded by Hollywood companies.

My friend and colleague Tino Balio is at work on a book tracing the role of overseas imports in the American film market of the 1940s-1960s, and it should be a real eye-opener to those who persist in counterposing art cinema and commercial production.

(3) Some of what follows is discussed in Part Four of Film History: An Introduction.

(4) I talk about both the deep-focus and long-lens tendencies in Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style and Chapter 5 of Figures Traced in Light.

(5) For a wide-ranging account of art-cinema norms, see András Bálint Kovács’ forthcoming book, Screening Modernism: European Art Cinema, 1950-1980.

(6) I analyze this tendency, using other scenes from Le Amiche, in On the History of Film Style (pp. 235-236) and Figures Traced in Light (pp. 151-152).

(7) Suo Masayuki’s My Brother’s Wife: The Crazy Family is a softcore film made in a pastiche of Ozu’s style.

Story of a Love Affair (Cronaca di un amore).

PS, Sunday 12 August: Only a day later, new thoughts about something else I should have said about generational tastes. In the light of the Woody Allen eulogy that appears in the New York Times today, I think there’s more of a sub-generational split than I’d initially suspected. So here’s another gesture toward the sort of history of taste that Jonathan mentions.

Allen is in his seventies, a decade older than Jonathan Rosenbaum and me. He came of age in the affluent decade after the war. Allen saw Bergman films in the mid- to late 1950s, probably against the backdrop of Neorealism, British comedy, and French Cinema of Quality. In that context, Bergman’s movies looked pretty revolutionary.

But Jonathan and I came to maturity, if that’s the right word, in the mid-1960s. When I got to college in 1965, French directors (notably Resnais, Godard, Truffaut) and the Czechs, Hungarians, and others were getting established in US film culture. Bergman, Fellini, and Antonioni were already senior directors and soon they were starting to make what many of us perceived as career mistakes (Juliet of the Spirits, The Passion of Anna, even Blow-Up). Also, of course, concerns about their political alignments came more to the fore as the decade wore on. Many of my friends thought that The Battle of Algiers left all other films in the shade. These factors may have made the Boomers suspicious of “arty” foreign imports, of which Bergman’s work was a central instance. Interestingly, The Dove, a parody of The Seventh Seal and a film-society staple, came out in 1968, when Bergman may have been wearing out his welcome.

[Speaking of parodies, the SCTV skit, “Scenes from an Idiot’s Marriage”, in which Jerry Lewis (Martin Short) suffers the indignities of a cuckolded Bergman hero, is well worth checking out. The SCTV Fellini/ Antonioni parody, “Rome Italian Style,” is also pretty good, especially for its excellently awkward dubbing.]

Interestingly, Scorsese in age falls midway between Allen and us Boomers, and he contributes a Times tribute to Antonioni today. Maybe I have to split the generations even more: Bergman for 1955-1960, Antonioni for 1961-1965, Godard for 1965-1970? (Just kidding.) What strikes me are the differences in the essays. While Allen ranges widely, reports conversations, and praises Bergman in general terms, Scorsese’s piece evokes the texture of L’Avventura, suggesting how disturbing and demanding it was to watch. Maybe he inadvertently backs Jonathan’s claim that Bergman didn’t challenge his audience as much as he might have?

I’m grateful as well to readers responding to my arguments. Michael Kerpan kindly spread the word about my post on imdb and the Criterion Forum. Kent Jones wrote to point out that any argument about Bergman’s influence has to take into account the high regard in which he’s been held in France, among both critics and filmmakers. Kent itemizes not only Godard, Truffaut, and Rivette but Assayas, Téchiné, and Desplechin. It’s a fair point. Antoine de Baecque anchors much of his magisterial history of Cahiers du Cinéma around the mesmerizing power of that busty still of Harriet Anderson, flaunted on a 1958 Cahiers cover and swiped by Antoine in The 400 Blows. In 2003, my old friend Jacques Aumont published a large critical study on Bergman. Cahiers’ next issue will be devoted to the director.

I’m grateful as well to readers responding to my arguments. Michael Kerpan kindly spread the word about my post on imdb and the Criterion Forum. Kent Jones wrote to point out that any argument about Bergman’s influence has to take into account the high regard in which he’s been held in France, among both critics and filmmakers. Kent itemizes not only Godard, Truffaut, and Rivette but Assayas, Téchiné, and Desplechin. It’s a fair point. Antoine de Baecque anchors much of his magisterial history of Cahiers du Cinéma around the mesmerizing power of that busty still of Harriet Anderson, flaunted on a 1958 Cahiers cover and swiped by Antoine in The 400 Blows. In 2003, my old friend Jacques Aumont published a large critical study on Bergman. Cahiers’ next issue will be devoted to the director.

Speaking of French critics and directors, on imdb above Bertrand Tavernier points out that my memory failed. I did see Scenes from a Marriage and Cries and Whispers before The Serpent’s Egg, not after, as my post suggests.

My late Bergman viewing remains gappy. I still haven’t seen the long version of Fanny and Alexander, which everyone assures me is a masterpiece. Last spring, my friend and Bergman scholar Paisley Livingston showed me portions of the TV film The Last Gasp (1995). It’s about Georg af Klercker, the fine Swedish director of the 1910s. It was intriguing, but I was put off by Bergman’s inadequate pastiches of af Klercker’s remarkably poised and complex shots. Now that’s fussy taste, I admit.

Simplicity, clarity, balance: A tribute to Rudolf Arnheim

DB here:

On Monday, at age 102, Rudolf Arnheim died. You can read his obituary here, and this is a lovely website devoted to his work. He was one of the most important theorists of the visual arts of the last century, and he had enormous impact on how people, including Kristin and me, think about film.

A good Gestalt

In parallel with E. H. Gombrich, who died in 2001, Arnheim brought modern psychological concepts into the study of visual art. His most famous work, Art and Visual Perception (1954, new version 1974) has the sort of magisterial presence that very few books in any era achieve. Arnheim delighted in the fact when, visiting a painter’s studio, he would find a spattered copy on the workbench. Of the revised edition, entirely rewritten, he noted:

All in all, I can only hope that the blue book with Arp’s black eye on the cover will continue to lie dog-eared, annotated, and stained with pigment and plaster on the tables and desks of those actively concerned with the theory and practice of the arts, and that even in its tidier garb it will continue to be admitted to the kind of shoptalk the visual arts need in order to do their silent work (new ed., x).

He aimed at theory that actively participates in the way artists do their job. The chapter titles of Art and Visual Perception deal with the nuts and bolts of picture-making: Balance, Shape, Form, Growth, Space, Light, Color, Movement, Dynamics, and Expression. No puns, slashes, dashes, or parentheses. What academic theorist today would so boldly announce their concern with the craft of creating images?

The book is subtitled, A Psychology of the Creative Eye, and the chapters’ subsection titles explain why. The hidden structure of a square . . . Vision as active exploration . . . Perceptual concepts . . . What good does overlapping do? . . . Why do children draw that way? . . . Gradients create depth . . . Visible motor forces . . . The priority of expression. Arnheim’s principal achievement in art theory was to integrate the Gestalt theory of perception with the traditional concerns of picture-making. He sought to show how perceptual laws discovered in the psychological laboratories of Berlin were intuitively applied by classic and modern artists.

As he put it, he was at the university at around age twenty:

My teachers Max Wertheimer and Wolfgang Köhler were laying the theoretical and practical foundations of gestalt theory at the Psychological Institute of the University of Berlin, and I found myself fastening on to what may be called a Kantian turn of the new doctrine, according to which even the most elementary processes of vision do not produce mechanical recordings of the outer world but organize the sensory raw material according to principles of simplicity, regularity, and balance, which govern the receptor mechanism.

This discovery of the gestalt school fitted the notion that the work of art, too, is not simply an imitation or selective duplication of reality but a translation of observed characteristics into the forms of a given medium (Film as Art, 3).

The Gestalters thought that these principles–figure/ground, completeness, good continuation, and the like–were fundamental to all human perception, across times and cultures. Art and Visual Perception makes a powerful case for this view. Today this position is so unfashionable that Arnheim’s calm confidence in it is quite stunning. For many scholars today, all that matters is what divides and differentiates us. But for eighty-plus years Arnheim emphasized ways in which we share a common experience of the world and of art.

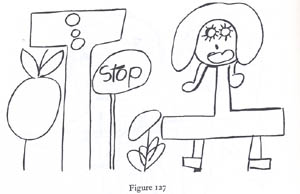

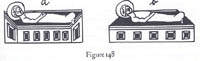

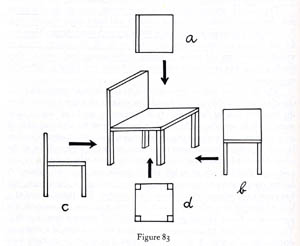

It’s often said that Arnheim favored modernist styles, like Cubism and expressionism, and that his emphasis on art as going beyond mere copying reflects modern artists’ will to distorted form. But he saw a deep continuity between classic art and modern art. Both traditions explored the perceptual force of form. Amazingly, he argues that the cockeyed creche in Fig. a conveys a stronger sense of three-dimensionality than the correct perspective presented in b. The “inverted” perspective encloses baby Jesus’ head fully, just a hollow cradle would.

It’s often said that Arnheim favored modernist styles, like Cubism and expressionism, and that his emphasis on art as going beyond mere copying reflects modern artists’ will to distorted form. But he saw a deep continuity between classic art and modern art. Both traditions explored the perceptual force of form. Amazingly, he argues that the cockeyed creche in Fig. a conveys a stronger sense of three-dimensionality than the correct perspective presented in b. The “inverted” perspective encloses baby Jesus’ head fully, just a hollow cradle would.

Arnheim saw the same form-giving activity at work in “primitive” art, the art of children, and even the art of the mentally ill. It turns out that the “universalism” of Gestalt theory underwrites diversity no less vigorously than the most ardent postmodernism.

Flexible striving

Arnheim made another contribution to our thinking about art, one that I think is rarely recognized. In a bold stroke, he extended the Gestalt conception of form beyond its concern with geometrical qualities and argued that form was inherently expressive. A triangle resting on its base wasn’t just balanced; it was weighty. We see the weeping willow as not just curved but sad; a skyscraper isn’t just tall, it’s aggressively thrusting upward. Every shape or movement we apprehend has a distinctive flavor and feeling. Indeed, he writes, “expression can be described as the primary content of vision”!

We have been trained to think of perception as the recording of shapes, distances, hues, motions. The awareness of these measurable characteristics is really a fairly late accomplishment of the human mind. Even in the Western man of the twentieth century it presupposes special conditions. It is the attitude of the scientist and the engineer or of the salesman who estimates the size of a customer’s waist, the shade of a lipstick, the weight of a suitcase. But if I sit in front of a fireplace and watch the flames, I do not normally register certain shades of red, various degrees of brightness, geometrically defined shapes moving at such and such a speed. I see the graceful play of aggressive tongues, flexible striving, lively color. The face of a person is more readily perceived and remembered as being alert, tense, concentrated rather than being triangularly shaped, having slanted eyebrows, straight lips, and so on (Art and Visual Perception, first ed., 430).

Arnheim found feeling in his forms.

Moving pictures

Arnheim wrote about many artforms, including mass media in his 1936 monograph on radio. His book on cinema, Film als Kunst (1932), was quickly translated into English as Film (1933). Always in search of greater clarity and point, Arnheim rewrote it in 1957. Oddly, he didn’t update it: You’ll search in vain for examples from the 1930s, 1940s, or 1950s. The touchstones remain Chaplin, Keaton, von Sternberg, and the Soviets. Arnheim held that cinema was essentially a pictorial art (see my earlier blog on this question) and that synchronized sound added very little; in fact, it might even inhibit visual experimentation. It was so easy to convey a story point with dialogue that lazy filmmakers would simply create photographed stage plays.

As a result, Arnheim is usually taken to be the summation of a certain strain of 1920s film theory. Like many earlier thinkers, Arnheim emphasized how film technique reshapes what is filmed. Close-ups, shot design, camera angles, and cutting make cinema no simple medium of reproduction. Film form transforms the world that is photographed. This position, commonplace today, was a real advance in the silent era and gave cinema artistic respectability, a subject that Arnheim reflected on thoughtfully in the 1933 edition of Film.

Again, Arnheim did more than synthesize current ideas. Theorists’ hunches that film stylized reality could now be grounded in Gestalt ideas about medium and form. In effect, Arnheim rewrote Film in the light of Art and Visual Perception, and the result was Film as Art. Here is the most famous passage:

Not until film began to become an art was the interest moved from mere subject matter to aspects of form. What had hitherto been merely the urge to record certain actual events, now became the aim to represent objects by special means exclusive to film. These means obtrude themselves, show themselves able to do more than simple reproduce the required object; they sharpen it, impose a style upon it, point out special features, make it vivid and decorative. Art begins where mechanical reproduction leaves off, where the conditions of reproduction serve in some way to mold the object (Film as Art, 57).

This, you might say, is Arnheim’s reply to Walter Benjamin’s theory of cinema as mechanical reproduction: no less than other artists, filmmakers use their medium, a photographic one, to create perceptually vivid effects akin to those in other arts.

Still, Arnheim held that film, like photography, has more limits than other arts. Tied to recording, film and photography can never achieve the range of expressive form we find in painting. I don’t believe this for a moment, but Arnheim clung to this opinion, I suspect, because of his deep love for creative freedom he found in other visual arts. And I sometimes think that for him, a painting harbored enough pushes, pulls, twists and torques. Movies just made explicit what was tactfully implied in still images.

Envoi

Kristin and I first saw Arnheim when we were graduate students at the University of Iowa, March 1972. He gave a lecture that stuck to his principles of 1933:

*Every art medium has a ceiling, beyond which it cannot effectively pass. The ceiling is somewhat low for the reproductive arts. Photography is more limited in what it can do than painting, and so is film.

*Films should be in black and white, the better to stylize reality. Are there no worthwhile color films? Pause. Red Desert, perhaps.

*Do you see many contemporary films? No.

Around 1980, I lined him up for a visiting lecture at UW. But he had to cancel; he had slipped on ice and broken his hip. He was then about seventy-five.

Later in the 1980s I visited Ann Arbor and had lunch with him. It was wonderful. By then I had read enough to ask him about Gombrich–an old friend and courtly opponent of his. (Read one of his reviews of Gombrich’s books to see what genuinely respectful disagreement looks like.) He saw pretty quickly that I was a Gombrichian and he gave a shrewd analysis of the dividing line: Gestalt psychology vs. ‘New Look’ cognitivism, illusions vs. expressive percepts, brain fields vs. schemas. He asked me to send me copies of my publications, which I did on and off during the decade. I never heard what he thought about my favorite fancy-pants sentence in Narration in the Fiction Film, when I contrasted J. J. Gibson’s theory of optical realism with Arnheim’s idea of expressiveness: “Gibson likes likeness, Arnheim loves liveliness.”

I thought of him often as I read more perceptual psychology. Gestalt work had once seemed to me a dead-end, but with David Marr’s theory of visual perception, a prototype of computational perceptual psychology, Gestaltism came roaring back. The “3D model representation” that Marr claimed operated in early vision uncannily echoes Arnheim’s discussion of our perception’s reliance on “characteristic aspects.” (Arnheim illustrates the idea with the various views of the chair, above. Which one is instantly recognizable as a chair?) And with contemporary interest in the relation between emotion and cognition, Arnheim’s theory of the expressive side of perception is creeping back too. Nothing worthwhile is forgotten, nothing goes away.

When we ran a book series at the University of Wisconsin Press, we were eager to publish an anthology of Arnheim’s film criticism, a collection originally published in German in 1977. Brenda Benthien, a close friend of Arnheim and his wife Mary, executed a lively translation and Arnheim supplied a touching introduction. A refugee of the Hitler years, an émigré across Europe and America, Arnheim summoned up the failure of the Weimar republic:

Even now I keep as a sort of talisman a bullet which in the days of the 1918 revolution, when I was fourteen, flew over the neighboring houses, bored a little hole through the windowpane, and fell inert on the carpet before my bed. Thus it began (Film Essays and Criticism, 3).

In the same introduction, Arnheim deplores the current state of cinema (“my basic objection to the talking film as a mongrel seems to me just as valid today as then”) and he warns against the cheapening of our vision:

Without the flourishing of visual expression no culture can function productively (5).

Aspiring film critics, and especially bloggers, should go back and read Arnheim on Keaton, Eisenstein, Gance, Pudovkin, Chaplin, von Sternberg, and other greats, as well as the essays “Style and monotony in film,” “Epic and dramatic film,” and especially “The Film Critic of Tomorrow.”

Scarcely a month goes by when I don’t have some idea that can be traced, however circuitously, to my reading of Arnheim. For instance, my blog on funny framings, posted a couple months ago, starts with his discussion of Chaplin’s The Immigrant. Arnheim’s theory of expression goes a long way toward explaining how composition can trigger laughter. I doubt that I’d be so alert to the possibilities of two-dimensional design in film shots if I hadn’t been tutored by Film as Art, Art and Visual Perception, The Power of the Center (1982, rev. 1988), his 1962 monograph on Picasso’s creative process in painting Guernica, and the essays in Toward a Psychology of Art (1966)–one of which is a skeptical review of Gombrich’s Art and Illusion. In preparing this entry, I found that my pleas that we probe the norms that guide filmmakers’ craft practices is just a clumsier restatement of this, which I discovered marked in Art and Visual Perception, the New Version:

Good art theory must smell of the studio, although its language should differ from the household talk of painters and sculptors (4).

Three years ago, after the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image convention in Grand Rapids, several of us from Madison–Ben Singer, Jen Chung, and Jonathan Frome–detoured back by way of Ann Arbor in order to call on Arnheim. He had just turned 100. He resided in an assisted-living facility, and his room was bright and clean, packed with books, remarkable drawings and paintings (Feininger, Köllwitz), a microfilm reader, and a worktable with a gigantic magnifying lens on an articulated arm. Conversation was difficult for him, but he seemed to understand everything we were saying. His smile was quick and his eyes were bright. When I showed him the first German edition of Film als Kunst I’d brought along, he turned it over in his hands as if he hadn’t seen one in years. He signed it, then shook his head apologetically at the shaky writing.

Now that Benjamin and Kracauer have become the prototypical Weimar intellectuals, it’s a pity that so many media students and professors are unaware of the importance of Arnheim’s work. His Leonardo-like interest in merging art and science is discouraged in a climate that posits the cultural construction of everything. He also writes with a grace and clarity that’s all too rare. In an unfashionable way, he exemplifies the passion, rigor, and dignity that interwar German intellectuals brought to the study of the arts. A lot of what he believed remains–what’s the word I want? Oh, yes–true.

Rudolf Arnheim, with Jonathan Frome, July 2004.

Line illustrations come from Art and Visual Perception.

New media and old storytelling

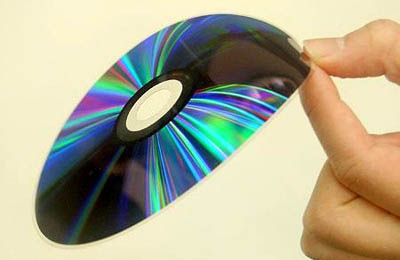

DB asks: To what extent has the DVD changed viewing habits and movie storytelling?

As everybody knows, a DVD offers more interactivity than a movie you watch in a multiplex. In a theatre, the movie rolls on, unaffected by anything you may do. But with a DVD you can pause the film, run fast forward, skip to a particular second, shuffle chapters, even play the thing in reverse.

Most minimally, the DVD offers greater convenience. You can halt the film so you can answer a phone call or zip back to replay a bit you might have missed. But some of us wonder if this new interactivity harbors more radical implications. Does the new flexibility of use allow us to experience the film in new ways?

In a mystery film, say there’s a clue at the half-hour mark. In a theatrical screening, we’re pressed forward with no time to ponder it. Watching the film on DVD lets us halt the film, ponder the clue as long as we like, and maybe track patiently back to earlier scenes to test our suspicions about what that clue means. Or suppose you decide to sample the film, browsing through the opening bits of several chapters? More radically, suppose we decide to watch the DVD in reverse? Nothing stops us, and we’d have an experience of the story very different from that of someone who watched the film in the normal order. Doesn’t this all suggest that it’s hard to generalize about what the “ordinary” viewer’s experience of a movie might be nowadays?

Now consider the craft of fictional filmmaking. The movie’s creators make choices about what story information to impart, when to impart it, and how to impart it. They assume that the viewer follows the story in the order mandated by theatrical projection, scene 1, then 2, 3 and onward. Likewise, the pace of uptake is set by the film—no slowing down or speeding up at the viewer’s will. But given the new conditions of digital consumption, these assumptions may be wrong. So shouldn’t the filmmakers take those conditions into account? And more specifically, haven’t some filmmakers already taken them into account? In other words, hasn’t the DVD transformed cinematic storytelling?

This question is important to me. I’ve long argued, along with Kristin, that mainstream US filmmaking, dubbed long ago “classical Hollywood cinema,” has cultivated a sturdy and pervasive tradition of storytelling. (1) That tradition depends on clearly defined characters pursuing well-defined goals. This commitment in turn creates a plot that displays linear cause and effect: In pursuing goals, the protagonist makes one thing happen, and that makes something else happen, which in turn triggers something else. Moreover, the mainstream tradition lays these actions and reactions along a fairly rigid structural layout. And this tradition depends on a system of narration that constantly reiterates the characters’ traits, their goals, important motifs, and the overall circumstances of the action. This is a fairly abstract description, I know; go to my analysis of Mission: Impossible III for a specific example of how the system can work.

But now home video allows our consumption to be highly nonlinear. By skipping or skimming DVD chapters, we may not register the plot or narration as the makers intended. Doesn’t this make hash of goal-directed action, character arcs, and all the other features of classical storytelling? Might we not be moving toward a “post-classical” cinema?

Movie as book

Let’s tackle the question first from the standpoint of the viewer. I think we can get help by recognizing this basic point: The DVD made a movie more like a book.

This sounds odd, because we think of digital media as replacing print. Yet consider the similarities. You can read a book any way you please, skimming or skipping, forward or backward. You can read the chapters, or even the sentences, in any order you choose. You can dwell on a particular page, paragraph, or phrase for as long as you like. You can go back and reread passages you’ve read before, and you can jump ahead to the ending. You can put the book down at a particular point and return to it an hour or a year later; the bookmark is the ultimate pause command.

We tacitly acknowledge the resemblance between the DVD and the book when we call the segments on a DVD its chapters, the list of chapters an index, and the process of composing the DVD its authoring.

With these similarities in mind, we can ask: How many people, on first contact, would sit down to watch a film in a nonlinear way?

My hunch: Just about as many who would buy or borrow a book and then proceed to read it in a nonlinear way. Now we can grant that if you have a nonfiction book in hand, you might pick out certain chapters as more interesting than others and move straight to those. Similarly, with a DVD documentary on penguins, some viewers might want to move straight to the chapter labeled Mating Habits.

With a fictional film, though, we’re much less inclined to graze and browse, just as with a novel. True, we might sample the novel before buying or borrowing it, but I’d bet the portion we’re most likely to sample is the opening chapter. With a fiction film on DVD, some viewers might skip to a chapter opening or two, but I expect that soon they’d settle down to watching the show at the order and pace of a theatrical screening. This is more or less what happens with literary fiction. The person who starts a novel will proceed in linear order in order to follow the story. It’s a revealing phrase: we’re following a path laid down for us, not racing ahead or falling back.

This isn’t to say that all consumers of fiction move at the same pace or read the same way. I’m just indicating that following the mandated order, page by page or shot by shot, is the default that people adhere to in the overwhelming majority of cases.

This suggests that pausing is the most common way we play an interactive role. When reading a book you might call out to your friend and reread a particularly striking description or funny dialogue exchange. When watching a film, you might stop and replay some images to enjoy them again. Another common act is probably quickly “paging back”—rereading or re-viewing a bit that just preceded the pause to remind ourselves of what’s going on at the moment.

Our purpose in starting a book or film at the beginning is to get into the story world and start to think and feel in relation to the information we get about it. But we don’t have to take that as our primary purpose. More extreme acts of “creative” spectatorship are tied to different purposes than learning about the story world. I suppose that teenage boys might well rent 300 when it comes out on DVD and fast-forward looking only for the scenes showing carnage or naked ladies….the same way that my high-school contemporaries rummaged through Terry Southern’s Candy digging out the good parts. (2) But this doesn’t seem to be a radically new way of using any medium, because the purpose—scanning a text for immediate gratification rather than narrative involvement—was common well before DVD.

Of course we students of cinema use the DVD commands in order to study a film, spooling back and forth to analyze it. But that usage isn’t a radical reworking of consumption either. Typically before we start to analyze a movie, we’ve already experienced it in the ordinary beginning-to-end way. Students of literature execute the same sort of back-and-forth moves studying a text that they’ve read before.

Finally, I’d suggest that a highly unorthodox mode of consumption, like setting out to watch a film in reverse at 8x speed, would become quite boring fast. As with so many things in life, just because you can do something doesn’t mean you’d enjoy it.

Speculation 1: The actual uses that people make of DVD interactivity are limited; traditional beginning-to-end consumption is the default.

Speculation 2: Pausing, paging back, and scanning for the good bits suggest that the most frequent DVD interactivity is familiar from other media, particularly books.

Guided interactivity

Let’s now consider things from the side of the creators. Knowing that films are seen on DVD, don’t filmmakers adjust their art and craft to this new medium? Of course they can provide revised versions, or directors’ cuts, along with alternative endings, deleted scenes, and other material that shed light on the film and the production process. But does the DVD format change the very act of conceiving and executing the story presented by the film?

Yes, in certain respects. In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I argue that the possibility of rewatching a film with little fuss encourages ambitious filmmakers to “load every rift with ore,” to pack in details that might not be noticed on a single viewing. One of my examples is the 8/2 motif in Magnolia. Likewise, the looping plotlines of Donnie Darko and the reverse-order one of Memento are amenable to being picked apart after several viewings. But before home video, you as a viewer could scrutinize such movies by just going back to the theatre and watching the film over and over, very attentively.

Clumsy as it seems, film nerds of my generation did this. I remember my thrill as a junior in college when I discovered, after rerunning a 16mm print of Citizen Kane on my apartment wall, the snowstorm paperweight that Kane clutches on his deathbed sitting on Susan’s vanity table the night he first meets her. Welles had, as it were, planted this clue for attentive viewers to spot. When we were lucky, we might get a film on a flatbed viewer and go through it reel by reel. Granted, the random-access aspect of DVD allows this sort of micro-analysis to be done much more easily, but it’s not different in kind from rolling up your sleeves and threading up a Films Incorporated print one more time.