Archive for the 'Film theory' Category

But what kind of art?

2046.

From DB:

We don’t have to think of film as an art form. A historian can treat a movie as a document of its time and place. A war buff could scrutinize Eastwood’s Iwo Jima movies for their accuracy, and a chess expert could sieve through Looking for Bobby Fischer to discover, move by move, what matches were dramatized. But most of the time we assume that cinema is an art of some sort.

Not necessarily high art. Cinema is often a popular art, or in Noël Carroll’s phrase, a mass art. From this angle, there’s no split between art and entertainment. Popular songs are undeniably music, and best-selling novels are instances of literature. Similarly, megaplex movies are as much a part of the art of film as are the most esoteric experiments. Whether those movies, or the experiments, are good cinema is another story, but cinema they remain.

So, at least, is our position in Film Art: An Introduction. We draw our examples from documentaries, animated films, avant-garde films, mainstream entertainment vehicles, and films aimed at narrower audiences. In other writing, Kristin has done research on high-art movements like German Expressionism and Soviet Montage (she wrote her dissertation on Ivan the Terrible), but she’s also written about popular cinema from Doug Fairbanks to The Lord of the Rings. I’ve indulged my admiration for Hou and Dreyer but also I’ve tried to tease out the aesthetics of Hong Kong action pictures and contemporary Hollywood blockbusters. Ozu gives us the best of both worlds: one of cinema’s most accomplished artists, he was also a popular commercial filmmaker.

Still, people who look upon cinema as an art don’t necessarily share the same conceptions of what kind of art it is. We have different conceptions of cinema’s artistic dimensions, and we won’t find unanimity of opinion among filmmakers, critics, academics, or audiences.

When we study film theory, this sort of question comes to the fore, and so today’s blog will be a bit more theoretical than most. Don’t let that scare you off, though; I’m trying for clarity, not murk.

Dimensions

People have tended to think of cinema as an art by means of rough analogies to the other arts. After all, film came along at a point when virtually all the other arts had been around for milennia. It’s commonly said that film is the only artform whose historical origins we can determine. So it’s been natural for people to compare this new medium with older arts.

Here are the dimensions that come to my mind:

*Film is a photographic art.

*Film is a narrative art.

*Film is a performing art.

*Film is a pictorial art.

*Film is an audiovisual art.

Let me say off the bat that I think that film is a synthetic medium, in the sense that all these features and more can be found in it. It’s like opera, which is at once narrative, performative, musical, and even pictorial. I mark out these dimensions simply to show some emphases in people’s thinking about cinema. As we’ll see, these ideas can be mixed together in various ways.

Film as a photographic art.

La petite fille et son chat (1900).

For many early filmmakers, such as the Lumière brothers (above), cinema was a means of capturing reality, documenting the visible world. Movies were moving photographs. Naturally, this conception of cinema leads us to treat documentary as the central mode of filmmaking.

It’s an appealing idea. G.W. Bush reading “My Pet Goat” wouldn’t be as revelatory presented as a painting or a theatre performance. On film we can see the event as it occurred and judge it as if we were in the same room. Even in fictional cinema, you can argue, the physicality of the actors, the tangibility of the setting, and the details–a train’s pistons, wind rustling through grass–could not be rendered, or even imagined, so powerfully in a non-photographic medium. In addition, consider Jackie Chan. His stunts are astonishing partly because we know he really did them and the camera photographed them. In an animated film, or a CGI-based one, a character’s acrobatics or brushes with death aren’t so thrilling.

The great film theorist André Bazin claimed that cinema’s photographic basis made it very different from the more traditional arts. By recording the world in all its immediacy, giving us slices of actual space and true duration, film puts us in a position to discover our link to primordial experience. Other arts rely on conventions, Bazin thought, but cinema goes beyond convention to reacquaint us with the concrete reality that surrounds us but that we seldom notice.

I think that Bazin’s idea lies behind our sense that long takes and a static camera are putting us in touch with reality and inviting us to notice details that we usually overlook in everyday life. (I try out this line of argument in relation to the tactility of Sátántangó here.) Moreover, you can argue that in treating cinema as a photographic art the filmmaker surrenders a degree of control over what we see and how we see it. Bazin made this claim about the Italian neorealists and Jean Renoir: creation becomes a matter of an existential collaboration between humans and the concrete world around us.

An example I used in my book Figures Traced in Light pertains to a moment in Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Summer at Grandfather’s, when a tiny toy fan falls between railroad tracks as a locomotive roars past. The fan’s blades stop, then spin in the opposite direction as the train thunders over it. The blades reverse again when the train has gone. (This detail might not be visible on video.) Did Hou know how the fan would behave? Isn’t it just as likely he simply discovered it after the fact, making his shot a kind of experiment in the behavior of things? Conceived as a species of photography, cinema can yield visual discoveries that no other art can.

Interestingly, cinema didn’t have to be photographic. Many early experiments with moving images were made with strips of drawings, such as the Belgian Émile Reynaud’s Praxinoscope. You can argue that recording glimpses of the world photographically simply proved to be the easiest way to obtain a long string of slightly different images that could generate the illusion of movement. Some filmmakers, such as George Lucas, hold that filmmakers are no longer tied to photography, and that the digital revolution will allow cinema to finally realize itself as a painterly art. More on that below.

Film as a narrative art.

Rope.

This is at the core of Hollywood’s explicit concerns. Producers, directors, crew, and of course screenwriters will agree that Without a good story, the movie fails. Our Indie and Indiewood filmmakers say they’re trying to find fresh stories, the ones that “haven’t been told yet.” Overseas filmmakers dominated by Hollywood tell us, “We have our own stories to tell.” Even the most celebrated arthouse filmmakers often say they’re interested in character as revealed through action. Resnais, Rivette, Fassbinder, Haneke, and all the rest may have told unusual stories, but still they told ’em.

Likewise, many viewers will say that they go to the movies to experience a story. Reviewers online and in the popular press, if they do nothing else, are obliged to sketch out the film’s plot, though they mustn’t give away the ending. Even in academia, most discussions of films focus on what happens in the narrative.

When we consider film genres, we’re usually concentrating on the narrative aspects of them. Most genres display typical characters and plot patterns. The backstage musical features aging stars and young hopefuls, caught up in the process of putting on a show. The horror film typically centers on a monster’s attack on humans, who must fight back. One type of science fiction shows us an overweening scientist striving to go beyond “what is proper for humans to know.” Both fans and scholars discuss other aspects of genre films, but narrative is often central to their concerns.

Historians have traced in great detail how filmmakers employed cinema as a narrative art, but we’re making more discoveries all the time. How, for instance, have films signaled flashbacks? How do they let us know we’re in a character’s mind, or attached to his or her optical point of view? How have they structured their plots? Can we pick out distinct approaches to narrative–in various periods, or genres, or national cinemas? How have narrative conventions changed over the years? Some of the answers Kristin and I have proposed can be found elsewhere on this site, and in our books and articles.

Film as a performing art.

The Marrying Kind.

In the West, since Plato and Aristotle we’ve distinguished between verbal storytelling and dramatic presentation, or performance. Films may be stories, but they’re not exactly told: they’re enacted. At Oscar time, we’re especially conscious of this analogy, for the Actor/ Actress nominees usually garner the most public attention.

Hollywood acknowledged cinema as a performing art in the 1910s, when it created the star system. The Star reminds us that film acting isn’t exactly the same as theatre acting, since an elusive charisma puts the performance across. John Wayne, Marilyn Monroe, Keanu Reeves, and many other “axioms of the cinema” aren’t good actors by stagebound standards, but once they show up on screen, you can’t take your eyes off them. This notion intersects with the photographic premise: we say that the camera seems to love them.

You can argue that Andy Warhol revamped this idea. His superstars weren’t photogenic by ordinary standards but their almost clinical narcissism and exhibitionism, captured by the camera, made them as mesmerizing as any matinee idols. Warhol films like Paul Swann create rather disturbing emotions by putting us in the presence of an awkward performer.

Reviewers place a premium on a movie’s performance dimension. After they’ve told us a bit of the plot , they appraise the job the actors did. Some ambitious critics have written wonderful appreciative essays on acting, as in Andrew Sarris’s “You Ain’t Heard Nothin’ Yet” and the collection OK You Mugs. See also the two collections of articles by Gary Giddins, which I discuss in an earlier blog.

Academic film studies has been slow to study acting systematically, partly because of a bias against considering cinema as a theatrical art, and partly because acting is very hard to analyze. But Charles Affron, Jim Naremore, Roberta Pearson, and Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs have greatly helped us understand performance practices. They show, among other things, that it isn’t just a matter of the face or the voice: a fluttered hand or a willowy stance can be as powerful as a frown or a line reading.

Film as a pictorial art.

Ohayu (Good Morning).

Progressive opinion in the silent era tended to deny that film was a performing art, since that would make it a form of theatre. No, film had unique capacities. Cinema was essentially moving pictures.

It was a visual art that unfolded in time, so a movie was neither quite the same as a painting (frozen in time) or as a stage play (not pictures but three-dimensional reality). The coming of sound somewhat reduced the appeal of this line of argument, but to a very great extent, students of film technique still emphasize cinema as a visual art.

Theorists argued that the film frame was a pictorial field, not a proscenium stage. Action unfolded in the frame in ways that dynamized space. The choice of angle, camera distance, camera movement, and the like created a visual fluidity that had no equivalent on stage or in other graphic arts. Even cinematic staging was quite different from blocking in a theatrical space. Add to this the ability to join one strip of pictures to another via editing, and we have a unique pictorial artform.

The theorists of the silent era, like Rudolf Arnheim and the Russian montagists, gave us a vocabulary and an orientation to studying visual style, but their legacy hasn’t been fully developed. Journalistic reviewers typically don’t pay that much attention to the way movies look. Nor, surprisingly, do academics. Film studies departments seldom pursue research into visual style and structure.

Here the professors are out of sync with the people whose work they study. Manuals and film schools teach composition, lighting, cutting, camera placement and the like. Professional filmmakers all over the world often think in pictures; they prepare shot lists and storyboards and care very much about the color values and editing patterns of the finished work. We can see their interest in visuals in DVD commentaries and supplements, and as viewers start to absorb bonus materials, perhaps their interest will be whetted too.

Needless to say, a number of avant-garde filmmakers, from Viking Eggeling and Walter Ruttmann to Deren, Brakhage, Ernie Gehr, James Benning, and Nathaniel Dorsky, have also thought of cinema as having the power to refresh, even redeem, our vision. But many of the most important directors aiming at broader audiences are also renowned for their visual styles. To mention just a few: Griffith, Feuillade, Sjostrom, Keaton, De Mille, Murnau, Lang, Dreyer, Lubitsch, and Dovzhenko; Ford, Hitchcock, and von Sternberg; Renoir, Ozu (above), Mizoguchi, and Ophuls; early Bergman, Antonioni, Jancsó, Resnais, Angelopoulos, Tarr, Tarkovsky, Kieślowski, Kiarostami, and Makhmalbaf; Scorsese, Spielberg, Michael Mann, and Tim Burton. Some, like Oshima, Sokurov, and Johnnie To, have been polystylistic, exploring many different visual pathways.

Film as an audiovisual art.

In the 1920s, many theorists feared the coming of synchronized sound, since that would thrust film back toward theatre. The “talkies” would sacrifice visual artistry to Broadway dialogue. This worry was mistaken, but I can sympathize. Probably the mandatory silence of early film pushed filmmakers to find means of visual expression. Would we have Chaplin and the other clowns if they could have spoken at the start?

Yet a great deal of sound cinema wasn’t canned theatre. Film became a synthetic medium blending imagery, the spoken word, sound effects, and music into something that was neither painting nor theatre nor illustrated radio.

Though he’s thought of as the premiere theorist of editing, Eisenstein actually developed this idea of audio-visual synthesis. He was fascinated by the ways in which images and music worked together, creating an idea or feeling that couldn’t be expressed by either one. If shot A followed by shot B gave us something that wasn’t present in either one, then why couldn’t shot A and sound B yield the same results? He believed that Disney’s 1930s films were the strongest efforts in this direction, as when a peacock fanned out his tail to a rippling melody. Eisenstein called it “synchronization of senses.”

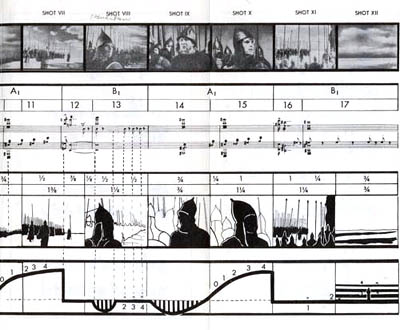

Eisenstein sometimes pushed this idea pretty far. His remarkable analysis of one sequence in Alexander Nevsky (sample above) tried to show how the movement of the viewer’s eye across a suite of shots actually mimicked the movement of the music. He made the case tough for himself because the shots contain almost no movement within them: Eisenstein claimed that we read the compositions from left to right, in time with the musical chords!

Not only Disney but many filmmakers of the 1930s experimented with audiovisual fusion–Kozintsev and Trauberg in Alone, Pudovkin in Deserter, Mamoulian in Love Me Tonight, Renoir in the final danse macabre of Rules of the Game, and Busby Berkeley’s Warners and MGM musicals. Welles made Citizen Kane a feast of audio-visual echoes, as when the wobbly descent of Susan’s singing voice is matched by the flickering of a stage light that finally goes out.

With magnetic and multichannel recording in the 1940s and 1950s, filmmakers could compose very complex sound mixes, and later improvements offered still more possibilities. After Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, we expected a movie to be an immersive audiovisual experience, like the light show at a rock concert. Scorsese, especially in Raging Bull and Goodfellas, created powerful mergers of music, sound effects, camera movement, and character movement. So did the Hong Kong kung-fu films of the 1970s and early 1980s. The spellbinding languor of Wong Kar-wai’s films stems largely, I think, from their synchronization of color, slow motion, drifting camerawork, and evocative music.

The avant-garde has pursued more elusive synchronizations of sense modes.The idea of synthesis was floated in the silent era, when experimenters like Oskar Fischinger used musical pieces to anchor their abstract imagery. This tendency has resurfaced in music videos, some of which (Michel Gondry’s in particular) have clear links to the experimental tradition. So too do the shorts and features of Peter Greenaway, especially in his collaborations with composer Michael Nyman. In a film like Prospero’s Books, Greenaway seems to follow Eisenstein in imagining a Wagnerian synthesis of writing, image, and sound.

By contrast, Godard explores all manner of unpredictable junctures between image and sound, with the tracks teasing us but always avoiding a complete coordination. Somewhat similar are the disjunctive image/sound juxtapositions in Peter Kubelka’s Unsere Afrikareise and Bruce Connor’s Report, or the inverse and retrograde organizations of Structural Film soundtracks like Michael Snow’s Wavelength and J. J. Murphy’s Print Generation.

Film academics have begun to analyze image/ sound juxtapositions, studying the development of early talkies and more recent Dolby technology. Arguably, film researchers now pay more attention to music than they pay to imagery. By contrast, most journalistic critics ignore a film’s soundtrack, except occasionally to comment on line readings and pop tunes. As for ordinary audiences, perhaps DVD and home theatre technology have made people more aware of how movies can saturate our senses with audiovisual correspondences.

Three waivers

1. Once I floated these distinctions in a seminar discussion, and a participant mentioned that cinema was also an emotional art. I’d agree that a lot of cinema aims at arousing feelings, but this idea can be found in all the dimensions I traced. Each conception of film favors different means of stirring up emotion.

For example, the photographic approach holds that recording and revealing the world is the most effective way to move spectators, while the narrative approach favors stories as the means to that end. The performance-based approach trusts that we’ll react empathetically to the emotional states displayed by our fellow humans, but the visual-art approach says that cinema can arouse feeling by manipulating pictures in time and space, perhaps even pictures that don’t show any people at all. Eisenstein argued that synchronization of senses was the most powerful form of emotional stimulation, creating in the viewer an “ecstasy” comparable to religious fervor. Beyond these general considerations, it would be worthwhile to tease out the different sorts of emotion that each perspective tends to emphasize.

2. Someone else might ask: What about other analogies? Filmmakers and critics have sometimes compared cinema to music or poetry. Shouldn’t those arts be added to the list?

I think that these comparisons show up principally within the broad idea of film as a pictorial art. The French Impressionist directors of the silent era thought that they were making “visual music,” and Brakhage and Deren’s conceptions of the “film lyric” were mainly pictorial. (See girishshambu for thoughts on the latter.) I’d suggest that filmmakers in the pictorial-art camp have looked to these adjacent arts for models of patterning (meter, rhythm, motif development) and imagery (metaphor and subjective states in lyric verse). Filmmakers are also attracted to the idea that music and poetry tend to be suggestive rather than explicit, conveying powerful feelings in elusive and open-ended ways.

Polemically, filmmakers often conjure up these musical and literary analogies to counter the mainstream cinema’s emphasis on narrative and performance. If we think of film as lyric or rhapsody, story seems less important. The same thing goes, I think, for thinking of film as moving architecture or kinetic sculpture; the analogy again targets film’s pictorial dimension and its non-narrative potential.

3. To think of film as having an affinity with another art form isn’t to say that they’re identical. Thinking of cinema as a performance-based art, for example, doesn’t commit you to saying that film acting is the same as theatrical acting. Instead, thinking along these lines seems to create a first approximation, an initial comparison that lets you move on to notice differences. Once you consider film as a pictorial art, you can then ask in what ways it differs from other pictorial arts, or in what ways this particular movie transforms or reworks the techniques of painting. Ballet Mécanique, which we analyze in Film Art (pp. 358-366), owes a lot to cubism, but its imagery isn’t identical to what Picasso, Braque, and Gris came up with on canvas. All of these analogies seem to work best as frameworks for sensitizing us to both similarities and differences between film and other arts.

And . . . so?

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me.

Each conception of film art harbors a good portion of truth. Each may fail to cover all of cinema, but for certain types of film, or particular movies, some are likely to be more helpful than others.

For example, it’s useful to consider David Lynch as making audiovisual works, in which blinking lights or grooves in pine planks seem uncannily synchronized with throbs and hums and Julee Cruise vibrato. Very often story and acting seem to precipitate out of an enveloping pictorial/auditory atmosphere. This isn’t to say that you couldn’t study narrative or performance in Lynch films; it’s just that taking up the audiovisual-mix perspective will throw certain aspects into sharper relief.

You could also argue that the Hollywood studio era blended many of these appeals into a single strong tradition. Story was important, but so was performance. Visual style was often striking, but so too was an expressive soundtrack that went beyond simply recording the dialogue. Sound effects, musical scores, and verbal hooks between scenes created imaginative resonances with the image track. Contrariwise, we can see some avant-garde traditions as taking a purist tack. In several of his films, Brakhage reduces narrative, purges performance, and bans sound: we have to engage wholly and solely with a pictorial experience.

Just as we can distinguish film traditions along these dimensions, we can contrast writers and thinkers. Some critics are very good in pinning down performance qualities, others excel at plot dissection or visual analysis. Arnheim is sensitive to pictorial values but he has little to contribute to understanding storytelling.

Bazin and Eisenstein are attuned to several of the dimensions I’ve traced out. Bazin’s interest in cinema’s photographic basis also alerted him to pictorial possibilities, like deep-focus and camera movement. Eisenstein, famous for his ideas on cinema’s visual dimension, was as I’ve said interested in sound as well. He was no less concerned with film performance, which he conceived as expressive movement (to be synchronized with properties of the image and the soundtrack). But he voiced almost no interest in narrative or photography.

I warned you that this blog would be theoretical, but I hope the takeaway message is clear. Cinema is teeming with artistic possibilities, and each of these frameworks can illuminate certain areas of choice and control. We don’t need to pick a single creed to live by, but we deepen our understanding of film by being sensitive to as many as we can manage.

Film forgery

DB here:

In early July 1947, about two weeks before I was born, an alien spacecraft crashed near Roswell, New Mexico. Local ranchers found scattered debris, and soon the US government had cordoned off the area. At the crash site was a flying saucer.

Around it lay several alien creatures. They were small and slender, with large heads, dark slanted eyes, and only four fingers. They were clutching small, flat control boxes. One creature was still alive, and it was taken to an Air Force base in Texas, where it lived for a few more years. The dead bodies were autopsied, and at least one autopsy was filmed.

The US government tried to keep the Roswell incident a secret, but dogged researchers have brought to light eyewitness testimony, official documents, and leaks. There is but one conclusion to draw. We have encountered beings from another planet.

Everything I have just said is almost certainly untrue, except for that part about my being born.

Artistic crimes

Although I’ve been interested in UFOs since I was a kid, what triggered this blog was the recent scandal around pianist Joyce Hatto. Her husband has confessed that her many CD performances of classical pieces were actually digital copies of other pianists’ releases. Critics who praised her virtuosity now have red faces. Denis Dutton, a philosopher of art specializing in what he calls “artistic crimes,” has written a lively essay about the mess.

Summing up what is now a pretty well-established position in aesthetics, Dutton writes that our full understanding of an artwork depends on a general sense of how the work came to be what it is. We may say that all that matters are the words on the page or the paint on the canvas or the sounds in our ear. But our understanding of those sensory features depends upon assumptions about the origins and authenticity of the work.

Here’s Dutton:

The Joyce Hatto episode is a stern reminder of the importance of framing and background in criticism. Music isn’t just about sound; it is about achievement in a larger human sense. If you think an interpretation is by a 74-year-old pianist at the end of her life, it won’t sound quite the same to you as if you think it’s by a 24-year-old piano-competition winner who is just starting out. Beyond all the pretty notes, we want creative engagement and communication from music; we want music to be a bridge to another personality. Otherwise, we might as well feed Chopin scores into a computer.

Dutton has written many subtle and enjoyable pieces on what he calls aesthetic crimes—plagiarism, forgery, and the like. (See his website for many of these, along with continuing updates on his Hatto comments.)

Both plagiarism and forgery present a false history of how a work came into being. You commit plagiarism when you claim as your own something that somebody else created. The Hatto case is plagiarism, just as much as if one college student submits a paper that her roommate has already submitted for another course. A forgery is in a way the reverse: You make the artwork but claim that it was actually created by somebody else, typically somebody famous.

It’s interesting to speculate about what a plagiarized film would be. You can plagiarize somebody’s script by passing it off as your own. Periodically there are lawsuits from aspiring screenwriters claiming that producers ripped off spec scripts. But can you plagiarize a movie itself?

I suppose you can try, but it would be very hard to pull off. I might swipe a finished film’s negative from the lab and then make new credit sequences that replace the director’s name with mine. But I could hardly expect to get away with it, since nearly everybody involved would notice. Perhaps I could find an old forgotten film and then stick my name in there somewhere. Again, though, I’d have to explain how I could have been around to make that 1930s Monogram musical or 1960s Taiwanese kung-fu film. As Dutton points out, I’d have to tell a plausible story about how the work came to be.

What if I just swipe bits? Recall that a plagiarism can be partial or total. Even if you pluck just a paragraph or two from your roommate’s term paper and write the rest of yours unaided, that still counts as plagiarism. But if your roommate makes a film, and you lift a sequence from it for your own, the case for plagiarism seems to me less clear—especially if she gives you the same sort of permission she might grant for a paper.

Does Bruce Conner’s use of stock footage in A Movie constitute plagiarism? We assume that he didn’t shoot all this material, yet he doesn’t give credit to any of his sources. Indeed, as he once wrote to Kristin and me, “Only the splices are mine.”

We’d now be inclined to say that Conner appropriated the shots, something a great deal of contemporary art does. Rappers, samplers, and electronic artists like Moby are clearly seizing work without acknowledgment. Perhaps entertainment companies are in effect complaining that YouTube downloads and Web mashups are plagiarism. Yet there’s no intent to deceive the viewer about the source, so plagiarism doesn’t seem the right concept for these instances.

What about cases in which one director replaces another on a film project and assimilates material that the first one shot? Did Richard Lester plagiarize Richard Donner’s footage for Superman II? It sounds weird to say that; Lester just used parts of what Donner left.

Literary plagiarism can involve stealing not only exact wording but also original ideas. This is a fuzzy area, obviously, since ideas can’t be copyrighted. But it’s even fuzzier in filmmaking, where such swiping is pretty common. All those copies and unauthorized remakes of Hollywood films, like Hong Kong Pretty Woman and Kaante, the Bollywood version of Reservoir Dogs, might count as plagiarism. (The producer of Kaante calls it an homage.) Still, my inclination is to say that plagiarism is a difficult concept to transfer to the visual/moving image arts; its core application may be literary and, as the Hatto case reveals, musical performance.

Anyhow, today I’m interested in the other major aesthetic crime, forgery. The question is: Can you forge a film?

Forgery and pastiche

Nowadays, especially after Forrest Gump, we’re accustomed to seeing simulated documentary footage in fictional films. The earliest example I can recall is Citizen Kane, in which the newsreel fakes old footage showing Kane campaigning with Teddy Roosevelt or standing beside Hitler.

Such shots don’t claim to be factual. No matter how realistic the shot looks, the presence of the protagonist tells us that it’s functioning within a fictional tale. There is, in other words, no question of deceit. It’s a case of artistic license, somewhat like dressing contemporary actors in period costume. Had Welles claimed that he had discovered old newsreel clips containing a mysterious man who resembled him, that would be a different story.

I’d suggest that such frank efforts to mimic the look and feel of older footage fall into the category of pastiche. Pastiche is the acknowledged copying of techniques of recognized art styles. In Stravinsky’s neoclassical period, he composed Pulcinella, an overt pastiche of Pergolesi.

It’s a separate but interesting question about how accurate a filmic pastiche is. The Good German, I suggested in previous posts, tries to be a pastiche, but it isn’t very skilful. Indeed, most aren’t. Bergman’s TV film The Last Scream (1995) includes a pastiche of the great 1910s filmmaker Georg af Klercker, but it’s not faithful to af Klercker’s style. (The mock silent film in Prison and Persona is somewhat better.) Welles’ pastiche of old footage in Kane‘s “News on the March” segment is more carefully done, especially for its time. The movement is convincingly jerky for silent film shown at sound speed, and Welles cleverly scratched and mis-exposed some of the staged footage, anticipating a technique often used today.

The most convincing film pastiche I know since Kane comes in the Japanese film To Sleep so as to Dream (Yume miruyoni nemuritai, 1986). The plot involves two detectives trying to find a lost silent film, and at intervals we see clips of it, a swordplay movie (chambara). The shooting style is very close to the flashy technique we see in films from the era; obviously the director Hayashi Kaizo studied surviving chambara carefully. In one scene, a swordfighter pauses in a doorway, and we see him over the shoulder of his adversary (first image below). As the fighter makes a hurling movement, we cut in a bit closer. Suddenly the foreground figure’s arm jerks up, revealing a dagger jabbed into his wrist (second image below).

Hayashi has also faded and flared the imagery, as if our print had degraded through duping and ill use.

Pastiches aren’t forgeries because there’s no intent to deceive. Just as important, the history of their production tells us that they aren’t genuine. As Dutton points out, it’s not enough for a forgery to look like an old artwork; to succeed, it needs a provenance, a false history of creation and subsequent ownership. I can think of two well-known films that can be considered forgeries to some degree.

With typical Scottish pragmatism

Peter Jackson and Costa Botes’ Forgotten Silver (1995) tells the story of the neglected New Zealand filmmaker Colin McKenzie. McKenzie started making films around the turn of the century, and in the course of his career he built his own camera, manufactured his own film stock, invented talking pictures and color cinematography, shot the first close-up, and erected a gigantic set in the New Zealand bush. Many experts, including Leonard Maltin and various archivists, attest to McKenzie as a visionary filmmaker on a par with D. W. Griffith.

Of course he never existed. But in the straight-faced manner of This is Spinal Tap, Forgotten Silver pretends that he did. The result is a brilliant parody of the filmmaker documentary as practiced above all by Kevin Brownlow. We get the talking-heads experts, the search for lost footage and locations, the pan-and-zoom coverage of old stills, and the terse journalistic voice-over. (“With typical Scottish pragmatism he built his farm the hard way.”) The film makes fun of nationalistic film history (we did it before the others) and the biographical convention that treats the artist as a rebellious, suffering soul.

The silliness of the enterprise is pretty apparent. The resourceful McKenzie is a one-man film industry. He devises a projector driven by steam power, he manufactures film emulsion from eggs, he builds his Salome city single-handed, and a Russian woman named Alexandra Nevsky tells us about Stalin’s interest in our hero. To anybody who knows Harvey Weinstein’s tendency to slice up the films he distributes, his remark about taking an hour out of McKenzie’s masterwork gives the whole game away.

There are clips as well. The passages from McKenzie’s Griffithian feature Salome are fair approximations of 1920s international style, a bit à la Guy Maddin, while the oldest shots look remarkably accurate.

But Jackson and Botes decided to go Spinal Tap one better. Before Forgotten Silver aired on Kiwi television, they let a journalist publish a story suggesting that McKenzie really existed. The mockumentary was taken for truth, and McKenzie immediately became a new national hero. Startled, the filmmakers quickly confessed their chicanery. Some people enjoyed the laugh, but others felt cheated and muttered about artists who fool around at the taxpayers’ expense. The fullest account I know is in Brian Sibley’s biography Peter Jackson: A Film-Maker’s Journey (Hammersmith: HarperCollins, 2006), 280-302. On the web, have a look here.

Because of the Jackson/Botes hoax concerning the “rediscovered” footage, the faked McKenzie scenes became forgeries, at least for a little while. When the mischief was discovered, the clips stood revealed as parodies or pastiches of silent film. If we have reason to believe that the footage is authentic, we think of McKenzie as a pioneer filmmaker. If we’re told it’s all faked, we congratulate our adept contemporaries.

In the spirit of Forgotten Silver are other nonexistent but rediscovered filmmakers. Most recently we have J. X. Williams, conjured up by Craig Baldwin and Noel Lawrence. Williams’ Peep Show was presented as an authentic 1965 movie, although many had their doubts when they saw footage lifted from The Man with the Golden Arm and other pictures. Lawrence insists that Williams existed and has set up a website dedicated to him, but one has to believe that it’s less an effort to deceive than a PoMo performance exercise.

The Gray’s anatomy

The grandest film forgery I know is Alien Autopsy. This has been a favorite of mine since I saw the Fox TV program, Alien Autopsy: Fact or Fiction?, broadcast in the summer of 1995. Kristin and I were especially pleased to see our old friend Paolo Cherchi Usai, then of Eastman House, as a talking head in it. I got the movie on laserdisc, hoping to use it in a film theory class. I never did, but now I get a chance to blog about it! The show is available on DVD, including the full “original” footage. A useful Wikipedia overview is here.

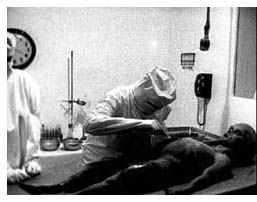

The film shows an autopsy performed on one of the saucer creatures, known in UFO parlance as a Gray. The grainy black-and-white footage presented to the public runs about 16 minutes, but it’s supposedly drawn from much more material. There seem to me three central issues in establishing its authenticity: what we are shown, how we are shown it, and when it was made.

What we see is a sterile white room with a stiff Gray stretched out on a lab table. Two figures in decontamination suits move around the table, cut into the body, and remove various organs. A third, rather creepy figure can occasionally be glimpsed in a window watching. The furnishings are pretty sparse, but you can see a clock, a wall phone, a microphone, and an instrument tray.

What we see is a sterile white room with a stiff Gray stretched out on a lab table. Two figures in decontamination suits move around the table, cut into the body, and remove various organs. A third, rather creepy figure can occasionally be glimpsed in a window watching. The furnishings are pretty sparse, but you can see a clock, a wall phone, a microphone, and an instrument tray.

As you can imagine, what we see has been intently scrutinized. Is the Gray an organic body or a dummy? Do the surgeons follow proper autopsy procedures? Are the clothes and furnishings faithful to the period around 1947? Special-effects experts have talked about how difficult it would be to design a fake creature, physicians have assessed the surgical techniques, and researchers have tried to establish when wall phones with coiled cords came into use. The Fox special includes some of these debates.

How we’re shown the autopsy has also become a matter of controversy. The film was shot with a handheld 16mm camera, and the cinematographer constantly shifts position. The camera stays quite close, circling the surgeons and moving toward and away from the corpse. As the camera draws closer to the body, the shot often goes out of focus.

How we’re shown the autopsy has also become a matter of controversy. The film was shot with a handheld 16mm camera, and the cinematographer constantly shifts position. The camera stays quite close, circling the surgeons and moving toward and away from the corpse. As the camera draws closer to the body, the shot often goes out of focus.

Some experts on combat cinematography have claimed that this is a plausible way to cover the action. The camera weaves around because the operator is trying to stay out of the way of the doctors, and the fixed-focus lenses can’t sustain focus in the natural light of the room. Other experts have said that the authorities would have handled this momentous event in a far more careful way, employing several fixed cameras, color film, and brilliant lighting. Skeptics point out that the monochrome imagery, bobbing camerawork, and loss of focus on details all conveniently make the event harder to see.

So it’s rather hard to determine the autopsy’s authenticity just by looking at the footage. We need external information about its provenance.

Funny thing . . . that’s just what’s lacking.

When was the film made? Well, does it employ 1947 film stock? Answer: Not clear. Eastman Kodak representatives have verified that the pieces of film they were shown could have come from 1947, or from 1927, or 1967. But were the pieces of film that the experts examined taken from the footage showing the dead Gray? Not clear. Moreover, the owner of the footage steadfastly refused to submit the film to a chemical analysis that would determine its age. Big problem here.

Further, what was the chain of custody for the footage? Again, not clear.

Roswell Incident eyewitnesses tend to hang onto physical evidence for decades. One man who nabbed a debris fragment kept it on top of his TV set. But when inquiring minds ask to have a look, the artifacts suddenly go missing.

That makes it remarkable that a former military photographer identified as Jack B. came forward claiming to hold several hundred reels of autopsy footage. In the early 1990s Jack offered to sell the material to TV producer Ray Santilli. But Jack didn’t want his real name divulged. That yields another problem with establishing provenance.

Things get wilder. Michael Hesemann and Philip Mantle, in Beyond Roswell (1997), argue that the creature on the table isn’t a Roswell victim at all but a corpse recovered from one of many other crashes that took place at the time. Hesemann and Mantle have also deciphered the markings on the debris shown in Santilli’s film. The text turns out to be similar to ancient Hebrew, classical Greek, and other ancient languages. Did the Grays teach our ancestors their culture? To read this literature is truly to plunge down the rabbit hole. (That’s why I like it.)

So the when question seems to be as murky as the others.

Skeptics have torn into this movie along all three dimensions. The most convincing demolitions of it seem to me the very early piece by Joe Nickell, in the Skeptical Inquirer of November/ December 1995 and Joe Longo’s 1997 dissection on the Society of Operating Cameramen’s website. Longo, president of the International Combat Camera Association, offers a detailed critique of the case. For what it’s worth, many who believe in UFOs also immediately took the film to be bogus.

So is Alien Autopsy a forgery? Yes. Last spring Santilli admitted faking the film, but he offered a new explanation. He maintains that there was a genuine autopsy film, but after he bought it, he found that 95% of it had “oxidized,” whatever that means. So he staged and shot a film that would replicate what the mysterious Jack B. had originally shown him. Santilli explained: “It’s no different from someone restoring a work of art like the Mona Lisa or the Sistine Chapel.”

A special-effects specialist has acknowledged making the dummy Gray. Santilli also faked the inscribed debris shown in the film. At this point Philip Mantle, who had written yet another book claiming that the film might be genuine, denounced the entire affair as a hoax.

In sum, we have the intent to deceive coupled with the wrong provenance. As Dutton would point out, we see the film differently when we know what sort of achievement it is: a middling piece of fakery.

In a remarkable piece of timing, a British feature film was released just as Rick Santilli admitted his duplicity. It was called Alien Autopsy, and it shows two lads setting out to film a faked Gray autopsy. Santilli was credited as a producer. I leave it to you to decide if that movie is an adaptation, a forgery, a plagiarism, a pastiche, or just the extension of a brand.

Thanks to Paisley Livingston, Mette Hjort, and Bérénice Reynaud for discussing many of these matters with me. Paisley in particular gave me helpful pointers and showed me the af Klercker pastiche by Bergman. Thanks also to George Thomas for a factual correction.

P.S. 27 March 2007: Nate Dorward writes to remind me of First on the Moon, a 2005 mockumentary that was taken by the press as a faithful record of Russia’s space program. I haven’t seen it, but it sounds like a Forgotten Silver case: a pastiche or parody that became, inadvertently, a forgery.

Salome crushed by the guards’ shields in Colin McKenzie’s 1920s epic Salome.

This is your brain on movies, maybe

United 93.

From DB:

Normally we say that suspense demands an uncertainty about how things will turn out. Watching Hitchcock’s Notorious for the first time, you feel suspense at certain points–when the champagne is running out during the cocktail party, or when Devlin escorts the drugged Alicia out of Sebastian’s house. That’s because, we usually say, you don’t know if the spying couple will succeed in their mission.

But later you watch Notorious a second time. Strangely, you feel suspense, moment by moment, all over again. You know perfectly well how things will turn out, so how can there be uncertainty? How can you feel suspense on the second, or twenty-second viewing?

I was reminded of this problem watching United 93, which presents a slightly different case of the same phenomenon. Although I was watching it for the first time, I knew the outcomes of the 9/11 events it portrays. I knew in advance that the passengers were going to struggle with the hijackers and deflect the plane from its target, at the cost of all their lives. Yet I felt what seemed to me to be authentic suspense at key moments. It was as if some part of me were hoping against hope, as the saying goes, that disaster might be avoided. And perhaps the film’s many admirers will feel something like that suspense on repeated viewings as well.

Psychologist Richard Gerrig in his book Experiencing Narrative Worlds calls this anomalous suspense: feeling suspense when reading or viewing, although you know the outcome.

Anomalous suspense: Some theories

Anomalous suspense has been fairly important in the history of film. One of the most famous instances in the early years of feature film is the assassination of President Lincoln in Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915). Griffith prolongs the event with crosscutting and detail shots in a way that promotes suspense, even though we know that Booth will murder Lincoln. Anomalous suspense, of course, isn’t specific to movies; we can feel this way reading a familiar book or watching a TV docudrama about historical events. Young children listening to the story of Little Red Riding Hood seem to be no less wrought up on the umpteenth version than on the first.

This is very odd. How can it happen?

One answer is simple: What you’re feeling in a repeat viewing, or a viewing of dramatized historical events, isn’t suspense at all. Robert Yanal has explained this position here. He suggests that you’re responding to other aspects of the story. Maybe in rewatching Notorious you’re enjoying the unfolding romance, and you attribute your interest to suspense. And there are feelings akin to suspense that don’t rely on uncertainty–dread, for instance, in facing likely doom. (This is my example, not Yanal’s, but I think it’s plausible.) Another possibility Yanal floats is that on repeat viewings, you have actually forgotten what happens next, or how the story ends.

Yanal’s account doesn’t fully satisfy me, largely because I think that most people know what suspense feels like and attest to feeling it on repeat viewings. I did feel some dread in watching United 93, but I think that was mixed with a genuine feeling of suspense–a momentary, if illogical uncertainty about the future course of events. In any case, I didn’t forget what happened at the end; I expected it in quite a self-conscious way.

Yanal’s account doesn’t fully satisfy me, largely because I think that most people know what suspense feels like and attest to feeling it on repeat viewings. I did feel some dread in watching United 93, but I think that was mixed with a genuine feeling of suspense–a momentary, if illogical uncertainty about the future course of events. In any case, I didn’t forget what happened at the end; I expected it in quite a self-conscious way.

Richard Gerrig, the psychologist who gave anomalous suspense its name, offers a different solution. He posits that in general, when we reread a novel or rewatch a film, our cognitive system doesn’t apply its prior knowledge of what will happen. Why? Because our minds evolved to deal with the real world, and there you never know exactly what will happen next. Every situation is unique, and no course of events is literally identical to an earlier one. “Our moment-by-moment processes evolved in response to the brute fact of nonrepetition” (Experiencing Narrative Worlds, 171). Somehow, this assumption that every act is unique became our default for understanding events, even fictional ones we’ve encountered before.

I think that Gerrig leaves this account somewhat vague, and its conception of a “unique” event has been criticized by Yanal, in the article above. But I think that Gerrig’s invocation of our evolutionary history is relevant, for reasons I’ll mention shortly.

Suspense as morality, probability, and imagination

The most influential current theory of suspense in narrative is put forth by Noël Carroll. The original statement of it can be found in “Toward a Theory of Film Suspense” in his book Theorizing the Moving Image. Carroll proposes that suspense depends on our forming tacit questions about the story as it unfolds. Among other things, we ask how plausible certain outcomes are and how morally worthy they are. For Carroll, the reader or viewer feels suspense as a result of estimating, more or less intuitively, that the situation presents a morally undesirable outcome that is strongly probable.

When the plot indicates that an evil character will probably fail to achieve his or her end, there isn’t much suspense. Likewise, when a good character is likely to succeed, there isn’t much suspense. But we do feel suspense when it seems that an evil character is likely to succeed, or that a good character is likely to fail. Given the premises of the situation, the likelihood is very great that Alicia and Devlin will be caught by Sebastian and the Nazis, so we feel suspense.

What of anomalous suspense? Carroll would seem to have a problem here. If we know the outcome of a situation because we’ve seen the movie before, wouldn’t our assessments of probability shift? On the second viewing of Notorious, we can confidently say that Alicia and Devlin’s stratagems have a 100% chance of success. So then we ought not to feel any suspense.

Carroll’s answer is that we can feel emotions in response to thoughts as well as beliefs. Standing at a viewing station on a mountaintop, safe behind the railing, I can look down and feel fear. I don’t really believe I’ll fall. If I did, I would back away fast. I imagine I’m going to fall; perhaps I even picture myself plunging into the void and, a la Björk, slamming against the rocks at the bottom. Just the thought of it makes my palms clammy on the rail.

Carroll points out that imagining things can arouse intense emotions, and his book The Philosophy of Horror uses this point to explain the appeal of horrific fictions. The same thing goes, more or less, for suspense. If the uncertainty at the root of suspense involves beliefs, then there ought to be a problem with repeat viewings. But if you merely entertain the thought that the story situation is uncertain, then you can feel suspense just as easily as if you entertained the thought that you were falling off the mountain top.

In other words, the relation between morality and probability in a suspenseful situation is offered not to your beliefs but to your imagination. When you judge that in this story the good is unlikely to be rewarded, you react appropriately–regardless of what you know or believe about what happens next. Carroll outlines this view in his book Beyond Aesthetics.

How are we encouraged to entertain such thoughts in our imagination? Carroll indicates that the film or piece of literature needs to focus our attention on the suspenseful factors at work, thus guiding us to the appropriate thoughts about the situation. There might, though, be more than attention at work here.

The firewall

In Consciousness and the Computational Mind (1987), psychologist Ray Jackendoff asked why music doesn’t wear out. When composers write tricky chord progressions or players execute startling rhythmic changes, why do those surprise or thrill us on rehearing? Similarly, you’ve seen the Müller-Lyer optical illusion many times, and you know that the two horizontal lines are of equal length. You can measure them.

Yet your eyes tell you that the lines are of different lengths and no knowledge can make you see them any other way. This illusion, in Jerry Fodor‘s phrase, is cognitively impenetrable.

We can reexperience familiar music or fall prey to optical illusions because, in essence, our lower-level perceptual activities are modular. They are fast and split up into many parallel processes working at once. They’re also fairly dumb, quite impervious to knowledge. Jackendoff suggests that our musical perception, like our faculties for language and vision, relies on

a number of autonomous units, each working in its own limited domain, with limited access to memory. For under this conception, expectation, suspense, satisfaction, and surprise can occur within the processor: in effect, the processor is always hearing the piece for the first time (245).

The modularity of “early vision”–the earliest stages of visual processing–is exhaustively discussed by Zenon W. Pylyshyn in Seeing and Visualizing: It’s Not What You Think (2006).

As students of cinema, we’re familiar with the fact that vision can be cognitively impenetrable. We know that movies consist of single frames, but we can’t see them in projection; we see a moving image.

Early vision works fast and under very basic, hard-wired assumptions about how the world is. That’s because our visual system evolved to detect regularities in a certain kind of environment. That environment didn’t include movies or cunningly designed optical illusions. So there might be a kind of firewall between parts of our perception and our knowledge or memory about the real world.

Daniel J. Levitin’s lively book, This is Your Brain on Music summarizes the neurological evidence for this firewall in our auditory system. When we listen to music, a great deal happens at very low levels. Meter, pitch, timbre, attack, and loudness are detected, dissected, and reconstructed across many brain areas. The processes runs fast, in parallel, and we have very little voluntary control of them, let alone awareness of them. Of course higher-level processes, like knowledge about the piece, the composer, or the performer, feed into the whole activity. But that’s inevitably running on top of the very fast uptake, disassembly, and reassembly of sensory information. Go here for more information on the book, including some music videos.

Daniel J. Levitin’s lively book, This is Your Brain on Music summarizes the neurological evidence for this firewall in our auditory system. When we listen to music, a great deal happens at very low levels. Meter, pitch, timbre, attack, and loudness are detected, dissected, and reconstructed across many brain areas. The processes runs fast, in parallel, and we have very little voluntary control of them, let alone awareness of them. Of course higher-level processes, like knowledge about the piece, the composer, or the performer, feed into the whole activity. But that’s inevitably running on top of the very fast uptake, disassembly, and reassembly of sensory information. Go here for more information on the book, including some music videos.

So here’s my hunch: A great deal of what contributes to suspense in films derives from low-level, modular processes. They are cognitively impenetrable, and that creates a firewall between them and what we remember from previous viewings.

A suspense film often contains several very gross cues to our perceptual uptake. We get tension-filled music and ominous sound effects, such as low-bass throbbing. We get rapid cutting and swift camera movements. Often the shots are close-ups, as in Notorious‘s wine-cellar scene and during the characters’ final descent of the staircase. Close-ups concentrate our vision on one salient item, creating the attentional focus Carroll emphasizes. The shots are often cut together so fast that we barely have time to register the information in each one.

This isn’t to say that the action itself has to be fast. The action in the Hitchcock scenes isn’t rapid, but its stylistic treatment is. In typical suspense scenes, our “early vision” and “early audition,” biased toward quick pickup, are given rapid-fire bursts of information while our slower, deliberative processes are put on hold. This is happening in the Birth of a Nation assassination scene, as well as in the frantic second half of United 93.

Further, what is shown can push our processing as well. Seeing people’s facial expressions touches off empathy and emotional contagion, perhaps through mirror neurons.

This tendency may explain why we can, momentarily, feel a wisp of empathy for unsympathetic characters. When their expressions show fear, we detect and resonate to that even if we aren’t rooting for them to succeed.

We may also be responding to some very basic scenarios for suspenseful action. Imagine dangling at a great height; “hanging” is the root of the word suspense. Or imagine hurtling toward an obstruction, or being stalked by an animal, or being advanced upon by a looming figure. As prototypes of impending danger, these events may in themselves trigger a minimal feeling of suspense. And such situations are part of filmic storytelling from its earliest years.

Maybe we’re predisposed to find facial expressions and dangerous situations salient because of our evolutionary history, or maybe they’re learned from a very young age. Either way, such responses don’t require much deliberate thinking. They just trigger rapid responses that we can reflect upon later.

Stylistic emphasis and prototype situations surely help the attention-focusing that Carroll discusses. But I’m suggesting something stronger: Many of these cues don’t merely guide our attention to the critical suspense-creating factors in the scene. These cues are arresting and arousing in themselves. They trigger responses that, in the right narrative situation, can generate suspense, regardless of whether we’ve seen the movie before.

Beyond these cues, of course we have to understand the story to some degree. Probably some of the aspects of storytelling that Carroll, Gerrig, and others (including me) have highlighted come into play. As Hitchcock famously pointed out, suspense sometimes depends on telling the viewer more than the character knows. We have to see the bomb under the table that the character doesn’t know about. Suspense is also conjured up by Carroll’s ratio of morality to probability, our real-world understanding of deadlines, and other higher-order aspects of comprehension. In addition, our knowledge of how stories are typically told probably shapes our uptake. We expect suspense to be a part of a film, and so we’re alert for cues that facilitate it.

Involuntary suspense

So I’m hypothesizing that part of the suspense we feel in rewatching a film depends on fast, mandatory, data-driven pickup. That activity responds to the salient information without regard to what we already know.

According to this argument, the sight of Eve Kendall dangling from Mount Rushmore will elicit some degree of suspense no matter how many times you’ve seen North by Northwest, and that feeling will be amplified by the cutting, the close-ups, the music, and so on. Your sensory system can’t help but respond, just as it can’t help seeing equal-length lines in the pictorial illusion. For some part of you, every viewing of a movie is the first viewing.

This tendency may hold good for other emotions than suspense. In the psychological jargon I adopted in Narration in the Fiction Film, experiencing a narrative is likely to be both a bottom-up process and a top-down process. Suspense and other emotional effects in film may depend not only on conceptual judgments about uncertainty, likelihood, and so on. They may also depend on quick and dirty processes of perception that don’t have much access to memory or deliberative thinking.

Film works on our embodied minds, and the “embodied” part includes a wondrous number of fast, involuntary brain activities. This process gives filmmakers enormous power, along with enormous responsibilities.

PS: 9 March. Jason Mittell writes a comment, based on his recent research on TV fans’ attitudes toward spoilers, at his site here. More later, I hope, when I have a chance to assimilate his argument.

By Annie standards

Kristin here—

Way back in 1979, I published a theoretical essay on animation.* It explored how animation is different from live-action because it can mix types of perspective cues within the same image. That was basically the only original idea I have ever had about animation, and I never followed it up by writing more on the subject.

At that point, animation studies were lagging behind film studies in general. A single essay in the area was enough to brand one as an expert. Ever since people have thought of me as an expert on animation. By now, though, animation studies have grown into a healthy area of scholarship, with its own journals and conferences. There are many people studying animation who know far more about it than I. My only work in this area since 1979 has been to write most of the sections on animation in Film Art and Film History.

Still, that leaves me the resident animation expert on this blog, and since I seem to end up writing about the subject occasionally, we’re adding it as a new category as of this entry.

Among the new films I’ve seen in the past couple of years, I find that a significant proportion are animated. I don’t think that’s because I prefer animated films but because these days they are among the best work being created by the mainstream industry.

Why would that be? There are probably a lot of reasons, but let me offer a few.

Animated films, whether executed with CGI or drawings, demand meticulous planning in a way that live-action films don’t. David has written here about directors’ heavy dependence on coverage in contemporary shooting. Coverage means that many filmmakers don’t really know until they get into the editing room how many shots a scene will contain, which angles will be used, when the cuts will come, and other fairly crucial components of the final style. This is true even despite the fact that filmmakers increasingly have storyboarded their films (mainly for big action scenes) or created animatics using relatively simple computer animation.

People planning animated films don’t have the luxury of lots of coverage, and that’s probably a good thing. Storyboards for animated films mean a lot more, because it’s a big deal to depart from them. Every shot and cut has to be thought out in advance, because whole teams of people have to create images that fit together—and they don’t create coverage. There aren’t many directors in Hollywood who think their scenes out that carefully. Steven Spielberg, yes, and maybe a few others.

A similar thing happens with the soundtrack. In animated films, the voices are recorded before the creation of the images. That’s been true since sound was innovated in the late 1920s. Pre-recording means that images of moving lips can be matched to the dialogue far more precisely than if actors watched finished images and tried to speak at exactly the right time to mesh with their characters’ mouths. The lengthy fiddling possible with ADR isn’t an option. Most stars are used to recording their entire performances within a few days, picking up their fees, and moving on to more time-consuming live-action shooting.

[Added December 11: Jason Mittell, who teaches at Middlebury College, has pointed out to me other factors closely related to the thorough storyboarding of animated films and to the pre-recording of dialogue.

Live-action projects often go into the shooting phase with the script still being tinkered with. The main writers are long gone, script doctors have taken over, and stars may request, nay demand, changes in their dialogue. But for animated films the script, like the editing, is in finished form at the move from preproduction to production.

Jason also points out makers of animated films very carefully distinguish the characters by distinctive dialogue and voices. In contrast, do planners of live-action films think much about the combination of vocal tones that the actors will bring to the project? It’s indicative of the difference, I think, that the Annies have a category for best vocal performance and the Oscars don’t. Ian McKellen has been nominated for an Annie in that category for his contribution of the Toad’s dialogue in Flushed Away–completely tailored to the role and totally unrecognizable from his usual voice.

As Jason concludes, “Live-action filmmakers should try to emulate Pixar’s pre-production strategies to raise the quality bar.”]

In The Way Hollywood Tells It and Film Art, David has briefly discussed the modern vogue for muted tones, usually brown and blue, of many modern features. (Remember what a big deal it was when Dick Tracy used bright, comic-book colors in its sets?) The old vibrant tones of the Technicolor days are largely absent, at least from dramas and thriller. Not so in animated films. Most animated films are full of bright colors. (Some tales, like Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride and Happy Feet, call for the elimination of color, but they’re exceptional.) Think of Monsters, Inc. and, say, any David Fincher film, like Se7en. (Yes, Se7en is dark in its subject matter, but I’ve illustrated the two early getting-ready-for-work scenes in each film, before the nastiness starts in Fincher’s film.) For those of us who like some variety in our movie-going, an animated film can be visually pleasing in ways that few other films are.

Makers of animated films aren’t obligated to drag in sex scenes or to undress the lead actress. Maybe such scenes in live-action films really do draw in some viewers, but they can be hokey and definitely slow down the action. (Remember Ben Affleck rubbing animal crackers on Liv Tyler’s bare midriff in Armageddon?) Animated films tend to have romances and sometimes even mildly raunchy innuendo, but it doesn’t slow down the plot. The romances in Flushed Away and Cars are very much like the ones in Hollywood comedies of the 1930 and 1940s, flowing along with the narrative in a more logical way.

live-action films really do draw in some viewers, but they can be hokey and definitely slow down the action. (Remember Ben Affleck rubbing animal crackers on Liv Tyler’s bare midriff in Armageddon?) Animated films tend to have romances and sometimes even mildly raunchy innuendo, but it doesn’t slow down the plot. The romances in Flushed Away and Cars are very much like the ones in Hollywood comedies of the 1930 and 1940s, flowing along with the narrative in a more logical way.

Animated films don’t have to be tailored to the egos and ambitions of their stars to the degree that many live-action features are. Indeed, often stars bring film projects to studios or produce their own films. The growing number of stars providing voices for mice and penguins and spiders don’t have that sort of investment, emotional or financial.

Some of the best directors working today are in animation. Pixar’s John Lasseter hasn’t let us down in any of his Pixar films, whether he personally directs them or supervises others. Nick Park’s shorts and features, especially Creature Comforts and The Wrong Trousers, are the works of a genius, and other director/animators at Aardman aren’t bad either. Then there’s Hayao Miyazaki (Spirited Away, to mention only one). There aren’t many live-action directors working in commercial cinema today with such track records.

Despite all this, studio executives and commentators continue to debate whether there are now too many CGI films coming out. Indeed, the November 24 issue of Screen International says, “Much has been made this year of the seeming over-saturation of studios’computer-generated titles, with critics and analysts pointing to growing movie-goer apathy.” Of course to most people don’t notice any difference between CGI 3D films and those made with claymation (Parks) or puppets (Burton), so SI’s article talks about the successes and failures among the family-friendly animated films of 2006, including 2D Curious George.

This debate over a possible saturation of the market with CGI films seems bizarre. As a proportion among the total number of films made, CGI’s box-office successes seem fairly high compared to live-action films. Yet one doesn’t see execs and pundits mulling over whether audiences are tired of those.

Certainly success or failure isn’t based on quality. Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-rabbit, last year’s winner of the Oscar as Best Animated Feature, was a commercial disappointment (in the U.S., not elsewhere). Monster House got a lot of highly favorable reviews, but similarly had a mediocre reception by ticket-buyers.

This week the nominations for the Annie Awards, given out by the International Animated Film Society, were announced. The Best Animated Feature competition is among Cars, Happy Feet, Monster House, Open Season, and Over the Hedge. But in the “what’s the logic behind that?!” world of awards, Cars and Flushed Away got the highest number of individual nominations, nine each, followed by Over the Hedge with eight.

I’ll confess right now that I’ve only seen three CGI-animated films this year, because, as I say, I’m not an animation specialist. I go to animated films for specific reasons. One, Cars, is a Pixar film. Two, Flushed Away, is an Aardman film. Three, Happy Feet, is directed by George (Road Warrior) Miller.

On the other hand, Over the Hedge was advertised as being “from the creators of Shrek.” Shrek was an entertaining film, but I think it has been overrated. Besides, a check through the main credits of Over the Hedge reveals no one who had worked on Shrek. “Creators” here must mean Dreamworks. That, by itself, is not enough to draw me in.

Of the three I’ve seen, I would rate Cars the best, Flushed Away a not too distant second, and Happy Feet a distinct third. (More about Happy Feet later.) So how come Flushed Away didn’t get nominated for Best Animated Feature?

A cynic might point out that, on a list of the ten highest-grossing animated features of 2006, by year’s end the five nominees will end up among the top six. Ice Age: The Meltdown, currently at number two, received four nominations, but not one for best feature. Flushed Away is at number nine and likely to remain so. I’m sure that’s not the only factor, but as with many other awards nominations, hits tend to maintain a high profile through the year. I suspect that Cars will end up becoming the fourth Pixar film to win the Annie for Best Animated Feature during the seven-year period since Toy Story, the first totally CGI feature, won.

Quality apart, though, why do industry people doubt the wide appeal of CGI animation? Why do they think rising above an indeterminate number of such features per year causes CGI-fatigue among moviegoers? They certainly go on releasing far more live-action films than could possibly all become hits.

As I suggested in my earlier entry on Flushed Away, most of companies releasing animated films don’t know how to market them very well. Let me offer a couple of suggestions as to why everyone but Pixar often seems so clueless.

First, although animated features seem like the ideal family-friendly audience, they’re quite different from the family-friendly live-action film. Every studio wants films that appeal “to all ages” (i.e., to everyone but small kids), preferably with a PG-13 rating. Think Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest, The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, and Titanic, in ascending order the three top international grossers of all time (in unadjusted dollars).

With most animated features, however, there’s a big gap in that family audience: teenagers. Animated films (“cartoons”) are still perceived as largely for children. Sure, savvy filmmakers like the people at Pixar and Aardman are putting more sophisticated references and jokes into their films, things that are more entertaining to adults than to children. The assumption is that parents who take their kids to the movies might be more likely to pick a film if they think they’ll have something to engage their attention, as opposed to sitting tolerantly waiting for the thing to be over.

This, by the way, is another reason why some animated films are among the best products of the mainstream film industry these days. They’ve got a wit and visual sophistication that is sorely lacking in many live-action films. (That’s certainly not true of all of them. I thought Madagascar and the first Ice Age had simple plots that would be engaging mainly to small children.)

So the grown-up humor may please the adults, many of whom, like me, go to them without children in tow. Kids, of course, will watch just about anything animated that’s put in front of them. But suppose a bunch of high-school kids on a Saturday are trying to decide which film to attend. Would any of them nominate Cars or Happy Feet? Maybe I’m behind the times, but I find it hard to imagine. Most teen-agers among themselves, after all, would do anything to avoid seeming not to be grown-up, and watching cartoons is just too childish. (Even the CGI film most obviously aimed at teens, Final Fantasy, was a flop.)

This is not to say that teen-agers don’t see or enjoy Cars and Happy Feet, but I’m guessing they probably go with their families on holidays or see them at home on DVD.

The second big problem that stymies the industry when it comes to promoting animated features is that they usually can’t be branded by director or star, the way “regular” films are. Pixar, as usual, is the exception. John Lassetter is sort of the Steven Spielberg of animation—one of the few directors with wide popular name-recognition. Pixar quickly became a brand in the world of animation, even more than Disney was at that point. Now they’re under the same roof. But Dreamworks really isn’t a high-profile brand, and the newer Sony Pictures Animation certainly isn’t. Their films succeed and become franchises in a hit or miss way. “From the people who brought you Shrek” is a feeble way of branding a film. Mostly I think distributors market animated films to kids and hope the adults will be there, too. Maybe they don’t even think about the teenage audience, considering it a lost cause.

More and more famous actors are doing voices for animated films, but that’s far from the same thing as appearing in a live-action one. Hugh Jackman was a big selling point for the X-Men movies, but who would go to see Flushed Away just because he voices the lead character?

So what can the studios do to integrate CGI and other types of animated films into their flow of regular releases, comparable to live-action films?

One solution is obvious: Make the characters into stars. Disney created the prototype with Mickey Mouse. Buzz Lightyear and Woody would be stars with or without Tim Allen’s and Tom Hanks’s voices. Shrek is a star. Wallace and Gromit are beloved stars outside the U.S. It might have occurred to Paramount to lead up to its release of The Curse of the Were-rabbit by circulating a package of the three earlier shorts, in order to familiarize Americans with the duo. (That was done in European theaters years ago.) Roger Ebert’s review of the feature opined that “Wallace and Gromit are arguably the two most delightful characters in the history of animation.” A pity the American public have not yet been given much of a chance to discover that.

Another possibility is doing what Hollywood is slowly doing for live-action films: Publicize award nominations other than the Oscars. More awards ceremonies are being broadcast on TV as time goes by, and audiences seemingly love these contests. Why not tout an animated film’s garnering of Annie nominations?

Of course companies use Oscar nominations in their ads, but under Academy rules, only three animated features can be nominated in any year unless sixteen or more such features are released that year. Then the number of nominations jumps to five, as has happened only once so far–in 2002, for the 2021 releases. It may become more common, as animated films become more common.

One might object that the general public doesn’t know or care about the Annies. But it’s a vicious circle. They don’t know about them because the industry doesn’t bother to publicize them, and the industry doesn’t publicize them … well, you can see where this is going. If the industry promoted the Annies as signs of quality animation, the public might know and possibly care about them. They’ve learned to be interested in the Golden Globes, because those have been increasingly covered by the infotainment section of the media. And the infotainment industry largely covers the “news” that the industry’s publicity departments want it to (star scandals excepted).

And then there’s the Internet, where fans often do a better job (and for free) of publicizing films than their distributors do. Case in point, Lyz’s WallaceAndGromit.net. I can’t get into online publicity here, or this entry would balloon out of control. Still, there seems an obvious link between people who spend time on the internet and those who are interested in CGI animation.

Epilogue: On Happy Feet (Spoilers!)

I went to Happy Feet with high expectations, based both on reviews and on my liking for previous George Miller films like The Road Warrior and Babe: Pig in the City. I saw it under ideal conditions, in an Imax auditorium.