Archive for the 'Film theory' Category

Kindest, E.: A memoir of Edward Branigan

Equinox Flower (1958).

DB here (but writing for Kristin too):

Edward Branigan died on Saturday, 29 June, in Bellingham, Washington. He had fought for a year against Acute Myeloid Leukemia. He was 74.

Edward was an ambitious, highly original film theorist. His first book, Point of View in the Cinema (1984) has become the definitive study of the creative POV options available within “classical” filmmaking. Narrative Comprehension and Film (1994) is a sweeping account of the viewer’s activity in ascribing meaning to stories on the screen. Projecting a Camera: Language-Games in Film Theory (2006) is a meta-level account of how critics and theorists talk about films; it teases out different capacities and qualities we assign to “the camera.” Edward’s last book, published in December 2017 is Tracking Color in Cinema and Art: Philosophy and Aesthetics. It ranges across physics, psychology, art history, and philosophy (mostly Wittgenstein) to explore how we understand and appreciate color imagery.

Edward was also a prodigious editor, producing with Warren Buckland The Routledge Encyclopedia of Film Theory (2015) and with Chuck Wolfe the American Film Institute Readers, a series of forty anthologies on a huge range of topics. He taught at UCLA and Iowa, but his tenure home was UC–Santa Barbara, where he started in 1984 and remained until retiring in 2012.

Keeping in touch

Edward and Evan Branigan, 1984.

So much for a bare-bones Wikipedia entry; Edward deserves a full-blown one as soon as possible. What even that couldn’t capture is the intense admiration, even devotion, he aroused in students and colleagues. He won many teaching awards, including a Distinguished Service Award from the graduate students of his department. For his peers in the profession he was a reliably easygoing, cheerful presence in the sometimes chilly corridors of academe.

Kristin and I met Edward in 1974, and we kept up with his life (one far more dramatic than ours) as best we could, separated by half a continent. Over the decades we visited him occasionally in Santa Barbara and Los Angeles. For too-few times he returned to Wisconsin for summer vacations. Our last reunion was in September of 2016 at a Seattle coffee house.

My email records before 2004 have gone astray, but after that I count over 400 messages, some very long. I could fill this entry with remarkable passages, and I expect other correspondents have equally plump archives. From 2007:

John [Kurten] and I have had three consecutive movie binge weekends. it’s a treat to start watching films in the afternoon and never think about stopping (more or less for two days at a time) — isn’t this what the profession promised?

He often wrote to correct mistakes I made in books and essays, so getting this reaction to my In the City of Sylvia entry left me elated. (Fortunately for me, he hadn’t seen the film yet.) One sequence perfectly fulfilled the conditions he laid out in his POV book.

You madman, it’s brilliant. Your latest blog. Maybe the film, too. From what you say, I thought of layers and uncertainties, intersections and random slidings. Open expectation or expectation opened. Is *Sylvia* for the point-of-view shot, i.e. for a point in space, what *The Conversation* was for sound, *Blow-up* for the photograph, *Time Regained* for memory, and etc.?

When I discovered a “Hitchcock supercut” compiling favorite motifs and themes, I was reminded that in the pre-digital era Edward had mounted something similar for his course.

Thanks for this link. . . . I did teach Hitchcock a number of times in the mid-to-late 80’s. My final lecture was exactly and precisely as described on the link you sent. All (almost) of Hitchcock’s films were represented on two Kodak Carousel projectors jammed full. I projected two simultaneous images side by side of visual motifs (staircases, camera movements…etc.). Slow dissolves between each pair of images to the next pair. I made a music tape and keyed certain images to climaxes in the music. Only taught the course in the 80’s. Seems an age ago. Not to mention the changes in technology. I have ten metal cases of slides that are orphans now with no projectors. As do you and Chuck [Wolfe] with many more cases. I had some of my slides digitized, but the quality was disappointing.

But later he reports his house fire:

I have realized that my eight cases of 35mm slides taken directly from 16mm prints — collected since 1974 — are gone in the fire, including a slide from every setup of An Autumn Afternoon.

Speaking of Hitchcock, in 2012 I told him that Sir Alfred would have a place in the book I was planning on the 1940s. This got him going:

Mr. missed D.,

Rethinking Hitchcock! I want to read it. . . . Nice to hear from you generally and I trust you and KT to be well. I suspect the latter has seen The Hobbit many a time so far and planning still more viewings. Nicholas and I are in Seattle. This morning after a large breakfast (omelet, steel-cut oatmeal, hash browns, muffins, black tea) I watched out a tenth floor window as the monorail docked at the Space Needle, while visiting my parents and the other Usual Suspects (i.e., relatives), and planning further hiking, movies, bridge, serious eating, shopping ski apparel activities, and so forth. It’s fairly deeply relaxing here. (It suggests what retirement could be for me in Summer 2014, retirement being in name only at the moment.) I saw two float planes land on Lake Union, taxiing to the shore, water spraying up over the floats, red and green lights continually snapping on and off on both wings (i.e., not one red on the left wing, one green on the right wing). Interstate 5 is in the distance, the car headlights of morning commuter traffic turning it into a winding white snake as the day is strongly grayish, clouds about 40 stories up, swirling, banking up, no sign of sky (thus solar panels are useless), the Olympic Mountains are in the distance, people are walking on the streets below this way and that with purpose, with destinations firmly in mind. Have I mentioned the large rotating, neon pink elephant sign glimpsed in the distance between some buildings that advertises simply, “Car Wash,” as if it doesn’t rain often in Seattle? The sign stops briefly on every rotation to shine out its message in white neon bulbs, “Car Wash,” the message never changing. Up here I’m living in a parenthesis. Looking out at a vast aquarium.

He never forgot my birthday. This is from 2014, as is the photo at the bottom.

HB, big guy. Wherever you are, it’s still HB. Thinking of you.

I’m traveling for a month, meeting many persons, hiking above the treeline in the Rockies, World Lacrosse Championships, Denver, Boulder, Fort Collins, Estes Park, The Stanley Hotel (think The Shining), Seattle, northern Wisconsin, seeing all the sons, and more. Consulting on two legal cases. Have no time. Retirement is the bestest. Even trying to write.

From 2018:

I’ve seen Blade Runner 2049 seven times. A masterwork. Been drinking the Blade Runner Director’s Cut Johnnie Walker Black Label Scotch in the film’s Italian crystal glasses. Watched all sixteen episodes of the Netflix series, Babylon Berlin, in three nights. Should interest you in terms of detective fiction. First-rate fun. Weimar seems like hell with all its circles intact. It’s not up to Fassbinder’s Berlin Alexanderplatz, but what is?

During his cancer treatments, he managed to keep corresponding. Although the paragraphs got shorter, the tone never changed. This from May of this year:

I appreciate your generous words and kind thoughts. I haven’t been feeling well. The blasts have been creeping back. . . . More chemo is likely, maybe a clinical trial. . . .

Enemy. The film streams on Netflix. Take a look. Don’t read anything about it, and its shocks, until it settles on you.

Game of Thrones ends tomorrow for all time until the HBO prequel is ready. I think Dany is killed by Ayra disguised as Tyrion. Jon Snow moves the Iron Throne to Westeros with him upon it.

He inevitably signed these energy bursts, “Kindest, E.”

The 70s: Beyond the New Hollywood

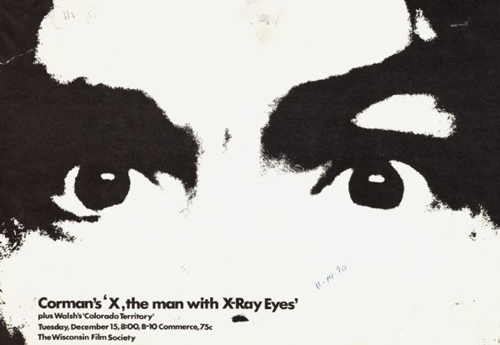

Wisconsin Film Society poster, 1970.

My most vivid memories come from the years we knew him as a student and friend here in Madison. He was part of a thriving intellectual community that, from the distance of today, informed our lives in deep and lasting ways.

Edward, Vietnam veteran (Marines, Communications), took a film course with me in spring 1974, his final year of law school at UW. It was my second semester of full-time teaching. He then signed up for our graduate program. I shouldn’t have been surprised by his shift of career. As an undergraduate he had majored in Electrical Engineering and English. He also wrote poetry.

He entered a community bursting with talent. When I got here in 1973 I was handed four superb TA’s: rigorous and righteous Doug Gomery, witty and charming Brian Rose, meticulous silent-film aficionado Frank Scheide (who looked like a young Buffalo Bill), and already stunning experimental filmmaker James Benning. There was Maureen Turim, fresh from a year in Paris and immersed in Bresson and the avant-garde; Diane Waldman, who’d write the still-definitive account of Hollywood’s female Gothics; Fina Bathrick, who was researching family melodrama before almost anybody else; Marilyn Campbell, the first I think to analyze the Fallen Woman film of the 1930s; Bette Gordon, already at work on her own fine films; and Peter Lehman, already an eloquent advocate for John Ford, Blake Edwards, and Roy Orbison. While everybody else was hot for the new Hollywood, we were into the old one, along with films from beyond the US that later would gain their proper recognition.

Coming in the door were still more gifted grads: Vance Kepley, Janet Staiger, Kerman Eckes, Barb Follick, Barbara Pace, Nancy Ciezki, Diane Kostecke, Mary Beth Haralovich, Cathy Klaprat, Don Kirihara, Darryl Fox, and on and on. I was also establishing ties with young scholars elsewhere: Phil Rosen, Mary Ann Doane, and Bobby Allen at Iowa; Noël Carroll, Paul Arthur, and Tom Gunning at NYU. Networks and enduring friendships were forming. An actual academic field was emerging.

Like every young faculty member, I was learning on the job. I was groping to figure out the problems that interested me most–film form and style, considered in a comparative historical context. The BFI magazine Screen was having a big impact, but so were translations of works by Noël Burch, the Russian Formalists, and French Structuralists. Feminism, neo-Marxism, and Third World politics found their way into our curriculum. Barthes’ S/z became a constant reference point. I went on WORT radio to defend semiotics and The Godfather.

Just as important, American distributors like New Yorker and Audio-Brandon were releasing new European and Latin American titles as well as old works from Asia. In those pre-video days, 16mm prints were our best chance to catch up, not just through classroom showings but through the twenty-plus campus film societies. (There were Sam Fuller double features, but also Godard retrospectives and political documentaries.) And we had The Velvet Light Trap, which published zesty in-depth studies of genres, studios, and auteurs. The campus was movie-mad.

Just as important, American distributors like New Yorker and Audio-Brandon were releasing new European and Latin American titles as well as old works from Asia. In those pre-video days, 16mm prints were our best chance to catch up, not just through classroom showings but through the twenty-plus campus film societies. (There were Sam Fuller double features, but also Godard retrospectives and political documentaries.) And we had The Velvet Light Trap, which published zesty in-depth studies of genres, studios, and auteurs. The campus was movie-mad.

In my seminar on “Classical Hollywood Cinema and Modernist Alternatives,” we analyzed random titles from the Warners and RKO archives alongside Ordet, Equinox Flower, Four Nights of a Dreamer, and Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach. The Student Union screened Play Time in 35 across a whole weekend so my theory class could write essays on it. We brought touring Japanese, French, and Italian film packages to campus.

His Girl Friday, Meet Me in St. Louis, Possessed, Naniwa Elegy, Genroku Chushingura, Tom Tom the Piper’s Son, Death by Hanging, The Man Who Left His Will on Film, The Red and the White, and many other films became touchstones for us. In the midst of all this, senior colleague Tino Balio helped us see how to tie aesthetic analysis to the protocols of national film industries and similar institutions. He became a good friend and ally in many skirmishes, as did Jeannie Thomas Allen, with her work on women and media.

For Kristin and me, the years 1973-1980 crystallized research programs we never left behind. In these years I wrote my Dreyer book, Kristin did her dissertation on Ivan the Terrible, and we published Film Art: An Introduction. With Janet Staiger we began work on what became The Classical Hollywood Cinema. Meanwhile, our students were writing articles for journals and showing up en masse at conferences, a good-natured mafia.

Edward plunged into this and never looked back. He made an offbeat, poetic narrative film (which I hope his family can locate). He ran scenes to and fro on our Steenbecks and analytical projectors, checking match cuts and camera movements. He and Kristin drove down to Chicago for back-to-back screenings of Lancelot du Lac. He began writing on film color, a focus of his research for the next forty years. Above all, we were bound together by Ozu.

Tokyo Story was circulating in 16mm after its smashing New York revival in 1972, and Audio-Brandon and New Yorker acquired several more Ozu titles, early and late. That began our love, or rather mania, for this director. We three watched those prints over and over, eventually writing two essays for Screen in summer of 1976. Edward hoped for a long time to write his doctoral dissertation on An Autumn Afternoon, planning to devote an entire chapter to the woman in the red sweater who passes through scene after scene.

I still want to read that.

Ozu was never far from our thoughts. When Edward finished his dissertation, he gave me a framed still from Equinox Flower. It surmounts this entry. I learned so much from our conversations that I dedicated my Ozu book to him, with a Japanese inscription that means “the pupil who teaches the teacher.” As soon as the book went online, he wrote to tell me of Net problems.

I downloaded the Ozu book. Now, how do I get the color photos and the new crisp b&w’s? Must they be downloaded individually, one at a time? I want them in the book. I want them.

Thanks to his persistent pressure, the University of Michigan created a smoother download.

One constant point of discussion in the 70s was Ozu’s red teakettle in Equinox Flower. When in 2011 Kaurismaki noted it, I sent the link to Edward. He replied:

The red teakettle was a killer for sure. I never really leave the 70s and Vilas Hall… Late nights. 16mm stop motion. I also very much appreciated your blog entry on the four looks at Ozu. Shouldn’t you at some point do a streaming video for your blog?

Sometimes Ozu was merely evoked, not mentioned. One email had this attachment.

Edward knew I would immediately think of a shot from Dragnet Girl and two from Early Summer.

My last email from Edward in May includes this:

Ozu… A year ago I looked at all six of his color films. The color designs are distinctive and sophisticated, but perhaps too complicated to write about. . . .

If he were still with us, I bet he’d try.

Edward’s vitae is available here.

We’re grateful to all those who have shared Edward’s company with us over the years. Vance Kepley helpfully corrected my memory of the 1970s. Thanks especially to Roberta Kimmel and Evan Branigan, who sent us bulletins.

P.S. 9 July 2019: Thanks to Chuck Wolfe, Edward’s tireless colleague at UCSB, for correcting my initial claim about his undergraduate major.

P.S. 12 July 2019: The Film and Media Studies Department at UCSB has posted its tribute to Edward.

Edward Branigan, 1945-2019.

André Bazin, man of the cinema

DB here:

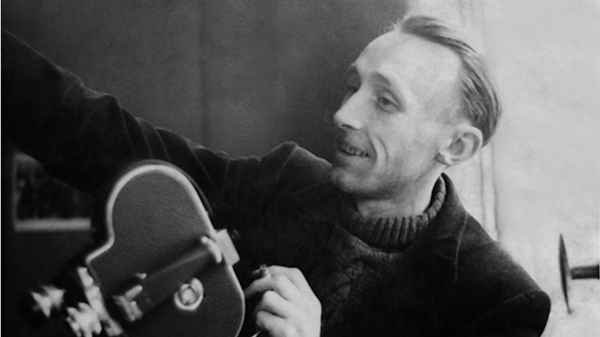

André Bazin was born in 1918 and died on 11 November 1958. In his short life he became, without aiming at it, one of the greatest theorists and critics of cinema.

A central figure in the founding of Cahiers du cinéma, Bazin was also active in building film culture through ciné-clubs and festivals, most notably Cannes and the Festival du film maudit. His writings were poetic, original, and provocative in the gentlest way you can imagine.

As a reviewer he discussed hundreds of releases, and in essay mode he produced subtle reflections on cinema as both medium and art. He wrote about Westerns, pin-ups, Stalinist cinema, documentaries on art and exploration, and of course the commercial storytelling cinemas of France, Italy, and Hollywood. His friendship with two generations of filmmakers–Renoir and Truffaut, among others–gave him a living link to film history. Many would argue that the “young cinemas” of the 1960s, building on both Italian Neorealism and the pictorial styles that crystallized in the 1940s, owe a great deal to the tradition of critical debate he fostered.

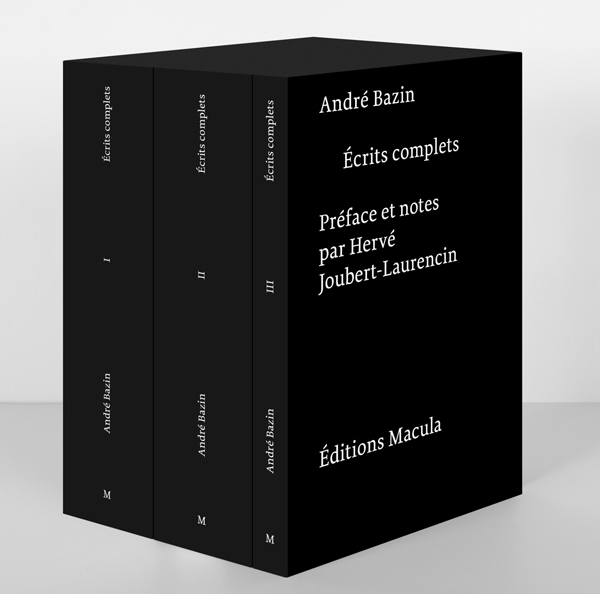

Bazin’s thousands of pieces have now been gathered by Hervé Joubert-Laurencin. A three-volume collection is scheduled to appear this week in a deluxe edition published by Macula of Paris. The press kit, with excerpts, is here.

Beyond reading the work itself, if you want to know more about the man, I think the best place to start is with Dudley Andrew’s biography. It’s a sensitive overview of Bazin’s life and thought, giving particular emphasis to the philosophical and religious influences on him.

Bazin has shaped my thinking about film history and aesthetics since 1967, when I first read Hugh Gray’s translation of What Is Cinema? I taught his work for decades here at Wisconsin, and in On the History of Film Style, I tried to analyze his pivotal role in our understanding of the “development of film language.” That chapter situates his thinking about technique in the context of the “nouvelle critique” of the 1930s and 1940s, a trend that tried to locate an aesthetic suitable for the sound cinema.

Later, I wrote an essay for the German journal montage a/v, which ran a special 2009 issue devoted to Bazin. The original English text, slightly updated, is now available on this site (here, and on the left). That piece suggests how Bazin’s thinking has shaped my own approach to understanding cinema.

Commentators pledged to labels may wonder how a “formalist” like me can find common cause with a “realist” like Bazin. Actually, in both method and substance, his work offers much to the research program I’ve called a poetics of cinema. To see Bazin as being “for” deep-focus and the long take and “against” montage is an oversimplification, it seems to me. He saw more deeply and more widely than that, not least because he was always aware that filmic expression—in style, in narrative—changes across history.

Film criticism owes Bazin an immense debt; he taught us to look closely at what’s onscreen. Elsewhere on this site, we discuss some examples (for example, here and here and here).

There are many ways of thinking about his work, as you can see from the swelling number of articles, books, and conferences devoted to him. He remains a tremendous figure, blending modesty, tolerance, patient attention, close viewing, and bold speculation. Film studies could scarcely exist without him.

Friendly books, books by friends

Moses and Aaron (1974).

DB here:

When the stack of books by friends threatens to topple off my filing cabinet, I know it’s time to flag them for you. I can’t claim to have read every word in them, but (a) we know the authors are trustworthy and scintillating; (b) what I’ve read, I like; (c) the subjects hold immense interest. Then there’s (d): Many are suitable seasonal gifts for the cinephiles in your life (which can include you).

Happy birthday, SMPTE

Starting off in 1916 as the Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, this peerless record of American moving-image technology has gone through many changes of name and format. It’s now The SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. Its back issues have been a treasure house for scholars studying the history of movie technology, and it has outdone itself for its 100th Anniversary Issue, published in August.

Starting off in 1916 as the Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, this peerless record of American moving-image technology has gone through many changes of name and format. It’s now The SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. Its back issues have been a treasure house for scholars studying the history of movie technology, and it has outdone itself for its 100th Anniversary Issue, published in August.

It includes survey articles on the history of film formats, cameras and lenses, recording and storage, workflows, displays, archiving, multichannel sound, and television and video. There’s even an overview of closed-captioning. The issue costs $125 for non-SMPTE members, and it’s worth it. Many libraries subscribe to the journal as well.

A highlight is John Belton’s magisterial “The Last 100 Years of Motion Imaging,” which includes twenty-two pages of dense timelines of innovations in film, TV, and video. They stretch back beyond 1916, to 1904 and the transmission of images by telegraph. John’s article is provocative, suggesting that we might think of digital cinema as returning to film’s origins in handmade images for optical toys.

Lucas predicted that digital postproduction brought film closer to painting, and for more and more filmmakers that prediction is coming true. I was startled to learn that 80% of Gone Girl was digitally enhanced after shooting.

Yes, sir, that’s our BB

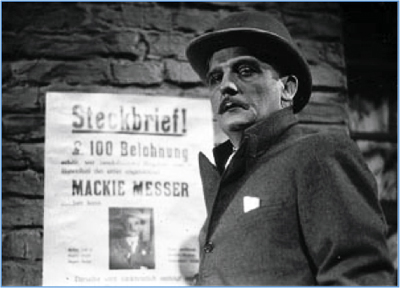

Die 3 Groschen-Oper (1931, G. W. Pabst).

During the 1970s, Bertolt Brecht’s name was everywhere in film studies. He epitomized what an alternative, oppositional, or subversive cinema ought to be. Cinema, even more powerfully than theatre, was a machine for producing illusions. So in his name critics objected to happy endings, plots that tidied up reality, characters with whom we ought to identify, messages that masked the real nature of bourgeois society. Films made all these things seem part of the natural order of things.

The Brechtian antidote was, as people used to say, to “remind people they were watching a film.” This was done by rejecting what he called the Aristotelian model and replacing it with the “alienation effect”: a panoply of distancing devices like intertitles, characters addressing the camera, actors confessing they were actors, and a display of the means of cinematic production (including shots of the camera shooting the scene).

The promise was that once viewers were banished from the imaginary world of the film they would exercise their intellects and coolly appraise not only the fiction machine but its ideological underpinnings. Godard was the chief cinematic surrogate for Brecht, and La Chinoise (1967) became the big prototype of Brechtian cinema—unless you preferred the more austere version incarnated in Straub/Huillet’s Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach (1967) and their adaptation of Othon (1969). The ideas spread fast, helped by the user-friendly Brechtianism of Tout va bien (1972).

The promise was that once viewers were banished from the imaginary world of the film they would exercise their intellects and coolly appraise not only the fiction machine but its ideological underpinnings. Godard was the chief cinematic surrogate for Brecht, and La Chinoise (1967) became the big prototype of Brechtian cinema—unless you preferred the more austere version incarnated in Straub/Huillet’s Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach (1967) and their adaptation of Othon (1969). The ideas spread fast, helped by the user-friendly Brechtianism of Tout va bien (1972).

Brecht became part of Theory. In French literary and theatrical culture of the 1950s, his ideas on staging and performance had claimed the attention of Roland Barthes and other Parisian intellectuals. Godard was alert to the trend early, it seems; he had fun in Contempt (Le mépris, 1963) citing the two BB’s (the other was Brigitte Bardot, bébé), and letting Lang quote a poem by his old collaborator and antagonist. By the time Anglo-American film theorists were ready for semiotics, Brecht was offering support. Didn’t his anti-illusionism chime well with the belief that all sign systems were arbitrary and culturally relative?

My summary is too simple, but then so were many borrowings. Soon enough any highly artificial cinematic presentation might be called “Brechtian,” though usually minus the politics. In the academic realm, Murray Smith’s book Engaging Characters (1995) pointed out crucial weaknesses in the anti-illusionist, anti-empathy account. By then, the certified techniques were becoming part of mainstream cinema. Thereafter, we had Tarantino’s section titles and plenty of movies breaking the fourth wall. Brecht might have enjoyed the irony of using the to-camera confessions of The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) bent to support cynical swindling. Isn’t The Big Short (2015) a sort of Hollywoodized lehrstück (“learning play”)?

Brecht’s writings should be read and studied by every humanist and certainly everybody interested in film. They’re clear, blunt, and often sarcastic.

This beloved “human interest” of theirs, this How (usually dignified by the word “eternal,” like some indelible dye) applied to the Othellos (my wife belongs to me!), the Hamlets (better sleep on it!), the Macbeths (I’m destined for higher things!), etc.

Now Marc Silberman, our colleague here at Madison, has completed a trio of books that make the master’s work available. Bertolt Brecht on Film and Radio includes essays, scripts, and the Threepenny Opera lawsuit brief. There’s also Brecht on Performance and a complete revision of that trusty black-and-yellow volume dear to many grad students: Brecht on Theatre. The latter two collections Marc worked on with collaborators. All are indispensible to a cinephile’s education. As Brecht imagined a bold political version of music he called misuc; can we imagine a cenima?

From BB to S/H

Speaking of Straub and Huillet, every decade or so somebody comes out with a book about them. This time we have to thank the admirable Ted Fendt, in the twenty-sixth volume in the series sponsored by the Austrian Film Museum (as well as the Goethe Institute and Synema). Like the Hou Hsiao-hsien volume (reviewed here), Jean-Marie Straub & Danièle Huillet is fat and full of ideas and information.

There are interviews, tributes from filmmakers (Gianvito, Farocki, Gorin), and Fendt’s account of distribution and reception of their films in the Anglophone world. This last includes charming facsimile correspondence, with one Huillet letter pockmarked by faulty typewritten o’s. As you’d expect, she is objecting to making a 16mm print of Moses and Aaron (1974) from the 35. (“No, definitively.”)

There are interviews, tributes from filmmakers (Gianvito, Farocki, Gorin), and Fendt’s account of distribution and reception of their films in the Anglophone world. This last includes charming facsimile correspondence, with one Huillet letter pockmarked by faulty typewritten o’s. As you’d expect, she is objecting to making a 16mm print of Moses and Aaron (1974) from the 35. (“No, definitively.”)

Starting things off is a lively and comprehensive survey of the duo’s careers by Claudia Pummer, with welcome emphasis on production circumstances and directorial strategies. The book wraps with a detailed thirty-page filmography and a substantial bibliography.

My thoughts about S/H are tied up with their earliest work, when I first learned of them. So I loved, and still love, Not Reconciled (1965) and The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach. I also have a fondness for Moses and Aaron, Class Relations (1983), From Today until Tomorrow (1996), and Sicilia! (1998). I find others out of my reach, and several others I haven’t yet seen. People I respect find all their work stimulating, so I suspect it’s really a matter of gaps in my taste.

Whether you like them or not, they’re of tremendous historical importance. Without them, Jim Jarmusch and Béla Tarr, and of course Pedro Costa and Lav Diaz, would not have accomplished what they have. And especially in December 2016, we ought to find their unyielding ferocity inspiring. Remember them on Dreyer: “Any society that would not let him make his Jesus film is not worth a frog’s fart.” Brecht would have approved.

Stone’d

To the minimalism of Straub and Huillet we can counterpoint the maximalism of Oliver Stone, the most aggressive tabloid American director since Samuel Fuller (although Rococo-period Tony Scott gives him some competition). After two books on Wes Anderson, Matt Zoller Seitz has brought us a booklike slab as impossible as the man’s films. Can you pick it up? Just barely. Can you read it? Well, probably not on your lap; better have a table nearby. Does its design mirror the maniacal scattershot energy of films like JFK (1991), Natural Born Killers (1994), and U-Turn (1997)? Watch the title propel itself off the cover.

The Oliver Stone Experience is basically a long interview, sandwiched in among luxurious photos, script extracts, correspondence, and the sort of insider memorabilia that Matt has a genius for finding. We get not only pictures of Stone with family and friends, on the set, and relaxing; there are bubblegum cards from the 40s, collages of posters and filming notes, maps, footnotes, and shards of texts slicing in from every which way. Newspapers, ads, and production documents are scissored into the format, including a Bob Dole letter fundraising on the basis of the naughtiness of Natural Born Killers. Beautiful frame enlargements pay homage to the split-diopter framings of Born on the Fourth of July (1989) and the shadow of the 9/11 plane sliding up a facade in World Trade Center (2006). When Stone had second thoughts about things he’d said, Matt had the good idea of redacting the interview like a CIA file scoured with thick black lines.

The Oliver Stone Experience is basically a long interview, sandwiched in among luxurious photos, script extracts, correspondence, and the sort of insider memorabilia that Matt has a genius for finding. We get not only pictures of Stone with family and friends, on the set, and relaxing; there are bubblegum cards from the 40s, collages of posters and filming notes, maps, footnotes, and shards of texts slicing in from every which way. Newspapers, ads, and production documents are scissored into the format, including a Bob Dole letter fundraising on the basis of the naughtiness of Natural Born Killers. Beautiful frame enlargements pay homage to the split-diopter framings of Born on the Fourth of July (1989) and the shadow of the 9/11 plane sliding up a facade in World Trade Center (2006). When Stone had second thoughts about things he’d said, Matt had the good idea of redacting the interview like a CIA file scoured with thick black lines.

The whole thing comes at you in a headlong rush. Amid the pictorial churn and several essays by other deft hands, we plunge into and out of that stellar interview, mixing biography and filmmaking nuts-and-bolts. Matt gets deep into technical matters, such as Stone’s penchant for rough-hewn editing, as well as raising some big ideas about myth and autobiography. There are occasional quarrels between interviewer and interviewee. Out of the blue we get remarks like “Alexander was not only bisexual, he was trisexual,” which was not redacted.

The book’s very excess helps make the case for Stone’s idiosyncratic vision. Matt’s connecting essays, along with the vast visual archive he’s scavenged and mashed up, made me want to rethink my attitude toward this overweening, sometimes crass, sometimes inspired filmmaker. He now seems a quintessential 80s-90s figure, as much a part of the era as Reagan, Bush, and Clinton. Stone emerges as a resourceful defender of The Oliver Stone Experience, articulating a radical political critique with gonzo verve.

Rhapsody in white

If lifting the Book of Stone doesn’t suffice for exercise, try another weighty and sumptuous item, King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman’s Technicolor Revue, by James Layton and David Pierce. Last spring the Museum of Modern Art premiered one of the most ravishing restorations I’ve ever seen, a digital version of King of Jazz (1930).

If lifting the Book of Stone doesn’t suffice for exercise, try another weighty and sumptuous item, King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman’s Technicolor Revue, by James Layton and David Pierce. Last spring the Museum of Modern Art premiered one of the most ravishing restorations I’ve ever seen, a digital version of King of Jazz (1930).

This period piece is in its own way as wild as an Oliver Stone movie. From its opening cartoon of Paul himself as a Great White Hunter bagging a lion, it’s a virtually self-parodying account of how a black musical tradition got netted, trussed up, and caged for the swaying delectation of white audiences. (No need to mention the irony of the name of our King.)

Along the way we have some straight-up songs (including some by Bing Crosby) spread among extravagant dance numbers. The Universal crane gets a workout as well. The music is infectious, the performers sweating to please, and the restoration–coming, I hope, to your screen soon–finally shows what two-color Technicolor could do. This is the definitive version of a film too often known in cut versions with shabby visuals and sound.

The book is an in-depth contextualization of the film, the studio, and the tradition of musical revues, both on stage and in film. It records the production and reception, with rich documentation throughout. The story of assembling the restoration is there too, and it’s a saga in itself. David is one of the moving spirits behind the online Media History Digital Library and its gateway Lantern. James is Manager of the Celeste Bartos Film Preservation Center at the Museum of Modern Art. Their collaboration has given us both a lush picture book and a serious, always enjoyable piece of scholarship. Their book proves the value of crowdsourcing: funded by online subscription, it was self-published. In this and much else, it can be a model for film historians pursuing questions that commercial and university presses might find too specialized. The result is a model of ambitious research, writing, and publishing.

Visiting Radio Ranch

Gene Autry in The Phantom Empire (1935).

For about thirty years I’ve been arguing that one fruitful research program in film studies involves what I call a poetics of cinema: the study of how, under particular historical conditions, films are made to achieve certain effects. This program coaxes the researcher to analyze form and style, study changing norms of production and reception, and consider how filmmakers work in their institutions and creative communities, with special focus on craft routines, work methods, and tacit theories about the ways to make a movie.

A sturdy example of this approach has appeared from Scott Higgins. His Matinee Melodrama fulfills the promise of its subtitle: Playing with Formula in the Sound Serial. Scott has closely examined this widely despised genre, plunging into the 200 “chapterplays” produced in America between 1930 and 1956. They offer bald and bold display of the rudiments of action-based storytelling: “If Hitchcock built cathedrals of suspense from fine brickwork of intersecting subjectivities and formal manipulations, sound serials used Tinkertoys.”

A sturdy example of this approach has appeared from Scott Higgins. His Matinee Melodrama fulfills the promise of its subtitle: Playing with Formula in the Sound Serial. Scott has closely examined this widely despised genre, plunging into the 200 “chapterplays” produced in America between 1930 and 1956. They offer bald and bold display of the rudiments of action-based storytelling: “If Hitchcock built cathedrals of suspense from fine brickwork of intersecting subjectivities and formal manipulations, sound serials used Tinkertoys.”

Scott traces production practices and conventions, focusing in particular on two dimensions. First, to a surprising degree, serials rely on the conventions of classic stage melodrama, such as coincidence and more or less gratuitous spectacle. Second, the serials are playful, even knowing. Like video games, they invite viewers to imagine preposterous narrative possibilities, not only in the imagination but also on the playground, where kids could mimic what they saw Flash Gordon or Gene Autry do.

Matinee Melodrama investigates the implications of these dimensions for narrative architecture, visual style, and the film and television of our day. Scott closes with analysis of the James Bond series, the self-conscious mimicking of serial conventions in the Indiana Jones blockbusters, and the Bourne saga, and he shows how they amp up the older conventions. “Like the contemporary action film generally, the Bourne movies participate in a cinematic practice vigorously constituted by studio-era serials. That is, they blend melodrama with forceful articulations of physical procedure in scenes of pursuit, entrapment and confrontation.”

Poetics, frank or stealthy

The Red Detachment of Women (1971).

Scott’s book acknowledges the poetics research program, and so, even more explicitly, does a new collection edited by Gary Bettinson and James Udden. The Poetics of Chinese Cinema gathers several essays that usefully test and stretch that frame of reference.

One standard challenge to the poetics approach is: How do you handle social, cultural, and political factors that impinge on film? I think the best way to answer this is to treat these factors as causal influences on a film’s production and reception. More specifically, in the production process, what we now call memes function as materials—subjects, themes, stereotypes, and common ideas circulating in the culture or the filmmaking institution. In the reception process, they provide conceptual structures that viewers can use in making their own sense of the films that they’re given. And such materials will necessarily include other art forms; films are constantly adapting and borrowing from literature, drama, and other media.

Both of these possibilities are vigorously explored in several essays in The Poetics of Chinese Cinema. For instance, Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh traces how Taiwanese and Japanese cultural materials are reworked by Hou Hsiao-hsien in his Ozu homage Café Lumière (2003). Peter Rist, a long-time student of Chinese painting, shows how Chen Kaige deploys cinematic means to revise landscape traditions to create a “Contemplative Modernism.” Victor Fan shows how the Hong Kong classic In the Face of Demolition (1960) adapts and revises a mode of narration already established in Cantonese theatre. In a clever piece called “Can Poetics Break Bricks?” Song Hwee Lim considers how digital technology feeds into a poetics of spectacle, specifically around slow-motion techniques that were emerging in pre-digital filmmaking.

Both of these possibilities are vigorously explored in several essays in The Poetics of Chinese Cinema. For instance, Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh traces how Taiwanese and Japanese cultural materials are reworked by Hou Hsiao-hsien in his Ozu homage Café Lumière (2003). Peter Rist, a long-time student of Chinese painting, shows how Chen Kaige deploys cinematic means to revise landscape traditions to create a “Contemplative Modernism.” Victor Fan shows how the Hong Kong classic In the Face of Demolition (1960) adapts and revises a mode of narration already established in Cantonese theatre. In a clever piece called “Can Poetics Break Bricks?” Song Hwee Lim considers how digital technology feeds into a poetics of spectacle, specifically around slow-motion techniques that were emerging in pre-digital filmmaking.

Tradition is a key concept in poetics, and the editors explore important ones in their own contributions. Gary Bettinson studies the emergence of Hong Kong puzzle films in works like Mad Detective (2007) and Wu Xia (2011). Are they simple imitation of Hollywood, or are they doing something different? Gary shows them to have complicated ties to local traditions of storytelling. Jim Udden focuses more on stylistics in his account of Fei Mu’s 1948 classic Spring in a Small Town, remade by Tian Zhuangzhuang in 2002. By examining staging, cutting, and voice-over, Jim shows that the earlier film is in many ways more “modern” than it’s usually thought and is somewhat more experimental than the remake.

It might seem that the “model” operas and plays of the Cultural Revolution, epitomized in The Red Detachment of Women (1971) would resist an aesthetic analysis; they’re determined, top-down fashion, by strict canons of political messaging. But Chris Berry’s contribution shows that they’re amenable to close analysis too. Like Soviet Socialist Realism, they may be programmatic in meaning, but not in every choice about framing, performance, cutting, and music. Indeed, the fact that people both inside and outside China (me included) still find them pleasurable probably owes something to their “Red Poetics.” And in true Hong Kong fashion, many filmmakers in that territory plundered those soundtracks with shameless, drop-the-needle panache.

I should probably add that I have an essay in this collection too. It’s called “Five Lessons from Stealth Poetics,” and it surveys things I’ve learned from studying cinema of the “three Chinas”: Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the Mainland. What attracted me were the films themselves, but in exploring them I was obliged to nuance and stretch the poetics approach. Readers of this blog know the trick: in talking about particular movies, I also try to show the virtues of the approach I favor. In other words, stealth poetics.

This is a good moment to pay tribute to Alexander Horwath, moving into his final nine or so months of directing the Austrian Film Museum. He has been a major figure in European film culture, through his inspired programming and leadership in publishing the books and DVDs issued by the Museum. We’re very grateful for all he has done for us and for film historians around the world.

P.S. 11 December 2016: Thanks to Mike Grost for a title correction and John Belton for a name correction!

King of Jazz (1930).

You and me and every frog we know

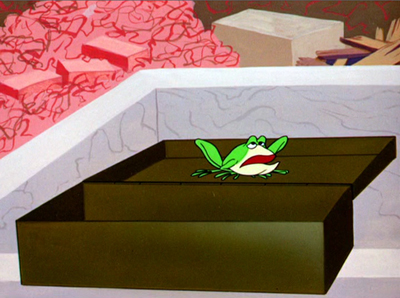

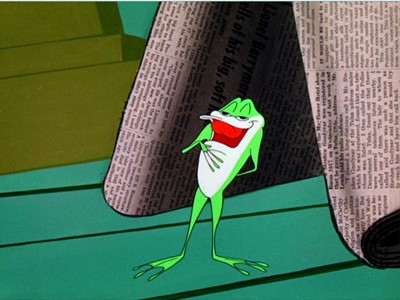

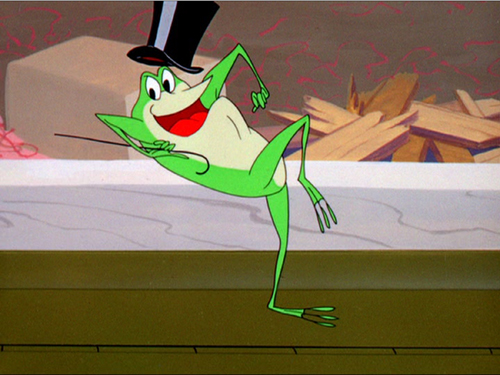

Frog TV (2014, N. Joe Myers).

DB here:

Be patient, the frogs are coming. But first, a bit of film theory.

Movies in code

Once many film scholars were captivated by the idea that our responses to a movie were coded, we might say, all the way down.

Here, code means something like a way of assigning meaning that is both arbitrary and relative to time and place. The code is arbitrary in that it might just as easily have been otherwise. A code is relative because in different circumstances it might vary.

One prototype for the early semiologists was the code regulating traffic. In a traffic light, there is no natural or necessary connection between green and “Go!” or red and “Stop!” We’ve just agreed on these meanings. We could have assigned red to “Go!” and green to “Stop!” And indeed other cultures might do just that. A gesture may mean something friendly in one culture and something naughty in another.

The presumption is that because a code is both arbitrary and relative, it has to be learned. You need to live in a culture to understand the traffic code and the code of gestures. Through either observation or training (such as learning the codes of written language) you master the codes of your culture.

Clearly, movies include many codes. A film can show us traffic lights or hand gestures. Films include language as well, which is coded to a high degree. The crucial question is: How much in our responses to film is coded?

Almost everything, some said. There was a wing of semiology ca. 1970 that suggested that both what’s represented in film and the ways things are represented are arbitrary and culturally variable in the extreme. Some theorists suggested that just recognizing an object in a shot relies not on natural perception but rather on a code. Indeed, the argument was made that “natural” perception is itself coded. A favorite corollary of this was that language was such a powerful code that it reshaped perception. Put bluntly, if your culture’s language doesn’t distinguish red from green, you won’t see the traffic light’s top and bottom lamps as different colors.

I resemble that remark; or do I?

Surely, somebody will say, many film images resemble the things they portray. A shot of a man and a woman looks, in certain relevant respects, like a man and a woman. We’re able to recognize them as such. Yet 70s semiology held that there was nothing natural about this. The image-object resemblance, often called “analogy,” and “iconicity,” was considered to be coded.

Here, for instance, is Umberto Eco in 1967:

We know that it is necessary to be trained to recognize the photographic image. . . . Even if there is a causal link with the real phenomena, the graphic images formed can be considered as wholly arbitrary.

Christian Metz brings out the cultural variability of recognition in a 1970 essay:

The apprehension of a resemblance implies an entire construction whose modalities vary notably down through history, or from one society to another. In this sense the analogy is, itself, codified.

Here is Dudley Andrew commenting on this line of thought in 1984:

The discovery that resemblance is coded and therefore learned was a tremendous and hard-won victory for semiotics over those upholding a notion of naive perception in cinema.

The semiological tradition pointed out, correctly I believe, that the parallel between the image and the thing it represents lies not in some relation between the two but in the comparable ways in which we understand each one. But can this process be considered both arbitrary and relative?

Can we, for instance, imagine a culture in which recognition was fundamentally arbitrary—where a picture of a bunch of bananas depicts, by cultural fiat, a clutch of cherries? More exactly, where a picture of a bunch of bananas is seen as a clutch of cherries?

We can imagine a very capricious filmmaker who set up a code with an introductory credit:

Every time I show you a shot of bananas, see cherries.

But you couldn’t see cherries. At best, the result would involve imagination, not perception. Even cooperative spectators would recognize the bananas as bananas, though they would go on to think of cherries.

The distinction between perception and thought seems to have been blurred in semiological theory. Perhaps the 70s arguments traded on the various meanings of “perception”, such as “I perceive that he’s unhappy today” or “I want to change your perception of Rosicrucianism.” The same would go for various senses of “recognition”: “I recognize the father’s face in the son,” “He had aged so much I didn’t recognize him.” These senses of the word bring in matters of conception and attitude, not just visual input.

Perception and evolution

Not that perception is easy to define. When the semiologists were writing, they may have been influenced by psychological theories that assigned a big role to concepts in perception—“top-down” models that claimed perception to be “cognitively penetrable.” It’s fair to say that there’s now good evidence that the perceptual activities involved in visual recognition are largely fast, automatic, fairly dumb, and cognitively impenetrable.

Another error, it seems to me, was also the product of the period: the ignoral of evolution. The 1970s advocates of sociobiology seem to have been simply ignored, perhaps because they seemed to be naïvely attempting to see culture as nature. Yet I think that J. J. Gibson was right (also in the 1970s) in proposing that evolutionary theories could help explain why perceptual recognition is so swift and efficient.

Creatures evolved in an environment that selected for accurate perception, including very very very fast recognition of predators, prey, and mates. Evolution, we might say, provided long-term survival training in recognition, weeding out any creatures who didn’t register salient features of their world. A hominid who needed explicit teaching to recognize a tiger wouldn’t last as long as one who came to the task with senses pre-tuned. As with learning spoken language, all that would be needed is some exposure to the regularities of the ancestral environment. The baby born into our world is bombarded with redundant information that is non-arbitrary and non-relative; she quickly grasps that a face is more informative than a knee. It will take her quite a bit more time, along with some tutelage, to learn traffic signals and even more to learn to read.

Cinema taps some of our most fundamental capacities. Film images aren’t reality, but they present certain salient triggers for us to recognize what they represent. Indeed, the very perception of motion in movies is an illusion—a glitch in our visual system that cannot be arbitrary or culturally relative. Nobody in any time or place sees movies for what they are, a succession of still images. There are enough cues for movement to fool everybody’s visual system. And films preserve enough other features of the world to trigger automatic recognition processes. Perceptual recognition of something in the image is on the whole neither arbitrary nor culturally variable.

The likeliest conclusion is that we share with other creatures some native propensities which, given the right early exposure to the physical and social world, will be exercised in comparable ways. Of course there are differences. Minnows can’t enjoy Matisse, and we can’t smell as well as dogs can. Still, sensory systems overlap among many species.

So consider the frogs of the field: they toil not, neither do they spin.

Frogs like the front row too

We know quite a bit about how frogs see the world. A classic paper in animal neurology, “What the Frog’s Eye Tells the Frog’s Brain,” was crucial in suggesting the highly specialized nature of nerve fibers feeding information to the visual system. Those data streams—about edges, movement, and variable illumination—get reintegrated, but not necessarily thanks to high-level mental activity. “Early vision,” in frogs and in us, involves not some some brainy entity interpreting the image on the retina but rather several specialized, quite stupid systems that pool information before thought ever enters the picture. No codes necessary. What came to be called “distributed processing” does a large share of the job.

Though untrained in the codes of our culture, these frogs appear to recognize what matters to them, even on the mini-movie screen. (Sorry the video embed no longer works.)

If pigeons can quickly learn to interpret human faces in pictures, and female jumping spiders react to video images of males as if they were real, we shouldn’t be surprised that frogs can respond very—ah—actively on first exposure to movies showing things they really care about.

Of course a lot of our activity isn’t as data-driven and mandatory as recognition. Higher-level concepts do all sorts of work when we watch movies, from understanding who the protagonist is to grasping a film’s theme or point. And of course all manner of conventions in films require sophisticated cultural knowledge. My point is just that some aspects of our response are very basic. I hazard that our responses to cinema mix together all kinds of skills, abilities, biases, and proclivities. A movie is a package of appeals, a buffet with something for all our visual and auditory appetites.

First, thanks must go to N. Joe Myers, who posted this neat experiment in natural perception a year ago. (Has the filmmaker tried it with an iPad or a computer monitor that would make the worms look huge? Would that induce large-scale frog panic?) For vastly more frog-related information, go to N. Joe’s page here.

Thanks also to Darlene Bordwell, who called the piece to my attention, and Barb Anderson who pointed me to the spider studies. The illustrations are of course from Chuck Jones’ Warner Bros. cartoon One Froggy Evening (1955).

My quotations are from Umberto Eco, “Articulations of the Cinematic Code,” and Christian Metz, “On the Notion of Cinematographic Language,” both in in Movies and Methods, ed. Bill Nichols (University of California Press, 1976), 594 and 584; and Dudley Andrew, Concepts in Film Theory (Oxford University Press, 1984), 25. See also Metz, “Au-delà de l’analogie, l’image (1969),” Essais sur la signification au cinéma, vol. II (Klincksieck, 1972): “Resemblance itself is codified, because it makes appeal to a judgment of resemblance: the judgment of an image’s degree of resemblance will vary according to the time and place” (154).

J. J. Gibson’s writings mounted a strong case for what he called “direct perception” in The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception (Houghton Mifflin, 1979). His ideas were developed by Claire F. Michaels and Claudia Carello in Direct Perception (Prentice-Hall, 1981) and, more critically, by James Cutting in Perception with an Eye for Motion (MIT Press, 1986); pdf. Joseph Anderson’s The Reality of Illusion: An Ecological Approach to Cognitive Film Theory (University of Southern Illinois Press, 1998) is the trailblazing application of Gibson’s ideas to cinema. More generally, Paul Messaris’ Visual Literacy: Image, Mind and Reality (Westview, 1994) reviews the empirical findings that show virtually no cultural variability in perceiving line drawings and photographic images as depictions of recognizable persons, places, and things.

At some point in discussions of the cultural variability of perception, someone is likely to mention Eskimo cultures’ purported range of words for snow. But this is a long-standing error. See Geoffrey K. Pullum’s The Great Eskimo Vocabulary Hoax and Other Irreverent Essays on the Study of Language (University of Chicago Press, 1991) and John H. McWhorter’s The Language Hoax: Why the World Looks the Same in Any Language (Oxford, 2014).

What happened to these 1970s beliefs about the film image’s coded nature? It seems to me that when semiology as a research perspective waned, academics mostly stopped talking about the issue of resemblance and recognition. Researchers retained a general sense that films are coded, but they concentrated on less controversial conventions, like social stereotyping, representations of power, and so on. I’ve been told that the level of perception is merely a matter of “physiology” (wrong word) and thus of no consequence for the important issues that scholars should be studying. But of course filmmakers shape our response chiefly by controlling our perception, and if we want a comprehensive account of how films work and work on us, we can’t ignore this level of the viewer’s activity. I consider this problem in the title essay of Poetics of Cinema.

For a more developed argument about how films bundle a range of appeals, from sensory triggors to high-level concepts, see my essay, “Convention, Construction, and Cinematic Vision” in Poetics of Cinema. Online, I discuss these matters here and here and here (under “Representational Relativism,” which involves not frogs but our ancient ancestors).

P.S. 21 September 2015: Apes appear to remember episodes after watching movies. Thanks to Bill Evans.

One Froggy Evening.