Archive for the 'FilmStruck' Category

Fassbinder’s figures: Jeff Smith on ALI: FEAR EATS THE SOUL

DB here:

Normally our co-conspirator Jeff Smith would be guest-blogging to fill in background on his new installment on the Criterion Channel. That entry is devoted to Fassbinder’s great social melodrama Ali: Fear Eats the Soul. But Jeff is ramping up for the start of a semester, and we’re hustling to get ready for a trip, so let this notice do duty.

In this month’s entry, Jeff digs deep into Fassbinder’s directorial style and shows how it connects to the film’s portrayal of bigotry–ethnic, racial, age-related. Since at least Katzelmacher (1969), and right up to Querelle (1982), Fassbinder was constantly experimenting with performance and staging. Ali is one of his triumphs. Jeff is especially acute, I think, in showing how before-and-after parallels in the drama emerge from shrewd repetitions of compositions and mise-en-scene. Thanks to the boffins at Criterion, these become crystal-clear through judicious split-screen.

Jeff’s entry is one of our very best, and we hope subscribers to FilmStruck and the Criterion Channel will enjoy it. The transfer is very pretty too. Coming up in future months: entries on M, The Phantom Carriage, Brute Force, and Chungking Express.

As for Kristin and me, we’re off to the Venice International Film Festival. Peter Cowie has kindly invited me to be on the panel devoted to discussing the projects in the Biennale College Cinema 2017. From the press release:

“The thirteen feature films already produced and screened during the first four years of the Biennale College Cinema program have met with acclaim throughout the world. Produced on an ultra-modest budget, each of them showed an unusual talent and an innate gift for filmmaking,” notes moderator Peter Cowie (film historian and former Int’l Publishing Director of Variety). “The Biennale College Cinema scheme is exciting chiefly because it is in essence a workshop – a workshop and laboratory that places the focus squarely on two essential themes: the making of low-budget films in a period of global recession, and the need to find youthful auteurs if the cinema is to be reinvigorated.” The laboratory was created by the Biennale di Venezia in 2012 and is open to young filmmakers from all over the world.

This is very exciting. And while we’re in Venice, we hope to reconnect to old friend Mark Johnson (producer of innumerable outstanding films, including Rain Man, Logan Lucky, and Galaxy Quest) and newer friend Alexander Payne. They’re arriving with Downsizing. Many other major films will be there, and we hope to report on some of them here over the next two weeks. And then there’s some scary Virtual Reality….

Thanks as ever to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and all their teammates at Criterion. A complete list of the Observations on Film Art series (ten already!) is here.

Videos of earlier Biennale College Cinema panels can be found here. Glenn Kenny discusses last year’s event on RogerEbert.com.

Our own efforts at split-screen analysis yielded a comparison of the murder and its replay in Mildred Pierce. You can see that here, and the accompanying blog entry here.

Ali: Fear Eats the Soul.

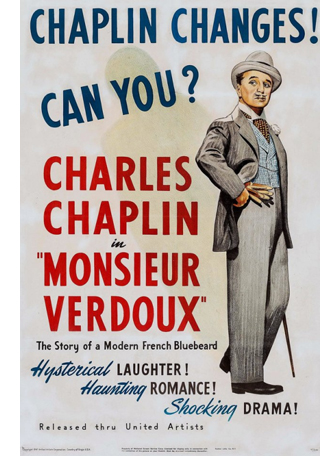

MONSIEUR VERDOUX: Lethal Lothario

DB here:

The newest installment of our Criterion Channel series on FilmStruck is now up. There I try to look at Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux (1947) from a fresh perspective: as a perverse contribution to the serial-killer cycle of the 1940s. You can sample it on the Criterion blog.

The killers inside them

When we say that we take up a new perspective on a film, or any artwork, what are we doing? I think the process involves at least two things. First, you need categories, some fresh conceptual groupings that allow for a perspective shift. Second, you relate the film in question to other particular films—that is, you pick prototypes of the categories. People don’t realize, I believe, the extent to which picking prototypes shapes our reasoning about nearly everything. (Is your prototype of a horror film Cat People, Halloween, or Saw? You’ll think of the genre differently.)

Take film noir. The category didn’t exist in 1940s Hollywood; no producer or director or writer set out to make a noir. A film might be a thriller, crime melodrama, even a horror movie. I discuss the elasticity of these categories here. When French, then American critics started talking about film noir, they were creating a perspective shift. The new category “film noir” pulled together several aspects of films that hadn’t seemed so salient in their day: skepticism about orthodox authority, for example, or suspicion of women’s sexuality. Similarly, the critics elevated certain films, like Double Indemnity and The Big Sleep and Possessed, to the status of prototypes, and less vivid examples were situated in relation to them.

Something like this perspective shift occurred to me when I was writing my book, Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. I tried to come up with some categories that could show continuity and change in film narrative of the period. I looked for strategies of plotting and narration that cut across received categories like genre. Among the categories I explored are block construction, multiple-protagonist plots, subjective viewpoint, non-chronological story sequence, voice-over narration, and others. Some had come to be associated with certain genres (thanks again to prototypes), but I found that they were quite pervasive. Several of these I’ve tried out on the blog.

Once I was peering through the lenses of these categories, my prototypes changed too. Now little-discussed films like Our Town (1940) and Tales of Manhattan (1942) and The Human Comedy (1943) and The Chase (1946) became surprisingly central. I couldn’t ignore the classics, but they were now lit by a crosslight that brought out fresh aspects. And with these categories of narrative technique in mind, we can discover some new sides of well-known auteurs, like Welles, Hitchcock, Sturges, and Mankiewicz.

One broader category I tried out was that of “murder culture.” Mystery and suspense are perennial narrative appeals, but they took on new power in in fiction, film, and theatre of the Forties. (An early version of the chapter’s case is made here.) Part of murder culture was the rise of the serial-killer tale—not new in the 1940s, of course, but more common than in earlier Hollywood eras. Films like Shadow of a Doubt (1943), The Lodger (1944), Bluebeard (1944), Hangover Square (1945), Lured (1947), Follow Me Quietly (1949), and others became prototypes for my purposes.

Then Monsieur Verdoux appeared in a new light. What better evidence of the pervasiveness of murder culture than the effort by the most-loved film star in history to play a serial killer?

Landru in LA

Orson Welles and Charles Chaplin, Brown Derby restaurant, March 1947.

It was Orson Welles who prompted Chaplin to make Monsieur Verdoux. Welles was a thriller fan. He carried a trunkload of crime novels around on his travels. One of his early RKO projects was an adaptation of Nicholas Blake’s Smiler with a Knife, and after the debacle of It’s All True, his work as a freelance director consisted of thrillers (The Stranger, The Lady from Shanghai, Mr. Arkadin) and Shakespeare adaptations (Macbeth, Othello). Indeed, he treated Shakespeare’s plots as thrillers, in accord with his belief that the Bard wrote not classical tragedies but blood-and-thunder melodramas.

According to biographers, Welles wrote a screenplay based on the wife-murderer Landru and offered the role to Chaplin. Chaplin at first accepted, then decided to direct the film himself and bought the idea from Welles. There was apparently some dispute about giving Welles credit; early prints are said to have lacked acknowledgment of Welles’ idea as the source.

By late 1941, the trade press reported that Chaplin was preparing the film, then called “Lady Killer.” A year later, it was still discussed as a “plan.” Chaplin didn’t finish the screenplay until 1946, and the film was shot between May and September. By then it was entitled “A Comedy of Murders,” although Chaplin toyed with “Bluebeard” and “Bluebeard Rhapsody.” It wasn’t released until spring of 1947.

This long gestation period is significant because when Chaplin started, the idea of a comedy about killing would have been fairly fresh. By the time Verdoux was released, however, Arsenic and Old Lace (1944) and Murder, He Says (1945) had already shown that audiences would accept humor mixed with homicide. The original stage production of Arsenic and Old Lace had opened to great success in January of 1941, and it’s interesting to speculate that it might have encouraged Chaplin to buy Welles’ Landru idea.

Both Arsenic and Murder, He Says treat murder with a consistently farcical tone. I suggest in my FilmStruck Observations episode that Chaplin risks something more complex. For one thing, he takes the conventions of the serial-killer film more seriously than the other films do. He goes on to amplify and exaggerate those conventions in fascinating ways. For instance, he makes the policemen more or less stick figures, so we don’t care if they’re in jeopardy. In turn, Verdoux tries to win our allegiance through clumsy efforts to be debonair. (Uncle Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt is far more poised.) Chaplin’s use of the cycle’s conventions gets pretty specific. There were dead narrators in 40s films before Sunset Blvd. (1950), but we tend to forget that Chaplin uses the same device in Verdoux.

Going further, I discuss how Chaplin’s treatment of serial killing mixes different sorts of comedy—social satire and slapstick, the traditional comedy of manners and the comedy of ideas associated with George Bernard Shaw. This mix is rather discordant, and it’s responsible, I think, for much of the criticism the film attracted, then and now.

The Tramp as provocateur

Verdoux failed in the US for several reasons. Reviews were mostly unsympathetic, even harsh. Chaplin had been back in the headlines thanks to a messy paternity suit filed by Joan Barry. His reputation as a seducer of young women had unpleasant associations with Verdoux’s conquests. He was also known for his support for liberal causes and his strong stance against fascism. After the war, he was more and more reviled by right-wing politicians and activists. Chaplin’s defense of civil liberties made him seem too much a Communist dupe, or an active sympathizer. Charles Maland has suggested that the film’s promotion completely mishandled Chaplin’s star image.

The disgraceful New York press conference on the film was chronicled in the New Republic:

The disgraceful New York press conference on the film was chronicled in the New Republic:

He couldn’t have expected the shockingly rude, sustained impertinence of the attack that followed. Reporters were there, not to discuss his work with him, but to discredit and vilify and ridicule him personally—to hound him on his own opinions and habits. Was it true that one of his good friends (I am omitting names), a great musician, was a radical? Did this mean that he, Chaplin, condoned treason to this country, since his friend’s brother was accused of being a spy? Was Chaplin a Communist? Why, then, had he shown so little regard for the United States that, although he had paid taxes here for years, he was still a British subject? Even though two of his sons fought for this country in the war, and he did war work himself, why didn’t he do more? Exactly what percentage of his vast income made in the US had gone to alleviate the suffering of humanity?

While two perambulating mikes broadcast these questions and others, a swarm of cameramen set off lights in Chaplin’s face, so that in an hour he was not only knee-deep in spent flash bulbs, but practically blinded. His patience and courtesy were astounding, since his disgust must have at least compared to that of the few of us who could only be ashamed of what ugly, hostile liberties can be taken in the name of the freedom of the press.

The final scenes of Verdoux only heightened the suspicion that Chaplin was a danger to patriotic values. Soon he was subpoenaed by the House Unamerican Activities Committee, though he never testified. In 1952, after he and his new wife Oona left for Europe, his re-entry permit was rescinded. He went into exile in Switzerland.

The reviewers’ most common complaint was that the film refused to jell, but the film had eloquent defenders and brought forth some of the subtlest critical commentary of the period. James Agee, the only person to defend Chaplin during the press conference, wrote a famous three-part appeciation of the film that, I think, represents an early instance of in-depth film interpretation. Theatre historian Eric Bentley argued against those who found the movie a jumble of sentiment and slapstick. It was, he claimed, in the vein of Pirandello, where comedy gives way to the more philosophical mode, that of humor.

Reflection turns the merely funny into humor. . . . Thus, Pirandello argues, humor breaks up the normal form by interruption, interpolation, digression, and decomposition; and the critics complain of lack of unity in all humorous works from Don Quixote to Tristram Shandy—and we might add from Little Dorrit to Monsieur Verdoux.

Going still wilder, Parker Tyler speculated that in a parallel universe, Verdoux wasn’t executed. He abandoned his wife and son and took off on the road. Charlie the Tramp “had a past like anyone else. . . . Verdoux is . . . how Charlie came to be.”

Tyler’s flight of fancy isn’t surprising. This film can drive you a little nuts. It’s not ingratiating. It’s less perfect than provocative. It’s like the name itself, ver-doux, which translates as “sweet worm” or “gentle worm”—a little pleasant and a little creepy. The film is an obstinate thing that insists on being its contradictory self, not what you want it to be. For me, it’s perversely unlovable, and that unlovability is part of the Chaplin myth too. We should remember that the earliest Chaplin films show the Tramp as fairly nasty.

I suspect that Monsieur Verdoux can’t become a prototype; it flouts too many cherished categories. Or maybe the best category for it is that of experimental Hollywood movie. After all, the 1940s furnished more than its share of them.

Thanks as usual to Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and Peter Becker of Criterion. Our complete Observations on Film Art Criterion series is here. (I think you need to be logged in to see it.)

Welles discusses Shakespeare as blood-and-thunder melodramatist in This Is Orson Welles (HarperCollins, 1992), 217, and in a little more detail, in audiocassette number 4 accompanying the book, side A, 18:37. I draw my information about the preparation of Verdoux from Frank Brady, Citizen Welles (Scribners, 1989), 416-417; “Chaplin Announces Bluebeard Film,” Motion Picture Herald (29 November 1941); and Glenn Mitchell, The Chaplin Encyclopedia (Batsford, 1997), 191-198. Charles Maland’s reflections on Verdoux‘s promotional problems are in Chaplin and American Culture: The Evolution of a Star Image (Princeton, 1989), 250-251. The coverage of the Monsieur Verdoux press conference is by Shirley O’Hara in “Chaplin and Hemingway,” New Republic (15 May 1947), 39. Bentley’s 1948 essay is “Monsieur Verdoux and Theater,” In Search of Theater (Vintage, 1953), 154.

I’ve argued in The Rhapsodes that Agee’s critique displays the interpretive techniques borrowed from literary New Criticism. In the same book I discuss Tyler’s Chaplin book as an ultimate flight of performative criticism. One consequence of 1940s murder culture was the crystallization of the suspense thriller, a genre that has flourished ever since, for several reasons.

There’s more on my forthcoming book on the 1940s here.

Monsieur Verdoux.

FilmStruck and Criterion: Now Roku-ready

DB here:

Soon after Kristin posted the seventh installment in our Criterion series, there came the big news. FilmStruck and the Criterion Channel are now available for streaming via Roku. Some details are in this Variety story.

These streaming services had already been available on Apple TV, Chromecast, and other devices, but getting to Roku is a big boost. As of January, Variety says there are 13 million active Roku accounts. Roku capability is built into many smart TVs, and the set-top devices are reasonably low-priced. As a result, and as an early mover in the market, Roku has twice the penetration of its rivals.

Kristin, Jeff Smith, and I hope that subscribers will check out our monthly comments on films both classic and modern. Before or after our discussion, you can watch the films on the Criterion channel. We’ve regarded these short items as extensions of our blog, our research, and our textbook, Film Art: An Introduction. We try to make them clear and engaging.

If you subscribe to FilmStruck, you can log in and go straight to all our offerings. A synoptic page is here. Before Kristin’s entry on The Rules of the Game, we put up Jeff on the score of Foreign Correspondent, me on editing in Sanshiro Sugata, Kristin on landscape in two films by Abbas Kiarostami, Kristin on the child’s viewpoint in The Spirit of the Beehive, me on staging in L’Avventura, and Jeff on camera movement in Kieślowski’s Red. Whether or not you have FilmStruck, you can read blogs expanding on four of those entries here.

Coming up: Jeff on La Cérémonie and Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, Kristin on The Phantom Carriage and M, and me on Monsieur Verdoux, Brute Force, and Chungking Express.

And of course both FilmStruck and the Criterion channel offer a dizzying array of features, shorts, interviews, and bonus material. If you had told me just a few years ago that such a bounty would be so easily available, I’d have doubted it. Nothing beats seeing films on the big screen, but as a person who grew up with movies on TV (in small, degraded images and sound), I know that they retain some of their power in a lot of circumstances.

A monthly subscription equals the cost of three of Starbuck’s Cinnamon Dolce Lattes (Venti), whatever they are. Surely this is a great bargain. You can keep up with what’s coming along at Criterion’s website.

To those of you who have signed up and have followed our efforts: Thanks! Keep watching!

Camera connections: RED on FilmStruck: A guest post by Jeff Smith

Red (1994).

Jeff Smith here:

The Criterion Channel’s new installment in our Observations on Film Art series on FilmStruck presents me talking about Krszystof Kieslowski’s late masterpiece, Three Colors: Red (1994).

In the film’s final scene, chance and fate combine to bring a couple together. My comments trace how a cluster of cinematographic techniques has indicated the couple’s connectedness long before they become aware of one another. Red explores one of the director’s favorite themes: the ways that characters can be linked by mysterious, unspoken emotional bonds transcending the bounds of time and space.

Today I go into a little more depth regarding Kieslowski’s use of cinematography. Since there are spoilers, you may want to watch the film, on FilmStruck or some other platform, before going on.

Three colors, many meanings

Blue (1993).

Kieslowski made Red after Blue (1993) and White (1994). Although all were well received by critics, Red was the most celebrated. It won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and was nominated for three Oscars, including Best Cinematography and Best Director.

The widespread acclaim for Red proved to be bittersweet; Kieslowski died just two weeks before the Academy Awards ceremony took place. Although the director’s untimely passing might have given his film a boost in Oscar voting, Red ended up being overshadowed by other more high-profile nominees. Forrest Gump took home six awards, including Best Picture, Best Actor, and Best Director. Pulp Fiction topped Red for Best Original Screenplay. And the conventionally pretty imagery of Legends of the Fall aced out Piotr Sobocinski’s much more innovative work for Best Cinematography.

The basic conceit of the Three Colors trilogy derives from the nationalist ideals associated with the French tricolor: freedom, equality, and brotherhood. Kieslowski himself downplayed the significance of the tricolor by claiming that the films’ “Frenchness” was largely a result of the film’s financing. In interviews, Kieslowski claimed that the three colors of the trilogy could just as easily have been red, yellow, and brown if the money for the films had come from East Germany rather than France.

Still, even as Kieslowski himself made light of the films’ connection to French values, his comments can seem a bit coy. While the films continue Kieslowski’s longstanding interest in chance, fate, and parallel lives, each entry also offers an idiosyncratic take on the particular ideal associated with its respective color.

In Blue, Julie, the young wife of a composer, is devastated by the deaths of her husband and daughter in a tragic car accident. Forced to start anew after the loss of her family, Julie learns that her husband was not the man she thought she knew. In the midst of tragedy, the combination of grief and new knowledge paradoxically affords Julie a revitalized sense of existential freedom. With everything she had once cared about now gone, Julie relinquishes her roles as wife and mother, and her life takes unexpected paths as a result.

Deep sadness is not usually a trait that we associate with liberté. But Kieslowski’s surprising treatment of this theme is reminiscent of the famous line from Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” that states, “When you ain’t got nothing, you got nothing to lose.” Reduced to nothing, Julie finds new love and new purpose.

In a similar vein, White explores the idea of equality in rather unusual and unexpected way. One might expect Kieslowski film’s to be about political equality given his home country’s long struggle to achieve independence. Yet Kieslowski instead offers a dark comedy of betrayal and revenge.

The film explores the power dynamics of marriage by focusing on a young couple living in Paris. Dominique seeks a divorce from her husband Karol Karol, a Polish immigrant working as a Parisian hairdresser. The divorce leaves Karol impoverished. He is forced to go back to his native Poland where he plots revenge. White then takes an almost Hitchcockian turn as Karol fakes his own death but leaves evidence that incriminates Dominique. When Dominique is convicted for murder, Karol is finally able to “balance the scales” in his relationship. But the film’s haunting conclusion leaves Karol’s future with Dominique completely in doubt. In a distant POV shot, Karol gazes at his ex-wife through the window of her prison cell.

They exchange sad smiles, realizing that they still share an emotional bond despite their earlier duplicities.

He ain’t heavy, he’s my brother(hood)

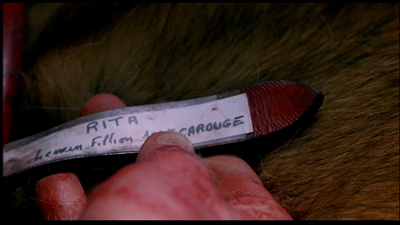

Kieslowski’s take on brotherhood (fraternité)in Red proves to be equally askew. The film’s central plotline concerns Valentine, a young model and student living in Zurich. She is brought by circumstance into the personal orbit of Joseph Kern, a cynical retired judge. Valentine has accidentally injured Kern’s dog, Rita, and seeks him out to see what she should do. Upon learning of the accident, Kern replies with indifference. Shocked by his apathy, Valentine asks Kern whether he would react any differently if it was his daughter who was run over.

Later Valentine returns to Kern after he sends money to pay for the dog’s veterinary care. During this visit, she discovers that the judge is using a radio to monitor the phone calls of his neighbors. Once again, Valentine rebukes Kern, this time for invading the privacy of others.

Chastened by Valentine’s disapproval, Kern begins to reform. He voluntarily confesses his spying to both his neighbors and police. He also accepts Valentine’s invitation to attend a fashion show in which she is a model. Under Valentine’s influence, Kern rejoins life, coming out of his isolation and resuming normal human interactions.

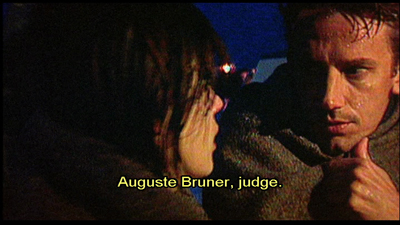

Red features a subplot involving a younger judge, Auguste, who is betrayed by his girlfriend, Karin. While the professions of the two men, Kern and Auguste, provide a simple story parallel, Kieslowski pushes this idea further than most other directors would. In fact, Kieslowski introduces so many similarities between the two characters that Auguste seems to be simply a younger version of Kern.

For example, the manner in which Auguste learns that Karin is cheating on him is remarkably similar to Kern’s account of his own wife’s infidelity. Moreover, Auguste owns a dog that he later appears to abandon much as Kern seems to give up on Rita after Valentine injures her. Both characters share a physical proximity to the other’s female counterpart. That is, Auguste lives near Valentine just as Kern lives near Karin. Lastly, Kern and Auguste both stop their cars at an intersection dominated by Valentine’s image on a huge billboard.

In a more telling parallel, Auguste describes an odd coincidence that occurs as he is walking to the site of his law exam. Auguste accidentally drops his book, and the book falls open to a page that contains information that later appears as a question on the exam. Later, after the fashion show, Kern describes an identical situation when he was a young man. Although Kern and Auguste never meet, viewers are further encouraged to recognize these similarities based on the physical resemblance of Jean Pierre Lorit to Jean-Louis Trintignant.

Instead of exploring brotherhood through more familiar conceits, like family, friends, or community, Red treats it as a metaphysical concept. In Red, brotherhood is an unseen force that binds people together, often in ways of which they are unaware. More importantly, though Kieslowski develops this idea through a story that is riddled with similarities, parallelisms, and synchronicities. And these apply not just to our two male protagonists, but also to the film’s central couple, Auguste and Valentine.

How do you represent destiny?

You’re a filmmaker. The story you’re telling is about a couple that spends much of the movie separate from one another. Perhaps they don’t meet until late in the film, maybe not until its final scene. How do you communicate to the audience that these two people are destined to be together? Over the years, filmmakers have utilized a wide range of techniques and devices to solve this problem.

In some early musicals, filmmakers created parallel scenes featuring each character to foreshadow their later romance, as in Ernst Lubitsch’s The Love Parade. First, the caddish Count Alfred talks with his valet and sings “Paris, Stay the Same.” Then Queen Louise talks with her courtiers and sings “Dream Lover.”

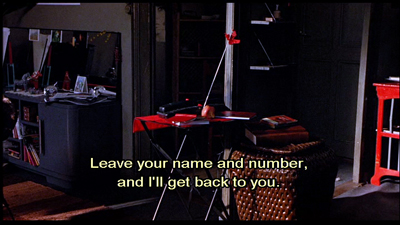

More recently, filmmakers include certain plot details to suggest that the characters are meant to be together. In Sleepless in Seattle, Annie believes herself to be reenacting scenes from the Cary Grant-Deborah Kerr weepie, An Affair to Remember. Annie takes each of these uncanny experiences as signs that the radio caller named Sleepless in Seattle is her true soul mate.

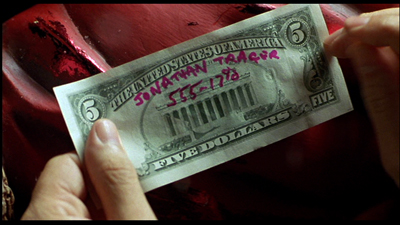

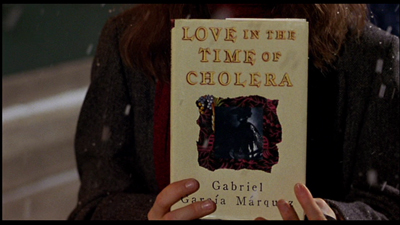

In Serendipity, John and Sarah meet in the film’s first scene. They separate, but they send personal tokens into the world inscribed with their names and phone numbers: a $5 bill and a copy of Love in the Time of Cholera. If these items return to their lives, it will be a sign that the couple will reunite.

In other cases, a filmmaker might use the formal properties of the medium to hint at the character’s destiny. In Turn Left, Turn Right, Johnnie To uses color and composition to anticipate the couple’s fateful encounter late in the film.

In Red, Kieslowski relies on a similar cluster of devices to suggest the workings of chance and fate for Valentine and Auguste. Like the films mentioned above, the director foreshadows the fate of his characters through a number of odd coincidences. At one point in the film, Valentine voices her hopes that her boyfriend, Michel, will call when the phone suddenly rings. Similarly, during one of Valentine’s visits to Kern’s home, they eavesdrop on Auguste and Karin discussing their plans for the evening. Auguste decides to flip a coin to determine whether he will sit home studying or will join Karin for an evening of bowling. As Kern and Valentine listen to this conversation, the judge also flips a coin, which comes up with the same result reported by Auguste.

Later in a visit to a music shop, Valentine listens to an album of music by the composer Van den Budenmayer. Unbeknownst to her, Auguste and Karin listen to the same album just a few feet away. (Taste in music seems to link all four of these characters, as we see this same Van den Budenmayer record in Kern’s home.)

Although these parallels provide a narrative basis for Kieslowski’s theme of connectedness, they are strengthened by his stylistic choices. Four particular techniques emerge as the most salient: the use of color, framing, deep staging, and camera movement. Of these, camera movement is the most important.

Oh, telephone line, please give me a sign

The use of camera movement to suggest the couple’s connectedness is established in the film’s first sequence, which follows a phone call’s path through a communication network that links England to Switzerland. Red begins with a medium close-up of a man dialing a telephone.

Although we don’y realize it at this early point in the film, in retrospect, we can surmise from the framed photograph of Valentine and the copy of The Economist sitting on the desk that this is Valentine’s boyfriend, Michel, who is working in England.

As we hear the number being dialed, the camera follows the phone line down to the socket in the wall. The next shot of the sequence traces the phone’s electromagnetic signal as it feeds into a major trunk line for thousands of other phone customers. The camera begins to spin as it moves forward through these wires. The resulting image is a welter of color and movement.

In the next shot, the camera continues to move forward rapidly, following the signal as it passes through the underwater cables buried beneath the English Channel. Here again, we might easily miss the significance of this shot since it comes so early in the film. Yet it plays an important role by foreshadowing the location of the tragic ferry accident that concludes the film.

The camera dips into, then out of the water, and reverses course, now tracking rapidly backward. It seems to pass through several red brackets that arch over the phone company’s transatlantic cables. The next two shots chase the signal as it travels in the phone lines of an apartment complex. By now, the camera is moving so fast that the lateral tracking movement is seen as a blur of light and metal. The next shot shows the camera spinning wildly. The camera then swishes past a telephone switchboard until it finally stops on a single flashing red light.

For a director not especially known for stylistic flourishes, this opening camera movement is a real corker. Yet its significance goes beyond extravagance. It previews the way Kieslowski will use camera movement to underscore the characters’ physical proximity to one another. It also foreshadows the many missed connections Valentine and Auguste will experience before finally meeting one another at the end of the film.

Morning routines, broken glasses, and fortuitous falls

Later camera movements creating physical connections are more staid than this bravura opening sequence. But they do establish a pattern that carries through the remainder of the film.

The next scene begins with a shot of Auguste gathering his books and preparing to take his dog for a walk. The camera follows Auguste and his dog as they cross the street, but drifts away from them, craning up past the red awning of Chez Joseph to introduce our protagonist, Valentine. The camera reframes Valentine as she moves about her apartment engaged in a phone conversation, confessing her loneliness as she prepares to leave for a photo shoot.

When Valentine mentions the weather, the camera tracks toward an open window, allowing us a glimpse of Auguste in the distance, returning to the entrance of his building. By blocking and framing the scene in this way, Kieslowski cleverly creates a bookend effect. It begins and ends by underlining the characters’ proximity to one another, suggesting a strange synchronicity to their actions in the process.

As the film goes on, Kieslowski encourages the viewer to notice the way that Valentine and Auguste’s paths continually cross, even as they remain largely ignorant of one another’s presence.

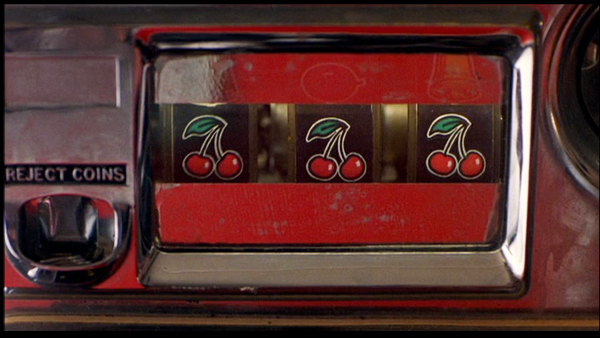

Consider the scene in which Valentine wins a jackpot playing the slot machine. Kieslowski begins the scene with a shot of Valentine exiting her car. The camera tracks slightly to the left to reframe Valentine as she walks to the entrance of Chez Joseph. Valentine buys a newspaper, and as she begins to read the front page, a figure steps in front of her holding a carton of Marlboro cigarettes.

The figure passes through the frame so quickly that it’s only in the subsequent shot that we realize it was Auguste, seen here entering his apartment with his dog. After Auguste has exited the frame, the camera racks focus at the same time that it pans left and tilts down to reveal the slot machine. We then see a close-up of Valentine’s hand as it enters the frame and pulls the handle downward. In this instance, Kieslowski’s framing makes us work harder to see the connectedness of the characters. Auguste is framed so that we only see his torso. Valentine is framed so that we only see her hand.

Later in the film, Auguste is unable to contact his girlfriend and drives off in a panic. He makes a hasty U-turn, framed through the window of Chez Joseph. As the red Jeep pulls away, the camera tracks right to follow it, but then continues its movement toward the slot machine, revealing three cherries that earlier produced Valentine’s jackpot.

The owner of Chez Joseph had told Valentine the three cherries were a bad omen. It will prove to be true as well for her counterpart, Auguste.

Another example of the couple’s connectedness occurs in the brief scene at the bowling alley. After a couple of shots that establish the setting and Valentine’s presence within it, Kieslowski cuts to a shot of Valentine rolling her second ball of the frame. The camera is positioned in the space behind the seating area in the alley.

From this initial set-up, the camera then tracks left past several other bowlers and stops on a close-up of a broken beer glass, a lit cigarette, and a crumpled package of Marlboros. The camera cranes up slightly on these objects, lingering briefly to enable the viewer to grasp their significance. Here again, Kieslowski has opted for a slightly elliptical way to suggest Auguste’s presence, which was presaged by the phone conversation overheard by Kern. The broken beer glass and lit cigarette suggest that Karin never showed up for their date, and further that Auguste left the alley in a huff.

Perhaps the most interesting camera movement in Red occurs in the scene in which Kern and Valentine meet after her fashion show. Kern explains that when he was a young man, he used to sit in the balcony in that same auditorium. On one occasion, he dropped a book and it fell several feet to the floor below, but opened to a section that is covered on the law exam he was about to take. (Recall that the same thing happens to Auguste as he crosses the street.)

Kieslowski could simply have Kern recount his story, but instead the director treats the moment much more dynamically. The camera traces the path of the book’s fall. The camera starts at a high angle looking down at Kern and Valentine near the stage, and ends at a low angle looking up at them.

Through a simple camera movement, Kieslowski has reinforced another of the film’s major themes: the interpenetration of the past with the present.

The unbearable redness of Being

As I’ve already suggested, camera movement seems to be the most important device for conveying Kieslowski’s central themes. It’s a vivid way to physically embody the unseen connections that link Valentine and Auguste together before their coincidental meeting after the ferry accident.

Still, camera movement is not the only technique to carry such significance. Color also proves important, especially since the film’s title prompts particular attention to it.

Toward the start of the film, Kieslowski seems to tease us with all of the red things that appear in the frame as in the shots of Valentine’s apartment and the ballet studio.

Yet he was also careful to point out that red is not even the dominant color in the film’s palette. Working with the film’s production designer, Kieslowski opted to emphasize browns and blacks, in part because the colors are associated with the world of courtrooms and legalese that connect Kern with Auguste.

Yet, even as an accenting color, red still draws the eye toward it. One reason for this is Kieslowski’s restricted palette, which features very little green and almost no blue. Red pops out because it is often the only bright color within the mise en scene, which mostly features more neutral earth tones.

Because red is conventionally associated with things like love, passion, anger, and danger, we might be tempted to match those meanings to the film’s story. And there are some moments in Red where such color symbolism seems like a possibility. Consider, for instance, the insert of Valentine’s bloodstained hand checking Rita’s tag.

Yet, for every one of these moments, there are a dozen others where the color seems to have no such correlation. Why, for instance, would we ascribe passion or anger to Chez Joseph’s awning or to the three cherries on the slot machine?

Since the color is present in almost every scene, one would be hard-pressed to find any coherent pattern based on such traditional associations.

Instead, like camera movement, red seems to function as a visual metaphor for the film’s off-kilter treatment of brotherhood. Indeed, Kieslowski anticipates Auguste and Valentine’s eventual coupling by consistently linking them to red props and decor. Auguste has his red jeep, which we see several times throughout the film. He also is shown toting cartons of Marlboro cigarettes, which are identifiable through the brand’s signature color.

Valentine, on the other hand, is frequently shown with red colored clothing and textiles. When Valentine takes Rita out for a walk, she wears a red sweater and carries a red leash. She sleeps with a red shirt that serves as a substitute for her absent boyfriend, Michel. During a photo shoot, Valentine poses against a vibrant red backdrop. Lastly, Valentine is shown in several different settings where the décor is dominated by red, such as the ballet studio, the bowling alley, and the auditorium where the fashion show takes place.

Viewed in this respect, color in Red functions as a classic instance of an intrinsic norm. By rejecting more conventional extrinsic meanings associated with the color, Kieslowski instead treats red as something that develops more localized significance. Given his longstanding interest in the workings of chance, fate, and destiny, it should not surprise anyone that red objects, costumes, and settings come to symbolize these larger cosmic forces.

The Breath of Life

The color red is also prominent in Valentine’s “breath of life “ billboard ad. The ad is shown at least six times in the film, and its recurrence will play an important role in preparing for the film’s climax.

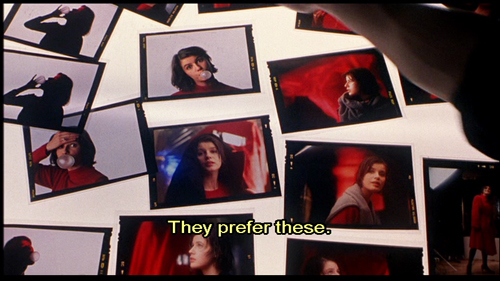

We first see the ad in production during Valentine’s photo shoot. She is posed in profile, and her mood seems playful. She blows a bubble with her gum, presumably using the product featured in the campaign. The photographer asks Valentine to remove the gum from her mouth and to tie her sweater around her neck. He then instructs her, “Be sad. Sadder. Think of something awful.” By asking Valentine to imagine tragedy, the photographer is able to get the image he wants.

We see the resulting photograph a few scenes later amongst a pile of other snapshots from the session. Jacques, the photographer, calls our attention to it by indicating that the shot likely will be used in the campaign.

The billboard itself is later shown on two separate occasions. We first see it looming over the traffic intersection where Auguste’s red jeep is stopped.

We see the same image again when Kern drives to Valentine’s fashion show.

It appears again just before the film’s climax in a brief shot showing workmen taking the billboard down.

One might assume that Kieslowski has put a cap on the “breath of life” visual motif. But he revives it one final time, albeit in a way that inverts much of its earlier significance in the film’s plot. Red’s climactic scene begins with Kern walking outside to retrieve his newspaper. On his way back, he glances at the headline, which notes that hundreds of people are dead in a ferry accident on the English Channel.

Kern then turns on his television to learn the latest news of this tragedy. A reporter states that there were only seven survivors of the accident. In a rather tongue-in-cheek gesture, six of the seven survivors happen to be characters from the Three Colors trilogy. We first see a shot of Julie Vignon, who is described by the reporter as a composer’s widow.

This is followed by shots of Karol Karol and his wife Dominique.

Next comes a shot of Olivier Benoît, a family friend who had become Julie’s lover in Blue.

Finally, we see a shot of the two Swiss survivors, Auguste and Valentine.

For the first time in the film, the two characters are shown looking at one another. The television image freezes on Valentine and Auguste.

The camera slowly zooms in on the image on the television to get a closer view of Valentine. When the zoom ends, the video image is eerily similar to the “breath of life” billboard.

The gray blanket has taken the place of Valentine’s sweater and the red windbreaker of a rescue worker replaces the red cloth backdrop of the ad. But Valentine’s facial expression and pose approximate that in the ad.

The video image, however, seems to reverse many of the advertisement’s earlier associations. During the shoot, Valentine only pretends to be sad. Her expression and pose are commodified, used to sell chewing gum to punters taken in by the image’s sensuous visual appeal. In contrast, the video image of Valentine’s rescue captures her genuine response to tragedy. Valentine’s look expresses a sense of shock and surprise that she survived when so many of her fellow passengers died. Moreover, the gloss of the billboard advertisement has been replaced by the roughhewn look and “on the fly” reality of video reportage.

From this shot, Kieslowski cuts to an enigmatic medium close-up of Kern, who stares into the morning sunlight through his window.

The shot seems to pose more questions about the story than it answers. Is Kern merely relieved by the news that Valentine has survived? Or is there something deeper behind his rueful smile? Does Kern feel responsible for Valentine’s situation? After all, he recommended that she take the ferry rather than fly and asks to examine Valentine’s ticket in their last meeting together.

For some critics, the shot adds a Shakespearean wrinkle to Kieslowski’s film. For these critics, this shot suggests that Kern, like Prospero in The Tempest, has conjured the storm out of thin air in order to satisfy his psychological desires.

Whether or not we see this moment as a reference to The Tempest, it seems clear that Kern has uncannily anticipated Valentine’s fateful encounter with Auguste throughout the film. Consider the following:

- Kern predicts Karin’s breakup with Auguste. He also claims that, despite Auguste’s declaration of love for Karin, that Auguste has not yet met the right woman. This language is echoed later when Kern describes his own despair after learning of his wife’s affair. The Judge says to Valentine, “Perhaps you are the woman I never met.”

- Earlier in the film, Valentine says she is thinking of cancelling her trip to England because of her brother Marc’s legal troubles. Kern insists that she keep her travel plans saying it is her “destiny.”

- Kern acknowledges that he crossed the English Channel as a younger man in pursuit of his wife and her lover, Hans Holbling. His quest came to naught, however, when he learned that his wife died in an accident. Both the trip and his wife’s fate prefigure the ferry tragedy that ends the film.

- Kern describes a dream he has of Valentine as an older woman. Kern’s account of the dream prophesies that Valentine will meet a man and that the couple will grow old together.

All of these things seem to foreshadow Auguste’s fortuitous meeting with Valentine in the aftermath of the accident. Since Kern is, at least in some indirect way, responsible for the couple’s meeting, he has given Valentine a gift in addition to the pear brandy that the two previously enjoyed together. In Auguste, he has given Valentine a younger version of himself.

At its heart, Red is an existential mystery. When Valentine and Auguste meet at the end, their union seems less like coincidence and more like the outcome of divine intervention. Yet, in retrospect, Kieslowski has carefully prepared us for this moment by using color and camera movement not only to underscore their physical proximity, but their many missed connections.

In exploring the French value of fraternité, Kieslowski’s unusual treatment of the subject emphasizes the invisible forces that bind people together even as they elude our conscious grasp. Although Kieslowski likely didn’t intend Red to be a valedictory film, it is a fitting testament to his larger oeuvre as a director. In a story suffused with grief and regret, Red’s final scene suggests that love and hope can bloom in even the most bleak situations.

Thanks as usual to the Criterion team, particularly Peter Becker and Kim Hendrickson, for their support. Kristin, David, and I are very happy to be involved with their FilmStruck activities.

For more on Krzysztof Kieslowski’s films, see Annette Insdorf’s Double Lives, Second Chances: The Cinema of Krzysztof Kieslowski, Joseph G. Kickasola’s The Films of Krzysztof Kieslowski: The Liminal Image, and Marek Haltof’s The Cinema of Krzysztof Kieslowski: Variations on Destiny and Chance. Two collections of interviews with Kieslowski have been published: Kieslowski on Kieslowski and Krzysztof Kieslowski: Interviews. For a concise overview of the films in the Three Colors trilogy, see Geoff Andrews’ monograph in the BFI modern classics series.

An earlier entry considers the ways that film stories rely on chance and coincidence, with Serendipity as a central example.